1. Introduction

1.1. Data Mining Challenges in Therapeutic Communication

The computational analysis of therapeutic communication poses substantial challenges for contemporary data mining systems. Unlike conventional text or speech classification tasks, therapeutic interactions are characterized by extreme multi-label structure, severe class imbalance, and heterogeneous multimodal signals that must be jointly modeled to capture clinically meaningful patterns [

1,

2]. In psychotherapy settings, individual utterances may simultaneously express multiple emotional or behavioral states, resulting in high-dimensional label spaces with long-tailed distributions that violate assumptions underlying standard supervised learning approaches [

3].

Class imbalance is particularly acute in this domain. While common affective states such as concern or neutrality occur frequently, clinically salient behaviors and emotions such as rupture markers, avoidance, or reflective listening appear sparsely, often at ratios exceeding 50:1 relative to dominant classes [

4,

5]. Naive optimization toward overall accuracy or micro-averaged metrics leads to systematic under-detection of these rare but pedagogically critical phenomena [

6]. Effective therapeutic communication analysis therefore requires data mining strategies that explicitly address imbalance through class-aware optimization and threshold calibration [

7,

8].

In addition, therapeutic communication is inherently multimodal, integrating lexical content, vocal prosody, pacing, and turn-taking dynamics [

9,

10]. Textual cues alone are often insufficient to distinguish between superficially similar utterances that differ in affective intent, while acoustic signals without semantic grounding can be ambiguous [

11,

12]. Integrating heterogeneous modalities introduces further challenges related to temporal alignment, modality-specific noise, and the need to learn cross-modal dependencies rather than simple feature concatenation [

13,

14]. These characteristics collectively place therapeutic communication at the intersection of several open problems in applied data mining.

Table 1 summarizes the datasets, annotation strategies, and data mining challenges addressed in this work.

1.2. From Patient Monitoring to Bidirectional Clinical Analysis Systems

Prior work in patient-focused emotion recognition has predominantly addressed unidirectional detection of client emotional states for monitoring and crisis intervention purposes [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Existing approaches have primarily focused on developing sophisticated multi-label classification models for recognizing client emotional states from counseling interactions, achieving strong technical performance on benchmark datasets [

19,

20,

21]. Prior studies and empirical evidence indicate that patient emotion recognition, while technically sophisticated and potentially valuable for monitoring applications, provides incomplete analytic utility for comprehensive interaction analysis [

22,

23].

Contemporary systems can identify when clients experience emotions such as anxiety and sadness, but this information alone does not indicate whether therapeutic responses were appropriate, whether expressed empathy was sufficient, whether vocal tone conveyed supportiveness, or whether the level of directiveness matched client needs [

24,

25]. Recognition of client emotional states represents only one component of therapeutic interaction. The subsequent phase involves assessing whether provider responses effectively address identified emotional states through coordinated verbal and nonverbal communication [

26,

27].

However, existing computational approaches rarely model provider behaviors alongside patient affect within a unified analytic framework, limiting their usefulness for interaction-level analysis and behavioral interpretation. The therapeutic alliance between clinician and client has emerged across decades of meta-analytic research as a primary predictor of positive treatment outcomes, independent of specific therapeutic modalities employed [

28,

29,

30]. Yet computational approaches to modeling therapist communicative behaviors remain critically underdeveloped, particularly for naturalistic clinical data reflecting the complexity and variability of real-world practice [

31,

32].

Bidirectional modeling that encompasses both patient emotional states and provider communicative behaviors addresses fundamental limitations in existing approaches. Modeling therapist affective and communicative behaviors requires capturing subtle, context-dependent patterns where the same verbal content can convey vastly different therapeutic meanings depending on prosodic delivery [

33,

34]. The statement indicating difficulty can be spoken with warm, empathic prosody characterized by reduced speech rate, softer volume, and falling intonation contours, conveying genuine therapeutic presence. Alternatively, identical verbal content delivered with flat, perfunctory prosody characterized by monotone pitch, constant rate, and lack of vocal affect conveys substantially different meaning that clients may perceive as dismissive or inattentive [

35].

1.3. Research Contributions

This work advances data mining techniques for extreme multi-label classification, class imbalance handling, and multimodal fusion through three primary contributions. First, we introduce frequency-stratified class weighting combined with dynamic per-class threshold optimization for multi-label classification under severe imbalance [

36,

37]. This approach achieves substantial improvement in macro-F1 score compared to baseline multi-label classification, maintaining strong performance on classes with limited training examples while preventing gradient collapse for minority classes.

Second, we establish an automated processing pipeline for analyzing real-world psychotherapy sessions that addresses the scarcity of naturalistic clinical data suitable for computational modeling [

38]. The pipeline incorporates speaker diarization [

39], automatic speech recognition [

40], temporal segmentation, automated annotation [

41], and quality filtering, processing hundreds of sessions into thousands of annotated communication segments. This reproducible methodology establishes viability of leveraging publicly available clinical content for research purposes while respecting privacy constraints.

Third, we develop a cross-modal attention architecture that learns content-dependent prosodic associations for behavior recognition in multimodal settings [

42,

43]. Implementing scaled dot-product attention between text and audio representations [

44], the architecture achieves macro-F1 of 0.91 on controlled human-annotated data, comparable to inter-rater reliability reported among trained human annotators in psychotherapy process research [

45,

46]. The architecture outperforms simple concatenation-based fusion substantially, demonstrating that explicit modeling of cross-modal interactions provides benefits for recognizing coordinated multimodal behaviors [

47]. On automatically annotated naturalistic data, the architecture achieves macro-F1 of 0.71, quantifying the performance gap between controlled and real-world annotation regimes.

