Submitted:

07 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

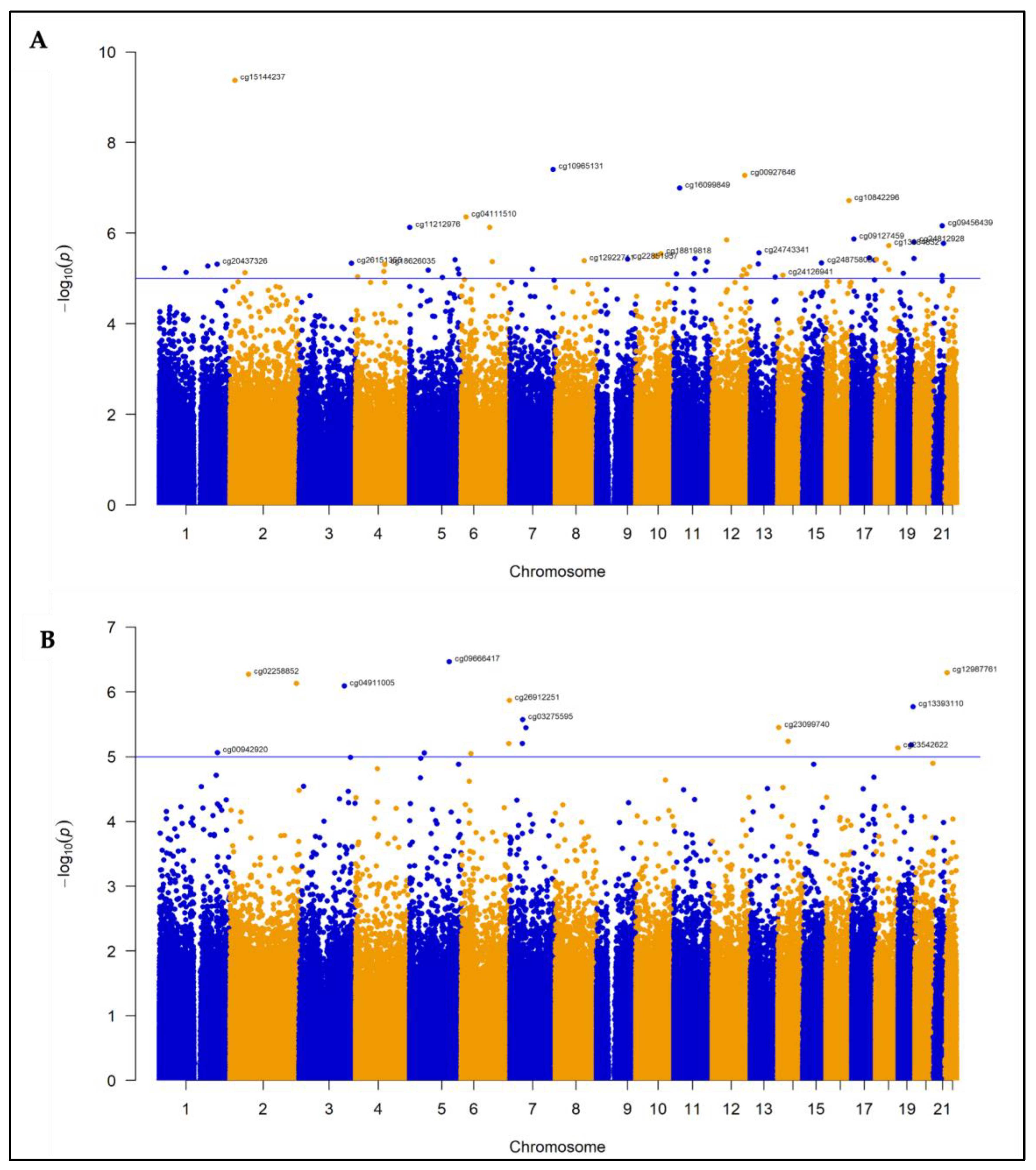

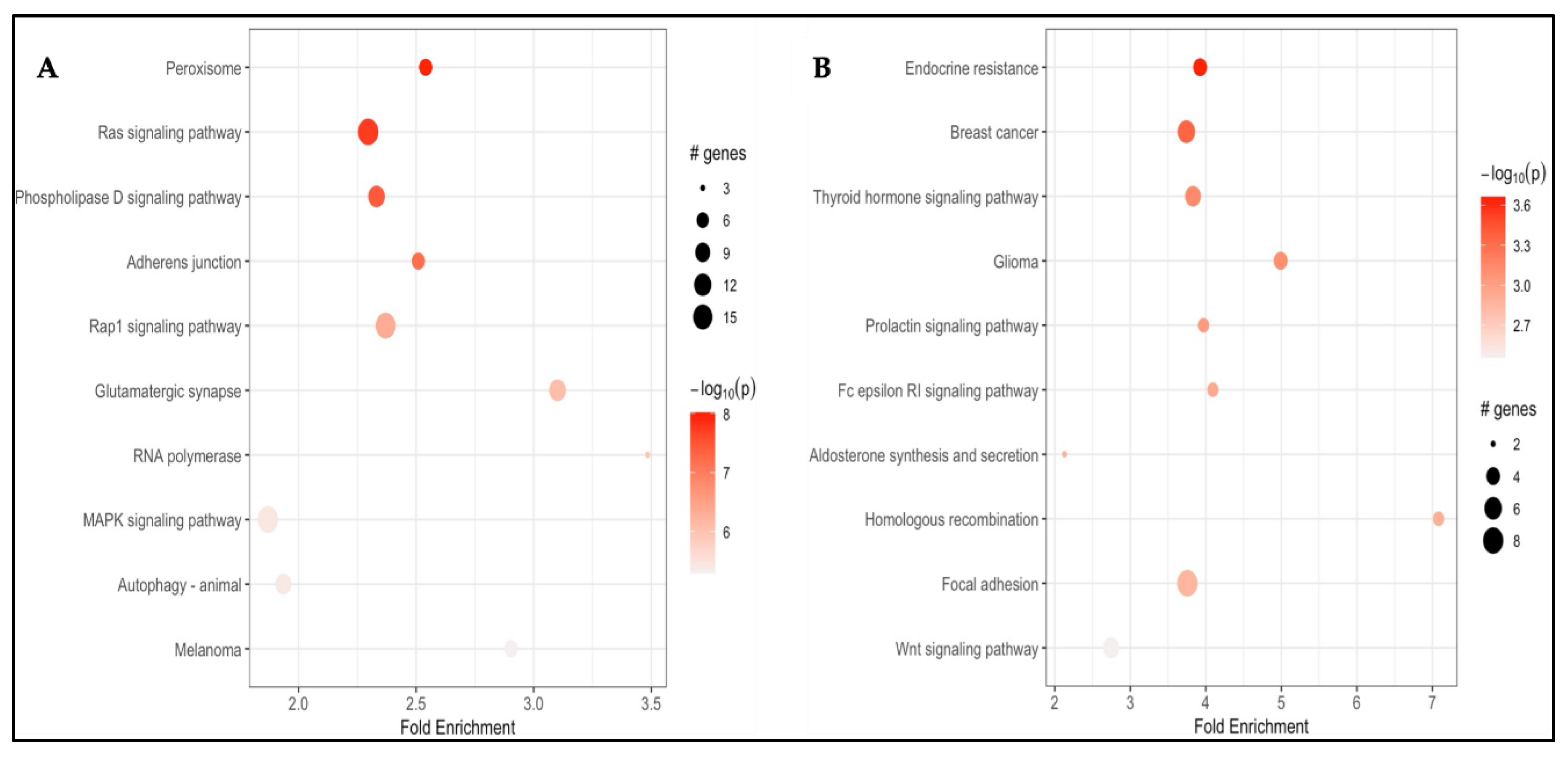

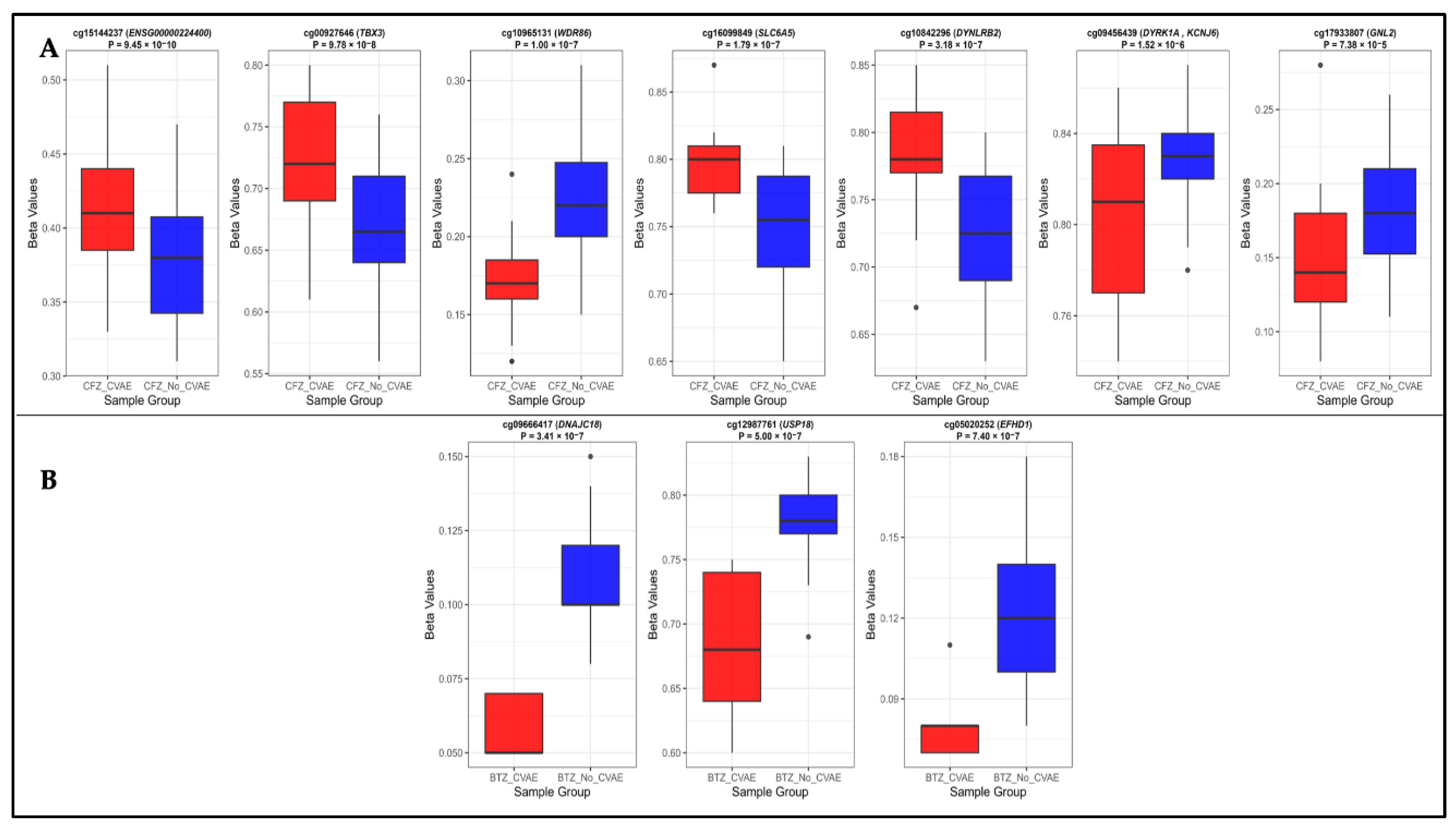

Background/Objectives: Carfilzomib (CFZ) and bortezomib (BTZ) are proteasome inhibitors used as the first-line therapy for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MM) but are associated with cardiovascular adverse events (CVAEs). This study aims to identify differentially methylated positions (DMPs) and regions (DMRs), and enriched pathways in patients who developed CFZ- and BTZ- related CVAEs. Methods: Baseline germline DNA methylation profiles from 79 MM patients (49 on CFZ and 30 on BTZ) in the Prospective Study of Cardiac Events During Proteasome Inhibitor Therapy (PROTECT) were analyzed. Epigenome-wide analyses within each group identified DMPs, DMRs, and enriched pathways associated with CVAEs compared with individuals without CVAEs. Results: Four DMPs were significantly associated with CFZ-CVAE: cg15144237 within ENSG00000224400 (p = 9.45x10−10), cg00927646 within TBX3 (p = 9.78x10−8), and cg10965131 within WDR86 (p = 1.00x10−7). One DMR was identified in the FAM166B region (p = 5.46x10−7). There