Submitted:

08 January 2026

Posted:

09 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Therapy Dog Sample

2.2. Salivary Cortisol Analysis

2.3. Urine Cortisol Analysis

2.4. Urine-Cortisol-Creatinine Ratio Analysis

2.5. Hair Cortisol Analysis

2.6. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

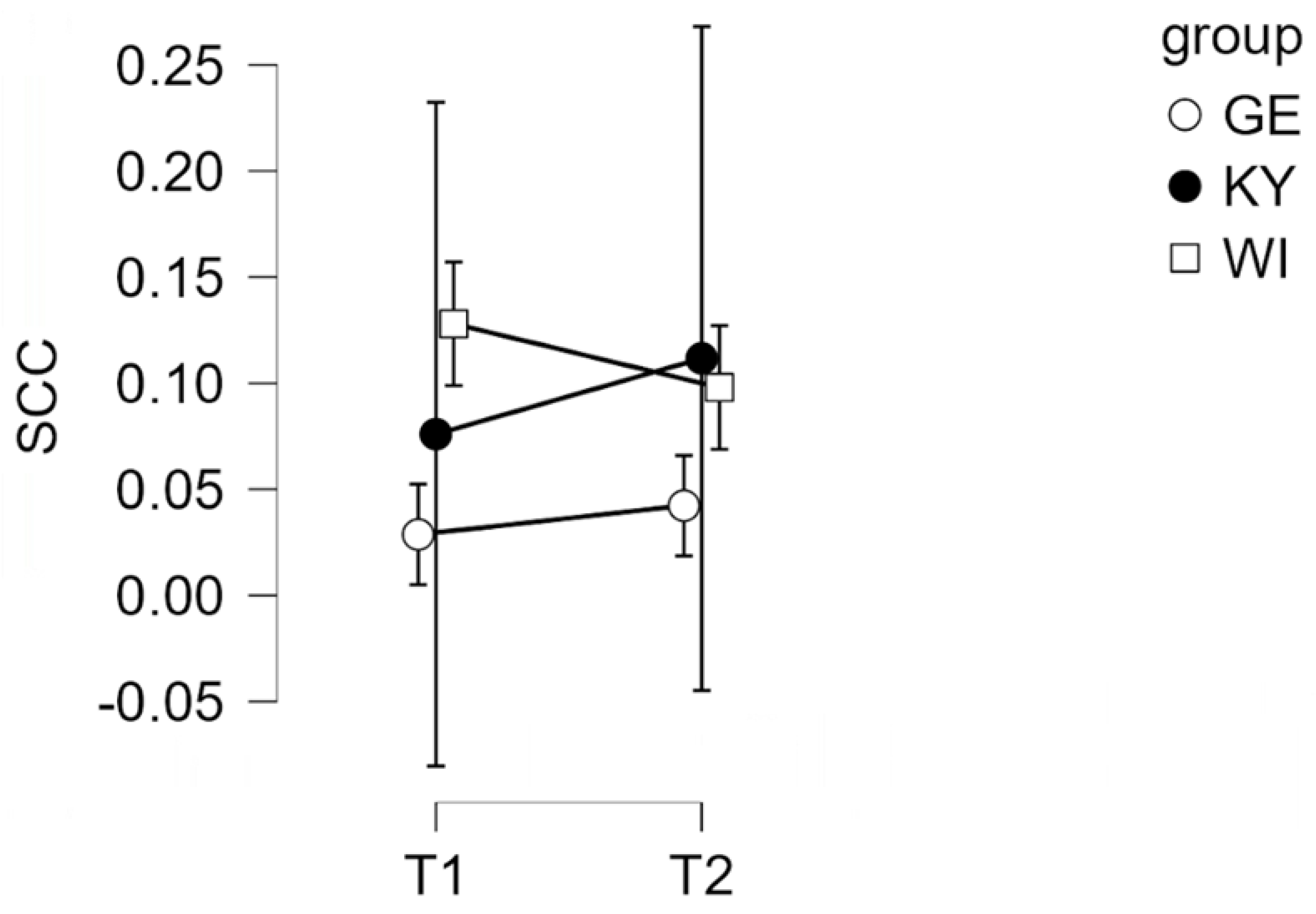

3.2. Salivary Cortisol (SCC)

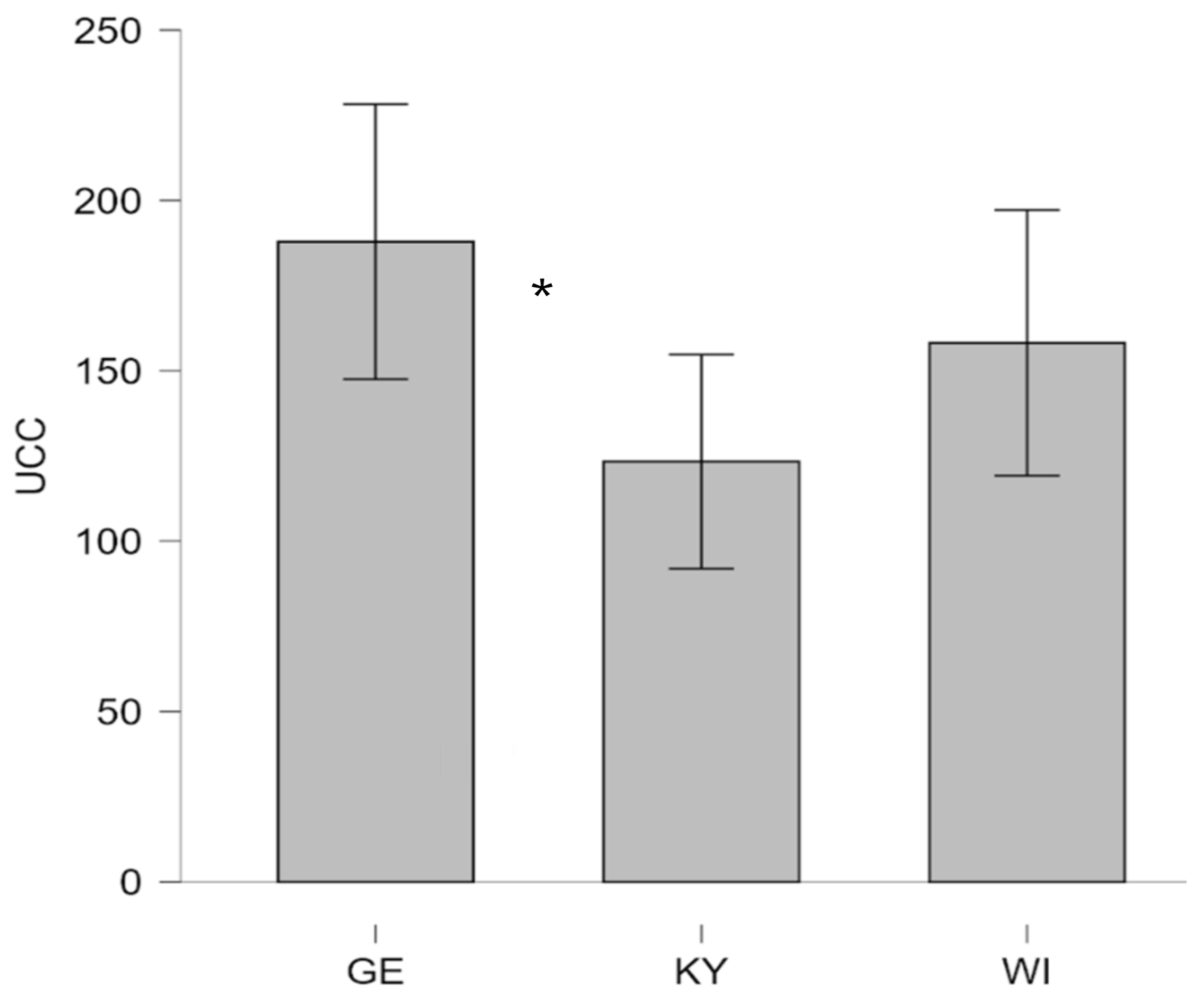

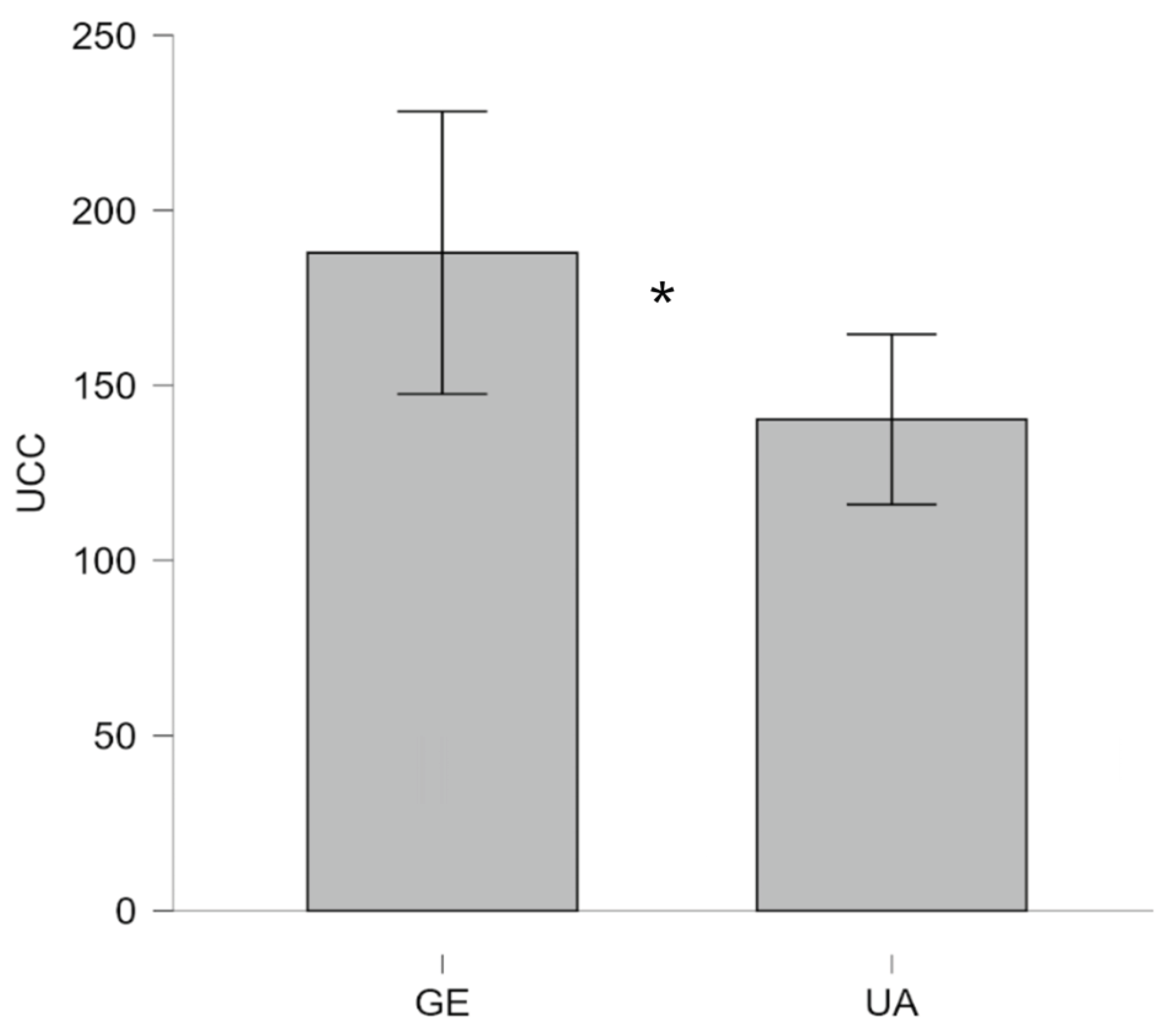

3.3. Urinary Cortisol (UCC)

