1. Introduction

Gait analysis is a fundamental sensing modality in both clinical and research settings. Its applications include early detection of diseases, differentiating conditions that present with similar gait patterns, and leveraging quantitative gait metrics to anticipate future functional or clinical outcomes. Beyond diagnostic utility, gait analysis provides critical insights into the progression and severity of disorders affecting locomotion, as well as the efficacy of therapeutic interventions [

1,

2,

3] . Neurological disorders, such as spinal cord injury (SCI), stroke, Parkinson’s disease, dementia, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, cerebral palsy, cerebellar ataxia, peripheral neuropathy, and muscular dystrophy, frequently result in impairments in gait and balance, leading to reduced mobility, increased fall risk, loss of functional independence, and diminished quality of life [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Understanding and quantifying gait abnormalities is therefore essential not only for clinical assessment and treatment planning but also for developing targeted rehabilitation strategies aimed at preserving mobility and improving overall patient outcomes.

Gait analysis can be conducted using a range of methodologies, each targeting different aspects of locomotor function. One major category uses electrical neural signals, leveraging muscular activity transmitted from the brain and spinal cord to the periphery. Invasive approaches, including nerve recordings [

9,

10,

11] and intramuscular electromyography (iEMG) [

12,

13,

14], provide high-fidelity information but limited by surgical complexity and long-term stability. Non-invasive surface EMG offers a more practical alternative for routine assessment, but with reduced spatial specificity and susceptibility to motion artifacts [

15,

16]. A second major techniques involve wearable sensors, such as goniometers and inertial measurement units (IMUs), which directly measure joint or segmental motion [

1,

17,

18,

19,

20]. However, these device-based approaches require direct attachment to the body, which can restrict natural movement, reduce user comfort, and demand a continuous power supply, limitations that make wearable sensor–based tracking particularly difficult to implement in small-animal models.

To address these limitations of body-mounted sensors, optical motion-capture systems have been widely adopted for gait analysis. Traditional marker-based systems employ reflective markers tracked by multiple cameras to reconstruct three-dimensional kinematics with high precision. Despite their effectiveness, this approach is susceptible to marker detachment, which compromises measurement accuracy, and it remains difficult to capture fine movements in anatomically small regions such as the toes or fingers during dexterous movement. These limitations have motivated the development of markerless, deep-learning–based gait analysis methods, eliminating the need for physical markers while providing robust motion estimation across a wide range of movement conditions [

21,

22,

23].

As gait sensing technologies advance, gait analysis is being increasingly used to guide therapeutic strategies, including gait-phase-dependent neuromodulation [

24,

25]. Restoration of locomotor function through open-loop stimulation poses inherent limitations, as externally delivered stimulation can interfere with natural ascending and descending neural signaling [

26]. In contrast, closed-loop stimulation synchronized to gait phase has gained significant attention [

14,

27,

28]. However, the development of reliable real-time gait-phase detection algorithms traditionally requires substantial computational resources and domain expertise. Recent advances in artificial intelligence now offer new opportunities to automate gait phase analysis and enable low-latency, adaptive closed-loop control [

13].

In this study, we present an AI-driven closed-loop neuromodulation system by analyzing gait patterns in sham and spinal cord–injured (SCI) mice. Using experimentally collected gait data, we constructed both a deep learning-based vision AI model and an on-device edge AI model. The vision AI system extracted gait parameters from video data on a PC, and the edge AI system processed these outputs to classify swing and stance phases in real time, enabling the generation of appropriately timed neural stimulation patterns. The integrated system was evaluated within a benchtop environment simulating actual real-time conditions. In the following sections, we present the gait characteristics of sham and SCI mice and describe the development and performance of the proposed vision AI and edge AI systems.

2. Materials and Methods

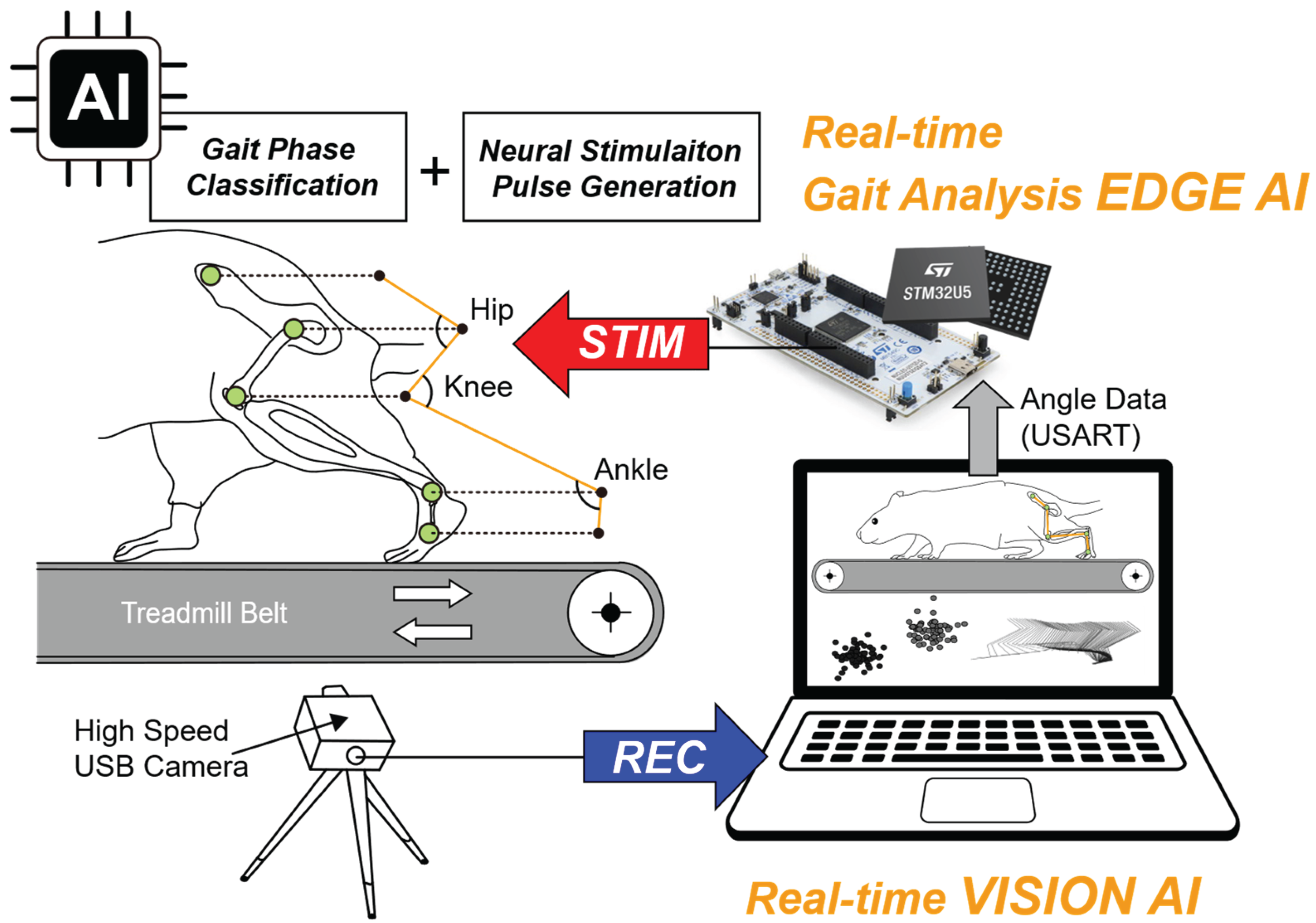

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of the proposed system for real-time, AI-based gait phase analysis for closed-loop neuromodulation. Recorded video of a walking mouse on a motorized treadmill is processed by a hybrid AI architecture comprising vision AI and edge AI. The vision AI model extracts predefined anatomical landmarks from joint angles, which are then transmitted to the edge AI model. The edge AI model classifies gait phases and generates triggering pulses for precisely timed biphasic neural stimulation.

