1. Introduction

Pre-climacteric banana (

Musa acuminata AAA Group, Cavendish subgroup) is the most productive, an economically important chilling-sensitive, tropical fresh fruit, and is the most commercialized popular ‘model bananas’, consumed as staple food, worldwide [

1,

2]. The sweet banana “Cavendish” is a triploid (AAA), sterile that is propagated vegetatively and is considered an intraspecific hybrid of Musa acuminata (2n = 2x = 22, A-genome, n indicates gametic chromosome number) [

3]. The first comprehensive high-quality haplotype-resolved T2T genome was assembled for the triploid ‘Cavendish banana’ in 2023 [

4]. Banana bract disease (BBrMD) is highly damaging to banana plants and is caused by

Potyvirus, banana bract mosaic virus (BBrMV)[

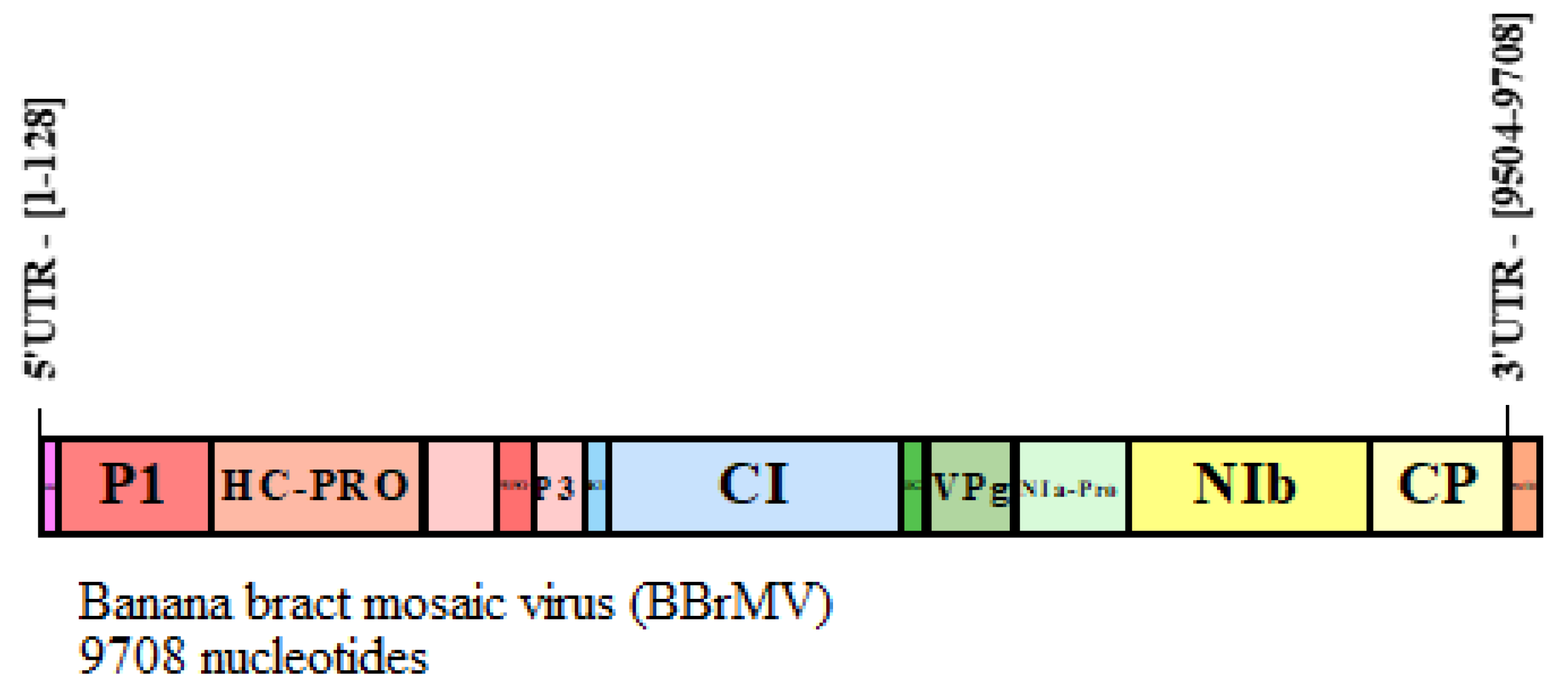

5]. Like other potyviruses, the BBrMV has a monopartite linear positive-sense, single-stranded−−(+) ssRNA genome of 9708 nucleotides. The genomic RNA has a single ORF. The genome has untranslated region (UTR) at both 5’ and 3′ end. The polyprotein is encoded by a single ORF that is cleaved into ≈10 mature proteins [

6].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) represent a novel class of widely distributed, endogenously encoded, tiny, non-coding, single-stranded RNA molecules. The miRNAs are involved in the regulation of many biological and physiological processes. The miRNAs are typically 19–24 nucleotides long, base pair imperfectly to complementary sequences in the 3’UTR of target mRNAs and possess a significant capacity to induce both mRNA degradation and translational repression. They are powerful regulators of many cellular processes, including apoptosis, growth, differentiation, development, homeostasis, host-pathogen interaction pathway and antiviral immune responses [

7].

Artificial microRNA (amiRNA) is a recent, safe and the most effective technology that induces the post-transcriptional gene silencing [

8]. The amiRNA approach has several advantages over traditional transgene-based viral-resistance approach gene silencing in eukaryotes. The amiRNA provides customizable and highly reversible method for inactivating selected target genes. The amiRNA approach is highly complement to viral genome editing approach in plants. The expression of virus-specific plant amiRNAs were first used to efficiently induce antiviral resistance against two RNA viruses. Thus, the small and highly efficient amiRNA cloned in expression vectors can induce high-efficiency gene silencing against invading viruses [

9,

10].

Identification and characterization of miRNAs in bananas constitute a fundamental first step necessary for uncovering mechanisms of host-virus interaction [

11]. In banana genome, 32 experimentally verified, high-confidence mature miRNA sequences have been identified and annotated for activating gene expression [

12]. The mature banana miRNAs were initially associated with different aspects of immune responses in regulating biotic and abiotic stressors [

13,

14,

15]. The mature banana miRNAs are master regulators, functional and localized to have potential binding sites in BBrMV genome.

This study thoroughly reviews and categorizes an integrative computational approach for combating BBrMV infection was used to identify binding sites of high-confidence mature banana miRNAs on the BBrMV +ssRNA-encoded mRNAs. The goal is to deploy a genome-wide screening approach to identify mature miRNAs using online miRNA bioinformatics web-based tools, for the identification of homologous amiRNAs. An integrative computational approach which is highly time-efficient for the prediction and analysis of effective, high-confident target sites of banana miRNAs predicted for targeting BBrMV genome. Identification of homologous amiRNAs is the first step to express in transgenic banana plants for creating resistance to BBrMV. Identification and transformation of short-listed banana miRNAs is the crucial step to induce amiRNA-mediated resistance in transgenic banana plants against BBrMV.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Banana MicroRNAs and BBrMV Genome Sequence

The available 32 experimentally verified high-confidence mature banana genome-encoded miRNAs sequences (mac-miR156-mac-5538) and (mbg-miR397-mbg-399) were selected (

Supplementary File S1)[12]. The reference full-length genome sequence of Banana bract mosaic virus (BBrMV) (NCBI Accession number MG758140; 9708 nucleotides) was retrieved from the NCBI GenBank database (

http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) for in-silico screening. The database was accessed on November 30, 2022 [

16].

2.2. RNA22 Algorithm

The RNA22 explores the use of a pattern-recognition approach for interactively exploring and visualizing highly significant target patterns [

17]. The RNA22 relies on evidence of biologically significant miRNA–mRNA interactions. RNA22 evaluates non-seed-based interaction, optimal site complementarity, maximum folding energy (MFE) for inferring targets and exploring their various attributes [

18]. The web-based tool is publicly accessible at

http://cm.jefferson.edu/rna22v1.0/ (accessed date 20 August 2022). The RNA22 algorithm had a specificity of 61% and sensitivity of 63%. We set the MFE for the miRNA–target hybrid to −15.00 Kcal/mol.

2.3. RNAhybrd Algorithm

The RNAhybrid algorithm is an easy-to-use fast and flexible publicly available online tool. The minimum free energy (MFE) can comprehensively or credibly evaluate energetically most favorable hybridization sites [

19]. The RNAhybrid was accessed at

http://bibiserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/rnahybrid on 31 October 2023). Site complementarity and seed-based interaction will lead to a more accurate prediction in the coding and non-coding regions.

2.4. TAPIR Algorithm

The TAPIR algorithm is the most reliable, rapid, and precise small RNA target analysis web-based server for predicting plant miRNA targets. The TAPIR employes a dual-method approach integrating both seed and sequence complementarity for its predictions. Analysis were performed using the TAPIR web server which is publically accessible at

http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/tapir (accessed on 19 July 2020) [

20]. Target prediction analysis used a maximal score of 9.0 and a free energy ratio of ≥0.2 as thresholds.

2.5. psRNATarget Algorithm

The psRNATarget algorithm uses complementary scoring (schema V2) to identify multiple target sites with inhibition patterns through a seed-matching and -scoring scheme [

21,

22]. The coding and non-coding sequences of the BBrMV genome were used to identify potential targets sites of banana miRNAs (

n=32) in the psRNATarget webserver (

http://plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget/) with an expectation score of 7.00 as cutoff.

2.6. Mapping of miRNAs-Target Interaction

Circos is powerful and highly specialized tool for creating sophisticated circular visualization of miRNA-target interaction network [

23].

2.7. RNAcofold Algorithm

RNAcofold computes the secondary structure upon miRNA: mRNA duplex based on the RNA-binding energy (ΔG) model and intermolecular base-pairing. RNAcofold concatenates the two RNA strands[

24].Potential RNA duplex sequences were input in the RNAcofold web server.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The predicted target sites of banana miRNAs were visualized using the R programming language [

25].

2.9. BBrMV Genome Annotation

Annotation of the coding and non-coding sequences in the BBrMV +ssRNA genome was performed with pDRAW32 version 1.1.147 (AcaClone software).

