Submitted:

05 December 2024

Posted:

06 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

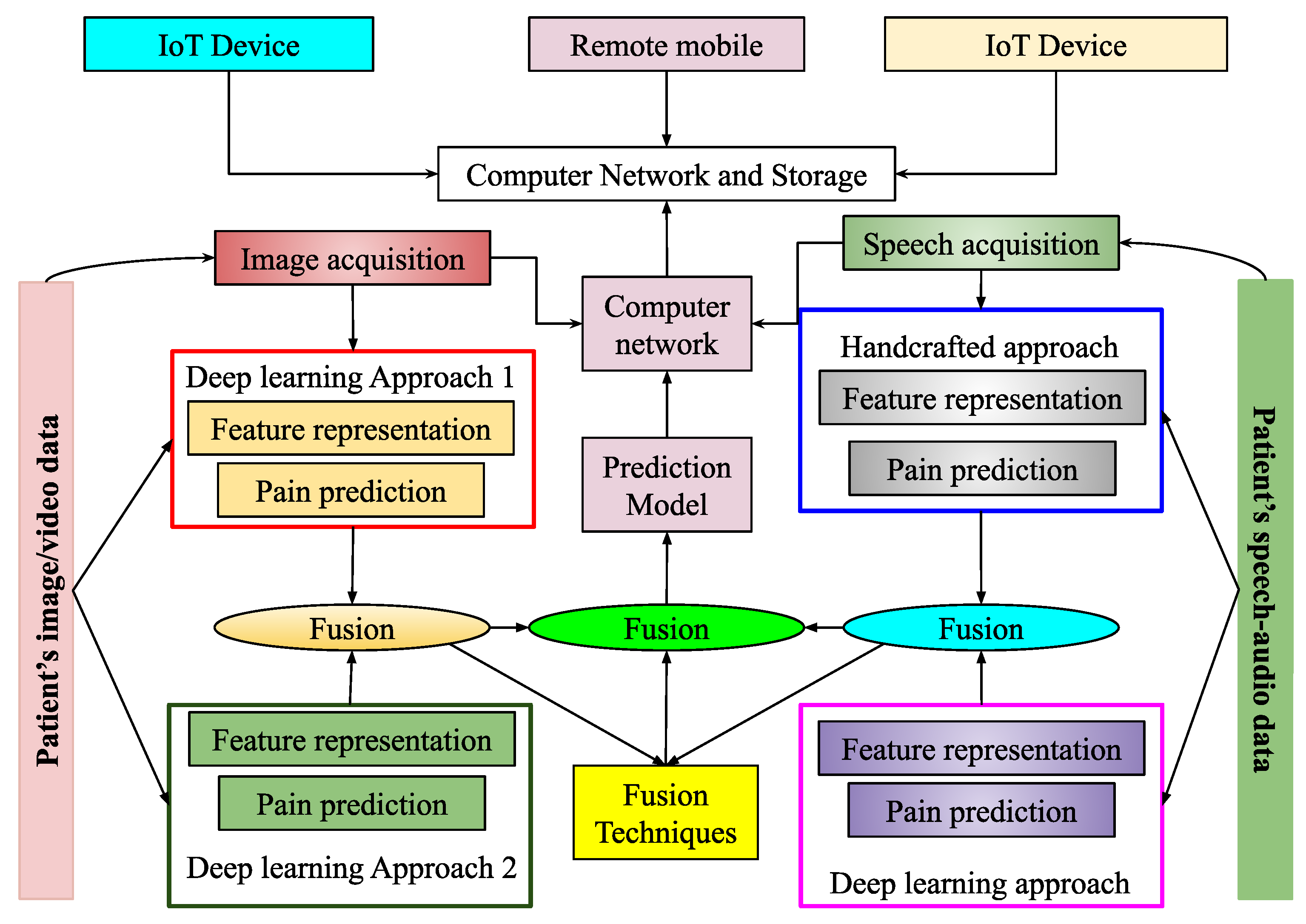

1. Introduction

- Deep learning-based frameworks utilizing handcrafted features are employed in the proposed audio-based pain sentiment analysis system.

- Several top-down deep learning frameworks are developed using Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architectures to extract discriminative features from facial regions for improved feature representation.

- Performance enhancements are achieved through various experiments, including batch vs. epoch comparisons, data augmentation, progressive image resizing, hyperparameter tuning, and transfer learning with pre-trained deep models.

- Post-classification fusion techniques are applied to improve system accuracy. Classification scores from different deep learning models are combined to reduce susceptibility to challenges such as variations in age, pose, lighting conditions, and noisy artifacts.

- The proposed system’s applications can be extended to detect mental health conditions such as stress, anxiety, and depression, contributing to treatment assessment within a smart healthcare framework.

- Finally, a multimodal pain sentiment analysis system is constructed by fusing classification scores from both image-based and audio-based sentiment analysis systems.

2. Related Work

3. Proposed Methodology

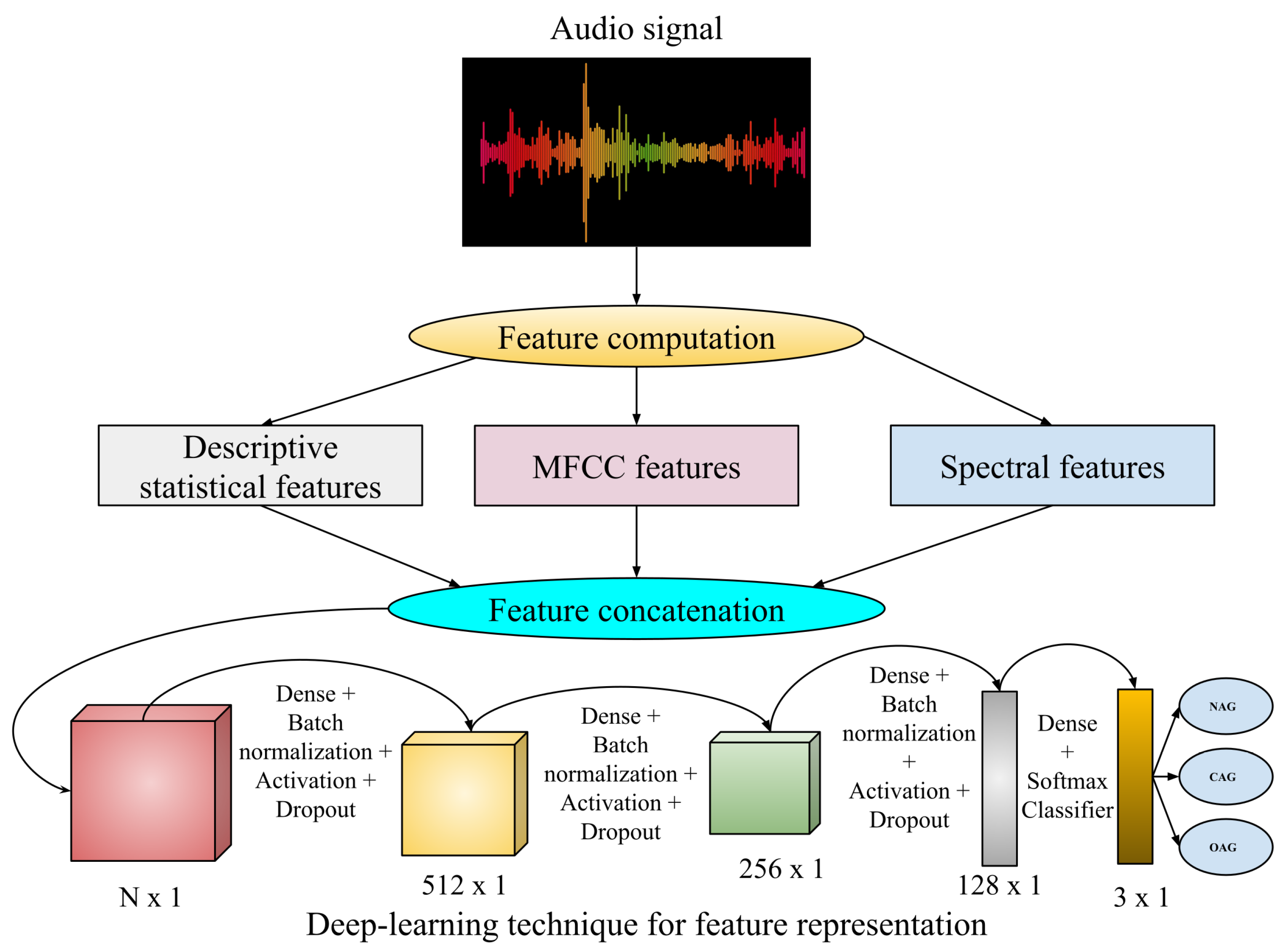

3.1. Audio-Based PSAS

- Statistical audio features: Here, the audio signal initially undergoes a frequency domain signal analysis using fast Fourier transformation (FFT) [52]. Then, the computed frequencies are used to calculate descriptive statistics such as mean, median, standard deviations, quartiles, and kurtosis. Further, the magnitude of derived frequency components is used to compute Energy, and the amplitude is used to calculate Root Mean Square Energy.

- Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC): This is a well-known audio-based feature computation technique [53] where the derived frequency components from FFT undergo to compute the logarithm of the amplitude spectrum. Then, the Mel scale is introduced to the logarithm of the amplitude spectrum, discrete cosine transformations (DCT) are applied on the Mel scale, and finally, 2-13 DCT coefficients are kept. The rest are discarded during feature computations.

- Spectral Features: Various spectral features like spectral contrast, spectral centroid, and spectral bandwidth are analyzed from the audio files. These spectral features [54] are related to the spectrogram of that audio files. The spectrogram represents the frequency intensities over time. It is measured from the squared magnitude of the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) [55], which is obtained by computing FFT over successive signal frames.