2.1. Treadmill Gait Analysis in Intact and SCI Mice

2.1.1. Animal Preparation

To assess gait patterns, treadmill locomotion was recorded and analyzed in sham (n = 3) and SCI (n = 3) mice. Mice were housed under controlled temperature and a 12-hour light/dark cycle, with ad libitum access to food and water, at the Indiana University School of Medicine animal facilities. Data were analyzed in a blinded fashion, and group identities were decoded only after analysis was completed. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Indiana University School of Medicine.

2.1.2. Animal Surgery

Complete unilateral hemisection at the cervical level 4 (C4-CH), mimicking clinical Brown-Séquard syndrome, was performed using established methods with minor modifications [

29]. Mice were anesthetized with a ketamine–xylazine cocktail and a spine stabilizer was used to minimize spinal movement and ensure a left-sided lesion [

30]. Following a 1-cm midline incision and ligament removal, the spinal cord at the C3–C4 vertebral level was exposed. A midline dural puncture was created using a 30 G × ½” needle (0.3 mm × 13 mm), followed by lateral cutting with superfine iridectomy scissors. To protect the contralateral cord, a grooved 30 G × ½” needle was inserted at the midline, and the left cord was transected along the needle using modified, blade (width: 1 mm, 10050-00, FST), ensuring complete axonal transection. Contrary to the SCI group, the three mice in the sham group underwent the same surgical procedure except for the spinal cord transection.

2.1.3. Video Recording of Treadmill Walking

Mice were acclimated to a motorized treadmill (LE8700RTSTH, Panlab, USA) for 3 days and trained to walk while gradually increasing the belt speed from 0 to 15 cm/s. Five anatomical landmarks—the metatarsophalangeal joint (MTP), ankle, knee, hip, and iliac crest—are shown in

Figure 1 with green dots and were marked. These points were selected based on previous locomotion research [

12,

31,

32]. For the landmarks marking, oil-based paint markers (Sharpie, Atlanta, GA, USA) were applied to ensure accurate labeling for the deep-learning–based pose estimation software, DeepLabCut [

21], which was used for subsequent kinematic analysis.

Each landmark was marked with a 2–3 mm circular dot. White paint was used for all landmarks except the MTP, which was marked in red. These contrasting colors were chosen to maximize visibility against the animal’s fur, and red was specifically used for the MTP because it contacts the treadmill belt, which is white, ensuring sufficient contrast when the foot touches the surface.

Mouse treadmill walking was recorded for 3 minutes per mouse using a high-speed, high-resolution color camera (Basler a2A1920-160ucPRO, Germany) positioned on the left side of the sagittal plane. Video sequences were captured at 156 frames per second (FPS) with a resolution of 1920 × 592 pixels using commercial multi-camera software (StreamPix 9, NorPix, Canada). A custom checkerboard-patterned calibration cube was used to convert pixel coordinates into millimeter-scale measurements, providing accurate spatial calibration for the subsequent kinematic analysis. For data processing, the 3-minute recordings were clipped and edited in Adobe Premiere Pro 2025.

2.1.4. Kinematics Analysis

A DeepLabCut network model was customized and trained to track five key anatomical landmarks of the hindlimb: the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, ankle, knee, hip, and iliac crest. A total of 300 frames were labeled with the five anatomical landmarks. The network was trained using a ResNet-50 backbone architecture with maximum of 300,000 iterations. By using the trained DeepLabCut model, the x- and y-coordinates of the anatomical landmarks were extracted from the recorded videos, along with their associated likelihood values. These coordinates were processed using custom Python scripts (Python 3.13.5, NumPy 2.2.6, SciPy 1.16.0) and MATLAB R2025 for quantitative kinematic analysis, including spatiotemporal gait parameters. Computed parameters included joint angle range of motion (ROM), maximum and minimum joint angles, gait cycle duration, stance and swing durations, stance duty factor, normalized joint angles, and stick diagram representations of hindlimb movements.

Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired Welch’s t-test in GraphPad Prism 10.6.1. Data for sham and SCI groups are presented as mean values with ±SD. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks in the graphs: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

