1. Introduction

An independent and effective judiciary is undeniably a fundamental component of any society. Consequently, the repercussions of failing to deliver timely justice can have a profound impact on the lives of all parties involved (MUSOKE, 2023). It serves as a check on the powers of the executive and legislative branches, ensuring their compliance with the law and Constitution (Kulmie, 2025). The foundational origins of the legal revolution can be traced back to the federalist ideology and the efforts of various transnational movements advocating for European unification during the 1940s and 1950s. It was during this period that the most ambitious constitutional ideas regarding the future structure of Europe emerged, including several initiatives to envision the establishment of a European legal framework. Additionally, numerous politicians and legal experts who participated in the constitutional debates of the late 1940s and early 1950s would later, in various roles, either directly engage in or support the legal revolution led by the European Court of Justice (Rasmussen, 2008). In a democratic system, it is anticipated that a broad spectrum of significant issues will be addressed effectively and efficiently. This includes ensuring citizens have access to basic education, providing social amenities like water supply, a reliable road network, electricity, and hospitals, and administering justice that upholds the rule of law and guarantees equal access to justice. (Okafor et al., 2020).

In nations with advanced economies like Norway, trust among citizens is bolstered by a robust institutional framework that guarantees transparency and accountability among government officials. For a developing nation such as Bangladesh, it is crucial to build a solid foundation of trust between its citizens and governmental bodies (Jalal et al., 2024). The judiciary in Nigeria plays a crucial role in maintaining the rule of law and safeguarding human rights. Although it is constitutionally mandated to operate independently, the judiciary encounters numerous challenges, such as political meddling, corruption, inefficiencies, and obstacles to justice for marginalized communities. In Nigeria, the judiciary is charged with the vital responsibility of upholding the rule of law within a complex political and social environment. However, the country’s diverse legal system often leads to jurisdictional disputes and inconsistencies, complicating judicial proceedings (Berebon, 2024)

The Judiciary in Kenya is crucial in ensuring justice is served and the rule of law is maintained. Established under Chapter Ten of the Constitution of Kenya 2010, it operates as an independent branch of government with the responsibility to resolve disputes, interpret legal statutes, and uphold constitutional principles. Judicial authority is derived from the populace.2 Article 159 mandates that justice must be administered efficiently and impartially. Additionally, the constitution protects against influence, control, or dominance by individuals or authorities.3 Despite this, Kenya’s judiciary has long faced numerous obstacles, including corruption, case backlogs, inadequate infrastructure and human resources, political meddling, and inefficiencies in judicial management (Odhiambo, 2025).

Marth Ezzard describes the judiciary as the governmental branch responsible for interpreting and enforcing laws, resolving legal conflicts, and administering justice. Essentially, the judiciary consists of a network of courts, tribunals, and administrative entities, along with the judges and judicial officials who oversee them. This judicial framework serves as the state’s mechanism for settling disputes between individuals, as well as between individuals and the state, in accordance with the law (Hamdi, 2013). Justice is a fundamental value cherished across all human societies. In the absence of justice, democracy cannot truly exist. The independence of the judiciary plays a crucial role in strengthening democracy. Without a judiciary that can deliver justice impartially, the concept of democracy becomes meaningless and remains a significant challenge (Kamusiime, 2014).

The essence of judicial independence lies in the principle of the separation of powers, which asserts that the judiciary, as one of the three fundamental and equal pillars of a modern democratic state, should operate independently from the legislature and the executive. The interaction among these three branches of government should be characterized by mutual respect, with each acknowledging and honoring the appropriate roles of the others (Ogari, 2014). This independence is crucial because the judiciary plays a significant role in relation to the other two branches. As outlined in the Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct (2007), a judge’s responsibility is to administer the law impartially, without succumbing to social or political pressures.

The performance of Somali courts is shaped by several elements, such as the stability of the government, adherence to the rule of law, the legal structure, judicial independence, accountability, available resources, public confidence, and cultural traditions. The judicial system in Somalia disintegrated in 1991 following the onset of civil war. Historically, Somalia has experienced considerable instability, which has significantly affected all areas of society, including the public and private sectors, as well as the general populace (Kulmie, 2025).

The judiciary in Somalia holds authority over all civil and criminal cases, including those involving international law where Somalia is a participant, or any other jurisdiction granted by law. A significant issue in Somalia is the limited capacity of institutions responsible for compliance, as well as insufficient institutional ability to apply, implement, and enforce various protocols, conventions, and treaties. This includes a lack of experience, limited financial resources, and technical expertise, among other factors (Osman, 2021).

Somalia’s legal system is characterized by a complex blend of statutory, customary, and religious laws that coexist and are interwoven. Although there have been strides in improving Somalia’s justice services, such as investing in human capital through scholarships, offering legal aid to those who cannot afford it, and establishing protocols for custodial services, the situation is further complicated by personalized or neo-patrimonial relationships and inter-agency rivalries among Somali political elites and justice chain actors. These actors include the police, prosecutors, courts, custodial services, intelligence agencies, special units, and commercial security firms, which operate in ways that differ from the standard bureaucracies and institutions typically associated with the justice sector in Westphalian states (Ali, 2023).

In Puntland, Somalia, the legal field is essential for maintaining justice and the rule of law. Nevertheless, judges and lawyers encounter numerous challenges that hinder their effectiveness. These difficulties, which include emotional strains and professional limitations, are influenced by a complex interplay of social, cultural, political, and institutional elements. Political meddling and clan allegiances often jeopardize the fairness of court rulings, while scarce financial and human resources, outdated infrastructure, and insufficient professional development opportunities further limit the capabilities of legal practitioners (Mohamed, 2025).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Literature

2.1.1. Concept of the Judiciary

The judiciary functions as an independent arm of state authority, distinct from the legislative and executive branches, as well as from political parties and public organizations. It holds a unique position within the framework of state institutions. The judiciary’s operations are closely tied to the protection of human rights and freedoms, ensuring the constitutional rights and liberties of individuals through the process of justice (Albina, 2021).

2.1.2. Concept of Public Confidence

Public confidence in democratic institutions is crucial for the effective and enduring operation of a democratic system. This public confidence is necessary not only for elected bodies like the legislature and executive but also for non-elected entities such as the judiciary, which must have substantial public support. When judges issue rulings that go against the wishes of political majorities, the judiciary can face a legitimacy crisis (Aydın Çakır & Şekercioğlu, 2016). The diversity across fields, it is widely accepted that two key elements are essential for trust: (1) a level of ‘risk’ and (2) ‘interdependence’. These factors are vital because trust involves a tripartite relationship where A relies on B to perform X. Essentially, A anticipates that B will act in a way that benefits A. This tripartite dynamic introduces risk, as individuals are unsure if an institution, such as the judiciary, will fulfill its responsibilities as expected. Risk arises because governmental bodies wield a certain amount of power over individuals, which can be exercised appropriately or not. If there were no uncertainty about how an organization handles the trust it receives, trust would be unnecessary (Grimmelikhuijsen & Klijn, 2015).

2.1.3. Determinants of Public Confidence in the Judiciary

The determinants of public confidence in the judiciary are explained in the subsequent paragraphs.

Transparency and Accountability

The term ‘accountable,’ according to the Oxford Dictionary, refers to being responsible for one’s own choices or actions and being expected to justify them when questioned. The idea of judicial accountability dates back to the judiciary’s independence (Jayasurya, 2010). Transparency refers to the degree to which citizens can access information about the performance of public institutions (Irfan, 2017). The concept of transparency can be understood through three metaphors: it is seen as a societal value that combats corruption, as a representation of open decision-making in governments and nonprofits, and as a sophisticated instrument of effective governance in programs, policies, organizations, and nations. In the first metaphor, transparency is closely linked with accountability. In the second, while transparency promotes openness, it also raises issues related to secrecy and privacy. In the third, policymakers integrate transparency with accountability, efficiency, and effectiveness (Ball, 2009).

