1. Introduction

Ultrafast fiber lasers deliver femtosecond-to-picosecond pulses and support a wide range of high-precision photonic tasks, including material processing, nonlinear diagnostics, and biophotonic measurements [

1,

2,

3]. Among various techniques, passive mode locking remains the most practical route to stable ultrashort pulse generation, where the saturable absorber (SA) governs pulse initiation and sustains steady pulse evolution in the cavity [

4,

5,

6]. In recent years, nanomaterial SAs—especially quantum dots (QDs)—have attracted extensive interest because their optical response can be engineered through bandgap tunability, they exhibit intrinsically fast carrier dynamics, and they can be packaged in compact fiber-compatible formats [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Despite these merits, many colloidal QDs (e.g., PbSe and PbS) possess reactive surfaces and defect-associated trap states [

11]. Under continuous optical pumping, such surface-related effects can accelerate oxidation and induce aggregation, which weakens the nonlinear absorption response and undermines long-term operational stability, thereby limiting their use in reliable ultrafast laser platforms. Ultrafast fiber lasers deliver femtosecond-to-picosecond pulses and support a wide range of high-precision photonic tasks, including material processing, nonlinear diagnostics, and biophotonic measurements [

1,

2,

3]. Among various techniques, passive mode locking remains the most practical route to stable ultrashort pulse generation, where the saturable absorber (SA) governs pulse initiation and sustains steady pulse evolution in the cavity [

4,

5,

6]. In recent years, nanomaterial SAs—especially quantum dots (QDs)—have attracted extensive interest because their optical response can be engineered through bandgap tunability, they exhibit intrinsically fast carrier dynamics, and they can be packaged in compact fiber-compatible formats [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Despite these merits, many colloidal QDs (e.g., PbSe and PbS) possess reactive surfaces and defect-associated trap states [

11]. Under continuous optical pumping, such surface-related effects can accelerate oxidation and induce aggregation, which weakens the nonlinear absorption response and undermines long-term operational stability, thereby limiting their use in reliable ultrafast laser platforms.

Inorganic surface passivation via overcoating has therefore been explored to mitigate surface-driven degradation, leading to overcoated or heterostructured QD SAs [

12,

13,

14]. Introducing an overcoating layer can reduce trap-assisted loss, slow chemical deterioration, and improve optical robustness, which is beneficial for stable saturable absorption. Nevertheless, even for heterostructured QD systems such as PbS/CdS and InP/ZnSeS/ZnS, practical challenges remain in power handling, environmental durability, and self-starting operation at low pump thresholds [

15,

16]. These considerations motivate the development of QD-based SAs that can simultaneously provide low saturation intensity, strong damage tolerance, and long-duration stability in fiber laser cavities.

PbSe/PbS is a favorable material combination for improving QD-SA durability. PbSe and PbS share the rock-salt lattice and exhibit minimal mismatch, which facilitates PbS overcoating on PbSe and helps suppress defect formation at the PbSe-PbS interface [

17,

18]. In addition, the PbS overcoating can act as a protective barrier against oxygen and moisture, while its thermal characteristics may assist heat dissipation under intense intracavity irradiation [

19,

20]. Combined with the broad bandgap tunability and large exciton Bohr radius of PbSe [

21], PbS-overcoated PbSe (denoted as PbSe/PbS) QDs are promising for achieving effective saturable absorption with enhanced operational stability [

22,

23].

Here we fabricate a freestanding PbSe/PbS QD-polystyrene (PS) composite SA film and implement it in a bidirectionally pumped erbium-doped fiber laser operating in the anomalous-dispersion regime. The composite film exhibits a saturation intensity of 5.76 kW·cm-2, a modulation depth of 33%, and an optical damage threshold of 13.6 mJ·cm-2. Using this device, self-starting soliton mode locking is realized at a total pump threshold of 6 mW, producing 1.06 ps pulses with a radio-frequency signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of ~65 dB. Moreover, the spectra show no observable degradation over six months, indicating strong environmental and operational durability.