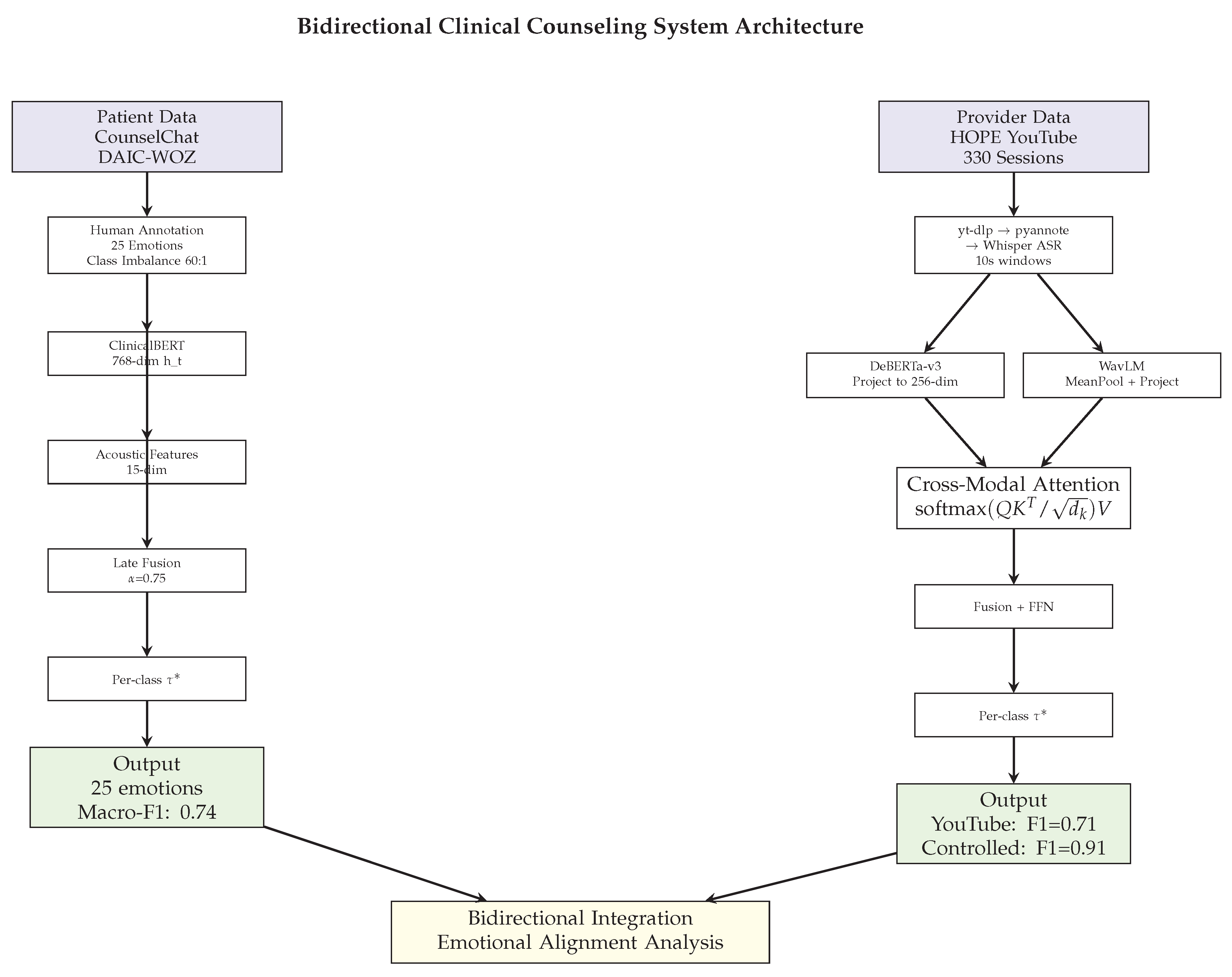

These contributions advance data mining methods for extreme multi-label learning under severe class imbalance, multimodal fusion with heterogeneous signal quality, and scalable analysis of complex interaction data in naturalistic settings. The complete bidirectional framework is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2. Materials and Methods

An overview of the complete system architecture and data processing pipelines is shown in

Figure 1.

2.1. Human Annotation Protocol

We established a three-stage annotation protocol for all datasets. Stage one involved schema development through collaborative discussion sessions with clinical annotators. Stage two performed full dataset annotation where each sample received independent review by multiple annotators. Stage three addressed schema refinement and consolidation based on label distributions and clinical validity.

For CounselChat, three licensed clinical psychologists with an average of eight years of clinical experience independently annotated 1,482 counseling interactions across 25 emotion categories. Initial inter-annotator agreement achieved Cohen’s kappa of 0.72. Final inter-rater reliability achieved Fleiss’ kappa of 0.78 on a validation subset of 200 interactions. For DAIC-WOZ, two clinical psychologists independently annotated approximately 8,400 utterances across 11 emotion categories, achieving Cohen’s kappa of 0.69. For controlled HOPE, a single licensed clinical psychologist with 12 years of experience annotated approximately 12,500 therapist utterances across 25 PQS dimensions, achieving Fleiss’ kappa of 0.76 on a validation subset of 1,000 utterances. Controlled human-labeled data anchors evaluation throughout this work.

2.2. Patient-Side: Multi-Label Classification with Imbalance Handling

The patient-side emotion recognition pipeline is shown on the left side of

Figure 1.

2.2.1. Problem Formulation

This design choice was motivated by the need to capture co-occurring emotional states. We formulate patient emotion recognition as multi-label classification where each interaction receives predictions for L emotion labels simultaneously. ClinicalBERT [

53] serves as the base encoder, producing 768-dimensional contextual embeddings from the [CLS] token. A linear classification head maps to L output dimensions with sigmoid activation enabling independent probabilistic estimates.

2.2.2. Frequency-Stratified Class Weighting

This design choice was motivated by the need to address severe class imbalance. We implement position-weighted binary cross-entropy loss:

where weights combine square root inverse frequency with stratified multipliers:

Multipliers equal 2.0 for extremely rare categories, 1.5 for moderately rare categories, and 1.0 for common categories.

2.2.3. Dynamic Threshold Optimization

For each label, we select thresholds maximizing validation F1:

2.2.4. Multimodal Extension

For DAIC-WOZ, we extracted acoustic features including fundamental frequency, mean energy, and thirteen mel-frequency cepstral coefficients using librosa [

55]. Late fusion combines independent text and audio classifiers at the decision level:

where

is optimized on validation data.

Table 2.

Patient-Side Model Configurations.

Table 2.

Patient-Side Model Configurations.

| Component |

CounselChat |

DAIC-WOZ Early |

DAIC-WOZ Late |

| Base encoder |

ClinicalBERT |

ClinicalBERT |

ClinicalBERT + MLP |

| Fusion |

N/A |

Concatenation |

Weighted averaging |

| Loss |

Weighted BCE |

Standard BCE |

Independent BCE |

| Optimizer |

AdamW, 1e-5 |

AdamW, 1e-5 |

Text: 1e-5; Audio: 1e-3 |

| Batch size |

8/16 |

8/16 |

Text: 8/16; Audio: 16/32 |

| Epochs |

5, patience=3 |

5 |

Text: 5; Audio: 20 |

| Fusion weight |

N/A |

N/A |

=0.75 |

2.3. Provider-Side: Cross-Modal Attention for Real-World Data

The provider-side processing and cross-modal architecture are shown on the right side of

Figure 1.

2.3.1. YouTube Data Processing Pipeline

This design choice was motivated by the scarcity of naturalistic clinical data. We process 330 YouTube psychotherapy sessions through an automated pipeline: (1) yt-dlp extracts audio as 16 kHz mono WAV, (2) pyannote.audio [

39] performs speaker diarization, (3) therapist-only audio is reconstructed, (4) Whisper-large-v3 [

40] generates timestamped transcripts, (5) temporal chunking creates 10-second windows with 2-second stride, (6) Claude Sonnet 4 [

41] annotates six communication styles (Neutral, Reflective, Empathetic, Supportive, Validating, Transitional), and (7) quality filtering removes ambiguous segments. Large language models are used only for annotation; all predictive models are trained independently on annotated data. The pipeline successfully processes 278 sessions yielding 14,086 annotated segments.

2.3.2. Controlled HOPE Dataset

Using the annotation protocol described above, we process 178 controlled HOPE sessions [

56] with session-level PQS ratings. We retrieved audio-video recordings, performed forced alignment for utterance segmentation, and obtained approximately 12,500 therapist utterances. A single psychologist annotated utterances across 25 PQS dimensions.

2.3.3. Cross-Modal Attention Architecture

This design choice was motivated by the need to model coordinated verbal-prosodic patterns. Text encoder DeBERTa-v3-base [

58] and audio encoder WavLM-base-plus [

43] project to shared 256-dimensional space. Cross-modal attention implements scaled dot-product attention [

44]:

Training employs multi-stage strategy: warmup (2 epochs), fine-tuning (10 epochs), and threshold optimization.

Table 3.

Provider-Side Model Configuration.

Table 3.

Provider-Side Model Configuration.

| Component |

Controlled HOPE |

YouTube HOPE |

| Text Encoder |

DeBERTa-v3-base (184M) |

DeBERTa-v3-base |

| Audio Encoder |

WavLM-base-plus (95M) |

WavLM-base-plus |

| Shared Dimension |

d=256, h=8 |

d=256, h=8 |

| Training |

Warmup 2 epochs; Fine-tune 10 epochs |

Single-stage 20 epochs |

| Batch Size |

8 (effective 32) |

8 |

| Output Classes |

25 PQS dimensions |

6 communication styles |

3. Results

3.1. Patient-Side Emotion Recognition Performance

As shown in

Table 4, the single-label formulation achieved micro-F1 of 0.30 and macro-F1 of 0.12. Multi-label formulation without class weights yielded micro-F1 of 0.13 and macro-F1 of 0.12. Incorporating class weighting improved performance to micro-F1 of 0.52 and macro-F1 of 0.53. The final model with dynamic thresholds achieved micro-F1 of 0.65, macro-F1 of 0.74, and subset accuracy of 0.34.

Ablation experiments isolated component contributions. Removing dynamic thresholds reduced performance by 0.13 points. Removing class weights reduced performance by 0.62 points. Reducing training epochs reduced performance by 0.09 points.

