1. Introduction

Aedes mosquitoes (particularly

Aedes aegypti and

Aedes albopictus) are the primary vectors of dengue virus transmission, and transmission occurs through the bites of an infected female mosquito (

https://www.cdc.gov/dengue; Onen et al., 2023). These include researching sustainable mosquito control approaches that reduce negative environmental and human health effects, developing more potent vaccinations and antiviral medications, and comprehending the genetic variable that predisposes mosquitoes to the virus (Onen et al., 2023). Moreover, climate change’s impact on mosquito communities’ dynamics and disease transmission patterns is still insufficiently studied, highlighting it as an important field for future research (Onen et al., 2023; Jibon et al., 2024). Dengue fever (DF) and its more acute form, dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF), are driven by four closely related dengue serotypes (DENV 1 to DENV 4), highly infectious, positive-sense single-stranded RNA (+ssRNA) viruses from the

Flavivirus genus. A fifth serotype (DENV 5), identified in Malaysia in 2013, has not yet been reported in India as of 2025 and is not widely established. These viruses belong to the genus Flavivirus within the family Flaviviridae (Mustafa et al., 2015). Dengue viruses are endemic in tropical and subtropical climates, with the highest transmission rates occurring in densely populated urban and semi-urban regions. (Pourzangiabadi et al., 2025; Mustafa et al., 2025; Jibon et al., 2024). The World Health Organization (WHO) measures that annually, there are between 100 and 400 million cases of dengue infections worldwide (Akinsulie et al., 2024; Pourzangiabadi et al., 2025). Over the past few decades, DENV has emerged as a significant global epidemiological concern, with approximately half of humanity currently susceptible to infection (Akinsulie et al., 2024; Screaton et al., 2015; The Lancet 2013).

Unlike prior reviews that attention on specific aspects of DENV biology or control approaches, this review manuscript explores an integrative, India-centric overview of current epidemiological trends from 2018 to 2025. This study systematically integrates viral genomics, mosquito immunity and microbiome dynamics, host genetic susceptibility, nutritional influences, and emerging omics-driven vector control approaches. By integrating human, viral, and vector determinants within a single frame, this review sheds light on undetermined junctions, specifically the functions of the microbiome and nutrition in influencing disease severity. It offers a fundamental perspective important for both research progress and public health policy upgradation.

2. Global Burden and Growing Burden of the Dengue Virus

Many DENV cases are asymptomatic or cause relatively mild illness that can be self-managed (World Health Organization 2024; Mustafa et al., 2015). The true incidence of DENV infections is likely underreported, as many are underdiagnosed due to symptom overlap with other febrile diseases (Santos et al., 2023; Bhatt et al., 2013). The incidence of DENV has grown significantly (

Supplementary Figure S1), with reported cases to the WHO rising from 0.505 million in 2000 to 5.2 million in 2019, indicating a global increase in recent years (

Supplementary Figure S2) (World Health Organization 2024). Dengue is a growing health concern, affecting over 100 nations in the WHO regions, which include the Western Pacific Region (WPRO), Southeast Asia Region (SEARO), Africa Region (AFRO), Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO), and the Americas (AMRO). The Asia region carries approximately 70% of the global infection load (World Health Organization 2024). It is also spreading to new regions, including Europe, where significant outbreaks are emerging (World Health Organization 2023). France and Croatia are known to have local transmission of the infection for the first time in 2010 (World Health Organization 2023), and an increase in dengue virus transmission has also been reported through Afghanistan’s National Disease Surveillance and Response System (NDSR) (Tahoun et al., 2024). A significant rise in reported dengue cases has been observed in Vietnam (320,000), Bangladesh (101,000), and the Philippines (420,000), indicating a concerning regional trend (Khan et al., 2023; World Health Organization 2023). As of 2021, this illness countries to be a significant concern in India (

Supplementary Figure S3), Kenya, Paraguay, Colombia, Brazil, and the Cook Islands (Khan et al., 2023; World Health Organization 2023) (

Supplementary Figure S1).

3. India’s First Case to Global Control Research

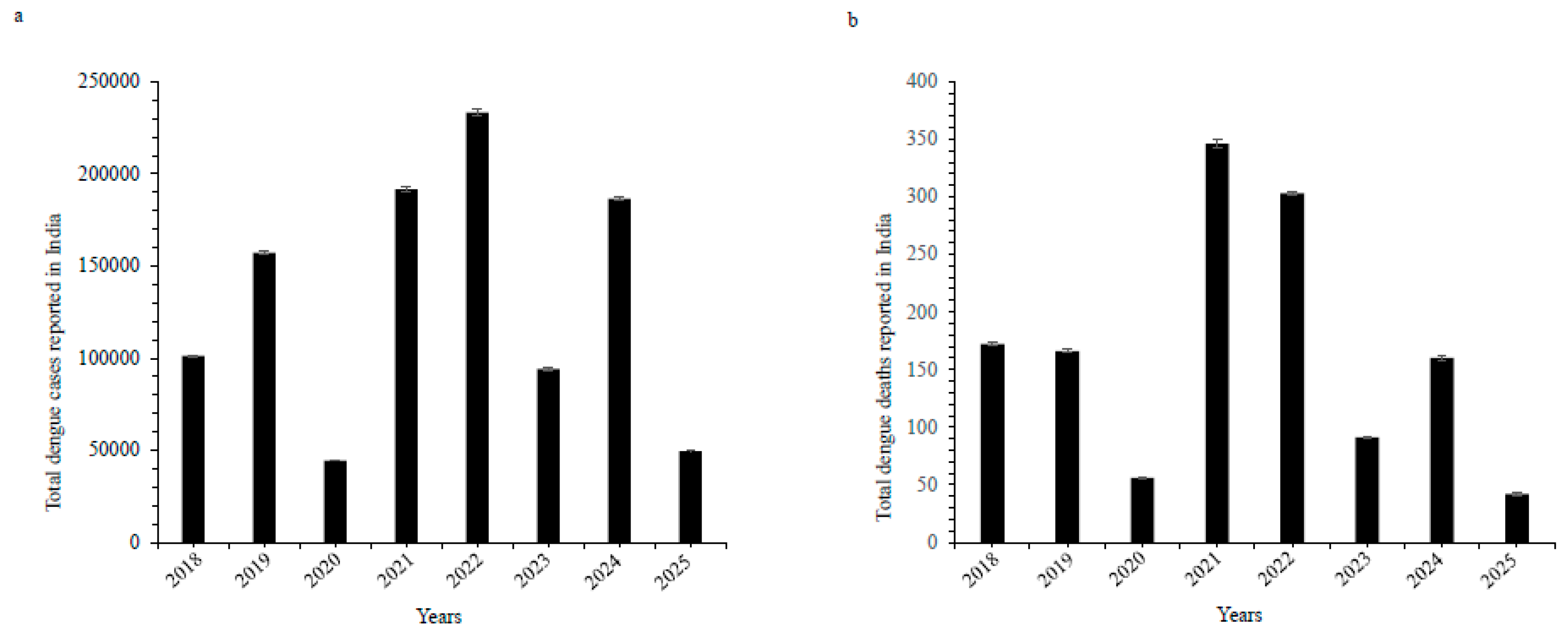

Supplementary Table S1a reveals the annual count of dengue cases and deaths reported between 2018 and 2025 across various Indian territories, according to the National Center for Vector Borne Diseases Control, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Over these 8 years (2018 to 2025), a total of 11,06,812 dengue cases and 1,149 deaths were noted (

Supplementary Table S1a,

Figure 1). In India, dengue cases increased (over 233,000) in 2022, followed by sharp fall in 2023 and again in 2025, revealing improved control strategy and reduction in transmission. Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu usually observed high numbers of cases, with Kerala also revealing a significant number of deaths, specifically in 2023 and 2024 (37 and 71 deaths respectively). Andhra Pradesh (with a high number of cases) has not shown any deaths over the period. Maharashtra showed an uncertain trend, with peaks in 2019 and 2023, while Bihar exhibited an increase in both cases and deaths, particularly in 2021. West Bengal had a sharp increase in 2022 with 67,271 cases. The year 2021 was the most affected overall, with 193,283 cases and 346 deaths, showing the serious dengue threat in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal. States such as Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, and Sikkim exhibited fewer numbers of cases, with no deaths in most years. Lakshadweep and Sikkim also had very less cases. However, the number of deaths was relatively less compared to the total number of cases, Kerala, Maharashtra, and Uttar Pradesh had significantly higher deaths. Overall, the data indicate that dengue remains a notable public health threat across multiple states in India. The standard error values for dengue cases varied from 314.88 to 1921.98 (p value < 0.00001), while for deaths, the values ranged from 0.699 to 3.26 (p value < 0.00001) (

Supplementary Table S1b).