was no evidence of any DMPs in BTZ-CVAE patients, however two DMPs and one DMR reached a suggestive level of significance (p < 1.00x10−5): cg09666417 in DNAJC18 (p = 3.41x10−7) and cg12987761 in USP18 (p = 5.00x10−7), and a DMR mapped to the WDR86/WDR86-AS1 region (p = 8.11x10−8). Meta-analysis did not find any significant DMPs, with the top CpG being cg17933807 in GNL2 (p = 7.38 x10−5). Pathway enrichment analyses identified peroxisome, MAPK, Rap1, adherens junction, phospholipase D, autophagy, and aldosterone-related pathways to be implicated in CVAEs. Conclusions: Our study identified distinct DMP, DMR, and pathway enrichment associated with CVAE, suggesting epigenetic contributors to CVAEs and supporting the need for larger validation studies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Methylation Profiling and Quality Control

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.3.2. Methylation Profiling Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Bassline Characteristics

3.2. Differentially Methylated Probes and Regions in CFZ-CVAE

3.2.1. DMPs

3.2.2. DMR

3.2.3. Pathway Enrichment Analysis

3.3. Differentially Methylated Probes and Regions in BTZ-CVAE

3.3.1. DMPs

3.3.2. DMRs

3.3.3. Pathway Enrichment Analysis

3.4. Meta-Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malard, F.; Neri, P.; Bahlis, N.J.; Terpos, E.; Moukalled, N.; Hungria, V.T.M.; Manier, S.; Mohty, M. Multiple myeloma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2024, 10, 45. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin 2025, 75, 10-45. [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, S.; Laubach, J.P.; Hideshima, T.; Chauhan, D.; Anderson, K.C.; Richardson, P.G. The proteasome and proteasome inhibitors in multiple myeloma. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2017, 36, 561-584. [CrossRef]

- Teicher, B.A.; Tomaszewski, J.E. Proteasome inhibitors. Biochem Pharmacol 2015, 96, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.K.; Rajkumar, S.V.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Masszi, T.; Špička, I.; Oriol, A.; Hájek, R.; Rosiñol, L.; Siegel, D.S.; Mihaylov, G.G.; et al. Carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2015, 372, 142-152. [CrossRef]

- Shirley, M. Ixazomib: First Global Approval. Drugs 2016, 76, 405-411. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Fradley, M.G. Cardiovascular Complications of Multiple Myeloma Treatment: Evaluation, Management, and Prevention. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2018, 20, 19. [CrossRef]

- Shah, C.; Bishnoi, R.; Jain, A.; Bejjanki, H.; Xiong, S.; Wang, Y.; Zou, F.; Moreb, J.S. Cardiotoxicity associated with carfilzomib: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Leuk Lymphoma 2018, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Grandin, E.W.; Ky, B.; Cornell, R.F.; Carver, J.; Lenihan, D.J. Patterns of cardiac toxicity associated with irreversible proteasome inhibition in the treatment of multiple myeloma. J Card Fail 2015, 21, 138-144. [CrossRef]

- Fradley, M.G.; Groarke, J.D.; Laubach, J.; Alsina, M.; Lenihan, D.J.; Cornell, R.F.; Maglio, M.; Shain, K.H.; Richardson, P.G.; Moslehi, J. Recurrent cardiotoxicity potentiated by the interaction of proteasome inhibitor and immunomodulatory therapy for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol 2018, 180, 271-275. [CrossRef]

- Waxman, A.J.; Clasen, S.; Hwang, W.T.; Garfall, A.; Vogl, D.T.; Carver, J.; O’Quinn, R.; Cohen, A.D.; Stadtmauer, E.A.; Ky, B.; et al. Carfilzomib-Associated Cardiovascular Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 2018, 4, e174519. [CrossRef]