3.2. Provider-Side Behavior Recognition Performance

Table 5 presents provider-side model performance across architectures. On controlled HOPE data, cross-modal fusion achieved micro-F1 of 0.93, macro-F1 of 0.91, and Cohen’s kappa of 0.87, comparable to inter-rater reliability reported among trained human annotators in psychotherapy process research. On YouTube data, the architecture achieved micro-F1 of 0.86 and macro-F1 of 0.71.

Table 6 presents per-dimension performance on controlled HOPE data. Warmth and Supportiveness achieved F1 of 0.94, Empathy achieved 0.92, Silence and Listening achieved 0.91, Validation achieved 0.90, Reassurance achieved 0.86, Directiveness achieved 0.85, Interpretation achieved 0.80, and Challenge and Confrontation achieved 0.77.

Table 7 presents per-style performance on YouTube HOPE data. Neutral achieved F1 of 0.934 with 327 support examples. Transitional achieved 0.834 with 211 examples. Reflective achieved 0.833 with 137 examples. Empathetic achieved 0.600 with 12 examples. Supportive achieved 0.561 with 18 examples. Validating achieved 0.500 with 8 examples.

4. Discussion

4.1. Controlled Versus Real-World Data Quality

The 20 percentage point performance gap between controlled HOPE (macro-F1 0.91) and YouTube HOPE (macro-F1 0.71) reveals systematic differences in data quality regimes. These findings are consistent with the impact of annotation methodology, where expert human psychologist review provides higher label reliability than automated large language model annotation [

59]. Audio quality variation between controlled studio recordings and heterogeneous YouTube content introduces additional noise. Label complexity reduction from fine-grained expert taxonomies to coarser functional categories affects discriminative capacity. Segmentation methodology differs between utterance-level forced alignment providing natural linguistic boundaries and fixed temporal windows potentially fragmenting therapeutic statements.

These patterns suggest that automated annotation pipelines, while enabling large-scale data acquisition, introduce systematic performance degradation compared to expert human labeling. The magnitude of this degradation quantifies the cost of transitioning from controlled to naturalistic settings. For data mining applications prioritizing scale over precision, this trade-off may be acceptable. For applications requiring high reliability, hybrid approaches combining automated preprocessing with selective human review merit investigation [

38].

4.2. Class-Aware Optimization for Extreme Imbalance

The observed six-fold macro-F1 improvement demonstrates the effectiveness of frequency-stratified weighting combined with dynamic threshold optimization for multi-label classification under severe imbalance. These results suggest that two-component weighting schemes balancing gradient emphasis with training stability outperform single-component approaches. The square root transformation moderates extreme weight values while stratified multipliers provide targeted amplification for different rarity tiers [

4,

5].

Dynamic per-class threshold optimization contributes substantial additional gains. This pattern aligns with theoretical expectations that imbalanced multi-label tasks exhibit heterogeneous calibration characteristics across classes, making fixed threshold approaches suboptimal [

6,

7]. The observed threshold variation reflects different optimal operating points on class-specific precision-recall curves. For data mining practitioners addressing extreme imbalance, these findings suggest that threshold tuning should be considered standard practice rather than optional refinement.

Comparison with alternative approaches provides context. SMOTE oversampling [

36] creates synthetic minority samples but struggles with multi-label co-occurrence patterns where synthesizing realistic combinations of concurrent labels proves challenging. Focal loss [

53] emphasizes hard examples but does not explicitly address frequency imbalance. Standard class-balanced loss employs inverse frequency without stratification, potentially producing training instability. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that multi-component approaches combining frequency weighting, sublinear scaling, and threshold tuning provide more robust solutions for extreme multi-label imbalance.

4.3. Fusion Strategy Selection for Heterogeneous Modalities

The differential performance of fusion strategies across patient and provider tasks reveals task-dependent optimal architectures. For patient emotions, late fusion with learned weight alpha of 0.75 outperforms early fusion. This pattern aligns with scenarios where modalities contribute relatively independently and exhibit different noise characteristics [

47]. Text provides strong signal through clinical language patterns while audio exhibits substantial variability from recording quality issues. Late fusion allows text-dominant combination while preserving some complementary acoustic information.

For provider behaviors, cross-modal attention achieves substantial gains over both concatenation and late fusion. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that therapist communication involves coordinated multimodal patterns where verbal content and prosodic delivery interact to convey meaning [

33,

42]. The same verbal statement delivered with different prosodic characteristics expresses different therapeutic intentions. Cross-modal attention mechanisms enable learning which acoustic patterns are relevant for specific textual content rather than treating modalities as independent contributors [

9].

Attention weight visualization reveals interpretable patterns. For empathic statements, attention concentrates on prosodic features indicating vocal warmth including reduced speech rate, softer volume, and falling pitch contours. For directive interventions, attention shifts to features indicating confident guidance including steady speech rate and rising terminal pitch. These patterns align with communication theory regarding coordinated verbal and prosodic signaling of affective intent [

11,

12,

34]. For data mining applications, these findings suggest that fusion strategy should match the causal structure of modality interactions rather than applying uniform architectures across tasks.

4.4. Scalability and Deployment Considerations

The YouTube processing pipeline demonstrates practical viability for moderate-scale analysis. Diarization accuracy exceeded 92 percent on validation samples [

39]. Automatic speech recognition achieved word error rate of 11.3 percent [

40]. Processing requires approximately 15 minutes per 45-minute session. Training requires 8 to 12 hours on NVIDIA A100 GPUs. Inference latency remains under 2 seconds per segment. These computational characteristics enable batch processing of hundreds of sessions and real-time analysis of streaming interactions.

The 84 percent success rate for YouTube video retrieval and processing identifies technical bottlenecks. Failures result from hosting changes, access restrictions, and quality issues. For large-scale deployment, robust error handling and retry mechanisms would improve yield. Audio quality variation introduces performance degradation compared to controlled recordings. For applications requiring consistent reliability, quality assessment mechanisms could filter low-quality segments during preprocessing.

4.5. Methodological Perspective

From a methodological perspective, the proposed framework should be interpreted as a contribution to data mining for extreme multi-label learning and multimodal fusion under heterogeneous noise, rather than as a deployed clinical or evaluative system.

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

Automated annotation reliability limits YouTube model performance. These findings are consistent with systematic label noise introduced by large language model annotation compared to expert human review [

59]. Rare class performance suffers from limited training data. Support of 8 to 18 examples for certain communication styles provides insufficient learning signal [

61,

65]. Temporal context remains unexploited as utterance-level processing ignores conversational dynamics and session-level progression [

62,

66]. Cross-domain generalization requires validation as models trained on one therapeutic approach may not transfer to different modalities. Video modality exclusion represents missed opportunity as facial expressions convey substantial affective information [

63,

64].

Future research directions include semi-supervised learning combining automated annotation with selective expert review. Few-shot learning approaches could improve rare class generalization from limited examples. Session-level temporal modeling through recurrent or transformer architectures could capture therapeutic progression. Multimodal expansion incorporating visual features would provide comprehensive analysis. Cross-cultural validation would establish generalizability across diverse contexts.

5. Conclusions

We present a comprehensive bidirectional framework for clinical counseling analysis addressing patient emotion recognition and provider behavior assessment using real-world data. The framework advances multi-label classification, class imbalance handling, and multimodal fusion through three key contributions.

First, frequency-stratified class weighting with dynamic per-class threshold optimization achieves substantial macro-F1 improvement over baseline multi-label classification [

5,

7]. The approach maintains reasonable performance on classes with limited training examples while preventing gradient collapse for minority classes.

Second, an automated processing pipeline for YouTube psychotherapy sessions addresses the scarcity of naturalistic clinical data [

39,

40,

41]. The pipeline processes hundreds of sessions into thousands of annotated segments, establishing reproducible methodology for leveraging publicly available clinical content.

Third, cross-modal attention architecture learns content-dependent prosodic associations for multimodal behavior recognition [

42,

43,

58]. The architecture achieves macro-F1 of 0.91 on controlled human-annotated data, comparable to inter-rater reliability reported among trained human annotators. On YouTube data, the architecture achieves macro-F1 of 0.71, quantifying the performance gap between controlled and real-world annotation regimes.

The framework establishes viability of analyzing naturalistic therapy data from publicly available sources. Cross-modal attention mechanisms learn interpretable patterns. Automated annotation pipelines validated against human expert standards provide methodology for transitioning from controlled to real-world clinical data. Future work should focus on semi-supervised learning, temporal modeling, and longitudinal validation. These advances will enable comprehensive platforms supporting interaction-level analysis essential for computational study of therapeutic communication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M., X.L., P.Z. and A.B.; methodology, S.M., X.L., P.Z..; software, X.L., P.Z. R.S and V.J.; validation, S.M., X.L. and P.Z.; formal analysis, X.L. and S.M.; investigation, S.M., X.L., P.Z., S.F.M., R.S. and V.J.; resources, A.B.; data curation, S.M, P.Z., V.J. and R.S.;annotation, S.F.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M., X.L. and P.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.M., X.L., P.Z., S.F.M., and A.B.; visualization, S.M.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, S.M. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study uses publicly available de-identified datasets (CounselChat, DAIC-WOZ, and HOPE) and does not involve new human subjects research.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

CounselChat dataset is publicly available through online mental health platforms. DAIC-WOZ dataset is available through AVEC challenge (

https://dcapswoz.ict.usc.edu/). HOPE dataset URLs are publicly available through the Open Science Framework at

https://osf.io/6rv5m/. Annotation protocols available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the developers of CounselChat, DAIC-WOZ, and HOPE datasets. We acknowledge computational resources provided by Northeastern University Research Computing. During preparation, Claude Sonnet 4 was used for automated annotation of YouTube segments. The authors reviewed all outputs and take full responsibility for content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ASR |

Automatic Speech Recognition |

| BCE |

Binary Cross-Entropy |

| DSM-5 |

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition |

| FFN |

Feed-Forward Network |

| HOPE |

Healing Opportunities in Psychotherapy Expressions |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| MFCC |

Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficient |

| MLP |

Multilayer Perceptron |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| PQS |

Psychotherapy Process Q-Set |

| ReLU |

Rectified Linear Unit |

References

- Tsoumakas, G.; Katakis, I. Multi-label classification: An overview. Int. J. Data Warehous. Min. 2007, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.L.; Zhou, Z.H. A review on multi-label learning algorithms. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2014, 26, 1819–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japkowicz, N.; Stephen, S. The class imbalance problem: A systematic study. Intell. Data Anal. 2002, 6, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Garcia, E.A. Learning from Imbalanced Data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2009, 21, 1263–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charte, F.; Rivera, A.J.; del Jesus, M.J.; Herrera, F. Addressing imbalance in multilabel classification: Measures and random resampling algorithms. Neurocomputing 2015, 163, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Rehmsmeier, M. The precision-recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot when evaluating binary classifiers on imbalanced datasets. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, I.; Fumera, G.; Roli, F. Threshold optimisation for multi-label classifiers. Pattern Recognit. 2013, 46, 2055–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Jia, M.; Lin, T.Y.; Song, Y.; Belongie, S. Class-Balanced Loss Based on Effective Number of Samples. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 9268–9277. [Google Scholar]

