4.7.1. End-to-End Architectures

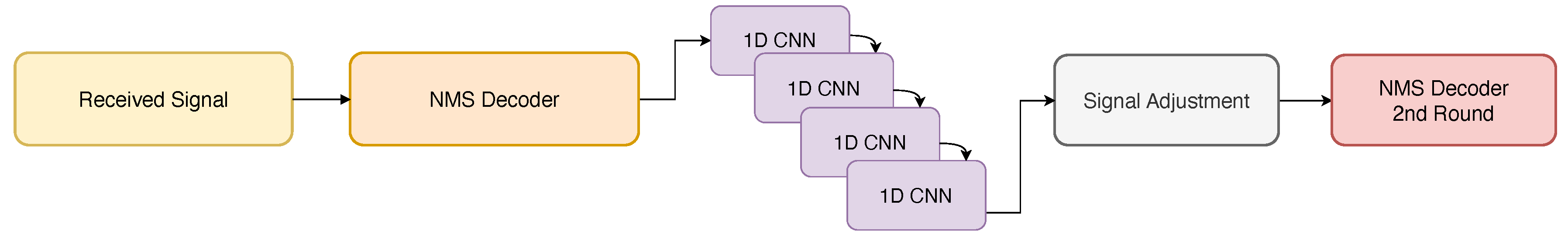

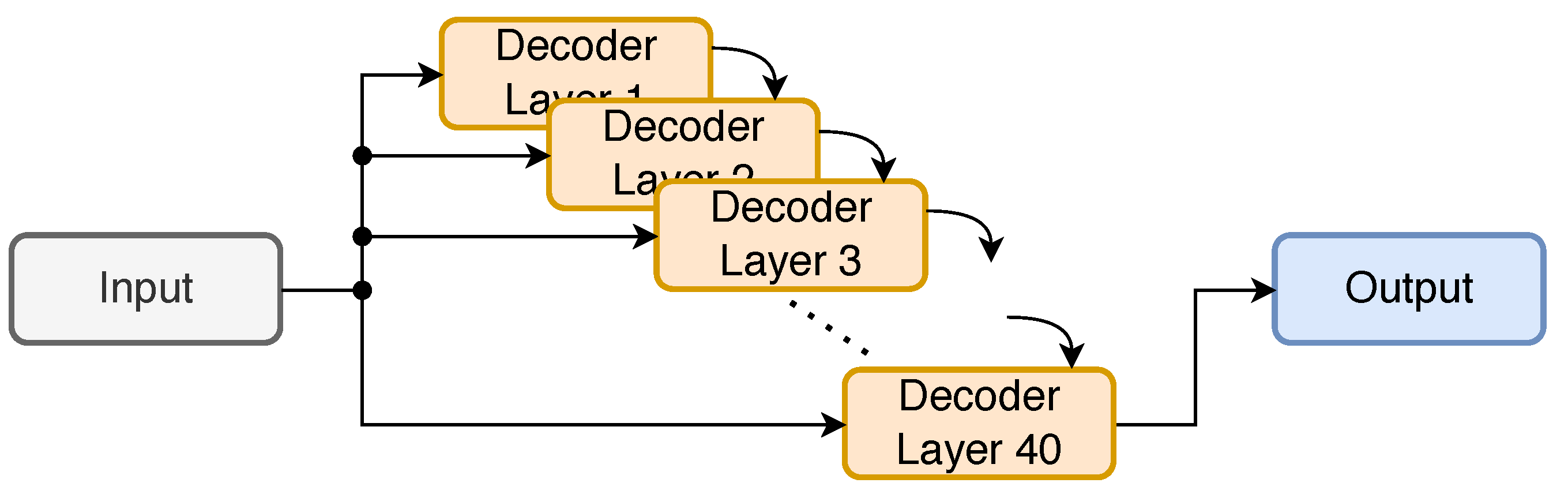

The work shown in [

91] proposes a DL receiver method for MIMO systems, eliminating the need for pilots. Using the DeepRx CNN receiver from [

33] along with using a fully learned multiplicative transformation introduced by [

92], the ML receiver processes the inputs and subsequently outputs the LLRs for each spatial stream. The transmit constellations are learned using the DeepRx receiver, and each transmitted signal is selected and learned from a constellation generated by neural networks that transform standard QAM points. Separate constellations are learned for each MIMO layer generated by linearly combining transformations that the network has learned. The learned constellations are normalized to have zero mean and unit energy, ensuring equal transmit power compared to conventional OFDM systems. The transformation networks utilize four fully connected hidden layers with tanh activations [

