Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

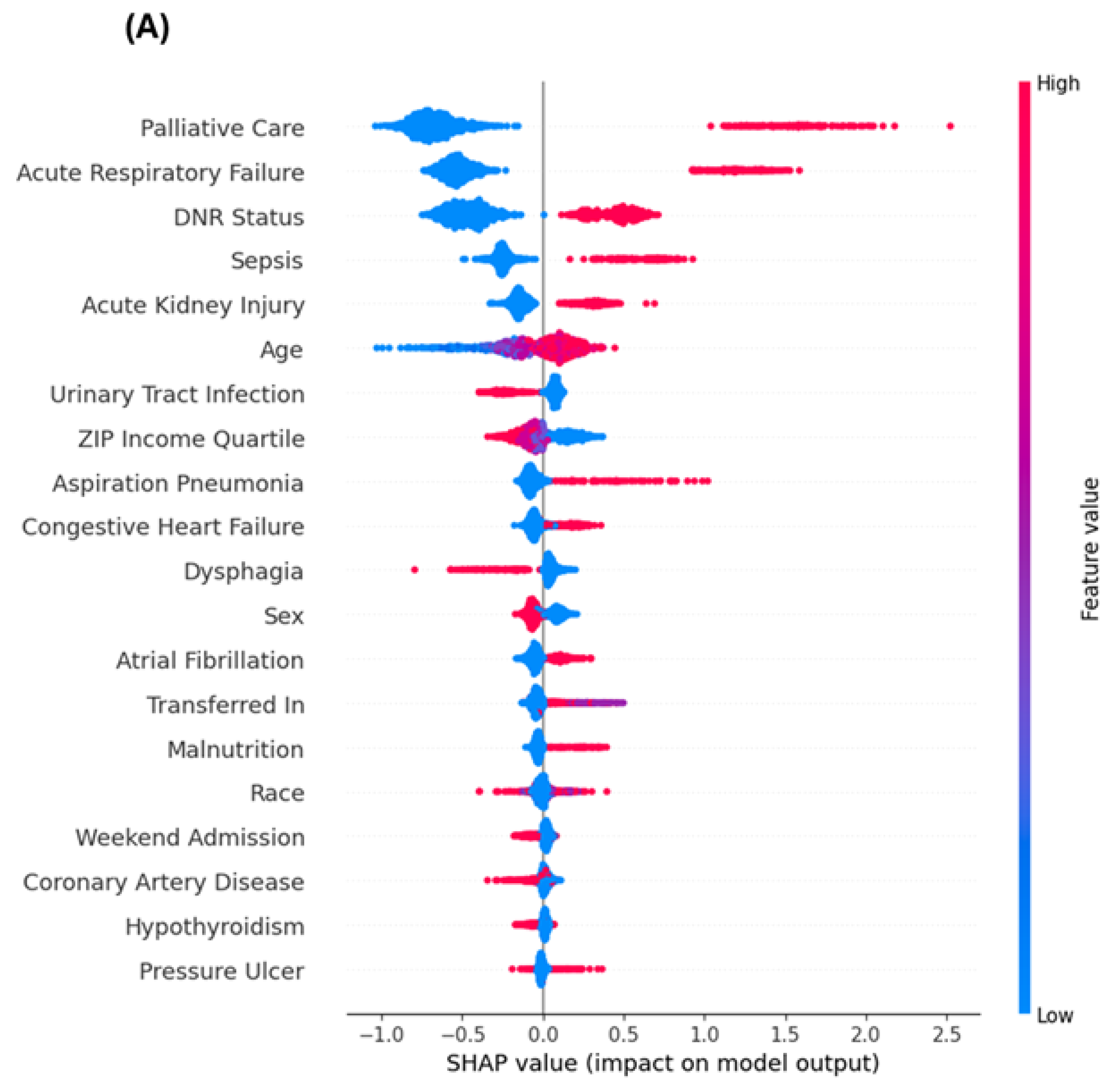

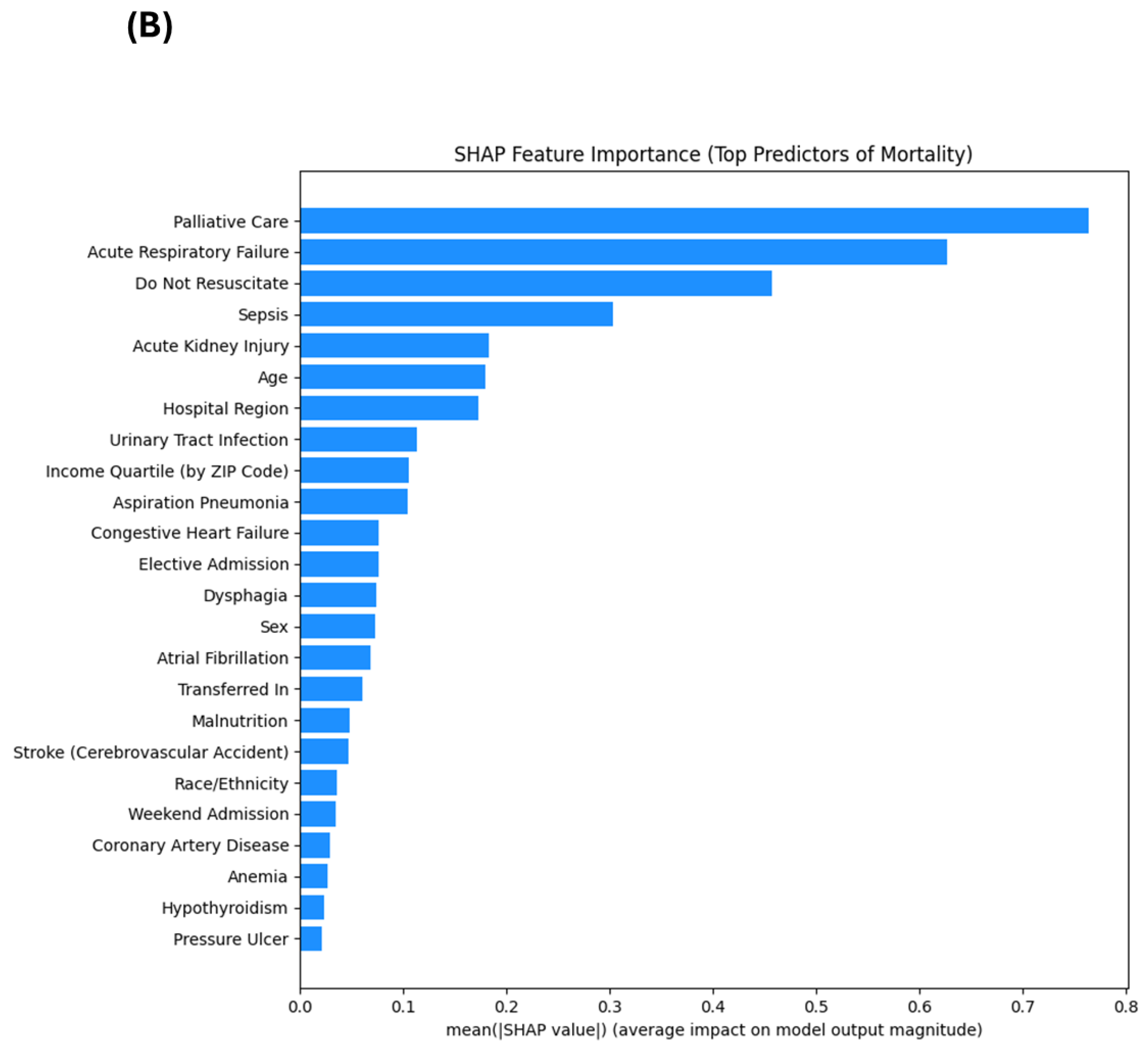

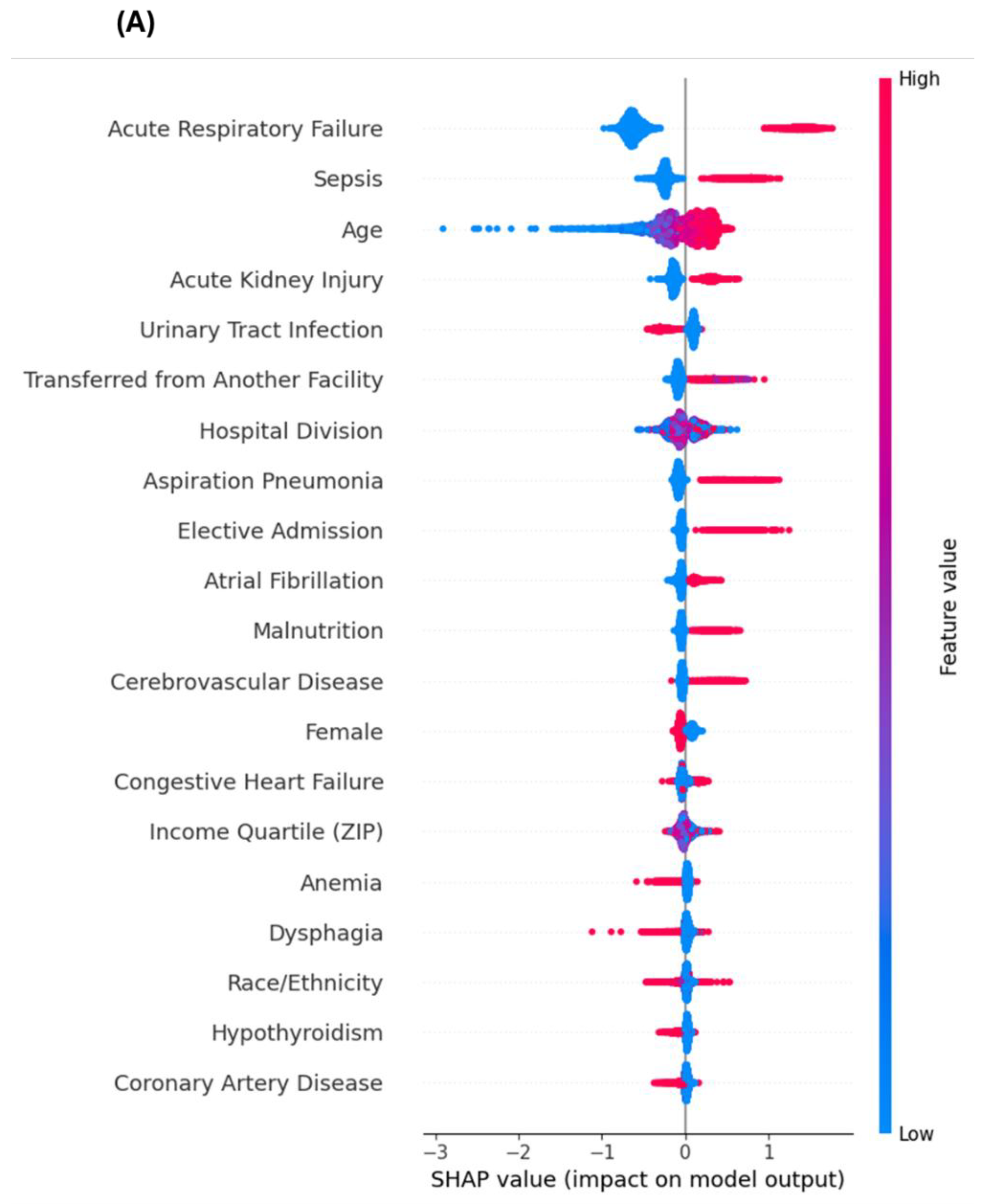

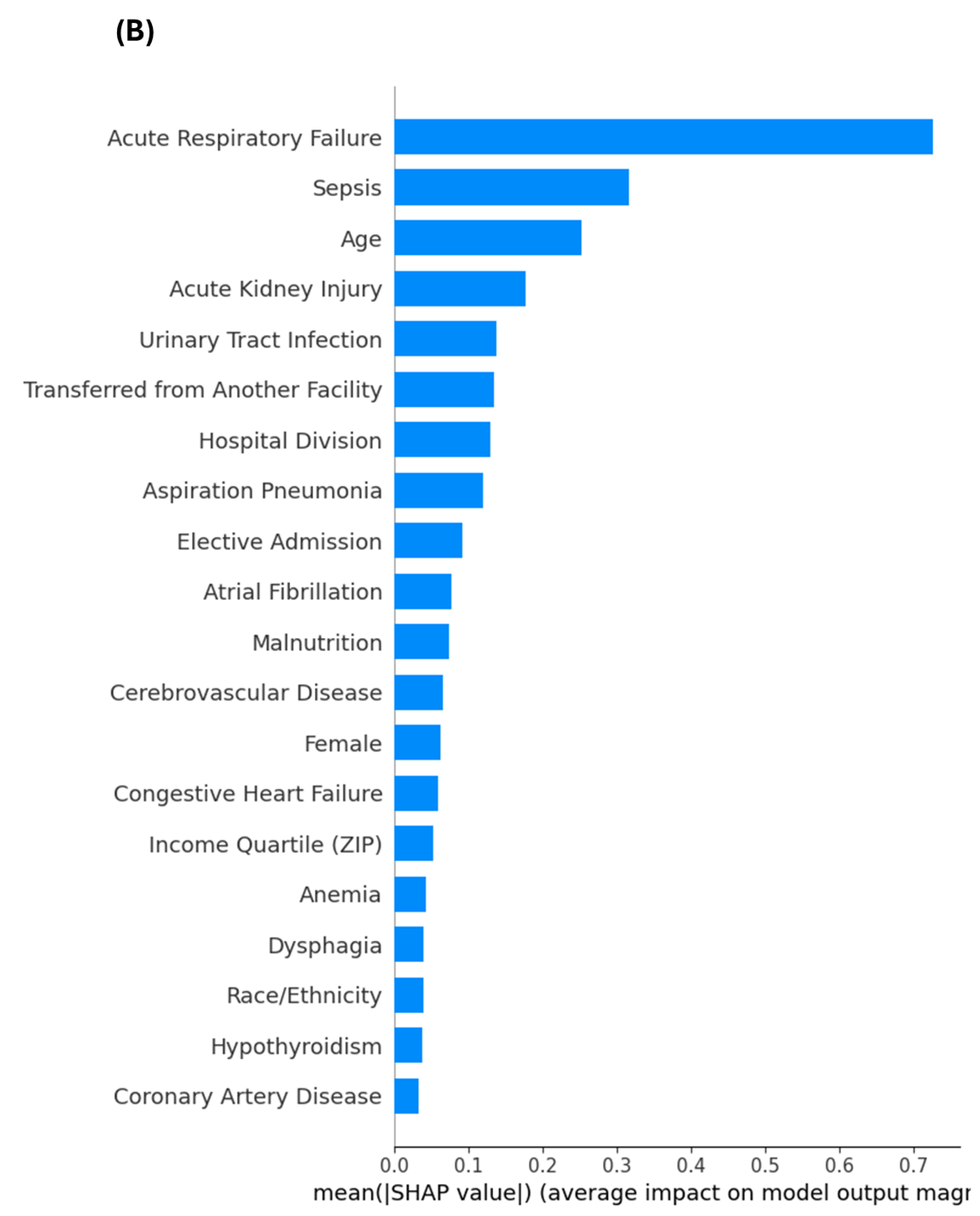

Background: Older adults with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) face heightened risk of adverse hospital outcomes, including mortality. However, early identification of high-risk patients remains a challenge. While regression models provide interpretable associations, they may miss nonlinear interactions that machine learning can uncover. Objective: To identify key predictors of in-hospital mortality among AD patients using both survey-weighted logistic regression and explainable machine learning. Methods: We analyzed hospitalizations among AD patients aged ≥60 in the 2017 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). The outcome was in-hospital death. Predictors included demographics, hospital variables, and 15 comorbidities. Logistic regression used survey weighting to generate nationally representative inference; XGBoost incorporated NIS discharge weights as sample weights during 5-fold hospital-grouped cross-validation and used the same weights in performance evaluation. Missing-value imputation and feature scaling were performed