2. Synthesis and Characterization

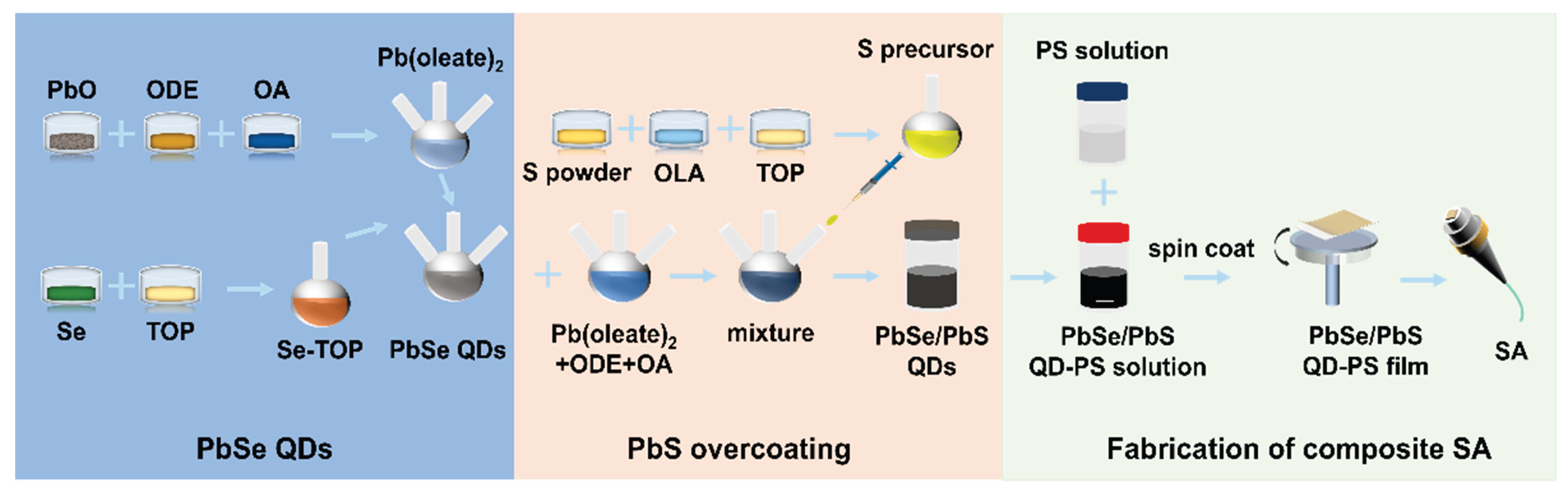

The preparation of PbSe QDs, subsequent PbS overcoating to obtain PbSe/PbS QDs, and fabrication of the freestanding QD-PS composite SA film are summarized in

Figure 1. PbO (1 mmol, 90%, Sinopharm) was first dehydrated under vacuum at 120 °C for 20 min. After adding 1-octadecene (20 mL, ODE, 90%, Sigma-Aldrich) and oleic acid (2 mmol, OA, 90%, Alfa Aesar), the mixture was maintained at 110 °C for 2 h under nitrogen to form Pb(oleate)

2. In parallel, Se powder (1 mmol, 99.5%, Alfa Aesar) was dissolved in trioctylphosphine (5 mL, TOP, 90%, Sinopharm) and heated at 120 °C for 15 min to yield the Se-TOP precursor. The Se-TOP solution was then injected rapidly into the Pb(oleate)

2 solution with vigorous stirring. After a 5-min growth period, the reaction was quenched in an ice bath. The obtained PbSe QDs were purified by centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 10 min) and redispersed in 10 mL ODE containing 1 mmol OA.

PbS overcoating was performed by adding Pb(oleate)2 (0.25 mmol), ODE (5 mL), and OA (0.5 mmol) to the purified PbSe dispersion and holding the mixture at 120 °C. The sulfur precursor was prepared by dissolving S powder (0.2 mmol, 99.5%, Alfa Aesar) in oleylamine (2 mL, OLA, 90%, Sigma-Aldrich) and then mixing with TOP (2.5 mL). The mixture was ultrasonicated until complete dissolution. This sulfur precursor was injected at 2 mL·min-1, allowed to react for 5 min, and then the solution was rapidly cooled to room temperature. The resulting PbSe/PbS QDs were further purified by centrifugation.

