1. Introduction

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a common condition in older men, characterised by progressive enlargement of both glandular and stromal tissues within the prostate, resulting in increased organ volume (Angrimani et al., 2020; Chung et al., 2024). The prevalence of BPH continues to rise, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Estimates regarding its global impact differ; however, recent analyses suggest that approximately 210 million males worldwide may be affected, with a projected 45% risk of developing BPH over the next 30 years and an annual incidence of 379,000 men aged over 55 (Calogero et al., 2019; Tiruneh et al., 2024). BPH pathophysiology involves both increases in prostatic volume (static component) and smooth muscle tone (dynamic component) (S, R, & Nachiappa Ganesh, 2022). Hyperplasia primarily occurs in the region surrounding the proximal urethra, where glandular expansion leads to bladder outlet obstruction (BOO). This obstruction frequently results in lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), significantly diminishing patient quality of life. Common LUTS include increased urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia. As BPH progresses, more serious urinary complications may arise, including urinary retention, bladder diverticula, hydronephrosis, bladder stones, and renal insufficiency (Angrimani et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2025).

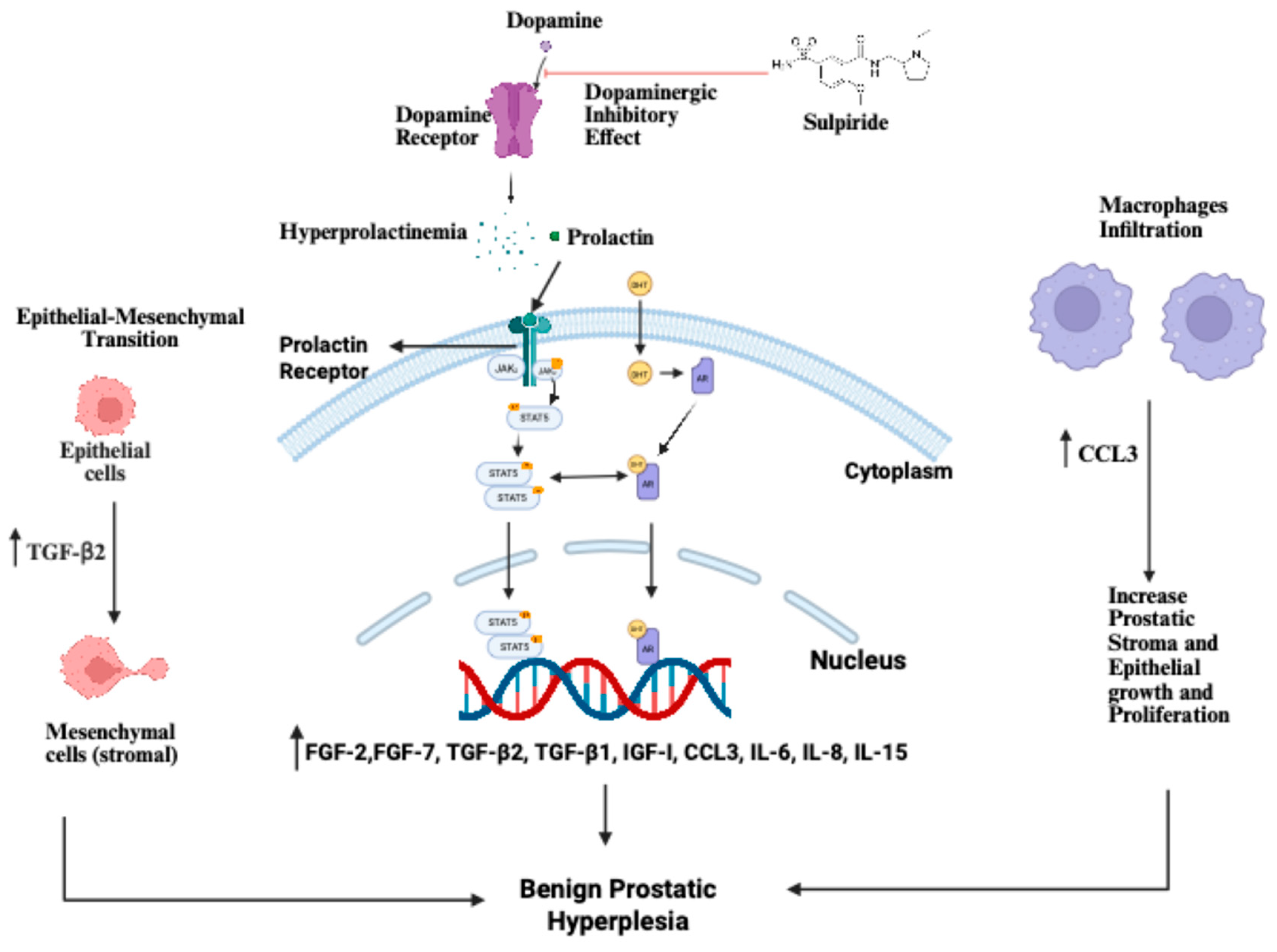

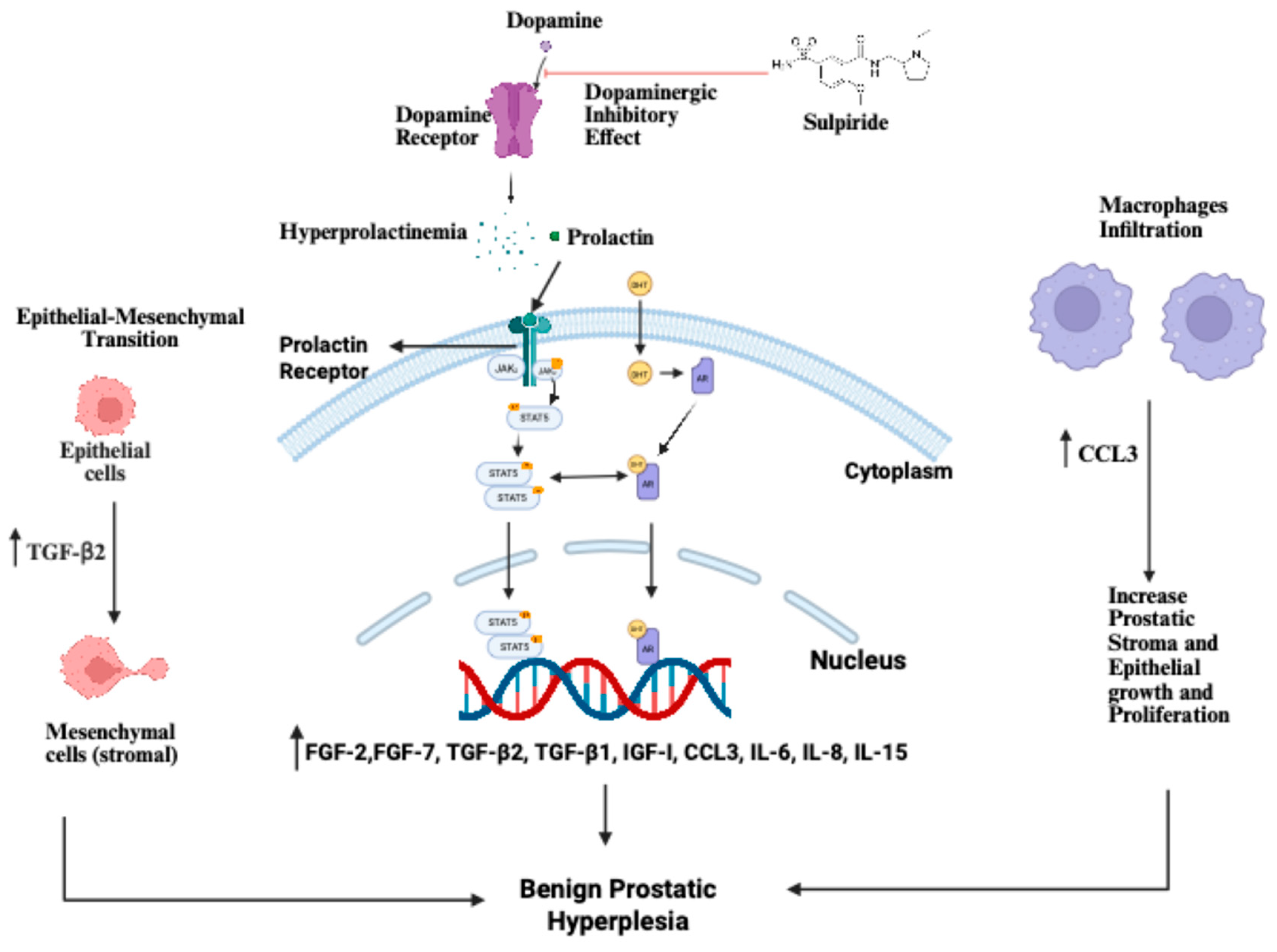

Sulpiride, known chemically as 2-methoxy-N-((1-propylpyrrolidine-2-yl)methyl)-5-sulphamoyl-benzamide, is a selective blocker of central dopamine receptors (D2, D3, and D4) (Mohamed & Soliman, 2010). It is mainly prescribed for schizophrenia, depression, and certain gastrointestinal disorders (Huang et al., 2019). Sulpiride exists as two optical enantiomers: (+) sulpiride and (-) sulpiride. Of these, the levorotatory (-) form, L-sulpiride, is more pharmacologically active within the central nervous system (Mauri et al., 1996). Side effects from doses at or above 600 mg/day include insomnia, fatigue, rapid heartbeat, liver problems, and tardive dyskinesia. By antagonising dopamine receptors, sulpiride also increases serum prolactin (PRL) levels (MacLeod & Robyn, 1977; Zheng et al., 2020), as shown in

Figure 2, which outlines the role of hypothalamic–pituitary interactions and prostate signalling in how sulpiride induces BPH in animal models. PRL contributes to the growth and development of BPH (Zheng et al., 2020), making sulpiride a common agent for inducing BPH in animal research.

Conversely, testosterone propionate (TP) is commonly employed to induce benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) in castrated rodent models. The standard protocol involves administering daily subcutaneous TP injections for approximately 4 weeks. This restoration of androgen (TP) stimulation elicits a robust proliferative response in the prostate, particularly within the ventral lobes, which demonstrate the most significant morphological changes. Histological examination of the prostate of experimental animals injected with TP consistently reveals features characteristic of BPH, including epithelial thickening, enlargement of glandular structures, and pronounced epithelial hyperplasia—closely paralleling the pathology observed in humans (Lee et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2012; Lee, Lee, & Song, 2024). This review examines the use of TP and sulpiride to induce BPH, highlighting the strengths and limitations of each agent in replicating clinical symptoms. We prefer the sulpiride model since it is easy to obtain.