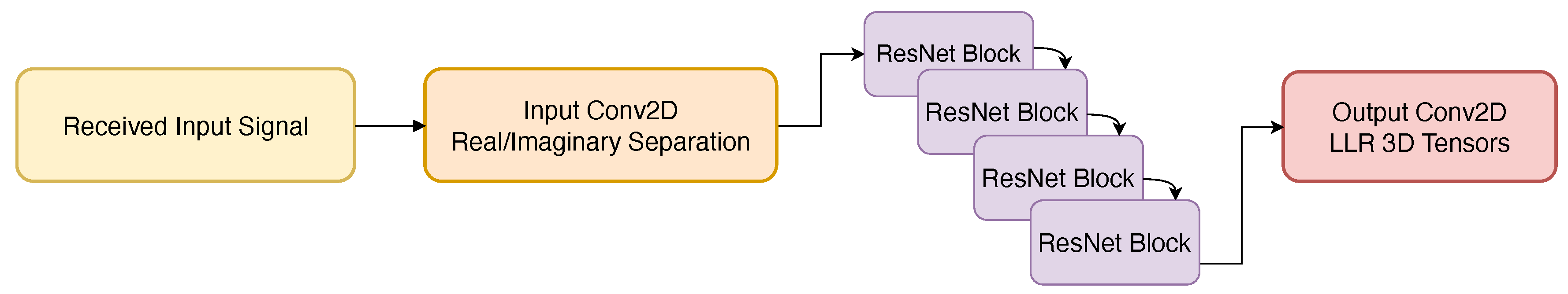

93] to map the amplitude and phase of the QAM symbols, with each layer containing 16-32 neurons. The weighting network consists of four hidden layers, each with 8 to 16 neurons and ReLU activation functions. The output layer uses a softmax activation function to ensure a unit-sum weighting. The input of the DeepRx model consists of the received MIMO-OFDM signal over one slot, represented by samples across multiple subcarriers and OFDM symbols. A larger MIMO DeepRx CNN, which ranges from 512 to 2048 ResNet blocks, outputs LLRs that are passed to an LPDC decoder to recover the information bits. A loss function is introduced to prevent the formation of tightly clustered constellation points, which can limit the bit transformation per symbol using the ReLU function. The structure of the DL model is shown in

Figure 12.

The training is performed using the Adam optimizer with a BCE loss calculated between the transmitted and detected bits, along with a distance-based loss to help prevent convergence due to the large constellations used. The weight factor

is set to 0.1 for 16-QAM and 0.05 for 64-QAM. The batch size is set to 10 with a learning rate of 0.0001. The carrier frequency is set to 3.5 GHz, the number of subcarriers is set to 72, the subcarrier spacing is 30 kHz apart, and the number of transmitter and receiver antennas is 2 and 4, respectively. The DL model is compared against established methods such as K-Best [

94] using a perfect channel state, and Demodulation Reference Signal (DMRS) [

95] channel state, and the evaluation focuses on BLER over SNR across the range of 0 to 14 dB. The proposed method achieves a low BLER across the entire SNR range without requiring any pilots. While it does not fully surpass conventional methods, it demonstrates strong effectiveness in pilotless signal detection.

