1. Introduction

Wireless sensor networks (WSNs) can be found in many applications; they are employed in environmental monitoring [

1,

2], industrial automation [

3], precision agriculture [

4], and smart-city infrastructures [

5]. The design of wireless sensor networks (WSNs) is inherently challenging, since, depending on the application, these networks must operate under stringent resource constraints, such as limited battery capacity, interference and noise in the radio medium, as well as restricted computational capabilities. These limitations impose often conflicting performance requirements, including coverage, connectivity, latency, throughput, reliability, and network lifespan. As a result, WSN design and operation are inherently multi-objective: improving one metric often degrades another, as repeatedly observed in studies on coverage, energy efficiency, latency, reliability, and network lifetime [

6,

7,

8].

Evolutionary multi-objective optimization (MOO) methods, such as NSGA-II [

9] and NSGA-III [

10], have proven effective for exploring such trade-offs and generating Pareto-optimal or Pareto-stationary configurations [

11,

12,

13]. However, conducting large-scale experimental studies with simulation-in-the-loop optimization remains operationally challenging [

14,

15]. Widely used WSN simulators, including COOJA [

16], Castalia/OMNeT++ [

17], and NS-3 [

18], provide high-fidelity modeling, but typically offer limited support for systematic orchestration of iterative optimization workflows, scalable management of large numbers of parallel simulations, and end-to-end reproducibility with traceable execution artifacts. As a consequence, experimental pipelines are often tightly coupled to ad hoc scripts and environments, hindering reuse, auditability, and fair comparison across optimization methods.

This paper addresses this gap by focusing on the experimentation infrastructure rather than on proposing a new WSN optimization algorithm or conducting exhaustive algorithmic benchmarks. The primary objective of this work is to define and instantiate a reusable, extensible, and reproducible computational environment for distributed simulation-based multi-objective optimization experiments in WSNs. The experimental executions reported here serve solely as proof of feasibility, demonstrating that the proposed architectural model can be instantiated and executed correctly in practice, while comprehensive domain-specific optimization studies are intentionally deferred to future work building upon this platform.

To achieve this, we adopt a two-layer approach. First, we introduce a simulator-agnostic and algorithm-agnostic formal model that specifies the structure of experiments as sequences of generations, the evaluation mapping from candidate configurations to objective values, and the reactive state transitions that coordinate workflow progression. Second, we present a distributed and modular architecture that instantiates this formal model through containerized simulations, event-driven orchestration, and a flexible optimization engine. This separation between formal concepts and architectural realization is deliberate: it preserves the semantics of the experimental workflow while enabling the integration of different simulators, optimization strategies, and evaluation procedures without requiring redesign of the platform.

Section 3 presents the formal model used to represent simulation-based multi-objective optimization experiments as reactive workflows.

Section 4 then describes the concrete architecture that implements this model, relying on parallel containerized simulation workers, a database-centered event mechanism, and an extensible optimization engine capable of supporting multiple strategies and objective models.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

a unified formal model for simulation-based multi-objective optimization experiments in WSNs, including reactive state transitions for workflow coordination;

a distributed and modular architecture that instantiates this model through event-driven orchestration and containerized simulations, enabling scalable parallel evaluation;

a synthetic evaluation backend to support controlled experiments and benchmarking independent of a specific simulator;

an empirical proof of feasibility under increasing degrees of distributed execution, reporting execution time and resource usage to characterize orchestration overhead and scalability;

a reproducible experimentation environment that preserves structured metadata and execution artifacts to support replay, sharing, and extension of multi-objective optimization studies.

By unifying a formal workflow specification with a practical implementation, the proposed environment provides a robust foundation for reproducible, extensible, and large-scale research on WSN optimization and related simulation-based multi-objective problems.

2. Related Work

A substantial body of work has investigated tools and frameworks to support the execution, orchestration, and reproducibility of large-scale computational experiments. In the context of wireless sensor networks (WSNs), early contributions have primarily focused on automating the deployment and execution of extensive simulation campaigns, motivated by the growing complexity and scale of contemporary WSN scenarios. However, we are far from exhausting the possibilities for the development and optimization of such networks.

One representative example is the Maestro framework, proposed by Riliskis and Osipov, which enables the orchestration of large numbers of WSN simulations on cloud infrastructures by providing mechanisms for configuration, deployment, and parallel execution across heterogeneous environments [

19]. By leveraging Infrastructure-as-a-Service platforms, Maestro significantly reduces the manual effort required to manage large-scale simulation studies and facilitates cost–performance benchmarking of cloud resources. However, its main emphasis lies in the automation of execution and resource management, rather than the formal specification of experimental workflows integrating simulations and optimization algorithms.

Beyond domain-specific simulation orchestration, several general-purpose workflow and provenance-oriented systems have been proposed to improve reproducibility and traceability in computational research. SIERRA, for instance, provides a modular and declarative framework that automates the experimental pipeline from parameter specification to execution and post-processing [

20]. Provenance-driven approaches further capture execution histories and data dependencies to support auditing, verification, and re-execution of scientific workflows [

21]. Similarly, the Collective Knowledge (CK) framework promotes collaborative management of experimental artifacts, workflows, and datasets, fostering standardized execution and sharing of results [

22]. Although these systems substantially advance reproducibility at the level of scripts, environments, and stored artifacts, they typically do not formalize the semantics of iterative optimization loops or the state transitions that govern large sets of simulations (generations) in evolutionary systems.

A complementary research direction addresses the automated generation of structurally diverse simulation models. Nam and Kim introduced the WSN-SES/MB framework, which employs System Entity Structure (SES) and Model Base (MB) concepts to formalize the configuration space of WSN simulations and to synthesize executable models from high-level structural descriptions [

23]. This approach effectively reduces the manual effort required to construct and manage large sets of heterogeneous network configurations. However, its scope is primarily limited to model generation and does not explicitly address the orchestration of iterative optimization workflows, large-scale execution management, or systematic experiment provenance across successive generations.

Several studies have also demonstrated the effectiveness of simulation-driven analysis for WSN optimization under fixed or manually enumerated design alternatives. For example, Ferreira et al. [

24,

25] investigate communication optimization strategies in IoT–Fog ecosystems using detailed Contiki-NG/Cooja simulations combined with multi-attribute decision-making techniques. Although such studies underscore the importance of high-fidelity simulation in WSN research, they are generally restricted to discrete sets of predefined scenarios and lack a unified experimentation infrastructure capable of supporting structural configuration generation, iterative multi-objective optimization, and systematic reproducibility across large experimental campaigns.

Table 1 summarizes the conceptual differences between representative frameworks and the approach proposed in this work. The comparison highlights that existing solutions typically address execution automation, workflow management, provenance tracking, or structural model generation in isolation, whereas the present approach integrates event-driven orchestration, formal workflow semantics, scalable execution, and an explicit multi-objective optimization loop within a single experimentation platform.

