1. Introduction

AUGMENTED Reality (AR) has emerged as a transformative technology that enables the seamless overlay of virtual elements onto the real environment in real time, using devices such as smartphones, tablets, or smart glasses. Initially popularized in entertainment and education [

1], AR is now increasingly applied to technical domains such as civil engineering, urban planning, geospatial analysis, and smart cities. It has also been explored in outdoor sports environments, where pervasive AR systems support activity recognition and user-centered applications [

2]. The concept of the virtuality continuum introduced by Milgram and Kishino (1994) positioned AR between the physical and virtual worlds, highlighting its unique suitability for tasks requiring interaction with real spatial environments [

3]. Recent advances in mobile platforms such as Apple’s ARKit and Google’s ARCore have made it feasible to perform real-time outdoor measurements with consumer-grade devices, opening new opportunities for professional applications [

4].

Despite this progress, outdoor AR measurement still faces major challenges. Calibration inaccuracies, sensor noise, and environmental variability, such as poor lighting, reflective surfaces, or degraded GPS signals in urban canyons, can significantly compromise precision. While computer vision methods such as Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) are widely available in mobile devices, they struggle in low-texture or dynamic environments. Depth sensors such as LiDAR or Time-of-Flight (ToF) cameras provide higher accuracy, but remain limited to premium devices and often consume substantial energy. GPS and Inertial Measurement Units (IMU) offer scalability for large-scale outdoor tasks but lack precision at short ranges. Recent studies have shown the potential of combining multiple sensors (e.g., SLAM + LiDAR + IMU) through fusion strategies, yet most efforts remain confined to controlled conditions or hardware-specific implementations.

1.1. Motivation and Main Gaps

Based on our review of the literature, three main gaps remain unaddressed:

- 1)

Lack of adaptive sensor fusion strategies that can dynamically select and integrate sensors under diverse and unpredictable outdoor conditions.

- 2)

Scarcity of open and replicable datasets of outdoor AR based geospatial measurements, limiting benchmarking and reproducibility of research.

- 3)

Limited comparative validation of AR measurement methods across real-world scenarios, particularly in urban environments with heterogeneous conditions.

To address these gaps, this work introduces EfMAR (Effective Framework Measurement with Augmented Reality), a modular and scalable architecture designed for accurate outdoor AR-based distance measurements. EfMAR builds on a layered design that integrates sensing, processing, measurement, and visualization modules, with an adaptive sensor fusion mechanism capable of optimizing accuracy under variable conditions. Unlike existing AR applications that rely on single sensor pipelines, EfMAR formalizes a generalizable model that can be applied across multiple devices and contexts.

Existing mobile augmented reality frameworks, such as Google ARCore and Apple Measure, rely primarily on visual–inertial SLAM and coarse GNSS positioning, which can lead to reduced accuracy in outdoor urban environments. These limitations are mainly associated with SLAM drift in large-scale scenes, sensitivity to lighting variations, and GNSS degradation in urban canyons, where multipath and signal occlusion are common [

23,

26,

28]. As a result, distance measurements obtained through current mobile AR solutions often exhibit significant uncertainty when applied to real-world outdoor geospatial scenarios.

EfMAR extends beyond implementation by formalizing a reusable theoretical model for adaptive sensor fusion in outdoor AR measurement systems, bridging engineering practice and conceptual generalization. This theoretical dimension positions EfMAR not only as an operational system but also as a reproducible framework capable of supporting future AR based measurement research and comparative evaluations.

1.2. Contributions

This work makes the following key contributions to the field of outdoor AR-based geospatial measurement:

1) Theoretical Framework. We propose EfMAR (Effective Framework Measurement with Augmented Reality), a modular and layered architecture that formalizes outdoor AR-based measurement into sensing, processing, measurement, and visualization components. This framework is generalizable beyond the presented prototype, offering a foundation for future AR measurement systems.

2) Adaptive Sensor Fusion. We introduce an adaptive fusion mechanism that dynamically integrates SLAM, LiDAR, ToF, GPS, and IMU data. By adjusting sensor weights based on environmental conditions (e.g., lighting, texture, GPS degradation), EfMAR ensures robust accuracy where single-sensor approaches fail.

3) Real-World Dataset. We provide a novel dataset of AR based geospatial measurements, collected across diverse urban scenarios (open squares, narrow streets, shaded areas, and construction sites). This dataset, benchmarked against ground-truth topographic instruments, is publicly released to foster reproducibility and benchmarking.

4) Comprehensive Validation. We conduct a comparative evaluation with more than 500 measurements, analyzing accuracy across short, medium, and long distances. EfMAR is benchmarked against commercial AR applications (Apple Measure, ARCore Measure, Polycam), demonstrating significant accuracy gains and adaptability under real-world outdoor conditions.

5) Practical Integration. Beyond accuracy, EfMAR supports interoperability with professional workflows by enabling export to BIM and GIS formats (IFC, DXF), addressing a key barrier to AR adoption in engineering, urban planning, and smart city applications.

The rest of this work is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on AR measurement technologies and their limitations.

Section 3 explains the dataset as well as the field data collection process.

Section 4 and

Section 5 introduces proposed method and the EfMAR architecture with its layered components.

Section 6 describes illustrative use-cases.

Section 7 evaluates the performance with measurements and analysis of results of our comparative evaluation, also discusses the implications, trade-offs, and limitations of EfMAR. Finally,

Section 8 concludes with future directions for cross-platform implementation, UAV integration, and AI-based error correction.

2. Related Work

The concept of extending mobile devices with nearby computation offloading was first introduced through VM-based cloudlets [

5], laying the foundation for mobile edge computing. More recent surveys emphasize how 5G and MEC architectures can enhance the scalability and responsiveness of mobile AR systems [

5]. AR applications have evolved significantly over the past decade, expanding from entertainment and education to technical domains such as civil engineering, geospatial analysis, and smart city development [

6]. Early surveys by Billinghurst et al. and Zhou et al. highlighted the potential of AR in tracking, display and interaction, and applications [

7,

8,

9]. while Cao et al. provided a broader overview of user interfaces, frameworks, and intelligence in mobile AR systems [

10]. More recent overviews emphasize the ubiquity of AR on mobile platforms, where devices integrate multiple sensors, including RGB cameras, IMUs, GPS, and, in premium models, LiDAR or ToF modules creating opportunities for hybrid measurement approaches that were previously unavailable in consumer hardware [

11,

8]. The integration of mobile computing with edge resources has long been considered a way to overcome the limitations of resource-constrained devices. Satyanarayanan et al. introduced the concept of VM-based cloudlets to extend mobile capabilities through nearby computation offloading, an approach that has since evolved into mobile edge computing architectures supporting AR [

6].