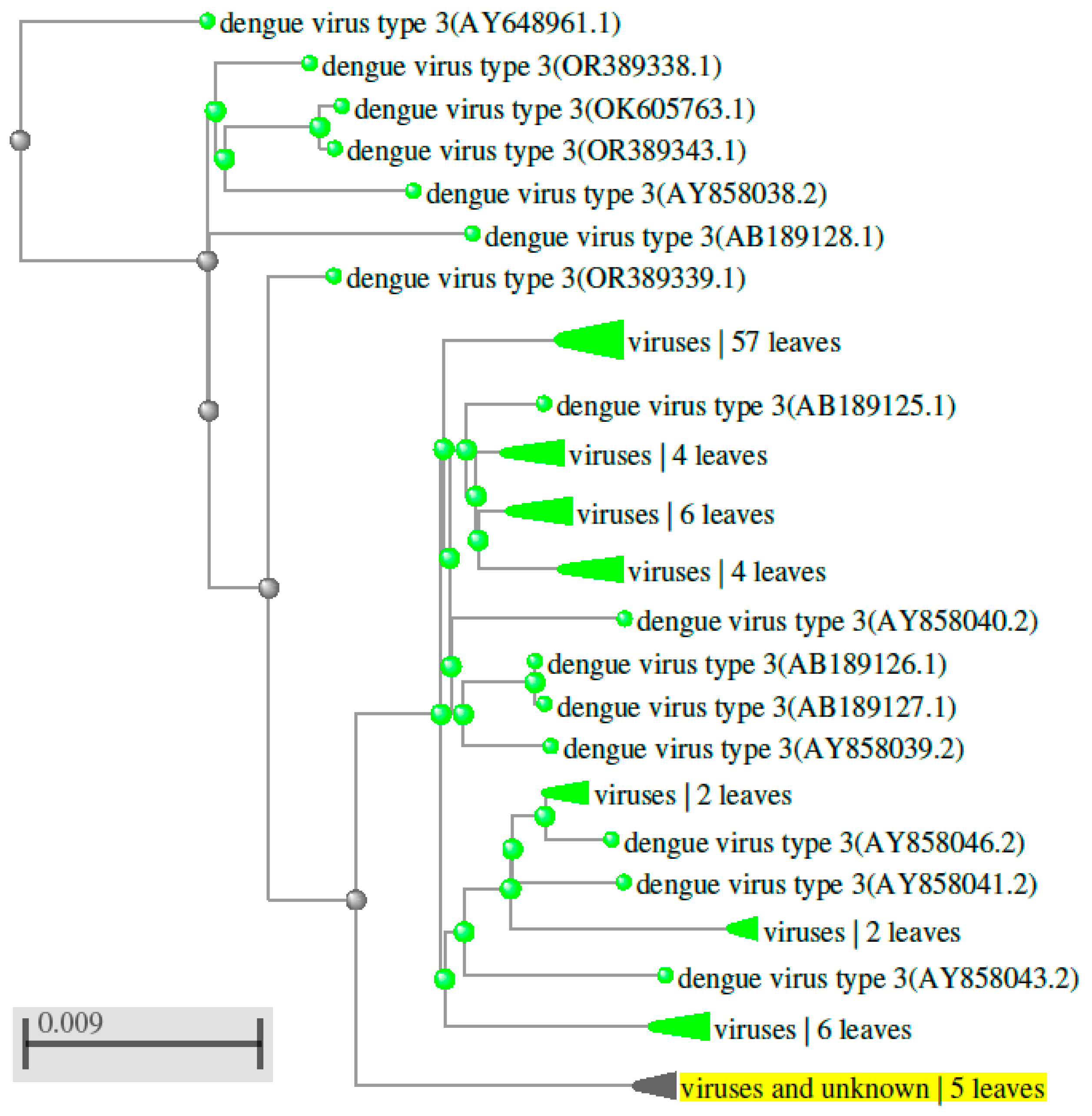

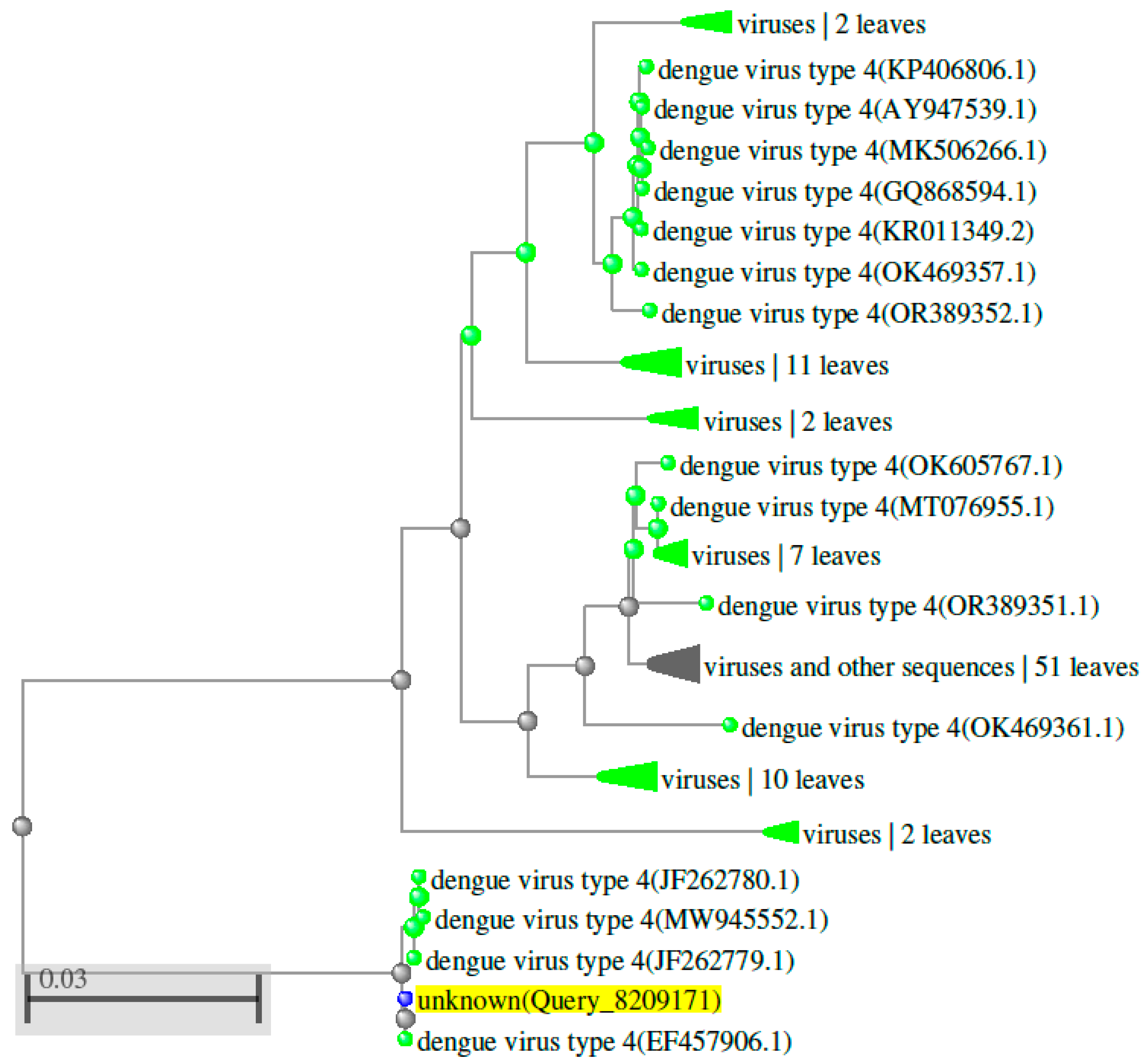

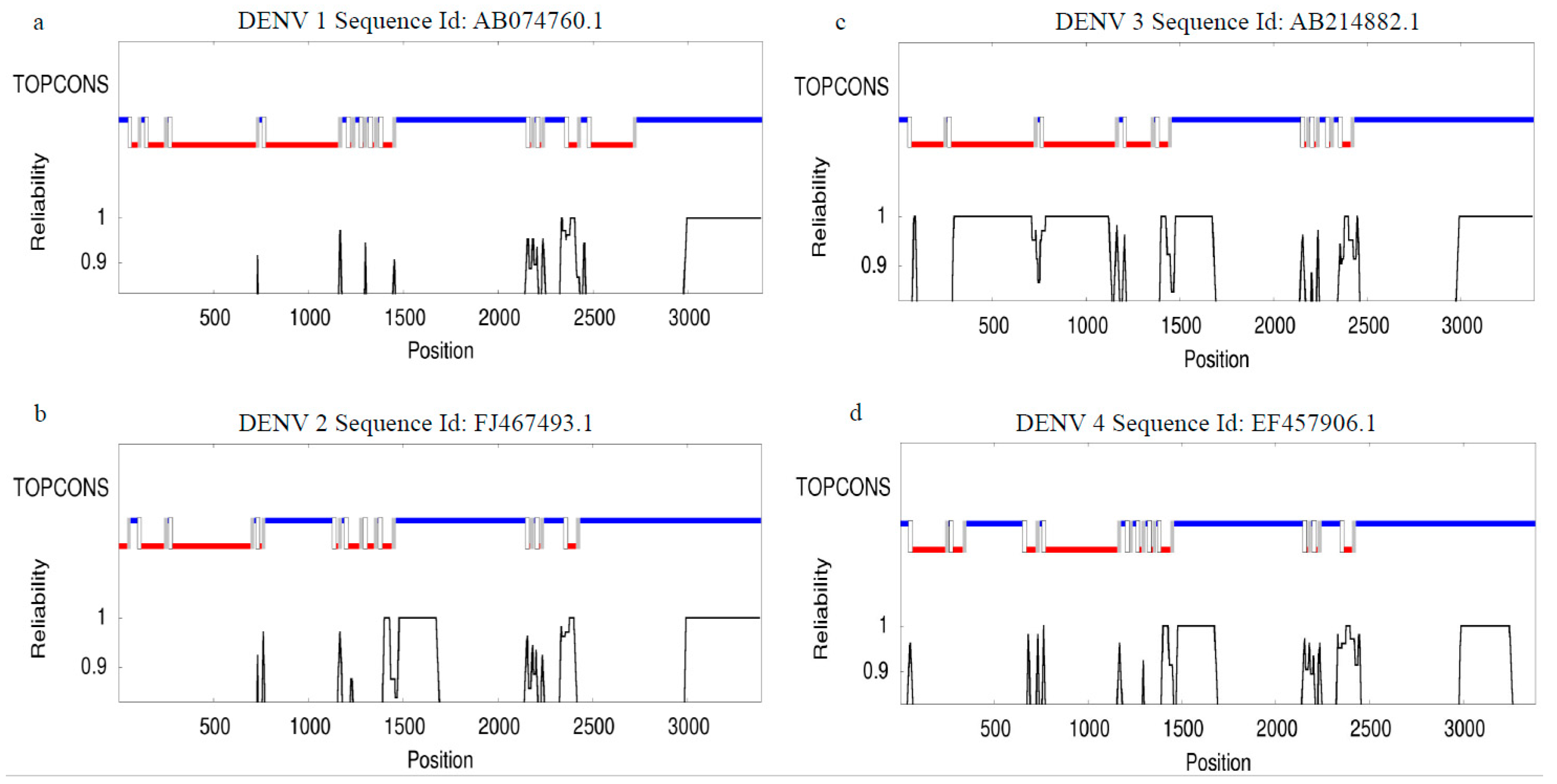

4. Genetic Diversity of the Dengue Virus

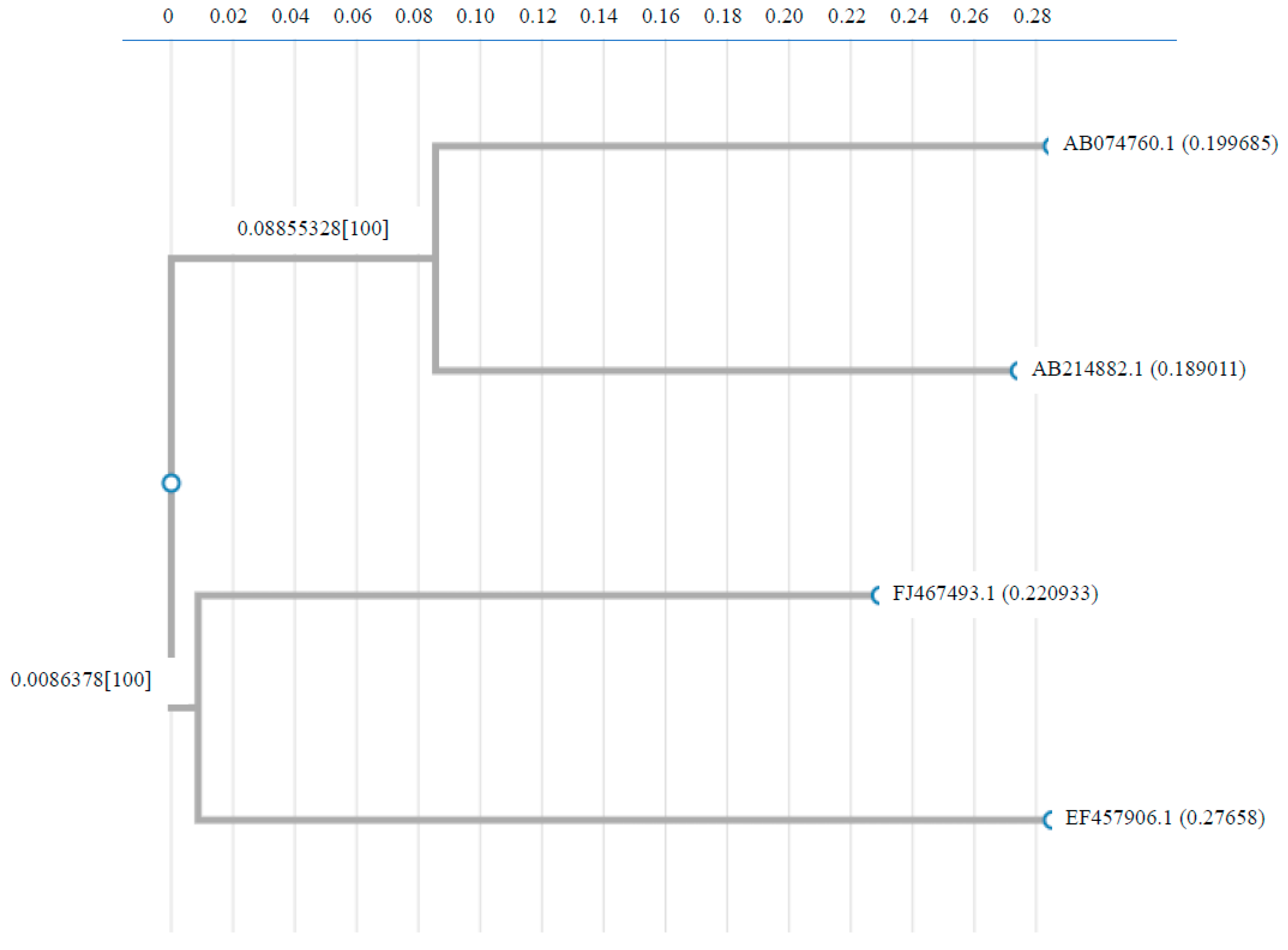

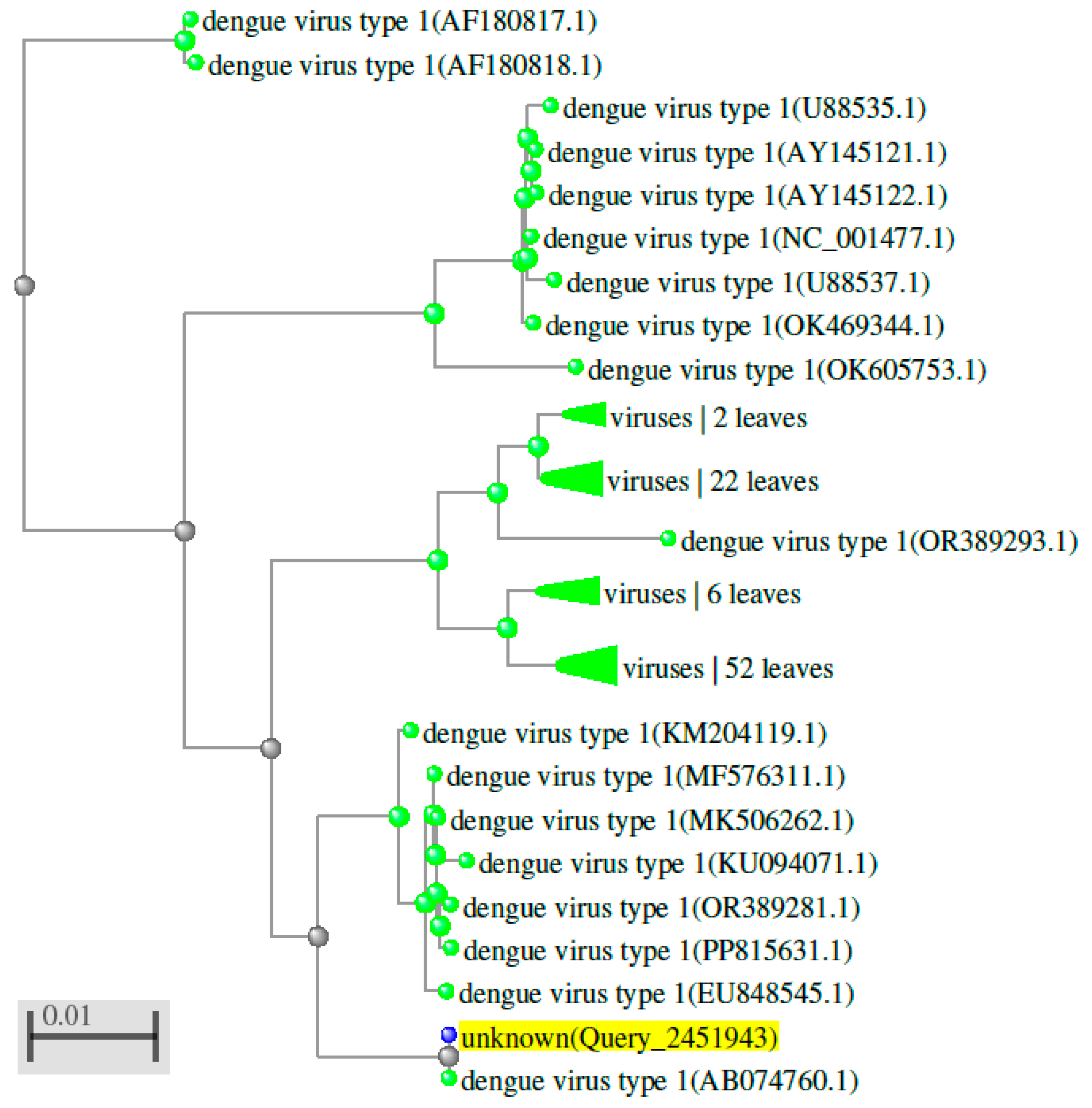

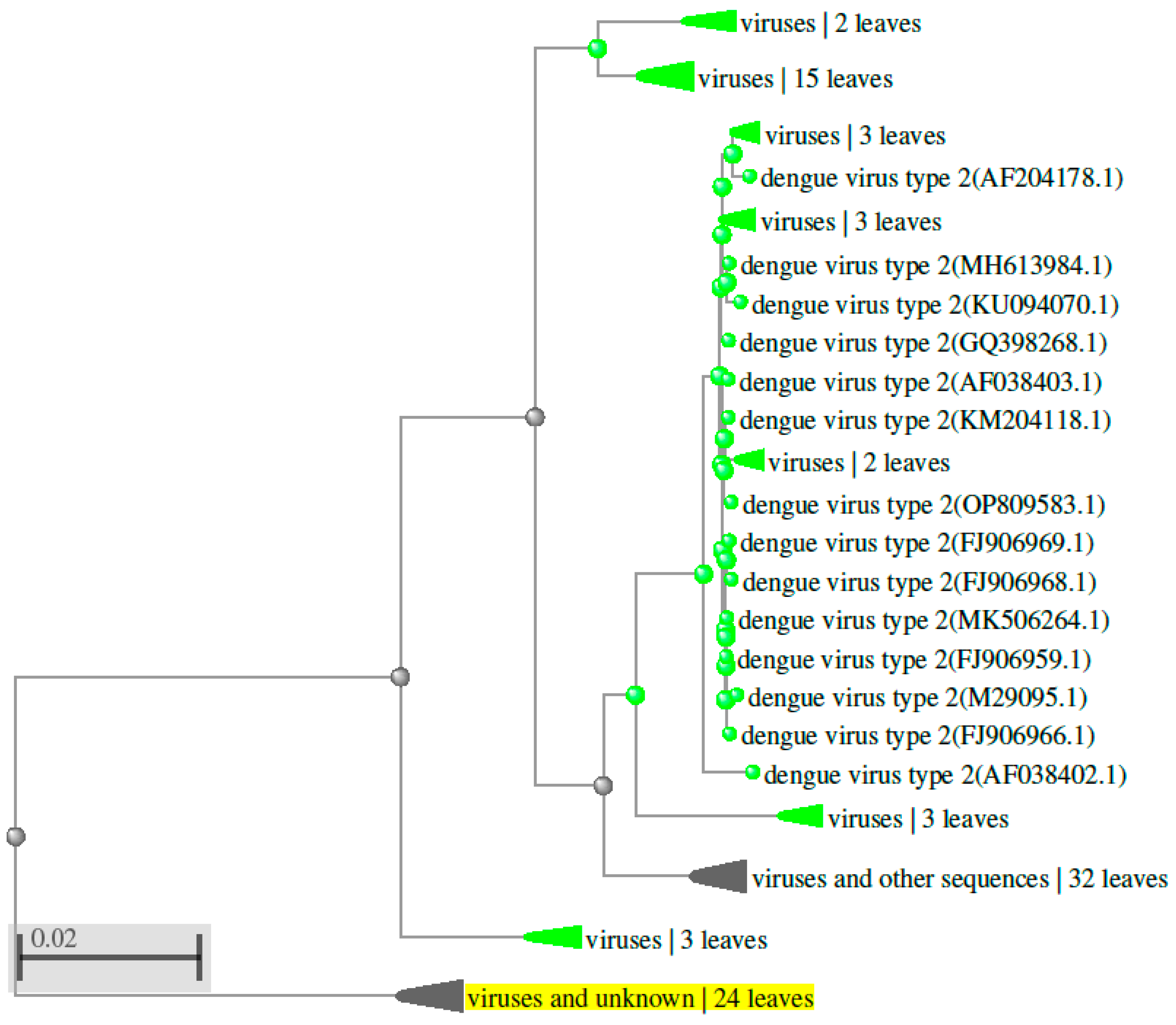

Over the last few years, the occurrence and terrestrial distribution of the dengue virus have increased drastically. This rise has likely been driven by climate change, urbanization, and greater mobility of humans (Sim et al., 2016). Dengue infection affects approximately 400 million people annually (Bhatt et al., 2013). Genetic study of dengue virus serotypes using sequences from the NCBI Nucleotide database, AB074760.1 (DENV 1), FJ467493.1 (DENV 2), AB214882.1 (DENV 3), and EF457906.1 (DENV 4), revealed distinct genetic relationships when aligned using Clustal W version 2.1 (

https://www.genome.jp/tools-bin/clustalw) (

Supplementary Table S2 and

Figure 2). The results indicate that DENV serotypes are distributed differently across geographic regions. Phylogenetic analysis, conducted using NCBI data and BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), showed that DENV 1, 2, 3, and 4 share approximately 59 - 67.6% of their genomic sequence (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 and

