1. Introduction

After an actual learning episode, newly encoded information is gradually transferred into long-term memory. This consolidation process allows recently acquired memory traces to be stabilized and/or reinforced [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Sleep is known to contribute offline consolidation [

5,

6]. In particular, slow-wave sleep (SWS) plays a critical role in the consolidation of hippocampus-dependent spatial and declarative memories [

3,

7,

8]. SWS provides a period of minimal external interference, during which neurophysiological mechanisms coordinating slow oscillations, spindles and ripples favor the spontaneous reactivation of memory traces in this offline state [

3,

7,

9,

10,

11,

12].

There are also conditions during wakefulness when cognitive input is minimized, and the brain at least partially enters an offline mode. Brief periods of quiet wakeful rest following learning have been shown to enhance ulterior memory performance, presumably by reducing ongoing learning practice interference, allowing offline processing mechanisms to develop [

13,

14,

15]. Neural activity observed during wakeful rest has been suggested to resemble some aspects of sleep-like reactivation[

16,

17], and may thus benefit memory consolidation. However, findings are inconsistent with some studies reporting strong benefits and others no measurable effects [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. These discrepancies suggest that rest may support consolidation under specific conditions only, highlighting the need to determine not only whether those pauses are beneficial, but also when they are most effective in the learning process. On these premises, it can be hypothesized that the effectiveness of offline pauses depends on the time point at which the learner disengages from encoding. During prolonged wakefulness, increasing sleep pressure leads to reduced alertness and a decline in performance [

23,

24,

25], a phenomenon explained in the framework of the Borbély’s Process S component of sleep regulation, in which accumulation of sleep pressure corresponds to a rising homeostatic load that increases the likelihood of slow-wave expression during sleep [

23]. Expanding to sustained cognitive activity, theoretical accounts proposed that local neural fatigue within task-relevant networks may trigger transient offline states during wakefulness, a phenomenon referred as local sleep [

26,

27,

28,

29]. Local sleep was associated with slow-wave activity (SWA) in the delta range (0.5–4 Hz) and reduced behavioral performance [

27,

30,

31,

32]. During post-training sleep, SWA locally increases in brain regions engaged during learning, and greater SWA was found to predict enhanced memory performance the following day [

6,

31].

Although elevated SWA may be considered a neural state that favors consolidation, its presence during wakefulness is usually viewed as behaviorally detrimental, being associated with attentional lapses, slower responses and increased error rates [

27,

28,

29,

30,

32,

33,

34]. Local build-up of homeostatic sleep pressure has also been proposed a key mechanism in triggering mind-wandering (MW) [

27,

35], defined as a shift of attention away from the ongoing task toward internally directed thought. Accordingly, the occurrence of MW was correlated to attentional lapses, increased error rates and SWA [

36,

37,

38,

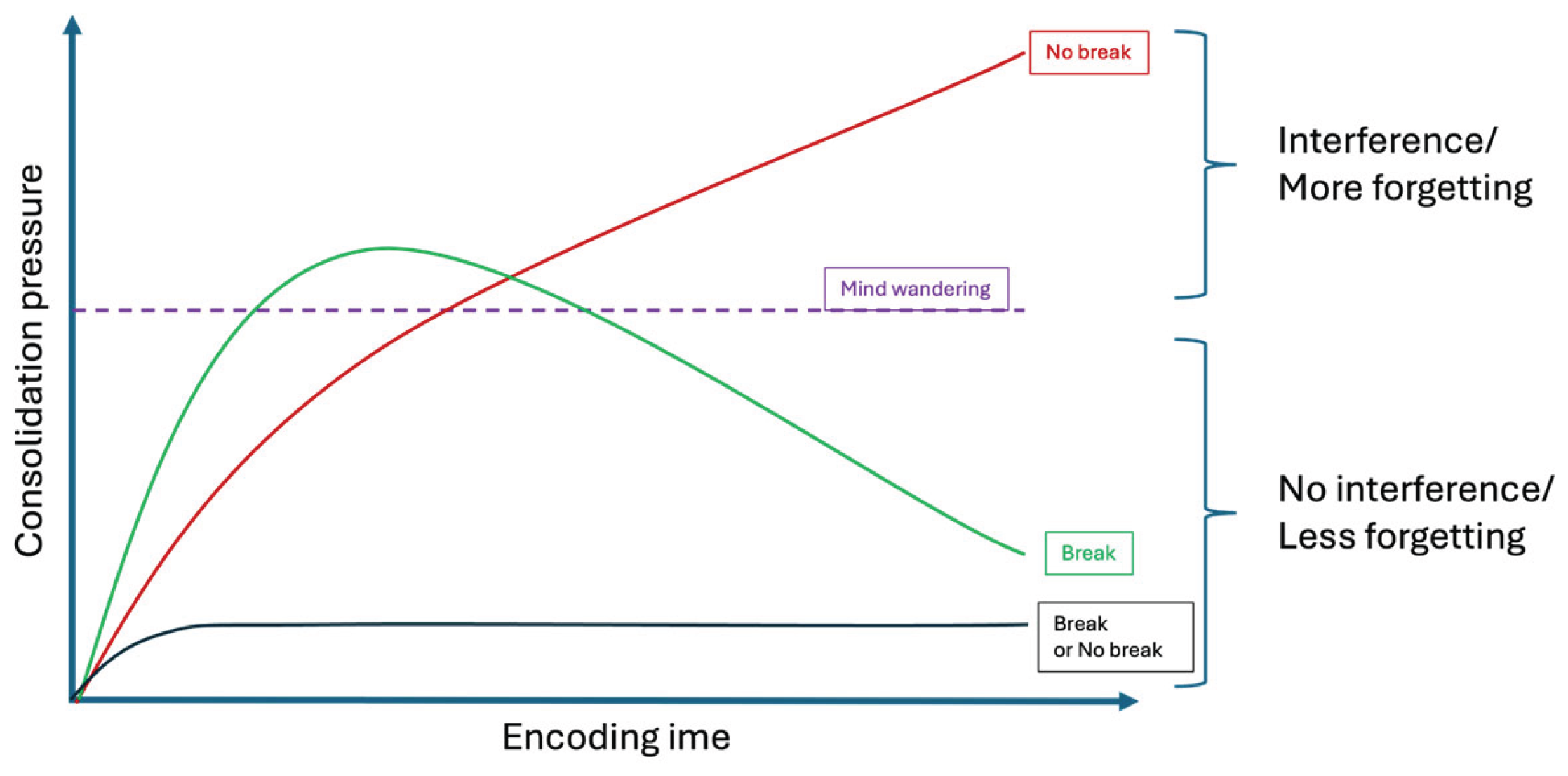

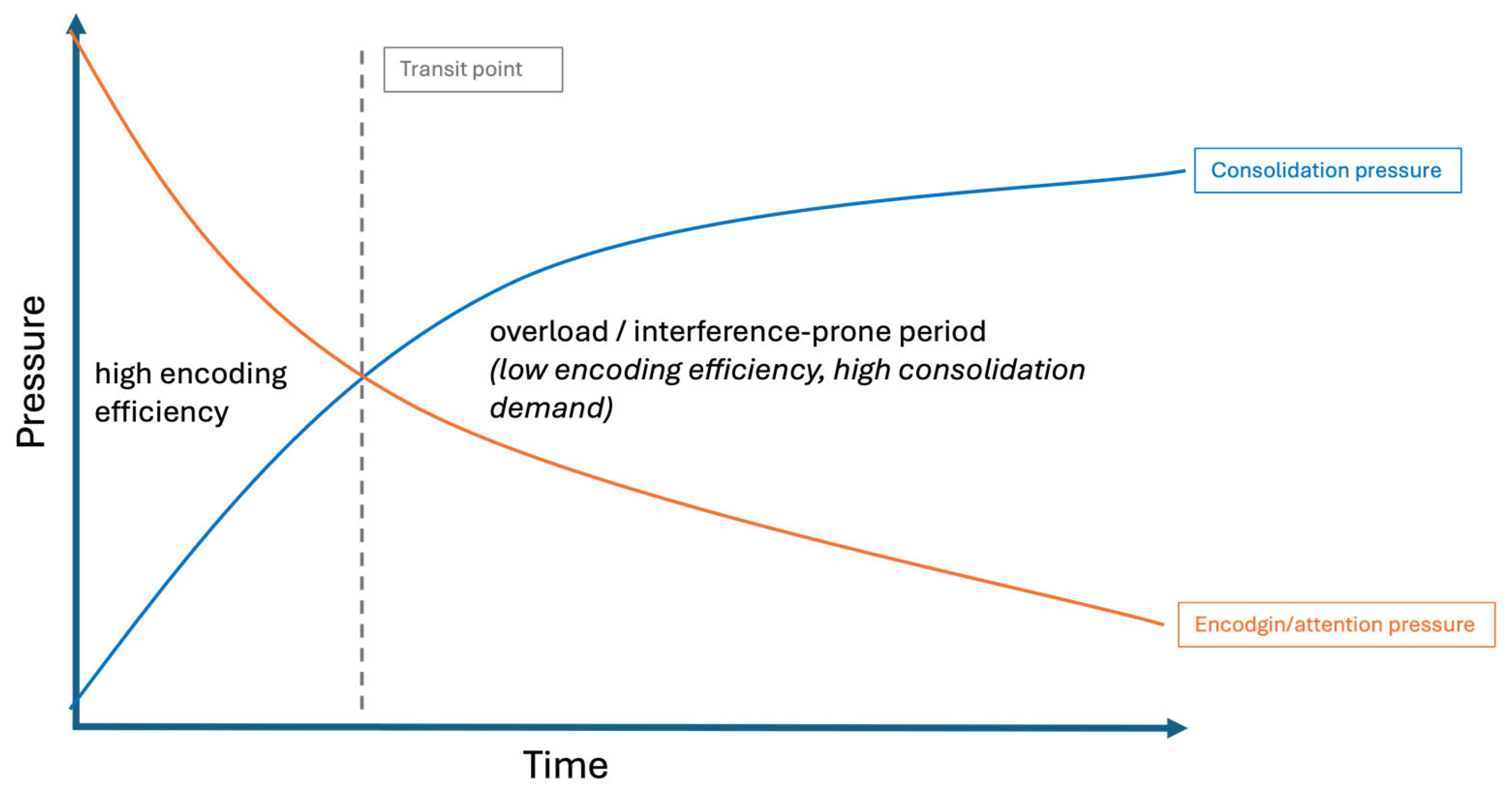

39]. In this respect, MW can also be viewed as a correlate of local sleep–like need and promote an off-line learning mode that would be beneficial for memory consolidation mechanisms. Hence, MW may reflect moments when local sleep need increases and encoding efficiency declines. Building on this framework, we hypothesized that sustained encoding would generate increasing consolidation demands (in other words, a consolidation pressure

) such that continuing to input new information would eventually become less efficient than briefly disengaging (see

Figure 1). In a nutshell, we propose that a transient offline disengagement state emerges when consolidation pressure increases over a specific threshold. If, at this point, learning continues, consolidation pressure will continue rising and impair performance. If, on the contrary, a break is provided when disengagement manifests (e.g. through increased MW), it will relieve consolidation pressure, both restoring learning capabilities and allowing memory consolidation mechanisms to unfold during the break.