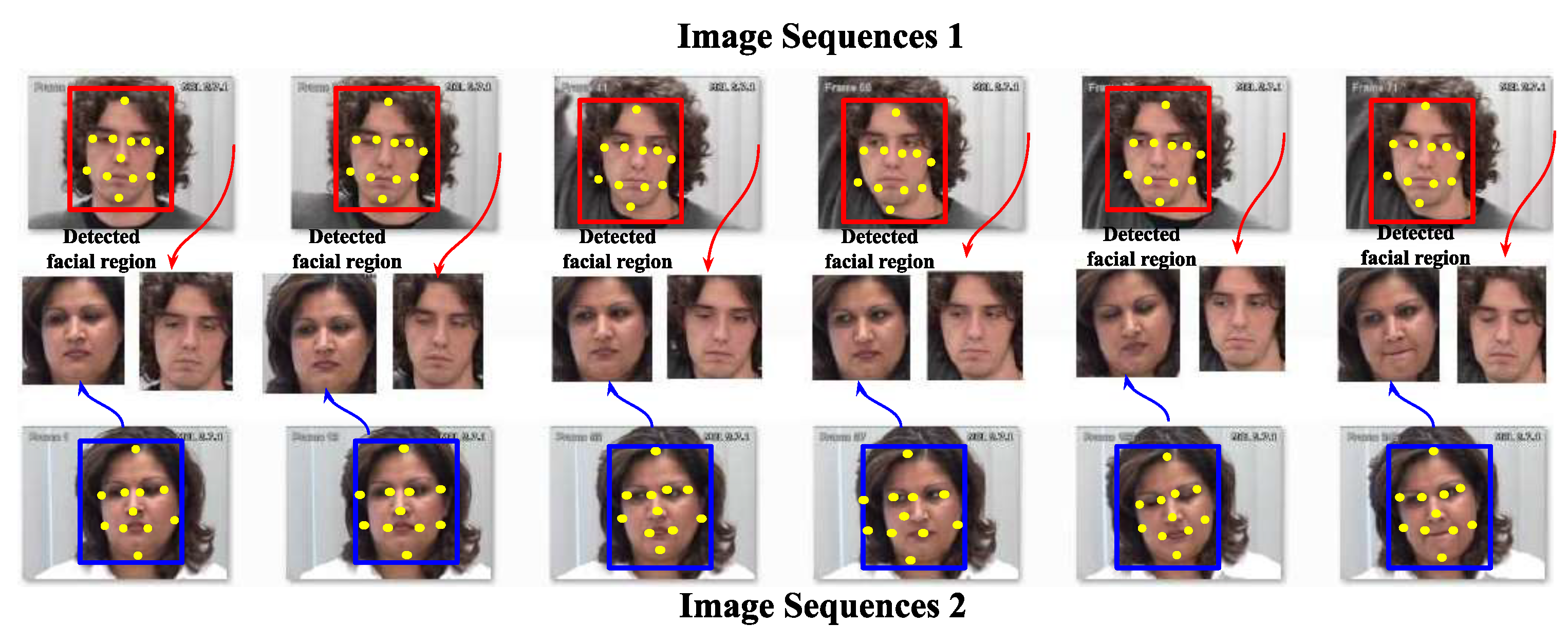

3.2. Image-Based PSAS

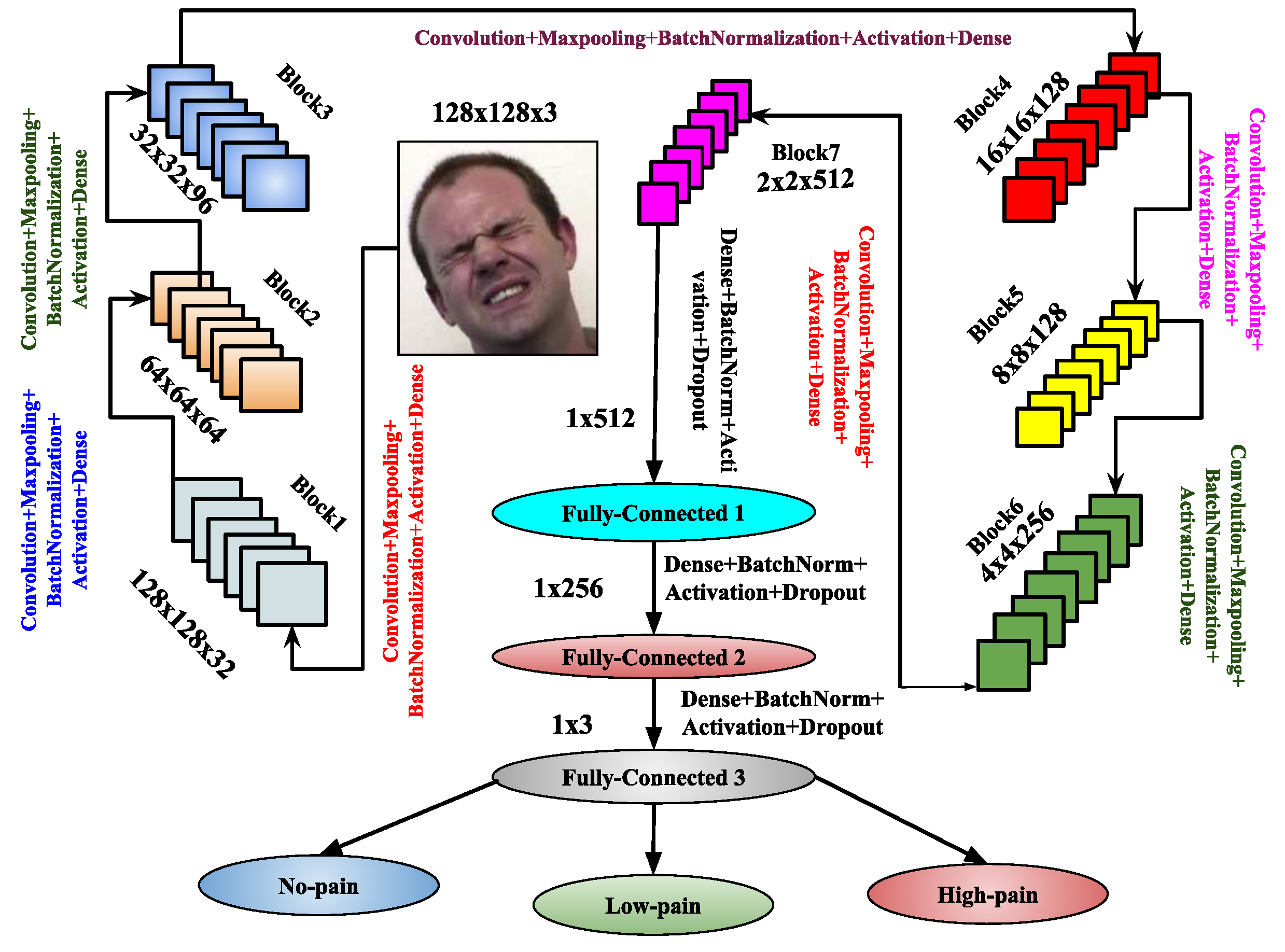

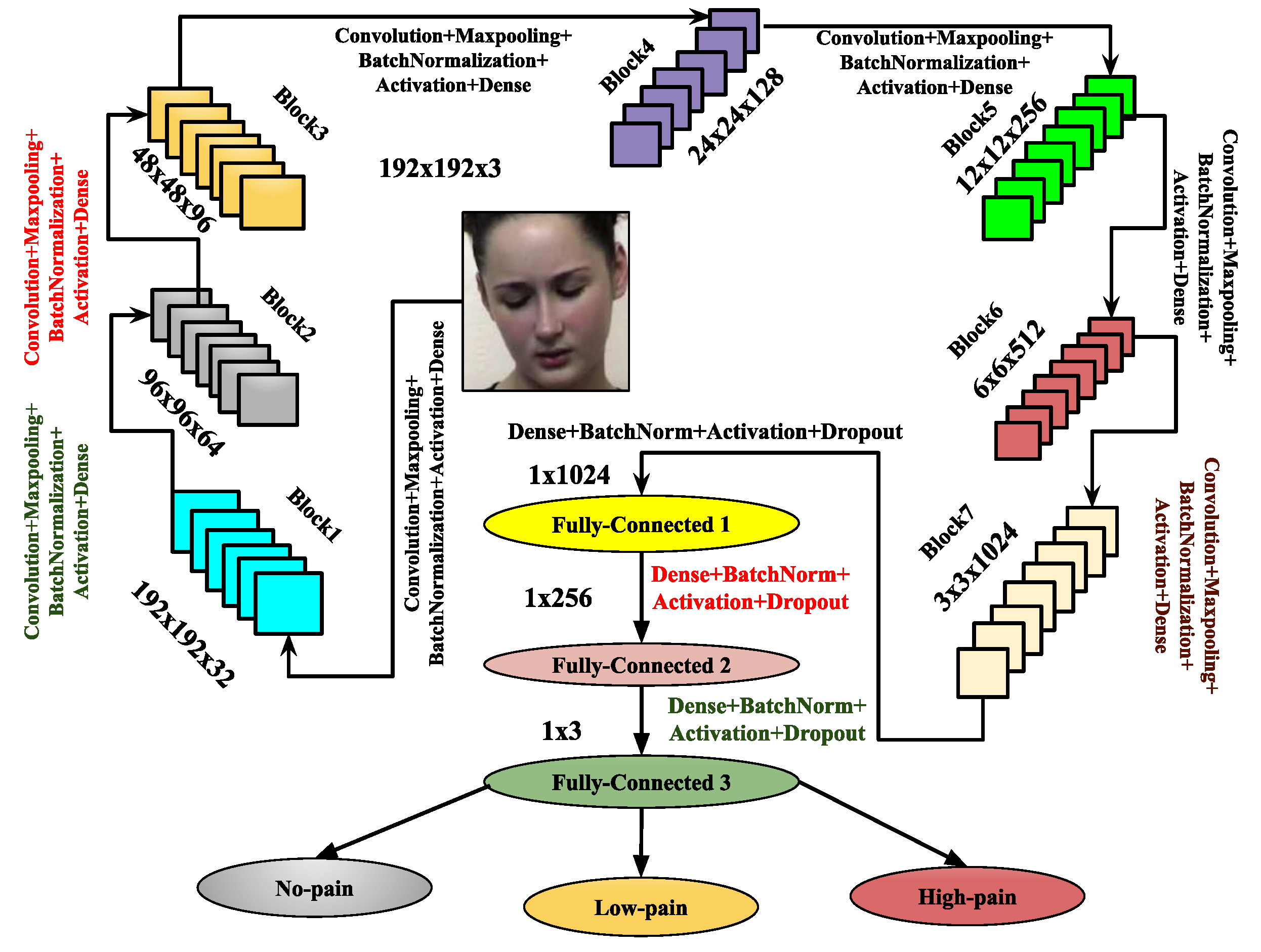

3.3. Image-Based Feature Representation Using Proposed Deep Learning Architectures

- Convolutional Layer: The convolutional layer generates feature maps Z by applying a kernel or mask of size to perform a convolution operation on the input image I. During this process, the kernel slides across the input image F, associating each region of the image with a non-linear activation function. At each location, element-wise matrix multiplication is performed, and the resulting data is summed to form an element in the feature map corresponding to the central region of the mask pattern. The convolutional layers with N (e.g., 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, etc.) are implemented as , where M denotes the number of convolutional layers in the CNN architecture, with , represents the weights of the M-th convolutional layer, * indicates the convolution operation, and corresponds to the biases of the M-th convolutional layer.

- Max-Pooling Layer: The max-pooling operation contributes to fine-tuning the parameters of the proposed CNN architecture, enhancing its performance. This operation involves calculating the maximum values within segments of the feature map, followed by the creation of down-sampled feature maps. Max-pooling offers several advantages, including uniform translation, reduced computational overhead, and improved selection of discriminative features from the input image I. If represents the output feature map from the input image F, the max-pooling operation is applied as .

- Batch Normalization Layer: Batch normalization acts as a controller, enabling the model to utilize higher learning rates, which are beneficial for performing image classification tasks [60]. Specifically, it stabilizes gradients across the network by mitigating the effects of parameter scales or initial values.

- Dropout Layer: In architectures, the dropout layer serves as a regularization technique to prevent overfitting. It compels the network to develop more robust and generalized features during training by randomly deactivating a subset of neurons. By reducing the dependency between neurons, the dropout layer enhances model performance and generalization on unseen inputs, leading to more efficient and reliable architectures.

- Flatten Layer: In , the flatten layer acts as a bridge between the convolutional and fully connected layers. It transforms the multi-dimensional feature maps into a one-dimensional vector, making them compatible with the subsequent fully connected layers. By converting complex spatial data into a linear format, the flatten layer enables the network to capture higher-level patterns and relationships, which are essential for tasks such as classification and decision-making.

- Fully Connected Layer: In every architecture, the fully connected layers are essential for performing classification. They transform the complete feature maps into isolated vectors, which are then used to generate class scores. This classification process produces a final vector whose size is determined by the number of class labels. The weight values in the dense layer help establish the connection between the input and output layers. The input to this layer is the output of the flatten layer, denoted by F, and the output of the R-th fully connected layer is represented by . The fully connected layer also incorporates the dropout layer for regularization.

- Output Layer: The output layer is responsible for classification, and the Softmax activation function is employed for this purpose. It utilizes the fully connected layer once more. The final output of this layer is denoted by Y, and its input, which comes from the fully connected layer, is represented by . The output is given by the equation , where are the weights, and are the biases associated with this layer.