3. Results

3.1. Banana Locus-Derived miRNA-mRNA Interactive Pairs for the BBrMV Genome

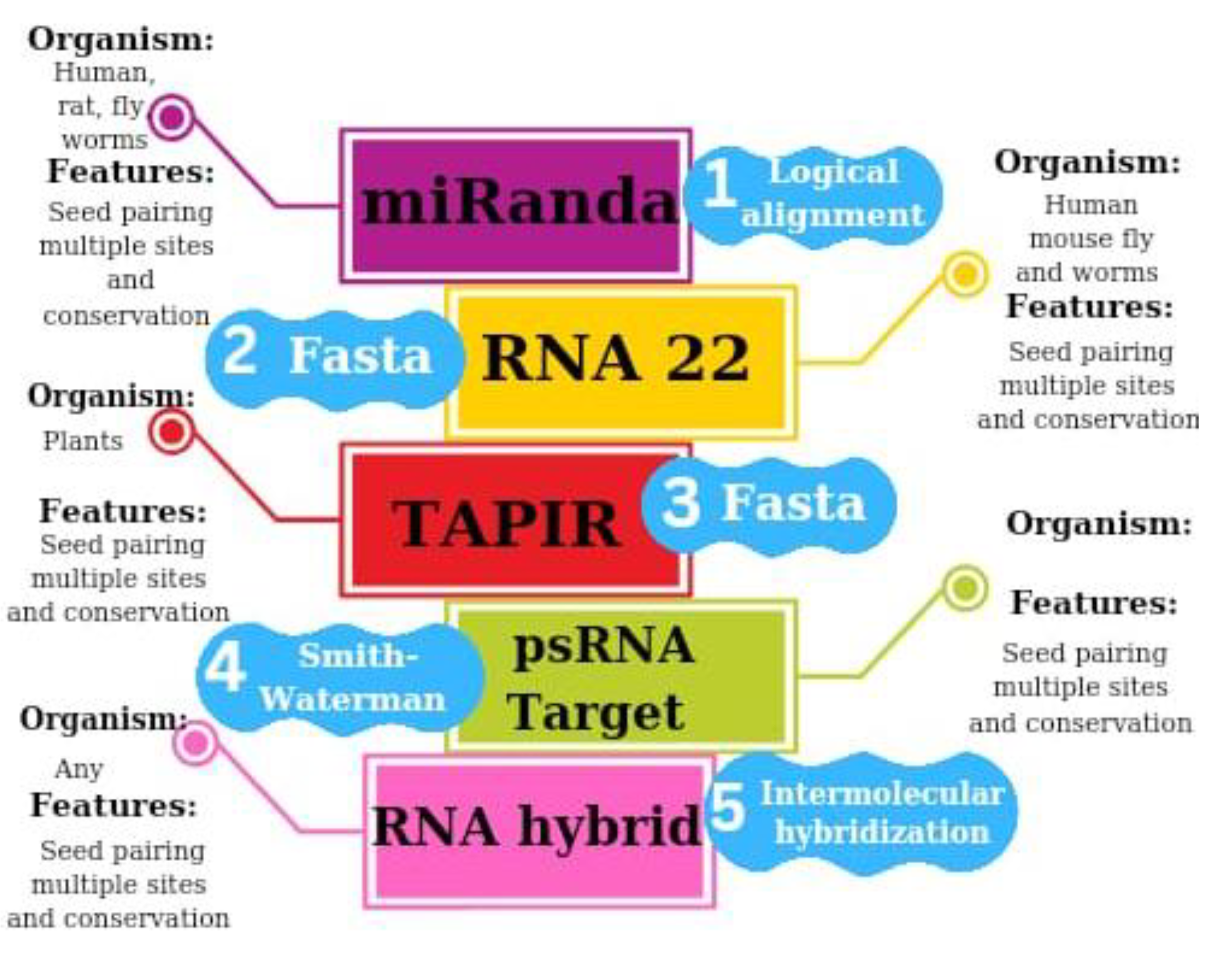

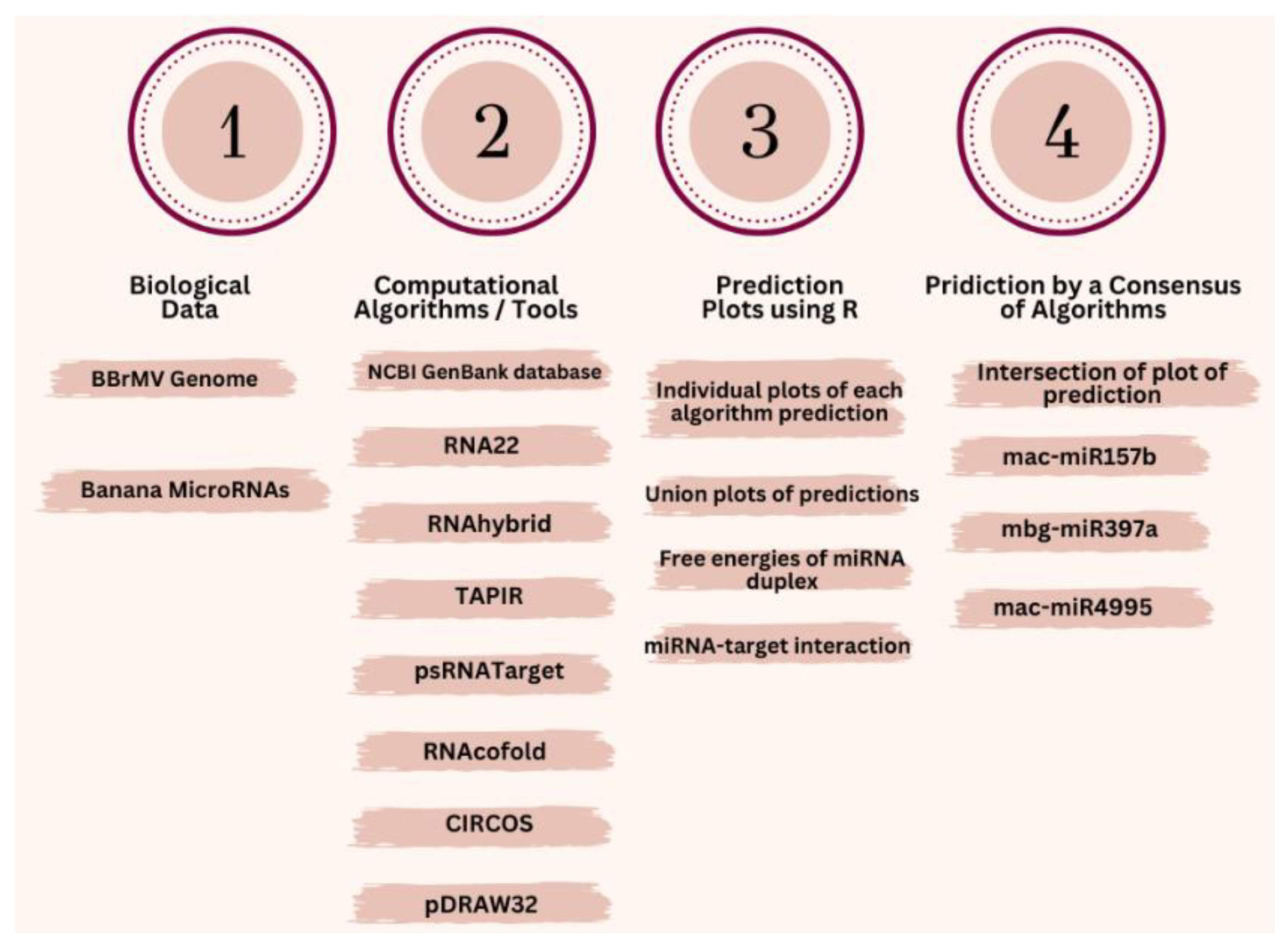

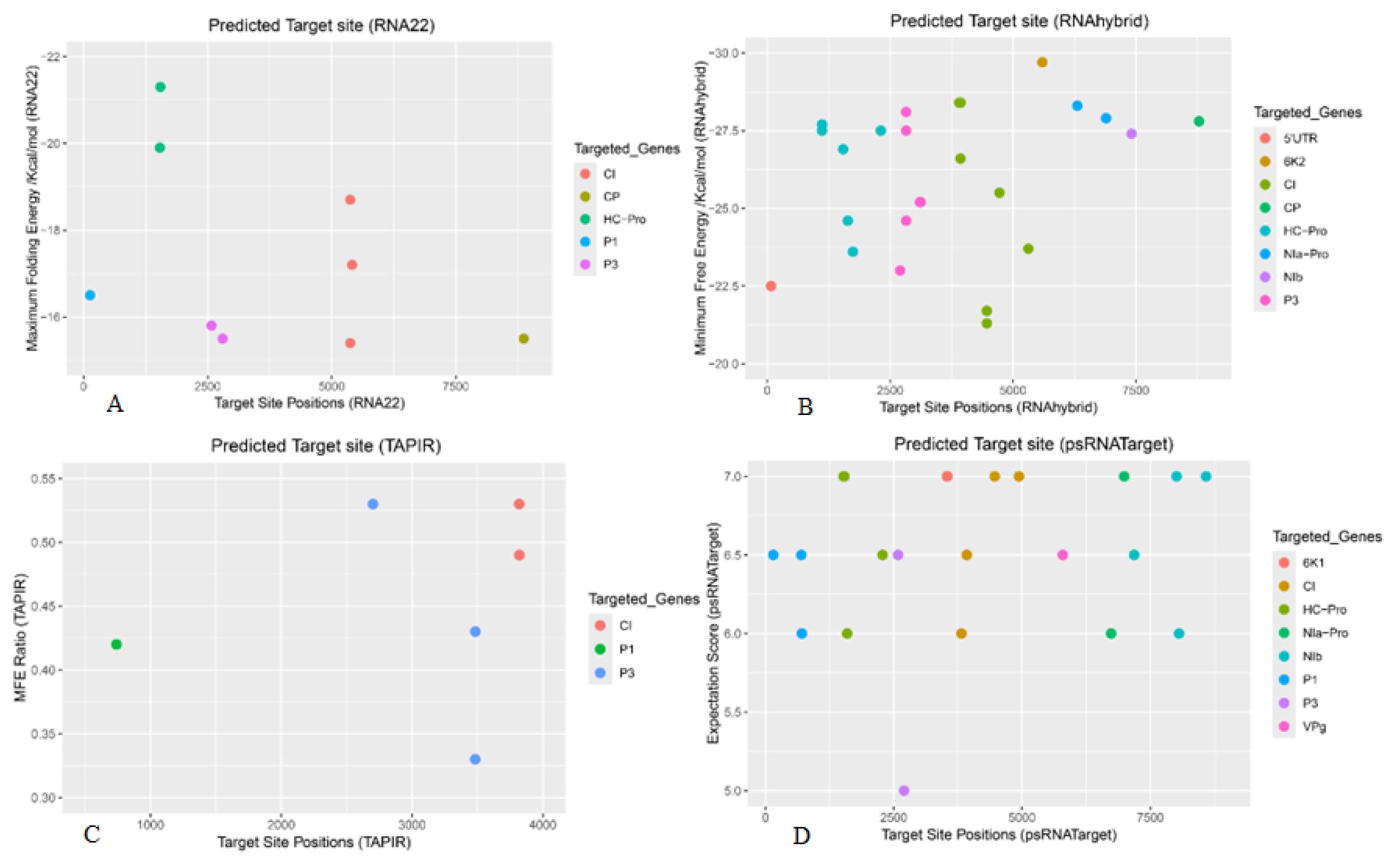

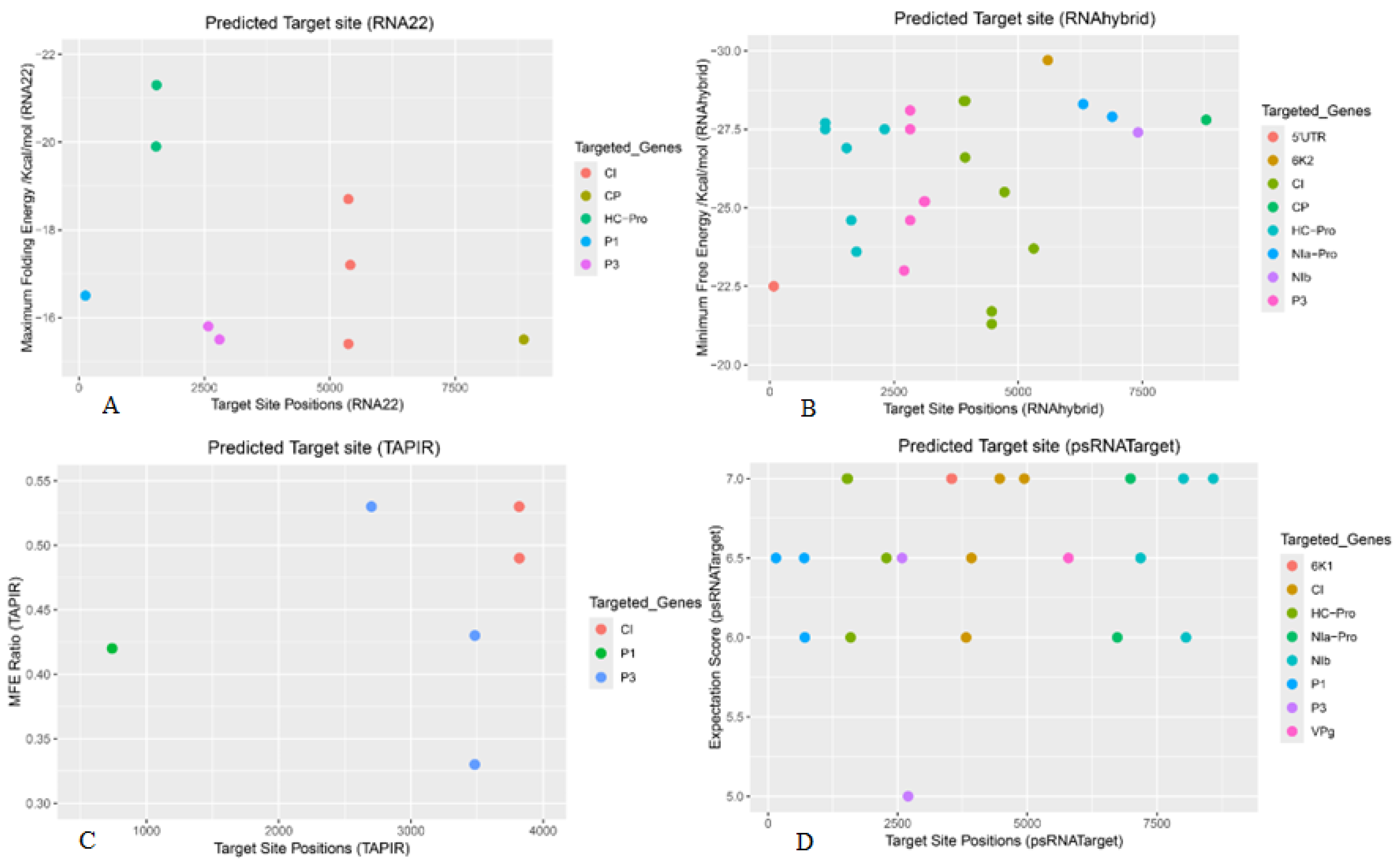

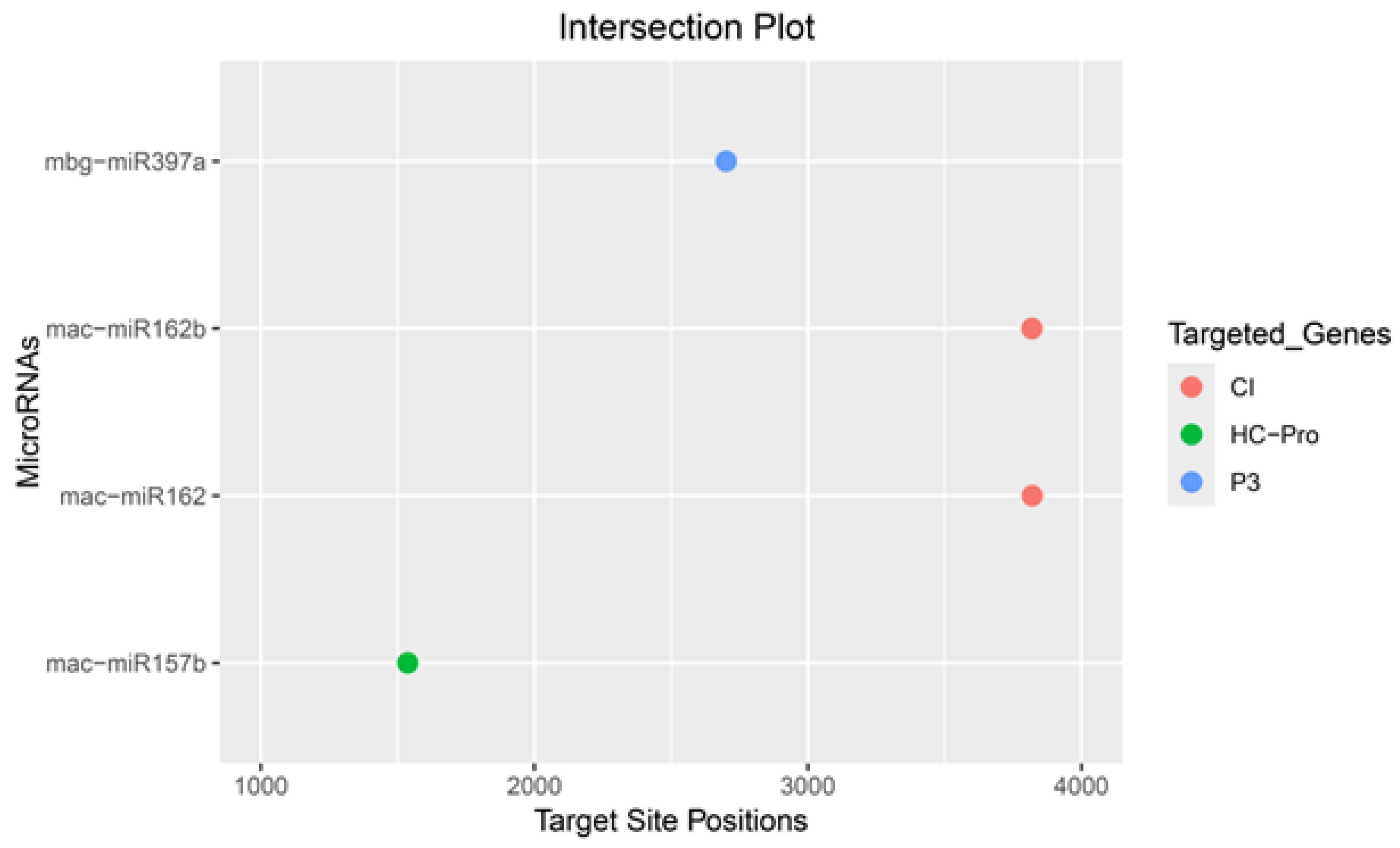

The miRNA identification boosts target prediction, which is the second bottleneck of computational approaches. Target prediction has suffered high false-positive rate. To identify the putative target sites of banana miRNAs, we used the most wide-spread tools: RNA22, RNAhybrid, psRNATarget, and TAPIR (

Figure 1). We provide a biological framework and computational proof of concept to identify binding sites of high confidence banana miRNAs that are predicted to silence the BBrMV +ssRNA-encoded mRNAs (

Figure 2). Our analysis provides novel biological insights into the banana genome-encoded miRNA promiscuity, affinity, miRNA-binding landscape, and complementary target sites on BBrMV ssRNA-encoded mRNAs. The BBrMV genome is a linear ssRNA molecule of 9708 nucleotides in length which is translated into one large polyprotein (

Figure 3).

