1. Introduction

Circular economy (CE) has emerged as a prominent framework within global sustainability and urban policy agendas, promoted as a response to the environmental and resource inefficiencies of linear economic systems [

1,

2,

3]. By highlighting material circularity, waste valorization, and resource efficiency, CE is often positioned as a strategy capable of reconciling economic growth with environmental sustainability [

4]. However, a growing body of critical scholarship cautions that CE is neither a neutral nor inherently transformative model; rather, it is a contested socio-spatial project shaped by political economy, governance structures, and territorial inequalities [

5,

6,

7].

Urban Studies scholarship is increasingly acknowledging cities and metropolitan regions as central arenas where CE strategies are articulated, negotiated, and implemented [

8,

9]. However, rather than unfolding as a purely technical transition, circularity is embedded in urban governance arrangements, industrial legacies, labor markets, and spatial power relations [

10,

11]. From this perspective, CE must be understood as a place-based and scalar process, shaped by metropolitan political economies and institutional capacities rather than existing as a universally transferable policy solution.

These dynamics are particularly pronounced in arid metropolitan regions, where environmental constraints intersect with rapid urbanization and industrial concentration. Arid regions are characterized by water scarcity, high energy intensity, and mounting waste management pressures—conditions that intensify the unsustainability of linear production and consumption systems [

12]. Simultaneously, several arid metropolitan regions function as strategic industrial and logistics hubs integrated into global value chains, thus amplifying material throughput and environmental stress [

13,

14]. However, despite the urgency of circular transitions in such contexts, empirical research on CE implementation in arid metropolitan regions remains limited, particularly from an urban political-economy perspective.

In the CE literature, the private sector is widely recognized as playing a key role in operationalizing circular practices [

15,

16]. However, urban studies scholars stress the importance of differentiating between firm types, scales of operation, and degrees of spatial embeddedness. Notably, micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) are foundational in metropolitan economies, accounting for a substantial share of employment, service provision, and localized innovation [

17]. Their close integration into urban production networks positions MSMEs as potentially critical agents of circular transformation, especially in activities such as waste reduction, recycling, repair, and resource-efficient production [

18]. Yet, empirical evidence consistently demonstrates that MSMEs face structural disadvantages in adopting CE practices. For instance, limited access to finance, regulatory complexity, fragmented policy support, and insufficient technical capacity constrain MSME participation in circular initiatives [

19,

20]. Critical scholars even argue that dominant CE narratives often privilege capital-intensive solutions and large corporate actors, thereby marginalizing smaller firms and informal economic activities central to urban sustainability in various regions [

21,

22]. From an urban studies perspective, this raises fundamental questions regarding who benefits from CE transitions and whether CE policies reproduce existing metropolitan inequalities.

Recent urban research underscores the scalar politics of CE implementation. While CE strategies are frequently articulated at national or metropolitan scales, their realization depends on firm-level decisions and localized governance arrangements [

7,

23,

24]. This scalar mismatch can generate implementation gaps, particularly for MSMEs operating in peripheral industrial zones or fragmented urban regions. Without effective institutional mediation, CE initiatives risk remaining symbolic policy instruments rather than producing substantive transformations in urban production systems [

25,

26].

In arid metropolitan regions, the aforementioned challenges are often intensified by state-led development models and infrastructure-driven urban growth. Although such regions frequently exhibit strong policy ambition and strategic planning capacity, the task of translating CE visions into inclusive and actionable outcomes at the MSME level remains uneven [

27,

28]. Furthermore, studies of circular transitions in the Gulf and comparable arid regions point to persistent barriers related to regulatory fragmentation, limited private sector coordination, and uneven institutional support [

13,

14,

29]. These findings underscore the need for empirically grounded analyses that examine how CE policies are experienced and enacted by MSMEs within metropolitan contexts.

Against this backdrop, the present study examined the role of the private sector and MSMEs in advancing CE in arid metropolitan regions, utilizing a major industrial metropolitan area as an empirical case. By focusing on firm-level engagement with circular practices, such as waste reduction, recycling, resource efficiency, and sustainable production, the study addressed a critical gap in the literature between macro-level CE strategies and micro-level implementation realities. Specifically, the study situated MSME behavior within broader metropolitan governance structures, regulatory frameworks, and spatial-economic conditions, thereby contributing to urban studies debates on sustainability transitions, place-based policy, and urban political economy.

Methodologically, the study employed a structured quantitative approach to assess MSMEs’ participation in CE practices and identify the institutional, regulatory, and financial factors shaping private sector engagement. By foregrounding the experiences of MSMEs in an arid metropolitan context, the research advances a more nuanced understanding of CE transitions as context-dependent, governance-mediated, and socially differentiated processes, rather than as universally replicable models [

7,

10].

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the review of the conceptual and empirical literature on CE transitions with a focus on urban governance, MSMEs, and regional political economy.

Section 3 outlines the research methodology.

Section 4 presents the empirical findings, which are followed by a discussion of policy implications in

Section 5. Finally, the concluding section reflects on the broader implications for CE governance in arid metropolitan regions and outlines limitations and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

CE has been defined through a wide range of disciplinary lenses, reflecting its evolution from a narrowly technical concept toward a broader sustainability paradigm. Early CE frameworks were largely rooted in engineering, industrial ecology, and waste management, emphasizing the closure of material loops through recycling, reuse, and remanufacturing. These approaches primarily focused on efficiency gains within existing production systems, often assuming compatibility with continued economic growth and technological optimization [

1,

6,

15]. Systematic reviews of prevalent definitions of CE reveal a strong emphasis on material flows and resource efficiency, with limited attention given to social relations, institutional dynamics, or power structures [

3,

30].

More recent critical scholarship has increasingly challenged this technocratic framing, arguing that CE should be understood, fundamentally, as a political–economic project rather than a neutral technical solution. From this perspective, CE strategies are shaped by institutional contexts, growth imperatives, and uneven power relations, which raises concerns that circularity may reproduce linear extractive logics under a sustainability label if it prioritizes efficiency without addressing absolute resource reduction, redistribution, or social equity [

5,

21,

26]. These critiques are particularly salient within urban studies, where the CE is examined not only as an environmental strategy but also as an urban development model embedded in capitalist urbanization processes and territorial restructuring [

7]. Therefore, recent debates distinguish between “weak” circularity, which focuses on incremental improvements within existing systems, and “strong” circularity, which calls for more fundamental transformations in production, consumption, and governance regimes [

23,

31].

In recent years, cities and metropolitan regions have emerged as central spatial arenas for CE implementation due to their concentration of material flows, infrastructure, labor, and governance capacity. The concept of “circular cities” highlights the role of urban planning, industrial symbiosis, and localized governance arrangements in enabling resource efficiency and waste reduction [

8,

18,

32]. Empirical studies, particularly from European contexts, demonstrate that urban CE strategies are highly place-specific, shaped by historical development trajectories, institutional arrangements, and regional economic structures [

9,

33]. Urban Studies scholarship, however, cautions against treating cities as homogeneous units, arguing that CE initiatives are unevenly distributed across metropolitan space.

According to research, CE projects often concentrate in core urban areas, flagship developments, or formal industrial zones, whereas peripheral areas, informal sectors, and smaller firms remain marginal to circular strategies [

17,

34]. This spatial unevenness raises concerns regarding accessibility, employment distribution, and social inclusion within circular transitions. Scholars further argue that place-based governance plays a decisive role in mediating CE outcomes, as local institutions shape how policies interact with land use, labor markets, and industrial systems [

10,

11]. Without such territorial sensitivity, CE strategies risk becoming abstract policy narratives disconnected from lived urban realities.