The transparency of legal proceedings, particularly public hearings, decisions, and judgments, has long been a crucial element of ensuring a fair trial. Open proceedings fulfill several purposes, including allowing some degree of oversight over the judicial system. However, in today’s world, simply having open trials is not enough to meet the public’s demand for information. Judicial matters have become central to public discourse, with televised media acting as a conduit to keep the public informed. We live in an era where information is exchanged at incredible speeds, influencing both how courts disseminate information and the public’s expectations (Voermans, 2007).

Accessibility

An independent judiciary is a fundamental aspect of governance, it is equally important that justice remains accessible to protect individuals’ rights.(Vickrey et al., 2008). Access to justice refers to the capacity of individuals to address their legal concerns through various justice and legal services. These services include formal courts, legal information, and representation by lawyers, Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), and enforcement mechanisms. In the context of access to justice, “access” means “to reach,” while “justice” represents a lawful right that can be obtained according to the law. Therefore, accessing justice from this perspective involves reaching something we are legally entitled to, which is our right. Additionally, it involves the ability to seek a remedy for any violation of rights or entitlements and to engage with the justice system, including courts, under the established standards of national and international law (Lakho et al., 2024).

Defining ‘Access to Justice’ is a challenging task. It has deep roots in ancient traditions across various cultures and is closely associated with political, legal, and rhetorical symbols of undeniable power and appeal for those involved in governance. Access to justice is fundamentally connected to the concept of “justice,” serving as its essential foundation. The idea of justice brings to mind the rule of law, conflict resolution, the institutions that create laws, and those that enforce them; it embodies fairness and implicitly acknowledges equality without discrimination. Initially, ‘access to justice’ was seen as a natural right. As such, it did not necessitate any proactive measures by the state, allowing an aggrieved individual to seek justice freely (Sastry, 2016).

Efficiency and Effectiveness

The Cambridge Dictionary describes the noun ‘efficiency’ as “the effective use of time and energy without any waste,” or “the state or fact of achieving desired results without waste, or a specific method of doing so.” In the context of Business English, the same dictionary defines it as “a scenario where an individual, company, factory, etc., utilizes resources like time, materials, or labor efficiently, without any wastage,” or “a situation where a person, system, or machine operates effectively and swiftly.” According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, ‘efficiency’ is “the capability to accomplish or produce something without wasting materials, time, or energy: the quality or degree of being efficient,” and it lists ‘effectiveness’ and ‘efficacy’ as synonyms. The Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary similarly defines ‘efficiency’ as “the quality of performing tasks well without wasting time or money (Codrea, 2021).”

Public Perceptions and Awareness

The interplay between the judiciary, public sentiment, public trust, and the institutional power of courts within a democracy is intricate. It is often claimed that the effectiveness and even the legitimacy of judicial authority rely on public confidence (Mack et al., 2018). Compared to elected political bodies, which are frequently assessed through public opinion surveys, courts often receive less attention and visibility from the public. In many countries, including those that are highly developed, there is generally a low level of awareness and focus on courts, criminal justice, sentencing, and the rules and practices surrounding judicial appointments and retention. At a minimum, the degree to which individuals pay attention to and comprehend the characteristics and functioning of judicial systems is likely to differ widely (Garoupa & Magalhães, 2020).

Enforcement of Judicial Decisions

The challenge of ensuring that judgments are enforced is significant both domestically and internationally. In certain nations, judgments are often only partially enforced, delayed significantly, or not enforced at all. A consequence of failing to enforce judgments is the imposition of penalties for not meeting international obligations (Mytnyk et al., 2020). The duty to enforce judgments is vital to maintaining the integrity of any legal system, whether it is national or international. Enforcing judgments is essential for bolstering the judiciary’s authority and fostering trust in the system. Even the most exemplary case law is ineffective if not enforced. Ensuring judgments are fully and promptly enforced is a hallmark of a democratic society. There is substantial evidence that courts feel more independent when enforcement is likely (Mytnyk et al., 2020).

Judicial Independence

Judicial independence is a complex and elusive concept, challenging to define and even harder to quantify, as it intersects various viewpoints. It involves examining the motivations and constraints that judges face in relation to other governmental bodies. To evaluate the level of independence in a nation, one can consider the legal frameworks that dictate the interactions between the judiciary and other branches of government. However, this alone is insufficient. These laws must be adhered to. Consequently, the extent of independence hinges on two factors: 1) the legal frameworks that define the relationship between judges and other branches, and 2) whether politicians comply with these legal frameworks (Ríos-Figueroa, 2006). Judicial independence encompasses both internal (normative) and external (institutional) dimensions. Normatively, judges are expected to function as independent moral agents, executing their responsibilities without succumbing to corrupt or ideological pressures. In this regard, a judge’s independence or impartiality is a commendable trait. Nonetheless, judges are human, and their rulings can significantly affect individuals, necessitating institutional safeguards to protect them from external pressures or temptations. Thus, judicial independence is an institutional characteristic of the judicial environment, valued not solely for its own sake but as a means to achieve broader objectives, such as maintaining the rule of law and constitutional principles (Ferejohn, 1998).

2.2. Empirical Review

The empirical review has been done according to the specific research objectives.

2.2.1. Assessment of the Overall Level of Public Confidence in the Judiciary System

Public trust holds significant importance for public officials as it is crucial for fostering the creation and execution of public policies, which in turn facilitates effective and cooperative compliance. Officials who are trusted by the public can adeptly utilize their skills, along with their discretion and autonomy, to boost their efficiency, responsiveness, and effectiveness. The connection between public officials and citizens is vital for the success and progress of public affairs, while a disconnect can lead to the decline of public managers (Danaee Fard & Anvary Rostamy, 2007). Trust in government is crucial for the stability of democratic systems, the successful execution of policies, and the preservation of social order (Govindasamy, 2024)

Why does public confidence in courts matter? Simply put, courts, perhaps even more so than other democratic political bodies, rely on the public’s goodwill to sustain their effectiveness. The legitimacy that comes from public backing is crucial for judicial bodies, as they lack the means to enforce their rulings through force(Wenzel et al., 2003). In theory, someone might have a high level of confidence in other people, such as by volunteering for a social cause or assisting a neighbor, while having little faith in the political system, and the opposite can also be true. Public confidence in a society’s governing bodies acts as the adhesive that binds it together or serves as a measure of how effectively these institutions are perceived to function by the citizens (Atmor & Hofnung, 2024). The fundamental belief is that either trust or confidence is essential for maintaining democratic systems. Public confidence grants legitimacy to the court’s authority and decisions, reducing the likelihood of citizens challenging and disregarding court procedures. Many scholars argue that a justice system lacking confidence not only struggles to engage citizens in criminal proceedings but also risks a complete overhaul of the entire system (Boateng, 2020).

Efficient public institutions are crucial for economic growth and fostering public trust. A significant factor in the effectiveness and credibility of these institutions is the level of trust they inspire in the people they serve. Yet, in numerous countries, trust in government, the judiciary, and other institutions has waned over time. For instance, individuals with little trust in the judicial system might avoid seeking justice and instead turn to informal methods to settle disputes. Various studies have explored the factors influencing trust in the judicial system (Sampaio et al., 2014). A fundamental tenet of justice is that no judge, lawyer, or citizen should be exempt from the law, nor should they be outside its reach. The judiciary plays a crucial role in upholding the rule of law and safeguarding human rights and freedoms in any nation. It also serves as a vital check and balance on the other branches of government, ensuring that parliamentary laws and executive actions adhere to the Constitution and the rule of law (Ndulo, 2011). They observed that respondents with higher annual incomes were more confident in the justice system’s ability to bring offenders to justice, address victims’ needs, uphold the rights of the accused, and ensure fair treatment for the accused (Sampaio et al., 2014). The absence of an independent and unbiased judiciary has numerous consequences. It fosters a culture of impunity and forces critics and adversaries of the regime to leave the country, as they cannot anticipate fair treatment in cases fabricated by the government to target them (Nyamwasa et al., 2010).