- Cornell, R.F.; Ky, B.; Weiss, B.M.; Dahm, C.N.; Gupta, D.K.; Du, L.; Carver, J.R.; Cohen, A.D.; Engelhardt, B.G.; Garfall, A.L.; et al. Prospective Study of Cardiac Events During Proteasome Inhibitor Therapy for Relapsed Multiple Myeloma. J Clin Oncol 2019, 37, 1946-1955. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Z. The role and mechanism of epigenetics in anticancer drug-induced cardiotoxicity. Basic Res Cardiol 2025, 120, 11-24. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Paiva, B.; Anderson, K.C.; Durie, B.; Landgren, O.; Moreau, P.; Munshi, N.; Lonial, S.; Bladé, J.; Mateos, M.V.; et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol 2016, 17, e328-e346. [CrossRef]

- Aryee, M.J.; Jaffe, A.E.; Corrada-Bravo, H.; Ladd-Acosta, C.; Feinberg, A.P.; Hansen, K.D.; Irizarry, R.A. Minfi: A flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1363-1369. [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Zhang, X.; Huang, C.C.; Jafari, N.; Kibbe, W.A.; Hou, L.; Lin, S.M. Comparison of Beta-value and M-value methods for quantifying methylation levels by microarray analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11, 587. [CrossRef]

- Oytam, Y.; Sobhanmanesh, F.; Duesing, K.; Bowden, J.C.; Osmond-McLeod, M.; Ross, J. Risk-conscious correction of batch effects: Maximising information extraction from high-throughput genomic datasets. BMC Bioinformatics 2016, 17, 332. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, e47. [CrossRef]

- van Iterson, M.; van Zwet, E.W.; Heijmans, B.T.; Consortium, B. Controlling bias and inflation in epigenome- and transcriptome-wide association studies using the empirical null distribution. Genome Biol 2017, 18, 19. [CrossRef]

- Peters, T.J.; Buckley, M.J.; Statham, A.L.; Pidsley, R.; Samaras, K.; V Lord, R.; Clark, S.J.; Molloy, P.L. De novo identification of differentially methylated regions in the human genome. Epigenetics Chromatin 2015, 8, 6. [CrossRef]

- Balduzzi, S.; Rücker, G.; Schwarzer, G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: A practical tutorial. Evid Based Ment Health 2019, 22, 153-160. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M.L.; Boukens, B.J.; Mommersteeg, M.T.; Brons, J.F.; Wakker, V.; Moorman, A.F.; Christoffels, V.M. Transcription factor Tbx3 is required for the specification of the atrioventricular conduction system. Circ Res 2008, 102, 1340-1349. [CrossRef]

- Hoogaars, W.M.; Engel, A.; Brons, J.F.; Verkerk, A.O.; de Lange, F.J.; Wong, L.Y.; Bakker, M.L.; Clout, D.E.; Wakker, V.; Barnett, P.; et al. Tbx3 controls the sinoatrial node gene program and imposes pacemaker function on the atria. Genes Dev 2007, 21, 1098-1112. [CrossRef]

- Hille, S.; Dierck, F.; Kühl, C.; Sosna, J.; Adam-Klages, S.; Adam, D.; Lüllmann-Rauch, R.; Frey, N.; Kuhn, C. Dyrk1a regulates the cardiomyocyte cell cycle via D-cyclin-dependent Rb/E2f-signalling. Cardiovasc Res 2016, 110, 381-394. [CrossRef]

- DNAJC18 DnaJ heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member C18 [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/202052.

- Malakhov, M.P.; Malakhova, O.A.; Kim, K.I.; Ritchie, K.J.; Zhang, D.E. UBP43 (USP18) specifically removes ISG15 from conjugated proteins. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 9976-9981. [CrossRef]