In contrast, TP’s controlled status as a Schedule III drug in the United States and a Class C drug in the UK presents challenges for experimental use. In addition, the sulpiride model of BPH is non-invasive (does not require castration) and therefore closely mimics the pathogenesis of BPH in humans, unlike the TP model, which involves castration of the experimental animal. Throughout this review, we survey the literature on both sulpiride and TP to compare their effectiveness in rodent models of BPH.

2. Methodology

This narrative review integrates evidence from basic science research that a single systematic review could not encompass. The search included studies from January 1977 to July 2025, covering both foundational and recent mechanistic research. Literature was retrieved from PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science using combinations of MeSH and free-text terms, such as (“Benign prostatic hyperplasia induction” OR “rodent models”) AND (“Testosterone Propionate model”) AND (“sulpiride model”). Studies were selected if they used testosterone or sulpiride models to induce BPH. Studies were excluded if they were case reports that did not provide mechanistic or epidemiological information, were not in English without available translations, or had sources that could not be retrieved or verified. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, with eligible articles undergoing full-text review and thematic data extraction. No formal risk-of-bias scoring was performed; instead, studies were assessed by design, rigor, plausibility, and quality of evidence. As only published and publicly available data were reviewed, ethical approval was not required. Data were extracted based on key parameters—BPH induction, testosterone propionate, sulpiride, and rodent models—using thematic analysis. We compared findings across relevant studies to determine consensus, discrepancies, and evidence gaps. Instead of formal risk-of-bias tools, we assessed studies on design, sample size, methodological quality, biological plausibility, and alignment with existing evidence due to the review’s narrative approach. A thematic narrative approach was employed to synthesise the evidence, integrating epidemiological trends with mechanistic insights to develop a cohesive model for alternative methods of inducing and investigating BPH in rodent models. As this study relied exclusively on previously published data and publicly accessible reports, ethical approval was not necessary.

3. Androgens and Prolactin in BPH

Hormonal regulation is the main factor behind prostate growth in BPH. Research involving both humans and animal models has shown that androgens—especially testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT)—are key drivers of prostate enlargement. At the same time, prolactin (PRL) may further encourage prostate cell growth. Nicholson and Ricke (2011) reviewed evidence highlighting that signalling through the androgen receptor (AR) is essential for BPH. They pointed out that significant data connect androgens and AR activity to both prostate growth and the persistence of BPH; this connection is supported by the effectiveness of 5α-reductase inhibitors, which block the conversion of testosterone to DHT. Clinical evidence showing these drugs reduce prostate size and improve symptoms further strengthens this view (Diokno, Kunta, & Bowen, 2024). The effectiveness of these medications underscores the critical role of ongoing androgen-AR signalling in BPH. Androgens promote the differentiation and proliferation of both stromal and epithelial cells in the prostate, and changes in steroid balance—such as shifts in the ratio between androgens and estrogens—can alter interactions between stromal and epithelial cells and lead to hyperplasia.

La Vignera et al. (2016) noted that age-related hormonal changes, such as declining testosterone levels or an altered androgen-to-estrogen ratio, contribute to a tissue micro-environment conducive to BPH onset. Building on this, Tong and Zhou (2020) demonstrated a link between androgens and inflammatory signalling in BPH, reporting that dihydrotestosterone (DHT) found in BPH tissue may activate chronic inflammatory responses in the prostate. This process amplifies pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and enhances the proliferative capacity of prostate cells. These findings indicate that a localised increase in DHT level can induce inflammation, which subsequently promotes hyperplasia. Such evidence supports a model wherein androgen-driven growth and inflammatory pathways act collaboratively in the development of BPH (E. C. Lai et al., 2013; K. P. Lai et al., 2013). Using the probastin-prolactin (Pb-PRL) transgenic mouse model, these researchers investigated the interaction between prolactin and androgen receptor (AR) in BPH. Genetic ablation of AR in prostate stromal (fibromuscular) cells markedly reduced PRL-induced prostatic hyperplasia, with both stromal and epithelial cell proliferation diminished in AR-deficient prostates compared to wild-type controls. Mechanistically, the study demonstrated that prolactin (PRL) mediates epithelial–stromal crosstalk by acting through epithelial PRL receptors to upregulate granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), which subsequently stimulates stromal cell proliferation via STAT3 signalling. Their findings established that prolactin-driven prostate growth depends on the presence of the androgen receptor (AR) in the stroma and identified a PRL/PRLR/GM-CSF/stromal proliferation axis in benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

Dos Santos et al. (2024), in their recent investigation utilising the Pb-PRL transgenic mouse model, revealed that this model recapitulates numerous histologic features characteristic of human BPH. Single-cell analysis indicated that PRL-induced BPH involves the expansion of epithelial cell subpopulations with diminished androgen signalling, likely originating from the reprogramming of normal luminal cells. Functionally, prostates from Pb-PRL mice exhibited increased vulnerability to oxidative stress. Treatment of these mice with an antioxidant led to reduced prostate weight and improvement of urinary symptoms, as well as inhibition of proliferation in PRL-driven epithelial organoids. These results suggest that PRL-driven hyperplasia can activate non-AR–dependent pathways—such as stress response and stemness programs—in BPH, thereby implicating additional mechanisms beyond classic androgen action (Dos Santos et al., 2024). Taken together, these studies demonstrate that both androgens and prolactin (PRL) influence prostate cell growth. Androgens—especially DHT—bind to androgen receptors (AR), stimulating the proliferation of both stromal and epithelial cells; this underlies the use of 5α-reductase inhibitors in the treatment of BPH.

Additionally, DHT may create a local inflammatory environment that further encourages cell growth. Prolactin, via the prolactin receptor (PRLR), can activate pathways that promote growth and expand stromal tissue, as evidenced in PRL transgenic mouse models. Notably, the androgen and PRL systems interact: AR signalling increases PRL and PRLR expression in prostate cells, and higher blood PRL is associated with elevated AR levels. This bidirectional feedback means that, in BPH, androgens may make the prostate more responsive to prolactin’s effects—and vice versa.

4. Hyperprolactinemia

Hyperprolactinemia is characterised by an increase in the serum prolactin level beyond the normal range. (Jiang et al., 2024) It is caused by several effectors, including the inhibitory action of antipsychotics such as sulpiride on the dopaminergic type 2 receptor on the surface of lactotrophs (Kuchay & Mithal, 2017), specialised cells responsible for prolactin secretion, leading to drug-induced prolactin secretion. Hyperprolactinemia has been linked to various human health conditions, notably galactorrhea, ovarian dysfunction, vaginal mucosa, and neuroendocrine disorder (Cong et al., 2015). The side effects of hyperprolactinemia are more pronounced in females than in males, postulated to be caused by the estrogen-mediated increase in prolactin (Kroigaard et al., 2022). In females, hyperprolactinemia is implicated in diminished gonadal function (Mauri et al., 1996), enlargement of the breast, ovarian dysfunction, and has been hypothesised to be associated with the development of mammary duct ectasia (Cong et al., 2015). In male subjects, hyperprolactinemia has been linked to erectile dysfunction, reduction in semen volume, and reduced libido (Voicu et al., 2013). To reduce the risk of hyperprolactinemia and potential adverse side-effects, especially in schizophrenia patients on sulpiride therapy, a dose decrease of the anti-psychotic is highly recommended (Cong et al., 2015), or alternative anti-psychotic drugs with less risk of hyperprolactinemia, such as Aripiprazole, Lurasidone, Quetiapine, or Asenapine should be dispensed (Kroigaard et al., 2022).

The role of hyperprolactinemia in the development of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) has been extensively studied (Colao et al., 2004; Pascual-Mathey et al., 2016; Sanchez et al., 2008; Van Coppenolle et al., 2001). Sulpiride-induced, hyperprolactinemia-driven BPH is a well-established model for studying BPH and investigating potential therapeutic modalities (Dos Santos et al., 2024; Kwon, 2019; K. P. Lai et al., 2013) due to the known age-related increase in prolactin in men and laboratory animals. Other findings from sulpiride-induced hyperprolactinemia studies have demonstrated a dose-dependent increase in height, weight, and the number of epithelial cells in the prostate (Van Coppenolle et al., 2001; Zheng et al., 2020). While the exact mechanism of BPH emergence is unclear (Park et al., 2023) in TP- and/or sulpiride-induced BPH models, the role of prolactin and its receptors in the prostate gland acinar epithelium in the activation of numerous signal pathways involving STAT3 and STAT5 transcription factors in regulating cell transition in the mitotic cycle has been reported in the development of prostate epithelium hyperplasia (Tsvetkov et al., 2020).

5. Testosterone Propionate (TP)-Induced BPH Model

In laboratory research, TP is commonly used to induce BPH in rodents, modelling the androgen-dependent aspect of human BPH (Lim et al., 2025), and male Sprague–Dawley or Wistar rats are a typical model for BPH induction. To remove endogenous androgens, rats are often bilaterally castrated before hormone treatment (Lee, Lee, & Song, 2024). Following recovery, the castrated rats receive daily TP (an injectable testosterone ester) by subcutaneous injection. A standard protocol is TP 3–5 mg/kg body weight per day for 28 days to induce BPH (Lim et al., 2025). Several studies have administered low doses of TP (3–5 mg/kg) to experimental animals over extended periods ranging from five to seven months, while higher doses (10–25 mg/kg) have typically been utilised for shorter durations, such as fourteen days (Eruotor, Ezendiokwere, & Oghenemavwe, 2025; Guo et al., 2015; Wadthaisong et al., 2019). At the end of TP treatment, rats are sacrificed, and the prostate, especially the ventral lobe, is dissected. Prostate weight, absolute and relative to body weight, is recorded, and tissues are fixed for histology/immunostaining compared with the vehicle-treated control groups. This protocol reliably produces prostate enlargement. TP causes marked prostate growth relative to intact or sham-operated rats. It is considered a well-established model of BPH in rodents (Akanni, Abiola, & Adaramoye, 2017).