2.2.2. Factors that Influence Public Confidence in the Judiciary System

The performance of Somali courts is shaped by several elements, such as the stability of the government, adherence to the rule of law, the legal framework, judicial independence, accountability, available resources, public confidence, and cultural norms. The judicial system in Somalia disintegrated in 1991 following the onset of civil war. Historically, Somalia has experienced considerable instability, significantly affecting all societal sectors, including the public and private sectors, as well as the general populace (Kulmie, 2025).

In the literature concerning factors that that influence public confidence in the judiciary system. , Two key factors emerge. Firstly, judicial independence is linked to increased public trust. Secondly, there is a notion that familiarity with courts breeds appreciation. But what exactly makes judicial systems trustworthy to the public? We explore this by examining three interconnected issues. Initially, a major assertion in the limited comparative empirical research on this subject is that public trust in legal systems is influenced by specific ‘institutional qualities of the third power,’ notably judicial independence. However, while independence grants judges and courts the liberty to resist certain predictable pressures to disregard the law, it also liberates them from any obligation to adhere to it, potentially allowing them to create law in problematic ways (Garoupa & Magalhães, 2020).

Accountability is also another factor that influences public confidence in the judiciary system. While independence is appealing and fosters trust, it raises the issue of how to handle courts that operate without regard for the law and judges who act irresponsibly. We desire judges and courts to function independently, yet we also expect them to be accountable, or at least to behave in a manner that accountability can encourage: treating those who appear before them with respect, distinguishing between relevant and irrelevant arguments, and resolving cases promptly and in accordance with the law (Garoupa & Magalhães, 2020).

2.2.3. Relationship Between Socio-Demographic Factors and Public Confidence in the Judiciary System

Demographics refer to the statistical analysis of a population’s characteristics, such as age, gender, and race. This analysis provides socioeconomic data, including education, employment, income, marriage, birth, and death rates. Socio-demographics merge social and demographic factors to describe individuals within a specific population, highlighting shared traits among group members (Lakho et al., 2024). Consequently, socio-demographics encompass aspects like age, employment, education, income levels, religion, race, ethnicity, and migration. These are categorized into three primary branches: the sociological (social) branch, which includes age, gender, family composition, and household size; the demographic branch, which covers geographic features like city, county, region, and country; and the economic branch, which involves education and profession. However, access to justice has not been consistent, as it is affected by various factors, including the sociodemographic characteristics of litigants. Factors such as socioeconomic status, access to information, geography, and ongoing social norm discrimination are sociodemographic determinants of justice accessibility. Gramatikov identified sociodemographic variables like age, gender, employment status, education, and whether a litigant resides in a rural or urban area as influencing factors for accessing justice (Lakho et al., 2024).

Some studies explore the connection between experiences with the judicial system and the degree of confidence in the judiciary. Benesh investigates how experience, perceptions of procedures, and institutional factors might influence confidence levels. Her findings suggest that well-educated individuals who have served as jurors possess a strong understanding of the court system, have a high baseline confidence in government institutions, and reside in states where judges are appointed and crime rates are low, tend to exhibit the highest confidence in state courts (Sampaio et al., 2014). Conversely, individuals with limited formal education, who have been defendants at least once, lack knowledge about the courts, have little trust in government institutions, and live in states with elected judges and high crime rates, tend to show the lowest confidence levels. Some scholars reveal that court users generally believe the court performs well, while non-users also claim it does a good job. The positive assessments from non-users may be linked to broader justice-related factors. Thus, direct experience tends to make opinions about the judiciary more pronounced (Sampaio et al., 2014).

Generally, trust can be influenced through three primary channels: an individual’s personal traits, the institutional environment in which they operate, and the broader societal and community context. For institutional trust to exist, key societal institutions must carry out their roles with integrity and fairness. However, institutions are diverse and their roles are constantly evolving. Bouckaert and Van de Walle argued that trust encompasses more than just satisfaction, yet it can serve as a quick and straightforward predictor. Nonetheless, it cannot stand alone as an indicator of good governance because public trust in government is dynamic and thus a moving target. For trust in the judicial system to be established, there must be alignment between citizens’ expectations and the perceived actual functioning of the courts (Lawor et al., 2025).

The level of a country’s wealth influences both institutional confidence and judicial independence, though the exact nature of this influence is uncertain. Greater prosperity might lead to increased satisfaction or heightened expectations regarding institutional effectiveness. However, the likelihood of the judiciary being financially independent is higher in wealthier nations (Bühlmann & Kunz, 2011). Additionally, a country’s population size acts as another macro-level control variable. On an individual scale, our models consider factors such as gender, age, education, and trust in the national parliament. Studies on political confidence indicate that women and those with higher education tend to have more trust in institutions. Moreover, confidence tends to grow with age (Bühlmann & Kunz, 2011).

The literature suggests that numerous elements, such as gender, race, income, educational background, and prior interactions with the judiciary, affect public confidence in the courts. Lawrence provides evidence indicating that in the United States, women tend to have less reliance on justice compared to men. Generally, these findings appear to be linked to perceived violence and discrimination against women. Scholars also demonstrates that in the United States, individuals with higher incomes and more years of formal education tend to express greater trust in most of the institutions studied. Trust in the criminal justice system is typically more common among younger individuals, those with higher education, and those with greater incomes (da Silveira Bueno et al., 2015). Additionally, people who possess more knowledge about the courts are more inclined to have confidence in them, as are those with higher education levels. In the Brazilian context, it is also anticipated that individuals with higher incomes and more years of formal education will show greater trust in the Brazilian judicial system (da Silveira Bueno et al., 2015).

2.3. Theoretical Review

The study was guided by three theoretical frameworks: Procedural Justice Theory, Institutional Legitimacy Theory, and Social Trust Theory.

2.3.1. Procedural Justice Theory

Procedural Justice Theory examines how individuals perceive the fairness of procedures, determining whether they are just or unjust, ethical or unethical, and whether they align with societal standards for fair processes in social interactions and decision-making. There are two primary aspects of procedural fairness judgments: the fairness of decision-making and the fairness of interpersonal treatment (Tyler & Mentovich, 2023). Regarding its relevance to the study at hand, this theory highlights that people’s trust in the justice system is influenced more by the fairness of the process than by the outcomes of cases. It helps in evaluating how fairness in hearings, equal treatment under the law, and transparency in decision-making affect public confidence in the judiciary.

2.3.2. Institutional Legitimacy Theory

Legitimacy refers to the widespread belief or assumption that an entity’s actions are acceptable, suitable, or fitting within a socially constructed framework of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions. Legitimacy theory serves as a tool that aids organizations in adopting and enhancing voluntary social and environmental disclosures to fulfill their social contract, which is crucial for achieving their goals and navigating a volatile and unpredictable environment. This theory suggests that institutions achieve legitimacy when they are seen as rightful, trustworthy, and in harmony with societal values (Burlea & Popa, 2013). Regarding the topic’s relevance, it offers a framework to assess how citizens from Qardho, Garowe, and Bossaso districts view the judiciary’s authority, independence, and adherence to justice principles, and how these perceptions influence confidence levels. If the judiciary in Qardho, Garowe, and Bossaso is perceived as corrupt, politically biased, or inaccessible, its legitimacy diminishes, resulting in low public trust. On the other hand, consistent law enforcement and alignment with community standards bolster its legitimacy.

2.3.3. Social Trust Theory

Social trust is a component of a larger set of personality traits that encompasses optimism, a belief in cooperation, and confidence in people’s ability to resolve conflicts and coexist harmoniously. If social trust is influenced by the social conditions people experience, it should correlate statistically with societal factors. However, there is little consensus on which factors are significant. The traditional perspective suggests that a society with a diverse array of voluntary associations and organizations is likely to foster high levels of social trust (Delhey & Newton, 2003). This theory, rooted in the ideas of de Tocqueville and John Stuart Mill, is central to contemporary discussions on social capital. We learn to engage by engaging, and through regular, voluntary interactions with others, we develop ‘the habits of the heart’—trust, reciprocity, cooperation, empathy, and an understanding of shared interests and the common good. Social trust is an attribute of social systems rather than individuals. From this standpoint, studying trust requires a top-down approach that examines the systemic or emergent properties of societies and their key institutions. Social trust is generally high among citizens who perceive minimal severe social conflicts and where public safety is strongly felt (Delhey & Newton, 2003). In terms of relevance to the topic at hand, it is useful to examine how broader trust dynamics (such as trust in government, community relations, and leadership) influence confidence in the local judiciary system.