Although the aforementioned approaches address important aspects of simulation execution, automation, and reproducibility, none of them provides an integrated and easily reproducible solution that simultaneously combines distributed simulation orchestration with multi-objective optimization. Moreover, formal descriptions of the execution semantics and architectural foundations of such systems remain limited. In light of these observations, this work aims to fill this gap by proposing a flexible and extensible experimentation platform for the development and evaluation of WSNs, as well as for the systematic study and implementation of new multi-objective optimization algorithms in this context.

3. Formal Foundations

This section establishes the formal, computational, and executional foundations of the proposed architecture. The objective is to provide a precise mathematical and operational description of the experimental lifecycle, the optimization process, and the distributed simulation workflow, ensuring analyzability, scalability, and full reproducibility of multi-objective WSN experiments.

3.1. Experiment Model

An experiment is formally defined as the tuple

where:

X denotes the configuration space of candidate wireless sensor network (WSN) solutions. Each element represents a complete network configuration and may encode, depending on the problem definition, geometric parameters (e.g., node or relay positions), structural decisions (e.g., connectivity or routing), protocol-level choices (e.g., MAC or duty-cycling schemes), and other controllable design variables;

is the simulation parameter space, encoding topology, node deployment, communication models, MAC protocols, traffic profiles, and environmental assumptions;

is a vector-valued objective function that maps each network configuration to m performance metrics under a given simulation context . The evaluation implicitly embeds the execution of the simulation model and the computation of objective values;

denotes the optimization strategy that governs population evolution, such as evolutionary algorithms, exact solvers, or heuristics. All algorithm-specific design choices and parameterizations, including population size, selection mechanisms, variation operators, and strategy-specific control parameters, are considered intrinsic to and are therefore encapsulated in its definition.

The experiment evolves through a discrete sequence of generations

where each generation

represents a population snapshot at iteration

k.

Each individual is evaluated through simulation under a given set of simulation parameters , producing a vector of objective values .

To ensure traceability and persistence, the experiment state is materialized in the database through the hierarchical entities

which together define a complete and immutable record of the optimization trajectory.

3.2. Distributed Orchestration Model

We now move from the static definition of experiments to the dynamic execution model that governs their evolution.

The execution model is driven by a finite event alphabet

where:

ExperimentCreated initializes the optimization workflow;

GenerationReady triggers the dispatch of distributed simulations;

SimulationCompleted signals the availability of evaluation results.

The architecture follows a reactive, data-driven orchestration model in which system components interact exclusively through persistent state transitions. Let denote the database state at time t, and let represent the atomic event generated by a change in this state.

System components react to these events by applying state transitions over

. Formally, the architecture is modeled as a labeled transition system (LTS)

where

is the set of reachable database states and

is a deterministic state transition function.

The transition function is deterministic and total over admissible events, meaning that for every reachable state and every event applicable to D, there exists a unique successor state . Determinism is defined at the level of persisted state transitions and event ordering, not at the level of wall-clock time, message delivery latency, or container scheduling. Transient failures, retries, and timing variations do not affect the logical execution trace recorded in the database.

This execution semantics can be illustrated by defining a temporal state function

as

This event-sourced execution model yields loose coupling, fault tolerance, and complete replayability, as the entire evolution of an experiment is uniquely determined by the persisted initial state and the ordered event stream.

3.3. Simulation and Evaluation Model

Each individual configuration

is evaluated through a simulation-based evaluation operator

. Rather than separating simulation and post-processing into distinct formal entities, we model evaluation directly as a mapping

where

defines the complete simulation context and

returns a vector of

m performance metrics associated with the configuration

x under the simulation parameters

.

The evaluation operator conceptually embeds the execution of the underlying simulation model together with any required post-processing of raw simulation outputs. Stochastic effects arising from randomized protocol behavior, environmental variability, or measurement noise are captured implicitly within . Such stochasticity is governed by , which may include random seeds, traffic patterns, or other parameters controlling nondeterministic aspects of the simulation.

This abstraction deliberately decouples the evaluation process from the optimization logic. From the perspective of the optimization operator , behaves as a black-box evaluator that maps configurations to objective values, regardless of whether the evaluation is performed via packet-level simulation, analytical performance models, emulation, or controlled synthetic backends. As a result, heterogeneous simulators and evaluation models can be integrated transparently, without requiring modifications to the evolutionary workflow or the event-driven orchestration mechanism.

3.3.0.1. Event-Driven Optimization

The evolutionary operator is not executed continuously, but is triggered exclusively by events in the reactive execution model. In particular, population updates occur only when the system observes a SimulationCompleted event for all individuals in a generation.

Formally, let

be an event and let

be a valid state. The application of the evolutionary operator is conditioned by:

Only under this condition does the transition become enabled. holds when the number of completed Simulation entities associated with a generation equals the population size.

If an error occurs during simulation execution—namely, an internal simulator failure for which retrying would be ineffective—such an event is interpreted as evidence of an inconsistency or inadequacy in the specification of the decision space X or the simulation parameter space . Accordingly, decision rules based on the error severity are applied to determine whether the experimental process should be interrupted for inspection, analysis, and correction of the model specification, or whether the affected individual can be safely discarded. Under a correct and well-defined formulation of X and , the occurrence of such execution errors is not expected.

3.4. Optimization Model

The optimization task follows the standard multi-objective formulation

where each objective function

captures a relevant performance metric of the WSN, such as coverage quality, end-to-end latency, energy consumption, or network throughput. Note that

F is defined by

fixing the

component of the simulator settings.

The optimization process evolves a population of candidate solutions through discrete generations. In its most general form, the population update rule is defined by an evolutionary operator

where:

is the population at generation k;

is the evaluation operator induced by the simulation model;

denotes a generic evolutionary strategy.

To ensure scalability, the evaluation phase is externalized and executed asynchronously across distributed simulation workers:

with simulations performed in parallel and results incorporated into the population update as they become available. Although simulation execution is asynchronous, population updates follow a synchronous generational model, in which selection and variation are applied only after all evaluations of a generation have completed.

Thus, the evolutionary process described above is not an abstract optimization loop, but a consequence of specific event patterns in the underlying labeled transition system.

3.5. Minimal Convergence Conditions

The proposed optimization process does not assume global optimality guarantees. Instead, it relies on standard asymptotic convergence conditions commonly adopted in evolutionary multi-objective optimization.

Let be the sequence of populations generated by . The following conditions are sufficient to ensure weak convergence to a Pareto-stationary set:

(Finite Population) Each generation has fixed and finite cardinality;

(Elitism) Non-dominated solutions are preserved with non-zero probability;

(Ergodic Variation) The variation operators induced by define an ergodic Markov chain over X;

(Consistent Evaluation) The evaluation operator is stationary with respect to , up to bounded stochastic noise.