- Hipp, M.S.; Raasi, S.; Groettrup, M.; Schmidtke, G. NEDD8 ultimate buster-1L interacts with the ubiquitin-like protein FAT10 and accelerates its degradation. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 16503-16510. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.H.; Song, A.X.; Hu, H.Y. NEDD8 ultimate buster-1 long (NUB1L) protein promotes transfer of NEDD8 to proteasome for degradation through the P97UFD1/NPL4 complex. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 31339-31349. [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Jian, C.; Xu, J.; Huang, A.Y.; Xi, J.; Hu, K.; Wei, L.; Cheng, H.; Wang, X. Identification of EFHD1 as a novel Ca(2+) sensor for mitoflash activation. Cell Calcium 2016, 59, 262-270. [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, T.J.; Nadalutti, C.A.; Motori, E.; Sommerville, E.W.; Gorman, G.S.; Basu, S.; Hoberg, E.; Turnbull, D.M.; Chinnery, P.F.; Larsson, N.G.; et al. Topoisomerase 3α Is Required for Decatenation and Segregation of Human mtDNA. Mol Cell 2018, 69, 9-23.e26. [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Zhang, L.; Sun, G. GLN2 as a key biomarker and therapeutic target: Evidence from a comprehensive pan-cancer study using molecular, functional, and bioinformatic analyses. Discov Oncol 2024, 15, 681. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.W.; Yang, J.Y.; Ma, X.; Chen, Z.P.; Hu, Y.R.; Zhao, J.Y.; Li, S.F.; Qiu, Y.R.; Lu, J.B.; Wang, Y.C.; et al. A lincRNA-DYNLRB2-2/GPR119/GLP-1R/ABCA1-dependent signal transduction pathway is essential for the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. J Lipid Res 2014, 55, 681-697. [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Han, W. Identification of necroptosis-related diagnostic biomarkers in coronary heart disease. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30269. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Cong, Y.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; Lin, P. Differential expression profiles of long non-coding RNAs as potential biomarkers for the early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 88613-88621. [CrossRef]

- Consortium, G. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 2020, 369, 1318-1330. [CrossRef]

- Statello, L.; Guo, C.J.; Chen, L.L.; Huarte, M. Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021, 22, 96-118. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Yang, F.; Li, M.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, G.; Li, Z.; Zheng, X.; Zou, D.; Zong, W.; et al. EWAS Open Platform: Integrated data, knowledge and toolkit for epigenome-wide association study. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D1004-D1009. [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.U.; Carter, K.L.; Thomas, K.R.; Burr, R.M.; Bakker, M.L.; Coetzee, W.A.; Tristani-Firouzi, M.; Bamshad, M.J.; Christoffels, V.M.; Moon, A.M. Lethal arrhythmias in Tbx3-deficient mice reveal extreme dosage sensitivity of cardiac conduction system function and homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, E154-163. [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, A.; Piegari, E.; Cappetta, D.; Marino, L.; Filippelli, A.; Berrino, L.; Ferreira-Martins, J.; Zheng, H.; Hosoda, T.; Rota, M.; et al. Anthracycline cardiomyopathy is mediated by depletion of the cardiac stem cell pool and is rescued by restoration of progenitor cell function. Circulation 2010, 121, 276-292. [CrossRef]

- Ebadi, N.; Arefizadeh, R.; Nasrollahzadeh Sabet, M.; Goodarzi, N. Identification of Key Genes and Biological Pathways Related to Myocardial Infarction through Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis. Iran J Med Sci 2023, 48, 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, C.; Frank, D.; Will, R.; Jaschinski, C.; Frauen, R.; Katus, H.A.; Frey, N. DYRK1A is a novel negative regulator of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 17320-17327. [CrossRef]

- Schrader, M.; Fahimi, H.D. Peroxisomes and oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006, 1763, 1755-1766. [CrossRef]

- Gallo, S.; Vitacolonna, A.; Bonzano, A.; Comoglio, P.; Crepaldi, T. ERK: A Key Player in the Pathophysiology of Cardiac Hypertrophy. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Kastritis, E.; Laina, A.; Georgiopoulos, G.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Papanagnou, E.D.; Eleutherakis-Papaiakovou, E.; Fotiou, D.; Kanellias, N.; Dialoupi, I.; Makris, N.; et al. Carfilzomib-induced endothelial dysfunction, recovery of proteasome activity, and prediction of cardiovascular complications: A prospective study. Leukemia 2021, 35, 1418-1427. [CrossRef]

