Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. The PVY NIb Is a Suppressor of RNA Silencing

2.2. Characterization of NIb Suppression of RNA Silencing

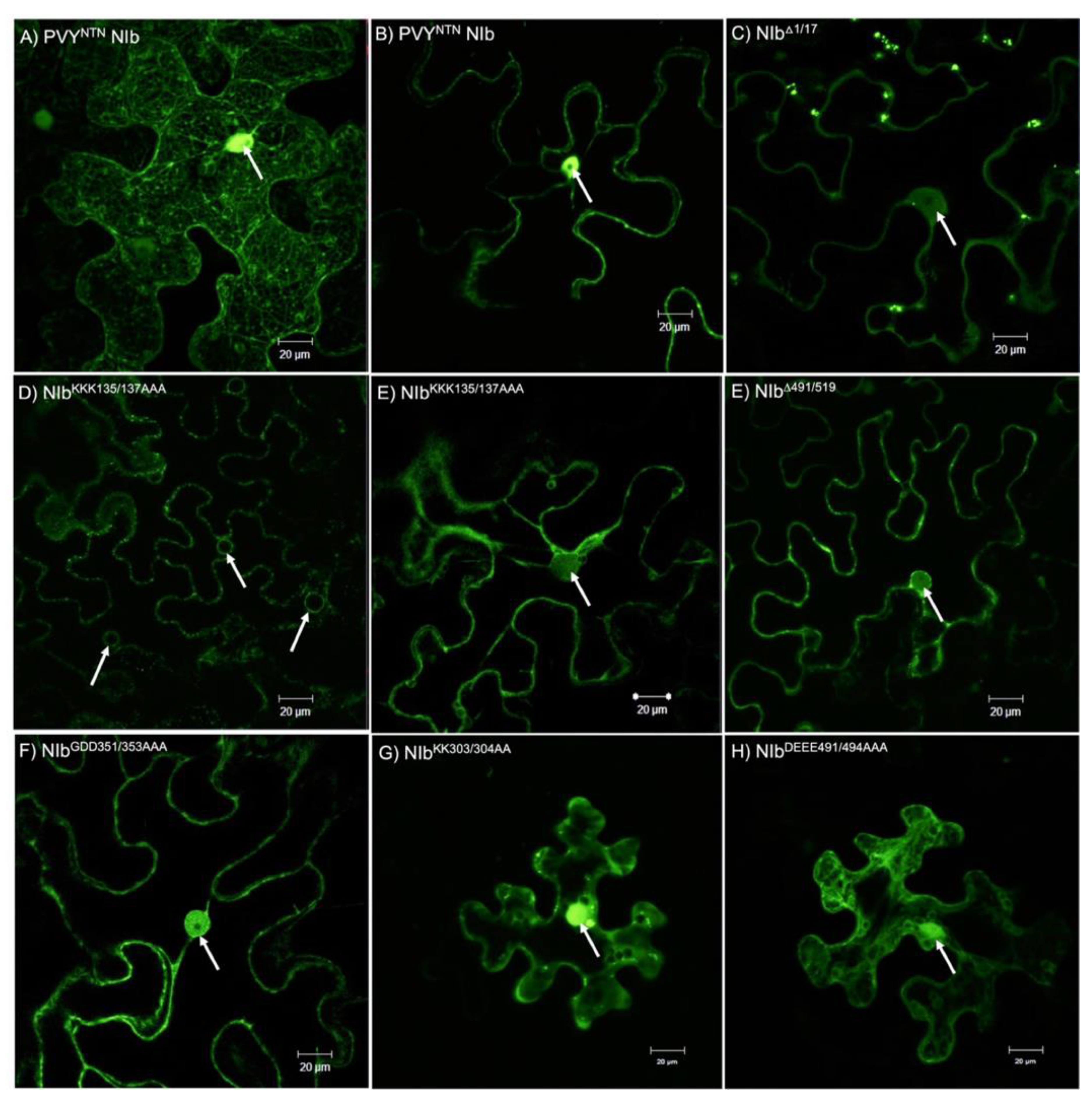

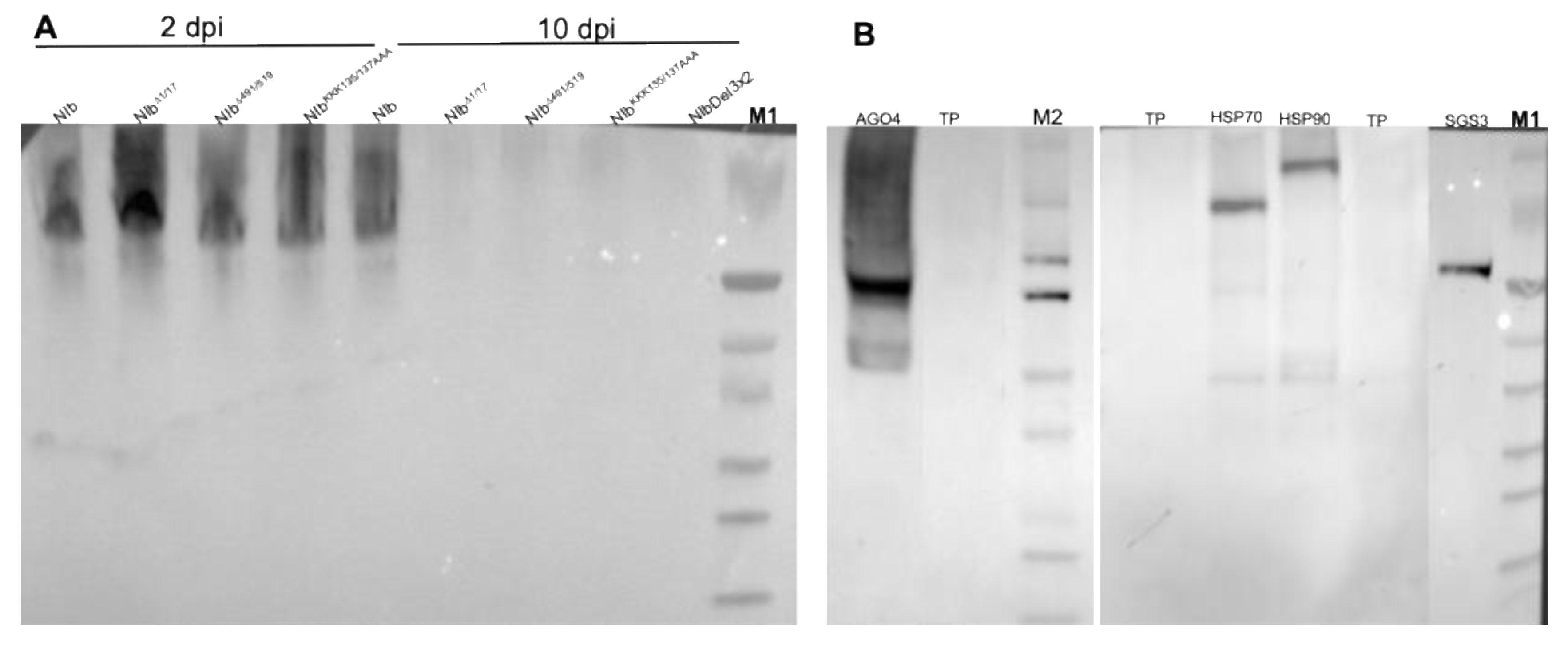

2.3. Nuclear Localization Is Required for NIb Suppression of RNA Silencing

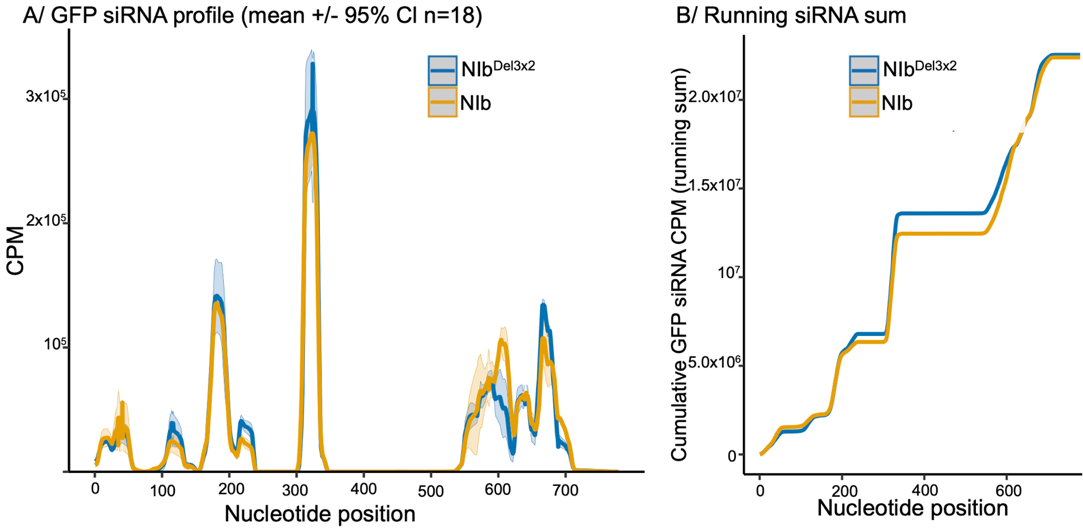

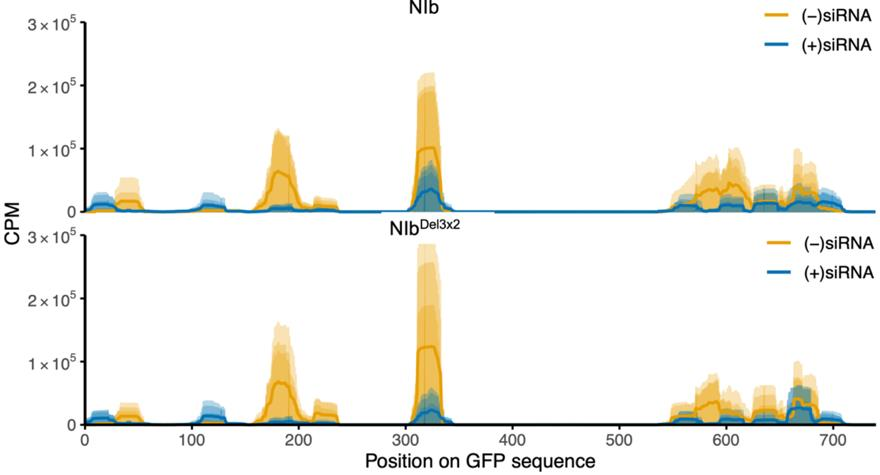

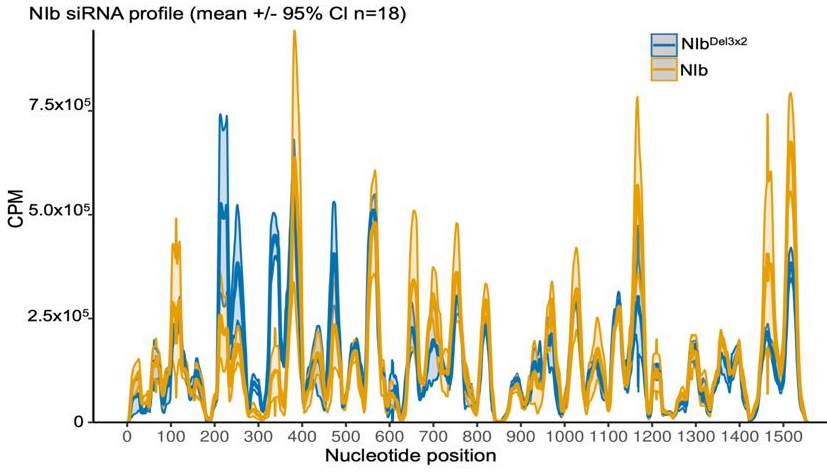

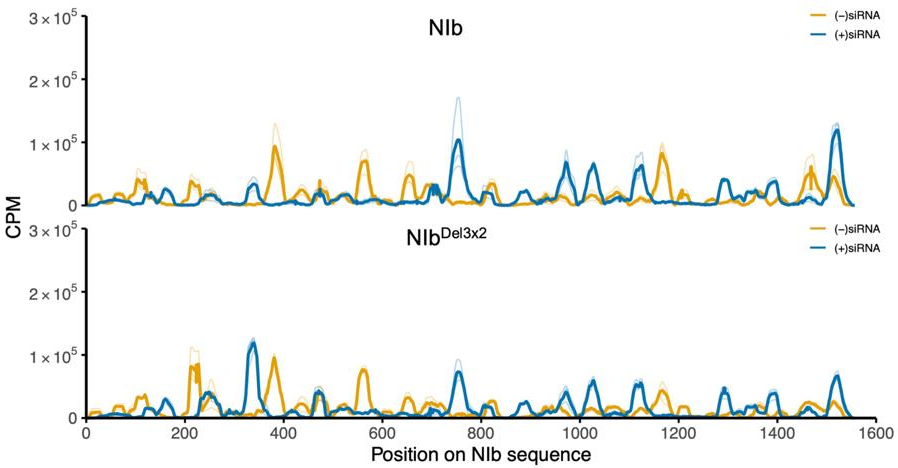

2.4. Small RNA Analysis

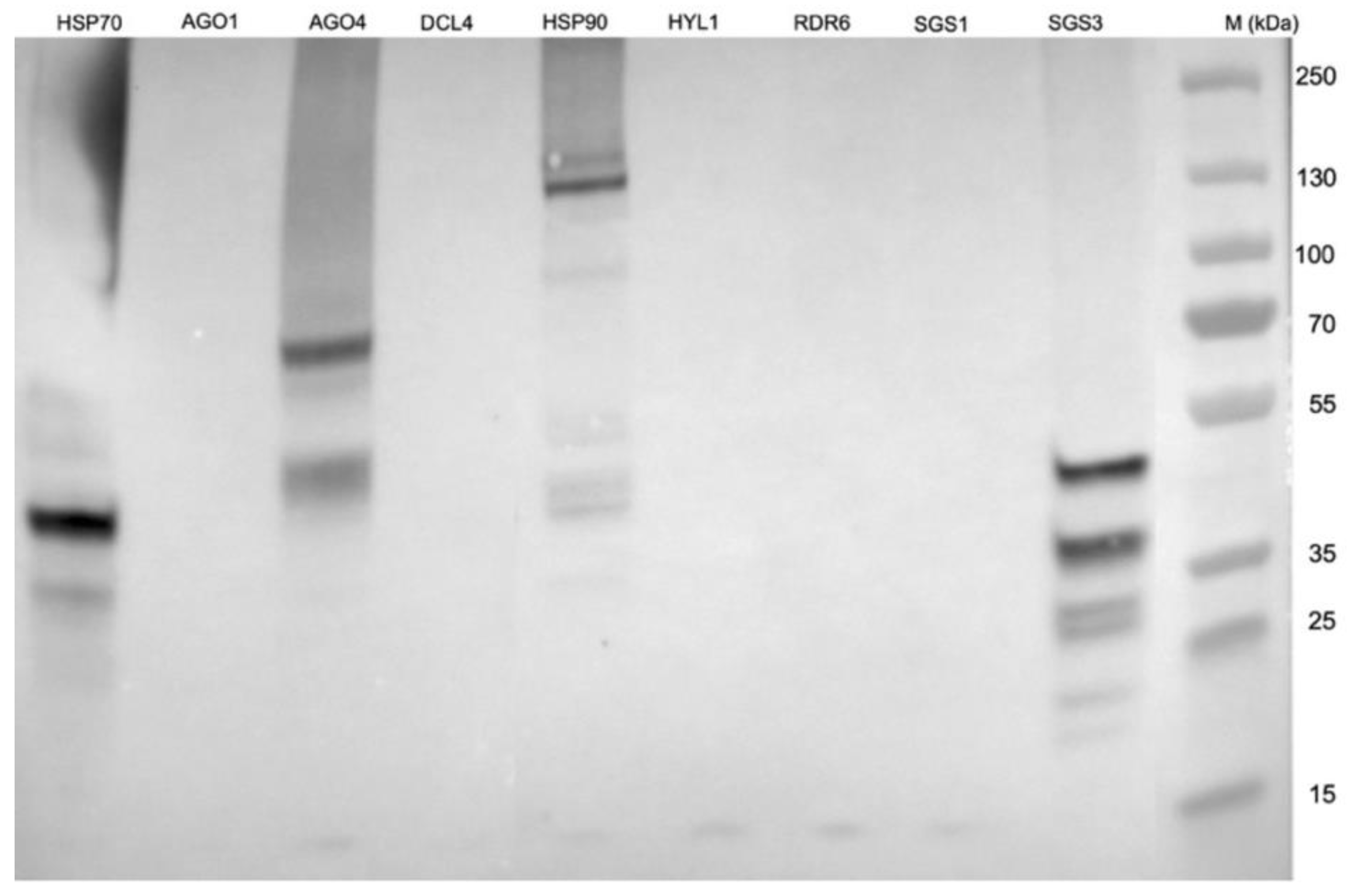

2.5. NIb Forms a Complex with Four RNA Silencing Pathway Proteins

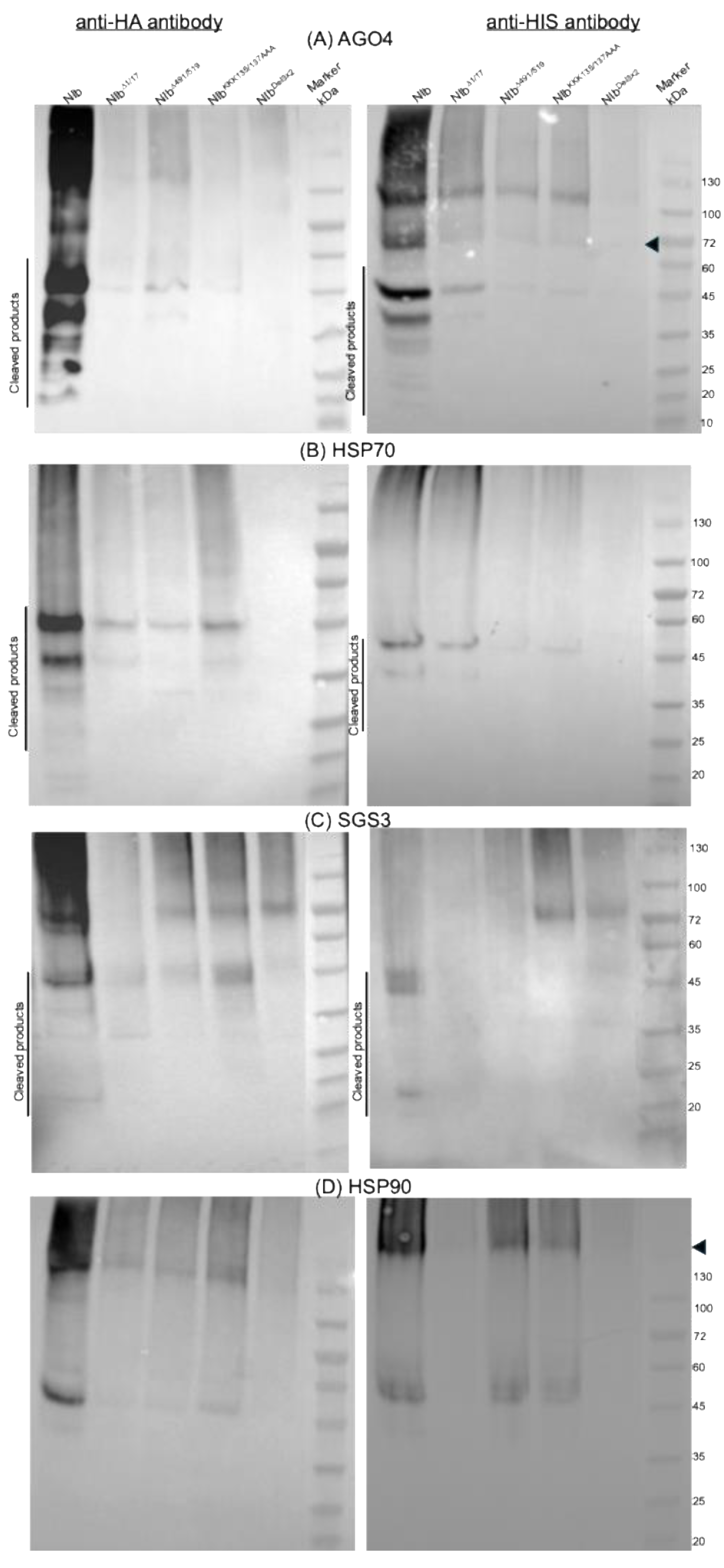

2.6. RNA Silencing Suppression Deficient NIb Mutants Do Not Interact with AGO4, HSP70, and SGS3

3. Discussion

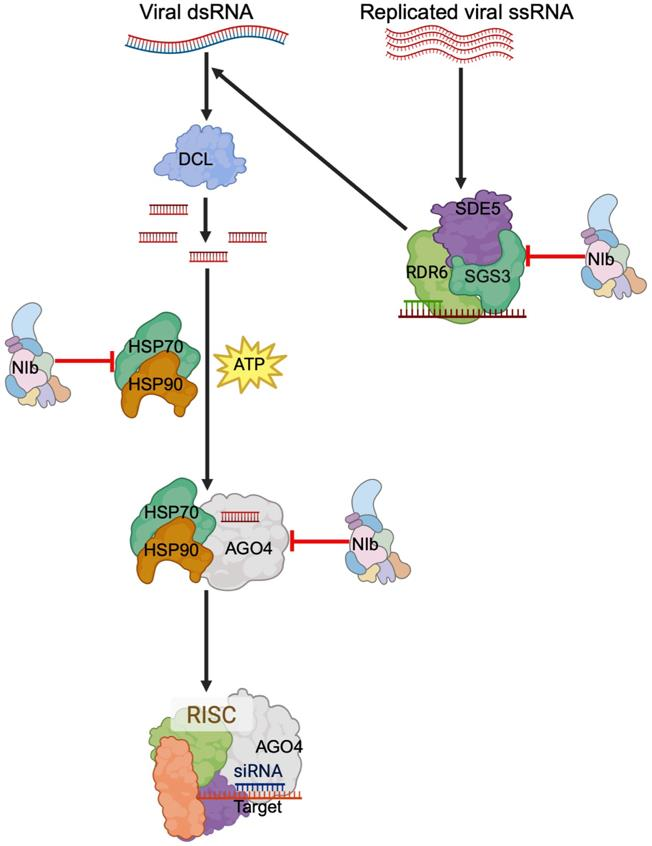

5. Model for NIb Suppression of RNA Silencing and Conclusion

6. Materials and Methods

6.1. Plasmid Construction and Agrobacterium Inoculation

| A/ Wild-type NIb primers | ||

| ID | Sequence | Construct |

| NTN_NIb-F NTN_NIb-R |

ggggacaagtttgtacaaaaaagcaggcttaATGGCCGCTAAACATTCTGCG |

PVYNTN |

| ggggaccactttgtacaagaaagctgggttTTGATGGTGCACTTCATAAGTATCG | ||

| NIb. NO.Nwi.O-F NIb.NO.Nwi.O-R |

ggggacaagtttgtacaaaaaagcaggcttaATGGCCGCTAAGCACTCTG |

PVYO, PVYN:O, PVYN-Wi |

| ggggaccactttgtacaagaaagctgggttTTGATGGTGTACTTCATAAGAGTCAAATTC | ||

| B/ Primers used to introduce mutations | ||

| ID | Sequence | Mutation |

| NIbΔKKK-F NIbΔKKK-R |

AGCTGACTACTTCGAGCATTTTAC | NIb KKK135/137AAA |

| GCTGCGCCTCCATACATAGCTCC | ||

| NIbΔKK-F NIbΔKK-R |

AACAATTGTCGCTGCTTTTAGAGGTAATAATAGCGGTC | NIbKK303/304AA |

| CCATCTGGAGTTGAGATTG | ||

| NIbΔGDD-F NIbΔGDD-R |

TGCATTATTGATTGCTGTGAATCC | NIbGDD351/353AAA |

| GCAGCATTAACAAAGAATACACACG | ||

| NIbΔDEEE-F NIbΔDEEE-R |

GCAGCTCTGAAGGCTTTCACTGAAATG | NIbDEEE491/494AAA |

| TGCAGCTACTGTCCTATTCATGTACAAC | ||

| NIbΔ1/17-F NIbΔ1/17-R |

GTGGCGACAATGAAGAGTC | NIbΔ1/17 |

| GGCCATTAAGCCTGCTTT | ||

| NIbΔ491/519-F NIbΔ491/519-R |

AACCCAGCTTTCTTGTAC | NIbΔ491/519 |

| TACTGTCCTATTCATGTAC | ||

| NIbΔGT855-856-F NIbΔGT855-856-R |

ACACAGAAATAATTTACACAC | NIBDEL3X2 |

| AAATTGCGCAACATTTGC | ||

6.2. Determination of NIb Suppression of RNA Silencing

6.3. Northern Blot Analysis

5.4. Determination of Subcellular Localization of NIb and NIb Mutants

6.5. siRNA Analysis

6.6. Identification of NIb Interacting Host Proteins