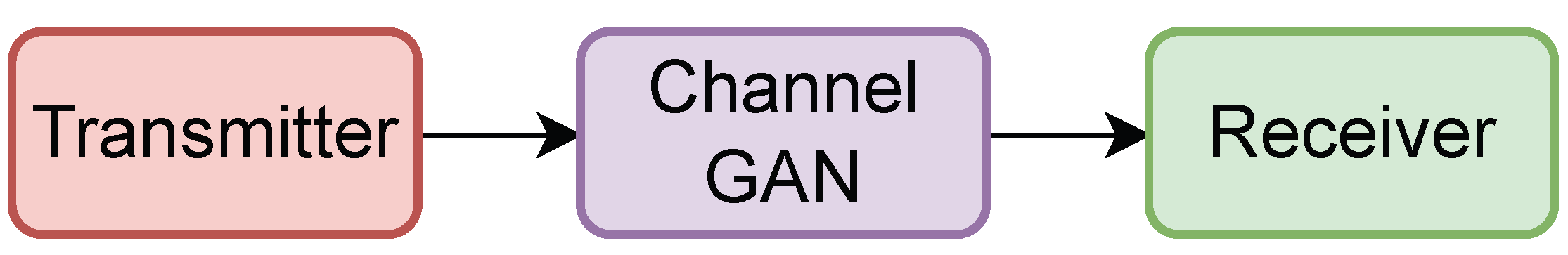

By contrast, the end-to-end wireless communication system presented by [

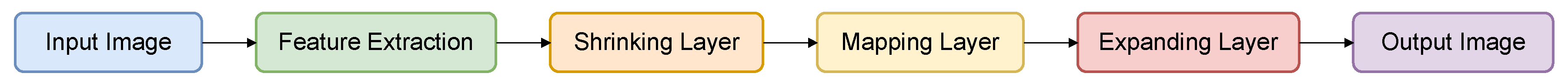

96] is built using DNNs for both the transmitter and receiver, eliminating the need for traditional encoding, modulation, decoding, and demodulation blocks. A conditional generative adversarial network (GAN) models the channel in a data-driven manner, where the generator produces channel outputs conditioned on the transmitted signals and received pilot symbols, while the discriminator distinguishes between real and generated channel outputs. To address the challenge of high-dimensional complexity, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are employed in the transmitter, receiver, and channel GAN, enabling efficient learning of long block sequences. The system optimizes an end-to-end cross-entropy loss between the transmitted and recovered information, with iterative training involving sequential updates to the receiver DNN, transmitter DNN, and conditional GAN. For smaller block sizes, Fully Connected Networks (FCNs) are employed, where both the transmitter and receiver DNNs comprise two hidden layers with 32 neurons each. The generator consists of three hidden layers with 128 neurons, and the discriminator comprises three hidden layers with 32 neurons each. For larger block sizes, CNNs are utilized: the transmitter includes an input layer, three convolutional layers with ReLU activation, and a convolutional layer, all followed by a power normalization layer, with varying output sizes. The receiver is composed of seven convolutional layers with ReLU activation, followed by a convolutional layer with Sigmoid activation, each with varying output sizes. The generator consists of three convolutional layers with ReLU activation, followed by a convolutional layer with a different output size for each. The discriminator comprises four convolutional layers with ReLU activation and two fully connected layers with ReLU and Sigmoid activations, respectively, each with distinct output sizes. A high-level overview is expressed in

Figure 13.

This end-to-end system was evaluated on AWGN, Rayleigh fading, and frequency-selective multi-path channels. The learning rate for the FCN is set to 0.0001 for the transmitter, receiver, and discriminator. The input block sizes are 64 bits and 128 bits, the code rate is set to 0.5, with 16 bits for padding between each block. Across all channels, the deep learning approach achieves similar or better BER and BLER compared to conventional methods, while also benefiting from lower computational time due to the efficient CNN architectures.

Another MIMO-OFDM DL receiver is proposed using a transformer called SigT [

97]. The SigT transformer converts the received signals into tokens by reshaping and permuting them based on physical properties, such as the number of antennas and subcarriers. It groups each antenna’s subcarriers into vectors, which serve as the tokens that feed into the transformer encoder [

98]. The transformer encoder uses multi-head self-attention to capture the complex relations among the antennas and enhance valuable shared information. Then, the outputs are fed into convolutional layers, combined, and passed through a two-layer MLP, where the MSE is computed to update the weights.

For emulation, the framework is configured with a frequency of 3.5 GHz, 256 subcarriers, 4 transmitted antennas, 16 received antennas, and each containing one information symbol. The dataset for testing has 2560 signals. The learning rate for the Adam optimizer is 0.0001 with

,

, and

. The SigT transformer evaluates accuracy over the SNR range of 0 to 40, comparing against FCDNN [

99] and CSINet [

100]. The results show that the SigT transformer outperforms previous end-to-end receiver methods, demonstrating the effectiveness of DL in improving MIMO signal recovery.

An additional deep learning model, Comm-Transformer, was proposed for OFDM systems by [

101]. The Comm-Transformer incorporates an attention block with channel positional encoding to focus on subcarriers, using attention weights computed via an embedded Gaussian function. This is combined with multiple dual-1D convolutional blocks for feature extraction, where each convolution block passes through batch normalization to improve training before a second 1D convolution. Max pooling is applied to capture both local and global features, followed by a transpose convolution for up-sampling. The extracted features are then flattened and processed by GRU layers to model dependencies across subcarriers. The network uses a Sigmoid activation with binary cross-entropy loss for bit recovery, while mean squared error (MSE) is used for channel estimation.