However, despite the rapid expansion of urban CE literature, arid metropolitan regions remain underrepresented in empirical research, facing distinct structural constraints, including water scarcity, high energy demand, limited recycling infrastructure, and dependence on resource-intensive industries [

12]. Such conditions simultaneously heighten the urgency of CE solutions and complicate their implementation. Therefore, existing studies focusing on Gulf and other arid-region contexts suggest that CE adoption is often driven by state-led strategies linked to industrial diversification, environmental resilience, and climate commitments [

13,

14,

27]. While these frameworks provide strategic direction, they tend to prioritize large-scale industrial actors and infrastructure investments, offering limited insight into how CE principles are experienced and enacted at the level of smaller firms and localized economic practices [

29].

From a critical urban studies perspective, this raises salient questions about whose interests are prioritized within arid-region CE agendas. Scholars warn that CE transitions in resource-constrained regions risk excluding MSMEs and informal actors unless governance mechanisms explicitly address capacity gaps, distributive outcomes, and access to shared infrastructure [

20,

22,

35]. Understanding CE implementation, therefore, requires paying attention to not only policy ambition but also the everyday constraints faced by diverse economic actors embedded in arid metropolitan systems.

The private sector is widely recognized as central to operationalizing CE principles, given its role in production, consumption, and innovation systems [

16,

36,

37]. Within this landscape, MSMEs are especially significant due to their numerical dominance and deep embedding in local economies. MSMEs play a critical role in urban employment, service provision, and incremental innovation, which positions them as potential drivers of localized circular practices such as repair, reuse, recycling, and resource-efficient production [

18]. However, empirical evidence consistently shows that MSMEs face disproportionate barriers to CE adoption, including limited access to finance, regulatory complexity, insufficient technical knowledge, and weak integration into policy support mechanisms [

15,

38].

In metropolitan regions, these challenges are often exacerbated by spatial fragmentation, as MSMEs operate in dispersed industrial zones with limited access to shared infrastructure and collaborative networks, constraining opportunities for industrial symbiosis and collective circular solutions [

10,

39]. Critical scholars also argue that dominant CE narratives tend to privilege large firms capable of absorbing transition costs and navigating regulatory complexity, thereby reinforcing existing power asymmetries within urban economies [

21,

26]. Thus, from an urban studies perspective, this raises normative concerns regarding equity, inclusion, and the distribution of costs and benefits associated with circular transitions.

CE transitions are further shaped by multi-scalar governance arrangements spanning national strategies, metropolitan planning frameworks, and firm-level decision-making. While CE policies are often articulated at national or regional scales, their implementation depends heavily on local institutions and private sector engagement, creating potential scalar mismatches [

8,

23,

37]. In arid metropolitan regions, governance is frequently characterized by strong state involvement and centralized planning. Although this can accelerate policy diffusion, it may also limit bottom-up innovation and MSME participation if policy instruments are not sufficiently tailored to local business realities [

35]. Empirical research increasingly emphasizes the need for coordinated policy mixes combining regulation, incentives, capacity-building, and stakeholder engagement to enable effective CE implementation [

19,

20,

29]. Moreover, urban political economy scholarship underscores that governance choices shape not only environmental outcomes but also labor markets, firm survival, and spatial inequality [

22,

34,

39]. Therefore, evaluating CE transitions requires an integrated analytical perspective that connects firm-level behavior with metropolitan governance structures and regional political economies.

Against this backdrop, the existing literature reveals three interrelated gaps. First, there is a dearth of empirical research on CE implementation in arid metropolitan regions from an urban studies and political–economy perspective. Second, MSMEs remain underexplored as agents of circular transition despite the central role they play in metropolitan economies. Third, existing studies often overlook the scalar and governance tensions that condition MSME engagement with CE policies. Thus, this study addressed these gaps by empirically examining the role of the private sector and MSMEs in advancing the CE within an arid metropolitan context, integrating firm-level evidence with insights from urban governance and regional political economy to contribute to debates on sustainability transitions, spatial inequality, and place-based policy design.

3. Methodology

The present study employed a quantitative, cross-sectional research design to examine the role of the private sector and MSMEs in advancing the CE within arid metropolitan regions. Consistent with urban studies scholarship, the methodological approach is explicitly place-based and governance-sensitive, recognizing that CE transitions are shaped by local institutional arrangements, sectoral configurations, and metropolitan political economies rather than by universally replicable mechanisms [

8,

10,

40]. Rather than conceptualizing CE adoption as a purely technical or firm-internal decision, the study situated MSME behavior within broader urban–regional contexts, regulatory environments, and policy frameworks. This framing responds to calls for empirical approaches that bridge macro-level CE strategies with micro-level implementation realities, particularly in resource-constrained and arid metropolitan settings [

7,

11].