- Baltrusaitis, T.; Ahuja, C.; Morency, L.P. Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 41, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, M.; Garcia, D.; Jou, B.; Schuller, B.; Chang, S.F.; Pantic, M. A survey of multimodal sentiment analysis. Image Vis. Comput. 2017, 65, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banse, R.; Scherer, K.R. Acoustic profiles in vocal emotion expression. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 614–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, K.R.; Johnstone, T.; Klasmeyer, G. Vocal expression of emotion. In Handbook of Affective Sciences; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 433–456. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, A.; Chen, M.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Morency, L.P. Tensor fusion network for multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Copenhagen, Denmark, 7–11 September 2017; pp. 1103–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Hazarika, D.; Majumder, N.; Zadeh, A.; Morency, L.P. Context-dependent sentiment analysis in user-generated videos. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 July–4 August 2017; Volume 1, pp. 873–883. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, R.A.; Milne, D.N.; Hussain, M.S.; Christensen, H. Natural language processing in mental health applications using non-clinical texts. Nat. Lang. Eng. 2017, 23, 649–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guntuku, S.C.; Yaden, D.B.; Kern, M.L.; Ungar, L.H.; Eichstaedt, J.C. Detecting depression and mental illness on social media: An integrative review. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2017, 18, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Choudhury, M.; Counts, S.; Horvitz, E. Social media as a measurement tool of depression in populations. In Proceedings of the 5th Annual ACM Web Science Conference, Paris, France, 2–4 May 2013; pp. 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, A.; Cohan, A.; Goharian, N. Depression and self-harm risk assessment in online forums. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Copenhagen, Denmark, 7–11 September 2017; pp. 2968–2978. [Google Scholar]

- Coppersmith, G.; Dredze, M.; Harman, C.; Hollingshead, K. From ADHD to SAD: Analyzing the Language of Mental Health on Twitter through Self-Reported Diagnoses. In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Clinical Psychology: From Linguistic Signal to Clinical Reality, Denver, CO, USA, 5 June 2015; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Resnik, P.; Armstrong, W.; Claudino, L.; Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, V.A.; Boyd-Graber, J. Beyond LDA: Exploring supervised topic modeling for depression-related language in Twitter. In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Clinical Psychology: From Linguistic Signal to Clinical Reality, Denver, CO, USA, 5 June 2015; pp. 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Losada, D.E.; Crestani, F.; Parapar, J. eRISK 2017: CLEF lab on early risk prediction on the Internet: Experimental foundations. International Conference of the Cross-Language Evaluation Forum for European Languages, Dublin, Ireland, 11–14 September 2017; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 346–360. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Schoene, A.M.; Ji, S.; Ananiadou, S. Natural language processing applied to mental illness detection: A narrative review. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, N.; Scherer, S.; Krajewski, J.; Schnieder, S.; Epps, J.; Quatieri, T.F. A review of depression and suicide risk assessment using speech analysis. Speech Commun. 2015, 71, 10–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.; Bohart, A.C.; Watson, J.C.; Murphy, D. Therapist empathy and client outcome: An updated meta-analysis. Psychotherapy 2018, 55, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norcross, J.C.; Lambert, M.J. Psychotherapy relationships that work III. Psychotherapy 2018, 55, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, L.S.; Elliott, R. Empathy. Psychotherapy 2019, 56, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.C. Reassessing Rogers’ necessary and sufficient conditions of change. Psychotherapy 2007, 44, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, A.O.; Del Re, A.C.; Flückiger, C.; Symonds, D. Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy 2011, 48, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, D.J.; Garske, J.P.; Davis, M.K. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flückiger, C.; Del Re, A.C.; Wampold, B.E.; Horvath, A.O. The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy 2018, 55, 316–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemotomos, N.; Martinez, V.R.; Chen, Z.; Singla, K.; Ardulov, V.; Peri, R.; Imel, Z.E.; Atkins, D.C.; Narayanan, S. Automated quality assessment of cognitive behavioral therapy sessions through highly contextualized language representations. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemotomos, N.; Martinez, V.R.; Gibson, J.; Atkins, D.C.; Creed, T.A.; Narayanan, S.S. Language features for automated evaluation of cognitive behavior psychotherapy sessions: A machine learning approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 702139. [Google Scholar]

- Juslin, P.N.; Scherer, K.R. Vocal expression of affect. In The New Handbook of Methods in Nonverbal Behavior Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 65–135. [Google Scholar]

- Cowie, R.; Cornelius, R.R. Describing the emotional states that are expressed in speech. Speech Commun. 2003, 40, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambady, N.; Rosenthal, R. Thin slices of expressive behavior as predictors of interpersonal consequences: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 111, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, K.; Eng, K.H.; Page, C.D. Area under the precision-recall curve: Point estimates and confidence intervals. Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Nancy, France, 15–19 September 2014; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 451–466. [Google Scholar]

- Imel, Z.E.; Atkins, D.C.; Caperton, D.D.; Takano, K.; Iijima, Y.; Walker, D.D.; Steyvers, M. Mental Health Counseling From Conversational Content With Transformer-Based Machine Learning. JAMA Network Open 2024, 7, e2351075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredin, H.; Laurent, A. End-to-End Speaker Segmentation for Overlap-Aware Resegmentation. Proceedings of Interspeech 2021, Brno, Czech Republic, 30 August–3 September 2021; pp. 3111–3115. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Xu, T.; Brockman, G.; McLeavey, C.; Sutskever, I. Robust Speech Recognition via Large-Scale Weak Supervision. Proceedings of ICML 2023, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Anthropic. Claude 3 Model Family: Introducing the Next Generation of AI Assistants. Technical Report, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Y.H.; Bai, S.; Liang, P.P.; Kolter, J.Z.; Morency, L.P.; Salakhutdinov, R. Multimodal Transformer for Unaligned Multimodal Language Sequences. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 6558–6569. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Wang, C.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Kanda, N.; Yoshioka, T.; Xiao, X.; et al. WavLM: Large-Scale Self-Supervised Pre-Training for Full Stack Speech Processing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2022, 16, 1505–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All You Need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.E. Therapeutic Action: A Guide to Psychoanalytic Therapy; Jason Aronson: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ablon, J.S.; Jones, E.E. How expert clinicians’ prototypes of an ideal treatment correlate with outcome in psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Psychother. Res. 1998, 8, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadzicki, K.; Khamsehashari, R.; Zetzsche, C. Early vs Late Fusion in Multimodal Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Rustenburg, South Africa, 6–9 July 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Chiu, W.T.; Demler, O.; Walters, E.E. Prevalence, Severity, and Comorbidity of 12-Month DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A.; Campbell, L.A.; Lehman, C.L.; Grisham, J.R.; Mancill, R.B. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2001, 110, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineka, S.; Watson, D.; Clark, L.A. Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1998, 49, 377–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, F.; van Oppen, P.; Comijs, H.C.; Smit, J.H.; Spinhoven, P.; van Balkom, A.J.; Nolen, W.A.; Zitman, F.G.; Beekman, A.T.; Penninx, B.W. Comorbidity patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large cohort study: The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). J. Clin. Psychiatry 2011, 72, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratch, J.; Artstein, R.; Lucas, G.; Stratou, G.; Scherer, S.; Nazarian, A.; Wood, R.; Boberg, J.; DeVault, D.; Marsella, S.; et al. The Distress Analysis Interview Corpus of human and computer interviews. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC), Reykjavik, Iceland, 26–31 May 2014; pp. 3123–3128. [Google Scholar]

- Alsentzer, E.; Murphy, J.; Boag, W.; Weng, W.H.; Jin, D.; Naumann, T.; McDermott, M. Publicly Available Clinical BERT Embeddings. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.03323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Lalotra, G.S.; Sasikala, P.; Rajput, D.S.; Kaluri, R.; Lakshmanna, K.; Shorfuzzaman, M.; Alsufyani, A.; Uddin, M. Addressing Binary Classification over Class Imbalanced Clinical Datasets Using Computationally Intelligent Techniques. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFee, B.; Raffel, C.; Liang, D.; Ellis, D.P.; McVicar, M.; Battenberg, E.; Nieto, O. librosa: Audio and music signal analysis in python. In Proceedings of the 14th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 6–12 July 2015; pp. 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, S.B.; Flemotomos, N.; Martinez, V.R.; Tanana, M.J.; Kuo, P.B.; Pace, B.T.; Villatte, J.L.; Georgiou, P.G.; Van Epps, J.; Imel, Z.E.; et al. Machine learning and natural language processing in psychotherapy research: Alliance as example use case. J. Couns. Psychol. 2020, 67, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.E.; Pulos, S.M. Comparing the process in psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral therapies. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1993, 61, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, P.; Gao, J.; Chen, W. DeBERTaV3: Improving DeBERTa using ELECTRA-Style Pre-Training with Gradient-Disentangled Embedding Sharing. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.09543. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, A.A.; Hanafy, R.J.; Fouda, M.E. Automated Multi-Label Annotation for Mental Health Illnesses Using Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.03796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuller, B.; Batliner, A.; Steidl, S.; Seppi, D. Recognising realistic emotions and affect in speech: State of the art and lessons learnt from the first challenge. Speech Commun. 2011, 53, 1062–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, A.; Mitchell, M.; Hovy, D. Multitask learning for mental health conditions with limited social media data. In Proceedings of the 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Valencia, Spain, 3–7 April 2017; Volume 1, pp. 152–162. [Google Scholar]

- Majumder, N.; Poria, S.; Hazarika, D.; Mihalcea, R.; Gelbukh, A.; Cambria, E. DialogueRNN: An attentive RNN for emotion detection in conversations. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; Volume 33, pp. 6818–6825. [Google Scholar]

- Busso, C.; Bulut, M.; Lee, C.C.; Kazemzadeh, A.; Mower, E.; Kim, S.; Chang, J.N.; Lee, S.; Narayanan, S.S. IEMOCAP: Interactive emotional dyadic motion capture database. Lang. Resour. Eval. 2008, 42, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valstar, M.; Schuller, B.; Smith, K.; Almaev, T.; Eyben, F.; Krajewski, J.; Cowie, R.; Pantic, M. AVEC 2014: 3D dimensional affect and depression recognition challenge. In Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge, Orlando, FL, USA, 7 November 2014; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, A.K.; Jayasumana, S.; Rawat, A.S.; Jain, H.; Veit, A.; Kumar, S. Long-tail learning via logit adjustment. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Virtual Event, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Poria, S.; Hazarika, D.; Majumder, N.; Naik, G.; Cambria, E.; Mihalcea, R. MELD: A multimodal multi-party dataset for emotion recognition in conversations. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 527–536. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. Proceedings of NAACL-HLT, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.H.; Rudzicz, F. Detecting Anxiety through Reddit. In Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Clinical Psychology—From Linguistic Signal to Clinical Reality, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 3 August 2017; pp. 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gaur, M.; Alambo, A.; Sain, J.P.; Kursuncu, U.; Thirunarayan, K.; Kavuluru, R.; Sheth, A.; Welton, R.; Pathak, J. Knowledge-aware assessment of severity of suicide risk for early intervention. The World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; pp. 514–525. [Google Scholar]

- Wampold, B.E.; Imel, Z.E. The Great Psychotherapy Debate: The Evidence for What Makes Psychotherapy Work, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, P.G.; Parsons, T.D.; Gratch, J.; Leuski, A.; Rizzo, A.A. Virtual patients for clinical therapist skills training. International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 20–22 September 2007; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, A.; Scherer, S.; DeVault, D.; Gratch, J.; Artstein, R.; Hartholt, A.; Lucas, G.M.; Dyck, M.; Stratou, G.; Morency, L.P.; et al. Detection and computational analysis of psychological signals using a virtual human interviewing agent. J. Pain Manag. 2016, 9, 311–321. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, R.A.; Crane, C.; Miller, E.; Kuyken, W. Doing no harm in mindfulness-based programs: Conceptual issues and empirical findings. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 71, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, J.C.; Ribeiro, J.D.; Fox, K.R.; Bentley, K.H.; Kleiman, E.M.; Huang, X.; Musacchio, K.M.; Jaroszewski, A.C.; Chang, B.P.; Nock, M.K. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 187–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nock, M.K.; Borges, G.; Bromet, E.J.; Cha, C.B.; Kessler, R.C.; Lee, S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol. Rev. 2008, 30, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kring, A.M.; Bachorowski, J.A. Emotions and psychopathology. Cogn. Emot. 1999, 13, 575–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; Muñoz, R.F. Emotion regulation and mental health. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 1995, 2, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, D.M.; Bentley, K.H.; Ghosh, S.S. Automated assessment of psychiatric disorders using speech: A systematic review. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2020, 5, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.; Weber, L.; Neves, M.; Wiegandt, D.L.; Leser, U. Deep learning with word embeddings improves biomedical named entity recognition. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, i37–i48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.E.; Pollard, T.J.; Shen, L.; Li-wei, H.L.; Feng, M.; Ghassemi, M.; Moody, B.; Szolovits, P.; Celi, L.A.; Mark, R.G. MIMIC-III, a freely accessible critical care database. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ayadi, M.; Kamel, M.S.; Karray, F. Survey on speech emotion recognition: Features, classification schemes, and databases. Pattern Recognit. 2011, 44, 572–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatieri, T.F.; Malyska, N. Vocal-tract modeling of continuous-time Gaussian-excitation representation of voiced speech. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, Hong Kong, China, 6–10 April 2003; Volume 1, pp. I–732. [Google Scholar]

- Orlinsky, D.E.; Rønnestad, M.H. How psychotherapists develop: A study of therapeutic work and professional growth; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson, K.A. Deliberate practice and acquisition of expert performance: A general overview. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2008, 15, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, C.E., Jr. Handbook of Psychotherapy Supervision; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, J.M.; Goodyear, R.K. Fundamentals of Clinical Supervision, 5th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Falender, C.A.; Shafranske, E.P. Clinical Supervision: A Competency-Based Approach; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pepino, L.; Riera, P.; Ferrer, L. Emotion Recognition from Speech Using wav2vec 2.0 Embeddings. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.03502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, H.; Briand, A.; Meurs, M.J. Multimodal depression detection: A comparative study of machine learning models and feature fusion techniques. J. Biomed. Inform. 2024, 149, 104565. [Google Scholar]

- Al Hanai, T.; Ghassemi, M.; Glass, J. Detecting Depression with Audio/Text Sequence Modeling of Interviews. Proceedings of Interspeech 2018, Hyderabad, India, 2–6 September 2018; pp. 1716–1720. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Lin, I.W.; Miner, A.S.; Atkins, D.C.; Althoff, T. Towards Facilitating Empathic Conversations in Online Mental Health Support: A Reinforcement Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 194–205. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Rosas, V.; Mihalcea, R.; Resnicow, K.; Singh, S.; An, L. Understanding and Predicting Empathic Behavior in Counseling Therapy. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 July–4 August 2017; pp. 1426–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Nonverbal leakage and clues to deception. Psychiatry 1969, 32, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safran, J.D.; Muran, J.C.; Eubanks-Carter, C. Repairing alliance ruptures. Psychotherapy 2011, 48, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rønnestad, M.H.; Skovholt, T.M. The journey of the counselor and therapist: Research findings and perspectives on professional development. J. Career Dev. 2003, 30, 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.E.; Knox, S. Training and supervision in psychotherapy. In Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 6th ed.; Lambert, M.J., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 775–811. [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph, P.; Baranackie, K.; Kurcias, J.S.; Beck, A.T.; Carroll, K.; Perry, K.; Luborsky, L.; McLellan, A.T.; Woody, G.E.; Thompson, L.; et al. Meta-analysis of therapist effects in psychotherapy outcome studies. Psychother. Res. 1991, 1, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).