- (i) The Sum-of-score is defined as ,

- (ii) The Product-of-score is defined as ,

- (iii) The Weighted-sum-of-score is defined as ,

4. Experiments

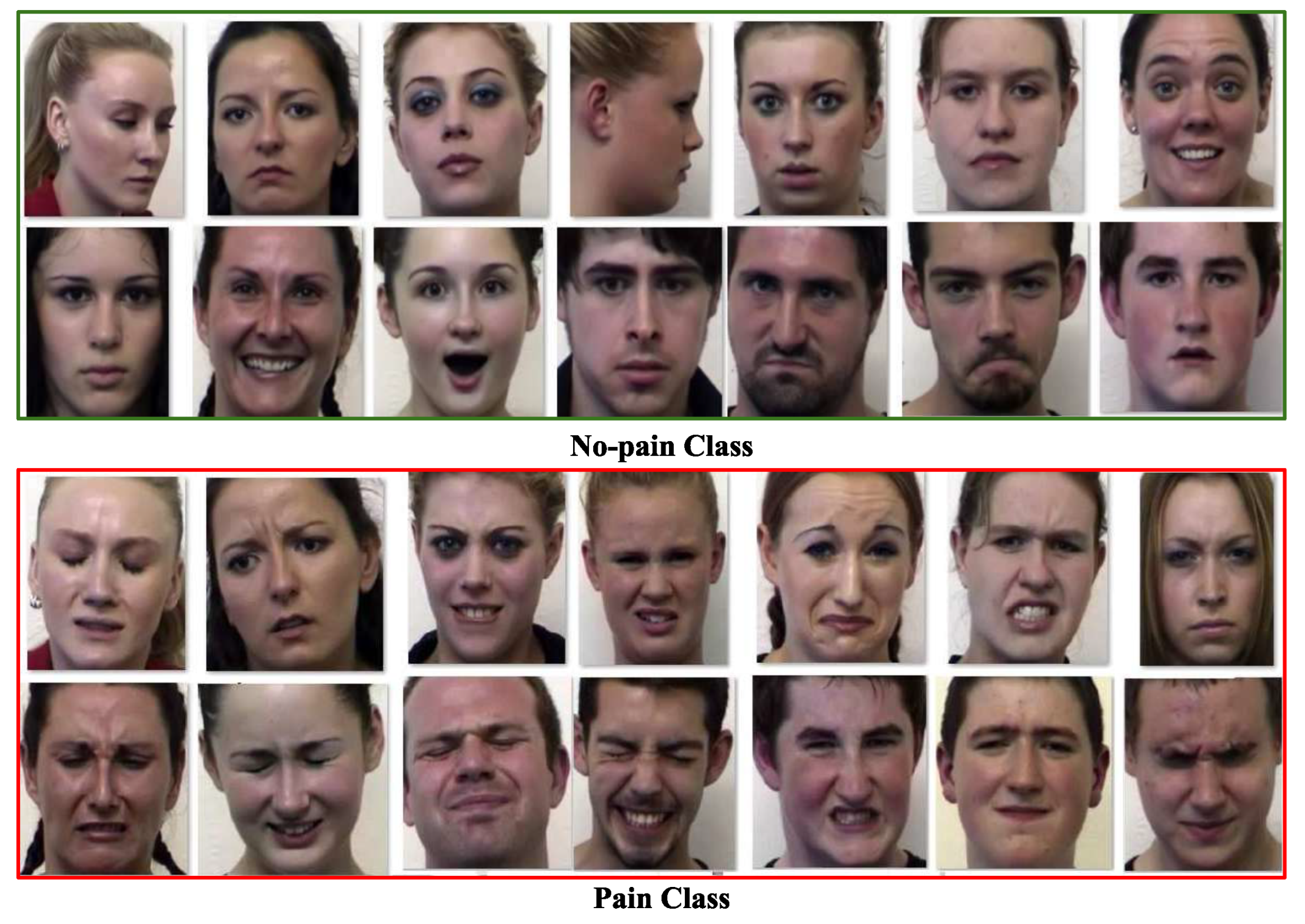

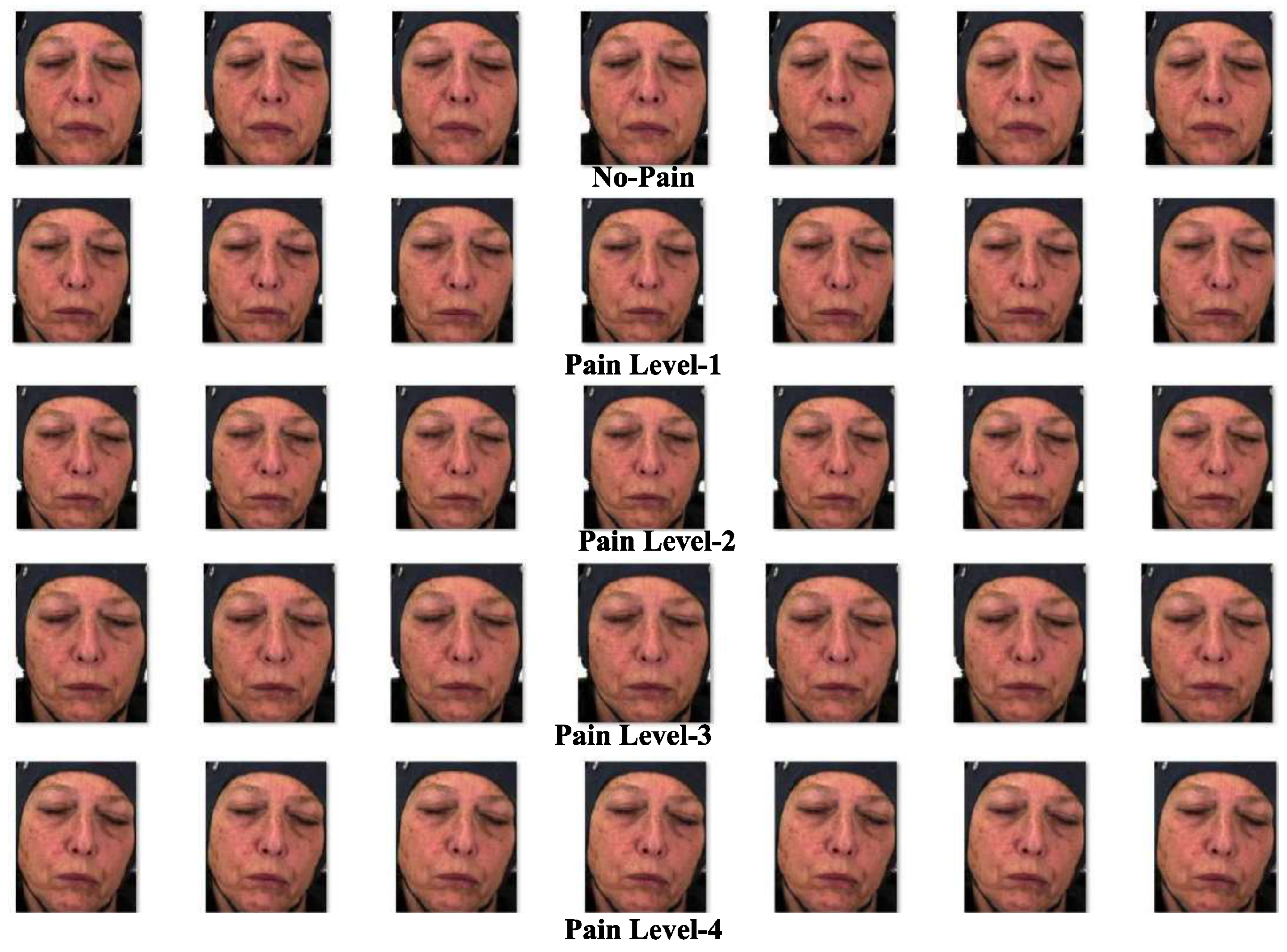

4.1. Databases Used

4.2. Results for Image-Based PSAS

-

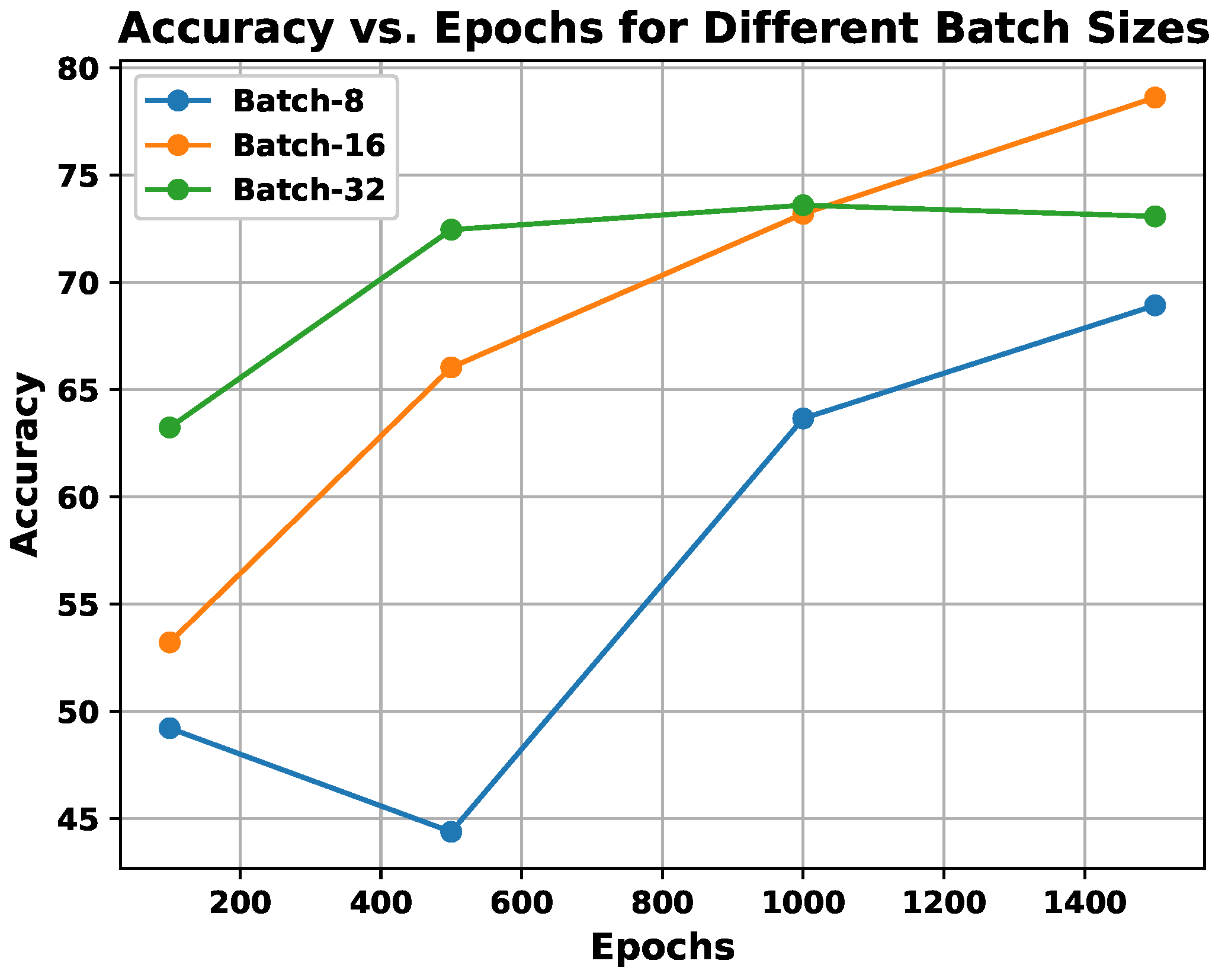

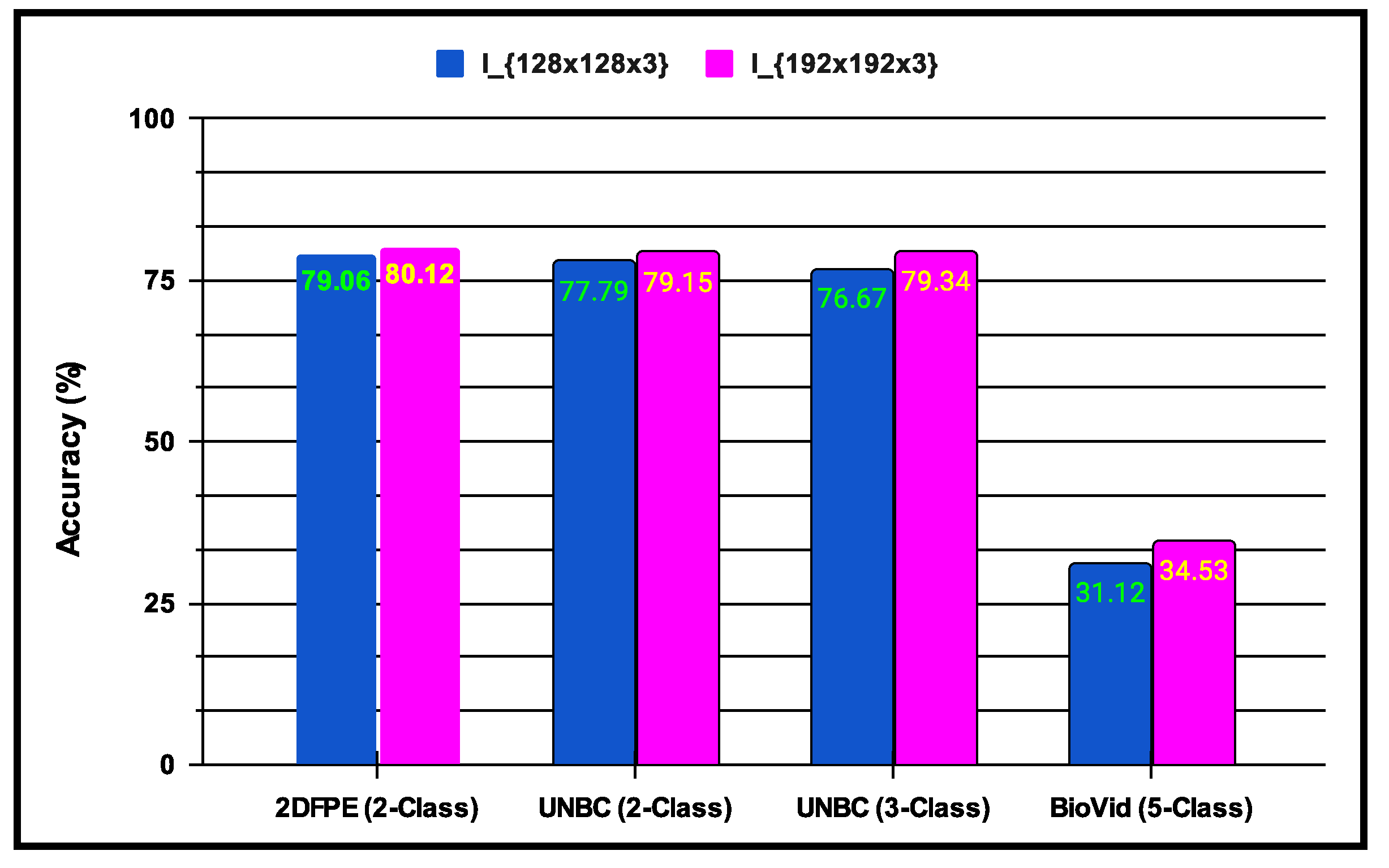

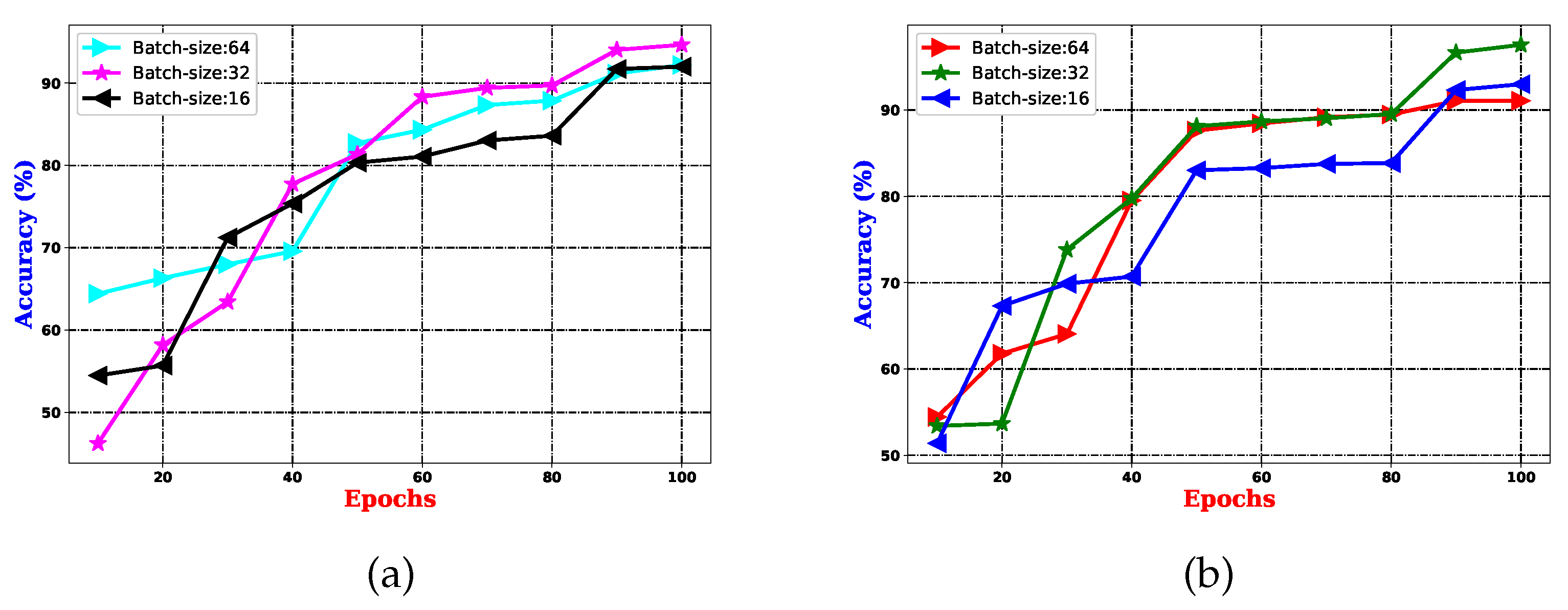

experiments: This experiment is associated with parameter learning, which builds on batches and epochs and is fundamental to every CNN architecture. Both batch vs. epoch factors impact the architecture’s learning capacity when samples are trained inside the network. In any deep CNN model, one of the most critical tasks is to learn the weight parameters. As a result, this work has established a trade-off between 16 batches and 1500 epochs, enhancing the proposed pain sentiment analysis system’s (PSAS) performance. An experiment comparing batch and epoch for the proposed system is displayed in Figure 9 using the UNBC 2-class dataset, and it can be seen from Figure 9 that performance improves with batch size 16 and epoch variations ranging from 1000 to 1500.Here, in the , experiments are also performed to introduce multi-resolution facial images by utilizing progressive image resizing. The introduction of this scheme needs the use of multi-resolution image analysis in order to benefit from progressive image scaling, such that the image of two different sizes are trained via the and architectures. In comparison to the architecture performance, the offers the following benefits: (i) networks can be trained with images ranging from low to high resolution; (ii) hierarchical feature representations corresponding to each image can be obtained with improved texture pattern discrimination; and (iii) overfitting problems can be minimized. Figure 10 shows the multi-resolution image analysis performance for the proposed PSAS employing for 2DFPE Database (2-class Pain levels), UNBC Database (2-class Pain levels), UNBC Database (3-class Pain levels), and BioVid Heat Pain Dataset (5-class Pain levels) databases. From this figure, it has been observed that the derived model resolves the overfitting issue and improves the proposed system’s performance.

- experiments: This experiment is about measuring the effectiveness of introducing the Transfer-learning with fine-tuning of parameters when two new CNN models are being trained on the same domain of data (i.e., images). Fine-tuning refers to taking into account the weights of one proposed CNN architecture. It shortens the training period, which leads to better results. Transfer learning is a machine learning technique in which a model that is suggested for one job is utilized as a foundation for a different model on a different task. Different transfer learning methodologies have been applied here: (i) in the first approach, we used the refreshed models, i.e., we trained both CNN architectures and from scratch using the relevant image sizes; (ii) in the second approach, we used the retrained model of both architectures. We can see that CNN architectures perform better when employing these retrain models. Table 5 shows the CNN architectures’ performance. The accuracy and F1-score are the basis for the reported performances. The results in Table 5 indicate that Approach-1 improves PSAS performance.

- experiments: This experiment begins with the application of multiple Fusion techniques on the classification scores generated by the trained and architectures. Deep-learning features are utilized to obtain the classification results, and a post-classification approach is applied for fusion. The respective CNN models generate the classification scores, which are then subjected to the Weighted Sum-rule, Product-rule, and Sum-rule procedures for post-classification fusion. The fused performance of the proposed system, resulting from various combinations of fusion methods, is presented in Table 6. The fusion results demonstrate that the proposed system performs better with the Product-rule fusion approach, using both CNN architectures, compared to the Weighted Sum-rule, Sum-rule, and Product-rule techniques. The proposed system achieves an accuracy of 85.15% for the 2-Class UNBC, 83.79% for the 3-Class UNBC, and 77.41% for the 2-Class 2DFPE database. These performance results serve as a reference point in the section below.