Beyond technical challenges, AR has also been studied in terms of its impact on human attention and safety. For instance, Sawyer et al. examined Google Glass in driving contexts, raising concerns about potential distraction versus assistance [

12].

2.1. SLAM-based Approaches

Computer vision techniques, particularly Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM), have become central to AR measurement. SLAM enables real-time mapping and supports distance estimation between objects. Commercial solutions such as Apple’s Measure and Google’s ARCore rely mainly on SLAM. However, the accuracy of SLAM-based methods decreases under challenging outdoor conditions such as low texture surfaces, poor lighting, or dynamic environments [

13,

14]. Recent studies integrate deep learning to enhance feature extraction and robustness, showing improved results in visually degraded contexts [

15].

2.2. Depth-Sensor Approaches

LiDAR and ToF sensors extend AR capabilities by directly providing depth information. LiDAR-equipped mobile devices (e.g., iPhone Pro, iPad Pro) achieve centimeter-level accuracy, enabling façade mapping and terrain assessment [

16].

ToF sensors, available in some Android smartphones, offer lower-cost alternatives but typically with reduced precision. Recent research has explored machine learning techniques to approximate LiDAR-level performance with ToF devices [

15], suggesting new possibilities for low-cost geospatial AR.

2.3. Marker-based Approaches

Fiducial markers and QR codes remain widely used for precise measurement in constrained environments such as construction or archaeological sites [

17]. While markers ensure reliability, their main drawback is the requirement of physical placement, which limits scalability in dynamic or large-scale urban settings.

2.4. Geolocation and IMU Approaches

GPS and IMU-based methods are well established in large-scale geospatial applications, particularly in agriculture, forestry, and civil engineering [

18]. Despite their utility for positioning, accuracy at short distances is limited, often resulting in errors of several meters in dense urban areas. Hybrid strategies combining GPS with SLAM or LiDAR are being investigated to mitigate these limitations [

14].

2.5. Hybrid and UAV-based Approaches

The integration of UAVs with AR and depth sensors has recently gained attention for applications in structural inspection and large-scale mapping. UAV-based AR provides access to occluded or hazardous sites and allows seamless integration with photogrammetry and GIS workflows [

19]. Nevertheless, these systems increase operational complexity and cost, restricting their widespread adoption.

2.6. Research Gaps

Despite these advances, several gaps remain in the current related work: Adaptive Sensor Fusion in Outdoor AR. Most existing approaches rely on single-sensor pipelines (e.g., SLAM-only or LiDAR-only). Recent work on sensor fusion demonstrates improved accuracy, but strategies remain rigid and tailored to specific hardware setups. Few systems implement adaptive fusion mechanisms capable of dynamically selecting the best sensor combination depending on environmental conditions (e.g., urban canyons, shaded areas, reflective surfaces). Open and Benchmarkable Datasets. A critical limitation is the lack of public datasets of outdoor AR measurements that combine different sensing modalities (SLAM, LiDAR, ToF, GPS/IMU). Without such datasets, reproducibility and benchmarking remain limited, hindering fair comparisons across studies and applications.

2.7. Systematic Validation in Real-world Scenarios

While controlled experiments show promising accuracy, comprehensive validation in real outdoor environments with varying lighting, weather, and occlusion conditions remains scarce. Many studies use synthetic or lab-based datasets, which fail to capture the variability of real urban contexts.

Integration with Professional Workflows. AR measurement systems are often evaluated in isolation. Limited research addresses their integration with Building Information Modeling (BIM), CAD tools, or GIS platforms, which are essential for adoption in engineering, surveying, and urban planning practices.

By addressing these gaps, the present work advances the field by proposing EfMAR, a modular AR architecture with adaptive sensor fusion, validated with a real-world dataset, and benchmarked against existing AR applications.

To synthesize the current landscape of AR measurement technologies,

Table 1 compares the most relevant approaches, evaluating their accuracy, hardware requirements, portability, and typical applications. This structured overview integrates both classical methods (e.g., fiducial markers, GPS/IMU) and recent advances (e.g., LiDAR-equipped mobile devices, hybrid sensor fusion approaches reported in 2023–2025 studies).

As shown in

Table 1, no single technology fulfills all requirements for outdoor geospatial measurements. SLAM and ToF methods offer high portability but suffer from reduced precision under challenging lighting or texture conditions. LiDAR and fiducial markers deliver centimeter-level accuracy, yet their applicability is constrained by hardware availability and environmental setup. GPS + IMU methods scale well to large outdoor areas but lack precision for short-range measurements, making them unsuitable for tasks such as façade alignment. Recent studies confirm that hybrid sensor fusion strategies (e.g., SLAM + LiDAR + IMU) achieve the best accuracy and robustness across conditions [

14,

19]. However, these methods remain costly and hardware-dependent, underscoring the need for adaptive and portable solutions such as EfMAR.

2.8. Dataset

The dataset used in this study was collected to evaluate the performance of multiple distance measurement technologies in outdoor urban environments. It comprises real-world scenes with diverse scales, lighting conditions, and occlusions, including streets, open squares, and semi-indoor passageways. Data were captured using the sensors listed in

Table 1: RGB cameras for SLAM, LiDAR scanners for dense 3D mapping, ToF sensors for short-range depth, QR/Fiducial markers for reference points, GPS + IMU for trajectory tracking, and hybrid sensor fusion combining RGB, LiDAR, and IMU.

Ground-truth distances were obtained through high-precision LiDAR scans, surveyed markers, and differential GPS where available, enabling metric-level evaluation of individual and fused sensor performance. All data streams were timestamped and synchronized, comprising video sequences, point clouds, depth maps, sensor logs, and marker positions.

This dataset supports quantitative evaluation of distance measurement accuracy, drift accumulation, and robustness under challenging conditions such as occlusions, lighting variations, and urban canyon effects. It provides a standardized basis for comparative analysis, facilitating the benchmarking of SLAM, LiDAR, ToF, GPS/IMU, and hybrid sensor fusion approaches in realistic outdoor scenarios.

