1. Introduction

Existing European district heating systems are undergoing a profound transformation to meet the EU’s 2050 decarbonisation goals. The revised Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) [

1] establishes that by 2028, DH systems must source at least 5% of heat from renewable sources (RES), and by 2035, 35% must be from either renewable or waste heat sources (WHS) and 80% in total renewable, waste, or high-efficiency cogeneration (CHP). By 2050, an efficient DH system must use only renewable energy, only waste heat, or only a combination of renewable energy and waste heat.

The focal point of this study is the strategic planning of the energy transition and decarbonization process for large DH systems. A growing body of literature nowadays investigates technological and strategic solutions for such systems. Lund et al. [

2,

3] introduced the fourth-generation district heating (4GDH) concept, promoting lower temperature operation and integration with renewable electricity. Volkova et al. [

4] and Sihvonen et al. [

5] highlighted large-scale heat pumps and sector coupling as key enablers of future heating systems. Pakere et al. [

6] demonstrated that multi-source DH systems can achieve full decarbonisation by combining solar, biomass, and waste heat supported by seasonal storage. Pettersson et al. [

7] and Pursiheimo et al. [

8] emphasised the importance of integrated planning and compared heat pump and nuclear options for Nordic cities. Kubin et al. [

9] presented DH transformation planning results, which confirmed that flexible sector coupling technologies form the backbone of the most economically efficient transition pathway. They highlighted the risks of rapid scale-up, especially regarding permitting, investment, and supply chain conditions.

Dzierzgowski and Cenian [

10] proposed a decarbonisation methodology which focuses on substation modernisation and regulation, followed by the implementation of low-carbon heat sources (including waste heat) and the implementation of digital measures (monitoring and modelling). A large scale experiment performed in the DH system in Łomża, Poland, confirmed that the implemented methodology allowed a decrease in network supply temperature (from 121 to 96

oC) in the whole system, leading to lower heat losses, in turn reducing coal demand and CO

2 emissions (up to 30%), and increase of heat transfer efficiency in buildings, grid hydraulic stability and improvement in working condition of mixing systems in the CHP and heating Plant.

Kalina et al. [

11] reveal that in such systems, decarbonisation is technically attainable, yet far more complex than often assumed. The transformation faces substantial technical barriers. The high operating temperatures of existing networks limit the performance of heat pumps during the heating season, and the large-scale seasonal storage required to balance intermittent sources exceeds what is realistically possible. Even when technically feasible, the transition introduces significant economic burdens. Under the study’s financial modelling, the overall investment package leads to a negative net present value unless supported by substantial external funding. The study concludes that decarbonisation cannot be treated as a narrow technological upgrade. Instead, success depends on broader structural changes, including lowering network temperatures, improving building efficiency, enabling sector coupling, adjusting legal frameworks, and establishing new business models for cooperation with waste heat suppliers.

The announced strategies of such cities as Berlin, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, and Vienna revealed that, depending on local conditions, the future primary energy mix may be highly diversified and DH systems become very complex structures. Although these strategies differ in pace, resource availability and governance, a clear pattern emerges. Each of the considered cities envisions a future district heating system built on low-temperature networks, large-scale heat pumps, extensive waste-heat recovery and the systematic integration of renewable electricity.

Berlin’s strategy reflects both the legacy of a large, historically fossil-fuelled heat system and growing political ambition [

12]. Coal has already been phased out, and future supply is expected to rely heavily on industrial and data-centre waste heat, combined with large heat pumps powered by renewable electricity. Detailed Berlin’s heat planning process is based on heat maps and zoning tools, which determine where district heating will expand, where buildings will shift to individual heat pumps and how existing networks will gradually be transformed. Lowering supply temperatures is essential to integrate low-temperature resources, while bans on new fossil installations and updated efficiency standards reinforce the shift at the regulatory level.

Amsterdam approaches decarbonisation from a different angle, which is a binding political decision to eliminate natural-gas use in buildings by 2040 [

13]. Publicly released heat transition visions outline which districts will move to DH, all-electric solutions or hybrid systems. Amsterdam’s plans emphasise rapid expansion of both high- and low-temperature networks and make unusually strong use of aquathermal energy (i.e., heat extracted from canals, rivers and wastewater) as well as large heat pumps and substantial geothermal potential where geological conditions allow. Waste heat from waste-to-energy plants and data centres serves as a further backbone of the system. The city pairs this technical rollout with a socially oriented governance framework that ensures affordability and transparency as gas networks are dismantled neighbourhood by neighbourhood.

Copenhagen, long considered a frontrunner in district heating, has articulated some of Europe’s most detailed long-term strategies. The city’s carbon-neutrality goal and the broader metropolitan “Heat Plan Copenhagen” [

14] provide a system-wide blueprint that extends to mid-century. The plan foresees a marked reduction in network temperatures, enabling large heat pumps, geothermal installations and significant amounts of industrial and municipal waste heat to feed into the system. Copenhagen emphasises system optimisation through sector coupling, where district heating is positioned as a flexible component in a wider energy system dominated by wind and solar power. Large-scale thermal storage, including pit thermal energy storage, ensures that excess renewable electricity can be converted into heat and stored for later use. Remaining fossil or biomass-based CHP plants are expected to be gradually replaced or supplemented by carbon-neutral fuels and carbon-capture technologies. Power-to-X technologies and CO

2 capture installations are also taken into consideration.

Vienna’s trajectory is influenced by its 2040 fossil-free heating target, one of the earliest and most ambitious in Europe. The city has developed a heat-planning approach that distinguishes areas best served by district heating from those suited to individual heat pumps [

15,

16]. As part of this strategy, district heating is expected to supply more than half of the city’s heat demand by 2040, and the DH system itself must reach full climate neutrality by the same year. Large heat pumps powered by wastewater, river water and industrial waste heat form a central pillar. Deep geothermal energy, combined with heat pumps, is projected to deliver a substantial share of Vienna’s future district heating production, around 4 TWh annually, allowing the gradual retirement of fossil-fuelled CHP plants. At the same time, existing waste-to-energy facilities are to be progressively decarbonised through more efficient operation and potentially carbon-capture technologies. Vienna complements these technological measures with broad renovation programmes and a citywide initiative “Raus aus Gas”, which pilots alternatives to gas in municipal and social housing, ensuring that building-level interventions align with the transformation of the heat networks.

Malcher et al. [

17] evaluated how different decarbonization strategies reduce emissions in national district heating systems by applying an integrated energy-and-emissions model combined with a derivative-based sensitivity analysis. Focusing on Sweden, France, Germany and Poland, they examined widely discussed measures such as increasing low-carbon heat sources, lowering supply temperatures, improving efficiency, deploying power-to-heat technologies, and modifying the role of CHP. Results show that the effectiveness of these strategies varies strongly by each country’s energy mix and the extent to which CHP plants rely on fossil fuels. Expanding low-carbon heat sources is consistently the most impactful option. A 1% increase in their share can reduce emissions by 0.8–1.3 kg CO

2e/GJ of heat. In Sweden and France, where electricity is already largely low-carbon, heat pumps and electric boilers emerge as the next most effective measures. Conversely, in Germany and Poland, characterised by higher-carbon power, reducing heat demand and distribution losses delivers comparable emission cuts (0.7–1.3 kg CO

2e/GJ). Substantially lowering fossil-fuel-based CHP generation also achieves significant reductions, challenging policies that incentivise gas-fired CHP. Other options, including green hydrogen and CCS, offer noticeably smaller benefits.

This paper focuses on Bucharest, Romania, where the DH system is the largest in the European Union. According to the IEA DHC definition [

18], this is a second-generation system with a water network operating forward temperature ranging from 80 to 110 ℃. The district heating network (DHN) has a total length of 3847 km and delivers heat to more than 500,000 individual households, 3611 industrial and 1122 other consumers. The current peak demand for heat approaches 2.0 GW, and the annual amount of heat delivered to the network is around 4500 GWh/year. The heating network covers around 72 % of the heating demand of the Municipality of Bucharest. The remaining 28 % is heat produced in various individual heating units.

The input energy mix is not diversified, and the system is almost entirely based on the combustion of natural gas. As for 2024, it experiences severe losses and frequent breakdowns. The key system components, i.e. production plants and networks, are worn out and in bad technical condition. Since the system has been underinvested for many years, the scale of the required renovation is enormous. A potential action plan is presented in this study, which examines possibilities to integrate different technological solutions.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was performed under the Life Programme co-founded LIFE22-CET-SET_HEAT project framework. It builds on analyses conducted within joint development and design activities from October 1

st 2023, to March 14

th 2025, of the project, including a series of the project’s co-creation workshops in Croatia, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania, which took place in 2024 and 2025. During the workshops, the Project Partners and invited guests worked together to identify potential technology solutions and other measures, which would help targeted DH systems meet the status of efficient ones as defined in the revised Energy Efficiency Directive [

1].

The main problem in this study is to assess the technically feasible scenarios for the decarbonisation of the large fossil-fuel-fired DH system in Bucharest in a way that would meet the criteria of an efficient district heating system (EDHS) given in the EED [

1]. The objective is to meet the criteria of an efficient DH system from 1 January 2028, by ensuring that the share of heat from RES in the total amount of heat fed into the DHN is at least 5% and the total share of RES, WHS or CHP is at least 50%. From 1 January 2035, the target is to ensure a minimum of 35% RES and WHS, and a minimum of 80% total share of these sources and CHP. This constitutes the following constraints for the strategic planning:

where

u is the share of heat from particular types of heat sources in the total heat delivered to DHN,

Qi is the heat delivered from specific source

i at hour

t.

The research and planning methodology integrated making inventories of existing infrastructure, system diagnostics, system and energy mapping, scenario development, investment modelling and assessment, and hourly system simulations based on actual weather, load and market data. The adopted methodological approach was broadly discussed in [

11]. In the case of Bucharest, however, greater attention was paid to spatial planning and the location of individual heat sources in the dense urban area. Several web tools and public data sources [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23] were used for data collection, and the energyPRO

TM software [

24] was used for system simulations. The operation of particular production units was optimised using Mixed Integer Linear Programming Technique (MILP) and the open source HiGHS solver integrated in the software tool. Costing and financial calculations were made using the MS Excel spreadsheet software.

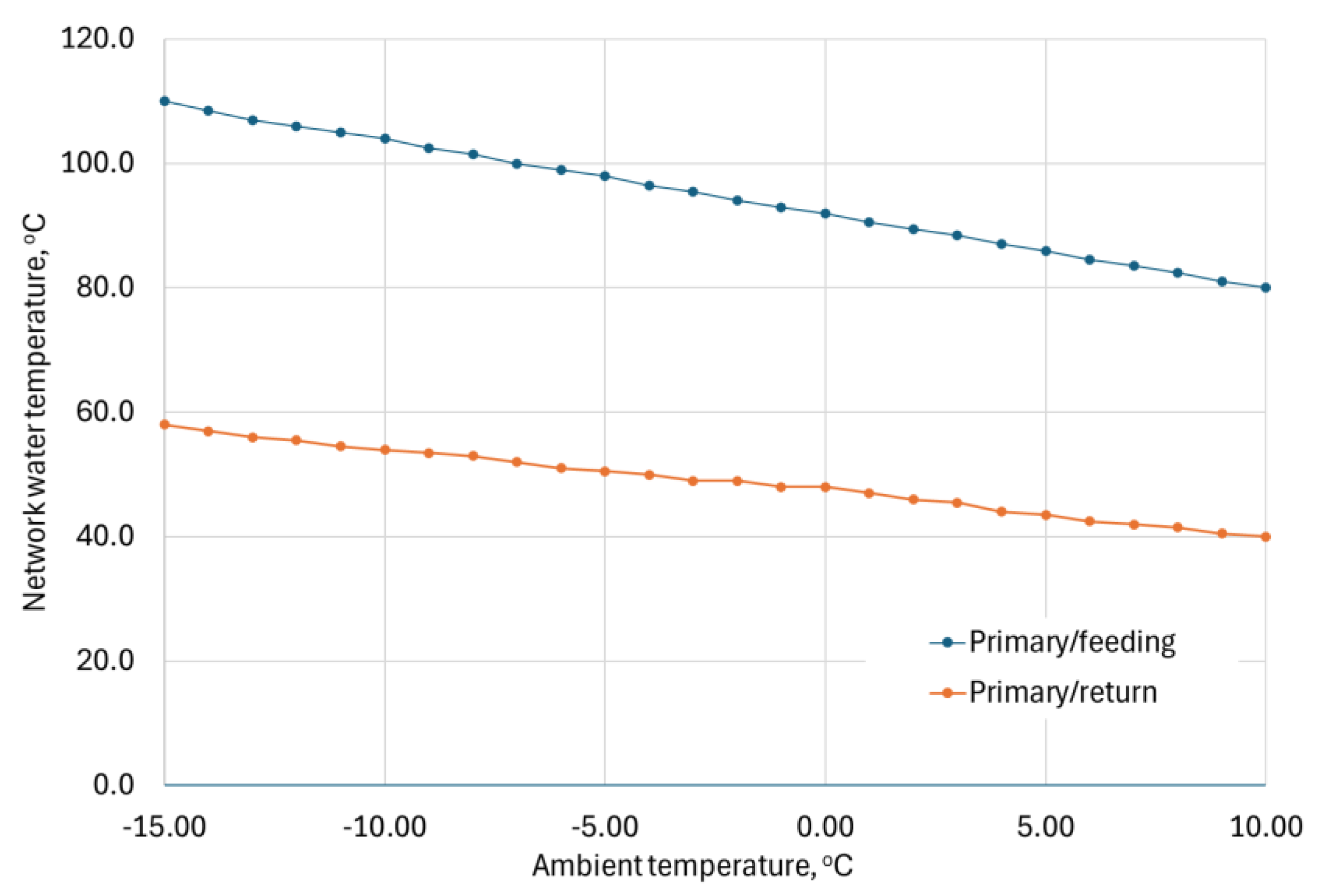

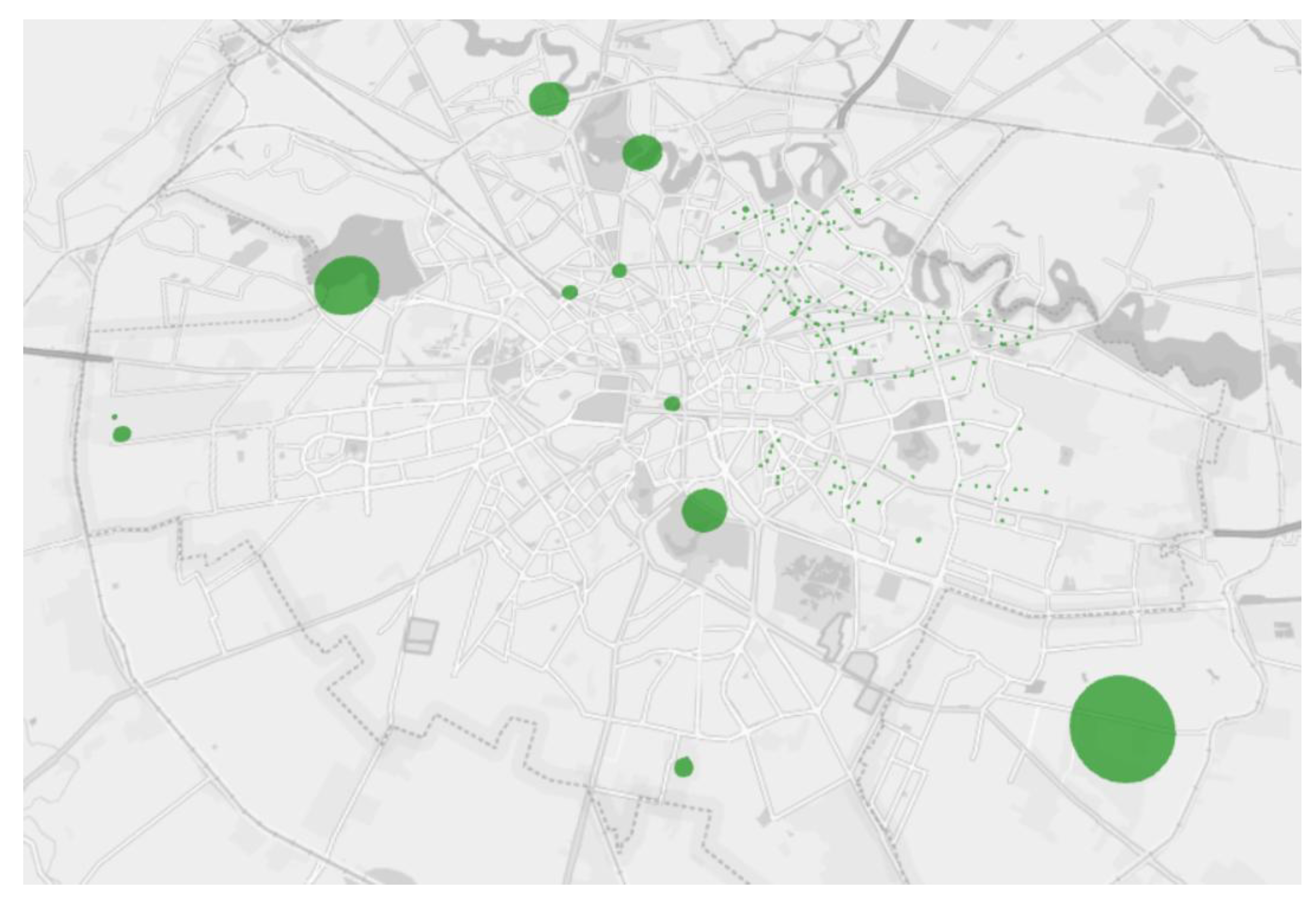

The Bucharest DH network comprises 6 heating areas, so-called sectors, and 8 main production plants, namely Sud, Progresul, Grozăvești, Vest, Vest Energo, and Grivița, Titan and Casa Presei, with a combined installed heating capacity exceeding 1.73 GW

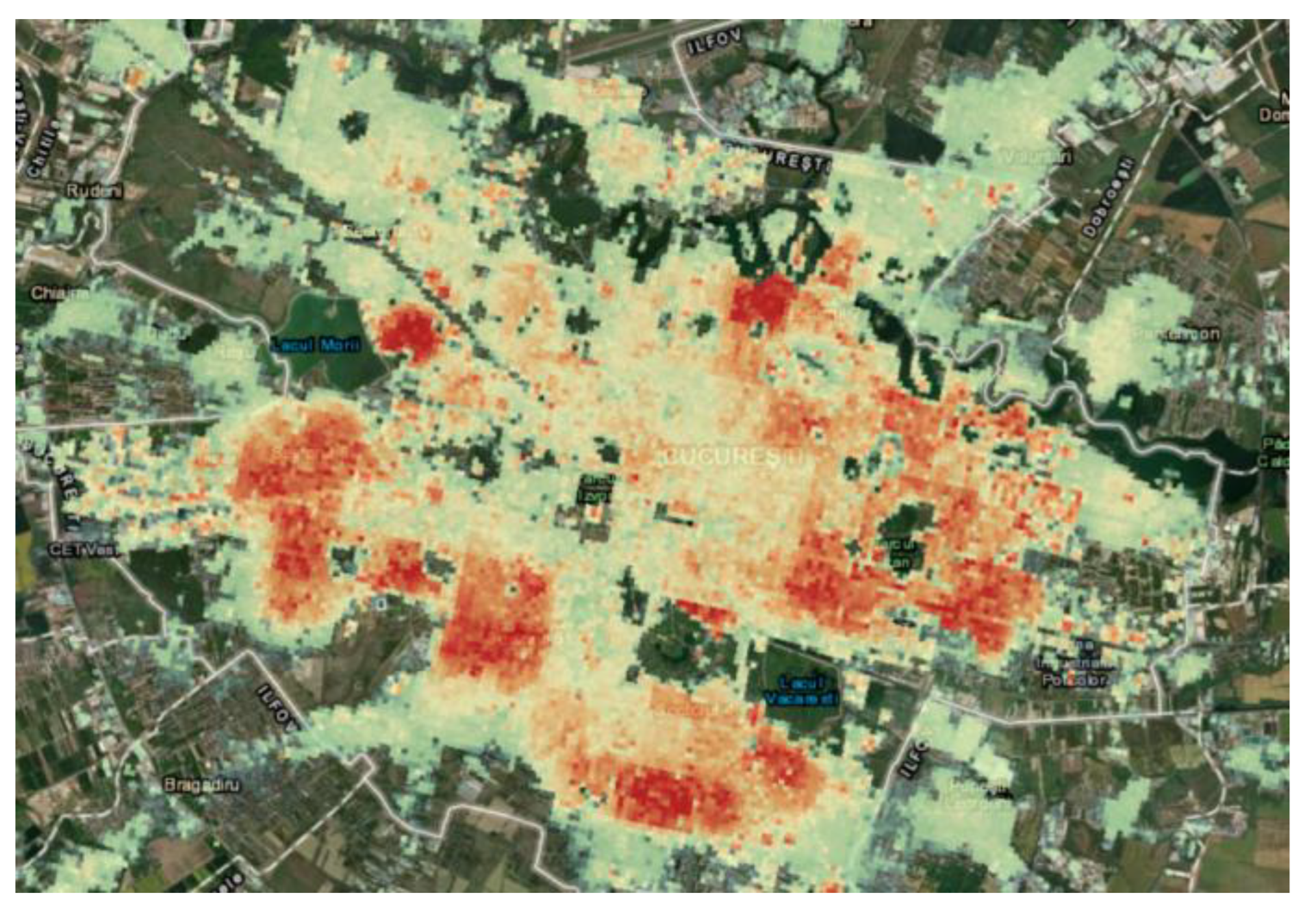

th. Forward temperatures range from 80 to 110 °C, with returns of 40–55 °C, characteristic of second-generation DH systems. The system boundary and location of heating plants are depicted in

Figure 1. In addition, there are more than 46 local gas boiler plants of the total installed capacity of 257 MW, which are not delivering heat to the DH network but directly to buildings. The total heat demand density is depicted in

Figure 2.

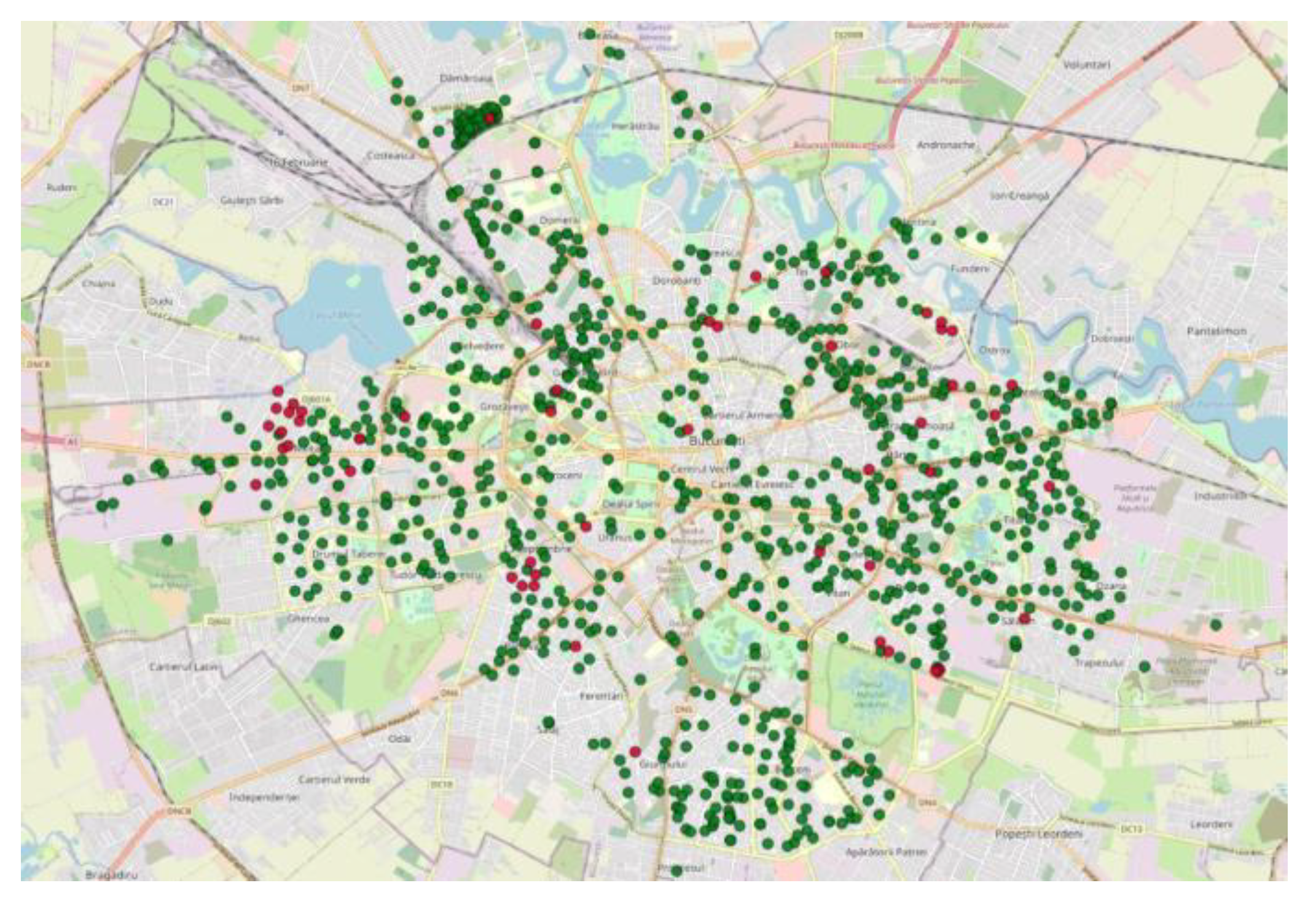

The DHN, which supplies heat to approximately 8,200 apartment blocks, 320 buildings, and around 4,900 institutions, is operated by Compania Municipală Termoenergetica București S.A. (CMTEB). It has a total length of 3847 km, of which 884 km form the so-called primary transmission network, and the remaining 2963 km form the secondary distribution network, to which buildings are connected. An important components of the network infrastructure are around 1027 so-called Thermal Points, which are heat exchanger stations between primary and secondary networks. The location of these stations around the city is depicted in

Figure 3.

Nowadays, around 92% of DHN input heat is purchased from external suppliers. In total, approximately 74% of purchased heat is produced in old-fashioned steam cycle cogeneration units, and the remaining 26% is produced in boilers. All in-house production of CMTEB is done in boilers.

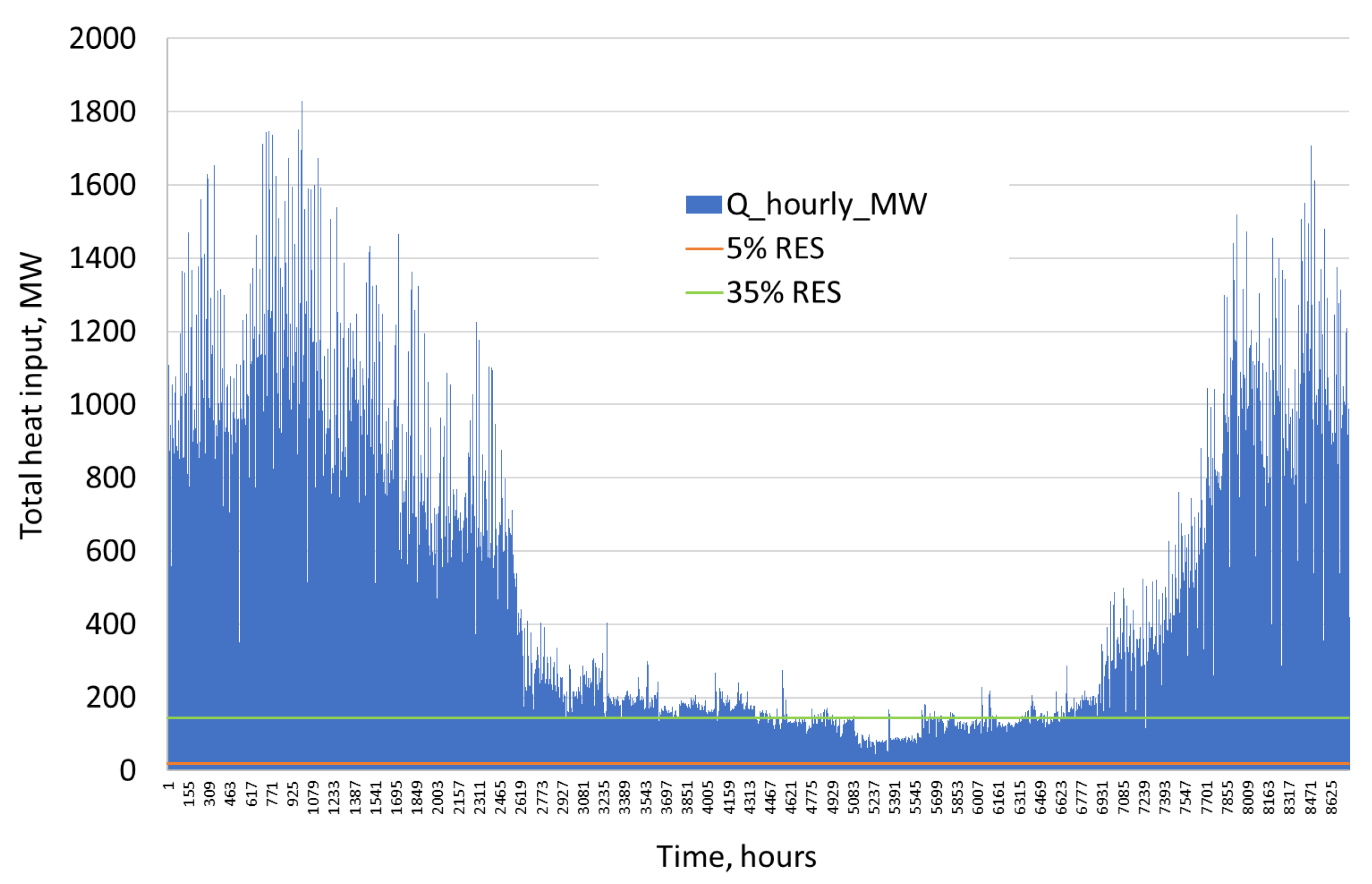

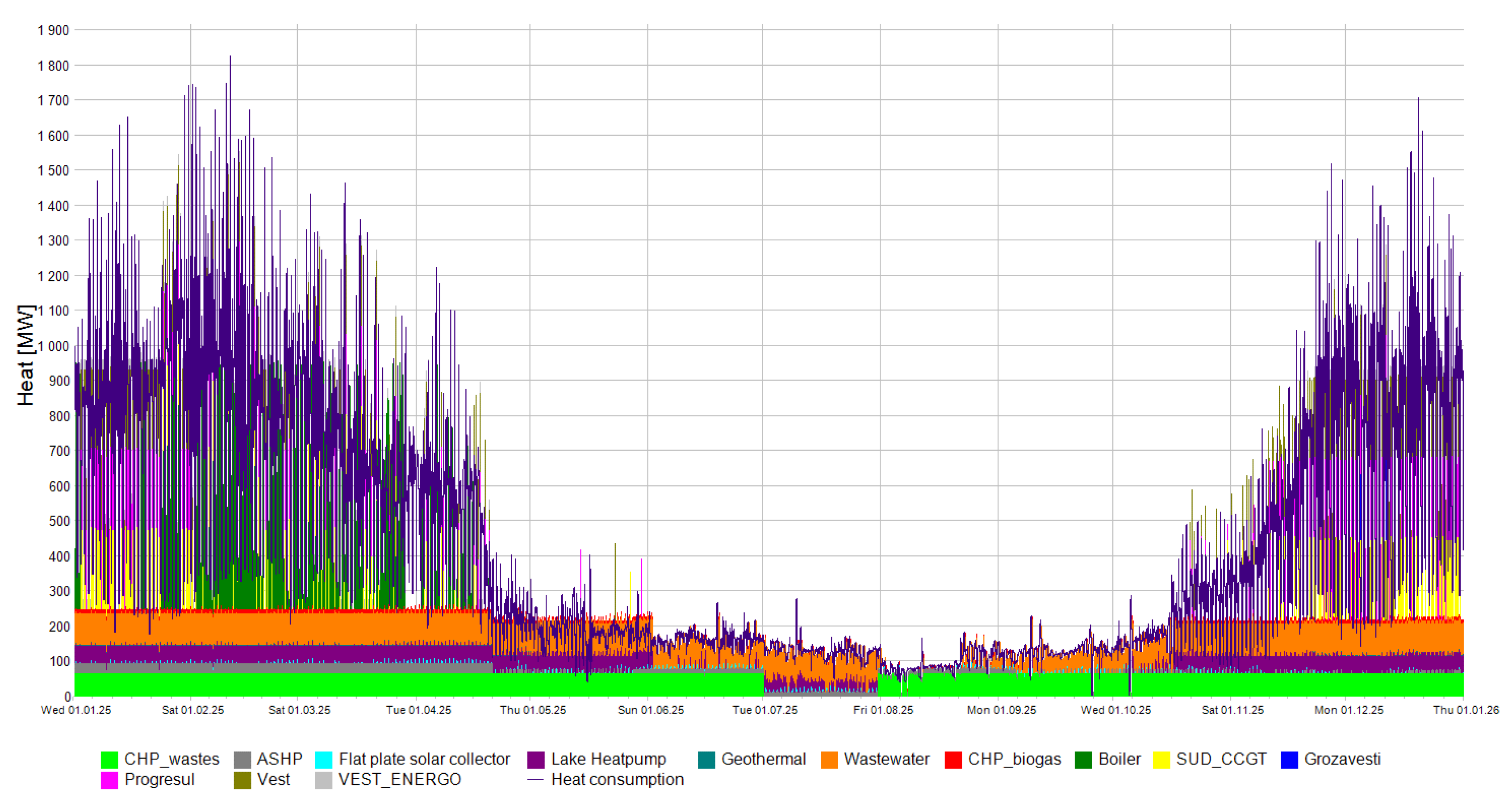

Figure 4 depicts an annual DHN heat supply profile, and

Figure 5 shows the primary network regulation curves.

Figure 4 also shows an indicative level of newly installed (continuous) heating capacity to satisfy the requirements of EED for an efficient DH system.

Although the system currently meets the criteria of an efficient district heating system set in EED, its current technical condition is not satisfactory regarding the heat sources, networks and installations in buildings. The thermal plants were put into operation between 1955 and 1982. Around 65% of the primary network and 46% of the secondary network are pipelines older than 25 years. The biggest problem with the network is the high corrosion of the pipes. Many parts of the network are damaged, causing major operational problems and low availability of the system, which currently ranges from 75 to 85% due to numerous failures. The annual number of emergency interventions exceeds 1250. The risk of system collapse is high. Annual heat losses from the DHN amount to 30 – 40%. With the priorities: 1) reliability and security of heat supply, 2) heat affordability, 3) heat greening, significant local resources must be engaged and large investments secured to carry out the system retrofitting and transition simultaneously.

The LIFE22-CET-SET_HEAT project activities focused on heat mapping revealed almost no waste heat, and limited resources to harness renewable energy. The main identified waste heat sources are a potential municipal waste incineration plant, a wastewater treatment plant in Glina, warm ventilation air from metro tunnels, data centres, and shopping malls. The identified renewable energy sources include solar rooftop plants (total potential depicted in

Figure 6), air source heat pumps, lake water heat pumps, geothermal heating plants, and biogas CHP plants using agricultural biomass and separated organic fraction of municipal solid wastes. A waste-to-energy plant incinerating what remains from waste sorting is also a strong option. In total, the newly installed heating capacity potential was estimated at around 367 MW

th, which only allows for meeting the EED’s criteria of an effective DH system until 2039. The results of heat mapping are depicted in

Figure 7. The total number of identified new renewable and waste heat sources is 223, out of which 200 are the rooftops of thermal points. Further decarbonisation of the system requires effective engagement with external stakeholders and appropriate coordination of the planning activities between national and municipal authorities, utility companies, residents, and the private sector. To effectively address the DH decarbonisation challenge, local actors should consider the MultiD approach, which simultaneously takes into consideration such aspects as DH system territorial expansion, decomposition, reconfiguration, multiple distributed and intermittent heat sources, alternative decarbonised fuel-fired cogeneration, heat storage, digitisation, low-temperature heating networks, electrification and sector integration, adjustments of heat sink installations, improved energy efficiency in buildings, large-scale investments in municipal energy infrastructure, active consumers, optimisation, flexibility, resilience, integrated businesses and value stacking, democratisation, and disruption as a usual factor.

The EU Life Programme co-founded the LIFE22-CET-SET_HEAT project aims to accelerate the energy transition and decarbonization of district heating in four targeted Eastern European countries, through triggering strategic investment programmes and a significant number of tangible projects in the field of integration of low-grade renewable energy and waste heat into 2nd generation DHNs. The tactics to achieve a real change on a large scale are based on a coordinated approach to the transition planning that prioritises collaboration, knowledge exchange, and implementation of replicable technical and non-technical solutions. Replication and standardisation are pivotal to the process; they can streamline planning, reduce costs, improve quality, facilitate communication, and ultimately accelerate investment decisions and projects’ implementation.

The central concept of the project was to develop a set of replicable model investment projects that could be adapted and implemented in various locations with minimal modifications. Based on a multi-criteria parametric assessment, 8 so-called model investment projects were defined, namely:

SET_HEAT_SEWAGE, which focuses on heat recovery from treated sewage;

SET_HEAT_RETAIL, which focuses on heat recovery from supermarkets;

SET_HEAT_RIVER, which focuses on a river water industrial heat pump;

SET_HEAT_LAKE, which focuses on a lake water industrial heat pump;

SET_HEAT_AIR, which focuses on an air source industrial heat pump;

SET_HEAT_SOLAR, which focuses on a solar plant as a distributed heat source;

SET_HEAT_PTES, which focuses on a remote seasonal PTES facility;

SET_HEAT_CHP, which focuses on waste heat recovery from low-temperature cooling circuits of existing gas engine cogeneration units.

The identified types of projects were addressed with extensive pre-feasibility studies and other ready-made documentation that aimed to facilitate the development process, implementation and replication. Public versions of the prefeasibility studies are available at the LIFE-CET-SET_HEAT project’s website [

25].

The choice of investment strategy for Bucharest depends on the availability of primary energy sources, the physical feasibility of locating new technologies and integrating them into the network, and the investment and operating costs. It should also be borne in mind that, in accordance with EED requirements [

1], by 2028, the share of renewable energy in total heat going into the network is at least 5 % and the total share of renewable energy, waste heat or high-efficiency cogenerated heat is at least 50 %. By 2035, an efficient district heating system should be using 50 % renewable energy and waste heat, or 35 % of either renewable energy or waste heat, assuming that at least 55% of heat will be from high-efficiency cogeneration units. These thresholds are critical for selecting investment projects. Therefore, assuming that after DHN health restoration, the annual heat consumption will be approximately 3,576,594 MWh, 5% RES share requires at least 178830 MWh of heat from such sources. In 2035, at least 1,251,808 MWh will be required to satisfy a 35% RES share in the system.

After many discussions, it was found that technically it is possible to meet the criteria of the efficient system in 2028 and 2035. Two alternative scenarios were defined based on different energy inputs. However, taking into account the typical duration of project development, permitting implementation and procurement procedures is, in most cases, assessed at 4 to 7 years, it was concluded that regarding the starting point and the investment objectives in Bucharest, it may be difficult to meet the targets on time. Nevertheless, the pathway toward the thresholds for the efficient system set for 2035 is realistic.

Scenario 1 assumes that the key element of the transition will be a waste-to-energy project based on a waste incineration technology. The plant will be using a Refuse-Derived Fuel (RDF), which is a processed fuel made from municipal solid waste (MSW) after removing recyclables and inert materials. According to measurements the typical calorific value of RDF is 15–22 MJ/kg and 40–65% by weight are biogenic contents [

26]. By defining as biomass also waste and residues of biological origin, RED/RED III [

27] permits energy (heat, electricity) produced by burning the biodegradable (biogenic) fraction of waste to count as “renewable energy”, provided that the waste/fuel meets the directive’s sustainability and emissions criteria. It must be noted that since the heat from waste-to-energy plants does not meet the criterion of a by-product, in this work, according to [

28], it is not counted as a waste heat.

In 2019 the General Council of Bucharest Municipality adopted the city’s “Master Plan for Waste Management,” which included a provision to build a large municipal waste-to-energy incinerator. As of 2025, the authorities are still in planning/preparation mode and there is no operational decision or go-ahead for construction. Therefore, realistically, it should be assumed that the waste-to-energy plant will not be commissioned before 2030. Similarly, projects assuming lake water and treated wastewater require long planning and implementation process. Therefore, the share of 5% RES in 2028 can be achieved by implementing solar thermal projects and air-source heat pumps (ASHPs). Eventually, the assumptions for Scenario 1 are:

Phase I:

Firstly, 200 selected thermal points will be equipped with rooftop solar thermal plants. Each system will consist of 80 m2 of collector aperture area which gives around 14.1 MW of peak installed heating capacity and approximately 19,240 MWh of heat annually (It must be noted that first 2 rooftop solar thermal plants are being implemented and further will be deployed after confirming positive operational results);

Secondly, Industrial ASHPs of the total installed capacity of 29 MW will be implemented. Assuming that the ASHPs will be run for 5500 hours a year, the annual heat production will be approximately 159,500 MWh.

Phase II:

- 3.

Waste-to-energy plant of 235,000 tonnes/year RDF processing capacity will be deployed before 2035. Assuming 8000 h of the annual operation time, the RDF chemical energy input will be approximately 135 MW. Taking into account benchmark figures, the expected electric output will be 47.1 MW and heating output will be 67.3 MW. The annual heat generation will be approximately 538,542 MWh. Assuming (with safety margin) that 30% of RDF mass input will the biomass fraction, approximately 161,563 MWh of hear should be regarded as renewable. In addition, it was assumed that RDF price is negative (EUR -0.13/kg), which represents the cost of wastes utilisation.

- 4.

Lake water-source industrial heat pump of 50 MW heating capacity will be installed to harvest heat from Lake Morii.

- 5.

Geothermal heating plants of the total heating capacity of 2 MW will be installed.

- 6.

90 MWth wastewater-source heat pump will be integrated with Glina sewage treatment plant (3 x 30 MWth modular design). It is assumed that a heat pump’s output is can treated as renewable if its seasonal performance factor (SPF) will meets a required minimum threshold.

- 7.

Municipal biogas cogeneration plant will be built of 10 MWth heating output.

- 8.

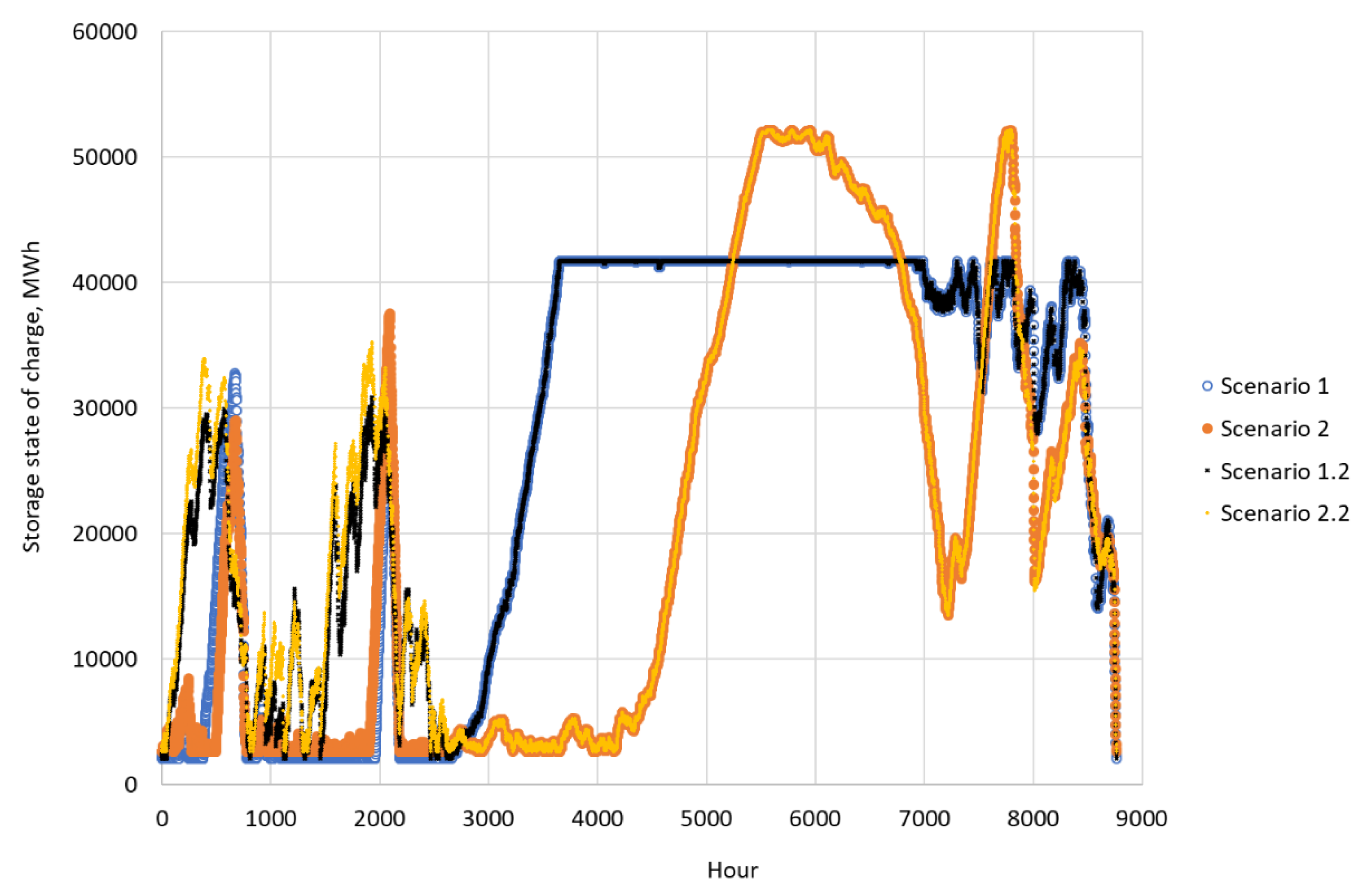

Seasonal Pit Thermal Energy Storage (PTES) will be implemented. The total storage volume will be 1.2 million m3 (6 facilities of 200,000 m3). The storage will be integrated with the DHN without additional heat pumps, and operating temperatures of hot and cold water will be 90 °C and 60 °CC.

Initially assessed contribution to DHN heat input from renewable energy sources is presented in

Table 1. These assumptions are used for building system model in energyPRO software. As a result of simulations the demand for heat storage capacity will be additionally determined.

Scenario 2 is solely based on solar thermal plants (distributed on rooftops and free parcels), water and air source heat pumps. Phase I of this scenario is the same as in the previous case. In Phase II, however, the waste-to-energy plant is replaced by additional 14.1 MW

peak distributed solar thermal plants, and ASHPs of the total installed heating output of 14 MW

th. Providing that heat generated by a heat pump should be counted under [

1] as renewable energy provided that the heat pump meets the minimum efficiency criteria [

29], there will be also installed three ASHPs of total capacity of 7.2 MW to recover heat from Bucharest metro (at Unirii Station, Victoriei Station and Gara de Nord). Furthermore, two water-source heat pumps (WSHPs) of the total heating output of 1.2 MW

th will be installed to recover heat from data centres. Additionally, the total PTES storage volume was enlarged to 1.5 million m

3. Initially assessed contribution to DHN heat input from renewable energy sources in Scenario 2 is presented in

Table 2. Actual contribution of heat sources to the total production was identified after system simulations.

In both scenarios, it was also assumed that 3 existing gas-fired cogeneration plants will be modernised by 2035. Since, within the framework of the LIFE22-CET-SET_HEAT project significant exchange of knowledge and expertise has taken place, including study visits, it was decided that new combined-cycle gas and steam turbine plants (CCGT), as recently built in Zagreb, Croatia [

30], can be replicated in Bucharest. Therefore, EL-TO Zagreb CCGT plant data were used for system modelling. Furthermore, it was assumed that by 2035, the DHN in Bucharest will be revitalised and its health restored.

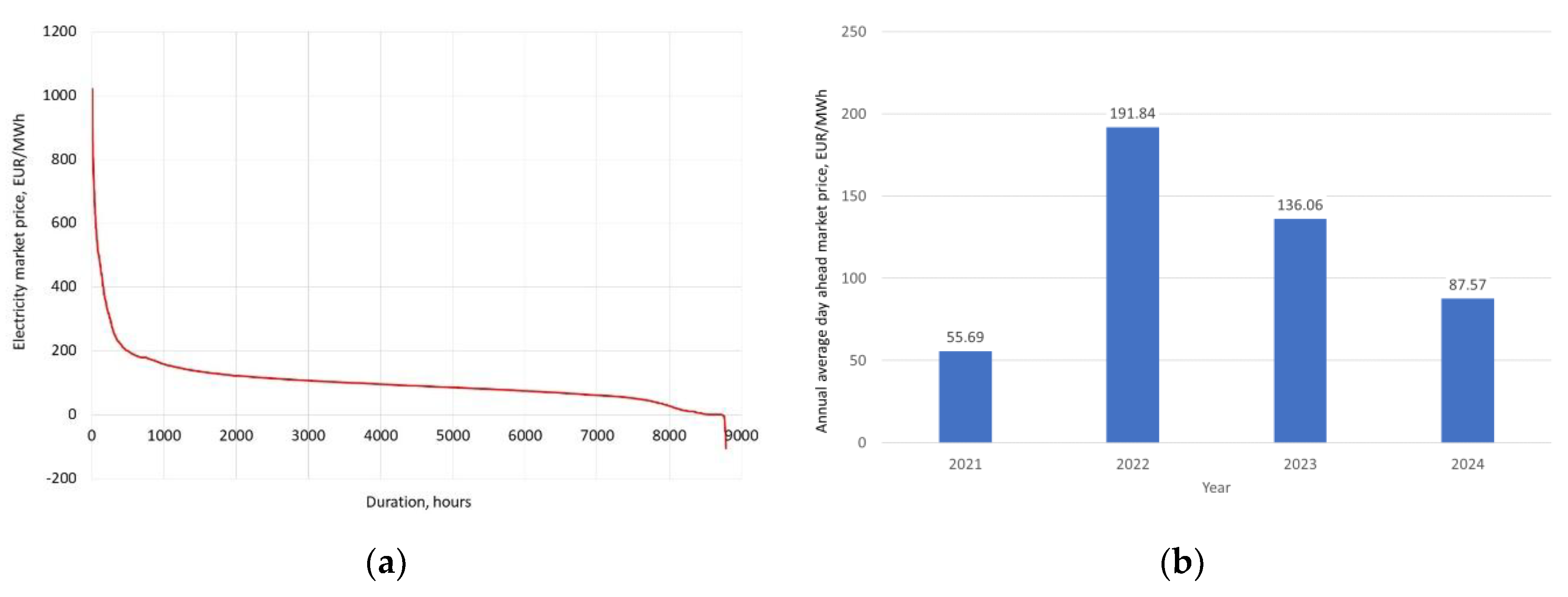

Investment and operational simulations were performed for two milestone years, 2028 and 2035, corresponding to EED compliance thresholds. Each scenario was assessed under technical feasibility, financial sustainability, and environmental performance criteria. Hourly load data for 2024 were analysed alongside weather data and Romania’s day-ahead electricity market prices to evaluate the operational feasibility of industrial heat pumps. The baseline scenario is the current state of the system regarding the production assets and an assumed healthy DHN. In the cases of assumed reduced heat losses, the load duration curve analysis confirmed a peak load of 1,829 MW and an average of 480 MW, corresponding to a load factor of 0.22.

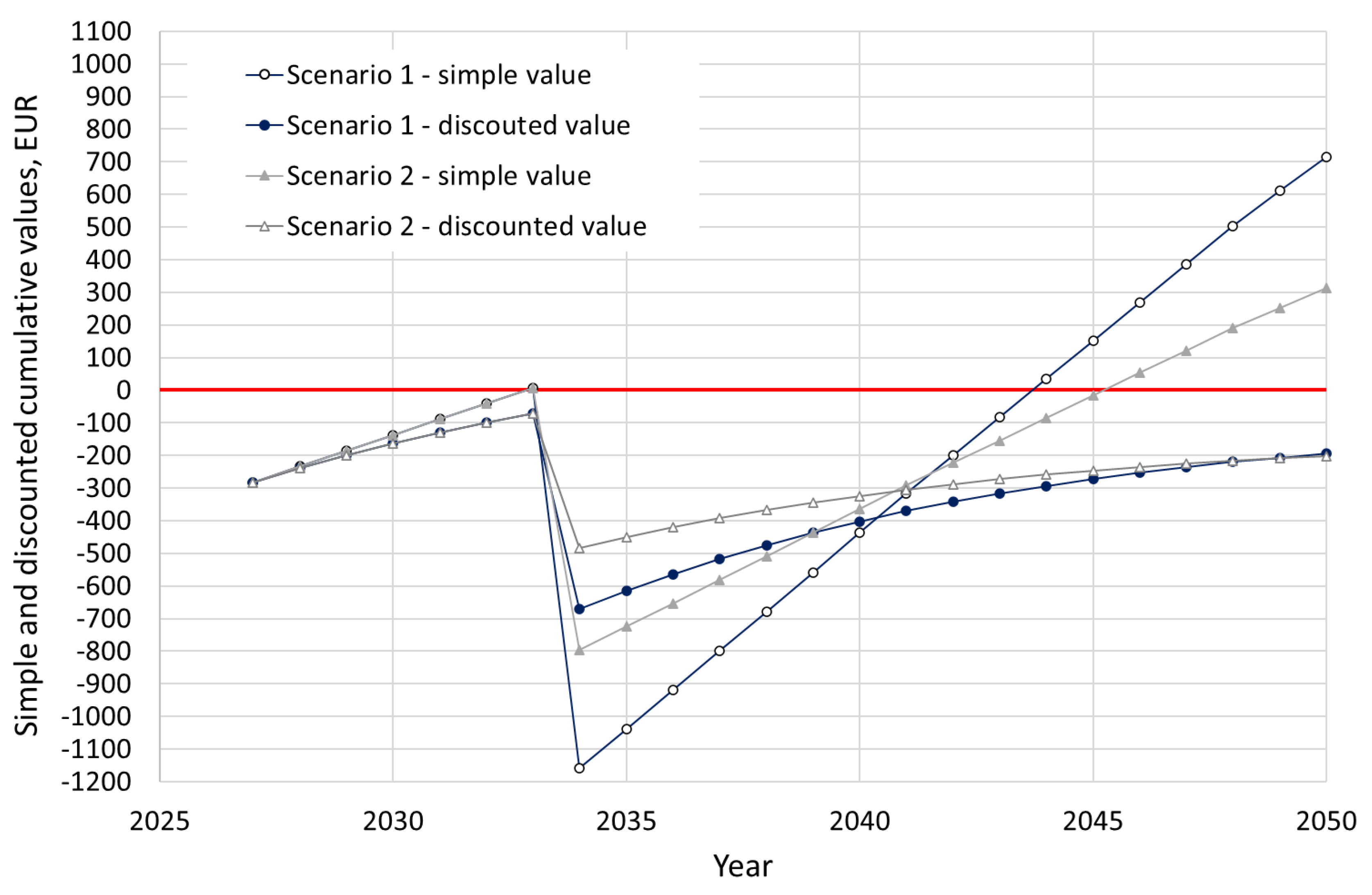

As presented in [

11], the transition of existing DH systems depends on the required capital expenditures (CAPEX) as well as on the market prices of fuels, electricity, and European CO

2 emission allowances (EUA). To reach acceptance, the transition plans must be financially feasible. In [

11], the future market prices were anticipated until 2050. However, actual market data from subsequent years indicates that this approach may be overly optimistic. For example, EUA prices have fallen rather than risen as expected. Therefore, in this study, a simplified approach is adopted that considers constant prices as recorded in 2024. For example,

Figure 8 depicts day-ahead electricity market prices in Romania in 2024 and their annual average value changes from 2021 to 2024.

The initial profitability assessment of the proposed scenarios was performed in terms of net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR), and simple and discounted payback. The profitability in terms of the net present value of the project is:

In terms of IRR, it is:

where

CAPEX stands for the total capital expenditures,

ΔCFy is the differential cash flow in the year

y relative to the reference scenario,

r is the discounted cash flow rate, and

N is the calculation horizon (economic lifetime).

The financial analysis of the project will be presented in a differential approach in relation to the current situation. Under the assumption that no additional incomes are generated from selling heat to final users, achieving cost-effectiveness in the decarbonisation programme hinges on a reduction in the variable cost of heat production compared to a scenario where no action is taken. Generating operating cost savings will then enable the capital expenditure (CAPEX) to be recouped.

The key component of the objective function is the differential annual cash flow

ΔCFy resulting from cash flows after and before the project:

where

CF’y is the cash flow in the year

y after the implementation of a given scenario and

CFy is the cash flow in the year

y in the refence scanario, Δ

Cq,var,t is the variable heat production cost reduction,

ΔTxy is the annual change in tax paid in the year

y, and

ΔLy is the change of residual value of production assets in the year

y.

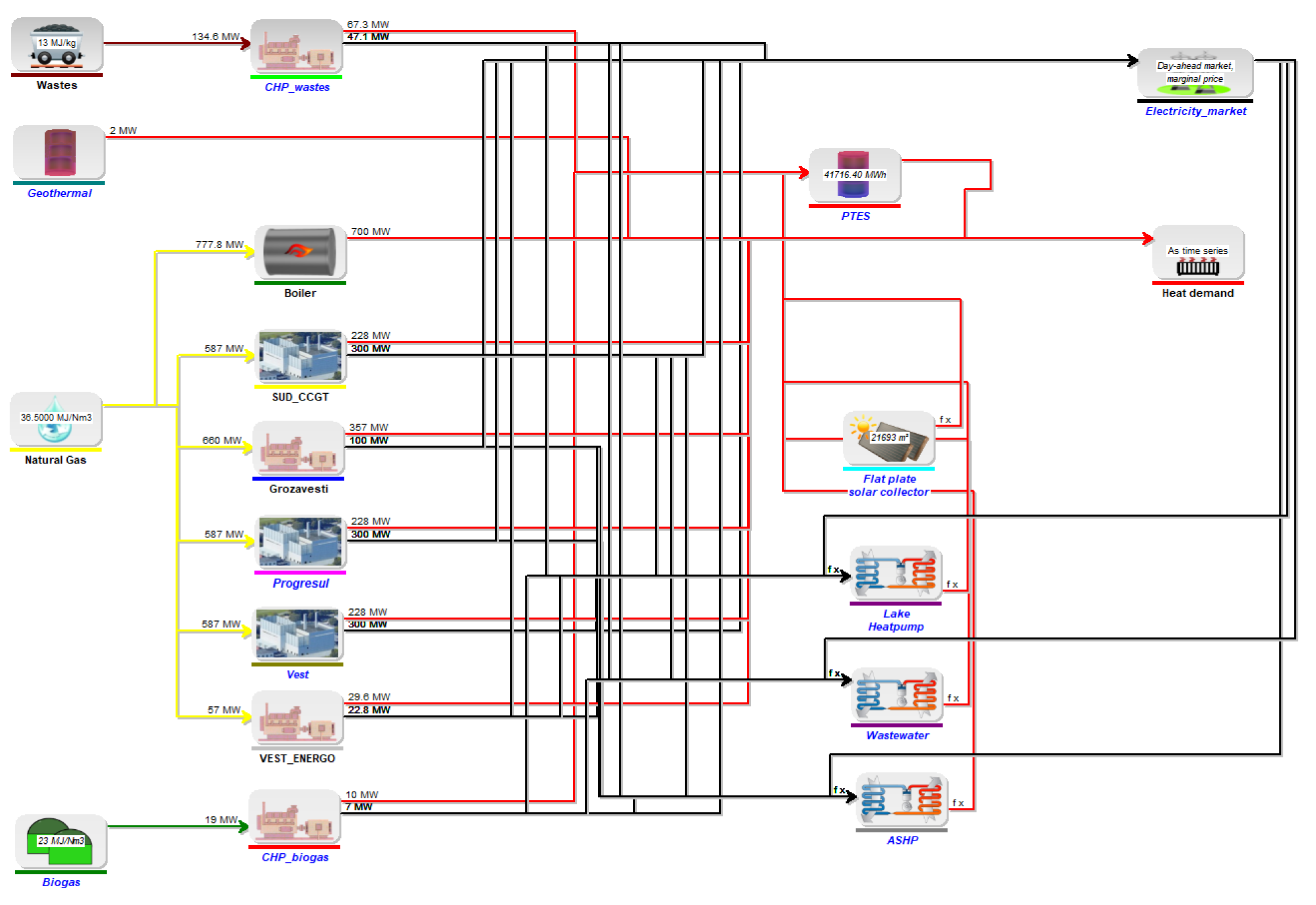

The differential cash flow is calculated against the reference “no action” scenario, which assumes no changes in heat sources but only the revitalisation of the network. The analysis was performed for the integrated system encompassing DHN and heat sources. Since this approach combines together production and network assets, which are in practice owned by different companies, the analysis does not take into consideration the cash flows between the heat producers and the network operator. An example of the Bucharest DH system modelled using the energyPRO v. 4.9 software is depicted in

Figure 9.

In each hour

t, the heat balance of the system must be satisfied:

where

QPTES is the amount of heat charged to or discharged from storage,

Qloss is the heat lost from storage, and

QDHN is the heat fed into DHN.

Operating windows of heat production devices are taken into consideration:

where

min and

max stand for

the minimum and maximum allowable heat output of the device

i.

The variable part of the heat production cost takes into account changes in costs of electricity, fuel costs, and maintenance and environmental costs related to particular heat sources. In the energyPRO, the variable cost of heat is calculated based on the user-specified cost and price vectors for each hour t of a given year using the formula:

where

Cf is the cost of fuel,

Cel is the cost of electricity,

Com is the cost of operation and maintenance,

Cenv is the cost of using the environment,

CETS is the cost of EU EUA and

Sel,chp is the revenue from selling cogenerated electricity.

In each scenario, costs

Cq,var,t is calculated for the given set of production units. The cost of fuel for boilers and CHPs results from heating output, energy efficiency and fuel price:

where

η is the energy efficiency (in the case of CHP related to heat production),

pf is the fuel price per energy unit.

Electricity costs

Cel are calculated assuming the purchase at variable electricity market price and transmission and distribution costs of 50 EUR/MWh paid to the local distribution system operator (DSO). In case of heat pumps, the cost of electricity imports results from the heating output, heat pump coefficient of performance (COP), electricity market price and electricity distribution costs:

where

pel is the electricity market price, and

dcel is the electricity distribution cost.

Equipment operation and maintenance cost for each production unit

Com is calculated using cost data from [

31]. The cost of CO

2 emissions allowances C

ETS is calculated for natural gas and RDF using the heating values

LHVRDF = 21.33 MJ/kg,

LHVgas = 36.54 MJ/Nm

3, and emission indices:

CO2,ETS,RDF = 91.7 kg/GJ,

CO2,ETS,gas = 55.42 kg/GJ given in the legal regulations related to carbon balancing in the EU ETS system.

In the case of cogeneration units, the income from sales of exported electricity is assessed using the formula:

where

σ is the power to heat ratio of the CHP unit, and

α is the auxiliary electricity consumption of the unit.

In case CHP units and heat pumps work together, the electric energy is balanced within the system and costs and revenues are determined only for net imported and exported amounts.

Key assumptions made for the study were as follows:

The amount of heat is constant in the following years (this assumption in practice means that all heat consumption reductions will be compensated by new connections; this trend is currently observed in other LIFE22-CET-SET_HEAT project countries);

Capital expenditures for DHN revitalisation and thermal insulation of building stock are not taken into consideration since these costs must be incurred in all scenarios.

All financial calculations in this study were performed in constant value of money (the base year is 2024);

Time horizon for NPV calculations is 23 years (until 2027 - 2050), and the constant nominal cash flow is used based on the 2024 data;

VAT is not included;

During the investment project, operation of the DH network continues uninterrupted;

No any form of financial support for investments is taken into account in the base financing scenario;

As the basic financing option, the investment is financed 25% from equity and 75% from a bank loan;

The interest rate on the bank loan was assumed to be 9.0% per annum (for corporate investments in Romania);

The repayment period for the bank loan was set to 10 years;

Company income tax rate (CIT) for Romania is 16% of the tax base;

The average annual inflation rate is projected to be 8.6% (as of October 2025 EU harmonised value);

The financial discount rate for the basic analysis was set at 10.0%, which accounts for a higher risk premium;

The investment will not result in an increase in personnel and general administrative costs(there will be no increase in the number of jobs, and the new equipment will be operated using existing human resources);

The straight-line method was used to determine the depreciation rate for fixed assets;

Due to the lack of relevant data to build a model of the system services market, the calculations assumed that no such activity existed.

To assess the required capital investment costs (CAPEX), a catalogue of district heating technologies was developed [

32]. Key costing curves from the catalogue are depicted in [

11]. In addition, data were used from [

31], from local vendors, and in some cases from engineering companies. The data from different years were indexed using the Chemical Engineering Plant Cost Index (CEPCI). It must be noted that since all of the planned energy conversion facilities will be located at the own sites of either CMTEB or partner companies, the land purchase costs were not taken into consideration. Furthermore, it was assumed that the CAPEX related to the DHN revitalisation process will be incurred anyway, and it does not influence the investments in heat sources. The summary of capital cost estimates is given in

Table 3 and

Table 4. In phase two, in addition to the proposed heat sources, the seasonal heat storage is taken into consideration, which enables the constraints set by equation (2) to be satisfied. Without storage, it would be necessary to significantly increase the installed capacity of particular technologies, while in summer, most of the units would be idling. In addition, it should be noted that

5. Conclusions

The EED poses a serious challenge to large DH systems in terms of decarbonisation. This study presents a strategic, system-level assessment of decarbonisation pathways for the Bucharest district heating system and provides insights applicable to other large, fossil-fuel-dependent, second-generation DH systems. The results show that compliance with the EED criteria for 2028 and 2035 is achievable in principle, but only under restrictive technical and economic conditions.

The main conclusions are as follows:

Compliance with EED targets is not equivalent to system efficiency and may require operational compromises that increase costs or emissions.

Dispatchable low-carbon heat sources are essential to ensure security of supply and limit overreliance on electricity-driven technologies.

Seasonal thermal energy storage is a key enabler, but its feasible scale is limited in dense urban environments.

Modernised CHP plants remain critical transitional assets, supporting flexibility and mitigating electricity market risks.

Financial viability cannot be achieved without external support, underscoring the necessity of EU funding, regulatory incentives, and risk-sharing mechanisms.

Although the analysis shows that compliance with the EED requirements for 2035 can be achieved with relative ease through a targeted portfolio of renewable energy, waste heat, and high-efficiency cogeneration technologies, the results also indicate that further progress toward deep decarbonisation becomes significantly more challenging beyond this milestone. As the most accessible and dispatchable low-carbon resources are exhausted, additional emission reductions increasingly depend on complex system reconfiguration, large-scale energy storage, electrification, and extensive coordination across sectors and stakeholders. This confirms that incremental, technology-by-technology approaches are insufficient and that multidimensional, holistic strategic planning is indispensable. Such planning must simultaneously address network transformation, heat demand reduction, market integration, governance structures, and social acceptance. A common feature emerging from both this study and comparable transition strategies is the growing emphasis on energy harvesting, systematic recovery of low-grade renewable and waste heat dispersed across the urban environment, which increasingly defines the backbone of long-term district heating decarbonisation pathways.

In addition to the modernisation of existing production facilities and networks, and the integration of multiple distributed heat sources, it is recommended that future activities concentrate on transitioning to fourth-generation (4GDH) standards and gradually reducing the temperature in the DHN. Network performance studies indicate that Bucharest has considerable potential for this transition, given the oversized pipeline diameters and the temperature difference of 30-40 K between the primary and secondary networks. This has, however, not been addressed in this study and left for future work.

The socio-economic dimension is equally critical. Residential heat tariffs are heavily subsidised, creating a fiscal burden on the municipality but protecting low-income consumers. This policy complicates investment cost recovery and discourages energy efficiency. At the same time, heat affordability remains politically sensitive, making social dialogue essential for a just transition.

Overall, the decarbonisation of large DH systems should be understood as a multidimensional socio-technical transition rather than a purely technological upgrade. Effective transition strategies must integrate infrastructure renewal, system flexibility, spatial planning, governance coordination, and long-term policy alignment.

Future work will focus on uncertainty and sensitivity analyses of energy and CO₂ price trajectories, detailed modelling of network temperature reduction and building-side adaptations, assessment of business models for waste heat integration, and broader environmental and social impact evaluations. Further research will also examine the replicability of the proposed methodological framework across other metropolitan DH systems in Central and Eastern Europe.