-

Comparison with existing System for Image-based PSAS: The performance of the proposed system has been compared with several current state-of-the-art techniques across the 2-Class 2DFPE database, the 2-Class and 3-Class UNBC-McMaster shoulder pain databases, and the 5-Class BioVid Heat Pain database. Feature extraction for the local binary pattern (LBP) and Histogram of Oriented Gradient (HoG) procedures, as utilized in [68] and [69], has been employed. Each image’s feature representation approach uses a size of pixels, and the images are divided into nine separate blocks for both the LBP and HoG approaches. From each block, a 256-dimensional LBP feature vector [69] and an 81-dimensional HoG feature vector [68] are extracted, resulting in 648 HoG features and 2304 LBP features per image. For deep feature extraction, methods like ResNet50 [70], Inception-v3 [71], and VGG16 [72] were employed, with each using an image size of . Transfer learning techniques were applied, where each network was independently trained using samples from two or three class problems. Features were then extracted from the trained networks, and neural network-based classifiers were used for test sample classification. Competing approaches such as those by Lucey et al. [65], Anay et al. [73], and Werner et al. [74] were also implemented using the same image size of . The results for all these competing techniques were obtained using identical training and testing protocols as the proposed system. These results are summarized in Table 7, which demonstrates that the proposed system outperformed the competing techniques.Hence, Table 7 presents the performance comparison for the image-based sentiment analysis system using the 2-class and 3-class pain sentiment analysis system. All experiments were conducted under the same training and testing protocols. Quantitative comparisons were made between the proposed system’s two-class classification model (A) and the competing methods: Anay et al. [73] (B), HoG [68] (C), Inception-v3 [71] (D), LBP [69] (E), Lucey et al. [65] (F), ResNet50 [70] (G), VGG16 [72] (H), and Werner et al. [74] (I). The statistical comparison of the performances between the proposed system (A) and the competing methods ({B,C,D,E,F,G,H,I}) is shown in Table 8. A one-tailed t-test [75] was conducted using the t-statistic to analyze the results. The one-tailed test assumes two hypotheses: (i) H0 (Null-hypothesis): (indicating that the proposed system (A) performs on average less than or equal to the competing method’s performance); (ii) H1 (Alternative-hypothesis): (indicating that the proposed system (A) performs better on average than the competing methods). The null hypothesis is rejected if the p-value is less than 0.05, indicating that the proposed method (A) performs better than the competing methods. For the quantitative comparison, each test dataset for the employed databases was divided into two sets. For the database, there are 298 test image samples (Set-1: 149, Set-2: 149). For the UNBC (2-Class/3-Class) problem, there are 24,199 test samples (Set-1: 12,100, Set-2: 12,099). The performances of the proposed method and the competing methods were evaluated on these test sets. Table 8 shows the results of the quantitative comparisons for the employed databases. From this table, it is evident that in every comparison between the proposed system and the competing methods, the alternative hypothesis is accepted and the null hypothesis is rejected, confirming that the proposed method (A) outperforms the competing methods.