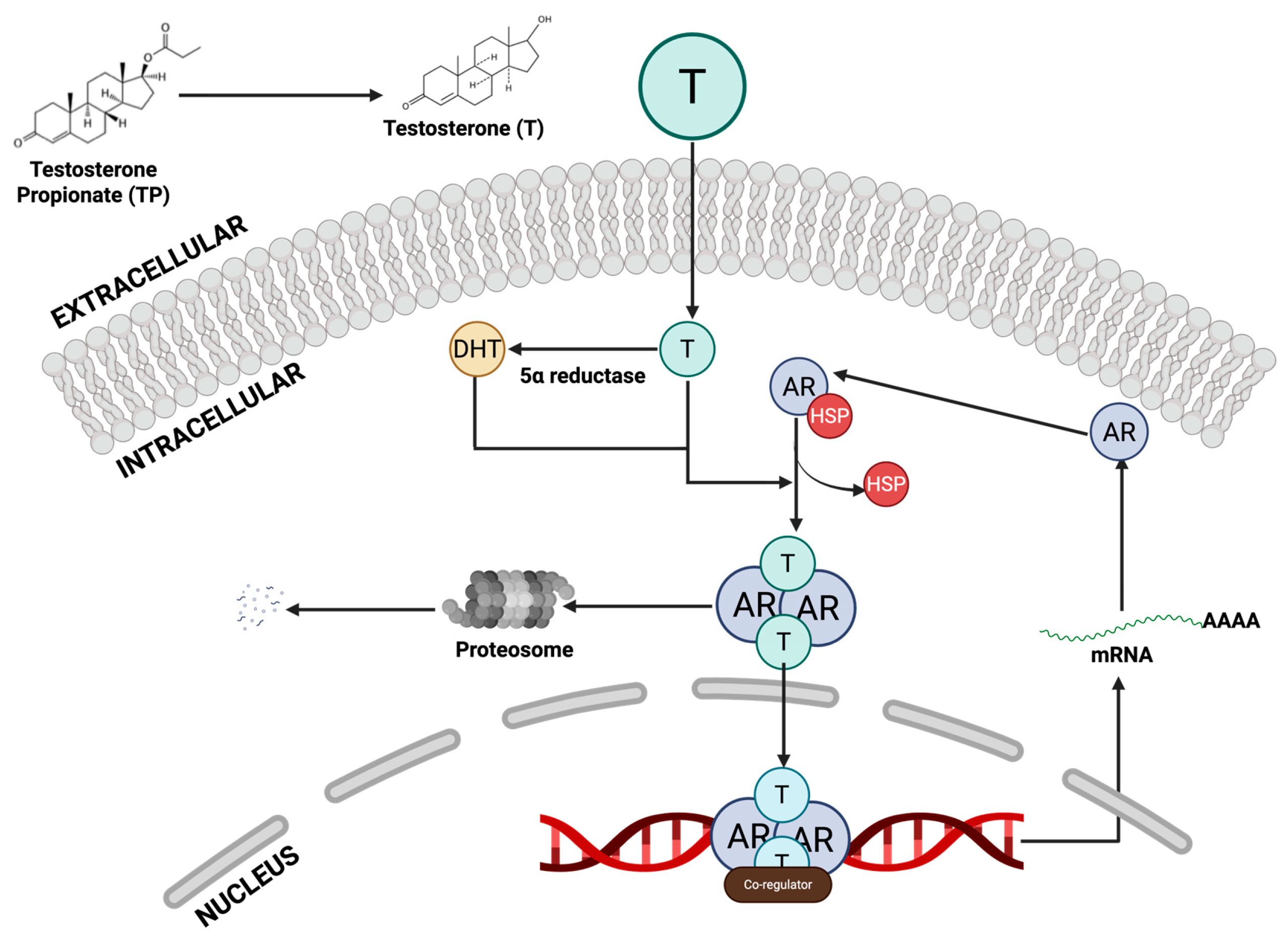

6. Mechanism of TP-Mediated BPH Induction

TP itself is a testosterone ester; once injected, it is rapidly converted to testosterone, which is then reduced to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by 5α-reductase in the prostate (Ahn et al., 2021). DHT is the most potent androgen in the gland. Both testosterone and DHT bind to the AR in the prostate epithelial and stromal cells. Upon androgen binding (

Figure 1), AR translocates to the nucleus and drives gene expression of growth factors and proliferative signals (Gryder et al., 2013; Li, Cheng, & Li, 2025). In effect, the TP regimen massively boosts local androgen/AR signalling, mimicking the hormonal driver of human BPH (Xu et al., 2024). The resulting AR activation stimulates the proliferation of prostate cells. The TP-induced BPH results in epithelial hyperplasia (marked expansion of the glandular epithelium) and stromal hyperplasia. Studies note that aberrant androgen/AR signalling potently drives the stromal compartment (which makes up 85–90% of the gland) and thereby promotes overall prostate enlargement (Jarvis, Chughtai, & Kaplan, 2015). In summary, exogenous TP increases circulating testosterone, which is converted to DHT; the DHT–AR complex then acts as a transcription factor to accelerate prostate cell proliferation.

7. Advantages and Limitations of the TP-induced BPH Model

The TP model specifically reproduces the androgenic component of prostatic enlargement. It reliably yields prostate overgrowth and epithelial hyperplasia like those seen in men under excess androgen stimulation.(Lim et al., 2025). Because it is simple and reproducible, it is widely used to test anti-androgen or anti-proliferative therapies. (Lee, Lee, & Song, 2024) However, by design, this model focuses only on hormonal effects. It employs supraphysiologic androgen doses and (often) surgically removed testis, which do not fully mimic natural ageing BPH. It ignores non-androgenic factors, such as chronic inflammation, metabolic changes, and growth factor dysregulation, that also contribute to human BPH. The androgen model is not suitable for nonhormonal therapy studies and employs high hormone doses that do not accurately mimic the actual disease state. Moreover, rat prostates differ anatomically from those of humans (multiple lobes, varying stromal/epithelial ratios), and rats do not typically develop lower urinary tract symptoms. (Lim et al., 2025). Thus, TP-induced BPH is best viewed as a model of androgen-dependent hyperplasia rather than a complete recapitulation of clinical BPH.

8. Sulpiride-Induced BPH Model

Experimental sulpiride-induced BPH is generated in intact male rats (no castration), typically late-reproductive-age animals, and often Wistar strain. (Van Coppenolle et al., 2001) Induced chronic hyperprolactinemia by treating sham-operated Wistar rats with sulpiride (40 mg/kg/day). Other protocols have given sulpiride orally or i.p. at 40–120 mg/kg daily for 4–6 weeks. Zheng et al. treated Brown-Norway rats orally with 40 or 120 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks and saw marked prostate enlargement. (Zheng et al., 2020). Borovskaya et al. injected Wistar rats with 40 mg/kg subcutaneously (or i.p.) for 60 days (Borovskaya et al., 2013), and Lesovaya et al. used 30 mg/kg i.p. for 28 days (Lesovaya et al., 2015). Despite these high doses, the model remains robust; all sulpiride-treated rats develop prostatic hyperplasia in the lateral lobes (and sometimes the dorsal lobes) (Sens-Albert et al., 2024). In practice, only intact male rats are used. No castration is performed because sulpiride acts by augmenting the animal’s hormonal milieu. Sulpiride-mediated D2 blockade raises prolactin levels above normal androgen levels, which are sufficient to drive BPH (Van Coppenolle et al., 2001).

9. Mechanism of Action

Sulpiride is a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist. By blocking D2 receptors on pituitary lactotrophs, it disinhibits PRL secretion. Chronic sulpiride causes hyperprolactinemia, which in turn stimulates prostate growth. (Sens-Albert et al., 2024; Zheng et al., 2020) Elevated prolactin exerts mitogenic and anti-apoptotic effects on prostate cells. Sulpiride-treated rats exhibit increased expression of proliferation markers (e.g., PCNA) and anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-2) in the prostate (Zheng et al., 2020). At the receptor level, prolactin upregulates sex-steroid receptors in the gland, including the AR and estrogen receptor α (ERα). After sulpiride treatment, both AR and ERα levels increase, while ERβ levels tend to decline. This shift amplifies hormonal stimulation of growth. For instance, increased AR levels may drive local production of growth factors (e.g., IGF-1 in the stroma) and epithelial proliferation. Van Coppenolle et al., demonstrated that hyperprolactinemia leads to significant Bcl-2 overexpression in the lateral prostate, thereby suppressing apoptosis (Van Coppenolle et al., 2001). Similarly, Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) signalling is activated, and sulpiride markedly increases TGF-β mRNA in the prostate (Sens-Albert et al., 2024), consistent with stromal expansion and extracellular matrix deposition. In summary, sulpiride increases prolactin, which then promotes both stromal and epithelial proliferation by boosting AR/ERα–driven mitogenic signalling and enhancing anti-apoptotic pathways (e.g., Bcl-2) and pro-growth factors (e.g., TGF-β) in the prostate. (Zheng et al., 2020)

10. Advantages and Limitations of Sulpiride-induced BPH

A key advantage of the sulpiride model is that it recapitulates non-androgenic drivers of BPH. Because intact animals are used, the endocrine environment remains physiological; no exogenous hormones or castration are required. This makes the model especially relevant for studying BPH associated with hyperprolactinemia or other non-DHT stimuli. Indeed, sulpiride-induced BPH mimics drug-induced hyperprolactinemia in humans (e.g., psychiatric patients on D2 blockers) and the age-associated rise of prolactin (Tsvetkov et al., 2020).

Importantly, unlike classic testosterone/DHT models, this system does not rely on 5α-reductase activation. For example, standard therapy with finasteride (a DHT blocker) does not prevent sulpiride-driven growth or inflammation; by contrast, rapamycin (which targets cell proliferation pathways) is effective. In other words, the sulpiride model is “androgen-independent”, and prostate enlargement occurs despite normal DHT levels. This is also a limitation; pathways dependent on DHT (and thus many BPH therapies) are not engaged in this model. Hence, one cannot test 5α-reductase inhibitors or castration effects here. Other limitations include the artificial nature of high-dose sulpiride, which may present off-target effects and interspecies differences.

Nevertheless, by using non-castrated rats, the sulpiride model preserves the natural hormone interplay and has proven to be reproducible across many studies. It provides a valuable complement to androgen-driven models, highlighting the role of prolactin and stromal signalling in BPH. (Lim et al., 2025; Van Coppenolle et al., 2001).