2.3.4. Problem Statement

In all societies, the judiciary is anticipated to serve as the ultimate protector of justice, equity, and the rule of law. In fragile settings like in Puntland state of Somalia, where people’s livelihoods and security are closely tied to their trust in institutions, the judiciary assumes a more significant role in fostering peace and stability. However, in recent times, residents of Puntland have increasingly voiced concerns about the true accessibility, transparency, and fairness of the courts. Many community members are reluctant to pursue justice because they perceive court procedures as slow, expensive, or swayed by personal connections and clan influences. Others remain doubtful about whether the judiciary can safeguard them impartially.

The core problem is that public confidence in the judiciary system in Puntland remains low due to perceptions of inaccessibility, inefficiency, infective, lack of accountability, lack of transparency, independence and partiality.

The absence of a clear understanding of how the judiciary is perceived by the public creates a significant gap. Without insight into whether citizens genuinely trust the courts, it becomes challenging for policymakers and justice stakeholders to implement reforms that address the needs of the people. In post-conflict areas like Puntland, where building trust in institutions is crucial for stability, overlooking public perceptions risks undermining the very foundation of justice. This study, therefore, tackles the urgent issue of gauging public confidence in the judiciary system in Puntland. By listening to the community’s perspectives, it aims to illuminate the challenges and opportunities for enhancing justice delivery in a manner that is fair, accessible, and trusted by those it serves.

Therefore, the general objective of the study is to assess the public confidence in the judiciary system of Puntland state of Somalia. The study assessed the following specific research objectives:

To assess the overall level of public confidence in the judiciary system in Qardho, Garowe, and Bossaso Districts.

To identify the key factors that influence public confidence in the judiciary system in Qardho, Garowe, and Bossaso Districts.

To analyze the relationship between socio-demographic factors (e.g., age, gender, education) and public confidence in the judiciary system.

3. Materials and Methods

The study utilized a cross-sectional design to enhance public confidence in the judicial system within Puntland state, Somalia, and adopted a mixed-method approach that integrated both quantitative and qualitative research methods. This cross-sectional design was used as it is crucial for offering a timely snapshot of public trust in the judiciary across target regions, enabling the detection of patterns, relationships, and demographic differences at a particular moment. It is efficient, cost-effective, and useful for informing immediate policy and institutional responses.

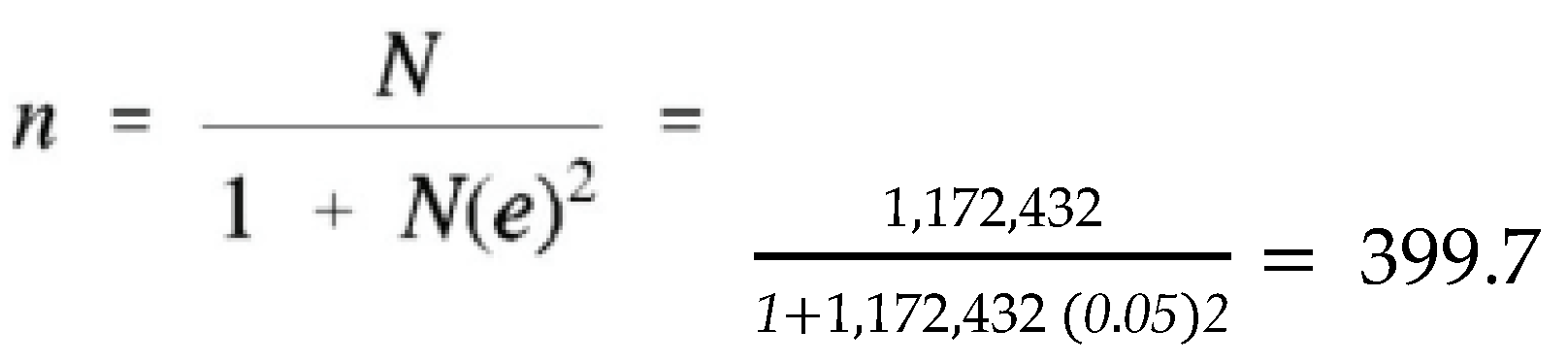

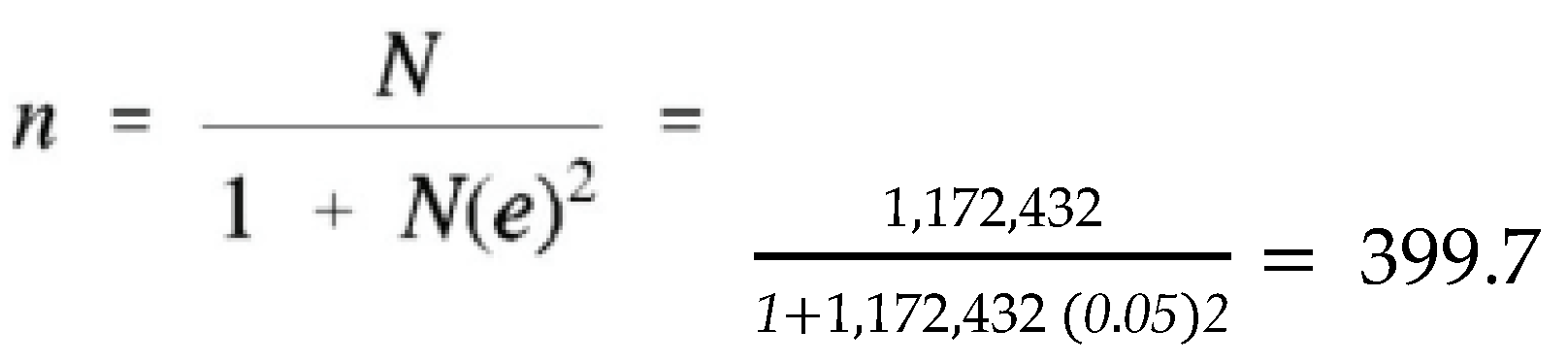

The study targeted a population of 1,172,432 individuals, distributed as follows: 152,711 in Qardho, 300,540 in Garowe, and 719,181 in Bossaso, according to the 2023 population data from the Food Security and Livelihood Analysis Unit (FSNAU). The sample size for this study was determined using Slovin’s formula, resulting in a sample size of 400.

where n –is the sample size, N -is the population size, and e- is the margin of error (0.05). As per the below table, the allocation of the sample size per district was based on the population per district.

Table 1.

Sample size distribution per district.

Table 1.

Sample size distribution per district.

| No |

District. |

Total Population. |

Sample size. |

| 1 |

Qardho. |

152,711. |

|

| 2 |

Garowe. |

300,540. |

= 103 |

| 3 |

Bossaso. |

719,181. |

|

| Total |

1,172,432. |

400. |

Two data collection instruments were employed: a structured questionnaire and key informant interviews (KIIs). Structured questionnaires with closed questions were administered to a representative sample of 400 residents of Qardho, Garowe, and Bossaso districts to gather quantitative data on their level of confidence in the judiciary. Twelve Key informant interviews were conducted with Judges, lawyers, community elders, and Sheiks to obtain qualitative insights into the factors shaping public trust. The data collection process was conducted through a series of methodical steps. Initially, the research instruments, comprising a structured questionnaire and key informant interviews, were developed. Participants for the study were selected via a convenience sampling method, wherein individuals were approached based on their availability and willingness to participate in the study. Data collection was executed by trained data collectors utilizing the KOBO digital/mobile data collection tool, while key informant interviews, totaling twelve, were conducted by a trained qualitative data collector.

