1. Introduction

Biometric authentication has become a central component of secure digital interactions, enabling reliable identity verification across consumer electronics, financial services, transportation systems, and regulated industrial environments. As digital ecosystems expand, regulatory frameworks increasingly require authentication methods that provide both robust security and low user friction. The forthcoming Payment Services Directive 3 (PSD3) and the accompanying Payment Services Regulation (PSR) introduce stricter requirements for Strong Customer Authentication (SCA), favoring biometric modalities that support continuous or passive verification, maintain resilience to spoofing, and ensure that sensitive biometric data remain processed securely on-device. These provisions encourage the development of wearable-integrated biometric systems that combine high security, transparency, and user convenience—particularly in contexts such as payments, physical access, and mobile identity services.

Traditional biometric technologies—such as fingerprints, facial recognition, and iris scanning—remain dominant in authentication systems, yet they exhibit persistent limitations under real-world conditions. Fingerprint recognition is highly sensitive to humidity, dryness, sensor aging, and dermatological conditions, which degrade data quality and lead to elevated error rates [

1,

2,

3]. Spoofing attacks using synthetic fingerprints, 3D casts, or latent prints remain a major concern despite recent progress in presentation attack detection [

4,

5,

6]. Face and iris biometrics, although contactless, are affected by illumination changes, occlusion, pose variability, and can be deceived by high-quality masks or replay attacks [

7,

8,

9]. These systems frequently require explicit and precise user interaction—stable pose, correct gaze direction, consistent finger placement—which reduces throughput and limits usability in mobile or public environments [

10,

11]. Additionally, the hygiene concerns associated with contact-based fingerprint scanners, highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic, have increased demand for hygienic, seamless, and unobtrusive alternatives [

12,

13].

Driven by these limitations, research has increasingly turned toward wrist-based physiological and behavioral biometrics, which offer contactless acquisition, higher usability, improved integration with wearable devices, and naturally embedded liveness cues that enhance spoofing resistance. Ultrasonic impedance features used in the WristPass system enable secure continuous authentication with 96.7% accuracy [

14]. Photoplethysmography-based “PressHeart” authentication reports 94.9% accuracy by exploiting individualized pressure-induced hemodynamic responses [

15]. Soft wrist-worn arrays combining EMG and pressure sensing achieve gesture-recognition accuracies above 86% [

16]. Other physiological traits at the wrist – such as subcutaneous vein patterns—can be captured using RGB or NIR imaging, with error rates frequently below 2% and as low as <0.1% when using specialized NIR hardware [

17,

18,

19]. Recent work has also demonstrated that the wrist exhibits rich surface ridge micro-features, including bifurcations, ridge endings, and bridges, which can be detected using deep learning architectures such as YOLOv11 and its derivatives, achieving detection accuracies above 94% [

10,

20,

21]. Complementary behavioral modalities arising from wrist motion dynamics, handwriting patterns, and electromyographic activity provide additional user-discriminative signatures. Wrist-motion and handwriting-based authentication approaches have shown strong feasibility [

22], while EMG-based methods report stable multi-day performance with equal error rates around 3–4% [

23,

24,

25]. Collectively, these emerging modalities expand the wrist into a versatile multimodal biometric site, offering a balance of accuracy, usability, and spoofing resistance that directly responds to – and in many cases alleviates – key limitations of traditional biometric systems.

Despite these advances, high-resolution inner wrist skin micro-topography remains a largely unexplored modality. Anatomically, the inner wrist features stable ridge-like patterns analogous to fingerprints, yet its biometric potential has not been systematically evaluated using compact, off-the-shelf sensors. Leveraging this region would enable secure, intuitive authentication embedded directly into wrist-worn objects such as smartwatch straps, medical wearables, and watch clasps—without requiring explicit user action.

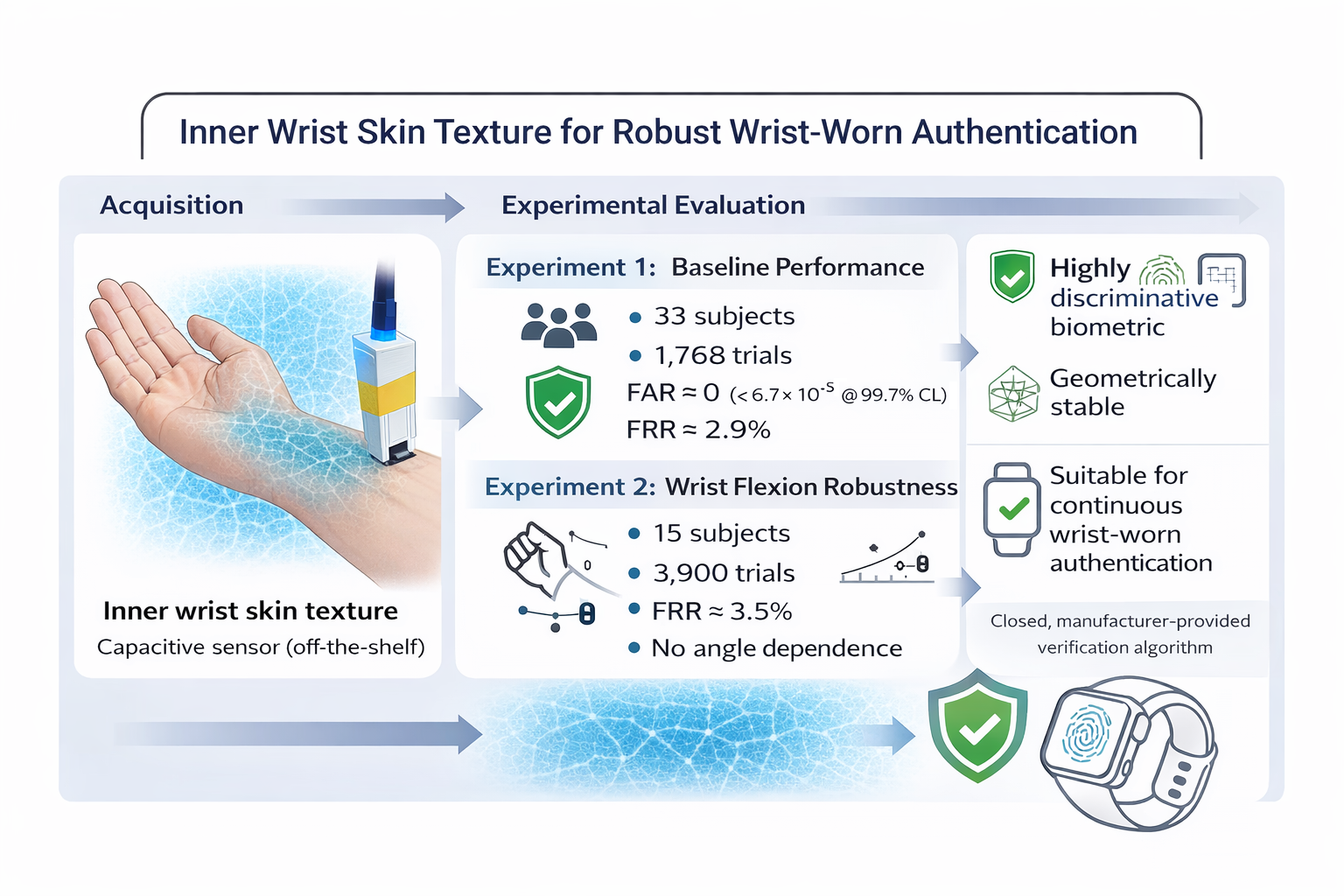

This study investigates the feasibility and accuracy of wrist skin print–based authentication using a commercial capacitive fingerprint sensor, with the objective of determining whether standard template-based biometric methods can reliably extract, represent, and match micro-texture patterns from the inner wrist. Using the BM-Lite development kit (Fingerprint Cards AB, Sweden) as a representative off-the-shelf platform, we evaluate wrist skin print acquisition repeatability, sensitivity to sensor placement consistency, and overall matching performance under realistic handling conditions. Two complementary experimental protocols were designed. Experiment 1 provides a controlled assessment of the intrinsic discriminative capability of wrist skin prints, using classical biometric performance metrics such as false acceptance rate (FAR) and false rejection rate (FRR). This experiment establishes a baseline performance reference for comparison with established biometric security benchmarks. Experiment 2 examines the impact of wrist flexion and re-positioning on authentication performance, specifically assessing whether changes in wrist angle influence verification outcomes. By decoupling posture-related effects from acquisition variability, this experiment evaluates robustness to changes in wrist orientation that may occur during everyday use. Taken together, these experiments are designed to provide quantitative estimates of key performance parameters and a structured assessment of robustness under representative operating conditions.

The work presented here directly supports the technological vision outlined in our patent-pending system, WO 2025/177176 – Wrist-Worn Device for Biometric User Identity Verification, which proposes a framework for secure, on-device wrist-based biometric authentication tailored to future wearable ecosystems and forthcoming PSD3/PSR regulatory requirements. The experimental findings reported in this paper assess the practical viability of inner-wrist skin prints as a standalone biometric modality of inner-wrist skin prints as a standalone biometric modality when implemented using commercially available fingerprint sensing hardware, under both controlled and representative handling conditions. By characterizing security- and usability-related performance metrics and robustness to wrist repositioning, the study provides an empirical basis for future system-level developments, including robustness to wrist repositioning and multimodal extensions. In this way, the present study contributes empirical evidence relevant to the longer-term development of wrist-worn authentication solutions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup

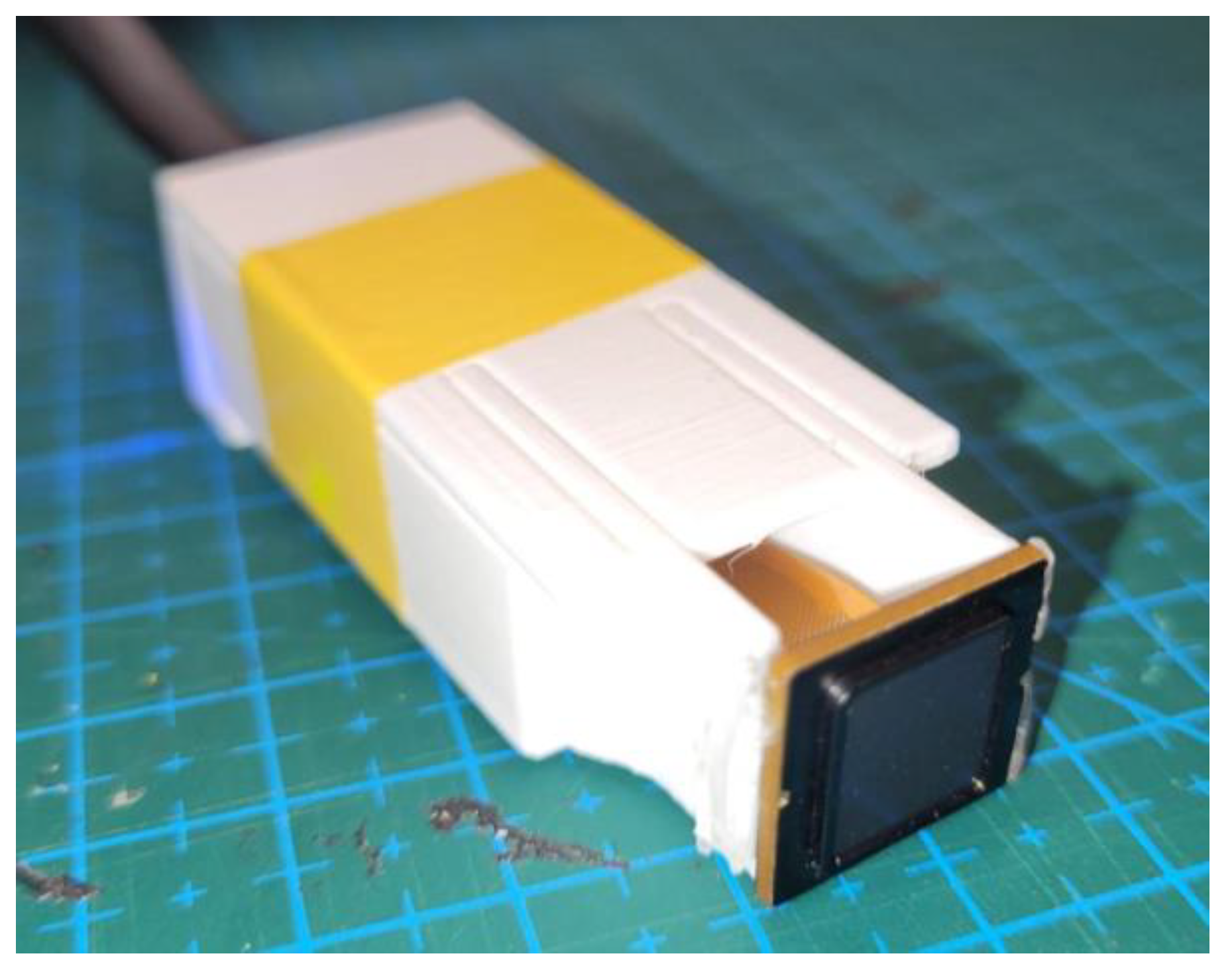

For the experimental evaluation of wrist skin print authentication, the BM-Lite Development Kit (Fingerprint Cards AB, Sweden) was used. The BM-Lite is a compact, off-the-shelf biometric module intended for embedded authentication applications and integrates a capacitive fingerprint sensor, processing unit, and onboard template storage.

The sensor features an active area of 8 × 8 mm, a spatial resolution of 508 dpi, and captures 8-bit grayscale images suitable for high-resolution acquisition of fingerprint-like skin texture patterns. Although primarily designed for fingerprint acquisition, the module was used without hardware modification to capture wrist skin texture patterns.

The sensor module was embedded in a custom 3D-printed casing designed for manual handling (

Figure 1). The casing facilitated consistent sensor handling during data acquisition while allowing manual control of contact conditions. All signal processing, template extraction, and matching were performed locally on the BM-Lite module.

2.2. Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

All experiments involving human subjects were conducted in accordance with ethical standards and were approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the Warsaw University of Technology (certificate no. 04/06/2025).

Prior to participation, all subjects were fully informed about the nature and purpose of the study, the procedures involved, potential risks, and their right to withdraw from the examination at any time without consequences. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. For participants who were minors (three cases), written informed consent was obtained from their legal representatives.

2.3. Experiment 1: Controlled-Condition Wrist Skin Print Acquisition

2.3.1. Data Acquisition Protocol

In the first experiment, participants were examined under controlled acquisition conditions. To facilitate consistent localization of the measurement area across repeated acquisitions, a single pen mark was applied to the examined wrist region as a visual reference for the operator. Both wrists were included, with skin prints acquired from two distinct locations on the inner (volar) side of each wrist, resulting in four measurement areas per participant.

For each measurement location, an enrollment procedure was performed in accordance with the sensor manufacturer’s recommended workflow, resulting in the generation of a reference template used for all subsequent authentication attempts. Following enrollment, at least 10 verification attempts were conducted for each location, with a mean of 11.74 attempts. All verification trials were performed manually by the experimenter using a handheld sensor assembly. Consequently, authentication performance reflects both the intrinsic properties of the wrist skin print modality and variability arising from manual sensor placement and skin–sensor contact conditions.

2.3.1. Participants

A total of 33 participants took part in Experiment 1, including 21 male and 12 female subjects. The mean participant age was 30.0 ± 16.9 years, with a minimum age of 10 years and a maximum age of 71 years. In total, 1,768 authentication trials were collected in Experiment 1.

2.4. Experiment 2: Wrist Flexion Study

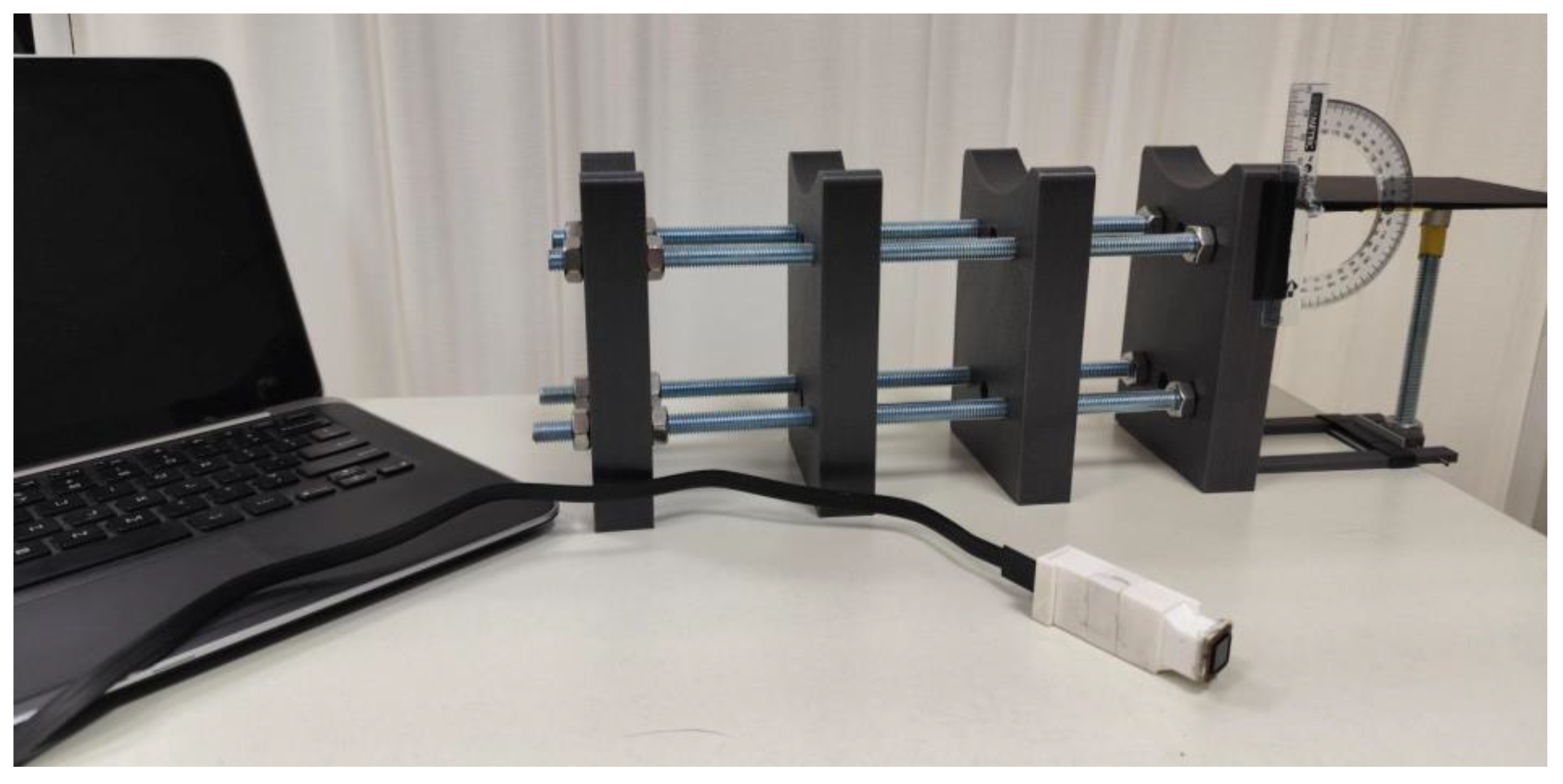

2.4.1. Mechanical Setup and Protocol

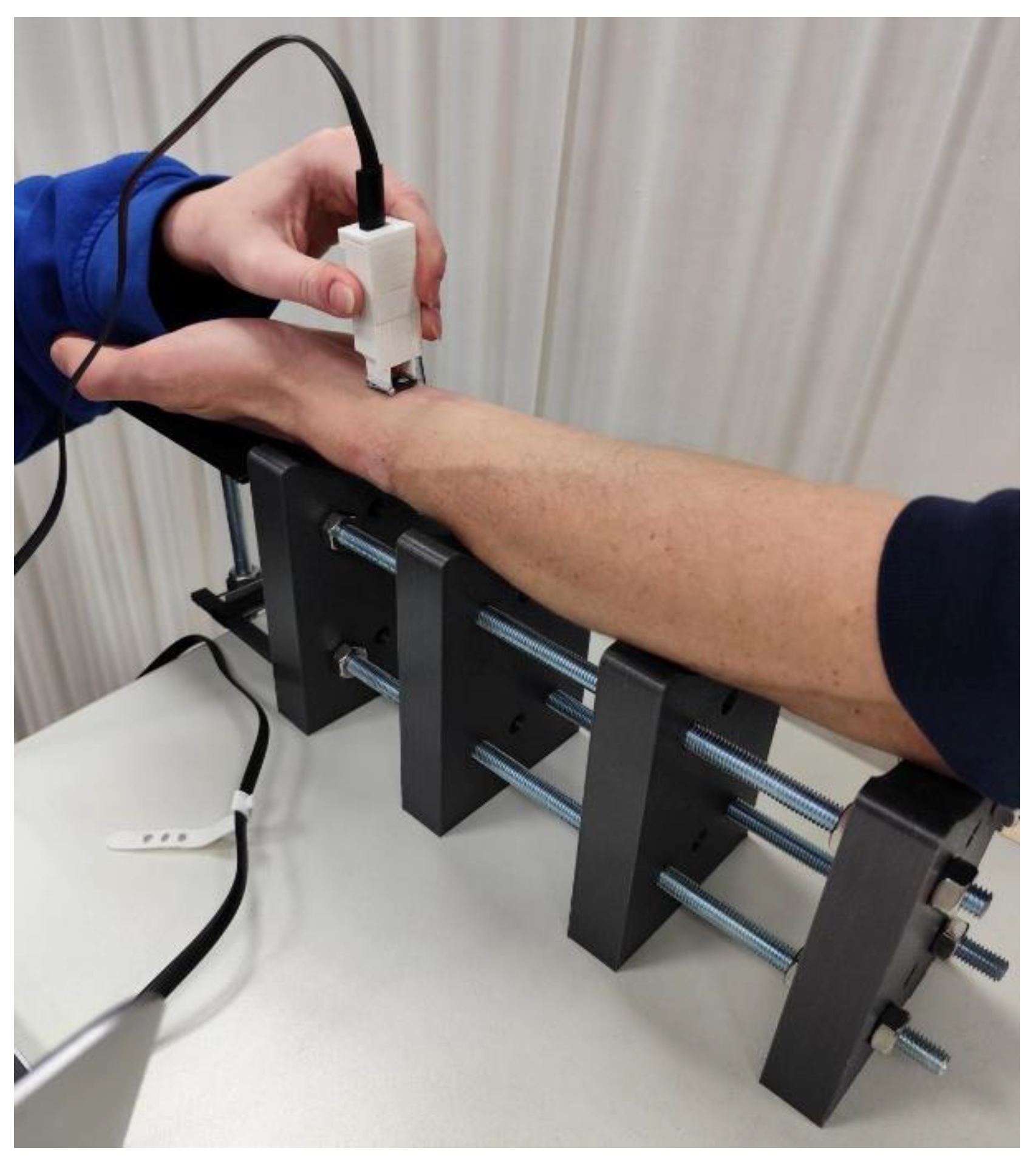

The second experiment was designed to assess the influence of wrist flexion on wrist skin print authentication performance. During testing, the participant’s forearm was positioned on a custom support assembly composed of four profiled 3D-printed blocks to stabilize the forearm and minimize unintended motion. The hand rested on a pivoting platform with its axis of rotation aligned with the wrist joint.

Wrist flexion was adjusted manually using a threaded rod mechanism, allowing precise and repeatable positioning over a range of −30° to +30° relative to the horizontal plane, in 5° increments. Authentication performance was quantified using the false rejection rate (FRR) evaluated at each discrete wrist angle. Enrollment was performed at the neutral wrist position (0°), and verification attempts acquired at each angle were matched against the corresponding reference templates.

For each participant, two distinct locations on the inner (volar) side of the left wrist were examined. Enrollment was performed in accordance with the sensor manufacturer’s recommended procedure. Ten verification attempts were then performed for each combination of wrist angle and measurement location.

Figure 2.

Hand supporting frame with pivoting platform for hand positioning.

Figure 2.

Hand supporting frame with pivoting platform for hand positioning.

Figure 3.

Hand of a volunteer during examination on the pivoting platform.

Figure 3.

Hand of a volunteer during examination on the pivoting platform.

2.4.2. Participants

A total of 15 volunteers participated in Experiment 2, including 11 male and 4 female subjects. The mean participant age was 30.9 years, with a minimum age of 18 years and a maximum age of 49 years. In total, 3900 authentication trials were recorded in Experiment 2.

2.5. Authentication and Matching Procedure

Authentication was performed using the verification functionality implemented in the BM-Lite development kit, operating in a one-to-one (1:1) comparison mode. For each enrolled measurement location, a reference template was generated during the enrollment phase in accordance with the sensor manufacturer’s recommended workflow. During verification, each newly acquired wrist skin print was processed by the module’s internal feature extraction algorithm and compared against the corresponding stored reference template.

The matching process yielded a binary verification decision—accept or reject—based on internally defined similarity thresholds embedded in the BM-Lite firmware. These decision thresholds are fixed and not accessible to the user, reflecting the behavior of a commercially realistic, ready-to-use biometric module rather than a configurable research prototype. No raw images, intermediate features, or similarity scores were exposed during operation.

All signal processing, template generation, and matching operations were executed locally on the BM-Lite module. Throughout the experiments, biometric data remained confined to the device, with no external transmission or off-device processing. This configuration ensured that authentication outcomes reflected on-device performance and avoided confounding effects related to external computation or data handling.

For Experiment 1, each verification attempt was evaluated against the enrolled template associated with the corresponding wrist location, producing outcomes classified as true positives, false negatives, true negatives, or false positives depending on the origin of the presented wrist skin print. In Experiment 2, verification attempts acquired at varying wrist flexion angles were matched against templates enrolled at the neutral wrist position, and authentication outcomes were used to assess robustness to wrist repositioning.

2.6. Definition of Genuine and Impostor Comparisons (Experiment 1)

In Experiment 1, authentication outcomes were categorized as genuine or impostor comparisons based on the relationship between the verification attempt and the enrolled reference template. A genuine comparison was defined as a verification attempt originating from the same participant and the same enrolled measurement location as the reference template used for matching. Successful genuine comparisons were classified as true positives (TP), while unsuccessful genuine comparisons were classified as false negatives (FN).

An impostor comparison was defined as a verification attempt originating either from a different participant or from a wrist location that was not enrolled for the reference template being evaluated. This definition includes both inter-subject impostor attempts and intra-subject attempts involving un-enrolled wrist locations. Impostor comparisons resulting in rejection were classified as true negatives (TN), whereas any acceptance of an impostor attempt was classified as a false positive (FP).

This classification framework enabled a clear separation between genuine and impostor presentations and provided the basis for computing false acceptance and false rejection rates under controlled acquisition conditions.

2.7. Performance Evaluation Metrics

System performance was evaluated using standard biometric verification metrics, specifically the false acceptance rate (FAR) and false rejection rate (FRR).

False acceptance rate (FAR) is defined as:

False rejection rate (FRR) is defined as:

These metrics were calculated directly from the authentication outcomes produced by the BM-Lite module for genuine and impostor comparisons in Experiment 1.

As the verification algorithm implemented in the BM-Lite module operates as a closed, ready-to-use system with internally fixed decision thresholds, it was not possible to adjust operating points or perform threshold sweeps. Consequently, estimation of the equal error rate (EER) was not feasible, and this metric is therefore not reported in the present study.

To quantify the false acceptance rate (FAR) in the absence of observed false acceptances, an exact one-sided binomial confidence bound was employed. Impostor authentication attempts were modeled as independent Bernoulli trials with the probability of success corresponding to a false acceptance event. For zero observed events (k=0) across nimpostor comparisons, the upper confidence limit for the true FAR was computed using the exact Clopper–Pearson method, given by:

where

denotes the significance level. This approach yields a conservative and statistically rigorous upper bound on the FAR and is commonly used in biometric performance evaluation when no false acceptances are observed [

26].

In Experiment 2, performance evaluation was limited to analysis of the false rejection rate as a function of wrist flexion angle.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Collected Data

Two experimental studies were conducted to evaluate the feasibility and robustness of wrist skin print–based authentication using an off-the-shelf biometric module.

In Experiment 1 (controlled conditions), data were collected from 33 participants, resulting in a total of 1,768 authentication trials. Each trial generated one genuine comparison and multiple impostor comparisons, yielding a total of 86,897 impostor comparison events used for the estimation of false positive and true negative outcomes. This experiment was designed to quantify baseline authentication performance in terms of false acceptance rate (FAR) and false rejection rate (FRR) under manual acquisition conditions.

In Experiment 2 (wrist flexion study), data were collected from 15 participants, resulting in 3,900 authentication trials. In this experiment, enrollment was performed at a neutral wrist position, and subsequent verification attempts were acquired across a controlled range of wrist flexion angles. Performance evaluation in Experiment 2 focused exclusively on the analysis of false negative events as a function of wrist angle; impostor comparisons and false positive metrics were not considered.

The results of the two experiments are reported separately in the following sections, reflecting their distinct objectives and evaluation methodologies.

3.2. Authentication Performance Under Steady Conditions

3.2.1. Overall False Acceptance and False Rejection Rates

Under controlled acquisition conditions, the wrist skin print authentication system demonstrated strong baseline performance. Across a total of 1,768 authentication trials—including 265 scans acquired from un-enrolled wrist locations—the system yielded 1,478 true positive (TP) outcomes and 44 false negative (FN) events for genuine comparisons (

Table 1). For impostor testing, 86,897 presentations were evaluated, all of which were correctly rejected, resulting in 86,897 true negative (TN) outcomes and no false positives (FP = 0) (

Table 1).

3.2.2. Effect of Manual Sensor Placement

All wrist skin print acquisitions in Experiment 1 were performed manually by the operator using a handheld sensor assembly, introducing natural variability in sensor positioning, contact location, and applied pressure. This acquisition mode was intentionally selected to reflect realistic usage conditions rather than optimized laboratory alignment.

Given the relatively small number of observed false negative events (FN = 44), it is difficult to draw statistically robust conclusions regarding the specific influence of manual sensor placement on authentication performance. While manual positioning variability can reasonably be assumed to contribute to some of the observed false negatives, the limited number of such events prevents reliable attribution of errors to individual acquisition factors.

Nevertheless, despite the absence of controlled positioning aids, the resulting false rejection rate of approximately 2.9% remains within a range generally considered acceptable for practical biometric authentication systems and is consistent with usability expectations associated with FIDO-compliant biometric modalities. This indicates that wrist skin print authentication retains stable performance even under non-ideal, manually controlled acquisition conditions.

3.3. Authentication Performance Under Wrist Flexion

3.3.1. Overall False Rejection Rates

In Experiment 2, authentication performance under wrist flexion was evaluated exclusively in terms of false negative events, with enrollment performed at a neutral wrist position and verification attempts acquired across a controlled range of wrist angles.

Aggregating all verification attempts across the examined wrist flexion range and measurement locations, the overall FRR was equal to 3.52%. This value reflects the cumulative effect of wrist posture variation on authentication reliability relative to the enrolled neutral-position templates.

3.3.2. False Rejection Rate as a Function of Wrist Angle

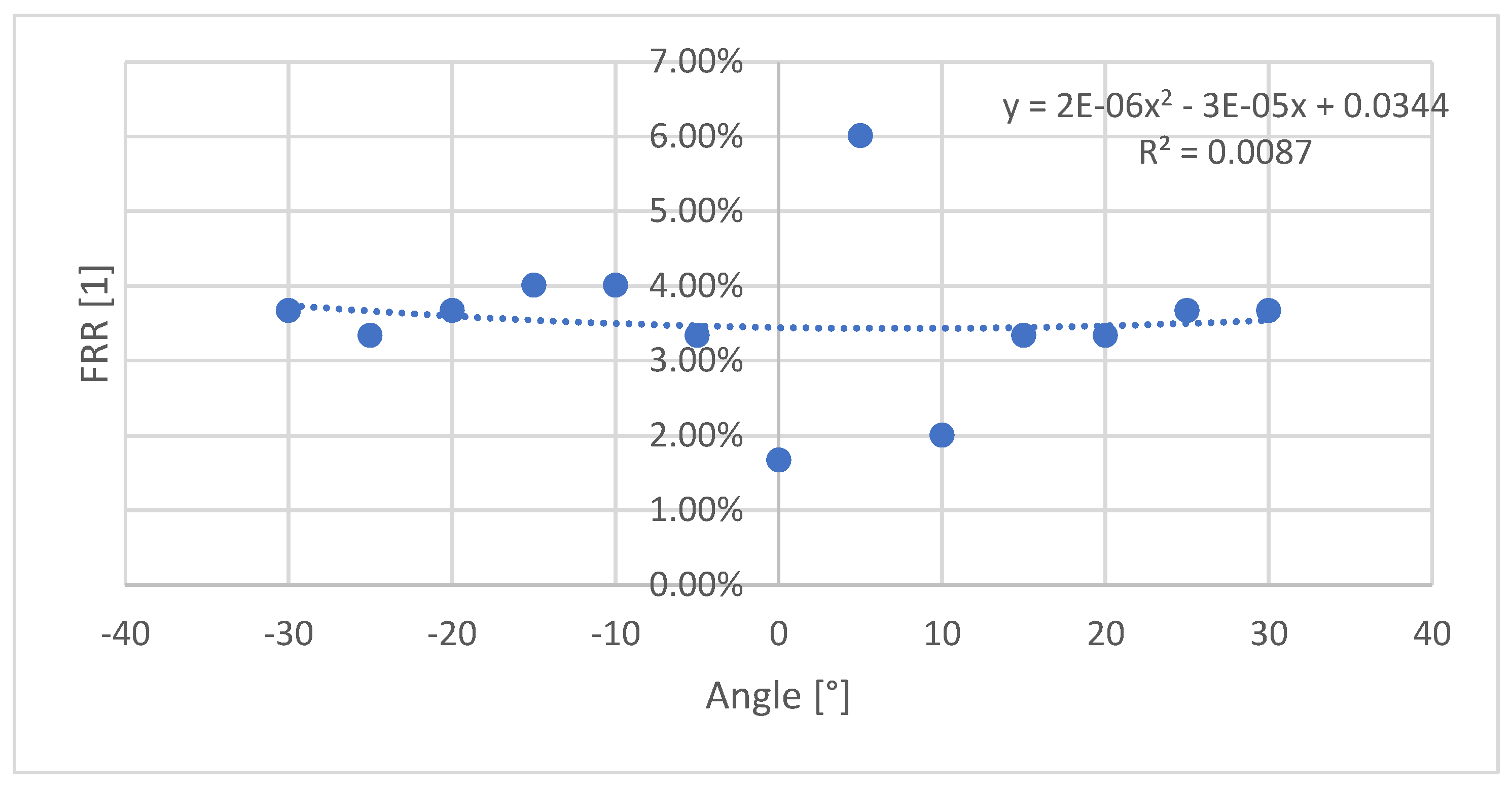

Figure 4 shows the false rejection rate (FRR) as a function of wrist angle. The lowest FRR was observed at the neutral position (0°), with a value of 1.67%. At non-zero angles, FRR values ranged from 2.01% to 6.02%, with the maximum observed at +5°.

A quadratic polynomial fit applied to the FRR–angle relationship yielded a coefficient of determination of R² = 0.0087, indicating that wrist angle accounts for less than 1% of the observed FRR variability. Accordingly, no systematic or monotonic dependence of FRR on wrist angle was identified within the examined range, aside from the expected performance improvement at the enrollment position.

3.3.2. Qualitative Observations on the Scanning Procedure

In Experiment 2, enrollment was performed at the neutral wrist position (0°), and the corresponding verification scans were acquired without altering the position of the participant’s hand between enrollment and the initial verification attempts. This stationary transition between enrollment and scanning may have contributed to the lower false rejection rate observed at the neutral position.

For verification attempts acquired at non-zero wrist angles, the operator adjusted the position of the participant’s hand by modifying the wrist angle using the pivoting platform. Although the target skin region was visually marked to assist with repositioning, each adjustment required re-establishing contact between the sensor and the skin. Consequently, these scans were likely subject to increased variability in sensor placement, contact conditions, and local skin deformation compared to scans acquired without repositioning.

4. Discussion

The results presented in this study demonstrate that wrist skin print authentication, implemented using an off-the-shelf capacitive fingerprint sensor and a closed, manufacturer-defined verification algorithm, can achieve a favorable balance between security and practical usability under realistic acquisition conditions. In particular, the absence of false positives across a large number of impostor comparisons implies a very low likelihood of unauthorized acceptance, while the observed false rejection rates remain within ranges commonly regarded as acceptable for wearable biometric systems.

4.1. Security Performance in the Context of Non-Traditional Biometrics

The most notable outcome of Experiment 1 is the absence of false positives across 86,897 impostor comparisons, which permits a statistically justified upper bound of 6.7 × 10⁻⁵ to be placed on the false acceptance rate (FAR) at the 99.7% confidence level, based on the exact one-sided binomial upper bound) [

27]. This bound is substantially lower than the FAR requirements defined for FIDO BioLevel 1 (1:100) and BioLevel 2 (1:10,000), and approaches the more stringent FAR targets (e.g., 0.002% = 1:50,000) discussed in FIDO guidance for claims involving enhanced security assurances [

28]. Notably, this level of security performance exceeds FAR values reported for other non-traditional wrist-based biometric modalities, including photoplethysmography (PPG)-based authentication and dorsal hand vein recognition systems evaluated under laboratory or semi-controlled conditions [

29,

30,

31,

32].

Prior studies have shown that skin texture and micro-topography contain highly distinctive features that can support reliable user discrimination, even when acquired from body regions other than fingertips [

33]. The present results extend these findings by demonstrating that such features can be captured from the volar wrist using commodity hardware, without algorithmic customization, while still achieving very strong resistance to impostor acceptance.

4.2. Usability and False Rejection Rates

The false rejection rates observed in this study (approximately 2.9% under steady conditions and 3.52% under wrist flexion) are consistent with FRR values reported for wrist-based wearable biometrics in the literature. Reviews and experimental studies of wrist-based PPG authentication commonly report FRR values in the range of 2–4% under controlled conditions, with higher values observed under motion or placement variability [

29,

30]. From this perspective, the FRR values reported here indicate usability comparable to other wearable biometric modalities, despite the use of a closed algorithm and manual acquisition.

It is important to note that the present study did not aim to optimize the trade-off between FAR and FRR through threshold tuning, as the verification algorithm operated with fixed, manufacturer-defined decision criteria. As a result, the reported FRR values should be interpreted as reflecting the behavior of a commercially realistic, fixed-threshold system rather than an optimally tuned research prototype. From a security perspective, the false acceptance rate (FAR) is the primary determinant of the system’s actual safety, particularly in fintech and payment-related applications where unauthorized access carries direct financial risk. In contrast, the false rejection rate (FRR) predominantly affects user experience, influencing perceived usability and convenience rather than core security guarantees.

4.3. Influence of Wrist Flexion and Acquisition Variability

Experiment 2 examined the influence of wrist flexion on authentication performance and found no measurable correlation between wrist angle and the false rejection rate (FRR) across the evaluated range. The very low coefficient of determination obtained from polynomial fitting (R² = 0.0087) indicates that wrist angle accounts for only a negligible proportion of the observed FRR variability. This behavior contrasts with several biometric modalities whose performance degrades with changes in body part orientation, suggesting that inner-wrist skin texture is comparatively insensitive to variations in wrist angle.

Instead, the results point to acquisition consistency as the dominant factor influencing performance. This interpretation aligns with prior studies on wearable and contact-based biometrics, which identify sensor placement, contact pressure, and local repositioning as primary contributors to error rates [

33,

34]. In this study, the lowest FRR occurred at the enrollment angle, likely due to minimal repositioning between enrollment and verification, whereas measurements at other angles required re-placement of the wrist on the sensor, introducing additional variability despite visual marking of the acquisition region. Similar findings have been reported for wrist-worn photoplethysmography (PPG) and motion-based biometric systems, where sensor displacement and motion-related artifacts outweigh posture-related effects [

30].

Given the limited number of false negative events and the absence of a systematic relationship between FRR and wrist angle, the observed variations should be interpreted cautiously and cannot be attributed exclusively to wrist flexion.

4.4. Methodological Considerations and Limitations

As with many studies on non-traditional biometrics, the use of an off-the-shelf sensor and a closed verification algorithm introduces limitations in transparency and reproducibility. Previous surveys have emphasized that proprietary algorithms hinder direct cross-study comparison and complicate benchmarking against standardized evaluation frameworks [

33,

35]. While this constraint reflects realistic deployment scenarios, it also limits insight into feature-level behavior and error sources.

Additionally, the experiments were conducted within single sessions for each participant, and long-term stability of wrist skin prints across days or weeks was not evaluated. Longitudinal studies have been identified in the literature as a critical requirement for assessing the robustness and deployability of wearable biometric systems [

34].

4.5. Implications and Future Work

Taken together, the results support the growing body of evidence that non-traditional wrist-based biometric modalities can achieve security and usability levels suitable for practical authentication applications. Wrist skin print authentication offers particular advantages in terms of unobtrusiveness and integration potential for wearable devices, complementing existing fingerprint-based solutions.

Future work should focus on (i) improving control and assessment of acquisition quality to reduce false negatives, (ii) evaluating longitudinal stability under real-world usage conditions, and (iii) exploring multimodal fusion with complementary wrist-based signals, such as inertial or physiological data, as suggested by recent studies on multimodal wearable biometrics [

36]. Such directions would help address current limitations and support more direct comparison with standardized biometric evaluation and certification frameworks.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the feasibility of wrist skin print–based biometric authentication using an off-the-shelf capacitive sensor and a closed, manufacturer-provided verification algorithm. Under steady acquisition conditions, no false acceptances were observed across 86,897 impostor comparisons, corresponding to a conservatively estimated false acceptance rate below 6.7 × 10⁻⁵ at a 99.7% confidence level, while maintaining a false rejection rate of approximately 2.93%. These results indicate a high level of resistance to impostor acceptance combined with practical usability.

Evaluation under controlled wrist flexion yielded an overall false rejection rate of 3.52%. Although the lowest error was observed at the enrollment angle, no systematic dependence of authentication performance on wrist angle was identified, indicating that acquisition variability related to sensor repositioning has a greater impact than wrist posture within the tested range.

The findings experimentally validate key assumptions underlying the patent-pending wrist-worn biometric identity verification system (WO 2025/177176), demonstrating that distinctive wrist skin texture features can support reliable authentication in realistic wearable conditions. This robustness, achieved using commodity hardware, supports the suitability of wrist skin print authentication for practical wrist-worn implementations and motivates future work on longitudinal evaluation, acquisition quality control, and multimodal integration toward real-world deployment.

6. Patents

The concepts investigated in this study are related to a patent-pending wrist-worn biometric identity verification system and method, which covers the use of wrist skin texture as a biometric modality in combination with wearable device architectures. The experimental results reported in this manuscript provide empirical validation of selected assumptions underlying this invention and support its applicability to practical wrist-worn authentication systems (WO 2025/177176).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C. and P.M.; methodology, S.C. and J.Ż.; hardware development, P.L.; software, J.Ł.-M. and N.S.; experimental platform development (Experiment 2), N.S.; investigation, S.C., J.Ł.-M., J.Ż. and N.S.; validation, S.C., J.Ł.-M. and J.Ż.; formal analysis, S.C. and A.Z.; data curation, S.C. and A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C., J.Ż., J.Ł.-M. and A.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.C., J.Ż., J.Ł.-M., A.Z. and P.M.; visualization, S.C.; supervision, P.M.; project administration, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (Ethics Committee) of Warsaw University of Technology (protocol code 04/06/2025, date of approval 24 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the sensitive nature of biometric data, the raw wrist skin print data and individual authentication records cannot be made publicly available. Aggregated statistical results supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of AI-assisted tools for language editing and stylistic refinement of the manuscript (ChatGPT 5.2). The use of these tools did not influence the scientific content, data analysis, or conclusions of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

Invis sp. z o.o. is the owner of the patent related to the wrist-worn biometric technology described in this manuscript and is engaged in the development of related products. Warsaw University of Technology has no financial interest in this development. All experimental work and analyses reported in this study were conducted at Warsaw University of Technology with the objective of independently and objectively characterizing the capabilities of the proposed biometric approach. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TP |

True Positive |

| TN |

True Negative |

| FP |

False Positive |

| FN |

False Negative |

| FAR |

False Acceptance Rate |

| FRR |

False Rejection Rate |

| Dpi |

Dots per inch |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| FIDO |

Fast Identity Online |

References

- Nídlová, V.; Hart, J. Reliability of Biometric Identification Using Fingerprints under Adverse Conditions. Agron. Res. 2015, 13, 786–791. [Google Scholar]

- Riaz, I.; Ali, A.N.; Ibrahim, H. Loss of Fingerprint Features and Recognition Failure Due to Physiological Factors- a Literature Survey. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 87153–87178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.-C.; Chiu, C.-T.; Huang, L.-C.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Hsiao, T.-H. Feature-Aware and Degradation-Driven Image Enhancement for Real-Time Fingerprint Recognition. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2025, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnapatra, S.; Miller-Lynch, C.; Miner, S.; Liu, Y.; Bahmani, K.; Dey, S.; Schuckers, S. Presentation Attack Detection with Advanced CNN Models for Noncontact-Based Fingerprint Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 11th International Workshop on Biometrics and Forensics (IWBF), April 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, B.; Lewicke, A.; Yambay, D.; Schuckers, S. The Effect of Environmental Conditions and Novel Spoofing Methods on Fingerprint Anti-Spoofing Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Workshop on Information Forensics and Security, December 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ametefe, D.S.; Sarnin, S.S.; Ali, D.M.; Ametefe, G.D.; John, D.; Hussin, N. Advancements and Challenges in Fingerprint Presentation Attack Detection: A Systematic Literature Review. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 1797–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajare, H.R.; Ambhaikar, A. Face Anti-Spoofing Techniques and Challenges: A Short Survey. In Proceedings of the 2023 11th International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering & Technology - Signal and Information Processing (ICETET - SIP), April 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Adil, M.; Farouk, A.; Ali, A.; Song, H.; Jin, Z. Securing Tomorrow of Next-Generation Technologies with Biometrics, State-of-The-Art Techniques, Open Challenges, and Future Research Directions. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2025, 57, 100750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, Y.A.U.; Po, L.-M.; Liu, M.; Zou, Z.; Ou, W.; Zhao, Y. Face Liveness Detection Using Convolutional-Features Fusion of Real and Deep Network Generated Face Images. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2019, 59, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GokulaKrishnan, E.; Malathi, G. Exploring Hand Wrist Feature as Biometric Identifier: A Deep Learning Perspective Using Yolov11. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.; Fookes, C.; Sridharan, S.; Denman, S. Feature-Domain Super-Resolution for Iris Recognition. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2013, 117, 1526–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosz, S.A.; Engelsma, J.J.; Liu, E.; Jain, A.K. C2CL: Contact to Contactless Fingerprint Matching. Trans Info Sec 2022, 17, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasokun, G.B.; Akinwonmi, A.E.; Bello, O.A. Baseline Study of COVID-19 and Biometric Technologies. Int. J. Sociotechnology Knowl. Dev. IJSKD 2022, 14, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, X.; Han, J. WristPass: Secure Wearable Continuous Authentication via Ultrasonic Sensing. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/ACM 32nd International Symposium on Quality of Service (IWQoS), June 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, X.; Chen, H. PressHeart: A Two-Factor Authentication Mechanism via PPG Signals for Wearable Devices. In Proceedings of the ICC 2024 - IEEE International Conference on Communications, June 2024; pp. 4662–4667. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, W.; Yang, L.; Gravina, R.; Fortino, G. Soft Wrist-Worn Multi-Functional Sensor Array for Real-Time Hand Gesture Recognition. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 17505–17514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-V.; Horng, S.-J.; Vu, D.-T.; Chen, H.; Li, T. LAWNet: A Lightweight Attention-Based Deep Learning Model for Wrist Vein Verification in Smartphones Using RGB Images. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, R.C.; Sahoo, A. SIFT Based Dorsal Vein Recognition System for Cashless Treatment through Medical Insurance. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 8, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Pal, U.; Ferrer Ballester, M.A.; Blumenstein, M. A New Wrist Vein Biometric System. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence in Biometrics and Identity Management (CIBIM), December 2014; pp. 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.K.; Nandakumar, K.; Ross, A. 50 Years of Biometric Research: Accomplishments, Challenges, and Opportunities. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2016, 79, 80–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyaz, O.; Cam Taskiran, Z.; Yildirim, T. Wrist Vein Recognition by Ordinary Camera Using Phase-Based Correspondence Matching 2017.

- Garcia-Martin, R.; Sanchez-Reillo, R. Wrist Vascular Biometric Recognition Using a Portable Contactless System. Sensors 2020, 20, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; He, J.; Lee, H.; Jiang, N. Multi-Day Analysis of Wrist Electromyogram-Based Biometrics for Authentication and Personal Identification. IEEE Trans. Biom. Behav. Identity Sci. 2023, 5, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; He, J.; Jiang, N. Multi-Day Dataset of Forearm and Wrist Electromyogram for Hand Gesture Recognition and Biometrics. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botros, F.S.; Phinyomark, A.; Scheme, E.J. Day-to-Day Stability of Wrist EMG for Wearable-Based Hand Gesture Recognition. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 125942–125954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clopper, C.J.; Pearson, E.S. The Use of Confidence or Fiducial Limits Illustrated in the Case of the Binomial. Biometrika 1934, 26, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. Estimating Instrument Performance: With Confidence Intervals and Confidence Bounds. NIST, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FIDO Biometrics Requirements. Available online: https://fidoalliance.org/specs/biometric/requirements/Biometrics-Requirements-v3.0-fd-20230111.html (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Sundararajan, K.; Woodard, D.L. Deep Learning for Biometrics: A Survey. ACM Comput Surv 2018, 51, 65:1–65:34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, D.; Martínez-Cruz, A.; Ramírez-Gutiérrez, K.A.; Morales-Sandoval, M. PPG-Based Biometric Authentication: A Review on Architectures, Datasets, Attacks and Security Challenges. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2025, 28, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, F.K.S.; Li, X.; Kong, A.W.-K. A Study of Distinctiveness of Skin Texture for Forensic Applications Through Comparison With Blood Vessels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2017, 12, 1900–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alashik, K.M.; Yildirim, R. Human Identity Verification From Biometric Dorsal Hand Vein Images Using the DL-GAN Method. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 74194–74208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsufyani, H.; Hoque, S.; Deravi, F. Automated Skin Region Quality Assessment for Texture-Based Biometrics. In Proceedings of the 2017 Seventh International Conference on Emerging Security Technologies (EST), September 2017; pp. 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Eberz, S.; Rasmussen, K.B.; Lenders, V.; Martinovic, I. Evaluating Behavioral Biometrics for Continuous Authentication: Challenges and Metrics. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, New York, NY, USA, April 2 2017; Association for Computing Machinery; pp. 386–399. [Google Scholar]

- Gangwar, A.; Joshi, A. Robust Periocular Biometrics Based on Local Phase Quantisation and Gabor Transform. [CrossRef]

- Es-Sobbahi, H.; Radouane, M.; Nafil, K. Multimodal Biometrics: A Review of Handcrafted and AI–Based Fusion Approaches. IET Biom. 2025, 2025, 5055434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).