Submitted:

08 January 2026

Posted:

09 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

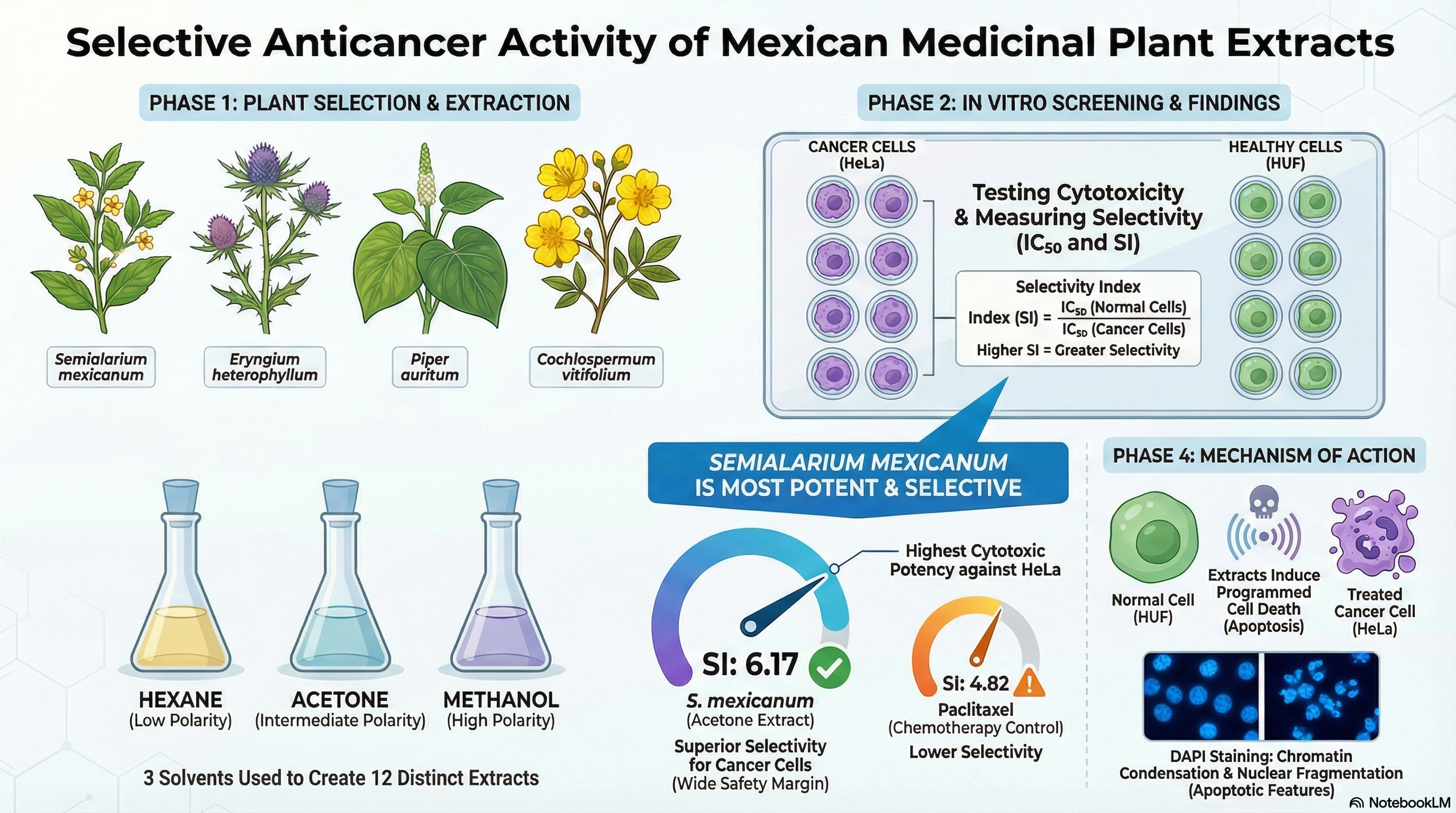

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Plant Material