3. Dataset and Field Data Collection

3.1. Test Environments and Locations

Field data were collected in multiple outdoor scenarios representative of real-world geospatial measurement conditions, including dense urban environments, semi-urban areas, and open outdoor spaces. Urban measurements were conducted in areas characterized by building-induced GNSS degradation and visual occlusions, while semi-urban and open environments provided comparatively favorable visibility and signal conditions.

3.2. Devices and Sensor Configuration

Data acquisition was performed using consumer-grade mobile devices equipped with RGB cameras, inertial measurement units (IMU), GNSS receivers, and, when available, depth sensing capabilities such as LiDAR or Time-of-Flight (ToF) sensors. All measurements relied on sensors natively available on the mobile platforms, without external hardware augmentation.

3.3. Data Acquisition Protocol

For each test scenario, distance measurements were acquired by positioning the mobile device at known reference points and estimating target distances using the EfMAR framework. Ground truth values were obtained through manual measurement tools where feasible. Each measurement was repeated multiple times to mitigate random sensor noise.

3.4. Environmental Conditions

Measurements were conducted under varying environmental conditions, including different lighting levels and weather situations such as clear sky and partially cloudy conditions. Although weather parameters were not explicitly controlled, their potential influence on sensor performance, particularly on visual tracking and depth estimation, was considered during analysis.

3.5. Dataset Composition

The dataset comprises a total of 584 measurement instances. Among these, a subset corresponds to real-world field measurements collected in outdoor environments, while the remaining samples were generated through controlled synthetic augmentation informed by existing literature. The real-world subset was primarily used to validate the plausibility of the simulated scenarios and to assess consistency trends.

3.6. Dataset Limitations

Despite providing a diverse set of scenarios, the dataset presents limitations. The number of real-world measurements remains constrained due to practical acquisition challenges, and certain environmental variables, such as precise meteorological parameters, were not systematically recorded. Consequently, the dataset is primarily intended to support comparative performance analysis rather than to establish absolute accuracy.

4. Proposed Method

We intend to address the technologies presented in the previous section, as well as to install the applications one by one to compare their suitability, and answer the two research questions. Testing applications in practice will help to better understand their capabilities and limitations, specifically in outdoor environments, using the minimum number of components and sensors possible with augmented reality technology on a current smartphone, with the Android operating system version 13. Testing in outdoor environments with the minimum number of sensors will help identify which solutions rely more on software and computer vision algorithms, rather than specific hardware. The metrics and criteria for comparing AR measurement applications in outdoor environments are in

Table 2 for data collection, and their metrics and criteria for comparing AR measurements in outdoor environments.

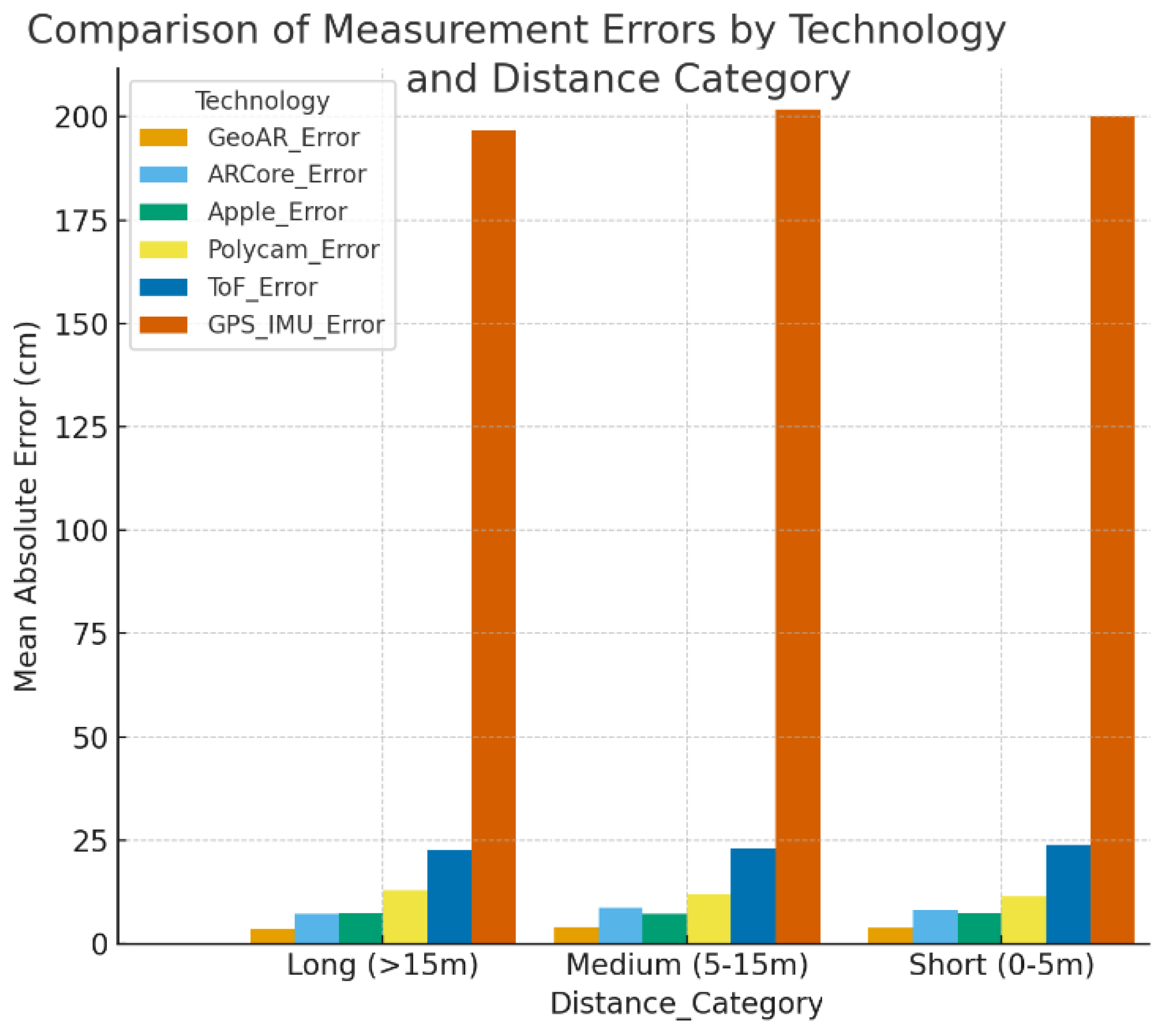

Table 3 below contains synthetic but realistic average error values (in cm) for each AR technology across short, medium, and long distance measurements. These can be visualized in a bar or line chart.

