Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Study Design

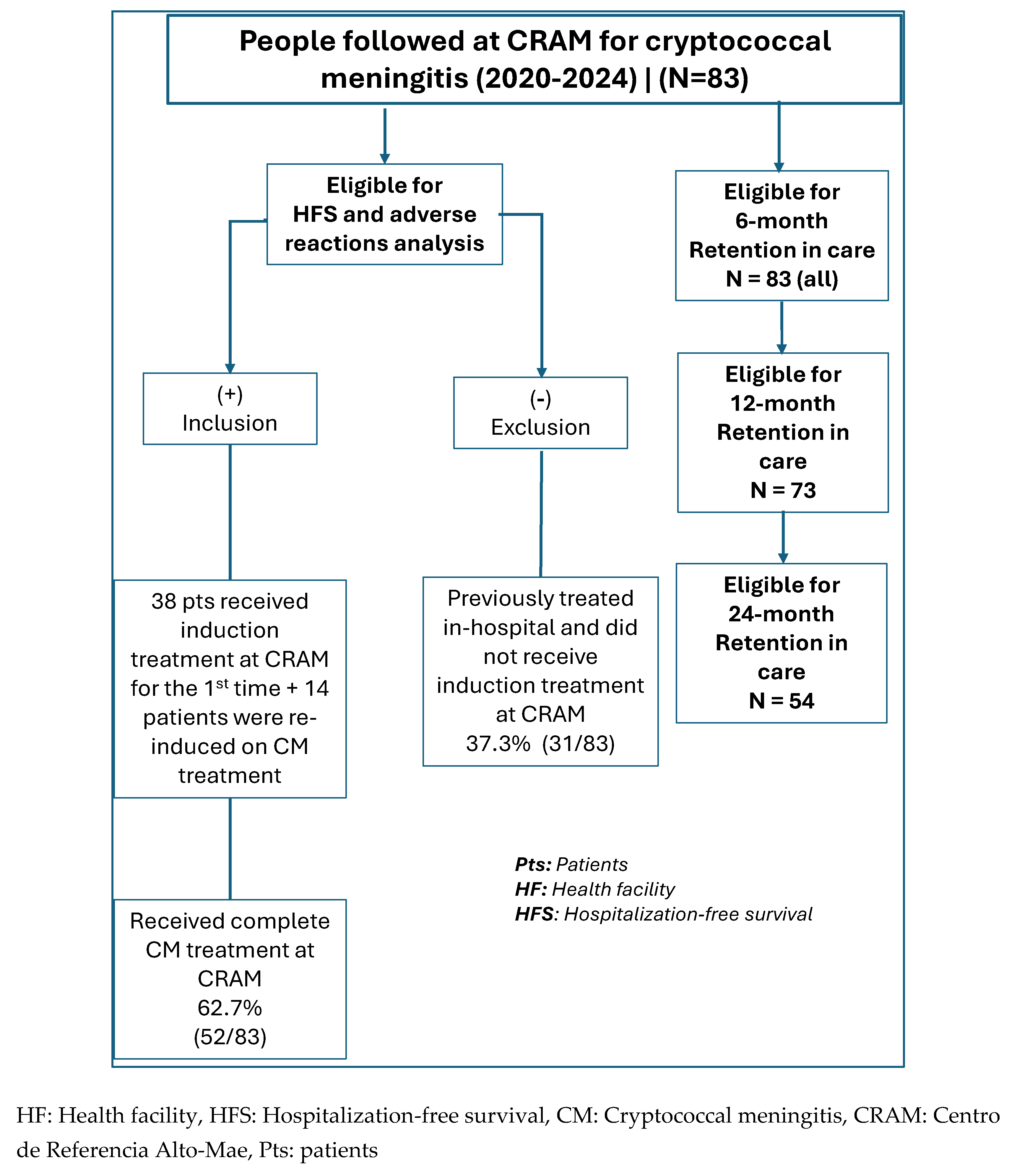

2.2.1. Eligible Participants

2.2.2. Sampling and Sample Size

2.2.3. Program Data Collection

2.3. Outcome Data and Statistical Analysis of Data

2.3.1. Primary Outcome

- Hospitalization referrals were guided by two main criteria: First, the presence of clinical danger signs, including an altered level of consciousness (observed or reported), seizures, or other critical symptoms such as respiratory distress. Second, anticipated logistical barriers that would prevent regular clinic attendance, for instance, living a significant distance from the health facility without access to reliable transportation.

- HFS was defined as the proportion of patients who survived for at least 10 weeks following cryptococcal meningitis diagnosis without requiring inpatient admission at any point during this follow-up period.

2.3.2. Secondary Outcomes

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of Patients with CM Followed Up at CRAM

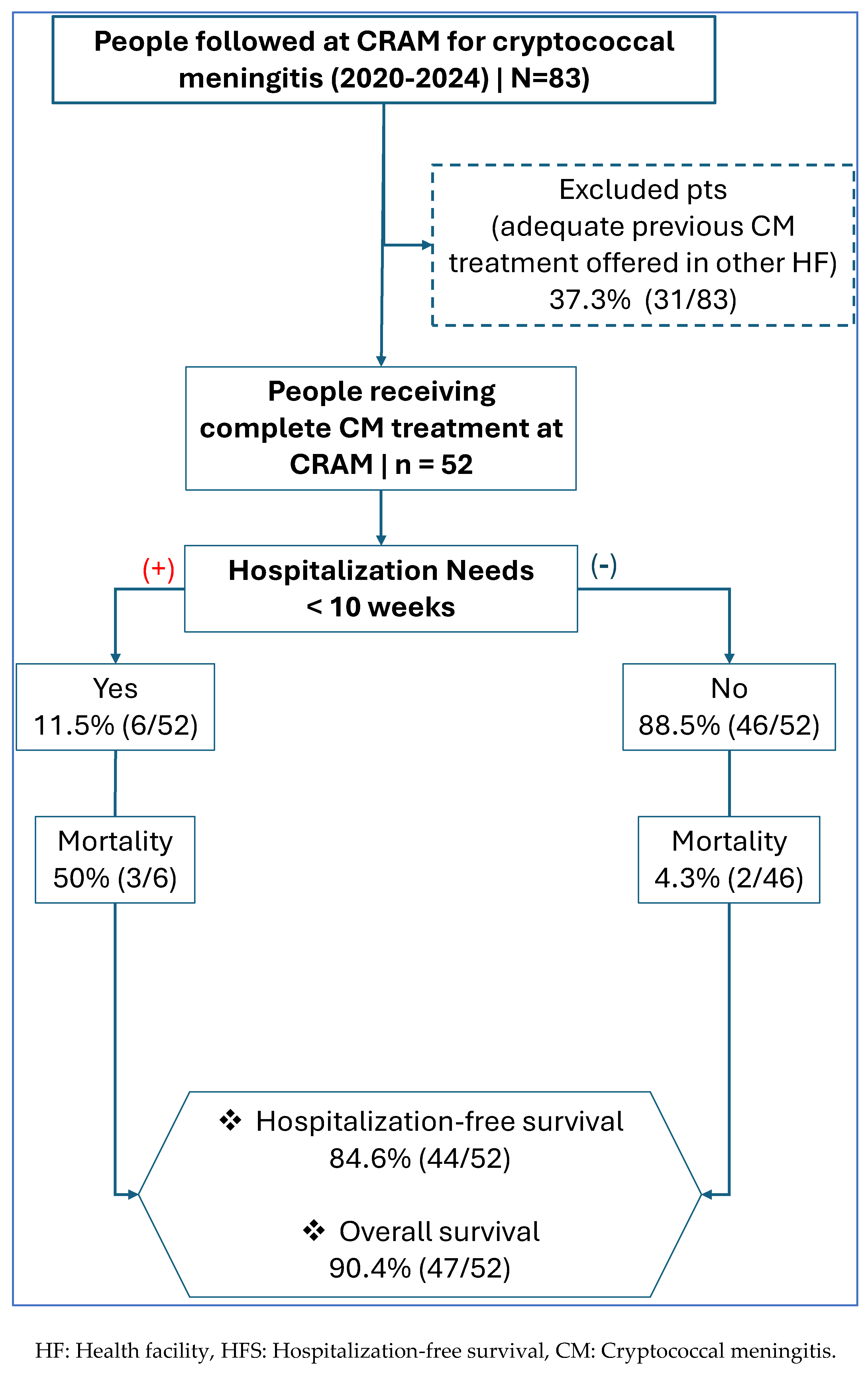

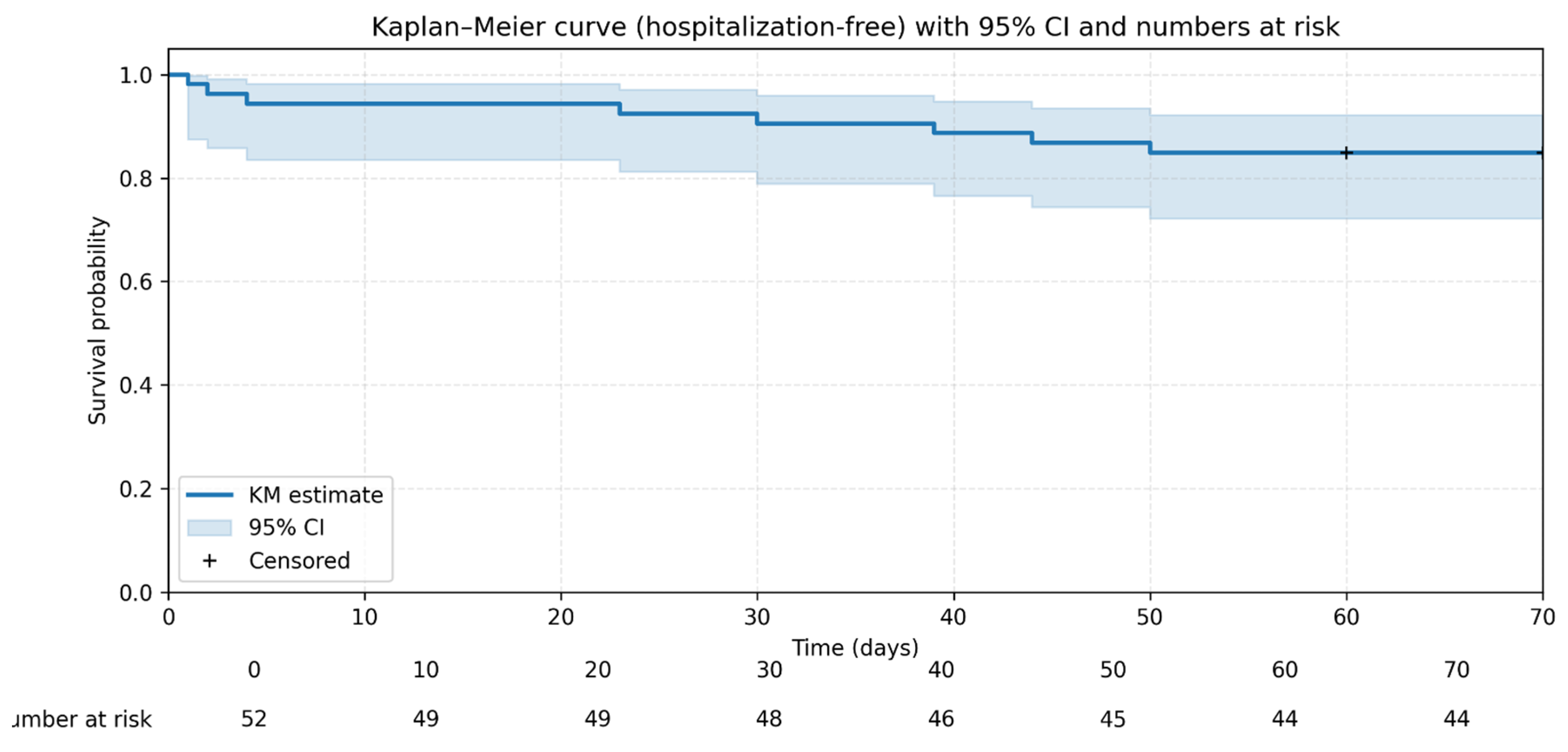

3.2. HFS Within the First 10 Weeks of Treatment Among Patients with CM

3.3. ADR of Treatment (Frequency and Severity) Among Patients with CM

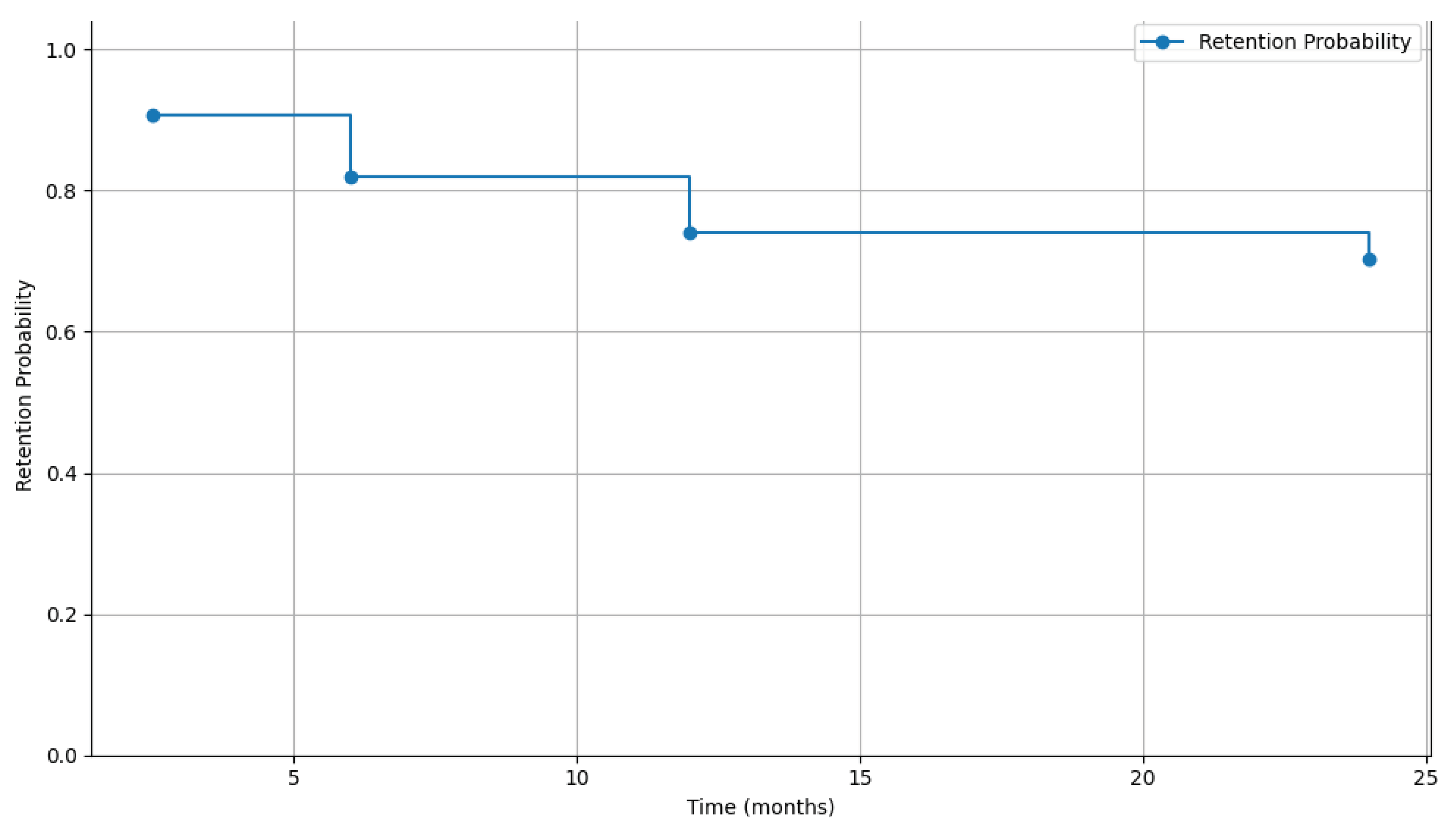

3.4. Retention in Care (RIC) Among Patients with CM (at 6, 12, and 24 Months)

4. Discussion

4.1. High HFS and Overall Survival

4.2. Manageable and Reversible ADRs

4.3. High RIC at 6 Months

4.4. Other Findings: High Burden of Concurrent TB

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aOR: | Adjusted odds ratios |

| ADR: | Adverse drug reactions |

| AHD: | Advanced HIV Disease |

| ART: | Antiretroviral therapy |

| CI: | Confidence intervals |

| CM: | Cryptococcal meningitis |

| CrAg: | Cryptococcal Antigen |

| CSF: | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| CRAM: | Centro de Referência de Alto-Maé |

| IQR: | Interquartile range |

| HFS: | Hospitalization-free survival |

| I-TECH | International training and education center for health |

| L-AmB | Liposomal Amphotericin B |

| OIs: | Opportunistic infections |

| PHC: | Primary healthcare centre |

| PLWH: | People living with HIV |

| MoH: | Ministry of Health |

| MSF: | Médecins Sans Frontières |

| SD: | Standard deviation |

| SSA: | sub-Saharan Africa |

| TB: | Tuberculosis |

References

- Lin, F. Tuberculous meningitis diagnosis and treatment: classic approaches and high-throughput pathways. Front. Immunol. 2025, 15, 1543009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, J.; Misra, U.K.; Ranjan, P. Predictors of long-term neurological sequelae of tuberculous meningitis: a multivariate analysis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2007, 14, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyelo, C.M.; Solomons, R.S.; Walzl, G.; Chegou, N.N. Tuberculous Meningitis: Pathogenesis, Immune Responses, Diagnostic Challenges, and the Potential of Biomarker-Based Approaches. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estela Isabel, B.; Pando Rogelio, H. Pathogenesis and Immune Response in Tuberculous Meningitis. 2014, 21, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dastur, D.K.; Manghani, D.K.; Udani, P. PATHOLOGY AND PATHOGENETIC MECHANISMS IN NEUROTUBERCULOSIS. Radiol. Clin. North Am. 1995, 33, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thwaites, G.; Chau, T.T.H.; Mai, N.T.H.; Drobniewski, F.; McAdam, K.; Farrar, J. Neurological aspects of tropical disease: Tuberculous meningitis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2000, 68, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.-F.; Leng, E.-L.; Liu, S.-M.; Zhou, Y.-L.; Luo, C.-Q.; Xiang, Z.-B.; Cai, W.; Rao, W.; Hu, F.; Zhang, P.; et al. Recent advances in microbiological and molecular biological detection techniques of tuberculous meningitis. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1202752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO, “Global Tuberculosis Report 2024,” World Health Organization, Geneva, 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024.

- Kwan, C.K.; Ernst, J.D. HIV and Tuberculosis: a Deadly Human Syndemic. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 24, 351–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Gottberg, A.; Meintjes, G. Meningitis: a frequently fatal diagnosis in Africa. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 676–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenforde, M.W.; Gertz, A.M.; Lawrence, D.S.; Wills, N.K.; Guthrie, B.L.; Farquhar, C.; Jarvis, J.N. Mortality from HIV-associated meningitis in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020, 23, e25416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MISAU PNCT (Programa Nacional de Controlo da Tuberculose), Relatorio Anual de Tuberculose 2024, Moçambique; Ministério da Saúde de Moçambique.

- MISAU PNCT (Programa Nacional de Controlo da Tuberculose), “Relatorio Anual de Tuberculose 2023, Moçambique,” MISAU, Maputo, 2023. Accessed: Jun. 27, 2025. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/860655980/Relatorio-Anual-Do-PNCT-2023-29042024.

- MISAU PNCT (Programa Nacional de Controlo da Tuberculose), Plano Estratégico Nacional para acabar com a Tuberculose em Moçambique 2023 - 2030; Ministério da Saúde: Maputo, 2023.

- MISAU PNCT (Programa Nacional de Combate a Tuberculose, “Manuais de Directrizes e Guiões de TB, Moçambique,” Ministério da Saúde de Moçambique. 24 Mar 2022. Available online: https://www.misau.gov.mz/index.php/manuais-directrizes-e-guioes-tb.

- MISAU PNCT (Programa Nacional de Controlo da Tuberculose), Manual de Manejo Clínico e Programático da Tuberculose Multirresistente; Moçambique, Sep 2019.

- Nacarapa, E.; Muchiri, E.; Moon, T.D.; Charalambous, S.; E Verdu, M.; Ramos, J.M.; Valverde, E.J. Effect of Xpert MTB/RIF testing introduction and favorable outcome predictors for tuberculosis treatment among HIV infected adults in rural southern Mozambique. A retrospective cohort study. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0229995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, X.Y.; Loh, F.K.; Friedland, J.S.; Ong, C.W.M. Neutrophil-Mediated Immunopathology and Matrix Metalloproteinases in Central Nervous System – Tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 788976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacarapa, E.; Verdu, M.E.; Nacarapa, J.; Macuacua, A.; Chongo, B.; Osorio, D.; Munyangaju, I.; Mugabe, D.; Paredes, R.; Chamarro, A.; et al. Predictors of attrition among adults in a rural HIV clinic in southern Mozambique: 18-year retrospective study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Su, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhang, T. Incomplete immune reconstitution in HIV/AIDS patients on antiretroviral therapy: Challenges of immunological non-responders. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020, 107, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHM Developing a sustainable HIV, “Immunological failure: persistent CD4+ T cell deficiency”. 20 Apr 2022. Available online: https://hivmanagement.ashm.org.au/long-term-management-of-antiretroviral-therapy/immunological-failure-persistent-cd4-t-cell-deficiency/.

- WHO. HIV PREVENTION, INFANT DIAGNOSIS. In ANTIRETROVIRAL INITIATION AND MONITORING GUIDELINES; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- MISAU PNC ITS-HIV/SIDA, “Guião de manejo do paciente com doença avançada por HIV - 2022,” Ministério da Saúde de Moçambique. Accessed: Oct. 15, 2023. Available online: https://www.misau.gov.mz/index.php/guioes-de-prevencao-e-de-cuidados-e-tratamento?download=1352:guiao-de-manejo-do-paciente-com-doenca-avancada-por-hiv-2022.

- MISAU PNC ITS-HIV/SIDA, “Normas Clinicas Actualizadas para o seguimento do paciente HIV Positivo,” Comite TARV Mozambique. 14 Nov 2023. Available online: https://comitetarvmisau.co.mz/docs/orientacoes_nacionais/Circular_Normas_Cl%C3%ADnicas_Actualizadas_29_11_19.pdf.

- MISAU PNC ITS-HIV/SIDA, “Programa Nacional de Controle de ITS-HIV/SIDA - Directrizes nacionais,” Ministério da Saúde de Moçambique, Accessed: Mar. 26, 2022. Available online: https://www.misau.gov.mz/index.php/hiv-sida-directrizes-nacionais.

- Chun, H.M.; Milligan, K.; Boyd, M.A.; Abutu, A.; Bachanas, P.; Dirlikov, E. Reaching HIV epidemic control in Nigeria using a lower HIV viral load suppression cut-off. AIDS 2023, 37, 2081–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavinton, B.R.; Rodger, A.J. Undetectable viral load and HIV transmission dynamics on an individual and population level: where next in the global HIV response? Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 33, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HIV.gov. “Viral Suppression and an Undetectable Viral Load,” HIV.gov. 13 Feb 2025. Available online: https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/staying-in-hiv-care/hiv-treatment/viral-suppression.

- Handoko, R.; Colby, D.J.; Kroon, E.; Sacdalan, C.; de Souza, M.; Pinyakorn, S.; Prueksakaew, P.; Munkong, C.; Ubolyam, S.; Akapirat, S.; et al. Determinants of suboptimal CD4+ T cell recovery after antiretroviral therapy initiation in a prospective cohort of acute HIV-1 infection. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, M.M.; Haddad, M.; Sheybani, F.; Shirazinia, M.; Dadgarmoghaddam, M. Mortality predictors and diagnostic challenges in adult tuberculous meningitis: a retrospective cohort of 100 patients. Trop. Med. Heal. 2025, 53, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasar, K.K.; Pehlivanoglu, F.; Sengoz, G. Predictors of mortality in tuberculous meningitis: a multivariate analysis of 160 cases. 2010, 14, 1330–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wei, J.; Zhang, M.; Su, B.; Ren, M.; Cai, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T. Prevalence, incidence, and case fatality of tuberculous meningitis in adults living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Heal. 2024, 24, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loghin, I.I.; Vâță, A.; Miftode, E.G.; Cobaschi, M.; Rusu, Ș.A.; Silvaș, G.; Frăsinariu, O.E.; Dorobăț, C.M. Characteristics of Tuberculous Meningitis in HIV-Positive Patients from Northeast Romania. Clin. Pr. 2023, 13, 1488–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosgei, R.J.; Callens, S.; Gichangi, P.; Temmerman, M.; Kihara, A.-B.; David, G.; Omesa, E.N.; Masini, E.; Carter, E.J. Gender difference in mortality among pulmonary tuberculosis HIV co-infected adults aged 15-49 years in Kenya. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0243977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alebel, A.; Demant, D.; Petrucka, P.; Sibbritt, D. Effects of undernutrition on mortality and morbidity among adults living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, H.W.; Ko, Y.; Oh, J.Y.; Jeong, Y.-J.; Lee, E.H.; Yang, B.; Lee, K.M.; Ahn, J.H.; et al. Effects of underweight and overweight on mortality in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Front. Public Heal. 2023, 11, 1236099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Liu, K.-W.; Tong, J.; Gao, M.-Q. Prevalence and prognostic significance of malnutrition risk in patients with tuberculous meningitis. Front. Public Health 12, 1391821. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Ma, Y.; Ji, X.; Jiang, H.; Liu, F.; Chu, N.; Li, Q. A study of risk factors for tuberculous meningitis among patients with tuberculosis in China: An analysis of data between 2012 and 2019. Front. Public Heal. 10, 1040071. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojo, T.; Ruan, C.; Hameed, T.; Malburg, C.; Thunga, S.; Smith, J.; Vieira, D.; Snyder, A.; Tampubolon, S.J.; Gyamfi, J.; et al. HIV, Tuberculosis, and Food Insecurity in Africa—A Syndemics-Based Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wambua, J.; Ali, A.; Ukwizabigira, J.B.; Kuodi, P. Prevalence and risk factors of under-five mortality due to severe acute malnutrition in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2025, 14, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Gu, Z.; Chen, X.; Yu, X.; Meng, X. Analysis of risk factors for long-term mortality in patients with stage II and III tuberculous meningitis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, J.C.; Sawaya, A.L.; Wibaek, R.; Mwangome, M.; Poullas, M.S.; Yajnik, C.S.; Demaio, A. The double burden of malnutrition: aetiological pathways and consequences for health. Lancet 2019, 395, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azomahou, T.T.; Diene, B.; Gosselin-Pali, A. Transition and persistence in the double burden of malnutrition and overweight or obesity: Evidence from South Africa. Food Policy 2022, 113, 102303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, P.J.; Osman, M.; Cresswell, F.V.; Stadelman, A.M.; Lan, N.H.; Thuong, N.T.T.; Muzyamba, M.; Glaser, L.; Dlamini, S.S.; Seddon, J.A. The global burden of tuberculous meningitis in adults: A modelling study. PLOS Glob. Public Heal. 2021, 1, e0000069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao, L.T.P.; Heemskerk, A.D.; Geskus, R.B.; Mai, N.T.H.; Ha, D.T.M.; Chau, T.T.H.; Phu, N.H.; Chau, N.V.V.; Caws, M.; Lan, N.H.; et al. Prognostic Models for 9-Month Mortality in Tuberculous Meningitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 66, 523–532. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinnard, C.; Macgregor, R.R. Tuberculous meningitis in HIV-infected individuals. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2009, 6, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacarapa, E.; Munyangaju, I. Isabelle; Osório, D.; Ramos-Rincon, J.-M. “Mortality and Predictors of Poor Outcomes among Persons with HIV and Tuberculous Meningitis, in Mozambique,” Jul. 02, 2025, Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.K.; Tobin, D.M.; Tucker, E.W.; Venketaraman, V.; Ordonez, A.A.; Jayashankar, L.; Siddiqi, O.K.; Hammoud, D.A.; Prasadarao, N.V.; et al.; on behalf of the NIH Tuberculous Meningitis Writing Group Tuberculous meningitis: a roadmap for advancing basic and translational research. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Seddon, J.; Tugume, L.; Solomons, R.; Prasad, K.; Bahr, N.C. Tuberculous Meningitis International Research Consortium The current global situation for tuberculous meningitis: epidemiology, diagnostics, treatment and outcomes. Wellcome Open Res. 2019, 4, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slane, V. H.; Unakal, C. G. Tuberculous Meningitis; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, J.H. Tuberculous meningitis. Neurol. Clin. Pr. 2014, 4, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieque, A.L.; Palomo, C.T.; Moreira, D.d.C.; Meneguello, J.E.; Murase, L.S.; Silva, L.L.; Baldin, V.P.; Caleffi-Ferracioli, K.R.; Siqueira, V.L.D.; Cardoso, R.F.; et al. Systematic review of tuberculous meningitis in high-risk populations: mortality and diagnostic disparities. Futur. Microbiol. 20, 559–571. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Lin, W.; Zhang, S.; Chu, M.; Wei, L. Clinical indicators associated with tuberculous meningitis using multiple correspondence analysis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2025, 113, 116932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacarapa, E.; Munyangaju, I.; Osório, D.; Zindoga, P.; Mutaquiha, C.; Jose, B.; Macuacua, A.; Chongo, B.; De-Almeida, M.; Verdu, M.-E.; et al. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis mortality according to clinical and point of care ultrasound features in Mozambique. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saukkonen, J.J.; Duarte, R.; Munsiff, S.S.; Winston, C.A.; Mammen, M.J.; Abubakar, I.; Acuña-Villaorduña, C.; Barry, P.M.; Bastos, M.L.; Carr, W.; et al. Updates on the Treatment of Drug-Susceptible and Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis: An Official ATS/CDC/ERS/IDSA Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 211, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacarapa, E.; Jose, B.; Munyangaju, I.; Osório, D.; Ramos-Rincon, J.-M. “Incidence and Predictors of Mortality Among Persons With Drug Resistant Tuberculosis, and HIV, Mozambique (2015-2020),” Oct. 17, 2024, PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Flores, A.; Fernandez-Chinguel, J.E.; Pacheco-Barrios, N.; Soriano-Moreno, D.R.; Pacheco-Barrios, K. Global morbidity and mortality of central nervous system tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 3482–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, G.E.; Chan, E.D. Tuberculous Meningitis: Diagnosis and Treatment Overview. Tuberc. Res. Treat. 2011, 2011, 798764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, J.M.K. Management of Intracranial Pressure in Tuberculous Meningitis. Neurocritical Care 2005, 2, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdella, A.; Deginet, E.; Weldegebreal, F.; Ketema, I.; Eshetu, B.; Desalew, A. Tuberculous Meningitis in Children: Treatment Outcomes at Discharge and Its Associated Factors in Eastern Ethiopia: A Five Years Retrospective Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 2743–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, B.; Fei, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Sheng, M.; Xu, J.; Zhang, W.; Ren, W. Prognostic factors of adult tuberculous meningitis in intensive care unit: a single-center retrospective study in East China. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seid, G.; Alemu, A.; Dagne, B.; Gamtesa, D.F. Microbiological diagnosis and mortality of tuberculosis meningitis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0279203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, N.; K, D. Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, and Management Strategies of Tuberculous Meningitis. Arch. Intern. Med. Res. 2025, 8, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Tobin, E. H.; Munakomi, S. CNS Tuberculosis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.; Kamran, A.; Ahsan, D.; Amjad, A.; Moatter, S.; Noor, A.; Sohaib, A.; Shaukat, M.; Masood, W.; Hasanain, M.; et al. Advances in management and treatment of tubercular meningitis – a narrative review. Ann. Med. Surg. 2025, 87, 3673–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madadi, A.K.; Sohn, M.-J. Comprehensive Therapeutic Approaches to Tuberculous Meningitis: Pharmacokinetics, Combined Dosing, and Advanced Intrathecal Therapies. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Vioque, E.; Ello, F.; Andriamamonjisoa, H.; Machault, V.; González-Martín, J.; Calvo-Cortés, M.C.; Eholié, S.; Tchabert, G.A.; Ouassa, T.; Raberahona, M.; et al. Capacity Building in Sub-Saharan Africa as Part of the INTENSE-TBM Project During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2022, 11, 1327–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, E.E.; Avaliani, T.; Gujabidze, M.; Bakuradze, T.; Kipiani, M.; Sabanadze, S.; Smith, A.G.C.; Avaliani, Z.; Collins, J.M.; Kempker, R.R. Long term outcomes of patients with tuberculous meningitis: The impact of drug resistance. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0270201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahinkorah, B.O.; Amadu, I.; Seidu, A.-A.; Okyere, J.; Duku, E.; Hagan, J.E.; Budu, E.; Archer, A.G.; Yaya, S. Prevalence and Factors Associated with the Triple Burden of Malnutrition among Mother-Child Pairs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitre, T.; Bonnet, M.; Calmy, A.; Raberahona, M.; Rakotoarivelo, R.A.; Rakotosamimanana, N.; Ambrosioni, J.; Miró, J.M.; Debeaudrap, P.; Muzoora, C.; et al. Intensified tuberculosis treatment to reduce the mortality of HIV-infected and uninfected patients with tuberculosis meningitis (INTENSE-TBM): study protocol for a phase III randomized controlled trial. Trials 2022, 23, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANRS Emerging Infectious Diseases, “INTENSE-TBM – Partnering for better care in TB meningitis | Intensified tuberculosis treatment with or without aspirin to reduce the mortality of tuberculous meningitis in HIV infected and uninfected patients: a phase III randomized controlled trial (INTENSE-TBM) | NCT04145258,” European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP). 19 Aug 2025. Available online: https://intense-tbm.org/clinical-trial/.

| Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics of 83 people treated with antifungal treatment for cryptococcal meningitis in CRAM, Mozambique 2020–2024 | |||

| Column, N(%) | 95% CI | ||

| N=83 | |||

| Gender | Women | 30 (36.1) | (26.4 - 46.8) |

| Men | 53 (63.9) | (53.2 - 73.6) | |

| Age | Median, Interquartile Range (IQR) | 37 | 27 – 42 |

| Age_band | ≤24 yrs old | 11 (13.3) | (5.8 – 22.5) |

| 25-34 yrs old | 21 (25.3) | (16.5 – 36.0) | |

| 35-44 yrs old | 36 (43.4) | (32.5 – 54.8) | |

| 45-54 yrs old | 11 (13.3) | (6.8 – 22.5) | |

| ≥55 yrs old | 4 (4.8) | (1.3 – 11.9) | |

| Year of diagnosis | 2020 | 7 (8.4) | (3.9 - 15.8) |

| 2021 | 22 (26.5) | (17.9 - 36.7) | |

| 2022 | 20 (24.1) | (15.9 - 34.1) | |

| 2023 | 14 (16.9) | (10.0 - 26.0) | |

| 2024 | 20 (24.1) | (15.9 - 34.1) | |

| Body Mass Index Band | BMI > 18.5 | 39 (50.0) | (39.1 - 60.9) |

| BMI < 18.4 | 39 (50.0) | (39.1 - 60.9) | |

| CD4 cell count cells/uL | Median, Interquartile Range (IQR) | 61 | 27 – 105 |

| CD4 Band at CRAM Entry | CD4 < 50 Cell/uL | 34 (41.0) | (30.3 – 52.3) |

| CD4 [51-99] Cell/uL | 27 (32.5) | (22.7 – 43.6) | |

| CD4 > 100 Cell/uL | 22 (26.5) | (17.4 – 37.4) | |

| Antifungal therapy prior to CRAM | Antifungal therapy initiated at CRAM | 38 (45.8) | (35.4 - 56.5) |

| Antifungal therapy prior to CRAM | 45 (54.2) | (43.5 - 64.6) | |

| Induction therapy at CRAM | No (amphotericin received at other HF) | 31 (37.3) | (27.5 - 48.0) |

| Yes (amphotericin received at CRAM) | 52 (62.7) | (52.0 - 72.5) | |

| Amphotericin | Single Dose | 39 (47.0) | (36.5 - 57.7) |

| Multiple Dose | 44 (53.0) | (42.3 - 63.5) | |

| ART vs CM Timeline | Pre-ART or ≤ 30 days on ART | 39 (47.0) | (36.5 - 57.7) |

| Experienced ART > 30 days and active | 21 (25.3) | (16.9 - 35.4) | |

| Experienced ART > 30 days but with ART interruption on admission | 23 (27.7) | (19.0 - 38.0) | |

| Clinical features: Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | 4 (4.8) | (1.6 - 11.1) |

| Symptomatic | 79 (95.2) | (88.9 - 98.4) | |

| Clinical features: Cefaleia | No headache | 5 (6.0) | (2.3 - 12.7) |

| headache | 78 (94.0) | (87.3 - 97.7) | |

| Clinical features: Vomiting | No vomiting | 56 (67.5) | (56.9 - 76.8) |

| Vomiting | 27 (32.5) | (23.2 - 43.1) | |

| Clinical features: Agitation/bizarre behavior, Incoherent speech, Delusions and/or hallucination | No Agitation/bizarre behavior | 67 (80.7) | (71.3 - 88.1) |

| Agitation/bizarre behavior | 16 (19.3) | (11.9 - 28.7) | |

| Clinical features: Meningeal signs | No Meningeal signs | 57 (68.7) | (58.2 - 77.9) |

| Meningeal signs | 26 (31.3) | (22.1 - 41.8) | |

| Clinical features: Decreased visual acuity/Blindness | No Decreased visual acuity/Blindness; | 64 (77.1) | (67.2 - 85.1) |

| Decreased visual acuity/Blindness; | 19 (22.9) | (14.9 - 32.8) | |

| Clinical features: Photophobia | No Photophobia | 67 (80.7) | (71.3 - 88.1) |

| Photophobia | 16 (19.3) | (11.9 - 28.7) | |

| Clinical features: Diplopia /CN-VI palsy | No Diplopia /CN-VI palsy | 75 (90.4) | (82.6 - 95.3) |

| Diplopia /CN-VI palsy | 8 (9.6) | (4.7 - 17.4) | |

| Clinical features: Hypoacusis | No Hypoacusis | 75 (90.4) | (82.6 - 95.3) |

| Hypoacusis | 8 (9.6) | (4.7 - 17.4) | |

| Clinical features: Seizures | No Seizures | 77 (92.8) | (85.7 - 96.9) |

| Seizures | 6 (7.2) | (3.1 - 14.3) | |

| Clinical features: Reduced Glasgow Coma Scale | No Reduced GCS | 82 (98.8) | (94.5 - 99.9) |

| Reduced | 1 (1.2) | (0.1 - 5.5) | |

| Frequency of lumbar punctures (LP) | Not performed | 4 (5.1) | (1.4 - 12.5) |

| 1 LP (initial) | 34 (43.0) | (32.1 - 54.6) | |

| 2-5 LP | 38 (48.1) | (36.9 - 59.5) | |

| ≥6 LP | 7 (8.9) | (3.6 - 17.5) | |

| Opening cerebrospinal fluid pressure (OP CSF) | OP CSF ≤20 cmH₂O | 9 (12.9) | (6.1 - 23.0) |

| OP CSF [21-40] cmH₂O | 29 (41.4) | (29.9 - 53.7) | |

| OP CSF ≥41 cmH₂O | 32 (45.7) | (34.0 - 57.9) | |

| Other Active Opportunistic Disease: TB | No Acive TB | 36 (43.4) | (33.1 - 54.1) |

| Active TB | 47 (56.6) | (45.9 - 66.9) | |

| Other Active Opportunistic Disease: Oral Candida | No Active Oral Candida | 65 (78.3) | (68.6 - 86.1) |

| Active Oral Candida | 18 (21.7) | (13.9 - 31.4) | |

| Other Active Opportunistic Disease: Chronic Diarrhoea | No Active Chronic diarrhea | 77 (92.8) | (85.7 - 96.9) |

| Active Chronic Diarrhea | 6 (7.2) | (3.1 - 14.3) | |

| Active Opportunistic Disease: Kaposi sarcoma | No Kaposi Sarcoma | 78 (94.0) | (87.3 - 97.7) |

| Active Kaposi Sarcoma | 5 (6.0) | (2.3 - 12.7) | |

| Table 2: Adverse drug reactions of antifungal treatment for cryptococcal meningitis at CRAM, Mozambique 2020–2024, | (N=52) | ||||||

|

Parameter (Day 1 vs. Day 3) |

1st Day (Mean ± SD), [n] | 3rd Day (Mean ± SD), [n] | Mean Paired Diff | t-value | p-value | |

| Hgb (g/dL) | 11.2 ± 1.8 (n=52) | 10.6 ± 2.0 (n=38) | -0.6 | +4.73 | <0.001 | ↓ |

| K+ (mmol/L) | 4.27 ± 0.66 (n=49) | 3.86 ± 0.78 (n=40) | -0.26 | -2.81 | 0.008 | ↓ |

| Creat (mg/dL) | 0.83 ± 0.42 (n=52) | 1.13 ± 0.64 (n=40) | +0.39 | +3.46 | 0.001 | ↑ |

|

Parameter (Day 3 vs. Day 7) |

3rd Day (Mean ± SD), [n] | 7th Day (Mean ± SD), [n] | Mean Paired Diff | t-value | p-value | |

| Hgb (g/dL) | 10.6 ± 2.0 (n=38) | 10.6 ± 1.8 (n=38) | +0.05 | +0.35 | 0.738 | --- |

| K+ (mmol/L) | 3.86 ± 0.78 (n=40) | 3.97 ± 0.61 (n=38) | +0.11 | +0.23 | 0.175 | --- |

| Creat (mg/dL) | 1.13 ± 0.64 (n=40) | 0.99 ± 0.43 (n= 40) | -0.14 | -0.91 | 0.370 | --- |

| Abbreviations: SD = Standard Deviation; n = sample size; NS = Not Significant (p > 0.05), Diff = Differences | ||||||

| Table 3: Retention and Attrition Trends in MCC Follow-up |

Cochran-Armitage test for trend, p-value |

||||||

| Follow-up Period | Retained, N (%) | Censored = Died + Lost to Follow-up (LFU) + Transferred Out (TO) | Total, N (%) | ||||

| Censored, N (%) | Died, N (%) | LFU, N (%) | TO, N (%) | ||||

| 6 months | 68 (81.9) | 15 (18.1) | 9 (10.8) | 3 (3.6) | 3 (3.6) | 83 (100) | <0.001 |

| 12 months | 54 (74.0) | 19 (26.0) | 10 (13.7) | 5 (6.8) | 4 (5.5) | 73 (100) | |

| 24 months | 38 (70.4) | 16 (29.6) | 7 (13.0) | 4 (7.4) | 5 (9.3) | 54 (100) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).