2.1.1. Plant Material Extraction

2.1.2. Total Polyphenol Content

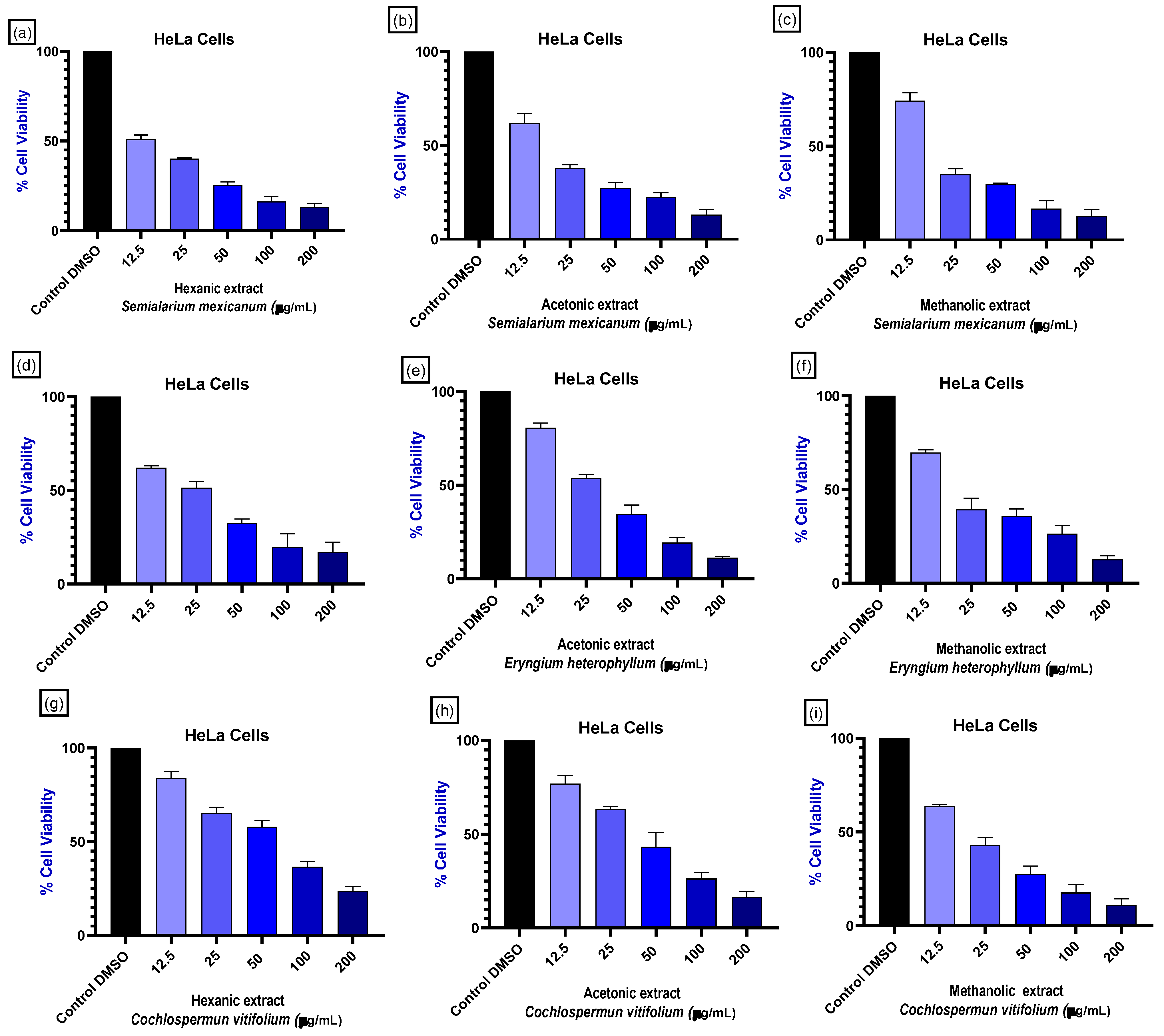

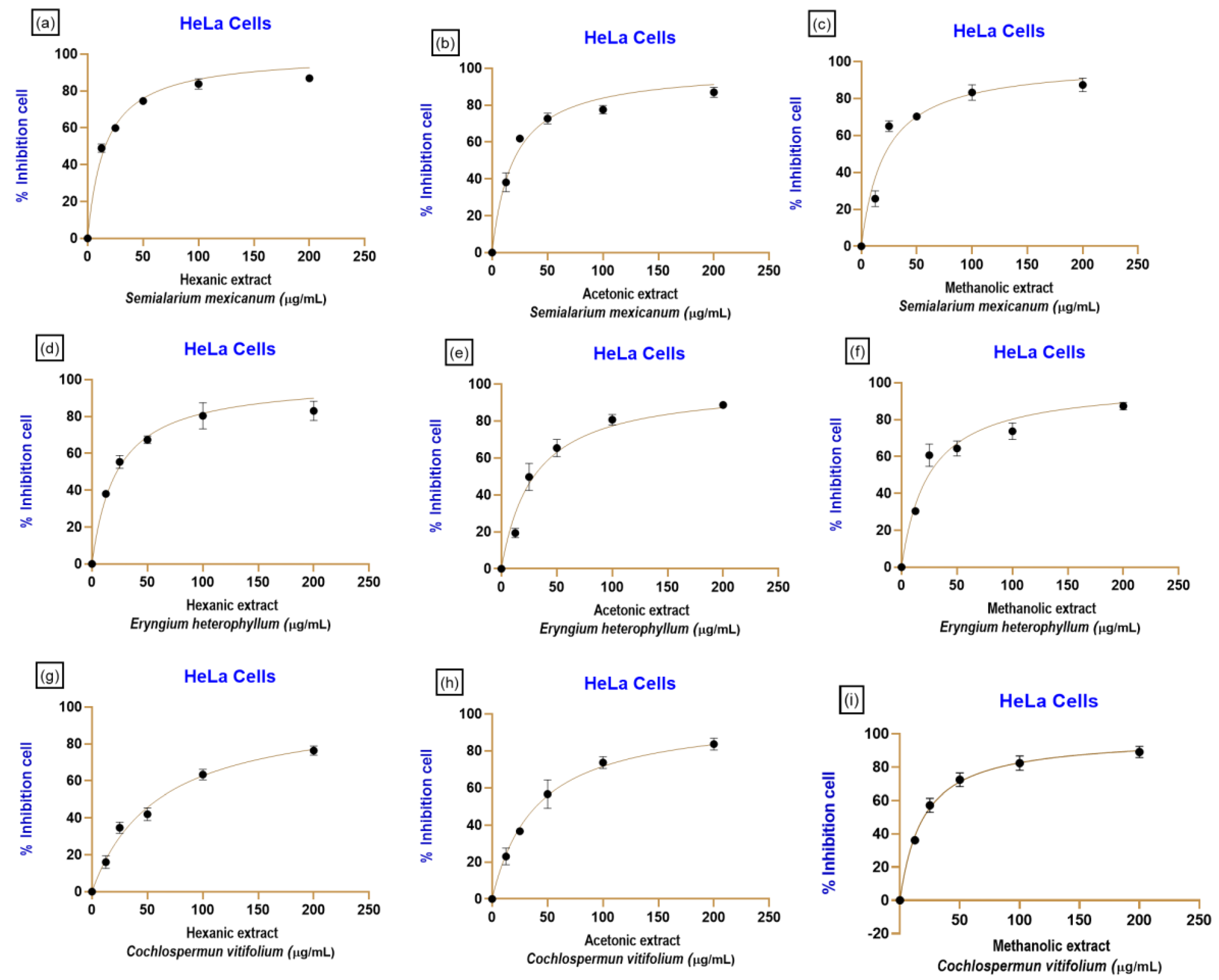

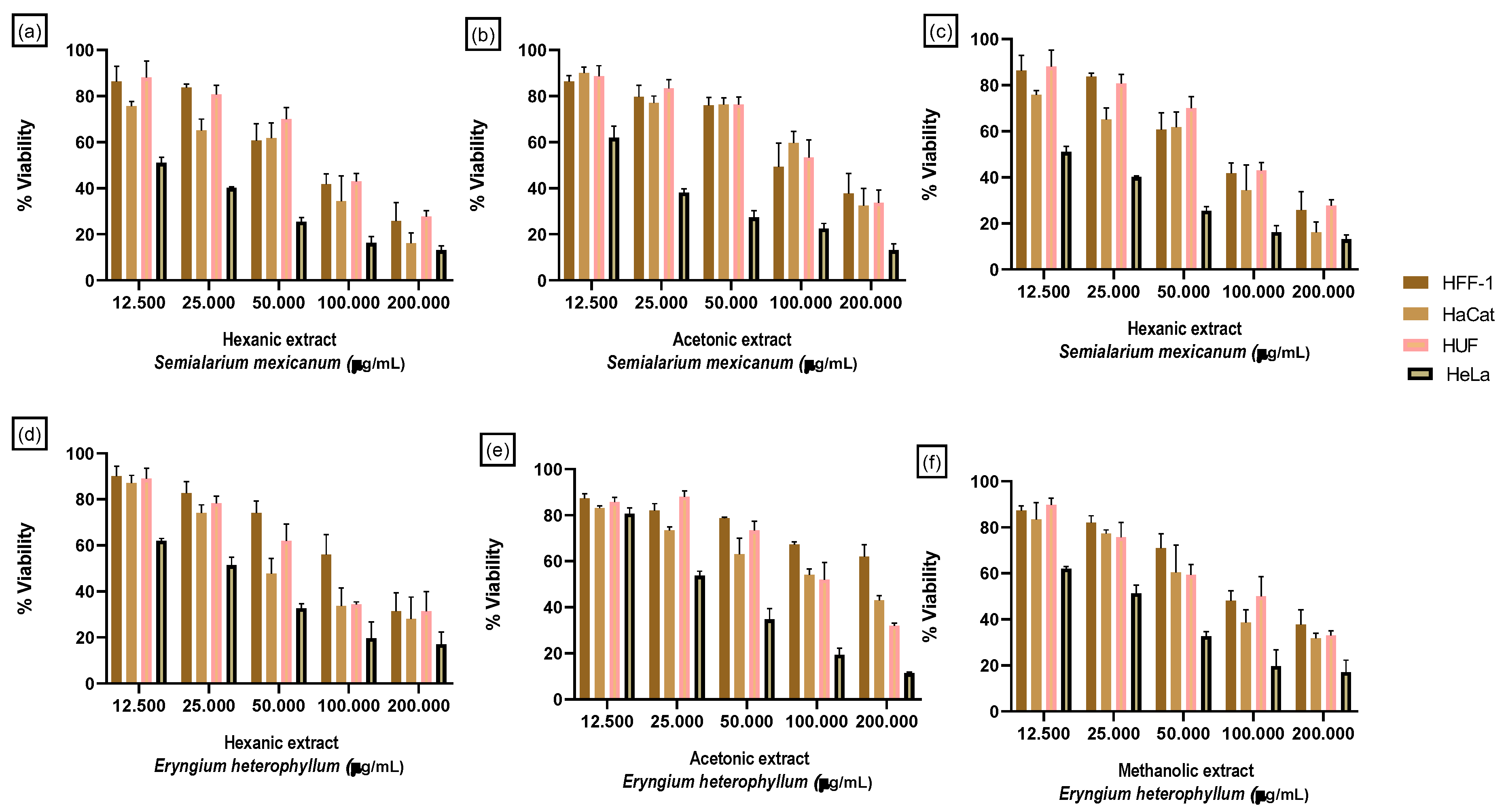

