1. Introduction

Over the years, employment of robotic technology has increasingly spreading in the surgical field. Robotics is employed in several surgical specialties, facilitating (and sometimes properly enabling) procedures that require great precision in the making. Among these ones, there are thoracic surgery procedures such as pulmonary resection (segmental, lobar, total, atypical) and thymectomy. Alongside surgical improvements, anesthetic techniques and protocols have also evolved, both in terms of pharmacological behavior and airway management. Regarding the latter, in addition to traditional one-lung ventilation (OLV) using standard double-lumen tubes (such as Robert Shaw and similar), the VivaSight™ ™ double-lumen tube has recently emerged. One-lung ventilation (OLV) is an airway management technique that allows to ventilate one lung, leaving the other deflated. The target is to guarantee good surgical exposure while maintaining sufficient oxygenation. The main devices used to perform OLV are DLT and bronchial blockers (BB). The use of DLT is mandatory in lung isolation and in lung resections involving the main bronchus, while BB is recommended in case of difficult airway management, rapid sequence induction, OLV in children, and when postoperative ventilatory support is needed. When OLV is performed, a protective mechanical ventilation is usually set [

1]. Anesthetic delivery for RATS shares similarities with VATS, including induction, maintenance, and lung isolation. Postoperative analgesia for RATS resembles VATS protocols, with options including thoracic epidural analgesia, paravertebral blocks, and intercostal infiltration [

2,

3]. In this article we former review the trials conducted so far on the use of VivaSight™ in thoracic surgery, highlighting the differences between this device and cDLT and its main pros and cons; latter, we report our clinical experience about using VivaSight™ in RATS and propose some experience-based recommendations for optimal use of the device in this peculiar surgical setting.

2. The VivaSight™ ™ Endotracheal Tube

The VDLT is a sterile, single-use PVC tracheal tube equipped with two light-emitting diodes and a miniature Complementary Metal-Oxide Semiconductor (CMOS) video camera. The camera operates at a resolution of 320 × 240 CIF (76,800 pixels) and provides an 85° diagonal field of vision with a depth range of 12–60 mm. The cylindrical camera measures 3 mm in diameter and 16 mm in length. Its elliptical distal aperture accommodates the camera effectively. Two Murphy eyes are located on either side of the camera, enabling visualization of the laryngeal entrance and facilitating patient intubation. The imaging sensitivity is 0.7 V (lux × seconds). Power is delivered to the video camera and light source via a cable embedded within the tube wall, and images are transmitted to a 7-inch medical-grade LCD monitor. The monitor, measuring 5.4 × 7 cm, provides real-time, high-resolution video. Additionally, the image can be displayed on any standard video monitor, and the correct placement of the tube can be recorded. In cases of heavy secretions, mucus, or blood obscuring the view, the camera lens can be cleaned using 1–2 mL of liquid through the flushing system [

4].

3. VivaSight™ ™ ETT in Thoracic Surgery So Far: Review of the Literature

We conducted a literature search using the search terms “VivaSight™ double lumen tube thoracic surgery” in the search engines of PubMed (

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed), Google Scholar (

https://scholar.google.com), and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (

http://community.cochrane.org). We identified 13 articles written in English in PubMed, and again 13 articles in Google Scholar; on both providers, among these papers, 5 were scientific articles concerning comparison between VivaSight™ and standard DLT in thoracic surgery, 6 were papers evaluating the use VivaSight™ in the same surgical field, 1 was a cost-effectiveness study and 1 was a systematic review. We did not come across any related articles in Cochrane instead. The search consists of articles published up to 2025 to describe the use of VivaSight™ in thoracic surgery procedures (from 1945 to 2025). We screened ClinicalTrials.gov and EU Clinical Trials Register to identify relevant ongoing studies: on ClinicalTrials.gov there were 3 completed prospective randomized clinical trials, of which 1 was about comparing VDLT and cDLT and other 2 about evaluating the use of VivaSight™ in thoracic surgery. There also was a trial in recruiting phase about the cost-effectiveness of VivaSight™ utilization. No trials were found on the EU register. A review of the articles strictly concerning clinical use of the device mentioned above follows below.

Massot et al. [

5] conducted a mono-center study between September 2013 and April 2014 on 84 patients undergoing thoracic surgery procedures. The primary endpoint was the correct positioning of the tube assessed by FOB, positioning being defined by simultaneous presence of two criteria: bronchial cuff located in the left main bronchus and end of the bronchial channel upstream of the upper and lower lobe bifurcation. Seventy-six patients (99%) had correct positioning, with a median margin of safety of 20 mm (interquartile range: 15-27) in the surgical position. In 40 patients (53%), malpositioning required mobilization of the tube at least once intraoperatively. The tube was well positioned in almost all patients. The authors stated that continuous visualization of the carina is a major improvement for patient care as intraoperative displacement can be diagnosed immediately and corrected. However, an incident (overheating of the distal tip of DLT) induced premature ending of the study.

In a prospective multi center observational study, Koopman et al. [

6] reported the use of VivaSight™ in 151 consecutive patients scheduled for elective thoracic surgery in four different hospitals between December 2013 and September 2014. The authors decided to evaluate the use of the VDLT in clinical practice, and focused on endobronchial intubation characteristics, the quality of the camera view and whether additional FOB was required. Endobronchial intubation was successful in 148 patients (98%) (95% CI 94–99%). Median (IQR [range]) endobronchial intubation time was 59 (47–82 [17–932]) s and lung isolation was successfully achieved in 147 (99%) patients (95% CI 96–99%). A FOB was required to assist endobronchial tube placement in 19 (13%) patients (95% CI 8–19%). Sore throat was reported by 37 (25%) patients (95% CI 18–33%), but no major complications were observed.

Levy-Faber et al. [

7] recruited 71 adult patients for a prospective study, in which intubation times using either the VDLT or a cDLT were compared. Median (IQR[range]) duration of intubation with visual confirmation of tube position was significantly reduced using the VDLT compared with the conventional double-lumen tube (51 (42–60 [35–118]) s vs 264 (233–325 [160–490]) s, respectively, p < 0.0001). None of the patients allocated to the VDLT required FOB during intubation or surgery; more, the VivaSight™ was told to enable significantly more rapid intubation compared with the conventional double-lumen tube.

Schuepbach et al. [

8] enrolled 40 patients scheduled for thoracic surgery. Patients were randomized to cDLT (n= 20) or VDLT (n= 20). Time to intubation was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were insertion success without flexible bronchoscopy, frequency of tube displacement, ease of insertion, quality of lung collapse, postoperative complaints, and airway injuries. Results Time [mean (SD)] to successful intubation was significantly faster with the VDLT [63 (58) sec] compared with the cDLT [97 (84) sec; P= 0.03]. The VDLT was correctly inserted during all attempts. When malpositioning of the VDLT occurred, it was easily remedied, even in the lateral position. The devices were comparable with respect to postoperative coughing, hoarseness, and sore throat. Airway injuries tended to be more common with the VDLT, although this study was underpowered for airway injuries.

Rapchuk et al. [

9] captured data for a period of six months from September 2014 to April 2015 on 72 adult patients undergoing thoracic procedures requiring OLV with the VDLT. Lung separation was achieved on first attempt without additional manipulation in 85% of cases. In only three cases (4%) was a FOB required, in each instance to reposition the tube after intraoperative dislodgement. The main difficulty reported in the study was a deteriorating view through the VivaSight™ camera due to secretions. The authors found that pre-treating the device with anti-fog spray improved optimal visualization of the airways for a longer period.

Heir et al. [

10] recruited 80 patients undergoing thoracic surgery from September 2015 to December 2015 for a single center randomized controlled trial to compare the incidence of fiberoptic bronchoscope use during verification of initial placement and for reconfirmation of correct placement following repositioning, when either cDLT or VDLT was used for lung isolation during thoracic surgery. 42 patients were randomized to cDLT group, while 38 were randomized to the VDLT group. The overall use of FOB for placement/intubation was the same (VDLT 0% versus 0% in DLT), however, the use of FOB for verification/confirmation of final position of the tube {VDLT 13.2% (5/38) versus cDLT 100% (42/42), p-value<0.0001} differed. The median time from laryngoscopy to intubation was shorter in VDLT group (30 seconds) when compared with cDLT group (54.5 seconds, p <0.0001). Moreover, the time interval from final surgical position to ready for surgical intervention was significantly shorter in the VDLT group (median: 21 seconds) versus (median: 83 seconds p <0.0001) in the cDLT group. In vast majority of the cases in the VDLT group (37/38) both the intubation and final endobronchial position was easily accomplished and the embedded camera provided either a good view (86.8%) or adequate view (13.2%). As per the secretions, they were seen in 63.2% (24/38) in the VDLT group versus 33.3%(14/42) in the cDLT group (p=0.0076). Once detected, secretions were effectively cleared in the VDLT arm 91.3% of the time compared with 100% of the time in the cDLT group (p=0.5165). The method for clearance of secretions in the VDLT group was with either saline (57.1%) or air (42.9%). Although, the incidence of dislodgement was essentially the same in both groups (13 in VDLT group versus 14 in cDLT group), the need for FOB to correct the dislodgement was markedly different when comparing the two groups (VDLT 7.7% versus cDLT 100%, p=<0.0001). Moreover, in both groups dislodgement was noted to occur more frequently during positioning VDLT (61.5%) versus cDLT (64.3%) than during surgery VDLT (38.5%) versus cDLT (21.4%). Two patients in the cDLT group had dislodgment during both positioning and surgery. The anesthesiologist was able to forewarn more often in VDLT cases 18.4%(7/38) compared with 4.8%(2/42) in the cDLT cases (p =0.0113). A total of 10.1%(8/79) complained of postoperative sore throat (6 in cDLT, and 2 in VDLT) and this difference was not statistically different.

Onifade et al. [

11] performed a randomized controlled comparative study on 50 patients enrolled and randomly assigned to either a cDLT (n=25) or a VDLT (n=25). The primary outcome was the rate of FOB use. Secondary outcomes included time to correct tube placement and incidence of malposition during surgery. Use of the VDLT required significantly less FOB use (28%) compared to use of the cDLT (100%). While there was no difference in the ease of intubation, the time to correct tube placement was significantly faster using a VDLT (54 vs. 156 s, P<0.001). Additionally, the incidence of tube malposition was significantly reduced in the VDLT group. The study demonstrated a significantly lower rate of FOB use when using a VDLT compared to a cDLT. Placement of the VDLT was significantly quicker and malposition during surgery occurred significantly less than with the cDLT.

Granell et al. [

12] designed and conducted a retrospective analysis on 100 patients scheduled for lung resection over 21 consecutive months (January 2018-September 2019) to compare outcomes in patients undergoing thoracic surgery using the VDLT or the cDLT. The primary endpoint of the study was to analyze the need to use fiberoptic bronchoscopy to confirm the correct positioning of VDLT or the cDLT used for lung isolation. Secondary endpoints were respiratory parameters, admission to the intensive care unit, length of hospitalization, postoperative complications, readmission, and 30-day mortality rate. The main finding of the study is that patients undergoing lung resection intubated using the VDLT device showed a lower requirement of FOB to assess tube positioning during surgery as compared with patients intubated with the cDLT device (9 patients [18%] vs. 26 patients [52%), and this difference was statistically significant.

Palaczynski et al. [

13] enrolled 79 patients undergoing thoracic procedures for a randomized prospective study to test the hypothesis that intubation with the VDLT would be easier and faster than with a cDLT. No significant differences between number of intubation attempts were found among studied groups; first attempt success in VDLT group was noted at 90.6%, whereas in cDLT group 79.5%. On the other hand, the time required for tracheal intubation by using VDLT was significantly shorter than that for the standard cDLT technique (median: 44 vs. 125 s). The intubation time in the cDLT group included correct positioning of the tube as verified with the auscultation method and FOB in 3 cases (7.7%). In the VDLT group, FOB application for correct tube positioning was not reported; in the cDLT group, the incidence of FOB was reported in 8 (20.5%) cases overall. The incidence of tube dislocation in VDLT group was as high as 43.1% after patient repositioning and 3.1% intraoperatively, whereas in cDLT group 17.9% and 7.7% respectively. In conclusion, the use of VDLT when compared with cDLT offers reduced intubation time and is relatively easier. Also, the reduced need for FOB may improve the cost-effectiveness of VDLT application. In addition, constant visualization of the airways during the procedure allows to quickly correct or even prevent the tube malposition.

Tao et al. [

14] designed this study to evaluate the feasibility of VDLT intubation assisted by video laryngoscope in lateral decubitus patients. Patients undergoing elective video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) for lung lobectomy were assessed for eligibility between January 2022 and December, 2022. Eligible patients were randomly allocated into supine intubation group (group S) and lateral intubation group (group L) by a computer-generated table of random numbers. The prime objective was to observe whether the success rate of VDLT intubation in lateral position with the aid of video laryngoscope was not inferior to that in supine position. A total of 116 patients were assessed, and 88 eligible patients were randomly divided into group L (n¼ 44) and group S (n¼ 44). The success rate of the first attempt intubation in the L group was 90.5%, lower than that of S group (97.7%), but there was no statistical difference (p > 0.05). Patients in both groups were intubated with VDLT for no more than 2 attempts. The mean intubation time was 91.98 ± 26.70 s in L group, and 81.39 ± 34.35 s in S group (p > 0.05). The incidence of the capsular malposition in the group L was 4.8%, less than 36.4% of group S (p < 0.001). After 24 h of follow-up, it showed a higher incidence of sore throat in group S, compared to that in group L (p¼ 0.009). The study shows the comprehensive success rate of intubation in lateral decubitus position with VDLT assisted by video laryngoscope is not inferior to that in supine position, with less risk of intraoperative tube malposition and postoperative sore throat.

4. Our Experience: Materials and Methods

We performed a mono-center retrospective study on 31 consecutive patients who underwent RATS in the period between September 2024 to February 2025 (

Table 1).

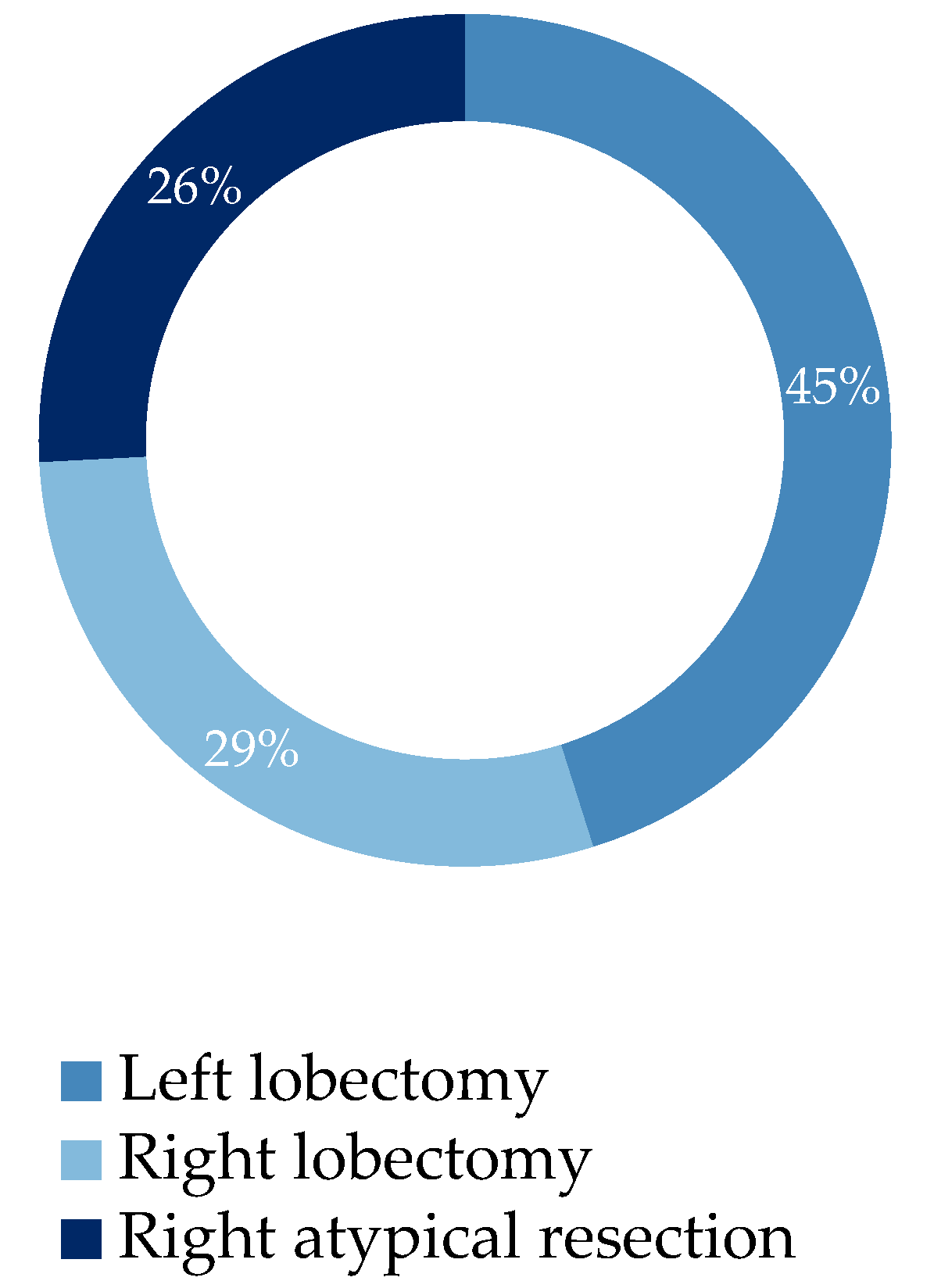

The study aims to detect more datas on the advantages of using VivaSight™ for airways management, and so the utility of this device in RATS procedures (which have peculiar settings and implications for the patients and anesthesiologists too) in order to propose some experience-based recommendations for optimal use of the VivaSight™ in this surgical setting. 74% of patients underwent lobectomy while 26% underwent atypical resection (

Figure 1). VivaSight™ ETT was used for airway management during these surgical procedures. In all patients a cannulation of two periferical veins was performed with a 16G cannula for both accesses; an 20G arterial cannula was also positioned for invasive perioperative monitoring of the blood pressure. All patients received premedication with midazolam 0.1 mg/kg e.v. and atropine 0,5 mg e.v. Anesthesia was inducted by administration of propofol 1 mg/kg e.v., fentanyl 200 mcg e.v., rocuronium 0,6 mg/kg; to maintain anesthesia, sevoflurane 2% via inhalation, fentanyl 1 mcg/kg e.v, MgSO4 4 mg e.v. (previous diluition in NaCl 0,9% 100 ml), rocuronium 10 mg e.v. were administered. We performed in every patient a paraverthebral periferical blockage before the surgical procedure and a blockage of the serratum before awakening, in order to obtain post-operative analgesia. During the surgery all patients were monitored with invasive blood pressure measurement, BiS monitoring for anesthesia depth (PSI, PVI, PI, HB) and hemodynamics monitoring with Hemosphere software (CI, SV, SVV, SVRI). We applied SilkoSpray® on the VivaSight™ ETT before intubation in 50% of the procedures. We also performed a continuous suction of the secretions during the intubation maneuver: that was possible by applying a suction device in the tracheal lumen of the VivaSight™. To remove secretions from the camera and the airways, we performed an airway washing with physiological saline through the dedicated lumen of the tube.

5. Results

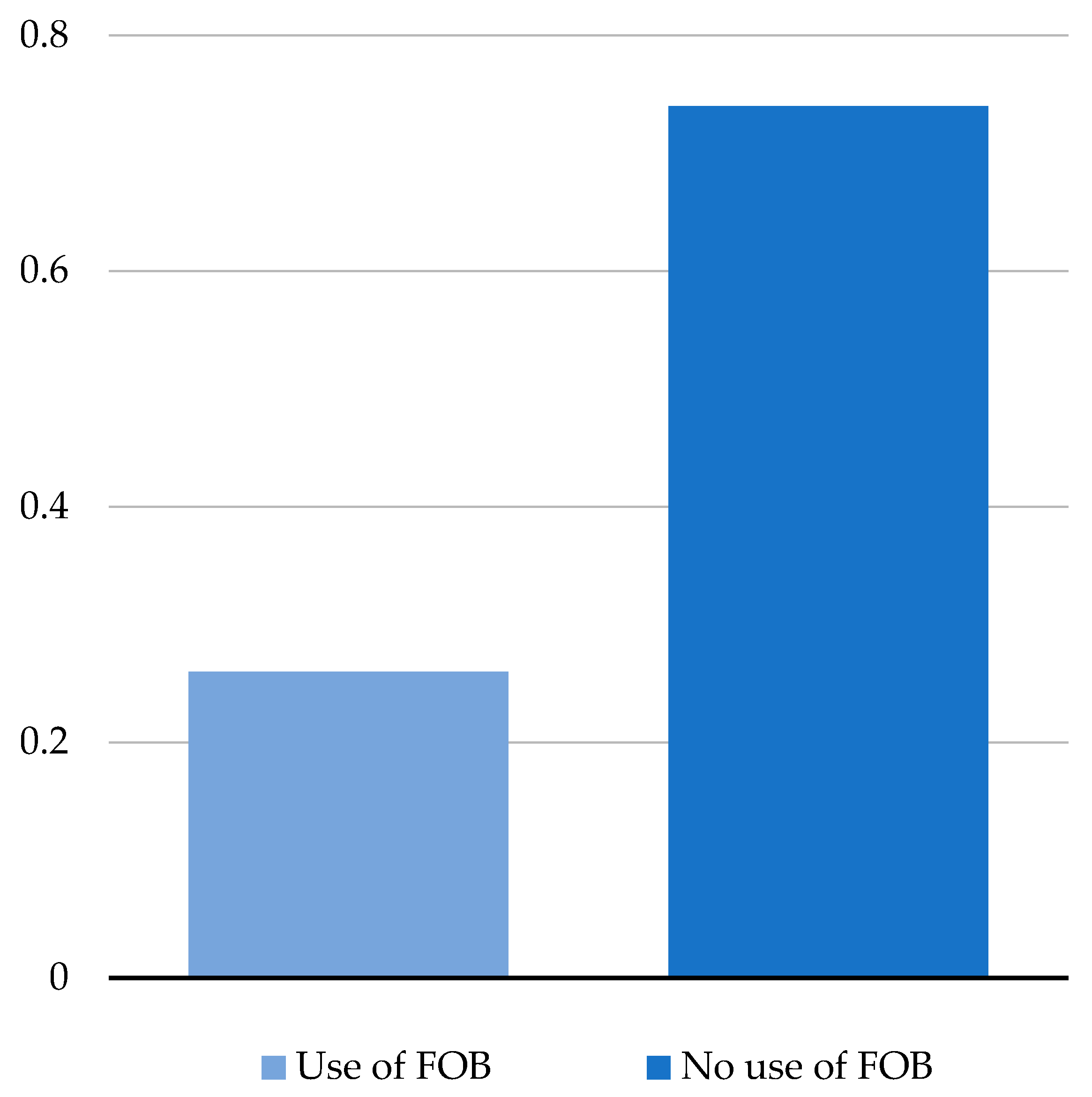

In 52% of patients, intubation was possible at first attempt without any issues, while in 48% of them fogging and coverage of the camera occurred, leading to perform a FOB (

Figure 2).

In 1 patient FOB was necessary due to direct right bronchus intubation without a correct visualization of the carina. Washing was not necessary in patients intubated with tubes on which SilkoSpray® had been applied previously. FOB was necessary when secretions were bulky and not removable with a standard suction device. Camera fogging was not preventable despite all the precautions mentioned above; therefore, wherever fogging occurred, FOB was necessary to check the correct insertion of the tube. No overheating of the device was detected. In 2 patients tube dislocated after repositioning but no hypoxemia occurred. 8% of the patients referred throat hoarseness in the postoperative period. In 1 case it was impossible to visualize the airways due to a bug in the monitor cable. All the patients survived after surgery.

6. Discussion

The relatively recent introduction of RATS has led to limited studies on the anesthetic and analgesic techniques used during these procedures. Anyway, some key differences compared to video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) and specific considerations for robotic surgeries have been identified. The bulkiness of robotic systems and the unique requirements of thoracic surgery—such as carbon dioxide insufflation, artificial pneumothorax, and prolonged one-lung ventilation (OLV)—are challenging for both surgical and anesthetic management. Difficult access to the patient’s head during surgery is probably the most challenging aspect for anesthesiologists during RATS, especially because it configures a “docked patient” setting which complicates tasks such as fiberoptic bronchoscopy and anyway any attempt of intervention in case of complications and emergencies. Monitoring fluid losses during RATS is also difficult due to the closed operating field. Intraoperative complications, such as robotic arm interference or unanticipated bleeding, may be harder to detect for the same reasons. Given these considerations, it is clear that an optimal monitoring of the patient, starting from airways management, is needed in this surgical setting. The VivaSight™ ETT might be a good choice for airways management in RATS if we consider the results obtained so far. First, using VivaSight™ ETT reduces the need of a control FOB after intubation [

5]. FOB is still the gold standard procedure for confirming correct intubation when cDLT (e.g., the Robert Shaw tube) are used. Correct tube placement is essential for optimal management of lung deflation on the surgical site and adequate oxygenation of the non-deflated lung. More data are needed to confirm the reduced necessity for control FOB particularly in cases with specific challenges (e.g., airway malformations, abnormal anatomy). Using VivaSight™ allows a faster detection of tube dislocation and therefore a faster intervention when complications occurr [

15], such as hypoxia, which is a critical concern in any surgical procedure, especially those requiring one-lung ventilation like thoracic surgeries. VivaSight™ enables faster intubation [

13], although further evidence is required due to the variability introduced by the anesthesiologist’s individual technique. Additionally, VivaSight™ could simplify intubation maneuvers in patients with limited cervical spine mobility, potentially expanding its use beyond elective surgery. Despite the slightly higher cost per unit compared to standard double-lumen tubes, VivaSight™ may ultimately prove more cost-effective [

16]. That, because its use significantly reduces the need for control FOBs and the associated costs of bronchoscope use. Data on rate of patient’s contamination during RATS are lacking. In theory, VivaSight™ could be safer in this regard, as it does not necessitate routine FOB use; infact, given the setting of a RATS operating room, in which the patient is docked once surgery begins, the insertion of even a sterile bronchoscope into the tube is a potential risk of introducing multidrug-resistant pathogens into the airways. The rate of soft tissue injuries during intubation using VivaSight™ compared to standard double-lumen tubes is unknown. The most commonly reported issues in literature include a higher incidence of symptoms such as throat dryness and hoarseness in patients intubated with VivaSight™ (similar to those observed in patients intubated with NIM-ETT) [

17]; overheating of the camera, and consequently of the tube, may potentially cause soft tissue damage in the airways [

5]. Secretions and exhaled air can cause fogging or even complete obstruction of the camera, thereby negating VivaSight™'s main advantage: continuous airway visualization. The most significant advantage of using the VivaSight™ tube during RATS is the continuous visualization of the airways (

Figure 3).

This allows for significantly faster detection of issues and complications. The most critical moment during patient preparation is the repositioning from supine to lateral position: this is the phase where the endotracheal tube is most prone to dislocation, potentially leading to ventilation loss, which is already a particular challenge as it involves single-lung ventilation. Detecting a dislocation of the tube visually before abnormal respiratory parameters come out, is less risky for the patient and offers greater protection against severe complications, particularly hypoxemia and cardiopulmonary collapse. The continuous visualization of the airways also allows a better organization of intervention timing and methods. This is especially relevant considering the setup of a robotic surgery operating room: given the spatial constraints imposed by the robot, the patient is docked and its head is not easily accessible. Identifying the problem earlier enables quicker action, preventing complications from progressing to a more severe stage. Although there is no specific data available on this aspect, VivaSight™ virtually eliminates the risk of contamination through the endotracheal tube. Surgery generally leads to immunosuppression, patients are immunocompromised, but patients who undergo thoracic robotic surgery are most of all oncological patients, who are already significantly immunosuppressed: therefore, eliminating the risk of contamination could translate into markedly improved outcomes for these patients. The main limitations of the VivaSight™ are tied to its design. First, camera fogging due to exhaled breath, blood, or secretions could make the intubation and the continuous visualization of the airways during surgery difficult too. Such an event would require the use of a suction device or even a fiberoptic bronchoscope, which, although sterile, could still serve as a contamination vector when used in a RATS setup. We recommend to give antimuscarinic drugs (such as atropine, scopolamine) to all patients who can receive these ones in premedication, in order to reduce airways secretions; then, we suggest to practice suction by integrating a suction device near the tube’s tracheal cuff during intubation, so to permit continuous suction and keep camera visibility throughout the procedure. Although this maneuver does not guarantee absolute sterility, it does prevent the introduction of a potential contamination vector at a later stage, when the patient, weakened by surgical and pharmacological stress, is more immunologically vulnerable. The incorporation of a camera in the trachea cuff of the tube could lead to an overheating of the device and therefore to an increased incidence of soft tissue damage, as well as postoperative dryness of the mouth and hoarseness. Current protocols do not recommend applying any agents to the tube before insertion; however, we suggest the use of a dimethicone spray (Rusch SilkoSpray®), due to its anti-friction properties and its potential to mitigate these side effects. The overheating of the camera and consequently the tube, particularly in its distal part, is a reported issue, especially in the study conducted by Massot et al [

5]. An investigation by the manufacturer followed but did not lead to significant changes. Agreeing with authors who have identified this issue, we recommend checking tube’s temperature for a few seconds before the insertion. When possible, it would also be useful to apply a contact thermometer on the tube to monitor its temperature. Another consideration concerns the intubation itself: the VivaSight™ has a particular curvature and is not very flexible due to the camera embedded within it, so adapting the shape of the device for the intubation could be challenging. Laryngoscopy remains essential for the intubation, and no protocol has been described that allows intubation using the VivaSight™ tube alone. The use of GlideScope® or videolaryngoscopes to assist with double-lumen tube placement is now widespread, while the Macintosh laryngoscope has gradually fallen out of favor for thoracic surgery intubations. Given that, we suggest, agreeing with other authors, to use videolaryngoscopes for airway visualization during intubation. The videolaryngoscope is space-efficient and allows for better tube maneuverability. In cases of unexpected difficult airways, a stylet can be used with the VivaSight™ tube. Last but not least: the size of the tube, according to other authors, should be one size smaller than standard double lumen tubes [

12]. Recently Ambu® has received complaints regarding the design of the product Ambu® VivaSight™ 2 DLT, specifically referring to a hyper angulation of the distal end of the double lumen tube. This hyper angulation can lead to an increased risk of complications during intubation and potential airway injury. A root cause investigation has indicated that the hyper angulation deviation is linked to a manufacturing issue that occurred during a specific timeframe in the production of the product. The findings furthermore estimate that only a small fraction of the products on the market are impacted by this issue. Thus, the majority of Ambu® VivaSight™ 2 DLTs available are not affected by this deviation. Following the investigation, Ambu® has implemented a correction in the manufacturing process to resolve the issue. For this reason too, we suggest to use a stylet and a videolaryngoscope for the intubation for an optimal visualization of the airways during this procedure, in order to prevent any soft tissue injuries.

7. Conclusions

Using the VivaSight™ ETT in RATS allows continuous airway visualization during intubation, repositioning of the patient and the whole duration of the surgery. That reduces the need for a control FOB anytime there is a variation in the setting of the procedure. A reduced need for FOB might lead to a reduced risk of contamination of the docked patients and therefore to a better outcome in the postoperative period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C., R.F., F.C. and F.F.; methodology, F.C. and M.C.; data curation, M.C., F.M.P. and F.F; writing—original draft preparation, M.C. and F.M.P.; writing—review and editing, R.F. and R.P.; supervision, C.P. and V.P.; all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge dr. Giammaria Vocca for proof-reading and editing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RATS |

Robot-Assisted Thoracic Surgery |

| VDLT |

VivaSight Double Lumen Tube |

| cDLT |

Conventional Double Lumen Tube |

| ETT |

EndoTracheal Tube |

| FOB |

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy |

| OLV |

One-Lung Ventilation |

References

- Bernasconi, F.; Piccioni, F. One-lung ventilation for thoracic surgery: current perspectives. Tumori. 2017, 103, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonsette K, Tuna T, Szegedi LL. Anesthesia for robotic thoracic surgery. Saudi J Anaesth. 2021, 15, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCall, P.; Steven, M.; Shelley, B. Anaesthesia for video-assisted and robotic thoracic surgery. BJA Educ. 2019, 19, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saracoglu, A.; Saracoglu, K.T. VivaSight™: a new era in the evolution of tracheal tubes. J Clin Anesth. 2016, 33, 442–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massot, J.; Dumand-Nizard, V.; Fischler, M.; Le Guen, M. Evaluation of the Double-Lumen Tube VivaSight™-DL (DLT-ETView): A Prospective Single-Center Study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2015, 29, 1544–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopman, E.M.; Barak, M.; Weber, E.; Valk, M.J.; de Schepper, R.T.; Bouwman, R.A.; Huitink, J.M. Evaluation of a new double-lumen endobronchial tube with an integrated camera (VivaSight-DL(™) ): a prospective multicentre observational study. Anaesthesia. 2015, 70, 962–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy-Faber, D.; Malyanker, Y.; Nir, R.R.; Best, L.A.; Barak, M. Comparison of VivaSight™ double-lumen tube with a conventional double-lumen tube in adult patients undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Anaesthesia. 2015, 70, 1259–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuepbach, R.; Grande, B.; Camen, G.; Schmidt, A.R.; Fischer, H.; Sessler, D.I.; Seifert, B.; Spahn, D.R.; Ruetzler, K. Intubation with VivaSight™ or conventional left-sided double-lumen tubes: a randomized trial. Can J Anaesth. 2015, 62, 762–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapchuk, I.L.; Kunju, S.; Smith, I.J.; Faulke, D.J. A six-month evaluation of the VivaSight™™ video double-lumen endotracheal tube after introduction into thoracic anaesthetic practice at a single institution. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2017, 45, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heir, J.S.; Guo, S.L.; Purugganan, R.; Jackson, T.A.; Sekhon, A.K.; Mirza, K.; Lasala, J.; Feng, L.; Cata, J.P. A Randomized Controlled Study of the Use of Video Double-Lumen Endobronchial Tubes Versus Double-Lumen Endobronchial Tubes in Thoracic Surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018, 32, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onifade, A.; Lemon-Riggs, D.; Smith, A.; Pak, T.; Pruszynski, J.; Reznik, S.; Moon, T.S. Comparing the rate of fiberoptic bronchoscopy use with a video double lumen tube versus a conventional double lumen tube-a randomized controlled trial. J Thorac Dis. 2020, 12, 6533–6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granell, M.; Petrini, G.; Kot, P.; Murcia, M.; Morales, J.; Guijarro, R.; de Andrés, J.A. Intubation with VivaSight™ double-lumen tube versus conventional double-lumen tube in adult patients undergoing lung resection: A retrospective analysis. Ann Card Anaesth. 2022, 25, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palaczynski, P.; Misiolek, H.; Bialka, S.; Owczarek, A.J.; Gola, W.; Szarpak, Ł.; Smereka, J. A randomized comparison between the VivaSight™ double-lumen tube and standard double-lumen tube intubation in thoracic surgery patients. J Thorac Dis. 2022, 14, 3903–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, D.; Zhang, G.; Zheng, X.; Wang, X.; Gao, G.; Yang, Z.; Lin, Y.; Lu, L. Feasibility study of intubation in lateral position using Viva-sight double-lumen tube combined with video laryngoscope in patients undergoing pulmonary lobectomy. Asian J Surg. 2024, 47, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.; Li, Y.; Guo, J.; Hu, R. Effect of the VivaSight™ double-lumen tube on the incidence of hypoxaemia during one-lung ventilation in patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery: a study protocol for a prospective randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2023, 13, e068071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, S.; Holm, J.H.; Sauer, T.N.; Andersen, C. A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Comparing the VivaSight™ Double-Lumen Tube and a Conventional Double-Lumen Tube in Adult Patients Undergoing Thoracic Surgery Involving One-Lung Ventilation. Pharmacoecon Open. 2020, 4, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salib, A.; Melero Pardo, A.L.; Lerner, M.Z. Soft tissue injury events associated with neural integrity monitoring endotracheal tubes: A MAUDE database analysis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2024, 45, 104233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).