1. Introduction

1.1. Digital Health: Concept and Evolution

The digitalization of medicine has evolved over several decades. Early discussions emerged in 1966, when Schoenfeld highlighted the potential of digital computers to support public health through faster data processing [

1]. Telemedicine initiatives began even earlier: in 1959, the University of Nebraska introduced a two-way, closed-circuit microwave system for medical consultations and education, followed by the expansion of telemedicine programs throughout the 1970s and 1980s to support rural healthcare professionals [

2].

By the 1990s, the term digital health began to appear, initially referring to the digitization of health information and medical libraries under concepts such as the “Digital Library of the Health Sciences”[

3,

4]. The emergence of the internet and the World Wide Web further accelerated this shift, enabling rapid dissemination of medical information, fostering global collaboration, and enhancing communication among healthcare professionals [

5]. However, these advances also raised new challenges related to intellectual property, patient data protection, and equitable access to reliable health information [

6].

In 2001, Eysenbach introduced the influential definition of eHealth, characterizing it as the intersection of medical informatics, public health, and business—encompassing health services enhanced through internet and communication technologies [

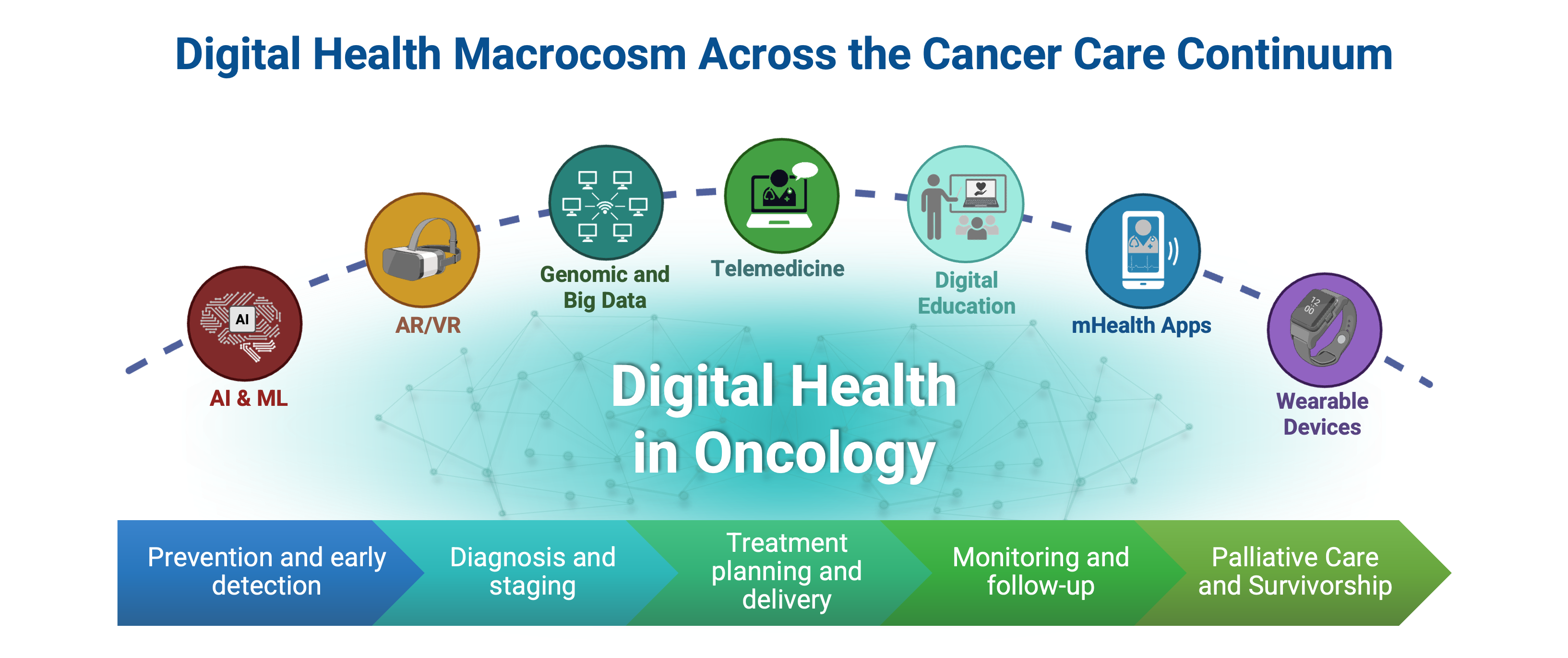

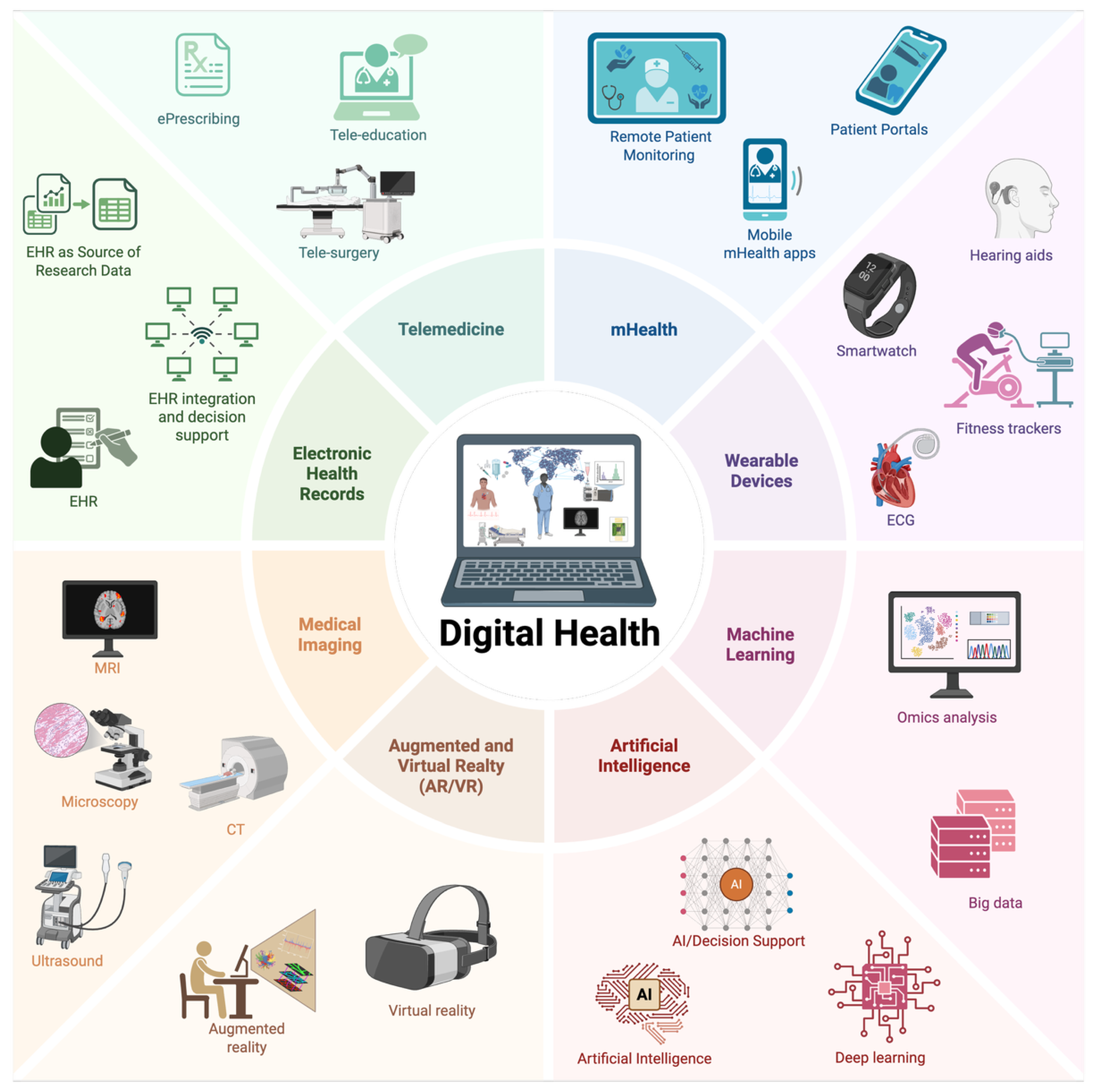

7]. Over time, digital health has expanded into a broader framework that includes telemedicine, mHealth, wearables, big data analytics, AI, ML, and immersive technologies such as virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR) (

Figure 1) [

8].

Digital health tools are now part of daily clinical practice, improving communication, reducing travel burdens, enhancing self-monitoring, and supporting timely medical interventions. This review explores these tools and their applications across oncology, with emphasis on their benefits, limitations, and future opportunities.

2. Telemedicine and Telehealth: Concepts and Scope

Telehealth and telemedicine are central components of digital health but represent distinct concepts. Telemedicine refers specifically to the remote delivery of clinical services using telecommunication technologies, typically through real-time, two-way audiovisual interaction between clinicians and patients [

9]. In contrast, telehealth encompasses a broader range of clinical and non-clinical activities, including provider training, administrative meetings, public health education, and secure exchange of electronic health information [

10].

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated global adoption of telehealth, demonstrating its capacity and practicality to maintain continuity of care, improve accessibility, reduce geographic barriers, and enhance the efficiency of healthcare delivery. Telehealth is no longer a supplementary modality; it has become an essential component of modern care, particularly for patients in remote or underserved areas [

11].

Clinically, telemedicine improves treatment adherence, enhances appointment compliance, and strengthens patient engagement [

12]. It reduces travel time, lowers associated costs, minimizes exposure to infectious diseases, and often improves patient comfort by enabling consultations from home [

13,

14,

15]. Numerous studies across oncology and other specialties have demonstrated that telemedicine achieves comparable clinical outcomes to in-person visits while maintaining high patient satisfaction [

16,

17].

2.1. Privacy and Confidentiality