Stata statistical software was utilized in the data analysis to produce percentages, frequencies, tables, and statistical conclusions that align with the study objectives. A range of inferential statistical tests was employed. Correlation analysis was conducted to assess the strength and direction of the relationships between public confidence and key elements such as transparency, accessibility, efficiency, and awareness. Chi-square tests of independence were applied to assess whether socio-demographic characteristics (such as gender, age, education level, and occupation) were significantly associated with confidence levels in the judiciary. Additionally, multiple regression analysis was employed to identify the primary predictors of public confidence in the judicial system. Thematic analysis was performed on the interview transcripts for the qualitative analysis to discern prevalent themes and insights regarding public confidence in the judiciary system.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

Table 2 presents the demographic characteristics of the respondents, revealing a majority of younger individuals: 28% were aged 20–25, and 22.5% were aged 26–30. As age increased, representation decreased, with 16.25% aged 31–35, 15.75% aged 36–40, 12.25% aged 41–50, and a mere 5.25% aged 51 or older. The gender distribution was relatively balanced, comprising 53.25% male and 46.75% female respondents. Regarding educational attainment, the majority of participants were educated: 37% possessed a bachelor’s degree, 15.75% held a diploma, 13.25% had completed secondary education, and 10.75% had obtained a master’s degree, while 2.75% held a PhD. Notably, 15.5% were illiterate, indicating a diversity in educational backgrounds. In terms of work experience, 43.75% had 0–3 years of experience, 23.25% had 4–6 years, and fewer had longer tenures, with 13.5% having 7–9 years, 6.25% having 10–12 years, and 13.25% having 13 or more years. Occupationally, 34.5% were self-employed, 21.15% were employed in the private sector, 19.5% were unemployed, 14% were students, and 10.75% were employed in the public sector.

4.2. Assessing the Overall Level of Public Confidence in the Judiciary System

This research objective assesses the overall level of public confidence in the judiciary system among the respondents. Understanding citizens’ perceptions of the judiciary is crucial, as confidence in the judicial process reflects trust in the rule of law and the effectiveness of governance institutions.

Table 3 presents a summary of respondents’ views on key aspects of the judiciary, such as fairness, transparency, independence, and accessibility. A total of 62% agreed or strongly agreed that the judiciary is fair and impartial, while 29.5% were neutral or disagreed, highlighting ongoing concerns about fairness and impartiality. The qualitative findings support this mixed perception. Several informants articulated that judicial processes lack transparency and effective communication. They noted that individuals involved in cases are not furnished with comprehensive information and further observed that the majority of people remain unaware of the decision-making processes

In terms of feeling safe when seeking justice, 67.75% expressed confidence in using the courts, with only 12% disagreeing, indicating widespread trust in the judiciary’s protective function. However, key informants observed that while courts may provide a sense of physical security, the equitable application of justice remains inconsistent, particularly for marginalized groups. This distinction underscores that safety does not inherently equate to fairness.

Perceptions of judicial independence were varied: 55.25% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that judges act independently, while 20.75% disagreed and 17.25% remained neutral, indicating ongoing concerns regarding potential political or clan influence. Qualitative findings strongly supported this perception gap, highlighting political interference and clan bias as predominant concerns. These findings indicate widespread corruption and external pressures, leading to a significant erosion of public confidence in the judiciary at all levels. Furthermore, it is noted that many judges are influenced by clan elders.

Confidence in the enforcement of court rulings was relatively robust, with 63.5% agreeing or strongly agreeing that decisions are implemented fairly, although 14.75% expressed disagreement. Regarding transparency and access to information, 62.5% perceived judicial processes as open and accessible, yet 32.5% were neutral or disagreed, suggesting areas for improvement. Finally, when queried more directly about independence from political interference, 63.25% expressed confidence, though 18.5% disagreed, underscoring persistent doubts about political neutrality within the judiciary. The Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) underscore the concerns raised by dissenting individuals. Respondents observed that enforcement is inconsistent and frequently favors those with political or social influence. The implementation of court rulings is marked by variability, unless the individual possesses substantial influence, and it was noted that justice is not consistently applied in an equitable manner. Consequently, while the majority of individuals hold a favorable view of enforcement, qualitative findings reveal considerable frustration among those who have witnessed or experienced selective enforcement. Key informants corroborated this skepticism, emphasizing that judicial decisions are frequently influenced by bribery, clan loyalty, and political pressure. They noted the prevalence of corruption, favoritism, and pressures from businesspeople, clan chiefs, and politicians, with many judges originating from clan-based systems. These qualitative insights elucidate why nearly 30% of survey respondents remained neutral or disagreed with assertions of impartiality, suggesting that personal experiences reinforce doubts regarding the fairness of judicial processes.

4.3. Identifying the Key Factors that Influence Public Confidence in the Judiciary System

This research objective focuses on identifying the primary factors that shape and influence public confidence in the judicial system. A majority of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that judicial transparency, clarity of decisions, and competence of judicial staff are key elements that influence trust. Informants Interview findings acknowledged the competence of certain judges but underscored the necessity for professionalization, training, and recruitment based on merit.

Accessibility-related factors also played a crucial role. About 58.75% of respondents agreed that judicial services that are accessible help build public trust, and 61.25% agreed that the distance to courts affects people’s willingness to seek and trust justice. This shows that geographical and physical access remains a significant determinant of public trust. The qualitative results further illustrate why accessing the judiciary remains a major obstacle for numerous community members. Participants consistently pointed out that high legal expenses, intricate court procedures, and entrenched cultural barriers make it especially challenging for women, rural inhabitants, and economically disadvantaged groups to pursue justice through formal channels. These difficulties often lead marginalized groups to steer clear of the formal judicial system entirely. As several informants noted, many individuals—particularly those with limited resources or unfamiliarity with legal processes—tend to depend on informal dispute-resolution methods, such as clan elders or customary systems, as they are seen as more affordable, less bureaucratic, and culturally acceptable. This dependence on informal systems highlights the ongoing gaps in judicial accessibility and trust in the formal justice process.

Timeliness of case resolution also emerged as a concern. While 59% agreed that the timeliness of case resolution has no effect on public confidence in the judiciary system, 30.25% indicated that delays in court processes contribute to declining confidence, and 10.75% remained neutral on this issue. The judiciary’s responsiveness to community needs received mixed responses. While 61.25% agreed that the judiciary’s responsiveness has no effect on public confidence in the judicial system, 20.75% indicated that poor responsiveness decreases public confidence, and 14.75% remained neutral. This reflects inconsistencies in how judicial services meet community expectations.

Access to information appears to significantly influence public confidence in the judiciary. Approximately 71.75% of respondents concurred that access to judicial information enhances public confidence in the judicial system, suggesting that legal awareness campaigns may have some impact, although a considerable portion of the population remains uninformed.

Media coverage was also identified as an influential factor, with 72.75% of respondents agreeing that media narratives shape public trust in the judiciary. This indicates that media portrayals—whether positive or negative—play a substantial role in influencing public perceptions. Furthermore, cultural and clan dynamics continue to exert a strong influence, with approximately 61.25% of respondents agreeing that these factors affect perceptions of the judiciary. This finding underscores the ongoing impact of informal structures and social norms on trust in formal justice institutions. Data from Key Informant Interviews indicate that, while awareness is present in urban areas, significant gaps persist among rural and marginalized communities. These gaps are attributed to limited outreach efforts, low literacy rates, and a reliance on traditional mechanisms.

4.4. Analyzing the Relationship Between Socio-Demographic Factors and Public Confidence in the Judiciary System

This research examines the connection between socio-demographic factors and the level of public trust in the judicial system.

Table 4 presents Multiple Regression Analysis on Factors Influencing Public Confidence in the Judiciary System. As indicated in

Table 4, all variables related to judicial perception demonstrate a robust positive and statistically significant relationship with public confidence (p < 0.001). The multiple regression analysis assessed the influence of fairness, independence, transparency, accessibility, and enforcement on overall public confidence in the judiciary. The model produced an R-squared value of 1.000, which suggests a perfect fit; however, this likely reflects multicollinearity, given that the confidence index was derived from the same variables employed as predictors. The coefficients for all items related to confidence were positive and statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating that enhanced perceptions of fairness, transparency, and independence are associated with increased public confidence in the judiciary.