Under these assumptions, the sequence of populations converges in probability, in an asymptotic sense, to a set of Pareto-stationary solutions. Such assumptions are standard in the theoretical analysis of evolutionary algorithms and evolutionary multi-objective optimization, where convergence guarantees are typically established in a weak or asymptotic sense under elitism, ergodic variation, and stationary evaluation conditions [

26,

27,

28,

29].

These assumptions directly reflect the design choices of the optimization strategies supported by the proposed architecture, such as elitist evolutionary algorithms (e.g., NSGA-III). In practice, convergence is not established through formal proofs but is assessed empirically by observing the stabilization of Pareto fronts and objective value distributions across successive generations.

These conditions apply at the level of population update dynamics and are independent of the underlying event-driven execution model, which affects only scheduling, parallelism, and synchronization.

3.6. Schedule Execution Model

The system is responsible for scheduling and executing simulations under bounded computational resources. Let

C denote the maximum parallelism level. The execution schedule is defined as

subject to resource constraints

The current implementation adopts a simple queue-based scheduling policy in which simulations are dispatched on a first-available basis, without prioritization among individuals, ensuring fairness and predictable execution behavior.

Operationally, the system implements an event-driven control loop:

procedure MasterNodeLoop():

while true:

ev = wait_for_event()

if ev.type == GenerationReady:

sims = load_simulations(ev.generation)

// asynchronous execution

run_in_parallel(sims, max_containers=C)

if ev.type == SimulationCompleted:

update_database(ev.results)

Execution determinism arises from the fact that scheduling decisions depend solely on persisted state and event ordering.

3.7. Reproducibility Model

The architecture enforces strict experimental reproducibility by design:

experiments, generations, and simulations are immutable entities;

container images encapsulate simulator binaries and dependencies;

event streams preserve chronological execution semantics;

logs, configurations, and binary artifacts are persistently stored.

Under the proposed model, an experiment is reproducible by construction. All elements required for its execution and evaluation are explicitly embedded in its formal definition and persistently materialized in the system state. In particular, the experiment specification fully determines the optimization strategy , the evaluation operator , the simulation context , and the complete sequence of state transitions recorded in the database . Together with containerized execution environments, these elements uniquely define the experimental process. As a consequence, given identical container images, database state , and simulation parameters , the execution of can be deterministically replayed or independently verified without requiring any external or implicit assumptions.

In practice, reproducing an experiment requires access to the container images encapsulating the simulators and dependencies, the persisted database state containing experiment metadata and event history, the simulation parameters and random seeds encoded in , and the corresponding versioned source code of the optimization engine and simulation models. It is important to note that the proposed model does not attempt to capture real-time guarantees, probabilistic failures, or adversarial behaviors. Instead, it focuses on structural correctness, determinism, and reproducibility at the level of experimental execution and optimization logic.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. System Architecture

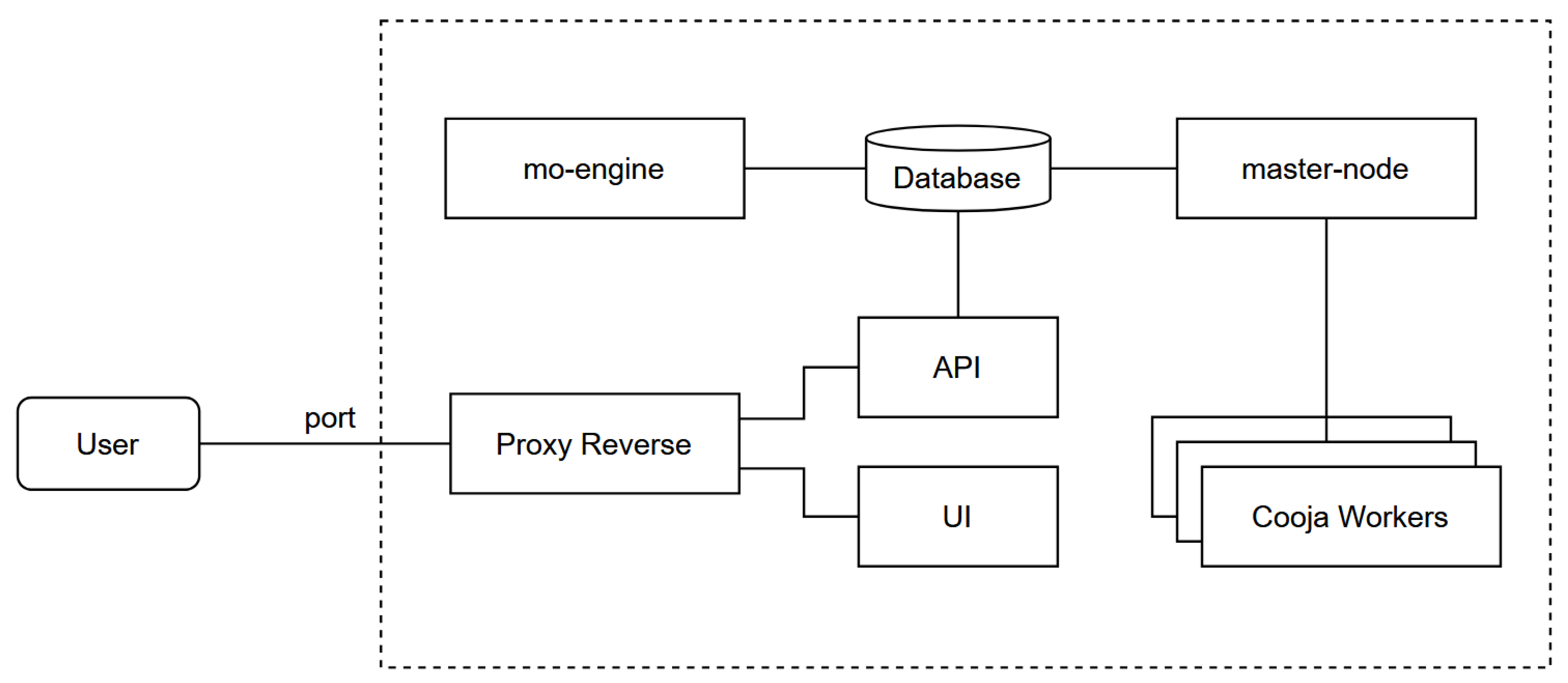

The proposed architecture consists of three core modules: database, mo-engine, and master-node. These components communicate through a central data-management layer that includes a file-storage subsystem for large artifacts. Each module runs as an independent container, and their coordination is orchestrated through reactive, event-driven notifications.

Figure 1.

High-level overview of the proposed architecture, showing the integration of the API, master-node, optimization engine, and data storage.

Figure 1.

High-level overview of the proposed architecture, showing the integration of the API, master-node, optimization engine, and data storage.

