1. Introduction

Homomorphic encryption (HE) is a cryptographic technology that enables computations to be performed directly on encrypted data. Dubbed the "holy grail" of cryptography, HE holds enormous application potential in the field of information security. Based on the scope of homomorphic computations supported, HE can be categorized into Partial Homomorphic Encryption (PHE), Leveled Homomorphic Encryption (LHE), and Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE). Early research on HE focused on PHE, with representative schemes including the RSA scheme proposed by Rivest et al. [

2] and the Paillier encryption scheme [

3] developed later. The RSA scheme exhibits multiplicative homomorphism—decrypting the product of two ciphertexts yields the product of the corresponding plaintexts. In contrast, the Paillier scheme possesses additive homomorphism—decrypting the product of two ciphertexts results in the sum of the corresponding plaintexts. However, PHE schemes are highly restrictive as they only support either additive or multiplicative homomorphism. Decades after the concept of "homomorphic encryption" was proposed, Gentry [

4] introduced a framework for constructing FHE, shifting academic focus from PHE to LHE and FHE. LHE supports both additive and multiplicative operations on ciphertexts, and the resulting new ciphertexts are encryptions of the corresponding plaintext sums or products. Nevertheless, LHE does not allow unlimited homomorphic computations—if the noise accumulated after each computation exceeds the scheme’s tolerance threshold, the ciphertext will fail to decrypt. Gentry’s FHE framework consists of LHE and bootstrapping. The core idea of bootstrapping is to execute a homomorphic decryption circuit on the ciphertext before the noise reaches the threshold. As long as the noise of the bootstrapped ciphertext remains sufficiently low to support one additional homomorphic operation, LHE can be transformed into FHE.

Existing bootstrapping methods primarily fall into three categories. The first category is tailored for BGV/BFV schemes [

5,

6,

7,

8], leveraging the Chinese Remainder Theorem (CRT) over polynomial rings. Its core idea involves re-encrypting the original ciphertext and then decrypting the inner-layer ciphertext of the new ciphertext. The second category is designed for the CKKS scheme [

9]. Since CKKS ciphertexts treat noise as part of the plaintext, the decryption function is replaced by an approximate modulus function, with the remaining steps closely resembling those of the first category. The third category is the bootstrapping based on blind rotation in TFHE schemes [

10,

11]. Unlike the previous two, blind rotation utilizes the negative cyclic property of the polynomial ring

. By iteratively multiplying the rotation polynomial with key-related monomials, specific coefficients of the rotation polynomial are rotated to the constant term in the encrypted state, thereby achieving homomorphic decryption. In TFHE, blind rotation consists of two types of ciphertexts (RLWE and RGSW) and their "external product". Given the large size of these two ciphertext types, Bonte et al. [

12] proposed the NTRU-based FINAL scheme to reduce the size of bootstrapping keys. The FINAL scheme replaces RLWE and RGSW ciphertexts with scalar NTRU and vector NTRU ciphertexts, respectively. Since scalar NTRU ciphertexts consist of only one polynomial, and the size of vector NTRU ciphertexts is half that of RGSW ciphertexts, the NTRU-based bootstrapping algorithm not only offers superior space complexity but also requires fewer polynomial multiplications for executing the "external product" compared to TFHE.

The primary application of FHE is outsourcing computation, where data owners can encrypt their data and entrust it to untrusted computing service providers without revealing sensitive information. However, in secure multi-party computation (SMPC) scenarios, there is a need to compute data from multiple sources, rendering single-key FHE inadequate. To meet this demand, researchers have extended FHE to multi-party settings, leading to two main technical routes: static Multi-Party Homomorphic Encryption (MPHE) [

13,

14,

15] and dynamic Multi-Key Homomorphic Encryption (MKHE) [

16,

17,

18]. MPHE requires parties to be fixed prior to computation, with various keys generated collectively by all parties. Since encryption, decryption, and bootstrapping are performed under the same key, its computational efficiency is independent of the number of parties, ensuring high efficiency but limited flexibility. In contrast, MKHE does not require pre-computation negotiation among parties—each party generates its own key and participates in encryption, decryption, and bootstrapping without disclosing any key-related information. However, the size of multi-key ciphertexts is positively correlated with the number of parties, resulting in high flexibility but low computational efficiency. To balance flexibility and efficiency, Kwak et al. [

19] proposed a new HE primitive called Multi-Group Homomorphic Encryption (MGHE). MGHE treats ciphertexts of MPHE as single-key ciphertexts under a joint public key, while ciphertexts encrypted under joint public keys of different groups are computed jointly in a multi-key manner. In the initial MGHE construction, bootstrapping adheres to the first, second, and third methods based on RLWE and RGSW, lacking support for NTRU-based blind rotation bootstrapping. To harness the advantages of the FINAL scheme and enhance the practicality of MGHE, this study designs an NTRU-based bootstrapping algorithm for multi-group LWE ciphertexts. Specifically, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- 1.

A secret sharing-based bootstrapping key generation algorithm is proposed. The FINAL scheme lacks an asymmetric encryption variant, and existing NTRU-based blind rotation algorithms [

20,

21] employ symmetrically encrypted bootstrapping keys. To ensure compatibility between the proposed bootstrapping algorithm and NTRU-based blind rotation while maintaining low noise levels in bootstrapping keys, additive secret sharing is introduced in the offline phase before bootstrapping. parties within the same group collectively negotiate and generate bootstrapping keys through operations such as addition and multiplication of secret shares.

- 2.

A multi-group hybrid product algorithm is proposed. To parallelize bootstrapping, the core steps of bootstrapping are divided into multiple subtasks by group. Each subtask independently performs blind rotation using the corresponding group bootstrapping key, and the outputs of the subtasks are aggregated using the multi-group hybrid product algorithm.

- 3.

Secure parameter sets are determined and the effectiveness is verified through experiments. Since the FINAL scheme is based on NTRU, "overstretched" parameters render the scheme vulnerable to sublattice attacks. By analyzing the upper bound of noise, the parameters of the proposed scheme are ensured to remain within a secure range using LWE [

22] and NTRU estimators [

23]. Experiments are conducted under two different parameter sets with the number of groups ranging from 2 to 8, validating the effectiveness of the proposed scheme.

2. Related Work

In MGHE, plaintexts within the same group are encrypted using a joint public key in the form of MPHE, while ciphertexts encrypted under joint public keys of different groups are computed in a multi-key manner. Thus, MGHE can be regarded as an extension of MPHE to multi-key scenarios. Current mainstream single-key HE schemes include BGV [

24], BFV [

25], CKKS [

26], and FHEW [

27]/TFHE [

10,

11]. Both MPHE and MKHE schemes are constructed on top of these single-key schemes.

2.1. Multi-Party Homomorphic Encryption Schemes

The earliest MPHE scheme was constructed by Asharov et al. [

28] based on the LWE-based BGV scheme. In this scheme, parties independently generate public keys, broadcast them, and compute the joint public key locally by summing the received public keys from other parties. Similarly, Mouchet et al. [

14] constructed an RLWE-based MPHE on the BFV scheme, which can be easily extended to BGV and CKKS schemes. FHEW/TFHE-type schemes employ two layers of ciphertexts: the first layer is basic LWE ciphertexts, and the second layer is RGSW ciphertexts for homomorphic decryption. Unlike BGV, BFV, and CKKS schemes, TFHE encodes the LWE secret key into the monomial

X and encrypts it into the second-layer ciphertext as the bootstrapping key, achieving homomorphic decryption through the blind rotation algorithm. Thus, constructing a multi-party TFHE scheme requires generating multi-party bootstrapping keys. Lee et al. [

29] realized the generation of multi-party blind rotation keys by leveraging homomorphic multiplication between RGSW ciphertexts, constructing a feasible multi-party bootstrapping algorithm. Subsequently, Park et al. [

30] built the first multi-party TFHE scheme based on this bootstrapping algorithm.

2.2. Multi-Key Homomorphic Encryption Schemes Based on Blind Rotation

As the fastest method for bootstrapping a single ciphertext, blind rotation is not only applicable to TFHE schemes but also compatible with all (R)LWE-based encryption schemes. Thus, blind rotation is a key technology for both MPHE and MKHE schemes. Chen et al. [

18] first extended TFHE to multi-key scenarios, proposing the CCS scheme. This scheme uses the hybrid product between multi-key RLWE ciphertexts and single-key Uni-Enc ciphertexts to replace the external product between multi-key RLWE and multi-key RGSW ciphertexts, achieving lower time and space overhead. Based on the hybrid product algorithm proposed by Chen et al., Kwak et al. [

31] constructed a generalized external product algorithm and designed a parallelizable multi-key LWE ciphertext bootstrapping algorithm (KMS scheme). The initial blind rotation algorithm, which used RLWE and RGSW ciphertexts as inputs, was later improved in the FINAL scheme by Bonte et al. [

12]. Based on the NTRU problem, their key modification was to replace these ciphertexts with the more compact scalar NTRU and vector ciphertexts, respectively. Since NTRU scalar and vector ciphertexts are smaller in size than RLWE and RGSW ciphertexts, and fewer polynomial multiplications are required for their homomorphic multiplication, the overhead of blind rotation is reduced. Building on the FINAL scheme, Xu et al. [

32] proposed an MKHE scheme that achieves approximately 5x speedup compared to the CCS scheme for two parties. However, this scheme controls noise accumulation during homomorphic computations by fixing the Hamming weight of NTRU keys, which Kim et al. [

33] pointed out compromises the scheme’s security, making it unsuitable for practical applications. Park et al. [

34] applied the hybrid product algorithm to the key switching key generation protocol, avoiding the invocation of the hybrid product during blind rotation, resulting in significant performance improvements over the CCS and KMS schemes. Nevertheless, it still does not support parallel execution.