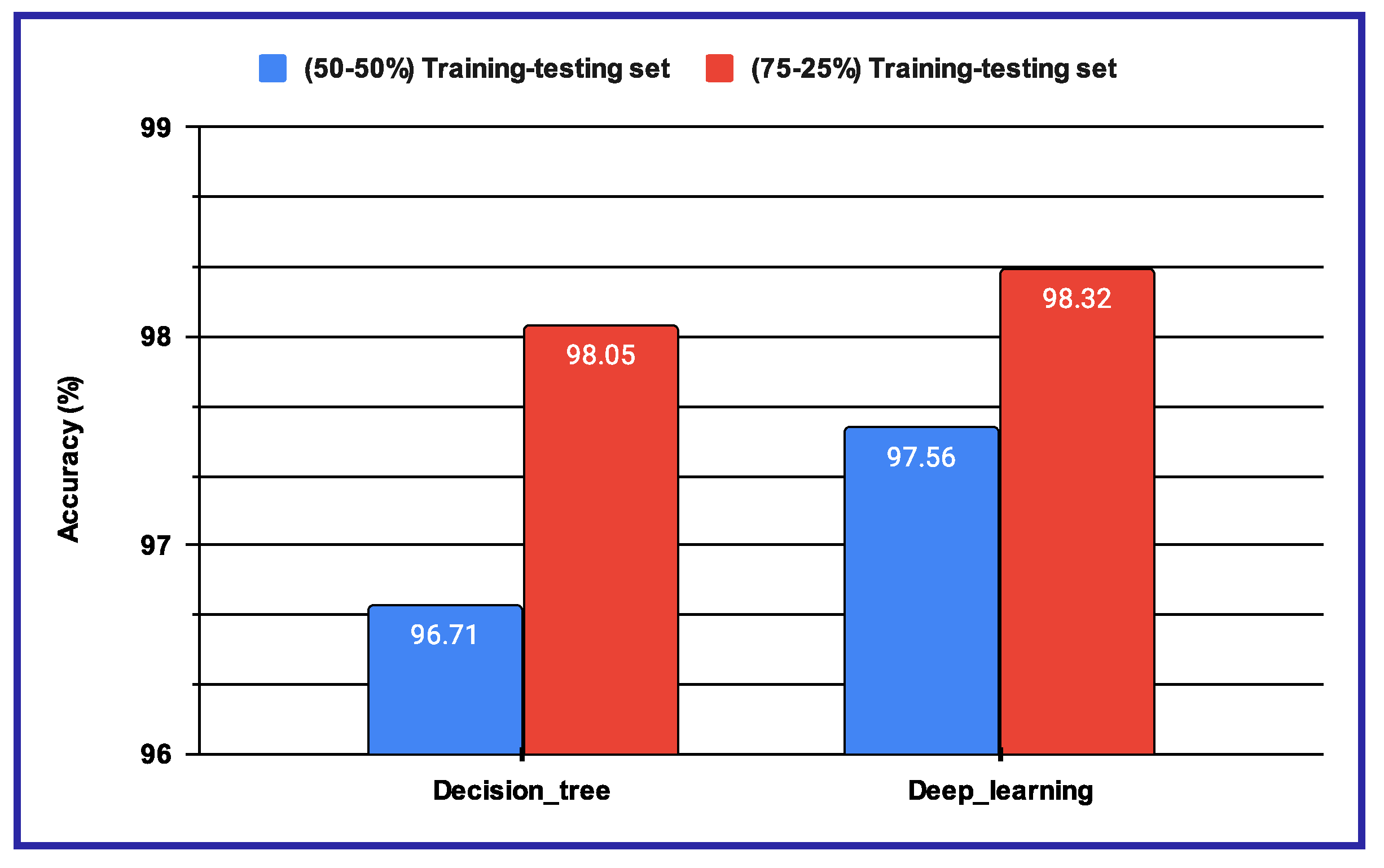

4.3. Results for Audio-Based PSAS

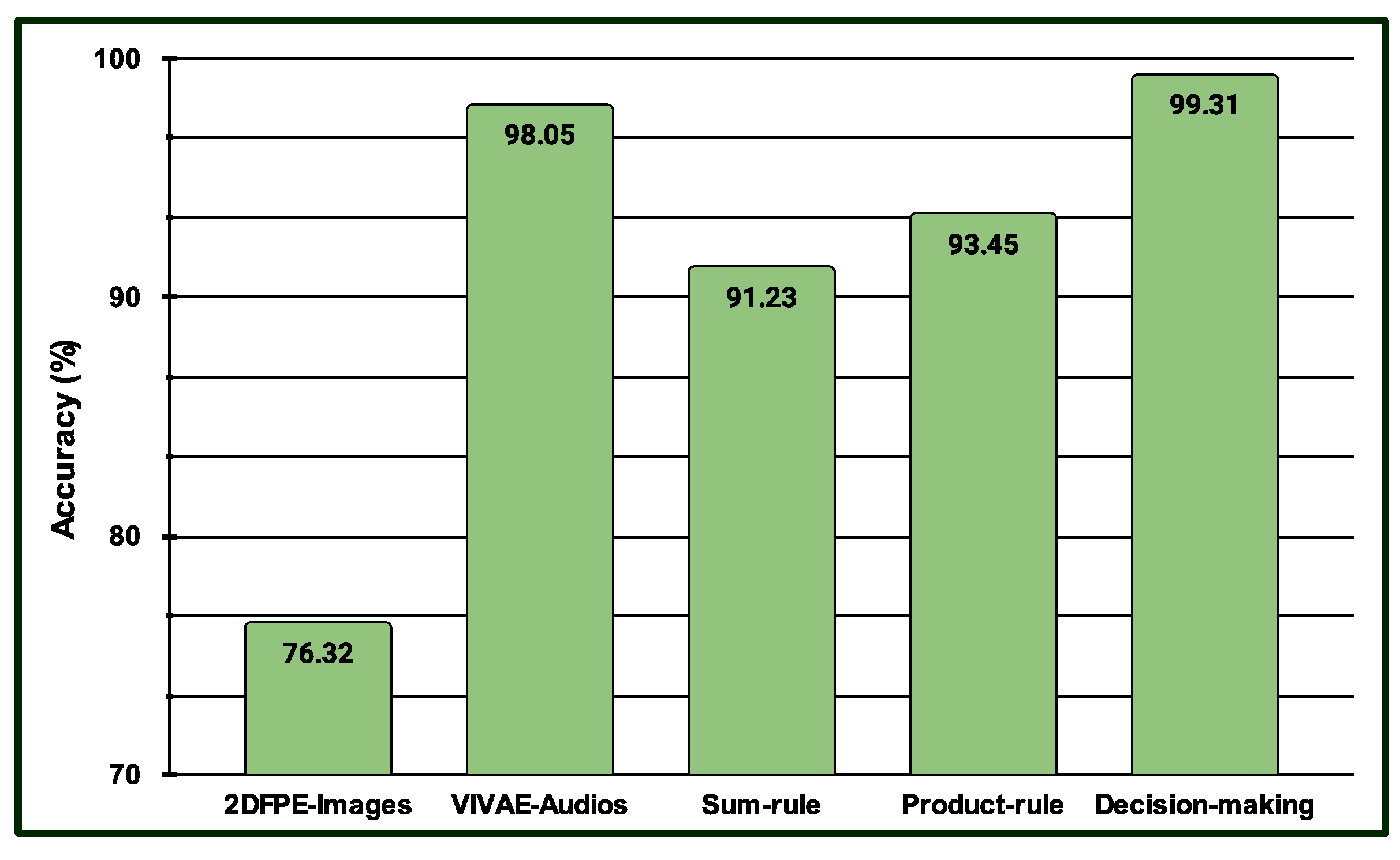

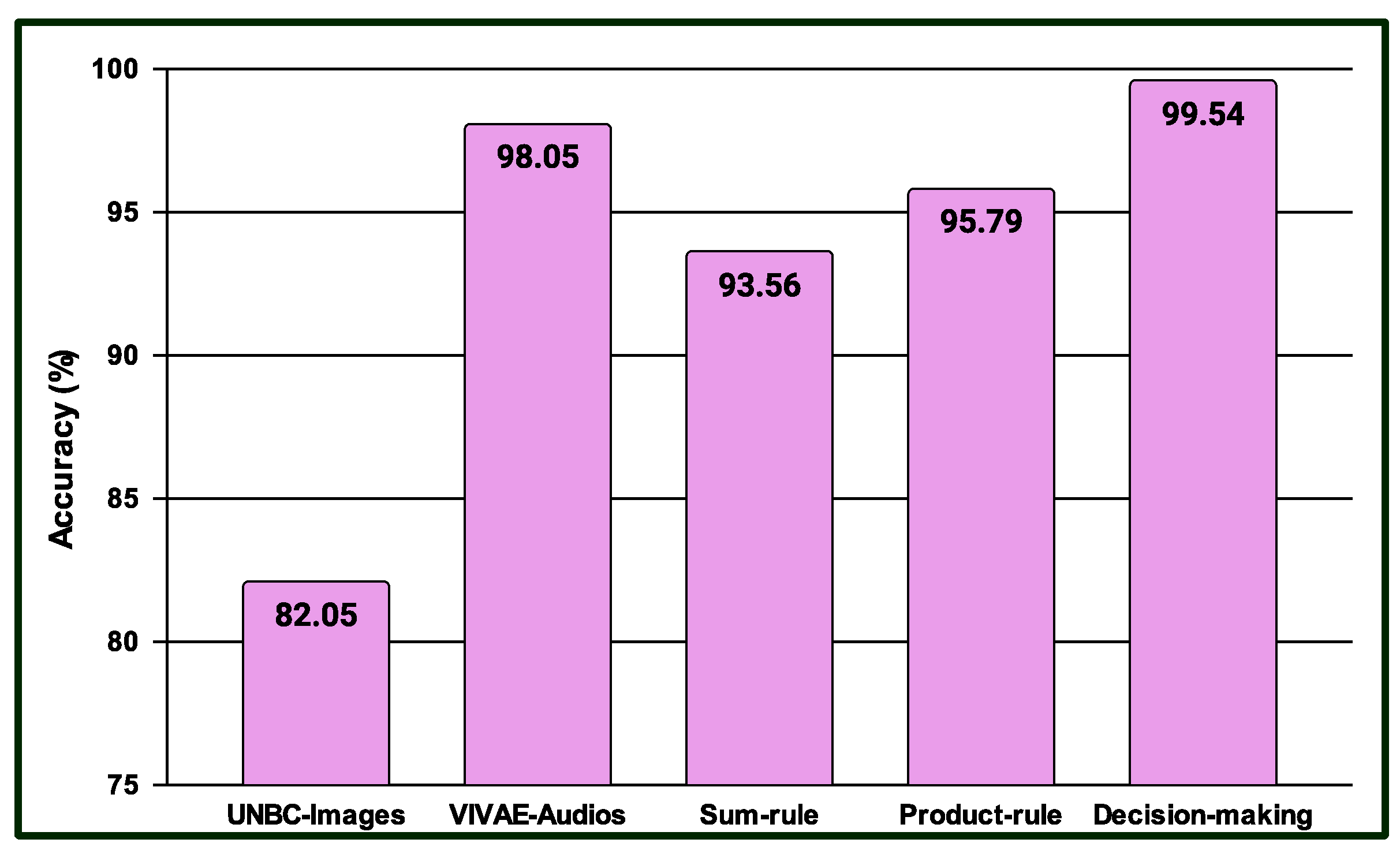

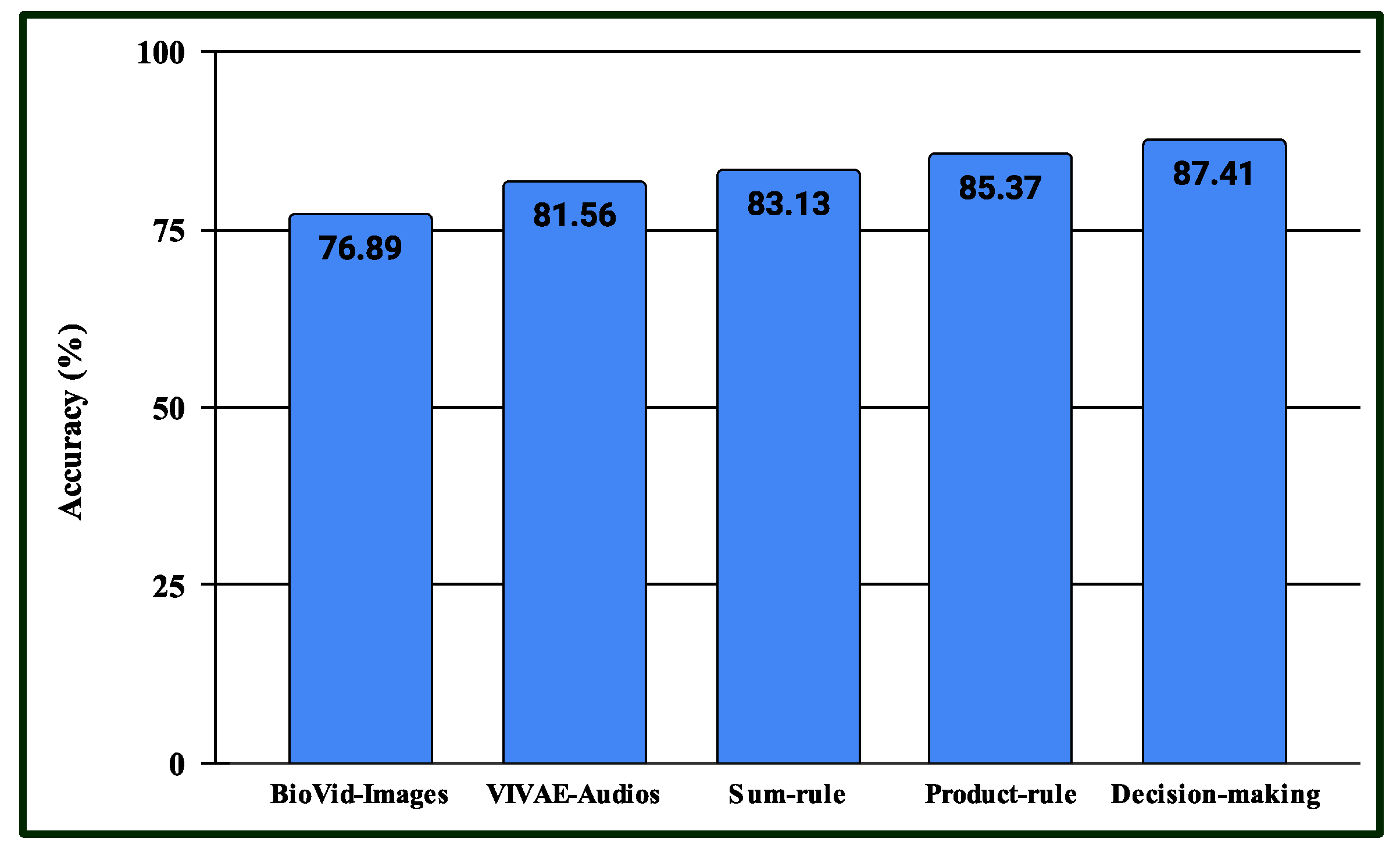

4.4. Results for Multimodal PSAS

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ande, R.; Adebisi, B.; Hammoudeh, M.; Saleem, J. Internet of Things: Evolution and technologies from a security perspective. Sustainable Cities and Society 2020, 54, 101728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, P.; Singh, Y.; Anand, P.; Bangotra, D.K.; Singh, P.K.; Hong, W.C. Internet of things: Evolution, concerns and security challenges. Sensors 2021, 21, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, G.; Alsulaiman, M.; Amin, S.U.; Ghoneim, A.; Alhamid, M.F. A facial-expression monitoring system for improved healthcare in smart cities. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 10871–10881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Saad, H.H. Challenge of pain in the cognitively impaired. Lancet (London, England) 2000, 356, 1867–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, A. Two-handed gestures for human-computer interaction. Technical report, IDIAP, 2006.

- Hasan, H.; Abdul-Kareem, S. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Static hand gesture recognition using neural networks. Artificial Intelligence Review 147–181. [CrossRef]

- Payen, J.F.; Bru, O.; Bosson, J.L.; Lagrasta, A.; Novel, E.; Deschaux, I.; Lavagne, P.; Jacquot, C. Assessing pain in critically ill sedated patients by using a behavioral pain scale. Critical care medicine 2001, 29, 2258–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuire, B.; Daly, P.; Smyth, F. Chronic pain in people with an intellectual disability: under-recognised and under-treated? Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 2010, 54, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puntillo, K.A.; Morris, A.B.; Thompson, C.L.; Stanik-Hutt, J.; White, C.A.; Wild, L.R. Pain behaviors observed during six common procedures: results from Thunder Project II. Critical care medicine 2004, 32, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.d. Facial expression of pain: an evolutionary account. Behav Brain Sci 2002, 25, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, K.; Coyne, P.J.; Key, T.; Manworren, R.; McCaffery, M.; Merkel, S.; Pelosi-Kelly, J.; Wild, L. Pain assessment in the nonverbal patient: position statement with clinical practice recommendations. Pain Management Nursing 2006, 7, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twycross, A.; Voepel-Lewis, T.; Vincent, C.; Franck, L.S.; von Baeyer, C.L. A debate on the proposition that self-report is the gold standard in assessment of pediatric pain intensity. The Clinical journal of pain 2015, 31, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredi, P.L.; Breuer, B.; Meier, D.E.; Libow, L. Pain assessment in elderly patients with severe dementia. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2003, 25, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, A.B.; Lucey, S.; Cohn, J.F.; Chen, T.; Ambadar, Z.; Prkachin, K.M.; Solomon, P.E. The painful face–pain expression recognition using active appearance models. Image and vision computing 2009, 27, 1788–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucey, P.; Cohn, J.; Howlett, J.; Lucey, S.; Sridharan, S. Recognizing emotion with head pose variation: Identifying pain segments in video. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics-Part B 2011, 41, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewort-Ford, G.; Bartlett, M.S.; Movellan, J.R. Are your eyes smiling? Detecting genuine smiles with support vector machines and Gabor wavelets. In Proceedings of the 8th Joint Symposium on Neural Computation. Citeseer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Umer, S.; Dhara, B.C.; Chanda, B. Face recognition using fusion of feature learning techniques. Measurement 2019, 146, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisogni, C.; Castiglione, A.; Hossain, S.; Narducci, F.; Umer, S. Impact of deep learning approaches on facial expression recognition in healthcare industries. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2022, 18, 5619–5627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, P.; Delany, S.J. k-Nearest neighbour classifiers-A Tutorial. ACM computing surveys (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinwart, I.; Christmann, A. Support vector machines; Springer Science & Business Media, 2008.

- LaValley, M.P. Logistic regression. Circulation 2008, 117, 2395–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, V.; Luister, A.; Reuter, C.; Czedik-Eysenberg, I.; Singer, D.; Steyrl, D.; Vettorazzi, E.; Deindl, P. Audio Feature Analysis for Acoustic Pain Detection in Term Newborns. Neonatology 2022, 119, 760–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshrat, Y.; Bloch, A.; Lerner, A.; Cohen, A.; Avigal, M.; Zeilig, G. Speech prosody as a biosignal for physical pain detection. Conf Proc 8th Speech Prosody, 2016, pp. 420–24.

- Ren, Z.; Cummins, N.; Han, J.; Schnieder, S.; Krajewski, J.; Schuller, B. Evaluation of the pain level from speech: Introducing a novel pain database and benchmarks. Speech Communication; 13th ITG-Symposium. VDE, 2018, pp. 1–5.

- Thiam, P.; Kessler, V.; Walter, S.; Palm, G.; Schwenker, F. Audio-visual recognition of pain intensity. IAPR Workshop on Multimodal Pattern Recognition of Social Signals in Human-Computer Interaction. Springer, 2017, pp. 110–126.

- Hossain, M.S. Patient state recognition system for healthcare using speech and facial expressions. Journal of medical systems 2016, 40, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Pantic, M.; Roisman, G.I.; Huang, T.S. A survey of affect recognition methods: audio, visual and spontaneous expressions. Proceedings of the 9th international conference on Multimodal interfaces, 2007, pp. 126–133.

- Hong, H.T.; Li, J.L.; Chang, C.M.; Lee, C.C. Improving automatic pain level recognition using pain site as an auxiliary task. 2019 8th International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction Workshops and Demos (ACIIW). IEEE, 2019, pp. 284–289.

- Hu, F.; Xia, G.S.; Hu, J.; Zhang, L. Transferring deep convolutional neural networks for the scene classification of high-resolution remote sensing imagery. Remote Sensing 2015, 7, 14680–14707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015, pp. 1–9.