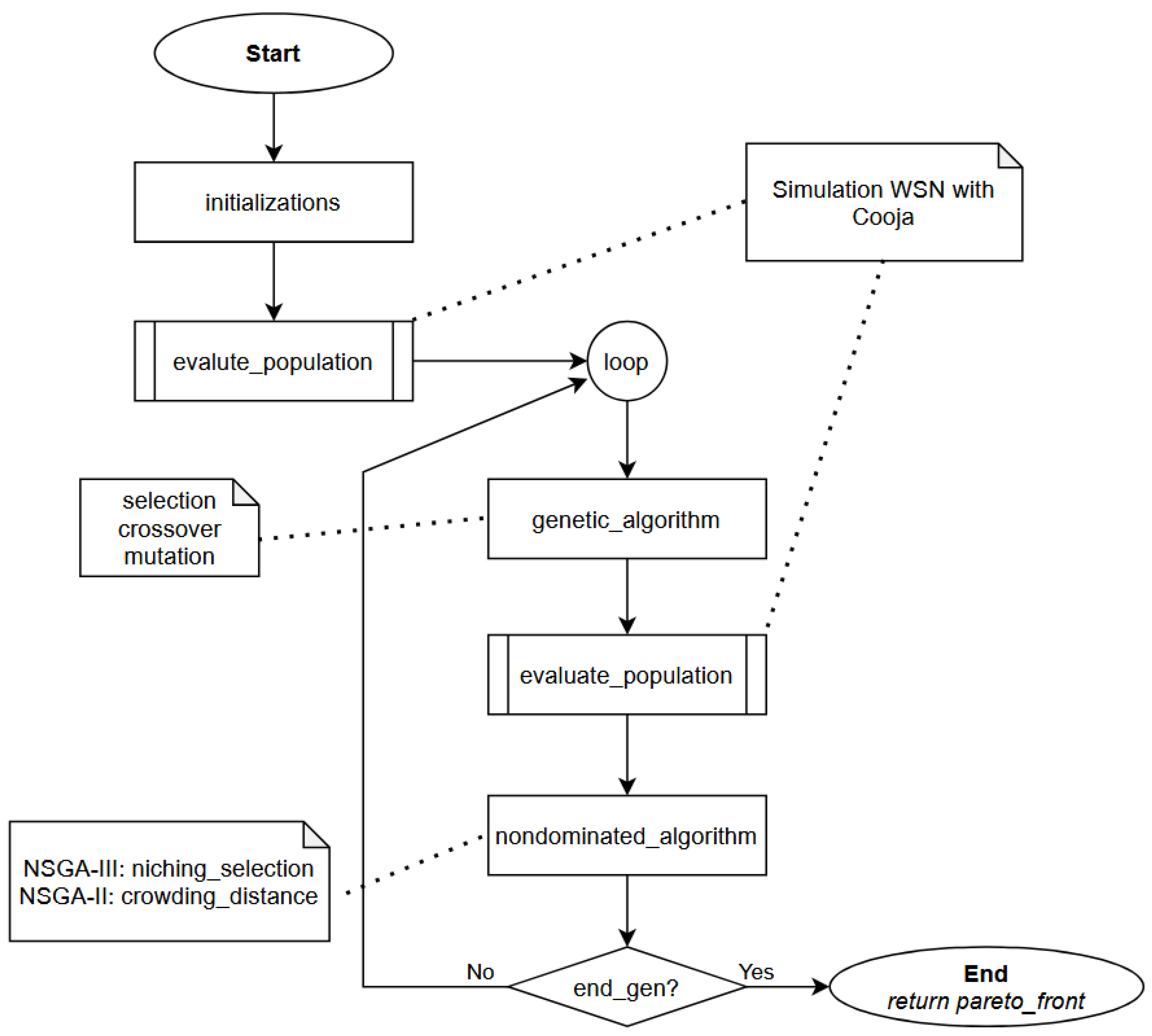

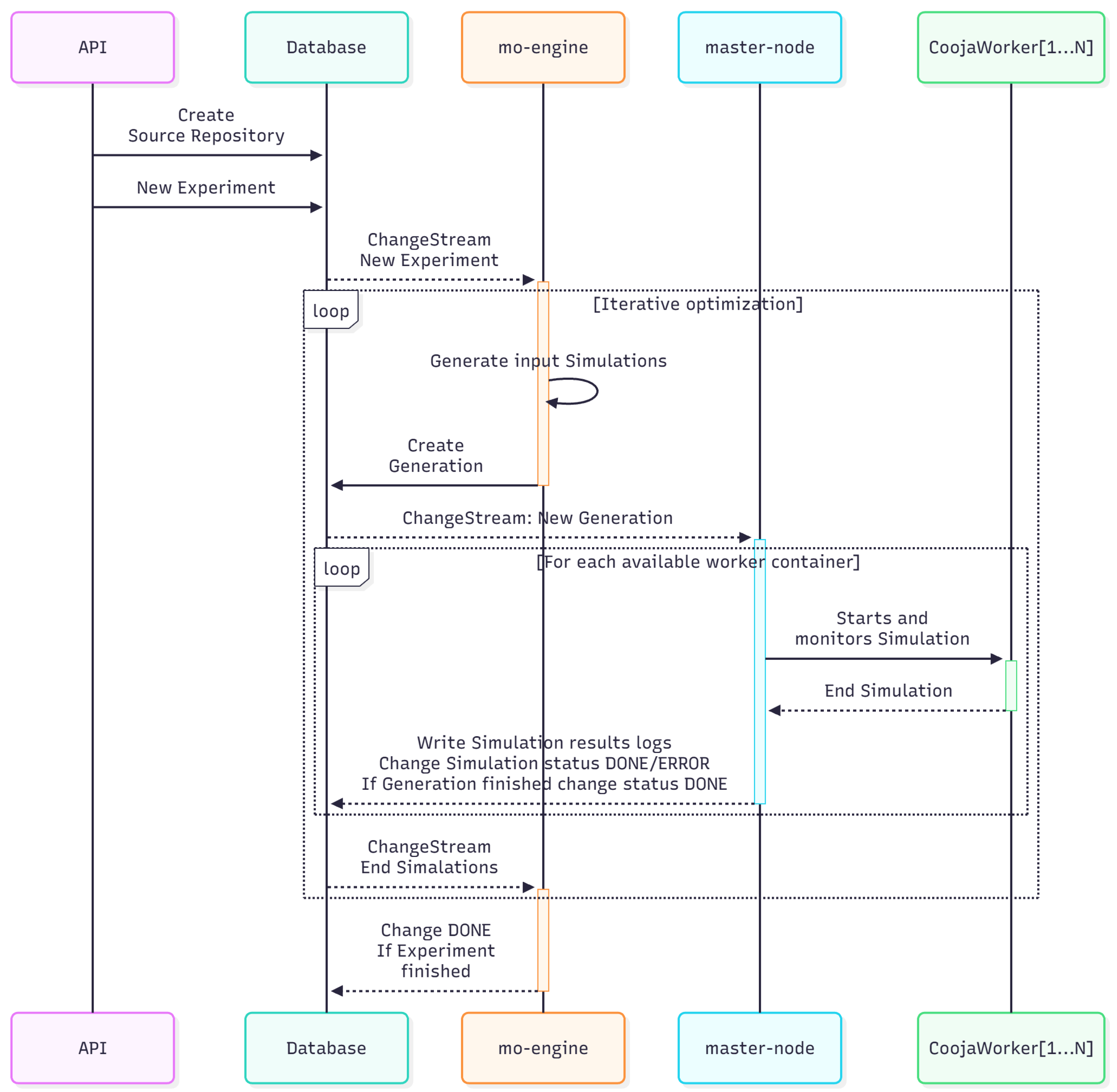

4.2. Workflow

Figure 2 summarizes the general workflow:

An experiment is created via REST API and stored in database.