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Notions

Boldface letters denote vectors (e.g., ), and the inner product between two vectors and is denoted as. denotes the ring of integers. For a given positive integer q, denotes the quotient ring , whose elements are integers in the interval . Similarly, given positive integers Q and N (where N is a power of 2), denotes the 2N-th cyclotomic ring, and the quotient ring consists of integer polynomials with coefficients in . indicates that the random variable e is sampled from the distribution . Similarly, denotes that the vector e is obtained by sampling n times independently from . For clarity, if e is a polynomial (even if its coefficients are sampled multiple times from a distribution), the former notation is still used. and denote the standard deviation and variance of a distribution, respectively. For a random variable a, denotes its variance if , or the variance of its coefficients if . For a ciphertext c, denotes the ciphertext noise, and denotes the variance of the ciphertext noise. , , and denote the rounding function, ceiling function, and floor function, respectively. In secret sharing schemes, for a secret s, denotes the secret share belonging to the i-th party, and denotes the set of secret shares.

3.2. Hard Problems

Definition 1. Decisional LWE Problem [35].

Given positive integers q, n and a distribution over , the decisional LWE problem is to distinguish between:

- 1.

Randomly sampled pairs ;

- 2.

Pairs , where is uniformly sampled from , is the i-th element of , is uniformly sampled from , is the i-th element of , and e is sampled from .

Definition 2. Decisional RLWE Problem [36].

Given positive integers Q, N, the polynomial ring , , and a distribution over R, the decisional RLWE problem is to distinguish between:

- 1.

Randomly sampled pairs ;

- 2.

Pairs , where are uniformly sampled from , and e is sampled from .

Definition 3. Decisional NTRU Problem [12].

Given positive integers Q, N, the polynomial ring , , and a distribution over R, let , with f invertible in . The decisional NTRU problem is to distinguish between:

- 1.

A randomly sampled element ;

- 2.

The element .

Definition 4. Decisional Vector NTRU Problem [37].

Given positive integers Q, N, d, the polynomial ring , , and a distribution over R, let with f invertible in . The decisional vector NTRU problem is to distinguish between:

- 1.

A randomly sampled vector ;

- 2.

The vector .

3.3. Gadget Decomposition

Gadget decomposition is a technique for decomposing an integer in

into multiple small integers in

. Given positive integers

B,

, and

, the gadget decomposition vector with base

B is defined as

. The decomposition function of the integer

a with base

B is given by:

where

. For brevity,

is denoted as

. Gadget decomposition is not limited to

but can also be extended to the polynomial ring

. For a polynomial

, it is treated as a coefficient vector, and the above conclusion holds by decomposing each element of the vector individually.

3.4. FINAL Scheme

The NTRU problem serves as a crucial hard problem for constructing post-quantum FHE schemes, and its parameter selection directly impacts the security of the cryptographic scheme. Schemes built on NTRU are vulnerable to sublattice attacks if "overstretched" parameters are used [

38]. To avoid overstretched parameters while ensuring the correctness of homomorphic operations, Bonte et al. proposed the FINAL scheme [

12]. Subsequently, Xiang et al. [

20] modified the ciphertext form of the scheme to construct their ring isomorphism-based blind rotation algorithm. The modified FINAL scheme is described as follows:

FINAL.Setup(): Input a security parameter , generate security-compliant parameters including the NTRU polynomial modulus Q, polynomial degree N, Gadget decomposition base B, key distribution over R, and noise distribution over R. Output .

FINAL.KeyGen(): Input the parameters generated by the Setup algorithm, select an invertible polynomial from , and output the NTRU key f.

FINAL.ScalarEnc(

m,

f): Input a plaintext

and the NTRU key

f, randomly select noise

, set

as the scaling factor, and output the NTRU scalar ciphertext

FINAL.VectorEnc(

m,

f): Input a plaintext

and the NTRU key

f, randomly select noise

where

, and output the NTRU vector ciphertext

To implement the CMux gate, the TFHE scheme defines the external product between TRLWE and TRGSW ciphertexts. Similarly, the FINAL scheme defines the external product between scalar NTRU and vector NTRU ciphertexts, and proves the upper bound of the noise variance for this external product operation.

Definition 5. NTRU External Product

Let

denote a scalar NTRU ciphertext encrypting the plaintext

m with modulus

Q, scaling factor

, and NTRU key

f. Let

denote a vector NTRU ciphertext encrypting the plaintext

m with modulus

Q, Gadget decomposition base

B, and NTRU key

f. The external product is defined as

where

Lemma 1. Noise of NTRU External Product

Given positive integers

Q,

N,

B,

d, a scalar NTRU ciphertext

, and a vector NTRU ciphertext

, let

and

denote the noise of

c and

, respectively, and

and

denote their noise variances. Then, the noise variance of the ciphertext

satisfies

3.5. XZD Blind Rotation

The first automorphism-based blind rotation algorithm was proposed by Lee et al. [

29] (LMKC scheme). Unlike the AP scheme [

39], which achieves exponent accumulation through multiplication operations, the LMKC scheme leverages the automorphism map

to implement scalar multiplication on exponents, thereby significantly reducing the number of multiplication operations in the accumulator. Subsequently, the XZD scheme proposed by Xiang et al. [

20] further shortens the time required for key switching after multiplication in the accumulator by adopting scalar and vector NTRU ciphertexts, effectively reducing the overall computational overhead of blind rotation.

The order of the monomial

X over the 2N-th cyclotomic polynomial ring

is 2N, i.e.,

. Thus, for a positive integer

t, multiplying any element

by the monomial

results in a regular cyclic left or right shift of the polynomial’s coefficients. Blind rotation leverages this property to rotate specific coefficients to the leading term. Formally, given an element

, compute the rotation polynomial

For a ciphertext

satisfying

(where

is the LWE scaling factor,

q is the LWE ciphertext modulus, and

q divides 2N), the goal of blind rotation is to compute the following in the encrypted state

Before performing blind rotation, the XZD scheme preprocesses the ciphertext to be bootstrapped

by computing

ensuring the existence of the automorphism. Subsequently, the rotation polynomial is encrypted into a scalar NTRU ciphertext, and the monomial

(related to the

i-th component of the LWE secret key) is encrypted into a vector NTRU ciphertext. During blind rotation,

is iteratively multiplied into the rotation polynomial via the external product between the two types of ciphertexts, followed by key switching based on automorphism to multiply the ciphertext component

into the rotation polynomial.

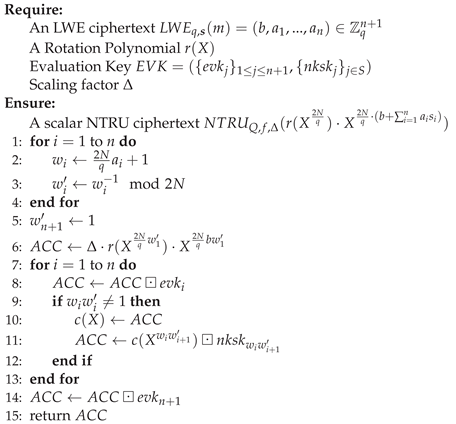

The XZD blind rotation consists of two algorithms: the Blind Rotation Key Generation (BRKGen) algorithm and the Blind Rotation Evaluation (BREval) algorithm. Let be the public parameters output by , and . Define the set , and let denote the LWE ciphertext encrypting the plaintext m with modulus q and secret key . The two algorithms are described as follows.

-

BRKGen(): Given an LWE secret key and an NTRU key , the algorithm outputs , where

- 1.

, for , ,

- 2.

.