3.4. Urine-Cortisol-Creatinine Ratio analysis (UCCR)

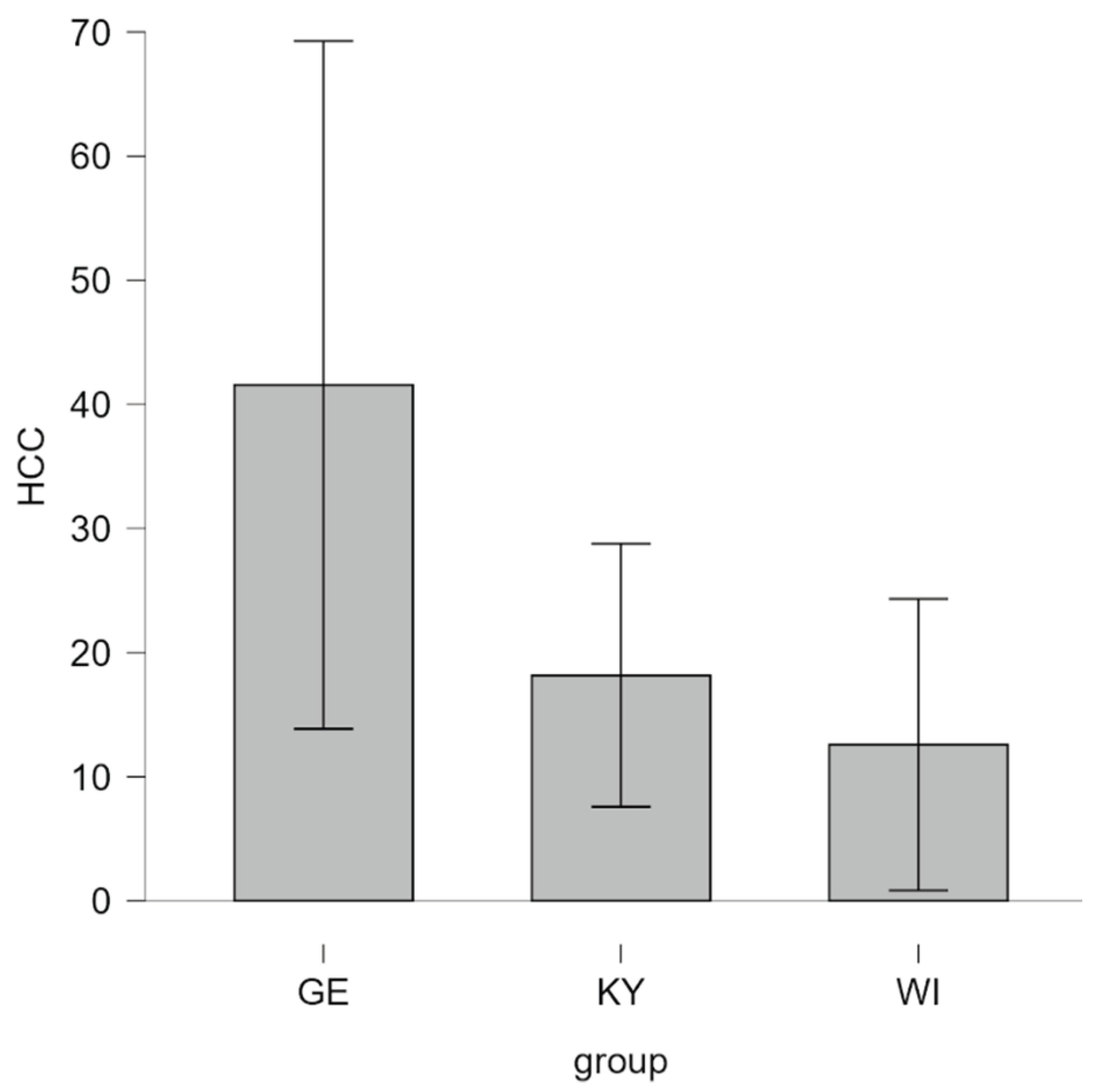

3.5. Hair Cortisol Concentrations (HCC)

4. Discussion

4.1. Salivary Cortisol (SCC)

4.2. Urinary Cortisol (UCC)

4.3. Hair Cortisol (HCC)

4.4. Handler Related Factors

4.5. Animal Welfare Strategies

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shvets, A.; Sereda, I.; Lopin, E. The medical and social importance of mental and behavior disorders among military personnel in peacetime and warfare. Rom. J. Mil. Med. 2021, 124, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnodemska, I.; Savitskaya, M.; Berezan, V.; Tovstukha, O.; Rodchenko, L. Psychological consequences of warfare for combatants: Ways of social reintegration and support in Ukraine. Amazon. Investig. 2023, 12, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alupo, C. Canine PTSD . Ph.D. Thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Skara, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alger, J.M.; Alger, S.F. Canine soldiers, mascots, and stray dogs in U.S. wars: Ethical considerations. In Animals and War; Hediger, R., Ed.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ksenofontova, A.A.; Voinova, O.A.; Ivanov, A.A.; Ksenofontov, D.A. Behavioral veterinary medicine: A new direction in the study of behavioral disorders in companion animals. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 11A10O. [Google Scholar]

- Haq, A.U. Canine psychiatry: Addressing animal psychopathologies. Behav. Sci. 2017, 6, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, D.L. Domestic dogs and human health: An overview. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liguori, G.; Costagliola, A.; Lombardi, R.; Paciello, O.; Giordano, A. Human–animal interaction in animal-assisted interventions (AAIs): Zoonosis risks, benefits, and future directions—A One Health approach. Animals 2023, 13, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomuzzi, S.; Kocharian, A.; Barinova, N.; Barinov, S. Experiencing and coping with trauma in warfare and military conflicts. Psychol. Couns. Psychother. 2021, 16, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, A.; Sikder, I.; Wang, S.; Barrett, E.S.; Fiedler, N.; Ahmad, M.; Haque, U. Parent–child mental health in Ukraine in relation to war trauma and drone attacks. Compr. Psychiatry 2025, 139, 152590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottola, F.; Gnisci, A.; Kalaitzaki, A.; Vintilă, M.; Sergi, I. The impact of the Russian–Ukrainian war on the mental health of Italian people after two years of the pandemic: Risk and protective factors as moderators. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1154502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, R.S.; Lakshminarayana, R. Mental health consequences of war: A brief review of research findings. World Psychiatry 2006, 5, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu, T.C.; Dejean, C.; Jercog, D.; Aouizerate, B.; Lemoine, M.; Herry, C. The advent of fear conditioning as an animal model of post-traumatic stress disorder: Learning from the past to shape the future of PTSD research. Neuron 2021, 109, 2380–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucki, S. Animal warfare law and the need for an animal law of peace: A comparative reconstruction. Am. J. Comp. Law 2023, 71, 189–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucki, S. Beyond Animal Warfare Law: Humanizing the 'War on Animals' and the Need for Complementary Animal Rights; MPIL Research Paper 2021-10, Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law & International Law, 2021.

- Salden, S.; Wijnants, J.; Baeken, C.; Saunders, J.; De Keuster, T. Trauma and its behavioral aftermath: A systematic review of the impact of disaster deployment on working dogs. In Proceedings of the 5th European Veterinary Congress of Behavioural Medicine and Animal Welfare (EVCBMAW 2023); Vol. 9, No. 1; pp. 80–81.

- Sacoor, C.; Marugg, J.D.; Lima, N.R.; Empadinhas, N.; Montezinho, L. Gut–brain axis impact on canine anxiety disorders: New challenges for behavioral veterinary medicine. Vet. Med. Int. 2024, 2024, 2856759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hediger, R. Animals in war. In The Palgrave International Handbook of Animal Abuse Studies; Maher, J., Pierpoint, H., Beirne, P., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milburn, J.; Van Goozen, S. Animals and the ethics of war: a call for an inclusive just-war theory. Int. Relat. 2023, 37, 423–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemish, M.G. War Dogs: A History of Loyalty and Heroism; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tsouparopoulou, C.; Recht, L. Dogs and equids in war in third millennium BC Mesopotamia. In Fierce Lions, Angry Mice and Fat-tailed Sheep: Animal Encounters in the Ancient Near East; pp. 279–289.

- Ukraine, ua. Patron, the Ukrainian Bomb-Detecting Dog. Ukraine.ua, 2022. Available online: https://ukraine.ua/faq/patron-ukrainian-bomb-sniffing-dog/ (accessed on 08 December 2025).

- Walsh, E.A.; Meers, L.L.; Samuels, W.E.; Boonen, D.; Claus, A.; Duarte-Gan, C.; Normando, S. Human–dog communication: How body language and non-verbal cues are key to clarity in dog-directed play, petting and hugging behaviour by humans. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2024, 272, 106206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kateryna, M.; Trofimov, A.; Vsevolod, Z.; Tetiana, A.; Liudmyla, K. The role of pets in preserving the emotional and spiritual wellbeing of Ukrainian residents during Russian hostilities. J. Relig. Health 2023, 62, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandvik, K.B. The Ukrainian refugee crisis: Unpacking the politics of pet exceptionalism. Int. Migr. 2023, 61, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, M.; Otto, C.M.; Serpell, J.A.; Alvarez, J. Interactions between handler well-being and canine health and behavior in search and rescue teams. Anthrozoös 2012, 25, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leighton, S.C.; Nieforth, L.O.; O’Haire, M.E. Assistance dogs for military veterans with PTSD: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-synthesis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, K.E.; LaFollette, M.R.; Hediger, K.; Ogata, N.; O’Haire, M.E. Defining the PTSD service dog intervention: Perceived importance, usage, and symptom specificity of psychiatric service dogs for military veterans. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 519718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcelos, A.M.; Kargas, N.; Assheton, P.; Maltby, J.; Hall, S.; Mills, D.S. Dog owner mental health is associated with dog behavioural problems, dog care and dog-facilitated social interaction: A prospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskela, A.; Törnqvist, H.; Somppi, S.; Tiira, K.; Kykyri, V.L.; Hänninen, L.; Kujala, M.V. Behavioral and emotional co-modulation during dog–owner interaction measured by heart rate variability and activity. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, A.; Mok, P.; Fung, W.K. The rich history and evolution of animal-assisted therapy. J. Altern. Complement. Integr. Med. 2024, 10, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenk, L.M.; Kothgassner, O.D. Life out of balance: Stress-related disorders in animals and humans. In Comparative Medicine; Jensen-Jarolim, E., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.J.; Antonaccio, O.; Botchkovar, E.; Hobfoll, S.E. War trauma and PTSD in Ukraine’s civilian population: Comparing urban-dwelling to internally displaced persons. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 1807–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minervini, G.; Franco, R.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Fiorillo, L.; Cervino, G.; Cicciu, M. Post-traumatic stress, prevalence of temporomandibular disorders in war veterans: Systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Oral Rehabil. 2023, 50, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schincariol, A.; Orrù, G.; Otgaar, H.; Sartori, G.; Scarpazza, C. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) prevalence: An umbrella review. Psychol. Med. 2024, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshel, Y.; Kimhi, S.; Marciano, H.; Adini, B. Predictors of PTSD and psychological distress symptoms of Ukraine civilians during war. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2023, 17, e429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaszycka, K.; Goleman, M.; Krupa, W. Testing the level of cortisol in dogs. Animals 2025, 15, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, J.E.; Vinke, C.M.; Arndt, S.S. Evaluation of hair cortisol as an indicator of long-term stress responses in dogs in an animal shelter and after subsequent adoption. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi Nejad, J.; Ghaffari, M.H.; Ataallahi, M.; Jo, J.H.; Lee, H.G. Stress concepts and applications in various matrices with a focus on hair cortisol and analytical methods. Animals 2022, 12, 3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.esaat.org/.

- https://isaat.org/.

- Davenport, M.D.; Tiefenbacher, S.; Lutz, C.K.; Novak, M.A.; Meyer, J.S. Analysis of endogenous cortisol concentrations in the hair of rhesus macaques. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2006, 147, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.; Hayssen, V. Measuring cortisol in hair and saliva from dogs: Coat color and pigment differences. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2010, 39, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, R.M.; Davies, A.M.; Volk, H.A.; Puckett, H.L.; Hobbs, S.L.; Fowkes, R.C. What can we learn from the hair of the dog? Complex effects of endogenous and exogenous stressors on canine hair cortisol. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, E.L.; Martinez, D.A. The effect size in scientific publication. Educ. XX1 2023, 26, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, J.R.; Stephens, M.A.; Fotopoulos, S. Asymptotic distribution of the Shapiro–Wilk W for testing normality. Ann. Stat. 1986, 14, 1497–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foltin, S.; Glenk, L.M. Current perspectives on the challenges of implementing assistance dogs in human mental health care. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenk, L.M.; Foltin, S. Therapy dog welfare revisited: A review of the literature. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, L.; Gee, N.R. Recognizing and mitigating canine stress during animal assisted interventions. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenk, L.M.; Kothgassner, O.D.; Stetina, B.U.; Palme, R.; Kepplinger, B.; Baran, H. Therapy dogs’ salivary cortisol levels vary during animal-assisted interventions. Anim. Welfare 2013, 22, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kateřina, K.; Kristýna, M.; Radka, P.; Aneta, M.; Štěpán, Z.; Ivona, S. Evaluation of cortisol levels and behavior in dogs during animal-assisted interventions in clinical practice. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2024, 277, 106321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenk, L.M.; Kothgassner, O.D.; Stetina, B.U.; Palme, R.; Kepplinger, B.; Baran, H. Salivary cortisol and behavior in therapy dogs during animal-assisted interventions: A pilot study. J. Vet. Behav. 2014, 9, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerda, B.; Schilder, M.B.H.; Van Hooff, J.A.R.A.M.; De Vries, H.W.; Mol, J.A. Behavioural and hormonal indicators of enduring environmental stress in dogs. Anim. Welfare 2000, 9, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haubenhofer, D.K.; Kirchengast, S. Physiological arousal for companion dogs working with their owners in animal-assisted activities and animal-assisted therapy. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 2006, 9, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreschel, N.A.; Granger, D.A. Methods of collection for salivary cortisol measurement in dogs. Horm. Behav. 2009, 55, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinella, G.; Tidu, L.; Grassato, L.; Musella, V.; Matarazzo, M.; Valentini, S. Military working dogs operating in Afghanistan theater: Comparison between pre- and post-mission blood analyses to monitor physical fitness and training. Animals 2022, 12, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mormède, P.; Andanson, S.; Aupérin, B.; Beerda, B.; Guémené, D.; Malmkvist, J.; et al. Exploration of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal function as a tool to evaluate animal welfare. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corte, S.M.; Olivier, B.; Koolhaas, J.M. A new animal welfare concept based on allostasis. Physiol. Behav. 2005, 92, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbiydzenyuy, N.E.; Qulu, L.A. Stress, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis, and aggression. Metab. Brain Dis. 2024, 39, 1613–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehrner, A.; Daskalakis, N.; Yehuda, R. Cortisol and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in PTSD. In Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; 2016; pp. 265–290. [Google Scholar]

- Guilliams, T.G.; Edwards, L. Chronic stress and the HPA axis. Standard 2010, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Del Baldo, F.; Gerou Ferriani, M.; Bertazzolo, W.; Luciani, M.; Tardo, A. M.; Fracassi, F. Urinary cortisol-creatinine ratio in dogs with hypoadrenocorticism. J Vet Inter Med 2022, 36, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeugswetter, F.; Bydzovsky, N.; Kampner, D.; Schwendenwein, I. Tailored reference limits for urine corticoid: creatinine ratio in dogs to answer distinct clinical questions. Vet Record 2010, 167, 997–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariti, C.; Russo, G.; Mazzoni, C.; Borrelli, C.; Gori, E.; Habermaass, V.; Marchetti, V. Factors affecting hair cortisol concentration in domestic dogs: A focus on factors related to dogs and their guardians. Animals 2025, 15, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, L.S.V.; Faresjö, Å.; Theodorsson, E.; Jensen, P. Hair cortisol varies with season and lifestyle and relates to human interactions in German shepherd dogs. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimbürge, S.; Kanitz, E.; Otten, W. The use of hair cortisol for the assessment of stress in animals. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2019, 270, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Xu, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Song, M.; Zhao, J. Investigating hair cortisol dynamics in German Shepherd Dogs throughout pregnancy, lactation, and weaning phases, and its potential impact on the hair cortisol of offspring. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2025, 92, 106921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mârza, S.M.; Munteanu, C.; Papuc, I.; Radu, L.; Diana, P.; Purdoiu, R.C. Behavioral, physiological, and pathological approaches of cortisol in dogs. Animals 2024, 14, 3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi Nejad, J.; Ghaffari, M.H.; Ataallahi, M.; Jo, J.H.; Lee, H.G. Stress concepts and applications in various matrices with a focus on hair cortisol and analytical methods. Animals 2022, 12, 3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusch, J.M.; Matzke, C.C.; Lane, J.E. Social buffering reduces hair cortisol content in black-tailed prairie dogs during reproduction. Behaviour 2023, 160, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudielka, B.M.; Bellingrath, S.; Hellhammer, D.H. Cortisol in burnout and vital exhaustion: An overview. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2006, 28, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Corsetti, S.; Ferrara, M.; Natoli, E. Evaluating stress in dogs involved in animal-assisted interventions. Animals 2019, 9, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenegger, H.C.; Marques, M.D.; Becker, L.; Rohleder, N.; Nowak, D.; Wright, B.J.; Weigl, M. Prospective associations of technostress at work, burnout symptoms, hair cortisol, and chronic low-grade inflammation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 117, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitropoulos, T.; Andrukonis, A. Dog owners’ job stress crosses over to their pet dogs via work-related rumination. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcelos, A.M.; Kargas, N.; Mills, D. The effects of dog behavioural problems on owner well-being: A review of the literature and future directions. Pets 2024, 1, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erichsmeier, R.; Arney, D.; Soonberg, M. Behavioral observations of dogs during animal-assisted interventions and their handlers’ perceptions of their experienced level of stress. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 2025, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesi, B.C.; Palestrini, C.; Buttram, D.; Mazzola, S.; Cannas, S. Stress and burnout in dogs involved in animal assisted interventions: A survey of Italian handlers’ opinion. J. Vet. Behav. 2025, 78, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, A. Considering the “dog” in dog–human interaction. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 642821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, A. Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know; Simon and Schuster: New York, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Santaniello, A.; Garzillo, S.; Cristiano, S.; Fioretti, A.; Menna, L.F. The research of standardized protocols for dog involvement in animal-assisted therapy: A systematic review. Animals 2021, 11, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, A.H.; Griffin, T.C. Protecting animal welfare in animal-assisted intervention: Our ethical obligation. Semin. Speech Lang. 2022, 43, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, L.S.; Faresjö, Å.; Theodorsson, E.; Jensen, P. Hair cortisol varies with season and lifestyle and relates to human interactions in German shepherd dogs. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundman, A.S.; Van Poucke, E.; Svensson Holm, A.C.; Faresjö, Å.; Theodorsson, E.; Jensen, P.; Roth, L.S. Long-term stress levels are synchronized in dogs and their owners. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| GE | UA | GE | UA | ||||||||||||

| n | 17 | 39 | 17 | 39 | |||||||||||

| Age in years | Age in months | ||||||||||||||

| M | 3.765 | 5.872 | 48.06 | 74.46 | |||||||||||

| SD | 2.635 | 4.366 | 30.77 | 51.58 | |||||||||||

| W (Shapiro-Wilk) | 0.862 | 0.856 | 0.879 | 0.869 | |||||||||||

| p of Shapiro-Wilk | .017 | < .001 | .030 | < .001 | |||||||||||

| Minimum | 1.000 | 1.000 | 12.00 | 12.00 | |||||||||||

| Maximum | 11.00 | 19.00 | 134.0 | 233.0 | |||||||||||

| sex: female | n = 8 | n = 19 | |||||||||||||

| sex: male | n = 9 | n = 19 | |||||||||||||

| sex: missing | n = 1 | ||||||||||||||

| GE | KY | WI | GE | KY | WI | ||||||||

| n | 17 | 19 | 20 | 17 | 19 | 20 | |||||||

| Age in years | Age in months | ||||||||||||

| M | 3.765 | 5.579 | 6.150 | 48.06 | 71.47 | 77.30 | |||||||

| SD | 2.635 | 3.963 | 4.804 | 30.77 | 47.94 | 55.92 | |||||||

| W (Shapiro-Wilk) | 0.862 | 0.895 | 0.808 | 0.879 | 0.911 | 0.813 | |||||||

| p of Shapiro-Wilk | .017 | .040 | .001 | .030 | .079 | .001 | |||||||

| Minimum | 1.000 | 1.000 | 2.000 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 28.00 | |||||||

| Maximum | 11.00 | 17.00 | 19.00 | 134.0 | 206.0 | 233.0 | |||||||

| sex: female | n = 8 | n = 7 | n = 12 | ||||||||||

| sex: male | n = 9 | n = 12 | n = 7 | ||||||||||

| sex: missing | n = 1 | ||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).