1. Introduction

Depression is one of the most common and prevalent mental disorders, imposing high disease burden on affected individuals [

1]. During the last decades, depression rates have been steadily increasing in adult and younger age groups [

2,

3] and there are many reasons to consider depression prevention and treatment as a primary mental health concern. Meantime, there are more than 200 studies examining the efficacy of various psychological treatments for depression. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is one of the most widely researched treatments for clinical depression and there is a great body of evidence for its efficacy and effectiveness [

4]. Guided by empirical research, CBT focuses on teaching patients to modify their dysfunctional patterns in cognitions (e.g., thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes), behaviors, and emotional regulation [

5] and then giving patients skills to reduce the risk of subsequent relapse. In accordance with the current state of traditional treatments for people with depression, CBT is based on a so-called deficit-oriented model of psychotherapy where treatment is primarily concentrated on psychopathology, deficits and dysfunctionality in thoughts, emotions and behaviors. Establishing psychological resources has traditionally not been the focus of this kind of psychotherapy [

6]. Within Positive Psychology, however, mental health is conceptualized as not just the absence of symptoms but also the presence of positive feelings including well-being. Over the past decade, the advent of Positive Psychology has yielded a lot of positive psychology interventions (PPIs) that is “[…] treatment methods or intentional activities that aim to cultivate positive feelings, behaviours or cognitions” ([

7], p. 468) which are a promising approach to increasing well-being and satisfaction with life.

Positive Psychotherapy (PPT) is an alternative therapeutic approach based on the fundamental principles of positive psychology. Unlike standard interventions for depression, it assumes that effective treatment of the disorder does not require a focus on negative symptoms, but rather on directly building resources, strengths and well-being [

6]. The PPT protocol comprises 15 empirically validated practices organized into a cohesive treatment program primarily based on Seligman's [

8] PERMA model of well-being.

For PPT as a manualized treatment protocol [

9], there are 20 studies demonstrating its effectiveness for enhancing well-being and reducing depressive symptoms compared to control or pre-treatment scores with medium to large effect sizes (for a summary see [

9]). These studies have been conducted internationally and have addressed a variety of clinical populations, most of them in the group therapy format. Four of these studies have directly compared PPT with two well-established and well-researched treatments, Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) and CBT. PPT was found to perform at least equally well or exceed the other treatments, particularly on well-being measures [

10,

11,

12].

Research, however, does not yet contain many studies that have directly examined follow-up outcome of any form of PPT [

13]. Initially, group PPT was validated with 21 college students with mild to moderate depression, resulting in significantly fewer depressive symptoms compared to a control group that did not receive any intervention. This improvement remained stable for at least one year ([

6], Study 1). Another study by Parks-Sheiner [

14] compared 52 individuals who completed six PPT exercises online with a no-treatment control group of 69 individuals, resulting in lower levels of depression at the three- and six-month follow-ups. Similarly, Lü and Liu [

15] compared a group PPT intervention (n = 16) with a no-treatment control group (n = 18) and explored the impact of positive affect on vagal tone when handling environmental challenges. PPT led to lower depression scores post-intervention that lasted for up to six months. Furthermore, Shoshani and Steinmetz [

16] conducted a study in which they compared a school programme involving PPT (n = 537) with a no-treatment control group (n = 501). After a two-year follow-up, students who participated in the PPT programme showed significant reductions in general distress, anxiety and depressive symptoms, as well as notable improvements in self-esteem, self-efficacy and optimism. In another study, Ochoa et al. [

12] assigned 126 consecutive female survivors of breast cancer with high levels of emotional distress to a group PPT programme for cancer or to a waiting list control group. The PPT group obtained significantly better results after treatment than the control group, showing reduced distress, decreased post-traumatic symptoms and increased post-traumatic growth. These gains were found to be sustainable for up to three and 12 months. Furchtlehner et al. [

17] conducted a randomised controlled trial comparing group PPT (n = 46) and CBT (n = 46) for individuals with depressive disorder, examining reductions in depressive symptoms and increases in happiness. PPT showed consistently moderate to high within- and between-group effect sizes compared to CBT, resulting in a higher remission rate of depression. Regarding feelings of happiness, PPT produced significantly higher scores on all outcome measures, with medium to large effect sizes, compared to CBT. These outcomes remained stable for up to six months for PPT, in contrast to CBT.

Investigating the long-term effects of positive psychotherapy (PPT), as reflected in an 18-month follow-up, is essential for understanding how psychological interventions contribute to lasting and sustainable improvements in well-being. Long-term outcomes also deepen our understanding of how therapeutic changes unfold over time, extending beyond the immediate relief of symptoms. Demonstrating long-term effectiveness would further support the allocation of time and resources to psychotherapy at a policy level. Therefore, examining the long-term effects of PPT is not only important from a methodological perspective, but also central to the field's claims about the sustainable promotion of mental health.