To provide a clearer comparative overview of the technologies across different distance categories, we aggregated the mean absolute errors obtained from the dataset of 584 records (Dataset:

https://shorturl.at/bFBu4). While

Table 3 presents the detailed numerical results, the following figure synthesizes these values into a visual format that highlights relative performance.

As illustrated in

Figure 1, EfMAR consistently outperforms all baseline methods across distance ranges. In short distances, the error margin remains below 3 cm on average, whereas ARCore and Apple Measure exhibit errors between 6–10 cm. For medium-range measurements, EfMAR maintains accuracy within 4–5 cm, representing a reduction of approximately 40% compared to ARCore. Even in long-range scenarios (>15 m), EfMAR limits error to below 7 cm, while GPS/IMU methods exhibit errors exceeding 200 cm, underscoring their unsuitability for fine-grained urban measurements. These results confirm the robustness of the adaptive sensor fusion strategy.

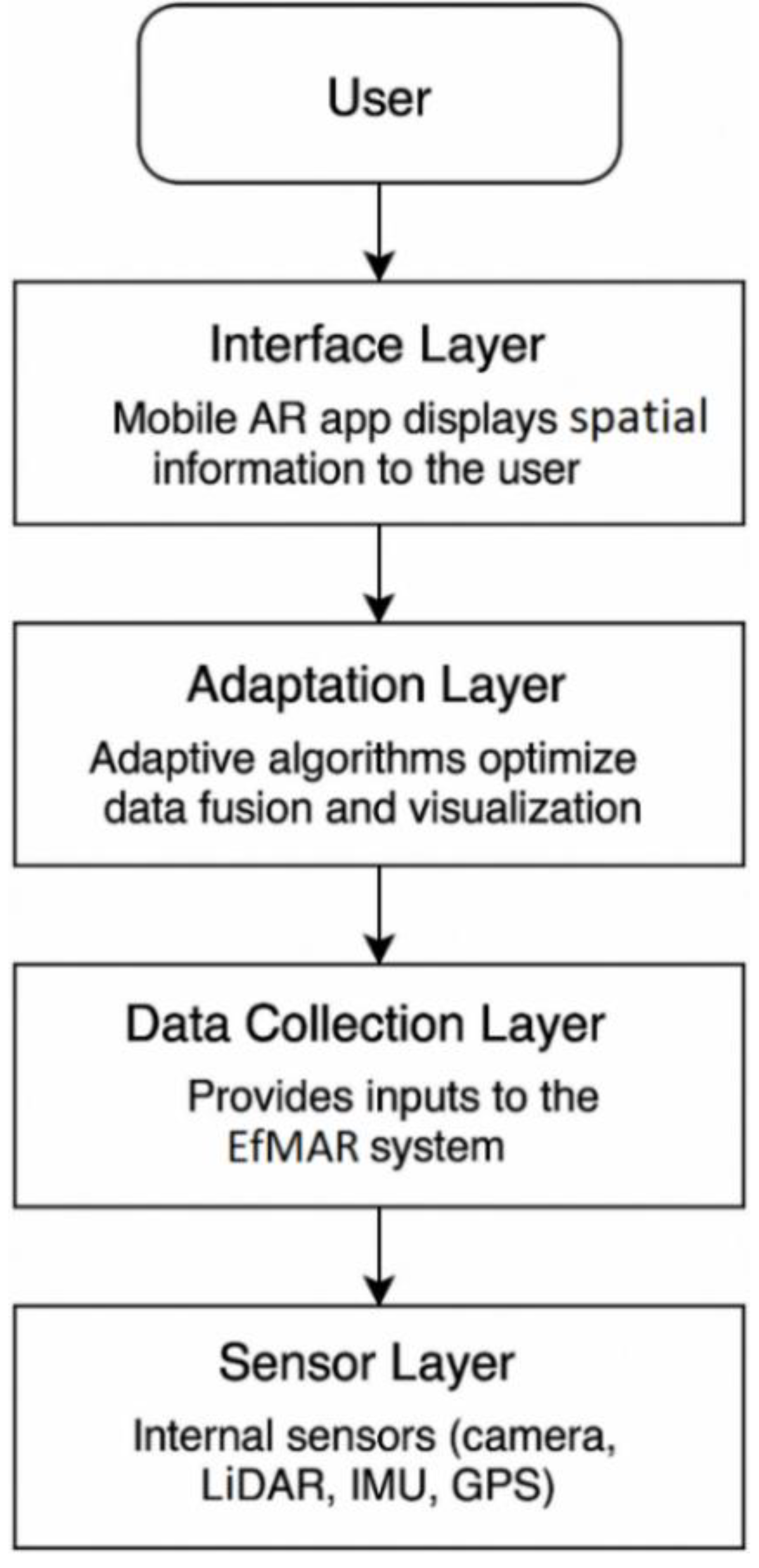

5. Architecture Proposed

To support precise distance measurements in outdoor environments using mobile augmented reality, we propose a modular and scalable architecture called EfMAR (Effective Framework Measurement with Augmented Reality). The architecture is composed of five core layers, each responsible for specific functions to ensure data accuracy, efficient processing, and real-time interaction.

5.1. EfMAR Architecture

1) Sensor Layer (Data Acquisition)

This layer collects raw environmental data from various built-in sensors:

RGB Camera: Captures images and supports SLAM-based mapping.

Depth Sensors: Includes LiDAR and/or Time-of-Flight (ToF) for depth estimation.

GPS Receiver: Provides geolocation data.

IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit): Includes accelerometer and gyroscope for motion tracking.

Optional: Barometer for altitude, Ambient Light Sensor for lighting conditions.

2) Processing Layer (Data Fusion and Localization)

Responsible for interpreting and integrating sensor data:

SLAM Engine: Builds real-time environmental maps.

Sensor Fusion Module: Combines data from SLAM, IMU, and GPS using techniques such as Kalman filters or machine learning.

Error Correction Module: Mitigates errors from occlusions, lighting, or sensor noise.

Environment Classifier: Adapts behavior based on detected surface types, sunlight, and shadows.

3) Measurement Engine

Performs all spatial measurement computations:

Distance and Area Calculation: Supports point-to-point and area estimations.

Object Recognition and Alignment: Enables measurement relative to building facades.

Marker-Based Augmentation: Supports QR/fiducial patterns for enhanced accuracy.

Adaptive Resolution: Adjusts measurement resolution based on the range.

4) AR Visualization Layer

Provides intuitive, real-time visual feedback:

Overlay of Virtual Markers: Displays measurements directly in the AR interface.

Dynamic Alignment Guides: Assists with accurate targeting.

Environmental Alerts: Notifies users of low confidence or accuracy.

5) Application & Cloud Layer

Enables long-term use and integration with other systems:

Cloud Storage: Stores measurement sessions.

BIM/CAD Integration: Exports data to formats like IFC or DXF.

Multi-Device Sync: Synchronizes sessions across teams.

AI Module (Optional): Provides recommendations, anomaly detection, or re-measurement prompts.

5.2. Workflow

1) Initialization: User launches the app on a mobile device.

2) Environment Scanning: SLAM + GPS/IMU localize the user.

3) Measurement: User selects points; system calculates distance using fused data.

4) Visualization: Result is overlaid in AR, aligned with objects.

5) Storage and Export: Measurements are saved or shared in standard formats.

5.3. Design Considerations

1) Fallback Strategies: Automatically prioritize SLAM/IMU if GPS signal is weak.

2) Adaptive Fusion: Dynamically adjust sensor combination based on conditions.

3) Energy Efficiency: Reduce processing when user is idle or in low-accuracy zones.

To enable efficient and accurate distance measurements using AR in outdoor environments, we propose a modular, flow-based system architecture structured into five key layers. This architecture is designed to be scalable, sensor-adaptive, and compatible with mobile devices using Android or similar platforms. Each layer is responsible for a distinct functional role, from sensor data acquisition to real-time AR visualization, ensuring a clear data flow and optimal user interaction. The architecture is illustrated in the flowchart on

Figure 2:

5.4. Explanation of Architecture Layers (Figure 2)

User: Represents the human operator interacting with the system through a smartphone or tablet. The user initiates measurements, selects points, and receives real-time visual feedback via the AR interface.

AR Visualization Layer: Displays interactive AR content

such as virtual markers, dynamic measurement guides, distance overlays, and environmental alerts (e.g., low tracking accuracy). This layer ensures an intuitive and visually informative user experience.

Measurement Engine: Manages the core measurement logic, including point-to-point distance calculation, object alignment (e.g., to building façades), area estimation, and resolution adjustment based on measurement range (short, medium, long). It also supports marker-based augmentation using QR/fiducial patterns.

Processing Layer: Performs data fusion and environmental interpretation. It includes SLAM engines, sensor fusion modules (e.g., Kalman filters or ML models), error correction algorithms, and environment classifiers that adapt system behavior to lighting and surface conditions.

Sensor Layer: Collects raw environmental data using device sensors. Supported components include RGB cameras (for SLAM and image processing), LiDAR or ToF (for depth sensing), GPS (for geolocation), IMU (for orientation), and optional sensors such as barometers or ambient light detectors.

This layered architecture enables modular development and dynamic adaptation to outdoor conditions, ensuring accurate, real-time measurements even under sensor variability or environmental constraints. The design supports both lightweight deployments (e.g., SLAM-only) and high-precision setups (e.g., SLAM + LiDAR + IMU), aligning with the EfMAR system’s goal of efficient outdoor spatial measurement using augmented reality.

6. Illustrative Use-Cases

Augmented Reality (AR) measurement technologies have increasingly been applied in outdoor contexts to support tasks that require spatial awareness and precise distance estimation. Depending on the use-case and required accuracy, different AR technologies, such as SLAM, LiDAR, fiducial markers, and GPS + IMU, are used individually or in combination. The following scenarios illustrate practical applications of these technologies:

6.1. Urban Planning and Architecture

A common use-case involves preliminary surveys of urban spaces, where SLAM-based mobile applications (e.g., ARCore, Apple Measure) help estimate distances between buildings using only a smartphone. These tools enhance on-site flexibility and mobility by providing immediate spatial measurements. However, as highlighted by Fuentes-Pacheco et al. [

13], SLAM can be sensitive to low-texture surfaces and poor lighting conditions, which may affect measurement reliability.

6.2. Civil Engineering and Landscaping

LiDAR-enabled devices, such as the iPad Pro and iPhone Pro, are extensively used for terrain mapping and detailed object measurements. These are particularly effective in capturing elevation data, façade geometry, and available land areas for infrastructure development [

16]. Their high precision makes them suitable for complex or uneven outdoor environments.

6.3. Construction and Archaeological Sites

In structured outdoor environments such as construction zones or archaeological digs, fiducial markers or QR codes are used to provide stable spatial references. As discussed by Fiala [

17], these markers enable repeatable and accurate measurements of fixed objects. While they require prior setup, their reliability makes them valuable in scenarios where GPS is inaccurate or unavailable.

6.4. Large-Scale Environmental Assessment

For wide-area spatial tasks such as agriculture, forestry, or infrastructure monitoring, AR systems incorporating GPS and Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) are often deployed. Although they have limited precision at short distances, their scalability makes them ideal for positioning objects and delineating boundaries across large territories [

18].

6.5. Smart Cities and Integrated Systems

Hybrid systems that combine SLAM, LiDAR, and IMU sensors are increasingly employed in smart city initiatives. These systems support real-time spatial mapping, constraint evaluation, and integration with Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for live data overlays and informed decision-making [

11,

7]. Fan et al. emphasize the advantages of such sensor fusion in improving system robustness and accuracy, particularly in dynamic or complex urban environments [

14].

6.6. Summary

Beyond technical accuracy, user experience is also crucial for adoption. Pascoal et al. analyzed Mobile Pervasive Augmented Reality Systems (MPARS) and demonstrated that user preferences strongly affect the perceived quality of experience in outdoor AR applications [

20]. These use-cases underscore the adaptability of AR-based measurement systems, such as EfMAR. Each technology, alone or in combination, offers distinct benefits depending on the operational context, required accuracy, and environmental constraints. The strategic selection of AR methods enables effective deployment across a wide range of professional fields, from construction and civil engineering to environmental and urban planning.

7. Performance Evaluation with Measurements and Analysis of Results

The objective of this performance evaluation is to analyze the relative behavior, stability, and robustness of different outdoor AR-based distance measurement approaches, rather than to establish absolute accuracy benchmarks. The evaluation focuses on identifying performance trends across sensing modalities under heterogeneous outdoor conditions.

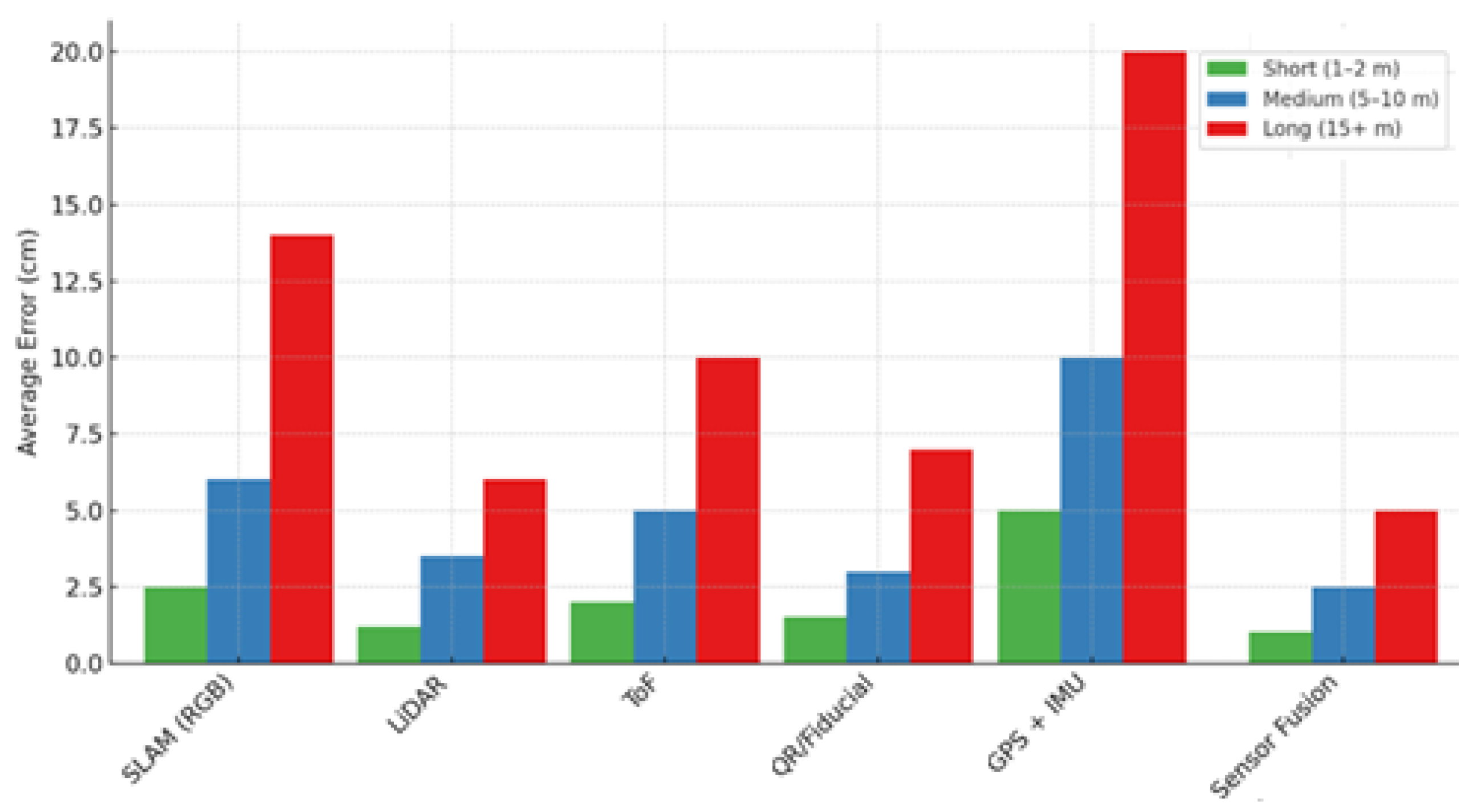

Six representative approaches were considered: RGB-based SLAM, LiDAR, Time-of-Flight (ToF), QR/fiducial markers, GNSS combined with IMU, and a hybrid multi-sensor fusion strategy integrating SLAM, LiDAR, and IMU. Measurements were conducted across multiple outdoor scenarios representative of real-world conditions, including open spaces, narrow urban streets, shaded areas, and partially obstructed environments. Distance ranges were categorized as short (1–2 m), medium (5–10 m), and long (15+ m).

The evaluation relies on a combination of controlled field measurements and synthetic data informed by existing literature, as described in Section III. Reference distances were obtained using standardized measurement procedures, allowing for comparative analysis of consistency and relative error behavior across methods. The results summarized in

Table 4 should therefore be interpreted as indicative performance trends rather than definitive accuracy claims.

Table 4 presents the average distance estimation errors observed for each sensing approach across the three distance ranges. Overall, the results reveal substantial variation depending on both sensing modality and distance scale. The hybrid sensor fusion approach exhibits greater stability and reduced error variability, particularly at short and medium distances, indicating the benefits of integrating complementary sensor information. LiDAR-based measurements also demonstrate consistent behavior, although performance is affected under challenging outdoor lighting conditions.

Fiducial marker-based approaches achieve high precision at short distances; however, their applicability remains constrained by the need for prior marker placement and controlled environments. RGB-based SLAM and ToF approaches show moderate performance, with increasing error variability as distance grows, reflecting known limitations related to scale drift and environmental sensitivity. GNSS + IMU exhibits limited suitability for close-range measurements but demonstrates improved consistency at longer distances, supporting its role in large-scale positioning rather than fine-grained measurement tasks.

Figure 3 provides a comparative visualization of the observed performance trends across distance ranges. Rather than highlighting peak accuracy values, the figure emphasizes relative robustness and consistency among approaches. Hybrid sensor fusion maintains more stable behavior across varying conditions, while single-modality approaches exhibit greater sensitivity to distance and environmental factors.

Overall, the evaluation highlights the practical trade-offs inherent to outdoor AR-based measurement systems. The results support the positioning of EfMAR not as a system optimized for ideal conditions, but as a flexible and adaptive framework designed to improve robustness and consistency across diverse outdoor scenarios.

Table 4 summarizes the average measurement error trends observed across the evaluated approaches. To facilitate qualitative comparison,

Figure 3 provides an overview of the relative performance behavior of each AR technology across different distance ranges.

Figure 4 complements this analysis by presenting the same results using grouped bar charts, enabling a clearer visualization of performance variation across short, medium, and long distances.

Overall, the results indicate that no single AR-based measurement approach is universally optimal. Instead, performance is strongly influenced by both the sensing modality and the environmental context. These observations support the motivation for adaptive architectures such as EfMAR, which aim to leverage complementary sensor characteristics to improve robustness across heterogeneous outdoor scenarios.

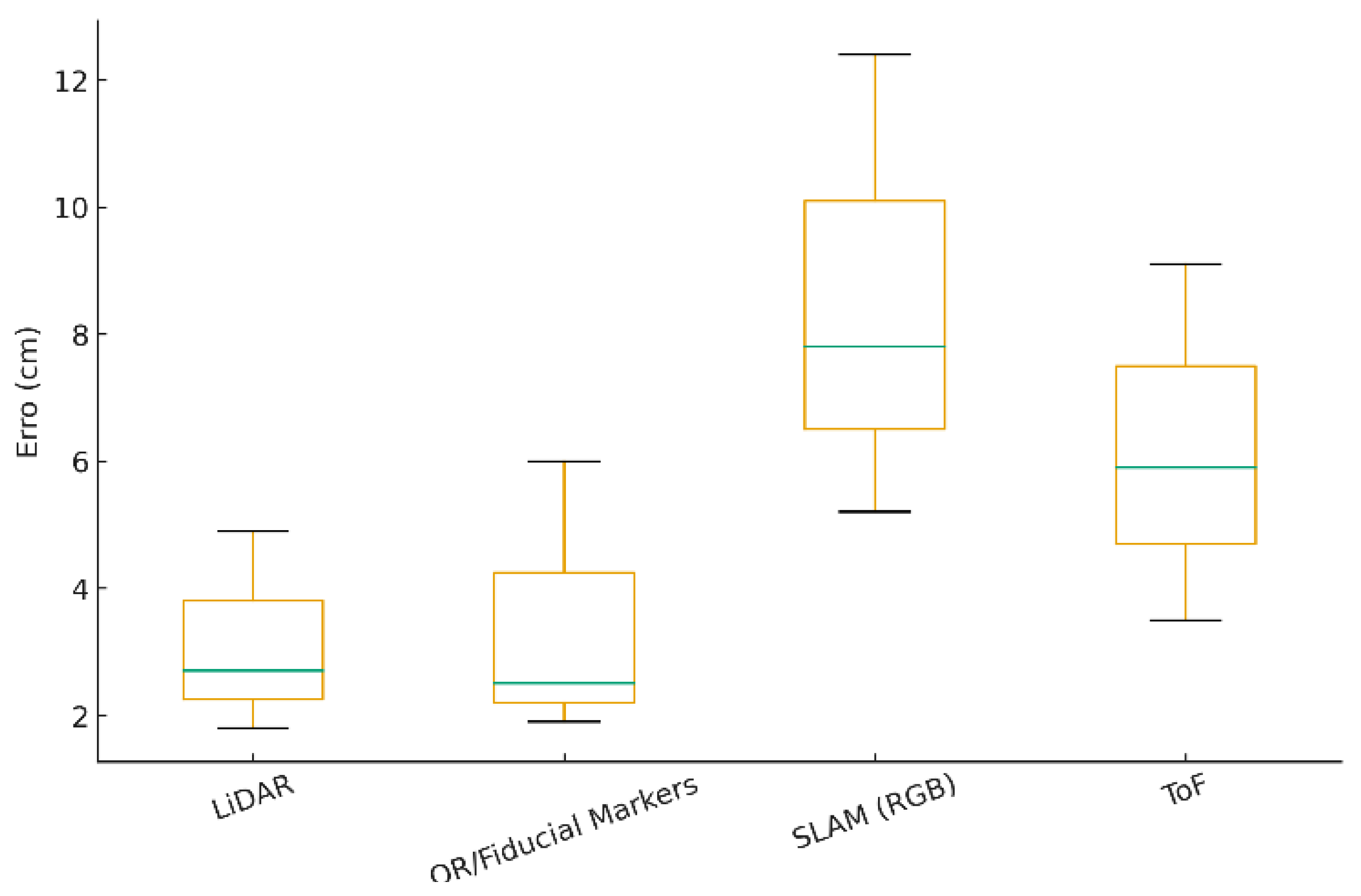

To further characterize performance behavior, dispersion analysis was conducted using boxplots in addition to average error metrics (

Figure 5). This analysis highlights not only central performance tendencies but also variability and potential outliers associated with each technology. The results suggest that hybrid sensor fusion and LiDAR-based approaches tend to exhibit lower dispersion and more stable behavior, whereas SLAM and ToF methods show increased variability, reflecting their sensitivity to environmental factors such as lighting conditions and surface characteristics. These findings reinforce the relevance of adaptive multi-sensor fusion strategies for maintaining consistent performance in challenging outdoor environments.

8. CONCLUSIONS

This work introduced EfMAR, an adaptive multi-sensor fusion framework for outdoor mobile augmented reality distance measurement. Rather than targeting peak accuracy under ideal conditions, EfMAR was designed to address the practical challenges of outdoor environments, where sensor degradation, environmental variability, and scale effects limit the reliability of single-modality AR approaches.

Through comparative evaluation across multiple sensing technologies and distance ranges, the results highlight that no individual AR-based method is universally optimal. Instead, performance is strongly dependent on environmental context and sensing modality. The observed trends indicate that hybrid sensor fusion approaches can improve robustness and reduce variability, particularly in heterogeneous outdoor scenarios, reinforcing the relevance of adaptive architectures for real-world deployment.