within the cross-validation pipelines to prevent data leakage. Model performance was assessed using AUROC, AUPRC, Brier score, and log loss. Feature importance was assessed using adjusted odds ratios and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP). A sensitivity analysis excluded palliative care and DNR status and was re-evaluated under the same grouped cross-validation. Results: In the full model, logistic regression achieved AUROC 0.879 and AUPRC 0.310, while XGBoost achieved AUROC 0.887 and AUPRC 0.324. Palliative care (aOR 6.19), acute respiratory failure (aOR 5.15), DNR status (aOR 2.20), and sepsis (aOR 2.26) were the strongest logistic predictors. SHAP analysis corroborated these findings and additionally emphasized dysphagia, malnutrition, and pressure ulcers. In sensitivity analysis excluding palliative care and DNR status, logistic regression performance declined (AUROC 0.806; AUPRC 0.206), while XGBoost performed similarly (AUROC 0.811; AUPRC 0.206). SHAP corroborated the dominant signals from end-of-life documentation and acute organ failure in the full model; in the restricted model (excluding DNR and palliative care), SHAP highlighted physiologic and frailty-related features (e.g., dysphagia, malnutrition, aspiration risk) that may be more actionable when end-of-life documentation is absent. Conclusion: Combining regression with explainable machine learning enables robust mortality risk stratification in hospitalized AD patients. Restricted models excluding end-of-life indicators provide actionable risk signals when such documentation is absent, while the full model may better support resource allocation and goals-of-care workflows.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

2.2. Identification of Predictors and Variable Construction

2.3. Covariates and Feature Engineering

2.4. Descriptive Statistics and Logistic Regression Analysis

2.5. Machine Learning Modeling and Performance Evaluation

2.6. Sensitivity Analysis

2.7. Model Explainability Using SHAP Values

2.8. Software and Reproducibility

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Risk Factors Identified via Logistic Regression

3.3. Model Performance Metrics

3.4. Top Predictors: SHAP vs. Regression

3.5. Explainable Machine Learning Interpretation

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis Excluding End-of-Life Predictors

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Mortality Predictors: Traditional and Novel Contributors

4.2. Concordance and Divergence Between Modeling Approaches

4.3. Insights from Sensitivity Analyses

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

4.5. Clinical and Policy Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| AKI | acute kidney injury |

| aOR | adjusted odds ratio |

| AUPRC | area under the precision–recall curve |

| AUROC | area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| ARF | acute respiratory failure |

| DNR | do-not-resuscitate |

| HCUP | Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project |

| ICD-10-CM | International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification |

| NIS | Nationwide Inpatient Sample |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Alzheimer's-Association. 2024 Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer's & Dementia 2024, 20(no. 5), 3708–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, E. A., S. Borson, L. Grothaus, S. Balch, and E. B. Larson. Association of Incident Dementia with Hospitalizations. Jama 2012, 307(no. 2), 165–72. [CrossRef]

- Beydoun, May A., Hind A. Beydoun, Alyssa A. Gamaldo, Ola S. Rostant, Greg A. Dore, Alan B. Zonderman, and Shaker M. Eid. Nationwide Inpatient Prevalence, Predictors, and Outcomes of Alzheimer’s Disease among Older Adults in the United States, 2002–2012. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2015, 48(no. 2), 361–75. [CrossRef]

- De Matteis, G., M. L. Burzo, D. A. Della Polla, A. Serra, A. Russo, F. Landi, A. Gasbarrini, G. Gambassi, F. Franceschi, and M. Covino. Outcomes and Predictors of in-Hospital Mortality among Older Patients with Dementia. J Clin Med 2022, 12(no. 1). [CrossRef]

- Silva, T. J., C. S. Jerussalmy, J. M. Farfel, J. A. Curiati, and W. Jacob-Filho. Predictors of in-Hospital Mortality among Older Patients. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2009, 64(no. 7), 613–8. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Zhangmin, Linan Cheng, Xiuying Hu, and Qian Chen. Risk Factors for in-Hospital Death in Elderly Patients over 65 Years of Age with Dementia: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. Medicine 2022, 101(no. 26), e29737. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerschbaum, Maximilian, Lisa Klute, Leopold Henssler, Markus Rupp, Volker Alt, and Siegmund Lang. "Risk Factors for in-Hospital Mortality in Geriatric Patients Aged 80 and Older with Axis Fractures: A nationwide, cross-Sectional Analysis of Concomitant Injuries, Comorbidities, and Treatment Strategies in 10,077 Cases.". European Spine Journal 2024, 33(no. 1), 185–97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, Mary E., Peter Pompei, Kathy L. Ales, and C. Ronald MacKenzie. "A New Method of Classifying Prognostic Comorbidity in Longitudinal Studies: Development and Validation.". Journal of Chronic Diseases 1987, 40(no. 5), 373–83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, Hilary, Gill Livingston, Justin Chan, and Andrew Sommerlad. "Hospitalisation Rates and Predictors in People with Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.". BMC Medicine 2019, 17(no. 1), 130. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y., H. S. Chung, J. Y. Lim, K. Kim, Y. H. Choi, D. H. Lee, and S. J. Bae. "Prognostic Value of Frailty across Age Groups in Emergency Department Patients Aged 65 and Above.". BMC Geriatr 2025, 25(no. 1), 445. [CrossRef]

- Verdon, Mélanie, Thomas Agoritsas, Cécile Jaques, Sophie Pouzols, and Cédric Mabire. "Factors Involved in the Development of Hospital-Acquired Conditions in Older Patients in Acute Care Settings: A Scoping Review.". BMC Health Services Research 2025, 25(no. 1), 174. [CrossRef]

- Barredo Arrieta, Alejandro, Natalia Díaz-Rodríguez, Javier Del Ser, Adrien Bennetot, Siham Tabik, Alberto Barbado, Salvador Garcia, Sergio Gil-Lopez, Daniel Molina, Richard Benjamins, Raja Chatila, and Francisco Herrera. "Explainable Artificial Intelligence (Xai): Concepts, Taxonomies, Opportunities and Challenges toward Responsible Ai.". Information Fusion 2020, 58, 82–115. [CrossRef]

- Stiglic, Gregor, Primoz Kocbek, Nino Fijacko, Marinka Zitnik, Katrien Verbert, and Leona Cilar. "Interpretability of Machine Learning-Based Prediction Models in Healthcare.". WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2020, 10(no. 5), e1379. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, Scott M., and Su-In Lee. "A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions." Paper presented at the Neural Information Processing Systems 2017.

- Chen, Tianqi, and Carlos Guestrin. "Xgboost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System." In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 785–94. San Francisco, California, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2016.

- Lundberg, S. M., G. Erion, H. Chen, A. DeGrave, J. M. Prutkin, B. Nair, R. Katz, J. Himmelfarb, N. Bansal, and S. I. Lee. "From Local Explanations to Global Understanding with Explainable Ai for Trees.". Nat Mach Intell 2020, 2(no. 1), 56–67. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M. J., S. Song, A. M. Kurasz, and Z. Li. "Predictors of Mortality in Individuals with Dementia in the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center." J Alzheimers Dis 86, no. 4 (2022): 1935-46. [CrossRef]

- González, P. T. M., L. M. Vieira, A. P. Y. Sarmiento, J. S. Ríos, M. A. S. Alarcón, and M. A. O. Guerrero. "Predictors of Mortality in Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis." Neurology Perspectives 4, no. 4 (2024): 100175. [CrossRef]

- Beam, Andrew L., and Isaac S. Kohane. "Big Data and Machine Learning in Health Care.". Jama 2018, 319(no. 13), 1317–18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou, Evangelia, Jie Ma, Gary S. Collins, Ewout W. Steyerberg, Jan Y. Verbakel, and Ben Van Calster. "A Systematic Review Shows No Performance Benefit of Machine Learning over Logistic Regression for Clinical Prediction Models.". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2019, 110, 12–22. [CrossRef]

- Rajkomar, Alvin, Jeffrey Dean, and Isaac Kohane. "Machine Learning in Medicine.". New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 380(no. 14), 1347–58. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkam, Tursun, Ebrahim Tarshizi, and Andrew H Van Benschoten. "Red-Flagging Multimorbidity Clusters for Alzheimer's Disease Risk Using Explainable Machine Learning: Evidence from a National Emergency Department Sample.". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease Reports 2025, 9, 25424823251392474. [CrossRef]

- Räz, T., A. Pahud De Mortanges, and M. Reyes. "Explainable Ai in Medicine: Challenges of Integrating Xai into the Future Clinical Routine.". Front Radiol 2025, 5, 1627169. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacobbe, D. R., Y. Zhang, and J. de la Fuente. "Explainable Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: Novel Approaches to Face Infectious Diseases Challenges.". Ann Med 2023, 55(no. 2), 2286336. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, Zahra, Roohallah Alizadehsani, Mehmet Akif Cifci, Samina Kausar, Rizwan Rehman, Priyakshi Mahanta, Pranjal Kumar Bora, Ammar Almasri, Rami S. Alkhawaldeh, Sadiq Hussain, Bilal Alatas, Afshin Shoeibi, Hossein Moosaei, Milan Hladík, Saeid Nahavandi, and Panos M. Pardalos. "A Review of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare.". Computers and Electrical Engineering 2024, 118, 109370. [CrossRef]

- Mienye, Ibomoiye Domor, George Obaido, Nobert Jere, Ebikella Mienye, Kehinde Aruleba, Ikiomoye Douglas Emmanuel, and Blessing Ogbuokiri. "A Survey of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Concepts, Applications, and Challenges.". Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 2024, 51, 101587. [CrossRef]

- Topol, Eric J. "High-Performance Medicine: The Convergence of Human and Artificial Intelligence.". Nature Medicine 2019, 25(no. 1), 44–56. [CrossRef]

- Khwaja, A. "Kdigo Clinical Practice Guidelines for Acute Kidney Injury.". Nephron Clin Pract 2012, 120(no. 4), c179–84. [CrossRef]

- Stefan, Mihaela S., Meng-Shiou Shieh, Penelope S. Pekow, Michael B. Rothberg, Jay S. Steingrub, Tara Lagu, and Peter K. Lindenauer. "Epidemiology and Outcomes of Acute Respiratory Failure in the United States, 2001 to 2009: A National Survey.". Journal of Hospital Medicine 2013, 8(no. 2), 76–82. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, Mervyn, Clifford S. Deutschman, Christopher Warren Seymour, Manu Shankar-Hari, Djillali Annane, Michael Bauer, Rinaldo Bellomo, Gordon R. Bernard, Jean-Daniel Chiche, Craig M. Coopersmith, Richard S. Hotchkiss, Mitchell M. Levy, John C. Marshall, Greg S. Martin, Steven M. Opal, Gordon D. Rubenfeld, Tom van der Poll, Jean-Louis Vincent, and Derek C. Angus. "The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3).". Jama 2016, 315(no. 8), 801–10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostev, K., B. Michalowsky, and J. Bohlken. "In-Hospital Mortality in Patients with and without Dementia across Age Groups, Clinical Departments, and Primary Admission Diagnoses.". Brain Sci 2024, 14(no. 5). [CrossRef]

- Walkey, A. J., J. Weinberg, R. S. Wiener, C. R. Cooke, and P. K. Lindenauer. "Association of Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders and Hospital Mortality Rate among Patients with Pneumonia.". JAMA Intern Med 2016, 176(no. 1), 97–104. [CrossRef]

- Behl, Tapan, Ishnoor Kaur, Aayush Sehgal, Sukhbir Singh, Ali Albarrati, Mohammed Albratty, Asim Najmi, Abdulkarim M. Meraya, and Simona Bungau. "The Road to Precision Medicine: Eliminating the “One Size Fits All” Approach in Alzheimer’s Disease.". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 153, 113337. [CrossRef]

- Butler, L. M., R. Houghton, A. Abraham, M. Vassilaki, and G. Durán-Pacheco. "Comorbidity Trajectories Associated with Alzheimer's Disease: A Matched Case-Control Study in a United States Claims Database.". Front Neurosci 2021, 15, 749305. [CrossRef]

- Stirland, L. E., R. Choate, P. P. Zanwar, P. Zhang, T. J. Watermeyer, M. Valletta, M. Torso, S. Tamburin, U. Saeed, G. R. Ridgway, S. Moukaled, J. B. Lusk, S. M. Loi, T. J. Littlejohns, E. Kuźma, S. N. James, G. Grande, I. F. Foote, K. A. Q. Cousins, J. Butler, A. AbuHamdia, T. J. Avelino-Silva, and V. Suryadevara. "Multimorbidity in Dementia: Current Perspectives and Future Challenges.". Alzheimers Dement 2025, 21(no. 8), e70546. [CrossRef]

- Steyerberg, Ewout W., and Frank E. Harrell, Jr. "Prediction Models Need Appropriate Internal, Internal–External, and External Validation.". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2016, 69, 245–47. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagiakrishnan, K., R. A. Bhanji, and M. Kurian. "Evaluation and Management of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Different Types of Dementia: A Systematic Review.". Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2013, 56(no. 1), 1–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalia, M. "Dysphagia and Aspiration Pneumonia in Patients with Alzheimer's Disease.". Metabolism 2003, 52(no. 10) Suppl 2, 36–8. [CrossRef]

- itchell, Susan L., Joan M. Teno, Dan K. Kiely, Michele L. Shaffer, Richard N. Jones, Holly G. Prigerson, Ladislav Volicer, Jane L. Givens, and Mary Beth Hamel. "The Clinical Course of Advanced Dementia.". New England Journal of Medicine 2009, 361(no. 16), 1529–38. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S., F. Akhlaq, A. S. Imran, Z. Kastrati, S. M. Daudpota, and M. Moosa. "The Enlightening Role of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Medical & Healthcare Domains: A Systematic Literature Review.". Comput Biol Med 2023, 166, 107555.

- Song, Y. P., H. W. Shen, J. Y. Cai, M. L. Zha, and H. L. Chen. "The Relationship between Pressure Injury Complication and Mortality Risk of Older Patients in Follow-Up: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.". Int Wound J 2019, 16(no. 6), 1533–44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Level | Weighted % or Mean (SE) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | Mean (SE) | 82.40 (0.04) | 82.33-82.47 |

| Sex | Male | 38.3 | 37.9-38.6 |

| Female | 61.7 | 61.4-62.1 | |

| Admission type | Non-elective | 92.4 | 91.9-92.8 |

| Elective | 7.6 | 7.2-8.1 | |

| Weekend admission | No | 75.8 | 75.5-76.1 |

| Yes | 24.2 | 23.9-24.5 | |

| In-hospital mortality | Died | 4.7 | 4.5-4.8 |

| Sepsis | Yes | 15.7 | 15.4-16.1 |

| Acute respiratory failure (ARF) | Yes | 14.2 | 13.9-14.5 |

| Acute kidney injury (AKI) | Yes | 23.2 | 22.8-23.6 |

| Aspiration | Yes | 7.9 | 7.7-8.2 |

| Urinary tract infection (UTI) | Yes | 25.4 | 25.0-25.8 |

| Malnutrition | Yes | 8.2 | 7.9-8.5 |

| Dysphagia | Yes | 10.7 | 10.4-11.0 |

| Pressure ulcer | Yes | 7.2 | 6.9-7.4 |

| Congestive heart failure (CHF) | Yes | 23.0 | 22.7-23.4 |

| Coronary artery disease (CAD) | Yes | 25.7 | 25.3-26.1 |

| Atrial fibrillation (AFib) | Yes | 25.6 | 25.3-26.0 |

| Cerebrovascular disease (CVA) | Yes | 7.5 | 7.3-7.7 |

| Anemia | Yes | 12.7 | 12.4-13.0 |

| Hypothyroidism | Yes | 21.7 | 21.4-22.1 |

| Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) order | Yes | 32.1 | 31.4-32.7 |

| Palliative care | Yes | 11.3 | 10.9-11.6 |

| Race | White | 73.9 | 72.8-75.0 |

| Black | 11.6 | 11.0-12.2 | |

| Hispanic | 9.3 | 8.4-10.2 | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 2.4 | 2.1-2.8 | |

| Native American | 0.3 | 0.22-0.37 | |

| Other | 2.5 | 2.17-2.83 | |

| ZIP income quartile | 0-25th percentile (lowest income) | 28.9 | 27.8-30.0 |

| 26th-50th percentile | 26.2 | 25.4-27.1 | |

| 51st-75th percentile | 23.6 | 22.8-24.4 | |

| 76th-100th percentile (highest income) | 21.3 | 20.2-22.4 | |

| Transfer-in (TRAN_IN) | Not transferred in | 82.5 | 81.7-83.2 |

| Transferred in from a different acute care hospital | 5.1 | 4.8-5.5 | |

| Transferred in from another type of health facility | 12.4 | 11.8-13.1 | |

| Hospital division | New England | 4.8 | 4.3-5.4 |

| Middle Atlantic | 13.5 | 12.7-14.4 | |

| East North Central | 16.5 | 15.5-17.5 | |

| West North Central | 6.8 | 6.2-7.5 | |

| South Atlantic | 20.9 | 20.0-22.0 | |

| East South Central | 7.9 | 7.1-8.7 | |

| West South Central | 12.5 | 11.8-13.3 | |

| Mountain | 4.1 | 3.8-4.5 | |

| Pacific | 12.9 | 12.1-13.7 |

| Covariate | Category (ref) | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | continuous | 1.017 | 1.011-1.023 | <0.001 |

| Female | vs Male | 0.858 | 0.794-0.926 | <0.001 |

| Race (ref = White) | Black | 1.050 | 0.924-1.193 | 0.455 |

| Hispanic | 1.174 | 1.024-1.347 | 0.021 | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1.079 | 0.866-1.344 | 0.497 | |

| Native American | 0.723 | 0.287-1.820 | 0.491 | |

| Other | 1.151 | 0.909-1.458 | 0.242 | |

|

ZIP income quartile (ref = 0-25th percentile (lowest income)) |

26th-50th percentile | 0.849 | 0.762-0.946 | 0.003 |

| 51st-75th percentile | 0.799 | 0.710-0.899 | <0.001 | |

| 76th-100th percentile (highest income) |

0.798 | 0.706-0.903 | <0.001 | |

| Elective admission | vs Non-elective | 2.334 | 1.961-2.777 | <0.001 |

|

Transfer-in (ref = Not transferred in) |

Transferred in from a different acute care hospital | 1.562 | 1.322-1.844 | <0.001 |

| Transferred in from another type of health facility | 1.124 | 1.004-1.257 | 0.042 | |

| Weekend admission | vs Weekday | 0.944 | 0.867-1.028 | 0.186 |

|

Hospital division (ref = New England) |

Middle Atlantic | 1.108 | 0.870-1.409 | 0.406 |

| East North Central | 0.615 | 0.484-0.782 | <0.001 | |

| West North Central | 0.757 | 0.580-0.989 | 0.041 | |

| South Atlantic | 0.701 | 0.557-0.883 | 0.003 | |

| East South Central | 1.064 | 0.793-1.427 | 0.680 | |

| West South Central | 0.788 | 0.618-1.007 | 0.056 | |

| Mountain | 0.569 | 0.421-0.769 | <0.001 | |

| Pacific | 0.973 | 0.775-1.223 | 0.817 | |

| Sepsis | Yes vs No | 2.260 | 2.074-2.462 | <0.001 |

| Acute respiratory failure | Yes vs No | 5.148 | 4.730-5.602 | <0.001 |

| Acute kidney injury | Yes vs No | 1.466 | 1.349-1.592 | <0.001 |

| Aspiration | Yes vs No | 1.228 | 1.101-1.368 | <0.001 |

| Urinary tract infection | Yes vs No | 0.737 | 0.673-0.807 | <0.001 |

| Malnutrition | Yes vs No | 1.235 | 1.106-1.378 | <0.001 |

| Dysphagia | Yes vs No | 0.569 | 0.506-0.640 | <0.001 |

| Pressure ulcer | Yes vs No | 1.033 | 0.908-1.176 | 0.618 |

| Congestive heart failure | Yes vs No | 1.074 | 0.981-1.175 | 0.124 |

| Coronary artery disease | Yes vs No | 0.943 | 0.868-1.024 | 0.164 |

| Atrial fibrillation | Yes vs No | 1.191 | 1.094-1.297 | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | Yes vs No | 1.382 | 1.214-1.573 | <0.001 |

| Anemia | Yes vs No | 0.878 | 0.788-0.978 | 0.018 |

| Hypothyroidism | Yes vs No | 0.941 | 0.860-1.031 | 0.192 |

| Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) order | Yes vs No | 2.198 | 1.994-2.423 | <0.001 |

| Palliative care | Yes vs No | 6.189 | 5.589-6.853 | <0.001 |

| Model | Dataset Type | AUROC | AUPRC | Brier Score | Log Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | Full Model | 0.8866 | 0.3238 | 0.0364 | 0.1337 |

| Logistic Regression | Full Model | 0.8789 | 0.3103 | 0.0372 | 0.1375 |

| XGBoost | Sensitivity (No DNR / Pall) |

0.8106 | 0.2061 | 0.0403 | 0.1563 |

| Logistic Regression | Sensitivity (No DNR / Pall) |

0.8059 | 0.2056 | 0.0403 | 0.1569 |

| Rank | Predictor | Logistic Coefficient | XGBoost Gain |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Palliative Care | 4.554 | 14.703 |

| 2 | Acute Respiratory Failure | 2.466 | 11.423 |

| 3 | Acute Kidney Injury | 1.437 | 4.545 |

| 4 | Dysphagia | -1.301 | 4.358 |

| 5 | Age | 1.273 | 4.909 |

| 6 | Aspiration Pneumonia | 0.950 | 4.257 |

| 7 | Urinary Tract Infection | -0.842 | 3.697 |

| 8 | Elective Admission | -0.734 | 1.059 |

| 9 | Pressure Ulcers | -0.724 | 3.320 |

| 10 | Stroke | -0.672 | 3.023 |

| 11 | Sepsis | 0.663 | 3.777 |

| 12 | Anemia | 0.637 | 2.765 |

| 13 | Congestive Heart Failure | 0.535 | 2.711 |

| 14 | Malnutrition | 0.326 | 3.579 |

| 15 | Coronary Artery Disease | 0.290 | 3.343 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.