BREval(

): Input an LWE ciphertext

, a rotation polynomial

r, the evaluation key

generated by BRKGen, and the NTRU scaling factor

. The algorithm computes and outputs

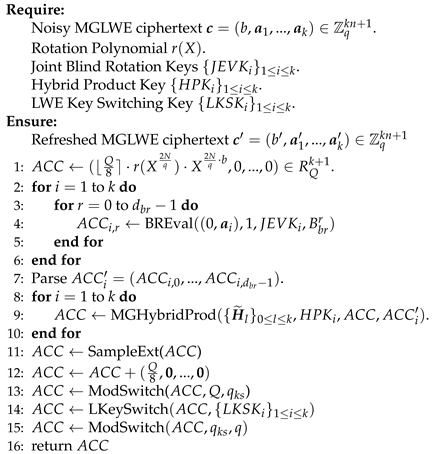

The detailed steps are presented in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1 BREval( (adapted from [20]). |

|

3.6. Additive-Only Multi-Party RLWE-Based Homomorphic Encryption

The core algorithms of the multi-party BFV scheme proposed by Mouchet et al. [

40] can be combined to form an additive-only (supporting scalar multiplication) multi-party RLWE homomorphic encryption scheme (AHE).

AHE.Setup(): Input a security parameter , output security-compliant public parameters including the RLWE ciphertext modulus Q, plaintext modulus t, polynomial degree N, secret key distribution over R, noise distribution over R, and a common reference polynomial . Output .

AHE.SKeyGen(): Each party selects an RLWE secret key .

AHE.PKeyGen(): Each party selects noise , computes , and sets .

AHE.JointPKeyGen(): Input the public keys of all parties, compute , and output the joint RLWE public key .

AHE.Enc(m): Input a plaintext , select noise , , randomly select a temporary secret polynomial , compute and , and output the ciphertext .

AHE.Dec(): Input a ciphertext encrypted under the joint RLWE public key and the RLWE secret keys of all parties, compute .

AHE.Add(): Input two multi-party RLWE ciphertexts and encrypting plaintexts under the same public key, compute and output .

AHE.ScalarMult(): Input a scalar polynomial and a multi-party RLWE ciphertext , compute and output .

4. Basic Multi-Group LWE-Based Homomorphic Encryption without Bootstrapping

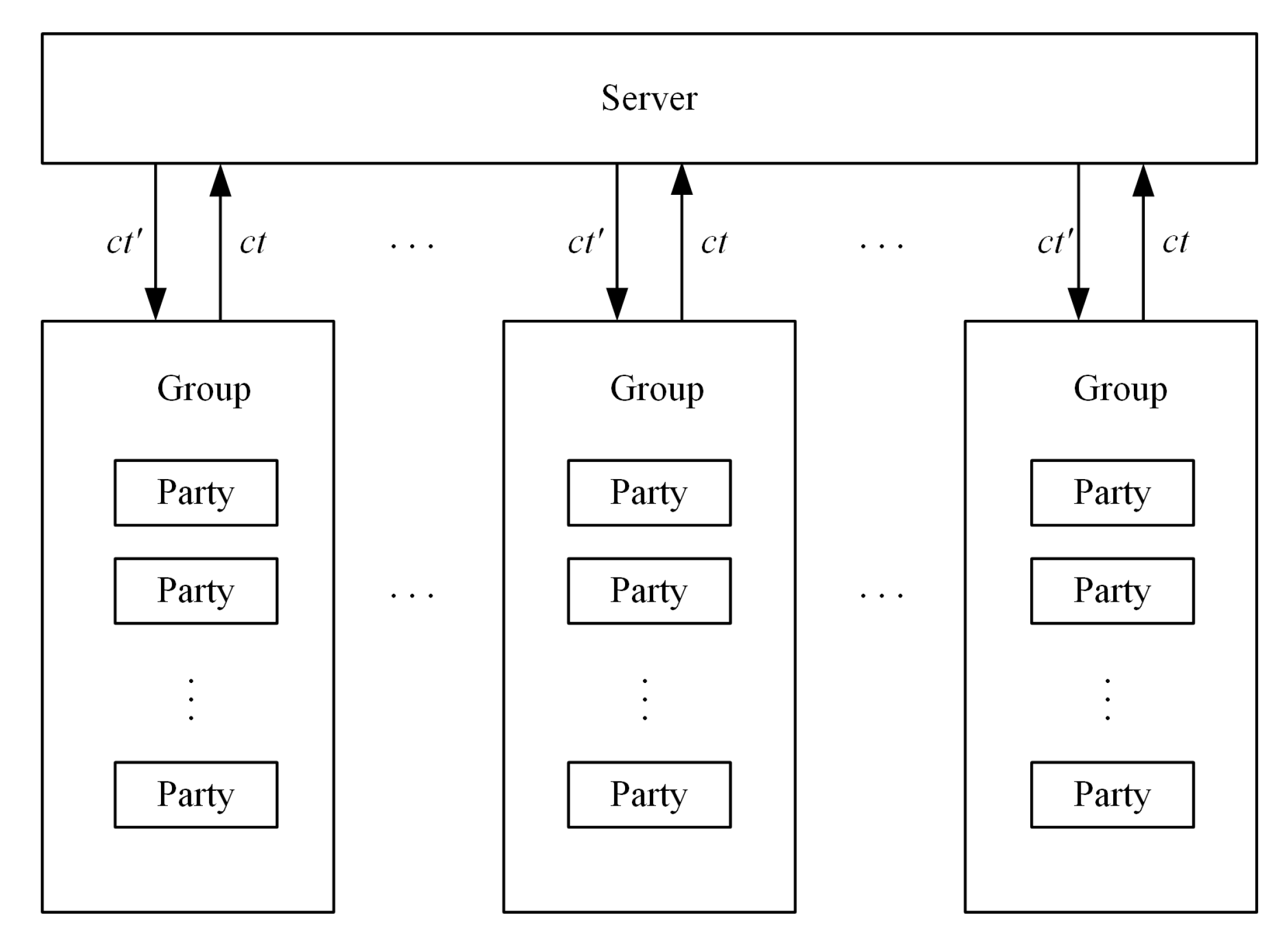

This section first introduces the basic LWE-based multi-group homomorphic encryption scheme, whose network architecture is shown in

Figure 1.

Parties in each group encrypt plaintexts using the group joint public key to obtain ciphertexts , which are then sent to the server. After receiving the ciphertexts, the server performs homomorphic computation and bootstrapping, and returns the new ciphertext to be decrypted. Under the MGHE framework, our basic scheme includes two sets of algorithms: SKeyGen, PKeyGen, JointPKeyGen and Enc, which are dedicated to intra-group interactive computation, as well as Setup, NAND and Dec, which are for inter-group computation. In addition, to support asymmetric encryption while maintaining a small ciphertext modulus, we distinguish between the encryption modulus and the bootstrapping modulus q. The encryption modulus is much larger than q, and ciphertexts under the encryption modulus can tolerate greater noise. After encrypting a plaintext, a party needs to switch the ciphertext modulus to the bootstrapping modulus q through the ModulusSwitch algorithm to perform subsequent NAND and bootstrapping algorithms.

Let be a set of parties, denote the i-th group, j be the unique index of the party in the i-th group within , and denote the j-th party in the i-th group. Our MGHE includes the following algorithms.

MGHE.Setup(): Takes a security parameter as input, generates global parameters meeting security requirements, including LWE encryption modulus , LWE bootstrapping modulus q, LWE dimension n, LWE secret key distribution over , noise distribution over , and a common reference matrix . Outputs .

MGHE.SKeyGen(): Parties in each group independently generate a private LWE secert key , and output the LWE secret key .

MGHE.PKeyGen(): Party selects noise , computes , and sets .

MGHE.JointPKeyGen(): Takes the LWE public keys of each party in a group , computes , and outputs the LWE joint public key .

MGHE.Enc(): Takes a plaintext bit and the LWE joint public key of a group as input, randomly selects a temporary secret vector , noise , , computes , , and outputs the LWE ciphertext encrypting the plaintext m under the joint LWE public key .

MGHE.ModulusSwitch(): Takes the LWE ciphertext generated by the MGHE.Enc algorithm and the LWE bootstrapping modulus q for bootstrapping, computes and outputs .

MGHE.Dec(): Takes the multi-group LWE ciphertext and the LWE secret keys of each party in each group as input, computes and outputs .

MGHE.NAND(): Takes two multi-group LWE ciphertexts and encrypted under the same set of public keys , which encrypt plaintext bits respectively. For , let and , computes , and outputs the ciphertext encrypting the plaintext m NAND .

RLWE is a ring variant of LWE. The above multi-group homomorphic encryption scheme can be constructed based on RLWE. Since the RLWE-based multi-group scheme operates on the ring , the main difference between the RLWE-based multi-group homomorphic encryption scheme and the above LWE-based scheme lies in the encryption and decryption algorithms. Let the RLWE joint public key be . In the encryption algorithm, we compute and , where is a secret polynomial, and , are selected from a distribution over a certain polynomial ring. We denote as the multi-group RLWE ciphertext encrypted by the RLWE joint public keys of k groups, with the corresponding secret keys . The ciphertext satisfies , where is a scaling factor.