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2012, 25, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.x.; Zhang, D.g.; Luo, G.z.; Lian, M.; Liu, B. A new method of emotional analysis based on CNN–BiLSTM hybrid neural network. Cluster Computing 2020, 23, 2901–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Vishwakarma, D.K. A comparative study on bio-inspired algorithms for sentiment analysis. Cluster Computing 2020, 23, 2969–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, H.; Harmanto, D.; Al-Absi, H.R.H. On the development of smart home care: Application of deep learning for pain detection. 2018 IEEE-EMBS Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Sciences (IECBES). IEEE, 2018, pp. 612–616.

- Haque, M.A.; Bautista, R.B.; Noroozi, F.; Kulkarni, K.; Laursen, C.B.; Irani, R.; Bellantonio, M.; Escalera, S.; Anbarjafari, G.; Nasrollahi, K. ; others. Deep multimodal pain recognition: a database and comparison of spatio-temporal visual modalities. 2018 13th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2018). IEEE, 2018, pp. 250–257.

- Menchetti, G.; Chen, Z.; Wilkie, D.J.; Ansari, R.; Yardimci, Y.; Çetin, A.E. Pain detection from facial videos using two-stage deep learning. 2019 IEEE Global Conference on Signal and Information Processing (GlobalSIP). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–5.

- Virrey, R.A.; Liyanage, C.D.S.; Petra, M.I.b.P.H.; Abas, P.E. Visual data of facial expressions for automatic pain detection. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 2019, 61, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashtipour, K.; Gogate, M.; Cambria, E.; Hussain, A. A novel context-aware multimodal framework for persian sentiment analysis. arXiv, arXiv:2103.02636 2021.

- Sagum, R.A. An Application of Emotion Detection in Sentiment Analysis on Movie Reviews. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education (TURCOMAT) 2021, 12, 5468–5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustam, F.; Khalid, M.; Aslam, W.; Rupapara, V.; Mehmood, A.; Choi, G.S. A performance comparison of supervised machine learning models for Covid-19 tweets sentiment analysis. Plos one 2021, 16, e0245909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, D.; Beveridge, S.; Mitchell, L.A.; MacDonald, R.A. Acoustic analysis and mood classification of pain-relieving music. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2011, 130, 1673–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bargshady, G.; Zhou, X.; Deo, R.C.; Soar, J.; Whittaker, F.; Wang, H. Enhanced deep learning algorithm development to detect pain intensity from facial expression images. Expert Systems with Applications 2020, 149, 113305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Al-Eidan, R.; Al-Khalifa, H.; Al-Salman, A. Deep-learning-based models for pain recognition: A systematic review. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 5984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouverneur, P.; Li, F.; Adamczyk, W.M.; Szikszay, T.M.; Luedtke, K.; Grzegorzek, M. Comparison of feature extraction methods for physiological signals for heat-based pain recognition. Sensors 2021, 21, 4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiam, P.; Bellmann, P.; Kestler, H.A.; Schwenker, F. Exploring deep physiological models for nociceptive pain recognition. Sensors 2019, 19, 4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Othman, E.; Werner, P.; Saxen, F.; Al-Hamadi, A.; Walter, S. Cross-database evaluation of pain recognition from facial video. 2019 11th International Symposium on Image and Signal Processing and Analysis (ISPA). IEEE, 2019, pp. 181–186.

- Pikulkaew, K.; Boonchieng, E.; Boonchieng, W.; Chouvatut, V. Pain detection using deep learning with evaluation system. Proceedings of Fifth International Congress on Information and Communication Technology. Springer, 2021, pp. 426–435.

- Ismail, L.; Waseem, M.D. Towards a Deep Learning Pain-Level Detection Deployment at UAE for Patient-Centric-Pain Management and Diagnosis Support: Framework and Performance Evaluation. Procedia Computer Science 2023, 220, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Shi, Y.; Yan, S.; Yan, H.m. Global-Local combined features to detect pain intensity from facial expression images with attention mechanism1. Journal of Electronic Science and Technology 2024, 100260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, E.; Werner, P.; Saxen, F.; Al-Hamadi, A.; Gruss, S.; Walter, S. Classification networks for continuous automatic pain intensity monitoring in video using facial expression on the X-ITE Pain Database. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 2023, 91, 103743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.; d’Autume, M.d.M.; Varray, C. Audio denoising algorithm with block thresholding. Image Processing 2012, 2105–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Z.; Lu, G.; Ting, K.M.; Zhang, D. A survey of audio-based music classification and annotation. IEEE transactions on multimedia 2010, 13, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, B. Mel frequency cepstral coefficients for music modeling. In International Symposium on Music Information Retrieval. Citeseer, 2000.

- Lee, C.H.; Shih, J.L.; Yu, K.M.; Lin, H.S. Automatic music genre classification based on modulation spectral analysis of spectral and cepstral features. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2009, 11, 670–682. [Google Scholar]

- Nawab, S.; Quatieri, T.; Lim, J. Signal reconstruction from short-time Fourier transform magnitude. IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing 1983, 31, 986–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Ramanan, D. Face detection, pose estimation, and landmark localization in the wild. 2012 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. IEEE, 2012, pp. 2879–2886.

- Hossain, S.; Umer, S.; Rout, R.K.; Tanveer, M. Fine-grained image analysis for facial expression recognition using deep convolutional neural networks with bilinear pooling. Applied Soft Computing 2023, 134, 109997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umer, S.; Rout, R.K.; Pero, C.; Nappi, M. Facial expression recognition with trade-offs between data augmentation and deep learning features. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A. Convolutional neural networks: an illustration in TensorFlow. XRDS: Crossroads, The ACM Magazine for Students 2016, 22, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioffe, S.; Szegedy, C. Batch normalization: Accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2015, pp. 448–456.