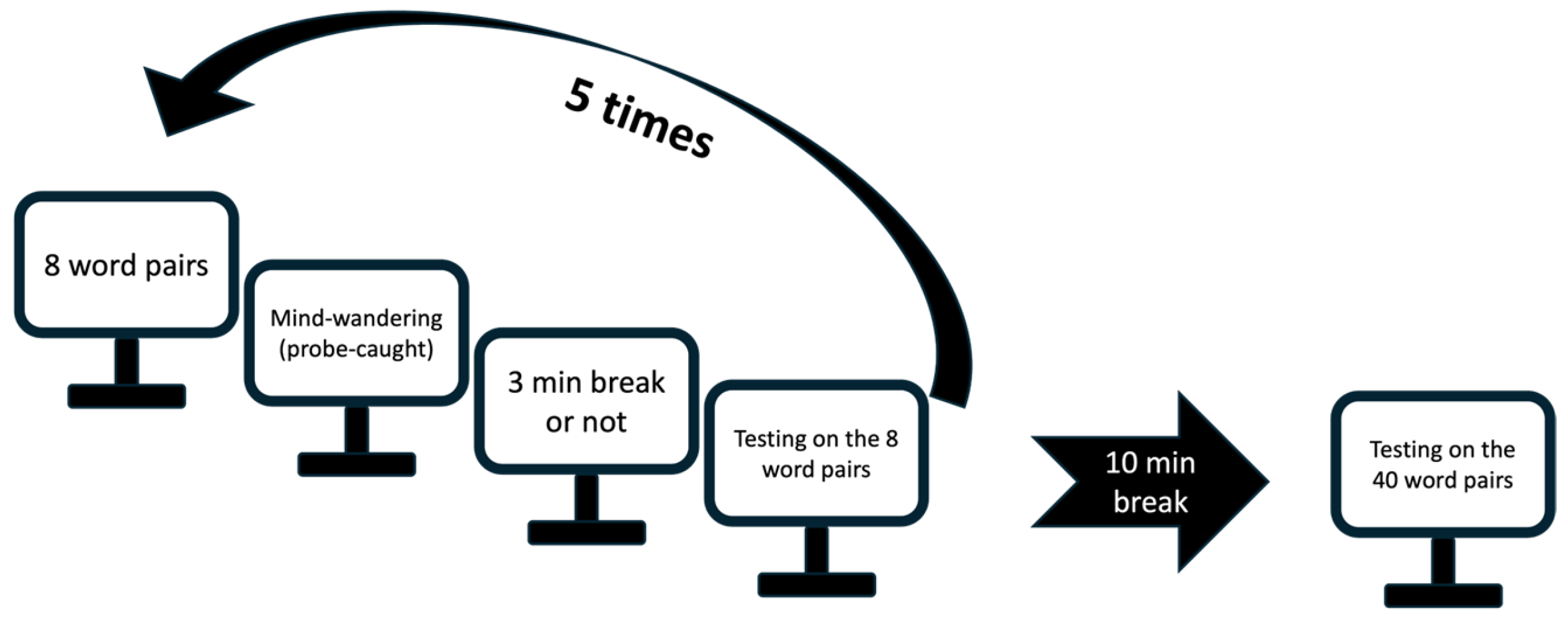

To test this hypothesis, we used a paired-associate learning paradigm with probe-caught MW thoughts sampling (

Figure 2) across two successive experiments. In Experiment 1, we tested whether pauses introduced immediately after MW reports during the learning phase improved memory at delayed recall as compared to a continued encoding condition. Experiment 2 tested whether MW-associated pause benefits were genuinely specific to MW by comparing pauses following MW versus pauses following focused-attention episodes (see

Section 4 for methodological details).

2. Results

2.1. Study 1

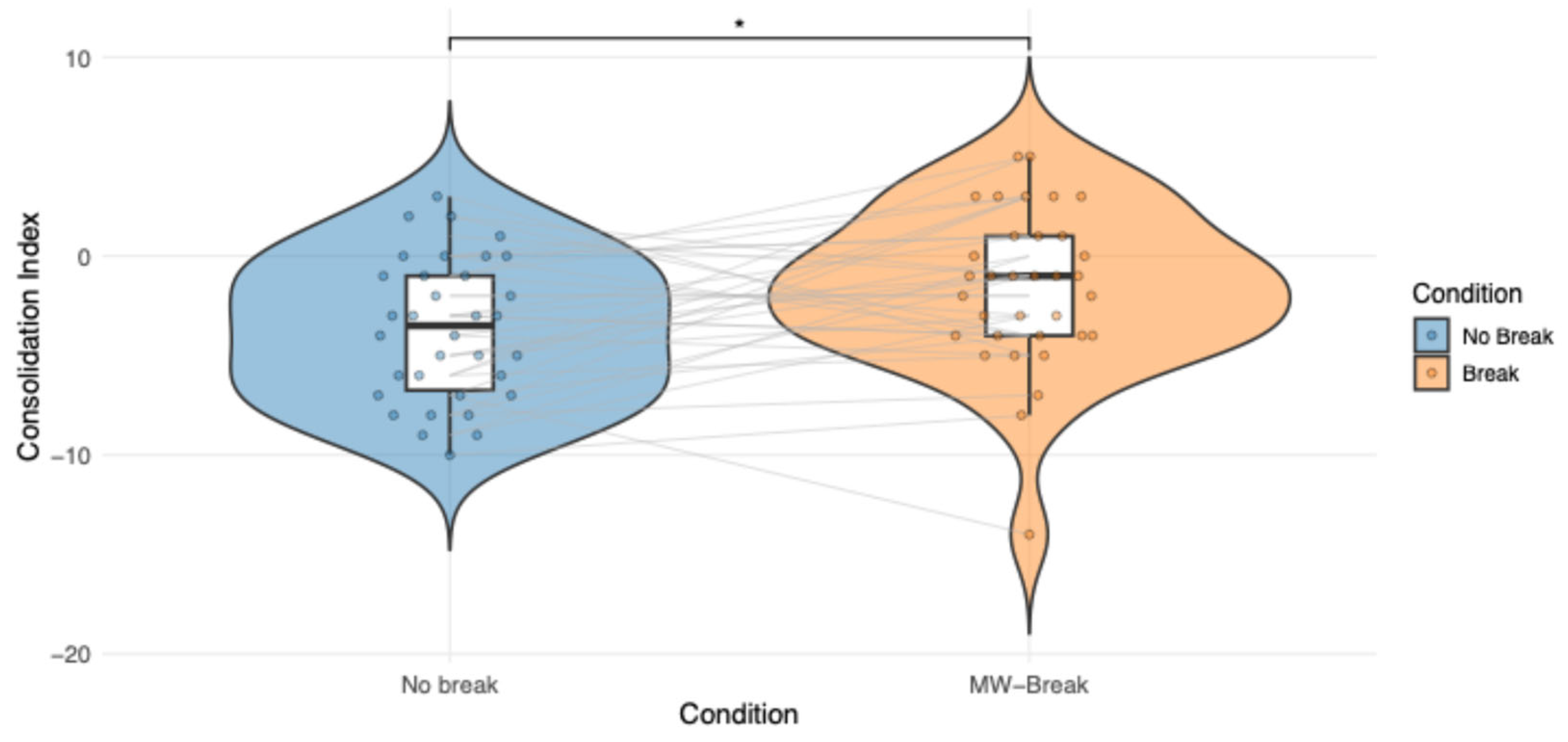

We tested in a final sample of 34 young healthy participants who were administered both experimental conditions whether introducing a pause immediately after a probe-caught mind-wandering (MW) report would improve delayed recall as compared to the continued learning condition (see section 4.1.1 Study 1). Memory consolidation was quantified computing a consolidation index (i.e., delayed recall total score minus immediate recall total score).

2.1.1. Break Following Mind-Wandering vs. Continued Learning

To assess whether a break following MW enhances memory consolidation, data were analyzed using a linear mixed-effects model with the experimental Condition (

No break vs MW-Break) as the predictor of interest (see section

4.3.1 Model specification). The analysis was computed on 68 observation (N 34 * 2 Conditions). The model revealed a significant Condition effect on the consolidation index (

β = 2.24,

SE = 0.88,

t(31) = 2.56,

p = .016, 95% CI [0.52, 3.96]) with a higher consolidation score when a pause was administered immediately after a MW report (

Figure 3). To ensure that the observed effect of the Condition was not driven by model specification, we conducted two complementary analyses. First, we fitted a reduced model including Condition only, without covariates, which yielded an effect of Condition comparable in direction and magnitude to that observed in the full model (

Appendix A.1;

Table A1). Second, we performed a likelihood ratio test comparing the full model with an otherwise identical model excluding Condition. This analysis showed that the inclusion of Condition significantly improved model fit (

χ² (1) = 6.85,

p = .009; see

Appendix A.2;

Table A2). Bayesian linear mixed-effects analyses yielded results consistent with the frequentist approach, showing a positive effect of

Condition on the consolidation index (

β = 2.17, 95% CrI [0.5, 3.86]). The Bayes factor provided positive evidence in favor of the alternative hypothesis relative to the null hypothesis of no effect (BF₁₀ ≈ 4.08), using weakly informative priors.