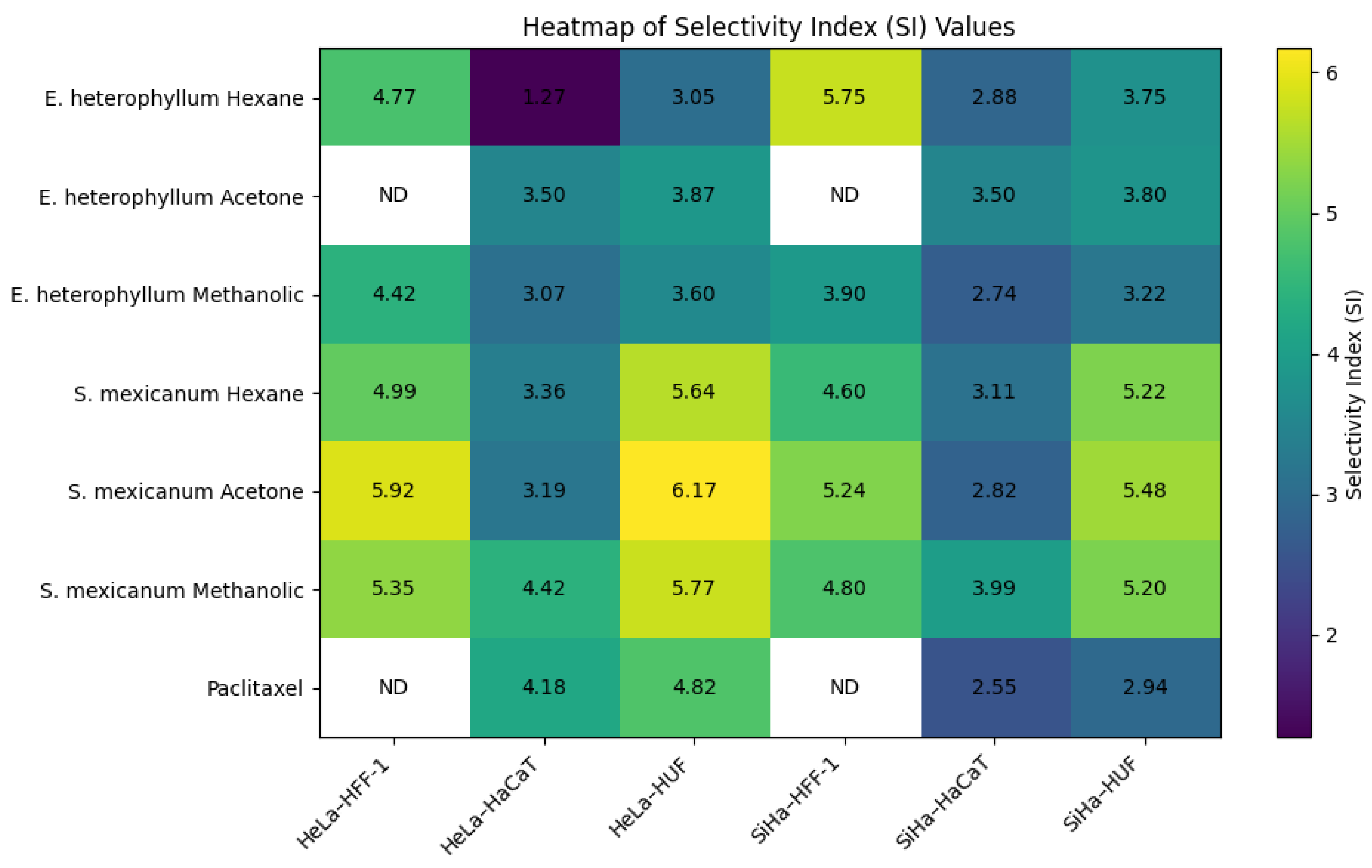

2.1.3. Effect of Mexican Medicinal Plant Extracts on Cell Viability in Human Cancer and Normal Cell Lines

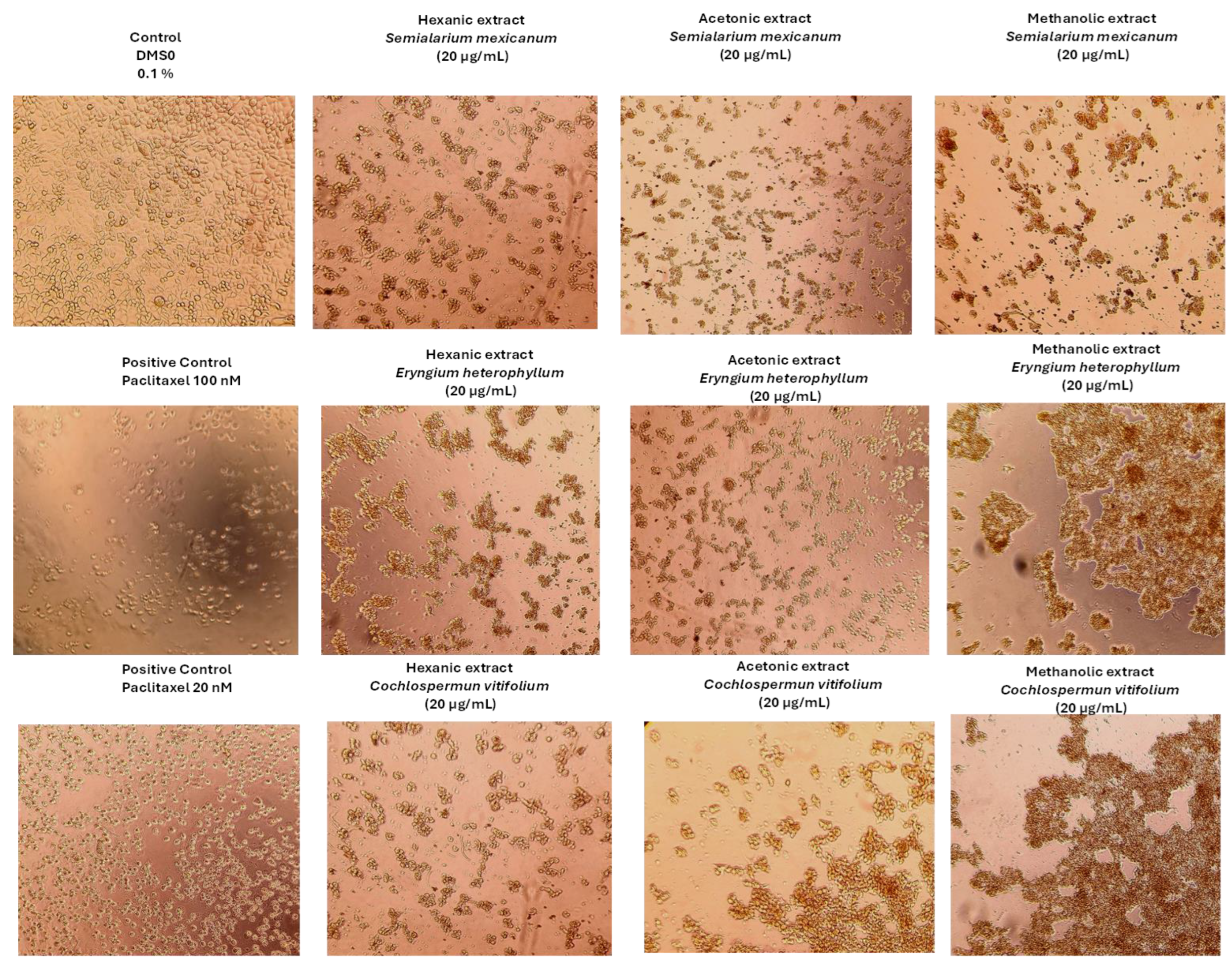