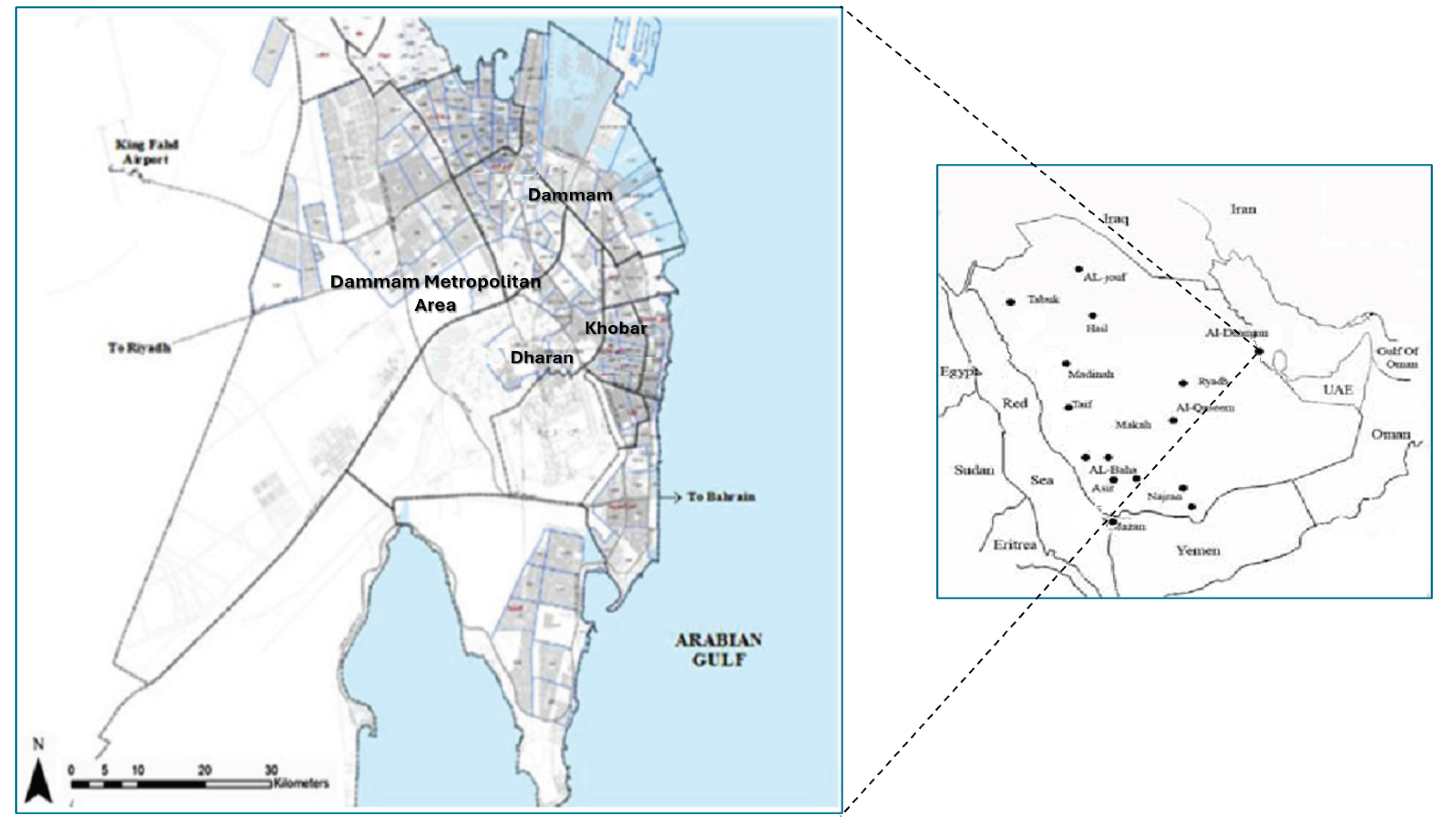

The empirical analysis focuses on a metropolitan region (i.e. Dammam Metropolitan Area) characterized by a complex urban–industrial structure comprising multiple interconnected cities and industrial zones. Dammam Metropolitan Area (DMA) hosts strong clusters in manufacturing, petrochemicals, logistics, construction, and services, alongside rapid urban expansion and infrastructure development (Figure1). As is typical of arid metropolitan regions, the study area faces acute sustainability challenges related to water scarcity, energy intensity, waste generation, and land-use pressures, which intensify the relevance and urgency of CE strategies [

12,

13,

14]. Thus, this metropolitan context provided a critical empirical setting for examining how CE policies and practices are mediated through local governance arrangements and private sector dynamics. Importantly, the region was not treated as an isolated or exceptional case but was situated within broader debates on arid-region urbanization, state-led development, and sustainability transitions central to Urban Studies.

Figure 1.

Geographical Location of Dammam Metropolitan Area, Saudi Arabia [

14].

Figure 1.

Geographical Location of Dammam Metropolitan Area, Saudi Arabia [

14].

Primary data were collected through a structured questionnaire survey administered to MSMEs and private sector firms operating across key economic sectors within the metropolitan region. The survey instrument was designed to capture firm-level engagement with CE practices while also assessing perceived barriers, enabling factors, and policy influences shaping CE adoption. The questionnaire collected information on firm characteristics, including size, sector, years of operation, and ownership structure; engagement with CE practices such as waste reduction, recycling, resource efficiency, and sustainable production; perceived barriers related to financial constraints, regulatory complexity, technological limitations, and market uncertainty; enabling factors and policy instruments, including regulatory frameworks, financial incentives, and institutional support mechanisms; and firms’ perceptions of metropolitan governance, particularly policy coordination, clarity, and support.

Survey items were measured using Likert-scale responses to capture variations in intensity and perception, an approach widely employed in firm-level sustainability and CE research [

15,

33,

39,

41,

42,

43,

44]. The instrument was refined through an expert review to ensure clarity, contextual relevance, and consistency with regulatory and institutional terminology specific to arid metropolitan governance environments. Given the absence of a comprehensive public registry of CE-active MSMEs, the study employed a purposive sampling strategy targeting firms across manufacturing, logistics, construction, services, and related urban–industrial sectors. These sectors were selected due to their material intensity, waste generation potential, and relevance to CE implementation within metropolitan regions. The sampling was complemented by sectoral outreach through business associations, industrial zones, and professional networks, which is consistent with the urban studies research practices that prioritize analytical relevance and contextual depth when examining emerging sustainability transitions [

24,

45,

46,

47].

The target population comprised 250 MSMEs operating within the selected metropolitan region. Based on comparable expert and firm-level surveys conducted in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) contexts, a response rate of 70–80% was anticipated [

14]. This study achieved a response rate of 72%, resulting in a final sample of 180 valid responses used for the empirical analysis. This response rate is consistent with best practice standards for firm-level survey research in policy-oriented urban and regional studies.

Quantitative data analysis combined descriptive and inferential statistical techniques. Descriptive statistics were used to examine the prevalence and distribution of CE practices across sectors and firm sizes, providing an overview of MSME engagement within the metropolitan region [

46,

47]. To identify underlying dimensions of CE adoption and perceived barriers, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted using principal component analysis with varimax rotation. Further, sampling adequacy was assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was utilized to confirm factorability following established methodological standards [

48,

49,

50]. Subsequently, regression analysis was employed to examine relationships between firm characteristics, policy-related variables, and levels of CE engagement, enabling the identification of statistically significant associations while remaining attentive to the structural and governance conditions emphasized in urban studies scholarship [

15,

24,

32,

37,

50].

Consistent with critical urban research practices, the paper acknowledges several methodological limitations. The cross-sectional design captures MSME perceptions and practices at a single point in time, limiting insights into the temporal dynamics of CE transitions. Reliance on self-reported data may introduce response bias, particularly in relation to socially desirable sustainability practices. Moreover, while the study adopted a place-based analytical lens, it did not explicitly capture informal economic activities, which might play a significant role in circular practices in certain metropolitan contexts [

20,

44]. These limitations are understood not as methodological shortcomings but as reflections of broader structural challenges inherent in studying emerging sustainability transitions in complex urban systems.

Participation in the survey was voluntary, and respondents were assured of confidentiality and anonymity. Data collection and analysis were conducted in accordance with established ethical research standards, ensuring that firm-level information was used solely for academic and research purposes.

By integrating firm-level quantitative analysis with a place-based and governance-sensitive framework, this methodology advances urban studies approaches to CE research. It moves beyond technocratic assessments of CE adoption to foreground the institutional, spatial, and political–economic conditions shaping MSME engagement in arid metropolitan regions, demonstrating how quantitative methods can be mobilized within a critical urban analytical framework.

4. Results

4.1. General Information

This subsection presents the general characteristics of the surveyed firms and examines how sectoral structure, firm size, and metropolitan location inform the composition of the sample. In line with Urban Studies scholarship, the analysis treated these characteristics not merely as descriptive attributes but as indicators of broader metropolitan political–economic structures that condition firms’ capacity to engage with CE practices [

8,

11]. As

Table 1 shows, the sample (n = 180) reflected a heterogeneous but MSME-dominated metropolitan economy. Firms operating in services (21.7%), manufacturing (21.1%), and tourism-related activities (20.0%) constituted the largest shares of respondents, followed by real estate (16.7%), trade (12.2%), and other activities (8.3%). This sectoral distribution mirrors patterns identified in metropolitan CE research, where service-oriented and mixed economies coexist with material-intensive industrial activities, producing uneven opportunities for circular practices across sectors [

9,

18,

50].

In terms of firm size, micro (30.0%) and small enterprises (23.9%) together accounted for more than half of the sample, confirming the strong MSME orientation of the dataset. Medium-sized firms represented 24.4% of the data, while large firms accounted for 21.7%. The mean coded firm size (M = 2.37, SD = 1.01) fell between the micro and small categories, reinforcing the analytical relevance of focusing on MSMEs as structurally embedded but resource-constrained actors within metropolitan economies. This profile is consistent with urban studies critiques that highlight MSMEs as central but often marginalized participants in sustainability transitions dominated by large-scale corporate actors [

35,

45,

50].

Spatially, firms were concentrated in the metropolitan core, particularly Dammam (35.0%), followed by Dhahran (16.7%), Ras Tanurah (16.7%), and Al Khobar (13.3%), with additional representation from Qatif (11.7%) and other peripheral locations (6.6%). The mean coded location value (M = 2.94, SD = 1.63) indicates a spatial spread that captures both core and secondary urban–industrial areas. This distribution is analytically important, as prior research emphasizes that CE opportunities and constraints are spatially differentiated within metropolitan regions, reflecting uneven access to infrastructure, markets, and governance support [

10,

34,

39].

To explore whether firm characteristics are unevenly distributed across metropolitan space, chi-square tests of independence were conducted. The results reveal a statistically significant association between firm size and metropolitan location (χ² = 18.62, p = 0.046), indicating that MSMEs and larger firms are not evenly distributed across the metropolitan area. This finding aligns with urban studies research highlighting how firm scale and economic function tend to cluster spatially, often reflecting historical industrial development, zoning practices, and infrastructure availability [

10,

17]. Conversely, the association between business activity type and location was found to be statistically insignificant, suggesting that sectoral diversity is relatively dispersed across the metropolitan region. This pattern supports arguments that contemporary metropolitan economies increasingly exhibit mixed-use and multi-sectoral spatial configurations rather than strict sectoral segregation [

8].

To further examine structural differences across sectors, a one-way ANOVA was conducted to evaluate whether average firm size differs by business activity type. The results indicate statistically significant differences in mean firm size across sectors (F = 4.12, p = 0.002). Moreover, post-hoc comparisons reveal that manufacturing and real estate firms tend to employ more workers on average than firms in services and trade-related activities, reinforcing insights from the CE and urban political economy literature, which stress that sectoral position influences firms’ resource capacity, investment horizons, and ability to adopt circular practices [

15,

21]. In metropolitan CE transitions, such sectoral differences are critical, as larger and more capital-intensive firms often face fewer barriers to compliance and innovation than smaller service-oriented enterprises.

Overall, the results of this subsection confirm that the surveyed firms operate within a structurally differentiated metropolitan economy, where firm size and spatial location are interrelated and sectoral position shapes organizational scale. These patterns provide an essential contextual foundation for subsequent analysis of CE practices. Consistent with urban studies scholarship, the findings suggest that CE adoption cannot be understood independently of metropolitan structure, spatial inequality, and firm-level capacity [

7,

11]. The observed heterogeneity underscores the importance of accounting for sectoral and spatial variation when assessing private sector and MSME engagement in CE transitions in arid metropolitan regions.

4.2. Awareness and Perceptions of CE

This subsection examines firms’ awareness of CE, their perceptions of its relevance to business operations, and the extent to which specific circular practices are currently applied. Consistent with urban studies scholarship, awareness and perception are interpreted not simply as individual attitudes but as outcomes shaped by sectoral position, firm capacity, and metropolitan political–economic structures [

8,

11].

The results revealed a relatively high level of awareness of CE across the surveyed firms. As

Table 2 shows, nearly three-quarters of respondents (73.3%) reported that they had heard of the CE concept, while 26.7% indicated no prior awareness. This suggests that CE discourse has achieved substantial visibility within the metropolitan private sector, reflecting the diffusion of sustainability narratives through policy initiatives, institutional channels, and business networks. Similar patterns of widespread awareness, particularly in metropolitan regions where sustainability agendas are actively promoted, have been reported in previous studies [

36,

37]. However, urban studies scholars caution that awareness alone does not necessarily translate into meaningful engagement or structural change [

5,

21]; awareness may coexist with limited capacity to act, especially among MSMEs operating under financial, regulatory, and infrastructural constraints.

Respondents were further asked to evaluate the relevance of CE to their business operations. As summarized in the analysis, their perceptions were generally positive, with a majority of firms rating CE as moderately relevant, relevant, or highly relevant. The mean relevance score (M = 3.64, SD = 1.18) indicates an overall favorable orientation toward CE, although notable variation exists across respondents. This variation reflects long-standing findings in the CE literature, which states that firms’ perceptions of relevance are influenced by sectoral exposure, cost structures, and anticipated regulatory pressure [

15,

16]. From an urban studies perspective, such heterogeneity underscores the uneven embedding of CE agendas within metropolitan economies, where firms differ markedly in their production logics and strategic horizons [

9].

While awareness and perceived relevance are relatively high, actual adoption of CE practices remains uneven. As the analysis demonstrated, firms were most likely to engage in recycling of waste materials (56.1%) and resource efficiency measures such as reducing energy and water use (52.2%). Conversely, more systemic or collaborative practices, such as reuse of materials (35.0%), eco-design (26.7%), and industrial symbiosis with other firms (21.7%), were less widely adopted. Notably, 15.0% of firms reported not applying any CE practices. These findings align with the broader CE literature, which consistently shows that MSMEs tend to prioritize incremental, cost-saving measures over transformative or coordination-intensive practices [

1,

18]. Urban studies scholars further argue that collaborative practices such as industrial symbiosis require enabling governance frameworks, shared infrastructure, and spatial proximity, which are often unevenly developed within metropolitan regions [

10,

24].

Chi-square tests of independence were conducted to explore whether awareness and perceptions vary across firm characteristics. The association between awareness of CE and firm size was found to be statistically insignificant at the 5% level (χ² = 11.88, p = 0.060), suggesting that CE awareness is relatively evenly distributed across micro, small, medium, and large firms rather than being concentrated among larger enterprises. This finding supports arguments in the urban studies literature that sustainability discourses increasingly circulate across metropolitan business ecosystems, even where firms’ capacities to implement CE practices remain uneven [

8,

9]. Awareness, therefore, appears to be a necessary but insufficient condition for circular transition. In contrast, the analysis revealed a highly significant association between perceived relevance of CE and type of business activity (χ² = 54.02, p < 0.001), indicating that firms’ evaluations of CE are strongly shaped by sectoral position. Manufacturing- and real-estate-related activities tend to assign higher relevance to CE, while service- and trade-oriented firms display more heterogeneous perceptions. This is consistent with CE and urban political economy scholarship, which emphasizes that sectoral characteristics, such as material intensity, regulatory exposure, and capital requirements, play a decisive role in shaping firms’ engagement with circular strategies [

11,

15,

16]. From an urban studies perspective, such sectoral differentiation highlights the need for place- and sector-specific policy instruments rather than uniform CE strategies.

Taken together, the results demonstrate a clear distinction between discursive diffusion and practical engagement with CE. While awareness of CE concepts is widespread across firm sizes, the perceived relevance and adoption of CE practices vary substantially across sectors and practice types. Firms tend to adopt efficiency-oriented measures that align with immediate economic benefits, whereas more transformative or collaborative forms of circularity remain limited. These patterns reinforce critical perspectives in urban studies that caution against assuming that awareness and positive attitudes will automatically lead to structural transformation [

7,

21]. Thus, these findings provided a critical bridge to the subsequent analysis of barriers and enabling conditions, suggesting that effective CE transitions in arid metropolitan regions require sector-sensitive, governance-driven, and spatially embedded policy approaches rather than reliance on awareness-raising alone.

4.3. Barriers and Challenges to CE Adoption

This subsection focuses on the barriers constraining CE adoption among private sector firms and MSMEs, moving beyond descriptive assessment to identify latent structural constraints and their empirical relationship with CE adoption behavior. Consistent with urban studies scholarship, barriers are interpreted as outcomes of institutional configurations, labor-market structures, and governance conditions rather than as isolated firm-level deficiencies [

8,

10,

38,

39,

40].

Respondents were asked to assess six commonly cited barriers to CE adoption using a five-point Likert scale (where 1 = not a barrier and 5 = major barrier). As

Table 3 shows, firms perceived barriers as moderate to significant overall, with external and systemic constraints ranking higher than purely internal limitations. Weak regulatory enforcement emerged as the most significant barrier (M = 3.66, SD = 1.19), followed by market demand uncertainty (M = 3.53, SD = 1.21). These findings suggest that firms view the broader governance and market environment as a critical constraint on circular transition. Such perceptions align with urban studies critiques emphasizing that CE strategies are governance-mediated processes, dependent on regulatory credibility and demand-side coordination rather than awareness alone [

7,

21,

50]. Furthermore, barriers related to skills shortages (M = 3.42, SD = 1.13) and limited access to technology (M = 3.09, SD = 1.16) were also perceived as important, reflecting operational capacity constraints faced by MSMEs. On the other hand, a lack of financial resources (M = 2.87, SD = 1.48) was rated as the least severe barrier on average, although still positioned between a minor and moderate constraint. This ordering challenges policy narratives that prioritize financing alone and reinforces arguments that institutional coherence and labor-market readiness are equally, if not more, decisive [

11,

22,

33,

41].

To identify the underlying dimensions shaping firms’ perceptions of CE barriers, an EFA was conducted on the six barrier items. Sampling adequacy and factorability were confirmed through the KMO measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity [

48,

49]. Using principal component analysis with varimax rotation, three factors with eigenvalues greater than one were retained, jointly explaining 72.9% of total variance. The rotated factor solution also revealed a clear and theoretically meaningful structure. These factors are interpreted as follows:

Factor 1: Operational and Capability Constraints (skills and technology)

Factor 2: Governance and Market Environment Constraints (regulation and demand)

Factor 3: Knowledge and Financial Constraints (awareness and finance)

This structure empirically supports urban studies arguments that CE barriers are multidimensional, reflecting the interaction between internal firm capacity and external institutional conditions [

10,

26,

38,

39,

40]. Additionally, internal consistency was also assessed using Cronbach’s alpha for each factor. Reliability is acceptable for the operational-capability factor and moderate for governance-market constraints, while the knowledge-financial factor exhibits lower internal consistency, suggesting that awareness and finance may operate independently across firms and sectors.

To examine how these barrier dimensions influence CE adoption, factor scores were generated and regressed against a CE adoption index (0–5), constructed from firms’ reported circular practices. The results indicate that operational and capability constraints have a statistically significant negative effect on overall CE adoption (B = −0.200, p = 0.006), while governance-market and knowledge-financial constraints do not exhibit significant associations in the aggregate model. These findings suggest that while firms perceive governance and market conditions as major barriers, actual adoption behavior is more strongly constrained by internal skills and technological capacity. This distinction echoes urban studies critiques of sustainability transitions that highlight the gap between perceived external constraints and operational realities at the firm level [

7,

31,

32,

38]. Additionally, to capture heterogeneity across CE practices, binary logistic regressions were estimated for each practice, revealing practice-specific sensitivities to different barrier dimensions. Operational and capability constraints significantly reduce the likelihood of adopting eco-design and resource efficiency, while knowledge-financial constraints are particularly restrictive for inter-firm collaboration, a finding consistent with urban studies research emphasizing the institutional and relational complexity of industrial symbiosis [

10,

24].

Overall, this subsection demonstrates that barriers to CE adoption among metropolitan MSMEs are structural, multidimensional, and practice-specific. While governance and market uncertainty dominate firms’ perceptions, operational capabilities, skills, and technology emerge as the most decisive constraints on actual adoption behavior. This divergence reinforces critical perspectives in the CE literature that caution against awareness- or regulation-centric approaches and call for integrated policy frameworks addressing labor markets, technological capacity, and institutional coordination [

11,

17,

21]. These findings serve as a robust empirical foundation for the subsequent analysis of policy enablers and institutional mechanisms, highlighting where targeted interventions can most effectively support CE transitions in arid metropolitan regions.

4.4. Opportunities and Support for Advancing CE

This subsection examines the opportunities that MSMEs identify within CE and the types of institutional and policy support required to translate these opportunities into tangible investment and implementation. In line with urban studies scholarship, opportunities are conceptualized not as abstract market possibilities but as place-specific development trajectories, shaped by metropolitan industrial structure, spatial organization, and governance arrangements [

8,

9]. The survey results indicated that MSMEs identify a broad range of CE opportunities, with a strong concentration in resource-based and efficiency-oriented activities. As

Table 4 shows, the most frequently identified opportunities were waste recycling and materials recovery (65.6%), renewable energy and energy efficiency (57.8%), and green construction and retrofitting (53.3%). These opportunity areas correspond closely to dominant material flows and growth sectors in arid metropolitan regions, where construction activity, energy demand, and waste generation are structurally significant.

Moderate levels of opportunity recognition are observed for repair, refurbishment, and reuse services (41.1%) and sustainable packaging and eco-design (38.3%). These activities are more labor- and skills-intensive and depend on market demand and standards, reflecting pathways that can generate local employment but require supportive regulatory and consumer frameworks. In contrast, circular supply chains and logistics (27.2%) and digital sharing or product-as-a-service models (23.3%) are less frequently identified, highlighting the higher coordination, data integration, and governance requirements associated with these models. Urban studies research emphasizes that such systemic circular strategies depend on metropolitan-scale coordination and institutional capacity that often exceed the standalone capabilities of MSMEs [

10,

24]. The relatively selective identification of sustainable tourism and blue–green economy niches (20.0%) further underscores the spatial specificity of certain circular opportunities, which are contingent on local environmental assets and place-based development strategies rather than uniform replication [

11].

While MSMEs clearly recognize multiple CE opportunities, their realization is strongly conditioned by access to institutional and policy support. Respondents rated the importance of five support mechanisms on a five-point Likert scale. As reported, all mechanisms were rated as important to very important, indicating a clear expectation of coordinated public and institutional intervention. Financial incentives receive the highest mean rating (M = 4.32, SD = 0.79), reflecting the importance of risk reduction and access to capital for CE investments. Training and capacity building (M = 4.21, SD = 0.83) are also highly prioritized, reinforcing findings from

Section 4.3 that skills and organizational capabilities are critical determinants of CE adoption. The high valuation of government regulation and enforcement (M = 4.05, SD = 0.88) signals the importance of policy credibility and regulatory consistency—an issue repeatedly emphasized in Urban Studies critiques of sustainability transitions [

7,

21]. Support for partnerships with large firms and anchor industries (M = 3.94) and access to recycling facilities and eco-parks (M = 3.87) highlights the relational and spatial dimensions of CE implementation. These mechanisms enable MSMEs to overcome scale limitations, integrate into value chains, and access shared metropolitan infrastructure, aligning with urban studies perspectives on the role of spatial planning and inter-firm coordination in sustainability transitions [

8,

9,

10].

The interaction between opportunity recognition and support availability is reflected in firms’ stated willingness to invest in CE practices. As shown in the analysis, a majority of respondents (51.1%) reported a clear willingness to invest if adequate financial or technical support is provided, while an additional 35.0% indicated conditional willingness. Only 13.9% expressed unwillingness to invest. This distribution provides strong empirical support for urban studies arguments that MSMEs are not inherently resistant to sustainability transitions but rather conditionally willing actors whose engagement depends on policy design, risk-sharing mechanisms, and institutional support [

7].

Taken together, the findings of this section demonstrate a strong alignment between recognized CE opportunities, demand for institutional support, and latent willingness to invest among MSMEs. Firms identify viable entry points into the CE, particularly in waste management, energy efficiency, and construction, but emphasize that scaling these opportunities requires financial incentives, skills development, regulatory credibility, and access to shared metropolitan infrastructure. From an urban studies perspective, these results reinforce the argument that CE transitions in arid metropolitan regions are governance-mediated urban development processes rather than spontaneous market outcomes. Effective CE strategies must, therefore, combine economic instruments, institutional coordination, and spatial planning to mobilize MSMEs as active agents of circular urban transformation [

8,

10,

11,

17].

4.5. Future Outlook: The Strategic Role of MSMEs in Advancing CE

This subsection explores respondents’ perspectives on the future role of MSMEs in advancing the CE within the metropolitan context. In line with urban studies scholarship, future outlook is interpreted as a reflection of anticipated development pathways, governance expectations, and institutional positioning rather than as abstract aspirations [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Respondents were asked to identify the most important roles MSMEs should play in advancing CE, and the results revealed a forward-looking and strategically differentiated vision, in which MSMEs are expected to act not only as implementers of efficiency measures but also as active agents of innovation, integration, and social engagement.

As

Table 5 shows, the most frequently identified future role for MSMEs is recycling and waste management (71.3%), thus highlighting expectations that MSMEs will continue to anchor localized waste-to-resource solutions. This aligns with urban studies research that stresses the importance of localized circular infrastructures and decentralized material recovery systems in metropolitan regions [

1,

10,

11,

23]. A similarly high share of respondents emphasize supply chain integration with large firms (68.5%), indicating a clear expectation that MSMEs should function as connective nodes within metropolitan and industrial value chains, particularly in partnership with anchor firms and logistics hubs. This reinforces earlier findings (Subsections 4.3 and 4.4) that inter-firm coordination and institutional linkage are critical for scaling circular practices beyond isolated firm-level initiatives [

8,

11,

17].

More than half of respondents identify community engagement (54.1%) as a key future role, reflecting recognition that MSMEs are embedded within local communities and can influence consumption behavior, awareness, and social norms. This social dimension of CE is increasingly stressed in urban studies critiques, which argue that CE transitions must engage everyday practices and local social relations, not only production systems [

7,

21,

33]. Roles related to resource efficiency (49.7%), innovation and eco-design (45.9%), and green job creation (45.3%) are also strongly represented. These results suggest that MSMEs are expected to contribute simultaneously to technological innovation, environmental efficiency, and inclusive employment, positioning them as central actors in metropolitan sustainability transitions rather than marginal followers of large firms.

Overall, the future outlook articulated by respondents positions MSMEs as multifunctional actors in the CE, simultaneously innovators, service providers, community intermediaries, and supply-chain partners. The prominence of supply-chain integration and recycling roles suggests that respondents envision a more interconnected and institutionally embedded CE, rather than a collection of isolated firm-level initiatives. From an urban studies perspective, these findings reinforce arguments that successful circular transitions depend on hybrid governance arrangements, where MSMEs operate within coordinated metropolitan systems shaped by policy, planning, and industrial strategy [

8,

10]. The emphasis on community engagement and green job creation further highlights the expectation that CE strategies should contribute to social inclusion and local development, not only environmental efficiency.

Taken together, the results suggest that the future CE in arid metropolitan regions will depend heavily on empowering MSMEs as strategic intermediaries, linking large industrial actors, local communities, and public institutions within an integrated urban sustainability framework [

7,

11,

16,

17]. The future outlook underscores the need for policy frameworks that recognize MSMEs as system-building actors, providing a foundation for the subsequent discussion of policy implications and strategic pathways in

Section 5.

5. Discussion and Policy Implications

This section synthesizes the empirical findings presented in the results sections and situates them within broader urban studies debates on sustainability transitions, metropolitan governance, and the role of small firms in structural economic transformation. Rather than framing CE as a purely technical or market-driven shift, the discussion emphasizes the institutional, spatial, and political–economic conditions that shape MSMEs’ engagement with circular practices in arid metropolitan regions.

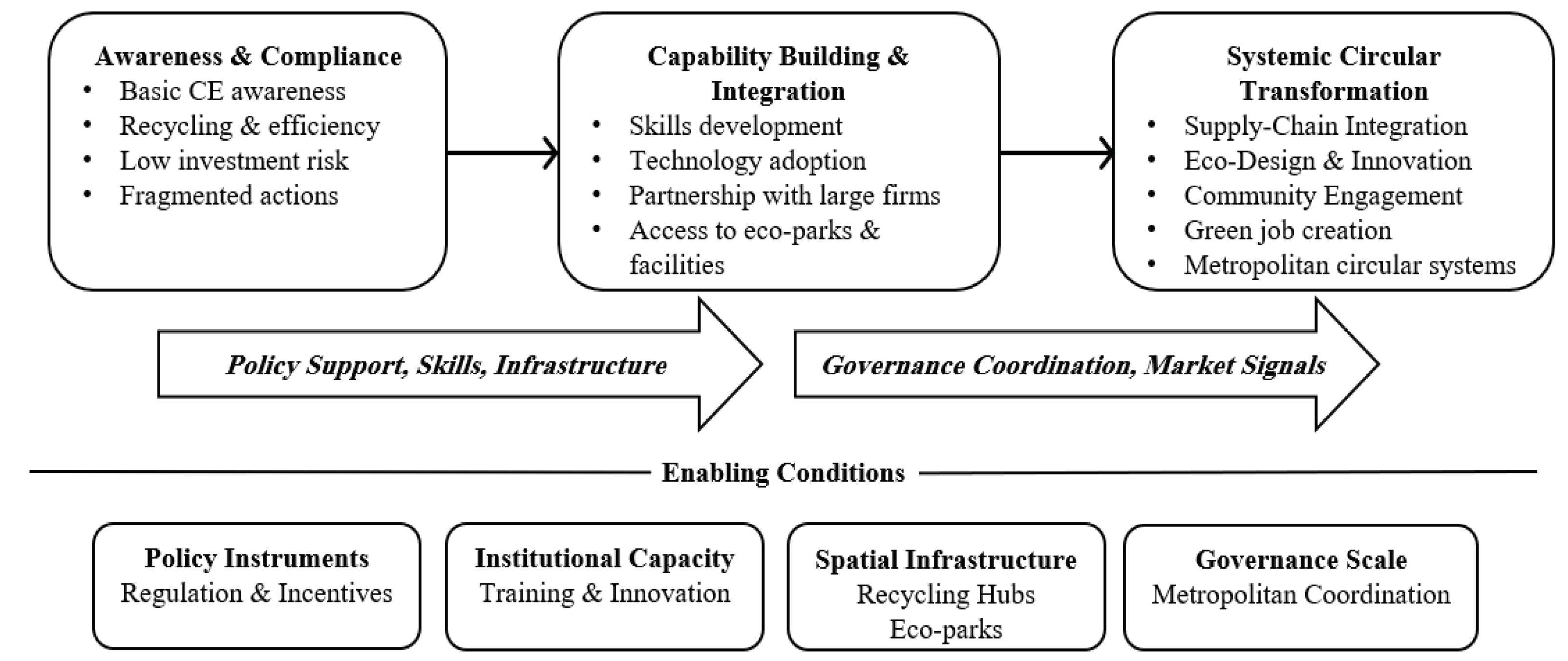

Figure 1 provides an integrative conceptual synthesis of these findings.

Specifically,

Figure 1 illustrates the evolving role of MSMEs across different phases of the CE transition, showing how firms move from basic awareness and compliance toward capability building, value-chain integration, and systemic circular transformation. The figure visually connects the empirical evidence on barriers, opportunities and support mechanisms, and future expectations, and highlights the cross-cutting importance of governance capacity, policy support, skills development, and metropolitan-scale infrastructure in enabling this progression.