The mo-engine observes the database for pending experiments and generates simulation queues (generations) according to an optimization strategy (e.g., NSGA-III or Random).

The master-node executes containerized simulations in parallel and collects results.

Results are saved back into database, triggering the next generation of optimization.

4.3. Core Components

Master-Node.

The master-node implements the orchestration logic responsible for managing the life cycle of containerized simulations. It schedules and dispatches simulation tasks, monitors their execution, and coordinates communication with simulation containers through secure channels such as SSH and SCP. In addition, the master-node is responsible for collecting the results and metrics produced by each simulation, storing them in the database, and computing aggregate statistics or derived indicators. These processed results are then made available to the mo-engine, which uses them in subsequent optimization steps, for example to update populations, evaluate convergence, or adapt search strategies.

The use of SSH and SCP reflects the requirement to support the execution of simulations in isolated and potentially remote container environments, where direct filesystem sharing or in-process communication may not be available. This approach provides a simple, widely supported, and secure mechanism for transferring configuration files, execution scripts, and simulation outputs. While SSH-based communication introduces some overhead compared to shared volumes or in-memory message passing, its impact is negligible relative to the execution time of network simulations. Alternative designs based on shared volumes, internal service APIs, or message brokers (e.g., RabbitMQ or Kafka) are feasible and were considered; however, SSH/SCP was selected in the current implementation to maximize portability and minimize infrastructure dependencies.

MO-Engine.

The mo-engine is responsible for generating candidate solutions and producing new generations during the optimization process. It currently supports both random search and evolutionary strategies such as NSGA-III, and its modular design allows new optimization algorithms to be integrated with minimal effort. The engine interacts with the database in a reactive manner, responding to events that indicate when new evaluations are required. The mo-engine exposes a plugin-oriented interface that enables the integration of new optimization algorithms with minimal coupling to the rest of the system. To be integrated, an algorithm implementation must (i) generate candidate configurations in the space X, (ii) define how populations are updated based on evaluated objective values, and (iii) interact with the database by producing Generation and Simulation entities consistent with the experiment schema. This design allows alternative evolutionary methods, heuristics, or exact solvers to be incorporated without modifications to the orchestration or execution layers.

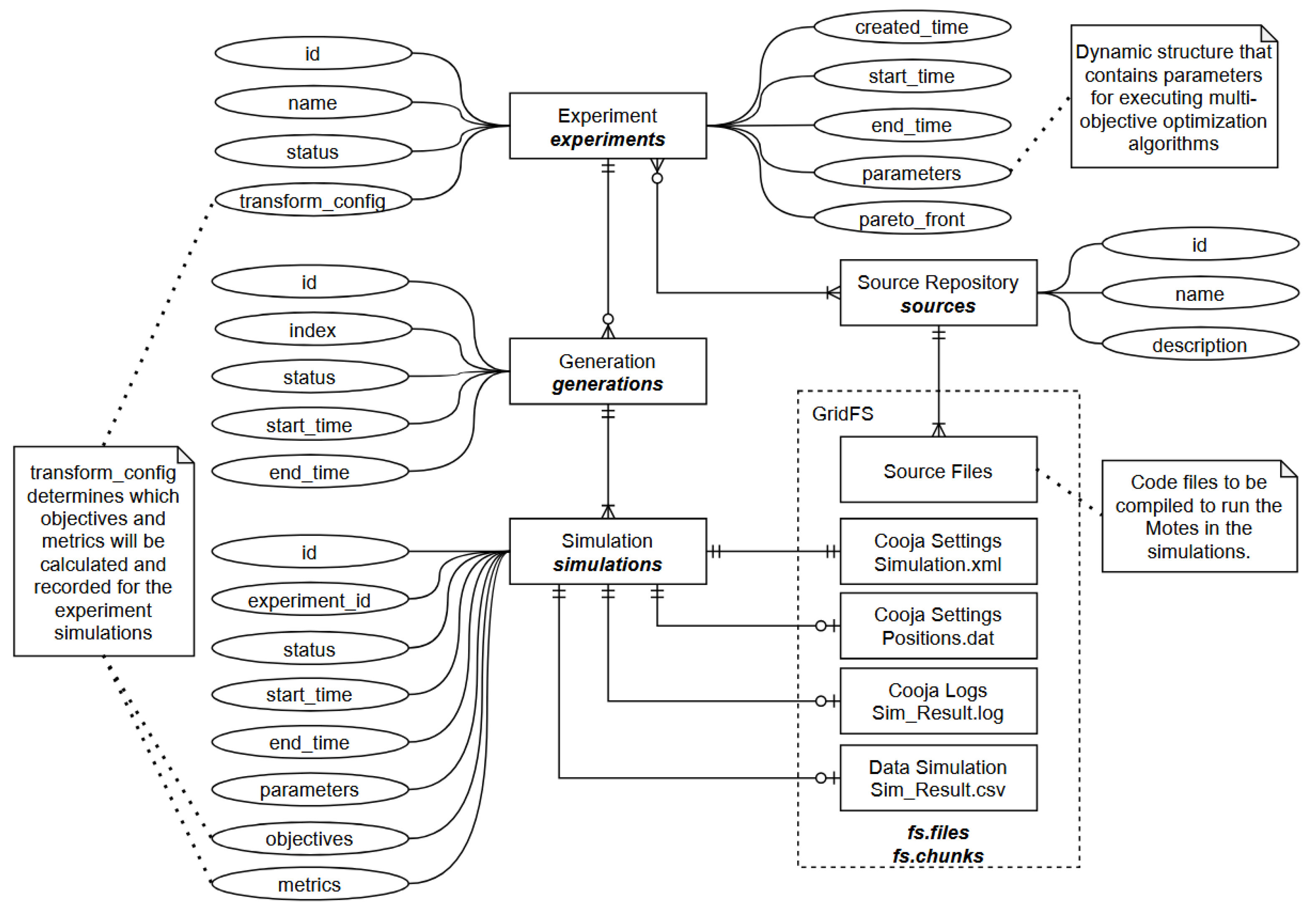

Database.