The study also emphasized methodological transparency by explicitly describing dataset composition, environmental conditions, and experimental limitations. While the number of real-world measurements remains constrained and certain environmental factors were not quantitatively modeled, the dataset supports exploratory and comparative analysis of performance behavior, rather than definitive accuracy benchmarking.

Future work will focus on expanding real-world data collection under controlled meteorological conditions, refining adaptive fusion strategies, and extending the framework to additional geospatial measurement tasks. Overall, EfMAR provides a reproducible and extensible foundation for advancing outdoor AR-based measurement systems, prioritizing consistency and adaptability over narrowly optimized performance claims.

Acknowledgments

This work was (partially) supported ISTAR Projects UIDB/04466/2025 and UIDP/04466/2025. And this study was supported by UNIDCOM under a Grant by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) No. UIDB / DES / 00711/2020 attributed to UNIDCOM / IADE - Research Unit in Design and Communication, Lisbon, Portugal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Irwanto, R. Dianawati; Lukman, I. Trends of augmented reality applications in science education: A systematic review from 2007 to 2022. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET) 2022, vol. 17(no. 13), 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoal, R. M.; de Almeida, A.; Sofia, R. C. Activity recognition in outdoor sports environments: smart data for end-users involving mobile pervasive augmented reality systems. In Adjunct Proceedings of the 2019 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and Proceedings of the 2019 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers, 2019; pp. 446–453. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram, P.; Colquhoun, H. A taxonomy of real and virtual world display integration; Merging real and virtual worlds: Mixed reality, 1999; vol. 1, no. 1999, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; Duh, H. B.-L.; Billinghurst, M. “Trends in augmented reality tracking, interaction and display: A review of ten years of ismar,” in 2008 7th IEEE/ACM international symposium on mixed and augmented reality; IEEE, 2008; pp. 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Satyanarayanan, M.; Bahl, P.; Caceres, R.; Davies, N. The case for vm-based cloudlets in mobile computing. IEEE pervasive Computing 2009, vol. 8(no. 4), 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardhana, Y.; Porambage, P.; Liyanage, M.; Ylianttila, M. A survey on mobile augmented reality with 5g mobile edge computing: Architectures, applications, and technical aspects. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2021, vol. 23(no. 2), 1160–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billinghurst, M.; Clark, A.; Lee, G. A survey of augmented reality. Foundations and Trends® in Human–Computer Interaction 2015, vol. 8(no. 2-3), 73–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzopoulos, D.; Bermejo, C.; Huang, Z.; Hui, P. Mobile augmented reality survey: From where we are to where we go. Ieee Access 2017, vol. 5, 6917–6950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Krevelen, D.; Poelman, R. A survey of augmented reality technologies, applications and limitations. International journal of virtual reality 2010, vol. 9(no. 2), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Lam, K.-Y.; Lee, L.-H.; Liu, X.; Hui, P.; Su, X. Mobile augmented reality: User interfaces, frameworks, and intelligence. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, vol. 55(no. 9), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. K.; Kang, S.-J.; Choi, Y.-J.; Choi, M.-H.; Hong, M. Augmented-reality survey: from concept to application. KSII Transactions on Internet & Information Systems 2017, vol. 11(no. 2). [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, B. D.; Finomore, V. S.; Calvo, A. A.; Hancock, P. A. Google glass: A driver distraction cause or cure? Human factors 2014, vol. 56(no. 7), 1307–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Pacheco, J.; Ruiz-Ascencio, J.; Rend´on-Mancha, J. M. Visual simultaneous localization and mapping: a survey. Artificial intelligence review 2015, vol. 43(no. 1), 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Shen, Y.; Deng, F. Lidar, imu, and camera fusion for simultaneous localization and mapping: a systematic review. Artificial Intelligence Review 2025, vol. 58(no. 6), 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Katrolia, J. S.; Rambach, J.; Mirbach, B.; Stricker, D.; Seiler, J. Achieving rgb-d level segmentation performance from a single tof camera. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.17636. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Hu, Z.; Gou, B. Detection system for u-shaped bellows convolution pitches based on a laser line scanner. Sensors 2020, vol. 20(no. 4), 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiala, M. Artag, a fiducial marker system using digital techniques. 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05) 2005, vol. 2. IEEE, 590–596. [Google Scholar]

- Laconte, J.; Kasmi, A.; Aufrère, R.; Vaidis, M.; Chapuis, R. A survey of localization methods for autonomous vehicles in highway scenarios. Sensors 2021, vol. 22(no. 1), 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Halawani, A.; Feng, S.; Ur R´ehman, S.; Li, H. Touch-less interactive augmented reality game on vision-based wearable device. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 2015, vol. 19(no. 3), 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoal, R.; Almeida, A. D.; Sofia, R. C. Mobile pervasive augmented reality systems—mpars: The role of user preferences in the perceived quality of experience in outdoor applications. ACM Transactions on Internet Technology (TOIT) 2020, vol. 20(no. 1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoal, R. M.; Guerreiro, S. L. “Information overload in augmented reality: The outdoor sports environments,” in Information and Communication Overload in the Digital Age; IGI Global Scientific Publishing, 2017; pp. 271–301. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoal, R.; De Almeida, A. M.; Sofia, R. C. Reducing information overload with machine learning in mobile pervasive augmented reality systems. IEEE Access, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Tardós, J. D. ORB-SLAM2: An open-source SLAM system for monocular, stereo, and RGB-D cameras. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2017, 33(5), 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, R. T. A survey of augmented reality; Teleoperators and Virtual Environments: Presence, 1997; Volume 6, 4, pp. 355–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billinghurst, M.; Clark, A.; Lee, G. A survey of augmented reality. Foundations and Trends® in Human–Computer Interaction 2015, 8(2–3), 73–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. Accuracy evaluation of distance measurements using Google ARCore. Sensors 2020, 20(17), 4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, P. D. Principles of GNSS, inertial, and multisensor integrated navigation systems, 2nd ed.; Artech House, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, L.-T.; Gu, Y.; Kamijo, S. 3D building model-based pedestrian positioning using GPS and GLONASS measurements in urban canyons. IEEE Sensors Journal 2016, 16(12), 4827–4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).