1.1. Aims and Research Questions

Studies on PPT outcome report decreases in negative affect and symptoms and increases in well-being that are sustainable for up to 12 months. However, research literature on the long-term outcomes of PPT is scarce, and further research is needed to expand on existing results to draw more profound conclusions. Moreover, the sample size of existing studies concerning long-term outcomes is rather small, so studies with larger sample sizes are required. As there are no prior studies on the long-term effects of PPT among individuals in Central Europe, this study focuses on a large sample of Austrian individuals with depressive disorders. Access to psychotherapeutic care in Central Europe is organised through public healthcare systems and is partly free. This is particularly relevant in this context, as the frequency and duration of access to therapy can influence its long-term effects.

The aim of the present study was to extend knowledge of the long-term clinical effectiveness of PPT versus CBT in reducing depressive as well as general psychological symptoms, and in enhancing positive feelings of happiness, in individuals with depressive disorders, over an 18-month follow-up period. To this end, we conducted a randomised controlled trial in which we applied PPT in groups [

8,

9] and compared the results with those of the standard CBT intervention for treating depression [

18], which was also applied in groups. The prevalence of mental health conditions often exceeds the available treatment resources, particularly in German-speaking countries, where group psychotherapy offers a viable alternative. There is also substantial evidence supporting the effectiveness of group therapy, showing outcomes comparable to those of individual psychotherapy [

19]. Accordingly, we opted for a group setting, in line with previous studies on positive psychotherapy. We selected CBT as the control group because it currently represents the gold standard in the treatment of depression (e.g., [

20]). The two main objectives of our study, both related to the 18-month-follow-up period, are: Firstly, to investigate whether PPT is superior to CBT in enhancing positive resources, including well-being and happiness, and secondly, to explore whether PPT is superior to CBT in reducing depressive symptoms and psychological distress. Feelings of well-being and happiness were chosen as the primary outcomes because PPT focuses on enhancing psychological resources including happiness and well-being. According to this focus self- and observer-rated depression and the individuals’ level of psychological distress were chosen as secondary outcomes.

This study is a long-term follow-up of two previously published pre-post and six-month follow-up studies comparing PPT and CBT [

17,

21]. Starting from identical levels of symptoms PPT resulted in significantly lower levels of depressive and psychological distress symptoms at post-treatment and at the six-month follow-up, with consistently high effect sizes. In contrast, CBT resulted in smaller effects. Regarding well-being, including feelings of psychological well-being, life satisfaction and flourishing, the PPT group resulted in significant improvements in all outcome measures, indicating medium-to-high effect sizes, and these improvements remained stable for up to six months. Furthermore, the findings revealed differences over time between the treatment conditions for the psychological well-being total score, two of its five subscales (positive emotions and engagement), the Flourishing Scale and the Satisfaction with Life Scale, indicating superior outcomes for PPT following treatment.

Considering the results of our previous studies and the research into long-term outcomes from literature, we hypothesize that PPT will demonstrate superior long-term improvements in both outcome dimensions (well-being and depressive and psychological distress symptoms) compared to CBT, with these improvements remaining stable for up to 18 months.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

This two-centre study is an 18-month follow-up of the previously reported randomized controlled trial, where participants (N = 92) were allocated either to PPT (n = 46) or CBT (n = 46) group therapies as two active conditions. Both treatments comprised 14 sessions of 2 hours per week and were conducted according to the empirically supported PPT- and CBT- treatment manuals. The study’s interventions and data collection containing baseline assessment (t1), post-intervention assessment (t2), a 6-month follow-up as well as an 18-month follow-up measurement, took place over a period of more than 2 years. To evaluate long-term outcomes, self-report and observer rated measurements are available. In the present study, only the results of the 18-month follow-up measure will be presented.

2.2. Interventions

2.2.1. Positive Psychotherapy (PPT)

The PPT group treatment followed the protocol developed by [

9]. It is a manualized 14-session protocol, primarily for group therapy. Each session comprises a psychoeducational part, in-session exercises and group discussions. The most important parts, however, are homework exercises that are provided in a fixed sequence. Participants take at least one hour per week to complete these exercises. The goal is to make clients understand and practice the basic principles of flourishing based on the PERMA-model. Some exercises run throughout the whole intervention (e.g. the “Three Good Things” application; [

22]) where clients keep a daily journal about good things that happen during the day to counteract the negativity-bias [

9].

Table 1 gives an overview of the session-by-session topics of the PPT condition.