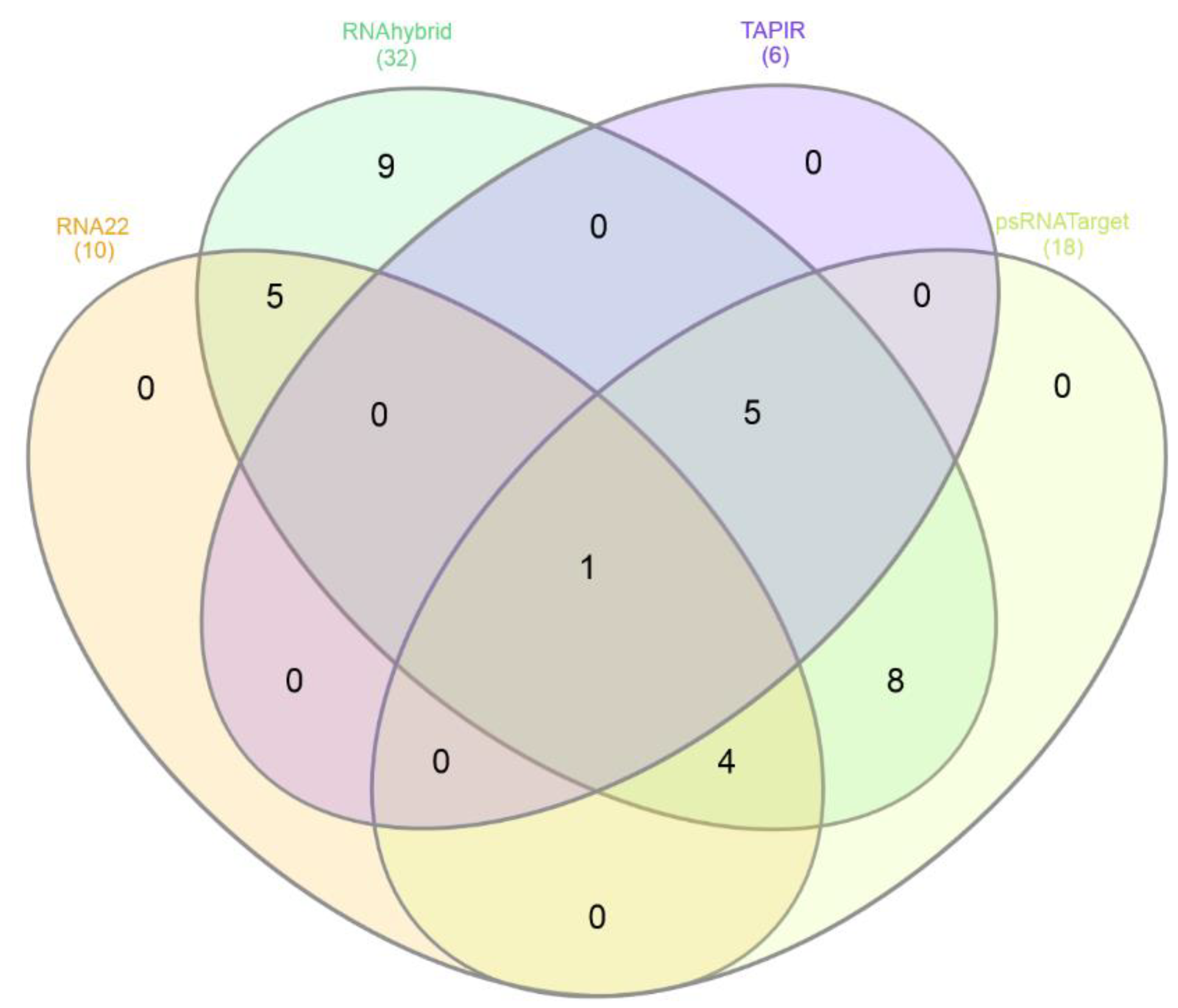

It allows unambiguous identification of imperfect multi-miRNAs seed binding sites. The sequence and location of the corresponding binding sites were predicted. Tools with higher number of binding sites were observed. Host miRNA targeting sites compared. Many of the banana-encoded miRNAs were highly promiscuous, targeting to many ORFs of the BBrMV genome. Host miRNAs bind to complementary site of the BBrMV +ssRNA-encoded mRNAs. The RNA22 algorithm predicted binding of potential 10 banana-encoded miRNAs to target 12 BBrMV genomic sites. The RNAhybrid predicted thirty-two high-affinity binding sites of banana miRNAs. The TAPIR algorithm identified 6 miRNA-target pairs. The psRNATarget algorithm predicted 18 mac-miRNAs targeting 30 BBrMV genomic sites as highly promising ‘cleavable targets’

Several banana locus-derived miRNAs identified by the in-silico workflow were observed to bind the BBrMV genome with promising banana miRNAs (mac-miR157b, mac-miR162, mac-miR162b and mbg-397a), which were predicted based on the consensus two algorithms. And mac-miR4995, was predicted to bind BBrMV +ssRNA-encoded mRNAs based on ‘union’ of all four tools (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Table 1,

supplementary Table S1 and supplementary File

supplementary File S2).

3.2. Predicted Targets for P1 ORF of BBrMV

The P1 ORF encodes a protease protein (P1) of the BBrMV genome (start site 129-1112 nucleotides), which is essential virus genome replication [

26]. A single mbg-miRNA (mbg-miR399a1) was identified as was located at unique site 128 by the RNA22 algorithm (

Figure 5A). While banana miRNAs (n=32) had no identified targets in the P1 coding region, with the RNAhybrid algorithm (

Figure 5B). As predicted by the TAPIR algorithm, P1 gene was targeted by mac-miR4995 at nucleotide position 740 (

Figure 5C). Four banana locus-derived miRNAs predicted to interact the P1 coding region were mac-miR156 (start site 697), mac-miR166 (709), mac-miR166c-3p (710) and mbg-miR397a (152), based on psRNATarget analysis (

Figure 5D,

Table 1,

Tables S1, S2, and File S2)

3.3. Helper-Component Proteinase (HC-Pro) of BBrMV Genome

The potyvirus HC-Pro ORF (1113-2483), consisting of 1370 bases, encodes a helper-component proteinase (HC-Pro) that is involved in movement, transmission, RNA silencing suppression, replication and symptom development [

27]. Analysis of the HC-Pro gene by the RNA22 tool predicted mac-miR157b (1537), and mac-miR160 (a, g-5p) (1546) as the most potential target mac-miRNAs (

Figure 5A). The RNAhybrid detected the following seven mac-miRNAs, mac-miR157b (1544), mac-miR160g (2310), mac-miR166 (b, c-5p) (1114), mac-miR172 (b, c) (1743), and mac-miR4995 (1638) (

Figure 5B). No binding site of banana miRNA was predicted with the TAPIR algorithm (

Figure 5C). The following six binding sites within banana miRNAs were identified: mbg-miR157b (1537), mbg-miR159 (2282), mac-miR162 (1593), mac-162b (1592), and mac-miR172 (b, c) (1522) by psRNATarget analysis (

Figure 5D,

Tables S1, S2, and File S2).

3.4. Membrane Associated Protein (P3) of BBrMV

The P3 ORF of the BBrMV genome is positioned between the coordinates 2484 and 2524) (1040 nucleotides) that encodes membrane-associated P3 protein. The P3 is thought to be essential for replication, movement, and pathogenicity [

28].

The RNA22 algorithm detected hybridization sites of the mac-miRNAs: mac-miR166 (b, c-5p) (2802) and mac-miR4995 (2579) (

Figure 5A). The RNAhybrid algorithm identified five predicted miRNAs: mac-miR156a-5p (3106), mac-miR159 (2825), mac-miR319 (c, m) from a common locus 2825, and mac-miR397a (2703) (

Figure 5B). Whereas the TAPIR software predicted three “potentially efficient” host plant miRNAs: mac-miR172 (b, c) (3484), and mbg-miR397a (2701) (

Figure 5C). By comparison, a single mbg-miRNA (mbg-miR397a) was identified that was located at nucleotide positions 2701 and 2584 with the psRNATarget tool (

Figure 5D,

Table 1,

Tables S1, S2, and File S2)

3.5. Banana miRNAs Targeting 6K1

The BBrMV 6K1 ORF (3525–3680 bp) (155 nucleotides) encodes a 6-kilodalton peptide 1 (6K1) involved in virus genome replication [

29]. No potential binding sites were identified to interact with the 6K1 region by the RNA22, RNAhybrid and TAPIR algorithms (

Figure 5A, B, C

). The psRNATarget tool employed in this study is considered as highly promising for achieving effective prediction of miRNA-target sites in the 6K1 region: mac-miR157b (3536), mac-miR162 (b) from common locus 3546 (

Figure 5D,

Table 1,

Tables S1, S2, and File S2)

3.6. Cylindrical Inclusion Protein (CI) of BBrMV Genome

The CI ORF of the BBrMV genome (3681-5582 bp, coordinates), encodes a multifunctional cylindrical inclusion protein (CI). The CI is necessary and sufficient for ATP binding and RNA helicase activity [

30]. The CI ORF gene was targeted by four predicted banana locus-derived miRNAs: mac-miR166 (5410), mac-miR166 (b, c-5p) (5372) and mac-miR166c-3p (5411) by RNA22 (

Figure 5A).

Six unique binding sites within banana locus-derived miRNAs (n=11) were predicted by RNAhybrid analysis mac-miR156 (a-3p, h-3p) (3908), mac-miR156 (d, g) (4468), mac-miR157b-5p (4468), mac-miR160 (a, g-5p) (3934), mac-miR162 (4725), mac-miR162a (5313), mac-miR162b (4725) and mbg-miR399a1 (3932) (

Figure 5B). Two unique banana mac-miRNAs were identified by TAPIR: mac-miR162 and mac-miR162b from common locus position 3820 (

Figure 5C). By comparison, the psRNATarget identified six miRNAs: mac-miR156(4467), mac-miR156a-5p (4941), mac-miR156 (a-3p, h-3p) (3923), mac-miR162 and mac-miR162b from common locus position 3820 (

Figure 5D,

Table 1,

Tables S1, S2, and File S2).