- Lawrence, S.; Giles, C.L.; Tsoi, A.C.; Back, A.D. Face recognition: A convolutional neural-network approach. IEEE transactions on neural networks 1997, 8, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulli, A.; Pal, S. Deep learning with Keras; Packt Publishing Ltd, 2017.

- Bergstra, J.; Breuleux, O.; Bastien, F.; Lamblin, P.; Pascanu, R.; Desjardins, G.; Turian, J.; Warde-Farley, D.; Bengio, Y. Theano: a CPU and GPU math expression compiler. Proceedings of the Python for scientific computing conference (SciPy). Austin, TX, 2010, Vol. 4, pp. 1–7.

- Holz, N.; Larrouy-Maestri, P.; Poeppel, D. The variably intense vocalizations of affect and emotion (VIVAE) corpus prompts new perspective on nonspeech perception. Emotion 2022, 22, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucey, P.; Cohn, J.F.; Prkachin, K.M.; Solomon, P.E.; Matthews, I. Painful data: The UNBC-McMaster shoulder pain expression archive database. 2011 IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG). IEEE, 2011, pp. 57–64.

- 2d Face dataset with Pain Expression:. http://pics.psych.stir.ac.uk/2D_face_sets.htm.

- Walter, S.; Gruss, S.; Ehleiter, H.; Tan, J.; Traue, H.C.; Werner, P.; Al-Hamadi, A.; Crawcour, S.; Andrade, A.O.; da Silva, G.M. The biovid heat pain database data for the advancement and systematic validation of an automated pain recognition system. 2013 IEEE international conference on cybernetics (CYBCO). IEEE, 2013, pp. 128–131.

- Umer, S.; Dhara, B.C.; Chanda, B. Biometric recognition system for challenging faces. 2015 Fifth National Conference on Computer Vision, Pattern Recognition, Image Processing and Graphics (NCVPRIPG). IEEE, 2015, pp. 1–4.

- Umer, S.; Dhara, B.C.; Chanda, B. An iris recognition system based on analysis of textural edgeness descriptors. IETE Technical Review 2018, 35, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 2818–2826.

- McNeely-White, D.; Beveridge, J.R.; Draper, B.A. Inception and ResNet features are (almost) equivalent. Cognitive Systems Research 2020, 59, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556, arXiv:1409.1556 2014.

- Ghosh, A.; Umer, S.; Khan, M.K.; Rout, R.K.; Dhara, B.C. Smart sentiment analysis system for pain detection using cutting edge techniques in a smart healthcare framework. Cluster Computing 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, P.; Al-Hamadi, A.; Limbrecht-Ecklundt, K.; Walter, S.; Gruss, S.; Traue, H.C. Automatic pain assessment with facial activity descriptors. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2016, 8, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J.D. Nonparametric statistics: An introduction; Vol. 9, Sage, 1993.

- McFee, B.; Raffel, C.; Liang, D.; Ellis, D.P.; McVicar, M.; Battenberg, E.; Nieto, O. librosa: Audio and music signal analysis in python. Proceedings of the 14th python in science conference, 2015, Vol. 8, pp. 18–25.

| Layer | Output-shape | Feature-size | Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flatten | (1, d) | (1,d) | 0 |

| Dense | (1, 512) | (1, 512) | (1 + d) x 512 |

| BatNorm | (1, 512) | (1, 512) | 2048 |

| ActRelu | (1, 512) | (1, 512) | 0 |

| Dropout | (1, 512) | (1, 512) | 0 |

| Dense | (1, 256) | (1, 256) | (1 + 512) x 256 =131328 |

| BatNorm | (1, 256) | (1, 256) | 1024 |

| ActRelu | (1, 256) | (1, 256) | 0 |

| Dropout | (1, 256) | (1, 256) | 0 |

| Dense | (1, 128) | (1,128) | (1 + 256) x 128 =32896 |

| BatNorm | (1, 128) | (1,128) | 512 |

| ActRelu | (1, 128 | (1, 128) | 0 |

| Dropout | (1, 128) | (1, 128) | 0 |

| Dense | (1, 3) | (1, 3) | (128+1) x3=387 |

| Total-Parameters | 168195 +((1+d) x512) |

||

| Layers | Outputshape | ImageSize | Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block1 | |||||||

| Conv2D(3x3)@32 | (n,n,32) | (128, 128, 32) | 896 | ||||

| BatchNorm | (n,n,32) | (128, 128, 32) | 128 | ||||

| ActivationReLU | (n,n,32) | (128, 128, 32) | 0 | ||||

| Maxpool2D(2x2) | (n1,n1, 32), n1=n/2 | (64, 64,32) | 0 | ||||

| Dropout | (n1,n1, 32), n1=n/2 | (64, 64,32) | 0 | ||||

| Layers | Outputshape | ImageSize | Parameters | Layers | Outputshape | ImageSize | Parameters |

| Block2 | Block5 | ||||||

| Conv2D(3x3)@64 | (n1, n1, 64) | (64, 64, 64) | ((3x3x32) + 1)x64=18496 | Conv2D (3x3)@128 | (n4, n4,128) | (8, 8, 128) | ((3x3x128)+1)x128=147584 |

| BatchNorm | (n1, n1, 64) | (64, 64, 64) | 4x64 = 256 | BatchNorm | (n4, n4,128) | (8, 8, 128) | 4x128=512 |

| Activation ReLU | (n1, n1, 64) | (64 ,64 ,64) | 0 | Activation ReLU | (n4, n4,128) | (8, 8, 128) | 0 |

| Maxpool2D (2x2) | (n2, n2, 64), n2=n1/2 | (32, 32,64) | 0 | Maxpool2D (2x2) | (n5, n5,128), n5=n4/2 | (4, 4,128) | 0 |

| Dropout | (n2, n2, 64) | (32, 32,64) | 0 | Dropout | (n5, n5,128) | (4, 4,128) | 0 |

| Block3 | Block6 | ||||||

| Conv2D(3x3)@96 | (n2, n2, 96) | (32, 32, 96) | ((3x3x64)+1)x 96=55392 | Conv2D(3x3)@256 | (n5, n5, 256) | (4, 4, 256) | ((3x3x128)+1)x256=295168 |

| BatchNorm | (n2, n2, 96) | (32, 32, 96) | 4x96=384 | BatchNorm | (n5, n5, 256) | (4, 4, 256) | 4x256=1024 |

| Activation ReLU | (n2, n2, 96) | (32, 32, 96) | 0 | ActivationReLU | (n5, n5, 256) | (4, 4, 256) | 0 |

| Maxpool2D (2x2) | (n3, n3, 96), n3=n2/2 | (16, 16, 96) | 0 | Maxpool2D(2x2) | (n6, n6, 256), n6=n5/2 | (2, 2, 256) | 0 |

| Dropout | (n3, n3, 96) | (16, 16, 96) | 0 | Dropout | (n6, n6, 256) | (2, 2, 256) | 0 |

| Block4 | Block7 | ||||||

| Conv2D (3x3)@128 | (n3,n3,128) | (16,16,128) | ((3x3x96)+1)x128=110720 | Conv2D(3x3)@512 | ( n6, n6 , 512) | (2, 2, 512) | ((3x3x256)+1)x512=1180160 |

| BatchNorm | (n3,n3,128) | (16,16,128) | 4x128=512 | BatchNorm | ( n6, n6 , 512) | (2, 2, 512) | 4x512=2048 |

| Activation ReLU | (n3,n3,128) | (16,16,128) | 0 | Activation Re LU- | ( n6, n6 , 512) | (2, 2, 512) | 0 |

| Maxpool2D (2x2) | (n4,n4,128), n4=n3/2 | (8, 8, 128) | 0 | Maxpool2D(2x2) | ( n7, n7 ,512), n7=n6/2 | (1,1,512) | 0 |

| Dropout | (n4,n4,128) | (8, 8, 128) | 0 | Dropout | ( n7, n7 ,512) | (1,1,512) | 0 |

| Layer | Output Shape | Image Size | Parameter | ||||

| Flatten | (1, n7 X n7 X 512 ) | (1,512) | 0 | ||||

| Dense | (1,256) | (1,256) | (1 + 512)x 256=131328 | ||||

| Batch Normalization | (1,256) | (1,256) | 4x256=1024 | ||||

| Activation Relu | (1,256) | (1,256) | 0 | ||||

| Dropout | (1,256) | (1,256) | 0 | ||||

| Dense | (1,7) | (1,7) | (256+1)x7=1799 | ||||

| Total Parameters for The Input Image Size | 1947431 | ||||||

| Total Number of Trainable Parameters: | 1944487 | ||||||

| Non-trainable params: | 2944 | ||||||

| Layers | Outputshape | ImageSize | Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block1 | |||||||

| Conv2D(3x3)@32 | (n,n,32) | (192, 192, 32) | 896 | ||||

| BatchNorm | (n,n,32) | (192, 192, 32) | 128 | ||||

| ActivationReLU | (n,n,32) | (192, 192, 32) | 0 | ||||

| Maxpool2D(2x2) | (n1,n1, 32), n1=n/2 | (96, 96, 32) | 0 | ||||

| Dropout | (n1,n1, 32), n1=n/2 | (96, 96, 32) | 0 | ||||

| Layers | Outputshape | ImageSize | Parameters | Layers | Outputshape | ImageSize | Parameters |

| Block2 | Block5 | ||||||

| Conv2D(3x3)@64 | (n1, n1, 64) | (96, 96, 64) | ((3x3x32) + 1)x64=18496 | Conv2D (3x3)@256 | (n4, n4, 256) | (12, 12, 256) | ((3x3x128)+1)x256=295168 |

| BatchNorm | (n1, n1, 64) | (96, 96, 64) | 4x64 = 256 | BatchNorm | (n4, n4, 256) | (12, 12, 256) | 4x256=1024 |

| Activation ReLU | (n1, n1, 64) | (96, 96, 64) | 0 | Activation ReLU | (n4, n4, 256) | (12, 12, 256) | 0 |

| Maxpool2D (2x2) | (n2, n2, 64), n2=n1/2 | (48, 48, 64) | 0 | Maxpool2D (2x2) | (n5, n5, 256), n5=n4/2 | (6, 6, 256) | 0 |

| Dropout | (n2, n2, 64) | (48, 48, 64) | 0 | Dropout | (n5, n5, 256) | (6, 6, 256) | 0 |

| Block3 | Block6 | ||||||

| Conv2D(3x3)@96 | (n2, n2, 96) | (48, 48, 96) | ((3x3x64)+1)x 96=55392 | Conv2D(3x3)@512 | (n5, n5, 512) | (6, 6, 512) | ((3x3x256)+1)x512=1180160 |

| BatchNorm | (n2, n2, 96) | (48, 48, 96) | 4x96=384 | BatchNorm | (n5, n5, 512) | (6, 6, 512) | 4x512=2048 |

| Activation ReLU | (n2, n2, 96) | (48, 48, 96) | 0 | ActivationReLU | (n5, n5, 512) | (6, 6, 512) | 0 |

| Maxpool2D (2x2) | (n3, n3, 96), n3=n2/2 | (24, 24, 96) | 0 | Maxpool2D(2x2) | (n6, n6, 512), n6=n5/2 | (3, 3, 512) | 0 |

| Dropout | (n3, n3, 96) | (24, 24, 96) | 0 | Dropout | (n6, n6, 512) | (3, 3, 512) | 0 |

| Block4 | Block7 | ||||||

| Conv2D (3x3)@128 | (n3,n3,128) | (24, 24, 128) | ((3x3x96)+1)x128=110720 | Conv2D(3x3)@1024 | (n6, n6, 1024) | (3, 3, 1024) | ((3x3x512)+1)x1024=4719616 |

| BatchNorm | (n3,n3,128) | (24, 24, 128) | 4x128=512 | BatchNorm | (n6, n6, 1024) | (3, 3, 1024) | 4x1024=4096 |

| Activation ReLU | (n3,n3,128) | (24, 24, 128) | 0 | ActivationReLU | (n6, n6, 1024) | (3, 3, 1024) | 0 |

| Maxpool2D (2x2) | (n4,n4,128), n4=n3/2 | (12, 12, 128) | 0 | Maxpool2D(2x2) | (n7, n7, 1024), n7=n6/2 | (1, 1, 1024) | 0 |

| Dropout | (n4,n4,128) | (12, 12, 128) | 0 | Dropout | (n7, n7, 1024) | (1, 1, 1024) | 0 |