Supplementary Table S2). Despite these genetic differences, all four serotypes cause the same disease and lead to a similar set of symptoms. The TOPCONS server (

http://topc ons.cbr.su.se/) predicted the presence of a secretory signal sequence and transmembrane helices in dengue virus serotypes DENV 1 (Sequence ID: AB074760.1), DENV 2 (Sequence ID: FJ467493.1), DENV 3 (Sequence ID: AB214882.1), and DENV 4 (Sequence ID: EF457906.1). The analysis predicted the absence of a secretory signal sequence in all four serotypes, while transmembrane helices were detected in each (

Figure 7). Furthermore, the TOPCONS homology search did not identify any homologous transmembrane proteins in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (

Supplementary Figure S4). These findings help our understanding of the genetic evolution of the dengue virus. They are essential for tracking outbreaks, monitoring mutations, and aiding in vaccine development. Compared to the four main serotypes, DENV 5 appears to elicit a distinct antibody response and forms a separate evolutionary lineage. However, further study is required to prove this classification (Mustafa et al., 2015). Epidemiological studies suggest that different DENV genotypes and serotypes vary in their capacity to cause severe dengue fever. For example, the introduction of the Asian lineage of DENV 2 into the Americas has been linked to a major outbreak of DHF (Rico-Heesse 1990; Gubler 1998). Comparative genome sequencing has exhibited variations between the virulent Asian genotype, associated with DHF/DSS, and the less virulent American genotype (Leitmeyer et al., 1999). Notable differences include a substitution at amino acid position 390 in the envelope (E) protein and variations in the UTRs (5’ and 3’ untranslated regions), both of which influence viral replication efficiency (Cologna et al., 2003; Pryor et al., 2001). Furthermore, deep sequencing has revealed that intra-host genetic diversity of DENV varies across genomic regions. This diversity is shaped by host immune pressure and the virus’s replication fidelity (Sessions et al., 2015).

5. Mosquito Immunity and Genetics in Dengue Transmission

Upon infection, key innate immune pathways in mosquitoes, such as the Toll and JAK-STAT pathways, are activated and play a crucial role in restricting dengue (DENV) replication. These pathways, along with effector molecules like antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), form the first of defence against the virus (Xi et al., 2008; Souza-Neto et al., 2009). Mosquito strains vary in their vector competence for DENV, meaning their capability to secure, sustain, and transmit the virus. This variation is an additive genetic trait governed by multiple genes and loci (Bennett et al., 2002; Bosio et al., 2000). Additionally, the mosquito gut microbiome significantly influences DENV infection outcomes, certain bacterial species promote viral replication, while others inhibit it (Zhang et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2011).

6. Host Immune Response and Genetic Factors in Severe Dengue

In humans, the host immune response evolves throughout the course of infection. Early stages are characterized by interferon-mediated antiviral activity, which is later replaced by the activation of biosynthetic pathways (van de Weg et al., 2015). Severe symptoms, such as vascular leakage, may be linked to neutrophil activation, which contributes to endothelial damage (Popper et al., 2012; Devignot et al., 2010). Genetic studies have identified specific variants in the MICB and PLCE1 genes that are related with an increased threat of developing serious dengue infection (Khor et al., 2011; Vasanwala et al., 2014). These results emphasize the function of host genetic materials in influencing disease progression with severity.

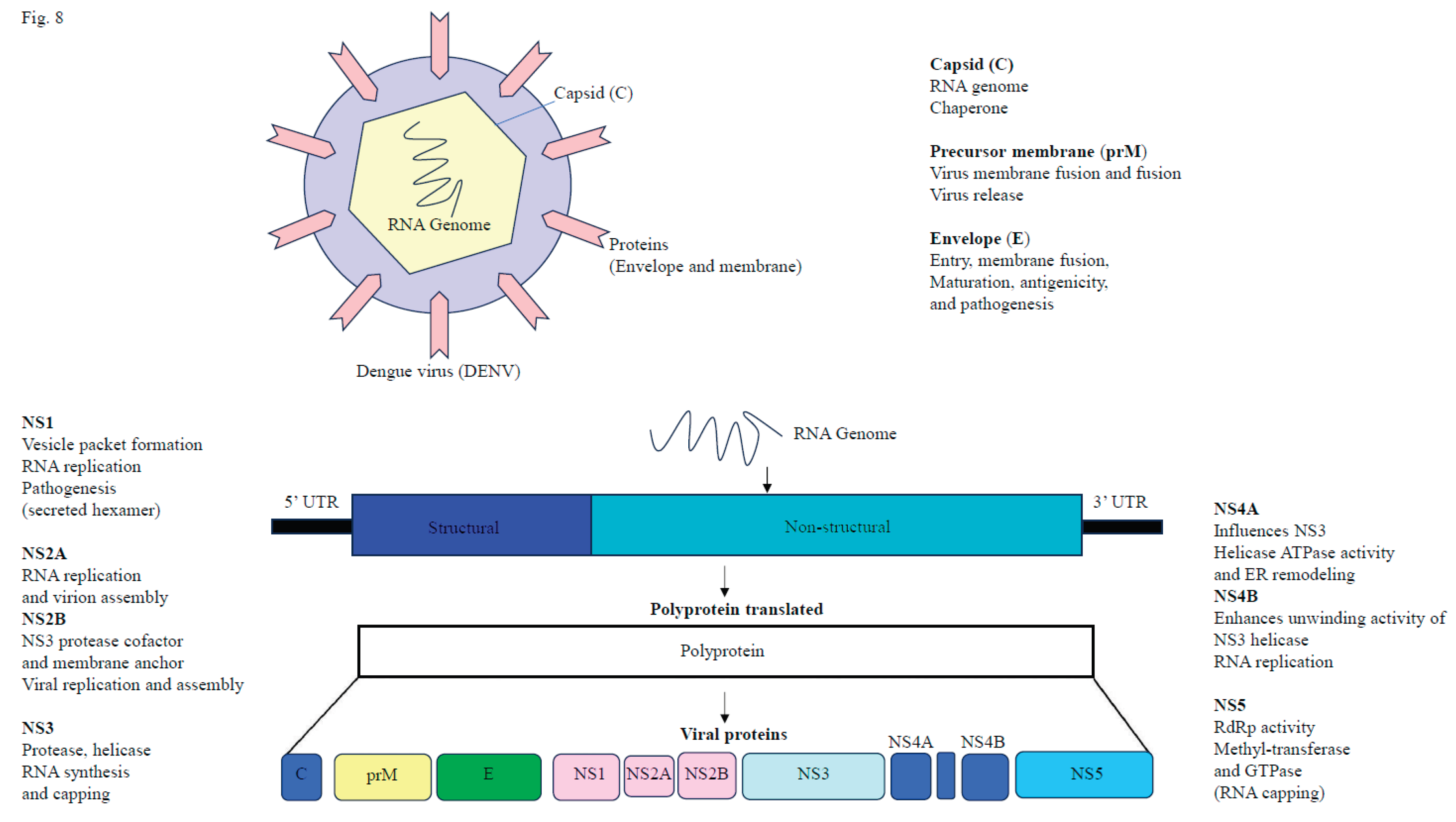

7. Dengue Virus Replication and Transmission in Mosquito Vectors

After the initial infection of the mosquito midgut (e.g.,

Aedes aegypti), DENV disseminates systemically via the hemocoel (body cavity) and eventually infects secondary tissues, containing the salivary glands. The sporogony period, typically 7-14 days at 25-30°C, refers to the time between the initial midgut infection and when the mosquito becomes capable of transmitting DENV (Choy et al., 2015). DENV binds to various cell surface receptors on mammalian cells (such as the mannose receptor, heparin sulfate, and DC-SIGN), enters the cell via receptor-mediated endocytosis, and subsequently releases its +ssRNA into the cytoplasm (Hidari et al., 2011). The DENV genome encodes a polyprotein, which is subsequently cleaved into ten proteins. These include three structural proteins (capsid, pre-membrane/membrane, envelope) involved in virus assembly and entry, and seven non-structural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5), which play roles in viral replication and immune evasion (

Figure 8) (Nanaware et al., 2021). Viral replication occurs through the formation of a membrane-bound replication complex, where the +ssRNA genome serves as a template to synthesize negative-sense RNA. This negative-sense RNA then generates multiple +ssRNA genomes for translation, replication, or packaging into new virions (Welsch et al., 2009; Westaway et al., 1999; Raquin et al., 2017). Several cellular factors and pathways, including the ubiquitin-proteasome system, Alix protein, and specific mosquito genes (e.g., CRVP379, Loqs2), play important functions in DENV replication and infection in both the vector and host (Londono-Renteria et al., 2015; Scott et al., 2003). The DENV non-structural protein NS4A interacts with host vimentin, localizing the replication complex to the perinuclear site, ensuring efficient viral RNA replication (Teo et al., 2014). Finally, DENV virions are released into the mosquito’s saliva and transmitted to the mammalian host during blood feeding (Islam et al., 2021).