11. Comparisons Of TP- and Sulpiride-induced BPH Models

In rat models of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), testosterone propionate (TP) and sulpiride induce prostatic growth via distinct hormonal routes. Critically, the experimental setup differs: TP-induced BPH is typically generated in castrated rats, whereas sulpiride-induced BPH is generally performed in intact (non-castrated) animals. For example, Li et al. (2018) castrated male rats and then injected TP (25 mg/kg subcutaneously) once daily for four weeks to induce BPH. Similarly, Lee et al. (2024) used castrated Sprague–Dawley rats with TP (3 mg/kg/day, s.c.) for 28 days to model BPH. In contrast, sulpiride models do not require castration. Indeed, Tahiri-Zagret and Oria (1979) found that sulpiride’s prostatic effects were blunted or absent in castrated rats; intact males showed marked gland enlargement, but castrated males showed almost no change. Thus, castration is required for the TP model (to eliminate endogenous androgen and then reintroduce a defined androgen stimulus). In contrast, the sulpiride model relies on hyperprolactinemia acting within an intact androgen milieu.(Tahiri-Zagret & Oria, 1979).

The primary hormones involved differ as well. Androgens drive TP models; exogenous testosterone propionate (TP) raises systemic testosterone and its potent metabolite, dihydrotestosterone (DHT). DHT, generated by 5α-reductase in the prostate, strongly activates the androgen receptor (AR). Jung et al. (2017) demonstrated that TP-treatment (with no additional estrogen) enlarged rat prostates and elevated both DHT levels and AR signalling. By contrast, the sulpiride model is driven by prolactin (PRL). Sulpiride chronically elevates pituitary PRL levels (Jung et al., 2017). Zheng et al. (2020) confirmed that 4-week sulpiride treatment significantly increased serum PRL (along with FSH and even testosterone), and this hyperprolactinemia produced prostate enlargement. In essence, the TP model exemplifies testosterone/DHT-driven hyperplasia. In contrast, the sulpiride model exemplifies a prolactin-mediated hyperplasia (with prolactin acting as a paracrine prostatic growth factor on top of background androgens).

Despite different upstream signals, both models converge on androgen receptor (AR) signalling in the prostate. In the TP model, AR is directly activated by high androgen levels. DHT-AR binding induces proliferation and survival gene programs. For instance, Jung et al. noted that TP-implanted rats had upregulated AR expression and androgen-responsive co-activators in prostate tissue. In the sulpiride model, AR is engaged more indirectly. Prolactin can potentiate AR signalling. Zheng et al. found that sulpiride-treated rats showed AR upregulation in the lateral lobe. Moreover, Van Coppenolle et al. (2001) showed that sulpiride-induced prostate growth required androgen support. In castrated rats, prolactin delivered via sulpiride alone did not induce growth; a growth response occurred only when testosterone (T) or DHT was additionally supplied (Thompson & Heidger, 1978). This indicates that PRL-driven hyperplasia is androgen-dependent. Mechanistically, both models increase prostatic survival signals. TP-BPH is associated with a higher Bcl-2/Bax ratio, while Van Coppenolle also reported that chronic hyperprolactinemia induced Bcl-2 overexpression in the lateral prostate(Van Coppenolle et al., 2001). In summary, AR involvement is crucial in both models, but TP acts as the direct AR ligand, whereas sulpiride-induced PRL amplifies AR signalling (and possibly ER signalling as well).

Estrogen signalling via ERα also diverges: in the TP-derived estradiol model, estradiol predominantly engages ERα through local aromatisation, whereas in the sulpiride-induced hyperprolactinemia model, PRL may indirectly enhance ERα activation by upregulating aromatase or ER expression, thereby modifying the pattern and magnitude of estrogen-dependent responses (Chen et al., 2010). Interestingly, Jung et al. reported that TP treatment alone increased ERα expression in hyperplastic prostate tissue (along with AR) (Jung et al., 2017). However, this ERα upregulation is secondary to excess androgen and local aromatisation. By contrast, the sulpiride model strongly induces ERα. Zheng et al. observed that the lateral prostates of sulpiride-treated rats showed marked ERα overexpression (and ERβ downregulation) (Zheng et al., 2020). Thus, sulpiride-BPH features a hormonal milieu that is relatively high in estrogenic signalling (perhaps due to prolactin effects on aromatase and estrogen receptor regulation). In short, TP-BPH is mainly androgenic (with only modest ERα induction), whereas PRL-driven BPH notably upregulates ERα.

Both models are instructive for different aspects of human disease. The TP model shows the centrality of androgens; clinical BPH is AR-dependent (5α-reductase inhibitors shrink human BPH). The sulpiride (hyperprolactinemia) model highlights additional modulators. Clinical data show that prolactin receptors are present in the human prostate, and PRL can act as a prostatic mitogen. Prostate-specific PRL overexpression in transgenic mice causes BPH-like growth. Thus, while TP-BPH recapitulates pure androgenic growth, sulpiride-BPH models a scenario in which hormonal imbalance (high PRL in the setting of androgens) drives mixed stromal-epithelial enlargement. These mechanistic insights (AR vs. PRL/ERα pathways, epithelial vs. stromal proliferation) help in translating animal studies to human BPH pathophysiology and therapy.

12. Toxic Effect of Sulpiride on the Testis

Abd, Al-Juhaishi, and Jumma (2025) conducted a controlled, in vivo study to examine the impact of sulpiride—a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist on testicular structure and reproductive function in adult male rats. The study employed 30 Wistar male rats, aged 90-95 days and weighing 250–300 g, which were randomly assigned to three equal groups (n = 10 per group). Group 1 received 10 mg/kg of sulpiride, Group 2 received 25 mg/kg, and Group 3 served as the control (receiving normal saline), with all treatments administered via gavage over a defined period. Within 24 hours after treatment, blood samples were collected under isoflurane anaesthesia to measure serum levels of testosterone, prolactin, luteinising hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). Concurrently, testes and epididymides were harvested; left testes underwent histopathological analysis, while right testes plus epididymides were frozen to assess sperm parameters. Hormonal outcomes revealed dose-dependent endocrine disruption. Specifically, rats in the 25 mg/kg group (Group 2) exhibited a significant decrease in testosterone and LH (p < 0.05), as well as a significant increase in prolactin; FSH levels remained unchanged across all groups. Sperm analysis demonstrated that Group 2 exhibited significantly reduced sperm concentration and motility, along with increased sperm abnormalities and higher percentages of dead sperm, compared to both the lower-dose group and controls (p < 0.05). Histological examination further confirmed a dose-dependent deterioration of seminiferous tubule architecture. Moderate degeneration was observed in Group 1 (10 mg/kg). At the same time, severe tubule destruction was evident in Group 2, characterised by loss of spermatogenic cells and structural disruption, in contrast to the intact morphology seen in control rats. The study’s outcomes suggest that sulpiride induces hyperprolactinemia via D2 receptor antagonism, which, in turn, suppresses the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. The reduction in GnRH (Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone) release likely caused the decline in LH and testosterone, culminating in hypogonadism, impaired spermatogenesis, and testicular damage. Through comprehensive hormonal assays, sperm metrics, and histopathological evaluations, this study provides robust evidence that even moderate levels of sulpiride can produce significant testicular and reproductive harm in adult male rats (Abd, Al-Juhaishi, & Jumma, 2025)

Vieira et al. conducted a pivotal experimental study to assess the long-term effects of maternal lactational exposure to sulpiride on the reproductive and behavioural development of male rat offspring. The study examined whether sulpiride, a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist that may cause hyperprolactinemia and pass into breast milk, affects suckling pups. Lactating Wistar rats were split into three groups: control, 2.5 mg/kg/day sulpiride, and 25 mg/kg/day sulpiride, all treated orally from postnatal day 1 to 21. These doses simulated low and high clinical exposures. Male offspring were monitored until PND 90 to assess long-term reproductive and behavioural effects. At PND 90, histological and morphometric analysis showed dose-dependent testicular damage, with reduced seminiferous tubule volume, germinal epithelium height, and Leydig cell count in both sulpiride-exposed groups. Notably, the 25 mg/kg group exhibited a higher frequency of abnormal seminiferous tubules, suggesting substantial disruption to spermatogenesis and testicular architecture. This indicates that early-life exposure may lead to long-term, potentially irreversible changes. Vieira et al. concluded that lactational exposure to sulpiride causes long-term damage to male reproductive organs, even in the absence of behavioural changes. The results underscore the risks of using prolactin-elevating antipsychotics during lactation and highlight the testis as a critical target organ during developmental drug exposure (Vieira et al., 2013).

Oseko et al. (1985) conducted a controlled clinical study to investigate how sustained elevation of prolactin levels induced by Sulpiride affects the human HPT (Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Testicular) axis. Five healthy adult male volunteers received 300 mg/day of sulpiride orally for 78 days, resulting in maintained hyperprolactinemia (prolactin 71.6–95.3 ng/mL) in four out of five participants. The researchers sought to determine whether this endocrine disturbance impaired hypothalamic or pituitary responsiveness, with downstream consequences for luteinising hormone (LH) secretion. To assess hypothalamic and pituitary level function, the investigators performed three specific stimulation tests both before and during sulpiride treatment:

Clomiphene citrate (CC) test—measures the hypothalamic drive to increase endogenous GnRH and subsequent LH release.

Luteinising hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH) test—evaluates pituitary capacity to secrete LH in response to GnRH.

Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) test—assesses testicular Leydig cell responsiveness in testosterone production.

