Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Recently, with advancements in Deep Learning (DL) technology, Radio Frequency (RF) sensing has seen substantial improvements, particularly in outdoor applications. Motivated by these developments, this survey presents a comprehensive review of state-of-the-art RF sensing techniques in challenging outdoor scenarios with practical issues such as fading, interference, and environmental dynamics. We first investigate the characteristics of outdoor environments and explore potential wireless technologies. Then, we study the current trends in applying DL to RF-based systems and highlight its advantages in dealing with large-scale and dynamic outdoor environments. Furthermore, this paper provides a detailed comparison between discriminative and generative DL models in support of RF sensing, offering insights into both the theoretical underpinnings and practical applications of these technologies. Finally, we discuss the research challenges and present future directions of leveraging DL in outdoor RF sensing.

Keywords:

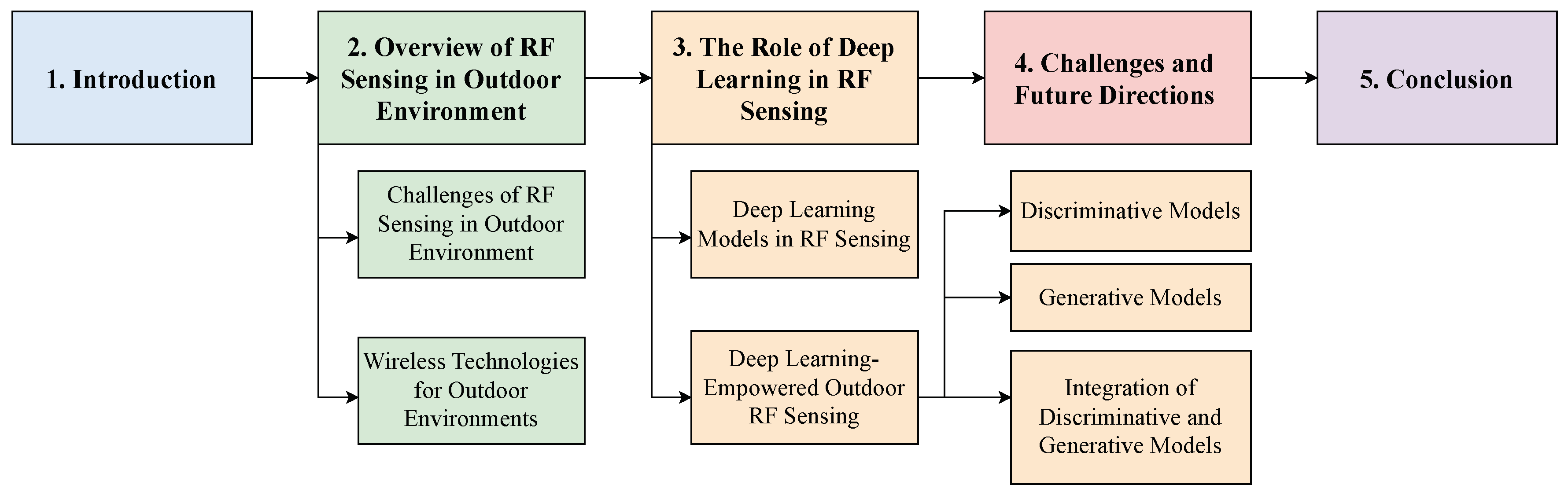

1. Introduction

- Unlike existing surveys, this survey provides a comprehensive review of RF sensing in outdoor environments, identifying key challenges and examining wireless technologies best suited for these settings.

- We offer a detailed analysis of DL approaches, focusing on both generative and discriminative models, and assess their effectiveness in enhancing RF sensing. We also review recent outdoor RF sensing studies utilizing various DL methods, categorizing them by approach, and underlining the specific benefits and limitations of each in distinct scenarios.

- This survey paper explores the existing challenges of leveraging DL in outdoor RF sensing and presents insights and possible solutions for future tendencies.