The encryption scheme in this paper is based on Boolean circuits. Since the NAND gate has functional completeness, we can use the NAND gate as the basic unit to construct any Boolean function. Since homomorphic computation is performed under the circuit model, the bootstrapping scheme introduced in this paper belongs to gate bootstrapping. That is, homomorphic decryption is performed immediately after computing a NAND gate, and the scaling factor is converted from

to

to support the next homomorphic NAND computation. After multiple gate bootstrapping operations, the decryption algorithm MGHE.Dec requires each party in each group to execute an interactive protocol called "distributed decryption" to ensure the security of the joint key. The current mainstream implementation is based on the smudging lemma in the AJL scheme [

28]. Each party samples an super-polynomially large smudging noise

from a large noise distribution, computes

and broadcasts it to mask the intermediate results during the decryption process. To ensure the correctness of decryption, the ciphertext modulus also needs to be set very large. However, in our multi-group ciphertext bootstrapping algorithm based on NTRU and LWE, since the NTRU ciphertext modulus

Q cannot be super-polynomially large, this method is not applicable.

For such schemes with limited ciphertext modulus, the KLO scheme proposed by Kraitsberg et al. [

41] constructs a secure three-party distributed decryption protocol using garbled circuits, and the scheme can be extended to more parties. Although this decryption protocol requires additional communication overhead, no additional noise needs to be introduced, so the parameters of the encryption scheme do not need to be adjusted.

5. Bootstrapping for Multi-Group LWE Ciphertext

This section introduces how to bootstrap multi-group LWE ciphertexts. Bootstrapping can be divided into two parts: bootstrapping key generation and bootstrapping execution. The generation of the bootstrapping key uses additive secret sharing technology to compute the bootstrapping key related to the joint NTRU key . In addition, in additive secret sharing, the secret can be recovered by simply summing the secret shares held by each party. Therefore, we can design a multi-group hybrid product algorithm suitable for multi-group ciphertexts to realize the multiplication between different types of ciphertexts, and further construct a parallelizable bootstrapping algorithm.

5.1. Generating Polynomial Multiplication Triples

The multiplication triple

was proposed by Beaver [

42] to reduce the number of communication rounds in secret sharing multiplication, thereby converting communication overhead into precomputation overhead in the offline phase. Existing multiplication triple generation schemes mainly include the MASCOT scheme [

43] based on Oblivious Transfer (OT) and the Low/High Gear scheme [

44] based on Additive-only Homomorphic Encryption (AHE). However, the triple elements generated by these schemes are all values over the integer ring (field), which cannot be used for secret multiplication over the polynomial ring

. Therefore, we design a multi-party multiplication triple generation algorithm TripleGen that supports polynomial secret multiplication according to the framework proposed in [

45]. The algorithm comprises two sub-algorithms: the Setup sub-algorithm is used to initialize public parameters, and the EvalGen is used to generate triples.

TripleGen.Setup(): Successively executes AHE.Setup, AHE.SKeyGen, AHE.PKeyGen, and AHE.JointPKeyGen, outputs public parameters , secret keys of each party, and joint public key .

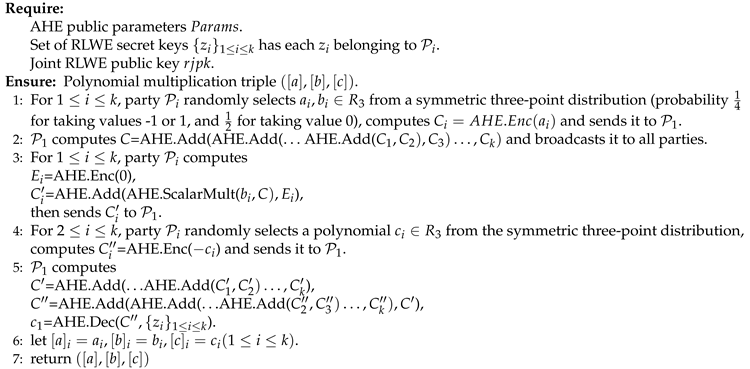

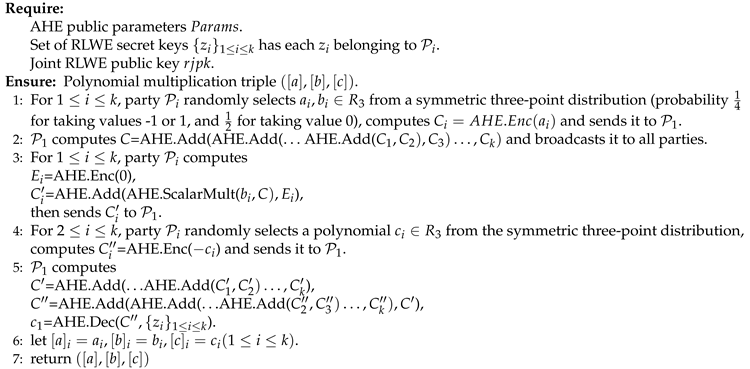

TripleGen.EvalGen(): Takes the public parameters output by TripleGen.Setup, the secret keys of each party, and the joint public key as input, and outputs a random polynomial multiplication triple. The detailed specifications referred to Algorithm 2.

|

Algorithm 2 TripleGen(). |

|

When performing decryption in the fifth step, we also need to use a distributed decryption protocol. The difference is that party does not need to broadcast its partial decryption result, while other parties need to send their partial decryption results to . This asymmetric decryption method ensures that no party other than knows the decryption result.

Let the secrets corresponding to the triple shares output by the algorithm be . Since we need to hold over the ring , the plaintext modulus t of AHE is required to be larger than the coefficients of c to ensure that the c output by the algorithm is not implicitly modulo t.

In the second step of the algorithm, party broadcasts the ciphertext C, which encrypts , and the upper bound of its plaintext coefficients is k. In the third step, each party computes the ciphertext , which encrypts the plaintext , with the upper bound of coefficients being . Similarly, the ciphertext in the fifth step encrypts , with the upper bound of plaintext coefficients being . The ciphertext encrypts , with the upper bound of its coefficients being . Therefore, to ensure correctness, it is required that .

5.2. Additive Secret Sharing over Polynomial Ring

In additive secret sharing, a secret dealer splits a secret into

k secret shares and distributes them to

k parties

. To reconstruct the secret, it is only necessary to simply sum the secret shares of each party. It should be noted that the secret cannot be reconstructed with fewer than

k secret shares. The classic additive secret sharing is defined over the integer ring (field) [

46], and we extend it to the polynomial ring

. Since the secret shares are elements over the polynomial ring, we add an automorphism algorithm. Therefore, additive secret sharing over polynomial rings has a total of 6 algorithms (all operations are implicitly performed over the polynomial ring

), as follows.

ASS.Split(s): Takes a secret belonging to as input. For , party randomly selects elements in , computes , and distributes the secret share of the secret s to party .

ASS.Recover(): Each party broadcasts the share of the secret s. After collecting sent by the other parties, computes .

ASS.Add(): Takes the secret shares of secrets x and y as input. For , party locally computes , and outputs the secret shares of the secret .

ASS.ScalarMult(): Takes the secret shares of the secret x and a polynomial as input. For , party locally computes , and obtains the secret shares of the secret .

ASS.Mult(): Takes the secret shares , of secrets x and y, and the secret shares , , of the multiplication triple as input. Each party locally computes , and broadcasts them. After receiving the broadcasts from other parties, party locally recovers the secrets and . For , locally computes ; for other parties , locally computes .

ASS.Auto(): Takes the secret shares of the secret x and an automorphism as input. For , party locally computes , and obtains the secret shares of the secret .

In the same computation task, the multiplication triple input to the ASS.Mult algorithm cannot be reused; otherwise, other parties can infer the corresponding secret. For brevity, the parameter passed to ASS.Mult in the following is a set of triple slices, and the used triple is discarded after each call to secret multiplication. Meanwhile, if the number of parties k is already clear in the following, we will use instead of to denote the secret shares of the secret x.

5.3. Multi-Group Hybrid Product

The hybrid product algorithm was proposed by Chen et al. [

18] in the MK-TFHE scheme in 2019 to support the product between multi-key RLWE ciphertexts and single-key Uni-Enc ciphertexts for constructing CMux gates in the multi-key scenario. Subsequently, Kwak [

31] generalized it to support the multiplication of single-key RLEV ciphertexts and multi-key RLWE ciphertexts, thereby realizing the parallelization of blind rotation. In our parallelized bootstrapping scheme, since the intermediate ciphertext of bootstrapping is a single-group NTRU ciphertext rather than a single-key RLEV ciphertext, we propose a multi-group hybrid product algorithm to support the parallelization of bootstrapping, which includes the hybrid product key generation(MGHPKeyGen) , as well as the hybrid product(MGHybridProd) that takes scalar NTRU ciphertexts and multiple sets of ciphertexts as inputs.

-

MGHPKeyGen(

): Takes the RLWE secret key

of the

j-th party

in group

G and the secret share

of the joint NTRU key

F as input, randomly selects a common reference polynomial vector

, each party selects a secret polynomial

from the noise distribution over the ring

R and noise polynomial vectors

. Denote

and

as the decomposition base and decomposition degree of the ciphertext modulus

Q respectively, and

as the corresponding decomposition vector. For

, compute

Then output .