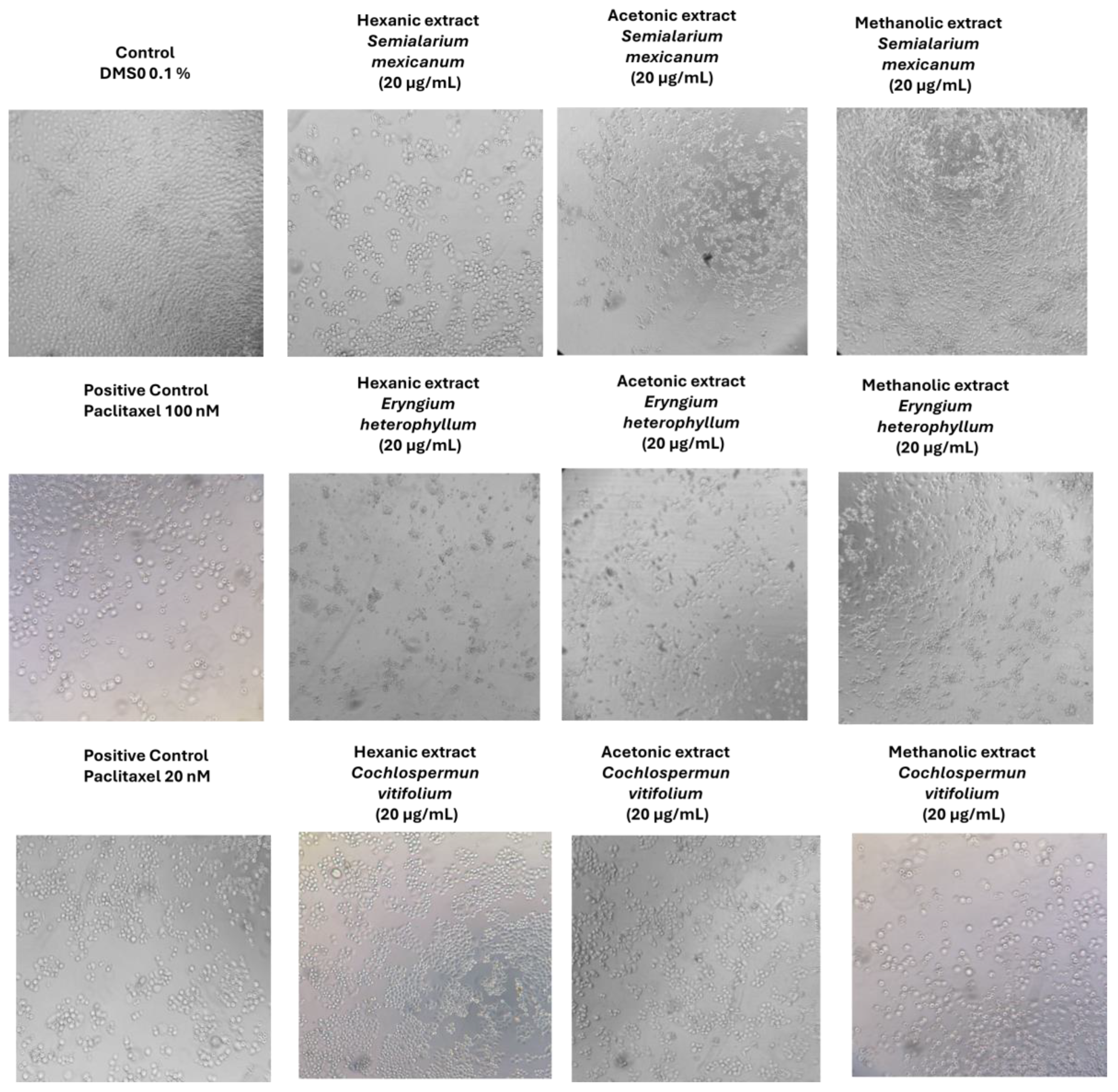

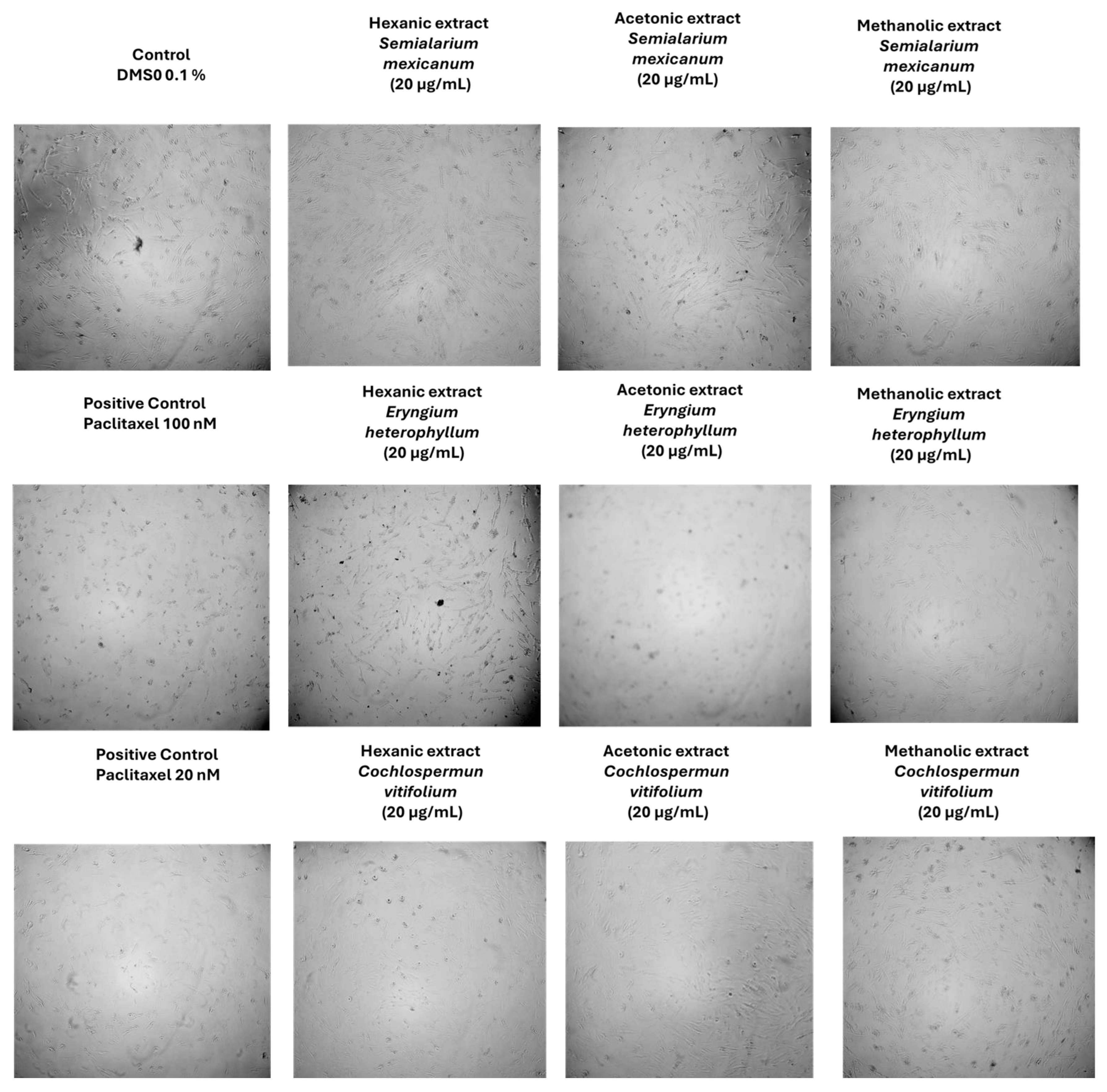

2.1.4. Morphological Assessment of Extract-Induced Cytotoxicity in Cancer and Normal Cells

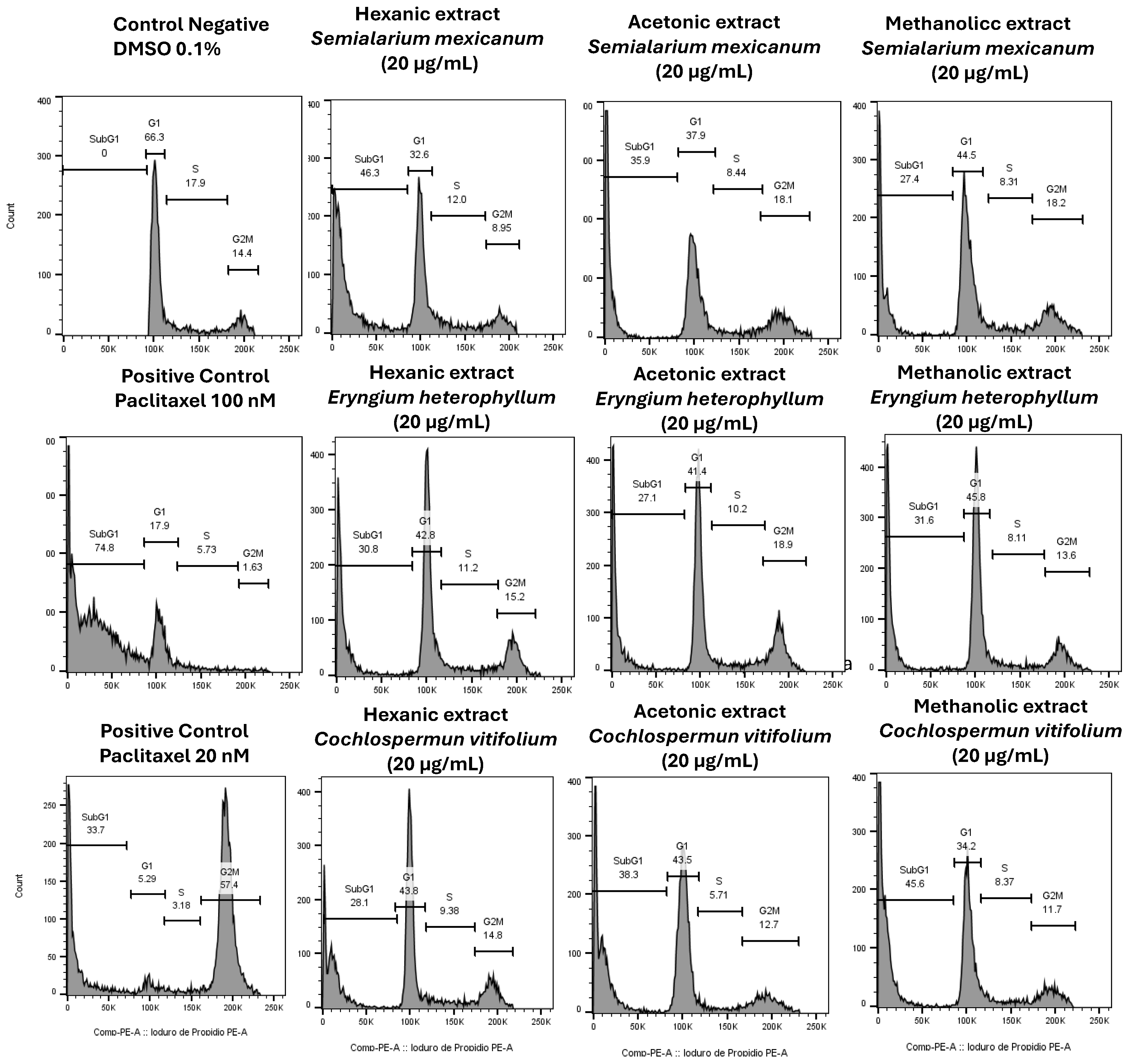