The Comm-Transformer is trained under all sub-types of TDL channels [

102] with 64 subcarriers, QPSK modulation, a carrier frequency of 4 GHz, Doppler shift of 111.18 Hz, CP length of 16, varying numbers of pilots (8, 16 or 64), 2 sub-frames, and a block length of 128 at a mobile speed of 8.32 m/s. Training utilizes a batch size of 256 over 1000 epochs, with a kernel size of 1×3 for the dual 1D convolutional layers, and employs the ADAM optimizer. Evaluation is performed in terms of NMSE over an SNR range of 10 to 30 dB against MMSE, LS, LSTM [

103], and DNN [

99], and in terms of BER over SNR against MMSE-GAMP64 [

104], LS-GAMP64 [

104], LSTM, DNN, and DeepRx [

33]. Overall, the Comm-Transformer outperforms traditional and previously proposed deep learning methods in both NMSE and BER over TDL channels, while maintaining computational efficiency.

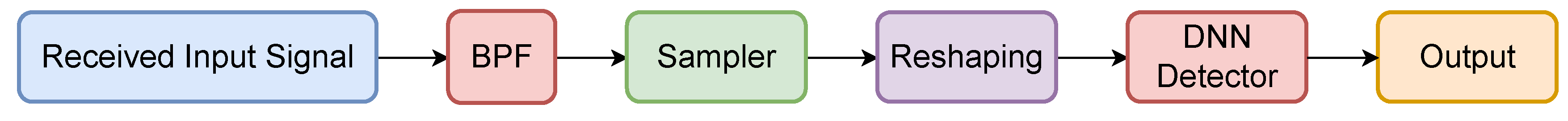

A deep learning model for the IEEE 802.11bd receiver was developed for next-generation vehicle-to-everything (NGV) communications [

105], comprising two main components: frame capture and data-driven symbol recovery DNN. The frame capture module exploits the repeated sequence structure of the Legacy Short Training Field (L-STF) in the PPDU preamble, which contains 10 repeated sequences, and uses an autocorrelation method to mitigate Doppler spread and multipath effects. The data-driven DNN processes the Next Generation V (NGV) PPDU to recover transmitted symbols. Its architecture includes multiple convolutional blocks (ConvBlockA, ConvBlockB, IdentityBlock), while an OutputBlock extracts features using dense and softmax layers to produce symbol decisions. Data structure optimization is applied to both training and reference data.

For training, the Adam optimizer is used with a learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 512, and 20 epochs. The proposed model is evaluated against traditional LS and Zero Forcing (ZF) algorithms under BPSK and QPSK modulation for OFDM. SER is measured over an SNR range of 4 to 20 dB across rural LoS, highway LoS, and urban LoS channels. The results show that the DL model significantly outperforms conventional methods, highlighting the advantages of deep learning for NGV communication.

Table 8 measures the effectiveness of end-to-end DL receiver models compared against conventional and DL methods.