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, X.; Karasev, A.V.; Brown, C.J.; Lorenzen, J.H. Sequence Characteristics of Potato Virus Y Recombinants. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 3033–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, J.S.; Gray, S.M.; Karasev, A. V. Screening Potato Cultivars for New Sources of Resistance to Potato Virus Y. Am. J. Potato Res. 2014 921 2015, 92, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merits, A.; Rajamäki, M.-L.; Lindholm, P.; Runeberg-Roos, P.; Kekarainen, T.; Puustinen, P.; Mäkeläinen, K.; Valkonen, J.P.T.; Saarma, M. Proteolytic Processing of Potyviral Proteins and Polyprotein Processing Intermediates in Insect and Plant Cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2002, 83, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, B.Y.-W.; Miller, W.A.; Atkins, J.F.; Firth, A.E. An Overlapping Essential Gene in the Potyviridae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 5897–5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revers, F.; García, J.A. Molecular Biology of Potyviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2015, 92, 101–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urcuqui-Inchima, S.; Haenni, A.-L.; Bernardi, F. Potyvirus Proteins: A Wealth of Functions. Virus Res. 2001, 74, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozieł, E.; Surowiecki, P.; Przewodowska, A.; Bujarski, J.J.; Otulak-Kozieł, K. Modulation of Expression of PVYNTN RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase (NIb) and Heat Shock Cognate Host Protein HSC70 in Susceptible and Hypersensitive Potato Cultivars. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olspert, A.; Chung, B.Y.-W.; Atkins, J.F.; Carr, J.P.; Firth, A.E. Transcriptional Slippage in the Positive-Sense RNA Virus Family Potyviridae. EMBO Rep. 2015, 16, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodamilans, B.; Valli, A.; Mingot, A.; San León, D.; Baulcombe, D.; López-Moya, J.J.; García, J.A. RNA Polymerase Slippage as a Mechanism for the Production of Frameshift Gene Products in Plant Viruses of the Potyviridae Family. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 6965–6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Hunt, A.G. RNA Polymerase Activity Catalyzed by a Potyvirus-Encoded RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase. Virology 1996, 226, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Valdez, P.; Olvera, R.E.; Carrington, J.C. Functions of the Tobacco Etch Virus RNA Polymerase (NIb): Subcellular Transport and Protein-Protein Interaction with VPg/Proteinase (NIa). J. Virol. 1997, 71, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Shi, Y.; Dai, Z.; Wang, A. The RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase NIb of Potyviruses Plays Multifunctional, Contrasting Roles during Viral Infection. Viruses 2020, 12, E77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ullah, Z.; Grumet, R. Interaction between Zucchini Yellow Mosaic Potyvirus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase and Host Poly-(A) Binding Protein. Virology 2000, 275, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufresne, P.J.; Thivierge, K.; Cotton, S.; Beauchemin, C.; Ide, C.; Ubalijoro, E.; Laliberté, J.