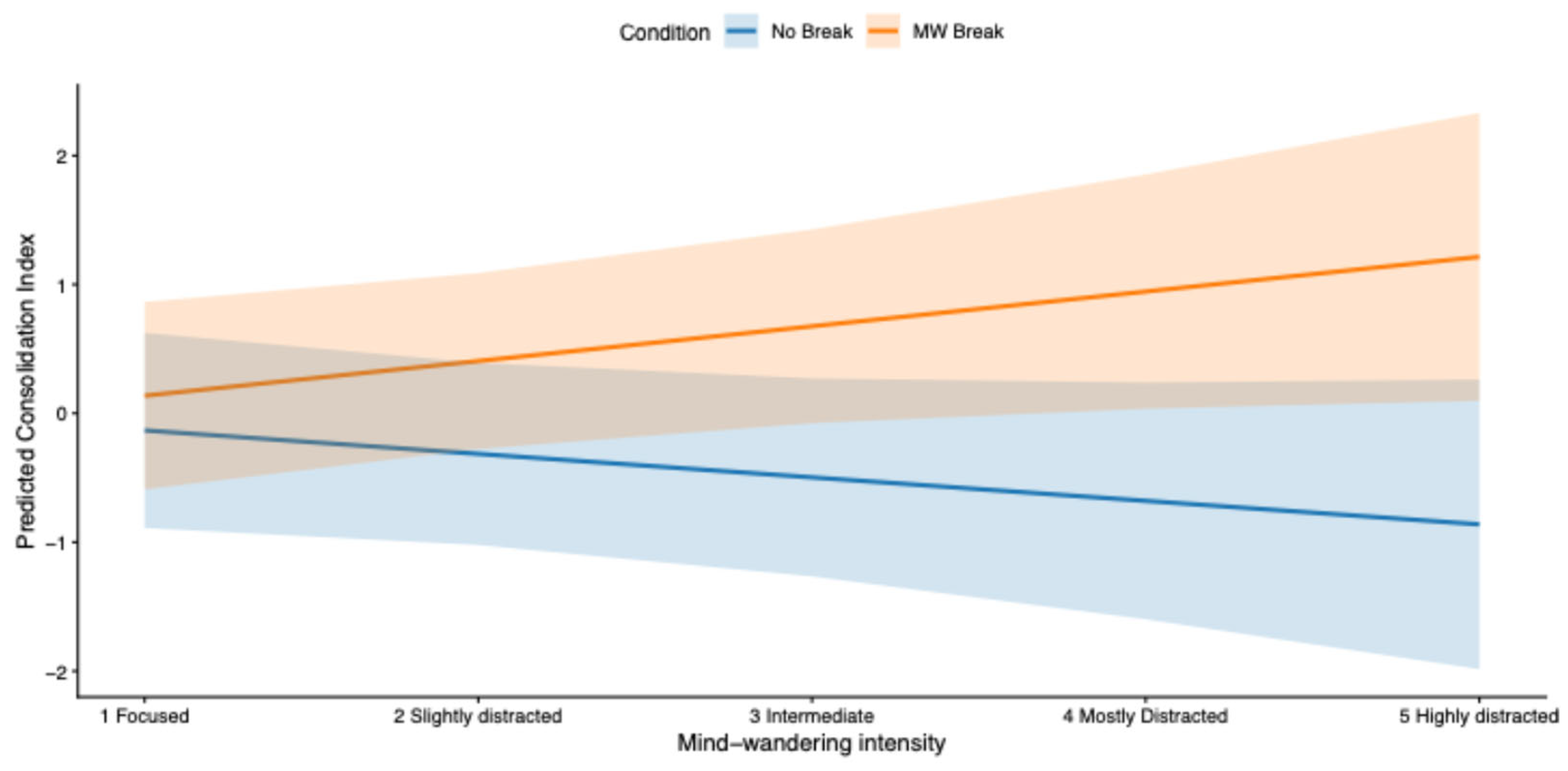

2.1.2. Moderation by the Mind-Wandering Intensity

To test whether mind-wandering intensity moderated the effect of experimental Condition, we restricted the analysis to the blocks in which breaks were implemented (blocks 2–4) and fitted a linear mixed-effects model with the interaction between Condition (

No break vs. MW break) and mind-wandering intensity (1 = focused, 2 = mostly focused, 3 = intermediate, 4 = mostly distracted, 5 = highly distracted). Mind-wandering intensity was treated as a continuous variable, based on the hypothesis that it reflects the proportion of local sleep need. For each block, the consolidation index was computed as the difference between delayed and immediate recall scores within the same block (e.g., delayed recall in block 3 minus immediate recall in block 3). The analysis was computed on 204 observations (N 34 * 3 blocks * 2 conditions). The model highlighted a significant effect of the interaction

Condition x Intensity on the consolidation index (

β = 0.45,

SE = 0.19,

t(188) = 2.35,

p = .02, 95% CI [0.07, 0.83]); indicating that the beneficial effect of MW breaks increased with higher levels of mind-wandering (

Figure 4).

Consistent with the interaction reported above, exploratory post hoc contrasts based on estimated marginal means indicated that the benefit of MW-triggered breaks increased with higher levels of mind-wandering intensity. No reliable difference between MW-Break and No-Break Conditions was observed at the lowest level of mind wandering, whereas progressively larger benefits of MW-Breaks emerged at intermediate and high levels of mind wandering (

Appendix B, Table B1).

2.1.3. Interim Discussion

Study 1 results showed that allowing a pause immediately after a MW report improves delayed memory recall, which was impacted by the intensity of the mind-wandering. These results are seemingly on agreement with our hypothesis that providing a short quiet rest opportunity when disengagement manifests through a MW report would relieve the accumulated pressure, both restoring learning capabilities and allowing memory consolidation mechanisms to unfold. However, a limitation of the experimental design of Study 1, directly comparing a MW-related break condition to a continued encoding with no break condition, is that it does not allow to disentangle whether the observed memory consolidation benefit in the MW-related break condition is specifically due to the occurrence of MW (and putatively local sleep) or merely to the quiet rest opportunity and decreased external input irrespective of the participant's attentional state, i.e. mind wandering or focused on the task. To test this alternative possibility, we conducted Study 2. The experimental protocol was identical to Study 1 for the mind-wandering (MW) condition, with a pause allowed when participants reported MW after blocks 2, 3 or 4. In the focused-attention (FA) condition, participants were allowed a pause after blocks 2, 3 or 4 when participants reported being focused on the learning task (i.e. not mind wandering).

2.2. Study 2

We tested in a final sample of 19 young healthy participants who were administered both experimental conditions whether introducing a pause immediately after a probe-caught mind-wandering (MW) report would improve delayed recall as compared to a pause allowed after a focused attention report. Memory consolidation was again quantified computing the consolidation index (i.e., delayed recall total score minus immediate recall total score).

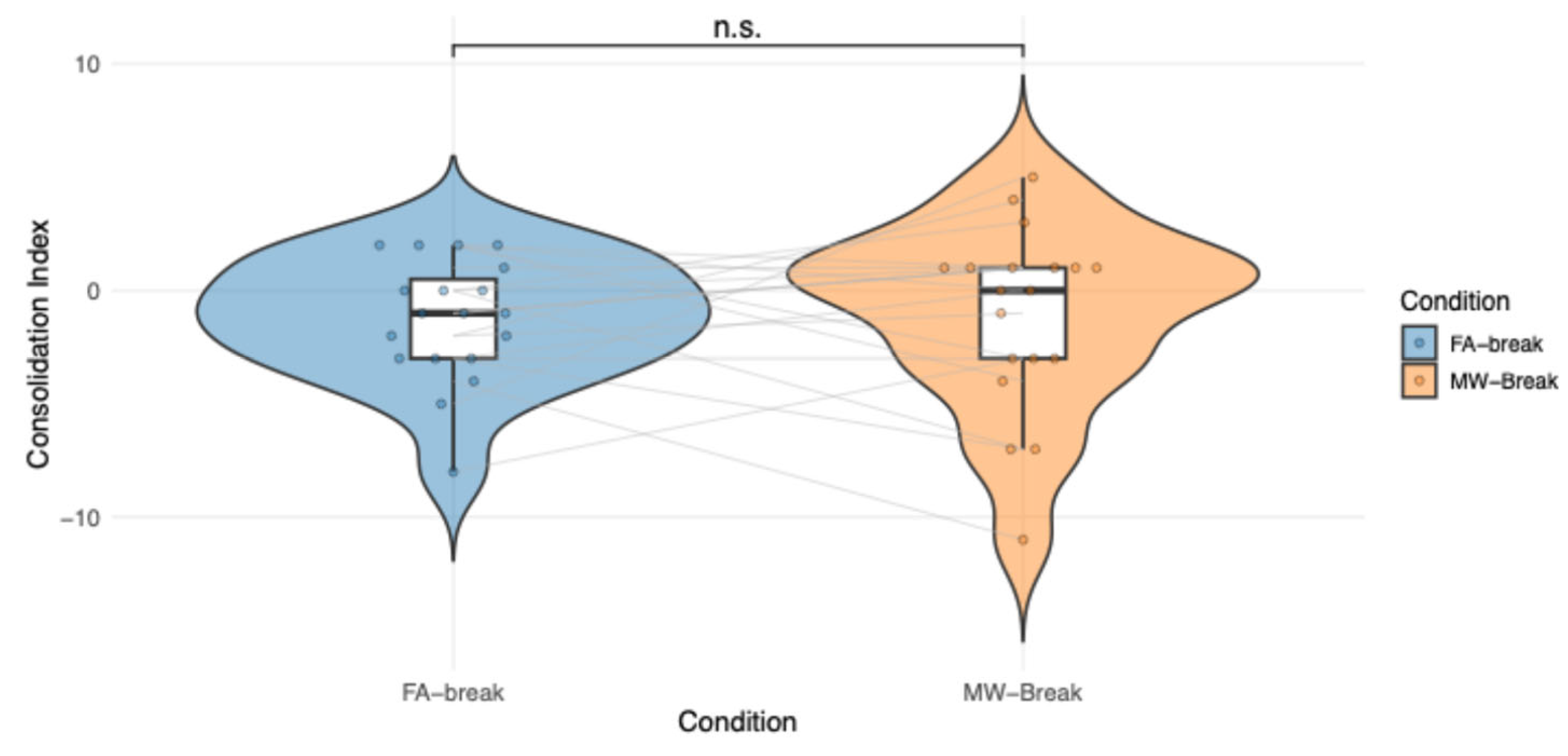

2.2.1. MW-Break vs FA-Break

We used a linear mixed-effects model on 38 observations (N 19 * 2 sessions) to test whether break condition (FA-Break vs MW-Break) influenced the consolidation index, calculated as in Study 1. The model revealed no significant Condition effect on the consolidation index (

β = 0.17,

SE = 0.91,

t(16) = 0.19,

p = .85, 95% CI [-1.61, 1.95]). To ensure that the observed effect of the condition was not driven by model specification, we conducted two complementary analyses as in Study 1. The reduced model including Condition only, yielded a non-significant effect of Condition comparable in direction and magnitude to that observed in the full model (

Appendix C.1; Table C1). Second, we performed a likelihood ratio test comparing the full model with an otherwise identical model excluding Condition. As expected, this analysis showed that the inclusion of Condition did not significantly improve model fit (

χ² (1) = 0.04,

p = .84; see

Appendix C.2; Table C2).

Bayesian linear mixed-effects analyses yielded results consistent with the frequentist approach, showing no effect of Condition on the consolidation index (β = 0.17, 95% CrI [-1.71, 2.06]). The estimated Bayes factor indicated positive evidence for the null hypothesis (BF₁₀ ≈ 0.20; BF01 ≈ 5.25).

Figure 5.

Individual participant's scores in the FA-Break and MW-Break Conditions are displayed in grey, illustrating within-subject variability. Colored dots represent raw consolidation index scores for each Condition and participant. A violin plot containing boxplots summarize the distribution within each Condition. No significant Condition effect is observed (p = .85).

Figure 5.

Individual participant's scores in the FA-Break and MW-Break Conditions are displayed in grey, illustrating within-subject variability. Colored dots represent raw consolidation index scores for each Condition and participant. A violin plot containing boxplots summarize the distribution within each Condition. No significant Condition effect is observed (p = .85).

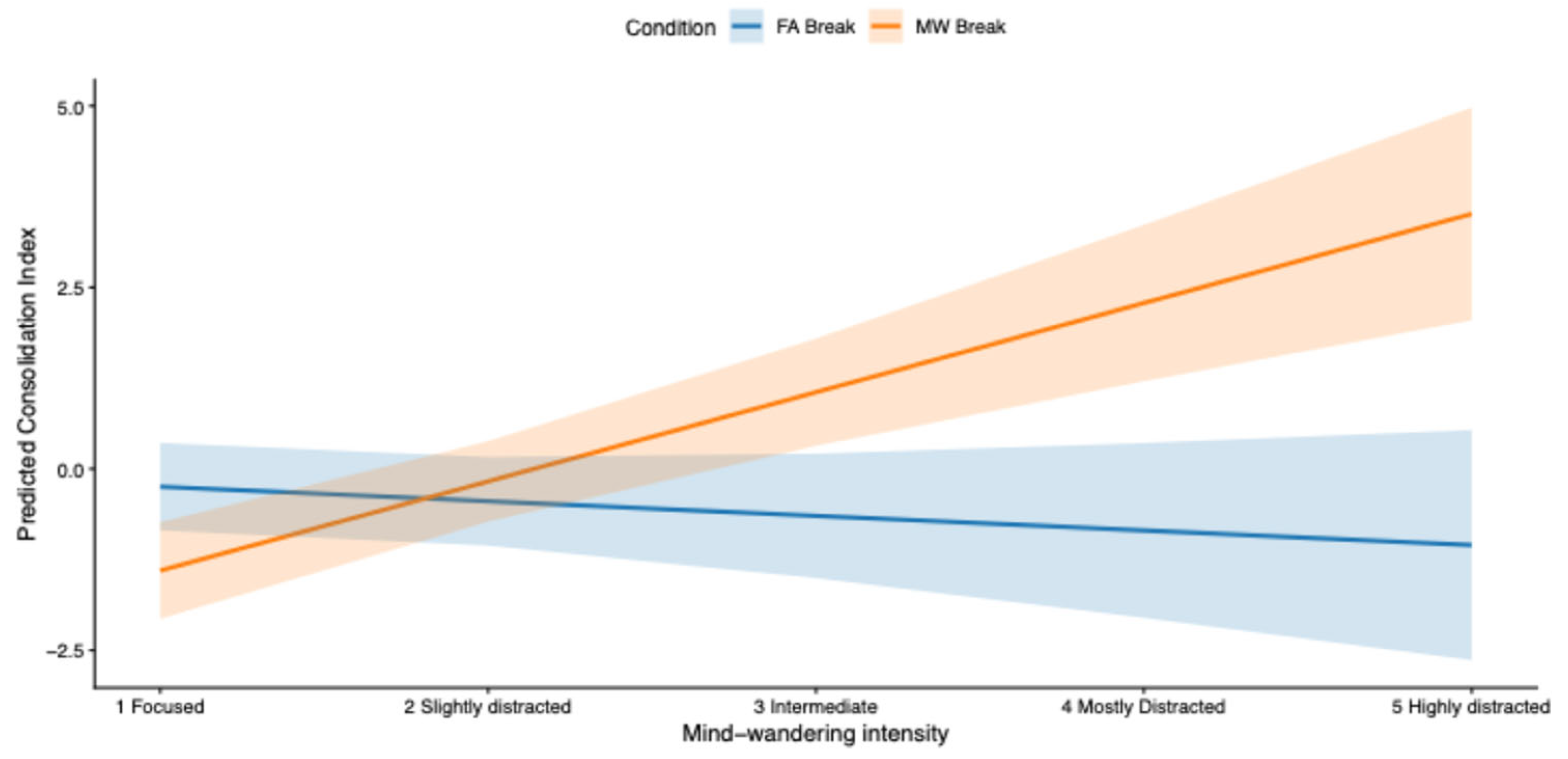

2.2.2. Condition x MW Intensity

To test whether mind-wandering intensity moderated the effect of experimental condition, we used the same procedure as in Study 1. A linear mixed-effects model on 114 observation (N 14 * 3 Blocks * 2 sessions) revealed a significant interaction between break Condition and mind-wandering intensity ((

β = 1.42,

SE = 0.29,

t(100) = 4.88,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.85, 2]). Specifically, the effect of MW-triggered breaks on the consolidation index depended on the level of reported mind wandering (

Figure 6).

Exploratory post hoc contrasts based on estimated marginal means indicated that MW-triggered breaks were associated with lower consolidation scores at the lowest level of mind wandering, no reliable difference at intermediate levels, and progressively higher consolidation scores at higher levels of mind wandering (

Appendix D; Table D1).

2.3. Exploratory Analysis

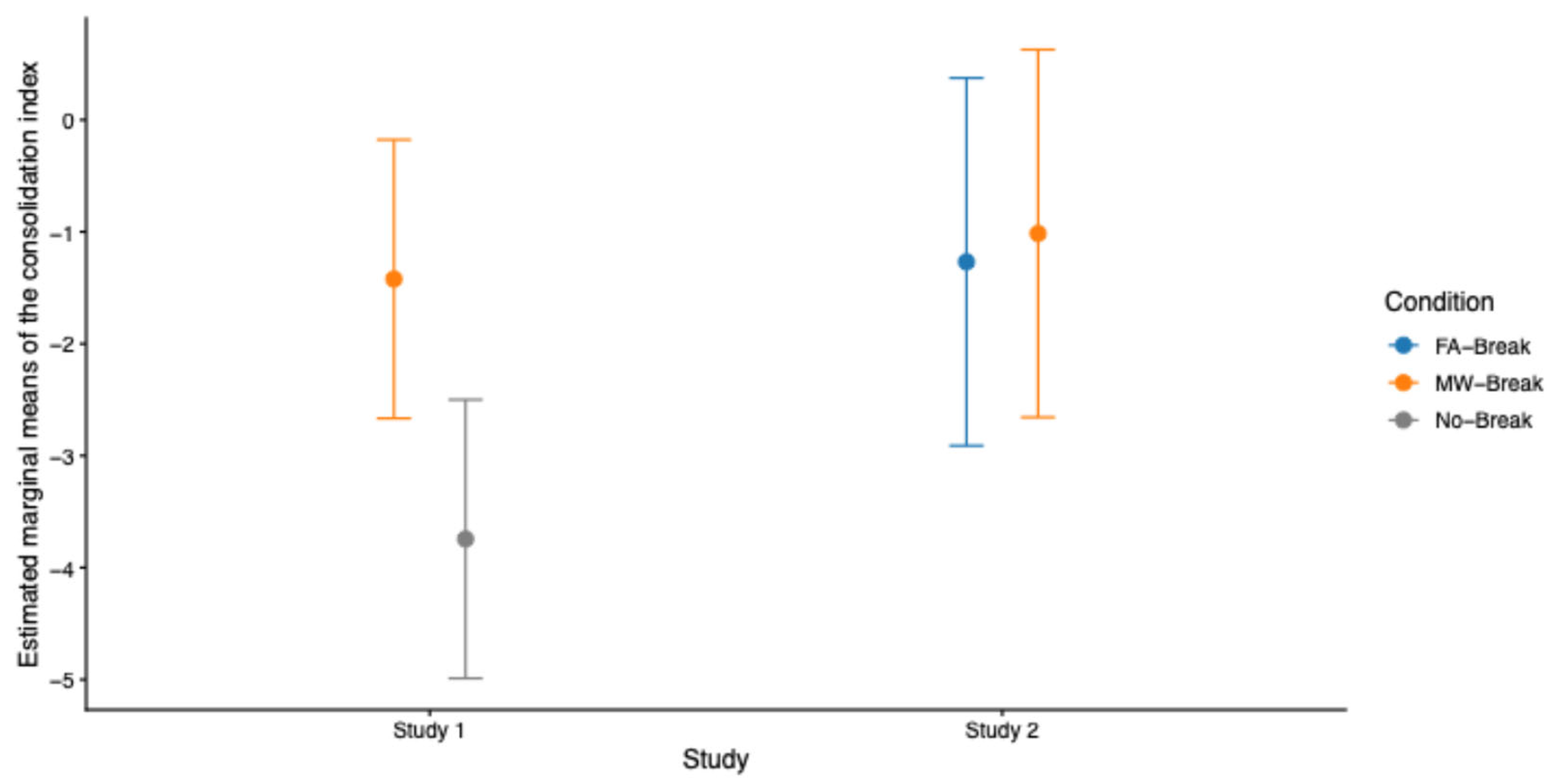

2.3.1. The Effect of Break (Study 1 + Study 2)

To further assess whether post-learning breaks facilitate memory consolidation and under which conditions, we conducted planned contrast analyses on Study 1 and Study 2 combined. First, we tested the interaction effect between Studies (

Study 1 vs. Study 2) and Break Conditions using a linear mixed-effects model fitted to 106 observations (53 participants (N = 34 for Study 1, N = 19 for Study 2) * 2 sessions). The consolidation index was computed as in both individual studies. The model revealed no significant interaction between Study and Break Condition on the consolidation index (

β = -2.07,

SE = 1.34,

t(49) = -1.54,

p = .13, 95% CI [-4.70, 0.56]), indicating that the effect of breaks did not differ reliably between studies. Post-hoc planned contrasts analyses based on estimated marginal means were conducted to test specific comparisons of interest. These analyses showed that the No-Break Condition in Study 1 was associated with significantly lower consolidation compared to the MW-Break Condition in Study 2 (

β = 2.73,

SE = 1.05,

t(97) = 2.6,

p = .01) and to the FA-Break Condition in Study 2 (

β = 2.48,

SE = 1.04,

t(96) = 2.38,

p = .02). At variance, consolidation following MW-Breaks in Study 1 did not differ from either FA-Breaks (

β = -0.15,

SE = 1.05,

t(97) = -0.15,

p = .88) or MW-Breaks (

β = -0.41,

SE = 1.04,

t(96) = -0.39,

p = 0.7) in Study 2 (

Figure 7), showing that improved memory consolidation scores are mostly related to the presence of breaks after learning blocks, irrespective of MW or FA reports (but see Condition x MW intensity results in Study 1 and Study 2).

2.3.2. Vigilance and Time-of-Day Factors

Because the present study focuses on attentional engagement during learning, we conducted exploratory analyses to examine whether vigilance and circadian timing factors could account for variability in performance or pause-related effects in Study 1 and Study 2.

First, we tested whether vigilance differed as a function of the condition order (i.e., the condition completed first). Vigilance was indexed using reciprocal reaction time (RRT), calculated as the inverse of reaction time (1/RT) during the Psychomotor Vigilance Task (PVT). This metric was chosen because it provides superior statistical properties by reducing the disproportionate influence of extremely long reaction times [

40]. In Study 1, a two-sample t-test comparing RRT performance between participants who started with the MW-Break Condition versus the No-Break Condition revealed no reliable difference (

t(32) = -0.69,

p = .5, 95% CI [-0.26; 0.13]). Likewise in Study 2, the same analysis comparing participants who started with the MW-Break versus the FA-Break Condition revealed no statistically significant difference (

t(33) =-1.47

p = .16, IC 95% [-0.46; 0.08]). To assess whether vigilance differed between studies, we conducted a two-way between-subjects ANOVA on RRT with Study and Condition order as factors. This analysis revealed no significant main effects of Study or Condition order, and no

Study x Condition order interaction (study:

F(1,49) = 0.36,

p = .55; condition order:

F(1,49) = 1.79,

p = .19; interaction:

F(1,49) = 0.53,

p = .47).

Second, we assessed whether the two samples differed in chronotype. A two-sample t-test comparing the

Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire [

41] scores between Study 1 and Study 2 indicated that chronotype did not reliably differ across Studies (

t(42) = -1.46, p= .15, 95% CI [ -10.65; 1.69]).

Third, we examined whether the effect of break condition varied as a function of the alignment between the time of testing and the participants’ subjective time-of-day preferences (i.e., when they reported being most versus least efficient). Participants indicated their subjectively optimal and least optimal time of day by selecting one of six 4-hour time windows (01:00–04:00, 05:00–08:00, 09:00–12:00, 13:00–16:00, 17:00–20:00, 21:00–24:00). The time of testing was assigned to the corresponding window. Alignment was operationalized as the circular distance (ranging from 0 to 3) between the testing window and the selected time-of-day window, such that the last and first windows were treated as adjacent (e.g., 21:00–24:00 and 01:00–04:00). Separate alignment measures were computed for the subjectively reported best and worst time-of-day windows. We then tested whether alignment moderated the effect of break condition on the consolidation index by adding an interaction term (Condition x Alignment) to the linear mixed-effects model. Alignment with the subjectively reported best time of day did not reliably moderate the effect of Break Condition on the consolidation index (study 1 : β = 1.77, SE = 1.36, t(30) = 1.3, p = .2, 95% CI [-0.89, 4.43]; study 2 : β = -2.11, SE = 1.46, t(15) = - 0.45, p = .17, 95% CI [-5, 0.74]). As similar with the subjectively reported worst time of day (study 1 : β = -1.42, SE = 1.14, t(30) = -1.24, p = .22, 95% CI [-3.65, 0.82]; study 2: β = 0.2, SE = 0.94, t(15) = 0.21, p = .83, 95% CI [-1.64, 2.05]).

3. Discussion

Across two experiments, we examined whether brief pauses inserted immediately after internally reported attentional disengagement (i.e., mind wandering [MW]) selectively benefit declarative memory consolidation for a verbal material. Although Study 1 showed evidenced for improved delayed recall performance and memory consolidation when a pause was allowed during the learning session after a mind-wandering (MW) report, Study 2 demonstrated that this advantage was not specific to the MW state in itself since performance equally improved when pauses were allowed either after a mind wandering or after a focused attention report. Notwithstanding, intensity analyses suggested that the effect of pauses may vary with MW intensity, the higher the MW intensity the higher the consolidation index. Thus, our results do not entirely support our initial assumption that MW reports would signal a privileged window for disengagement linked to the development of local sleep needs. Instead, it mostly suggests an unspecific beneficial effect of short quiet resting breaks during the learning process, beyond mind wandering effects.

Our results contribute to the ongoing debate about offline processing mechanisms taking place during wakefulness. Prior studies showed that wakeful rest can protect newly acquired traces from interference [

12,

13,

14], yet mixed findings have raised questions regarding the boundary conditions of such benefits [

18,

19,

20,

21]. The present data suggest that the main critical factor may not be the internal state triggering the pause. Rather, the cessation of ongoing input due to presentation of the learning material may be sufficient to support memory consolidation mechanisms. Although MW has been associated with behavioral lapses and reduced cortical responsiveness in other paradigms [

33,

34,

35,

36], the present findings do not allow us to infer a mechanistic link between attentional drift, putative offline states, and consolidation. Moreover, MW is a complex and multimodal phenomena [

42,

43,

44], and self-reported attentional states may capture heterogeneous underlying processes.

Beyond the general benefit of pauses observed in this experiment, our findings raise the question of

how internal cognitive dynamics determine the optimal moment to disengage from encoding. We propose here a hypothetical framework in which two pressures evolve jointly over the course of learning: an

attentional (or encoding) pressure, reflecting the system’s ability to maintain task-oriented processing, and a

consolidation pressure, corresponding to a growing need to stabilize recently encoded traces (

Figure 8).

This dual-dynamics perspective may help contextualizing variability in pause-related outcomes across studies, suggesting that the efficacy of rest periods during the learning process depends less on its duration than on its temporal alignment with internal processing demands. When consolidation pressure remains low, pauses may confer little measurable benefit; once consolidation demands exceed encoding efficiency, continued input may generate interference, and brief disengagement may reduce it. Under overload conditions, however, even pauses may not be sufficient to prevent decay.

This framework conceptually aligns with the Complementary learning systems account [

10], that distinguishes rapid hippocampal encoding from slower neocortical integration that requires interference reduction. It also converges with opportunity-cost approaches to attention and effort in which withdrawal reflects adaptive recalibration rather than breakdown [

45]. In this perspective, local sleep may not mark a mechanism of consolidation, but rather a potential reallocation cue under conditions of diminishing encoding return. Although speculative, this proposal resonates with reports of local sleep intrusions following cognitive load [

27,

32] and with accounts linking attentional decline to consolidation requirements [

46]. Crucially, however, the present data do not allow mechanistic inference. While our analyses suggest that the benefit of breaks may vary with the reported intensity of mind wandering, this factor was not experimentally controlled and should therefore be interpreted with caution. Future research combining real-time MW sampling with neural slow-wave markers, pupillometry, and temporally resolved modeling will be required to test whether offline disengagement and consolidation-related pressures co-evolve dynamically, and whether the effectiveness of brief pauses depends on their timing within broader circadian and cognitive dynamic, potentially opening the way for a chronobiological account of when pauses are most effective.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

All participants gave their written informed consent to participate in those studies approved by the ethics advisory committe of the ULB Faculty of Psychology (agreement # 1760/2024).

4.1.1. Study 1

A total of 48 healthy young adults participated in Study 1. Participants were recruited through three modalities: the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB) SONA recruitment platform, social media advertisements, and informal peer dissemination. SONA participants received course credits as compensation, the others participated without any compensation. Inclusion criteria required participants to be between 18 and 30 years of age. Because the aim of the analysis was to test the effect of break occurrence, we excluded participants who did not report MW and were thus not administered a break during the MW–triggered break condition. In addition, participants with a consolidation index exceeding three standard deviations from the mean (|z| > 3), based on model residuals, were considered outliers and excluded from the analysis (see appendix E; Figure E1). The final sample resulted to 34 participants (24 females, 10 males; M age = 23.26 years, SD = 3.65). Educational level completion was as follows: 12 participants with upper-secondary education, 8 with a bachelor’s degree, 13 with a master’s degree, and 1 with a doctoral-level degree.

4.2.1. Study 2

A total of 40 healthy young adults participated in the study. Participants were recruited through social media advertisements and received 20 € as compensation for their participation. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were the same as Study 1. Only participants who were administered a break in both MW and FA conditions were retained for the final analyses. No participants had an index of consolidation more than three standard deviation from the mean (|z|> 3) and in the residuals of the model, resulting in a final sample of 19 participants (13 females, 5 males, 1 non-binary; M age = 22.89 years, SD = 3.9). Educational level completion was as follows: 9 participants with upper-secondary education, 4 with a bachelor’s degree, 5 with a master’s degree, and 1 with a doctoral-level degree.

4.2.1. Study 1 + Study 2

Participants used in Study 1 and Study 2 analyses were retained, resulting in 53 participants (34 study 1 + 19 study 2; 37 females, 15 males, 1 non-binary; M age = 23.13 years, SD = 3.71).

4.2. General Procedure

4.2.1. Questionaries

Prior to the experimental task, participants completed a brief demographic form (age, gender, education level) and exploratory items assessing chronotype and subjective time-of-day performance. Chronotype was assessed using a French version of the

Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire [

41]. Subjective time-of-day optimal and non-optimal performance was assessed by asking participants to indicate the time intervals during which they felt most and least cognitively efficient, respectively (1h to 4h, 5h to 8h, 9h to 12h, 13h to 16h, 17h to 20h and, 21h to 24h).

4.2.2. Experimental Designs

The two studies employed a within-subject design with two learning sessions. Each session comprised 40 word-pairs presented in five blocks of eight pairs. Word pairs were disyllabic and selected randomly from the BRULEX database, a standardized French lexical resource providing frequency, phonological, and lexical norms (

https://crcn.ulb.ac.be/lab_post/brulex-2/). Two equivalent lists were created and counterbalanced across participants. Word pairs were displayed for 5 seconds each on a computer screen, and participants completed an immediate cued-recall test with feedback after every block (i.e., they were presented the first word of the pair and had to recall the second, associated word).

After each block of eight pairs, a probe-caught attentional rating Likert scale was administered (from 1 = Fully focused on the task (no mind-wandering). 2 = Mostly focused on the task, with occasional background thoughts, 3 = Split between the task and other thoughts, 4 = Mostly disengaged, but still loosely following the learning task 5 = Completely disengaged, no longer paying attention to the words). In the pause-allowed conditions (see below), a 3-minute quiet rest period could be introduced after blocks 2, 3, or 4 (maximum three breaks per session), depending on their attentional state. Study 1: In the MW condition, a rest period was allowed whenever participants reported attentional disengagement (Likert scale score > 1) after blocks 2, 3, or 4. In the No-Break session, no pauses were introduced irrespective of the outcome of the Likert scale. Experiment 2: Breaks were administrated in two different attentional states in separate sessions. In the MW-break session, a 3-minute rest was introduced after blocks 2, 3, or 4 when disengagement was reported (rating > 1). In the FA-break session, a 3-minute rest was introduced after mini-blocks 2, 3, or 4 when participants reported focused attention (rating = 1). No pauses were administered after block 1, as reduced focus at that point may have mostly reflected initial adjustment to the task rather than accumulated load, nor after block 5, which was always followed by a mandatory 10-minute quiet resting period in all conditions.

After completion of all five blocks in each session, participants underwent the mandatory 10-minute quiet rest and subsequently completed a final recall test without feedback covering all 40 word pairs. Condition order (Break vs No Break in Study 1; MW-break vs FA-break in Study 2) and stimulus lists were counterbalanced across participants.

To prevent participants from completing the two learning sessions consecutively, a

Psychomotor Vigilance Task (PVT) was inserted between sessions. The PVT is a simple visual stimulus detection task originally developed to assess vigilance and to identify attentional lapses [

47]. In the present study, the PVT was primary used to limit carryover effects between the two experimental phases [

48]

4.3. Statistical Procedure

All analyses were conducted using linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) to account for repeated measurements and inter-individual variability [

49,

50]. The consolidation index served as the dependent variable. Experimental condition was included as the predictor of interest. Recruitment, session, list, and condition order were included as covariates selected a priori. A random intercept for Participant was included to account for inter-individual variability. P-values for fixed effects were obtained using Satterthwaite approximations (lmerTest package). Model assumptions (normality and homoscedasticity of residuals) were assessed through standard diagnostic plots [

51,

52].

To assess the robustness of the

Condition effect to model specification, we conducted complementary analyses. First, we compared the full model to an otherwise identical model excluding

Condition using a likelihood ratio test. Second, we fitted a reduced model including

Condition only (without covariates) and compared the estimated effect of

Condition across model specifications. Finally, to complement the frequentist analyses, we conducted a Bayesian analysis using the same model structure. Models were fitted using the

brms package (version 2.23.0) with a Gaussian likelihood. Weakly informative priors were specified for fixed effects

(normal(0, 5)), random-effect standard deviations

(cauchy(0, 2)), and the residual standard deviation

(cauchy(0, 2))[

53,

54,

55]. Posterior distributions were estimated using four Markov chain Monte Carlo chains with 4,000 iterations each

(1,000 warm-up). Evidence for the effect of

Condition was quantified using Bayes factors by comparing the full model to a null model excluding

Condition The interpretation of Bayes factors was based on the threshold framework introduced by Raftery [

56].All exploratory analysis were computed using the full model with the variables of interests.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

J.C.D. and P.P. conceived the experiment. J.C.D carried out the experiment, data preparation, data cleaning, and data analysis. P.P. supervised the entire work. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the analysis and manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (F.N.R.S.) and the Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek – Vlaanderen (F.W.O.) in the framework of the Excellence of Science (EOS) Project (MEMODYN, No. 30446199 to P.P.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

In The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Psychology Faculty Advisory Ethics Committee of the Université Libre de Bruxelles (agreement number # 1760/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Available on demand.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EEG |

Electroencephalogram |

| FA |

Focused attention |

MW

LMM |

Mind-wandering

Linear mixed-effects models |

SWA

SWS |

Slow-wave activity

Slow-wave sleep |

Appendix A. Sensitivity Analyses and Model Comparisons Study 1

Appendix A.1. Sensitivity Analysis: Reduced Model Including Condition Only

As a sensitivity analysis, we fitted a reduced model including Condition only (without covariates) and compared the estimated effect of Condition to that obtained from the full model. This analysis was conducted to assess the robustness of the Condition effect to model specification rather than to formally compare model fit.

Table A1.

Estimated effect of Condition across model specifications.

Table A1.

Estimated effect of Condition across model specifications.

| Model |

β |

SE |

df |

t |

p |

| Condition-only |

2.06 |

0.83 |

33 |

2.47 |

0.019 |

| Full |

2.24 |

0.88 |

31 |

2.56 |

0.016 |

Appendix A.2. Contribution of Condition Beyond Covariates

To assess whether the effect of Condition contributed to model fit beyond the inclusion of covariates, we compared a full linear mixed-effects model including Condition, Recruitment, Session, List, and which condition they started with to an otherwise identical model excluding Condition. Models were fitted using maximum likelihood estimation and compared using a likelihood ratio.

Table A2.

Likelihood ratio test comparing the full model to a model without the condition.

Table A2.

Likelihood ratio test comparing the full model to a model without the condition.

| Model |

AIC |

BIC |

logLik |

χ² |

df |

p |

| Reduced |

379.89 |

397.64 |

-181.95 |

- |

- |

- |

| Full |

375.04 |

395.01 |

-178.52 |

6.85 |

1 |

0.009 |

Appendix B. Exploratory Post Hoc Contrasts Study 1

Table B1.

Post hoc contrasts between MW-Break and No Break across levels of mind-wandering intensity. Contrast: MW Break – No Break.

Table B1.

Post hoc contrasts between MW-Break and No Break across levels of mind-wandering intensity. Contrast: MW Break – No Break.

MW

Intensity |

Estimate |

SE |

df |

t |

p |

| 1 |

0.27 |

0.26 |

174 |

1.02 |

0.31 |

| 2 |

0.72 |

0.17 |

165 |

4.26 |

< .01 |

| 3 |

1.17 |

1.17 |

175 |

4.59 |

< .01 |

| 4 |

1.63 |

1.63 |

179 |

3.84 |

< .01 |

| 5 |

2.08 |

2.08 |

180 |

3.42 |

< .01 |

Appendix C. Sensitivity Analyses and Model Comparisons Study 2

Appendix C.1. Sensitivity Analysis: Reduced Model Including Condition Only

As a sensitivity analysis, we fitted a reduced model including Condition only (without covariates) and compared the estimated effect of Condition to that obtained from the full model. This analysis was conducted to assess the robustness of the Condition effect to model specification rather than to formally compare model fit.

Table C1.

Estimated effect of Condition across model specifications.

Table C1.

Estimated effect of Condition across model specifications.

| Model |

β |

SE |

df |

t |

p |

| Condition-only |

0.16 |

1.04 |

18 |

0.15 |

0.88 |

| Full |

0.17 |

0.91 |

16 |

0.19 |

0.85 |

Appendix C.2. Contribution of Condition Beyond Covariates

To assess whether the effect of Condition contributed to model fit beyond the inclusion of covariates, we compared a full linear mixed-effects model including Condition, Session, List, and which condition they started with to an otherwise identical model excluding Condition. As all participants came from the same source of recruitment, recrutement wasn’t added as a covariable. Models were fitted using maximum likelihood estimation and compared using a likelihood ratio.

Table C2.

Likelihood ratio test comparing the full model to a model without the condition.

Table C2.

Likelihood ratio test comparing the full model to a model without the condition.

| Model |

AIC |

BIC |

logLik |

χ² |

df |

p |

| Reduced |

202.4 |

212.23 |

-95.2 |

- |

- |

- |

| Full |

204.36 |

215.82 |

-95.18 |

0.04 |

1 |

0.84 |

Appendix D. Exploratory Post Hoc Contrasts Study 2

Table D1.

Post hoc contrasts between MW-Break and FA-Break across levels of mind-wandering intensity. Contrast: MW Break – FA Break.

Table D1.

Post hoc contrasts between MW-Break and FA-Break across levels of mind-wandering intensity. Contrast: MW Break – FA Break.

MW

Intensity |

Estimate |

SE |

df |

t |

p |

| 1 |

-1.16 |

0.28 |

92 |

-4.11 |

< .01 |

| 2 |

0.27 |

0.24 |

91 |

1.13 |

0.26 |

| 3 |

1.7 |

0.47 |

93 |

3.64 |

< .01 |

| 4 |

3.13 |

0.75 |

94 |

4.18 |

< .01 |

| 5 |

4.56 |

1.04 |

94 |

4.38 |

< .01 |

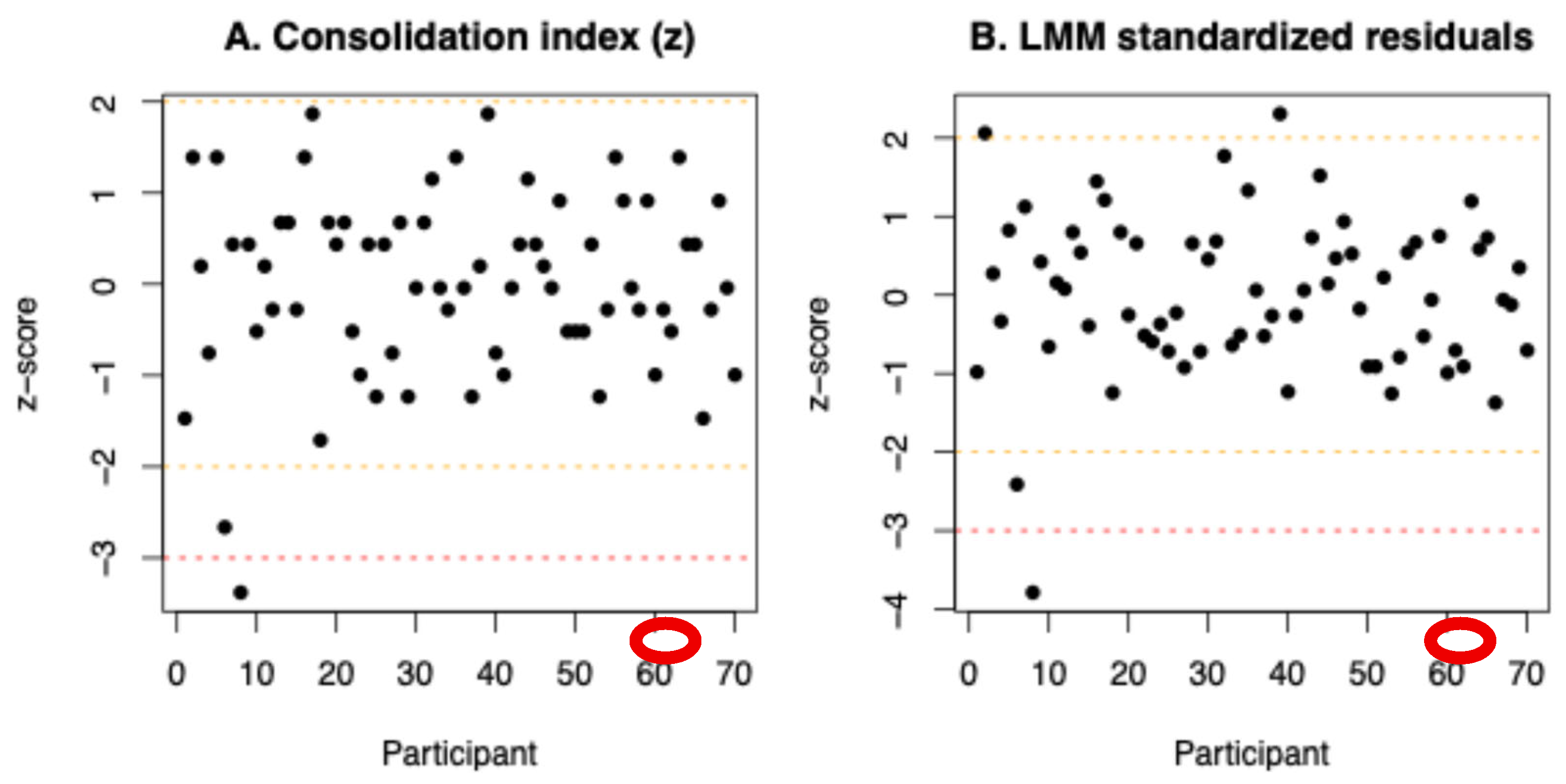

Appendix E. Outlier Exclusion

Outliers were identified based on standardized residuals of the model and on standardized consolidation index score, where |z| > 3. One participant was identified as an outlier and excluded from the analyses (Figure C1). Although this participant reported discomfort during the experiment (headache due to light exposure and continuous white noise) and uncertainty about task instructions, these self-reports were not used as exclusion criteria and are reported here for transparency.

Figure E1.

Identification of an outlier based on standardized Consolidation index . Consolidation index are shown for all participants. Dashed orange lines indicate ±2 standard deviations, and the red dashed line indicates the exclusion threshold at −3 standard deviations. (B) Identification of an outlier based on standardized residuals. Standardized residuals from the linear mixed-effects model are shown for all participants. Dashed orange lines indicate ±2 standard deviations, and the red dashed line indicates the exclusion threshold at −3 standard deviations. (A and B) The circled data point corresponds to the same participant whose residual and consolidation index exceeded the threshold and was therefore classified as an outlier.

Figure E1.

Identification of an outlier based on standardized Consolidation index . Consolidation index are shown for all participants. Dashed orange lines indicate ±2 standard deviations, and the red dashed line indicates the exclusion threshold at −3 standard deviations. (B) Identification of an outlier based on standardized residuals. Standardized residuals from the linear mixed-effects model are shown for all participants. Dashed orange lines indicate ±2 standard deviations, and the red dashed line indicates the exclusion threshold at −3 standard deviations. (A and B) The circled data point corresponds to the same participant whose residual and consolidation index exceeded the threshold and was therefore classified as an outlier.

References

- Conway, M.A. Episodic Memories. Neuropsychologia 2009, 47, 2305–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squire, L.R.; Wixted, J.T. The Cognitive Neuroscience of Human Memory Since H.M. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 34, 259–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klinzing, J.G.; Niethard, N.; Born, J. Mechanisms of Systems Memory Consolidation during Sleep. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 1598–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, N.D.; Harkotte, M.; Born, J. Sleep’s Contribution to Memory Formation. Physiol. Rev. 2026, 106, 363–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benington, J.H.; Frank, M.G. Cellular and Molecular Connections between Sleep and Synaptic Plasticity. Prog. Neurobiol. 2003, 69, 71–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menicucci, D.; Piarulli, A.; Laurino, M.; Zaccaro, A.; Agrimi, J.; Gemignani, A. Sleep Slow Oscillations Favour Local Cortical Plasticity Underlying the Consolidation of Reinforced Procedural Learning in Human Sleep. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 29, e13117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodt, S.; Inostroza, M.; Niethard, N.; Born, J. Sleep—A Brain-State Serving Systems Memory Consolidation. Neuron 2023, 111, 1050–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, C.; Denis, D.; Coleman, J.; Ren, B.; Oh, A.; Cox, R.; Morgan, A.; Sato, E.; Stickgold, R. Both Slow Wave and Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Contribute to Emotional Memory Consolidation. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudai, Y.; Karni, A.; Born, J. The Consolidation and Transformation of Memory. Neuron 2015, 88, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, J.L.; O’Reilly, R.C. Why There Are Complementary LearningSystems in the Hippocampus and Neocortex:InsightsFrom the Successesand Failuresof Connectionist Modelsof Learning andMemory.

- Wixted, J.T. The Psychology and Neuroscience of Forgetting. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 235–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewar, M.; Garcia, Y.F.; Cowan, N.; Sala, S.D. Delaying Interference Enhances Memory Consolidation in Amnesic Patients. Neuropsychology 2009, 23, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wamsley, E.J. Memory Consolidation during Waking Rest. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2019, 23, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewar, M.; Alber, J.; Butler, C.; Cowan, N.; Della Sala, S. Brief Wakeful Resting Boosts New Memories Over the Long Term. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, M.; Alber, J.; Cowan, N.; Della Sala, S. Boosting Long-Term Memory via Wakeful Rest: Intentional Rehearsal Is Not Necessary, Consolidation Is Sufficient. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brokaw, K.; Tishler, W.; Manceor, S.; Hamilton, K.; Gaulden, A.; Parr, E.; Wamsley, E.J. Resting State EEG Correlates of Memory Consolidation. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2016, 130, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjøgård, M.; Baxter, B.; Mylonas, D.; Thompson, M.; Kwok, K.; Driscoll, B.; Tolosa, A.; Shi, W.; Stickgold, R.; Vangel, M.; et al. Hippocampal Ripples Predict Motor Learning during Brief Rest Breaks in Humans 2024.

- Tucker, M.A.; Humiston, G.B.; Summer, T.; Wamsley, E. Comparing the Effects of Sleep and Rest on Memory Consolidation. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2020, Volume 12, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humiston, G.B.; Wamsley, E.J. A Brief Period of Eyes-Closed Rest Enhances Motor Skill Consolidation. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2018, 155, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotermans, C.; Peigneux, P.; Maertens De Noordhout, A.; Moonen, G.; Maquet, P. Early Boost and Slow Consolidation in Motor Skill Learning. Learn. Mem. 2006, 13, 580–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, M.; Sachse, P. Factors Modulating the Effects of Waking Rest on Memory. Cogn. Process. 2020, 21, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vékony, T.; Farkas, B.C.; Brezóczki, B.; Mittner, M.; Csifcsák, G.; Simor, P.; Németh, D. Mind Wandering Enhances Statistical Learning. iScience 2025, 28, 111703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borbely, A.A. A Two Process Model of Sleep Regulation.

- Durmer, J.S. Neurocognitive Consequences of Sleep Deprivation. [CrossRef]

- Porkka-Heiskanen, T.; Strecker, R.E.; Thakkar, M.; Bjørkum, A.A.; Greene, R.W.; McCarley, R.W. Adenosine: A Mediator of the Sleep-Inducing Effects of Prolonged Wakefulness. Science 1997, 276, 1265–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio, S.; Castelnovo, A.; Guglielmi, O.; Nobili, L.; Sarasso, S.; Garbarino, S. Sleepiness as a Local Phenomenon. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrillon, T.; Windt, J.; Silk, T.; Drummond, S.P.A.; Bellgrove, M.A.; Tsuchiya, N. Does the Mind Wander When the Brain Takes a Break? Local Sleep in Wakefulness, Attentional Lapses and Mind-Wandering. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geva-Sagiv, M.; Nir, Y. Local Sleep Oscillations: Implications for Memory Consolidation. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, J.M.; Nguyen, J.T.; Dykstra-Aiello, C.J.; Taishi, P. Local Sleep. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019, 43, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrillon, T.; Burns, A.; Mackay, T.; Windt, J.; Tsuchiya, N. Predicting Lapses of Attention with Sleep-like Slow Waves. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, R.; Felice Ghilardi, M.; Massimini, M.; Tononi, G. Local Sleep and Learning. Nature 2004, 430, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siclari, F.; Bernardi, G.; Riedner, B.A.; LaRocque, J.J.; Benca, R.M.; Tononi, G. Two Distinct Synchronization Processes in the Transition to Sleep: A High-Density Electroencephalographic Study. Sleep 2014, 37, 1621–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quercia, A.; Zappasodi, F.; Committeri, G.; Ferrara, M. Local Use-Dependent Sleep in Wakefulness Links Performance Errors to Learning. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyazovskiy, V.V.; Olcese, U.; Hanlon, E.C.; Nir, Y.; Cirelli, C.; Tononi, G. Local Sleep in Awake Rats. Nature 2011, 472, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubera-Garcia, E.; Gevers, W.; Van Opstal, F. Local Build-up of Sleep Pressure Could Trigger Mind Wandering: Evidence from Sleep, Circadian and Mind Wandering Research. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 191, 114478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.; Newman, A. Measuring Mind Wandering During Online Lectures Assessed With EEG. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 697532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wienke, C.; Bartsch, M.V.; Vogelgesang, L.; Reichert, C.; Hinrichs, H.; Heinze, H.-J.; Dürschmid, S. Mind-Wandering Is Accompanied by Both Local Sleep and Enhanced Processes of Spatial Attention Allocation. Cereb. Cortex Commun. 2021, 2, tgab001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumuer, E.; Kaşıkcı, D.N. The Role of Smartphones in College Students’ Mind-Wandering during Learning. Comput. Educ. 2022, 190, 104616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, N.; Robison, M.K. Tracking Arousal State and Mind Wandering with Pupillometry. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 18, 638–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basner, M.; Dinges, D.F. Maximizing Sensitivity of the Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) to Sleep Loss. Sleep 2011, 34, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, J.A.; Östberg, O. A Self-Assessment Questionnaire to Determine Morningness–Eveningness in Human Circadian Rhythms. Int. J. Chronobiol. 1976, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, N.K.; Faiz, U.B.; Brosowsky, N.P. How Do You Know If You Were Mind Wandering? Dissociating Explicit Memories of Off Task Thought From Subjective Feelings of Inattention. [CrossRef]

- Jubera-García, E.; Gevers, W.; Van Opstal, F. Influence of Content and Intensity of Thought on Behavioral and Pupil Changes during Active Mind-Wandering, off-Focus, and on-Task States. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2020, 82, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, J.W.Y.; Rahnuma, T.; Park, Y.E.; Hart, C.M. Electrophysiological Markers of Mind Wandering: A Systematic Review. NeuroImage 2022, 258, 119372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurzban, R.; Duckworth, A.; Kable, J.W.; Myers, J. An Opportunity Cost Model of Subjective Effort and Task Performance. Behav. Brain Sci. 2013, 36, 661–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, M.M.; Turk-Browne, N.B. Interactions between Attention and Memory. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2007, 17, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Dinges, D.F. Sleep Deprivation and Vigilant Attention

. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1129, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsell, S. Task Switching. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2003, 7, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, D.J.; Levy, R.; Scheepers, C.; Tily, H.J. Random Effects Structure for Confirmatory Hypothesis Testing: Keep It Maximal. J. Mem. Lang. 2013, 68, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baayen, R.H.; Davidson, D.J.; Bates, D.M. Mixed-Effects Modeling with Crossed Random Effects for Subjects and Items. J. Mem. Lang. 2008, 59, 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuschek, H.; Kliegl, R.; Vasishth, S.; Baayen, H.; Bates, D. Balancing Type I Error and Power in Linear Mixed Models. J. Mem. Lang. 2017, 94, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürkner, P.-C. Brms : An R Package for Bayesian Multilevel Models Using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A. Prior Distributions for Variance Parameters in Hierarchical Models (Comment on Article by Browne and Draper). Bayesian Anal. 2006, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenmakers, E.-J.; Marsman, M.; Jamil, T.; Ly, A.; Verhagen, J.; Love, J.; Selker, R.; Gronau, Q.F.; Šmíra, M.; Epskamp, S.; et al. Bayesian Inference for Psychology. Part I: Theoretical Advantages and Practical Ramifications. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2018, 25, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, A.F.; Wiley, J. What Are the Odds? A Practical Guide to Computing and Reporting Bayes Factors. J. Probl. Solving 2014, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Theoretical consolidation-pressure framework. As encoding continues, consolidation load accumulates (increased consolidation pressure). When it exceeds a given threshold (purple dashed line), transient offline disengagement and MW emerge. If no break is taken (red line), the consolidation pressure continues rising, impairing performance and stabilization of memory traces. If a break is allowed shortly after disengagement (green line), then consolidation pressure drops, preserving learning capabilities and favoring off-line memory processing. The lower black curve illustrates a focused encoding condition in which consolidation pressure always remains below threshold.

Figure 1.

Theoretical consolidation-pressure framework. As encoding continues, consolidation load accumulates (increased consolidation pressure). When it exceeds a given threshold (purple dashed line), transient offline disengagement and MW emerge. If no break is taken (red line), the consolidation pressure continues rising, impairing performance and stabilization of memory traces. If a break is allowed shortly after disengagement (green line), then consolidation pressure drops, preserving learning capabilities and favoring off-line memory processing. The lower black curve illustrates a focused encoding condition in which consolidation pressure always remains below threshold.

Figure 2.

Experimental design Study 1. Participants learned 5 blocks of 8 word-pairs. After each block, a probe-caught mind-wandering question assessed their attentional state. In blocks 2, 3 or 4 in the MW condition, a 3-minute quiet resting break was administered immediately after the probe if participants reported mind wandering. In the control condition, no pause was allowed irrespective of the output of the MW probe. Participants completed after each block (and pause if any) an immediate cued-recall test on the same 8 word-pairs with corrective feedback. The sequence was repeated five times for a total of 40 learned word-pairs. In both conditions, participants had a 10-minute break after block 5, followed by a final cued-recall test on the 40 learned word-pairs, without feedback. Participants were successively administered both conditions in a randomized order with a 10-min interval between conditions filled in with a psychomotor vigilance task.

Figure 2.

Experimental design Study 1. Participants learned 5 blocks of 8 word-pairs. After each block, a probe-caught mind-wandering question assessed their attentional state. In blocks 2, 3 or 4 in the MW condition, a 3-minute quiet resting break was administered immediately after the probe if participants reported mind wandering. In the control condition, no pause was allowed irrespective of the output of the MW probe. Participants completed after each block (and pause if any) an immediate cued-recall test on the same 8 word-pairs with corrective feedback. The sequence was repeated five times for a total of 40 learned word-pairs. In both conditions, participants had a 10-minute break after block 5, followed by a final cued-recall test on the 40 learned word-pairs, without feedback. Participants were successively administered both conditions in a randomized order with a 10-min interval between conditions filled in with a psychomotor vigilance task.

Figure 3.

Individual participant's consolidation scores in the No Break and MW-Break Conditions are displayed in grey, illustrating within-subject variability. Colored dots represent raw consolidation index scores for each condition and participant. A violin plot containing boxplots summarize the distribution within each condition. A significant Condition effect is observed, with a higher consolidation score (i.e., less forgetting) in the MW-Break than in the No Break (p = .016) condition.

Figure 3.

Individual participant's consolidation scores in the No Break and MW-Break Conditions are displayed in grey, illustrating within-subject variability. Colored dots represent raw consolidation index scores for each condition and participant. A violin plot containing boxplots summarize the distribution within each condition. A significant Condition effect is observed, with a higher consolidation score (i.e., less forgetting) in the MW-Break than in the No Break (p = .016) condition.

Figure 4.

Model-estimated marginal means of the consolidation index across levels of mind-wandering intensity for the No-break and MW-break conditions. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. Predictions are derived from a linear mixed-effects model fitted to blocks 2–4 where the interaction between Condition and MW Intensity is significative (p = 0.02).

Figure 4.

Model-estimated marginal means of the consolidation index across levels of mind-wandering intensity for the No-break and MW-break conditions. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. Predictions are derived from a linear mixed-effects model fitted to blocks 2–4 where the interaction between Condition and MW Intensity is significative (p = 0.02).

Figure 6.

Model-estimated marginal means of the consolidation index across levels of mind-wandering intensity for the FA-break and MW-break conditions. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. Predictions are derived from a linear mixed-effects model fitted to blocks 2–4 where the interaction between Condition and MW Intensity is significative (p < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Model-estimated marginal means of the consolidation index across levels of mind-wandering intensity for the FA-break and MW-break conditions. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. Predictions are derived from a linear mixed-effects model fitted to blocks 2–4 where the interaction between Condition and MW Intensity is significative (p < 0.001).

Figure 7.

Estimated marginal means of the consolidation index from the linear mixed-effects model for combining Study 1 and Study 2. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. In Study 1, consolidation is lower in the no-break condition relative to the MW-Break condition, whereas in Study 2 consolidation does not differ between MW-Break and FA-Break conditions.

Figure 7.

Estimated marginal means of the consolidation index from the linear mixed-effects model for combining Study 1 and Study 2. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. In Study 1, consolidation is lower in the no-break condition relative to the MW-Break condition, whereas in Study 2 consolidation does not differ between MW-Break and FA-Break conditions.

Figure 8.

Conceptual schematic of a dual pressure dynamics model. Encoding pressure gradually declines while consolidation pressure increases, potentially creating intervals during which continued input may interfere with stabilization. Note that this transition zone is purely theoretical and not directly inferred from the present behavioral data.

Figure 8.

Conceptual schematic of a dual pressure dynamics model. Encoding pressure gradually declines while consolidation pressure increases, potentially creating intervals during which continued input may interfere with stabilization. Note that this transition zone is purely theoretical and not directly inferred from the present behavioral data.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).