4.7.2. Other Related DL Approaches

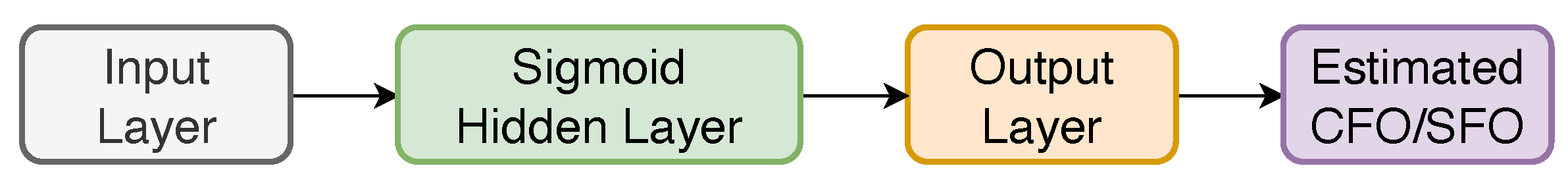

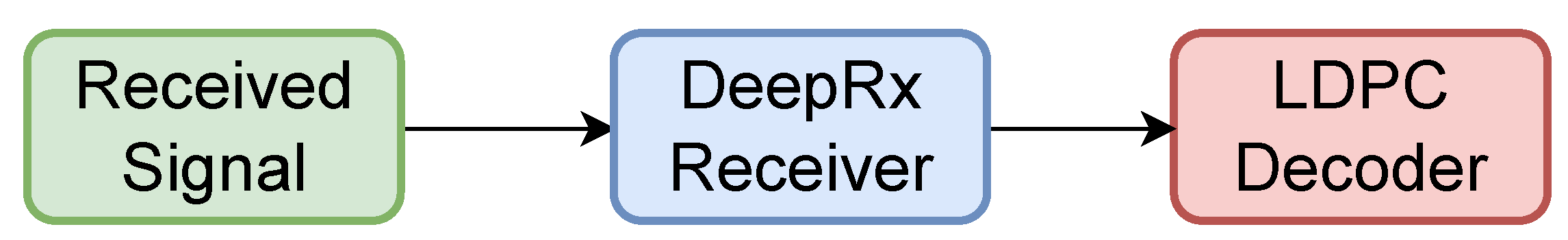

An end-to-end deep learning–based OFDM receiver by [

106] jointly handles synchronization, CFO estimation, channel estimation, equalization, and demodulation using a single auto-encoder network. Their simulations and Software-Defined Radio (SDR) experiments show moderate BLER improvements over conventional receivers at given SNR and improved robustness to impairments. However, this work is not emphasized in the main discussion, as other papers report stronger overall performance.

A paper by [

107] introduces DeepReceiver, an end-to-end deep learning–based wireless receiver that replaces the traditional receiver chain with a single neural network. A 1D convolutional DenseNet enables multi-bit recovery and supports blind reception across multiple modulation and coding schemes. While the method improves BER over conventional receivers under various impairments, its performance gains are limited compared to more recent approaches.

An end-to-end OFDM receiver called AIDER [

108] uses an attentive deep convolutional network that learns directly from time-domain signals while exploiting the cyclic prefix. The model achieves improved BER over traditional receivers, particularly in channels with large delay spreads. However, its performance gains are modest compared to more recent DL-based receivers, which offer stronger SNR improvements.

TCD-Receiver [

109] is a Transformer-based MIMO-OFDM receiver that performs joint channel estimation and signal detection using an end-to-end multi-head attention approach. The model outperforms LS, MMSE, and CNN-based receivers under challenging conditions such as limited pilot symbols, CP removal, and nonlinear noise, achieving results comparable to MMSE across various SNR.