To fabricate the freestanding SA film, PS (1 g, Macklin) was dissolved in toluene (10 mL, Sinopharm) and ultrasonicated (40 kHz, 15 min) to obtain a 100 mg·mL-1 PS solution. The PbSe/PbS QD dispersion was mixed with the PS solution at a 1:1 volume ratio and sonicated (100 W, 20 min) to form a uniform QD-PS composite ink. The ink was spin-coated onto a quartz substrate; after solvent evaporation, the film was peeled off and transferred onto the end face of an FC/PC connector, forming an all-fiber SA device.

Figure 2a compares the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of PbSe, PbS, and PbSe/PbS QDs. Relative to the individual PbSe and PbS samples, the PbSe/PbS QDs exhibit broader diffraction peaks (larger FWHM), which suggests increased microstrain and/or a reduced coherence length after PbS overcoating. Such peak broadening is consistent with structural modification and strain accommodation associated with introducing PbS onto the PbSe QD surface and forming a PbSe-PbS interface [

18]. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images (

Figure 2(b) and

Figure 2(c)) show nearly spherical nanoparticles with narrow size distributions. The mean diameter increases from 3.5 ± 0.5 nm (PbSe) to 4.5 ± 0.5 nm (PbSe/PbS), corresponding to an average size increase of ~1.0 nm. Under the simplifying assumption of isotropic radial growth during overcoating, this size change corresponds to an effective overcoating thickness of ~0.5 nm. High-resolution TEM (HR-TEM) further reveals clear lattice fringes [

24]. For PbSe, a lattice spacing of 0.216 nm is assigned to the (220) plane. In the PbSe/PbS sample, a lattice spacing of 0.152 nm is observed and attributed to the PbS (400) plane; this value is slightly larger than the bulk PbS spacing of 0.1485 nm, implying tensile strain in PbS-related domains that may originate from lattice accommodation at the PbSe-PbS interface [

25].

Figure 2d shows the absorption spectra of PbSe and PbSe/PbS QDs. After PbS overcoating, an excitonic feature appears near 1530 nm and the absorption edge becomes steeper compared with PbSe, indicating reduced energetic disorder and improved surface passivation, which is plausibly associated with the PbS overcoating process [

26]. Taken together, the XRD, TEM/HR-TEM, and optical absorption results support the successful introduction of PbS onto PbSe QDs and the formation of PbSe/PbS QDs. Future work will employ spatially resolved compositional analysis (e.g., STEM-EDS/EELS) to further clarify the radial composition distribution.

Figure 2e presents the nonlinear transmission of the PbSe/PbS QD-PS composite SA film, which is fitted using a two-level SA model [

4]:

Here,

I denotes the incident intensity, Δ

T is the modulation depth,

Isat is the saturation intensity, and

Tns represents nonsaturable loss. The fitting yields Δ

T = 33%,

Isat = 5.76 kW cm

-2, and

Tns = 8%, confirming a pronounced saturable-absorption response from the composite film. The inset of

Figure 2e shows a photograph of the uniform freestanding PbSe/PbS QD-PS composite film used for direct fiber-connector integration.