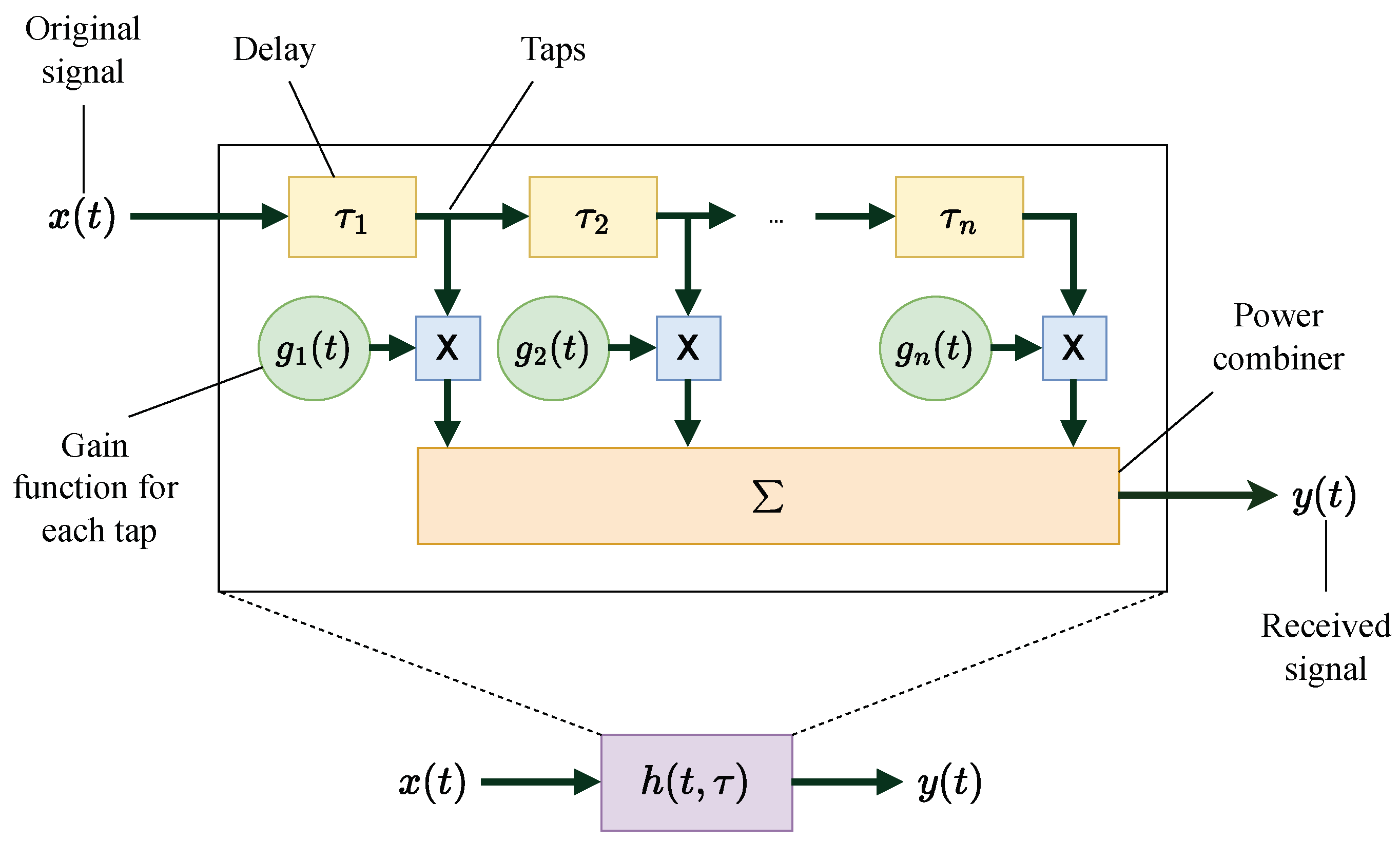

2. Overview of RF Sensing in Outdoor Environments

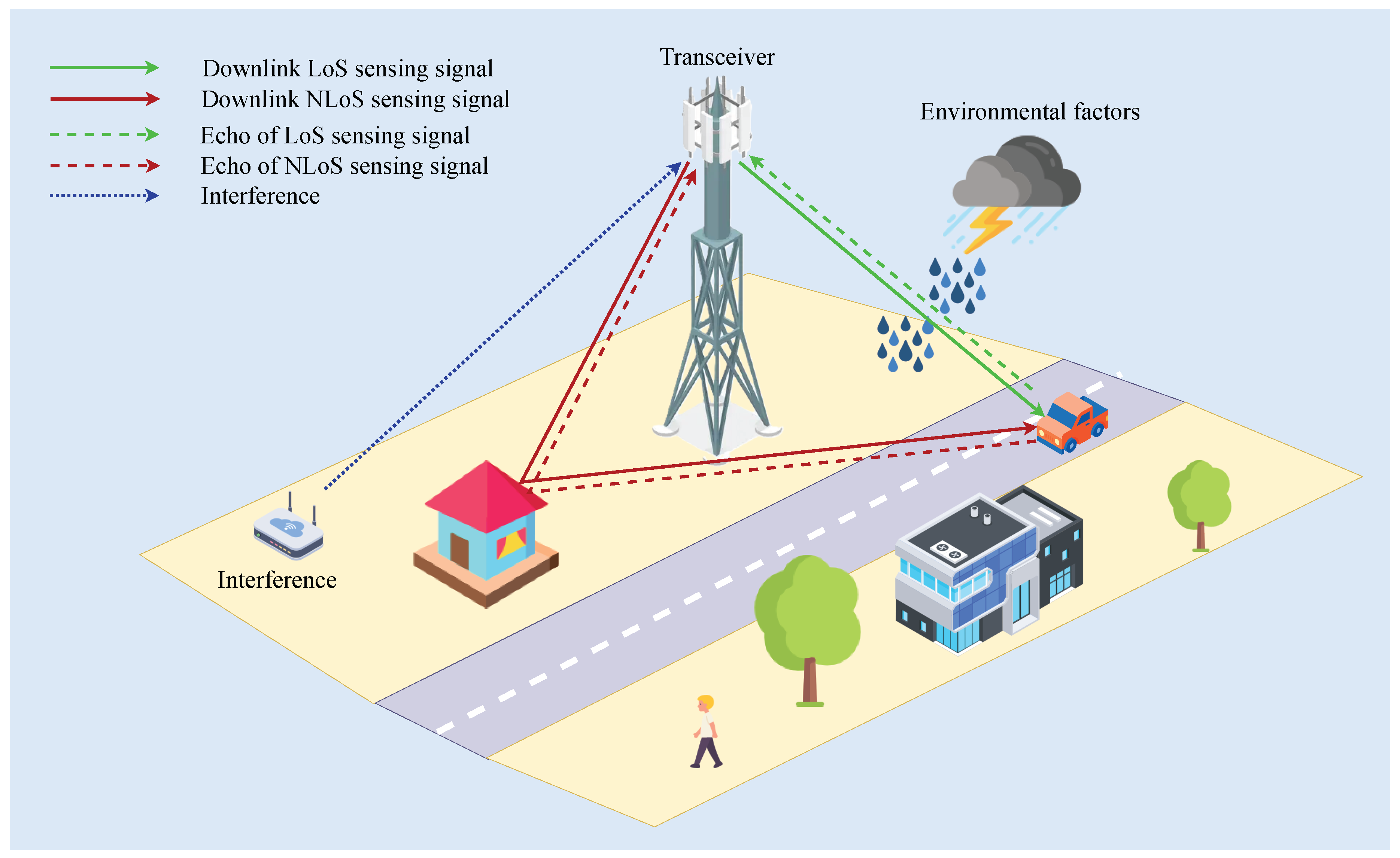

2.1. Challenges of RF Sensing in Outdoor Environments

2.2. Wireless Technologies for Outdoor Environments

3. The Role of Deep Learning in RF Sensing

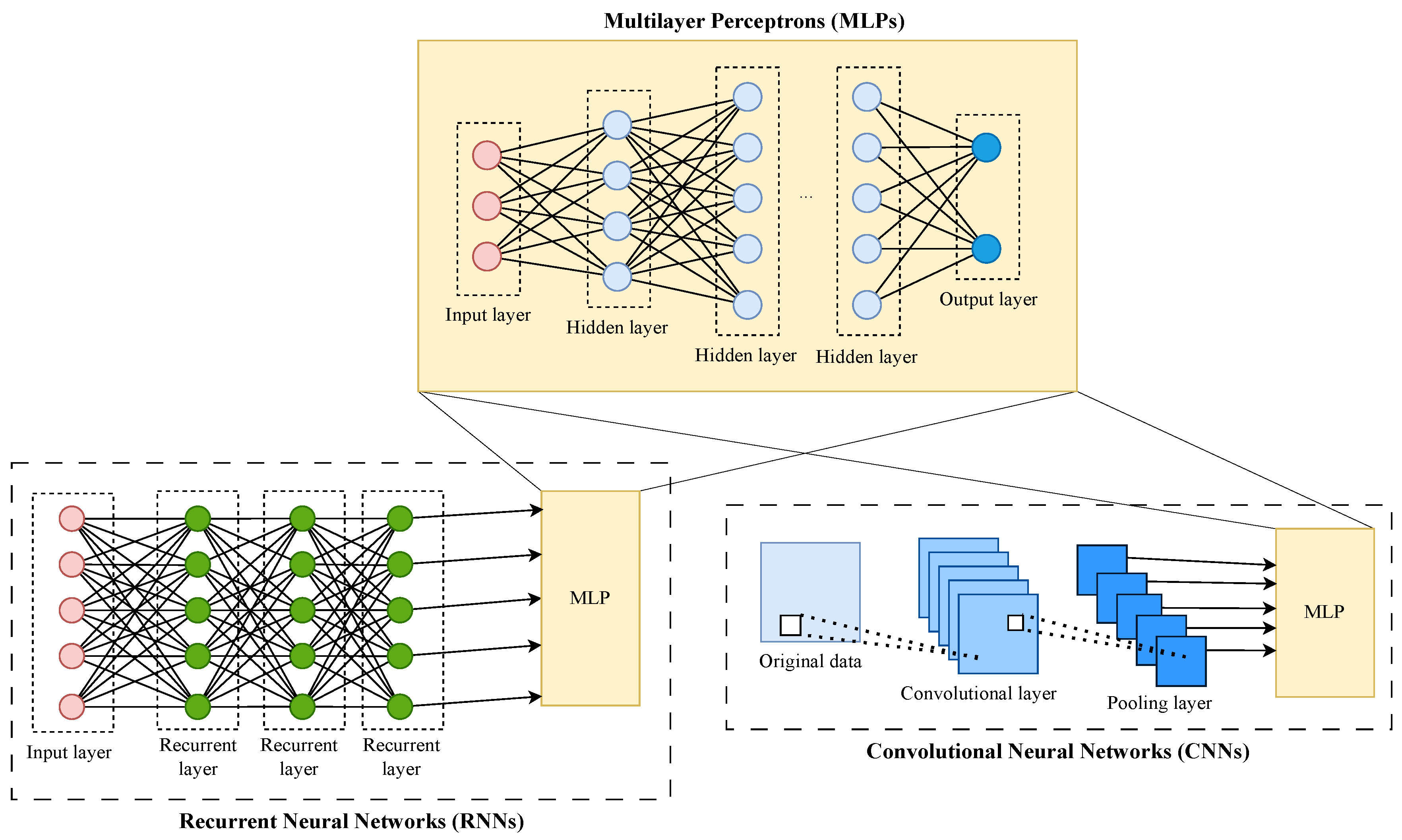

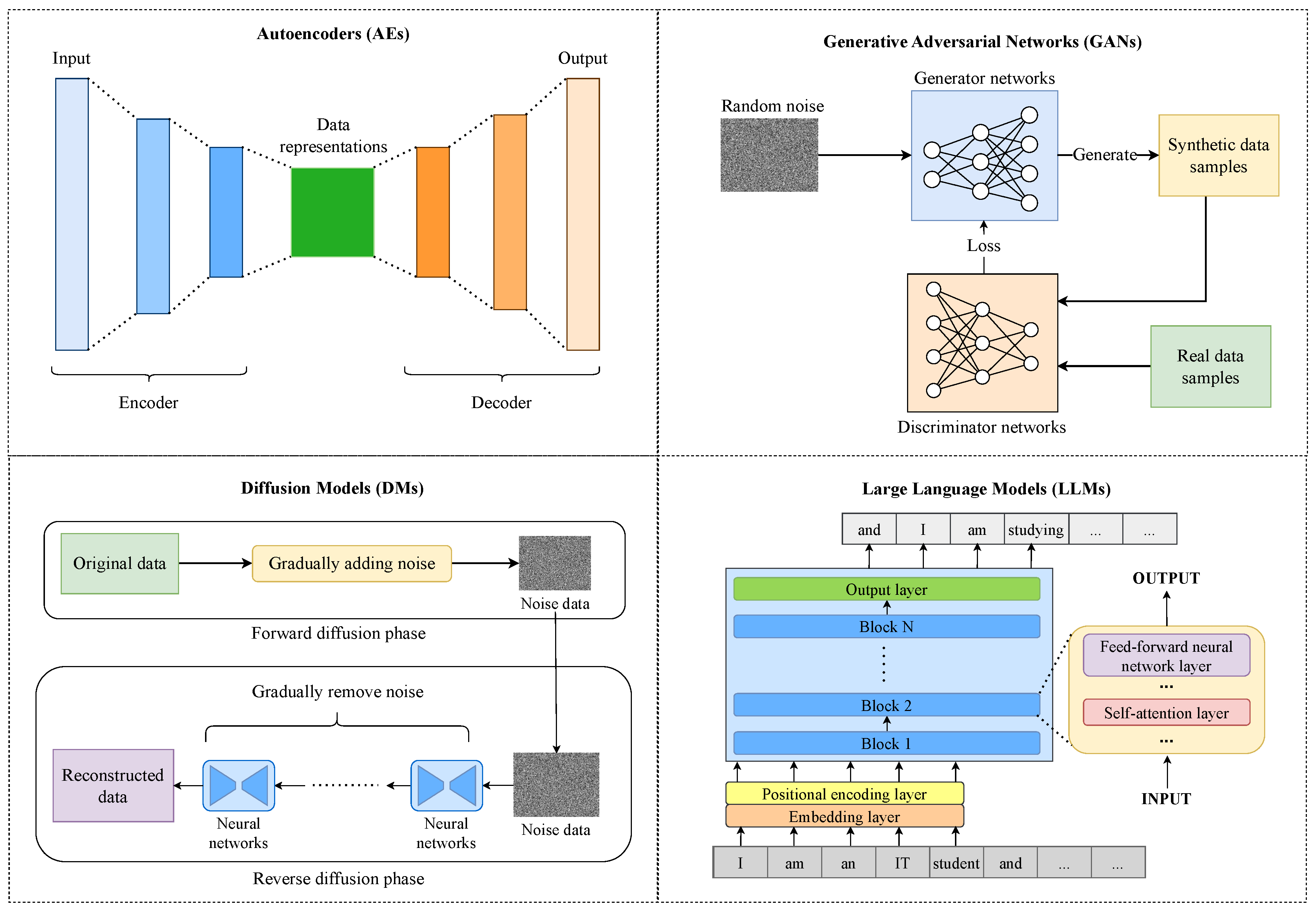

3.1. Deep Learning Models in RF Sensing

3.2. Deep Learning-Empowered Outdoor RF Sensing

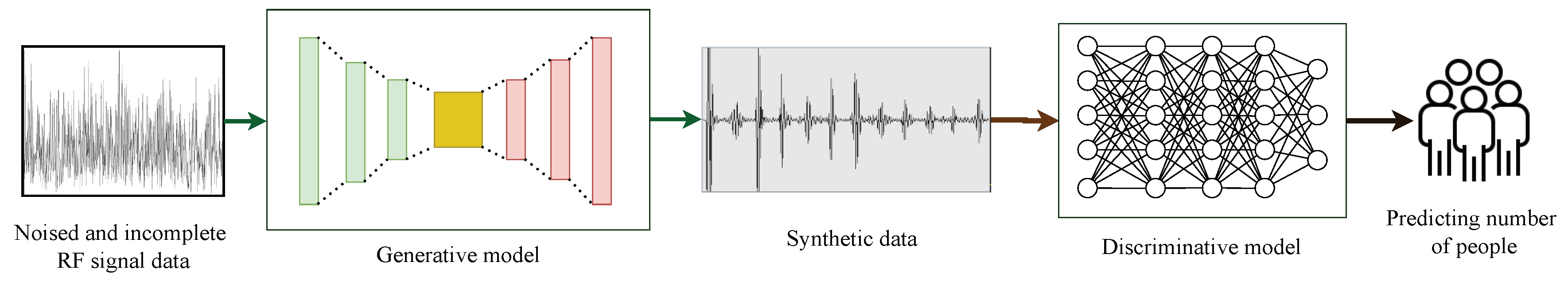

3.2.1. Generative Models

3.2.2. Discriminative Models

3.2.3. Integrating Discriminative and Generative Models

4. Challenges and Future Directions

4.1. The Scarcity of Training Data

4.2. The Gap Between Synthetic and Real-World Data

4.3. The Data Preprocessing Effort

4.4. Multimodal RF Sensing

4.5. Integrated Sensing and Communication (ISAC)

4.6. Federated Learning

5. Conclusion

References

- Zhang, J.; Xi, R.; He, Y.; Sun, Y.; Guo, X.; Wang, W.; Na, X.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Gu, T. A Survey of mmWave-Based Human Sensing: Technology, Platforms and Applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 2052–2087. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zheng, T.; Luo, J. Octopus: A Practical and Versatile Wideband MIMO Sensing Platform. 27th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking (MobiCom ’21); , 2021; pp. 601–614. [CrossRef]