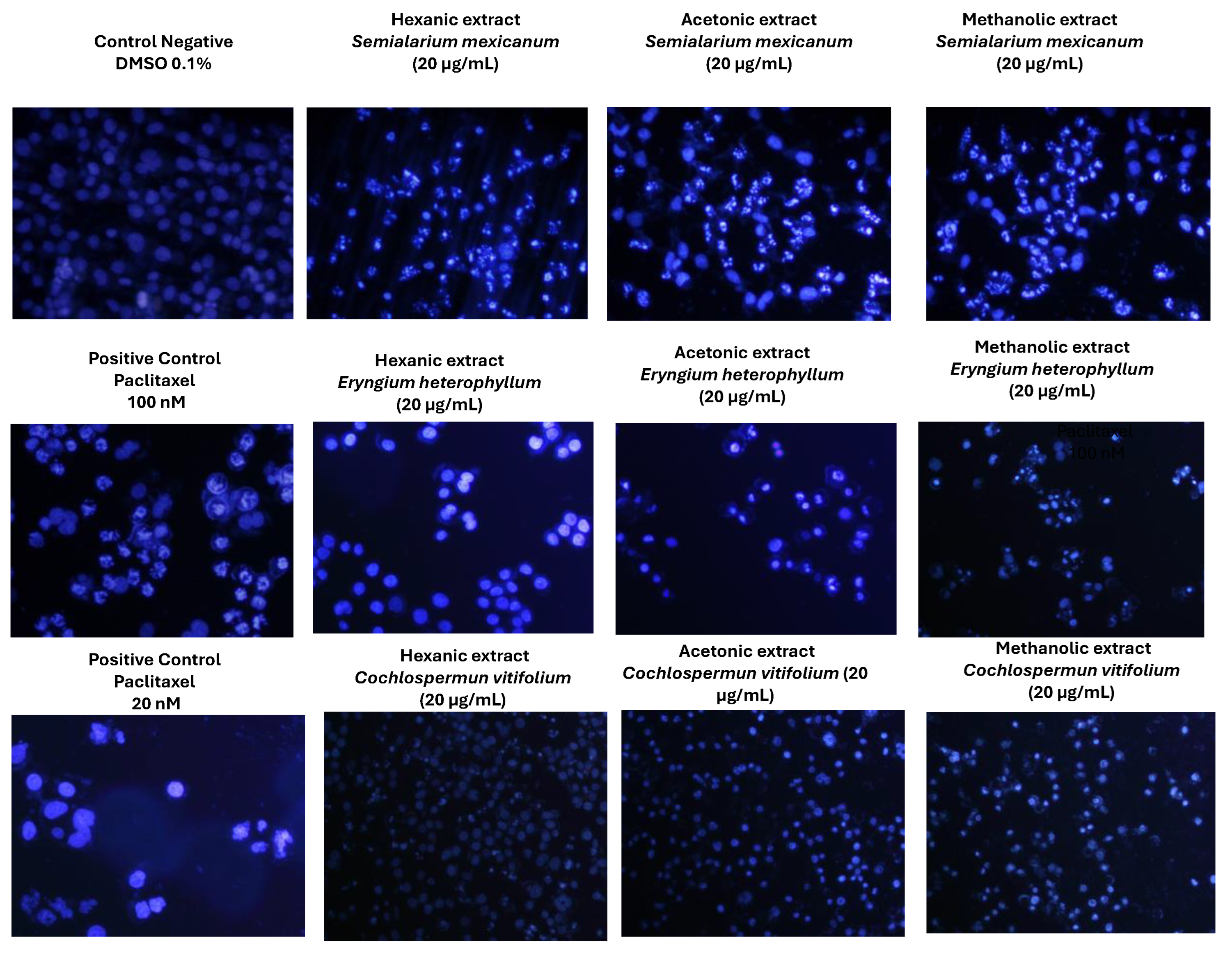

2.1.1. Effects of Hexanic, Acetonic, and Methanolic Extracts (Eryngium, Semialarium y Cochlospermum), on Cell Cycle Progression and Nuclear Morphology in HeLa Cells

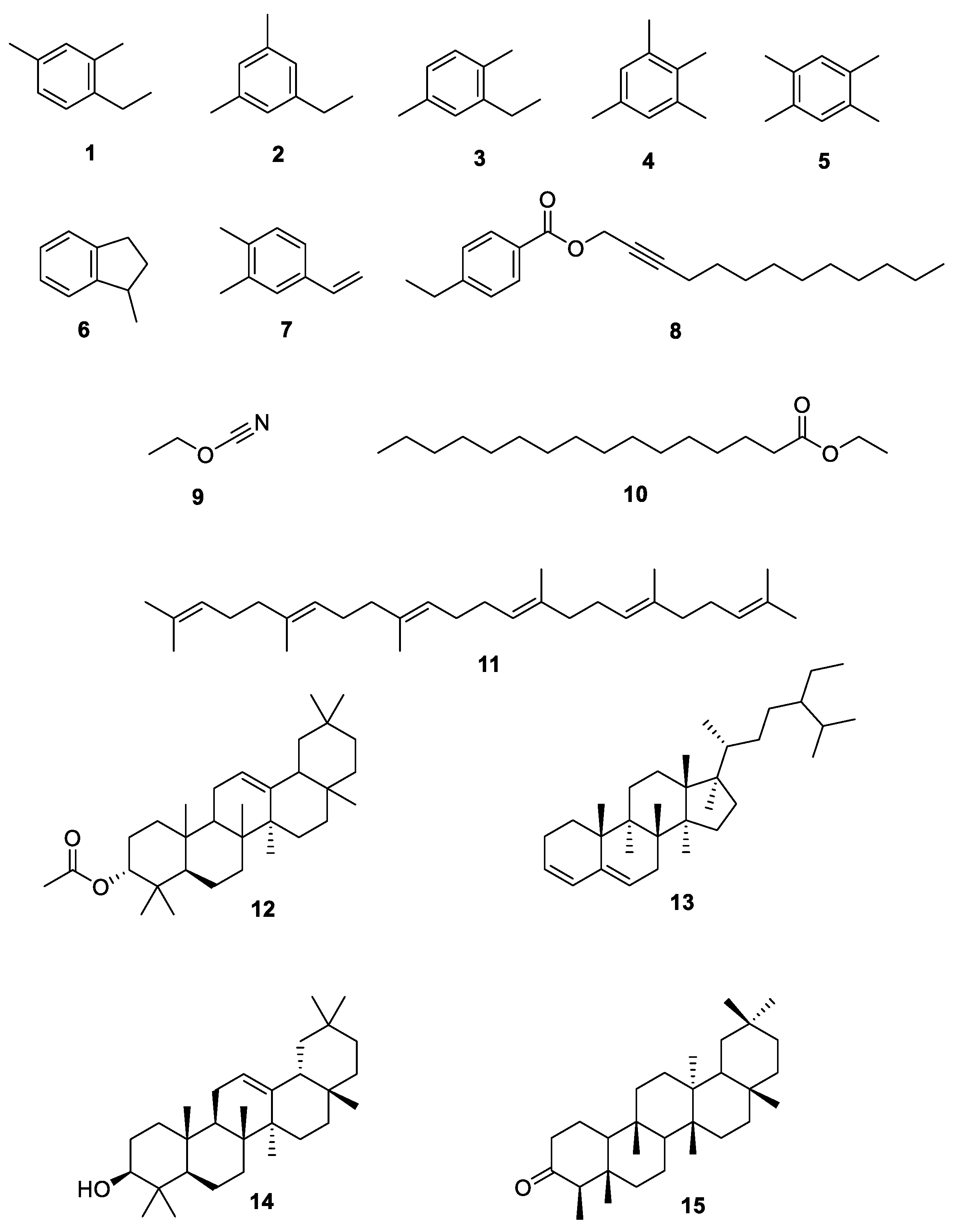

2.1.3. Chemical characterization

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

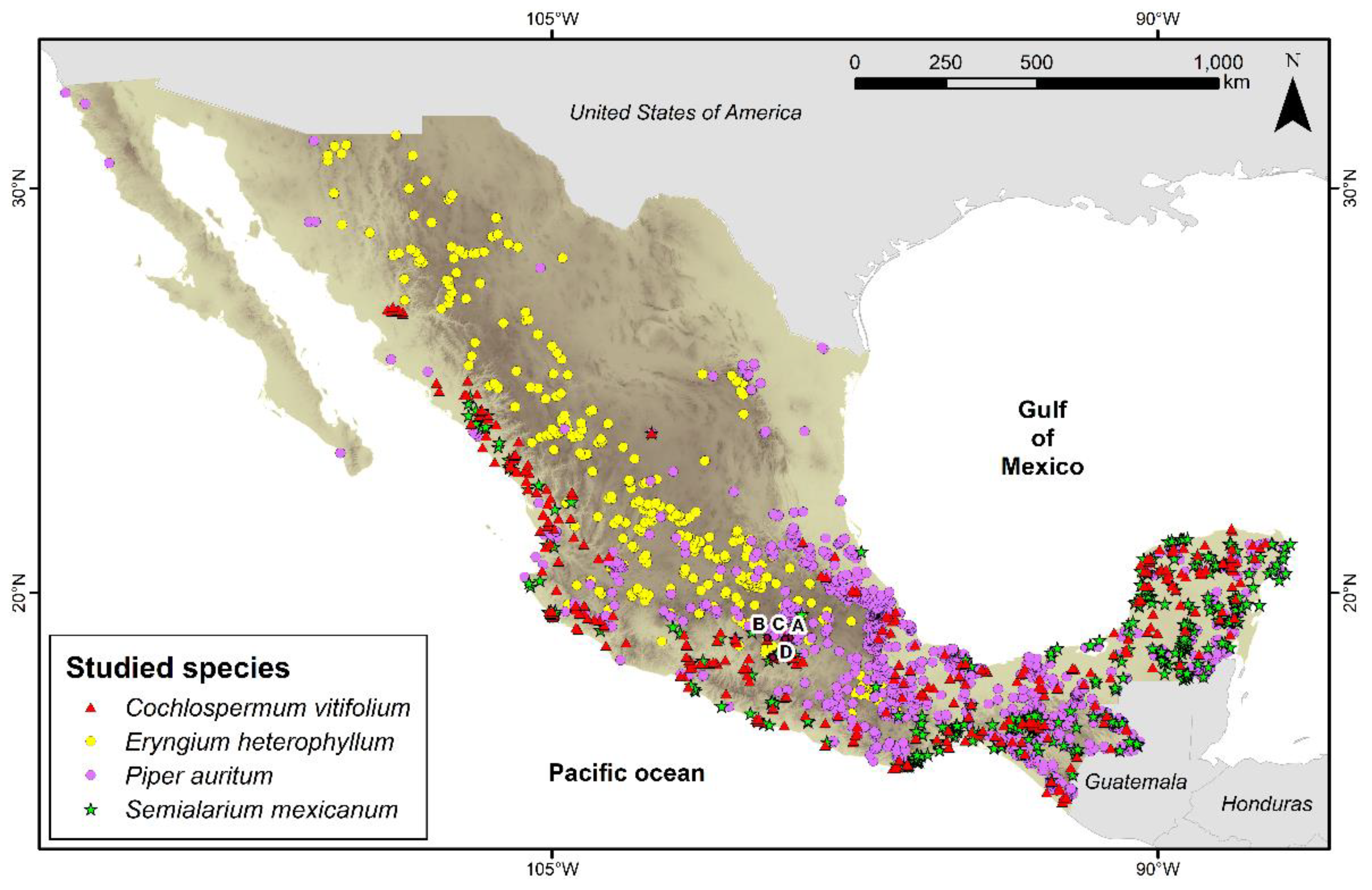

4.1. Collection of Plant Materials

4.2. Plant Material Extraction

4.3. Total Polyphenols

4.4. GC-MS Analysis

4.5. Cell Culture and Cytotoxicity Assay

Data Analysis

4.6. Cell Cycle Analysis

4.7. Nuclear Morphology Analysis by DAPI Staining

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Soto, K. M.; Pérez Bueno, J. J.; Mendoza López, M. L.; Apátiga-Castro, M.; López-Romero, J. M.; Mendoza, S.; Manzano-Ramírez, A. Anti-oxidants in Traditional Mexican Medicine and Their Applications as Antitumor Treatments. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Cianca, S. I.; González-Campos, R. E.; Mejía Méndez, J. L.; Sánchez Arreola, E.; Juárez, Z. N.; Hernández, L. R. Anticancer Properties of Mexican Medicinal Plants: An Updated Review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2023, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobo-Herrera, NJ; Jacobo-Herrera, FE; Zentella-Dehesa, A; Andrade-Cetto, A; Heinrich, M; Pérez-Plasencia, C. Medicinal plants used in Mexican traditional medicine for the treatment of colorectal cancer. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 179, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Cubas, J.; San Martin-Martínez, E.; Quiroz-Reyes, C. N.; Casañas-Pimentel, R. G. Cytotoxic Effect of Semialarium mexicanum (Miers) Mennega Root Bark Extracts and Fractions against Breast Cancer Cells. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2018, 24, 1185–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres-Castillo, D.; Mena-Rejón, G. J.; Cedillo-Rivera, R.; Quijano, L. 21β-Hydroxy-Oleanane-Type Triterpenes from Hippocratea excelsa. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo Leon, J. A.; Ruiz Ciau, D. V.; Coral Martinez, T. I.; Cantillo Ciau, Z. O. Comparative Fingerprint Analyses of Extracts from the Root Bark of Wild Hippocratea excelsa and “Cancerina” by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2015, 38, 3870–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, W. M. N. H. W. A Systematic Review of Botany, Phytochemicals and Pharmacological Properties of “Hoja Santa” (Piper auritum Kunth). Z. Naturforsch. C 2020, 76, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar-Guadarrama, A. B.; Rios, M. Y. Flavonoids, Sterols and Lignans from Cochlospermum vitifolium and Their Relationship with Its Liver Activity. Molecules 2018, 23, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Muñoz, E. P.; Antunes-Ricardo, M.; Martínez-Ávila, M.; Guajardo-Flores, D. Eryngium Species as a Potential Ally for Treating Metabolic Syndrome and Diabetes. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 878306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, D. J.; Cragg, G. M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.cym2fw (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.vh2rm7 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.7stc5p (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.4rg5pk (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- El Mannoubi, I. Impact of Different Solvents on Extraction Yield, Phenolic Composition, In Vitro Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of Deseeded Opuntia stricta Fruit. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appl. Sci. 2023, 9, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento-Filha, M. J.; Torres-Rêgo, M.; Daniele-Silva, A.; de Queiroz-Neto, M. F.; Rocha, H. A. O.; Camara, C. A.; Araújo, R. M.; da Silva-Júnior, A. A.; Silva, T. M. S.; Fernandes-Pedrosa, M. de F. Phytochemical Analysis by UPLC-QTOF-MS/MS and Evaluation of Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of the Extract and Fractions from Flowers of Cochlospermum vitifolium. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 148, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, R. M.; Perez, S.; Zavala, M. A.; Salazar, M. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of the Bark of Hippocratea excelsa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1995, 47, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davì, F.; Taviano, M. F.; Acquaviva, R.; et al. Chemical Profile, Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activity of a Phenolic-Rich Fraction from the Leaves of Brassica fruticulosa subsp. fruticulosa (Brassicaceae) Growing Wild in Sicily (Italy). Molecules 2023, 28, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, M. D.; Kang, T. J.; Lee, C. H.; Lee, A. Y.; Noh, M. HaCaT Keratinocytes and Primary Epidermal Keratinocytes Have Different Transcriptional Profiles of Cornified Envelope-Associated Genes to T Helper Cell Cytokines. Biomol. Ther. (Seoul) 2012, 20, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, F. L.; Smiley, J.; Russell, W. C.; Nairn, R. Characteristics of a Human Cell Line Transformed by DNA from Human Adenovirus Type 5. J. Gen. Virol. 1977, 36, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topics, ScienceDirect. HEK293 Cell Line; Elsevier; Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/hek293-cell-line (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Keyif, B.; Hacioglu, C. Boric Acid Suppresses Cell Survival by Triggering Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Autophagy in Cervical Cancers. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2025, 29, e70740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutler, J. A. Natural Products as a Foundation for Drug Discovery. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2019, 86, e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, J. J.; Paine, M. F.; McCune, J. S.; Oberlies, N. H.; Cech, N. B. Selection and Characterization of Botanical Natural Products for Research Studies: A NaPDI Center Recommended Approach. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2019, 36, 1196–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutler, J. A. Natural Products as a Foundation for Drug Discovery. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2009, 46, 9.11.1–9.11.21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwell, M.; Rahman, P. K. Medicinal Plants: Their Use in Anticancer Treatment. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2015, 6, 4103–4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, W. H.; Baban, M. M.; Bulbul, M. F.; Al-Zaidaneen, E.; Allan, A.; Al-Rousan, E. W.; Ahmad, R. H. Y.; Alshaeri, H. K.; Alasmari, M. M.; Law, D. Natural Products and Altered Metabolism in Cancer: Therapeutic Targets and Mechanisms of Action. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Montaño, J. M.; Martínez-Sánchez, S. M.; Jiménez-González, V.; Burgos-Morón, E.; Guillén-Mancina, E.; Jiménez-Alonso, J. J.; Díaz-Ortega, P.; García, F.; Aparicio, A.; López-Lázaro, M. Screening for Selective Anticancer Activity of 65 Extracts of Plants Collected in Western Andalusia, Spain. Plants 2021, 10, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Lázaro, M. A Simple and Reliable Approach for Assessing Anticancer Activity In Vitro. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015, 22, 1324–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Lázaro, M. Two Preclinical Tests to Evaluate Anticancer Activity and to Help Validate Drug Candidates for Clinical Trials. Oncoscience 2015, 2, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lázaro, M. How Many Times Should We Screen a Chemical Library to Discover an Anticancer Drug? Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedokun, K. A.; Imodoye, S. O.; Bello, I. O.; Lanihun, A.-A.; Bello, I. O. Therapeutic Potentials of Medicinal Plants and Significance of Computational Tools in Anti-Cancer Drug Discovery. In Phytochemistry, Computational Tools and Databases in Drug Discovery; Egbuna, C., Rudrapal, M., Tijjani, H., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 393–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandour, Y. M.; Refaat, E.; Hassanein, H. D. Anticancer Activity, Phytochemical Investigation and Molecular Docking Insights of Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Fruits. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, R.; Figueroa, M.; Navarrete, A.; Rivero-Cruz, I. Chemistry and Biology of Selected Mexican Medicinal Plants. Prog. Chem. Org. Nat. Prod. 2019, 108, 1–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, K.B.; Özmen, Ö.; Öztürk Civelek, D.; Şenol, H.; Sönmez, F. Exploring Anti-Cancer Properties of New Triazole-Linked Benzenesulfonamide Derivatives against Colorectal Carcinoma: Synthesis, Cytotoxicity, and In Silico Insights. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2025, 119, 118060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.T.; Tan, Y.J.; Oon, C.E. Benzimidazole and Its Derivatives as Cancer Therapeutics: The Potential Role from Traditional to Precision Medicine. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 478–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.; Dai, C.; Wu, Y.; et al. Betulonic Acid: A Review on Its Sources, Biological Activities, and Molecular Mechanisms. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 998, 177518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Similie, D.; Minda, D.; Bora, L.; et al. An Update on Pentacyclic Triterpenoids Ursolic and Oleanolic Acids and Related Derivatives as Anticancer Candidates. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T. Squalene: Potential Chemopreventive Agent. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2000, 9, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.W.P.E.; Almeida, T.C.; Teixeira, M.S.D.S.; et al. Antiproliferative Effects of the Triterpene Ursolic Acid Natural Product in Bladder and Ovarian Tumor Cell Lines. Drug Dev. Res. 2025, 86, e70172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemli, E.; Saricaoglu, B.; Kirkin, C.; et al. Chemopreventive and Chemotherapeutic Potential of Betulin and Betulinic Acid: Mechanistic Insights from In Vitro, In Vivo and Clinical Studies. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 10059–10069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Similie, D.; Minda, D.; Bora, L.; Kroškins, V.; Lugiņina, J.; Turks, M.; Dehelean, C.A.; Danciu, C. An Update on Pentacyclic Triterpenoids Ursolic and Oleanolic Acids and Related Derivatives as Anticancer Candidates. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidooki, S.H.; Quero, J.; Sánchez-Marco, J.; et al. Squalene in Nanoparticles Improves Antiproliferative Effect on Human Colon Carcinoma Cells through Apoptosis by Disturbances in Redox Balance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zheng, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, D.P.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.M.; Li, H.B. Natural Polyphenols for Prevention and Treatment of Cancer. Nutrients 2016, 8, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyahya, A.; Omari, N.E.; Bakrim, S.; Hachlafi, N.E.; Balahbib, A.; Wilairatana, P.; Mubarak, M.S. Advances in Dietary Phenolic Compounds to Improve Chemosensitivity of Anticancer Drugs. Cancers 2022, 14, 4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singaravelan, N.; Tollefsbol, T.O. Polyphenol-Based Prevention and Treatment of Cancer through Epigenetic and Combinatorial Mechanisms. Nutrients 2025, 17, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yammine, A.; Namsi, A.; Vervandier-Fasseur, D.; Mackrill, J.J.; Lizard, G.; Latruffe, N. Polyphenols of the Mediterranean Diet and Their Metabolites in the Prevention of Colorectal Cancer. Molecules 2021, 26, 3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, C.; Nicoletti, I. Analysis of Apoptosis by Propidium Iodide Staining and Flow Cytometry. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 1458–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atale, N.; Gupta, S.; Yadav, U.; Rani, V. Cell-Death Assessment by Fluorescent and Nonfluorescent Cytosolic and Nuclear Staining Techniques. J. Microsc. 2014, 255, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blowman, K.; Magalhães, M.; Lemos, M.; Cabral, C.; Pires, I. Anticancer Properties of Essential Oils and Other Natural Products. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 3149362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, S.; Tiezzi, A.; Laghezza Masci, V.; Ovidi, E. Natural Products for Human Health: An Historical Overview of the Drug Discovery Approaches. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 1926–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, B. J.; Ataurima, I. M.; Inca, L. S.; Llica, E. R.; Cotos, M. R.; Manrique, P. E.; Alfaro, K. M. Evaluación del contenido de polifenoles totales y la capacidad antioxidante de los extractos etanólicos de los frutos de aguaymanto (Physalis peruviana L.) de diferentes lugares del Perú. Rev. Soc. Quím. Perú 2016, 82, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Family | Voucher | Plant organ used | Collection date | Collection site |