3. Mode-Locked Fiber Laser

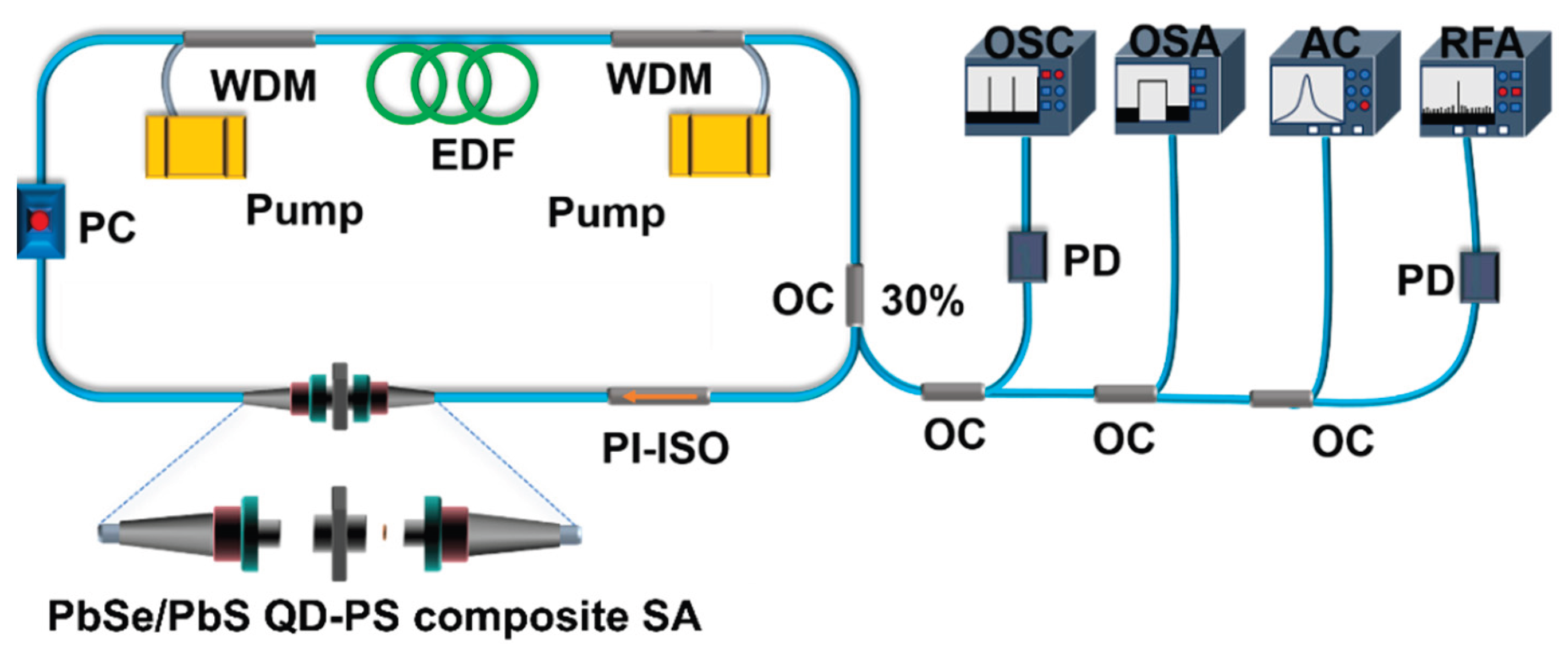

Figure 3 shows the all-fiber ring cavity used to evaluate the freestanding PbSe/PbS QD-PS composite SA. The cavity length is 33.9 m, comprising 4.6 m erbium-doped fiber (EDF, EDFC-980-HP; absorption coefficient: 6 dB/m) and 29.3 m standard single-mode fiber (SMF-28), which yields a net anomalous group-velocity dispersion of -0.54 ps

2. Two 980-nm laser diodes (LDs) provide bidirectional pumping via 980/1550-nm wavelength-division multiplexers (WDMs). A polarization-insensitive isolator (PI-ISO) enforces unidirectional lasing, while a polarization controller (PC) is used to access and optimize the mode-locked state. The freestanding PbSe/PbS QD-PS film is sandwiched between two FC/PC connectors, enabling connector-level integration without free-space alignment. Laser output is extracted through a 70:30 optical coupler (OC). The output characteristics are measured using an optical spectrum analyzer (OSA, Yokogawa AQ6370D), an autocorrelator (AC, APE PulseCheck SM1600), a digital oscilloscope (OSC, RIGOL DS4050), and a radio-frequency spectrum analyzer (RFA, Rohde & Schwarz FSV30).