3.7. Banana miRNAs Targeting 6K2

The BBrMV 6K2 ORF (5583-5741) (158 bases) encodes a 6K2 multifunctional protein which is essential for long-distance movement, virus infection, formation of RE-derived complexes, plant resilience to drought and symptom development [

31]. No target binding sites of banana miRNAs were detected in the 6K2 coding region with the RNA22, TAPIR, psRNATarget algorithms (

Figure 5A, C, D). Using the RNAhybrid algorithm to find predicted targets, only mac-miR164e had predicted hybridization site at nucleotide coordinate 5597 in the 6K2 ORF region (

Figure 5B,

Table 1,

Tables S1, S2, and File S2).

3.8. Viral Protein Genome-Linked (VPg) of the BBrMV

The BBrMV VPg (5742-6311) (569 nucleotides) encodes a viral protein genome linked. The (VPg) functions as a virulence determinant and is associated with host’s translation initiation factor (eIF4E) to initiate replication and translation of +ssRNA genome [

32]. A single mac-miRNA (mac-miR157b) was detected at genomic position 5793 by the psRNATarget algorithm (

Figure 5D). No banana miRNAs were predicted with the RNA22, RNAhybrid and TAPIR tools (

Figure 5A, B, C,

Table 1,

Tables S1, S2, and File S2).

3.9. Nuclear Inclusion-a Protease (NIa-Pro) of BBrMV Genome

The potyvirus NIa-Pro ORF 6312–7040 (728 nt) encodes the nuclear inclusion-a protease (NIa-Pro). NIa-Pro is required for cleavage of polyprotein, virus infection cycle, RNA-binding and host proteome [

28,

33]. No candidate miRNAs were detected to have target sites in the NIa-Pro region, as analyzed by RNA22 and TAPIR tools (

Figure 5A, C). The RNAhybrid identified the binding of mac-miRNAs: mac-miR169h (6895), mac-miR166 and mac-miR166c-3p from same locus position 6895 (

Figure 5B). The NIa-Pro ORF was also predicted to be targeted by three mac-miRNAs through psRNATarget analysis: mac-miR156 (a-3p, h-3p) (6735), and mac-miR162a (6989) (

Figure 5D,

Table 1,

Tables S1, S2, and File S2).

3.10. Nuclear Inclusion-b Protease (NIb) of BBrMV Genome

The NIb of the BBrMV genome (7041-8600) (1559 nucleotides) encodes nuclear inclusion-b protease which is required for translocation activity and also interacts with NIa [

34]. NIb is also referred as RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) that catalyzes the synthesis of viral RNA [

35,

36]. A single binding site of mbg-miRNA (mbg-miR399a) was identified at locus position 7415 by the RNAhybrid algorithm (

Figure 5B). No banana miRNAs were identified that have predicted potential for interacting with the NIb coding region with the RNA22 and TAPIR algorithms (

Figure 5 A, C).

Based on psRNATarget analysis, five miRNAs were predicted to target the NIb ORF: mbg-miR159 (8586), mac-miR319c (7184), mac-miR319m (7183), mac-miR166c-5p (8010) and mac-miR4995 (8059) (

Figure 5D,

Table 1,

Tables S1, S2, and File S2).

3.10.1. Coat Protein (CP) of BBrMV Genome

The polyprotein of the BBrMV genome contains a specific domain that encodes coat protein (CP), located between the coordinates 8601 and 9500 (899 nucleotides). The CP participates in the encapsidation of potyviral ssRNA virion genome assembly [

27,

37]. The RNA22 algorithm predicted hybridization of mbg-miR399a at nucleotide position 8868 (

Figure 5A). The RNAhybrid predicted the mac-miRNAs, mac-miR167 (c, d) at common locus position (start site 8786) (

Figure 5B). No predicted target binding sites were identified in the BBrMV genome by the TAPIR and psRNATarget algorithms (

Figure 5 C, D,

Table 1,

Tables S1, S2, and File S2).

3.10.2. Consensus and Unique miRNAs Prediction

In this study, we investigated the interaction of BBrMV +ssRNA-encoded mRNA on host plant miRNAs for locating the consensus high-confidence binding sites using a combination of algorithms. And mac-miR4995, was predicted to bind BBrMV +ssRNA-encoded mRNAs based on ‘union’ of all four tools (

Figure 4 and

Figure 6)

Of the 32 targeting mature banana miRNAs investigated, the binding efficacy of top 4 miRNAs with the BBrMV genome were evaluated by the promising results of two algorithms. Two computational algorithms—RNAhybrid and TAPIR—predicted hybridization of mac-miR162 and mac-miR162b at unique nucleotide position 3819 (target gene CI of the BBrMV genome).

Of the 4 consensus miRNAs, two banana miRNAs (mac-miR157b and mbg-miR397a) at unique positions (1537 and 2701 respectivly), were identiifed to have common predicted high-affinity binding sites by three of the four algorithms (

Figure 7,

Table 2 and

Table 3). Among the 32-banana genome-encoded miRNAs interrogated, one banana miRNA homolog, mbg-miR397a was detected as a highly promising and horbored high affinity binding site at the consensus nucleotide position 2701 (target gene P3). Notably, mac-miR157b and mbg-miR397a showed a higher degree of similarity for MFE assessment. By comparison, psRNATarget estimated an expectation score of 5.00 for mbg-miR397a. The ‘cleavage’ efficacy of the banana consensus miRANs were assessed against BBrMV by RNAi-mediated suppression[

38]. Finally, the mbg-miR397a was predicted to interact with the P3 gene of BBrMV (

Figure 7,

Table 2 and

Table 3).

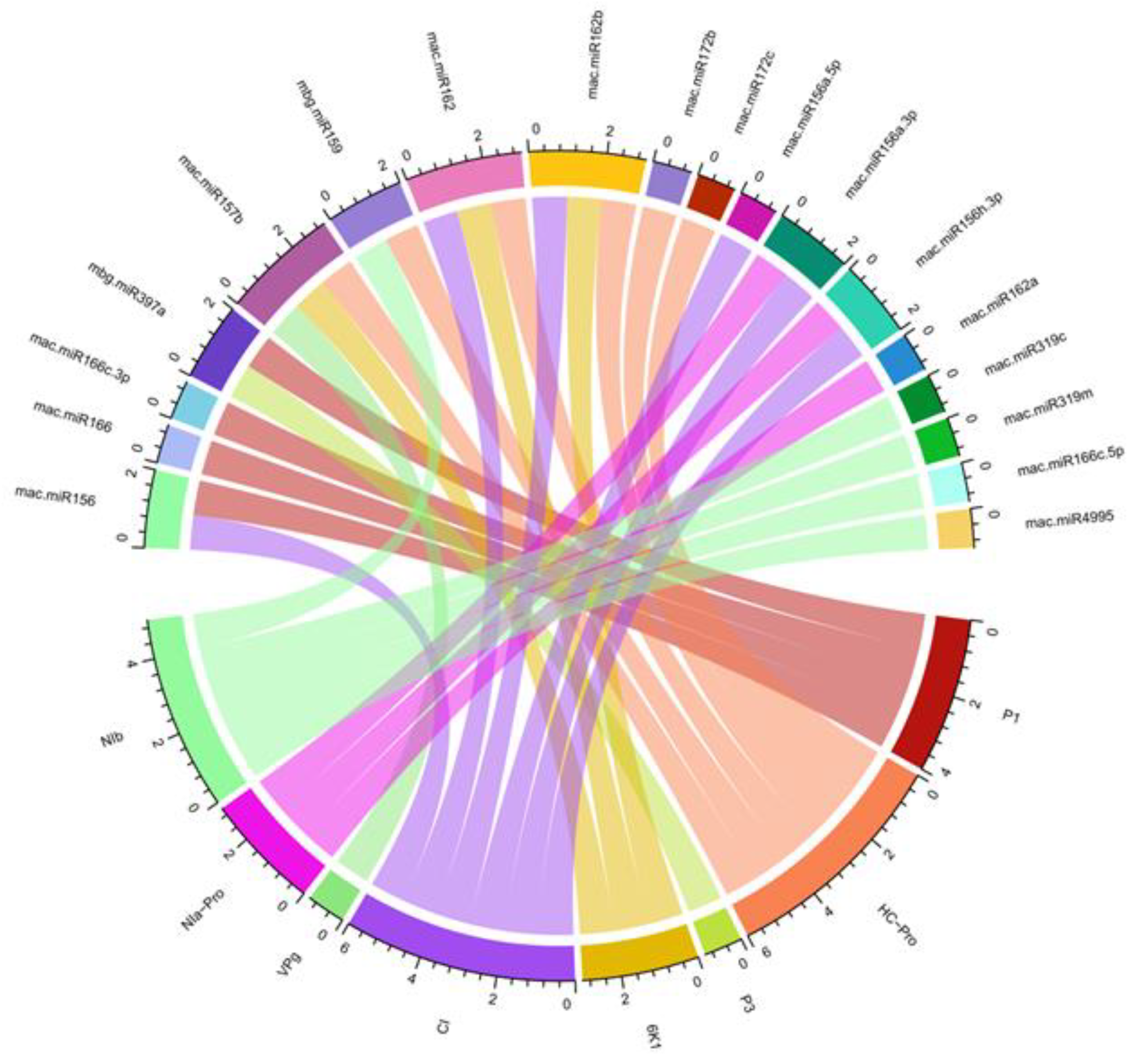

3.10.3. Integrated Analysis of miRNA-Target Network

A Circos map of potentially complex host–virus interaction based on predicted miRNAs. The Circos map clearly illustrated the biological data to visualize a comprehensive mapped banana miRNA regulatory network interacting with the BBrMV genomic target genes (ORFs) to identify novel antiviral targets (

Figure 8).

3.11. Assessment of Free Energy of Interaction (ΔG)

To further validate the predicted miRNAs, free energies (ΔG) of banana RNA-RNA interaction duplexes during hybridization were assessed using the RNAcofold algorithm (

Table 4). The mechanism of interaction between banana consensus miRNAs and BBrMV +ssRNA-encoded mRNAs based on thermodynamics, were also elucidated for the very first time.