|

Cochlospermum vitifolium |

Bixaceae | 28904 | trunk and stem | 4/02/2024 | Lomas del Carril neighborhood of Temixco, Morelos |

|

Eryngium heterophyllum |

Apiaceae | 29010 | whole plant without roots | 6/02/2024 | State Of Mexico |

| Piper auritum | Piperaceae | 28935 | aerial plant parts | 7/02/2024 | Álvaro Leonel, La Joya, Morelos |

|

Semialarium mexicanum |

Celastraceae | 32942 | trunk and stem | 15/02/2024 | Los Naranjos, Guerrero |

| Plant species | Hexane | Acetone | Methanol | |||

| Extract (g) | Extract yields (%) | Extract (g) | Extract yields (%) | Extract (g) | Extract yields (%) | |

| Cochlospermum vitifolium | 0.73 | 0.49 | 1.92 | 1.28 | 12.08 | 9.39 |

| Eryngium heterophyllum | 1.92 | 1.28 | 3.36 | 2.24 | 14.71 | 9.81 |

| Piper auritum | 3.21 | 2.14 | 24.03 | 4.17 | 24.30 | 16.2 |

| Semialarium mexicanum | 1.71 | 1.14 | 6.90 | 4.60 | 14.29 | 9.53 |

| Extract |

Total phenolic content (mg GAE/g extract) |

| EM | 33.78 ± 1.26 |

| CA | 56.51 ± 0.46 |

| SM | 180.06 ± 1.55 |

| PM | 54.82 ± 1.27 |

| CA | 231.19 ± 2.00 |

| EA | 40.79 ± 0.82 |

| SA | 205.98 ± 2.87 |

| PA | 45.68 ± 1.02 |

| Plant species | Extract | Cancerous cell lines | |||||

| HeLa | SiHa | HepG2 | PC-3 | H1299 | MCF-7 | ||

| Eryngium heterophyllum | Hexane | 24.58 ± 4.0 | 20.4 ± 2.4 | 34.0 ± 4.5 | 28.3±4.1 | 29.5 ± 7.5 | 32.7 ± 3.7 |

| Acetone | 29.35 ± 3.9 | 29.4 ± 3.5 | 32.6 ± 3.9 | 40.2± 6.9 | 45.7 ± 2.5 | 49.3 ± 3.5 | |

| Methanolic | 24.5 ± 3.6 | 27.45± 3.7 | 40.4 ± 3.7 | 29.8±5.7 | 65.7 ± 7.2 | 59.3 ± 3.7 | |

| Cochlospermun vitifolium | Hexane | 59.5 ± 2.59 | 55.78± 4.0 | 82.6 ± 2.4 | 68.4±2.6 | 78.5 ± 3.2 | 58.3 ± 6.1 |

| Acetone | 39.6 ± 4.1 | 42.3± 5 | 45.5 ± 5.1 | 32.1±3.7 | 62.1 ± 4.5 | 42.3 ± 2.4 | |

| Methanolic | 19.19± 3.3 | 20.45± 2.5 | 20.4 ± 2.3 | 30.1±3.2 | 35.1 ± 5.7 | 30.1 ± 6.2 | |

|

Semialarium mexicanum |

Hexane | 15.9 ± 1.8 | 17.16±2.8 | 24.7.± 2.7 | 23.8±4.5 | 38.02 ± 10.1 | 26.48 ± 6.4 |

| Acetone | 19.3 ± 2.8 | 21.78±3.2 | 37.0 ± 2.7 | 29.5±5.5 | 45 ± 4.3 | 29.4 ± 3.3 | |

| Methanolic | 21.2 ± 3.1 | 23.5 ± 2.7 | 24.4 ± 3.7 | 51.2±4.8 | 41 ± 7.2 | 66.8 ± 6.3 | |

| Piper auritum | Hexane | 220.2 ± 4.6 | 240.7 ± 7.1 | 199.5 ± 2.9 | 201.4±2.4 | 245 ± 20.7 | 289.9 ± 14.5 |

| Acetone | 230.6 ± 2.0 | 230.6 ± 2.0 | 212.7 ± 3.3 | 251.7±2.2 | 277.1 ± 27.4 | 256.2 ± 16.9 | |

| Methanolic | 50.7 ± 5.1 | 75.5 ± 5.1 | 160.4 ± 2.2 | 78.5±2.7 | 121.4 ± 14.5 | 135.78 ± 12.8 | |

| Paclitaxel nM | 15.7 ± 1.6 | 25.7 ± 2.2 | 68.7 ± 17.9 | 70.56 ±4.9 | 70.79 ± 2.7 | 108.52 ± 7.2 | |

| Plant species | Extract |

Human foreskin fibroblasts |

Primary uterine fibroblast cells | Immortalized human keratinocytes |

Embryonic kidney immortalized cell line |

|

| HFF-1 | HUF | HaCat | HeK-293 | |||

|

Semialarium mexicanum |

Hexane | 79.46±5.5 | 89.71± 4.3 | 53.53.±6.2 | 40.4 ±5.5 | |

| Acetone | 114.2±6.1 | 119.2±4.7 | 61.59 ±6.9 | 49.17±5.3 | ||

| Methanolic | 113.5±5.4 | 122.4 ±4.2 | 93.79 | 89.2±2.7 | ||

|

Eryngium heterophyllum |

Hexane | 117.3±5.9 | 75.8±5.1 | 58.85±6.0 | 41.67±6.7 | |

| Acetone | *ND | 113.9±3.7 | 104.0±3.2 | 75.41±6.1 | ||

| Methanolic | 108.5± 4.3 | 88.6±5.0 | 75.25±6.2 | 70.2±4.4 | ||

| Paclitaxel (nM) | *ND | 75.7±5.0 | 65.79±5.0 | 37.8±2.5 | ||

| Plant species | Extract | HeLa | SiHa cells | ||||

| HFF-1 | HaCat | HUF | HFF-1 | HaCat | HUF | ||

|

Eryngium heterophyllum |

Hexane |

4.77 | 1.27 | 3.05 | 5.75 | 2.88 | 3.75 |

| Acetone | *ND | 3.5 | 3.87 | *ND | 3.5 | 3.8 | |

| Methanolic | 4.42 | 3.07 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 2.74 | 3.22 | |

|

Semialarium Mexicanum |

Hexane | 4.99 | 3.36 | 5.64 | 4.6 | 3.11 | 5.22 |

| Acetone | 5.92 | 3.19 | 6.17 | 5.24 | 2.82 | 5.48 | |

| Methanolic | 5.35 | 4.42 | 5.77 | 4.8 | 3.99 | 5.2 | |

| Paclitaxel | *ND | 4.18 | 4.82 | *ND | 2.55 | 2.94 | |

| No | Name | *RT | Peak area % | Match % |

| 1 | Benzene, 1-ethyl-2,4-dimethyl- | 5.95 | 3.05 | 88.3 |

| 2 | Benzene, 1-ethyl-3,5-dimethyl- | 6.06 | 3.72 | 94.5 |

| 3 | Benzene, 2-ethyl-1,4-dimethyl- | 6.41 | 1.51 | 92.4 |

| 4 | Benzene, 1,2,3,5-tetramethyl- | 6.58 | 7.25 | 95.5 |

| 5 | Benzene, 1,2,4,5-tetramethyl- | 6.65 | 23.90 | 97.4 |

| 6 | Indan, 1-methyl- | 6.96 | 1.55 | 77.1 |

| 7 | Benzene,4-ethenyl-1,2-dimethyl- | 7.13 | 4.01 | 90.5 |

| 8 | 4-Ethylbenzoic acid, tridec-2-ynyl ester | 8.03 | 1.80 | 85.7 |

| 9 | Cyanic acid, ethyl ester | 10.94 | 2.29 | 84.9 |

| 10 | Hexadecanoic acid, ethyl ester | 19.47 | 0.50 | 78.8 |

| 11 | Squalene | 27.72 | 11.43 | 95.6 |

| 12 | 12-Oleanen-3-yl acetate, (3.alpha.)- | 29.07 | 3.77 | 79.6 |

| 13 | Stigmasta-3,5-diene | 29.69 | 2.23 | 76.7 |

| 14 | β.-Amyrone | 31.36 | 1.70 | 75.7 |

| 15 | Friedelan-3-one | 32.79 | 5.73 | 89.6 |

| RT = Retention Time* | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).