The CC test results indicated a progressive decline in LH response: while the ratio of LH released post-CC at 2 weeks of sulpiride treatment remained near normal (0.942 ± 0.073), by 60 days it had significantly decreased to 0.769 ± 0.121 (p < 0.05 vs. 2 weeks; p < 0.01 vs. baseline). This finding suggests that prolonged hyperprolactinemia inhibits hypothalamic GnRH release, thereby diminishing LH secretion over time. While LHRH and hCG test data were mentioned, the primary conclusion centred on the CC test, with less emphasis on pituitary and testicular responses. Nonetheless, impairment of LH release at the hypothalamic level implies that downstream effects, including reduced LH stimulation of Leydig cells, are likely to occur. The study, therefore, highlights the hypothalamus as an initial site of action where chronic prolactin elevation begins to impair HPT axis function, even if gonadal function remains promptly intact. Oseko et al. concluded that in healthy men, chronic sulpiride-induced hyperprolactinemia progressively suppresses the hypothalamic component of the HPT axis, primarily via reduced GnRH release. This effect shows dysfunction at the pituitary or testicular level. (Oseko et al., 1985)

The cumulative evidence from animal and human studies confirms that sulpiride, a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist, exerts profound, dose-dependent adverse effects on male reproductive health, primarily by disrupting the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. Abd, Al-Juhaishi, and Jumma (2025) demonstrated that sulpiride administration in adult male rats led to a cascade of hormonal and structural testicular impairments. The dose-dependent hyperprolactinemia induced by sulpiride corresponded with a significant suppression of luteinizing hormone (LH) and testosterone levels, along with clear histological evidence of seminiferous tubule degeneration and sperm abnormalities. These findings strongly implicate prolactin-mediated suppression of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) as a central mechanism leading to hypogonadism, impaired spermatogenesis, and testicular damage. Complementary insights from Vieira et al. (2013) underscore the long-term reproductive consequences of early-life sulpiride exposure. Maternal sulpiride administration during lactation caused irreversible testicular damage in male offspring by adulthood, as evidenced by reduced seminiferous tubule volume and disrupted germinal epithelium architecture. This suggests that developmental exposure during critical windows of sexual maturation poses heightened risks, even when behavioural parameters remain unchanged. The findings emphasise that prolactin-elevating antipsychotics can affect reproductive tissue permanently, with testicular structure and spermatogenesis being especially vulnerable. Human data from Oseko et al. (1985) further affirm this mechanistic pathway, showing that chronic sulpiride use in healthy men results in progressive suppression of LH release due to impaired hypothalamic GnRH activity. While pituitary and testicular functions initially appeared to be preserved, the decline in LH responsiveness following clomiphene stimulation provides early evidence of HPG axis dysregulation. This finding is critical because it validates animal models and confirms that hyperprolactinemia can be a silent but progressive threat to male fertility, even in clinical settings. Taken together, these studies establish a coherent model: sulpiride-induced hyperprolactinemia disrupts reproductive function by suppressing hypothalamic GnRH output, thereby impairing pituitary LH secretion and downstream testosterone synthesis. This hormonal imbalance culminates in histological testicular degeneration and spermatogenic failure. The reproductive risks associated with sulpiride are therefore both dose and duration-dependent, and the timing of exposure, especially during developmental windows, amplifies long-term harm. These insights highlight the need for clinical vigilance when prescribing prolactin-elevating antipsychotics to reproductive-age men and lactating women, and advocate for regular hormonal monitoring to preempt irreversible testicular dysfunction.

13. Toxic Effects of Sulpiride on the Liver

13.1. Evidence of Hepatotoxicity

Clinical Case Studies

A 2023 case report in the Scholars Journal of Medical Case Reports described a 24-year-old male who developed fatigue and jaundice after four weeks of sulpiride (100 mg/day) for anxiety. Liver enzymes were markedly elevated (ALT: 550 IU/L, AST: 490 IU/L), accompanied by increased bilirubin levels. Investigations for viral, autoimmune, and metabolic liver diseases were negative. Imaging was normal, and liver biopsy showed eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltration, consistent with immunoallergic drug-induced liver injury (DILI). Management involved discontinuation of sulpiride and weekly monitoring, resulting in full recovery within 1 month. This case highlights the need for vigilance even with drugs of low hepatotoxic potential. (Snoussi et al., 2023).

Research, particularly in animal models, suggests that sulpiride may contribute to metabolic abnormalities that, in turn, indirectly affect liver health. Studies in rats have shown that chronic administration of sulpiride can induce fatty liver disease by phosphorylating insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) at Serine 307, resulting in insulin resistance in adipose tissue. This mechanism highlights a potential link between sulpiride, insulin resistance, and hepatic triglyceride accumulation, which could contribute to broader liver dysfunction (Zhou et al., 2018).

A 59-year-old woman developed jaundice and signs of liver damage after ten months on sulpiride. A liver biopsy revealed cholestatic hepatitis and ductopenia, a loss of bile ducts, suggesting a destructive cholangitis. The absence of typical allergic reactions, such as rash or fever, pointed to a toxic rather than an immune-mediated drug effect, possibly due to a genetic predisposition affecting sulpiride metabolism. Despite discontinuing sulpiride and starting supportive treatment with cholestyramine, vitamin K, and vitamin D, her jaundice persisted, leading to evaluation for a liver transplant (Villari et al., 1995).

14. Management

Early detection and immediate withdrawal of the offending drug remain the cornerstone of managing sulpiride-induced liver injury. Since there is no specific antidote for most cases of drug-induced liver injury (DILI), treatment typically focuses on supportive care. This may involve relieving symptoms such as jaundice and itching and, in more severe presentations, addressing complications such as impaired blood clotting or hepatic encephalopathy. In rare but serious scenarios, such as progressive liver failure or persistent cholestasis that evolves into biliary cirrhosis, liver transplantation may become the only life-saving option, as seen in the reported case of the 59-year-old woman who developed bile ductopenia after long-term sulpiride therapy.

15. Toxic Effects of Sulpiride on the Kidney

15.1. Renal Elimination and Risk of Accumulation

The primary route of excretion of sulpiride is the kidney, and it is excreted unchanged (Bressolle, Bres, & Mourad, 1989; Mohammed et al., 2020). Multiple pharmacokinetic studies have confirmed that the hepatic metabolism of sulpiride is negligible, and the drug is primarily eliminated through glomerular filtration and active tubular secretion (Wiesel et al., 1980). Consequently, any impairment in renal function, whether due to age-related decline or underlying disease, may result in drug accumulation. In a risk assessment study of the effect of sulpiride on patients with schizophrenia, it was observed that the elderly group, despite administration of lower doses, had a lower clearance of sulpiride compared to the younger group. This was attributed to a physiological decline in glomerular filtration rate (Mauri et al., 1996).

15.2. Experimental and Clinical Evidence of Renal Effects

The renal effects of sulpiride have been studied in both animal models and human volunteers. One of the functions of dopamine is to promote the excretion of sodium in the urine to regulate blood pressure. However, sulpiride antagonises dopamine, thus inhibiting its role in sodium balance. A study examined the dissociation between sulpiride effects on renal hemodynamics and its influence on natriuresis during dopamine infusion. In this study, sulpiride significantly reduced urinary sodium excretion (FENa+). Still, it did not significantly alter baseline renal plasma flow (ERPF), glomerular filtration rate (GFR), or filtration fraction (FF). The effect of sulpiride on natriuresis suggests interference with dopaminergic regulation of tubular function, particularly proximal tubular sodium handling (Smit et al., 1990). These findings were consistent across individuals pretreated with alpha-adrenergic blockers (prazosin or phentolamine), suggesting that sulpiride’s natriuretic antagonism was independent of alpha-adrenergic mechanisms. Instead, the effect was attributed to sulpiride’s antagonism of dopamine at renal tubular DA1 and DA2 receptors, which mediate vasodilation, natriuresis, and inhibition of aldosterone secretion (Smit et al., 1990).

Interestingly, while sulpiride did not interfere with dopamine-induced vasodilation, its suppression of sodium excretion was robust, indicating a more pronounced effect on dopamine’s tubular actions than on its vascular effects. The anti-natriuretic effect occurred without significant changes in renal perfusion parameters, suggesting a localised tubular action. This reinforces the hypothesis that sulpiride can affect electrolyte handling by antagonising endogenous dopamine, even at therapeutic concentrations (Smit et al., 1990).

In a study comparing the effects of sulpiride and clozapine (another antipsychotic drug) on kidney function, renal function tests showed that sulpiride alone had no significant effect on serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, urea, or uric acid levels, unlike clozapine. It was observed that sulpiride alone induced mild congestion of the peritubular capillaries with cloudy swelling of the epithelial lining of some renal tubules, accompanied by obliteration of the lumen. Sulpiride in combination with clozapine showed mild histological lesions as evidenced by mild vacuolation of the epithelial lining of the renal tubules. Co-administration attenuated clozapine-induced nephrotoxicity, suggesting a modulatory interaction, albeit without direct sulpiride toxicity, which may indicate that effects vary when sulpiride is used in combination or may instead confer protection under certain conditions (Mohammed et al., 2020).

In a study to check for the response of an isolated rat kidney to a mixed solution of amino acids using sulpiride as one of the three renal autocoid inhibitors, sulpiride was found to partially inhibit the effects of the mixed amino acid solution on inulin clearance and renal perfusate flow and that it entirely inhibited the reduction in fractional albumin excretion (el Sayed, Haylor, & el Nahas, 1991).

15.3. Interaction with Dopaminergic Pathways

Sulpiride’s interference with renal dopaminergic pathways is increasingly recognised as central to its potential renal effects. Dopamine, produced locally in the kidney, plays a vital role in sodium excretion, blood pressure regulation, and overall renal homeostasis. Sulpiride, by antagonising dopamine receptors, may disrupt this balance, particularly under conditions requiring compensatory natriuresis (e.g., volume overload, high salt intake).

Furthermore, studies in animal models have suggested that sulpiride may exhibit dose-dependent antagonism of dopamine-induced renal vasodilation, although human data remain inconclusive. Variation in sulpiride’s impact on the renal vasculature across species and study designs underscores the need for caution when extrapolating preclinical findings to clinical settings. In a study investigating the effects of dopamine and sulpiride on regional blood flow in the rat kidney, sulpiride was found to reduce renal cortical blood flow (Chapman et al., 1980). A study in humans demonstrated that (+) sulpiride is a dopamine receptor antagonist in the kidney, resulting in reduced renal blood flow, increased sodium excretion, and increased glomerular filtration, thereby interfering with dopamine activity (Schmidt et al., 1983). Agnoli and colleagues demonstrated that sulpiride, particularly the L-enantiomer, blocks dopamine’s beneficial renal effects (vasodilation, increased GFR, natriuresis) by antagonising D2 receptors (Agnoli et al., 1989).