The expansion of telemedicine introduces new challenges related to privacy, confidentiality, and the protection of personal health information (PHI) [

9,

18]. Telemedicine platforms must comply with legal and regulatory frameworks such as HIPAA in the United States, GDPR in Europe, and equivalent national or regional standards [

18,

19]. Clinicians have an ethical obligation to ensure that any platform or digital tool used for patient care employs transparent data policies and robust security safeguards [

20].

From an ethical standpoint, it is important to consider that telemedicine is not always the most appropriate model for serving all patients. For example, not all countries have equitable access to the internet and technology. Telemedicine introduces new contexts, but it does not alter the fundamental ethical obligations of the physician: primacy of the patient’s well-being, competence, transparency, confidentiality, and continuity of care. On the other hand, the ethical quality of telemedicine depends on how aspects such as technology, the doctor–patient relationship, data confidentiality, informed consent, and patient and family satisfaction are managed [

21,

22].

From a technological perspective, secure telemedicine systems must implement encryption, multi-factor authentication, password protection, restricted access controls, automatic timeouts, and audit trails to detect unauthorized access. PHI encompasses a broad range of identifiers, including names, addresses, email accounts, and phone numbers, thus requiring stringent data handling procedures. Continuous software updates and cybersecurity monitoring are also essential to mitigate risk [

23].

3. Mobile Health (mHealth)

Mobile health (mHealth) has emerged as one of the most influential drivers of healthcare transformation [

24,

25]. The U.S. NIH defines mHealth as the use of mobile and wireless technologies to improve health outcomes, healthcare services, and health research. Smartphones, tablets, and wearable sensors enable remote monitoring, diagnostic support, medication adherence tracking, and health education [

26].

mHealth applications leverage device-embedded sensors and connectivity to collect biometric data, perform image-based assessments, deliver reminders, and support video-based telemedicine encounters. These tools assist clinical decision-making, promote treatment adherence, enhance patient engagement, and encourage self-management, factors consistently associated with improved outcomes [

27,

28]. mHealth platforms also expand access to disease-related education, facilitating personalized guidance on prevention, medication use, and lifestyle modification [

29,

30].

Despite their promise, adoption remains uneven globally. Many mHealth tools are designed for high-income countries, while low- and middle-income regions face challenges related to infrastructure limitations, inconsistent digital literacy, and unclear regulations [

31]. Concerns also persist regarding app validity, data security, and interoperability. Robust evidence generation and regulatory frameworks are essential to support widespread, safe, and equitable mHealth use [

32].

4. Wearable Technologies

Wearable devices and remote monitoring systems are key components of mHealth and play an increasingly important role in oncology care. These systems use biosensors and wireless connectivity to continuously collect and transmit physiological and behavioral data, enabling proactive health monitoring and early detection of abnormalities [

33,

34].

Wearables can be categorized by anatomical placement [

35]:

Head-worn devices: smart glasses, headbands, AR/VR interfaces, hearing aids, and EEG sensors used for neurological monitoring, surgical guidance, and medical education [

36,

37].

Limb-worn devices: wristbands, smartwatches, fitness trackers, and lower-limb sensors that measure heart rate, temperature, oxygen saturation, physical activity, and gait [

38,

39,

40,

41].

Torso-worn devices: smart textiles, belts, and vests capable of tracking respiration, ECG, posture, and other vital parameters [

42,

43,

44].

Advances in flexible electronics and nanomaterials have enabled smart clothing capable of continuous, unobtrusive physiological monitoring. These technologies provide valuable insights for chronic disease management, rehabilitation, and integration into digital health ecosystems.

5. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

AI and ML have become foundational technologies in digital health, reshaping how clinical data are generated, analyzed, and applied [

45,

46,

47]. AI encompasses systems capable of reasoning, problem-solving, pattern recognition, and natural language processing. ML, a subfield of AI, focuses on algorithms that learn from data and improve performance over time [

48,

49,

50].

The rapid expansion of biomedical datasets, from electronic health records (EHRs), medical imaging, genomics, and wearables, has fueled the development of predictive, diagnostic, and decision-support models [

45]. Wearable sensors, for example, generate real-time physiological data that ML algorithms can analyze to detect subtle patterns predictive of deterioration or disease progression [

51]. In oncology, AI-driven tools contribute to early cancer detection, segmentation and characterization of tumors, treatment response prediction, and digital pathology [

52,

53].

AI’s impact is particularly notable in three domains:

Clinical data interpretation: ML models optimize EHR data to predict diagnoses, readmissions, and care needs, though issues like missing data and coding variability persist [

51].

Medical imaging: AI achieves expert-level performance in tasks such as detection of diabetic retinopathy, skin cancer classification, breast cancer screening, and early detection of colon and pancreatic cancer (reference) [

54,

55,

56].

Precision medicine: Integration of omics (proteomics, genomics, metabolomics, etc.), clinical variables, and radiomics enables identification of molecular patterns that guide targeted therapies [

57,

58].

Together, these advances demonstrate how AI and ML enable more precise, data-driven, and scalable healthcare delivery.

6. Digital Therapeutics

Digital therapeutics (DTx) represent a rapidly evolving category of digital health interventions in which evidence-based software is used with the explicit intention to prevent, manage, or treat disease. The origins of DTx can be traced to efforts to digitize non-pharmacological therapies, most notably cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), to improve accessibility and scalability. To date, DTx have demonstrated clinical benefit across conditions where behavioral and psychosocial interventions are central, particularly in mental health, by reducing barriers to care such as stigma, cost, travel, and workforce limitations [

59].

In oncology, DTx are emerging as valuable adjuncts across the cancer care continuum, particularly in symptom management, supportive care, and survivorship. Digital therapeutic platforms have been developed to address cancer-related fatigue, pain, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and treatment-related cognitive impairment, using structured CBT modules, mindfulness-based interventions, and behavior-change frameworks. DTx have also shown promise in supporting treatment adherence, promoting physical activity and nutrition during and after therapy, and facilitating self-management of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-related toxicities [

60].

Ongoing research efforts are increasingly focused on elucidating mechanisms of action, optimizing target engagement, exploring “digital dosing” and evaluating synergies between multiple digital interventions or between digital and pharmacologic therapies. Within oncology, these advances position DTx as promising adjuncts for symptom management, behavioral modification, treatment adherence, and supportive care across the cancer care continuum.

7. Digital Health Applications Across the Cancer Care Continuum

Digital health innovations are reshaping oncology by improving prevention, facilitating early detection, enhancing diagnostic accuracy, informing personalized treatment planning, enabling continuous monitoring, and supporting survivorship and palliative care. These technologies collectively promote more efficient, accessible, and patient-centered cancer care (

Figure 2).

7.1. Prevention and Early Detection

Prevention strategies focus on reducing cancer risk through behavior modification and early recognition of warning signs. Digital health enhances prevention by enabling scalable, personalized interventions through wellness apps that promote smoking cessation, physical activity, weight control, moderated alcohol use, and sun protection. Digital health interventions (DHIs) incorporating behavior-change techniques, such as goal-setting, self-monitoring, and automated feedback, have demonstrated improvements in health behaviors across diverse populations [

61].

Digital platforms also expand access to screening programs. Smartphone-based tools have been used for cervical, oral, prostate, skin, and breast cancer screening, particularly in resource-limited settings where they can improve feasibility and reduce logistical barriers [

62]. Although user satisfaction remains variable, these tools show promise for increasing screening coverage and supporting community-level interventions.

In a recent meta-analysis of 15 articles involving 23,103 women from America, Europe, Asia, and Africa, it was concluded that electronic interventions increased cervical cancer screening participation (RR 1.464; 95% CI 1.285–1.667), with an absolute difference of 11.9 percentage points (34% vs. 27%). The effect was maintained in both the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis (RR 1.382; 95% CI 1.214–1.574) and the per-protocol analysis (RR 1.565; 95% CI 1.381–1.772) and remained significant after sensitivity analyses and exclusion of studies at high risk of bias [

63].

A meta-analysis reviewing 13 clinical trials with 1,448 participants evaluated whether eHealth improved the quality of life of women with breast cancer. The eHealth group showed significantly higher quality of life than the usual care group, as well as in the physical and emotional domains. Therefore, it was concluded that eHealth is superior to usual care in improving the quality of life of women with breast cancer. Therefore, the authors recommended considering the use of eHealth in clinical practice, although further research is needed to determine the impact of different types of eHealth on specific quality-of-life domains [

64].

AI further strengthens early detection. AI-enhanced imaging improves sensitivity, specificity, and consistency in radiologic interpretation. For example, AI models for prostate MRI can outperform radiologists in predicting clinically significant disease using optimized biopsy strategies. These technologies reduce interobserver variability, accelerate diagnostic workflows, and may reduce unnecessary procedures [

65].

Together, DHIs, screening platforms, and AI-driven detection tools are transforming prevention and early diagnosis. Continued research is needed to address long-term effectiveness, user experience, and equitable implementation.

7.2. Diagnostics and Staging

Digital health technologies are redefining diagnostic precision by integrating multimodal data, genomic markers, imaging, pathology, and clinical information into advanced analytical models. AI and ML identify subtle patterns across these large datasets, allowing earlier and more accurate cancer detection [

66,

67].

Radiomics plays a central role in this shift. By extracting quantitative features from imaging (e.g., CT, MRI, PET), radiomics captures tumor phenotypes that are not visually apparent [

68]. ML models trained on radiomic signatures can predict tumor aggressiveness, treatment response, and patient outcomes. These approaches help standardize interpretation and reduce variability among clinicians [

69,

70].

Digital pathology further enhances diagnostic consistency. Algorithms trained on whole-slide images can detect and grade malignancies with high accuracy. In breast cancer, AI systems have shown excellent performance (AUC ≈ 0.99) in identifying micrometastases in lymph nodes, matching or surpassing expert pathologists [

71].

Liquid biopsies represent another transformative tool. By analyzing circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and other biomarkers, liquid biopsies allow minimally invasive assessment of tumor genetics, disease progression, and treatment response [

72,

73]. In non–small cell lung cancer, ctDNA testing is increasingly used to identify actionable mutations such as EGFR, KRAS, ALK, and others [

74,

75]. AI-supported interpretation enhances sensitivity, particularly when ctDNA levels are low [

76].

Deep learning-based AI systems have demonstrated significant improvements in breast cancer detection, with greater accuracy, reduced false positives and negatives, and the ability to identify subtle anomalies that might go unnoticed by radiologists. In some cases, AI systems have outperformed average radiologists, showing an improvement in the area under the ROC curve (AUROC) and greater consistency in image interpretation. These advances enable the identification of subtle anomalies, facilitate early detection, and personalize treatment, although challenges persist, such as the lack of standardized data and the need for rigorous validation. Therefore now, we need to consider the need to adapt the medical guidelines that enhance the reliable and safe use of IA in clinical [

77]. Collectively, radiomics, digital pathology, and AI-enhanced liquid biopsy are advancing precision diagnostics and enabling earlier, more accurate staging.

7.3. Treatment Planning and Prognosis

Cancer treatment requires multidisciplinary approach, incorporating clinical, imaging, genomic, and patient-reported data. Digital health tools, particularly AI and ML, enable development of decision-support systems that integrate these data streams to optimize personalized therapy.

Genomic sequencing identifies mutations that drive cancer progression, informing targeted therapy and immunotherapy decisions. Integrating genomic profiles with AI models enhances prediction of treatment response, toxicity, and prognosis, advancing precision oncology [

78].

AI-driven clinical decision support systems (CDSS), such as Watson for Oncology, analyze clinical guidelines and scientific literature to provide evidence-based recommendations [

79,

80]. Although adoption challenges remain, including validation needs and potential algorithmic bias, these systems demonstrate the potential for scalable, standardized decision assistance.

In breast cancer, deep learning models using serial ultrasonography and autosegmentation have achieved high predictive accuracy for pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy [

81]. Multimodal networks combining imaging, clinical variables, histopathology, and molecular markers further refine prognostic accuracy [

82].

For example, a meta-analysis evaluates the use of artificial intelligence to diagnose colorectal cancer via CT and MRI. The findings indicated that AI models exhibit moderate sensitivity and specificity in identifying lymph node metastases, with a combined sensitivity of 0.776 and a specificity of 0.676. The ROC curve area for radiomics in rectal cancer was 0.846, which is acceptable but could be better. Therefore, the AI could have a positive role in staging the colorectal cancer before surgery [

83].

Digital health tools are increasingly supporting patient education and shared decision-making in complex oncologic care. MyCareGorithm (MCG) is a point-of-care digital platform that uses audiovisual and interactive content to explain cancer diagnoses and treatment options during clinical consultations. Pilot studies in pancreatic and prostate cancer showed high patient satisfaction, improved understanding of disease and treatment, and increased confidence in providers. Companions similarly reported improved comprehension, highlighting the value of these tools in caregiver engagement. Physicians reported that MCG facilitated the communication of complex information, improved consultation efficiency, and enhanced the quality of clinical encounters. Together, these findings support the integration of point-of-care digital education platforms as effective adjuncts to multidisciplinary oncology care, improving patient understanding, engagement, and shared decision-making while also supporting clinical workflow efficiency [

84,

85,

86].

7.3.1. AI-Enabled Radiation Oncology

Radiation therapy planning involves complex tasks, including segmentation, dose calculation, and optimization [

87]. AI-based autocontouring significantly reduces contouring time for tumors and organs-at-risk (OARs), while maintaining or improving accuracy. Combining autocontouring with automated treatment planning further decreases workload and may enhance reproducibility [

88].

Recent studies demonstrate that AI-generated treatment plans can achieve dosimetric quality comparable to, or better than, manually generated plans. Importantly, selective omission of manual edits for distant OARs may be feasible, preserving safety while enhancing workflow efficiency [

89,

90].

7.3.2. AI-Assisted Surgery and 3D Technologies

Robotic and computer-assisted surgery benefit from AI-enhanced visualization, anatomical landmark detection, and real-time guidance. Systems such as the da Vinci® platform use computer vision to improve precision and safety [

91].

Virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR) and patient-specific 3D modeling support preoperative planning by improving spatial understanding in anatomically complex regions. 3D-printed models aid surgical rehearsal, interdisciplinary discussion, and patient education [

92,

93].

7.4. Patient Monitoring and Follow-Up

Post-treatment surveillance is essential for detecting recurrence early, managing toxicity, and supporting recovery. Digital health has expanded remote monitoring capabilities through wearable sensors, mHealth platforms, and teleoncology.

Wearable devices monitor heart rate, sleep, oxygen saturation, mobility, and activity levels. Devices such as Fitbit, Garmin, ActiGraph, and ActivPAL have been used in oncology trials to assess fatigue, sleep disruption, and functional decline. Wearables support risk stratification, toxicity prediction, and rehabilitation planning [

94].

In surgical oncology, postoperative remote monitoring can identify high-risk patients who require additional support [

95]. Studies using wearable activity monitors show associations between decreased postoperative activity and increased complication risk [

96].

Teleoncology has become integral to follow-up care, offering accessible video consultations for reviewing results, managing symptoms, and discussing survivorship plans [

97,

98]. Patients report high satisfaction, though some express concerns about reduced personal interaction. Integrated digital platforms—such as OncoHealth® and Navya Network—combine telemedicine with AI-enabled triage, treatment navigation, and EHR integration, supporting continuous, coordinated care [

99,

100].

7.5. Palliative Care and End-of-Life Support

Digital health plays an increasingly important role in palliative care by improving symptom monitoring, care coordination, and access to support services.

Tele-palliative care enables real-time management of pain, distress, and medication needs while reducing emergency visits and hospitalizations. These systems proved particularly valuable during the COVID-19 pandemic and continue to benefit patients in remote regions [

101].

mHealth applications such as MyPal [

102] and PainCheck [

103] allow patients or caregivers of individuals with limited communication, to report symptoms in real time, enabling proactive intervention. Caregiver-centered platforms like CaringBridge facilitate communication, psychosocial support, and task coordination [

104].

VR/AR tools offer immersive experiences for anxiety reduction, guided relaxation, and reminiscence therapy. Studies show benefits in reducing pain, depression, and distress near end-of-life [

105,

106].

Digital tools for advance care planning (ACP), including platforms such as MyDirectives, help patients articulate preferences, ensuring that their values guide care decisions [

107,

108,

109]. These systems support shared decision-making and preserve dignity throughout the final stages of illness.

7.6. Survivorship

Digital health significantly enhances survivorship care by supporting long-term symptom tracking, lifestyle management, mental health, and structured follow-up.

mHealth applications, such as BENECA, My Guide, and My Health, provide tools for symptom logging, appointment reminders, education, and community support. These platforms improve adherence to survivorship care plans and empower patients to manage residual symptoms and lifestyle changes [

110,

111,

112].

Telehealth-based survivorship programs, including Project ECHO® and virtual multidisciplinary clinics, expand access to specialized survivorship expertise and promote consistent application of best practices [

113]. National efforts such as the Stanford Cancer Survivorship Program and the NHS eSurvivorship Initiative demonstrate high patient satisfaction and feasibility [

114,

115].

Digital mental health tools, including telepsychology and online cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), support survivors experiencing depression, anxiety, neuropathy, or fear of recurrence. Apps such as Mindfulness Coach increase access to non-pharmacologic interventions and complementary therapies [

116,

117].

Through these tools, survivorship care becomes more accessible, personalized, and comprehensive, supporting the long-term well-being of cancer survivors.

8. Conclusion

Digital health represents a pivotal convergence of technological innovation and modern oncology. Tools such as artificial intelligence, telemedicine, mobile health applications, wearables, and immersive technologies are reshaping how cancer care is delivered, monitored, and experienced across the full continuum, from prevention and early detection to diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, and end-of-life support.

These technologies enable earlier diagnosis, support personalized treatment planning, enhance communication among multidisciplinary teams, and empower patients to take an active role in their care. Remote monitoring and virtual consultations reduce geographic and socioeconomic barriers, while data-driven platforms improve clinical decision-making and resource allocation. Moreover, digital systems accelerate research by facilitating large-scale data integration and real-time clinical insights.

Despite these transformative benefits, significant challenges remain. Ensuring equitable access, protecting patient data, achieving interoperability, and addressing disparities in digital literacy are critical areas requiring sustained attention. Ethical considerations and transparent regulatory frameworks are essential to promote responsible use and safeguard patient trust.

Looking ahead, the thoughtful, patient-centered integration of digital health technologies has the potential to make oncology care more precise, accessible, and compassionate. By aligning innovation with equity and ethical practice, digital health can strengthen every stage of the cancer journey and help build a future where technology enhances the human elements of care.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Louis B. Harrison, Dr. Mauricio E. Gamez and Dr. Sarah Hoffe work for MyCareGorithm. The rest of the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT-5.2 to improve the structure, grammar, and language of the text. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| mHealth |

Mobile health |

| DTx |

Digital therapeutics |

| EHR |

Electronic health record |

| CT |

Computer tomography |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| VR/AR |

Virtual and augmented reality |

| PHI |

Personal health information |

| DHI |

Digital health interventions |

| CDSS |

Clinical decision support systems |

| OAR |

Organs-at-risk |

| ACP |

Advance care planning |

| CBT |

Cognitive behavioral therapy |

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

References

- R. L. Schoenfeld, “The Digital Computer and Public Health,” Archives of Environmental Health: An International Journal, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 327–332, Feb. 1967. [CrossRef]

- J. Preston, F. W. Brown, and B. Hartley, “Using Telemedicine to Improve Health Care in Distant Areas,” PS, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 25–32, Jan. 1992. [CrossRef]

- D. M. D’Alessandro et al., “Performing continuous quality improvement for a digital health sciences library through an electronic mail analysis,” Bull Med Libr Assoc, vol. 86, no. 4, pp. 594–601, Oct. 1998.

- R. E. Lucier, “Building a digital library for the health sciences: information space complementing information place,” Bull Med Libr Assoc, vol. 83, no. 3, pp. 346–350, July 1995.

- S. R. Frank, “Digital Health Care—The Convergence of Health Care and the Internet:,” Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 8–17, Apr. 2000. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Skiba, “Intellectual property issues in the digital health care world,” Nurs Adm Q, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 11–20, 1997.

- G. Eysenbach, “What is e-health?,” J Med Internet Res, vol. 3, no. 2, p. e20, June 2001. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Matricardi and S. Dramburg, Digital Allergology: From Theory to Practice. in Health Informatics. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. Chaet, J. E. Sabin, and K. Skimming, “Ethical practice in Telehealth and Telemedicine,” J GEN INTERN MED, vol. 32, no. 10, pp. 1136–1140, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Goedeke, A. Ertl, D. Zöller, S. Rohleder, and O. J. Muensterer, “Telemedicine for pediatric surgical outpatient follow-up: A prospective, randomized single-center trial,” Journal of Pediatric Surgery, vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 200–207, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. R. Dorsey and E. J. Topol, “State of Telehealth,” N Engl J Med, vol. 375, no. 2, pp. 154–161, July 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ma et al., “Telemedicine application in patients with chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” BMC Med Inform Decis Mak, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 105, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Teoli and N. R. Aeddula, “Telemedicine,” in StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025. Accessed: Oct. 16, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535343/.

- M. Maleki, S. M. Mousavi, O. Khosravizadeh, M. Heidari, M. Raadabadi, and M. Jahanpour, “Factors Affecting Use of Telemedicine and Telesurgery in Cancer Care (TTCC) among Specialist Physicians,” Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, vol. 19, no. 11, pp. 3123–3129, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. R. Wood and L. Caplan, “Outcomes, Satisfaction, and Costs of a Rheumatology Telemedicine Program: A Longitudinal Evaluation,” J Clin Rheumatol, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 41–44, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Patel, A. Mehrotra, H. A. Huskamp, L. Uscher-Pines, I. Ganguli, and M. L. Barnett, “Trends in Outpatient Care Delivery and Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the US,” JAMA Intern Med, vol. 181, no. 3, p. 388, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Sirintrapun and A. M. Lopez, “Telemedicine in Cancer Care,” American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book, no. 38, pp. 540–545, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- “General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – Legal Text,” General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Accessed: Oct. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://gdpr-info.eu/.

- P. F. Edemekong, P. Annamaraju, M. Afzal, and M. J. Haydel, “Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Compliance,” in StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025. Accessed: Oct. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500019/.

- B. G. Fields, “Regulatory, Legal, and Ethical Considerations of Telemedicine,” Sleep Medicine Clinics, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 409–416, Sept. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Chaet, J. E. Sabin, and K. Skimming, “Ethical practice in Telehealth and Telemedicine,” J GEN INTERN MED, vol. 32, no. 10, pp. 1136–1140, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Moghbeli, M. Langarizadeh, and A. Ali, “Application of Ethics for Providing Telemedicine Services and Information Technology,” Med Arch, vol. 71, no. 5, p. 351, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Singh et al., “American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) Position Paper for the Use of Telemedicine for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Sleep Disorders: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Position Paper,” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, vol. 11, no. 10, pp. 1187–1198, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Iyengar, “Mobile health (mHealth),” in Fundamentals of Telemedicine and Telehealth, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 277–294. [CrossRef]

- R. S. H. Istepanian, “Mobile Health (m-Health) in Retrospect: The Known Unknowns,” IJERPH, vol. 19, no. 7, p. 3747, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. S. H. Istepanian, E. Jovanov, and Y. T. Zhang, “Introduction to the special section on M-Health: Beyond Seamless Mobility and Global Wireless Health-Care Connectivity,” IEEE Trans. Inform. Technol. Biomed., vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 405–414, Dec. 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Rowland, J. E. Fitzgerald, T. Holme, J. Powell, and A. McGregor, “What is the clinical value of mHealth for patients?,” npj Digit. Med., vol. 3, no. 1, p. 4, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Free et al., “The Effectiveness of Mobile-Health Technologies to Improve Health Care Service Delivery Processes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” PLoS Med, vol. 10, no. 1, p. e1001363, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Marcolino, J. A. Q. Oliveira, M. D’Agostino, A. L. Ribeiro, M. B. M. Alkmim, and D. Novillo-Ortiz, “The Impact of mHealth Interventions: Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews,” JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, vol. 6, no. 1, p. e23, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Ryu, “Book Review: mHealth: New Horizons for Health through Mobile Technologies: Based on the Findings of the Second Global Survey on eHealth (Global Observatory for eHealth Series, Volume 3),” Healthc Inform Res, vol. 18, no. 3, p. 231, 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. Kruse, J. Betancourt, S. Ortiz, S. M. Valdes Luna, I. K. Bamrah, and N. Segovia, “Barriers to the Use of Mobile Health in Improving Health Outcomes in Developing Countries: Systematic Review,” J Med Internet Res, vol. 21, no. 10, p. e13263, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. L. Lewis and J. C. Wyatt, “mHealth and Mobile Medical Apps: A Framework to Assess Risk and Promote Safer Use,” J Med Internet Res, vol. 16, no. 9, p. e210, Sept. 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Piwek, D. A. Ellis, S. Andrews, and A. Joinson, “The Rise of Consumer Health Wearables: Promises and Barriers,” PLoS Med, vol. 13, no. 2, p. e1001953, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Chandrasekaran, V. Katthula, and E. Moustakas, “Patterns of Use and Key Predictors for the Use of Wearable Health Care Devices by US Adults: Insights from a National Survey,” J Med Internet Res, vol. 22, no. 10, p. e22443, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. C. Koydemir and A. Ozcan, “Wearable and Implantable Sensors for Biomedical Applications,” Annual Rev. Anal. Chem., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 127–146, June 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Hu et al., “Application and Prospect of Mixed Reality Technology in Medical Field,” CURR MED SCI, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 1–6, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Loncar-Turukalo, E. Zdravevski, J. Machado Da Silva, I. Chouvarda, and V. Trajkovik, “Literature on Wearable Technology for Connected Health: Scoping Review of Research Trends, Advances, and Barriers,” J Med Internet Res, vol. 21, no. 9, p. e14017, Sept. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Liang et al., “Usability Study of Mainstream Wearable Fitness Devices: Feature Analysis and System Usability Scale Evaluation,” JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, vol. 6, no. 11, p. e11066, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. P. Walmsley, S. A. Williams, T. Grisbrook, C. Elliott, C. Imms, and A. Campbell, “Measurement of Upper Limb Range of Motion Using Wearable Sensors: A Systematic Review,” Sports Med - Open, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 53, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Dunn, R. Runge, and M. Snyder, “Wearables and the Medical Revolution,” Per. Med., vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 429–448, Sept. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Powell, J. Parker, M. Martyn St-James, and S. Mawson, “The Effectiveness of Lower-Limb Wearable Technology for Improving Activity and Participation in Adult Stroke Survivors: A Systematic Review,” J Med Internet Res, vol. 18, no. 10, p. e259, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Xu et al., “Configurable, wearable sensing and vibrotactile feedback system for real-time postural balance and gait training: proof-of-concept,” J NeuroEngineering Rehabil, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 102, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Argent, P. Slevin, A. Bevilacqua, M. Neligan, A. Daly, and B. Caulfield, “Clinician perceptions of a prototype wearable exercise biofeedback system for orthopaedic rehabilitation: a qualitative exploration,” BMJ Open, vol. 8, no. 10, p. e026326, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Stoppa and A. Chiolerio, “Wearable Electronics and Smart Textiles: A Critical Review,” Sensors, vol. 14, no. 7, pp. 11957–11992, July 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. Rattan, D. D. Penrice, and D. A. Simonetto, “Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: What You Always Wanted to Know but Were Afraid to Ask,” Gastro Hep Advances, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 70–78, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Kersting, “Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence: Two Fellow Travelers on the Quest for Intelligent Behavior in Machines,” Front Big Data, vol. 1, p. 6, 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Kühl, M. Schemmer, M. Goutier, and G. Satzger, “Artificial intelligence and machine learning,” Electron Markets, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 2235–2244, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Collins, D. Dennehy, K. Conboy, and P. Mikalef, “Artificial intelligence in information systems research: A systematic literature review and research agenda,” International Journal of Information Management, vol. 60, p. 102383, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Aubrey, “What’s the Difference Between Deep Learning Training and Inference?,” NVIDIA Blog. Accessed: Oct. 20, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/difference-deep-learning-training-inference-ai/.

- Al Kuwaiti et al., “A Review of the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare,” J Pers Med, vol. 13, no. 6, p. 951, June 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Habehh and S. Gohel, “Machine Learning in Healthcare,” CG, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 291–300, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. C. Willis et al., “Digital Health Interventions to Enhance Prevention in Primary Care: Scoping Review,” JMIR Med Inform, vol. 10, no. 1, p. e33518, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Cohen and L. H. Schwamm, “Digital Health for Oncological Care,” Cancer J, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 34–39, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Gulshan et al., “Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Algorithm for Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy in Retinal Fundus Photographs,” JAMA, vol. 316, no. 22, p. 2402, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Esteva et al., “Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks,” Nature, vol. 542, no. 7639, pp. 115–118, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. M. McKinney et al., “International evaluation of an AI system for breast cancer screening,” Nature, vol. 577, no. 7788, pp. 89–94, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhuang, “How genomics and multi-modal AI are reshaping precision medicine,” Front. Med., vol. 12, p. 1660889, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Israni et al., “Precision medicine: Crossing the biomedical scales with AI,” The Journal of Precision Medicine: Health and Disease, vol. 3, p. 100010, Oct. 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Ribba, R. Peck, L. Hutchinson, I. Bousnina, and D. Motti, “Digital Therapeutics as a New Therapeutic Modality: A Review from the Perspective of Clinical Pharmacology,” Clin Pharma and Therapeutics, vol. 114, no. 3, pp. 578–590, Sept. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Hong, C. Wasden, and D. H. Han, “Introduction of digital therapeutics,” Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, vol. 209, p. 106319, Sept. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Mair et al., “Effective Behavior Change Techniques in Digital Health Interventions for the Prevention or Management of Noncommunicable Diseases: An Umbrella Review,” Annals of Behavioral Medicine, vol. 57, no. 10, pp. 817–835, Sept. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Salmani, M. Ahmadi, and N. Shahrokhi, “The Impact of Mobile Health on Cancer Screening: A Systematic Review,” Cancer Inform, vol. 19, p. 1176935120954191, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu, L. Ning, W. Fan, C. Jia, and L. Ge, “Electronic Health Interventions and Cervical Cancer Screening: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” J Med Internet Res, vol. 26, p. e58066, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Wen et al., “Effect of electronic health ( eHealth ) on quality of life in women with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials,” Cancer Medicine, vol. 12, no. 13, pp. 14252–14263, July 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Harder et al., “Enhancing Prostate Cancer Diagnosis: Artificial intelligence-Driven Virtual Biopsy for Optimal Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Targeted Biopsy Approach and Gleason Grading Strategy,” Modern Pathology, vol. 37, no. 10, p. 100564, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Kenner et al., “Artificial Intelligence and Early Detection of Pancreatic Cancer: 2020 Summative Review,” Pancreas, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 251–279, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Parikh et al., “Digital Health Applications in Oncology: An Opportunity to Seize,” J Natl Cancer Inst, vol. 114, no. 10, pp. 1338–1339, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Van Timmeren, D. Cester, S. Tanadini-Lang, H. Alkadhi, and B. Baessler, “Radiomics in medical imaging—‘how-to’ guide and critical reflection,” Insights Imaging, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 91, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Ozkan, A. T. Eruyar, O. O. Cebeci, O. Memik, L. Ozcan, and I. Kuskonmaz, “Interobserver variability in Gleason histological grading of prostate cancer,” Scandinavian Journal of Urology, vol. 50, no. 6, pp. 420–424, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. D. Pooler, D. H. Kim, C. Hassan, A. Rinaldi, E. S. Burnside, and P. J. Pickhardt, “Variation in Diagnostic Performance among Radiologists at Screening CT Colonography,” Radiology, vol. 268, no. 1, pp. 127–134, July 2013. [CrossRef]

- B. Ehteshami Bejnordi et al., “Diagnostic Assessment of Deep Learning Algorithms for Detection of Lymph Node Metastases in Women With Breast Cancer,” JAMA, vol. 318, no. 22, p. 2199, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Cherukuri et al., “Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Liquid Biopsy and Radiomics in Early-Stage Lung Cancer Detection: A Precision Oncology Paradigm,” Cancers, vol. 17, no. 19, p. 3165, Sept. 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Palmirotta et al., “Liquid biopsy of cancer: a multimodal diagnostic tool in clinical oncology,” Ther Adv Med Oncol, vol. 10, p. 1758835918794630, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. S. K. Mok et al., “Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial,” The Lancet, vol. 393, no. 10183, pp. 1819–1830, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Mazieres et al., “Immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced lung cancer and oncogenic driver alterations: results from the IMMUNOTARGET registry,” Annals of Oncology, vol. 30, no. 8, pp. 1321–1328, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Jenkins et al., “Plasma ctDNA Analysis for Detection of the EGFR T790M Mutation in Patients with Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer,” Journal of Thoracic Oncology, vol. 12, no. 7, pp. 1061–1070, July 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. Xu et al., “Deep learning and genome-wide association meta-analyses of bone marrow adiposity in the UK Biobank,” Nat Commun, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 99, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Berger and E. R. Mardis, “The emerging clinical relevance of genomics in cancer medicine,” Nat Rev Clin Oncol, vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 353–365, June 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Luong, “Top 5 AI For Medical Diagnosis.” Accessed: Nov. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.ominext.com/en/blog/top-5-best-ai-tools-for-medical-diagnosis.

- F. Alsharif, “Artificial Intelligence in Oncology: Applications, Challenges and Future Frontiers,” Int J. Pharm. Investigation, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 647–656, July 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Wu et al., “An integrated deep learning model for the prediction of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy with serial ultrasonography in breast cancer patients: a multicentre, retrospective study,” Breast Cancer Res, vol. 24, no. 1, p. 81, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Khan, R. Adam, P. Huang, T. Maldjian, and T. Q. Duong, “Deep Learning Prediction of Pathologic Complete Response in Breast Cancer Using MRI and Other Clinical Data: A Systematic Review,” Tomography, vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 2784–2795, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Bedrikovetski et al., “Artificial intelligence for pre-operative lymph node staging in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” BMC Cancer, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 1058, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Nardella et al., “Piloting a point-of-care patient education tool, MyCareGorithm, for multimodal pancreatic cancer treatment: A qualitative study.,” JCO Oncol Pract, vol. 21, no. 10_suppl, pp. 555–555, Oct. 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Walker, S. Samadi, J. Chen, T. N. Showalter, and C. Luminais, “Implementation of a digital multimedia tool for prostate cancer patient consultation.,” JCO, vol. 43, no. 5_suppl, pp. 345–345, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. Hardy-Abeloos et al., “Can a Digital Tool Improve the Understanding of Treatment Option for Patients With Head/Neck Cancer and Increase Providers’ Self-perceived Ability to Communicate With Patients?,” Practical Radiation Oncology, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. e138–e142, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhu, S. J. Ma, A. Farag, T. Huerta, M. E. Gamez, and D. M. Blakaj, “Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and Big Data in Radiation Oncology,” Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 453–469, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Baroudi et al., “Automated Contouring and Planning in Radiation Therapy: What Is ‘Clinically Acceptable’?,” Diagnostics, vol. 13, no. 4, p. 667, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Huang et al., “Auto-Segmentation and Auto-Planning in Automated Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer,” Bioengineering, vol. 12, no. 6, p. 620, June 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Peterson, S. E. Hoffe, M. E. Gamez, L. Harrison, and D. M. Blakaj, “Development and Implementation of Digital Health Tools in Radiation Oncology,” Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 323–346, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Q. Fan, Z. Fu, and D. Xiong, “Advantages and prospects of robotic surgery for colorectal cancer,” Intelligent Surgery, vol. 8, pp. 1–7, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Laga Boul-Atarass, C. Cepeda Franco, J. D. Sanmartín Sierra, J. Castell Monsalve, and J. Padillo Ruiz, “Virtual 3D models, augmented reality systems and virtual laparoscopic simulations in complicated pancreatic surgeries: state of art, future perspectives, and challenges,” International Journal of Surgery, vol. 111, no. 3, pp. 2613–2623, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Hashimoto, G. Rosman, D. Rus, and O. R. Meireles, “Artificial Intelligence in Surgery: Promises and Perils,” Annals of Surgery, vol. 268, no. 1, pp. 70–76, July 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Chow et al., “The Use of Wearable Devices in Oncology Patients: A Systematic Review,” The Oncologist, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. e419–e430, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Sun et al., “Wireless Monitoring Program of Patient-Centered Outcomes and Recovery Before and After Major Abdominal Cancer Surgery,” JAMA Surg, vol. 152, no. 9, p. 852, Sept. 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. H. Ward et al., “Feasibility of Fitness Tracker Usage to Assess Activity Level and Toxicities in Patients With Colorectal Cancer,” JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics, no. 5, pp. 125–133, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Royce, H. K. Sanoff, and A. Rewari, “Telemedicine for Cancer Care in the Time of COVID-19,” JAMA Oncol, vol. 6, no. 11, p. 1698, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Alpert et al., “Tele-Oncology Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Patient Experiences and Communication Behaviors with Clinicians,” Telemedicine and e-Health, vol. 30, no. 7, pp. e1954–e1962, July 2024. [CrossRef]

- “Navya Network.” Accessed: Nov. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.navyanetwork.com/.

- “OncoHealth,” OncoHealth. Accessed: Nov. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://oncohealth.us/.

- B. Jiang, M. Bills, and P. Poon, “Integrated telehealth-assisted home-based specialist palliative care in rural Australia: A feasibility study,” J Telemed Telecare, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 50–57, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Bonotis, P. Angelidis, and P. Natsiavas, “Usability and User Experience Testing of a Co-Designed Electronic Patient-Reported Outcomes App (‘MyPal for Adults’) for Palliative Cancer Care: Mixed Methods Study,” JMIR Hum Factors, vol. 12, pp. e57342–e57342, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Babicova, A. Cross, D. Forman, J. Hughes, and K. Hoti, “Evaluation of the Psychometric Properties of PainChek® in UK Aged Care Residents with advanced dementia,” BMC Geriatr, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 337, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. D. Bloom, M. Reblin, W.-Y. S. Chou, S. L. Beck, A. Wilson, and L. Ellington, “Online social support for cancer caregivers: alignment between requests and offers on CaringBridge,” Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 118–134, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Martin, D. Saredakis, A. D. Hutchinson, G. B. Crawford, and T. Loetscher, “Virtual Reality in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review,” Healthcare, vol. 10, no. 7, p. 1222, June 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Deming, K. J. Dunbar, J. F. Lueck, and Y. Oh, “Virtual Reality Videos for Symptom Management in Hospice and Palliative Care,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Digital Health, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 477–485, Sept. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Riley, C. Voisin, E. E. Stevens, S. Bose-Brill, and K. O. Moss, “Tools for tomorrow: a scoping review of patient-facing tools for advance care planning,” Palliat�Care, vol. 18, p. 26323524241263108, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Woo et al., “Understanding Gender-Specific Daily Care Preferences: Topic Modeling Study,” J Med Internet Res, vol. 27, p. e64160, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- “MyDirectives | Advance care planning that’s simple, secure, and always available.” Accessed: Nov. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mydirectives.com.

- Lozano-Lozano et al., “Mobile health and supervised rehabilitation versus mobile health alone in breast cancer survivors: Randomized controlled trial,” Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, vol. 63, no. 4, pp. 316–324, July 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Yanez et al., “Brief culturally informed smartphone interventions decrease breast cancer symptom burden among Latina breast cancer survivors,” Psycho-Oncology, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 195–203, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Saevarsdottir and S. L. Gudmundsdottir, “Mobile Apps and Quality of Life in Patients With Breast Cancer and Survivors: Systematic Literature Review,” J Med Internet Res, vol. 25, p. e42852, July 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Pariser, J. Brita, M. Harrigan, S. Capozza, A. Khairallah, and T. B. Sanft, “Delivery of Cancer Survivorship Education to Community Healthcare Professionals,” J Canc Educ, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 625–631, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Smith et al., “Cancer Survivorship at Stanford Cancer Institute,” J Cancer Surviv, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 53–58, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Richards, J. Corner, and J. Maher, “The National Cancer Survivorship Initiative: new and emerging evidence on the ongoing needs of cancer survivors,” Br J Cancer, vol. 105 Suppl 1, no. Suppl 1, pp. S1-4, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Bartholmae, M. V. Karpov, R. D. Doda, and S. Dodani, “SilverCloud mental health feasibility study: who will it benefit the most?,” Arch Med Sci, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 1576–1580, Sept. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Orasud, M. Uchiyama, I. Pagano, and E. Bantum, “Mobile Mindfulness Meditation for Cancer-Related Anxiety and Neuropathy: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial,” JMIR Res Protoc, vol. 13, p. e47745, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).