Figure 2.

MSMEs’ Evolving Role in the CE Transition in Arid Metropolitan Regions.

Figure 2.

MSMEs’ Evolving Role in the CE Transition in Arid Metropolitan Regions.

Conceptual framework illustrating the progressive evolution of MSMEs from basic adoption of circular practices toward systemic CE participation: The framework highlights three transition phases, awareness and compliance, capability building and integration, and systemic circular transformation, identifying the cross-cutting governance, institutional, and spatial conditions that enable movement across phases in arid metropolitan contexts.

Consistent with earlier empirical studies, the findings confirm that MSMEs tend to prioritize resource-based and efficiency-oriented circular practices, such as recycling, energy efficiency, and green construction. Similar adoption patterns have been observed in European and Asian metropolitan contexts, where MSMEs favor circular activities that align with existing operational models and offer relatively immediate economic returns [

1,

18,

32]. As depicted in the initial phase of

Figure 1, these practices correspond to a stage of incremental circularity, characterized by low-risk adaptation rather than systemic transformation. However, this study extends prior work by demonstrating that such adoption patterns are not primarily driven by awareness gaps, as suggested in some earlier studies on CE [

2,

3], but by capability-related constraints, particularly skills and technological capacity. This finding aligns with more recent urban studies research arguing that sustainability transitions are often constrained by institutional and infrastructural deficits rather than informational shortcomings [

22,

34]. In

Figure 1, this constraint is reflected in the transition bottleneck between the first and second phases, where movement toward deeper circular engagement depends on targeted capability-building and institutional support.

The limited uptake of more systemic circular models, such as circular supply chains, industrial symbiosis, and platform-based solutions, also echoes findings from [

10] and [

24], which emphasize the importance of metropolitan-scale coordination and shared infrastructure. This study contributes additional insight by showing that MSMEs in arid metropolitan regions recognize these models as future opportunities but perceive them as difficult to operationalize without external support. As illustrated in

Figure 1, this reflects a latent transition potential, rather than resistance, contingent on governance alignment and spatial integration.

Importantly, the high level of conditional willingness to invest observed in this study challenges earlier portrayals of MSMEs as reluctant or risk-averse actors in sustainability transitions [

16]. Instead, the findings support more recent critical accounts that frame MSMEs as conditionally willing participants, whose engagement depends on policy credibility, risk-sharing mechanisms, and access to enabling infrastructure [

7,

24]. This conditionality is explicitly captured in

Figure 1, where policy instruments and institutional capacity function as enabling layers across all transition phases.

From a regional perspective, the results complement existing research on arid and Gulf metropolitan contexts, which highlights the dominance of state-led CE strategies focused on large industrial actors and flagship projects [

13,

14,

27]. While such strategies provide strategic direction, the present findings reveal a persistent gap between macro-level policy ambition and micro-level firm capacity. By foregrounding MSMEs’ experiences, this study responds to calls for more grounded, actor-centered analyses of CE implementation in resource-constrained urban regions [

20,

21,

22]. The comparative insights derived from this study point to several interrelated policy implications.

First, CE policies must move beyond awareness-oriented approaches toward sustained capability-building. As illustrated in the transition from Phase 1 to Phase 2 in

Figure 1, targeted training programs, applied technical assistance, and support for technology adoption are critical for enabling MSMEs to move beyond basic compliance toward integrated circular practices.

Second, policy credibility and regulatory coherence are central to MSME engagement. Consistent with urban studies scholarship [

8,

10], the findings show that MSMEs require stable, predictable, and enforceable regulatory frameworks to justify investment in circular practices. Fragmented or short-term policy signals risk reinforcing incremental circularity rather than enabling systemic transformation.

Third, the study underscores the importance of metropolitan-scale infrastructure and coordination, reflected in

Figure 1 as a cross-cutting enabling condition. Investment in shared facilities, such as eco-parks, recycling hubs, and circular logistics platforms, can lower entry barriers for MSMEs and facilitate inter-firm collaboration, particularly in arid metropolitan regions where resource constraints are acute [

10,

11,

17,

38,

39,

40,

41].

Fourth, MSMEs should be repositioned within CE strategies as integrators within circular value chains, rather than as peripheral beneficiaries of incentives. Policies that facilitate partnerships between MSMEs and large firms can help overcome scale limitations and embed smaller firms within metropolitan circular systems, corresponding to the third phase of systemic circular transformation depicted in

Figure 1.

Finally, the emphasis on community engagement and green job creation highlights the need to align CE strategies with broader urban development and social inclusion objectives. As Urban Studies critiques emphasize, circular transitions that neglect distributive outcomes risk reinforcing existing inequalities and undermining political legitimacy [

22,

34].

By explicitly linking firm-level behavior to metropolitan governance, institutional capacity, and spatial infrastructure, this study advances urban studies scholarship on sustainability transitions. The conceptual framework presented in

Figure 1 extends existing CE models by situating MSMEs within a dynamic, place-based transition pathway, rather than treating them as static adopters of predefined practices. Overall, the study demonstrates that advancing the CE in arid metropolitan regions requires empowering MSMEs as system-building actors, capable of linking production, policy, and community spheres within coordinated urban governance frameworks. In doing so, it contributes both empirically and conceptually to debates on inclusive, place-sensitive CE transitions.

6. Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

This study examined the role of the private sector and MSMEs in advancing CE within an arid metropolitan context, adopting a place-based and governance-sensitive urban studies perspective. The findings demonstrate that MSMEs are neither passive recipients of CE policies nor inherently resistant to sustainability transitions, emerging instead as conditionally willing, structurally embedded actors, whose engagement with circular practices is shaped by operational capacity, sectoral position, and the institutional and spatial configuration of metropolitan governance.

Empirically, the study found that MSMEs tend to prioritize resource-based and efficiency-oriented circular practices, such as recycling, energy efficiency, and green construction, while more systemic and coordination-intensive models remain limited. This pattern reflects rational adaptation to existing governance and market conditions rather than a lack of awareness or motivation. The analysis further revealed that capability-related constraints, particularly skills and technological capacity, exert a stronger influence on circular adoption than awareness alone, underscoring the importance of capacity-building and institutional support. Simultaneously, the high latent willingness to invest under supportive conditions highlighted the potential for accelerated circular transitions if governance frameworks are appropriately aligned. Thus, from an urban studies standpoint, the study contributes to ongoing debates by reframing CE transitions as urban development processes embedded within metropolitan political economies. The findings emphasize that effective circular strategies require coordinated policy mixes that integrate regulatory credibility, financial incentives, spatial infrastructure, and inter-firm collaboration. Importantly, the study positioned MSMEs as potential system-building actors, capable of linking production, policy, and community spheres when supported by coherent metropolitan governance.

Despite these contributions, the study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional research design captured MSME perceptions and practices at a single point in time; this limited the study’s ability to assess dynamic or longitudinal changes in circular adoption. Second, reliance on self-reported survey data might have introduced response bias, particularly in relation to socially desirable sustainability practices. Third, while the study adopted a place-based analytical lens, it did not explicitly capture informal economic activities or micro-enterprises operating outside formal regulatory frameworks, which might have played a significant role in circular practices in some metropolitan contexts. Finally, the focus on one arid metropolitan region constrained the direct generalizability of the findings, although the analytical insights are transferable to other arid and resource-constrained urban regions facing similar governance and structural conditions.