-F.; Fortin, M.G. Heat Shock 70 Protein Interaction with Turnip Mosaic Virus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase within Virus-Induced Membrane Vesicles. Virology 2008, 374, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.-S.; Wei, T.; Laliberteݩ, J.-F.; Wang, A. A Host RNA Helicase-Like Protein, AtRH8, Interacts with the Potyviral Genome-Linked Protein, VPg, Associates with the Virus Accumulation Complex, and Is Essential for Infection. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thivierge, K.; Cotton, S.; Dufresne, P.J.; Mathieu, I.; Beauchemin, C.; Ide, C.; Fortin, M.G.; Laliberté, J.-F. Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 1A Interacts with Turnip Mosaic Virus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase and VPg-Pro in Virus-Induced Vesicles. Virology 2008, 377, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Wu, G.; Hou, X.; Zhou, X.; Wang, A. Beclin1 Restricts RNA Virus Infection in Plants through Suppression and Degradation of the Viral Polymerase. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Xiong, R.; Li, Y.; Li, F.; Zhou, X.; Wang, A. Sumoylation of Turnip Mosaic Virus RNA Polymerase Promotes Viral Infection by Counteracting the Host NPR1-Mediated Immune Response. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 508–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldeman-Cahill, R.; Daròs, J.A.; Carrington, J.C. Secondary Structures in the Capsid Protein Coding Sequence and 3’ Nontranslated Region Involved in Amplification of the Tobacco Etch Virus Genome. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 4072–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäkinen, K.; Hafrén, A. Intracellular Coordination of Potyviral RNA Functions in Infection. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, K.I.; Eskelin, K.; Lõhmus, A.; Mäkinen, K. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms Underlying Potyvirus Infection. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 1415–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restrepo, M.A.; Freed, D.D.; Carrington, J.C. Nuclear Transport of Plant Potyviral Proteins. Plant Cell 1990, 2, 987–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaad, M.C.; Jensen, P.E.; Carrington, J.C. Formation of Plant RNA Virus Replication Complexes on Membranes: Role of an Endoplasmic Reticulum-Targeted Viral Protein. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 4049–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowda-Reddy, R.V.; Dong, W.; Felton, C.; Ryman, D.; Ballard, K.; Fondong, V.N. Characterization of the Cassava Geminivirus Transcription Activation Protein Putative Nuclear Localization Signal. Virus Res. 2009, 145, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowda-Reddy, R.V.; Achenjang, F.; Felton, C.; Etarock, M.T.; Anangfac, M.-T.; Nugent, P.; Fondong, V.N. Role of a Geminivirus AV2 Protein Putative Protein Kinase C Motif on Subcellular Localization and Pathogenicity. Virus Res. 2008, 135, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fondong, V.N.; Reddy, R.V.C.; Lu, C.; Hankoua, B.; Felton, C.; Czymmek, K.; Achenjang, F. The Consensus N-Myristoylation Motif of a Geminivirus AC4 Protein Is Required for Membrane Binding and Pathogenicity. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. MPMI 2007, 20, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Folimonov, A.; Shintaku, M.; Li, W.-X.; Falk, B.W.; Dawson, W.O.; Ding, S.-W. Three Distinct Suppressors of RNA Silencing Encoded by a 20-Kb Viral RNA Genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101, 15742–15747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Han, C.; Wang, Y. Development of Beet Necrotic Yellow Vein Virus-based Vectors for Multiple-gene Expression and Guide RNA Delivery in Plant Genome Editing. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1302–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Han, C.; Zhai, Y.; Yu, J. Two Virus-Encoded RNA Silencing Suppressors, P14 ofBeet Necrotic Yellow Vein Virus and S6 ofRice Black Streak Dwarf Virus. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2005, 50, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandalakshmi, R.; Pruss, G.J.; Ge, X.; Marathe, R.; Mallory, A.C.; Smith, T.H.; Vance, V.B. A Viral Suppressor of Gene Silencing in Plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998, 95, 13079–13084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasschau, K.D.; Carrington, J.C. A Counterdefensive Strategy of Plant Viruses: Suppression of Posttranscriptional Gene Silencing. Cell 1998, 95, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallory, A.C.; Ely, L.; Smith, T.H.; Marathe, R.; Anandalakshmi, R.; Fagard, M.; Vaucheret, H.; Pruss, G.; Bowman, L.; Vance, V.B. HC-Pro Suppression of Transgene Silencing Eliminates the Small RNAs but Not Transgene Methylation or the Mobile Signal. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruss, G.J.; Lawrence, C.B.; Bass, T.; Li, Q.Q.; Bowman, L.H.; Vance, V. The Potyviral Suppressor of RNA Silencing Confers Enhanced Resistance to Multiple Pathogens. Virology 2004, 320, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.