The database layer maintains all experiment-related information, including metadata associated with Experiment, Generation, and Simulation entities. In addition to structured metadata, the system relies on a distributed file storage mechanism to manage large artifacts such as logs, binary outputs, and simulation configurations. This design ensures reproducibility, traceability, and efficient retrieval of data throughout the lifecycle of an experiment.

MongoDB Change Streams provide a well-defined, real-time mechanism to observe data changes on collections, databases, or full deployments without manually tailing the replication oplog, and rely on the aggregation framework to enable filtering and transformation of change events [

30]. Notably, each change stream event includes a resume token that allows the client to resume listening from a prior point after transient failures, and changes are provided in the order they were applied to the database, with only majority-committed changes delivered to clients [

31].

API.

The system exposes a well-defined REST API that enables users and external services to create, configure, and monitor experiments programmatically. The API is documented through a Swagger-compatible interface available at

http://andromeda.lasdpc.icmc.usp.br:8198/docs, facilitating integration with automated workflows and simplifying the development of client applications.

Graphical User Interface (GUI).

Although the core architecture is designed to operate programmatically through the API, it naturally supports the development of a graphical user interface. A dedicated GUI could offer interactive experiment configuration, real-time visualization of generations and Pareto fronts, monitoring of simulation progress, inspection of logs and artifacts, and streamlined management of optimization strategies and datasets. Such an interface would significantly improve usability and accessibility, enabling researchers and practitioners to interact with the system more intuitively while maintaining the underlying reproducibility guarantees provided by the architecture.

4.4. Experimental Organization

In our initial implementation, the proposed architecture was instantiated using the Cooja network simulator together with a MongoDB-based storage layer. This implementation serves as a concrete realization of the formal model introduced in

Section 3, with experiments, generations, and simulations explicitly materialized as persistent entities in the database.

Figure 3 illustrates the main data structures and their relationships, highlighting how these entities are organized and linked within the system.

All experiments reported in this work were executed on a dedicated server running Ubuntu 24.04.2 LTS (Linux kernel 6.8.0–79), hosted on a virtualized environment with KVM and AMD-V enabled. The system is equipped with an AMD EPYC Milan processor featuring 12 physical cores (12 threads, single-thread per core) operating at approximately 3.8 GHz, and 94 GB of RAM, with negligible memory and swap usage at experiment start. Container management was performed using Docker 27.3.1, with an upper bound of C concurrent simulation containers enforced by the master-node scheduler. Network simulations were executed using the Cooja simulator bundled with Contiki-NG, deployed within containerized environments to ensure isolation and reproducibility. The data-management layer relied on MongoDB 8.2.1, accessed via Mongosh 2.5.8. These hardware and software characteristics directly influence execution time, resource contention, and achievable parallelism, and must therefore be taken into account when interpreting scalability and performance results.

Although the relationships defined in this structure are fixed and governed by the formal model, the attributes associated with each entity remain flexible, allowing the system to be incrementally extended and evolved to accommodate different classes of optimization algorithms, simulation backends, and evaluation models.

5. Prototype Implementation and Proof of Feasibility

This section does not aim to provide an exhaustive experimental evaluation of optimization algorithms or wireless sensor network designs. Instead, it presents a prototype implementation of the proposed architecture and a set of execution examples intended to demonstrate feasibility, modularity, and scalability of the architectural concepts introduced in previous sections. These executions confirm that the formal model and orchestration mechanisms can be realized in practice and serve as a baseline for future experimental studies built on top of this platform.

5.1. Dummy Experiment Example

To ensure modularity and testability, the architecture allows the simulation engine to be disconnected from the Cooja environment and replaced by a dummy module. This module implements an artificial model that synthetically generates simulation data based on parameterized functions representing sensor behaviors, link quality, and energy metrics.

The dummy component emulates the output structure of a real Cooja simulation, returning pseudo-randomized or model-based metrics such as communication success rate, latency, and energy consumption. This capability enables developers to validate algorithms and perform controlled experiments without requiring the full emulation layer.

Additionally, this mode facilitates the calibration and parameter tuning of the mo-engine. By using predictable artificial responses, researchers can verify convergence properties, test evolutionary operators (e.g., crossover and mutation in NSGA-III), and debug data flows before integrating the full network simulation backend.

This modular design ensures that optimization strategies can be validated independently from the simulator, accelerating development and maintaining consistency across experimental pipelines.

5.2. Real Executions and Performance Evaluation

To validate the distributed operation of the architecture under realistic load, several large-scale tests were conducted on the computation host at ICMC–USP. These experiments aimed to assess the system’s performance when running multiple Cooja containers concurrently, while monitoring resource usage and execution time.

Experimental Setup.

The tests used populations of 30 WSN configurations, each with 50 fixed motes. Two scenarios were executed for comparison:

All experiments reported in this work were executed on a dedicated server running Ubuntu 24.04.2 LTS (Linux kernel 6.8.0–79), hosted on a virtualized environment with KVM and AMD-V enabled. The system is equipped with an AMD EPYC Milan processor featuring 12 physical cores (12 threads, single-thread per core) operating at approximately 3.8 GHz, and 94 GB of RAM, with negligible memory and swap usage at experiment start. Container management was performed using Docker 27.3.1, with an upper bound of

C concurrent simulation containers enforced by the master-node scheduler. Network simulations were executed using the Cooja simulator bundled with Contiki-NG, deployed within containerized environments to ensure isolation and reproducibility

1. The data-management layer relied on MongoDB 8.2.1, accessed via Mongosh 2.5.8. These hardware and software characteristics directly influence execution time, resource contention, and achievable parallelism, and must therefore be taken into account when interpreting scalability and performance results.

Metrics were collected via docker stats, including CPU (%), memory usage, network I/O, and block I/O. All modules of the architecture (mo-engine, master-node, database, and rest-api) were monitored.

Execution Time.

The total duration of each scenario was:

Although the 30-container configuration enabled greater parallelism, it did not reduce total execution time due to CPU contention and process scheduling overhead.

Resource Usage.

With 30 containers, the overall memory footprint increased gradually, stabilizing around 2.4 GB per Cooja process. The database and master-node services exhibited higher network throughput, consistent with increased data traffic and synchronization demands. Average resource utilization per component is summarized below.

Table 2.

Average resource metrics during execution with 30 concurrent Cooja containers.

Table 2.

Average resource metrics during execution with 30 concurrent Cooja containers.

| Component |

CPU(%) |

Mem(MiB) |

Mem(%) |

NetRX(B/s) |

NetTX(B/s) |

| Cooja (avg) |

36.97 |

2285.37 |

2.36 |

0.38 |

0.43 |

| Master-node |

9.61 |

51.57 |

0.05 |

603.33 |

321.92 |

| MO-engine |

1.56 |

289.38 |

0.30 |

1173.67 |

639.16 |

| Database (MongoDB) |

23.62 |

413.77 |

0.43 |

954.46 |

1765.49 |

| REST API |

9.02 |

87.99 |

0.09 |

0.02 |

0.00 |

For comparison,

Table 3 shows the resource averages obtained with 10 concurrent simulations. This configuration presented higher per-container CPU utilization but less aggregate contention, resulting in shorter execution time and reduced network I/O.

Observations:

The observed execution behavior indicates that increasing the number of concurrent simulation containers beyond the number of available CPU cores leads to reduced efficiency, mainly due to CPU saturation and operating system scheduling overhead rather than memory exhaustion. While the configuration with 30 containers increased the overall level of parallel activity, it did not translate into proportional reductions in total execution time. In contrast, the 10-container configuration exhibited higher per-container efficiency, benefiting from more stable CPU allocation.

These observations support the architectural design choices by demonstrating that the proposed system can coordinate and execute distributed simulations reliably under varying concurrency levels. At the same time, they highlight the importance of aligning container density with available computational resources. Rather than serving as domain-level performance results, these executions validate the feasibility of the orchestration model and motivate future work on adaptive scheduling and resource-aware execution strategies built on top of the proposed architecture.

This behavior is consistent with well-known limitations of shared-memory execution environments and does not represent a limitation of the architectural model itself.

5.3. NSGA Integration

When the NSGA module is used, the optimization follows an evolutionary process where each individual represents a WSN configuration. After each simulation, the objectives (coverage, latency, energy) are evaluated and used to evolve the population.

Figure 4.

Integration of NSGA into the distributed experiment workflow of the architecture.

Figure 4.

Integration of NSGA into the distributed experiment workflow of the architecture.

Throughout this work, the term NSGA is used in a generic sense to refer to the implemented evolutionary framework, as the underlying model allows seamless switching between NSGA-II and NSGA-III by modifying only the environmental selection operator, without affecting the remaining components of the optimization pipeline.

6. Discussion

This discussion is framed explicitly from an architectural and methodological perspective. Rather than interpreting the prototype executions as domain-level experimental results, the analysis focuses on how the observed system behavior supports and illustrates the architectural principles proposed in this work, namely reactive orchestration, modular separation of concerns, and reproducibility by construction.

The proposed architecture should not be interpreted merely as an engineering artifact, but as a concrete instantiation of a conceptual model for simulation-based optimization workflows. The prototype implementation demonstrates that key ideas commonly discussed in abstract terms in the literature can be realized coherently in a distributed setting, providing a practical reference for future experimental infrastructures.

A first concept strongly supported by the implementation is the adoption of an event-driven execution model centered on persistent database state. By treating experiments, generations, and simulations as explicit and durable entities, and by driving progress through well-defined events such as ExperimentCreated, GenerationReady, and SimulationCompleted, the architecture shows that distributed components can be coordinated without tightly coupled communication mechanisms. This database-centric and event-oriented approach provides a robust backbone for optimization workflows in which simulation, evaluation, and search proceed asynchronously and may evolve at different rates.

A second architectural concept illustrated by the system is the clear separation between optimization logic and simulation backends. The formal model defines a generic evaluation function , and the implementation demonstrates that this function can be instantiated either through a packet-level network simulator or through a synthetic dummy backend, without altering the overall execution semantics. This decoupling indicates that the same experimental pipeline can be reused across different problem classes and simulation technologies, provided that they expose compatible interfaces for parameter configuration and objective reporting. As a consequence, the architecture supports extensibility not by modification, but by substitution of components.

Reproducibility and traceability constitute a third central concept addressed at the architectural level. By storing experiment definitions, generation structures, simulation parameters, and result metrics as immutable records, each execution becomes a self-contained and reproducible object. Containerized simulations further ensure consistency of the execution environment, while the event stream preserves a chronological account of state transitions and decision points. This design illustrates that reproducibility can be enforced by construction, rather than treated as an external requirement addressed after experiments are completed.

The execution examples also shed light on the interaction between parallelism and resource constraints. In this context, parallelism refers to software-level distributed execution, where multiple simulation instances are orchestrated concurrently, rather than to true hardware-level parallelism. The comparison between different levels of concurrent simulation reveals that increasing the degree of such distributed execution does not necessarily lead to proportional reductions in total execution time. Instead, contention for shared resources, particularly CPU time, can become a limiting factor and reduce overall efficiency.

Another important methodological aspect concerns the role of the dummy simulator. Although initially introduced to facilitate testing and debugging, its inclusion reveals a broader benefit. By providing a controlled environment with parametric or predictable behavior, the dummy backend enables systematic investigation of optimization algorithms, including convergence dynamics, parameter sensitivity, and robustness to noise, without the confounding effects of complex network interactions. This observation reinforces the idea that comprehensive experimental frameworks should support both high-fidelity simulations and simplified models that enable analytical insight.

The architecture further illustrates how a single experimental infrastructure can accommodate a wide range of multi-objective WSN problems. While this work does not target a specific optimization task, the combination of a flexible solution space X, a configurable parameter space , and a modular evaluation function allows the encoding of problems such as sensor placement, relay selection, multi-hop routing, and resource management. In these cases, the underlying orchestration, storage, and execution mechanisms remain unchanged, suggesting a high degree of generality in the proposed approach.

Despite these strengths, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The current implementation is instantiated with a specific simulator and database technology, and the prototype executions were conducted on a single computational host. Extending the architecture to heterogeneous clusters, cloud environments, or alternative simulation engines will require additional engineering effort and may introduce new challenges related to latency, storage throughput, and fault tolerance. Moreover, while the framework captures all relevant experimental data, advanced analytical tools for automated Pareto front analysis, statistical assessment, and interactive visualization are not yet fully integrated.

In summary, the proposed architecture provides architectural evidence for a set of key principles in simulation-based multi-objective optimization research, including event-driven orchestration, modular separation of optimization and simulation, explicit support for reproducibility, and resource-aware parallel execution. Although motivated by WSN experimentation, these principles are not domain-specific and can be transferred to other areas that rely on large-scale simulation and optimization. The architecture therefore serves both as a practical platform and as a reference design for future experimental infrastructures.

7. Conclusions

This work presented a modular and scalable architecture for multi-objective optimization experiments in WSNs. Its design enables reproducible, distributed, and easily extensible experimentation workflows. Beyond its immediate use for WSN experiments, the architecture provides a flexible foundation for other distributed or simulation-based optimization domains. Its modularity allows the integration of alternative optimization strategies, machine learning components, or analytical models while maintaining a standardized data pipeline.

Future developments include:

developing a robust software platform with a graphical user interface (GUI) to support research and experimentation with wireless sensor networks;

integrating additional simulators beyond Cooja to extend the applicability of the framework to different network environments;

employing the architecture as a foundation for designing new optimization techniques tailored to WSNs;

creating advanced visualization and analytical tools for Pareto front exploration and decision support;

incorporating graphical resources to aid researchers in the visual interpretation and comparative analysis of simulation results;

integrating mathematical and analytical models to enhance the performance of both simulations and optimization algorithms;

to produce a well-documented experimentation platform that promotes collaborative use, reproducibility, and reuse throughout the scientific community.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.F. and J.C.E.; methodology, J.C.F.; software, J.C.F.; validation, J.C.F. and J.C.E.; writing—original draft, J.C.F.; writing—review and editing, J.C.E., C.F.M.T and A.C.B.D.; supervision, J.C.E., C.F.M.T, and A.C.B.D.

Funding

This research was supported by institutional resources from ICMC–USP.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the computational infrastructure provided by the Laboratory of Distributed Systems and Concurrent Programming (LaSDPC) at ICMC–USP.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hart, J.K.; Martinez, K. Environmental Sensor Networks: A Revolution in the Earth System Science? 78, 177–191. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Ming, Y.; Chakraborty, S.; Iram, S. A Comprehensive Survey on Real-Time Applications of WSN. 9, 77. [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.J.; Saqib, S.; Ahmad, R.F.; Khan, H. Leveraging Wireless Sensor Networks for Real-Time Monitoring and Control of Industrial Environments. [CrossRef]

- Musa, P.; Sugeru, H.; Wibowo, E.P. Wireless Sensor Networks for Precision Agriculture: A Review of NPK Sensor Implementations. 24, 51. [CrossRef]

- Khalifeh, A.; Darabkh, K.A.; Khasawneh, A.M.; Alqaisieh, I.; Salameh, M.; AlAbdala, A.; Alrubaye, S.; Alassaf, A.; Al-HajAli, S.; Al-Wardat, R.; et al. Wireless Sensor Networks for Smart Cities: Network Design, Implementation and Performance Evaluation. 10, 218. [CrossRef]

- Fei, Z.; Li, B.; Yang, S.; Xing, C.; Chen, H.; Hanzo, L. A Survey of Multi-Objective Optimization in Wireless Sensor Networks: Metrics, Algorithms, and Open Problems. 19, 550–586. [CrossRef]

- Kandris, D.; Alexandridis, A.; Dagiuklas, T.; Panaousis, E.; Vergados, D.D. Multiobjective Optimization Algorithms for Wireless Sensor Networks; 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thekkil, T.M.; Prabakaran, N. A Multi-Objective Optimization for Remote Monitoring Cost Minimization in Wireless Sensor Networks. 121, 1049–1065. [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A Fast and Elitist Multiobjective Genetic Algorithm. 6, 182–197. [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Jain, H. An Evolutionary Many-Objective Optimization Algorithm Using Reference-Point-Based Nondominated Sorting Approach, Part I: Solving Problems With Box Constraints. 18, 577–601. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Deb, K.; Zhang, Q.; Suganthan, P.; Chen, L. Comparison between MOEA/D and NSGA-III on a Set of Novel Many and Multi-Objective Benchmark Problems with Challenging Difficulties. 46, 104–117. [CrossRef]

- Gunjan. A Review on Multi-objective Optimization in Wireless Sensor Networks Using Nature Inspired Meta-heuristic Algorithms. 55, 2587–2611. [CrossRef]

- Moshref, M.; Al-Sayyed, R.; Al-Sharaeh, S. MULTI-OBJECTIVE OPTIMIZATION ALGORITHMS FOR WIRELESS SENSOR NETWORKS: A COMPREHENSIVE SURVEY.

- Egea-Lopez, E.; Vales-Alonso, J.; Martinez-Sala, A.; Pavon-Mario, P.; Garcia-Haro, J. Simulation Scalability Issues in Wireless Sensor Networks. 44, 64–73. [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Tang, K. Large-Scale Multi-Objective Evolutionary Optimization.

- Oikonomou, G.; Duquennoy, S.; Elsts, A.; Eriksson, J.; Tanaka, Y.; Tsiftes, N. The Contiki-NG Open Source Operating System for next Generation IoT Devices. 18, 101089. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Hussain, S. Simulation Model For Wireless Body Area Network Using Castalia. In Proceedings of the 2022 1st International Conference on Informatics (ICI); IEEE; pp. 204–207. [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, G.; Fontes, H.; Ricardo, M. Fast Prototyping of Network Protocols through Ns-3 Simulation Model Reuse. 19, 2063–2075. [CrossRef]

- Riliskis, L.; Osipov, E. Maestro: An Orchestration Framework for Large-Scale WSN Simulations. 14, 5392–5414. [CrossRef]

- Harwell, J.; Gini, M. SIERRA: A Modular Framework for Accelerating Research and Improving Reproducibility. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); IEEE; pp. 9111–9117. [CrossRef]

- Sarikhani, M.; Wendelborn, A. Mechanisms for Provenance Collection in Scientific Workflow Systems. 100, 439–472. [CrossRef]

- Santana-Perez, I.; Pérez-Hernández, M.S. Towards Reproducibility in Scientific Workflows: An Infrastructure-Based Approach 2015, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.M.; Kim, H.J. WSN-SES/MB: System Entity Structure and Model Base Framework for Large-Scale Wireless Sensor Networks. 21, 430. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.M.A.; Azevedo, L.J.D.M.D.; Estrella, J.C.; Delbem, A.C.B. Case Studies with the Contiki-NG Simulator to Design Strategies for Sensors’ Communication Optimization in an IoT-Fog Ecosystem. 23, 2300. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.M.A. Projeto e Análise de Rede de Sensores em Névoa utilizando uma Abordagem com Otimização Multiobjetivo. [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, G. Convergence Analysis of Canonical Genetic Algorithms. 5, 96–101. [CrossRef]

- Zitzler, E.; Thiele, L. Multiobjective Evolutionary Algorithms: A Comparative Case Study and the Strength Pareto Approach. 3, 257–271. [CrossRef]

- Deb, K. Multiobjective Optimization: Interactive and Evolutionary Approaches. Number v.5252 in Lecture Notes in Computer Science Ser; Springer Berlin / Heidelberg.

- Liu, J.; Sarker, R.; Elsayed, S.; Essam, D.; Siswanto, N. Large-Scale Evolutionary Optimization: A Review and Comparative Study. 85, 101466. [CrossRef]

- MongoDB, Inc. Change Streams — Database Manual. In MongoDB official documentation; MongoDB, Inc., 2025. [Google Scholar]

- MongoDB; Inc. An Introduction to Change Streams, 2025. MongoDB documentation on Change Streams capabilities.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).