- Georgiopoulos, G.; Makris, N.; Laina, A.; Theodorakakou, F.; Briasoulis, A.; Trougakos, I.P.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Kastritis, E.; Stamatelopoulos, K. Cardiovascular Toxicity of Proteasome Inhibitors: Underlying Mechanisms and Management Strategies:. JACC CardioOncol 2023, 5, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.; Kiltschewskij, D.J.; Leong, A.J.W.; Haw, T.J.; Croft, A.J.; Balachandran, L.; Chen, D.; Bond, D.R.; Lee, H.J.; Cairns, M.J.; et al. Identifying common pathways for doxorubicin and carfilzomib-induced cardiotoxicities: Transcriptomic and epigenetic profiling. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 4395. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.L.; Henry, A.; Cannie, D.; Lee, M.; Miller, D.; McGurk, K.A.; Bond, I.; Xu, X.; Issa, H.; Francis, C.; et al. Genome-wide association analysis provides insights into the molecular etiology of dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet 2024, 56, 2646-2658. [CrossRef]

- Jurgens, S.J.; Rämö, J.T.; Kramarenko, D.R.; Wijdeveld, L.F.J.M.; Haas, J.; Chaffin, M.D.; Garnier, S.; Gaziano, L.; Weng, L.C.; Lipov, A.; et al. Genome-wide association study reveals mechanisms underlying dilated cardiomyopathy and myocardial resilience. Nat Genet 2024, 56, 2636-2645. [CrossRef]

- Spielmann, N.; Miller, G.; Oprea, T.I.; Hsu, C.W.; Fobo, G.; Frishman, G.; Montrone, C.; Haseli Mashhadi, H.; Mason, J.; Munoz Fuentes, V.; et al. Extensive identification of genes involved in congenital and structural heart disorders and cardiomyopathy. Nat Cardiovasc Res 2022, 1, 157-173. [CrossRef]

- Potu, H.; Sgorbissa, A.; Brancolini, C. Identification of USP18 as an important regulator of the susceptibility to IFN-alpha and drug-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res 2010, 70, 655-665. [CrossRef]

- Stessman, H.A.; Baughn, L.B.; Sarver, A.; Xia, T.; Deshpande, R.; Mansoor, A.; Walsh, S.A.; Sunderland, J.J.; Dolloff, N.G.; Linden, M.A.; et al. Profiling bortezomib resistance identifies secondary therapies in a mouse myeloma model. Mol Cancer Ther 2013, 12, 1140-1150. [CrossRef]

- Ying, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, T.; Yuan, A.; Xu, L.; Gao, L.; Ding, S.; Ding, H.; Pu, J.; He, B. Novel Protective Role for Ubiquitin-Specific Protease 18 in Pathological Cardiac Remodeling. Hypertension 2016, 68, 1160-1170. [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, D.R.; Lee, S.H.; Yin, X.; Balynas, A.M.; Rekate, E.C.; Kraiss, J.N.; Lang, M.J.; Walsh, M.A.; Streiff, M.E.; Corbin, A.C.; et al. EFHD1 ablation inhibits cardiac mitoflash activation and protects cardiomyocytes from ischemia. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2022, 167, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.E.; Purcaro, M.J.; Pratt, H.E.; Epstein, C.B.; Shoresh, N.; Adrian, J.; Kawli, T.; Davis, C.A.; Dobin, A.; Kaul, R.; et al. Expanded encyclopaedias of DNA elements in the human and mouse genomes. Nature 2020, 583, 699-710. [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Lopez, M.; Besse, A.; Zuppinger, C.; Perez-Shibayama, C.; Gil-Cruz, C.; Florea, B.I.; De Martin, A.; Lütge, M.; Beckerova, D.; Klimovic, S.; et al. Carfilzomib-specific proteasome β5/β2 inhibition drives cardiotoxicity via remodeling of protein homeostasis and the renin-angiotensin-system. iScience 2025, 28, 113228. [CrossRef]

| Baseline patients’ characteristics (n = 79) | ||||||

| CFZ (n=49) | BTZ (n=30) | |||||

| CVAE (n=23) |

No-CVAE (n=26) |

p | CVAE (n=5) |

No-CVAE (n=25) |

p | |

| Continuous | ||||||

| Age (years) | 66.40 ± 9.30 | 63.85 ± 9.93 | 0.36 | 71.20 ± 13.60 | 61.88 ± 9.91 | 0.08 |

| Categorical | ||||||

| Sex | 0.48 | >0.99 | ||||

| Female | 5 (21.7%) | 7 (26.9%) | 2 (40.0%) | 12 (48.0%) | ||

| Male | 18 (78.3%) | 19 (73.1%) | 3 (60.0%) | 13 (52.0%) | ||

| Race | 0.67 | 0.63 | ||||

| White | 21 (91.3%) | 22 (84.6%) | 5 (100.0%) | 19 (76.0%) | ||

| African American | 2 (8.7%) | 4 (15.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (20.0%) | ||

