Submitted:

05 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

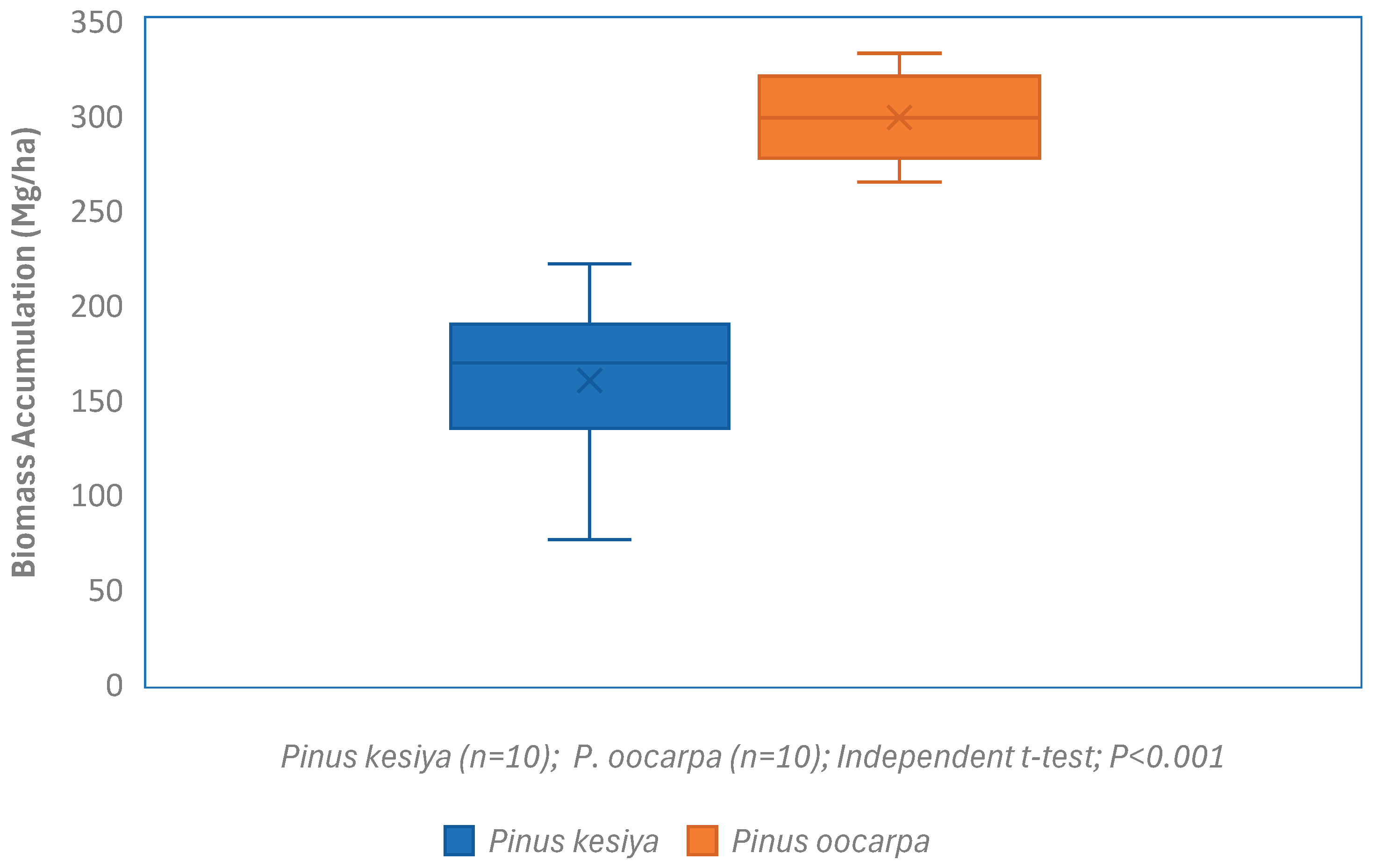

Forest ecosystems are vital to global carbon cycling as sinks or sources, while fast-growing, adaptable pines such as P. kesiya and P. oocarpa are central to national carbon sequestration efforts. This study was aimed at determining biomass accumulation variations and carbon stock dynamics between these two species at the age of 16 years in the Viphya Plantations, a prominent timber producing area in northern Malawi. Following the systematic sampling, forest inventory data was collected from 20 circular plots of 0.05 ha each. Above and below ground biomass was estimated using generic allometric models for pine species. Findings indicate that there were significant (P<0.001) differences in biomass accumulation and carbon sequestration between P. oocarpa and P. kesiya plantations. P. oocarpa accumulated more biomass (298.86±12.09 Mgha-1) than P. kesiya (160.13±23.79 Mgha-1). Furthermore, P. oocarpa plantation had a higher annual carbon sequestration (32.22±1.30 tCO2e/ha/yr) as compared to P. kesiya plantation (17.26±2.56 tCO2e/ha/yr). In addition, the uncertainty was less than 1% and fit within the IPCC’s recommended range (<15%). Therefore, the study has demonstrated that species selection should match management objectives: P. oocarpa maximizes short-to-medium term carbon sequestration and productivity, while P. kesiya supports long-term soil carbon stability. Hence, integrating both optimizes carbon benefits.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

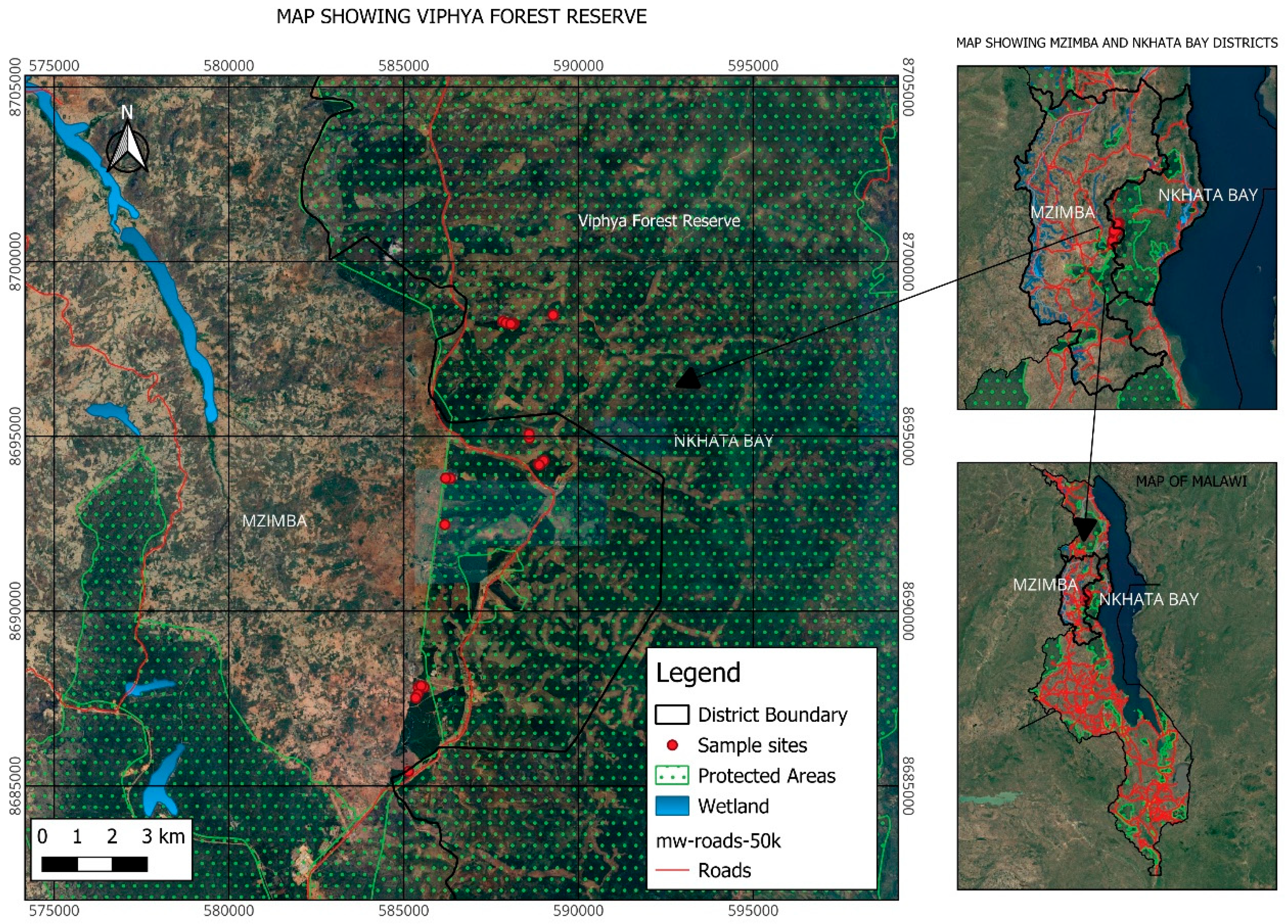

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Sampling and Data Collection

2.3. Estimation of Biomass, Carbon dynamics, and Uncertainty

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Above and Below Biomass Accumulation of P. kesiya and P. oocarpa Plantations at the age of 16 Years

3.2. Annual Carbon Sequestration for P. kesiya and P. oocarpa Plantations at the age of 16 Years

3.3. Uncertainty Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Missanjo, E.; Kadzuwa, H. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Mitigation Measures within the Forestry and Other Land Use Subsector in Malawi. International Journal of Forestry Research 2021, 2021, 5561162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukoski, J. J.; Cook-Patton, S. C.; Melikov, C.; Ban, H.; Chen, J. L.; Goldman, E. D.; Harris, N. L.; Potts, M.D. Rates and drivers of aboveground carbon accumulation in global monoculture plantation forests. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomte, L.; Shah, S. K.; Mehrotra, N.; Saikia, A.; Bhagabati, A.K. Dendrochronology in the tropics using tree-rings of Pinus kesiya. Dendrochronologia 2023, 78, 126070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malata, H.; Ngulube, E. S.; Missanjo, E. Site Specific Stem Volume Models for Pinus patula and Pinus oocarpa. International Journal of Forestry Research 2017, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamala, F.D.; Sakagami, H.; Oda, K.; Matsumura, J. Wood Density and Growth Ring Structure of Pinus Patula Planted in Malawi. IAWA Journal 2013, 34, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missanjo, E.; Matsumura, J. Multiple-Trait Selection Index for Simultaneous Improvement of Wood Properties and Growth Traits in Pinus kesiya Royle ex Gordon in Malawi. Forests 2017, 8, 96. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4907/8/4/96. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, B.; Lee, D.; Choi, I. Growth Monitoring of Korean White Pine (Pinus koraiensis) Plantation by Thinning Intensity. Journal of Korean Society of Forest Science 2014, 103, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboa-Murias, M. Á.; Rodríguez-Soalleiro, R.; Merino, A.; Álvarez-González, J. G. Temporal variations and distribution of carbon stocks in aboveground biomass of radiata pine and maritime pine pure stands under different silvicultural alternatives. Forest Ecology and Management 2006, 237, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndema, A.; Missanjo, E. Tree Growth Response of Pinus oocarpa Along Different Altitude in Dedza Mountain Forest Plantation. Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries 2015, 4, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, E.; Zenni, R.; Hay, J. A new invasive species in South America: Pinus oocarpa Schiede ex Schltdl. BioInvasions Records 2014, 3, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, E.; Missanjo, E.; Kadzuwa, H. Variation of Wood Density and Shrinkage Characters of Pinus oocarpa in Malawi. Journal of Global Ecology and Environment 2023, 18, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munthali, E; Mwale, F; Katengeza, E; Kamangadazi, F; Missanjo, E; Kadzuwa, H. Variations in Soil Organic Carbon Accumulation Between Pinus kesiya and Pinus oocarpa at Viphya Plantations in Malawi. Wiley International Journal of Forestry Research 2025, 2025, 6694454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missanjo, E.; Kamanga-Thole, G. Effect of first thinning and pruning on the individual growth of Pinus patula tree species. Journal of Forestry Research 2015, 26, 827–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missanjo, E.; Kadzuwa, H. Activity Data and Emission Factor for Forestry and Other Land Use Change Subsector to Enhance Carbon Market Policy and Action in Malawi. Journal of Environmental Protection 2024, 15, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadzuwa, H.; Missanjo, E. Modelling Above-ground Biomass Using Machine Learning Algorithm: Case Study Miombo Woodlands of Malawi. Journal of Global Ecology and Environment 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadzuwa, H.; Missanjo, E. Effect of Leaf Phenology, Topography and Wind Speed on Forest Canopy Height and Above Ground Biomass Estimation using Optical UAV Data in Malawi’s Miombo Woodlands. Journal of Global Ecology and Environment 2022, 16, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadzuwa, H.; Missanjo, E. Comparison of Varied Forest Inventory Methods and Operating Procedures for Estimating Above-Ground Biomass in Malawi’s Miombo Woodlands. Journal of Global Ecology and Environment 2022, 16, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missanjo, E.; Utila, H.; Munthali, M.; Mitembe, W. Modelling of climate conditions in forestry vegetation zones in Malawi. World Journal of Advanced Research and Review 2019, 1, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamangadazi, F.; Mwabumba, L.; Missanjo, E. The Potential of Selective Harvesting in Mitigating Biomass and Carbon Loss in Forest Co-management Block in Liwonde Forest Reserve, Malawi. Scholars Academic Journal of Biosciences 2016, 4, 716–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missanjo, E.; Kamanga-Thole, G.; Ndema, A. Biomass and Carbon Stock Estimation for Miombo Woodland in Selected Part of Chongoni Forest Reserve, Dedza, Malawi. International Journal of Forestry and Horticulture 2015, 1, 12–17. Available online: https://www.arcjournals.org/pdfs/ijfh/v1-i1/3.pdf.

- Missanjo, E.; Kamanga-Thole, G. Estimation of Biomass and Carbon stock for Miombo Woodland in Dzalanyama Forest Reserve, Malawi. Research Journal of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences 2015, 3, 7–12. Available online: https://www.isca.me/AGRI_FORESTRY/Archive/v3/i3/2.ISCA-RJAFS-2014-074.php.

- Chitawo, M.L. Systems approach in developing a model for sustainable production of bioenergy in Malawi . PhD Thesis, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, 2018. Available online: https://scholar.sun.ac.za:443/handle/10019.1/103540.

- Kafakoma, R.; Mataya, B. Timber value chain analysis for the Viphya Plantations; Training Support for Partners (TSP): Lilongwe, Malawi, 2009; Available online: https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/G03138.pdf.

- Ngulube, E.; Brink, M.; Chirwa, P. Productivity and cost analysis of semi-mechanised and mechanised systems on the Viphya forest plantations in Malawi. Southern Forests: A Journal of Forest Science 2014, 76, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, Y.; Takao, G.; Sato, T.; Toriyama, J. REDD-Plus Cookbook.; REDD Research and Development Center, Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute: Tsukuba, 2012; Available online: https://redd.ffpri.go.jp/pub_db/publications/cookbook/_img/cookbook_en.pdf.

- FAO. Global Forest Resource Assessment: Progress towards Sustainable Forest Management; Food and Agriculture Organization Forestry Paper; FAO: Rome, 2005; Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/a0400e/a0400e00.htm.

- Sierra, C.A.; Del Valle, J.I.; Orrego, S.A.; Moreno, F.H.; Harmon, M.E.; Zapata, M.; Colorado, G.J.; Herrera, M.A.; Blara, W.; Restrepo, D.E.; Berrouet, L.M.; Loaiza, L.M.; Benjumea, J.F. Total Carbon Stocks in a Tropical Forest Landscape of the Porce Region, Colombia. Forest Ecology and Management 2007, 243, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, N.; Mehrotra, R.; Mehrotra, S. Carbon biosequestration strategies: a review. Carbon Capture Science & Technology 2022, 4, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagodzinski, A. M.; Ziółkowski, J.; Warnkowska, A.; Prais, H. Tree Age Effects on Fine Root Biomass and Morphology over Chronosequences of Fagus sylvatica, Quercus robur and Alnus glutinosa Stands. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusk, V.; Niinemets, Ü.; Valladares, F. A major trade-off between structural and photosynthetic investments operative across plant and needle ages in three Mediterranean pines. Tree Physiology 2018, 38, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baishya, R.; Barik, S.K. Estimation of tree biomass, carbon pool and net primary production of an old-growth Pinus kesiya Royle ex. Gordon forest in north-eastern India. Annals of Forest Science 2011, 68, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, J.M.; Morales, B.; Lima, E.M.; de Bastos, F.; Morales, C. A. S.; de Araújo, E. F. Soil morphological, physical and chemical properties affecting Eucalyptus spp. Productivity on Entisols and Ultisols. Soil and Tillage Research 2023, 226, 105563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, C; Constandache, C; Dinca, L; Murariu, G; Badea, NO; Tudose, NC; Marin, M. Pine afforestation on degraded lands: a global review of carbon sequestration potential. Front. For. Glob. Change 2025, 8, 1648094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salekin, S.; Dickinson, Y.L.; Bloomberg, M.; Meason, D.F. Carbon sequestration potential of plantation forests in New Zealand no single tree species is universally best. Carbon Balance and Management 2024, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Ding, G. Estimation of changes in carbon sequestration and its economic value with various stand density and rotation age of Pinus massoniana plantations in China. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 16852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Duan, Y. Predicting carbon storage jointly by foliage and soil parameters in Pinus pumila stands along an elevation gradient in great Khingan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, F.; Seim, A.; Hu, M.; Akkemik, Ü.; Kopabayeva, A. Global warming leads to growth increase in Pinus sylvestris in the Kazakh steppe. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 553, 121635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zeng, D. H.; Lei, Z.; Li, X.; Lin, G. Microbial properties determine dynamics of topsoil organic carbon stocks and fractions along an age sequence of Mongolian pine plantations. Plant Soil 2023, 483, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Gao, L. The impact of carbon trade on the management of short-rotation forest plantations. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 62, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollinson, C.R.; Kaye, M.W.; Canham, C. D. Interspecific variation in growth responses to climate and competition of five eastern tree species. Ecology 2016, 97, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Węgiel, A.; Polowy, K. Aboveground carbon content and storage in mature scots pine stands of different densities. Forests 2020, 11, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Jin, G. Impacts of stand density on tree crown structure and biomass: A global meta-analysis. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2022, 326, 109181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, M.T.L.; Schmidt, S.; Shoo, L.P. A meta-analytical global comparison of aboveground biomass accumulation between tropical secondary forests and monoculture plantations. Forest Ecology and Management 2013, 291, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, B.J.; Sass, E.M.; Gamarra, J.G.P.; Campbell, J.L.; Wayson, C.; Olguín, M.; Carrillo, O.; Yanai, R.D. Uncertainty in REDD+ carbon accounting: a survey of experts involved in REDD+ reporting. Carbon Balance and Management 2024, 19, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, H.C.; Tan, N.H.L.; Zheng, Q.; Lim, A.J.Y.; Sreekar, R.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Sarira, T.V; De Alban, J.D.T.; Tang, H.; Friess, D.A.; Koh, L.P. Uncertainties in deforestation emission baseline methodologies and implications for carbon markets. Nature communications 2023, 14, 8277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarrete-Poyatos, M.A.; Navarro-Cerrillo, R.M.; Lara-G´omez, M.A.; Duque-Lazo, J.; Varo, M.A.; Rodriguez, G.P. Assessment of the Carbon Stock in Pine Plantations in Southern Spain Trough ALS Data and K Nearest Neighbour Algorithm Based Models. Geosciences 2019, 9, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF). Carbon Fund Methodological Framework. Forest Carbon Partnership Facility, Washington DC: The World Bank. 2016. Available online: https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/carbon-fund-methodological-framework.

- Gizachew, B; Duguma, LA. Forest carbon monitoring and reporting for REDD +: What future for Africa? Environ Manage 2016, 58, 922–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Pinus species plantation |

Annual Carbon Sequestration (tCO2e/ha/yr) |

Uncertainty (%) |

|---|---|---|

| P. oocarpa | 32.22±1.30a | 0.56 |

| P. kesiya | 17.26±2.56b | 2.06 |

| Mean | 24.74±2.84 | 2.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).