- Lubna, L.; Hameed, H.; Ansari, S.; Zahid, A.; Sharif, A.; Abbas, H.T.; Alqahtani, F.; Mufti, N.; Ullah, S.; Imran, M.A.; Abbasi, Q.H. Radio frequency sensing and its innovative applications in diverse sectors: A comprehensive study. Front. Commun. Netw. 2022, 3. [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Huang, C.; Yu, J.; Shen, X. A Survey of mmWave Radar-Based Sensing in Autonomous Vehicles, Smart Homes and Industry. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024. Early Access, . [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Chakma, A.; Rahman, M.H.; Bin Mofidul, R.; Alam, M.M.; Utama, I.B.K.Y.; Jang, Y.M. RF-Enabled Deep-Learning-Assisted Drone Detection and Identification: An End-to-End Approach. Sensors 2023, 23, 4202. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Ullah, A.; Choi, W. WiFi-Based Human Sensing With Deep Learning: Recent Advances, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2024, 5, 3595–3623. [CrossRef]

- Jagannath, A.; Jagannath, J.; Kumar, P.S.P.V. A comprehensive survey on radio frequency (RF) fingerprinting: Traditional approaches, deep learning, and open challenges. Comput. Netw. 2022, 219, 109455. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Cui, Y.; Masouros, C.; Xu, J.; Han, T.X.; Eldar, Y.C.; Buzzi, S. Integrated Sensing and Communications: Toward Dual-Functional Wireless Networks for 6G and Beyond. IEEE J. Select. Areas Commun. 2022, 40, 1728–1767. [CrossRef]

- Van Truong, T.; Nayyar, A.; Masud, M. A novel air quality monitoring and improvement system based on wireless sensor and actuator networks using LoRa communication. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e711. [CrossRef]

- Yapar, C.; Levie, R.; Kutyniok, G.; Caire, G. Real-Time Outdoor Localization Using Radio Maps: A Deep Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2023, 22, 9703–9717. [CrossRef]

- Yi Lim, N.C.; Yong, L.; Su, H.T.; Yu Hao Chai, A.; Vithanawasam, C.K.; Then, Y.L.; Siang Tay, F. Review of Temperature and Humidity Impacts on RF Signals. 13th International UNIMAS Engineering Conference (EnCon 2020); , 2020; pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Haenggi, M.; Ganti, R.K.; others. Interference in large wireless networks. Found. Trends Netw. 2009, 3, 127–248. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Chen, Z.; Ding, S.; Luo, J. Enhancing RF Sensing with Deep Learning: A Layered Approach. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2021, 59, 70–76. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Mao, S. RF Sensing in the Internet of Things: A General Deep Learning Framework. IEEE Commun. Mag., 56, 62–67. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Pourpanah, F. Recent advances in deep learning. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2020, 11, 747–750.