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.0%) | ||

| Smoking status | 0.07 | >0.99 | ||||

| Yes | 14 (60.9%) | 8 (30.8%) | 1 (20.0%) | 4 (16.0%) | ||

| No | 9 (39.1%) | 18 (69.2%) | 4 (80.0%) | 21 (84.0%) | ||

| History of HTN | 0.35 | 0.13 | ||||

| Yes | 11 (47.8%) | 8 (30.8%) | 4 (80.0%) | 8 (32.0%) | ||

| No | 12 (52.2%) | 18 (69.2%) | 1 (20.0%) | 17 (68.0%) | ||

| Brain natriuretic peptide* | 0.006 | 0.03 | ||||

| High | 12 (52.2%) | 3 (11.5%) | 4 (80.0%) | 8 (32.0%) | ||

| Normal | 11 (47.8%) | 23 (88.4%) | 1 (20.0%) | 17 (68.0%) | ||

| No | CpG ID | CHR | Position | Gene Name | CpG relation | Feature | CFZ analysis | BTZ analysis | Meta-analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| logFC | p | FDR | logFC | p | FDR | logFC | p | FDR | |||||||

| 1 | cg15144237 | 2 | 16400125 | ENSG00000224400 | Opensea | Intron | 0.39 | 9.45 x 10 −10 | 0.001 | -0.10 | 0.58 | 0.97 | 0.18 | 0.47 | 0.98 |

| 2 | cg00927646 | 12 | 114656631 | TBX3 | Opensea | Intergenic | 0.51 | 9.78 x 10−8 | 0.028 | -0.36 | 0.047 | 0.93 | 0.09 | 0.84 | 0.99 |

| 3 | cg10965131 | 7 | 151381909 | WDR86 | Island | Exon | -0.53 | 1.00 x 10−7 | 0.028 | -0.53 | 0.93 | >0.99 | -0.32 | 0.20 | 0.98 |

| 4 | cg16099849 | 11 | 20609207 | SLC6A5 | Opensea | Intron | 0.47 | 1.79 x10−7 | 0.038 | 0.03 | 0.89 | 0.99 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.98 |

| 5 | cg10842296 | 16 | 80540122 | DYNLRB2 | Shore | TSS1500 | 0.54 | 3.18 x10−7 | 0.054 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.96 | 0.21 | 0.58 | 0.98 |

| 6 | cg09456439 | 21 | 37565327 | DYRK1A, KCNJ6 | Shore | Intergenic | -0.34 | 1.52 x10−6 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.86 | 0.99 | -0.20 | 0.28 | 0.98 |

| 7 | cg09666417 | 5 | 139439593 | DNAJC18 | Opensea | TSS200 | 0.05 | 0.66 | >0.99 | -0.96 | 3.41 x 10−7 | 0.14 | -0.44 | 0.38 | 0.98 |

| 8 | cg12987761 | 22 | 18148690 | USP18 | Shore | Intron | 0.003 | 0.98 | >0.99 | -0.84 | 5.00 x 10−7 | 0.14 | -0.41 | 0.33 | 0.98 |

| 9 | cg05020252 | 2 | 232634573 | EFHD1 | Island | Intron | -0.04 | 0.69 | >0.99 | -0.91 | 7.40 x10−7 | 0.14 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.98 |

| 10 | cg17933807 | 1 | 37596074 | GNL2 | Island | TSS200 | -0.49 | 7.38 x10−5 | 0.314 | -0.68 | 0.002 | 0.93 | 0.11 | 5.79 x10−7 | 0.32 |

| 11 | cg06683313 | 17 | 18316066 | SMCR8, TOP3A | Shore | Exon, TSS200 | -0.24 | 4.43 x10−5 | 0.28 | -0.30 | 0.01 | 0.93 | 0.05 | 1.70 x10−6 | 0.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).