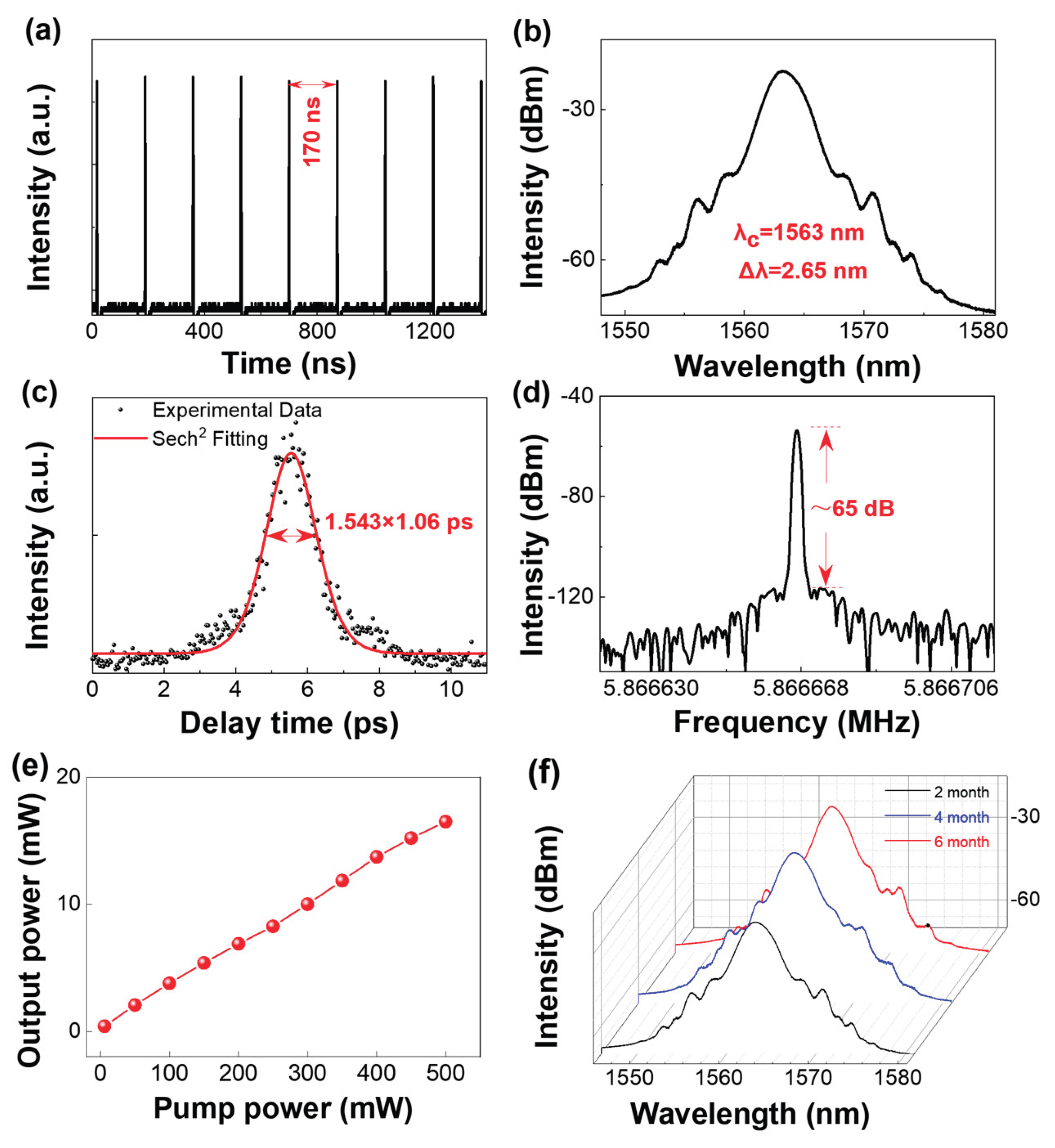

With the composite SA inserted, self-starting mode locking is obtained at a total pump power of 6 mW with

Pf =

Pb = 3 mW. The oscilloscope trace in

Figure 4a shows a pulse-to-pulse spacing of 170 ns, corresponding to a repetition rate of ~5.86 MHz, consistent with the 33.9-m cavity length. The spectrum (

Figure 4b) is centered at 1563 nm and features clear Kelly sidebands, indicating soliton operation in the anomalous-dispersion regime. From the autocorrelation trace (

Figure 4c), the pulse width is 1.06 ps assuming a sech

2 profile. Using the measured 3-dB bandwidth of 2.65 nm, the time-bandwidth product is 0.345, close to the transform-limited value of 0.315 for sech

2 pulses, suggesting only weak residual chirp [

27]. The RF spectrum (

Figure 4d) presents a distinct fundamental peak at 5.86 MHz with an SNR of ~65 dB (RBW = 100 Hz), supporting stable mode-locked operation. When the bidirectional pumps are increased to

Pf =

Pb = 250 mW, the average output power rises nearly linearly to 17 mW (

Figure 4e), demonstrating that the SA device maintains effective operation over the tested pump range. Under 5.86 MHz repetition-rate conditions, the optical damage threshold of the PbSe/PbS QD-PS composite SA is 13.6 mJ·cm

-2, indicating strong optical robustness. Long-term stability is assessed by tracking the spectra for six months; as shown in

Figure 4f, the spectral envelope and bandwidth remain essentially unchanged, confirming good environmental and operational durability.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Low-threshold initiation and long-term stability in mode-locked fiber lasers are primarily influenced by two factors: (i) the distribution of gain along the active fiber and (ii) the ability of the SA to provide nonlinear loss modulation without degradation. In our system, both aspects are effectively addressed by integrating bidirectional pumping with a freestanding PbSe/PbS QD-PS composite SA. In relatively long EDF cavities, a highly nonuniform inversion profile can increase the intracavity intensity required for self-starting operation. By introducing the 980-nm pump from both ends of the cavity, this nonuniformity is mitigated, leading to a more uniform gain distribution, which lowers the intensity threshold for initiating mode-locking. Combined with the low saturation intensity of the composite SA, this approach to gain management allows for self-starting soliton mode-locking at a pump threshold as low as 6 mW.

The observed stability and power tolerance of the SA are likely due to the PbS overcoating on PbSe and the polymer-based composite film. The PbS overcoating is anticipated to reduce trap-assisted losses and slow oxidation processes, which is consistent with the large modulation depth and the absence of significant spectral drift over six months. Additionally, the composite film maintains an optical damage threshold of 13.6 mJ·cm-2 and exhibits near-linear output power scaling up to 17 mW without visible degradation, demonstrating robust all-fiber operation under the tested conditions. From a practical perspective, the freestanding film also enables easy connector-level integration, making it a suitable solution for compact ultrafast systems that require reliable, long-term performance.

In summary, a freestanding PbSe/PbS QD-PS composite SA is realized and implemented in a bidirectionally pumped erbium-doped fiber laser operating in the anomalous-dispersion regime. Self-starting soliton mode locking is achieved at 6 mW total pump power, producing 1.06 ps pulses with an RF SNR of ~65 dB. The SA combines low saturation intensity (5.76 kW·cm-2), strong modulation (33%), high damage tolerance (13.6 mJ·cm-2), and stable spectra over six months, providing a practical and scalable route toward low-threshold, durable ultrafast fiber lasers.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61905118) and Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications (Grant No. NY218023).

Data Availability Statement

The data is available on the request from corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fermann, M.; Hartl, I. Ultrafast fibre lasers. Nat. Photonics 2013, 7, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Liu, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Liu, W. Research progress of passively mode-locked fiber lasers based on saturable absorbers. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Z.; Ju, Z.; Ren, L.; Wang, X.; Malomed, B.; Dai, C. Polarization-induced buildup and switching mechanisms for soliton molecules composed of noise-like-pulse transition states. Laser Photonics Rev. 2025, 19, 2401019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, F.; Lu, J.; Ye, S.; Guo, H.; Nie, H.; Zhang, J.; He, J.; Zhang, B.; Ni, Z. High output mode-locked laser empowered by defect regulation in 2D Bi2O2Se saturable absorber. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Gao, B.; Wen, H.; Ma, C.; Huo, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, Q.; Wu, G.; Liu, L. Pure-high-even-order dispersion bound solitons complexes in ultra-fast fiber lasers. Light Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emelianov, A.; Pettersson, M.; Bobrinetskiy, I. Ultrafast laser processing of 2D materials: novel routes to advanced devices. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2402907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Li, H.; Gan, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, W.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, X.; Shi, Y.; Liu, J.; Wen, Q.; Zhang, H. Zero-dimensional MXene-based optical devices for ultrafast and ultranarrow photonics applications. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2002209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, F.; Gan, Y.; Ji, L.; Wei, Q. MXene quantum dot synthesis, optical properties, and ultra-narrow photonics: a comparison of various sizes and concentrations. Laser Photonics Rev. 2021, 15, 2100059. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Qiao, J.; Cheng, P.; Saleque, A.; Hossain, M.; Zeng, L.; Zhao, J.; Qarony, W.; Tsang, Y. Tin telluride quantum dots as a novel saturable absorber for Q-switching and mode locking in fiber lasers. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2021, 9, 2001821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Tao, L.; Zhao, Y.; He, J.; Huang, L.; Yang, Y. Ti3C2Tx quantum dots/polyvinyl alcohol films as an enhanced long-term stable saturable absorber device for ultrafast photonics. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 17684–17694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, O.; Zhao, J.; Chauhan, V.; Cui, J.; Wong, C.; Harris, D.; Wei, H.; Han, H.; Fukumura, D.; Jain, R.; Bawendi, M. Compact high-quality CdSe-CdS core-shell nanocrystals with narrow emission linewidths and suppressed blinking. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, H.; Kang, S.; Heo, J.; Choi, S.; Kim, R.; Kim, K.; Ahn, N.; Yoon, Y.; Lee, T.; Chang, J.; Lee, K.; Park, Y.; Park, J. Insights into structural defect formation in individual InP/ZnSe/ZnS quantum dots under UV oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Kamath, A.; Guyot-Sionnest, P. Mid-infrared cascade intraband electroluminescence with HgSe-CdSe core-shell colloidal quantum dots. Nat. Photonics 2023, 17, 1042–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selopal, G.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Z.; Rosei, F. Core/shell quantum dots solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1908762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, F.; Gong, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, Z.; Shen, H.; Chen, S. Generation of Q-switched and mode-locked pulses based on PbS/CdS saturable absorbers in an Er-doped fiber laser. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 5956–5961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; He, P.; Ge, B.; Duan, X.; Hu, L.; Zhang, X.; Tao, L.; Zhang, X. InP/ZnSeS/ZnS core-shell quantum dots as novel saturable absorbers in mode-locked fiber lasers. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2023, 11, 2201939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin-Brusilovski, A.; Jang, Y.; Shapiro, A.; Safran, A.; Sashchiuk, A.; Lifshitz, E. Influence of interfacial strain on optical properties of PbSe/PbS colloidal quantum dots. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 9056–9063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Song, J.; Jang, J.; Mai, X.; Kim, S.; Jeong, S. High performance of PbSe/PbS core/shell quantum dot heterojunction solar cells: short circuit current enhancement without loss of open circuit voltage by shell thickness control. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 17473–17481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, M.; Guyot-Sionnest, P. Synthesis and characterization of strongly luminescing ZnS-capped CdSe nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 468–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, J.; Parker, S.; Togo, A.; Tanaka, I.; Walsh, A. Thermal physics of the lead chalcogenides PbS, PbSe, and PbTe from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 205203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lou, Y.; Samia, A.; Burda, C. Coherency strain effects on the optical response of core/shell heteronanostructures. Nano Lett. 2003, 3, 799–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Fan, S.; Chen, Q.; Lai, X. Passively mode-locked Yb fiber laser with PbSe colloidal quantum dots as saturable absorber. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 24901–24906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, L.; Ding, C.; Ding, Y.; Han, D.; Zhang, J.; Cui, H.; Wang, Z.; Yu, K. High-power mode-locked fiber laser using lead sulfide quantum dots saturable absorber. J. Lightw. Technol. 2022, 40, 7901–7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zherebetskyy, D.; Scheele, M.; Zhang, Y.; Bronstein, N.; Thompson, C.; Britt, D.; Salmeron, M.; Alivisatos, P.; Wang, L. Hydroxylation of the surface of PbS nanocrystals passivated with oleic acid. Science 2014, 344, 1380–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beek, W.; Wienk, M.; Janssen, R. Hybrid solar cells from regioregular polythiophene and ZnO nanoparticles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2006, 16, 1112–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbach, F. The long-wavelength edge of photographic sensitivity and of the electronic absorption of solids. Phys. Rev. 1953, 92, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, G. P. Nonlinear Fiber Optics, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, 2001. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).