Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

References

- Zhang, Y.; Gu, S.; Deng, H.; Shen, Z. Global epidemiological profile in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a prediction study. BMJ. Open 2024, 14(12):e091087. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xia, W.; Xu, Z.H.; Suo, Y.X.; Xie, L. Trends in incidence and mortality of nasopharyngeal cancer in China (2004-2018): an age-period-cohort analysis. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15:1592217. [CrossRef]

- Bongiovanni, A.; Vagheggini, A.; Fausti, V.; Mercatali, L.; Calpona, S.; Di Menna, G.; Miserocchi, G.; Ibrahim, T. Induction chemotherapy plus concomitant chemoradiotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: An updated network meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2021, 160:103244. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, F.; Min, X.; Zhang, Q.; Shen, L.J.; Jiang, Y.; Yan, J. Toxicities of chemoradiotherapy and radiotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an updated meta-analysis. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 2832-2847. [CrossRef]

- Ramia, P.; Bodgi, L.; Mahmoud, D.; Mohammad, M.A.; Youssef, B.; Kopek, N.; Al-Shamsi, H.; Dagher, M.; Abu-Gheida, I. Radiation-induced fibrosis in patients with head and neck cancer: A review of pathogenesis and clinical outcomes. Clin. Med. Insights Oncol. 2022, 16:11795549211036898. [CrossRef]

- Kheterpal, S.; Healy, D.; Aziz, M.F.; Shanks, A.M.; Freundlich, R.E.; Linton, F.; Martin, L.D.; Linton, J.; Epps, J.L.; Fernandez-Bustamante, A.; Jameson, L.C.; Tremper, T.; Tremper, K.K.; Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group (MPOG) Perioperative Clinical Research Committee. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of difficult mask ventilation combined with difficult laryngoscopy: a report from the multicenter perioperative outcomes group. Anesthesiology 2013, 119, 1360-1369. [CrossRef]

- Higgs, A.; McGrath, B.A.; Goddard, C.; Rangasami, J.; Suntharalingam, G.; Gale, R.; Cook, T.M.; Difficult Airway Society; Intensive Care Society; Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine; Royal College of Anaesthetists. Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. Br. J. Anaesth. 2018, 120, 323-352. [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, T. Management of the difficult airway. N Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1836-1847. [CrossRef]

- Apfelbaum, J.L.; Hagberg, C.A.; Connis, R.T.; Abdelmalak, B.B.; Agarkar, M.; Dutton, R.P.; Fiadjoe, J.E.; Greif, R.; Klock, P.A.; Mercier, D.; Myatra, S.N.; O’Sullivan, E.P.; Rosenblatt, W.H.; Sorbello, M.; Tung, A. 2022 American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology 2022, 136, 31-81. [CrossRef]

- Huitink, J.M.; Balm, A.J.; Keijzer, C.; Buitelaar, D.R. Awake fibrecapnic intubation in head and neck cancer patients with difficult airways: new findings and refinements to the technique. Anaesthesia 2007, 62, 214-219. [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Ratnayake, G.; Onwochei, D.N.; El-Boghdadly, K.; Ahmad, I. Airway devices for awake tracheal intubation in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Br. J. Anaesth. 2021, 127, 636-647. [CrossRef]

- Law, J.A.; Morris, I.R.; Brousseau, P.A.; de la Ronde, S.; Milne, A.D. The incidence, success rate, and complications of awake tracheal intubation in 1,554 patients over 12 years: an historical cohort study. Can. J. Anaesth. 2015, 62, 736-744. [CrossRef]

- Taboada, M.; Fernández, J.; Estany-Gestal, A.; Vidal, I.; Dos Santos, L.; Novoa, C.; Pérez, A.; Segurola, J.; Franco, E.; Regueira, J.; Mirón, P.; Sotojove, R.; Cortiñas, J.; Cariñena, A.; Peiteado, M.; Rodríguez, A.; Seoane-Pillado, T. First-attempt awake tracheal intubation success rate using a hyperangulated unchannelled videolaryngoscope vs. a channelled videolaryngoscope in patients with anticipated difficult airway: a randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia 2024, 79, 1157-1164. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; El-Boghdadly, K.; Iliff, H.; Dua, G.; Higgs, A.; Huntington, M.; Mir, F.; Nouraei, S.A.R.; O’Sullivan, E.P.; Patel, A.; Rivett, K.; McNarry, A.F. Difficult Airway Society 2025 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult tracheal intubation in adults. Br. J. Anaesth. 2025, Nov 7:S0007-0912(25)00693-2. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, C.V.; Thøgersen, B.; Afshari, A.; Christensen, A.L.; Eriksen, C.; Gätke, M.R. Awake fiberoptic or awake video laryngoscopic tracheal intubation in patients with anticipated difficult airway management: a randomized clinical trial. Anesthesiology 2012, 116, 1210-1216. [CrossRef]

- Alhomary, M.; Ramadan, E.; Curran, E.; Walsh, S.R. Videolaryngoscopy vs. fibreoptic bronchoscopy for awake tracheal intubation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia 2018, 73, 1151-1161. [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.; Schricker, T. Awake videolaryngoscopy versus fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2019, 32, 764-768. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhu, C.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, M.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Xia, J.; Yuan, H.; Yu, Y.; Zou, Z. Comparison of SEEKflex/videolaryngoscopy and fibreoptic bronchoscope for awake tracheal intubation: a randomized clinical trial. BMC. Anesthesiol. 2025, 25(1):360. [CrossRef]

- Oishi, A.; Nomoto, Y.; Nemoto, C.; Inoue, S. Post-radiotherapy suggests a possible difficult airway even with an asymptomatic supraglottic change. JA. Clin. Rep. 2022, 8(1):102. [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Wakita, R,; Ichihashi, Y.; Kutsumizu, C.; Suzuki, C.; Shimada, N.; Maeda, S. Three cases of persistent laryngeal edema postradiation therapy. Anesth. Prog. 2024, 71, 24-28. [CrossRef]

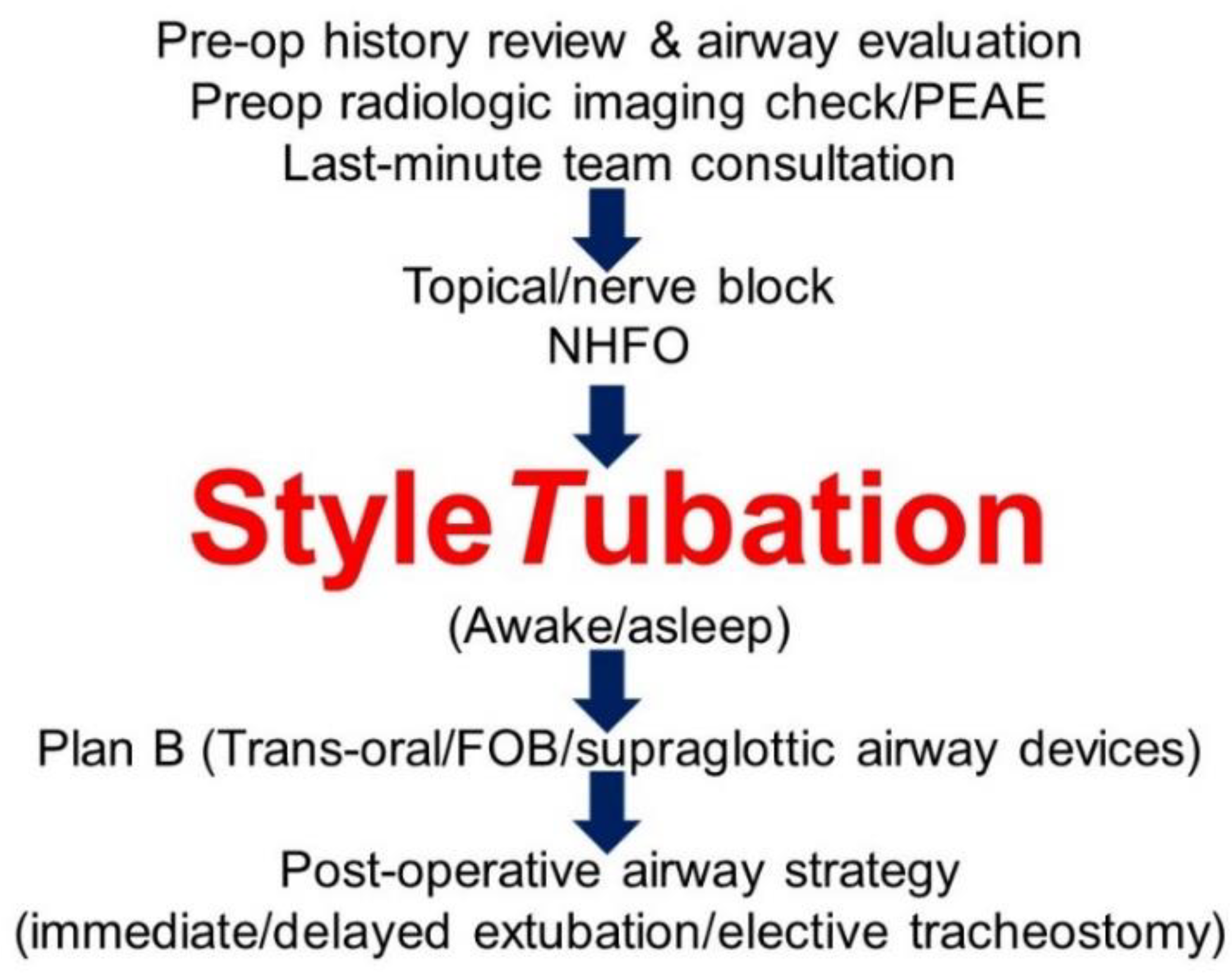

- Luk, H.N.; Qu, J.Z.; Shikani, A. StyleTubation: The paradigmatic role of video-assisted intubating stylet technique for routine tracheal intubation. Asian J. Anesthesiol. 2023, 61, 102-106. [CrossRef]

- Luk, H.N.; Qu, J.Z. StyleTubation versus laryngoscopy: A new paradigm for routine tracheal intubation. Surgeries 2024, 5, 135-161. [CrossRef]

- Cheong, M.W.; Luk, H.N.; Qu, J.Z.; Shikani, A. Four approaches of StyleTubation for handling the orotracheal intubation: A technical tip. Asian J. Anesthesiol. 2024, 62, 100-103. [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.; Kim, S.; Son, Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, H.J.; Jo, H.; Park, J.; Lee, K.; Lee, H.; Rahmati, M.; Woo, S.; Hwang, J.; Kang, J.; Smith, L.; Yon, D.K. Global, regional, and national burden of pharyngeal cancer and projections to 2050 in 185 Countries: A population-based systematic analysis of GLOBOCAN 2022. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2025, 40(30):e177. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, S.; Han, Y.; Feng, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Qu, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Luo, J.; Wu, R.; Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Guo, S.; Wang, J.; Yi, J. Evidence of being cured for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: results of a multicenter patient-based study in China. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2024, 49:101147. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, M.M.; Chen, W.H.; Zhao, J.F.; Chen, W.Q.; Dong, Y.H.; Gong, X.; Chen, Q.Y.; Zhang, L.; Mo, X.K.; Luo, X.N.; Tian, J.; Zhang, S.X. Association of chemoradiotherapy regimens and survival among patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. Netw. Open 2019, 2(10):e1913619. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13619. Erratum in: JAMA. Netw. Open 2019, 2(11):e1917197. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.P.; Ismaila, N.; Chua, M.L.K.; Colevas, A.D.; Haddad, R.; Huang, S.H.; Wee, J.T.S.; Whitley, A.C.; Yi, J.L.; Yom, S.S.; Chan, A.T.C.; Hu, C.S.; Lang, J.Y.; Le, Q.T.; Lee, A.W.M.; Lee, N.; Lin, J.C.; Ma, B.; Morgan, T.J.; Shah, J.; Sun, Y.; Ma, J. Chemotherapy in combination with radiotherapy for definitive-intent treatment of stage II-IVA nasopharyngeal carcinoma: CSCO and ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 840-859. [CrossRef]

- Muthukumar, A.; Dong, W.; Zheng, G. Effects of head and neck radiotherapy on airway management outcomes. JCA. Advances 2024 ,1, 100039. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I.; Dong, W.; Vu, C.N.; Zheng, G. The impact of head and neck radiation on airway management: a retrospective data review. Can. J. Anaesth. 2022, 69, 1562-1564. [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.E.; Camiré, D.; Hwang, P.H.; Nekhendzy, V. Difficult tracheal intubation and airway outcomes after radiation for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Laryngoscope 2024, 134, 120-126. [CrossRef]

- Akazawa, M.; Shimizu, M.; Fujino, Y.; Kato H. Radiation-induced nasopharyngeal fibrosis resulting in a difficult airway: A case report. Cureus 2025, 17(2):e79130. [CrossRef]

- Artime, C.A.; Roy, S.; Hagberg, C.A. The difficult airway. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am. 2019, 52, 1115-1125. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Lin, S.; Zhu, L.; Lin, S.; Pan, J.; Xu, Y. Optimizing the treatment mode for de novo metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma with bone-only metastasis. BMC. Cancer 2022, 22(1):35. [CrossRef]

- Azurdia, A.R.; Walters, J.; Mellon, C.R.; Lettieri, S.C.; Kopelman, T.R.; Pieri, P.; Feiz-Erfan, I. Airway risk associated with patients in halo fixation. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2024, 15:104. [CrossRef]

- White, A.N.; Wong, D.T.; Goldstein, C.L.; Wong, J. Cervical spine overflexion in a halo orthosis contributes to complete upper airway obstruction during awake bronchoscopic intubation: a case report. Can. J. Anaesth. 2015, 62, 289-293. [CrossRef]

- El-Orbany, M. Airway management strategies in patients with halo vest fixation devices. Can. J. Anesth. 2015, 62, 932–933. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.J.; Lee, C.L.; Wang, P.K.; Lin, P.C.; Lai, H.Y. The use of the GlideScope® for tracheal intubation in patients with halo vest. Acta Anaesthesiol. Taiwan 2011, 49, 88-90. [CrossRef]

- Shih, T.L.; Koay, K.P.; Hu, C.Y.; Luk, H.N.; Qu, J.Z.; Shikani, A. The use of the Shikani video-assisted intubating stylet technique in patients with restricted neck mobility. Healthcare (Basel) 2022, 10(9):1688. [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.H.; Cheng, C.P.; Chiu, Y.L.; Hsu, Y.C.; Hu, M.H.; Huang, G.S. Two head positions for orotracheal intubation with the trachway videolight intubating stylet with manual in-line stabilization: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99(17):e19645. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Kim, J.A.; Kim, C.S.; Ahn, H.J.; Yang, M.K.; Choi, S.J. Comparison of tracheal intubation with the Airway Scope or Clarus Video System in patients with cervical collars. Anaesthesia 2011, 66, 694-698. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.C.; Lan, C.H.; Lai, H.Y. The Clarus Video System (Trachway) intubating stylet for awake intubation. Anaesthesia 2011, 66, 1178-1180. [CrossRef]

- Wandell, G.M.; Merati, A.L.; Meyer, T.K. Update on tracheostomy and upper airway considerations in the head and neck cancer patient. Surg. Clin. North Am. 2022, 102, 267-283. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.Y.; Cho, S.; Ryoo, S.H. Anesthetic management for emergency tracheostomy in patients with head and neck cancer: a case series. J. Dent. Anesth. Pain Med. 2022, 22, 457-464. [CrossRef]

- Cleere, E.F.; Read, C.; Prunty, S.; Duggan, E.; O’Rourke, J.; Moore, M.; Vasquez, P.; Young, O.; Subramaniam, T.; Skinner, L.; Moran, T.; O’Duffy, F.; Hennessy, A.; Dias, A.; Sheahan, P.; Fitzgerald, C.W.R.; Kinsella, J.; Lennon, P.; Timon, C.V.I.; Woods, R.S.R.; Shine, N.; Curley, G.F.; O’Neill, J.P. Airway decision making in major head and neck surgery: Irish multicenter, multidisciplinary recommendations. Head Neck 2024, 46, 2363-2374. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; El-Boghdadly, K.; Bhagrath, R.; Hodzovic, I.; McNarry, A.F.; Mir, F.; O’Sullivan, E.P.; Patel, A.; Stacey, M.; Vaughan, D. Difficult Airway Society guidelines for awake tracheal intubation (ATI) in adults. Anaesthesia 2020, 75, 509-528. [CrossRef]

- Huitink, J.M.; Zijp, L. Laryngeal radiation fibrosis: a case of failed awake flexible fibreoptic intubation. Case Rep. Anesthesiol. 2011, 2011:878910. [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, K.A.H.; Gisvold, S.E.; Nordseth, T.; Fasting, S. Incidence, causes, and management of failed awake fibreoptic intubation-A retrospective study of 833 procedures. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2023, 67, 1341-1347. [CrossRef]

- Frerk, C.; Mitchell, V.S.; McNarry, A.F.; Mendonca, C.; Bhagrath, R.; Patel, A.; O’Sullivan, E.P.; Woodall, N.M.; Ahmad, I.; Difficult Airway Society intubation guidelines working group. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br. J. Anaesth. 2015, 115, 827-848. [CrossRef]

- Kolb, B.; Lewis, T.; Large, J.; Wilson, M.; Ode, K. Remimazolam sedation for awake tracheal intubation. Anaesth. Rep. 2024, 12(1):e12298. [CrossRef]

- Bruijstens, L.; Koch, R.; Van Der Wal, R.; Van Eijk, L.; Bruhn, J. Remimazolam for sedation and trachospray for topicalization during flexible nasal intubation in a spontaneously breathing patient. Cureus 2025, 17(1):e77406. [CrossRef]

- El-Boghdadly, K.; Desai, N.; Jones, J.B.; Elghazali, S.; Ahmad, I.; Sneyd, J.R. Sedation for awake tracheal intubation: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Anaesthesia 2025, 80, 74-84. [CrossRef]

- Popal, Z.; Sieg, H.H.; Müller-Wiegand, L.; Breitfeld, P.; Dankert, A.; Sasu, P.B.; Wünsch, V.A.; Krause, L.; Zöllner, C.; Petzoldt, M. Decision-making tool for planning camera-assisted and awake intubation in head and neck surgery. JAMA. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2025, 151, 585-594. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).