Table 5 shows Correlation analysis for association between overall confidence and each item. The correlation analysis presented in

Table 5 reveals strong positive associations between overall confidence in the judiciary and each of the assessed items. The highest correlation is identified with the effective enforcement of judicial decisions (ρ = 0.730), signifying that public confidence is most strongly linked to the perception that court rulings are executed effectively. This finding implies that visible and consistent enforcement substantially enhances trust in the judicial system.

Other items also show substantial positive correlations. Judicial independence from political or clan influence (ρ = 0.699) and fairness and impartiality (ρ = 0.686) are strongly linked to overall trust, highlighting the importance of perceived neutrality and autonomy in building public confidence. Similarly, feeling safe and secure when seeking justice (ρ = 0.677) and belief in the judiciary’s independence (ρ = 0.675) show that citizens’ sense of protection and systemic impartiality play a key role in shaping confidence levels.

The transparency and accessibility of judicial processes (ρ = 0.631) also exhibit a positive, though slightly weaker, correlation, suggesting that while important, these factors may be secondary to enforcement and independence in influencing public trust. Finally, the correlation between the overall confidence statement and the overall index itself (ρ = 0.698) confirms internal consistency in how confidence is measured.

In summary, the data indicates that enforcement, independence, and fairness are the most critical dimensions driving public confidence in the judiciary, with transparency and safety also playing supportive roles.

Table 6 presents Association between Age and Public Confidence in the Judiciary. The Chi-square test was employed to explore the relationship between respondents’ age and their confidence levels in the judiciary system. The results presented in the

Table 6 indicate a statistically significant association between age and public confidence (χ²(10) = 29.73, p = 0.001). This finding suggests that confidence in the judiciary system varies significantly across different age groups. Overall, the results demonstrate that age exerts a notable influence on public confidence in the judiciary, with confidence levels generally increasing with age.

Table 7 Association between Education Level and Public Confidence in the Judiciary. The Chi-square test was conducted to determine whether there is a statistically significant association between respondents’ highest educational attainment and their confidence in the judiciary. The results presented in

Table 7 indicate a significant association between these variables (χ²(12) = 45.61, p = 0.000). Since the p-value is below the conventional threshold of 0.05, this finding suggests that education level significantly influences public trust in the judicial system. In summary, the results imply that as educational attainment increases, so does confidence in the judiciary.

Table 8 presents Relationship between Gender and Public Confidence in the Judiciary. The Chi-square test was employed to examine the relationship between respondents’ gender and their confidence levels in the judiciary system. The results shown in

Table 8 indicate no statistically significant association between gender and public confidence (χ²(2) = 1.3978, p = 0.497), as the p-value surpasses the 0.05 threshold. According to the data, both male and female respondents demonstrated similar confidence patterns regarding the judiciary. Among females, 62 out of 187 (33%) reported high confidence, while 75 out of 213 (35%) of males expressed high confidence. The distribution in the low and moderate confidence categories was also relatively consistent between the genders. These findings suggest that gender does not significantly influence respondents’ perceptions of the judiciary’s fairness, transparency, or effectiveness.

Table 9 Relationship between Working Experience and Public Confidence in the Judiciary.The Chi-square test was performed to assess whether there is a statistically significant association between respondents’ work experience and their confidence in the judiciary system. The results shown in

Table 9 indicate no significant association between these variables (χ²(8) = 8.53, p = 0.384), as the p-value exceeds the 0.05 threshold. As shown in the table, the largest group—respondents with 0–3 years of experience (175 individuals)—exhibited a varied distribution of confidence levels, with 55 expressing high confidence and 72 reporting moderate confidence. Similarly, respondents with extensive experience (13 years or more) displayed relatively balanced views, with 23 indicating high confidence. Overall, the absence of a statistically significant association suggests that the length of work experience does not substantially influence individuals’ perceptions of the judiciary’s fairness, transparency, or effectiveness.

5. Discussion

The study demonstrates that public confidence in the judiciary system in Puntland is significantly influenced by perceptions of fairness, independence, and the effective enforcement of judicial decisions. These findings are consistent with existing studies that underscores the judiciary’s role as a crucial democratic institution in ensuring justice and upholding the rule of law (MUSOKE, 2023). Among the variables examined, the effective enforcement of judicial decisions exhibited the strongest correlation with overall public confidence (ρ = 0.730), suggesting that citizens are more inclined to trust a system capable of reliably implementing its decisions. This finding supports the argument of studies who contend that enforcement is fundamental to judicial legitimacy and a necessary condition for institutional trust (Mytnyk et al., 2020).

Judicial independence also emerged as a significant factor influencing trust, with a correlation coefficient of 0.699. This corroborates the assertions of studies who suggest that judicial independence—particularly from political or clan influence—is essential for fostering confidence in legal institutions. Fairness and impartiality of the judiciary (ρ = 0.686) were similarly critical. These results are supported by the theoretical framework of procedural justice, which emphasizes that citizens are concerned not only with outcomes but also with the fairness of processes (Tyler & Mentovich, 2023).

In terms of socio-demographic factors, education and age showed statistically significant associations with public confidence. Respondents with higher educational attainment reported greater trust in the judiciary, consistent with the findings who note that more educated individuals are often more aware of their rights and the functioning of the legal system. Confidence also tended to increase with age, suggesting that experience and maturity may influence institutional trust nations (Bühlmann & Kunz, 2011). Conversely, gender and work experience were not significantly associated with confidence levels. This aligns with previous studies that found that while demographic factors are relevant, institutional perceptions often play a more dominant role in shaping trust (Sampaio et al., 2014).

6. Conclusions

The study finds that public trust in Puntland’s judiciary is moderate but on the rise. The findings indicate that although people generally perceive the judiciary as fair, independent, and capable, there are still worries about political meddling, interference of clan leaders, the enforcement of decisions, and the availability of information. Institutional attributes like fairness, transparency, and independence play a crucial role in boosting trust, while demographic factors such as gender and experience have a minor impact. Overall, enhancing the judiciary’s institutional performance, particularly in enforcement, transparency, and communication, will be essential for building public trust and maintaining the rule of law in Puntland.

7. Recommendation

Given the findings and analysis demonstrated above, the study suggests the following recommendations:

Enhancing judicial transparency requires better public access to court rulings, legal processes, and institutional data. This can be accomplished by utilizing digital tools like official websites and mobile apps, along with public announcements that keep citizens informed and involved in the judicial process.

Ensuring that court decisions are consistently enforced is crucial for sustaining public confidence. Enhancing cooperation between the judiciary and law enforcement is essential to guarantee that judicial rulings are executed, thereby bolstering the justice system’s credibility and authority.

To overcome geographic and logistical barriers, especially in rural and underserved areas, it is advised to set up mobile courts and regional judicial branches. These efforts can make legal services more accessible to the public and ensure fair access to justice.

Legal literacy programs should be funded by government bodies and civil society groups to enhance public understanding of citizens’ rights and the judicial system’s operations. These programs enable people to engage with the legal system more effectively and uphold their legal rights.

To ensure judicial independence, it is crucial to implement clear policies and oversight mechanisms that prevent interference from political influence and clan-based interests. Maintaining the impartiality of judicial processes is vital for fostering long-term public trust.

Engaging with media outlets can help in promoting accurate and responsible coverage of judicial issues. By enhancing transparency and public comprehension through media channels, the judiciary can bolster its public image and reinforce its perceived legitimacy.

8. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study is characterized by methodological precision and a well-considered design, it is important to recognize several limitations that could affect how the findings are interpreted and their applicability to broader contexts. To begin with, the reliance on convenience sampling for participant selection presents a significant limitation. Although the sample size was statistically calculated using Slovin’s formula and distributed proportionally across the districts of Qardho, Garowe, and Bossaso, the non-random nature of participant selection might have introduced sampling bias. Participants were chosen based on their availability and willingness to take part, potentially excluding certain demographic groups or viewpoints, especially those less accessible or less inclined to discuss judicial matters. Additionally, the study utilized a cross-sectional design, gathering data at a single point in time. This method provides a snapshot of current attitudes and perceptions but does not facilitate the examination of changes over time or causal relationships. Public trust in judicial systems can shift due to political developments, policy changes, or high-profile judicial decisions; therefore, a longitudinal study might have provided more comprehensive insights into these evolving dynamics. Another of the study is its limited geographic focus. By focusing solely on the urban areas of Qardho, Garowe, and Bossaso, the research might not fully represent the views of rural or nomadic populations in Puntland, who could have significantly different experiences and interactions with judicial systems. Consequently, the results may be more indicative of urban settings and less relevant to the broader region.

Building on the results and recognizing the study’s limitations, several avenues for future research are suggested to enhance understanding and address the gaps identified. Due to the study’s focus on the urban areas of Qardho, Garowe, and Bossaso, future research could gain from comparative studies across various regions of Puntland. These studies would shed light on how differences in local governance, the influence of customary law, and regional political dynamics affect public trust in the formal judicial system. This broader comparative approach would improve the generalizability of the findings and offer a more comprehensive national view. Additionally, the cross-sectional design of the current study restricts its ability to observe changes in public trust over time. Therefore, longitudinal research designs are highly recommended. By monitoring public perceptions over months or years, future studies could assess the effectiveness of judicial reforms, changes in institutional performance, and the evolving socio-political landscape. This would not only enhance causal inferences but also assist policymakers in evaluating the long-term effects of initiatives aimed at bolstering judicial legitimacy. Furthermore, the use of convenience sampling in the current study, while practical, limited the representativeness of the data and may have excluded certain voices, especially those from marginalized or less accessible groups. Future research should employ probability-based sampling methods, such as stratified or cluster sampling, to ensure broader inclusion and minimize potential biases. These approaches would enhance the validity and reliability of the findings and enable more equitable representation across demographics and regions.

Author Contributions

Mohamud Isse Yusuf conceptualized the study, designed the research methodology, and led the overall research process. He developed the research instruments, conducted the quantitative data analysis using Stata, and performed the qualitative thematic analysis. He drafted the original manuscript, interpreted the findings, and integrated theoretical and empirical perspectives. He also led the revision process and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission. Mustafe Abdi Ali contributed to the coordination and supervision of data collection, supported the development and refinement of the research tools, and reviewed the entire study. He participated in data validation, contributed to the interpretation of results, and provided critical review and feedback on earlier manuscript drafts. He also supported the organization of tables and figures.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Before participating in the research study, participants were given detailed information about the study and provided their consent to take part. Verbal consent was obtained from each participant prior starting the data collection and the use of verbal consent was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the East Africa University (Qardho campus). Their involvement was completely voluntary, allowing them to opt out at any time without facing any repercussions. There were no connections between the authors or interviewers and the participants that might have affected their participation. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Ethics Review Committee of East Africa University, under the approved study reference number JBAQ/DOFF/12/2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study prior to their participation.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere appreciation to all individuals who contributed to this original research article at any stage.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Albina, T. Essence and content of the judiciary. Modern scientific challenges and trends 2021, 137. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A. (2023). Somalia’s Justice and Corrections Model (JCM): New opportunity or business as usual.

- Atmor, N.; Hofnung, M. Public opinion and public Trust in the Israeli Judiciary. In Judicial Independence: Cornerstone of Democracy; Brill Nijhoff, 2024; pp. 183–203. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın Çakır, A.; Şekercioğlu, E. Public confidence in the judiciary: the interaction between political awareness and level of democracy. Democratization 2016, 23(4), 634–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, C. What is transparency? Public Integrity 2009, 11(4), 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berebon, C. The Judiciary’s Role in Protecting the Rule of Law: A Reassessment of Nigeria’s Legal System; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, F. D. Legitimizing the judiciary: A multilevel explanation of factors influencing public confidence in Asian court systems. Asian Journal of Criminology 2020, 15(4), 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühlmann, M.; Kunz, R. Confidence in the judiciary: Comparing the independence and legitimacy of judicial systems. West European Politics 2011, 34(2), 317–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlea, A. S.; Popa, I. Legitimacy theory. Encyclopedia of corporate social responsibility 2013, 21(6), 1579–1584. [Google Scholar]

- Codrea, L. A. THE USE OF THE TERMS ‘EFFICIENCY’AND ‘EFFECTIVENESS’WITH REGARD TO JUDICIAL SYSTEMS. A DEMAND FOR ACCURACY. READING MULTICULTURALISM: HUMAN AND SOCIAL PERSPECTIVES 2021, 104. [Google Scholar]

- da Silveira Bueno, R. D. L.; Sampaio, J. O.; Cunha, L. G. (2015). Trust in the Judicial System: Evidence from Brazil.

- Danaee Fard, H.; Anvary Rostamy, A. A. Promoting public trust in public organizations: Explaining the role of public accountability. Public Organization Review 2007, 7(4), 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhey, J.; Newton, K. Who trusts?: The origins of social trust in seven societies. European societies 2003, 5(2), 93–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferejohn, J. Independent judges, dependent judiciary: explaining judicial independence. S. Cal. L. Rev. 1998, 72, 353. [Google Scholar]

- Garoupa, N.; Magalhães, P. C. Public trust in the European legal systems: independence, accountability and awareness. West European Politics 2020, 44(3), 690–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindasamy, P. (2024). Citizens’ perceptions of trust and corruption in government institutions in South Africa.

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S.; Klijn, A. The effects of judicial transparency on public trust: Evidence from a field experiment. Public Administration 2015, 93(4), 995–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, I. (2013). The role of the judiciary in the administration of justice in Somaliland judicial system.

- Irfan, M. I. M. (2017). Citizens’ trust in public institutions in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh: A comparative study. In.

- Jalal, M. S.; Hasan, M. A.; Akter, M. Public confidence towards judiciary court: An empirical study in Bangladesh. International Journal of Emerging Trends in Social Sciences 2024, 17(2), 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasurya, G. (2010). Judicial Accountability and Judicial Transparency: Challenges to Indian Judiciary. Available at SSRN 1601846.

- Kamusiime, B. (2014). Challenges Facing the Judiciary in Uganda.

- Kulmie, D. A. (2025). Assessing the Effectiveness of Somali Courts in Anti-Corruption Cases: A Public Perception and Confidence Analysis.

- Lakho, M. K.; Fazal, A.; Sultan, R. S.; Hyder, S.; Lakho, R. A. An Exploration of Sociodemographic Determinants to Accessing Justice from a Socio-legal Approach. Qlantic Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 2024, 5(4), 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawor, M. J.; Querijero, N. J. V. B.; Atienza, V. A.; Cortes, D. T. Assessing the Level of Public Trust: Ninth Judicial Circuit Court in Gbarnga, Bong County, Liberia. HOLISTICA Journal of Business and Public Administration 2025, 16(1), 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, K.; Anleu, S. R.; Tutton, J. The judiciary and the public: Judicial perceptions. Adelaide Law Review, The 2018, 39(1), 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, M. A. Barriers to Justice: Investigating the Personal and Professional Challenges Faced by Judges and Lawyers in Somalia: A Case Study in Puntland. Law and Policy 2025, 10(1), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MUSOKE, G. P. (2023). CASE BACKLOG IN UGANDA, IT’S IMPACT ON JUSTICE AND THE POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS THERETO.

- Mytnyk, A. A.; Syrota, D. I.; Slobodianyk, T. M.; Loktionova, V. V.; Pleskun, O. V. Ensuring enforcement of judgements through the prism of reforming criminal provisions. International Journal of Criminology and Sociology 2020, 9(0536), 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndulo, M. Judicial reform, constitutionalism and the rule of law in Zambia: From a justice system to a just system. Zambia Social Science Journal 2011, 2(1), 3. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamwasa, K.; Karegeya, P.; Rudasingwa, T.; Gahima, G. Rwanda briefing; Rwanda National Congress, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Odhiambo, B. (2025). Analysing Challenges and Legal Reforms in Kenya’s Judiciary. Available at SSRN 5343248.