-

MGHybridProd(

): Takes the MGRLWE public keys

, the

output by the

i-th group after executing MGHPKeyGen, the multi-group RLWE ciphertext

encrypting the plaintext

m, and the vector NTRU ciphertext

encrypting the plaintext

as input. For

, let

, where

is the polynomial vector shared by multiple groups in MGHPKeyGen, computes

then update

Outputs the multi-group RLWE ciphertext encrypting the plaintext .

5.4. Other Core algorithms for Bootstrapping

This subsection introduces other core algorithms for multi-group ciphertext bootstrapping, including the group registration algorithm Enroll for generating auxiliary material of the bootstrapping key, the JBRKGen algorithm for generating the joint bootstrapping key, the sample extraction algorithm SampleExt for extracting multi-group LWE ciphertexts from multi-group RLWE ciphertexts, the ModSwitch algorithm for switching the modulus of multi-group LWE ciphertexts, the algorithm LKSKeyGen for generating LWE key switching keys, and the LKeySwitch algorithm for switching LWE ciphertext keys.

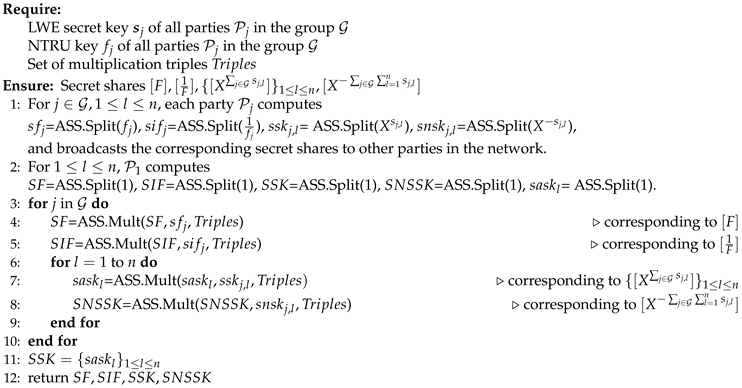

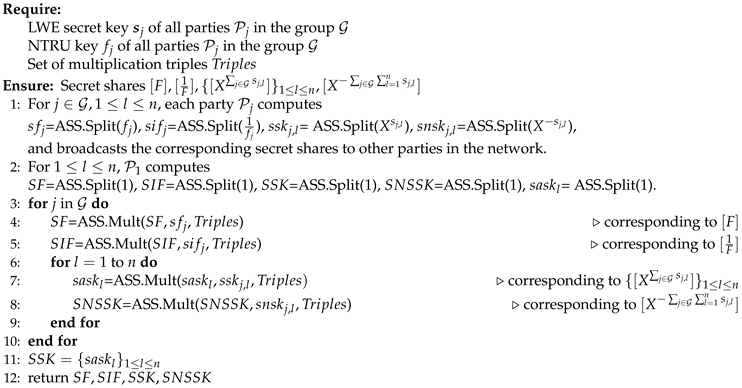

Enroll(): Takes the LWE secret key and its corresponding NTRU key of each party in a group as input, and outputs , which respectively denote the secret share of the joint NTRU key F, the secret share of (multiplicative inverse of F), the secret share of the secret key, and the secret share of the negative sum secret keys. The algorithm is presented as shown in Algorithm 3.

|

Algorithm 3:. |

|

The secret shares , ,, are key information for generating the evaluation key in the XZD scheme. After obtaining the share sets of these four components, we can easily generate the joint bootstrapping key(multi-group version of ) in the multi-group scenario using additive secret sharing.

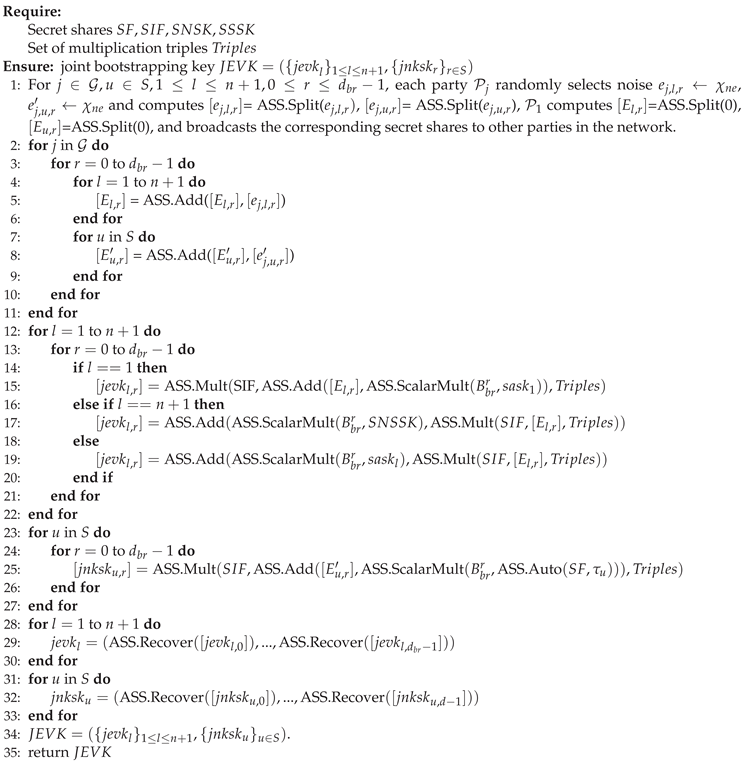

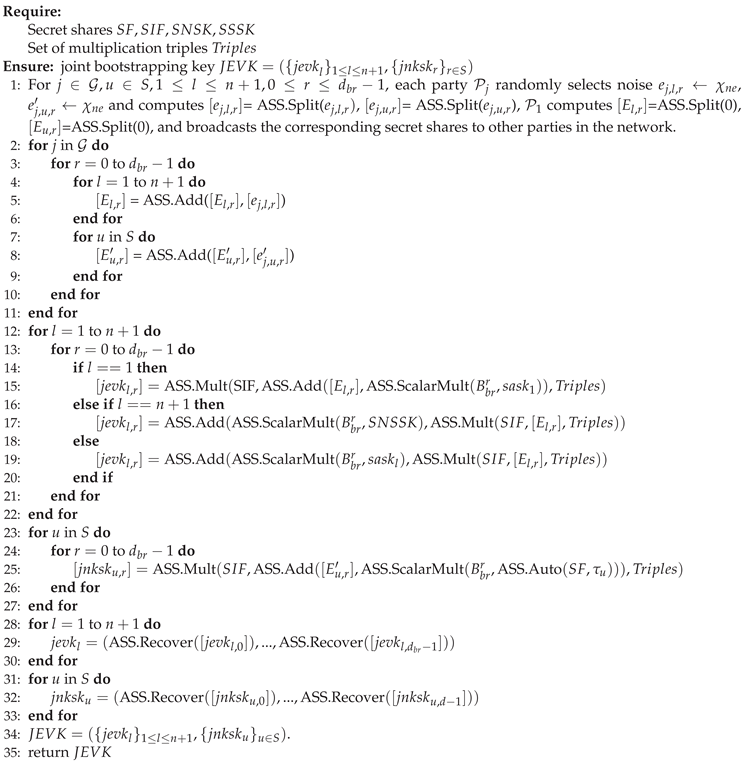

JBRKGen(): Takes , , , output by the Enroll algorithm and a set of multiplication triples as input, outputs the joint bootstrapping key . The details are as shown in Algorithm 4.

|

Algorithm 4 JBRKGen(). |

|

The above algorithm generates multi-group version of the in the XZD scheme via additive secret sharing; specifically, it implements the encryption algorithm in the FINAL scheme using various algorithms under the framework of additive secret sharing, and completes the encryption of the relevant keys in accordance with the flow of BRKGen algorithm in the XZD scheme.

SampleExt(): Takes the MGRLWE ciphertext as input, denotes as the j-th coefficient of the polynomial , sets and for , and outputs .

ModSwitch(): Takes the MGLWE ciphertext , the original modulus Q and the new modulus q as input, computes and for , and outputs the new ciphertext .

LKSKeyGen(): Takes the LWE secret keys and of party in the group as input, randomly selects a matrix within the group, randomly samples the noise for , computes , denotes , and outputs .

LKeySwitch(): Takes the MGLWE ciphertext as well as the key switching key for the i-th group as input, denotes for , computes , , and outputs .

5.5. Parallelizable Multi-Group Ciphertext Bootstrapping Algorithm

In this subsection, we formally describe the multi-group LWE ciphertext bootstrapping algorithm based on LWE and NTRU proposed in this paper. The algorithm takes a multi-group LWE ciphertext to be bootstrapped and some precomputed bootstrapping materials as inputs, and outputs a multi-group LWE ciphertext with a lower noise that encrypts the same plaintext.

