1. Introduction

Lead (Pb) remains one of the most pervasive environmental toxicants worldwide, with extensive evidence demonstrating adverse health effects even at low exposure levels, particularly among children [

4,

5,

6,

7,

11,

15]. Despite global reductions in primary lead sources, legacy contamination in soils, water systems, and urban infrastructure continues to pose significant public health risks [

9,

41].

Climate change has emerged as a critical modifier of environmental exposure pathways. Increasing temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, floods, droughts, and extreme events can mobilize historically deposited contaminants, reshape exposure dynamics, and intensify existing health inequities [

10,

18,

19,

45]. However, research addressing the intersection of climate change, lead exposure, and health outcomes remains scattered across disciplinary silos.

Within this context, One Health frameworks emphasize the interconnectedness of human, environmental, and ecosystem health, offering a conceptual basis to integrate climate-driven exposure risks into public health practice [

21,

24,

29]. Yet, the extent to which climate change has been systematically incorporated into lead exposure research remains unclear.

This study aims to systematically map, synthesize, and interpret the scientific literature at the intersection of climate change, lead exposure, and health using integrated bibliometric and thematic approaches, identifying structural gaps, dominant research themes, and implications for One Health–oriented public health strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study employed a combined bibliometric and narrative review design. Bibliometric methods were used to map collaboration patterns, thematic structures, and intellectual linkages, while narrative synthesis contextualized findings within environmental health and One Health frameworks. This study was not designed as a systematic review and therefore did not follow PRISMA guidelines.

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

Literature searches were conducted on the Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed, covering publications from January 1990 to November 2025. Search terms combined climate-related keywords (“climate change”, “global warming”, “extreme weather”), lead-related terms (“lead exposure”, “lead contamination”; “lead poisoning”, “lead pollution”, “lead toxicity”, “Pb”), and health-related terms (“health”, “public health”, “environmental health”, “One health”, “ecosystem”). In addition to these searches, a snowball sampling strategy was employed to incorporate more studies.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible studies were peer-reviewed articles written in English that addressed lead exposure in environmental or health contexts and incorporated climate-related variables or processes. Editorials, conference abstracts, and non-peer-reviewed materials were excluded.

2.4. Bibliometric Analysis

Bibliometric analyses were conducted using VOSviewer, including co-authorship (authors and countries), keyword co-occurrence, citation, co-citation, and bibliographic coupling analyses. Thresholds were selected to balance network interpretability and coverage. The combined use of co-authorship, keyword co-occurrence, citation, co-citation, and bibliographic coupling analyses was intended to capture complementary dimensions of knowledge production, thematic convergence, and intellectual structure within the climate–lead–health research domain.

2.5. Thematic Synthesis and Citation Strategy

Bibliometric findings were complemented by qualitative thematic synthesis to identify climate-sensitive lead exposure, human health impacts, with emphasis on children and vulnerable populations, impacts on animals, wildlife, and ecosystems pathways and interpret results within a One Health framework.

In bibliometric reviews, the analyzed corpus constitutes the unit of structural analysis rather than a set of sources requiring individual citation.

Supplementary Materials include additional bibliometric visualizations (

Figures S1–S8) and the complete list of 89 references used in the bibliometric dataset (Supplementary References S1). Only the 45 most relevant references are cited in the main text to ensure clarity and focus.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Research

The final dataset included 89 peer-reviewed articles, showing a significant increase in publication volume after 2015. This increase coincided with growing recognition and interest in climate-environment-health interactions [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The main characteristics of the bibliometric corpus are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Co-Authorship and Disciplinary Fragmentation

Across the three databases, co-authorship analyses reveal low author continuity and limited collaborative density. This suggests that the research field on the connection between climate, lead, and health is episodic and not very integrated.

In Web of Science, 105 authors were identified, but only four met the minimum publication threshold. These authors formed a single small cluster with six links and a total link strength of 12 (

Figure 1), indicating localized collaboration concentrated in a very small core group.

Scopus showed a larger author universe (135 authors), yet the same pattern persisted: only four authors met the threshold and formed one small cluster with six links and a total link strength of 12 (

Figure S1). Broader coverage therefore did not translate into stronger collaborative integration.

PubMed displayed a contrasting structure: the network comprised 44 authors and all met the inclusion threshold, forming a single highly interconnected cluster with 55 links (

Figure S2). This denser structure likely reflects biomedical and public health authorship norms that favor multi-author and multi-institutional studies.

The results indicate a discrepancy in discipline: biomedical research communities exhibit stronger internal cohesion, while environmental and climate-oriented lead research demonstrate limited interconnectedness. Additional co-authorship visualizations are provided in the supplementary materials.

3.3. Co-Authorship Network by Countries

Country-level co-authorship patterns suggest limited international integration. Across databases, collaboration is concentrated in a small set of countries, indicating that climate-health research remains geographically siloed.

In Web of Science, only three countries were connected in a group of 21 countries (see

Figure 2). This structure reflects minimal cross-national collaboration and a concentration of outputs in a few settings.

Scopus showed a similar pattern, with marginally stronger but still limited collaboration (

Figure S3).

Across both databases, the United States consistently emerged as the central hub. Peripheral countries show limited direct collaboration with each other and rely largely on bilateral ties with dominant research centers.

These patterns suggest missed opportunities for comparative, context-sensitive research in regions with high lead burdens and high climate vulnerability. Expanded international collaboration is a priority for strengthening generalizability and equity-oriented evidence generation.

3.4. Keyword Co-Occurrence and Thematic Domains

Keyword co-occurrence mapping of author keywords indicates partial thematic convergence around lead exposure, environmental contamination, and health outcomes, with climate change acting primarily as a bridging concept rather than a central analytical driver (

Figure 3,

Table 2). In Scopus, the network (114 keywords; 11 meeting the threshold) forms three clusters with 19 links and a total link strength of 25, suggesting moderately structured themes spanning climate processes, lead exposure, and health. Web of Science shows greater thematic dispersion (10 items; four clusters; total link strength of 15;

Figure 4), while PubMed presents a compact, health-oriented thematic core (four items; one cluster; total link strength of nine;

Figure S4). Across databases, "climate change" generally functions as a unifying term rather than a pivotal organizing concept, thereby reinforcing the field's multidisciplinary yet somewhat disparate character. Key cross-database thematic domains are summarized in

Table 2.

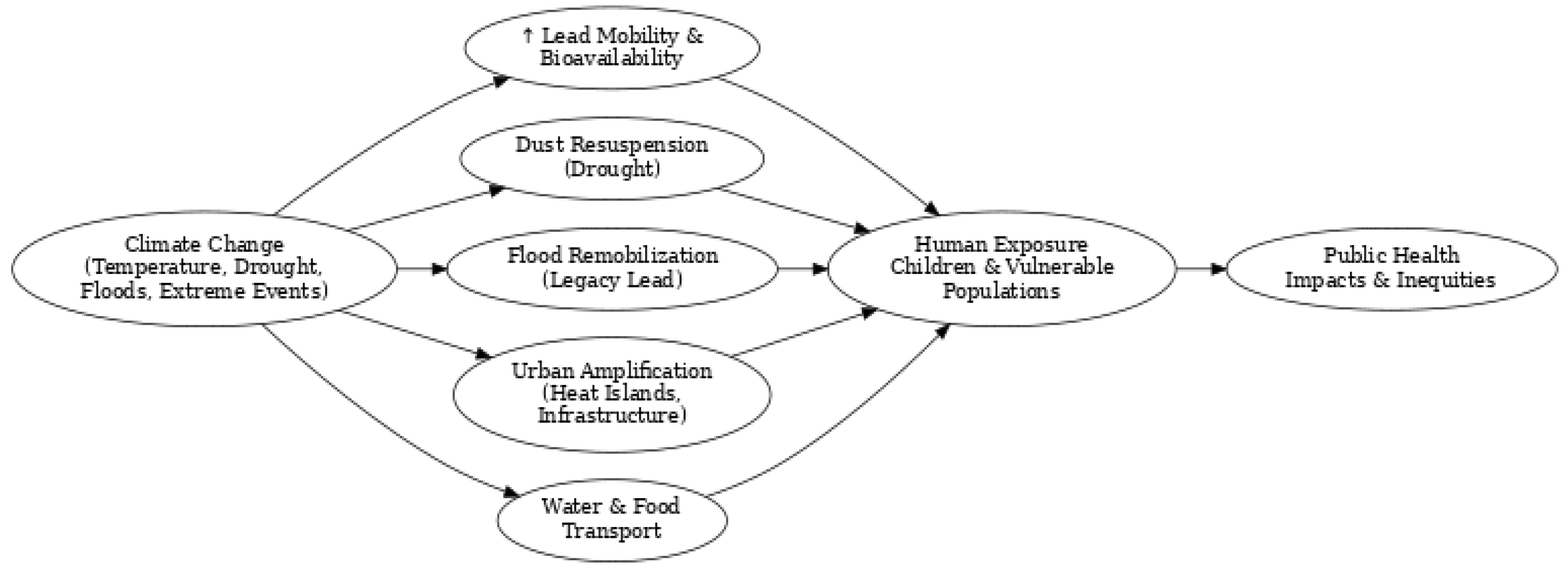

3.5. Climate-Sensitive Pathways of Lead Exposure

Five convergent climate-sensitive pathways of lead exposure were consistently identified across the literature and are summarized in

Table 3. These pathways are synthesized into an integrative One Health conceptual framework (

Figure 5):

Temperature-related increases in lead mobility and bioavailability [

24,

25,

26];

Drought-driven dust resuspension and airborne exposure, particularly in mining and arid regions [

21,

22,

23];

Flood-driven remobilization of legacy lead from contaminated soils and sediments [

18,

19,

20];

Urban amplification of exposure, associated with heat islands, aging infrastructure, and legacy contamination [

27,

28,

29];

Climate-mediated transport through water and food systems [

30,

31,

32].

Across these pathways, children and socioeconomically vulnerable populations were consistently identified as the most affected groups due to higher susceptibility and greater exposure to climate-sensitive environments [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

3.6. Citation, Co-Citation, and Bibliographic Coupling

Citation-based analyses provide insight into the intellectual integration of the climate–lead–health literature. Overall, document-level citation networks show limited connectivity, indicating that influential papers often develop in parallel rather than through sustained cross-citation,

In Web of Science, citation analysis identified 23 documents; 17 met the minimum citation threshold. These documents formed isolated nodes with no inter-document links (

Figure 6), suggesting an absence of a consolidated, mutually citing core.

Author-level citation analysis in Web of Science similarly revealed a small core: among 105 authors, only four met the inclusion threshold, forming one cluster with six links and total link strength of 12 (

Figure S5).

In Scopus, citation-by-author analysis was found to be even less robust. Among 135 authors, four met the threshold but no citation links were observed (

Figure S6), indicating minimal author-level citation cohesion in that database.

Co-citation analyses identified small epistemic communities centered on environmental toxicology and public health. In Web of Science, 13 authors met the minimum co-citation threshold, forming four clusters with 30 links and total link strength of 252 (

Figure 7). In Scopus, four authors met the threshold, forming two clusters with six links and total link strength of 25 (

Figure S7).

Bibliographic coupling revealed stronger shared reference bases despite limited direct collaboration. In Scopus, four authors formed a single bibliographic coupling cluster with six links and very high total link strength (114). The strong coupling suggests that a small group of authors share reference bases, which strengthens the evidence of parallel but not fully institutionalized research trajectories (

Figure 8;

Figure 9).

Collectively, these findings indicate that while authors often draw from similar foundational literature (bibliographic coupling), direct citation exchange and cumulative theory-building remain limited (citation and co-citation), reinforcing the field’s structural immaturity (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

The bibliometric results presented above provide quantitative evidence that, despite growing scientific attention, research on climate change and lead exposure remains structurally fragmented, with important implications for knowledge integration and public health action.

4.1. Fragmentation of Climate-Lead-Health Research

The combined author- and country-level co-authorship analyses reveal that research at the intersection of climate change, lead exposure, and health remains structurally fragmented [

14,

15,

16,

17]. While PubMed-indexed biomedical research demonstrates stronger collaborative cohesion, environmental and climate-focused studies indexed in Web of Science and Scopus show low network density and weak international integration. Although biomedical studies demonstrate internal cohesion, environmental and climate-focused research remains poorly integrated, which limits its translation into preventive public health strategies.

This fragmentation likely contributes to the observed disciplinary silos, limiting the development of comprehensive, climate-sensitive exposure frameworks. The dominance of a small number of authors and countries further suggests imbalanced knowledge production, potentially constraining the generalizability of findings to diverse geographic and socioeconomic contexts [

15,

30,

36,

40].

These patterns underscore the urgent need for transdisciplinary and transnational collaboration, consistent with a One Health approach, to better capture the complex interactions between climate processes, environmental lead mobilization, and population health outcomes [

37,

38,

39].

These co-authorship patterns quantitatively demonstrate the structural discontinuity characterizing research at the climate–lead–health interface. Only four recurring authors and a single small group are found in Web of Science and Scopus (see

Figure 1 and

Figures 1 and S1). This suggests that research efforts are mostly episodic and not well-established [

14,

15,

16].

Although PubMed displays a more cohesive collaborative structure (

Figure S2), this density reflects concentration within biomedical research rather than true interdisciplinary integration. Researchers focused on the environment and climate are not well connected to health-oriented author networks. This limits the development of comprehensive One Health approaches. These findings corroborate the broader bibliometric patterns observed in keyword and citation analyses, reinforcing the need for sustained cross-sectoral collaboration [

36,

40].

4.2. Climate Change as a Risk Multiplier for Lead Exposure

This review provides convergent evidence that climate change primarily acts as a risk multiplier, amplifying existing lead contamination rather than introducing new sources. As summarized in

Table 3 and illustrated in

Figure 4, climate-sensitive processes, including flood-driven remobilization, drought-related dust resuspension, and temperature-mediated increases in bioavailability, interact with legacy contamination, land use, and infrastructure conditions to shape dynamic exposure pathways. [

10,

11,

12,

13,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

4.3. Implications for Children and Environmental Justice

The disproportionate vulnerability of children is a consistent finding across epidemiological, toxicological, and environmental studies [

4,

5,

6,

7,

15]. Climate-amplified lead exposure therefore represents a critical environmental justice issue, particularly in low-income urban areas and regions affected by informal mining and inadequate environmental governance [

8,

9,

23,

33]. These findings reinforce the need for child-centered and equity-oriented climate adaptation policies that explicitly address legacy lead contamination.

4.4. One Health Perspective and Integrated Surveillance

Despite growing recognition of One Health approaches, human, animal, and ecosystem health studies remain limited integrated [

21,

33,

34,

35].

Figure 4 highlights how multispecies exposure pathways converge at the human–environment interface, underscoring the need for integrated, climate-sensitive surveillance systems.

4.5. Health Policy and Policy Implications

From a policy perspective, the pathways identified in

Table 3 underscore the need to integrate environmental surveillance systems capable of integrating climate variables and contaminant monitoring, and public health surveillance. Climate adaptation strategies that ignore legacy contaminants may inadvertently increase exposure risks. Interdisciplinary collaboration across environmental, climate, and health sectors is therefore essential to reduce future lead-related disease burdens [

1,

2,

3,

30,

31,

32].

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

This review integrates bibliometric and thematic methods to provide a structured synthesis of an emerging field. While bibliometric analyses have inherent limitations, convergence across multiple analytical dimensions supports the robustness of the findings [

28,

40]. These limitations are common to bibliometric studies and do not undermine the consistency of the patterns observed across databases and analytical approaches.

5. Conclusions

This bibliometric review demonstrates that research linking climate change, lead exposure, and health remains fragmented despite strong evidence that both climate change and lead independently pose major public health threats. The limited integration of these domains risks underestimating climate-amplified exposure scenarios, particularly for children and socioeconomically vulnerable populations. [

31,

35,

36,

40]

From an environmental and public health perspective, advancing climate-sensitive lead surveillance, exposure modeling, and prevention strategies is essential. A One Health approach integrating human, animal, and ecosystem health offers a robust framework to address the combined challenges of climate change, legacy contamination, and environmental injustice. Strengthening interdisciplinary collaboration and aligning research with public health policy needs will be critical to reducing the future burden of lead-related disease under a changing climate. [

24,

25,

26,

35,

36,

37,

38]

This review demonstrates that climate change functions as a critical risk multiplier for lead exposure, reshaping environmental pathways and reinforcing health inequities. Despite increasing scholarly attention, research remains fragmented across disciplines and geographies. Strengthening interdisciplinary collaboration, integrating climate-sensitive exposure pathways into surveillance systems, and adopting One Health–oriented policies are essential to reduce future lead-related disease burdens.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Author co-authorship network based on the Scopus database; Figure S2: Author co-authorship network based on the PubMed database; Figure S3: International co-authorship network by country based on Scopus records; Figure S4: Author keyword co-occurrence network based on PubMed records.; Figure S5: Author citation network based on the Web of Science database; Figure S6: Author citation network based on the Scopus database; Figure S7: Author co-citation network based on the Scopus database; Figure S8: Bibliographic coupling network of documents based on the Scopus; Figure S9: Bibliographic coupling network of authors (Web of Science); References S1: Complete list of 89 references included in the bibliometric dataset. Note: References [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45] are cited in the main text. References [46–89] are included for bibliometric completeness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.M.L.; methodology, M.M.L.; Formal analysis: M.M.L.; Writing—original draft: M.M.L.; Supervision: F.P.S.; Writing—review and editing: M.M.L.; F.P.S.; S.E.M.C.O.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

The authors confirm that no artificial intelligence tools were used to generate scientific content, interpret results, or draw conclusions. Language editing and improvements in clarity and grammar were performed by the authors.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript: Pb: lead; WoS: Web of Science; Scopus: Elsevier Scopus database; TLS: total link strength; PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; WHO: World Health Organization; UNEP: United Nations Environment Programme.

References

- McMichael, A.J. Climate change and human health. Eur. J. Public Health 2008, 18, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rylander, C.; Odland, J.Ø.; Sandanger, T.M. Climate change and environmental contaminants in the Arctic: Implications for human health. Glob. Health Action 2011, 4, 8452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanphear, B.P.; et al. Low-level environmental lead exposure and children’s intellectual function: An international pooled analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, R.; et al. Lead seasonality in humans, animals, and the environment. Environ. Res. 2019, 178, 108684. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, R.; et al. Pollution and health: A progress update. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e535–e547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, S.; et al. Impacts of climate change on the fate of heavy metals and radionuclides in soils through extreme weather events. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 909, 168388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csavina, J.; et al. A review on the importance of metals and metalloids in atmospheric dust and aerosol from mining operations. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 433, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartrem, C.; et al. Climate change, conflict, and resource extraction: Implications for the health of artisanal mining communities. Ann. Glob. Health 2022, 88, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, R.; et al. The urban lead burden in humans, animals, and the environment. Ambio 2021, 50, 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, G.; et al. Climate change and water-related infectious diseases. J. Water Health 2015, 13, 977–994. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, S.; et al. Climate change, extreme weather events, and human health. Public Health 2012, 126, 751–760. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, N.; et al. The 2020 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change. Lancet 2021, 397, 129–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.S.; et al. Climate change and global food systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2017, 42, 259–287. [Google Scholar]

- Romanello, M.; et al. The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Code red for a healthy future. Lancet 2021, 398, 1619–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patz, J.A.; et al. Climate change and global health: Quantifying a growing ethical crisis. EcoHealth 2007, 4, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, P.J.; et al. Pollution and global health—An agenda for prevention. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018, 126, 084501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinger, D.C. Very low lead exposures and children’s neurodevelopment. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2008, 20, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahran, S.; et al. Maternal exposure to lead and infant health. Environ. Res. 2017, 152, 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Nriagu, J.O. Global inventory of natural and anthropogenic emissions of trace metals to the atmosphere. Nature 1979, 279, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mielke, H.W.; Reagan, P.L. Soil is an important pathway of human lead exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 1998, 106, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Filippelli, G.M.; Laidlaw, M.A.S. The elephant in the playground: Confronting lead-contaminated soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 4426–4430. [Google Scholar]

- Laidlaw, M.A.S.; et al. Re-suspension of lead contaminated soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 12966–12974. [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger, D.C.; Needleman, H.L. Intellectual impairment and blood lead levels. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 500–502. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Lead Poisoning and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Global Chemicals Outlook II; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Landrigan, P.J.; et al. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. Lancet 2018, 391, 462–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandjean, P.; Landrigan, P.J. Neurobehavioural effects of developmental toxicity. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, G.; et al. Heavy metals and climate change: A systematic review. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 317, 120783. [Google Scholar]

- Miraglia, S.G.E.K.; et al. Climate change and extreme events: Impacts on health. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 1443–1454. [Google Scholar]

- Haines, A.; et al. Health and climate change: Policy responses. Lancet 2006, 367, 2101–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, J.P.; et al. Concerns over chemical exposure and climate interactions. Environ. Health 2017, 16, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Brulle, R.J.; Pellow, D.N. Environmental justice. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2006, 27, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullard, R.D. Environmental justice in the 21st century. Environ. Law 2001, 32, 1201–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Ebi, K.L.; et al. Health risks of climate change. BMJ 2020, 371, m4089. [Google Scholar]

- Frumkin, H.; et al. Climate change: The public health response. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. One Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Destoumieux-Garzón, D.; et al. The One Health concept. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Zinsstag, J.; et al. From “One Medicine” to “One Health”. Vet. Ital. 2005, 41, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lebov, J.F.; et al. Climate change and environmental exposures. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2018, 5, 179–192. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J.; et al. Planetary boundaries. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, R.A.; et al. The effect of future ambient air pollution. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.S.; et al. Planetary health: Protecting human health on a rapidly changing planet. Lancet 2013, 382, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanello, M.; et al. Climate change and health equity. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e669–e681. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Co-authorship network of authors based on the Web of Science database. The Web of Science dataset comprised 105 authors, of whom four met the minimum publication threshold and formed a single collaborative cluster (six links; total link strength = 12). The dense interconnections within this small core contrast with the low recurrence of authorship across the broader network, indicating episodic collaboration and a structurally fragmented research field at the climate–lead–health interface.

Figure 1.

Co-authorship network of authors based on the Web of Science database. The Web of Science dataset comprised 105 authors, of whom four met the minimum publication threshold and formed a single collaborative cluster (six links; total link strength = 12). The dense interconnections within this small core contrast with the low recurrence of authorship across the broader network, indicating episodic collaboration and a structurally fragmented research field at the climate–lead–health interface.

Figure 2.

International co-authorship network by countries based on the Web of Science database. Country-level co-authorship analysis identified 21 contributing countries, with only three meeting the minimum collaboration threshold, forming a single poorly connected cluster (three links; total link strength = 7). The sparse structure reflects limited international integration, with research outputs concentrated in a small number of countries and minimal cross-national collaboration in climate-related lead exposure research.

Figure 2.

International co-authorship network by countries based on the Web of Science database. Country-level co-authorship analysis identified 21 contributing countries, with only three meeting the minimum collaboration threshold, forming a single poorly connected cluster (three links; total link strength = 7). The sparse structure reflects limited international integration, with research outputs concentrated in a small number of countries and minimal cross-national collaboration in climate-related lead exposure research.

Figure 3.

Author–keyword co-occurrence network based on the Scopus database. The Scopus analysis (114 keywords; 11 meeting the minimum occurrence threshold) revealed three thematic clusters (19 links; total link strength = 25). The network indicates partial thematic convergence between climate-related drivers, lead exposure contexts, and health outcomes, while preserving cluster boundaries consistent with disciplinary segmentation.

Figure 3.

Author–keyword co-occurrence network based on the Scopus database. The Scopus analysis (114 keywords; 11 meeting the minimum occurrence threshold) revealed three thematic clusters (19 links; total link strength = 25). The network indicates partial thematic convergence between climate-related drivers, lead exposure contexts, and health outcomes, while preserving cluster boundaries consistent with disciplinary segmentation.

Figure 4.

Author–keyword co-occurrence network based on the Web of Science database. From 100 extracted keywords, 10 met the minimum occurrence threshold, forming four thematic clusters (12 links; total link strength = 15). The fragmented configuration highlights the coexistence of climate, environmental contamination, and health-related concepts, with limited integration across thematic domains.

Figure 4.

Author–keyword co-occurrence network based on the Web of Science database. From 100 extracted keywords, 10 met the minimum occurrence threshold, forming four thematic clusters (12 links; total link strength = 15). The fragmented configuration highlights the coexistence of climate, environmental contamination, and health-related concepts, with limited integration across thematic domains.

Figure 5.

Conceptual synthesis of climate-sensitive lead exposure pathways within a One Health framework. This figure integrates bibliometric findings with thematic evidence, illustrating how climate-driven processes (e.g., temperature increase, flooding, drought, and infrastructure stress) interact with legacy lead contamination to shape dynamic exposure pathways affecting humans, animals, and ecosystems.

Figure 5.

Conceptual synthesis of climate-sensitive lead exposure pathways within a One Health framework. This figure integrates bibliometric findings with thematic evidence, illustrating how climate-driven processes (e.g., temperature increase, flooding, drought, and infrastructure stress) interact with legacy lead contamination to shape dynamic exposure pathways affecting humans, animals, and ecosystems.

Figure 6.

Citation network of documents based on the Web of Science database. Among 23 documents, 17 met the minimum citation threshold; however, no citation links were observed between them. The absence of inter-document citation connections indicates a highly fragmented knowledge base, with limited cumulative referencing across studies addressing climate change and lead exposure.

Figure 6.

Citation network of documents based on the Web of Science database. Among 23 documents, 17 met the minimum citation threshold; however, no citation links were observed between them. The absence of inter-document citation connections indicates a highly fragmented knowledge base, with limited cumulative referencing across studies addressing climate change and lead exposure.

Figure 7.

Author co-citation network based on the Web of Science database. The co-citation analysis included 1,698 cited authors, of whom 13 met the minimum citation threshold, forming four clusters (30 links; total link strength = 252). Unlike co-authorship patterns, the denser co-citation structure suggests shared intellectual foundations across subfields, despite limited direct collaboration among authors.

Figure 7.

Author co-citation network based on the Web of Science database. The co-citation analysis included 1,698 cited authors, of whom 13 met the minimum citation threshold, forming four clusters (30 links; total link strength = 252). Unlike co-authorship patterns, the denser co-citation structure suggests shared intellectual foundations across subfields, despite limited direct collaboration among authors.

Figure 8.

Bibliographic coupling network of authors based on the Scopus database. The bibliographic coupling analysis identified four authors meeting the minimum threshold, forming a single cluster.

Figure 8.

Bibliographic coupling network of authors based on the Scopus database. The bibliographic coupling analysis identified four authors meeting the minimum threshold, forming a single cluster.

Figure 9.

Bibliographic coupling network of documents based on the Web of Science database. The bibliographic coupling analysis identified 12 authors meeting the minimum threshold, forming four clusters (34 links, and total link strength 48).

Figure 9.

Bibliographic coupling network of documents based on the Web of Science database. The bibliographic coupling analysis identified 12 authors meeting the minimum threshold, forming four clusters (34 links, and total link strength 48).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Bibliometric Dataset Included in the Review (n = 89).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Bibliometric Dataset Included in the Review (n = 89).

| Characteristic |

Description |

| Publication period |

1990–2025 |

| Total number of studies |

89 peer-reviewed articles |

| Databases |

Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed |

| Article types |

Original research articles, reviews |

| Main disciplinary areas |

Environmental sciences, public health, toxicology, climate science, epidemiology |

| Primary exposure focus |

Environmental lead (Pb) |

| Health outcomes addressed |

Neurodevelopmental effects, child health, chronic disease risk, population health |

| Climate-related variables |

Temperature increase, drought, flooding, extreme weather events |

| Geographical scope |

Global (with emphasis on North America, Europe, Arctic regions, and low- and middle-income countries) |

| Vulnerable populations |

Children, socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, urban populations |

| Main exposure media |

Soil, dust, air, water, food |

| Analytical approaches |

Environmental monitoring, epidemiological analysis, modeling studies, bibliometric analyses |

Table 2.

Major thematic domains identified in the bibliometric analysis of climate change, lead exposure, and health.

Table 2.

Major thematic domains identified in the bibliometric analysis of climate change, lead exposure, and health.

| Cluster |

Thematic domain |

Representative focus |

Representatives Keywords |

| Cluster 1: Human Health |

Lead exposure and human health |

Health impacts of low-level and chronic Pb exposure |

Children, neurodevelopment, blood lead levels, chronic exposure |

| Cluster 2: Environmental Processes |

Environmental contamination processes |

Environmental reservoirs and mobilization of lead |

Soil, sediments, dust, water, legacy contamination |

| Cluster 3: Climate Drivers |

Climate change drivers |

Climate-sensitive processes affecting Pb mobility |

Temperature rise, drought, floods, extreme events |

| Cluster 4: Urban and Socioeconomic Contexts |

Urban environmental health; Environmental justice and vulnerability |

Amplified exposure risks in urban settings; Disproportionate exposure and health burdens |

Heat islands, aging infrastructure, housing; Inequality, marginalized populations |

| Cluster 5: One Health |

One Health perspectives |

Human–animal–environment interactions |

One Health; animals; ecosystems; multispecies exposure |

Table 3.

Climate-Sensitive Pathways of Lead Exposure and Public Health Implications.

Table 3.

Climate-Sensitive Pathways of Lead Exposure and Public Health Implications.

| Pathway |

Climate-sensitive pathway |

Exposure

Mechanism |

Exposure route |

Public Health Implications |

| Increased lead mobility |

Temperature-related increases in Pb mobility |

Enhanced chemical mobility and bioavailability in soils |

Ingestion, inhalation |

Chronic low-level exposure; cumulative toxicity |

Flood-driven

remobilization

|

Extreme precipitation, floods |

Release of legacy lead from soils and sediments |

Ingestion, dermal contact |

Acute and chronic exposure following floods; water contamination |

| Dust resuspension |

Drought-driven dust resuspension, land degradation |

Airborne transport of contaminated particles |

Inhalation |

Elevated airborne Pb exposure; urban and mining communities |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Urban amplification |

Heat islands, infrastructure stress |

Aging housing, pipes, and contaminated urban soils |

Ingestion, inhalation |

Persistent exposure in urban populations; Persistent exposure in children |

| Water and food transport |

Altered hydrology and food systems |

Contaminated water and food chains |

Ingestion |

Population-wide exposure through water and diet |

Table 4.

Structural Indicators of Intellectual Integration.

Table 4.

Structural Indicators of Intellectual Integration.

| Analysis Type |

Database |

Nodes |

Clusters |

Links |

Total Link Strength |

Interpretation |

| Citation (Documents) |

Web of Science |

17 |

17 |

0 |

0 |

Parallel, non-cumulative literature |

| Citation (Documents) |

Scopus |

21 |

21 |

0 |

0 |

Parallel, non-cumulative literature |

| Citation (Authors) |

Web of Science |

4 |

1 |

6 |

12 |

Selective recognition |

| Citation (Authors) |

Scopus |

4 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

Fragmented influence |

| Bibliographic Coupling (Authors) |

Web of Science |

4 |

1 |

6 |

1,512 |

Shared conceptual base |

| Bibliographic Coupling (Authors) |

Scopus |

4 |

1 |

6 |

114 |

Moderate convergence |

| Co-Citation (Authors) |

Web of Science |

13 |

4 |

30 |

252 |

Moderate convergence |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).