8. Factors Influencing Dengue Virus Pathogenesis and Disease Severity

Dengue virus (DENV) pathogenesis arises from intricate interactions between viral components and host immunity, affected by genealogical factors. Several key mechanisms impart to the progression and disease severity, including antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), viral genetic variability, host immune responses, and underlying genetic predispositions (Bhatt et al., 2021). The clinical course of infection generally begins with DF, but in some cases, it may advance to major conditions, i.e. DHF or DSS (45-48). Factors implicated in severe disease include viral non-structural protein 1 (NS1), genomic variations among DENV serotypes, subgenomic flaviviral RNA (sfRNA), and cross-response, and ADE have been shown to exacerbate disease severity (Bhatt et al., 2021).

9. Association of the Gut Microbiome with Dengue Infection and Transmission

The gut microbiome has emerged as a key factor influencing host susceptibility to dengue virus (DENV) infection, a disease that affects millions globally each year (Shi et al., 2023). In patients who develop severe dengue, studies have reported an increased abundance of Proteobacteria, elevated serum endotoxin levels, and higher concentrations of bacterial-derived (1→3)-β-d-glucan (Chancharoenthana et al., 2022). These findings suggest that disruptions in gut microbial composition and intestinal barrier integrity may contribute to disease pathogenesis, potentially through microbial translocation into the bloodstream, a phenomenon more pronounced in severe cases than in milder febrile presentations. Moreover, elevated levels of anti-α-gal IgG and IgG1 antibodies have been associated with severe dengue outcomes (Olajiga et al., 2022). Although not directly linked to gut microbial composition, this observation highlights the complex interplay between host immunity and microbial antigens in modulating dengue severity. Experimental studies using germ-free mice or antibiotic-treated models have shown that the absence of gut microbiota can impair type 1 interferon responses, thereby increasing susceptibility to DENV infection (Mandal et al., 2021). This highlights the crucial role of the gut microbiome in shaping antiviral immune defences. In addition to its role in human hosts, the microbiome also influences DENV transmission through its impact on mosquito vectors. In Aedes aegypti, the primary vector for dengue, the endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia has been shown to reduce DENV replication and transmission potential. A study by Moreira et al. (2009) reported that Wolbachia infection significantly inhibits DENV infection in A. aegypti (Moreira et al., 2009). Furthermore, Wolbachia has also been shown to suppress replication of several clinically significant arboviruses, such as Zika, Chikungunya, and yellow fever viruses (Dutra et al., 2016; van den Hurk et al., 2012). Conversely, gut commensal bacteria in mosquitoes may enhance vector competence. Wu et al. (2019) reported that certain gut-associated microbes can promote susceptibility to arbovirus infections, including DENV, by modulating immune responses or creating a more permissive environment for viral replication (Wu et al., 2019). Additionally, microbial contributions to host nutrition, such as enhanced amino acid harvesting demonstrated in Drosophila by Yamada et al. (2015), may indirectly affect mosquito immunity and viral resistance capacity (Yamada et al., 2015). Together, these findings emphasize the dual role of the gut microbiome in both human hosts and mosquito vectors in modulating dengue virus pathogenesis and transmission dynamics.

10. Impact of Nutrition on Dengue Severity

Dengue infection shows a broad spectrum of symptoms, ranging from mild fever to serious life-threatening complications such as DHF and DSS. Among the various host-related factors influencing disease progression, nutritional status has been increasingly studied for its role in modulating disease severity (Trang et al., 2016). Some evidence suggests that malnutrition may be inversely linked with the development of more critical forms of dengue. For example, a meta-analysis reported that malnourished individuals had a reduced risk of developing DHF compared to those with normal nutrition status (the odds ratio [OR] was 0.71, with a 95% confidence interval [CI] of 0.56 to 0.90) (Kalayanarooj et al., 2005). However, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear and may alter immune responses in undernourished individuals. Conversely, obesity has been associated with increased dengue severity. In a study of 1,417 hospitalized adult dengue patients, approximately 23.5% were classified as obese (Chiu et al., 2023). Obesity is known to promote a state of chronic low-grade inflammation, which may influence the immune response during dengue infection, contributing to complications such as plasma leakage and organ dysfunction (Rathore et al., 2020). In dengue-endemic regions like India, the disease burden tends to peak during and after the monsoon season. Clinically, patients often present with fever, vomiting, dehydration, abdominal pain, and low platelet counts. While initial care is frequently managed at home, severe symptoms may require hospitalization for intravenous fluids and close monitoring. During the febrile phase, nutritional support and hydration are essential components of supportive care. Oral rehydration solutions, fresh fruit juices (particularly citrus), coconut water, and soups can help prevent dehydration and provide essential electrolytes. Lemon water is a source of vitamin C and may assist with antioxidant defense. Nutrition-rich fruits such as pomegranate, apple, and orange contribute to hydration and recovery. Homemade vegetable soups containing spinach, beetroot, and tomatoes offer vitamins and minerals that support immune function and tissue repair (Banerjee 2022; Mishra et al., 2017). Coconut water is particularly beneficial due to its high potassium content, while beetroot provides essential nutrients including vitamins A, B9, and C, as well as iron and manganese, which support erythropoiesis and help prevent anaemia (Mishra et al., 2017). Additionally, sweet lime (Mosambi) juice is rich in ascorbic acid, B vitamins, and polyphenols, which may have therapeutic benefits during dengue infection (Banerjee et al., 2021). Nutritional balance is especially important in children, as studies have shown that overweight or obese pediatric patients are at greater risk of severe plasma leakage. A recommended dietary composition for dengue recovery includes 50-55% carbohydrates, more than 1.0 g of protein/kilogram body mass, and 20-25% fats, along with adequate intake of vitamins, minerals, and electrolytes (Mishra et al., 2017). In countries like India, a wide variety of seasonal fruits and vegetables are available and serve as natural sources of essential micronutrients that support immune function and recovery (Banerjee 2020). Despite progress in understanding and managing, several challenges remain. Epidemiological data are often underreported or inconsistent, limiting accurate estimates of disease burden. Diagnostic tools that are both rapid and affordable are still lacking in many low-resource settings. Furthermore, long-term prevention is hindered by the absence of a universally accepted dengue vaccine, and vector control efforts are complicated by changing climate patterns and increasing resistance to insecticides.

11. Biomarkers and Genomic Advances in Dengue Diagnosis and Control

The identification of reliable biomarkers (

Supplementary Table S3) and the development of prognostic models are critical for the rapid detection of individuals exposed to dengue. These tools enable more targeted clinical management and support community-level prevention strategies in affected regions (Popper et al., 2012). Advances in genomics have opened new approaches for identifying therapeutic targets, which may aid in the creation of more potent vaccines and antiviral treatments. Additionally, mosquito transcriptomics studies have revealed gene expression changes in vector species such as

Aedes aegypti during dengue infection. These findings offer potential targets for innovative vector control strategies, including transgenic and transgenic or paratransgenic approaches aimed at disrupting virus replication or transmission within the mosquito host (Jupatanakul et al., 2014; Xiao et al., 2014; Hidari et al., 2011; Kang et al., 2014).