In the proposed multi-group homomorphic encryption scheme, bootstrapping involves three types of keys: LWE secret keys, RLWE secert keys, and NTRU keys. For and , let , denote the LWE secret key, RLWE secret key, and NTRU key of , respectively. Let Q, , and q denote the ciphertext modulus of NTRU/MGRLWE, the LWE key switching modulus, and the LWE bootstrapping modulus, respectively, with . We define the following precomputed materials.

- 1.

Set of multiplication triples: TripleGen.

- 2.

-

Secret shares generated by Enroll algorithm of parties in group :

Enroll.

- 3.

Joint bootstrapping key of group : JBRKGen.

- 4.

Multi-group hybrid product key of group : MGHPKeyGen.

- 5.

LWE key switching key of group : LKSKeyGen.

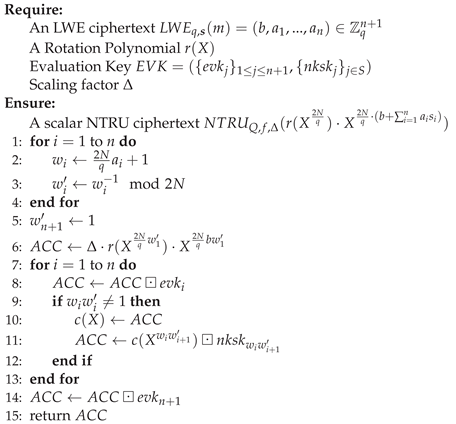

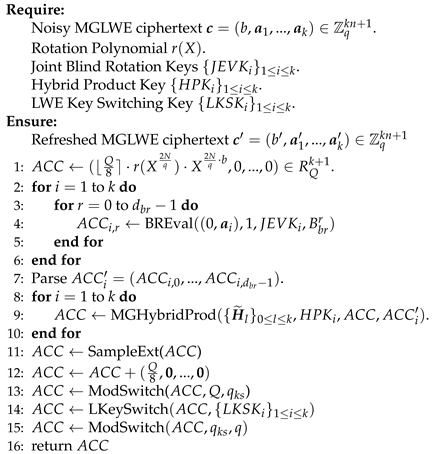

We define the multi-group ciphertext bootstrapping algorithm BootMGCT in Algorithm 5.

|

Algorithm 5. |

|

Line 1 of the algorithm stores the rotation polynomial into the accumulator (). Lines 3 to 5 compute the ciphertext . These two values are taken as inputs to perform k rounds of iteration(MGHybridProd), outputting the multi-group RLWE (MGRLWE) ciphertext encrypted under the joint RLWE public key of each group, wherein the ciphertext encrypt the value of . The exponent part of the monomial corresponds to the decryption formula of MGLWE ciphertexts. The SampleExt algorithm in Line 11 outputs the LWE ciphertext that encrypts the first coefficient of under the encryption of the RLWE secret key coefficient vector. Since its first coefficient is either -1 or 1, Step 12 accumulates into ACC, mapping its value to either 0 or 1. After the subsequent steps of the algorithm, a low-noise MGLWE ciphertext with as the scaling factor is output.

6. Noise Analysis

This section analyzes the noise generated by the proposed bootstrapping algorithm. For an input multi-group LWE ciphertext , the noise of the output ciphertext originates from BREval, MGHybridProd, ModSwitch, and LKeySwitch. We analyze the noise output by each of these algorithms separately, and finally derive the total noise output by the bootstrapping algorithm.

The LWE scheme has parameters , q, , , , n, which correspond to the LWE ciphertext modulus of MGHE.Enc, the LWE ciphertext modulus for bootstrapping, the ciphertext modulus for key switching, the gadget decomposition base, the gadget decomposition degree, and the LWE dimension, respectively. The RLWE/NTRU scheme has parameters Q, , , N, which correspond to the RLWE/NTRU ciphertext modulus, the corresponding gadget decomposition base, the gadget decomposition degree, and the degree of the polynomial in the RLWE/NTRU ciphertext, respectively. Two bootstrapping schemes are involved in the bootstrapping process: LWE and RLWE/NTRU, with noise distributions and (corresponding variances and ) and key distributions and (corresponding variances and ), respectively. For the convenience of analysis, we assume that there are k groups participating in the computation, and each group has K parties.

Lemma 2. Noise Variance of BREval [20]

Let

denote the noise variance of the input

,

. For the ciphertext

c output by the BREval algorithm, the noise variance of

c satisfies

Proof. The BREval algorithm performs at most external products between scalar NTRU ciphertexts and vector NTRU ciphertexts. The rotation polynomial can be regarded as a vector NTRU ciphertext with zero noise. Hence, we complete the proof via Lemma 1.

Lemma 3. Noise Variance of MGHybridProd

Given a multi-group RLWE ciphertext

c with noise variance

, the noise

of the ciphertext

output by the MGHybridProd algorithm satisfies

Proof. Assume that the noise variance of the multi-group RLWE ciphertext

c encrypting the plaintext

m before MGHybridProd is

, and the noise variance of the ciphertext

encrypting the plaintext

after MGHybridProd is

. Let

Z denote the group joint RLWE secret key, and

R,

E denote the sums of

r and

e defined in the algorithm, respectively. According to the MGHybridProd algorithm, the noise

of the new ciphertext satisfies

Given that is a monomial with an absolute coefficient value of 1, the variance of the first term is . Since , it follows from Lemma 1 that . As and is the sum of the RLWE secret keys held by K parties, we can derive that . Accordingly, the variance corresponding to the second term in the noise expression is . On the other hand, and are both accumulations of random variables independently selected by K parties, which means their variances are and , respectively. Based on this, the variance of the third term in the expression can be expressed as . Similarly, the variance of the fourth term is given by , and the variance of the last term is . By integrating and rearranging all the aforementioned variance terms, the lemma is thus proved. □

Lemma 4. Noise Variance of ModSwitch

Given positive integers

Q,

q, a multi-group LWE ciphertext

with noise variance

, and the corresponding joint LWE secret key

, a new ciphertext

is obtained after modulus switching. The noise

of the new ciphertext satisfies

Proof. Consider an original ciphertext with modulus q, LWE dimension n, and secret keys of each party in each group, which needs to be switched to modulus Q. After modulus switching, , where . Here, denotes the rounding error, which follows a uniform distribution over . The noise satisfies , thus . □

Lemma 5. Noise Variance of LKeySwitch

Given a multi-group LWE ciphertext

with LWE dimension

N encrypted under

k joint RLWE secret key coefficient vectors

, the LWE key switching algorithm outputs a multi-group LWE ciphertext

with LWE dimension

n encrypted under

k LWE joint secret keys

. The noise variance of the new ciphertext

satisfies

Proof. The components of the joint LWE secret key corresponding to the ciphertext

output by the LKeySwitch algorithm are denoted by

. The corresponding noise

satisfies

Since the variance of is , it follows that .

Theorem 1. Noise Variance of the Multi-Key Bootstrapping Algorithm

Given a ciphertext

to be bootstrapped with noise variance

, a rotation polynomial

r, joint bootstrapping keys

, hybrid product keys

, and LWE key switching keys

, the noise variance of the new ciphertext output by the BootMGCT algorithm, denoted as

, satisfies

Proof. According to Lemma 2, the noise variance of input to MGHybridProd is , denoted as . Before entering the i-th loop in Line 9 of the algorithm, the last terms of the multi-group RLWE ciphertext stored in ACC are all zero, so no noise accumulates. According to Lemma 3, after executing the MGHybridProd loop in Line 9, the noise variance of the ciphertext is . According to Lemma 4, after the modulus switching in Line 12, the noise variance of the ciphertext is . According to Lemma 5, after the LWE key switching in Line 13, the noise variance of the ciphertext is . Similar to the first modulus switching, the noise after the second modulus switching in Line 14 of the algorithm is . The theorem is proved by combining the above results.

□

7. Parameters and Implementation

7.1. Security Model and Security Analysis

The proposed scheme is divided into an offline phase and an online phase. The offline phase refers to the key generation phase, which is distinguished from the online phase of computing the target function. Since the security of the online phase has been proven in [

20,

31], we focus on the security proof of the offline phase.

Under the semi-honest adversary model, the additive secret sharing (ASS) over the polynomial ring

ensures secret confidentiality through strict share randomness and operational security. In the secret splitting phase (ASS.Split), a secret

is split into

k shares, where

shares are uniformly randomly selected from

, and only the remaining 1 share is determined by the difference between the secret and other shares. This ensures that any subset of shares from fewer than

k parties contains no valid information about the secret, and the adversary cannot infer the secret from the subset of shares. Secret addition (ASS.Add), scalar multiplication (ASS.ScalarMult), and automorphism (ASS.Auto) are all completed through local computations by parties, and new secret shares can be generated without interaction, avoiding the leakage of intermediate information. Secret multiplication (ASS.Mult) relies on Beaver multiplication triple

, as long as the same triple is not reused, the adversary cannot obtain the original secret through intermediate differences [

42]. The security of the triple generation protocol directly depends on the RLWE-based additive homomorphic encryption (AHE) scheme, and the security of AHE is based on the computational hardness of the decisional RLWE problem. Thus, semi-honest adversaries cannot obtain secrets from the triple generation process.