| Layer | Output Shape | Image Size | Parameter | ||||

| Flatten | (1, n7 X n7 X 1024 ) | (1,1024) | 0 | ||||

| Dense | (1,256) | (1,256) | (1 + 1024)x 256=262400 | ||||

| Batch Normalization | (1,256) | (1,256) | 4x256=1024 | ||||

| Activation Relu | (1,256) | (1,256) | 0 | ||||

| Dropout | (1,256) | (1,256) | 0 | ||||

| Dense | (1,7) | (1,7) | (256+1)x7=1799 | ||||

| Total Parameters for The Input Image Size | 6654119 | ||||||

| Total Number of Trainable Parameters: | 6649383 | ||||||

| Non-trainable params: | 4736 | ||||||

| 2DFPE Database (2-class Pain levels) | |

|---|---|

| No-Pain () | 298 |

| Pain () | 298 |

| UNBC Database (2-class Pain levels) | |

| No-Pain () | 40029 |

| Pain () | 8369 |

| UNBC Database (3-class Pain levels) | |

| No-Pain (NP) () | 40029 |

| Low-Pain (LP) () | 2909 |

| High-Pain (HP) () | 5460 |

| BioVid Heat Pain Dataset (5-class Pain levels) | |

| No-Pain () | 6900 |

| Pain Level-1 () | 6900 |

| Pain Level-2 () | 6900 |

| Pain Level-3 () | 6900 |

| Pain Level-4 () | 6900 |

| Dataset | Using | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc.(%) | F1-Score | Acc.(%) | F1-Score | |

| 2DFPE (2-class Pain levels) | 75.27 | 0.7563 | 72.22 | 0.7041 |

| UNBC (2-class Pain levels) | 83.11 | 0.8174 | 83.16 | 0.7918 |

| UNBC (3-class Pain levels) | 82.44 | 0.8437 | 82.36 | 0.8213 |

| BioVid (5-class Pain levels) | 34.11 | 0.3304 | 32.73 | 0.3016 |

| Dataset | Using | |||

| 2DFPE (2-class Pain levels) | 75.81 | 0.7533 | 76.14 | 0.7524 |

| UNBC (2-class Pain levels) | 84.12 | 0.7916 | 83.53 | 0.7414 |

| UNBC (3-class Pain levels) | 82.46 | 0.8334 | 82.37 | 0.8103 |

| BioVid (5-class Pain levels) | 37.45 | 0.3571 | 36.89 | 0.3518 |

| Method | 2DFPE (2-CPL) |

UNBC (2-CPL) |

UNBC (3-CPL) |

BioVid (5-CPL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A1) | 75.27 | 83.11 | 82.44 | 34.11 |

| (A2) | 72.22 | 83.16 | 82.36 | 32.73 |

| Sum-rule (A1+A2) | 75.56 | 83.47 | 82.51 | 34.67 |

| Product-rule (A1xA2) | 76.67 | 84.11 | 83.42 | 35.13 |

| Weighted Sum-rule (A1A2) | 76.37 | 84.11 | 83.15 | 35.23 |

| (A1) | 75.81 | 84.27 | 82.46 | 37.45 |

| (A2) | 76.14 | 83.53 | 82.37 | 36.89 |

| Sum-rule (A1+A2) | 76.81 | 84.69 | 82.74 | 37.89 |

| Product-rule (A1xA2) | 77.41 | 85.15 | 83.38 | 38.04 |

| Weighted Sum-rule (A1A2) | 77.23 | 85.07 | 83.17 | 37.83 |

| 3-Class UNBC-McMaster | 2-Class UNBC-McMaster | 2-Class 2DFPE | 5-Class BioVid | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Acc. (%) | F1-score | Acc. (%) | F1-score | Acc. (%) | F1-score | Acc. (%) | F1-score |

| Anay et al. | 82.54 | 0.7962 | 83.71 | 0.8193 | 75.67 | 0.7391 | 27.33 | 26.89 |

| HoG | 63.19 | 0.6087 | 73.29 | 0.6967 | 68.61 | 0.6364 | 24.34 | 24.17 |

| Inception-v3 | 72.19 | 0.6934 | 76.04 | 0.7421 | 63.89 | 0.6172 | 23.84 | 22.31 |

| LBP | 65.89 | 0.6217 | 75.92 | 0.7156 | 67.34 | 0.6386 | 26.10 | 25.81 |

| Lucey et al. | 80.81 | 0.7646 | 80.73 | 0.7617 | 72.58 | 0.6439 | 29.46 | 28.63 |

| ResNet50 | 74.40 | 0.7145 | 77.79 | 0.7508 | 63.78 | 0.6154 | 28.92 | 28.78 |

| VGG16 | 74.71 | 0.7191 | 76.16 | 0.738 | 61.98 | 0.5892 | 25.64 | 23.55 |

| Werner et al. | 75.98 | 0.7233 | 76.10 | 0.7531 | 66.17 | 0.6148 | 31.76 | 29.61 |

| Proposed | 83.38 | 0.8174 | 85.07 | 0.8349 | 77.41 | 0.7528 | 37.42 | 35.84 |

| 3-Class UNBC-McMaster | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Set-1 | Set-2 | t-statistic, p-value | Remarks | ||

| Proposed (A) | 85.21 | 81.89 | 79.05 | 3.1123 | H0: Null hypothesis; H1: Alternative hypothesis | |

| Anay et al. (B) | 83.12 | 80.45 | 84.51 | 0.18 | 0.1942, | H0 is accepted, |

| HoG (C) | 69.74 | 64.56 | 65.21 | 0.25 | 10.31, | H0 is rejected, |

| Inception-v3 (D) | 74.31 | 72.61 | 71.39 | 2.42 | 7.54, | H0 is rejected, |

| LBP (E) | 71.36 | 62.72 | 67.04 | 37.32 | 3.5674, | H0 is rejected, |

| Lucey et al. (F) | 82.78 | 80.45 | 80.21 | 12.33 | 7.54, | H0 is rejected, |

| ResNet50 (G) | 76.72 | 75.91 | 76.32 | 0.33 | 4.23, | H0 is rejected, |

| VGG16 (H) | 73.33 | 76.23 | 74.78 | 4.21 | 3.97, | H0 is rejected, |

| Werner et al. (I) | 75.89 | 74.52 | 75.20 | 0.94 | 4.64, | H0 is rejected, |

| 2-Class UNBC-McMaster | ||||||

| Method | Set-1 | Set-2 | t-statistic, p-value | Remarks | ||

| Proposed (A) | 87.43 | 85.81 | 79.05 | 3.1123 | H0: Null hypothesis; H1: Alternative hypothesis | |

| Anay et al. (B) | 82.17 | 84.29 | 84.21 | 2.14 | 4.4314, | H0 is rejected, |

| HoG (C) | 76.33 | 75.01 | 74.96 | 0.25 | 10.31, | H0 is rejected, |

| Inception-v3 (D) | 77.45 | 75.19 | 76.32 | 2.55 | 7.40, | H0 is rejected, |

| LBP (E) | 73.23 | 76.93 | 73.81 | 3.70 | 7.39, | H0 is rejected, |

| Lucey et al. (F) | 82.19 | 81.89 | 82.04 | 0.04 | 5.55, | H0 is rejected, |

| ResNet50 (G) | 79.31 | 78.05 | 78.68 | 0.79 | 7.73, | H0 is rejected, |

| VGG16 (H) | 77.45 | 71.38 | 74.41 | 18.42 | 3.88, | H0 is rejected, |

| Werner et al. (I) | 74.38 | 73.67 | 74.03 | 0.25 | 14.24, | H0 is rejected, |

| 2-Class 2DFPE | ||||||

| Method | Set-1 | Set-2 | t-statistic, p-value | Remarks | ||

| Proposed (A) | 77.41 | 81.91 | 79.66 | 10.12 | H0: Null hypothesis; H1: Alternative hypothesis | |

| Anay et al. (B) | 75.67 | 76.06 | 75.87 | 0.08 | 1.68, | H0 is accepted, |

| HoG (C) | 68.61 | 72.71 | 70.66 | 8.40 | 2.95, | H0 is rejected, |

| Inception-v3 (D) | 63.89 | 65.07 | 64.48 | 0.70 | 6.52, | H0 is rejected, |

| LBP (E) | 67.34 | 69.47 | 68.40 | 2.27 | 4.52, | H0 is rejected, |

| Lucey et al. (F) | 72.58 | 75.01 | 73.80 | 2.95 | 2.29, | H0 is accepted, |

| ResNet50 (G) | 63.78 | 65.39 | 64.59 | 1.30 | 6.30, | H0 is rejected, |

| VGG16 (H) | 61.98 | 64.14 | 63.06 | 2.33 | 6.65, | H0 is rejected, |

| Werner et al. (I) | 69.05 | 71.37 | 70.21 | 2.69 | 3.73, | H0 is rejected, |

| 5-Class BioVid | ||||||

| Method | Set-1 | Set-2 | t-statistic, p-value | Remarks | ||

| Proposed (A) | 37.67 | 37.81 | 37.42 | 0.62 | H0: Null hypothesis; H1: Alternative hypothesis | |

| Anay et al. (B) | 28.15 | 26.41 | 26.96 | 2.13 | 15.4437, | H0 is rejected, |

| HoG (C) | 23.05 | 25.24 | 24.34 | 2.62 | 17.7968, | H0 is rejected, |

| Inception-v3 (D) | 22.78 | 24.89 | 23.84 | 2.23 | 13.15, | H0 is rejected, |

| LBP (E) | 25.89 | 26.31 | 26.10 | 0.09 | 52.58, | H0 is rejected, |

| Lucey et al. (F) | 29.78 | 29.15 | 29.46 | 0.20 | 25.64, | H0 is rejected, |

| ResNet50 (G) | 28.56 | 29.28 | 28.92 | 0.26 | 24.049, | H0 is rejected, |

| VGG16 (H) | 25.09 | 26.18 | 25.64 | 0.59 | 22.03, | H0 is rejected, |

| Werner et al. (I) | 31.34 | 32.17 | 31.76 | 0.34 | 14.22, | H0 is rejected, |

| 50-50% training-testing set | 75-25% training-testing set | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical features | ||||||||

| Classifier | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

| Logistic-Regression | 49.56 | 24.76 | 49.56 | 33.52 | 50.21 | 25.12 | 50.21 | 33.43 |

| K-Nearest-Neighbors | 75.11 | 58.17 | 75.11 | 64.47 | 52.41 | 50.43 | 50.63 | 49.22 |

| Decision-Tree | 75.11 | 58.17 | 75.11 | 64.47 | 50.21 | 25.12 | 50.21 | 33.43 |

| Support-Vector-Machine | 49.56 | 24.76 | 49.56 | 33.52 | 50.21 | 25.14 | 50.21 | 33.43 |

| MFCC features | ||||||||

| Logistic-Regression | 52.23 | 35.63 | 52.23 | 39.52 | 75.34 | 58.18 | 75.07 | 64.74 |

| K-Nearest-Neighbors | 52.23 | 35.63 | 52.23 | 39.52 | 75.66 | 63.29 | 75.22 | 67.39 |

| Decision-Tree | 95.18 | 93.52 | 92.38 | 92.73 | 97.57 | 96.45 | 95.81 | 95.08 |

| Support-Vector-Machine | 26.27 | 9.63 | 26.41 | 13.48 | 97.43 | 96.21 | 95.72 | 94.69 |

| Spectra features | ||||||||

| Logistic-Regression | 49.71 | 33.12 | 49.76 | 39.44 | 75.18 | 58.37 | 75.18 | 64.77 |

| K-Nearest-Neighbors | 75.13 | 58.17 | 75.21 | 64.53 | 75.18 | 53.37 | 75.18 | 64.77 |

| Decision-Tree | 96.45 | 95.41 | 95.43 | 94.21 | 98.51 | 97.49 | 97.43 | 97.19 |

| Support-Vector-Machine | 96.31 | 95.23 | 94.24 | 93.19 | 75.18 | 58.37 | 75.18 | 64.77 |

| Data Type | Image Classification | Audio Classification | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN Models | |||

| Trainable Parameters | 1947431 | 6654119 | 281,603 |

| Non-Trainable Parameters | 2944 | 4736 | 1,792 |

| Total Parameters | 1944487 | 6649383 | 283,395 |

| Time | 1.04 | 1.06 | 0.43 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).