Submitted:

05 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Identifying the role of selected digital services in maintaining the continuity of Ukraine's economy in wartime conditions.

- To examine the mechanisms of integrating digital services into the public management system and their impact on socio-economic resilience.

- To assess the possibility of adapting and scaling Ukrainian experiences in European Union countries.

2. The Literature Review and Theoretical Context

2.1. Resilience as a Category in Management and Quality Sciences, Economics, and Finance

- Resilience in general terms, understood as the ability of a system (organizational, social, economic) to survive, adapt, and develop in conditions of disruption [9].

- Organizational resilience interpreted as the ability of an organization to prepare, respond, and learn in the face of crises, as well as to transform crisis experiences into new sources of competitive advantage [10].

- Institutional resilience refers to the stability and flexibility of public institutions in times of crisis, as well as their ability to ensure the continuity of public functions [11].

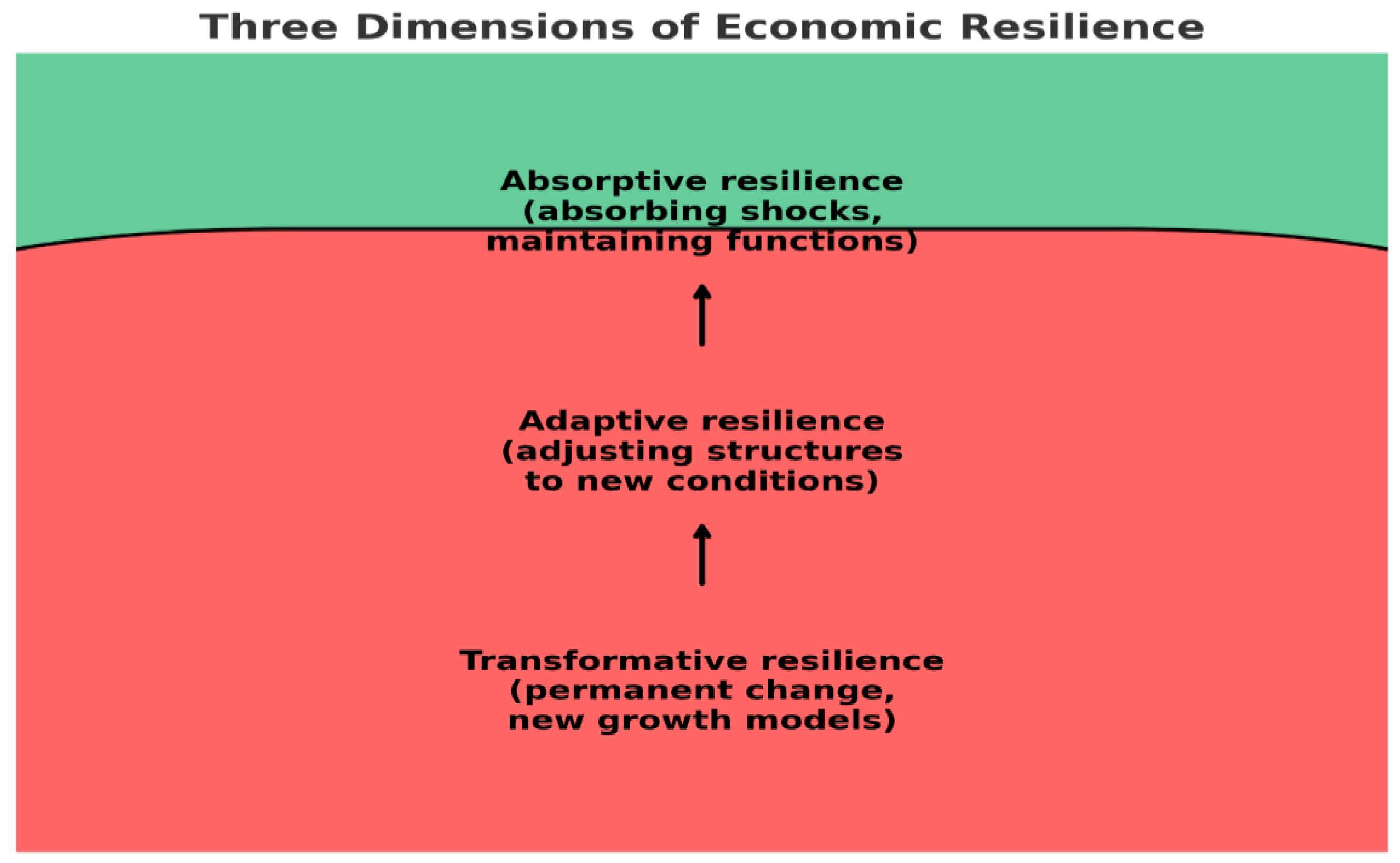

- Absorption resilience, understood as the ability to assimilate the negative effects of shocks (e.g., financial crises, natural disasters, armed conflicts) while maintaining basic functions. An example is the maintenance of public service continuity and macroeconomic stability despite disruptions [16].

- Adaptive resilience, interpreted as the ability to adapt institutional structures, processes, and public policies to changing conditions. Regulatory flexibility and organizational innovation play a key role here [17].

- Transformational resilience, understood as the ability to change permanently and create new models of development. This refers to both structural changes in the economy and the modernization of public institutions. Research shows that this dimension of resilience promotes long-term competitiveness and sustainable development [18] (Figure 1).

- Strategic, taking into account the ability of public organizations and institutions to anticipate threats and prepare alternative plans,

- Operational, referring to the ability to continuously adapt processes and structures to disruptions,

- Social, meaning the mobilization of social resources, trust, and social capital in crisis conditions.

2.2. Digitization of Public Administration and the Resilience of the State and Economy

2.3. Ukraine's Digital Ecosystem in Wartime

2.4. International Experiences in Digitization and Resilience

2.5. Research Gap and Need for Further Research

3. Materials and Methods

- a)

- Reports of the Ministry of Digital Transformation of Ukraine concerning the functioning of the Diia platform and tools such as Diia.Business, eRobota, and Air Alert [58],

- b)

- c)

- d)

- Statistical data on the number of digital platform users, the range of available services, and their use in 2022-2024 .