12. Challenges and Strategies for Dengue Control in India

Dengue remains a persistent and evolving public health challenge in India, driven by factors such as climate change, urbanization, and insufficient vector control measures. Despite advancements in diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities, the overall disease burden continues to rise. Effective dengue control requires strengthening community engagement, enhancing disease surveillance systems, and accelerating vaccine research and deployment. A sustainable solution demands a comprehensive, multi-sectoral approach that integrates public health, environmental management, and vector control strategies to mitigate the impact of dengue in India.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplementary Figure S1. Global distribution of dengue fever cases worldwide in 2024. Note: Source of figure: The Guardian (

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2024/oct/23/dengue-fever-record-cases-in-2024-so-far-what-is-driving-the-worlds-largest-outbreak). Supplementary Figure S2. Monthly global dengue fever cases (in millions) are showing a steep increase in 2024. ‘m’ represents million. Note: Source: The Guardian (

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2024/oct/23/dengue-fever-record-cases-in-2024-so-far-what-is-driving-the-worlds-largest-outbreak). Supplementary Figure S3. Geographic distribution of dengue cases in India. Note: Source: The Guardian (

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2024/oct/23/dengue-fever-record-cases-in-2024-so-far-what-is-driving-the-worlds-largest-outbreak). Supplementary Figure S4. Consensus prediction of dengue virus (DENV) membrane protein topology employing the TOPCONS web server indicated the absence of transmembrane helices (shown in red and blue in the graph) in the concluded amino acid sequence. The TOPCONS consensus topology was derived from five independent prediction algorithms: OCTOPUS, Philius, PolyPhobius, SCAMPI, and SPOCTOPUS. The ZPRED algorithms estimated the Z-coordinate, representing the distance of each amino acid residue from the membrane center, while the G-scale provided the predicted free energy of membrane insertion for a sliding window of amino acids centered at each sequence position. Results are shown for (a) dengue virus serotypes DENV 1 (Sequence ID: AB074760.1), (b) DENV 2 (Sequence ID: FJ467493.1), (c) DENV 3 (Sequence ID: AB214882.1), and (d) DENV 4 (Sequence ID: EF457906.1). Supplementary Table S1. Annual dengue cases and deaths reported in Indian states and Union territories (2018 - 2025). (a) Chronological trends in dengue cases and related deaths across Indian states and Union territories from 2018 to 2025. The data reveals a peak in cases in 2022, followed by a short fall in successive years, highlighting improved control measures. Instability among states shows differences in outbreak severity, control, and competence. ‘NR’ shows data not reported for the respective years. (b) The standard error values for dengue cases varied from 314.88 to 1921.98 (p value < 0.00001), while for deaths, the values ranged from 0.699 to 3.26 (p value < 0.00001). Supplementary Table S2. Comparative genetic analysis of dengue virus serotypes using NCBI sequences and Clustal W alignment. Supplementary Table S3. Comprehensive summary of molecular and metabolic biomarkers associated with Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever and Severe Dengue.

Authors Contributions

A.O. conceptualized, conceived, and planned the review. T.K. and A.O. conducted the literature review and wrote the manuscript. A.G. and P.G. contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscript. A.O. was responsible for project administration, supervision, writing, reviewing and editing, and visualisation.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This article does not contain any studies on human or vertebrate animal subjects.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

References

- Akinsulie, O.C.; Ibrahim, I. Global re-emergence of dengue fever: The need for a rapid response and surveillance. The Microbe 2024, 4, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. The essence of Indian indigenous knowledge in the perspective of ayurveda, nutrition, and yoga. Res. Rev. Biotechnol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. Importance of proper nutrition in dengue infections. J Nutr Metab Health Sci. 2022, 5(4), 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Pal, S.R. Inhibitory and complementary therapeutic effect of sweet lime (Citrus limetta) against RNA-viruses. J Prev Med Holist Health 2021, 7(1), 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, K.E.; Olson, K.E.; Muñoz-Mde, L.; Fernandez-Salas, I.; Farfan-Ale, J.A.; Higgs, S.; Black, W.C.; Beaty, B.J. Variation in vector competence for dengue 2 virus among 24 collections of Aedes aegypti from Mexico and the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002, 67(1), 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.; Sabeena, S.P.; Varma, M.; Arunkumar, G. Current Understanding of the Pathogenesis of Dengue Virus Infection. Curr Microbiol. 2021, 78(1), 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.; Gething, P.W.; Brady, O.J.; Messina, J.P.; Farlow, A.W.; Moyes, C.L.; Drake, J.M.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hoen, A.G.; Sankoh, O.; et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 2013, 496(7446), 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosio, C.F.; Fulton, R.E.; Salasek, M.L.; Beaty, B.J.; Black, W.C. Quantitative trait loci that control vector competence for dengue-2 virus in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Genetics 2000, 156(2), 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dengue [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/dengue.

- Chancharoenthana, W.; Kamolratanakul, S.; Ariyanon, W.; Thanachartwet, V.; Phumratanaprapin, W.; Wilairatana, P.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Abnormal Blood Bacteriome, Gut Dysbiosis, and Progression to Severe Dengue Disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022, 12, 890817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.Y.; Lin, C.Y.; Yu, L.S.; Wang, W.H.; Huang, C.H.; Chen, Y.H. The association of obesity and dengue severity in hospitalized adult patients. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2023, 56(2), 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, M.M.; Sessions, O.M.; Gubler, D.J.; Ooi, E.E. Production of Infectious Dengue Virus in Aedes aegypti Is Dependent on the Ubiquitin Proteasome Pathway. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015, 9(11), e0004227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cologna, R.; Rico-Hesse, R. American genotype structures decrease dengue virus output from human monocytes and dendritic cells. J Virol. 2003, 77(7), 3929–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devignot, S.; Sapet, C.; Duong, V.; Bergon, A.; Rihet, P.; Ong, S.; Lorn, P.T.; Chroeung, N.; Ngeav, S.; Tolou, H.J.; et al. Genome-wide expression profiling deciphers host responses altered during dengue shock syndrome and reveals the role of innate immunity in severe dengue. PLoS ONE 2010, 5(7), e11671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, H.L.; Rocha, M.N.; Dias, F.B.; Mansur, S.B.; Caragata, E.P.; Moreira, L.A. Wolbachia Blocks Currently Circulating Zika Virus Isolates in Brazilian Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes. Cell Host Microbe 2026, 19(6), 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubler, D.J. Dengue and dengue heerhagic fever. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998, 11, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Srivastava, S.; Jain, A.; Chaturvedi, U.C. Dengue in India. Indian J Med Res. 2012, 136(3), 373–390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hidari, K.I.; Suzuki, T. Dengue virus receptor. Trop Med Health 2011, 39, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Quispe, C.; Herrera-Bravo, J.; Sarkar, C.; Sharma, R.; Garg, N.; Fredes, L.I.; Martorell, M.; Alshehri, M.M.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; et al. Production, Transmission, Pathogenesis, and Control of Dengue Virus: A Literature-Based Undivided Perspective. Biomed Res Int. 2021, 4224816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibon, M.J.N.; Ruku, S.M.R.P.; Islam, A.R.M.T.; Khan, M.N.; Mallick, J.; Bari, A.B.M.M.; Senapathi, V. Impact of climate change on vector-borne diseases: Exploring hotspots, recent trends and future outlooks in Bangladesh. Acta Trop. 2024, 259, 107373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jupatanakul, N.; Sim, S.; Dimopoulos, G. Aedes aegypti ML and Niemann-Pick type C family members are agonists of dengue virus infection. Dev Comp Immunol. 2014, 43(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalayanarooj, S.; Nimmannitya, S. Is dengue severity related to nutritional status? Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2005, 36(2), 378–384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Shields, A.R.; Jupatanakul, N.; Dimopoulos, G. Suppressing dengue-2 infection by chemical inhibition of Aedes aegypti host factors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014, 8(8), e3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.B.; Yang, Z.S.; Lin, C.Y.; Hsu, M.C.; Urbina, A.N.; Assavalapsakul, W.; Wang, W.H.; Chen, Y.H.; Wang, S.F. Dengue overview: An updated systemic review. J Infect Public Health 2023, 16(10), 1625–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khor, C.C.; Chau, T.N.; Pang, J.; Davila, S.; Long, H.T.; Ong, R.T.; Dunstan, S.J.; Wills, B.; Farrar, J.; Van Tram, T.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility loci for dengue shock syndrome at MICB and PLCE1. Nat Genet. 2011, 43(11), 1139–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitmeyer, K.C.; Vaughn, D.W.; Watts, D.M.; Salas, R.; Villalobos, I.; de, C.; Ramos, C.; Rico-Hesse, R. Dengue virus structural differences that correlate with pathogenesis. J Virol. 1999, 73(6), 4738–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Londono-Renteria, B.; Troupin, A.; Conway, M.J.; Vesely, D.; Ledizet, M.; Roundy, C.M.; Cloherty, E.; Jameson, S.; Vanlandingham, D.; Higgs, S.; et al. Dengue Virus Infection of Aedes aegypti Requires a Putative Cysteine Rich Venom Protein. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11(10), e1005202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, R.K.; Denny, J.E.; Namazzi, R.; Opoka, R.O.; Datta, D.; John, C.C.; Schmidt, N.W. Dynamic modulation of spleen germinal center reactions by gut bacteria during Plasmodium infection. Cell Rep. 2021, 35(6), 109094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Agrahari, K.; Shah, D.K. Prevention and control of dengue by diet therapy. Int J Mosq Res. 2017, 4, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, L.A.; Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I.; Jeffery, J.A.; Lu, G.; Pyke, A.T.; Hedges, L.M.; Rocha, B.C.; Hall-Mendelin, S.; Day, A.; Riegler, M.; et al. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell. 2009, 139(7), 1268–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.S.; Rasotgi, V.; Jain, S.; Gupta, V. Discovery of fifth serotype of dengue virus (DENV-5): A new public health dilemma in dengue control. Med J Armed Forces India 2015, 71(1), 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanaware, N.; Banerjee, A.; Mullick Bagchi, S.; Bagchi, P.; Mukherjee, A. Dengue Virus Infection: A Tale of Viral Exploitations and Host Responses. Viruses 2021, 13(10), 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olajiga, O.M.; Maldonado-Ruiz, L.P.; Fatehi, S.; Cardenas, J.C.; Gonzalez, M.U.; Gutierrez-Silva, L.Y.; Londono-Renteria, B.; Park, Y. Association of dengue infection with anti-alpha-gal antibodies, IgM, IgG, IgG1, and IgG2. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 1021016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onen, H.; Luzala, M.M.; Kigozi, S.; Sikumbili, R.M.; Muanga, C.K.; Zola, E.N.; Wendji, S.N.; Buya, A.B.; Balciunaitiene, A.; Viškelis, J.; et al. Mosquito-borne diseases and their control strategies: An overview focused on green synthesized plant-based metallic nanoparticles. Insects 2023, 14(3), 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popper, S.J.; Gordon, A.; Liu, M.; Balmaseda, A.; Harris, E.; Relman, D.A. Temporal dynamics of the transcriptional response to dengue virus infection in Nicaraguan children. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012, 6(12), e1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourzangiabadi, M.; Najafi, H.; Fallah, A.; Goudarzi, A.; Pouladi, I. Dengue virus: Etiology, epidemiology, pathobiology, and developments in diagnosis and control - A comprehensive review. Infect Genet Evol. 2025, 127, 105710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryor, M.J.; Carr, J.M.; Hocking, H.; Davidson, A.D.; Li, P.; Wright, P.J. Replication of dengue virus type 2 in human monocyte-derived macrophages: Comparisons of isolates and recombinant viruses with substitutions at amino acid 390 in the envelope glycoprotein. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001, 65(5), 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raquin, V.; Lambrechts, L. Dengue virus replicates and accumulates in Aedes aegypti salivary glands. Virology 2017, 507, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, A.P.; Farouk, F.S.; St John, A.L. Risk factors and biomarkers of severe dengue. Curr Opin Virol. 2020, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Hesse, R. Molecular evolution and distribution of dengue viruses type 1 and 2 in nature. Virology 1990, 174, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.Y.; Tuboi, S.; de Jesus Lopes de Abreu, A.; Abud, D.A.; Lobao Neto, A.A.; Pereira, R.; Siqueira, J.B., Jr. A machine learning model to assess potential misdiagnosed dengue hospitalization. Heliyon 2023, 9(6), e16634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.W.; Morrison, A. Aedes aegypti density and the risk of dengue-virus transmission. Frontis 2003, 2, 187–206. [Google Scholar]

- Screaton, G.; Mongkolsapaya, J.; Yacoub, S.; Roberts, C. New insights into the immunopathology and control of dengue virus infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015, 15(12), 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessions, O.M.; Wilm, A.; Kamaraj, U.S.; Choy, M.M.; Chow, A.; Chong, Y.; Ong, X.M.; Nagarajan, N.; Cook, A.R.; Ooi, E.E. Analysis of dengue virus genetic diversity during human and mosquito infection reveals genetic constraints. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015, 9(9), e0004044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Yu, X.; Cheng, G. Impact of the microbiome on mosquito-borne diseases. Protein Cell. 2023, 14(10), 743–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, S.; Hibberd, M.L. Genomic approaches for understanding dengue: Insights from the virus, vector, and host. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Neto, J.A.; Sim, S.; Dimopoulos, G. An evolutionary conserved function of the JAK-STAT pathway in anti-dengue defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106(42), 17841–17846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahoun, M.M.; Sahak, M.N.; Habibi, M.; Ahadi, M.J.; Rasoly, B.; Shivji, S.; Aboushady, A.T.; Nabeth, P.; Sadek, M.; Abouzeid, A. Strengthening event-based surveillance (EBS): A case study from Afghanistan. Confl Health 2024, 18(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, C.S.; Chu, J.J. Cellular vimentin regulates construction of dengue virus replication complexes through interaction with NS4A protein. J Virol. 2014, 88, 1897–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet. Dengue-an infectious disease of staggering proportions. Lancet 2013, 381, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, N.T.H.; Long, N.P.; Hue, T.T.M.; Hung, L.P.; Trung, T.D.; Dinh, D.N.; Luan, N.T.; Huy, N.T.; Hirayama, K. Association between nutritional status and dengue infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2016, 16, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Weg, C.A.; van den Ham, H.J.; Bijl, M.A.; Anfasa, F.; Zaaraoui-Boutahar, F.; Dewi, B.E.; Nainggolan, L.; van IJcken, W.F.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Martina, B.E.; et al. Time since onset of disease and individual clinical markers associate with transcriptional changes in uncomplicated dengue. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015, 9(3), e0003522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Hurk, A.F.; Hall-Mendelin, S.; Pyke, A.T.; Frentiu, F.D.; McElroy, K.; Day, A.; Higgs, S.; O’Neill, S.L. Impact of Wolbachia on infection with chikungunya and yellow fever viruses in the mosquito vector Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012, 6(11), e1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasanwala, F.F.; Thein, T.L.; Leo, Y.S.; Gan, V.C.; Hao, Y.; Lee, L.K.; Lye, D.C. Predictive value of proteinuria in adult dengue severity. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014, 8(2), e2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Gilbreath, T.M.; Kukutla, P.; Yan, G.; Xu, J. Dynamic gut microbiome across life history of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae in Kenya. PLoS ONE 2011, 6(9), e24767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, S.; Miller, S.; Romero-Brey, I.; Merz, A.; Bleck, C.K.; Walther, P.; Fuller, S.D.; Antony, C.; Krijnse-Locker, J.; Bartenschlager, R. Composition and three-dimensional architecture of the dengue virus replication and assembly sites. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5(4), 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westaway, E.G.; Khromykh, A.A.; Mackenzie, J.M. Nascent flavivirus RNA colocalized in situ with double-stranded RNA in stable replication complexes. Virology 1999, 258, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Dengue and severe dengue. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue.

- World Health Organization. Scientists in Tahiti prepare to release sterilized mosquitoes to control dengue. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/16-05-2023-scientists-in-tahiti-prepare-to-release-sterilized-mosquitoes-to-control-dengue.

- World Health Organization. Dengue and severe dengue. World Health Organization. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue.

- Wu, P.; Sun, P.; Nie, K.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, M.; Xiao, C.; Liu, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, T.; Chen, X.; et al. A gut commensal bacterium promotes mosquito permissiveness to Arboviruses. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25(1), 101–112.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z.; Ramirez, J.L.; Dimopoulos, G. The Aedes aegypti toll pathway controls dengue virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4(7), e1000098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Pang, X.; Wang, P.; Cheng, G. Complement-related proteins control the flavivirus infection of Aedes aegypti by inducing antimicrobial peptides. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10(4), e1004027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, R.; Deshpande, S.A.; Bruce, K.D.; Mak, E.M.; Ja, W.W. Microbes promote amino acid harvest to rescue undernutrition in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2015, 10(6), 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Hussain, M.; O’Neill, S.L.; Asgari, S. Wolbachia uses a host microRNA to regulate transcripts of a methyltransferase, contributing to dengue virus inhibition in Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013, 110(25), 10276–10281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |