Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

08 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

While industrial scale dairy fermentations often employ pasteurized milk as the substrate, many farmhouse and traditional production practices apply raw milk derived from a variety of mammals. Certain artisanal production systems rely on the autochthonous microbiota of the milk, fermentation vessels, equipment and/or environment to initiate milk coagulation. While the technological properties of lactic acid bacteria associated with dairy fermentations are well described, their interactions with other organisms during fermentation and cheese ripening are poorly investigated. This study presents an overview of the microbial ecology of raw and pasteurized milk used in the production of cheeses. Furthermore, we report on the motility phenotype, lactose utilization ability and metabolic products of isolates of Hafnia paralvei and Hafnia alvei, and determine that these strains could grow in a non-antagonistic manner on plates with strains of Lactococcus lactis and Streptococcus thermophilus. As artisanal and farmhouse production systems are often associated with protected or regionally significant products, it is essential to develop a clear understanding of the microbial communities within and the complex relationships between the community members.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cheeses Evaluated in This Study

2.2. Metagenomic DNA Extraction

2.3. Metagenome Sequencing & Analysis

2.4. Culture-Based Analysis

2.5. Species Identification of Bacterial Isolates Using 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

2.7. Characterisation of Hafnia Isolates

2.7.1. Gas production Evaluation

2.7.2. Organic Acid Production

2.7.3. Growth Temperature Range Evaluation

2.7.4. Salt Tolerance

2.7.5. Microscopic Evaluation

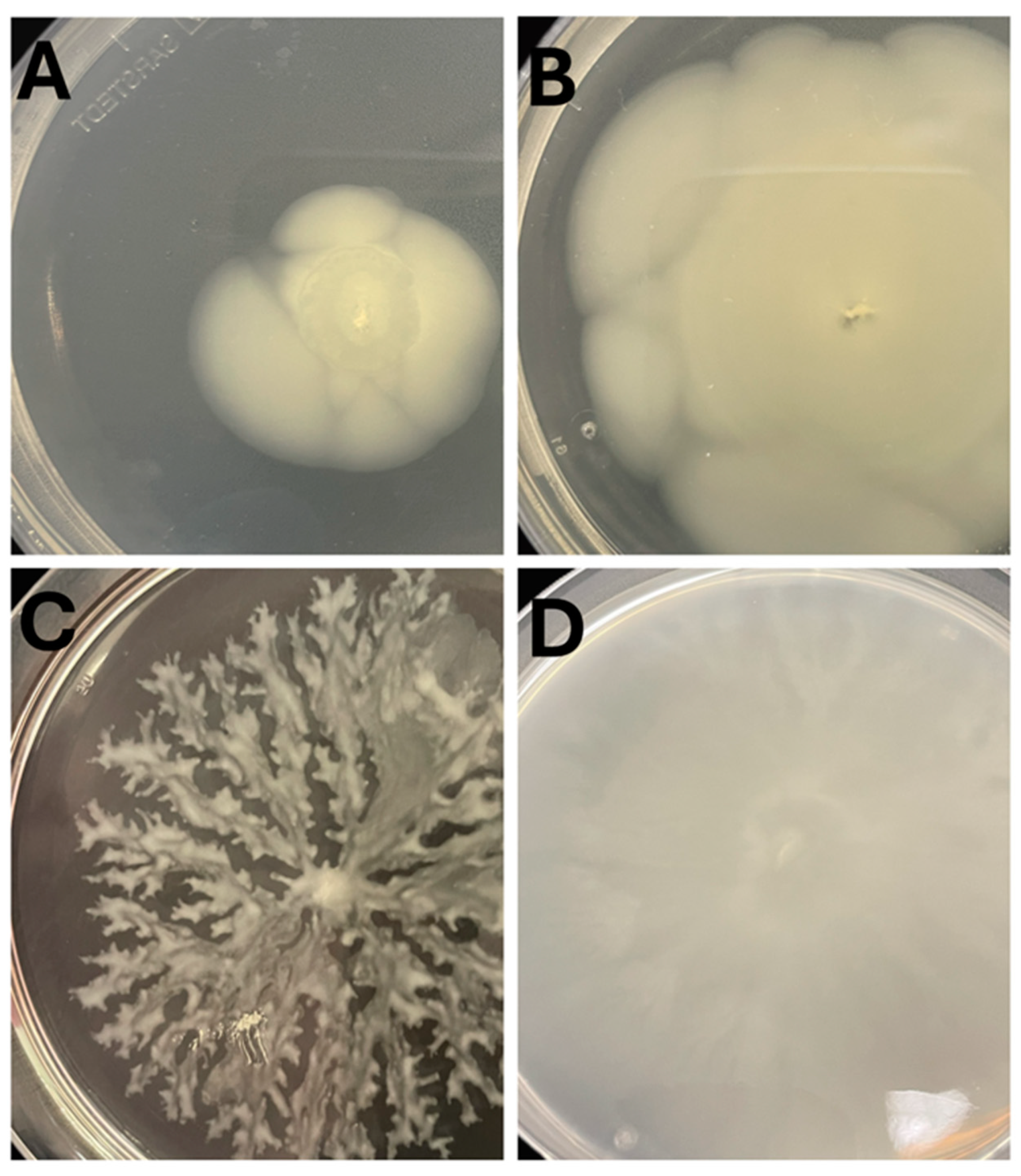

2.7.6. Motility Assays

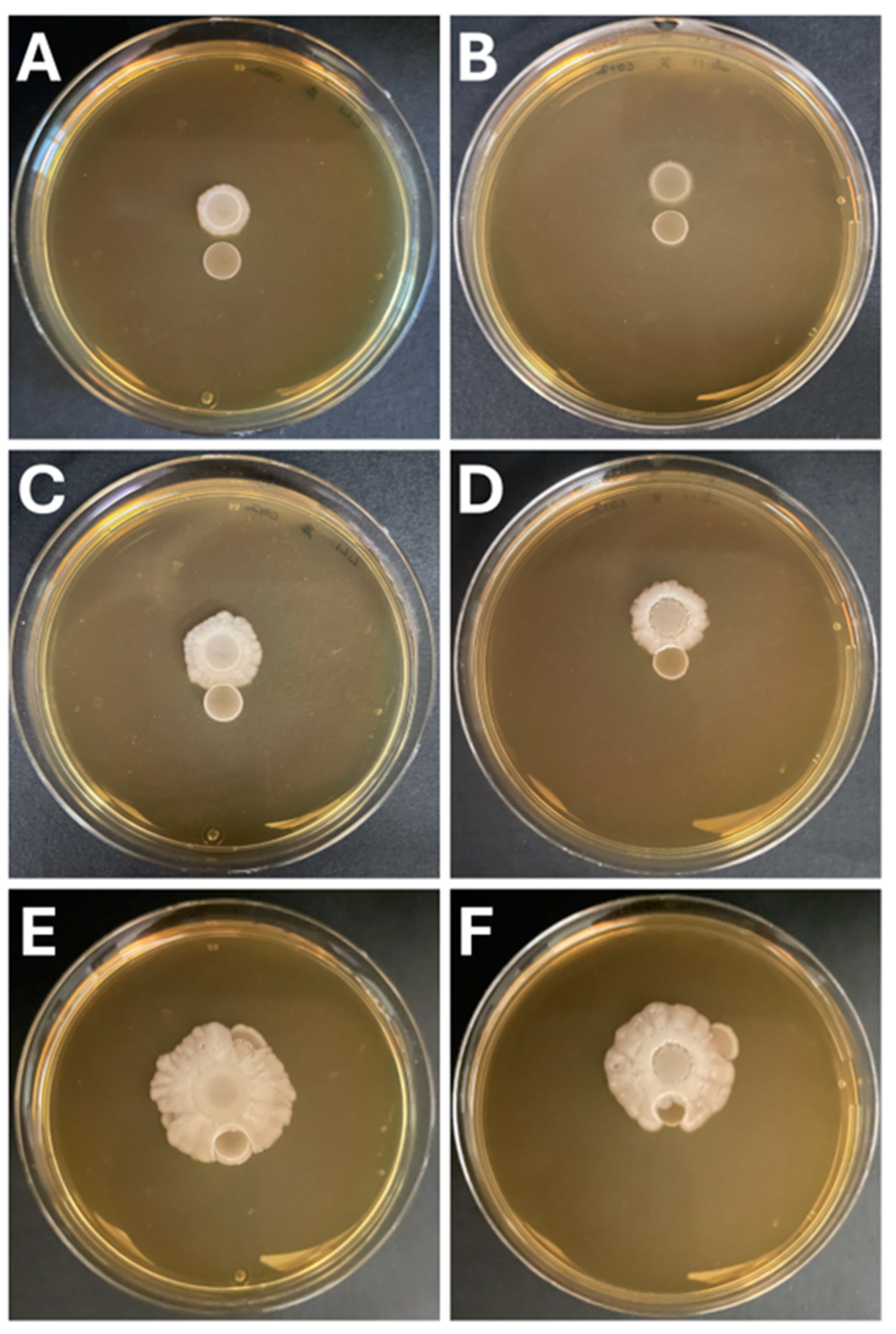

2.7.7. Hafnia and LAB Interaction Assays

3. Results

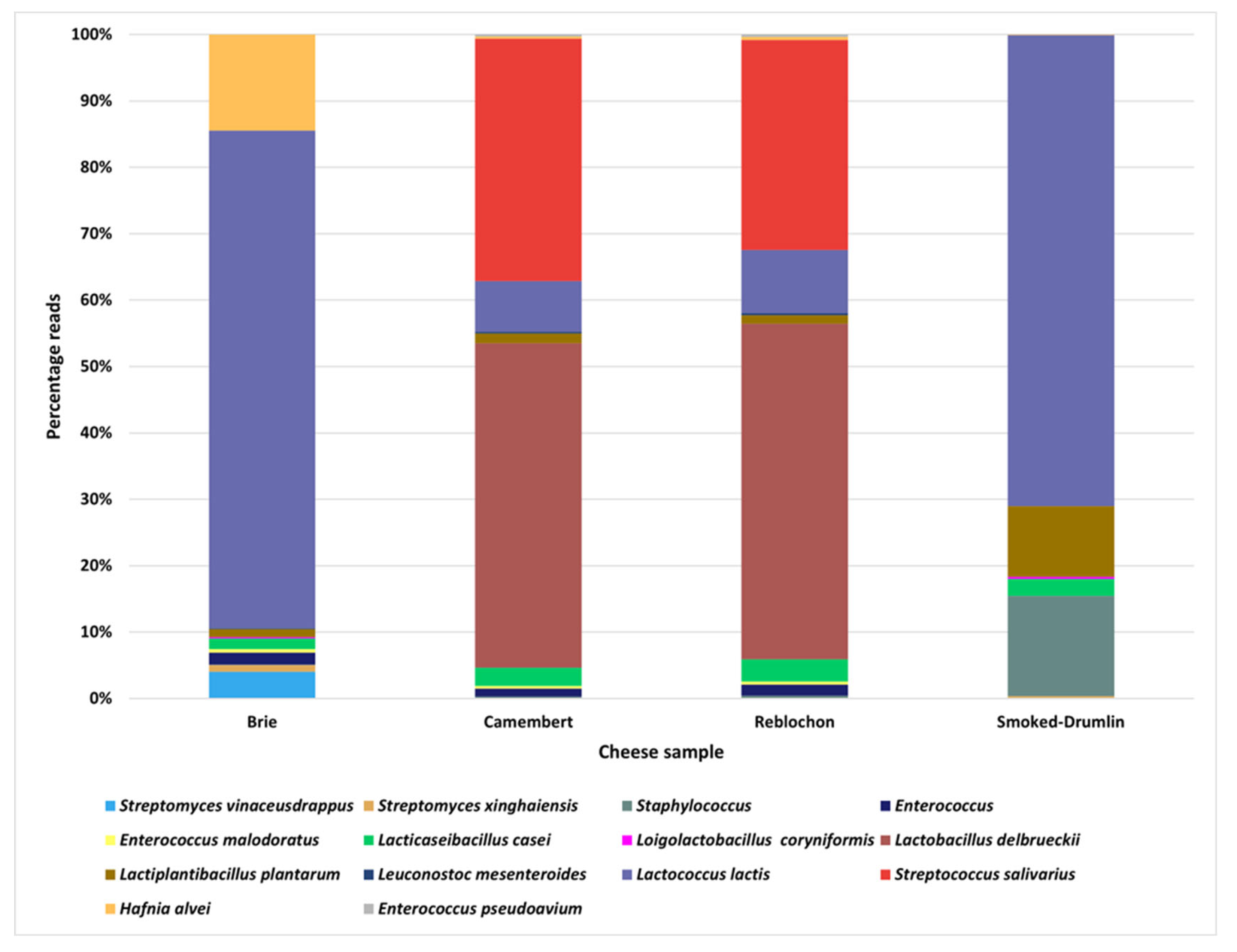

3.1. Metagenomic and Culture-Based Analysis of Four Raw-Milk Derived Cheeses

3.2. Thermophilic Culture-Based Analysis Increases Selection for Lactic Acid Bacteria

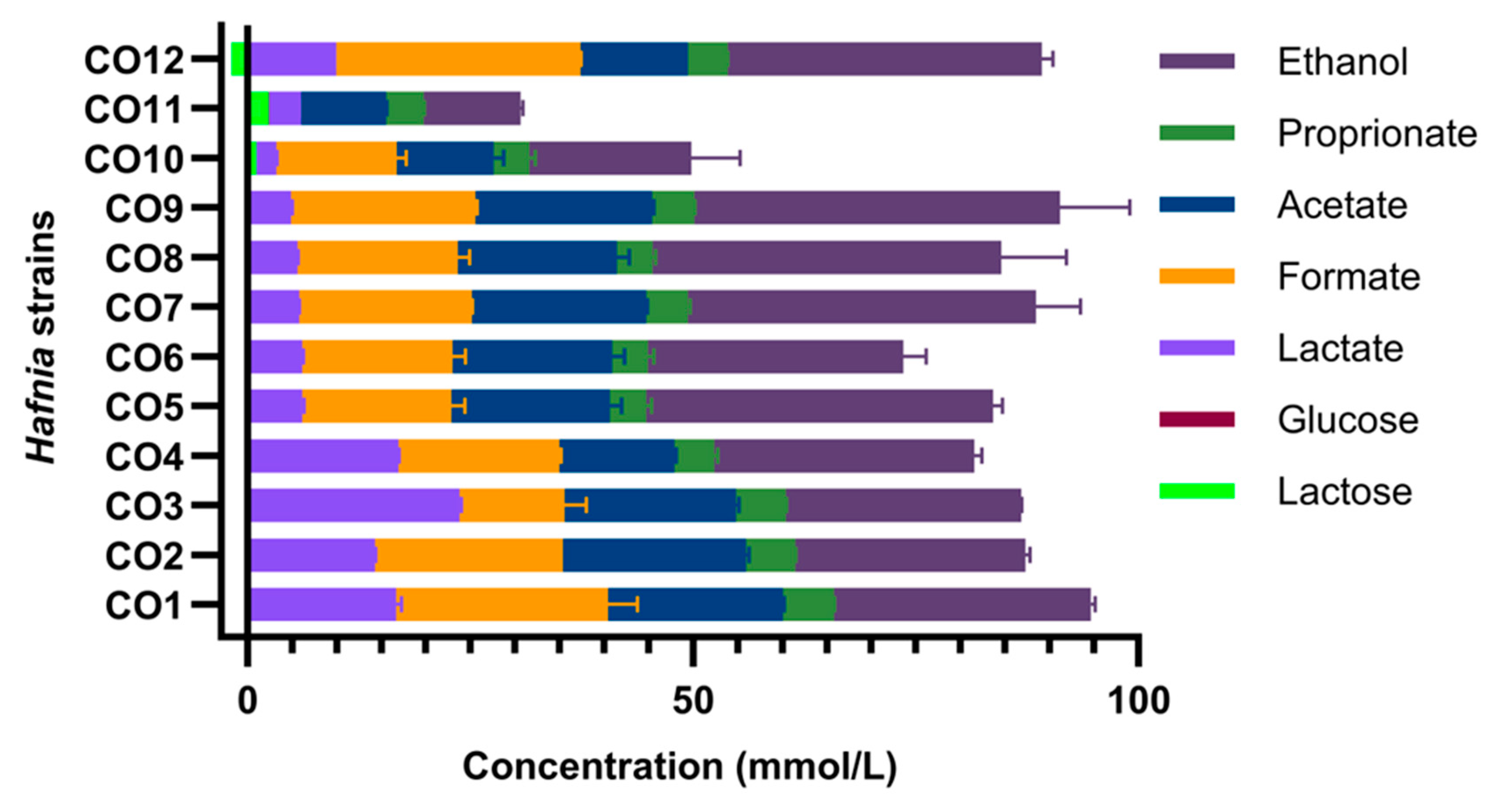

3.3. Hafnia Are Prevalent in Raw Milk Cheeses & Produce Gas from Lactose Metabolism

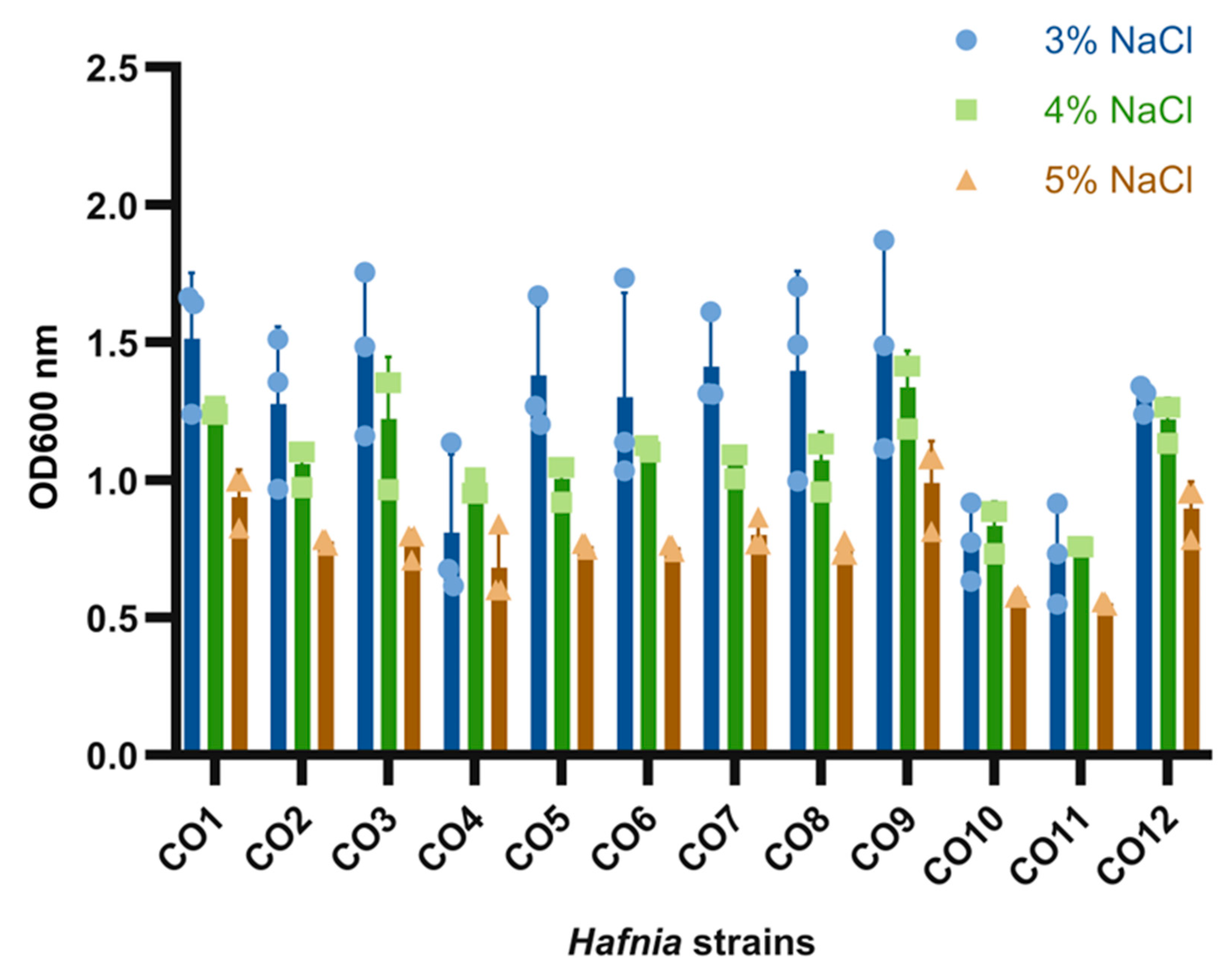

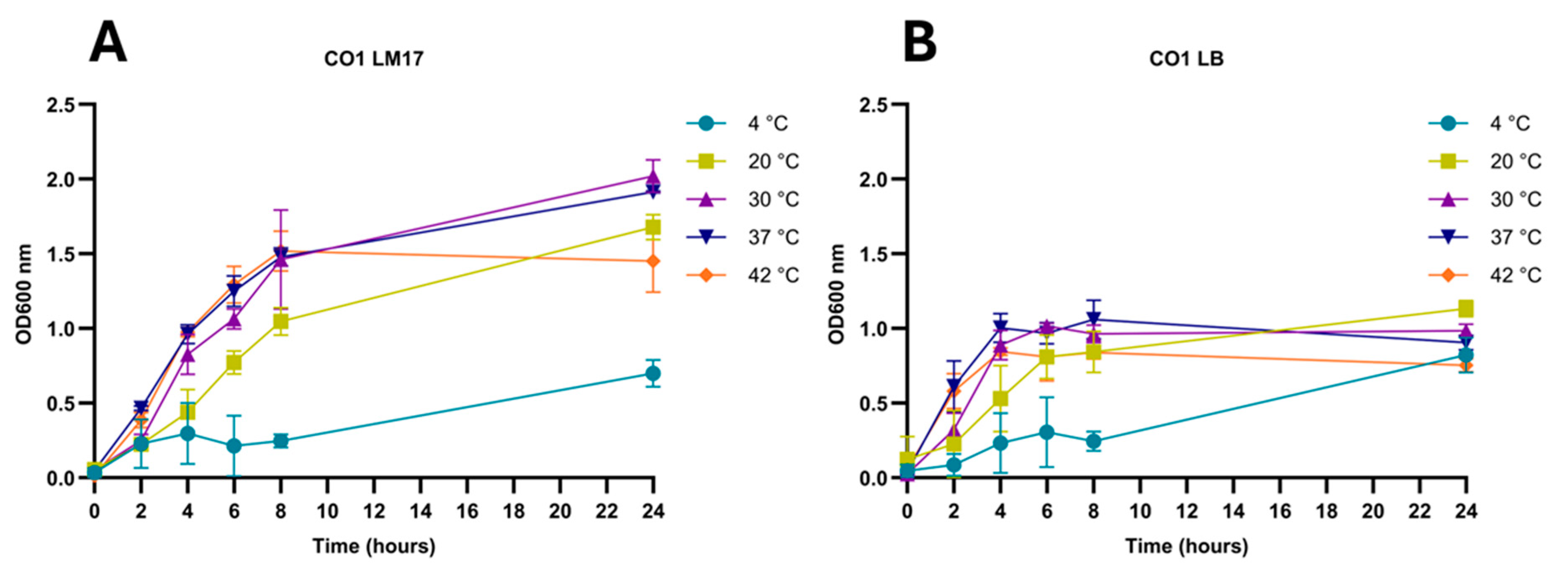

3.4. Hafnia Strains Are Tolerant to a Wide Range of Growth Conditions

3.5. Hafnia Strains Do Not Exhibit Antagonistic Interactions with Lactic Acid Bacteria

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kitto, C. Q2 2025 Irish & European Cheese Market Report | Ingredient Solutions 2025.

- Department of Agriculture, Food & the Marine Market Access: Dairy. Available online: http://www.marketaccess.agriculture.gov.ie/dairy/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Economics and Social - Dairy Industry Ireland. Available online: https://sitecore-prd-ne-cd01.azurewebsites.net/dairyindustryireland/our-dairy-story/economics-and-social (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Ireland Ranked Third for World’s Most Cheese Production per Capita. Available online: https://www.irishcentral.com/culture/food-drink/ireland-world-cheese-production (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- García-Díez, J.; Saraiva, C. Use of Starter Cultures in Foods from Animal Origin to Improve Their Safety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Production of Farmhouse Cheese. Teagasc Agric. Food Dev. Auth.

- Camargo, A.C.; De Araújo, J.P.A.; Fusieger, A.; De Carvalho, A.F.; Nero, L.A. Microbiological Quality and Safety of Brazilian Artisanal Cheeses. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2021, 52, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legese, M.H.; Asrat, D.; Mihret, A.; Hasan, B.; Mekasha, A.; Aseffa, A.; Swedberg, G. Genomic Epidemiology of Carbapenemase-Producing and Colistin-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae among Sepsis Patients in Ethiopia: A Whole-Genome Analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e00534-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.J.; Sands, K.; Thomson, K.; Portal, E.; Mathias, J.; Milton, R.; Gillespie, D.; Dyer, C.; Akpulu, C.; Boostrom, I.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance Genes in the Gut Microbiota of Mothers and Linked Neonates with or without Sepsis from Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1337–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, S.A.; Gyawali, R.; Aljaloud, S.O.; Krastanov, A.; Ibrahim, S.A. Cultivation Media for Lactic Acid Bacteria Used in Dairy Products. J. Dairy Res. 2019, 86, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, C.; Fontana, F.; Alessandri, G.; Mancabelli, L.; Lugli, G.A.; Longhi, G.; Anzalone, R.; Viappiani, A.; Duranti, S.; Turroni, F.; et al. Ecology of Lactobacilli Present in Italian Cheeses Produced from Raw Milk. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00139-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.C.; Malcata, F.X.; Silva, C.C.G. Lactic Acid Bacteria in Raw-Milk Cheeses: From Starter Cultures to Probiotic Functions. Foods 2022, 11, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchán, A.V.; Ruiz-Moyano, S.; Hernández, M.V.; Martín, A.; Lorenzo, M.J.; Benito, M.J. Characterization of Autochthonal Hafnia Spp. Strains Isolated from Spanish Soft Raw Ewe’s Milk PDO Cheeses to Be Used as Adjunct Culture. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 373, 109703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early Blowing in Raw Goats’ Milk Cheese: Gas Production Capacity of Enterobacteriaceae Species Present during Manufacturing and Ripening.

- Trmčić, A.; Chauhan, K.; Kent, D.J.; Ralyea, R.D.; Martin, N.H.; Boor, K.J.; Wiedmann, M. Coliform Detection in Cheese Is Associated with Specific Cheese Characteristics, but No Association Was Found with Pathogen Detection. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 6105–6120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, P.; Fernandez-Garcia, E.; Nunez, M. Caseinolysis in Cheese by Enterobacteriaceae Strains of Dairy Origin. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 37, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettera, L.; Dreier, M.; Schmidt, R.S.; Gatti, M.; Berthoud, H.; Bachmann, H.-P. Selective Enrichment of the Raw Milk Microbiota in Cheese Production: Concept of a Natural Adjunct Milk Culture. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1154508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unno, R.; Suzuki, T.; Osaki, Y.; Matsutani, M.; Ishikawa, M. Causality Verification for the Correlation between the Presence of Nonstarter Bacteria and Flavor Characteristics in Soft-Type Ripened Cheeses. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02894-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Kaehler, B.D.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.; Bolyen, E.; Knight, R.; Huttley, G.A.; Gregory Caporaso, J. Optimizing Taxonomic Classification of Marker-Gene Amplicon Sequences with QIIME 2’s Q2-Feature-Classifier Plugin. Microbiome 2018, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, F.; Longhi, G.; Alessandri, G.; Lugli, G.A.; Mancabelli, L.; Tarracchini, C.; Viappiani, A.; Anzalone, R.; Ventura, M.; Turroni, F.; et al. Multifactorial Microvariability of the Italian Raw Milk Cheese Microbiota and Implication for Current Regulatory Scheme. mSystems 2023, 8, e01068-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraffa, G. The Microbiota of Grana Padano Cheese. A Review. Foods 2021, 10, 2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenorio-Salgado, S.; Castelán-Sánchez, H.G.; Dávila-Ramos, S.; Huerta-Saquero, A.; Rodríguez-Morales, S.; Merino-Pérez, E.; Roa De La Fuente, L.F.; Solis-Pereira, S.E.; Pérez-Rueda, E.; Lizama-Uc, G. Metagenomic Analysis and Antimicrobial Activity of Two Fermented Milk Kefir Samples. MicrobiologyOpen 2021, 10, e1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigkrimani, M.; Bakogianni, M.; Paramithiotis, S.; Bosnea, L.; Pappa, E.; Drosinos, E.H.; Skandamis, P.N.; Mataragas, M. Microbial Ecology of Artisanal Feta and Kefalograviera Cheeses, Part I: Bacterial Community and Its Functional Characteristics with Focus on Lactic Acid Bacteria as Determined by Culture-Dependent Methods and Phenotype Microarrays. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzen, C.A.; Kleppen, H.P.; Holo, H. Lactococcus Lactis Diversity in Undefined Mixed Dairy Starter Cultures as Revealed by Comparative Genome Analyses and Targeted Amplicon Sequencing of epsD. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02199-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, C.; Hevia, A.; Foroni, E.; Duranti, S.; Turroni, F.; Lugli, G.A.; Sanchez, B.; Martín, R.; Gueimonde, M.; Van Sinderen, D.; et al. Assessing the Fecal Microbiota: An Optimized Ion Torrent 16S rRNA Gene-Based Analysis Protocol. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Peña, A.G.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME Allows Analysis of High-Throughput Community Sequencing Data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parlindungan, E.; McDonnell, B.; Lugli, G.A.; Ventura, M.; Van Sinderen, D.; Mahony, J. Dairy Streptococcal Cell Wall and Exopolysaccharide Genome Diversity. Microb. Genomics 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Alvarado, O.; Zepeda-Hernández, A.; Garcia-Amezquita, L.E.; Requena, T.; Vinderola, G.; García-Cayuela, T. Role of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Yeasts in Sourdough Fermentation during Breadmaking: Evaluation of Postbiotic-like Components and Health Benefits. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 969460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vuyst, L.; Leroy, F. Functional Role of Yeasts, Lactic Acid Bacteria and Acetic Acid Bacteria in Cocoa Fermentation Processes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 44, 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, M.; Bottari, B.; Lazzi, C.; Neviani, E.; Mucchetti, G. Invited Review: Microbial Evolution in Raw-Milk, Long-Ripened Cheeses Produced Using Undefined Natural Whey Starters. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.-P.; Landaud, S.; Lieben, P.; Bonnarme, P.; Monnet, C. Transcription Profiling Reveals Cooperative Metabolic Interactions in a Microbial Cheese-Ripening Community Composed of Debaryomyces Hansenii, Brevibacterium Aurantiacum, and Hafnia alvei. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameli, N.; Sioziou, E.; Bosnea, L.; Kakouri, A.; Samelis, J. Assessment of the Spoilage Microbiota during Refrigerated (4 °C) Vacuum-Packed Storage of Fresh Greek Anthotyros Whey Cheese without or with a Crude Enterocin A-B-P-Containing Extract. Foods 2021, 10, 2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hou, H. Redefining LuxI as a Metabolic Gatekeeper in Bacterial Spoilage of Refrigerated Turbot by Hafnia alvei H4. Food Microbiol. 2026, 134, 104949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.M.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, G.L.; Wang, J.Y.; Zhu, Y.H.; Liu, X.Y. Inhibition of Hafnia alvei H4 Biofilm Formation by the Food Additive Dihydrocoumarin. J. Food Prot. 2017, 80, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Eraclio, G.; Lugli, G.A.; Ventura, M.; Mahony, J.; Bello, F.D.; Van Sinderen, D. A Metagenomics Approach to Enumerate Bacteriophages in a Food Niche. In Bacteriophages; Tumban, E., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer US: New York, NY, 2024; Vol. 2738, pp. 185–199 ISBN 978-1-0716-3548-3. ISBN 978-1-0716-3548-3.

- Park, W.; Yoo, J.; Oh, S.; Ham, J.; Jeong, S.; Kim, Y. Microbiological Characteristics of Gouda Cheese Manufactured with Pasteurized and Raw Milk during Ripening Using Next Generation Sequencing. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2019, 39, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alessandria, V.; Ferrocino, I.; De Filippis, F.; Fontana, M.; Rantsiou, K.; Ercolini, D.; Cocolin, L. Microbiota of an Italian Grana-Like Cheese during Manufacture and Ripening, Unraveled by 16S rRNA-Based Approaches. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 3988–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraheim, H.K.; Madhi, K.S.; Baqer, G.K.; Gharban, H.A.J. Effectiveness of Raw Bacteriocin Produced from Lactic Acid Bacteria on Biofilm of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Vet. World 2023, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruta, S.; Murray, M.; Kampff, Z.; McDonnell, B.; Lugli, G.A.; Ventura, M.; Todaro, M.; Settanni, L.; Van Sinderen, D.; Mahony, J. Microbial Ecology of Pecorino Siciliano PDO Cheese Production Systems. Fermentation 2023, 9, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klištincová, N.; Koreňová, J.; Rešková, Z.; Čaplová, Z.; Burdová, A.; Farkas, Z.; Polovka, M.; Drahovská, H.; Pangallo, D.; Kuchta, T. Bacterial Consortia of Ewes’ Whey in the Production of Bryndza Cheese in Slovakia. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 78, ovaf047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantzen, C.A.; Kot, W.; Pedersen, T.B.; Ardö, Y.M.; Broadbent, J.R.; Neve, H.; Hansen, L.H.; Dal Bello, F.; Østlie, H.M.; Kleppen, H.P.; et al. Genomic Characterization of Dairy Associated Leuconostoc Species and Diversity of Leuconostocs in Undefined Mixed Mesophilic Starter Cultures. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, Y.B.; Jeong, M.S.; Kang, J.; Rhee, J.-K.; Kwon, J.; Kim, J.S.; Choi, J.-S.; Choi, H.-J.; et al. Complete Genome Sequence of a Commensal Bacterium, Hafnia alvei CBA7124, Isolated from Human Feces. Gut Pathog. 2017, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irlinger, F.; In Yung, S.A.Y.; Sarthou, A.-S.; Delbès-Paus, C.; Montel, M.-C.; Coton, E.; Coton, M.; Helinck, S. Ecological and Aromatic Impact of Two Gram-Negative Bacteria (Psychrobacter celer and Hafnia alvei) Inoculated as Part of the Whole Microbial Community of an Experimental Smear Soft Cheese. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 153, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Vivas, J.; Tapia, O.; Elexpuru-Zabaleta, M.; Pifarre, K.T.; Armas Diaz, Y.; Battino, M.; Giampieri, F. The Molecular Weaponry Produced by the Bacterium Hafnia alvei in Foods. Molecules 2022, 27, 5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, M.I.; Neagoe, D. Ștefan; Crăciun, A.M.; Moldovan, O.T. The Gram-Negative Bacilli Isolated from Caves—Sphingomonas Paucimobilis and Hafnia alvei and a Review of Their Involvement in Human Infections. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragacevic, L.; Tsibulskaya, D.; Kojic, M.; Rajic, N.; Niksic, A.; Popovic, M. Identification and Characterization of New Hafnia Strains from Common Carp (Cyprinus Carpio), Potentially Possessing Probiotic Properties and Plastic Biodegradation Capabilities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microbiology of Hafnia alvei Microbiology of Hafnia alvei.

- Qin, M.; Han, S.; Chen, M.; Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Niu, W.; Gao, C.; Wang, H.; Li, Y. Biofilm Formation of Hafnia paralvei Induced by C-Di-GMP through Facilitating bcsB Gene Expression Promotes Spoilage of Yellow River Carp (Cyprinus Carpio). Food Microbiol. 2024, 120, 104482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Z.; Yuan, C.; Du, Y.; Yang, P.; Qian, C.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, D.; Liu, B. Comparative Genomic Analysis of the Hafnia Genus Reveals an Explicit Evolutionary Relationship between the Species alvei and paralvei and Provides Insights into Pathogenicity. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla, D.; Acosta, F.; Bravo, J.; Grasso, V.; Real, F.; Vivas, J. Invasion and Intracellular Survival of Hafnia alvei Strains in Human Epithelial Cells. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 105, 1614–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litrenta, J.; Oetgen, M. Hafnia alvei: A New Pathogen in Open Fractures. Trauma Case Rep. 2017, 8, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Dámaso, D. Extraintestinal Infection Due to Hafnia alvei. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2000, 19, 708–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunthard, H.; Pennekamp, A. Clinical Significance of Extraintestinal Hafnia alvei Isolates from 61 Patients and Review of the Literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1996, 22, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidler, H.; Hudson, A.P. Reactive Arthritis Update: Spotlight on New and Rare Infectious Agents Implicated as Pathogens. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2021, 23, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sameli, N.; Samelis, J. Growth and Biocontrol of Listeria monocytogenes in Greek Anthotyros Whey Cheese without or with a Crude Enterocin A-B-P Extract: Interactive Effects of the Native Spoilage Microbiota during Vacuum-Packed Storage at 4 °C. Foods 2022, 11, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Shen, L.; Liu, X.; Xiao, N.; Jiao, N.; Liu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, S. Hafnia psychrotolerans Sp. Nov., Isolated from Lake Water. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 971–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisani, M.; Cecchini, M.; Fedrizzi, G.; Corradini, A.; Mancusi, R.; Tothill, I.E. Biosensing the Histamine Producing Potential of Bacteria in Tuna. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Product | Origin of animal milk | Texture | Milk state | Time post-production |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fleur du Maquis | Sheep | Soft | Pasteurized | 3 – 6 weeks |

| Brie | Cow | Soft | Raw milk | 1 week– 3 months |

| Saint Felicien | Cow | Soft | Pasteurized | 9 days |

| Mozzarella | Buffalo | Semi-soft | Pasteurized | 0 days (fresh) |

| Caciocavallo | Cow | Hard | Pasteurized | 3 – 6 months |

| Camembert | Cow | Soft | Raw milk | 1 week–3 months |

| Pecorino | Sheep | Semi-hard & hard | Pasteurized | 1 – 6 months |

| Smoked Drumlin | Cow | Hard | Raw milk | 1 – 3 weeks |

| Reblochon | Cow | Semi-soft | Raw milk | 1 – 3 weeks |

| Medium | TSA (cfu/ml) | LM17 (cfu/ml) | MRS (cfu/ml) | MacConkey (cfu/ml) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 30 °C | 37 °C | 30 °C | 37 °C | 30 °C | 37 °C | 37 °C |

| Cheese | (cfu/ml) | (cfu/ml) | (cfu/ml) | (cfu/ml) | |||

| Brie | 2.2×107 | 2×107 | 2.32×107 | 2.07×107 | 1.45×106 | 6.5×106 | 7.3×106 |

| Camembert | 2.3×106 | 3.9×106 | 5.9×106 | 4.9×106 | 6.1×106 | 5.8×106 | 4×105 |

| Smoked Drumlin | 5.4×106 | 4.4×106 | 2.95×107 | 1.53×107 | 4.5×106 | 2.8×106 | 0 |

| Reblochon | 3.7×107 | 1.4×107 | 3.13×107 | 2.9×107 | 1.73×107 | 1.14×107 | 8.4×105 |

| Hafnia strain | pH (24 hours) |

| CO1 | 5.3 ± 0.1 |

| CO2 | 5.2 ± 0.23 |

| CO3 | 5.4 ± 0.17 |

| CO4 | 5.4 ± 0.12 |

| CO5 | 5.3 ± 0.20 |

| CO6 | 5.3 ± 0.15 |

| CO7 | 5.4 ± 0.12 |

| CO8 | 5.3 ± 0.10 |

| CO9 | 5.2 ± 0.23 |

| CO12 | 5.2 ± 0.15 |

| S. thermophilus | pH (24 hours) |

| COSt11 | 4 ± 0 |

| L. lactis | pH (24 hours) |

| L.L1 | 3.8 ± 0.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.