Therefore, future research must build on these findings in several directions. Longitudinal studies are needed to track how MSME engagement with the CE evolves in response to policy changes, economic shocks, and technological innovation. Comparative research across multiple arid metropolitan regions will further enhance understanding of how different governance models and institutional arrangements shape circular transitions. In addition, mixed-methods approaches incorporating qualitative interviews, policy analysis, and spatial data can deepen insight into the everyday practices, power relations, and informal dynamics that shape MSME participation in circular economies. Finally, future studies should explore the social dimensions of circular transitions more explicitly, including impacts on employment quality, equity, and community well-being, to ensure that CE strategies contribute to inclusive and resilient urban development.

In conclusion, advancing the CE in arid metropolitan regions requires moving beyond awareness-raising and isolated incentives toward empowering MSMEs through integrated, place-sensitive governance frameworks. By foregrounding the institutional, spatial, and political–economic conditions shaping MSME engagement, this study provides a foundation for more effective and inclusive CE policies capable of supporting sustainable urban transformation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University (protocol code IRB-2025-06-0593).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly acknowledge the support of Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbitt, C.; Gaustad, G.; Fisher, A.; Chen, W.-Q.; Liu, G. Closing the loop on circular economy research: From theory to practice and back again. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards a Circular Economy: Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. 2015. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular economy: The concept and its limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.; Bauwens, T.; Kirchherr, J.; Hekkert, M. A typology of circular start-ups: Analysis of 128 circular business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savini, F. The circular economy is over: The scalar politics of circular production. Urban Stud. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. Circular cities: Strategies for governing urban resource efficiency. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 2746–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisto Friant, M.; Reid, K.; Boesler, P.; et al. Sustainable circular cities? Analysing urban circular economy policies in Amsterdam, Glasgow, and Copenhagen. Local Environ. 2023, 28, 1331–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutz, P.; Jonas, A. E. G.; Newsholme, A.; et al. The role of place in the development of a circular economy: A critical analysis of potential for social redistribution in Hull, UK. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2024, 17, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdin, S.; Torre, A. Economic geography’s contribution to understanding the circular economy. J. Econ. Geogr. 2025, 25, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Water Scarcity and Circular Solutions in the GCC. 2023. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/opinion/2024/03/26/from-scarcity-to-sustainability-the-gcc-s-journey-towards-water-security (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Alnajem, M.; Elheddad, M.; Alfar, A. J. Circular economy in the Gulf Cooperation Council: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhowaish, A. K.; Alkubur, F. S. Unlocking the potential of the circular economy at municipal levels: A study of expert perceptions in the Dammam Metropolitan Area. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieder, M.; Rashid, A. Towards circular economy implementation: A comprehensive review in context of manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 115, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The circular economy: An interdisciplinary exploration of the concept and application in a global context. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niang, A.; Bourdin, S.; Torre, A. The geography of circular economy: Job creation, territorial embeddedness and local public policies. J. Environ. Plann. Manag. 2024, 67, 2939–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joensuu, T.; Edelman, H.; Saari, A. Circular economy practices in the built environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (KAPSARC). Financing Circular Economies in the Gulf: Challenges in Mobilizing Private Capital. 2022. Available online: https://www.kapsarc.org (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- UN-Habitat. Circular Economy Transitions in the Global South: Workforce Challenges and Informal Sector Exclusion. 2023. Available online: https://unhabitat.org (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Corvellec, H.; Stowell, A.; Johannson, N. Critiques of the circular economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2022, 26, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansera, M.; Barca, S.; Martinez Alvarez, B.; et al. Toward a just circular economy: Conceptualizing environmental labor and gender justice in circularity studies. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2024, 20, 2338592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutz, P. Exploring the limitations of a circular economy under capitalism and raising expectations for a sustainable future. J. Circ. Econ. 2023, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsholme, A.; Deutz, P.; Affolderbach, J.; et al. Negotiating stakeholder relationships in a regional circular economy: Discourse analysis of multi-scalar policies and company statements from the north of England. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2022, 2, 783–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, P.; Almeida, S.; Bengtsson, M.; Singh, R. Just transitions in circular economies: A global South perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 176, 106729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, F. C.; Pies, I. The circular economy growth machine: A critical perspective on “post-growth” and “pro-growth” circularity approaches. J. Ind. Ecol. 2024, 28, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulf Cooperation Council Secretariat General (GCC-SG). GCC Circular Economy Alliance Framework. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Industrial Development and Logistics Program (NIDLP). Industrial Symbiosis and Circular Economy: Strategic Framework for Sustainable Growth. 2022. Available online: https://www.nidlp.gov.sa (accessed on 2 January 2025).

-

29. King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (KAPSARC). Public perceptions of circular economy in Saudi Arabia. 2022.

- Suárez-Eiroa, B.; Fernández, E.; Méndez-Martínez, G.; Soto-Oñate, D. Operational principles of circular economy for sustainable development: Linking theory and practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J. Circular economy and growth: A critical review of ‘‘post-growth’’ circularity and a plea for a circular economy that grows. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 179, 106033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, A.; Metta, J.; Bakırlıog˘ lu, Y.; et al. Make it a circular city: Experiences and challenges from European cities striving for sustainability through promoting circular making. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 185, 106495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.; Cordella, M. Does circular economy mitigate the extraction of natural resources? Empirical evidence based on analysis of 28 European economies over the past decade. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 203, 107607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, L.; Grodach, C. Centrifugal circular cities: Mapping circular economy employment and accessibility in Melbourne, Australia. Urban Geography. Epub ahead of print. 5 July 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N. M. P.; Ritala, P.; Huotari, P. The circular economy—Exploring the introduction of the concept among S&P 500 firm. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 487–490. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Circulytics: Measuring Stakeholder Inclusivity in Circular Economy Transitions. 2019. Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Romero-Perdomo, F.; Carvajalino-Umaña, J. D.; López-González, M.; Ardila, N.; González-Curbelo, M. A. The private sector's role in Colombia to achieving the circular economy and the Sustainable Development Goals. DYNA 90, 9–16. [CrossRef]

- Awana, S.; Chavan, M.; Sedera, D.; Cheng, Z.; Ganzin, M. Unlocking circular start-ups: A model of barriers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J. Implementing the circular economy in the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area: The interplay between market actors mediated by transition brokers in. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2857–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J. Effective governance of circular economies: An international comparison. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 343, 130874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; Adams, K. T.; Giesekam, J.; Tingley, D. D.; Pomponi, F. Barriers and drivers in a circular economy: The case of the built environment. Procedia CIRP 2019, 80, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owojori, O. M.; Okoro, C. The private sector role as a key supporting stakeholder towards circular economy in the built environment: A scientometric and content analysis. Buildings 2022, 12, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleischwitz, R.; Yang, M.; Huang, B.; et al. The circular economy in China: Achievements, challenges and potential implications for decarbonisation. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 183, 106350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J. L.; Chiwenga, K. D.; Ali, K. Collaboration as an enabler for CE: A case study of a developing country. Manag. Decis. 2019, 59, 1784–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.; Kirchherr, J.; Raven, R.; Hekkert, M. Bottom-up dynamics in circular innovation systems: The perspective of circular start-ups. J. Ind. Ecol. 2024, 28, 320–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S. A.; Alkassim, R. S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Aswan University Journal of Environmental Studies 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W.; Clark, Plano V. L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research., 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F.; Black, W. C.; Babin, B. J.; Anderson, R. E. Multivariate Data Analysis., 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B. G.; Fidell, L. S. Using Multivariate Statistics., 7th ed.; Pearson, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S. DESA Working Paper No. 169; Beyond the Business Case: The Strategic Role of the Private Sector in Transforming the Real Economy towards an Inclusive, Green and Circular Future. DESA: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).