4. Discussion

The BBrMV belongs to the genus

Potyvirus, that originated in East Asia and continued to spread in the late 20th century. Recent advancements in miRNA biology have reshaped our understanding of the biological landscape, revealing novel regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Plant host locus-derived miRNAs are key endogenous biomolecules that function as post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression through RNA silencing mechanisms [

7,

39]. Integrative computational approaches have recently been developed to identify potential high-affinity miRNA-target sites, thereby elucidating complex virus-host interactions [

40]. Recently, several studies have reported that mature miRNAs, endogenously encoded and derived from host plant loci, have predicted potential to target RNA or DNA viruses, based on miRNA target prediction tools [

41,

42] . Several studies have investigated the effectiveness and durability of amiRNA expression in transgenic plants to abate viral infection [

8,

9,

10,

43,

44]. Previously experimentally validated banana locus-derived miRNAs (n = 32) were selected and analyzed accordingly to identify all potential binding sites on the BBrMV +ssRNA-encoded mRNAs.

To assess the reliability of target prediction tools, we compared their performance in distinguishing true from false-positive candidates, focusing on novel target discovery. We employed a suite of complementary in silico tools—each with varying levels of robustness and based on distinct criteria—to predict interactions between viral binding sites and plant host miRNAs. We employed four algorithms—RNA22, RNAhybrid, TAPIR, and psRNATarget—to leverage their computational complementarity and minimize false-positive predictions (

Figure 1). We designed an integrative computational pipeline to predict and validate miRNA targets, evaluating results at individual, union, and intersection levels (

Figure 2)[

40,

45].

The banana common mac-miR4995 was the most potent predicted banana mac-miRNA based on the union of all four tools (

Figure 4,

Table 1). The RNA22, RNAhybrid and psRNATarget algorithms predicted hybridization of mac-miR157b at nucleotide position 1537-1559. Together, the three algorithms, the RNAhybrid, TAPIR and psRNATarget were used to detect the consensus high-confidence binding site of mbg-miR397a (start site 2701) that can silence the viral P3 protein. Both algorithmics approaches—individual and consensus—converged on mbg-miR397a, identifying it as a pivotal regulator and a promising molecule of significant therapeutic interest (

Figure 7,

Table 2 and

Table 3).

The effectiveness and durability of RNA-RNA duplex is associated with RNA-binding free energy [

46]. The MFE is extensively utilized as a key parameter in computational methods for predicting miRNAs and making evolutionary inferences [

47]. The accurate prediction of functional miRNA target interaction relies on two key factors: binding site accessibility, and the MFE of the duplex which is crucial for experimental validation [

48]. The miRNA–target interaction with lower MFE values are more stable [

49]. Maximum stability of the miRNA-mRNA duplex is achieved through optimal binding affinity between the miRNA and its target mRNA[

46,

50]. The target site for mbg-miR397a exhibited the strongest MFE value among the predicted banana miRNAs. The MFE of mbg-miR397a was estimated to be −23.00 Kcal/mol (RNAhybrid) (

Table 2), and −19.35 Kcal/mol (RNAcofold) (

Table 4), making the pair potential “true targets”.

No experimental studies have yet identified specifically focusing on banana miRNAs for targeting the BBrMV +ssRNA-encoded mRNAs. In silico analyses demonstrated that the banana consensus mbg-miR397a is expected to target BBrMV P3 coding region. Silencing of the BBrMV P3 gene which is a membrane-associated protein that is required for replication, movement, and pathogenicity [

51,

52]. The banana mbg-miR397a is involved in drought stress responsiveness in Musa spp [

53]. Enhanced biomass production in banana has been achieved through the over-expression of

Musa-miR397, as demonstrated in earlier study [

54]. The MIR397 functions as a regulator of multiple stress responses in rice, including drought, low temperature, and deficiencies in nitrogen and copper (Cu) [

55]. In summary, miR397 acts as a critical post-transcriptional regulator by fine-tuning laccase gene expression. This modulation of lignin biosynthesis serves as a central mechanism through which miR397 governs fundamental aspects of plant growth, development and adaptation, making it a significant target for both basic research and agriculture biotechnology [

56].

The low MFE value observed for the banana-encoded miRNA–BBrMV-mRNA duplex indicates strong binding potential, reducing the likelihood of false positive results. The integration of results from a ‘four algorithms’ approach is designed to create a highly sensitive and specific in silico strategy for identifying authentic miRNA-mRNA interactions.

By rigorously evaluating predictions at the individual, union, and intersection levels, this approach effectively filters false positives (

Figure 4 and

Figure 7).

Exploring the interactions of potyviruses with host miRNA machinery involve complex transcriptional events [

57]. Our data demonstrate a diverse landscape of intermolecular RNA–RNA interactions between banana genome-encoded miRNAs and BBrMV ORFs. The next step is to design optimal multi-amiRNA-based constructs that can be regulated at multiple levels for silencing the BBrMV genome. The amiRNA can trigger gene silencing [

9]. The specificity of amiRNAs is based on sequence-specific base-paring with the target gene to minimize deleterious off-target effects. There are no acceptable commercial BBrMV-resistant banana plants. To develop BBrMV-resistant banana plants, future work will validate the role of these promising short-listed miRNAs in viral replication. The predicted banana miRNAs were further evaluated to understand complex host-virus interaction to localize virus-specific targets of interest.

5. Challenges and Limitations

BBrMV is a deleterious banana pathogen and has been reported as the predominant potyvirus species associated with BBrMD in East Asia. BBrMV severely diminishes banana productivity. In this study, we employed five different tools to identify the most effective banana miRNAs for silencing the BBrMV genome. Among the 32 banana miRNAs interrogated, only one—mbg-miR397a—was predicted by a consensus of algorithms to have the potential to modulate viral infection, making it a compelling candidate for further research on silencing the P3 protein. The P3 is a hybridization site with antiviral potential, capable of binding miRNA and inhibiting virus replication. In addition to mbg-miR397a, the consensus banana miRNA, mac-miR157b was also predicted as the top-ranking effective candidate and was positively validated with a stable MFE. Specific experimental work is needed to evaluate the promiscuity, affinity, and binding landscape of the short-listed banana-encoded miRNAs in transgenic banana plants. Understanding these host-virus interactions enhances our knowledge of BBrMV infections and supports the development of advanced amiRNA-based targeting strategies, including assessing the antiviral potential of transgenic plants and environmental interventions.

6. Conclusion and Future Directions

BBrMV is a deleterious banana pathogen and has been reported as the predominant potyvirus species associated with BBrMD in East Asia. BBrMV severely diminishes banana productivity. In this study, we employed five different tools to identify the most effective banana miRNAs for silencing the BBrMV genome. Among the 32 banana miRNAs interrogated, only one—mbg-miR397a was predicted by a consensus of algorithms to have the potential to modulate viral infection, making it a compelling candidate for further research on silencing the P3 protein. The P3 is a hybridization site with antiviral potential, capable of binding miRNA and inhibiting virus replication. In addition to mbg-miR397a, the consensus banana miRNA, mac-miR157b was also predicted as the top-ranking effective candidate and was positively validated with a stable MFE. Specific experimental work is needed to evaluate the promiscuity, affinity, and binding landscape of the short-listed banana-encoded miRNAs in transgenic banana plants. Understanding these host-virus interactions enhances our knowledge of BBrMV infections and supports the development of advanced amiRNA-based targeting strategies, including assessing the antiviral potential of transgenic plants and environmental interventions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: High-confidence target sites of banana miRNAs in BBrMV genome; Table S2: Gene-wise prediction of banana miRNAs in the BBrMV genome; File S1: A list of high-confidence mature banana microRNAs; File S2: In silico algorithms, RNA22, RNAhybrid, TAPIR and psRNATarget and TAPIR were used to identify binding sites of banana miRNAs.