- Bayoudh, K.; Knani, R.; Hamdaoui, F.; Mtibaa, A. A survey on deep multimodal learning for computer vision: advances, trends, applications, and datasets. Vis. Comput. 2022, 38, 2939–2970.

- Ni, J.; Young, T.; Pandelea, V.; Xue, F.; Cambria, E. Recent advances in deep learning based dialogue systems: A systematic survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 3055–3155.

- Iman, M.; Arabnia, H.R.; Rasheed, K. A review of deep transfer learning and recent advancements. Technol. 2023, 11, 40.

- Choudhary, K.; DeCost, B.; Chen, C.; Jain, A.; Tavazza, F.; Cohn, R.; Park, C.W.; Choudhary, A.; Agrawal, A.; Billinge, S.J.; others. Recent advances and applications of deep learning methods in materials science. npj Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 59.

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444.

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016.

- Elbir, A.M. DeepMUSIC: Multiple signal classification via deep learning. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2020, 4, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Conn, M.A.; Josyula, D. Radio Frequency Classification and Anomaly Detection Using Convolutional Neural Networks. 2019 IEEE Radar Conference (RadarConf); , 2019; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Regmi, H.; Sur, S. CoSense: Deep Learning Augmented Sensing for Coexistence with Networking in Millimeter-Wave Picocells. ACM Trans. Internet Things 2024, 5, 17:1–17:35. [CrossRef]

- Chi, G.; Yang, Z.; Wu, C.; Xu, J.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Han, T.X. RF-Diffusion: Radio Signal Generation via Time-Frequency Diffusion. 30th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking (MobiCom ’24); , 2024; pp. 77–92. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Yuan, W.; Ng, D.W.K. Deep CLSTM for Predictive Beamforming in Integrated Sensing and Communication-Enabled Vehicular Networks. Journal of Communications and Information Networks 2022, 7, 269–277.

- Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Wei, Z.; Ng, D.W.K.; Schober, R. Scalable Predictive Beamforming for IRS-Assisted Multi-User Communications: A Deep Learning Approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.12644 2022.

- Nirmal, I.; Khamis, A.; Hassan, M.; Hu, W.; Zhu, X. Deep Learning for Radio-Based Human Sensing: Recent Advances and Future Directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2021, 23, 995–1019. [CrossRef]

- Burghal, D.; Ravi, A.T.; Rao, V.; Alghafis, A.A.; Molisch, A.F. A Comprehensive Survey of Machine Learning Based Localization with Wireless Signals. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.11171 2020. [CrossRef]

- Amjad, B.; Ahmed, Q.Z.; Lazaridis, P.I.; Hafeez, M.; Khan, F.A.; Zaharis, Z.D. Radio SLAM: A Review on Radio-Based Simultaneous Localization and Mapping. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 9260–9278. [CrossRef]

- Soumya, A.; Krishna Mohan, C.; Cenkeramaddi, L.R. Recent Advances in mmWave-Radar-Based Sensing, Its Applications, and Machine Learning Techniques: A Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 8901. [CrossRef]

- Zafari, F.; Gkelias, A.; Leung, K.K. A Survey of Indoor Localization Systems and Technologies. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2568–2599. [CrossRef]

- Yassin, A.; Nasser, Y.; Awad, M.; Al-Dubai, A.; Liu, R.; Yuen, C.; Raulefs, R.; Aboutanios, E. Recent Advances in Indoor Localization: A Survey on Theoretical Approaches and Applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2017, 19, 1327–1346. [CrossRef]

- Dogan, D.; Dalveren, Y.; Kara, A. A Mini-Review on Radio Frequency Fingerprinting Localization in Outdoor Environments: Recent Advances and Challenges. 14th International Conference on Communications (COMM); , 2022; pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Budalal, A.A.; Islam, M.R. Path loss models for outdoor environment—with a focus on rain attenuation impact on short-range millimeter-wave links. e-Prime - Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2023, 3, 100106. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Mu, X.; Hou, T.; Xu, J.; Di Renzo, M.; Al-Dhahir, N. Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces: Principles and Opportunities. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 1546–1577. [CrossRef]

- Trichopoulos, G.C.; Theofanopoulos, P.; Kashyap, B.; Shekhawat, A.; Modi, A.; Osman, T.; Kumar, S.; Sengar, A.; Chang, A.; Alkhateeb, A. Design and Evaluation of Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces in Real-World Environment. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2022, 3, 462–474. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Di, B.; Li, L.; Bian, K.; Song, L.; Li, Y.; Han, Z.; Poor, H.V. Reconfigurable Intelligent Surface Based RF Sensing: Design, Optimization, and Implementation. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2020, 38, 2700–2716. [CrossRef]

- Alexandropoulos, G.C.; Crozzoli, M.; Phan-Huy, D.T.; Katsanos, K.D.; Wymeersch, H.; Popovski, P.; Ratajczak, P.; Bénédic, Y.; Hamon, M.H.; Gonzalez, S.H.; D’Errico, R.; Strinati, E.C. Smart Wireless Environments Enabled by RISs: Deployment Scenarios and Two Key Challenges. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.13478 2022. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wen, C.; Li, J.; Xia, X.G.; Hong, W. An Efficient Radio Frequency Interference Mitigation Algorithm in Real Synthetic Aperture Radar Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Ameloot, T.; Van Torre, P.; Rogier, H. Variable Link Performance Due to Weather Effects in a Long-Range, Low-Power LoRa Sensor Network. Sensors 2021, 21. [CrossRef]

- Hau, F.; Baumgärtner, F.; Vossiek, M. The Degradation of Automotive Radar Sensor Signals Caused by Vehicle Vibrations and Other Nonlinear Movements. Sensors 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Iannizzotto, G.; Milici, M.; Nucita, A.; Lo Bello, L. A Perspective on Passive Human Sensing with Bluetooth. Sensors 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, M.; Zen, K. Performance Evaluation of ZigBee in Indoor and Outdoor Environment. 9th International Conference on IT in Asia (CITA); , 2015; pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Semtech Semiconductor, IoT Systems and Cloud Connectivity | Semtech.

- Augustin, A.; Yi, J.; Clausen, T.; Townsley, W.M. A Study of LoRa: Long Range I& Low Power Networks for the Internet of Things. Sensors 2016, 16, 1466. [CrossRef]

- Chu, N.H.; Nguyen, D.N.; Hoang, D.T.; Pham, Q.V.; Phan, K.T.; Hwang, W.J.; Dutkiewicz, E. AI-Enabled mm-Waveform Configuration for Autonomous Vehicles With Integrated Communication and Sensing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 16727–16743. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, X.; Das, D.; Akhmetov, D.; Cordeiro, C. Overview and Performance Evaluation of Wi-Fi 7. IEEE Commun. Stand. Mag. 2022, 6, 12–18. [CrossRef]

- Ahson, S.A.; Ilyas, M. RFID Handbook: Applications, Technology, Security, and Privacy; CRC press: Boca, FL, USA, 2017. ISBN 978-1-4200-5499-6.

- Barbieri, L.; Brambilla, M.; Trabattoni, A.; Mervic, S.; Nicoli, M. UWB Localization in a Smart Factory: Augmentation Methods and Experimental Assessment. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Hillger, P.; Grzyb, J.; Jain, R.; Pfeiffer, U.R. Terahertz Imaging and Sensing Applications With Silicon-Based Technologies. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chi, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhu, T. Passive-ZigBee: Enabling ZigBee Communication in IoT Networks with 1000X+ Less Power Consumption. 16th ACM Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems (SenSys ’18); , 2018; pp. 159–171. [CrossRef]

- Demeslay, C.; Rostaing, P.; Gautier, R. Theoretical Performance of LoRa System in Multipath and Interference Channels. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 6830–6843. [CrossRef]

- Haxhibeqiri, J.; Van den Abeele, F.; Moerman, I.; Hoebeke, J. LoRa Scalability: A Simulation Model Based on Interference Measurements. Sensors 2017, 17, 1193. [CrossRef]

- Nie, M.; Zou, L.; Cui, H.; Zhou, X.; Wan, Y. Enhancing Human Activity Recognition with LoRa Wireless RF Signal Preprocessing and Deep Learning. Electron. 2024, 13, 264. [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.Z.; Murray, D.; Diepeveen, D.; Jones, M.G.K.; Sohel, F. LoRa-based outdoor localization and tracking using unsupervised symbolization. Internet Things 2024, 25, 101016. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Liebeherr, J. A Low-Cost Low-Power LoRa Mesh Network for Large-Scale Environmental Sensing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 16700–16714. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Yan, H.; Dang, X.; Ma, Z.; Jin, P.; Ke, W. Millimeter-Wave Radar Localization Using Indoor Multipath Effect. Sensors 2022, 22, 5671. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, G.; Liu, Z.; Conti, A.; Park, H.; Win, M.Z. Integrated Localization and Communication for Efficient Millimeter Wave Networks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2023, 41, 3925–3941. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xie, Y.; Ganesan, D.; Xiong, J. LTE-based Pervasive Sensing Across Indoor and Outdoor. 19th ACM Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems; , 2021; SenSys ’21, p. 138–151. [CrossRef]

- Sardar, S.; Mishra, A.K.; Khan, M.Z.A. Vehicle detection and classification using LTE-CommSense. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2019, 13, 850–857. [CrossRef]

- Sonny, A.; Rai, P.K.; Kumar, A.; Khan, M.Z.A. Deep learning-based smart parking solution using channel state information in LTE-based cellular networks. International Conference on COMmunication Systems & NETworkS (COMSNETS); , 2020; pp. 642–645. [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, A.; Abdullah, F.Y. Long term evolution (LTE) scheduling algorithms in wireless sensor networks (WSN). Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2015, 121. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Chen, J.; He, K.; Wu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Du, R. WiFiLeaks: Exposing Stationary Human Presence Through a Wall With Commodity Mobile Devices. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 6997–7011. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhou, G.; Wang, S. WiFi Sensing with Channel State Information. ACM Comput. Surv. 2019, 52, 1–36. [CrossRef]

- Landaluce, H.; Arjona, L.; Perallos, A.; Falcone, F.; Angulo, I.; Muralter, F. A Review of IoT Sensing Applications and Challenges Using RFID and Wireless Sensor Networks. Sensors 2020, 20, 2495. [CrossRef]

- Shen, E.; Yang, W.; Wang, X.; Kang, B.; Mao, S. TagSense: Robust Wheat Moisture and Temperature Sensing Using RFID. IEEE J. Radio Freq. Identif. 2024, 8, 76–87. [CrossRef]

- Le Breton, M.; Baillet, L.; Larose, E.; Rey, E.; Benech, P.; Jongmans, D.; Guyoton, F. Outdoor UHF RFID: Phase Stabilization for Real-world Applications. IEEE J. Radio Freq. Identif. 2017, 1, 279–290. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, L.T.; Chen, M.; Zhao, S.; Guo, M.; Zhang, Y. Real-time locating systems using active RFID for Internet of Things. IEEE Syst. J. 2014, 10, 1226–1235. [CrossRef]

- Florentin, I. Discussion on UWB Technology and Its Applicability in Different Fields. J. Mil. Technol. 2020, 4. [CrossRef]

- Queralta, J.P.; Martínez Almansa, C.; Schiano, F.; Floreano, D.; Westerlund, T. UWB-based System for UAV Localization in GNSS-Denied Environments: Characterization and Dataset. 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); , 2020; pp. 4521–4528. [CrossRef]

- Gabela, J.; Retscher, G.; Goel, S.; Perakis, H.; Masiero, A.; Toth, C.; Gikas, V.; Kealy, A.; Koppányi, Z.; Błaszczak-Bąk, W.; others. Experimental Evaluation of a UWB-Based Cooperative Positioning System for Pedestrians in GNSS-Denied Environment. Sensors 2019, 19, 5274. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Dong, B.; Wang, J. VULoc: Accurate UWB Localization for Countless Targets without Synchronization. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2022, 6. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, P. Terahertz technology. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2002, 50, 910–928. [CrossRef]

- Bogue, R. Sensing with terahertz radiation: a review of recent progress. Sens. Rev. 2018, 38, 216–222. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, C.; Wietzke, S.; Peters, O.; Scheller, M.; Vieweg, N.; Salhi, M.; Krumbholz, N.; Jördens, C.; Hochrein, T.; Koch, M. Terahertz imaging: applications and perspectives. Appl. Opt. 2010, 49, E48–E57. [CrossRef]

- Ren, A.; Zahid, A.; Fan, D.; Yang, X.; Imran, M.A.; Alomainy, A.; Abbasi, Q.H. State-of-the-Art in Terahertz Sensing for Food and Water Security – A Comprehensive Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 85, 241–251. [CrossRef]

- Pawar, A.Y.; Sonawane, D.D.; Erande, K.B.; Derle, D.V. Terahertz technology and its applications. Drug Invent. Today 2013, 5, 157–163. [CrossRef]

- Naftaly, M.; Vieweg, N.; Deninger, A. Industrial applications of terahertz sensing: State of play. Sensors 2019, 19, 4203.

- Tomczak, J.M. Why Deep Generative Modeling? In Deep Generative Modeling; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Q.; Zou, H.; Lasaulce, S.; Valenzise, G.; He, Z.; Debbah, M. Generative AI for RF Sensing in IoT Systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.07506 2024.

- Zhou, R.; Tang, M.; Gong, Z.; Hao, M. FreeTrack: Device-free human tracking with deep neural networks and particle filtering. IEEE Syst. J. 2019, 14, 2990–3000.

- Wu, X.; Chu, Z.; Yang, P.; Xiang, C.; Zheng, X.; Huang, W. TW-See: Human activity recognition through the wall with commodity Wi-Fi devices. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2018, 68, 306–319.

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, G.; Tang, C.; Luo, C.; Zeng, W.; Zha, Z.J. A Battle of Network Structures: An Empirical Study of CNN, Transformer, and MLP. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.13002 2021.

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of deep learning: concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 1–74.

- Podder, P.; Zawodniok, M.; Madria, S. Deep Learning for UAV Detection and Classification via Radio Frequency Signal Analysis. 25th IEEE International Conference on Mobile Data Management (MDM); , 2024; pp. 165–174. [CrossRef]

- Shewalkar, A.; Nyavanandi, D.; Ludwig, S.A. Performance evaluation of deep neural networks applied to speech recognition: RNN, LSTM and GRU. J. Artif. Intell. Soft Comput. Res. 2019, 9, 235–245.

- Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Physica D 2020, 404, 132306.

- Wang, S.; Cao, D.; Liu, R.; Jiang, W.; Yao, T.; Lu, C.X. Human Parsing with Joint Learning for Dynamic mmWave Radar Point Cloud. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2023, 7, 34:1–34:22. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, X.; Zou, H.; Lu, C.X.; Wang, D.; Sun, S.; Xie, L. SenseFi: A library and benchmark on deep-learning-empowered WiFi human sensing. Patterns 2023, 4. [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6114 2013.

- Bank, D.; Koenigstein, N.; Giryes, R. Autoencoders. Mach. Learn. Data Sci. Handb. 2023, pp. 353–374.

- Teganya, Y.; Romero, D. Deep Completion Autoencoders for Radio Map Estimation. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2022, 21, 1710–1724. [CrossRef]

- Almazrouei, E.; Gianini, G.; Almoosa, N.; Damiani, E. A Deep Learning Approach to Radio Signal Denoising. 2019 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference Workshops (WCNCW); , 2019; pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 139–144.

- Creswell, A.; White, T.; Dumoulin, V.; Arulkumaran, K.; Sengupta, B.; Bharath, A.A. Generative adversarial networks: An overview. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2018, 35, 53–65.

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, G.; Chen, J.; Cui, S. Fast and Accurate Cooperative Radio Map Estimation Enabled by GAN. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.02729 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 6840–6851.

- Chen, X.; Zhang, X. RF Genesis: Zero-Shot Generalization of mmWave Sensing through Simulation-Based Data Synthesis and Generative Diffusion Models. 21st ACM Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems (SenSys ’23); , 2024; pp. 28–42. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhang, L.; Qian, L.; Yang, X. Diffusion-Based Radio Signal Augmentation for Automatic Modulation Classification. Electron. 2024, 13, 2063. [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training. OpenAI 2018.

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; Rodriguez, A.; Joulin, A.; Grave, E.; Lample, G. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971 2023.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017); , 2017; pp. 5998–6008.

- Liu, G.; Van Huynh, N.; Du, H.; Hoang, D.T.; Niyato, D.; Zhu, K.; Kang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Jamalipour, A.; Kim, D.I. Generative AI for Unmanned Vehicle Swarms: Challenges, Applications and Opportunities. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.18062 2024.

- Chang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Mi, S.; Zhang, Y. Radio frequency fingerprint recognition method based on prior information. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 120, 109684. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wei, Z.; Ng, D.W.K.; Yuan, J.; Liang, Y.C. Deep Transfer Learning for Signal Detection in Ambient Backscatter Communications. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2021, 20, 1624–1638.

- Nguyen, H.N.; Vomvas, M.; Vo-Huu, T.D.; Noubir, G. WRIST: Wideband, Real-Time, Spectro-Temporal RF Identification System Using Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 1550–1567. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Tharwat, M.; Magdy, M.; Abubakr, T.; Nasr, O.; Youssef, M. DeepFeat: Robust Large-Scale Multi-Features Outdoor Localization in LTE Networks Using Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 3400–3414. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Bodanese, E.; Poslad, S.; Chen, P.; Wang, J.; Fan, Y.; Hou, T. A Contactless Health Monitoring System for Vital Signs Monitoring, Human Activity Recognition, and Tracking. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 29275–29286. [CrossRef]

- Levie, R.; Yapar, C.; Kutyniok, G.; Caire, G. RadioUNet: Fast Radio Map Estimation With Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2021, 20, 4001–4015. [CrossRef]

- Bahl, P.; Padmanabhan, V.N. RADAR: An In-Building RF-Based User Location and Tracking System. 19th Annual Joint Conference of the IEEE Computer and Communications Societies (INFOCOM 2000); , 2000; pp. 775–784. [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Kim, J. AdaptiveK-nearest neighbour algorithm for WiFi fingerprint positioning. ICT Express 2018, 4, 91–94. [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); , 2016; pp. 779–788.

- Yao, Y.; Lv, K.; Huang, S.; Li, X.; Xiang, W. UAV trajectory and energy efficiency optimization in RIS-assisted multi-user air-to-ground communications networks. Drones 2023, 7, 272.

- Lukito, W.D.; Xiang, W.; Lai, P.; Cheng, P.; Liu, C.; Yu, K.; Zhu, X. Integrated STAR-RIS and UAV for Satellite IoT Communications: An Energy-Efficient Approach. IEEE Internet of Things J. 2024. Early Access, . [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Zhang, R.; Dobre, O.A. Radio-Frequency Identification for Drones With Nonstandard Waveforms Using Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Lou, L.; Chen, X.; Zhao, X.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, S.; He, W. Wi-LADL: A Wireless-Based Lightweight Attention Deep Learning Method for Human–Vehicle Recognition. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 2803–2814. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, P.; Yan, X.; Wu, H.C.; He, L. Radio Frequency-Based UAV Sensing Using Novel Hybrid Lightweight Learning Network. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 4841–4850. [CrossRef]

- Bremnes, K.; Moen, R.; Yeduri, S.R.; Yakkati, R.R.; Cenkeramaddi, L.R. Classification of UAVs utilizing fixed boundary empirical wavelet sub-bands of RF fingerprints and deep convolutional neural network. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 21248–21256.

- Dai, S.; Jiang, S.; Yang, Y.; Cao, T.; Li, M.; Banerjee, S.; Qiu, L. Advancing Multi-Modal Sensing Through Expandable Modality Alignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.17777 2024.

- Zhao, L.; Lyu, R.; Lei, H.; Lin, Q.; Zhou, A.; Ma, H.; Wang, J.; Meng, X.; Shao, C.; Tang, Y.; Chi, G.; Yang, Z. AirECG: Contactless Electrocardiogram for Cardiac Disease Monitoring via mmWave Sensing and Cross-domain Diffusion Model. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2024, 8, 144:1–144:27. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); , 2022; pp. 11976–11986. [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; Uszkoreit, J.; Houlsby, N. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. 9th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); , 2021.

- Lee, W.; Park, J. LLM-Empowered Resource Allocation in Wireless Communications Systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.02944 2024.

- Khachatrian, H.; Mkrtchyan, R.; Raptis, T.P. Outdoor Environment Reconstruction with Deep Learning on Radio Propagation Paths. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.17336 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zheng, L.; Xia, D.; Sun, D.; Liu, W. STL-Detector: Detecting City-Wide Ride-Sharing Cars via Self-Taught Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 2346–2360. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Wu, Z.; Yu, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Hu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Chen, Y. SBRF: A Fine-Grained Radar Signal Generator for Human Sensing. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, pp. 1–17. Early Access, . [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Liu, X.; Li, Z. Radio Anomaly Detection Based on Improved Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2023, 27, 1979–1983. [CrossRef]

- Menghani, G. Efficient deep learning: A survey on making deep learning models smaller, faster, and better. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–37.

- Liu, C.; Yuan, W.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Ng, D.W.K.; Li, Y. Learning-based Predictive Beamforming for Integrated Sensing and Communication in Vehicular Networks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2022, 40, 2317–2334.

- Demirhan, U.; Alkhateeb, A. Integrated Sensing and Communication for 6G: Ten Key Machine Learning Roles. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2023, 61, 113–119. [CrossRef]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Aguera y Arcas, B. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS); , 2017; pp. 1273–1282.

- Nguyen, D.C.; Ding, M.; Pathirana, P.N.; Seneviratne, A.; Li, J.; Vincent Poor, H. Federated Learning for Internet of Things: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 1622–1658. [CrossRef]

| Name | Sensing Range | Transmission Power | Operating Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| LoRa [45,46] | Up to 15 km | Up to 20 dBm | 433 MHz, 868 MHz, 915 MHz |

| mmWave [4,47] | Up to 500 m | 30–40 dBm | 30–300 GHz |

| LTE | Up to 100 m | 23–43 dBm | 450 MHz–3.8 GHz |

| Wi-Fi [48] | Up to 100 m | Up to 30 dBm | 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, 6 GHz |

| RFID [49] | Up to 10 cm | N/A | 125–134 kHz (Low Frequency) |

| Up to 1 m | N/A | 13.56 MHz (High Frequency) | |

| Up to 10 m | N/A | 860–960 MHz (Ultra-High Frequency) | |

| UWB [50] | Up to 200 m | –41.3 dBm | 3.1–10.6 GHz |

| Terahertz [51] | Up to 10 m | N/A | 0.3-3 THz |

| ZigBee [52] | Up to 100 m | Up to 20 dBm | 2.4 GHz |

| Bluetooth [43] | Up to 100 m | 0–20 dBm | 2.4 GHz |

| Type of approach | Model | Objectives | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discriminative | MLPs | Classification, regression | Simple architecture, easy to implement, efficient for small datasets |

Limited capacity for spatial/ temporal information, not scalable for complex tasks |

| CNNs | Signal representation, feature extraction |

Good at extracting spatial features |

Limited for temporal information without additional structures |

|

| RNNs | Sequential signal analysis, time-series prediction |

Handles sequential and temporal dependencies well |

Prone to vanishing/ exploding gradient problems, less efficient for long sequences |

|

| Generative | AEs | Dimensionality reduction, anomaly detection |

Good for feature extraction, data compression |

Poor reconstruction with complex signals, requires tuning of latent space size |

| GANs | RF signal generation, data augmentation, anomaly detection |

Capable of generating realistic data |

Difficult to train, sensitive to hyperparameters |

|

| DMs | Signal denoising, enhancement, and generative modeling |

High quality in denoising and generating diverse data, robust training |

Computationally intensive, slow to generate outputs compared to GANs |

|

| LLMs | Cross-modal RF sensing, sequence modeling |

Excellent for capturing long-range dependencies, scalable, adaptable to different tasks (e.g., classification, localization) |

Requires large datasets or well-pre-trained models, computationally expensive |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).