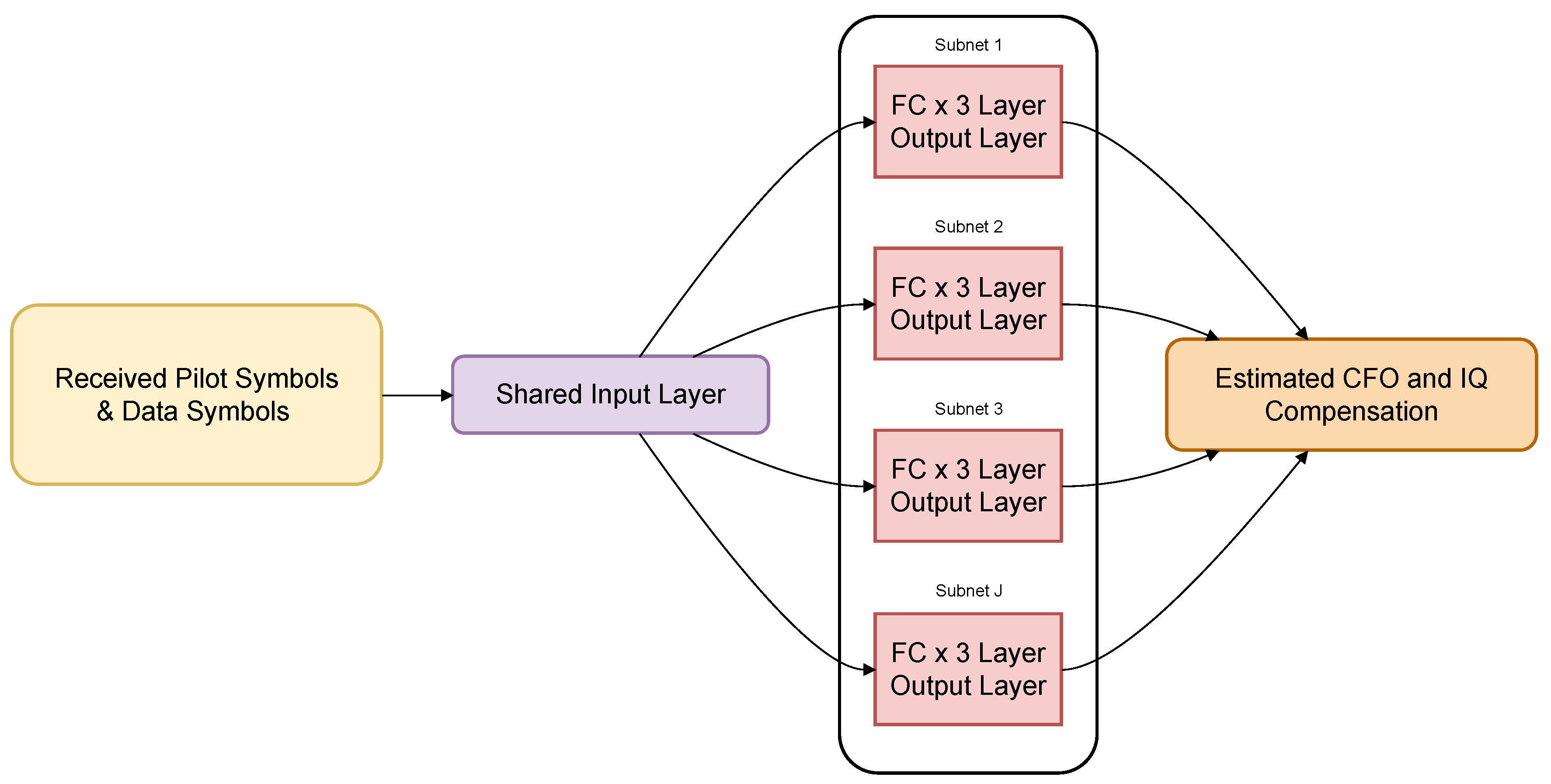

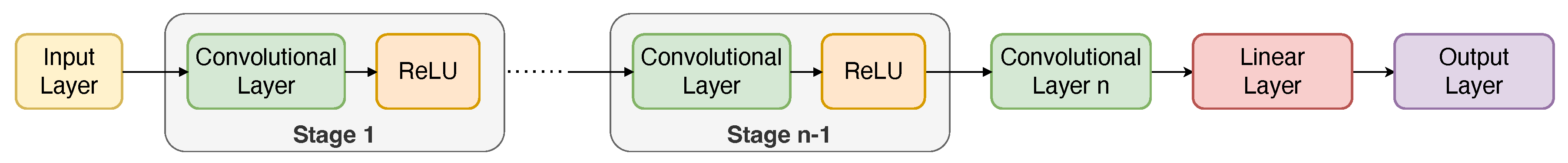

The work shown in [

21] proposes end-to-end deep learning architectures to mitigate multiple hardware impairments in OFDM systems, using DLNN for single-antenna and 2×2 MIMO systems, and ResNet-DCDNN for 2×4 MIMO systems. DNN-based encoders and decoders jointly optimize signal mapping and impairment compensation. Their simulations show that these designs outperform traditional methods under AWGN and Rayleigh channels, with transfer learning addressing time-varying impairments, but the improvements over traditional approaches are lower than those of other papers mentioned in this section.

Another DL receiver design [

110] establishes an intelligent OFDM receiver using a dual-channel CNN (DCNet) that integrates original IQ data with LS channel estimation knowledge, combining domain expertise with data-driven methods. The dual-stream architecture extracts and fuses features to enhance signal recovery, and simulations under various channel models, noise levels, pilot counts, and modulation schemes demonstrate significant BER improvements compared to DenseNet and MobileNetV3-based methods. However, it is outperformed by other recent works.

Additionally, [

111] proposes a Deep Complex-valued Convolutional Neural Network (DCCNN) for OFDM receivers, which recovers information directly from time-domain signals without relying on DFT/IDFT. The model leverages the CP and employs a two-phase transfer learning scheme to train the channel equalizer and demodulator separately, thereby enhancing convergence and robustness in multi-path fading channels. Simulations show that the DCCNN outperforms conventional LS, LMMSE, and Adaptive Linear Minimum Mean Square Error (ALMMSE) estimators, particularly in frequency-selective fading and high SNR scenarios. It is one of the few works that utilized complex-valued neural networks, but it does not match the performance of other DL-based OFDM receiver designs.

The work by [

112] proposes a machine learning–based OFDM receiver designed for extreme mobility scenarios, where severe Doppler shifts induce significant ICI. The receiver uses 2D convolutional ResNet layers to jointly estimate the channel and mitigate ICI, operating directly on the time- and frequency-domain received signals while relying only on sparse pilot reference signals. Simulations in 5G NR uplink scenarios demonstrate that the ML receiver significantly outperforms conventional LMMSE-based receivers, maintaining reliable demodulation even at very high user velocities. However, other recent studies achieve even better overall performance, so this work is highlighted mainly as a demonstration of ML robustness under extreme Doppler conditions rather than the best-performing OFDM receiver.

4.7.3. Performance Analysis of Full Deep Learning Implementations

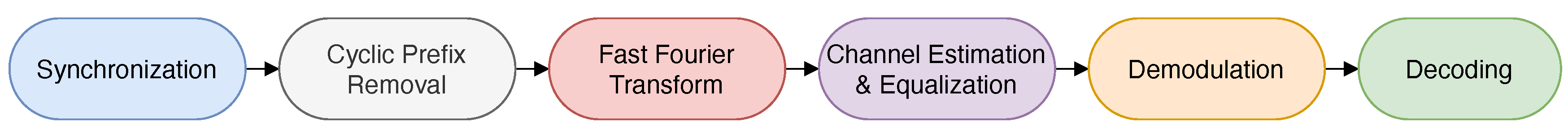

The preceding subsections have examined end-to-end deep learning architectures that aim to replace the entire OFDM receiver pipeline with a single neural network. While these approaches demonstrate impressive performance in controlled scenarios, an alternative paradigm (stage-wise DL enhancement) offers complementary advantages that merit consideration.

Applying DL at each individual stage of an OFDM receiver has been shown to offer significant advantages over both conventional signal processing and monolithic end-to-end approaches. Each stage discussed throughout this survey benefits from the ability of deep learning models to learn complex, nonlinear relationships, adapt to time-varying channels, and mitigate noise and interference. By selectively replacing traditional algorithms with deep learning models at each stage, the receiver becomes more robust and capable of achieving lower error rates and improved signal fidelity while maintaining modularity and interpretability.

Cumulative Benefits of Stage-Wise Integration: Replacing each stage with deep learning ensures that the system is not just a black-box DL receiver, but a fully learning-assisted receiver where every key functional stage is enhanced, yielding cumulative performance improvements across the pipeline. Improved synchronization using DL techniques (

Section 4.1) enhances the accuracy of subsequent stages by providing better-aligned signals for FFT processing. Enhanced channel estimation (

Section 4.4.1) allows the equalization stage (

Section 4.4.2) to produce cleaner symbol estimates by more accurately modeling channel distortions. This, in turn, improves demodulation accuracy (

Section 4.5) and ultimately reduces bit error rate in the decoding stage (

Section 4.6). Operating on real-valued or transformed signal representations, DL modules can efficiently handle both linear and nonlinear distortions, thereby making the receiver more resilient to multipath fading, interference, and low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions.

Advantages Over Monolithic End-to-End Approaches: While end-to-end receivers offer joint optimization benefits, stage-wise DL integration provides several key advantages. First, modularity enables individual stages to be updated, retrained, or replaced without requiring the redesign of the entire receiver, thereby facilitating incremental deployment and maintenance. Second, interpretability is preserved, as the function of each stage remains clearly defined, enabling easier debugging and performance analysis. Third, training complexity is reduced, as each stage can be trained independently on smaller datasets with well-defined objectives, rather than requiring massive end-to-end training. Fourth, hybrid deployment becomes possible, allowing critical stages to use DL while retaining conventional processing where it already performs optimally (e.g., FFT).

Performance Improvements: This stage-wise deep learning integration transforms the OFDM receiver into a fully optimized, flexible, and scalable system, providing substantial improvements in key metrics such as BER, NMSE, MSE, and SER, as demonstrated throughout the individual stage analyses in this section. The synchronization methods reviewed achieve significant reductions in frequency offset estimation error (up to 70.54% improvement in

Section 4.1). Channel estimation techniques reduce NMSE by substantial margins compared to traditional LS and MMSE methods (

Section 4.4.1). Equalization methods demonstrate improved BER performance across diverse channel conditions (

Section 4.4.2). The demodulation and decoding stages demonstrate enhanced robustness to channel impairments and lower computational complexity during inference (

Section 4.5 and

Section 4.6).