2.2.2. Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT)

In our study, CBT comprised the manualized 12-session-protocol for groups by Schaub, et al. [

18], which is a highly structured cognitive psycho-educative coping program for depression including interventions of psychoeducation and cognitive behavioral exercises based on a multidimensional functional concept of depression comprising aspects of vulnerability, stressors and coping strategies. Additionally, it deals with rewarding activities and includes information about treatment options, cognitive restructuring, and relapse prevention with weekly homework assignments. To make CBT conform to the 14-session-model of PPT, we added two extra sessions to the original manual: Based on the protocol’s stress-vulnerability model, one extra session deals with stress and stressors as possible causal agents of depression. Based on CBT principles, specific stress management strategies were imparted (cognitive, instrumental, and regenerative strategies; [

23]) with a special focus on relapse prevention. “Savoring” is the topic of the second extra session, as in German language countries, savoring is a very important part of CBT treatment of depression (e.g. [

24]).

Thus, both therapies comprised 14 group sessions of 2 hours per week (120 min) and each treatment was conducted according to its respective protocol.

Table 2 provides an overview of the session-by-session topics of the cognitive behavioral group therapy and its extra sessions.

2.3. Participants and Procedure

Sample size was calculated in advance, using G*power analysis software 3.1 [

25]. To detect small effects of Cohen’s d = 0.30 with a power of β= 0.80 and an α-level of 0.05, the estimated total sample size was