Author Contributions

M.A.A. and N.Y. conceived of the concept, approaches and data interpretation. M.A.A., S.W., M.K., M.A., E.S. and A.N. carried out the in silico experiments. M.K., M.A., E.S. and A.N. made the graphs. M.A.A. and S.W. made the tables and wrote the manuscript. All the authors participated in the interpretation of the results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by International Science & Technology Cooperation Program of Hainan Province (GHYF2023010), Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (322RC769), Central Public Interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (NO. 1630052023003), Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences, and Emerson University, Multan under a MoU. The APC was funded by N.Y.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the insightful discussions and unwavering from their laboratory colleagues. The co-authors S.W., M.K., N.K., M.A., E.S. and A.N. completed this research as part of their final-year research report. The authors are grateful to the Talented Young Scientist Program (TYSP) of China for supporting M.A.A. The authors acknowledge the invaluable support provided by Emerson University, Multan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maseko, K.H.; Regnier, T.; Meiring, B.; Wokadala, O.C.; Anyasi, T.A. Musa species variation, production, and the application of its processed flour: A review. Scientia Horticulturae 2024, 325, 112688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.; Maraschin, M. Banana (Musa spp) from peel to pulp: ethnopharmacology, source of bioactive compounds and its relevance for human health. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2015, 160, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yu, S.; Cheng, Z.; Chang, X.; Yun, Y.; Jiang, M.; Chen, X.; Wen, X.; Li, H.; Zhu, W. Origin and evolution of the triploid cultivated banana genome. Nature genetics 2024, 56, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.-R.; Liu, X.; Arshad, R.; Wang, X.; Li, W.-M.; Zhou, Y.; Ge, X.-J. Telomere-to-telomere haplotype-resolved reference genome reveals subgenome divergence and disease resistance in triploid Cavendish banana. Horticulture research 2023, 10, uhad153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajan, R.; Balasubramanian, V.; Priyanka, P.; Jebakumar, R.M.; Selvam, K.P.; Uma, S. Evidence of seed transmission of Banana bract mosaic virus in Musa synthetic diploid H-201, a possible threat to banana breeding. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2020, 156, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.; Pamitha, N.; Gopika, A.; Biju, C. Complete genome sequencing of banana bract mosaic virus isolate infecting cardamom revealed its closeness to banana infecting isolate from India. VirusDisease 2018, 29, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajczyk, M.; Jarmolowski, A.; Jozwiak, M.; Pacak, A.; Pietrykowska, H.; Sierocka, I.; Swida-Barteczka, A.; Szewc, L.; Szweykowska-Kulinska, Z. Recent insights into plant miRNA biogenesis: multiple layers of miRNA level regulation. Plants 2023, 12, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Vázquez, L.A.; Castro-Pacheco, A.M.; Pérez-Vargas, R.; Velázquez-Jiménez, J.F.; Paul, S. The Emerging Applications of Artificial MicroRNA-Mediated Gene Silencing in Plant Biotechnology. Non-coding RNA 2025, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Zhang, X.; Ji, H.; Yasir, M.; Farooq, T.; Dai, X.; Li, F. Large artificial microRNA cluster genes confer effective resistance against multiple tomato yellow leaf curl viruses in transgenic tomato. Plants 2023, 12, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yuan, Q.; Ai, X.; Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yan, F. Transgenic rice plants expressing artificial miRNA targeting the rice stripe virus MP gene are highly resistant to the virus. Biology 2022, 11, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakta, S.; Tak, H.; Ganapathi, T.R. Exploring diverse roles of micro RNAs in banana: Current status and future prospective. Physiologia Plantarum 2021, 173, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Feng, R.; Shi, H.; Ren, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Bioinformatic identification and expression analysis of banana microRNAs and their targets. Plos one 2015, 10, e0123083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Kong, X.; Li, Y.; Dalmay, T.; Han, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Qu, H.; Zhu, H. Cu-miRNA-mediated redox homeostasis explains the differences in cold tolerance between AAA and ABB banana varieties. Journal of Advanced Research 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Ali, B.; Fareed, M.; Sardar, A.; Saeed, E.; Islam, S.; Bano, S.; Yu, N. In Silico Identification of Banana High-Confidence MicroRNA Binding Sites Targeting Banana Streak GF Virus. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Peng, K.; Shan, Y.; Yun, Z.; Dalmay, T.; Duan, X.; Jiang, Y.; Qu, H.; Zhu, H. Transcriptional regulation of miR528-PPO module by miR156 targeted SPLs orchestrates chilling response in banana. Molecular Horticulture 2025, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayers, E.W.; Beck, J.; Bolton, E.E.; Brister, J.R.; Chan, J.; Connor, R.; Feldgarden, M.; Fine, A.M.; Funk, K.; Hoffman, J. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information in 2025. Nucleic acids research 2025, 53, D20–D29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, K.C.; Huynh, T.; Tay, Y.; Ang, Y.-S.; Tam, W.-L.; Thomson, A.M.; Lim, B.; Rigoutsos, I. A pattern-based method for the identification of MicroRNA binding sites and their corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell 2006, 126, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loher, P.; Rigoutsos, I. Interactive exploration of RNA22 microRNA target predictions. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 3322–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krüger, J.; Rehmsmeier, M. RNAhybrid: microRNA target prediction easy, fast and flexible. Nucleic acids research 2006, 34, W451–W454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, E.; He, Y.; Billiau, K.; Van de Peer, Y. TAPIR, a web server for the prediction of plant microRNA targets, including target mimics. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1566–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhao, P.X. psRNATarget: a plant small RNA target analysis server (2017 release). Nucleic acids research 2018, 46, W49–W54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Zhao, P.X. psRNATarget: a plant small RNA target analysis server. Nucleic acids research 2011, 39, W155–W159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywinski, M.; Schein, J.; Birol, I.; Connors, J.; Gascoyne, R.; Horsman, D.; Jones, S.J.; Marra, M.A. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome research 2009, 19, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhart, S.H.; Tafer, H.; Mückstein, U.; Flamm, C.; Stadler, P.F.; Hofacker, I.L. Partition function and base pairing probabilities of RNA heterodimers. Algorithms for Molecular Biology 2006, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandrud, C. Reproducible research with R and R studio; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pasin, F.; Simon-Mateo, C.; García, J.A. The hypervariable amino-terminus of P1 protease modulates potyviral replication and host defense responses. PLoS Pathogens 2014, 10, e1003985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.; Lõhmus, A.; Dutta, P.; Pollari, M.; Mäkinen, K. Interplay of HCPro and CP in the regulation of potato virus A RNA expression and encapsidation. Viruses 2022, 14, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunna, H.; Qu, F.; Tatineni, S. P3 and NIa-Pro of turnip mosaic virus are independent elicitors of superinfection exclusion. Viruses 2023, 15, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bera, S.; Arena, G.D.; Ray, S.; Flannigan, S.; Casteel, C.L. The potyviral protein 6K1 reduces plant proteases activity during turnip mosaic virus infection. Viruses 2022, 14, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorel, M.; García, J.A.; German-Retana, S. The Potyviridae cylindrical inclusion helicase: a key multipartner and multifunctional protein. Molecular plant-microbe interactions 2014, 27, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cheng, G.; Yang, Z.; Wang, T.; Xu, J. Identification of sugarcane host factors interacting with the 6K2 protein of the sugarcane mosaic virus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, F.A.d.; Luna-Aragão, M.A.d.; Ferreira, J.D.C.; Souza, F.F.; Rocha Oliveira, A.C.d.; Costa, A.F.d.; Aragão, F.J.L.; Santos-Silva, C.A.d.; Benko-Iseppon, A.M.; Pandolfi, V. Deciphering Cowpea Resistance to Potyvirus: Assessment of eIF4E Gene Mutations and Their Impact on the eIF4E-VPg Protein Interaction. Viruses 2025, 17, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Zhang, W.; Xu, S.; Yang, W.; Yin, J.; Zhou, T.; Kundu, J.K.; Xu, K. Protease activity of NIa-Pro determines systemic pathogenicity of clover yellow vein virus. Virology 2025, 604, 110417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamaki, M.-L.; Valkonen, J.P. Control of nuclear and nucleolar localization of nuclear inclusion protein a of picorna-like Potato virus A in Nicotiana species. The Plant Cell 2009, 21, 2485–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Jia, M.; Shan, H.; Gao, W.; Jiang, L.; Cui, H.; Cheng, X.; Uzest, M.; Zhou, X.; Wang, A. Viral RNA polymerase as a SUMOylation decoy inhibits RNA quality control to promote potyvirus infection. Nature Communications 2025, 16, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Shi, Y.; Dai, Z.; Wang, A. The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase NIb of potyviruses plays multifunctional, contrasting roles during viral infection. Viruses 2020, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hervás, M.; Ciordia, S.; Navajas, R.; García, J.A.; Martínez-Turiño, S. Common and strain-specific post-translational modifications of the potyvirus Plum pox virus coat protein in different hosts. Viruses 2020, 12, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodersen, P.; Sakvarelidze-Achard, L.; Bruun-Rasmussen, M.; Dunoyer, P.; Yamamoto, Y.Y.; Sieburth, L.; Voinnet, O. Widespread translational inhibition by plant miRNAs and siRNAs. Science 2008, 320, 1185–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y.; Schmid, M.; Wang, Y. miRNA mediated regulation and interaction between plants and pathogens. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffo-Campos, Á.L.; Riquelme, I.; Brebi-Mieville, P. Tools for sequence-based miRNA target prediction: what to choose? International journal of molecular sciences 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Ali, B.; Brown, J.K.; Shahid, I.; Yu, N. In silico identification of cassava genome-encoded MicroRNAs with predicted potential for targeting the ICMV-Kerala begomoviral pathogen of cassava. Viruses 2023, 15, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Shahid, I.; Brown, J.K.; Yu, N. An Integrative Computational Approach for Identifying Cotton Host Plant MicroRNAs with Potential to Abate CLCuKoV-Bur Infection. Viruses 2025, 17, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, M.F.; Tan, J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, W.; Zhuang, T.; Lu, W.; Qiu, Y.; Du, X.; Zhuang, X.; Zhou, T. Transgenic expression of artificial microRNA targeting soybean mosaic virus P1 gene confers virus resistance in plant. Transgenic Research 2024, 33, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Roshdi, M.R.; Ammara, U.; Khan, J.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Shahid, M.S. Artificial microRNA-mediated resistance against Oman strain of tomato yellow leaf curl virus. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1164921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.C.; Bovolenta, L.A.; Nachtigall, P.G.; Herkenhoff, M.E.; Lemke, N.; Pinhal, D. Combining results from distinct microRNA target prediction tools enhances the performance of analyses. Frontiers in genetics 2017, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, A.; Shankar, R.; Bagchi, S.; Grama, A.; Chaterji, S. MicroRNA target prediction using thermodynamic and sequence curves. BMC genomics 2015, 16, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thody, J.; Moulton, V.; Mohorianu, I. PAREameters: a tool for computational inference of plant miRNA–mRNA targeting rules using small RNA and degradome sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Research 2020, 48, 2258–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinzón, N.; Li, B.; Martinez, L.; Sergeeva, A.; Presumey, J.; Apparailly, F.; Seitz, H. microRNA target prediction programs predict many false positives. Genome research 2017, 27, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kertesz, M.; Iovino, N.; Unnerstall, U.; Gaul, U.; Segal, E. The role of site accessibility in microRNA target recognition. Nature genetics 2007, 39, 1278–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golyshev, V.; Pyshnyi, D.; Lomzov, A. Calculation of energy for RNA/RNA and DNA/RNA duplex formation by molecular dynamics simulation. Molecular Biology 2021, 55, 927–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Fang, Y.; Luan, Y.; Cui, X.; Zhou, X.; Wang, A.; Cheng, X. P3N-PIPO interacts with P3 via the shared N-terminal domain to recruit viral replication vesicles for cell-to-cell movement. Journal of Virology 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, H.; Shine, M.; Cui, X.; Chen, X.; Ma, N.; Kachroo, P.; Zhi, H.; Kachroo, A. The potyviral P3 protein targets eukaryotic elongation factor 1A to promote the unfolded protein response and viral pathogenesis. Plant Physiology 2016, 172, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, K.; Ihearahu, O.C.; Agbor, V.E.; Evans, T.; Naitchede, L.H.S.; Ray, S.; Ude, G. In Silico Genome-Wide Profiling of Conserved miRNAs in AAA, AAB, and ABB Groups of Musa spp.: Unveiling MicroRNA-Mediated Drought Response. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.; Yadav, K.; Srivastava, A.K.; Suprasanna, P.; Ganapathi, T.R. Overexpression of native Musa-miR397 enhances plant biomass without compromising abiotic stress tolerance in banana. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 16434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, P.K.; Gupta, P.; Pradhan, S.K.; Shasany, A.K.; Rai, R. Analysis of homologous regions of small RNAs MIR397 and MIR408 reveals the conservation of microsynteny among rice crop-wild relatives. Cells 2022, 11, 3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhou, J.; Gao, L.; Tang, Y. Plant miR397 and its functions. Functional Plant Biology 2020, 48, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Arvy, N.; German-Retana, S. The mystery remains: How do potyviruses move within and between cells? Molecular Plant Pathology 2023, 24, 1560–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Commonly used features of computational algorithms for miRNA target prediction.