15.4. Pharmacokinetics and Risk of Accumulation

Unlike many antipsychotics, nearly all sulpiride is excreted unchanged via the kidneys. In early pharmacokinetic studies, approximately 70% of a dose was recovered unmodified in human urine. With renal impairment, the elimination half-life and systemic exposure increased substantially, while renal clearance diminished, necessitating dose reductions of 35–70% or extended dosing intervals in such patients. This places elderly patients or those with chronic kidney disease at significant risk of drug accumulation and potential toxicity (Bressolle, Bres, & Mourad, 1989). In a study to understand the distribution of sulpiride in the body and its pharmacodynamics using Positron Emission Tomography (PET), it was observed that the kidneys showed lower sulpiride uptake than other organs, such as the bladder, liver, and gallbladder. Sulpiride was also found not to be properly cleared by the kidneys in mice with organic cation transporters (Takano et al., 2017).

15.5. Role of Renal Transporters

A breakthrough study demonstrated that sulpiride is a substrate for and is managed by human carnitine OCT2, organic cation transporters 1 and 2 (OCTN1/2), and human multidrug and toxin extrusion protein 1 and 2 (hMATE1/2-K), transporters integral to proximal tubular secretion. OCT 2 mediates the uptake of sulpiride from the bloodstream to the proximal tubule cells/renal cells. At the same time, MATEs facilitate the efflux of sulpiride from proximal tubular cells into the renal lumen, allowing for excretion into urine, and OCTN participates in both renal excretion and absorption. Disruption or saturation of these systems, due to drug interactions or genetic polymorphisms, may increase intrarenal accumulation and systemic retention. The accumulation of sulpiride was reduced in mouse primary renal tubular cells by OCT2 and OCTN. This study suggests that polypharmacy scenarios involving OCT2/MATE inhibitors (e.g., cimetidine) could further impede sulpiride elimination (Li et al., 2017; Takano et al., 2017).

15.6. Cellular Pathways and Molecular Effects

Recent mechanistic work reveals that sulpiride disrupts canonical pathways in proximal tubular cells. In a study investigating the interaction between the dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) and the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathways, Sulpiride was found to decrease β-catenin phosphorylation and enhance TCF/LEF transcriptional activity, potentially altering cellular proliferation and repair responses (Han et al., 2019). This suggests that chronic D2 blockade may perturb renal cellular homeostasis, increasing susceptibility to injury or maladaptive repair.

15.7. Case Reports and Clinical Implications

A case report revealed that Sulpiride, when taken in higher doses, may trigger a cascade of reactions that severely affect the kidneys. After the withdrawal of Sulpiride, the renal function returned to normal (Toprak et al., 2005). A reported case described a 46-year-old man who developed neuroleptic malignant syndrome, characterised by hyperpyrexia, severe muscle rigidity, altered consciousness, autonomic instability, rhabdomyolysis, and focal tubulitis on renal biopsy, culminating in acute myoglobinuric renal failure following the discontinuation of sulpiride and maprotiline (Kiyatake et al., 1991). In a documented case of sulpiride overdose, a 23-year-old male with schizophrenia ingested an excessive dose of sulpiride. He subsequently developed severe rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure, requiring hospitalisation (Na, 2007).

16. Toxic Effect of Sulpiride on the Brain

Schizophrenia is a complex neuropsychiatric syndrome that comprises a group of severe mental illnesses of unknown aetiology. The basis for the pathology of schizophrenia is the hyperfunction of the dopamine (DA) system in the mesolimbic and mesocortical pathways, accompanied by metabolic disorders of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) (Zhang et al., 2022). Somatoform disorders are a group of conditions that comprise physical symptoms for which no adequate medical explanation can be found. These somatic complaints are severe enough to cause persistent distress for the patient and to impair their ability to function in everyday life. They are also likely to be associated with the development of other mental disorders. The diagnostic class of somatoform disorders is relatively new, being first introduced into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) classification in 1980 (Rouillon et al., 2001).

16.1. Mechanism of Action and Limitation

Dopamine is the primary catecholamine neurotransmitter in the brain, with its receptors located on both presynaptic and postsynaptic membranes. Sulpiride is believed to primarily modulate the Mesocorticolimbic dopamine system (MCLDA), which serves as the primary reward pathway (Ohmann, Kuper, & Wacker, 2020). Sulpiride administration can produce complex effects, influenced in part by the anatomical location of dopamine D2 receptors (D2R), whether presynaptic or postsynaptic (Ford, 2014). Lower doses of sulpiride primarily block presynaptic D2/D3 auto receptors, leading to increased dopamine release and synthesis in some brain areas (Ohmann, Kuper, & Wacker, 2020; Kuroki et al., 1999). In contrast, higher doses are thought to mainly inhibit postsynaptic D2 receptors, thereby reducing dopamine release and signalling within the brain (Boschen, Andreatini, & da Cunha, 2015). Consequently, elevated dosages of sulpiride may be employed to manage schizophrenia, a condition associated with excessive dopaminergic activity. Mohyeldin et al. (2021) report that sulpiride exerts its antidepressant effects primarily by selectively inhibiting dopamine and serotonin receptors across the brain. Compared to other antidepressant agents, sulpiride has attracted considerable attention due to its favourable safety profile, minimal extrapyramidal side effects, reduced affinity for non-target neuronal receptors, demonstrated efficacy, and cost-effectiveness.

16.2. Clinical Cases

Peng et al. conducted a study utilising sulpiride to examine its effects on reversing chronic corticosterone (CORT) exposure in mice (Peng et al., 2021). Chronic CORT administration resulted in anxiety-like behaviours and impaired food-seeking, attributed to reduced excitability and diminished excitatory synaptic transmission in ventral tegmental area (VTA) dopamine neurons. This reduction was associated with elevated somatodendritic dopamine levels that activated inhibitory D2 receptor signalling. Direct administration of sulpiride into the VTA restored neuronal excitability and glutamatergic transmission onto dopamine neurons. In behavioural assessments, sulpiride alleviated anxiety-like symptoms and rescued CORT-induced deficits in food-seeking behaviour within mildly aversive environments, although it did not improve operant motivation task performance. These results indicate that sulpiride mitigates the inhibitory action of excess dopamine via D2 receptors, offering potential therapeutic strategies for stress-related neuropsychiatric conditions. A study by Rouillon et al. (2001) examining the effects of sulpiride on somatoform disorders found that sulpiride predominantly inhibits limbic dopamine receptors, exhibiting minimal impact on striatal dopamine receptors. This selective receptor activity likely contributes to its low incidence of extrapyramidal side effects. At lower doses, sulpiride preferentially antagonises presynaptic receptors, thereby increasing dopaminergic transmission, which may underlie its activating properties and broad therapeutic efficacy. Its effectiveness in treating somatoform and functional disorders is attributed to its capacity to selectively block dopamine activity in regions such as the area postrema, the hypothalamic-hypophyseal system, and the mesolimbic pathways.

Table 1.

Summary of Research Findings on Sulpiride Toxicities in the Testis, Liver, Kidney, and Brain.

Table 1.

Summary of Research Findings on Sulpiride Toxicities in the Testis, Liver, Kidney, and Brain.

| S/N |

Study/Model |

Findings |

References |

| 1 |

In vivo controlled study in adult male Wistar rats |

High doses of sulpiride (25 mg/kg) increased prolactin, reduced testosterone and LH, caused low sperm count, poor motility, abnormal forms, and severe testicular damage, while low-dose effects were milder and controls remained normal. |

(Abd, Al-Juhaishi, & Jumma, 2025) |

| 2 |

Maternal sulpiride and testis damage in male offspring |

At sulpiride (25mg/kg), male offspring from sulpiride-treated mothers showed dose-dependent testis damage, with smaller seminiferous tubules, thinner germ cell layers, and fewer Leydig cells |

(Vieira et al., 2013) |

| 3 |

Controlled clinical study in healthy adult males |

Sulpiride (300 mg/day for 78 days) caused sustained hyperprolactinemia (71.6–95.3 ng/mL) in 4/5 participants. |

(Oseko et al., 1985) |

| 4 |

An animal study (rat model) |

Chronic administration of sulpiride induced fatty liver disease by increasing phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) at Serine 307, leading to insulin resistance in adipose tissue, promoting hepatic triglyceride accumulation. |

(Zhou et al., 2018)

|

| 5 |

A case study |

Sulpiride (100 mg/day) increased ALT, AST, and bilirubin levels, along with eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltration. |

(Snoussi et al., 2023). |

| 6 |

A case study |

A patient developed jaundice and severe liver injury after 10 months on sulpiride. Liver biopsy revealed cholestatic hepatitis with ductopenia, indicating destructive cholangitis. |

(Villari et al., 1995) |

| 7 |

A case study |

Sulpiride causes a marked reduction in sodium excretion by blocking renal DA1 and DA2 receptors, impairing dopamine-mediated natriuresis without affecting renal blood flow or filtration. |

(Smit et al., 1990) |

| 8 |

Animal study comparing sulpiride vs. clozapine |

Sulpiride alone did not cause significant changes in kidney function markers but did produce mild renal tubular injury, characterised by peritubular congestion and cloudy swelling of tubular cells. When combined with clozapine, it caused only mild tubular vacuolation and even appeared to lessen clozapine-related nephrotoxicity. |

(Mohammed et al., 2020) |

| 9 |

An isolated rat kidney study |

Sulpiride completely inhibited the amino acid–induced reduction in fractional albumin excretion |

(el Sayed, Haylor, & el Nahas, 1991). |

| 10 |

An animal study |

Sulpiride reduced renal cortical blood flow |

(Chapman et al., 1980) |

| 11 |

A case study |

Sulpiride reduced renal blood flow, increased sodium excretion, and GFR |

(Schmidt et al., 1983) |

| 12 |

A case study |

L-Sulpiride blocked dopamine-induced vasodilation, GFR increase, and natriuresis |

(Agnoli et al., 1989) |

| 13 |

A case study |

A 46-year-old man developed neuroleptic malignant syndrome after stopping sulpiride and maprotiline, showing hyperpyrexia, muscle rigidity, altered consciousness, autonomic instability, and acute myoglobinuric renal failure indicated by focal tubulitis on renal biopsy. |

(Kiyatake et al., 1991) |

| 14 |

A case study |

Severe rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure following sulpiride overdose in a 23-year-old male with schizophrenia, requiring hospitalisation. |

(Na, 2007) |

| 15 |

An animal study |

Sulpiride restored neuronal function, reduced anxiety-like behaviour, and rescued food-seeking, but not operant motivation. |

(Peng et al., 2021) |

| 16 |

A Clinical Study |

Sulpiride shows selective limbic dopamine blockade with minimal striatal effect, explaining low EPS risk. Low doses block presynaptic receptors, enhancing dopaminergic transmission. |

(Rouillon et al., 2001) |

17. Limitations and Gaps in the Reviewed Studies

Beyond hormones, immune and inflammatory pathways are poorly characterised in BPH models. Chronic inflammation is a hallmark of human BPH (Zhang et al., 2020), but most TP- or sulpiride-based studies do not quantify immune mediators. Several reports indicate pronounced inflammation when these models are challenged. For example, Bello et al. (2023) found that a high-salt diet in TP-treated Wistar rats markedly elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8) and COX-2 expression in the prostate (Bello, Omigbodun, & Morhason-Bello, 2023). Similarly, Van Coppenolle et al. (2001) demonstrated that chronic sulpiride administration (40 mg/kg) induces lateral lobe enlargement accompanied by inflammation in Wistar rats. Zhang et al. (2020) showed in an autoimmune prostatitis (EAP) model that inflammation drives stromal expansion. EAP-treated rats exhibited significantly more CD3+ T-cell and CD68+ macrophage infiltration, higher TGF-β1 and RhoA/ROCK signalling, and increased extracellular matrix deposition compared to hormone-only rats (Zhang et al., 2020). These findings imply that even androgen-induced BPH models should be profiled for immune activity.

Future studies should therefore systematically measure inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-17), chemokines, and cyclooxygenases; leukocyte infiltrates (T cells, macrophages, mast cells) by IHC or flow cytometry; and oxidative stress markers (ROS levels, MDA, antioxidant enzymes). For instance, Zhang et al. noted that TP treatment alone elevates oxidative/hypoxic stress (increased HIF-1α, ROS), which can, in turn, trigger inflammation. Profiling both TP- and sulpiride-induced prostates in parallel would clarify how each model engages the immune axis. In summary, a significant gap exists in the lack of integrated immunophenotyping in BPH models, which often lack cytokine panels and immune cell counts, thereby missing opportunities to connect rat models to the inflamed microenvironment of human BPH.

Figure 2.

Mechanistic overview of sulpiride-induced benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) through the hypothalamic-pituitary and prostatic signalling pathway. Sulpiride blocks dopamine receptors, preventing dopamine’s inhibitory effect on prolactin release and causing hyperprolactinemia, which then activates prolactin receptors in prostatic cells, triggering JAK2–STAT5 signalling to promote nuclear transcription and prostatic epithelial and stromal proliferation. An increased prolactin level further stimulates stromal–epithelial interactions, inducing mesenchymal cells to release growth and inflammatory mediators, such as FGF-2, FGF-7, TGF-β1, TGF-β2, IGF-I, CCL3, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-15, which enhance epithelial–mesenchymal transition, stromal expansion, and macrophage infiltration. Together with androgen-dependent DHT–AR activation, these pathways synergistically increase prostatic epithelial and stromal growth, contributing to the development of BPH. Created in BioRender by AbdullahSanusi, 2025.

Figure 2.

Mechanistic overview of sulpiride-induced benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) through the hypothalamic-pituitary and prostatic signalling pathway. Sulpiride blocks dopamine receptors, preventing dopamine’s inhibitory effect on prolactin release and causing hyperprolactinemia, which then activates prolactin receptors in prostatic cells, triggering JAK2–STAT5 signalling to promote nuclear transcription and prostatic epithelial and stromal proliferation. An increased prolactin level further stimulates stromal–epithelial interactions, inducing mesenchymal cells to release growth and inflammatory mediators, such as FGF-2, FGF-7, TGF-β1, TGF-β2, IGF-I, CCL3, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-15, which enhance epithelial–mesenchymal transition, stromal expansion, and macrophage infiltration. Together with androgen-dependent DHT–AR activation, these pathways synergistically increase prostatic epithelial and stromal growth, contributing to the development of BPH. Created in BioRender by AbdullahSanusi, 2025.

18. Conclusions

The testosterone propionate (TP) and sulpiride models induce BPH in rats via distinct mechanisms. TP drives prostatic overgrowth via classic androgen signalling: exogenous testosterone is locally converted to dihydrotestosterone, activating the androgen receptor and yielding marked epithelial hyperplasia in the ventral prostate lobe. By contrast, sulpiride causes hyperprolactinemia, which preferentially stimulates proliferation in the lateral (and dorsal) lobes. In the sulpiride model, both epithelial and stromal compartments expand—for example, stromal markers such as vimentin and fibronectin are strongly upregulated in lateral lobes—and inflammatory changes (immune-cell infiltration) are evident in the lateral prostate. Thus, TP-induced BPH is predominantly an androgen-driven, ventral-epithelial hyperplasia, whereas sulpiride-induced BPH is a prolactin-driven proliferation of both stroma and epithelium in the lateral lobes.

The choice of model should be tailored to the research question. For studies targeting androgenic mechanisms, such as testing 5α-reductase inhibitors or anti-androgen compounds, the TP model is most appropriate, as it elicits pronounced AR-mediated epithelial growth. In contrast, investigations of prolactin signalling, estrogenic crosstalk, or inflammation-related pathways will benefit from the sulpiride model. This model induces prolactin-dependent lateral-lobe hyperplasia and an inflammatory microenvironment, neither of which occurs in the TP paradigm. By aligning the model with the biological axis of interest, investigators can more directly translate findings to human BPH. In summary, TP- and sulpiride-induced BPH in rats are distinct yet complementary.

Authors Contribution: Conceptualisation of the study. All authors SO, EMP, HAA, IOA, VOE, AAS, OMO, UA, JOB, MTO, APA, CA, EOO, AKO, OOO) participated in developing the review methodology and interpreting the data. Data analysis: EMP, HAA, CA, IOA, VOE, AAS, OMO, UA, and JOB, conducted the research and preliminary data analysis and drafted the original manuscript. HAA, CA, EMP, IOA, VOE, AAS, OMO, UA, and JOB. Supervision SO EOO, AKO, and OOO. Proof checks data for errors SO, CA, EOO, AKO, and OOO. The manuscript was revised by SO EOO, CA, AKO, and OOO. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors privately funded this research through their own contributions and received no external grants from funding agencies in the commercial, not-for-profit, or public sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge Chukwuebuka S. Asogwa for his editorial assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Ethical Approval: Not Applicable.

Consent to Participate: Not applicable.

References

- Abd, A. A.; Al-Juhaishi, O. A.; Jumma, Q. S. Effects of sulpiride on the Reproductive System of Male Rats after Puberty. World’s Veterinary Journal 2025, 15(1), 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoli, G. C.; Borgatti, R.; Cacciari, M.; Garutti, C.; Ikonomu, E.; Lenzi, P. Antagonistic effects of sulpiride--racemic and enantiomers--on renal response to low-dose dopamine infusion in normal women. Nephron 1989, 51(4), 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H. K.; Lee, H. S.; Park, J. Y.; Kim, D. K.; Kim, M.; Hwang, H. S.; Kim, J. W.; Ha, J. S.; Cho, K. S. Androgen deprivation therapy may reduce the risk of primary open-angle glaucoma in patients with prostate cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Prostate Int 2021, 9(4), 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanni, O. O.; Abiola, O. J.; Adaramoye, O. A. Methyl Jasmonate Ameliorates Testosterone Propionate-induced Prostatic Hyperplasia in Castrated Wistar Rats. Phytother Res 2017, 31(4), 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrimani, D. S. R.; Brito, M. M.; Rui, B. R.; Nichi, M.; Vannucchi, C. I. Reproductive and endocrinological effects of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia and finasteride therapy in dogs. Sci Rep 2020, 10(1), 14834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, I. I.; Omigbodun, A.; Morhason-Bello, I. Common salt aggravated pathology of testosterone-induced benign prostatic hyperplasia in adult male Wistar rat. BMC Urology 2023, 23(1), 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovskaya, T. G.; Fomina, T. I.; Ermolaeva, L. A.; Vychuzhanina, A. V.; Pakhomova, A. V.; Poluektova, M. E.; Shchemerova, Y. A. Comparative evaluation of the efficiency of prostatotropic agents of natural origin in experimental benign prostatic hyperplasia. Bull Exp Biol Med 2013, 155(1), 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschen, S. L.; Andreatini, R.; da Cunha, C. Activation of postsynaptic D2 dopamine receptors in the rat dorsolateral striatum prevents the amnestic effect of systemically administered neuroleptics. Behav Brain Res 2015, 281, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressolle, F.; Bres, J.; Mourad, G. Pharmacokinetics of sulpiride after intravenous administration in patients with impaired renal function. Clin Pharmacokinet 1989, 17(5), 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calogero, A. E.; Burgio, G.; Condorelli, R. A.; Cannarella, R.; La Vignera, S. Epidemiology and risk factors of lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia and erectile dysfunction. Aging Male 2019, 22(1), 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, B. J.; Horn, N. M.; Munday, K. A.; Robertson, M. J. The actions of dopamine and of sulpiride on regional blood flows in the rat kidney. J Physiol 1980, 298, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, K.; Chen, K. E.; Walker, A. M. Prolactin and estradiol utilize distinct mechanisms to increase serine-118 phosphorylation and decrease levels of estrogen receptor alpha in T47D breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010, 120(2), 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, E. H.; Kim, J. W.; Kim, J. H.; Jeong, J. S.; Lim, J. H.; Boo, S. Y.; Ko, J. W.; Kim, T. W. Ageratum conyzoides Extract Ameliorates Testosterone-Induced Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia via Inhibiting Proliferation, Inflammation of Prostates, and Induction of Apoptosis in Rats. Nutrients 2024, 16(14). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colao, A.; Vitale, G.; Di Sarno, A.; Spiezia, S.; Guerra, E.; Ciccarelli, A.; Lombardi, G. Prolactin and prostate hypertrophy: a pilot observational, prospective, case-control study in men with prolactinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004, 89(6), 2770–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y.; Zou, H.; Qiao, G.; Lin, J.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Zhu, S. Bilateral mammary duct ectasia induced by sulpiride-associated hyperprolactinemia: A case report. Oncol Lett 2015, 9(5), 2181–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diokno, A. C.; Kunta, A.; Bowen, R. Testosterone and 5 Alpha Reductase Inhibitor (5ARI) in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH): A historical perspective. Continence 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.; Carbone, F.; Pacreau, E.; Diarra, S.; Luka, M.; Pigat, N.; Baures, M.; Navarro, E.; Anract, J.; Barry Delongchamps, N.; Cagnard, N.; Bost, F.; Nemazanyy, I.; Petitjean, O.; Hamai, A.; Menager, M.; Palea, S.; Guidotti, J. E.; Goffin, V. Cell Plasticity in a Mouse Model of Benign Prostate Hyperplasia Drives Amplification of Androgen-Independent Epithelial Cell Populations Sensitive to Antioxidant Therapy. Am J Pathol 2024, 194(1), 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- el Sayed, A. A.; Haylor, J.; el Nahas, A. M. Mediators of the direct effects of amino acids on the rat kidney. Clin Sci (Lond) 1991, 81(3), 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eruotor, O. H.; Ezendiokwere, O. E.; Oghenemavwe, E. L. Determination of effective dose of testosterone propionate for the induction of benign prostatic hyperplasia in Wistar rats. Scientia Africana 2025, 24(1), 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, C. P. The role of D2-autoreceptors in regulating dopamine neuron activity and transmission. Neuroscience 2014, 282, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gryder, B. E.; Akbashev, M. J.; Rood, M. K.; Raftery, E. D.; Meyers, W. M.; Dillard, P.; Khan, S.; Oyelere, A. K. Selectively targeting prostate cancer with anti-androgen equipped histone deacetylase inhibitors. ACS Chem Biol 2013, 8(11), 2550–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Bachman, E.; Vogel, J.; Li, M.; Peng, L.; Pencina, K.; Serra, C.; Sandor, N. L.; Jasuja, R.; Montano, M.; Basaria, S.; Gassmann, M.; Bhasin, S. The effects of short-term and long-term testosterone supplementation on blood viscosity and erythrocyte deformability in healthy adult mice. Endocrinology 2015, 156(5), 1623–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Konkalmatt, P.; Mokashi, C.; Kumar, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ko, A.; Farino, Z. J.; Asico, L. D.; Xu, G.; Gildea, J.; Zheng, X.; Felder, R. A.; Lee, R. E. C.; Jose, P. A.; Freyberg, Z.; Armando, I. Dopamine D(2) receptor modulates Wnt expression and control of cell proliferation. Sci Rep 2019, 9(1), 16861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C. W.; Chiu, Y. W.; Chen, P. J.; Yu, N. W.; Tsai, H. J.; Chang, C. M. Trends and factors in antipsychotic use of outpatients with anxiety disorders in Taiwan, 2005-2013: A population-based study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2019, 73(8), 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, T. R.; Chughtai, B.; Kaplan, S. A. Testosterone and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Asian J Androl 2015, 17(2), 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Li, T.; Zhao, L.; Sun, Y.; Mao, Z.; Xing, Y.; Wang, C.; Bo, Q. Treatment of antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Front Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1337274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.; Park, J.; Kim, H. L.; Youn, D. H.; Kang, J.; Lim, S.; Jeong, M. Y.; Sethi, G.; Park, S. J.; Ahn, K. S.; Um, J. Y. Vanillic acid attenuates testosterone-induced benign prostatic hyperplasia in rats and inhibits proliferation of prostatic epithelial cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8(50), 87194–87208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyatake, I.; Yamaji, K.; Shirato, I.; Kubota, M.; Nakayama, S.; Tomino, Y.; Koide, H. A case of neuroleptic malignant syndrome with acute renal failure after the discontinuation of sulpiride and maprotiline. Jpn J Med 1991, 30(4), 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroigaard, S. M.; Clemmensen, L.; Tarp, S.; Pagsberg, A. K. A Meta-Analysis of Antipsychotic-Induced Hypo- and Hyperprolactinemia in Children and Adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2022, 32(7), 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchay, M. S.; Mithal, A. Levosulpiride and Serum Prolactin Levels. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2017, 21(2), 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y. Use of saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) extract for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Food Sci Biotechnol 2019, 28(6), 1599–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Vignera, S.; Condorelli, R. A.; Russo, G. I.; Morgia, G.; Calogero, A. E. Endocrine control of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Andrology 2016, 4(3), 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, E. C.; Chang, C. H.; Kao Yang, Y. H.; Lin, S. J.; Lin, C. Y. Effectiveness of sulpiride in adult patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2013, 39(3), 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, K. P.; Huang, C. K.; Fang, L. Y.; Izumi, K.; Lo, C. W.; Wood, R.; Kindblom, J.; Yeh, S.; Chang, C. Targeting stromal androgen receptor suppresses prolactin-driven benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Mol Endocrinol 2013, 27(10), 1617–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. Y.; Shin, I. S.; Kyoung, H.; Seo, C. S.; Son, J. K.; Shin, H. K. alpha-Spinasterol from Melandrium firmum attenuates benign prostatic hyperplasia in a rat model. Mol Med Rep 2014, 9(6), 2362–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. Y.; Shin, I. S.; Seo, C. S.; Lee, N. H.; Ha, H. K.; Son, J. K.; Shin, H. K. Effects of Melandrium firmum methanolic extract on testosterone-induced benign prostatic hyperplasia in Wistar rats. Asian J Androl 2012, 14(2), 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. M.; Lee, S. M.; Song, J. Effects of Taraxaci Herba (Dandelion) on Testosterone Propionate-Induced Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia in Rats. Nutrients 2024, 16(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesovaya, E. A.; Kirsanov, K. I.; Antoshina, E. E.; Trukhanova, L. S.; Gorkova, T. G.; Shipaeva, E. V.; Salimov, R. M.; Belitsky, G. A.; Blagosklonny, M. V.; Yakubovskaya, M. G.; Chernova, O. B. Rapatar, a nanoformulation of rapamycin, decreases chemically-induced benign prostate hyperplasia in rats. Oncotarget 2015, 6(12), 9718–9727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cheng, D.; Li, P. Androgen receptor dynamics in prostate cancer: from disease progression to treatment resistance. Front Oncol 2025, 15, 1542811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Weng, Y.; Wang, W.; Bai, M.; Lei, H.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, H. Multiple organic cation transporters contribute to the renal transport of sulpiride. Biopharm Drug Dispos 2017, 38(9), 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y. J.; Kim, H. R.; Lee, S. B.; Kim, S. B.; Kim, D. H.; So, J. H.; Kang, K. K.; Sung, S. E.; Choi, J. H.; Sung, M.; Lee, Y. J.; Park, W. T.; Lee, G. W.; Kim, S. K.; Seo, M. S. Portulaca oleracea Extract Ameliorates Testosterone Propionate-Induced Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia in Male Sprague-Dawley Rats. Vet Med Sci 2025, 11(1), e70184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLeod, R. M.; Robyn, C. Mechanism of increased prolactin secretion by sulpiride. J Endocrinol 1977, 72(3), 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, M. C.; Bravin, S.; Bitetto, A.; Rudelli, R.; Invernizzi, G. A risk-benefit assessment of sulpiride in the treatment of schizophrenia. Drug Saf 1996, 14(5), 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, G. G.; Soliman, M. H. Synthesis, spectroscopic and thermal characterization of sulpiride complexes of iron, manganese, copper, cobalt, nickel, and zinc salts. Antibacterial and antifungal activity. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc 2010, 76(3-4), 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A. T.; Khalil, S. R.; Mahmoud, F. A.; Elmowalid, G. A.; Ali, H. A.; El-Serehy, H. A.; Abdel-Daim, M. M. The role of sulpiride in attenuating the cardiac, renal, and immune disruptions in rats receiving clozapine: mRNA expression pattern of the genes encoding Kim-1, TIMP-1, and CYP isoforms. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2020, 27(20), 25404–25414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohyeldin, S. M.; Samy, W. M.; Ragab, D.; Abdelmonsif, D. A.; Aly, R. G.; Elgindy, N. A. Precisely Fabricated Sulpiride-Loaded Nanolipospheres with Ameliorated Oral Bioavailability and Antidepressant Activity. Int J Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 2013–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na. Sorafenib. Reactions Weekly, &NA 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, T. M.; Ricke, W. A. Androgens and estrogens in benign prostatic hyperplasia: past, present and future. Differentiation 2011, 82(4-5), 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmann, H. A.; Kuper, N.; Wacker, J. A low dosage of the dopamine D2-receptor antagonist sulpiride affects effort allocation for reward regardless of trait extraversion. Personal Neurosci 2020, 3, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oseko, F.; Note, S.; Morikawa, K.; Endo, J.; Taniguchi, A.; Imura, H. Influence of chronic hyperprolactinemia induced by sulpiride on the hypothalamo-pituitary-testicular axis in normal men. Fertil Steril 1985, 44(1), 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Y.; Park, W. Y.; Song, G.; Jung, S. J.; Kim, B.; Choi, M.; Kim, S. H.; Park, J.; Kwak, H. J.; Ahn, K. S.; Lee, J. H.; Um, J. Y. Panax ginseng C.A. meyer alleviates benign prostatic hyperplasia while preventing finasteride-induced side effects. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1039622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Mathey, L. I.; Rojas-Duran, F.; Aranda-Abreu, G. E.; Manzo, J.; Herrera-Covarrubias, D.; Munoz-Zavaleta, D. A.; Garcia, L. I.; Hernandez, M. E. Effect of hyperprolactinemia on PRL-receptor expression and activation of Stat and Mapk cell signaling in the prostate of long-term sexually-active rats. Physiol Behav 2016, 157, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Xu, Q.; Liu, J.; Guo, S.; Borgland, S. L.; Liu, S. Corticosterone Attenuates Reward-Seeking Behavior and Increases Anxiety via D2 Receptor Signaling in Ventral Tegmental Area Dopamine Neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience 2021, 41(7), 1566–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouillon, F.; Rahola, G.; Van Moffaert, M.; Lopes, R. G.; Dunia, I.; Soma, D. S. T. S. O. M. A. t. D. Sulpiride in the treatment of somatoform disorders: results of a European observational study to characterize the responder profile. J Int Med Res 2001, 29(4), 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. S., S; R, R.; Nachiappa Ganesh, R. Cleistanthins A and B Ameliorate Testosterone-Induced Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia in Castrated Rats by Regulating Apoptosis and Cell Differentiation. Cureus 2022, 14(12), e32141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]