-W.; Lin, S.-S.; Chen, K.-C.; Yeh, S.-D.; Chua, N.-H. Discriminating Mutations of HC-Pro of Zucchini Yellow Mosaic Virus with Differential Effects on Small RNA Pathways Involved in Viral Pathogenicity and Symptom Development. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. MPMI 2010, 23, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valli, A.A.; Gallo, A.; Rodamilans, B.; López-Moya, J.J.; García, J.A. The HCPro from the Potyviridae Family: An Enviable Multitasking Helper Component That Every Virus Would like to Have. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 744–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, S.; Pollari, M.; Varjosalo, M.; Mäkinen, K. Association of Host Protein VARICOSE with HCPro within a Multiprotein Complex Is Crucial for RNA Silencing Suppression, Translation, Encapsidation and Systemic Spread of Potato Virus A Infection. PLOS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondong, V.N.; Niraula, P.M. Potyvirus HcPro Suppressor of RNA Silencing Induces PVY Superinfection Exclusion in a Strain-Specific Manner. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, A. The Potyvirus Silencing Suppressor Protein VPg Mediates Degradation of SGS3 via Ubiquitination and Autophagy Pathways. J. Virol. 2016, 91, e01478-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, N.M.; Stoyanova, M.I.; Stoev, A.V.; Gaur, R.K. Induction of Gene Silencing of NIb Gene Region of Potato Virus Y by dsRNAs and siRNAs and Reduction of Infection in Potato Plants Cultivar Djeli. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2022, 36, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinnet, O.; Vain, P.; Angell, S.; Baulcombe, D.C. Systemic Spread of Sequence-Specific Transgene RNA Degradation in Plants Is Initiated by Localized Introduction of Ectopic Promoterless DNA. Cell 1998, 95, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, K.W.; Haag, J.R.; Pontes, O.; Opper, K.; Juehne, T.; Song, K.; Pikaard, C.S. Gateway-Compatible Vectors for Plant Functional Genomics and Proteomics. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2006, 45, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, V.V.; Dalakouras, A.; Steffens, V.A.; Krczal, G.; Wassenegger, M. High-Pressure Sprayed siRNAs Influence the Efficiency but Not the Profile of Transitive Silencing. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2022, 109, 1199–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilberman, D.; Cao, X.; Johansen, L.K.; Xie, Z.; Carrington, J.C.; Jacobsen, S.E. Role of Arabidopsis ARGONAUTE4 in RNA-Directed DNA Methylation Triggered by Inverted Repeats. Curr. Biol. CB 2004, 14, 1214–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Yoda, M.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Katsuma, S.; Suzuki, T.; Tomari, Y. Hsc70/Hsp90 Chaperone Machinery Mediates ATP-Dependent RISC Loading of Small RNA Duplexes. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X. SGS3 Cooperates with RDR6 in Triggering Geminivirus-Induced Gene Silencing and in Suppressing Geminivirus Infection in Nicotiana Benthamiana. Viruses 2017, 9, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Wang, A. SCE1, the SUMO-Conjugating Enzyme in Plants That Interacts with NIb, the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase of Turnip Mosaic Virus, Is Required for Viral Infection. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 4704–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Jia, M.; Shan, H.; Gao, W.; Jiang, L.; Cui, H.; Cheng, X.; Uzest, M.; Zhou, X.; Wang, A.; et al. Viral RNA Polymerase as a SUMOylation Decoy Inhibits RNA Quality Control to Promote Potyvirus Infection. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Y.; Liu, J.-L.; Gao, R.; Chen, J.; Shao, Y.-H.; Li, X.-D. Complete Genomic Sequence Analyses of Turnip Mosaic Virus Basal-BR Isolates from China. Virus Genes 2009, 38, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Gao, S.; Hernandez, A.G.; Wechter, W.P.; Fei, Z.; Ling, K.-S. Deep Sequencing of Small RNAs in Tomato for Virus and Viroid Identification and Strain Differentiation. PloS One 2012, 7, e37127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Adams, M.J. Characterisation of Potyviruses from Sugarcane and Maize in China. Arch. Virol. 2002, 147, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucinda, N.; da Rocha, W.B.; Inoue-Nagata, A.K.; Nagata, T. Complete Genome Sequence of Pepper Yellow Mosaic Virus, a Potyvirus, Occurring in Brazil. Arch. Virol. 2012, 157, 1397–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NLSExplorer Nuclear Localization Signal Exploration. Available online: http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/NLSExplorer/index.html (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Iki, T.; Yoshikawa, M.; Nishikiori, M.; Jaudal, M.C.; Matsumoto-Yokoyama, E.; Mitsuhara, I.; Meshi, T.; Ishikawa, M. In Vitro Assembly of Plant RNA-Induced Silencing Complexes Facilitated by Molecular Chaperone HSP90. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwakawa, H.-O.; Tomari, Y. Life of RISC: Formation, Action, and Degradation of RNA-Induced Silencing Complex. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuboyama, K.; Tadakuma, H.; Tomari, Y. Conformational Activation of Argonaute by Distinct yet Coordinated Actions of the Hsp70 and Hsp90 Chaperone Systems. Mol. Cell 2018, 70, 722–729.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmayan, T.; Blein, T.; Elvira-Matelot, E.; Le Masson, I.; Christ, A.; Bouteiller, N.; Crespi, M.D.; Vaucheret, H. Arabidopsis SGS3 Is Recruited to Chromatin by CHR11 to Select RNA That Initiate siRNA Production. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontes, O.; Vitins, A.; Ream, T.S.; Hong, E.; Pikaard, C.S.; Costa-Nunes, P. Intersection of Small RNA Pathways in Arabidopsis Thaliana Sub-Nuclear Domains. PloS One 2013, 8, e65652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnusamy, V.; Zhu, J.-K. Epigenetic Regulation of Stress Responses in Plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2009, 12, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S.A.; Slotkin, R.K. Broken up but Still Living Together: How ARGONAUTE’s Retention of Cleaved Fragments Explains Its Role during Chromatin Modification. Genes Dev. 2023, 37, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Huang, H.-Y.; Huang, J.; Singh, J.; Pikaard, C.S. Enzymatic Reactions of AGO4 in RNA-Directed DNA Methylation: siRNA Duplex Loading, Passenger Strand Elimination, Target RNA Slicing, and Sliced Target Retention. Genes Dev. 2023, 37, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamera, S.; Song, X.; Su, L.; Chen, X.; Fang, R. Cucumber Mosaic Virus Suppressor 2b Binds to AGO4-Related Small RNAs and Impairs AGO4 Activities. Plant J. 2012, 69, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejerman, N.; Mann, K.S.; Dietzgen, R.G. Alfalfa Dwarf Cytorhabdovirus P Protein Is a Local and Systemic RNA Silencing Supressor Which Inhibits Programmed RISC Activity and Prevents Transitive Amplification of RNA Silencing. Virus Res. 2016, 224, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Calvino, L.; Martínez-Priego, L.; Szabo, E.Z.; Guzmán-Benito, I.; González, I.; Canto, T.; Lakatos, L.; Llave, C. Tobacco Rattle Virus 16K Silencing Suppressor Binds ARGONAUTE 4 and Inhibits Formation of RNA Silencing Complexes. J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lõhmus, A.; Hafrén, A.; Mäkinen, K. Coat Protein Regulation by CK2, CPIP, HSP70, and CHIP Is Required for Potato Virus A Replication and Coat Protein Accumulation. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e01316-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafrén, A.; Hofius, D.; Rönnholm, G.; Sonnewald, U.; Mäkinen, K. HSP70 and Its Cochaperone CPIP Promote Potyvirus Infection in Nicotiana Benthamiana by Regulating Viral Coat Protein Functions. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himber, C.; Dunoyer, P.; Moissiard, G.; Ritzenthaler, C.; Voinnet, O. Transitivity-Dependent and -Independent Cell-to-Cell Movement of RNA Silencing. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 4523–4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niraula, P.M.; Baldrich, P.; Cheema, J.A.; Cheema, H.A.; Gaiter, D.S.; Meyers, B.C.; Fondong, V.N. Antagonism and Synergism Characterize the Interactions between Four North American Potato Virus Y Strains. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2024, 15, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, D.; Glazebrook, J. Transformation of Agrobacterium Using the Freeze-Thaw Method. CSH Protoc. 2006, 2006, pdb.prot4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.E.; Smith, D.M.; Gray, S.M. Preferential Acquisition and Inoculation of PVYNTN over PVYO in Potato by the Green Peach Aphid Myzus Persicae (Sulzer). J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funke, C.N.; Nikolaeva, O.V.; Green, K.J.; Tran, L.T.; Chikh-Ali, M.; Quintero-Ferrer, A.; Cating, R.A.; Frost, K.E.; Hamm, P.B.; Olsen, N.; et al. Strain-Specific Resistance to Potato Virus Y (PVY) in Potato and Its Effect on the Relative Abundance of PVY Strains in Commercial Potato Fields. Plant Dis. 2017, 101, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.; De Boer, S.; Lorenzen, J.; Karasev, A.; Whitworth, J.; Nolte, P.; Singh, R.; Boucher, A.; Xu, H. Potato Virus Y: An Evolving Concern for Potato Crops in the United States and Canada. Plant Dis. 2010, 94, 1384–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasev, A. V.; Gray, S.M. Continuous and Emerging Challenges of Potato Virus Y in Potato. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2013, 51, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, T.D.B.; Nie, X.; Bisht, V.; Singh, M. Proliferation of Recombinant PVY Strains in Two Potato-Producing Regions of Canada, and Symptom Expression in 30 Important Potato Varieties with Different PVY Strains. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 2221–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez, A.L.; Alonso, J.M.M.; Parra, F. Mutation Analysis of the GDD Sequence Motif of a Calicivirus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 3888–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, V.; Shen, Y.; Saijo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gusmaroli, G.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.P.; Deng, X.W. An Alternative Tandem Affinity Purification Strategy Applied to Arabidopsis Protein Complex Isolation. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2005, 41, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).