Additive secret sharing is used in the Enroll algorithm, JBRKGen algorithm, and MGHPKeyGen algorithm. The Enroll algorithm does not involve secret reconstruction, so the security of the Enroll algorithm is equivalent to that of additive secret sharing. The JBRKGen and MGHPKeyGen algorithms need to obtain vector NTRU ciphertexts and RLWE ciphertexts through secret reconstruction, without directly leaking key information.

In summary, the offline phase of the proposed scheme can guarantee privacy under the semi-honest adversary model. The semantic security (IND-CPA) of the online phase can be directly derived based on the decisional LWE/RLWE problem, decisional NTRU problem, and decisional vectorized NTRU problem through conventional security reduction methods.

7.2. Parameter Selection

We consider the parameter selection of the multi-group homomorphic encryption scheme from two dimensions: usability and security. Usability means that the set parameters must ensure that the noise size of the ciphertext is always within a specified range to maintain the correctness of the decryption process. Security means that the parameter configuration should be able to resist common attack algorithms, making it impossible for attackers to successfully crack the scheme within the scope of computational feasibility.

According to Lemma 7 of the FHEW scheme [

27], for two LWE ciphertexts

,

encrypting plaintexts

with noises

respectively, after performing the homomorphic NAND operation, the noise

of the new ciphertext

satisfies

. At this time, the scaling factor corresponding to the ciphertext is

, so the absolute value of the noise

needs to satisfy

, i.e.,

. Therefore, the sum of the noises of the two ciphertexts undergoing the homomorphic NAND gate needs to satisfy

. In gate bootstrapping, we need to control the upper noise bound of the two input ciphertexts, i.e., the upper noise bound of each ciphertext after bootstrapping needs to be lower than

. To ensure the correctness of decryption, the upper noise bound of each step in the bootstrapping algorithm is also required not to exceed the threshold

, where

is the ciphertext modulus of the current ciphertext. We use 6 times the standard deviation as the high-probability upper bound of the noise. Based on the noise variances of ciphertexts at different stages listed in the noise analysis, we obtain the constraints

which serve as one of the bases for parameter selection. The LWE secret key distribution is a symmetric three-point distribution over

, where the probability of taking values -1 and 1 is

, and the probability of taking value 0 is

. The noise of the LWE scheme is sampled from a discrete Gaussian distribution with the mean of 0 and the standard deviation of 3. For the keys and noises of the NTRU and RLWE schemes, we also use the above two distributions respectively. Sampling a polynomial means sequentially sampling coefficients from the distribution, so

.

From the noise analysis, the noise level of NTRU ciphertexts reaches its peak after executing the MGHybridProd operation. At this time, the NTRU modulus Q satisfies

. From the perspective of the asymptotic complexity of noise, the parameter selection of this scheme can theoretically ensure that it is within a safe range. Therefore, we can use the NTRU estimator [

23] to evaluate the security strength of the NTRU parameters. Similarly, we use the LWE estimator [

22] for parameter selection of the (R)LWE scheme.

Table 1 and

Table 2 show the parameter sets for 100-bit security and 128-bit security, respectively.

7.3. Experimental Results

All experiments are conducted on a server equipped with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8481C processor (3.8GHz) and 64GB of memory, with the operating system Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS. The algorithms proposed in this paper are implemented based on the OpenFHE open-source library.

Table 3 and

Table 4 show the execution time required for the proposed algorithm to perform a homomorphic NAND gate computation under different parameter sets (I, II, III and I’, II’, III’), respectively.

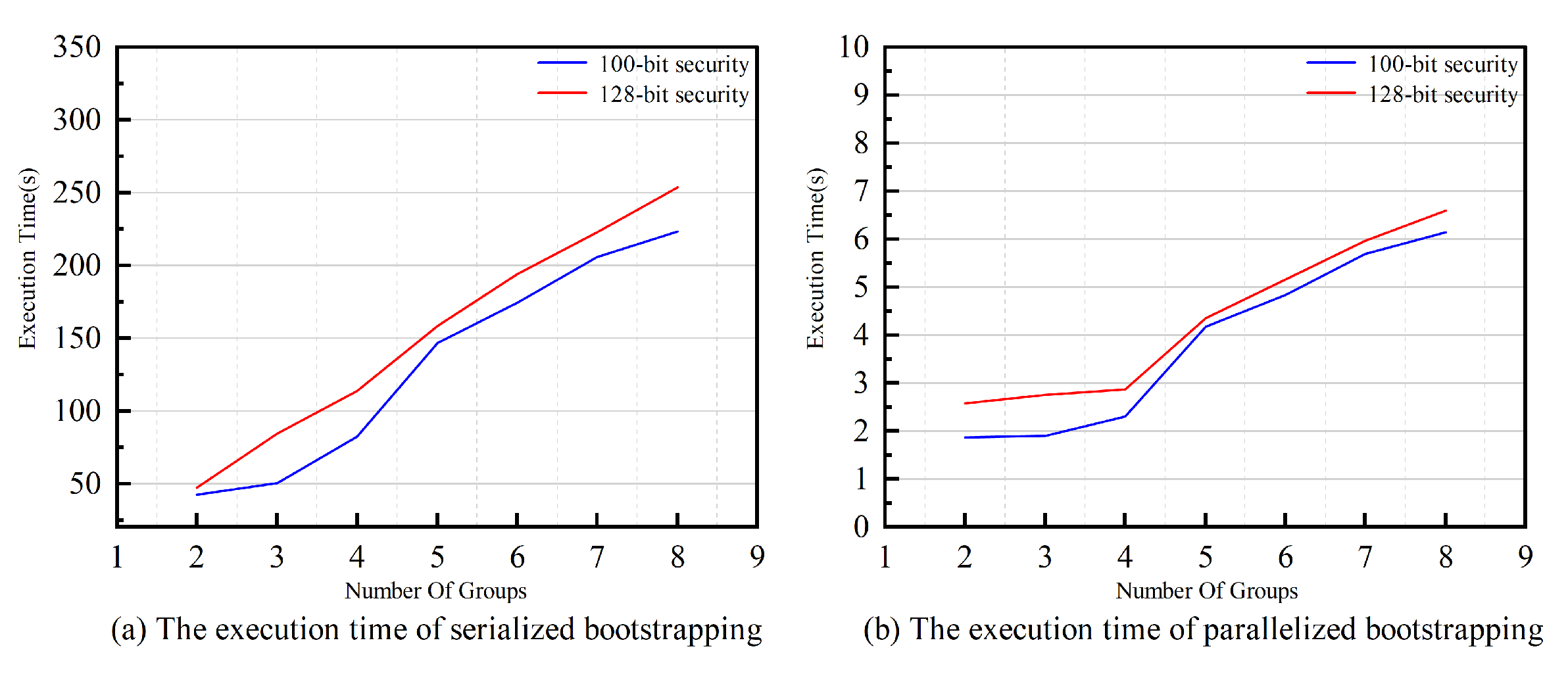

As illustrated in the BootMGCT algorithm, the number of intra-group parties does not affect the number of homomorphic computations required for ciphertext bootstrapping. The algorithm needs to execute the BREval algorithm

times. Under the same parameter set, the time for serialized bootstrapping increases with the number of groups, which can be verified by the data in

Table 3 and

Table 4. When

, the time for a single bootstrapping operation exceeds 200 seconds. This indicates that under constrained parameter selection (the ratio of

Q to

N cannot be excessively large, so

needs to be increased to reduce noise), serialized bootstrapping of multi-group ciphertexts based on NTRU is infeasible. In contrast, if the bootstrapping algorithm is executed in parallel, the bootstrapping time will be significantly reduced.

Figure 2 intuitively illustrates the variation trend of bootstrapping time. When bootstrapping is performed in parallel, for both parameters for 100-bit security and 128-bit security, the bootstrapping time can be controlled within 10 seconds when the number of groups is less than 8. This result shows that by fully leveraging the parallel computing resources of the server, the proposed scheme can achieve bootstrapping efficiency close to that of single-key ciphertexts, greatly enhancing the practicality in multi-group scenarios.

8. Conclusions

This paper proposes a novel multi-group homomorphic encryption scheme based on LWE and NTRU. By linearizing the NTRU joint key through additive secret sharing technology, the scheme designs a multi-group hybrid product algorithm, enabling parallel bootstrapping of multi-group LWE ciphertexts for encrypted bits. In a multi-core server environment, the time cost of bootstrapping a multi-group ciphertext is comparable to that of bootstrapping a single-key ciphertext, significantly improving the practicality of the homomorphic encryption scheme. Additionally, specific parameter selections are provided to ensure the scheme can effectively resist sublattice attacks. Finally, the scheme is implemented on OpenFHE, and its effectiveness is verified. Experimental results show that under the 100-bit security, refreshing a collaborative computing ciphertext involving 50 parties (divided into 2 groups with 25 parties each) only takes less than 2 seconds. Therefore, this scheme provides a new solution for application scenarios requiring group-based computing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and F.K.; software, Y.L.; validation, F.K.; formal analysis, B.H.; data curation, J.W. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, B.H.; visualization, J.W. and S.L.; supervision, B.H.; funding acquisition, J.W., S.L. and B.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Open Project Program of Guangxi Key Laboratory of Digital Infrastructure (GXDINBC202406) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (61962005).