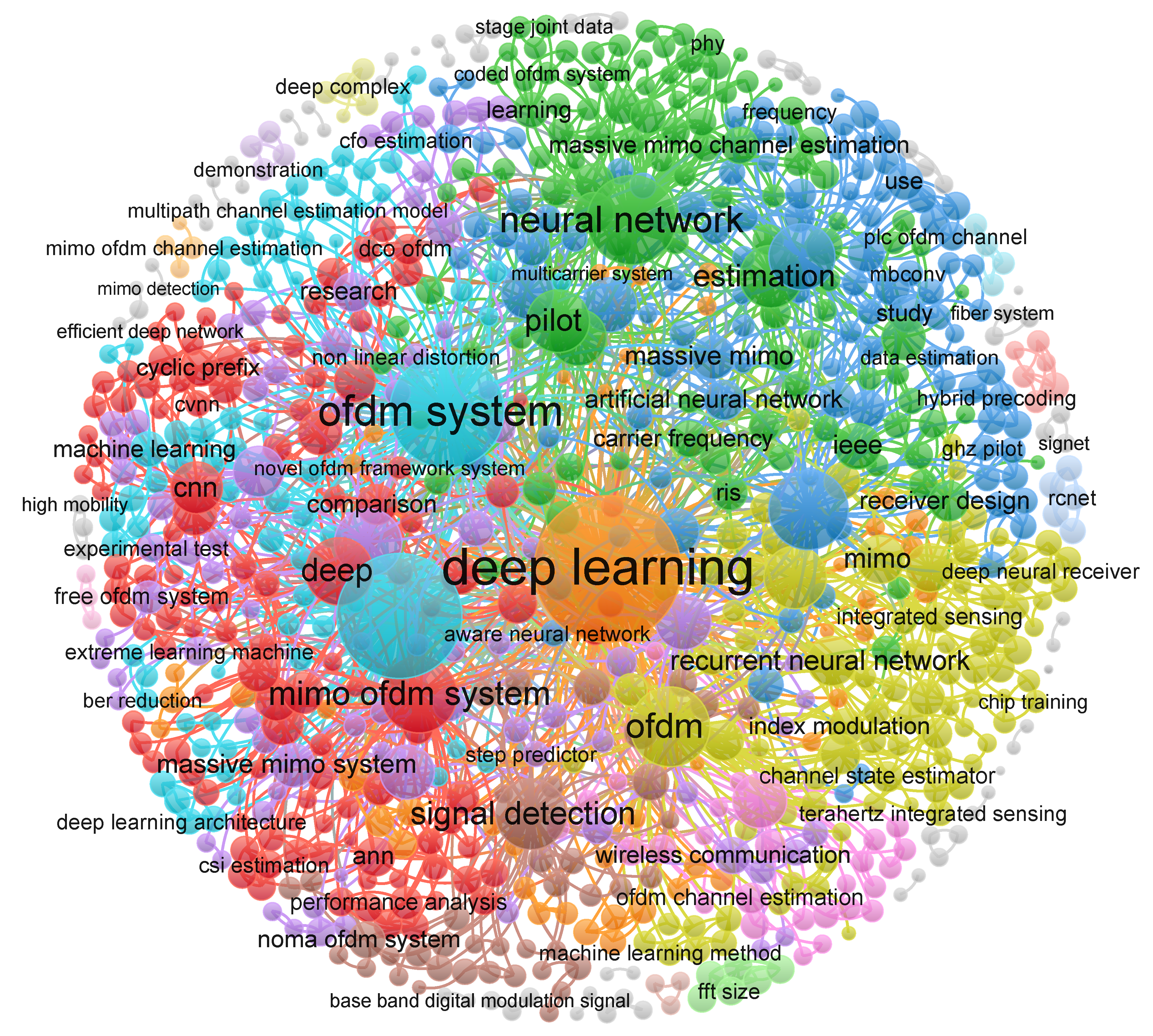

Research Distribution and Gaps: Most studies, as summarized in

Table 1, focus heavily on channel estimation and equalization (116 out of 174 papers, or 66.67%), followed by end-to-end designs (36 papers, 20.69%) and synchronization (8 papers, 4.6%). In contrast, demodulation (7 papers, 4.02%), CP removal (4 papers, 2.3%), decoding (3 papers, 1.72%), and FFT (0 papers) stages are comparatively underexplored. This distribution reflects both the critical importance of channel estimation in wireless systems and the significant challenges it presents, making it a natural focus for DL-based innovation. The absence of DL-based FFT replacements is notable and suggests that highly optimized conventional FFT implementations remain superior for this specific operation. The limited exploration of CP removal and decoding stages represents opportunities for future research.