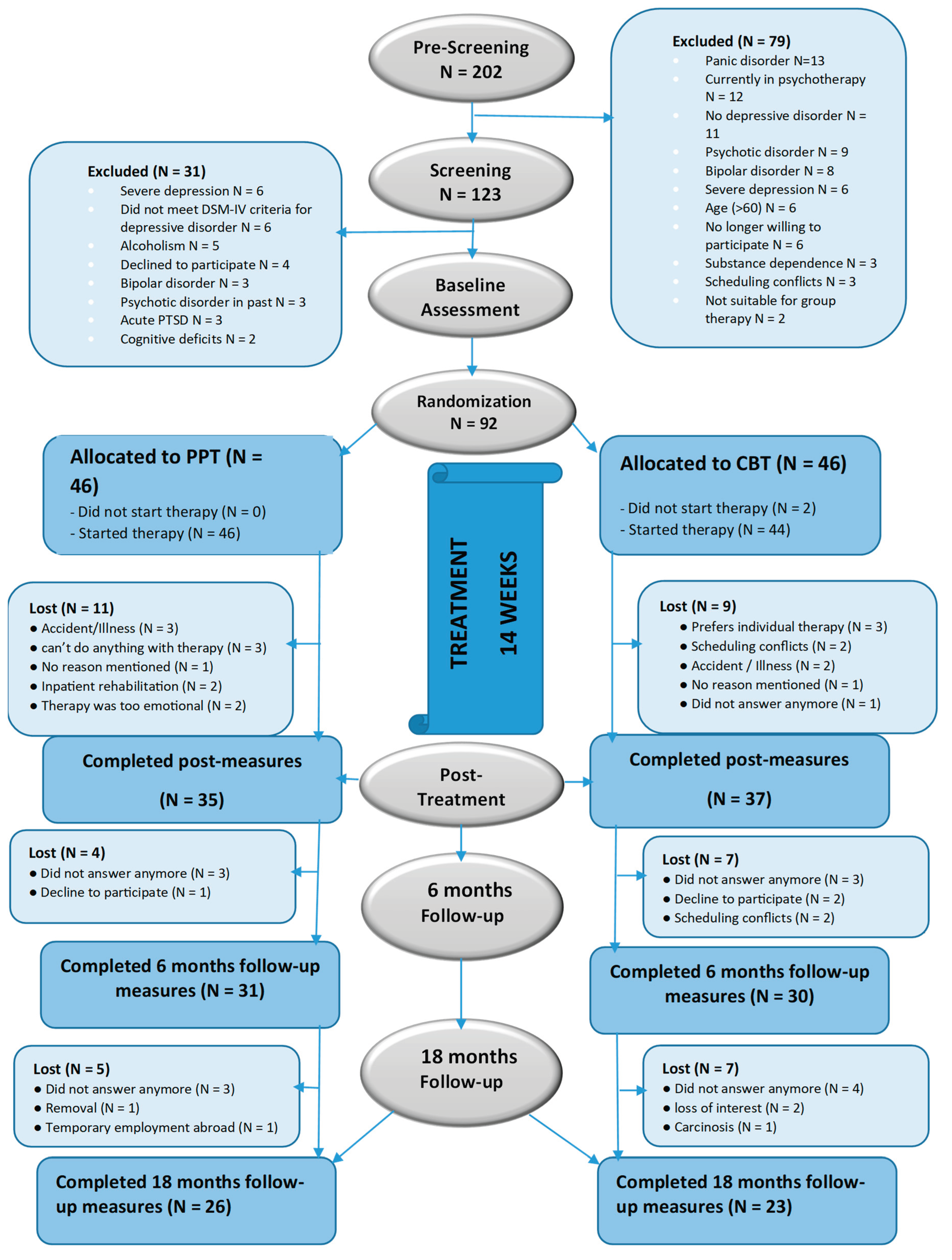

N = 90. Before starting with the recruitment phase, approval for the present study was obtained by the federal ethics committee of XX XX, which was accepted by the research ethics board of the University of XX. Participants were recruited nationally in two different treatment centres in Austria (two-centre-study) with different kinds of acquisition. At the Outpatient Centre of the Department of Psychology of the University of XX, individuals were informed about the intended study through a university press release, a newspaper advertisement and through an email to all students and employees registered or working at the university. At XX, potential participants were recruited at the residential psychiatric hospital after their discharge. All subjects who applied for participation were selected using a three-step approach that is demonstrated in

Figure 1. All potential participants were pre-screened first by phone or face-to-face in the hospital to check the basic criteria. Those who met basic criteria on diagnosis and demographic variables were then invited to an individual assessment session of approximately 3 hours lengths. During that time, detailed information about the ongoing study was provided and inclusion and exclusion criteria were checked, using the German version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I; [

26]). Patients were eligible for the study if they (1) were between 18 and 60 years of age, (2) were having a mild to moderate major depressive disorder or dysthymia according to DSM-IV-TR [

26], (3) spoke German sufficiently. Exclusion criteria were (1) currently undergoing psychotherapeutic or psychological treatment, (2) having a severe major depressive disorder, (3) current substance dependence, (4) current severe eating disorder, (5) current panic disorder, (6) hypomanic, manic or bipolar disorder or (7) psychotic disorders. In case of matching these criteria, a signed informed consent was obtained from all participants; there was no compensation or payment for attendance. During participation, individuals were allowed to continue with their pharmacological treatments.

Of the 202 subjects registered for participation, 92 finally met the inclusion criteria. They filled baseline assessments and demographics with anonymous data collection. Subsequently, they were randomized to one of the treatment conditions (PPT or CBT), using a true random number service (

www.random.org). Detailed information about participants’ flowchart is shown in

Figure 1.

Therapy was administered in small groups of 6 to 7 persons and both treatments were applied in a single trainer setting. In total, seven different therapists were involved in this study. All of them were female clinical psychologists aged between 25 and 44 years. One in each condition (PPT, CBT) was a licensed clinical psychologist working in this field already for several years, the other five being in training for clinical psychology under supervision. Assignment of the group leaders was not random because of structural requirements of the respective institutions or group leaders’ individual preference for one or other condition. Regardless of their current educational and experiential background, all trainers were intensively trained by two clinical psychologists who had sufficient clinical practice and experience in the respective treatments. Moreover, all group leaders were supervised weekly in the application of their respective protocols by their trainers. As additional control, every group leader had to protocol each session and the protocols were compared with the proposed manualized session’s process by independent raters.

2.4. Outcome Measures

The applied questionnaires comprised one observer-rated and six self-report measures. The assessments were carried out at the beginning and the end, and 6 months (follow-up I) and 18 months (follow-up II) after termination of treatment.

2.4.1. Primary Outcomes

2.4.1.1 Psychological well-being. The Positive Psychotherapy Inventory (PPTI; [

27]) is a PPT-related self-report questionnaire that was used to measure flourishing according to the PERMA- or ‘flourishing’-model [

8]. The German form was developed by translating the English items into German and retranslated into English by two independent bilingual experts who were fluent in both languages. The PPTI consists of 25 items assessing the five PERMA domains by Seligman [

8] with five items each (positive emotions, engagement, positive relationships, meaning, accomplishment) (for details see [

9]). For each statement, the participant has to choose the degree to which this item applies to them. Each answer is assigned a value from 1 (“not at all like me”) to 5 (“very much like me”), so that the total score ranges from 25 to 125, with higher scores indicating greater well-being. The internal consistency of the total scale is high, with α = .89. In the present study, the internal consistency of the total score with α = .91 was excellent.

2.4.1.2 Happiness/Flourishing. The German form of the Flourishing Scale (FS-D; [

28]) was used as a second measure to assess another facet of happiness and well-being. The scale consists of 8 items, each being phrased in a positive direction using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”), thus resulting in values between 8 and 56. Higher scores indicate a positive self-image and many psychological resources and strengths in important areas of functioning [

29]. The internal consistency of the scale was high in the present study with an α = .87.

2.4.1.3 Satisfaction with Life was measured with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; [

30]) consisting of 5 items using a seven-point Likert scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). In this study the internal consistency was high with α = .85.

2.4.2. Secondary Outcomes

2.4.2.1 Depressive symptoms. The revised 21-item Beck Depression Inventory-II ((BDI-II; [

31]; German adaptation by Hautzinger [

31]) was used to assess depressive symptoms (item score 0-3; total score range: 0-63). According to the authors, the BDI-II has good clinical sensitivity and a high reliability ranging from α = .89 to α = .94. Internal consistency was high with α = .89 in the present study.

2.4.2.2 The Depression-Happiness Scale (DHS; [

32]) is a subjective measure for the continuum of depression to happiness with 25 items with an answer-format from 0 (“never”) to 3 (“often”). The German form was developed by translating the English items into German and retranslated into English by two independent bilingual experts who were fluent in both languages. Internal consistency was excellent with α = .92 in the present study.

2.4.2.3 Severity of depressive episodes was measured with the 10-item Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; [

33]) as an observer-rated instrument. Item score ranges from 0 to 6 while total scores range from 0 to 60, higher scores indicating more severe depression. Internal consistency in this study was α = .84.

2.4.2.4. Psychological distress level and severity of symptoms were assessed with the German form of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) by Derogatis (German: [

34]) comprising 53 symptoms rated on a 5-point Likert scale. It contains nine primary symptom scales (somatization, depression, sensitivity, etc.) and three global indices of distress. In the present study, we used the most widely used Global Severity Index (GSI), which is designed to quantify a patient's severity-of-illness as a single composite score. Internal consistency in the present study was excellent with α = .93.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 25 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA) and R software version 2023.3.0.386 [

35]. We included all participants in our analysis, who completed the questionnaires regardless of how many therapy sessions they attended or whether they completed the therapy. Potential differences in participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline were analysed using Chi-square tests for categorical data and independent t-tests for continuous data. Cronbach’s Alpha was applied for reliability analyses at baseline. Estimated marginal means (

M) and standard errors (

SE) for each outcome measure were calculated at baseline as well as 18-month follow-up measurement.

Linear mixed models were performed to test long-term efficacy of treatment. Negative outcomes (depressive symptoms and psychological distress level) as well as positive outcomes (well-being and happiness) served as the dependent variables and their baseline levels as the covariates. Due to the study being carried out at two distinct locations, we incorporated study-site as a covariate in the models. Our analyses focused on a single dependent variable at a time, such as BDI-II, DHS, or SWLS. To address potential dependencies between participants in the repeated measures, random intercepts were incorporated in all models. To gain a more precise understanding of the changes in outcomes, we conducted pairwise comparisons with Tukey correction. This allowed us to examine the differences within and between measurements and treatment groups.

We utilized the lmerTest package in RStudio [

36] for conducting mixed-model analyses, while the emmeans package was used for performing pairwise comparisons. To assess normality and homoscedasticity, the residual plots were visually examined, utilizing the sjPlot package in R. The models were fitted using restricted maximum likelihood estimation (REML). Eta square was calculated for effect sizes (small effect η2 < 0.06; medium effect η2 = 0.06 to 0.14; large effect η2 ≥ 0.14; [

37]).

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

No differences were found at baseline in demographic and clinical characteristics between both conditions (see

Table 3). Similarly, no differences were found at baseline between both conditions in any of the outcome measures (see

Table 4).

For the 92 participants at baseline, mean age was 40.66 years, most of them were female (

n = 59; 64.1%) and educational level was rather high (see

Table 3), 49 individuals (53%) completed assessments at 18 months follow-up. As demonstrated in

Figure 1, 92 (100%) provided data at baseline, 77 (84%) at post-treatment, 61 (66%) at 6 months follow-up, and 49 (53%) at 18 months follow-up. Attrition at 18 months follow-up was unrelated to treatment allocation (χ

2 = 0.26,

df = 1,

p = .61). The average number of sessions attended for PPT was 10.70 ± 3.9 out of 14 and 10.70 ± 4.4 for CBT indicating no significant differences in compliance. Equally, there was no differential dropout over time between both conditions (see

Table 3).

3.2. Primary and Secondary Outcomes

Table 4 shows estimated marginal mean scores (and

SEs) for baseline assessment and 18 months follow-up measurement for a first overview. In general, the mean levels of well-being related outcome measures increased over time in both conditions and the mean level of depressive and psychological distress symptoms decreased over time in both conditions.

The residual errors and random effects for all variables exhibit a normal distribution, indicating that the statistical assumptions for mixed-effects models are satisfied.

Significant Time

× Group interactions emerged for the SWLS, DHS, BDI-II, and BSI (

Table 5), showing that those in the PPT condition had lower levels of depressive symptoms (DHS, BDI-II, BSI) and more life satisfaction (SWLS) over time than those in the CBT condition. Superiority of PPT in these measures was associated with effect sizes of partial η

2 > 0.02 at the 18 months follow-up, which can be categorized as small.

The interactions of Time

× Group at 18 months follow-up were not significant for flourishing, PPTI total score and all subscales, and MADRS, indicating no significant differences in long-term treatment outcome between PPT and CBT (see

Table 5).

We found significant effects of time for SWLS, flourishing, PPTI total score, positive emotions, engagement, DHS, MADS, BDI, and BSI, indicating significant improvements over time (see

Table 5).

Pairwise comparisons revealed that all well-being related outcomes (satisfaction with life, flourishing, PPTI total score, the subscales positive emotions, engagement, relationship, meaning, and accomplishment) increased significantly and all depressive symptoms (DHS, MADRS, BDI-II) and psychological distress (BSI) decreased significantly in the PPT group from preintervention to 18 months follow-up (η

2 = 0.19;

p < .001; η

2 = 0.14;

p < .001; η

2 = 0.16;

p < .001; η

2 = 0.17;

p < .001; η

2 = 0.14;

p < .001; η

2 = 0.04;

p = .012; η

2 = 0.07;

p = .001; η

2 = 0.07;

p = .001; η

2 = 0.16;

p < .001; η

2 = 0.28;

p < .001; η

2 = 0.29;

p < .001; η

2 = 0.19;

p < .001, respectively; see also

Table 4). In the CBT group, the subscale accomplishment increased significantly and the MADRS decreased significantly from preintervention to 18 months follow-up (η

2 = 0.03;

p = .05; η

2 = 0.14;

p < .001, respectively). We found between-group effects at the 18 months follow-up in well-being related outcomes (satisfaction with life, flourishing, PPTI total score, the subscales positive emotions, engagement, and meaning), depressive symptoms (DHS, MADRS, BDI-II), and psychological distress (BSI) indicating significant group differences at 18 months follow-up in favor of PPT (η

2 = 0.08;

p <.001; η

2 = 0.04;

p < .003; η

2 = 0.04;

p = .002; η

2 = 0.06;

p < .001; η

2 = 0.04;

p = .003; η

2 = 0.02;

p = .032; η

2 = 0.07;

p < .001; η

2 = 0.03;

p = .004; η

2 = 0.12;

p < .001; η

2 = 0.11;

p < .001, respectively).

There were no significant differences in any of the outcome variables when comparing the post-intervention measurement to the 18 months follow-up through pairwise comparisons. Thus, effects were stable over the 18-month follow-up period.

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4. Discussion

This study contributes to the limited literature on the long-term superiority of PPT compared to CBT. It was designed as an RCT, targeting individuals with depressive disorders treated in two different areas in Austria. In the previous articles regarding the effectiveness of PPT compared to CBT, PPT was reported to be effective in treating depression with effects lasting for at least 6 months. Findings indicated significant superiority of PPT over time with consistently large within effect sizes compared to the CBT condition, which showed minor effects. In terms of well-being related outcomes, PPT is effective in enhancing psychological well-being, happiness, and satisfaction with life, for up to 6 months. In the present paper, long-term stability of these effects over a period of 18 months was addressed. Outcomes were available for 49 participants. The main results regarding this follow-up were that the mean levels of depressive and psychological distress symptoms decreased and the mean levels of well-being and happiness increased over time in both conditions. No significant differences were found between both conditions regarding the level of observer-rated depressive symptoms (MADRS), psychological well-being (PPTI), and flourishing (FS). Importantly, however, PPT demonstrated superior long-term treatment outcomes regarding self-rated depressive (BDI-II, DHS) and psychological distress symptoms (BSI), and satisfaction with life (SWLS) compared to CBT. Between group effect sizes favourited PPT, ranging between η2 = 0.02 (PPTI) and η2 = 0.12 (BDI-II) which can be classified as small to medium.

Regarding the hypotheses established at the beginning of the study, it can be summarized that these were partially confirmed.

4.1. Results in Relation to the Literature

Within existing research, to the best of our knowledge, only few studies to date have directly examined the long-term outcome of any form of PPT. Furthermore, most of existing studies only addressed negative outcomes and did not include changes in positive resources [

13]. Our findings not only confirm previous studies on the sustainability of PPT effects but extend existing evidence by demonstrating the superiority of PPT over CBT in long-term outcomes. Studies by Seligman et al. [

6], Parks-Sheiner [

14], Lü and Liu [

15], and Ochoa et al. [

12] show a reduction in depressive symptoms through PPT after 3 to 12 months. In contrast to these studies, other research has found no significant differences—only a trend—between CBT and PPT [

13,

38], which aligns with our findings regarding observer-rated depressiveness, psychological well-being, and happiness.

The present study is the first one to evaluate the effectiveness of PPT over a long-term period of 18 months follow-up and compared it with an active control-condition. Moreover, it is one of the few studies that also has addressed positive outcomes in the long run.

4.2. Limitations

However, there are some limitations in our study that restrict the generalizability of the results and may hinder final conclusions. First, although we started with a sufficiently large sample of 92 subjects, the 18-month sample must now be considered not particularly large. Despite a prolonged inclusion period and efforts to enhance the enrolment rate, we could not include more than 49 patients (53%) who completed assessments at 18 months follow-up. The most common reason for incomplete questionnaires was that participants did not respond anymore. To investigate possible biases due to missing data, we conducted independent t-tests. Across all outcome measures, demographics, and main diagnoses, we found no significant differences between the characteristics at baseline measurement of those who were lost to follow-up compared to those who completed the last questionnaires. Moreover, attrition was unrelated to treatment condition. Therefore, it can be assumed that the absence or non-completion is random, and the principal study findings should hold true. However, the statistical power is reduced due to the missing data, which should be considered when interpreting the results.

Furthermore, given the number of outcomes analyzed, the issue of multiple testing must be acknowledged. This increases the risk of Type I errors, and findings should therefore be interpreted with caution. Another limitation is, that due to ethical reasons, we could not prevent participants from seeking any further psychotherapy during the 18 months follow-up period. As we did not pay heed to any additional treatment that participants made use of during the follow-up periods, our findings may be interpreted with caution. It could be that any further psychotherapy or other treatment alternative could have influenced the current findings in terms of overestimation of long-term treatment effects. Consequently, the extent to which differences in help-seeking behaviour has an impact on follow-up outcome measures must be targeted in further studies. Moreover, the results should be interpreted considering the non-random assignment of group leaders to the treatment conditions. Other limitations concerning the present study have been discussed in detail in the previous papers [XX, XX].

Despite these limitations, our results demonstrate the superiority of PPT over CBT in reducing symptoms based on subjective evaluations 18 months after therapy. However, the present evidence regarding the enhancement of well-being is inconclusive. We successfully replicated the findings of the few existing studies on long-term outcome of PPT and extended the knowledge about long-term stability of PPT over a period of 18 months. Research in this area is, however, still at the very beginning. The current findings are promising and should encourage future work to further support the present results on the long-term stability of PPT. For instance, conducting a meta-analysis of existing follow-up studies could provide a more comprehensive and integrated understanding of PPT’s long-term effects. Also, future investigations should identify potential mediators and moderators that could shed light on the reasons behind these outcomes. For example, a possible reason that PPT outperforms CBT in the long term could be that PPT emphasizes the cultivation of positive emotions, strengths, and meaning, rather than solely focusing on symptom reduction.

From a practical perspective, our findings indicate that PPT may be a valuable alternative or complement to traditional CBT, particularly for patients who aim not only to alleviate symptoms but also to improve overall well-being and life satisfaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F. and A.-R. L.; methodology, L. F.; software, E.F. and R. S.; validation, E.F. and A.-R. L.; formal analysis, E.F. and R. S.; investigation, E.F., L. M. F.; resources, A.-R. L.; data curation, E. F.; writing—original draft preparation, L. F.; writing—review and editing, E.F.; visualization, E.F.; supervision, A.-R. L.; project administration, E. F.; funding acquisition, A.-R. L.

Funding

This study was supported by two grants from the funding organization of the XX of X dedicated to the last author. Additionally, treatments conducted at the X study site were supported financially by the Outpatient Center of the Department of Psychology, University of X by offering payment to the trainers.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of X (protocol code XXX and date of approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The research data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge with thanks the contributions of the following people for making this study possible: XX XX, XX XX, XX XX, XX XX-XX, XX XX, and XX XX as group leaders and trainers, and XX XX, XX XX, XX XX XX, XX XX, XX XX, XX XX, and XX XX for screening, assessment, and conducting follow-up measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors has, or has had, any financial, personal or other relationship with people or organizations that would interfere with the presentation and interpretation of the present study’s findings.

References

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demier, O.; Jin, R.; Koretz, D.; Merikangas, K.R.; Rush, A.J.; Walters, E.E.; Wang, P. S. National comorbidity survey replication: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Journal of the American Medical Association 2003, 289(23), 3095–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hautzinger, M. Kognitive Verhaltenstherapie bei Depressionen [Cognitive behavioral therapy of depression; Beltz, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, Z.; Marnane, C.; Iranpour, C.; Chey, T.; Jackson, J. W.; Patel, V.; Silove, D. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis 1980-2013. International Journal of Epidemiology 2014, 43(2), 476–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuijpers, P.; Sijbrandij, M.; Koole, S. L.; Andersson, G.; Beekman, A. T.; Reynolds, C. F. The efficacy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in treating depressive and anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis of direct comparisons. World Psychiatry 2013, 12(2), 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, J. S. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and beyond, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. E. P.; Rashid, T.; Parks, A. C. Positive Psychotherapy. American Psychologist 2006, 61(8), 774–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, N. L.; Lyubomirsky, S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology 2009, 65(5), 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P. Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being.; Simon & Schuster, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, T.; Seligman, M.E.P. Positive psychotherapy – clinical manual.; Oxford University Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, A.; Finnegan, L.; Griffin, E.; Cotter, P.M.; Hyland, A. A randomized controlled trial of the Say Yes to Life (SYTL) Positive Psychology Group Psychotherapy Program for Depression: An Interim Report. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy 2017, 47(3), 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.; Cullen, K.; Keeney, C.; Canning, C.; Mooney, O.; Chinseallaigh, E.; O’Dowd, A. Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2020, 16(6), 749–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, C.; Casellas-Grau, J.; Vives, A.; Font, A.; Borràs, J.M. Positive psychotherapy for distressed cancer survivors: Posttraumatic growth facilitation reduces posttraumatic stress. International Journal of Clinical Health Psychology 2017, 17(1), 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppen, T. H.; Morina, N. Efficacy of positive psychotherapy in reducing negative and enhancing positive psychological outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open 2021, 11(9), e046017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks-Sheiner, A. C. Positive psychotherapy: Building a model of empirically supported self-help. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering 2009, 70(6-B), 3792. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, W.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. A pilot study on changes of cardiac vagal tone in individuals with low trait positive affect: The effect of positive psychotherapy. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2013, 88(2), 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoshani, A.; Steinmetz, S. Positive psychology at school: A school-based intervention to promote adolescents’ mental health and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies 15 2014, 1289–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furchtlehner, L. M.; Schuster, R.; Laireiter, A. R. A comparative study of the efficacy of group positive psychotherapy and group cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of depressive disorders: A randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2020, 15(6), 832–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, A.; Roth, E.; Goldmann, U. Kognitive-psychoedukative Therapie zur Bewältigung von Depressionen. Ein Therapiemanual [Cognitive-psychoeducational therapy for coping with depression. A therapy manual; Hogrefe, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rosendahl, J.; Alldredge, C. T.; Burlingame, G. M.; Strauss, B. Recent developments in group psychotherapy research. American Journal of Psychotherapy 2021, 74(2), 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, D.; Cristea, I.; Hofmann, S. G. Why cognitive behavioral therapy is the current gold standard of psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2018, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furchtlehner, L. M.; Fischer, E.; Schuster, R.; Laireiter, A. R. A comparative study on the efficacy of group positive psychotherapy and group cognitive behavioral therapy on flourishing, happiness and satisfaction with life: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Happiness Studies 2024, 25(7), 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P.; Steen, T. A.; Park, N.; Peterson, C. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist 2005, 60(5), 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluza, G. Stressbewältigung – Trainingsmanual zur psychologischen Gesundheitsförderung (3. Aufl). [Coping – Manual for psychological health promotion (3rd ed.)]. Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, R. Genusstherapie [Savouring therapy]. In Verhaltenstherapiemanual [Behavior therapy manual], 7th ed.; Linden, M., Hautzinger, M., Eds.; Springer, 2011; pp. 389–391. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfeler, E.; Lang, A. G.; Buchner, A. G*Power: A flexible statistical power analyses program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavioral Research Methods 2007, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittchen, H.U.; Zaudig, M.; Fydrich, T. SKID: Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM-IV [SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; Hogrefe, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, T. Positive psychotherapy Inventory.; Unpublished manuscript; University of Pennsylvania, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Esch, T.; Jose, G.; Gimpel, C.; Von Scheidt, C.; Michalsen, A. Die Flourishing Scale (FS) von Diener et al. liegt jetzt in einer autorisierten deutschen Fassung (FS-D) vor: Einsatz bei einer Mind-Bodymedizinischen Fragestellung [German validation (FS-D) of the Flourishing Scale (FS) by Diener et al.: A mind-body medical question]. Forschende Komplementärmedizin 2013, 20, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R. A.; Larsen, R. J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T.; Steer, R. A.; Brown, G. K. BDI-II. Beck Depression Inventory: Manual, 2nd ed.; Harcourt Brace, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hautzinger, M.; Keller, F.; Kühner, C. BDI-II - Beck-Depressions-Inventar - Revision. Manual [Beck Depression Inventory – Revision. Manual; Pearson Assessment, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McGreal, R.; Joseph, S. The Depression-Happiness Scale. Psychological Reports 1993, 73(3_suppl), 1279–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, S. A.; Asberg, M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry 1979, 134(3), 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, G. H. BSI. Brief Symptom Inventory. In Manual.; Beltz, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. RStudio [Computer software] 2023.

- Kuznetsova, A.; Brockhoff, P. B.; Christensen, R. H. B. lmerTest: Tests in linear mixed effects models [R package]. 2016. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lmerTest.

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, W. L.; Tierney, S. The effectiveness of positive psychology interventions for promoting well-being of adults experiencing depression compared to other active psychological treatments: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies 2022, 24(1), 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).