Data Availability Statement

The experimental data have been presented in this paper, and further data can be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Author 1, T. The title of the cited article. Journal Abbreviation 2008, 10, 142–149.

- Rivest, R. L.; Shamir, A.; Adleman, L. A method for obtaining digital signatures and public-key cryptosystems. Communications of the ACM 1978, 21, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillier, P. Public-key cryptosystems based on composite degree residuosity classes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Prague, Czech Republic, May 2–6, 1999; pp. 223-–238. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, C. Fully homomorphic encryption using ideal lattices. In Proceedings of the forty-first annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing, Bethesda, MD, USA, May 31 – June 2, 2009; pp. 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, C.; Halevi, S.; Smart, N. P. Better bootstrapping in fully homomorphic encryption. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Public Key Cryptography, Darmstadt, Germany, May 21–23, 2012; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Halevi, S.; Shoup, V. Bootstrapping for HElib. Journal of Cryptology 2021, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Han, K. Homomorphiclowerdigits removal andimprovedFHEbootstrapping. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Tel Aviv, Israel, April 29 – May 3, 2018; pp. 315–337. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Seo, J.; Song, Y. Simpler and faster BFV bootstrapping for arbitrary plaintext modulus from CKKS. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, October 14–18, 2024; pp. 2535–2546. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, Y.; Cheon, J. H.; Kim, J.; Stehlé, D. Bootstrapping bits with CKKS. In Proceedings of the 43rd Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Zurich, Switzerland, May 26–-30, 2024; pp. 94–-123. [Google Scholar]

- Chillotti, I.; Gama, N.; Georgieva, M. Faster fully homomorphic encryption: Bootstrapping in less than 0.1 seconds. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Hanoi, Vietnam, December 4–8, 2016; pp. 3-–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chillotti, I.; Gama, N.; Georgieva, M.; Izabachène, M. TFHE: fast fully homomorphic encryption over the torus. Journal of Cryptology 2020, 33, 34–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonte, C.; Iliashenko, I.; Park, J.; Pereira, H. V. L. FINAL: faster FHE instantiated with NTRU and LWE. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Taipei, Taiwan, December 5-–9, 2022; pp. 188-–215. [Google Scholar]

- Boneh, D.; Gennaro, R.; Goldfeder, S.; Jain, A. Threshold cryptosystems from threshold fully homomorphic encryption. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, August 19–-23, 2018; pp. 565-–596. [Google Scholar]

- Mouchet, C.; Bertrand, E.; Hubaux, J. P. An efficient threshold access-structure for rlwe-based multiparty homomorphic encryption. Journal of Cryptology 2023, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Homomorphic encryption for multiple users with less communications. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 135915–135926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Alt, A.; Tromer, E.; Vaikuntanathan, V. On-the-fly multiparty computation on the cloud via multikey fully homomorphic encryption. In Proceedings of the forty-fourth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing, New York, USA, May 19–22, 2012; pp. 1219–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Dai, W.; Kim, M.; Song, Y. Efficient multi-key homomorphic encryption with packed ciphertexts with application to oblivious neural network inference. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, London, UK, November 11–15, 2019; pp. 395–412. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Chillotti, I.; Song, Y. Multi-key homomorphic encryption from TFHE. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Kobe, Japan, December 8–-12, 2019; pp. 446–-472. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, H.; Lee, D.; Song, Y.; Wagh, S. A general framework of homomorphic encryption for multiple parties with non-interactive key-aggregation. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference, ACNS 2024, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, March 5–-8, 2024; pp. 403–-430. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, B.; Zhang, J.; Deng, Y.; Dai, Y.; Feng, D. Fast blind rotation for bootstrapping FHEs. In Proceedings of the 43rd Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, August 20-–24, 2023; pp. 3-–36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Lu, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, K.; Hou, R. Faster NTRU-Based Bootstrapping in Less Than 4 Ms. TCHES 2024, 2024, 418–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, M. R.; Player, R.; Scott, S. On the concrete hardness of learning with errors. Journal of Mathematical Cryptology 2015, 9, 169–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducas, L.; van Woerden, W. NTRU fatigue: how stretched is overstretched? In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Singapore, December 6–-10, 2021; pp. 3-–32. [Google Scholar]

- Brakerski, Z.; Gentry, C.; Vaikuntanathan, V. (Leveled) fully homomorphic encryption without bootstrapping. ACM Transactions on Computation Theory 2014, 6, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Vercauteren, F. Somewhat practical fully homomorphic encryption. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2012/144, 2012. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2012/144 (accessed on January 8, 2026).

- Cheon, J. H.; Kim, A.; Kim, M.; Song, Y. Homomorphic encryption for arithmetic of approximate numbers. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptology and Information Security, Hong Kong, China, December 3–7, 2017; pp. 409–-437. [Google Scholar]

- Ducas, L.; Micciancio, D. FHEW: bootstrapping homomorphic encryption in less than a second. In Proceedings of the 34th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Sofia, Bulgaria, April 26–30, 2015; pp. 617-–640. [Google Scholar]

- Asharov, G.; Jain, A.; López-Alt, A.; Tromer, E. Multiparty computation with low communication, computation and interaction via threshold FHE. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Cambridge, UK, April 15–19, 2012; pp. 483-–501. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Micciancio, D.; Kim, A.; Choi, R.; Deryabin, M. Efficient FHEW bootstrapping with small evaluation keys, and applications to threshold homomorphic encryption. In Proceedings of the 42nd Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Lyon, France, April 23–27, 2023; pp. 227-–256. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Rovira, S. Efficient TFHE bootstrapping in the multiparty setting. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 118625–118638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.; Min, S.; Song, Y. Towards practical multi-key TFHE: parallelizable, key-compatible, quasi-linear complexity. In Proceedings of the 27th IACR International Conference on Practice and Theory of Public-Key Cryptography, Sydney, NSW, Australia, April 15–-17, 2024; pp. 354–-385. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Tan, B. H. M.; Wang, L. P.; Aung, K. M. M. Multi-key fully homomorphic encryption from NTRU and (R) LWE with faster bootstrapping. Theoretical Computer Science 2023, 968, 114026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, C. A polynomial time algorithm for breaking NTRU encryption with multiple keys. Designs, Codes and Cryptography 2023, 91, 2779–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Van Leeuwen, B.; Zajonc, O. FINALLY: A multi-key FHE scheme based on NTRU and LWE. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2024/1505, 2024. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/1505 (accessed on January 8, 2026).

- Regev, O. On lattices, learning with errors, random linear codes, and cryptography. Journal of the ACM 2009, 56, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubashevsky, V.; Peikert, C.; Regev, O. On ideal lattices and learning with errors over rings. Journal of the ACM 2013, 60, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genise, N.; Gentry, C.; Halevi, S.; Li, B. Homomorphic encryption for finite automata. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Kobe, Japan, December 8-–12, 2019; pp. 473-–502. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, M.; Bai, S.; Ducas, L. A subfield lattice attack on overstretched NTRU assumptions: Cryptanalysis of some FHE and graded encoding schemes. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, August 14–18, 2016; pp. 153–-178. [Google Scholar]

- Alperin-Sheriff, J.; Peikert, C. Faster bootstrapping with polynomial error. In Proceedings of the 34th Annual Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, August 17–21, 2014; pp. 297–-314. [Google Scholar]

- Mouchet, C.; Troncoso-Pastoriza, J. Multiparty homomorphic encryption from ring-learning-with-errors. Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies 2021, 2021, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraitsberg, M.; Lindell, Y.; Osheter, V.; Smart, N. P. Adding distributed decryption and key generation to a ring-LWE based CCA encryption scheme. In Proceedings of the 24th Australasian Conference, ACISP 2019, Christchurch, New Zealand, July 3–-5, 2019; pp. 192-–210. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver, D. Efficient multiparty protocols using circuit randomization. In Proceedings of the 11th Annual International Cryptology Conference on Advances in Cryptology, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1991; pp. 420–432. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, M.; Orsini, E.; Scholl, P. MASCOT: faster malicious arithmetic secure computation with oblivious transfer. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Vienna, Austria, October 24–28, 2016; pp. 830–842. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, M.; Pastro, V.; Rotaru, D. Overdrive: Making SPDZ great again. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Tel Aviv, Israel, April 29 – May 3, 2018; pp. 158–-189. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, M.; Sun, K. Secure quantized training for deep learning. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning, 2022; pp. 10912–10938. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero, D. An introduction to secret-sharing-based secure multiparty computation. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2022/062, 2022. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2022/062 (accessed on January 8, 2026).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).