- Ogari, C. K. Factors influencing implementation of Judiciary System projects in Kenya: A case of the Judiciary transformation framework; University of Nairobi, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Okafor, C. O.; Chienweze, U. C.; Abu, H. S.; Umoh, N. R. Democracy and Perceived Public Confidence in The Judiciary: Roles of Socio-Economy and Gender. African Research Review 2020, 14(1), 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A. K. (2021). INTERNATIONAL LAW AND ITS APPLICABILITY IN THE SOMALIA’S LEGAL SYSTEM.

- Rasmussen, M. The origins of a legal revolution–The early history of the European Court of Justice. JEIH Journal of European Integration History 2008, 14(2), 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Figueroa, J. Judicial independence: Definition, measurement, and its effects on corruption. An analysis of Latin America; New York University, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, J. O.; De-Losso, R.; Cunha, L. G. (2014). Confidence in the Judicial System and Court Experience: Evidence from Brazil. Available at SSRN 2470150.

- Sastry, T. (2016). Access to justice and judicial pendency: confluence of juristic crisis. available at: researchgate. net.

- Tyler, T. R.; Mentovich, A. Procedural justice theory. Legal Epidemiology: Theory and Methods 2023, 99. [Google Scholar]

- Vickrey, W. C.; Dunn, J. L.; Kelso, J. C. Access to justice: A broader perspective. Loy. LAL Rev. 2008, 42, 1147. [Google Scholar]

- Voermans, W. Judicial transparency furthering public accountability for new judiciaries. Utrecht Law Review 2007, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, J. P.; Bowler, S.; Lanoue, D. J. The sources of public confidence in state courts: Experience and institutions. American Politics Research 2003, 31(2), 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents.

| Variable |

N |

% |

| Age |

20—25

26-30

31--35

36-40

41—50

51 and above |

112

90

65

63

49

21 |

28%

22.50%

16.25%

15.75%

12.25%

5.25% |

| Gender |

Male

Female |

213

187 |

53.25%

46.75% |

| Level of education of the respondents |

Masters

Bachelor

Diploma

Secondary level

Primary

PHD

Illiterate |

43

148

63

53

20

11

62 |

10.75%

37%

15.75%

13.25%

5%

2.75%

15.5% |

| Experience of the respondents. |

0-3 yrs.

4-6 yrs.

7-9 yrs.

10--12 yrs.

13 years and above |

175

93

54

25

53 |

43.75%

23.25%

13.5%

6.25%

13.25% |

| Marital status of the respondents. |

Married

Single

Divorced

Widowed |

194

148

47

11 |

48.50%

37%

11.75%

2.75% |

Occupation of the respondents. Private sector staff 85 21.15%

Public sector staff 43 10.75%

Self-employed. 138 34.5%

Student. 56 14%

Unemployed. 78 19.5% |

Table 3.

The overall level of public confidence in the judiciary system.

Table 3.

The overall level of public confidence in the judiciary system.

| Factors |

Strongly agree |

Agreed |

Strongly disagree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

| I believe the judiciary system is fair and impartial. |

35 |

213 |

27 |

57 |

59 |

| 8.75% |

53.25% |

6.75% |

14.25% |

14.75% |

| I feel safe and secure when seeking justice through the courts. |

70 |

201 |

27 |

54 |

48 |

| 17.5% |

50.25% |

6.75% |

13.5% |

12% |

| I have confidence in the independence of judges from political or clan influence. |

45 |

176 |

27 |

69 |

83 |

| 11.25% |

44% |

6.75% |

17.25% |

20.75% |

| I trust that judicial decisions are enforced effectively and without favouritism. |

58 |

196 |

32 |

55 |

59 |

| 14.5% |

49% |

8% |

13.75% |

14.75% |

| Judiciary processes are transparent and allow citizens to access information easily. |

44

11% |

206

51.5% |

20

5% |

73

18.25% |

57

14.25% |

| I believe that the judiciary is truly independent from political influence. |

66

16.50% |

187

46.75% |

20

5% |

53

13.25% |

74

18.50% |

| Judiciary processes are transparent and allow citizens to access information easily. |

44 |

206 |

20 |

73

18.25% |

57 |

| 11% |

51.50% |

5% |

|

14.25% |

Table 4.

Summary of Multiple Regression Analysis on Factors Influencing Public Confidence in the Judiciary System.

Table 4.

Summary of Multiple Regression Analysis on Factors Influencing Public Confidence in the Judiciary System.

| Variable |

Coefficient (B) |

P-Value |

| Fairness & Impartiality. |

0.143 |

<0.001 |

| Safety & Security. |

0.143 |

<0.001 |

| Independence of Judges. |

0.143 |

<0.001 |

| Effective Enforcement. |

0.143 |

<0.001 |

| Transparency & Accessibility. |

0.143 |

<0.001 |

| Institutional Independence. |

0.143 |

<0.001 |

| Overall Confidence Item. |

0.143 |

<0.001 |

Table 5.

Correlation analysis for association between overall confidence and each item.

Table 5.

Correlation analysis for association between overall confidence and each item.

| Variables. |

Correlation (ρ) |

| Fairness & impartiality of the judiciary. |

0.686 |

| Feeling safe and secure when seeking justice. |

0.677 |

| Independence of judges from political/clan influence. |

0.699 |

| Effective enforcement of judicial decisions. |

0.730 |

| Transparency and accessibility of judicial processes. |

0.631 |

| Belief in the judiciary’s independence from political influence. |

0.675 |

| Overall confidence statement. |

0.698 |

Table 6.

Association between Age and Public Confidence in the Judiciary.

Table 6.

Association between Age and Public Confidence in the Judiciary.

| Age Group |

Low Confidence |

Moderate Confidence |

High Confidence |

Total |

| 20–25 years |

34 |

47 |

31 |

112 |

| 26–30 years |

21 |

39 |

30 |

90 |

| 31–35 years |

12 |

31 |

22 |

65 |

| 36–40 years |

11 |

36 |

16 |

63 |

| 41–50 years |

9 |

18 |

22 |

49 |

| 51 years & above |

3 |

2 |

16 |

21 |

| Total |

90 |

173 |

137 |

400 |

| Pearson Chi-square (χ²) = 29.73, p-value = 0.001. |

Table 7.

Association between Education Level and Public Confidence in the Judiciary.

Table 7.

Association between Education Level and Public Confidence in the Judiciary.

| Education Level |

Low Confidence |

Moderate Confidence |

High Confidence |

Total |

| Bachelor’s degree |

39 |

68 |

41 |

148 |

| Diploma |

11 |

28 |

24 |

63 |

| Illiterate |

18 |

17 |

27 |

62 |

| Master’s Degree |

3 |

19 |

21 |

43 |

| PhD |

0 |

1 |

10 |

11 |

| Primary |

4 |

15 |

1 |

20 |

| Secondary |

15 |

25 |

13 |

53 |

| Total |

90 |

173 |

137 |

400 |

| Pearson Chi-square (χ²) = 45.61, p-value = 0.000. |

Table 8.

Relationship between Gender and Public Confidence in the Judiciary.

Table 8.

Relationship between Gender and Public Confidence in the Judiciary.

| Gender |

Low Confidence |

Moderate Confidence |

High Confidence |

Total |

| Female |

47 |

78 |

62 |

187 |

| Male |

43 |

95 |

75 |

213 |

| Total |

90 |

173 |

137 |

400 |

| Pearson Chi-square (χ²) = 1.3978, p-value = 0.497. |

Table 9.

Relationship between Working Experience and Public Confidence in the Judiciary.

Table 9.

Relationship between Working Experience and Public Confidence in the Judiciary.

| Working Experience |

Low Confidence |

Moderate Confidence |

High Confidence |

Total |

| 0–3 years |

48 |

72 |

55 |

175 |

| 4–6 years |

18 |

40 |

35 |

93 |

| 7–9 years |

13 |

26 |

15 |

54 |

| 10–12 years |

3 |

13 |

9 |

25 |