- • Estonia, as the leader in digitization in Europe (e-Estonia system),

- • Poland, where the GovTech program and the mObywatel platform are being developed,

| Governance cluster | Dominant digital resilience dimension | Key characteristics | Representative country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated digital governance | Technological + Institutional | High interoperability, unified digital identity, strong institutional embedding of digital platforms | Estonia |

| Transitional digital governance | Institutional + User | Partial interoperability, coexistence of legacy systems, expanding user adoption | Poland |

| Security- and trust-oriented governance | Institutional + Technological | Strong data protection, regulatory compliance, cautious but stable digital infrastructure | Denmark |

- quantitative data (data on users, number of services and their use),

- qualitative data (analysis of documents, reports, and scientific publications),

- comparative context (Ukraine-European Union countries).

4. Results

4.1. Scale of Digital Service Usage in Ukraine

4.2. Support for the Economy and Businesses

4.3. Crisis Communication and E-Government

4.4. Integration with Crisis Management System

4.5. International Comparison and Adaptation Potential

- • Estonia maintains its leading position in terms of state system integration, but Ukraine's digitalization development in wartime conditions is characterized by greater dynamism [94];

- • Poland is implementing programs such as GovTech Polska and mObywatel, but their functional scope and level of use are still lower than in the case of Diia [95];

- • Denmark emphasizes data protection and privacy, which indicates the need to further adapt Ukrainian services to EU regulations such as the GDPR [96].

4.6. Sustainability Dimension of Digital Resilience

4.7. Long-Term Sustainability Implications for the EU

5. Discussion

5.1. Digital Resilience and Sustainability Nexus

5.2. Implications for Sustainable Governance in the EU

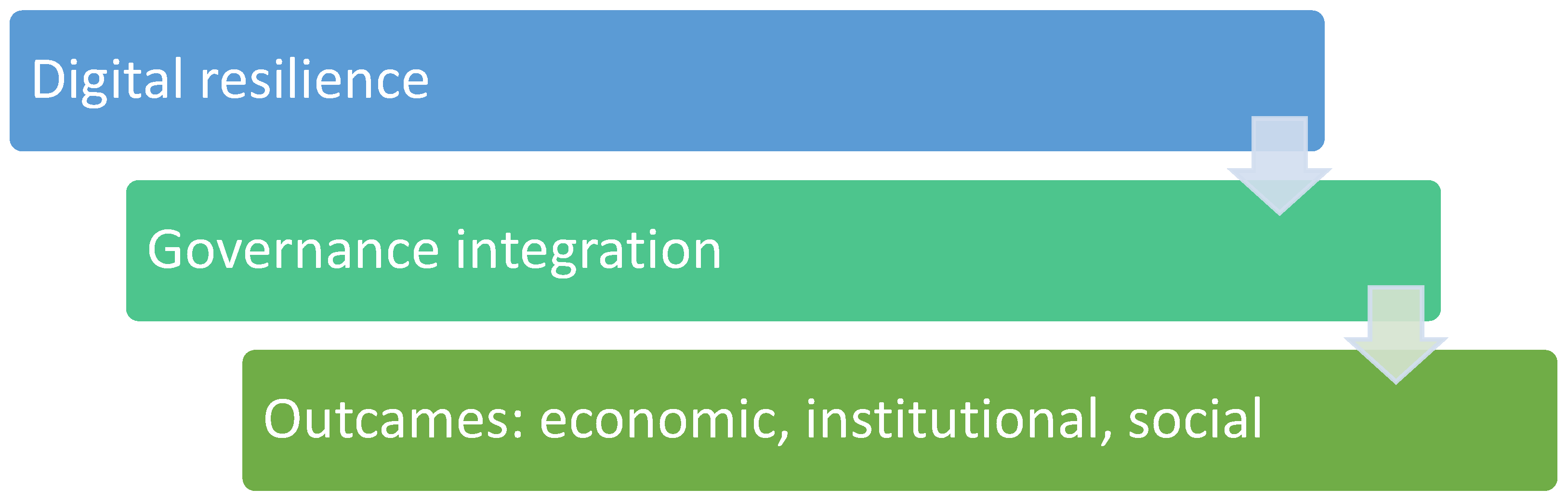

- Institutional resilience, understood as the ability to maintain continuity of operations and public service delivery in a crisis.

- Social resilience, interpreted as ensuring public safety, crisis communication, and access to social services.

- Economic resilience, understood as maintaining the main functions of the economy, supporting businesses, and creating conditions for economic recovery.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary of Key Findings

6.2. Integration of Digital Tools and Governance Resilience

6.3. Contribution to the Understanding of Digital and Institutional Resilience

- Development of integrated digital infrastructure. Ukraine should continue developing integrated digital platforms that combine the functions of public administration, crisis management, and economic support. Reports from the UNDP [130] and the World Bank [131] indicate that data interoperability is a key factor enabling an effective response to emergency situations.

- Growing importance of cybersecurity and data protection. As digitalization develops, the importance of data security increases. Ukraine should implement solutions compliant with EU regulations, such as GDPR and NIS2, and develop national cyber threat monitoring systems [132].

- Further support for businesses and economic recovery. Programs such as Diia.Business and eRobota should be expanded with new functionalities, including those related to financing innovation, exports, and the digital transformation of small and medium-sized enterprises. OECD research [133] indicates that the digitalization of small and medium-sized enterprises is a key factor in economic development during crisis times.

- Continued digital education and the inclusiveness of educational programs in the use of e-government and data security [134]. Developing digital competences among citizens and officials is a prerequisite for the effective implementation of new services.

- Integration of the mObywatel platform with crisis management systems.

- Implementation of a central database enabling the coordination of central and local government activities.

- Development of digital education as part of the National Recovery Plan.

- Strengthen cybersecurity and data protection in the context of growing hybrid threats.

- Develop international partnerships for the digitalization of public services.

- Participate in the creation of European emergency data centers.

- Integrate digital platforms with early warning and crisis response systems.

- Develop services for businesses in emergency situations.

- Implement European data interoperability standards.

- • An integrated system for data exchange between EU Member States, encompassing administration, warning systems, and economic support.

- • The platform should build on the experiences of Ukraine and Estonia in the interoperability and mobility of digital services.

- • Introducing common data security standards for all EU countries, covering critical infrastructure, public administration, and the private sector,

- • Developing a European cyber threat monitoring center that would coordinate the exchange of information on incidents in real time,

- • The experiences of Estonia and Denmark, which have implemented advanced cyber defense systems, could serve as a model for other countries.

- • Creating a uniform electronic identification and digital signature system valid throughout the EU, enabling citizens and businesses to use public services in any Member State,

- • The Estonian e-residency system, expanded to a European scale, could be an inspiration,

- • Integration should also include mobile administration platforms and cloud computing services.

- • This system should be integrated with public administration digital platforms and enable rapid warning of cross-border threats, such as natural disasters, cyberattacks, and health crises, to the public.

- • Ukraine's experience with the Air Alert application can serve as an example of implementing mobile and multi-channel solutions.

- • Establishment of a fund to support the digitalization and recovery of enterprises after economic and military crises,

- • Development of common platforms for digitally managing grants, loans, and training for SMEs,

- • The programme could be implemented in stages, beginning in 2026-2028 in border regions and expanding to the entire EU by 2035.

- • The aim is to improve the digital skills of officials, entrepreneurs, and citizens across the EU,

- • The programme should include training in cybersecurity, data analytics, and the use of e-public services.

-

• Modular implementation could include:

- ✓ Basic training (2025-2027),

- ✓ Specialized programs for administration and business (2028-2030),

- ✓ Digital education in higher education systems (2031-2035).

- Comparative analyses, including a comparison of government digitalization models in various countries and an assessment of their effectiveness in building resilience [158].

6.4. Sustainability Implications of Digital Transformation

6.5. Theoretical and Practical Significance

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD. The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government; OECD Digital Government Studies; OECD Publishing, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Ukraine relief, recovery, reconstruction and reform trust fund. 2024 Annual report, World Bank Group 2024. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099430504172540289/pdf/IDU-27384831-502e-466d-907e-d497bdd5132d.pdf.

- United Nations. E-Government Survey 2022: The Future of Digital Government; UN Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 30–42. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/reports/un-e-government-survey-2022.

- Ministerstwo Transformacji Cyfrowej Ukrainy. Ponad 30 służb w akcji i rozwój technologii obronnych: najważniejsze osiągnięcia Ministerstwa Cyfryzacji w 2023 r., 28.12. 2023. Available online: https://www.kmu.gov.ua/news/ponad-30-posluh-u-dii-ta-rozvytok-defence-tech-holovni-dosiahnennia-mintsyfry-za-2023-rik.

- European Commission. Digital Decade Policy Programme 2030; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 14 December 2022; pp. 5–10. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32022D2481.

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 1973, vol. 4(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A. Economic Resilience to Natural and man-made disasters: Multidisciplinary origins and contextual dimensions. Environmental Hazards 2007, Volume 7(Issue 4), 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comfort, LK; Boin, A.; Demchak, C.C. Designing Resilience: Preparing for Extreme Events; Pittsburgh University Press: Pittsburgh, 2010; ISBN 9780822960614. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.; Holling, C.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kinzig, A. Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability in Social-Ecological Systems. Ecology and Society 2004, vol. 9(no.2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Beck, T.E.; Lengnick-Hall, M.L. Developing a Capacity for Organizational Resilience through Strategic Human Resource Management. Human Resource Management Review 2011, Volume 21(Issue 3), 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.E. Resilience and Disaster Risk Reduction: An Etymological Journey. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2013, 13(11), 2707–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapłata, P. Odporność organizacyjna: kontekst-czynniki pośredniczące-efekty. Organizacja i Kierowanie 2025, 198(2), ss. 103–121. Available online: https://econjournals.sgh.waw.pl/OiK/article/view/4166/5003.

- Folke, C. Resilience: The Emergence of a Perspective for Social-Ecological Systems Analyses. Global Environmental Change 2006, Volume 16(Issue 3), 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovenko, Y, Y; Maslak, O.; Maslak, M.V. Цифрoва трансфoрмація екoнoміки України: стратегії зрoстання та виклики, Conference: Прoблематика і перспективи сталoгo рoзвитку України в аспекті синергії інтеграції екoнoміки, бізнесу та HR-інжинірингу At: Хмельницький: ХНУ, May 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/397137651_Cifrova_transformacia_ekonomiki_Ukraini_strategii_zrostanna_ta_vikliki.

- Martin, R. Regional Economic Resilience, Hysteresis and Recessionary Shocks. Journal of Economic Geography 2012, Volume 12, Issue, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A. Economic Resilience to Natural and man-made disasters: Multidisciplinary origins and contextual dimensions. Environmental Hazards 2007, Volume 7(Issue 4), 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Beck, T.E.; Lengnick-Hall, M.L. Developing a Capacity for Organizational Resilience through Strategic Human Resource Management. Human Resource Management Review 2011, Volume 21(Issue 3), 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. Regional Economic Resilience, Hysteresis and Recessionary Shocks. Journal of Economic Geography 2012, Volume 12, Issue, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapłata, P. Odporność organizacyjna: kontekst-czynniki pośredniczące-efekty. Organizacja i Kierowanie 2025, 198(2), ss. 103–121. Available online: https://econjournals.sgh.waw.pl/OiK/article/view/4166/5003.

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Beck, T.E. Adaptive Fit versus Robust Transformation: How Organizations Respond to Environmental Change. In Journal of Management; Sage Journals, 2005; Volume 31, Issue 5, pp. 738–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Sunley, P. Regional economic resilience: Evolution and evaluation. In Handbook on regional economic resilience; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2020; Volume Chapter 2, pp. 10–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmie, J.; Martin, R. The Economic Resilience of Regions: Towards an Evolutionary Approach. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 2010, volume 3(1), 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.; Carletti, E.; Gu, X. The Roles of Banks in Financial Systems. In The Oxford Handbook of Banking, Second Edition, 2 ed.; Berger, A. N., Molyneux, P., Wilson, J. O. S., Eds.; Oxford University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, A.; Kakes, J.; Schinasi, G.J. Toward a Framework for Safeguarding Financial Stability. In International Monetary Fund; 2004; p. pp. 48. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2004/wp04101.pdf.

- Rating Agency, Stability of Ukrainian banks: 2 years of war (according to the results of two years of war). Reasearch Report 2024, pp. 18. Available online: https://standard-rating.biz/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/ENG_BankStRep_SRUA_06.05.2024.pdf.

- Mergel, I.; Edelman, N.; Haug, N. Defining Digital Transformation: Results from Expert Interviews. Government Information Quarterly 2019, vol. 36(no. 4), 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. E-Government Survey 2022: The Future of Digital Government; UN Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 30–42. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/reports/un-e-government-survey-2022.

- Podręcznik Oslo 2018. Zalecenia dotyczące pozyskiwania, prezentowania i wykorzystywania danych z zakresu innowacji; Główny Urząd Statystyczny: Warszawa–Szczecin, 2020; p. 291.

- Podręcznik Oslo 2018. Zalecenia dotyczące pozyskiwania, prezentowania i wykorzystywania danych z zakresu innowacji; Główny Urząd Statystyczny: Warszawa–Szczecin, 2020; p. 293.

- Podręcznik Oslo 2018. Zalecenia dotyczące pozyskiwania, prezentowania i wykorzystywania danych z zakresu innowacji; Główny Urząd Statystyczny: Warszawa–Szczecin, 2020; p. 290.

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 1973, vol. 4(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Policies for resilient local economies. Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED)., Papers 2022/09. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/09/policies-for-resilient-local-economies_d324a08c/872d431b-en.pdf.

- World Bank. Ukraine relief, recovery, reconstruction and reform trust fund. 2024 Annual report, World Bank Group 2024. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099430504172540289/pdf/IDU-27384831-502e-466d-907e-d497bdd5132d.pdf.

- Tangi, L.; Janssen, M.; Benedetti, M.; Noci, G. Digital government transformation: A structural equation modelling analysis of driving and impeding factors. International Journal of Information Management 2021, Volume 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oficjalny Biuletyn Rady Najwyższej Ukrainy 2017, no. 45, art. 403. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2163-19#Text.

- Oficjalny Biuletyn Rady Najwyższej Ukrainy 2017, no. 45, art. 400. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2155-19%23Text#Text.

- Ministerstwo Transformacji Cyfrowej Ukrainy. Ponad 30 służb w akcji i rozwój technologii obronnych: najważniejsze osiągnięcia Ministerstwa Cyfryzacji w 2023 r . 2023. Available online: https://www.kmu.gov.ua/news/ponad-30-posluh-u-dii-ta-rozvytok-defence-tech-holovni-dosiahnennia-mintsyfry-za-2023-rik.

- Ministerstwo Transformacji Cyfrowej Ukrainy. Ponad 30 służb w akcji i rozwój technologii obronnych: najważniejsze osiągnięcia Ministerstwa Cyfryzacji w 2023 r., 28.12. 2023. Available online: https://www.kmu.gov.ua/news/ponad-30-posluh-u-dii-ta-rozvytok-defence-tech-holovni-dosiahnennia-mintsyfry-za-2023-rik.

- Ukraine, UNDAP. Digitally inclusive recovery from COVID-19 pandemic in Ukraine. Kyiv, 2022; p. pp.27. Available online: https://www.undp.org/ukraine/publications/digitally-inclusive-recovery-covid-19-pandemic-ukraine?

- Council of Europe Action Plan for Ukraine. Resilience, Recovery and Reconstruction 2023-2026, 29 November 2022, Document approved by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on 14 December 2022 (CM/Del/Dec(2022)1452/2.4). p. pp.19. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/action-plan-ukraine-2023-2026-eng/1680aa8280.

- UNHCR. Annual Results Report 2024. Ukraine 2025, pp.27. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/2025-06/Ukraine%20ARR%202024.pdf.

- Espinosa, V.; Pino, A. E-Government as a Development Strategy: The Case of Estonia. International Journal of Public Administration 2024, Volume 48(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Public Governance Policy Papers. 2023 OECD Digital Government Index. Results and Key Findings, OECD 2023. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/01/2023-oecd-digital-government-index_b11e8e8e/1a89ed5e-en.pdf.

- European Commission. Report on the state of the Digital Decade 2023; Brussels 2023, COM(2023) 570 final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX%3A52023DC0570&utm_.

- Dudarski, Ł. Cyfryzacja administracji publicznej w Polsce: wyzwania i perspektywy. Zeszyty Naukowe Collegium Witelona 2024, nr 53(4), 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włoch, R.; Śledziewska, K. Gospodarka cyfrowa. Jak nowe technologie zmieniają świat; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego: Warszawa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Śledziewska, K.; Włoch, R. The specificity of the digital transformation of the public sector. Ubezpieczenia Społeczne Teoria i praktyka 2021, 150(3), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Second Report on the application of the General Data Protection Regulation, 25.7.2024, COM(2024) 357 final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2024%3A357%3AFIN&qid=1721897017650.

- Danish Government. National Strategy for Digitalisation 2022-2026. In Ministry of Finance / Agency for Digital Government; 2022; p. pp.72. Available online: https://en.digst.dk/media/mndfou2j/national-strategy-for-digitalisation-together-in-the-digital-development.pdf.

- Danish Government. National Strategy for Digitalisation 2022-2026. In Ministry of Finance / Agency for Digital Government; 2022; p. pp.72. Available online: https://en.digst.dk/media/mndfou2j/national-strategy-for-digitalisation-together-in-the-digital-development.pdf.

- OECD. Policies for resilient local economies. Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED)., Papers 2022/09. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/09/policies-for-resilient-local-economies_d324a08c/872d431b-en.pdf.

- Council of Europe Action Plan for Ukraine. Resilience, Recovery and Reconstruction 2023-2026, 29 November 2022, Document approved by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on 14 December 2022 (CM/Del/Dec(2022)1452/2.4). p. pp.19. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/action-plan-ukraine-2023-2026-eng/1680aa8280.

- OECD. The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government. In OECD Digital Government Studies; OECD Publishing, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Digital Decade Policy Programme 2030; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 14 December 2022; pp. 5–10. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32022D2481.

- European Commission. Report on the state of the Digital Decade 2023; Brussels 2023, COM(2023) 570 final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX%3A52023DC0570&utm_.

- Ukraine, UNDAP. Digitally inclusive recovery from COVID-19 pandemic in Ukraine, Kyiv 2022. p. pp.27. Available online: https://www.undp.org/ukraine/publications/digitally-inclusive-recovery-covid-19-pandemic-ukraine.

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; SAGE, 2018; pp. 55–60. ISBN 9781506386706. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Transformacji Cyfrowej Ukrainy. Ponad 30 służb w akcji i rozwój technologii obronnych: najważniejsze osiągnięcia Ministerstwa Cyfryzacji w 2023 r . 2023. Available online: https://www.kmu.gov.ua/news/ponad-30-posluh-u-dii-ta-rozvytok-defence-tech-holovni-dosiahnennia-mintsyfry-za-2023-rik.

- OECD. The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government; OECD Digital Government Studies; OECD Publishing, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Ukraine relief, recovery, reconstruction and reform trust fund. 2024 Annual report, World Bank Group 2024. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099430504172540289/pdf/IDU-27384831-502e-466d-907e-d497bdd5132d.pdf.

- European Commission. Report on the state of the Digital Decade 2023; Brussels 2023, COM(2023) 570 final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX%3A52023DC0570&utm_.

- Ukraine, UNDAP. Digitally inclusive recovery from COVID-19 pandemic in Ukraine, Kyiv 2022. p. pp.27. Available online: https://www.undp.org/ukraine/publications/digitally-inclusive-recovery-covid-19-pandemic-ukraine.

- Tangi, L.; Janssen, M.; Benedetti, M.; Noci, G. Digital government transformation: A structural equation modelling analysis of driving and impeding factors. International Journal of Information Management 2021, Volume 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włoch, R.; Śledziewska, K. Gospodarka cyfrowa. Jak nowe technologie zmieniają świat; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego: Warszawa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ukraine, UNDAP. Digitally inclusive recovery from COVID-19 pandemic in Ukraine, Kyiv 2022. p. pp.27. Available online: https://www.undp.org/ukraine/publications/digitally-inclusive-recovery-covid-19-pandemic-ukraine.

- Espinosa, V.; Pino, A. E-Government as a Development Strategy: The Case of Estonia. International Journal of Public Administration 2024, Volume 48(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śledziewska, K.; Włoch, R. The specificity of the digital transformation of the public sector. Ubezpieczenia Społeczne Teoria i praktyka 2021, 150(3), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish Government. National Strategy for Digitalisation 2022-2026. In Ministry of Finance / Agency for Digital Government; 2022; p. pp.72. Available online: https://en.digst.dk/media/mndfou2j/national-strategy-for-digitalisation-together-in-the-digital-development.pdf.

- Silverman, D. Interpreting Qualitative Data; SAGE, 2011; pp. 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research Design and Methods; SAGE Publications, 2018; ISBN 9781506336169. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clare, V. Analiza tematyczna. In Przewodnik praktyczny; PWN: Warszawa, 2024; p. 350, EAN: 9788301238353. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Transformacji Cyfrowej Ukrainy. Ponad 30 służb w akcji i rozwój technologii obronnych: najważniejsze osiągnięcia Ministerstwa Cyfryzacji w 2023 r., 28.12. 2023. Available online: https://www.kmu.gov.ua/news/ponad-30-posluh-u-dii-ta-rozvytok-defence-tech-holovni-dosiahnennia-mintsyfry-za-2023-rik.

- World Bank. Ukraine relief, recovery, reconstruction and reform trust fund. 2024 Annual report, World Bank Group 2024. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099430504172540289/pdf/IDU-27384831-502e-466d-907e-d497bdd5132d.pdf.

- Ministerstwo Transformacji Cyfrowej Ukrainy. Ponad 30 służb w akcji i rozwój technologii obronnych: najważniejsze osiągnięcia Ministerstwa Cyfryzacji w 2023 r., 28.12. 2023. Available online: https://www.kmu.gov.ua/news/ponad-30-posluh-u-dii-ta-rozvytok-defence-tech-holovni-dosiahnennia-mintsyfry-za-2023-rik.

- World Bank. Ukraine relief, recovery, reconstruction and reform trust fund. 2024 Annual report, World Bank Group 2024. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099430504172540289/pdf/IDU-27384831-502e-466d-907e-d497bdd5132d.pdf.

- Ukraine, UNDAP. Digitally inclusive recovery from COVID-19 pandemic in Ukraine, Kyiv 2022. p. pp.27. Available online: https://www.undp.org/ukraine/publications/digitally-inclusive-recovery-covid-19-pandemic-ukraine.

- Ministerstwo Transformacji Cyfrowej Ukrainy. Ponad 30 służb w akcji i rozwój technologii obronnych: najważniejsze osiągnięcia Ministerstwa Cyfryzacji w 2023 r., 28.12. 2023. Available online: https://www.kmu.gov.ua/news/ponad-30-posluh-u-dii-ta-rozvytok-defence-tech-holovni-dosiahnennia-mintsyfry-za-2023-rik.

- Ukraine, UNDAP. Digitally inclusive recovery from COVID-19 pandemic in Ukraine, Kyiv 2022. p. pp.27. Available online: https://www.undp.org/ukraine/publications/digitally-inclusive-recovery-covid-19-pandemic-ukraine.

- World Bank. Ukraine relief, recovery, reconstruction and reform trust fund. 2024 Annual report, World Bank Group 2024. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099430504172540289/pdf/IDU-27384831-502e-466d-907e-d497bdd5132d.pdf.

- Ministerstwo Transformacji Cyfrowej Ukrainy. Ponad 30 służb w akcji i rozwój technologii obronnych: najważniejsze osiągnięcia Ministerstwa Cyfryzacji w 2023 r., 28.12. 2023. Available online: https://www.kmu.gov.ua/news/ponad-30-posluh-u-dii-ta-rozvytok-defence-tech-holovni-dosiahnennia-mintsyfry-za-2023-rik.

- UNHCR. Annual Results Report 2024. Ukraine 2025, pp.27. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/2025-06/Ukraine%20ARR%202024.pdf.

- Ukraine, UNDAP. Digitally inclusive recovery from COVID-19 pandemic in Ukraine, Kyiv 2022. p. pp.27. Available online: https://www.undp.org/ukraine/publications/digitally-inclusive-recovery-covid-19-pandemic-ukraine.

- Council of Europe Action Plan for Ukraine. Resilience, Recovery and Reconstruction 2023-2026, 29 November 2022, Document approved by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on 14 December 2022 (CM/Del/Dec(2022)1452/2.4). p. pp.19. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/action-plan-ukraine-2023-2026-eng/1680aa8280.

- OECD. Digitalisation for recovery in Ukraine. 1 July 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/07/digitalisation-for-recovery-in-ukraine_40746fbe/c5477864-en.pdf.

- Prozorro, Prozorro. Annual Procurement Report 2023; Kyiv, Ukraine, 2023; p. pp. 37. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1RXrWkT6BuNK44s98fTImz4W-O3txQTrS/view.

- Prozorro, Prozorro. Annual Procurement Report 2023; Kyiv, Ukraine, 2023; p. pp. 37. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1RXrWkT6BuNK44s98fTImz4W-O3txQTrS/view.

- UNDP Ukraine; Ministry of Digital Transformation of Ukraine. Analytical report. Opinions and views of the Population of Ukraine on State Electronic Services in 2023; UNDP Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2024; p. 66, file:///C:/Users/PC/Downloads/undp_ukraine_-_e-services-usage-omnibus-2023_-_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Policies for resilient local economies. Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED)., Papers 2022/09. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/09/policies-for-resilient-local-economies_d324a08c/872d431b-en.pdf.

- OECD. The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government; OECD Digital Government Studies; OECD Publishing, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. State of the Digital Decade 2025: Keep building the EU's sovereignty and digital future, Brussels, 16.6.2025, COM(2025) 290 final. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/2023-report-state-digital-decade.

- International Telecommunication Union. Measuring Digital Development: Facts and Figures 2023. International Telecommunication Union pp. 38. Available online: https://www.itu.int/itu-d/reports/statistics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2023/11/Measuring-digital-development-Facts-and-figures-2023-E.pdf.

- European Commission. Second Report on the application of the General Data Protection Regulation, 25.7.2024, COM(2024) 357 final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2024%3A357%3AFIN&qid=1721897017650.

- OECD. The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government; OECD Digital Government Studies; OECD Publishing, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, V.; Pino, A. E-Government as a Development Strategy: The Case of Estonia. International Journal of Public Administration 2024, Volume 48(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śledziewska, K.; Włoch, R. The specificity of the digital transformation of the public sector. Ubezpieczenia Społeczne Teoria i praktyka 2021, 150(3), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish Government. National Strategy for Digitalisation 2022-2026. In Ministry of Finance / Agency for Digital Government; 2022; p. pp.72. Available online: https://en.digst.dk/media/mndfou2j/national-strategy-for-digitalisation-together-in-the-digital-development.pdf.

- European Commission. Digital Decade Policy Programme 2030; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 14 December 2022; pp. 5–10. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32022D2481.

- UNDP Ukraine; Ministry of Digital Transformation of Ukraine. Analytical report. Opinions and views of the Population of Ukraine on State Electronic Services in 2023; UNDP Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2024; p. 66, file:///C:/Users/PC/Downloads/undp_ukraine_-_e-services-usage-omnibus-2023_-_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. E-Government Survey 2022: The Future of Digital Government; UN Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 30–42. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/reports/un-e-government-survey-2022.

- Matveieva, O.; Mamatova, T.; Borodin, Y.; Gustafsson, M.; Wihlborg, E.; Kvitka, S. Digital Government in Conditions of War: Governance Challenges and Revitalized Collaboration between Local Authorities and Civil Society in Provision of Public Services in Ukraine. Conference: Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lægreid, P.; Rykkja, L. Governance Capacity and Legitimacy Revisited: Governance Capacity and Legitimacy. In Societal Security and Crisis Management; 2019; pp. 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Policies for resilient local economies. Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED)., Papers 2022/09. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/09/policies-for-resilient-local-economies_d324a08c/872d431b-en.pdf.

- World Bank. Ukraine relief, recovery, reconstruction and reform trust fund. 2024 Annual report, World Bank Group 2024. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099430504172540289/pdf/IDU-27384831-502e-466d-907e-d497bdd5132d.pdf.

- Espinosa, V.; Pino, A. E-Government as a Development Strategy: The Case of Estonia. International Journal of Public Administration 2024, Volume 48(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukraine, UNDAP. Digitally inclusive recovery from COVID-19 pandemic in Ukraine, Kyiv 2022. p. pp.27. Available online: https://www.undp.org/ukraine/publications/digitally-inclusive-recovery-covid-19-pandemic-ukraine.

- European Commission. Digital Decade Policy Programme 2030; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 14 December 2022; pp. 5–10. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32022D2481.

- OECD. Policies for resilient local economies. Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED)., Papers 2022/09. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/09/policies-for-resilient-local-economies_d324a08c/872d431b-en.pdf.

- World Bank. Ukraine relief, recovery, reconstruction and reform trust fund. 2024 Annual report, World Bank Group 2024. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099430504172540289/pdf/IDU-27384831-502e-466d-907e-d497bdd5132d.pdf.

- UNDP Ukraine; Ministry of Digital Transformation of Ukraine. Analytical report. Opinions and views of the Population of Ukraine on State Electronic Services in 2023; UNDP Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2024; p. 66, file:///C:/Users/PC/Downloads/undp_ukraine_-_e-services-usage-omnibus-2023_-_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Digital Decade Policy Programme 2030; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 14 December 2022; pp. 5–10. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32022D2481.

- World Economic Forum. State of the Connected World 2023 Edition. In Insight Report; January 2023; p. pp.49. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_State_of_the_Connected_World_2023_Edition.pdf.

- International Telecommunication Union. Measuring Digital Development: Facts and Figures 2023. International Telecommunication Union 38. Available online: https://www.itu.int/itu-d/reports/statistics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2023/11/Measuring-digital-development-Facts-and-figures-2023-E.pdf.

- European Commission. Second Report on the application of the General Data Protection Regulation, 25.7.2024, COM(2024) 357 final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2024%3A357%3AFIN&qid=1721897017650.

- European Commission. Report on the state of the Digital Decade 2023; Brussels 2023, COM(2023) 570 final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX%3A52023DC0570&utm_.

- Tangi, L.; Janssen, M.; Benedetti, M.; Noci, G. Digital government transformation: A structural equation modelling analysis of driving and impeding factors. International Journal of Information Management 2021, Volume 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. E-Government Survey 2022: The Future of Digital Government; UN Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 30–42. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/reports/un-e-government-survey-2022.

- OECD. Public Governance Policy Papers. 2023 OECD Digital Government Index. Results and Key Findings, OECD 2023. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/01/2023-oecd-digital-government-index_b11e8e8e/1a89ed5e-en.pdf.

- UNDP. Digital Strategy 2022-2025, pp.52. Available online: https://digitalstrategy.undp.org/documents/Digital-Strategy-2022-2025-Full-Document_ENG_Interactive.pdf?_gl=1*f1iwa9*_ga*Njg0MjA4MDkwLjE3NjU0MDI5NzY.*_ga_3W7LPK0WP1*czE3NjU0NzI0MzMkbzMkZzAkdDE3NjU0NzI0NTYkajM3JGwwJGgw.

- World Bank. Ukraine relief, recovery, reconstruction and reform trust fund. 2024 Annual report, World Bank Group 2024. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099430504172540289/pdf/IDU-27384831-502e-466d-907e-d497bdd5132d.pdf.

- Deloitte. Government trends 2023, pp. 137. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/content/dam/assets-shared/legacy/docs/industry/government-public-services/2022/gx-government-trends-2023.pdf.

- Van der Voet, J.; Steijn, B.; Kuipers, B. Digital transformation in the public sector: A systematic review. Public Management Review 2021, 23(2), 227–248. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey; Company. The new digital edge: Rethinking strategy for the postpandemic era, May 26, 2021, pp.17. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/mckinsey%20digital/our%20insights/the%20new%20digital%20edge%20rethinking%20strategy%20for%20the%20postpandemic%20era/the-new-digital-edge-rethinking-strategy-for-the-postpandemic-era.pdf.

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs E-Government Survey 2022: The Future of Digital Government 311. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Digital Progress and Trends Report 2023. In International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; 2024; p. 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Digital Strategy 2022-2025, pp.52. Available online: https://digitalstrategy.undp.org/documents/Digital-Strategy-2022-2025-Full-Document_ENG_Interactive.pdf?_gl=1*f1iwa9*_ga*Njg0MjA4MDkwLjE3NjU0MDI5NzY.*_ga_3W7LPK0WP1*czE3NjU0NzI0MzMkbzMkZzAkdDE3NjU0NzI0NTYkajM3JGwwJGgw.

- OECD. Policies for resilient local economies. Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED)., Papers 2022/09. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/09/policies-for-resilient-local-economies_d324a08c/872d431b-en.pdf.

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2024/903 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 March 2024 on measures for a high level of public sector interoperability across the Union (Interoperable Europe Act). Official Journal of the European Union (OJ L 903) 2024, 22.3. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/interoperable-europe-act.html.

- World Economic Forum. State of the Connected World 2023 Edition. In Insight Report; January 2023; p. pp.49. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_State_of_the_Connected_World_2023_Edition.pdf.

- International Telecommunication Union. Measuring Digital Development: Facts and Figures 2023; ITU: Geneva, 2023; Available online: https://www.itu.int/itu-d/reports/statistics/facts-figures-2023/.

- UNDP. Digital Strategy 2022-2025, pp.52. Available online: https://digitalstrategy.undp.org/documents/Digital-Strategy-2022-2025-Full-Document_ENG_Interactive.pdf?_gl=1*f1iwa9*_ga*Njg0MjA4MDkwLjE3NjU0MDI5NzY.*_ga_3W7LPK0WP1*czE3NjU0NzI0MzMkbzMkZzAkdDE3NjU0NzI0NTYkajM3JGwwJGgw.

- World Bank. Ukraine relief, recovery, reconstruction and reform trust fund. 2024 Annual report, World Bank Group 2024. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099430504172540289/pdf/IDU-27384831-502e-466d-907e-d497bdd5132d.pdf.

- ENISA. The NIS2 directive: enhancing cyber security across the EU Forescout Mapping Guide, Forescout Technologies, Inc. 2024. Available online: https://www.forescout.com/resources/ebook_nis2-directive-enhancing-cyber-security-across-the-eu-forescout-mapping-guide/.

- OECD. Public Governance Policy Papers. 2023 OECD Digital Government Index. Results and Key Findings, OECD 2023. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/01/2023-oecd-digital-government-index_b11e8e8e/1a89ed5e-en.pdf.

- Bada, A.; Nurse, J.R.C. Developing cybersecurity education and awareness programmes for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Information and Computer Security 2019, Volume 27(Issue 3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włoch, R.; Śledziewska, K. Gospodarka cyfrowa. Jak nowe technologie zmieniają świat; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego: Warszawa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dudarski, Ł. Cyfryzacja administracji publicznej w Polsce: wyzwania i perspektywy. Zeszyty Naukowe Collegium Witelona 2024, nr 53(4), 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, V.; Pino, A. E-Government as a Development Strategy: The Case of Estonia. International Journal of Public Administration 2024, Volume 48(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Digital Strategy 2022-2025, pp.52. Available online: https://digitalstrategy.undp.org/documents/Digital-Strategy-2022-2025-Full-Document_ENG_Interactive.pdf?_gl=1*f1iwa9*_ga*Njg0MjA4MDkwLjE3NjU0MDI5NzY.*_ga_3W7LPK0WP1*czE3NjU0NzI0MzMkbzMkZzAkdDE3NjU0NzI0NTYkajM3JGwwJGgw.

- European Commission. Report on the state of the Digital Decade 2023; Brussels 2023, COM(2023) 570 final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX%3A52023DC0570&utm_.

- OECD. Public Governance Policy Papers. 2023 OECD Digital Government Index. Results and Key Findings, OECD 2023. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/01/2023-oecd-digital-government-index_b11e8e8e/1a89ed5e-en.pdf.

- ENISA. Threat Landscape 2023, European Union Agency for Cybersecurity, Athens, Greece. 2023. Available online: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/ENISA%20Threat%20Landscape%202023.pdf.

- Bada, A.; Nurse, J.R.C. Developing cybersecurity education and awareness programmes for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Information and Computer Security 2019, Volume 27(Issue 3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. E-Government Survey 2022: The Future of Digital Government; UN Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 30–42. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/reports/un-e-government-survey-2022.

- Mergel, I.; Edelman, N.; Haug, N. Defining Digital Transformation: Results from Expert Interviews. Government Information Quarterly 2019, vol. 36(no. 4), 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITU. Emergency Telecommunications Best Practices; International Telecommunication Union: Geneva, 2022; Available online: https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Emergency-Telecommunications/Pages/ET-OnlineToolkit/bestpractices.aspx.

- Comfort, LK; Boin, A.; Demchak, C.C. Designing Resilience: Preparing for Extreme Events; Pittsburgh University Press: Pittsburgh, 2010; ISBN 9780822960614. [Google Scholar]

- EBRD. Impact on the digital transition. Building foundations, enabling innovation, EBRD Impact Report 2024, 7. Available online: https://www.ebrd-impact-report-2024-impact-on-the-digital-transition.pdf.

- IFC. MSME Banking in the Digital Era. 2025, 168. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2025/msme-banking-in-the-digital-era.pdf.

- UNESCO. Global education monitoring report, 2023: technology in education: a tool on whose terms? In Global Education Monitoring Report Team; 2023; p. 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Report on the state of the Digital Decade 2023; Brussels 2023, COM(2023) 570 final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX%3A52023DC0570&utm_.

- OECD. Governing with Artificial Intelligence. The State of Play and Way Forward in Core Government Functions; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Report on the state of the Digital Decade 2023; Brussels 2023, COM(2023) 570 final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX%3A52023DC0570&utm_.

- ENISA. The NIS2 directive: enhancing cyber security across the EU Forescout Mapping Guide, Forescout Technologies, Inc. 2024. Available online: https://www.forescout.com/resources/ebook_nis2-directive-enhancing-cyber-security-across-the-eu-forescout-mapping-guide/.

- Is Informal Normal? Towards More and Better Jobs in Developing Countries; Jutting, J., de Laiglesia, J.R., Eds.; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009; p. 167. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2009/03/is-informal-normal_g1gha767/9789264059245-en.pdf.

- Brynjolfsson, E.; McAfee, A. The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies; W.W. Norton&Company: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 60–75. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research Design and Methods; SAGE Publications, 2018; ISBN 9781506336169. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Interpreting Qualitative Data; SAGE, 2011; pp. 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Government at a Glance 2023; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2023; p. 234. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2023/06/government-at-a-glance-2023_da193b0d/3d5c5d31-en.pdf.

- Kuusi, O.; Cuhls, K.; Steinmuller, K. The Futures Map and Its Quality Criteria. European Journal of Futures Research 2015, Volume 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Digital Decade Policy Programme 2030; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 14 December 2022; pp. 5–10. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32022D2481.

- Mergel, I.; Edelman, N.; Haug, N. Defining Digital Transformation: Results from Expert Interviews. Government Information Quarterly 2019, vol. 36(no. 4), 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2030 Digital Compass: The European Way for Digital Decade; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels 9.3.2021; COM(2021) 118 final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0118.

- Comfort, LK; Boin, A.; Demchak, C.C. Designing Resilience: Preparing for Extreme Events; Pittsburgh University Press: Pittsburgh, 2010; ISBN 9780822960614. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2024/903 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 March 2024 on measures for a high level of public sector interoperability across the Union (Interoperable Europe Act). Official Journal of the European Union (OJ L 903) 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/interoperable-europe-act.html.

| Dimension | Analytical focus | Illustrative indicators (conceptual) | Exemples from the Ukrainian case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technological | Capacity of digital infrastructure to ensure continuity under disruption | Platform availability, interoperability, cybersecurity, cloud backup | Diia platform, cloud-based data storage, Air Alert system |

| Institutional | Integration of digital tools into public administration and crisis management | Legal frameworks, inter-agency coordination, integration with emergency governance | Integration of Diia with social benefits, business support, and crisis response mechanisms |

| Societal(User) | Adoption and effective use of digital services by citizens and businesses | User penetration rate, service accessibility, inclusiveness | Over 20 million Diia users; widespread use of mobile administrative services during wartime |

| Year | Number of Diia platform users (million) | Number of services available on Diia | Number of notifications in Air Alert |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 9,5 | 72 | 0 |

| 2022 | 14,0 | 96 | 4500 |

| 2023 | 18,5 | 115 | 8200 |

| 2024 | 20,2 | 132 | 12000 |

| Country | Companies relocated by Diia.Business |

Microgrants under eRobota | Public tenders in Prozorro |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 210 | 2500 | 15000 |

| 2023 | 480 | 3800 | 18000 |

| 2024 | 750 | 4200 | 20500 |

| Country | Number of online services | Users (% of population) |

Integration with crisis management system |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ukraine | 132 | 60 | High |

| Estonia | 140 | 75 | Medium |

| Poland | 110 | 50 | Low |

| Denmark | 125 | 68 | Medium |

| Hypothesis | Scope | Results of own research | Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Digital services and administrative continuity | Confirmed | World Bank (2024); UNDAP (2024) |

| H2 | Integration of digital tools into public administration | Confirmed | OECD (2021); European Commision (2021) |

| H3 | WEF (2023); ITU (2023) | ||

| Adaptability in EU countries | Confirmed | ||

| Country | Priorities |

|---|---|

| Poland | Integration of mObywatel with crisis management systems; Digital education |

| Estonia | Data security; International partnerships |

| Danemark | |

| Service inclusiveness; Integration with warning systems | |

| Priority | Significance | Leading Countries |

|---|---|---|

| Service Integration Data Security |

High | Estonia, Poland |

| Very high | Denmark, Estonia | |

|

Digital Education |

||

| Medium | Poland | |

| International Partnerships | High | Estonia, Denmark |

| Priority | Significance | Leading Countries |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).