2.2. Bench-Top Test of Vision AI and Edge AI for Closed-Loop Neuromodulation

2.2.1. Vision AI–Based Real-Time Extraction of Hindlimb Joint Angles

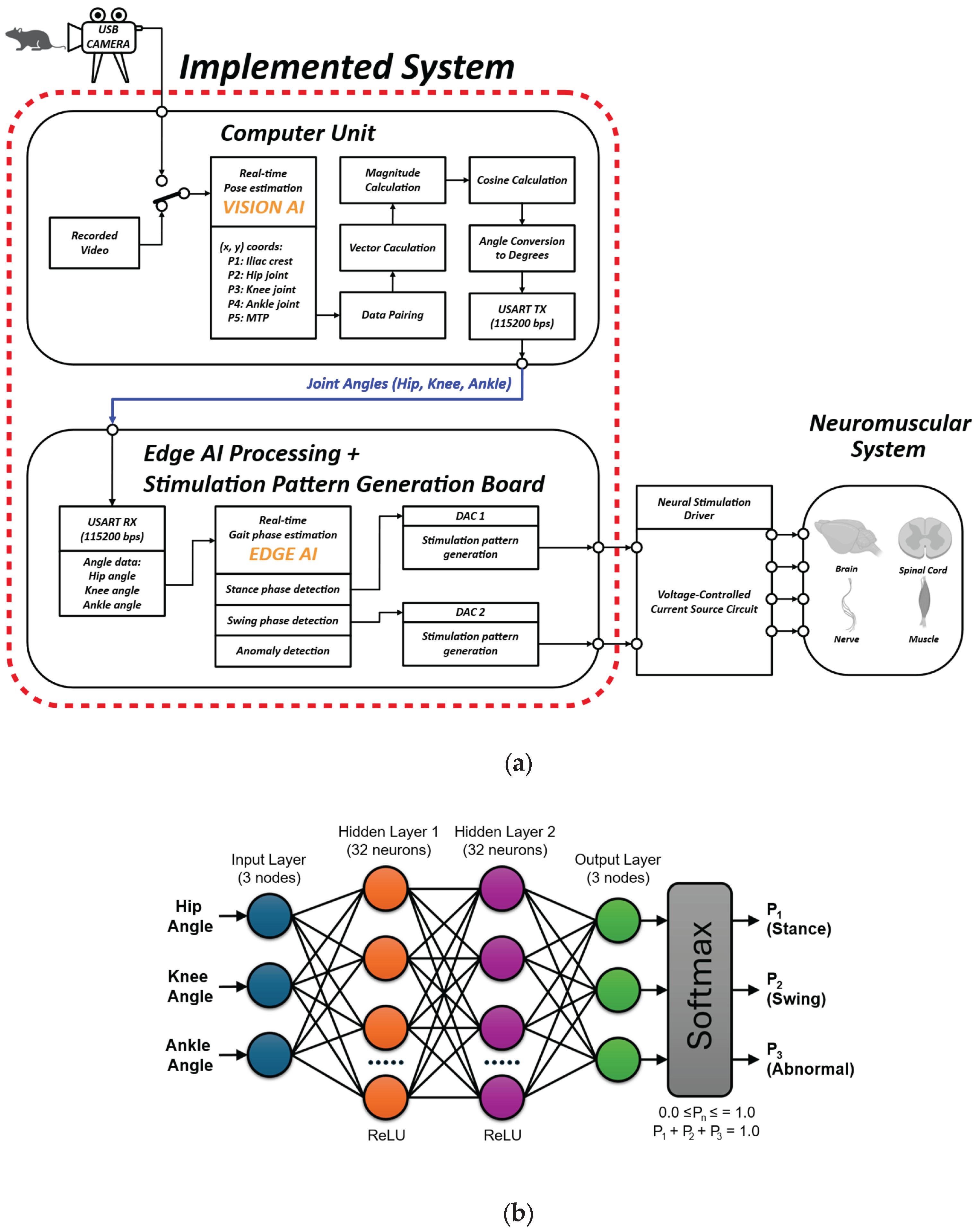

As shown in

Figure 2a, real-time gait analysis was conducted using a computer unit that processed recorded video. A vision AI model was extracted from the trained DeepLabCut network described in

Section 2.1.4. Then, vision AI model was integrated into Bonsai 2.9.0, a visual reactive programming GUI-based tool, as described in previous research [

33]. In this real-time processing environment, the x–y coordinates of five key anatomical landmarks—the iliac crest (P1), hip joint (P2), knee joint (P3), ankle joint (P4), and metatarsophalangeal joint (MTP, P5)-were continuously extracted. These coordinates were paired to form vectors, from which joint angles were calculated using vector-based cosine methods. The resulting angles were converted to degrees and transmitted via USART (115200 bps) for downstream processing.

2.2.2. Edge AI Model Design and Deployment on Microcontroller

Based on the preprocessed joint angles delivered from the PC via USART, real-time gait phase analysis and the generation of gait phase-dependent biphasic stimulation patterns for closed-loop neuromodulation were performed using a NUCLEO-U575ZI-Q development board, which integrates the STM32U575ZI ARM Cortex-M33 microcontroller [

34]. The edge AI model developed in this study was deployed on this microcontroller. For the edge AI model development, Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), a feed-forward neural network with two fully connected hidden layers (32 units each, ReLU activation) and a 3-unit softmax output layer were implemented (

Figure 2b). The model, comprising 1,283 trainable parameters. The input training data were developed from joint-angle measurements extracted from five mice (sham, n = 3; SCI, n = 2) as described in

Section 2.2.1. Input features were used in raw form without normalization to maintain compatibility with embedded deployment. The labels were encoded as integers representing the three gait phases: 0 for swing, 1 for stance, and 2 for abnormal. The data were randomly shuffled and split into 80% for training and 20% for validation. The dataset consisted of time-synchronized joint-angle measurements labeled as swing, stance, or abnormal, forming a three-class classification problem. The model was trained for up to 300 epochs using the Adam optimizer (batch size = 128), with early stopping and checkpointing enabled to prevent overfitting. The trained edge AI model was evaluated and deployed on the microcontroller using STM32Cube.AI 7.3.0. One SCI recording was not used for edge AI model training and was reserved to evaluate the complete system.

2.2.3. Gait Phase Monitoring and Phase-Dependent Neural Stimulation

To enable real-time system-level monitoring of gait phases derived from edge AI classification outputs, two general purpose input/output (GPIO) pins of the STM32U575ZI ARM Cortex-M33 microcontroller were configured as digital test ports. These pins were programmed to go HIGH when the corresponding phase was detected and LOW otherwise, with one pin serving as a swing phase indicator and the other as a stance phase indicator.

In addition to gait-phase monitoring, the developed system in this study is designed to generate neural stimulation patterns with precise control of stimulation parameters, including intensity, which can be adjusted across 4,096 discrete levels. Two integrated 12-bit digital-to-analog converter (DAC) channels of the microcontroller were assigned for the generation of phase-specific stimulation patterns, with DAC1 outputting stimulation pulses upon detection of the swing phase and DAC2 upon detection of the stance phase. Regarding the polarity of the generated stimulation pulses, symmetrical biphasic pulses were implemented to reduce potential damage at the neural interface by limiting residual charge accumulation [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Each pulse consisted of a negative phase followed by a positive phase, each lasting 200 μs, and was delivered at a frequency of 100 Hz, enabling safe and controlled neuromodulation [

9,

12,

14]. The stimulation onset, duration, and amplitude are programmable, allowing flexible modulation of neuromuscular activation. The two GPIO ports, representing the swing and stance phases, and the stimulation pulses generated by DAC1 and DAC2 channels were measured in synchronization using a 4-channel oscilloscope (TBS2204B, Tektronix, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Gait Characteristics Assessed on a Treadmill in Sham and SCI Mice

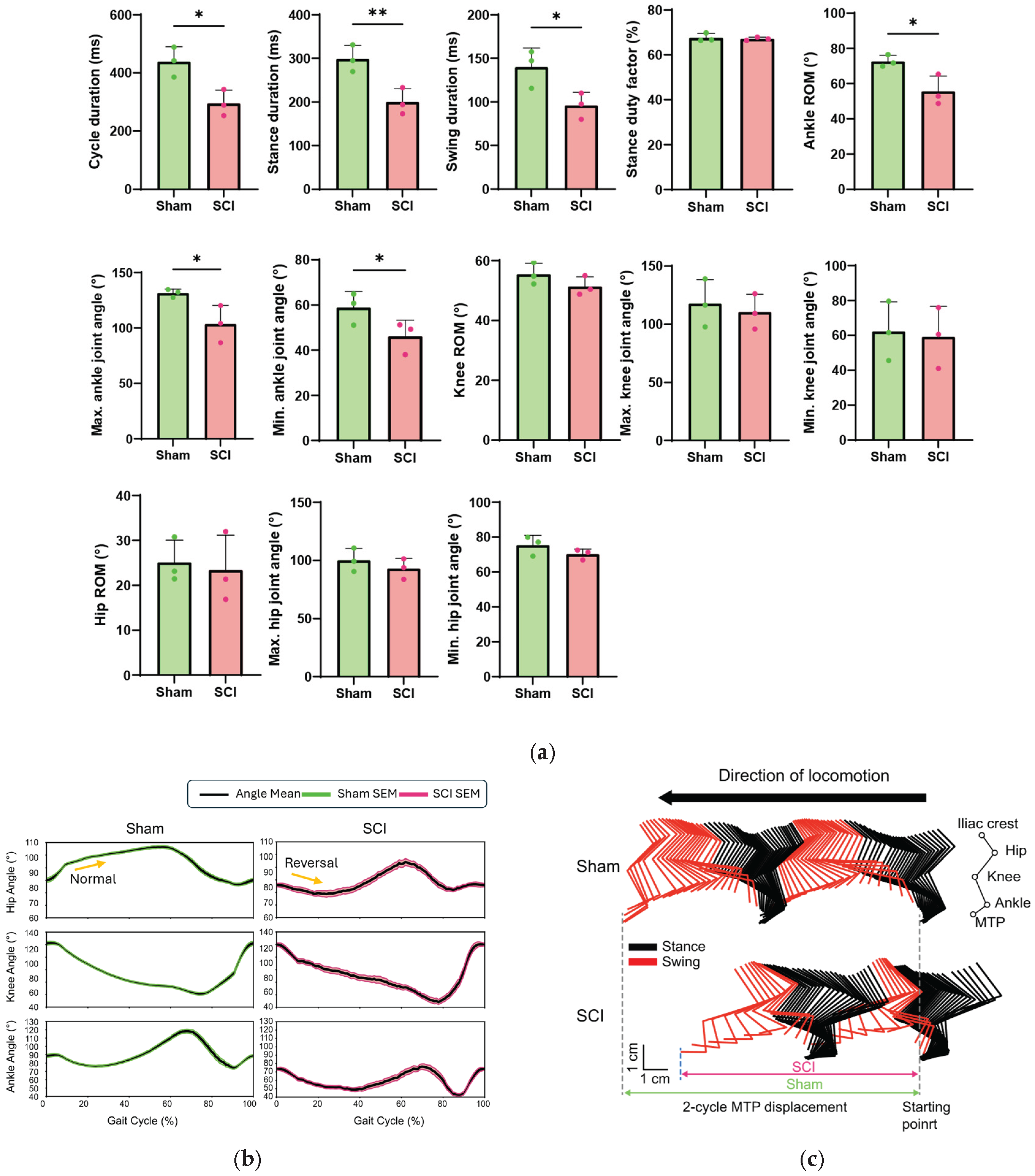

Figure 3 presents spatiotemporal locomotion parameters comparing sham and SCI mice. Temporal parameters, including cycle, stance, and swing duration, are detailed in

Section 3.1.1. Kinematic parameters, including range of motion (ROM) and angular excursions of the ankle, knee, and hip joints, are described in

Section 3.1.2.

Section 3.1.3 displays normalized gait cycles and representative stick diagrams from one sham and one SCI mouse.

3.1.1. Temporal Gait Alterations in SCI Mice

As shown in the first three panels from the top left of

Figure 3a, temporal parameters were significantly altered in SCI mice compared to sham controls. Notably, stance duration was markedly reduced by 33% in SCI mice, with a mean ± SD of 200.15 ± 30.50 ms compared to 298.72 ± 30.76 ms in sham mice, which was statistically significant (p = 0.0085). Cycle duration was similarly reduced by 33%, with SCI mice showing 295.36 ± 45.34 ms versus 438.87 ± 51.62 ms in sham mice (p = 0.0115), and swing duration decreased by 32%, with 95.95 ± 15.09 ms in SCI mice compared to 140.14 ± 21.83 ms in sham mice (p = 0.0258). Interestingly, despite these significant reductions in temporal parameters, the stance duty factor remained unchanged between groups, with 67.66 ± 1.89% for SCI mice and 67.14 ± 0.76% for sham mice (p = 0.3474).

3.1.2. Kinematic Gait Alterations in a Representative Sham and SCI Mouse

Figure 3b shows the changes in hip, knee, and ankle joint angles over a normalized gait cycle (0–100%) for one sham mouse and one SCI mouse, illustrating gait-phase–dependent trajectories and highlighting deviations caused by spinal cord injury. Across all joints (hip, knee, and ankle), the kinematic profiles of a sham mouse closely matched previously reported gait patterns in intact rodents [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43], confirming the validity of our measurement approach. The ankle joint showed characteristic patterns throughout the gait cycle, with the maximum angle at the end of stance during peak plantarflexion before toe-off, and the minimum angle at mid-swing during maximal dorsiflexion as the limb advanced forward. The hip and knee joints also displayed typical gait-phase-dependent trajectories: in sham mice, the hip angle increased during early stance before decreasing, whereas the knee angle decreased initially and then rose [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Building on this baseline, the representative SCI mouse exhibited clear deviations, most prominently in the ankle. The SCI mouse exhibited substantially reduced ankle angles (stance onset: 73.67°, maximum: 76.42°, minimum: 42.32°) compared with sham animals (stance onset: 88.48°, maximum: 118.30°, minimum: 74.37°), consistent with previously described patterns in injured rodent models [

44]. Although ROM and peak angles of the hip and knee were largely unchanged, normalized gait-cycle trajectories revealed altered across all joints.

Notably, the SCI mouse lacked the early-stance hip elevation observed in the sham mouse; instead, the hip angle initially decreased, representing a reversal of the normal trajectory, as indicated by the yellow arrow in

Figure 3b. Similar trajectory deviations occurred in the knee and ankle, indicating disrupted inter-joint coordination.

These findings suggest that while some locomotor functions are preserved after unilateral cervical SCI [

32], the restoration of coordinated ankle movement remains incomplete. Although temporal gait analysis revealed numerous significant differences, kinematic analysis showed minimal changes, except for the ankle angle. These observations are consistent with previous studies reporting rapid recovery of hindlimb locomotor function following cervical-level spinal cord hemisection. While forelimb function remained persistently impaired with minimal weight support, rats with C4 hemisection exhibited substantial hindlimb recovery, ultimately regaining mobility [

28].

3.1.3. Inter-Joint Coordination Alterations in SCI Mice

Stick diagrams were generated by connecting skeletal landmarks (iliac crest, hip, knee, ankle, and MTP) with line segments over two consecutive gait cycles, with stance phases shown in black and swing phases in red (

Figure 3c). As reported in previous studies [

45,

46,

47], sham mouse displayed typical gait patterns with well-coordinated limb trajectories. During stance, the limb maintained an extended posture with progressive ankle plantarflexion at toe-off, while during swing, coordinated flexion occurred at all joints, achieving maximum ankle dorsiflexion at mid-swing for ground clearance. The overall trajectory envelope formed a smooth, vertically oriented pattern, reflecting efficient forward progression. These patterns were consistent with the joint angles and normalized gait cycle peak values shown in

Figure 3a,b, demonstrating reliable inter-joint coordination.

In contrast, the SCI mouse exhibited altered limb configurations throughout the gait cycle. The ankle angle was reduced during swing, particularly at swing onset, consistent with the significantly decreased maximum joint angles and swing onset peak values observed in the normalized gait cycle (

Figure 3a,b). The hip was positioned more posteriorly, likely related to the reversed hip trajectory identified in

Section 3.1.2. In addition, stride length was markedly shorter in the SCI mouse compared to the sham mouse. Together, these data indicate that SCI fundamentally reorganizes spatial coordination rather than merely reducing joint excursions, with stick diagrams visually corroborating the disrupted inter-joint coordination quantified in the kinematic analysis.

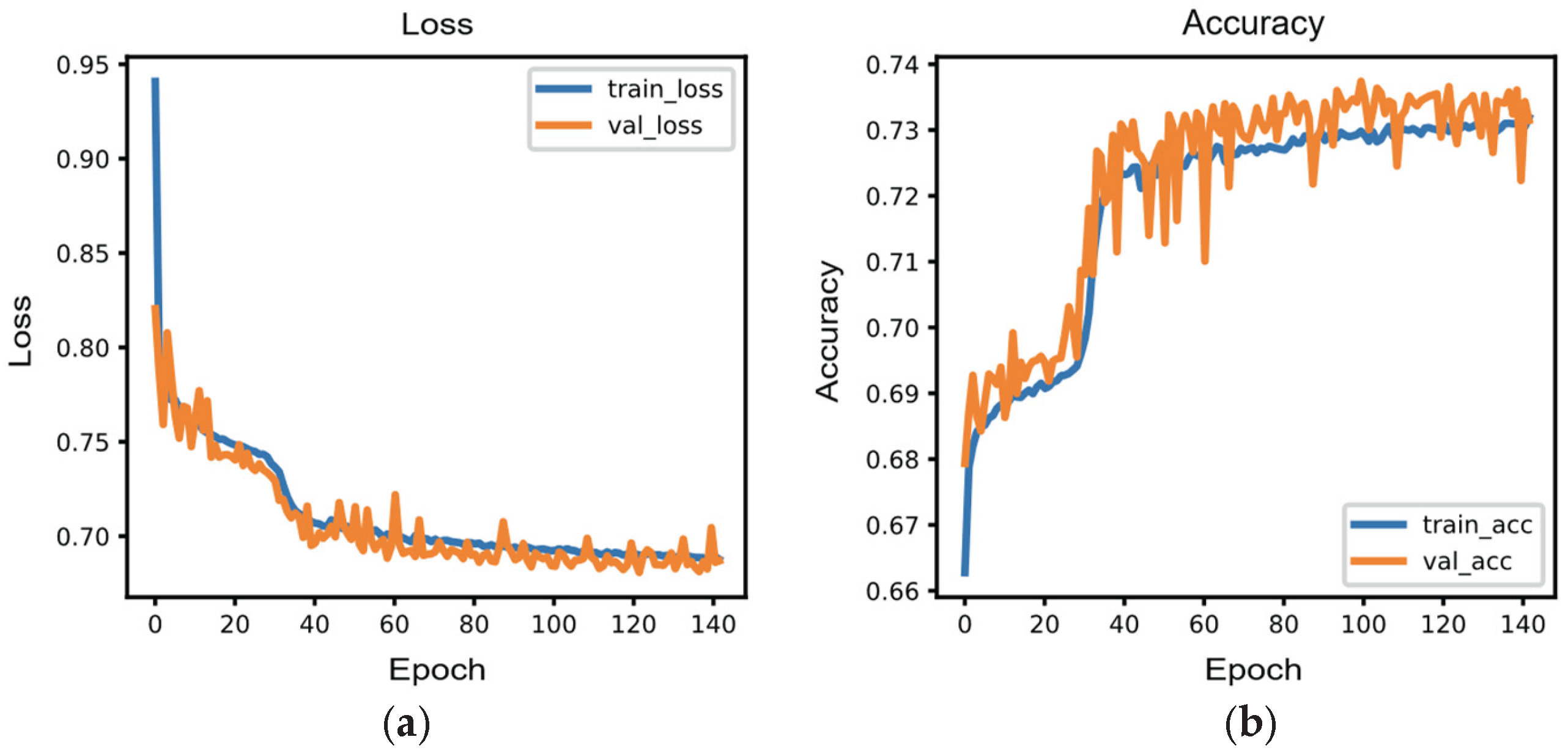

3.2. Edge AI Model Training Performance

Training terminated at epoch 141, corresponding to 47% of the maximum 300-epoch budget, indicating efficient convergence. The model exhibited smooth learning dynamics, with training and validation losses decreasing from 0.941 and 0.820 to 0.688 and 0.687, respectively (

Figure 4a). Final training and validation accuracies reached 73.2% and 73.1%, demonstrating minimal overfitting with only a 0.1 percentage point difference (

Figure 4b). Performance improvements were most pronounced during the initial 30 epochs, where validation accuracy increased from 67.9% to 70.8%. Following this learning phase, the model continued gradual refinement, with validation accuracy stabilizing around 73% after epoch 80. The peak validation accuracy of 73.7% was achieved at epoch 99, after which the model maintained consistent performance until early stopping was triggered at epoch 141. The near-identical final loss values between training (0.688) and validation (0.687) sets, combined with the minimal accuracy gap, confirm excellent generalization capability. The trained model was exported in HDF5 format with a file size of 47 KB (1,283 trainable parameters), demonstrating compactness suitable for edge deployment. These results indicate that the lightweight MLP-based edge AI model achieved robust predictive performance for three-class gait phase classification (swing, stance, and abnormal) while maintaining computational efficiency appropriate for real-time inference on resource-constrained platforms, potentially including microcontrollers with battery-operated implantable and wearable devices.

3.3. Bench-Top Evaluation of the Integrated Vision-Edge AI System

Recorded video from a single SCI mouse, which was not included in the vision AI and edge AI model training set, was used for integrated system evaluation. Hip, knee, and ankle joint angles were extracted in real-time and formatted for transmission to the edge AI model deployed on the microcontroller. The inference time of the edge AI model on the STM32U5 microcontroller was measured at 80 µs per classification, demonstrating its capability for real-time gait phase detection with minimal latency.

Figure 5 presents the output of the fully integrated vision-edge AI pipeline, illustrating the measured joint angle trajectories, corresponding gait phase classifications, and timely generated stimulation patterns with three consecutive swing phases and two stance phases during SCI treadmill locomotion. This output demonstrates the performance of the complete system, from video input through vision AI processing to edge AI inference and microcontroller outputs.

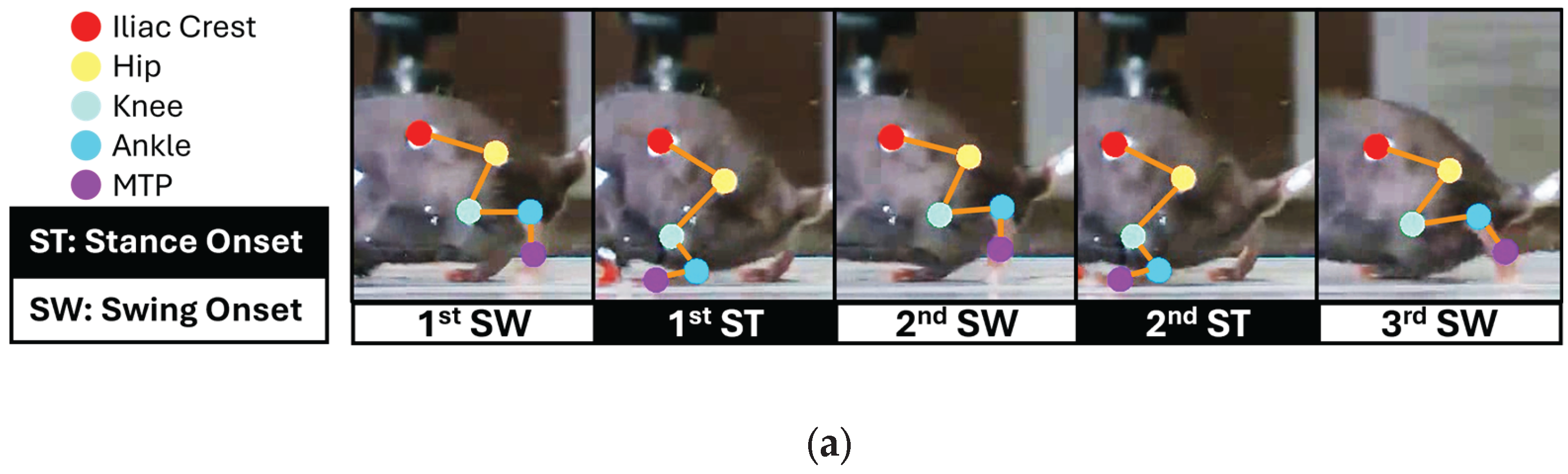

Figure 5a shows synchronized video frames with skeletal tracking overlay, illustrating the sequential gait phases (1st SW, 1st ST, 2nd SW, 2nd ST, 3rd SW) extracted by the vision AI system.

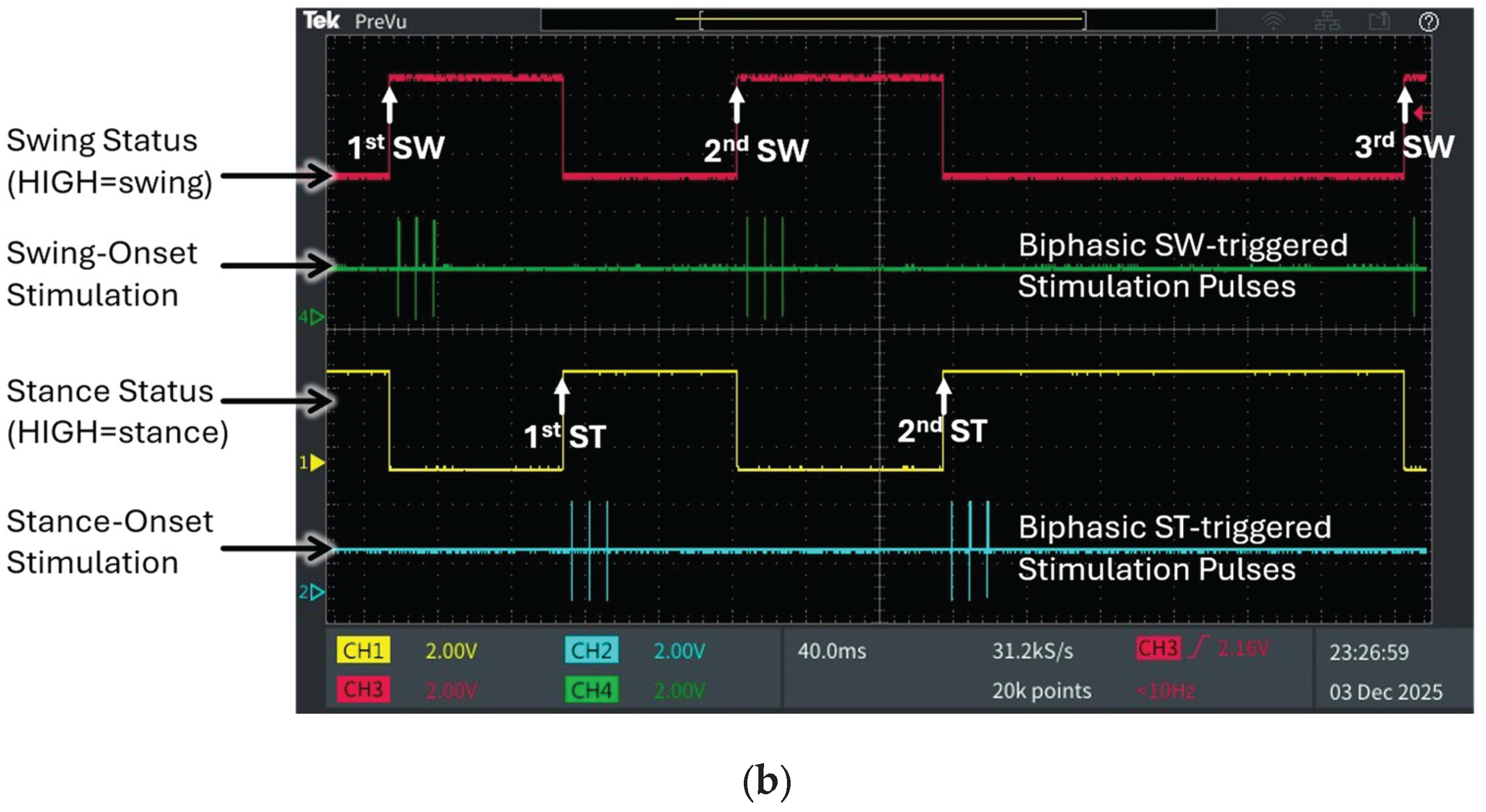

Figure 5b presents the corresponding oscilloscope traces showing real-time outputs produced by the developed edge AI model via post-processing of its softmax results. The digital waveforms generated by the microcontroller’s GPIO ports precisely align with the gait events in the video frames, as indicated by the upward arrows denoting temporal synchronization points. The system successfully classified swing and stance phases with reciprocal digital outputs: when the swing status port (magenta trace) transitioned to HIGH, the stance status port (yellow trace) remained LOW, and vice versa during stance phase detection. This reciprocal relationship confirms accurate real-time discrimination between the two primary gait phases.

In this SCI mouse, the edge AI model detected characteristic gait abnormalities. Unlike normal gait, which exhibits longer stance than swing duration, the first stance phase was shortened to approximately the same duration as the first swing phase. In contrast, the second stance phase was markedly prolonged relative to the first, resulting in an increased ankle joint angle at the onset of the third swing phase. The system accurately detected this biomechanical alteration in real-time bench top evaluation, demonstrating sensitivity to pathological gait patterns. Additionally, the system successfully triggered phase-dependent biphasic stimulation patterns based on detected gait events. Swing-onset stimulation pulses (green trace) were delivered precisely at the initiation of each swing phase, while stance-onset stimulation pulses (cyan trace) were triggered at stance transitions. Using the integrated hybrid vision–edge AI system, this study demonstrates the feasibility of closed-loop, event-driven neuromodulation. Visual input is processed to detect five anatomical landmarks and converted into joint angle data, which is classified by the lightweight edge AI model and immediately translated into therapeutic stimulation, achieving end-to-end latencies suitable for gait-responsive interventions.

4. Discussion

This study characterized distinct gait alterations in SCI mice and validated a proof-of-concept system combining vision AI for real-time joint angle extractions with edge AI for real-time gait phase detection and closed-loop biphasic neural stimulation pulse generation.

4.1. Gait Alterations in SCI Mice and Vision AI

Treadmill locomotion revealed clear differences between sham and SCI mice, with the SCI group exhibiting compensatory locomotor strategies, including altered joint angles, disrupted inter-joint coordination, and changes in spatiotemporal gait parameters. These findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that spinal cord injury disrupts coordinated hindlimb movements and necessitates adaptive motor strategies [

48,

49,

50,

51]. Accurate characterization of such gait deficits is essential for assessing neuromodulation efficacy and guiding rehabilitation protocol design. Traditional gait analysis methods rely on wearable devices such as EMG electrodes, IMUs, or reflective markers. Although effective, these approaches require direct skin contact, and stable attachment, which can be uncomfortable in human studies and especially challenging in small-animal experiments due to reflective marker detachment or behavioral interference.

As an alternative, camera-based markerless approaches, particularly AI-driven pose estimation, enable gait capture in an unconstrained environment, improving subject comfort and reducing experimental burden. However, conventional vision-based systems generate large volumes of raw data, require extensive post-processing, and remain susceptible to occlusion and misidentification.

In the present system, the vision AI model mitigates these challenges by extracting essential anatomical landmarks and converting them into hindlimb joint angles as a real-time preprocessing step. Only these reduced features are transmitted to the edge AI device, minimizing bandwidth requirements and preserving data privacy through localized processing. This decentralized pipeline enhances both efficiency and translational potential.

4.2. On-Device Edge AI for Real-Time Closed-Loop Neuromodulation

The edge AI model performs real-time gait phase classification, and its softmax outputs are mapped to generate precisely timed triggering signals for biphasic stimulation on a microcontroller, with processing latencies below 100 µs, enabling a robust, on-device closed-loop neuromodulation architecture. A lightweight multilayer perceptron (MLP) was selected to accommodate the computational constraints while maintaining low latency. Importantly, the integrated model-trained on combined sham and SCI datasets-generalized effectively to unseen SCI gait data, demonstrating the potential for unified models capable of handling multiple gait patterns without injury-specific training. Future development should focus on adaptive, generalizable models that account for individual variability and evolving gait patterns during recovery, which will be critical for the clinical translation of closed-loop neuromodulation systems.

Notably, the novel hybrid AI pipeline was proposed, implemented, and evaluated in this study, combining vision AI for anatomical landmark detection and kinematic feature extraction with on-device edge AI for gait phase inference to timely trigger closed-loop neural stimulation. By separating preprocessing and inference tasks across two AI modules, the system enables robust, low-latency control of gait-dependent stimulation on a low-power embedded platform. These capabilities not only demonstrate proof-of-concept for advanced neuromodulation strategies but also bridge the gap toward clinically deployable, wearable, or implantable systems. This approach can establish a new paradigm for AI-based closed-loop neuromodulation, using two powerful AI models integrated with real-time neuromodulation.

Although the current system uses wired USART communication between the vision AI and edge AI modules, this interface could be replaced with wireless communications such as medical implant communication service (MICS) [

9], ultra-wideband (UWB) [

52], Bluetooth [

14], or Wi-Fi [

53], enabling fully wireless operation. Eliminating tethered connections would enhance patient comfort and facilitate a seamless transition toward practical wearable or implantable closed-loop neuromodulation devices.

4.3. Limitations

Differences in gait patterns and locomotor performance between sham and SCI groups were observed, but the small sample size in each group (n = 3) limits statistical power and the generalizability of the findings. Larger cohorts are needed in future studies to strengthen the robustness of these conclusions. While the current experiments focus on cervical-level injuries, thoracic-level lesions should also be examined, as they typically result in more severe disruption of descending motor pathways destined for the hindlimb and may exhibit distinct compensatory gait patterns. From a system perspective, the hybrid system combining vision AI preprocessing and edge AI inference was successfully evaluated, demonstrating that gait data can be processed and stimulation commands generated with latencies under 100 µs, suitable for real-time closed-loop control. However, this evaluation relied on pre-recorded video rather than live video streams. Therefore, practical implementation will require additional experiments with freely moving subjects to confirm efficacy under actual closed-loop conditions, including real-time video acquisition, neural signal interference, and dynamic behavioral variability.

5. Conclusions

This study characterized locomotor differences between sham and SCI mice and demonstrated a proof-of-concept closed-loop neuromodulation system that integrates vision AI for deep-learning–based real-time pose estimation with an edge AI model deployed on a power-efficient microcontroller for gait phase detection and triggering of precisely timed biphasic stimulation patterns at processing speeds suitable for real-time operation. The system’s low-power, locally executable AI architecture—key features of edge AI—highlights its potential for use in wearable, fully implantable, or otherwise power-limited neuromodulation devices. Furthermore, the developed system can be readily adapted for future in vivo experiments by switching from recorded video to live camera input and connecting the outputs to a voltage-controlled current source circuit and directly to the neuromuscular system. This on-device processing approach supports the development of wireless, implantable neuromodulation devices with enhanced security and portability. Future studies will evaluate the system’s efficacy in restoring gait function and advance the technology toward clinical translation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and W.W.; methodology, A.S., J.V., X.D. and W.W. ; software, A.S.; validation, A.S., J.V., X.D. and W.W.; formal analysis, A.S., J.V. and W.W.; investigation, A.S., J.V. and X.D.; resources, X.D. and W.W.; data curation, A.S. and J.V.; writing, original draft preparation, A.S. and W.W.; writing, review and editing, A.S., J.V. and W.W.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, W.W.; project administration, W.W.; funding acquisition, W.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by NIH R01NS111776, 1R01NS103481, NIHR01NS131489, and Indiana State Department of Health (ISDH, Grant# 58180).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC#23116) of Indiana University School of Medicine and Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC) and strictly followed the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide on humane care and the use of laboratory animals.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5 series) for language refinement. The authors reviewed and edited the generated content and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCI |

Spinal cord injury |

| MLP |

Multilayer perceptron |

| EMG |

Electromyography |

| iEMG |

Intramuscular electromyography |

| IMU |

Inertial measurement unit |

| USB |

Universal serial bus |

| USART |

Universal synchronous/asynchronous receiver/transmitter |

| DAC |

Digital-to-analog converter |

| GPIO |

General purpose input/output |

| ROM |

Range of motion |

| MICS |

Medical implant communication service |

| UWB |

Ultra-wideband |

References

- Zhang, W. Wearable sensor-based quantitative gait analysis in Parkinson’s disease patients with different motor subtypes. NPJ Digit Med 2024, 7(1), p. 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardi, A.P.J. Gait parameters of Parkinson’s disease compared with healthy controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2021, 11(1), 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M. Digital gait biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease: susceptibility/risk, progression, response to exercise, and prognosis. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2025, 11(1), p. 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F. Gait Analysis in Neurologic Disorders: Methodology, Applications, and Clinical Considerations. Neurology 2025, 105(8), p. e214154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y. Gait variability in people with neurological disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Mov Sci 2016, 47, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schniepp, R. Fall prediction in neurological gait disorders: differential contributions from clinical assessment, gait analysis, and daily-life mobility monitoring. J Neurol 2021, 268(9), 3421–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angeli, C.A. Recovery of Over-Ground Walking after Chronic Motor Complete Spinal Cord Injury. N Engl J Med 2018, 379(13), 1244–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirelman, A. Gait impairments in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol 2019, 18(7), 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shon, A. An Implantable Wireless Neural Interface System for Simultaneous Recording and Stimulation of Peripheral Nerve with a Single Cuff Electrode. Sensors (Basel) 2017, 18(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.U. Gait phase detection from sciatic nerve recordings in functional electrical stimulation systems for foot drop correction. Physiol Meas 2013, 34(5), 541–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, K.D.; Hoffer, J.A. Gait phase information provided by sensory nerve activity during walking: applicability as state controller feedback for FES. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 1999, 46(7), 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, A. Fully Implantable Plantar Cutaneous Augmentation System for Rats Using Closed-loop Electrical Nerve Stimulation. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Circuits and Systems 2021, 15(2), 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, A.; et al. Edge AI-Based Closed-Loop Peripheral Nerve Stimulation System for Gait Rehabilitation after Spinal Cord Injury. 2023 11th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering (NER), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shon, A. Closed-Loop Plantar Cutaneous Augmentation by Electrical Nerve Stimulation Increases Ankle Plantarflexion During Treadmill Walking. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2021, 68(9), 2798–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karacan, I. Estimating and minimizing movement artifacts in surface electromyogram. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2023, 70, 102778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotz, T.; Gizzi, L.; Rohrle, O. Investigating the spatial resolution of EMG and MMG based on a systemic multi-scale model. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 2022, 21(3), 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.C. Multiple-Wearable-Sensor-Based Gait Classification and Analysis in Patients with Neurological Disorders. Sensors (Basel) 2018, 18(10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledoux, E.D. Inertial Sensing for Gait Event Detection and Transfemoral Prosthesis Control Strategy. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2018, 65(12), 2704–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Shushtari, M.; Arami, A. IMU-Based Real-Time Estimation of Gait Phase Using Multi-Resolution Neural Networks. Sensors (Basel) 2024, 24(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos Mazon, D. IMU-Based Classification of Locomotion Modes, Transitions, and Gait Phases with Convolutional Recurrent Neural Networks. Sensors (Basel) 2022, 22(22). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, A. DeepLabCut: markerless pose estimation of user-defined body parts with deep learning. Nat Neurosci 2018, 21(9), 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidzinski, L. Deep neural networks enable quantitative movement analysis using single-camera videos. Nat Commun 2020, 11(1), p. 4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L. Artificial intelligence-enhanced 3D gait analysis with a single consumer-grade camera. J Biomech 2025, 187, 112738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louie, K.H. Adaptive deep brain stimulation timed to gait phase improves walking in Parkinson’s disease. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Seta, V.; Romeni, S. Multimodal closed-loop strategies for gait recovery after spinal cord injury and stroke via the integration of robotics and neuromodulation. Front Neurosci 2025, 19, 1569148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formento, E. Electrical spinal cord stimulation must preserve proprioception to enable locomotion in humans with spinal cord injury. Nat Neurosci 2018, 21(12), 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, F.M. Sensory feedback restoration in leg amputees improves walking speed, metabolic cost and phantom pain. Nat Med 2019, 25(9), 1356–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowald, A. Activity-dependent spinal cord neuromodulation rapidly restores trunk and leg motor functions after complete paralysis. Nat Med 2022, 28(2), 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W. Transhemispheric cortex remodeling promotes forelimb recovery after spinal cord injury. JCI Insight 2022, 7(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.J. A novel vertebral stabilization method for producing contusive spinal cord injury. J Vis Exp 2015, 95, p. e50149. [Google Scholar]

- Zorner, B. Profiling locomotor recovery: comprehensive quantification of impairments after CNS damage in rodents. Nat Methods 2010, 7(9), 701–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filli, L. Motor deficits and recovery in rats with unilateral spinal cord hemisection mimic the Brown-Sequard syndrome. Brain 2011, 134 Pt 8, 2261–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, G.A. Real-time, low-latency closed-loop feedback using markerless posture tracking. Elife 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STMicroelectronics. NUCLEO-U575ZI-Q development board. 2025. Available online: https://www.st.com/en/evaluation-tools/nucleo-u575zi-q.html.

- Hassarati, R.T.; Foster, L.J.; Green, R.A. Influence of Biphasic Stimulation on Olfactory Ensheathing Cells for Neuroprosthetic Devices. Front Neurosci 2016, 10, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, N.; Kilgore, K.L.; Peckham, P.H. Implanted stimulators for restoration of function in spinal cord injury. Med Eng Phys 2001, 23(1), 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwilliam, J.C.; Horch, K. A charge-balanced pulse generator for nerve stimulation applications. J Neurosci Methods 2008, 168(1), 146–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, S.; Thakor, N.V. Implantable neurotechnologies: electrical stimulation and applications. Med Biol Eng Comput 2016, 54(1), 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay, T. Degradation of mouse locomotor pattern in the absence of proprioceptive sensory feedback. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111(47), 16877–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makii, Y. Alteration of gait parameters in a mouse model of surgically induced knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2018, 26(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y. Markerless analysis of hindlimb kinematics in spinal cord-injured mice through deep learning. Neurosci Res 2022, 176, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, J.P.; Cappellari, O.; Hutchinson, J.R. A Dynamic Simulation of Musculoskeletal Function in the Mouse Hindlimb During Trotting Locomotion. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2018, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manesh, S.B. Compensatory changes after spinal cord injury in a remyelination deficient mouse model. J Neurochem 2025, 169(1), p. e16220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.I. Video-based gait analysis for functional evaluation of healing achilles tendon in rats. Ann Biomed Eng 2012, 40(12), 2532–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Reduction of prolonged excitatory neuron swelling after spinal cord injury improves locomotor recovery in mice. Sci Transl Med 2024, 16(766), p. eadn7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. Reactivation of Dormant Relay Pathways in Injured Spinal Cord by KCC2 Manipulations. Cell 2018, 174(6), 1599. [Google Scholar]

- Takeoka, A. S. Arber, Functional Local Proprioceptive Feedback Circuits Initiate and Maintain Locomotor Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury. Cell Rep 2019, 27(1), 71–85 e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y. Functional reorganization of locomotor kinematic synergies reflects the neuropathology in a mouse model of spinal cord injury. Neurosci Res 2022, 177, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danner, S.M. Spinal control of locomotion before and after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol 2023, 368, 114496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brommer, B. Improving hindlimb locomotor function by Non-invasive AAV-mediated manipulations of propriospinal neurons in mice with complete spinal cord injury. Nat Commun 2021, 12(1), p. 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, W. NG2 glia reprogramming induces robust axonal regeneration after spinal cord injury. iScience 2024, 27(2), p. 108895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, H. Wireless Multichannel Neural Recording With a 128-Mbps UWB Transmitter for an Implantable Brain-Machine Interfaces. IEEE Trans Biomed Circuits Syst 2016, 10(6), 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, W. A Wireless Bi-Directional Brain-Computer Interface Supporting Both Bluetooth and Wi-Fi Transmission. Micromachines (Basel) 2024, 15(11). [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).