Figure 1.

Commonly used features of computational algorithms for miRNA target prediction.

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram showing biological data and computational tools that enable the integration of miRNA prediction in the BBrMV genome. The biological data integration framework represents banana locus-derived miRNAs and BBrMV genome. Four suites of target prediction tools, RNA22, RNAhybrid, TAPIR and psRNATarget were employed to identify miRNA-binding sites. The R language is programming language used for creating plots. .

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram showing biological data and computational tools that enable the integration of miRNA prediction in the BBrMV genome. The biological data integration framework represents banana locus-derived miRNAs and BBrMV genome. Four suites of target prediction tools, RNA22, RNAhybrid, TAPIR and psRNATarget were employed to identify miRNA-binding sites. The R language is programming language used for creating plots. .

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of banana bract mosaic virus genome organization. The genomic coordinates are based on BBrMV ORFs (NCBI accession no. MG758140). The 10 kb RNA genome of BBrMV presented and each predicted coding region and UTR are marked by the colored boxes.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of banana bract mosaic virus genome organization. The genomic coordinates are based on BBrMV ORFs (NCBI accession no. MG758140). The 10 kb RNA genome of BBrMV presented and each predicted coding region and UTR are marked by the colored boxes.

Figure 4.

Venn diagram showing of banana miRNA prediction overlap. The diagram depicts the number of banana miRNAs predicted to target BBrMV +ssRNA-encoded mRNAs by four algorithms (RNA22, RNAhybrid, TAPIR, and psRNATarget), analyzed at the target binding site level. The intersection of all four prediction sets identified a single unique miRNA: mac-miR miR4995. .

Figure 4.

Venn diagram showing of banana miRNA prediction overlap. The diagram depicts the number of banana miRNAs predicted to target BBrMV +ssRNA-encoded mRNAs by four algorithms (RNA22, RNAhybrid, TAPIR, and psRNATarget), analyzed at the target binding site level. The intersection of all four prediction sets identified a single unique miRNA: mac-miR miR4995. .

Figure 5.

Predicted target sites of banana miRNAs along the BBrMV +ssRNA genome. (A) Target sites identified by RNA22. (B) The miRNA targets obtained by RNAhybrid. (C) TAPIR identified binding sites. (D) Target sites were identified by psRNATarget tool. Each dot represents a single binding site. The ORFs encoded on the BBrMV genome are indicated by a different color. .

Figure 5.

Predicted target sites of banana miRNAs along the BBrMV +ssRNA genome. (A) Target sites identified by RNA22. (B) The miRNA targets obtained by RNAhybrid. (C) TAPIR identified binding sites. (D) Target sites were identified by psRNATarget tool. Each dot represents a single binding site. The ORFs encoded on the BBrMV genome are indicated by a different color. .

Figure 6.

Union plot representing banana miRNA-mRNA target pairs in the BBrMV genome, predicted by all tools.

Figure 6.

Union plot representing banana miRNA-mRNA target pairs in the BBrMV genome, predicted by all tools.

Figure 7.

The intersection plot shows the consensus binding sites of banana miRNAs. Analysis detected three high-affinity potential consensus miRNA-binding sites that target distinct coding regions— namely, CI, HC-Pro and P3 of the BBrMV genome.

Figure 7.

The intersection plot shows the consensus binding sites of banana miRNAs. Analysis detected three high-affinity potential consensus miRNA-binding sites that target distinct coding regions— namely, CI, HC-Pro and P3 of the BBrMV genome.

Figure 8.

An integrated Circos plot shows all predicted interaction between banana miRNAs and BBrMV genomic sequences. The colored lines connection represents coding sequences of BBrMV genome.

Figure 8.

An integrated Circos plot shows all predicted interaction between banana miRNAs and BBrMV genomic sequences. The colored lines connection represents coding sequences of BBrMV genome.

Table 1.

The number of banana miRNA-target sites predicted to interact with the BBrMV coding region.

Table 1.

The number of banana miRNA-target sites predicted to interact with the BBrMV coding region.

| BBrMV Gene |

RNA22 |

RNAhybrid |

TAPIR |

psRNATarget |

| P1 |

mbg-miR399a1 |

|

mac-miR4995 |

mac-miR156, mac-miR166, mac-miR166c-3p and mbg-miR397a |

| HC-Pro |

mac-miR157b and mac-miR160 (a, g-5p) |

mac-miR157b, mac-miR160g, mac-miR166 (b, c-5p), mac-miR172 (b, c) and mac-miR4995 |

|

mbg-miR157b, mbg-miR159, mac-miR162, mac-miR162b and mac-miR172 (b, c) |

| P3 |

mac-miR166 (b, c-5p) and mac-miR4995 |

mac-miR156a-5p, mac-miR159, mac-miR319 (c, m) and mac-miR397a |

mac-miR172 (b, c) and mbg-miR397a |

mbg-miR397a |

| 6K1 |

|

|

|

mac-miR157b, mac-miR162 mac-miR162b |

| CI |

mac-miR166, mac-miR166 (b, c-5p) and mac-miR166c-3p |

mac-miR156 (a-3p, h-3p), mac-miR156 (d, g), mac-miR157 (b-5p), mac-miR160 (a, g-5p), mac-miR162, mac-miR162a, mac-miR162b and mbg-miR399a1 |

mac-miR162 and mac-miR162b |

mac-miR156, mac-miR156a-5p, mac-miR156 (a-3p, h-3p), mac-miR162 and mac-miR162b |

| 6K2 |

|

mac-miR164e |

|

|

| VPg |

|

|

|

mac-miR157b |

| NIa-Pro |

|

mac-miR169h, mac-miR166 and mac-miR166c-3p |

|

mac-miR156 (a-3p, h-3p) and mac-miR162a |

| NIb-Pro |

|

mac-miR169h, mac-miR166 and mac-miR166c-3p |

|

mbg-miR159, mac-miR319c, mac-miR319m, mac-miR166c-5p and mac-miR4995 |

| CP |

mbg-miR399a |

mac-miR167 (c, d) |

|

|

| 5’UTR |

|

mac-miR156 |

|

|

Table 2.

Target sites of predicted consensus banana miRNAs identified in the BBrMV genome.

Table 2.

Target sites of predicted consensus banana miRNAs identified in the BBrMV genome.

Banana

miRNAs ID |

Site/Gene

RNA22 |

Site/Gene

RNAhybrid |

Site/Gene

TAPIR |

Site/Gene

psRNATarget |

MFE *

RNA22 |

MFE**

RNAhybrid |

MFE** Ratio

TAPIR |

Expectation psRNATarget |

| mac-miR157b |

1537 (HC-Pro) |

1544(HC-Pro) |

|

1537(HC-Pro) |

−19.90 |

−26.90 |

|

7.00 |

| mac-miR162 |

|

4725(CI) |

3820(CI) |

3820(CI) |

−15.30 |

−25.50 |

0.49 |

6.00 |

| mac-miR162b |

|

4725(CI) |

3820(CI) |

3820(CI) |

−15.30 |

−25.50 |

0.49 |

6.00 |

| mbg-miR397a |

|

2703(P3) |

2703(P3) |

2701(P3) |

|

−23.00 |

0.50 |

5.00 |

Table 3.

The consensus banana-miRNAs were predicted for targeting (HC-Pro, C1 and P3) genes..

Table 3.

The consensus banana-miRNAs were predicted for targeting (HC-Pro, C1 and P3) genes..

Banana

miRNAs ID |

Mature Sequence

(5′–3′) |

Predicted Targets

ORF(s) |

Binding Sites

(nt) |

Mode of

Inhibition |

| mac-miR157b |

GCUCUCUAUGCUUCUGUCAUCA |

HC-Pro |

1537-1559 |

Cleavage |

| mac-miR162 |

UCGAUAAACCGCUGCGUCCA |

CI |

3820-3839 |

Cleavage |

| mac-miR162b |

UCGAUAAACCGCUGCGUCCAG |

CI |

3820-3839 |

Cleavage |

| mbg-miR397a |

UCAUUGAGUGCAGCGUUGAUG |

P3 |

2701-2721 |

Cleavage |

Table 4.

The binding free energy (ΔG) of miRNA-mRNA duplexes was computed.

Table 4.

The binding free energy (ΔG) of miRNA-mRNA duplexes was computed.

| miRNA ID |

miRNA–mRNA Sequence

(5′–3′) |

ΔG Duplex

(Kcal/mol) |

ΔG Binding

(Kcal/mol) |

Genomic

Coordinates |

| mac-miR157b |

5′ GCUCUCUAUGCUUCUGUCAUCA 3′

5′ AATTTTCTGAAGCATCAGAGAGC 3′ |

−21.18 |

−13.39 |

1537-1559 |

| mac-miR162 |

5′ UCGAUAAACCGCUGCGUCCA 3′

5′ CGTGTTGTAGCGCATTATCGA 3′ |

−17.84 |

−14.86 |

3820-3839 |

| mac-miR162b |

5′ UCGAUAAACCGCUGCGUCCAG 3′

5′ CGTGTTGTAGCGCATTATCGA3′ |

−17.99 |

−14.82 |

3820-3839 |

| mbg-miR397a |

5′ UCAUUGAGUGCAGCGUUGAUG 3′

5′ TCACAACATTGCATTCATTGG 3′ |

−19.35 |

−17.25 |

2701-2721 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |