1. Introduction

In regions facing water scarcity, efficient water management is essential to ensure sustainable agricultural production. One widely adopted strategy to improve irrigation efficiency and conserve soil moisture is the use of soil covers, which act as vapour diffusion barriers at the soil–atmosphere interface [

1,

2]. By reducing evaporation losses and promoting transpiration, mulching practices can increase soil water availability, plant biomass, and crop yield [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Mulching consists of applying an organic, synthetic, or inorganic layer over the soil surface to modify heat and water exchange processes. This practice improves soil moisture retention, moderates soil temperature, suppresses weed growth, and enhances microbial activity [

7]. The effects of mulches on soil thermal and hydrological regimes have been extensively documented [

8,

9,

10,

11], with soil temperature responses strongly influenced by the optical and thermal properties of the covering material [

10].

In greenhouse production systems, where energy exchanges among soil, plants, air, and structural components are particularly complex [

12], soil covers play a key role in shaping the microclimate and, consequently, crop performance. The effectiveness of mulching materials depends not only on their physical composition but also on their colour, which determines their optical behaviour and capacity to reflect solar radiation [

13]. In this context, the interaction between mulch properties and soil–plant–atmosphere energy fluxes influence critical processes such as radiation balance, conduction, convection, evaporation, and condensation [

14].

Beyond their microclimatic effects, mulches provide several agronomic benefits, including weed suppression, improved soil thermal regulation, reduced evaporative losses, and earlier crop development [

15,

16]. These advantages often translate into enhanced yield and product quality [

17,

18]. However, the use of plastic mulches also presents limitations, such as increased production costs [

19] and environmental concerns related to plastic waste accumulation [

20]. In warm climates, excessive soil heating under plastic covers may further impair crop performance by inducing thermal stress in the root zone [

21,

22,

23].

In addition to their physical effects, mulches influence plant physiological processes, particularly photosynthesis, which is highly sensitive to changes in the growing environment [

24]. Variations in soil temperature and light reflection can affect gas exchange, leaf development, and overall plant performance [

25]. Since leaves are the primary photosynthetic organs directly linked to yield formation, optimizing their functional activity during reproductive stages is crucial [

26,

27]. Several studies have shown that plastic mulching can enhance photosynthetic capacity by improving root-zone conditions and plant water status [

28,

29].

White or reflective mulches can increase the proportion of short-wave radiation reflected toward the canopy, thereby enhancing the availability of photosynthetically active radiation [

30]. However, their effects on crop performance are not always consistent. While some studies report increased yields and reduced incidence of insect-transmitted diseases [

31,

32], others indicate limited benefits or potential drawbacks, such as reduced soil heat accumulation [

33]. Consequently, the suitability of reflective mulches depends on crop type, climate, and production system.

From an environmental perspective, the widespread use of plastic mulches has raised concerns due to the large volumes of agricultural plastic waste generated annually. In Spain alone, up to 35,000 tonnes of plastic residues are produced each year, particularly in intensive horticultural regions such as Andalucía, Castilla-La Mancha, and Murcia [

34].

Against this background, the objective of the present study is to evaluate the effects of different highly reflective soil mulches on microclimate, plant growth, yield, and photosynthetic activity of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) cultivated under multispan greenhouse conditions during the spring–summer growing season. Two mulching materials were compared: a white polyethylene plastic film and a black polypropylene plastic film.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

The present study was conducted during the spring‒summer 2024 season at the Centre for Innovation and Technology Transfer ‘Fundación UAL-ANECOOP’ (latitude: 36°51’53.2” N; longitude: 2°16’58.8” W; altitude: 87 m). A multispan greenhouse (800 m

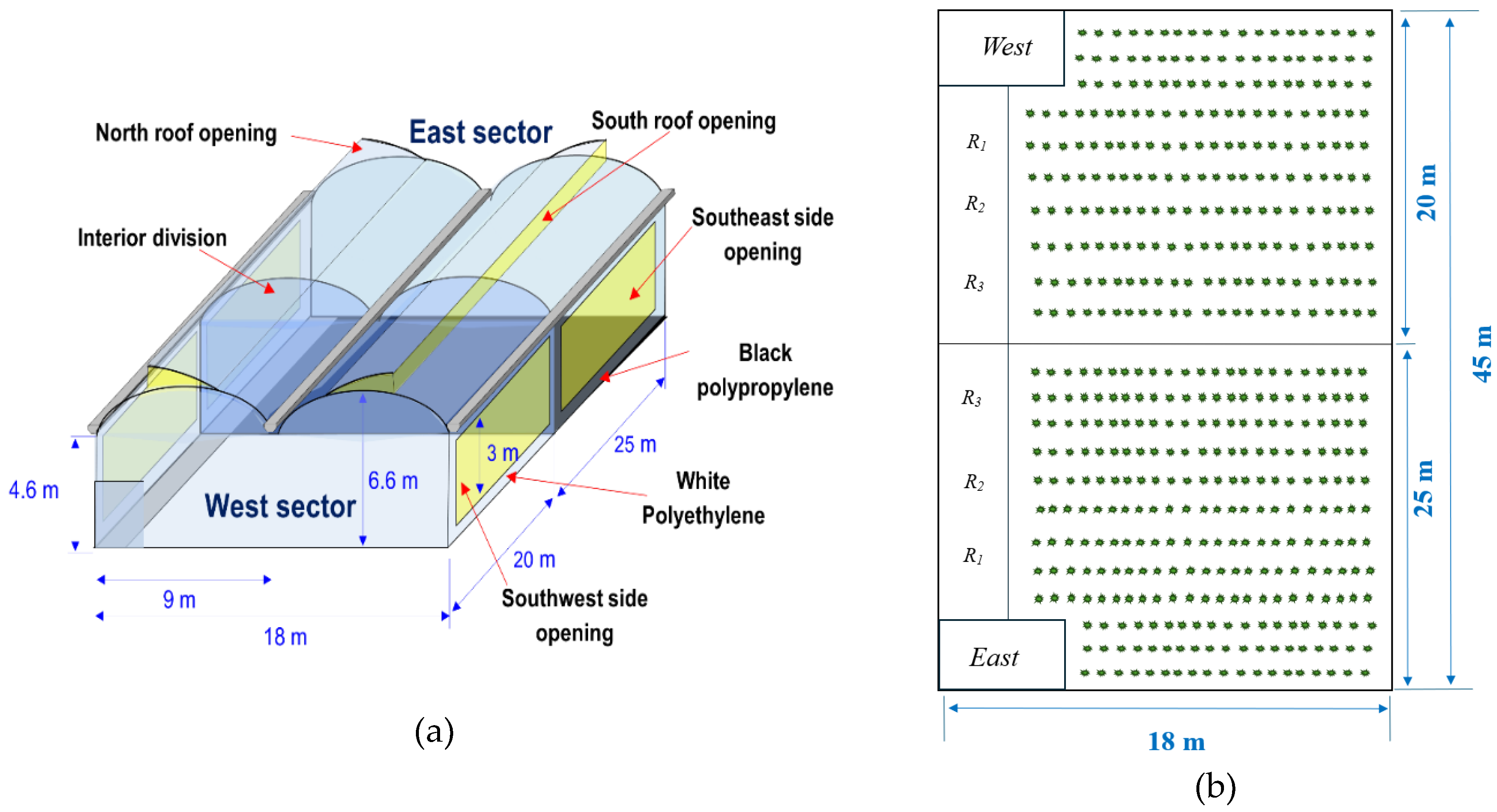

2, orientation: 118°N) was divided into two similar sectors, East and West (

Table 1), using a vertical plastic sheet as a partition. The greenhouse is equipped with two roof vents, one facing north and the other south, as well as two side vents with a maximum opening of 3 metres (

Figure 1).

Ventilation was controlled by Synopta Software 5.4.2.3931422 (Ridder Growing Solutions B.V., Maasdijk, The Netherlands), a centralised climate control and data logging system with a weather station. The temperature setpoint for control of vent opening was 20 °C.

In the eastern sector of the greenhouse (control treatment), a black polypropylene agrotextile mulch with a thickness of 0.225 μm was installed, while in the western sector, a white polyethylene plastic mulch (black on the inner side) with a thickness of 30 μm (model E1115, Politiv, Kibbutz Einat, Israel) was used (

Figure 2).

2.2. Crop Systems

To evaluate the effect of plastic mulch on pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) cultivation, a spring–summer growing cycle was conducted using the commercial cultivar Bemol RZ (Rijk Zwaan Ibérica, S.A., Almería, Spain). Transplanting was carried out on 5 March 2024 onto a coconut fibre substrate at a planting density of 1 plant m−2, with crop rows oriented perpendicular to the greenhouse ridge. Fertigation was uniformly applied in both experimental sectors through a drip irrigation system managed by a Supra irrigation controller (Hermisan, Alicante, Spain). Standard crop management practices, including cleaning, trellising, pruning, and harvesting, were performed simultaneously in both sectors.

2.3. Microclimate Measurement Equipment

In the centre of each sector, at 2 m height, there was an aspirated radiation shield box EKTRON II-C (Ridder Growing Solutions B.V.) within which there were a Pt1000 IEC 751 class B temperature sensor (Vaisala Oyj, Helsinki, Finland) with a measurement range of -10 to 60 °C and an accuracy of ±0.6 °C, a capacitive humidity sensor HUMICAP 180R (Vaisala Oyj, Helsinki, Finland) with a measurement range of 0-100% and an accuracy of ±3% and a CO2 Probe EE871 (Elektronik Ges M.b.h. Engerwitzdorf, Austria) with a measurement range of 0-2000 ppm and accuracy of ±2% from the measured value (m.v.). Outside climatic conditions were recorded by a meteorological station at a height of 9 m equipped with a BUTRON II (Ridder Growing Solutions B.V.) measurement box with similar temperature and humidity sensors to the inside measurement box.

2.4. Measurement of Photosynthetic Activity

Alternate routes were established between the eastern and western sectors of the greenhouse, encompassing a total of 16 measurement rows (eight in the northern section and eight in the southern section) (

Figure 1b). Photosynthetic activity were measured eight times during the season (at 59,71,83,86,104,108,120 and 125 days after transplanting (DAT)), resulting in a total of 380 measurements per sector. Three plants were selected per row, with two measurements taken for each plant. A portable photosynthesis system TARGAS 1 (PP Systems, Amesbury, USA) was used with a blade clamping chamber equipped with an IRGA sensor for CO

2 and H

2O concentration. The measurement ranges were 0-10000 ppm for CO

2 (accuracy ±1%), 0-75 mbar for H

2O (accuracy ±1%) and 0-3000 μmol m

-2 s

-1 for PAR (accuracy ±10 μmol m

-2 s

-1). The photosynthetic activity (P

A), PAR reaching the leaf surface (Q

leaf), leaf temperature (T

L), CO

2 concentration in the leaf environment (C

L) and transpiration rate (T

R) were measured on mature and fully expanded leaves [

35] on different plants and days during the crop season, under condition of natural inside light and ambient CO

2 concentration, between 10:00 and 15:00 hours [

36].

2.5. Equipment for Crop Development and Yield Measurements

To evaluate crop development, two plant rows (

R1–R2), considered as statistical replicates, were randomly selected in each sector, with eight plants per row (four facing north and four facing south) (

Figure 1c). Growth parameters were measured five times during the season (at 37, 51, 65, 79, and 92 days after transplanting (DAT)), resulting in a total of 40 measurements per sector. Measurements were taken using a tape measure and a digital calliper with a measuring range of 0–150 mm and an accuracy of 0.01 mm (Medid Precision, S.A., Spain). Morphological parameters were recorded on the same plants throughout the season, following the IPGRI [

37] guidelines. The traits assessed included: plant height (P

H) [cm]; plant width (P

W) [cm]; stem diameter (S

D) [mm]; number of nodes (N

N) and internode length (I

L) [cm].

Five harvests were carried out to assess yield. During each harvest, all marketable and non-marketable fruits from the plants in three rows (

R1–R3) per sector were weighed (

Figure 1b). Harvests were carried out weekly, at 98, 105, 113, 120, and 134 DAT. Fruits were weighed with a Mettler Toledo electronic scale (Mettler-Toledo, S.A.E., Spain), with a maximum capacity of 60 kg and a sensitivity of 20 g.

To evaluate fruit quality, three plant rows per treatment were selected (R1-R3). In each row, ten fruits (five from the north-facing side and five from the south-facing side) were sampled at each harvest. The following parameters were measured: fruit weight (WF) [g]: measured with an electronic balance PB3002-L DeltaRange® (Mettler Toledo, S.A., Spain; capacity: 600‒3100 g; sensitivity: 0.01–0.1 g); fruit length (LF) [cm] and fruit width (LF) [cm]: measured with a 150 mm digital calliper (Medid Precisión, S.A., Spain); pericarp thickness (PT) [mm]: measured 25 mm above the fruit base using the same digital calliper; pedicel length (PL) [cm]: measured with a 150 mm digital calliper; soluble solids content (SSC) [°Brix]: measured with a PAL-1 digital refractometer (Atago Co., Ltd., Japan; range: 0.0–53.0%, resolution: 0.1%, accuracy: ±0.2%, at 10–40 °C); fruit firmness (FF) [kg cm−2]: assessed using a digital penetrometer PCE-FM 200 (PCE-Ibérica S.L., Spain; resolution: 10 g/0.05 N; accuracy: ±0.5%); dry matter content (DMC) [%]: determined after oven-drying at 70 °C for 48 h in a convection oven (23–240 I-FD series, Binder GmbH, Germany); fruit colour measured with a portable chroma meter CR-400 (KONICA MINOLTA, USA), using an 8 mm measurement aperture and a 6 silicon photodiode detector system to capture L* (lightness), a* (green to red), and b* (blue to yellow) parameters.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The data analysed correspond to the results obtained during a spring-summer crop cycle in 2024, using three rows of plants as replicates for each treatment at harvest time. Growth and photosynthetic parameters were assessed on 8 and 12 plants, respectively, within each experimental sector. At each harvest, ten pepper fruits were sampled to assess yield quality. Results were analysed using a multifactorial ANOVA procedure [

38] in Statgraphics

® Centurion, considering differences significant at p ≤ 0.05. Mean values were compared using Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test. Factors considered were greenhouse sector (2 levels), plant row (3 levels) and harvest date (5 levels), with crop season treated as an additional factor (1 level). Prior to analysis, the normality of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Homogeneity of variances between the two sectors was assessed using Bartlett’s, Cochran’s and Hartley’s tests. When significant differences in standard deviations were detected, parametric ANOVA was considered inadequate. In such cases, a non-parametric analysis was performed using Friedman’s test, considering each row of plants as a block and harvest date as the repeated measure. The results are represented by box-and-whisker plots [

38].

3. Results

3.1. Climatic Parameter

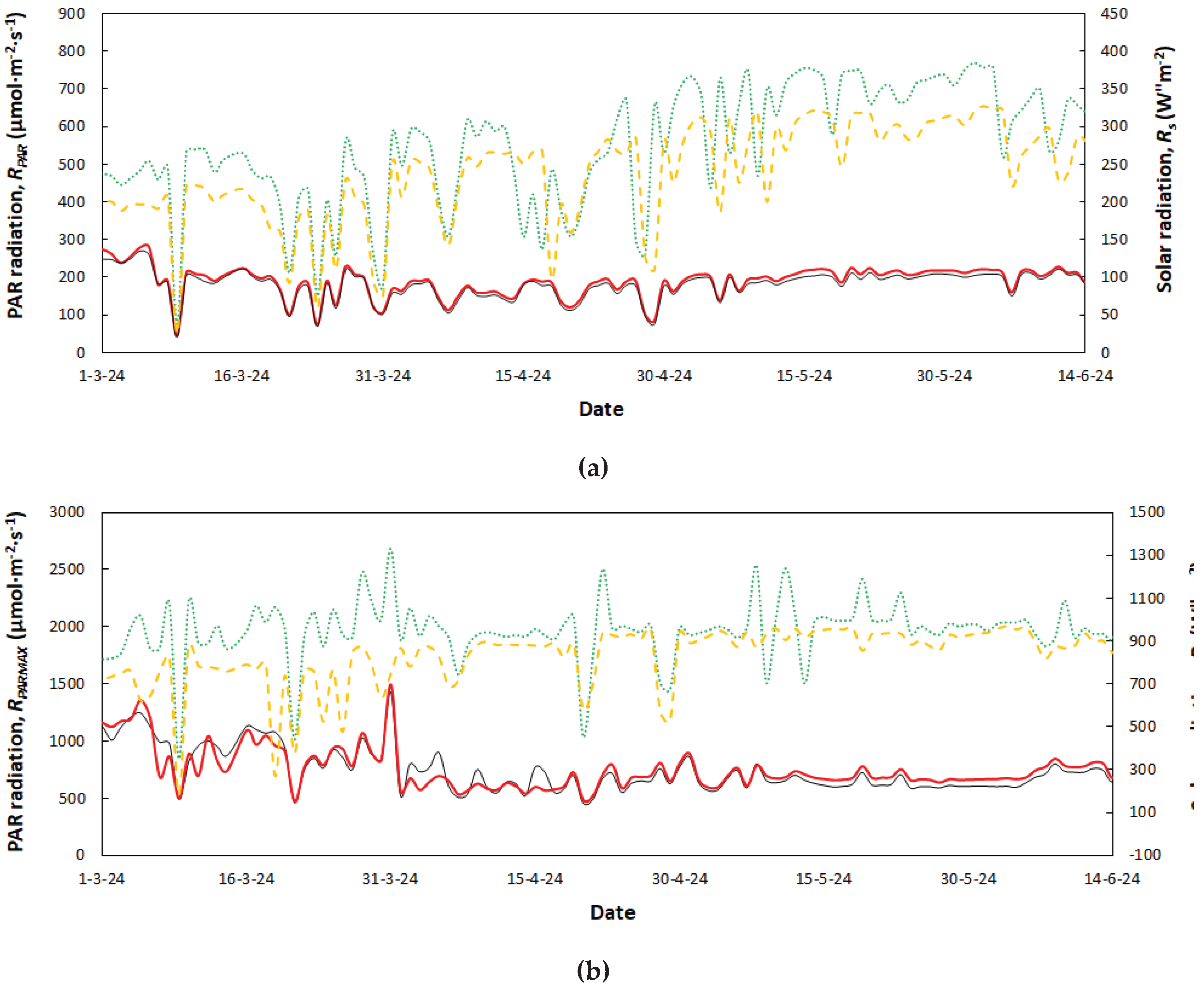

White mulches installed in the western sector of the greenhouse were primarily intended to reflect a greater proportion of the incoming solar radiation. In both experimental sectors, photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) was measured at a central point, while temperature and relative humidity were recorded at three locations: the centre, south, and north of each sector. The PAR radiation values measured in the centre of the eastern and western sectors of the greenhouse consistently showed higher values in the western sectors with white mulch (

Table 2). The use of white plastic mulch was associated with 3.7% higher average PAR values and 2.0% higher maximum values (

Table 2).

The western sector, covered with white polyethylene mulch, consistently exhibited higher levels of PAR compared to the eastern sector, which was mulched with black polypropylene. This pattern was more pronounced in the maximum PAR values, particularly on days with higher external radiation. These results suggest that the use of white polyethylene mulch contributes to an improved light environment within the greenhouse, possibly due to its higher reflectance and superior light diffusion properties. In contrast, the black polypropylene mulch appears to absorb a greater proportion of the incoming radiation, resulting in reduced PAR availability within the crop canopy zone.

The observed increase in PAR at 2 m above ground level may be attributed to the fact that a portion of the radiation reflected by the ground is subsequently reflected a second time upon reaching the inner surface of the plastic roof covering. Although external radiation tends to increase throughout the crop growth cycle, the application of whitewash on the greenhouse roof prior to pepper transplanting combined with dust accumulation due to multiple calima (Saharan dust) episodes leads to a progressive reduction in the maximum radiation available inside the greenhouse (

Figure 3). Similar effects of mulch reflectivity on light distribution have been reported by Díaz-Pérez [

39] and Ilic et al. [

40], who found that reflective or light-coloured mulches increase PAR interception and enhance photosynthetic activity and crop performance.

Overall, the differences in radiation transmission between mulch types underline the importance of ground cover selection as a factor influencing the greenhouse microclimate and, consequently, crop photosynthetic efficiency and yield potential.

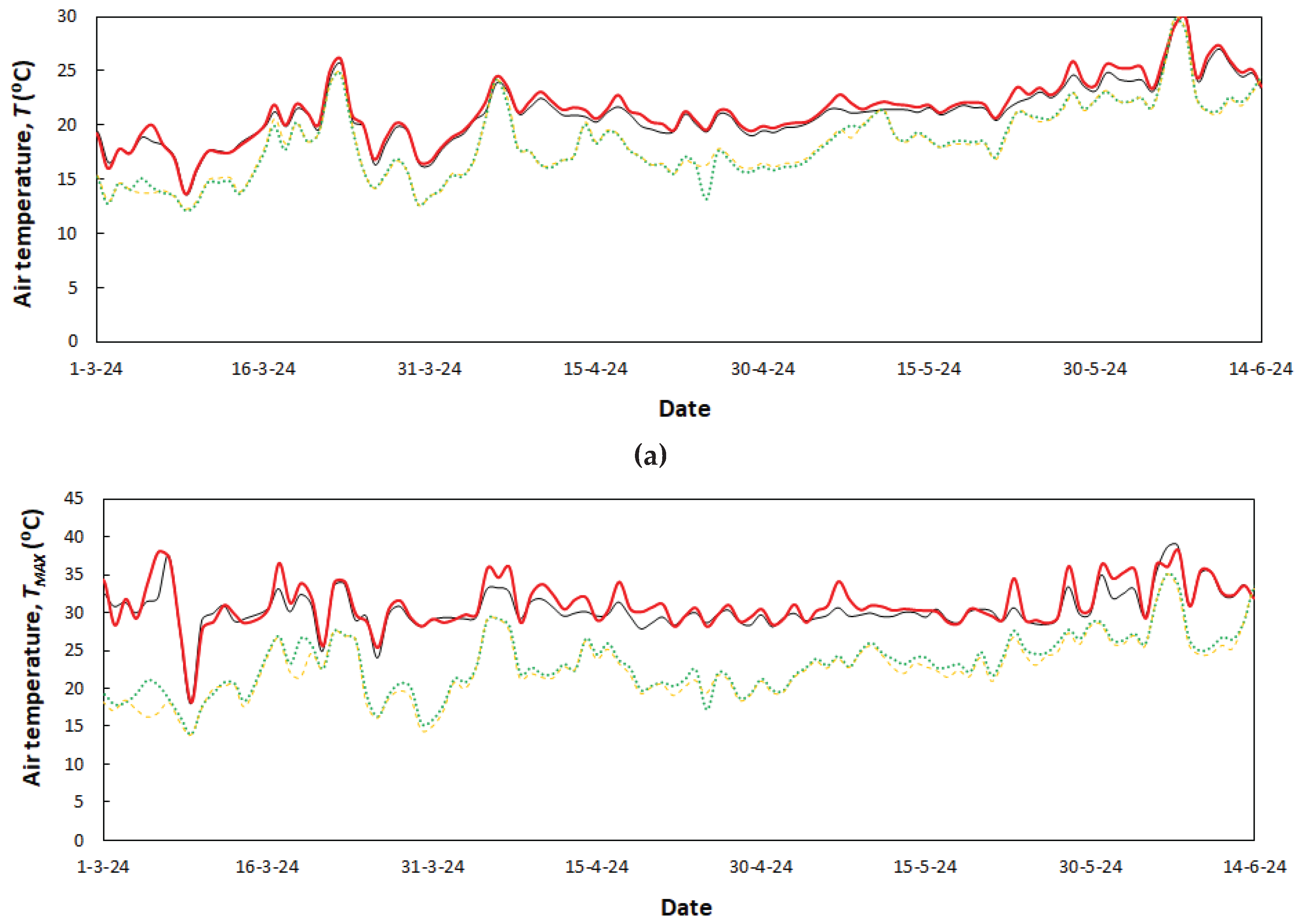

In general, the mean air temperatures at the centre of the four analysed sectors were very similar. However, an increase in maximum temperature values was observed, possibly due to the rise in radiation resulting from the previously discussed double reflection phenomenon. Similarly to the pattern observed in the mean values, the minimum temperatures recorded at night were highly homogeneous across the 12 measurement points (north, centre, and south of each of the four analysed sectors).

Table 3.

Means Tm, minimum TMIN and daily maximum TMAX air temperatures measured in the western (white polyethylene mulch) and eastern (black polypropylene mulch) sectors of the greenhouse.

Table 3.

Means Tm, minimum TMIN and daily maximum TMAX air temperatures measured in the western (white polyethylene mulch) and eastern (black polypropylene mulch) sectors of the greenhouse.

| Sector |

Black polypropylene |

White polyethylene |

| Subsector |

North |

South |

North |

South |

| Mean temperature, Tm [°C] |

21.2 |

21.0 |

21.7 |

21.4 |

| Maximum temperature, TMAX [°C] |

30.9 |

30.8 |

31.9 |

31.2 |

| Minimum temperature, TMIN [°C] |

14.0 |

13.6 |

14.5 |

14.2 |

Throughout the measurement period, the mean internal air temperature in both remained close to 20 °C, which corresponds to the ventilation setpoint (

Figure 4). Despite the gradual increase in external air temperature during the crop cycle, the internal maximum temperatures remained relatively stable due to the high ventilation capacity of the experimental greenhouses where the trials were conducted. This buffering effect reflects the expected performance of controlled ventilation systems and highlights their importance in maintaining optimal thermal conditions [

41,

42].

Inside temperatures were consistently higher than those recorded outdoors, particularly at night and during early morning hours. This demonstrates the thermal insulation effect of the greenhouse structure, which helps avoid temperature extremes and protects crops from thermal stress. The western sector (white polyethylene mulch) exhibited slightly higher mean and maximum air temperatures than the eastern sector (black polypropylene mulch). This can be attributed to the higher reflectivity and diffusive capacity of white mulches, which promote greater light scattering and surface warming during daylight [

23,

40].

In contrast, the eastern sector with black polypropylene mulch showed slightly lower internal air temperatures, likely due to its lower reflectance and higher absorptivity, which concentrates heat near the soil surface rather than distributing it into the air [

39,

43]. Overall, the choice of ground cover significantly influenced thermal behaviour within the greenhouse. White polyethylene mulch improved the luminous and thermal environment, contributing to more favourable conditions for crop development. These effects underline the role of mulch type not only in light distribution but also in moderating temperature dynamics within greenhouse microclimates [

44,

45].

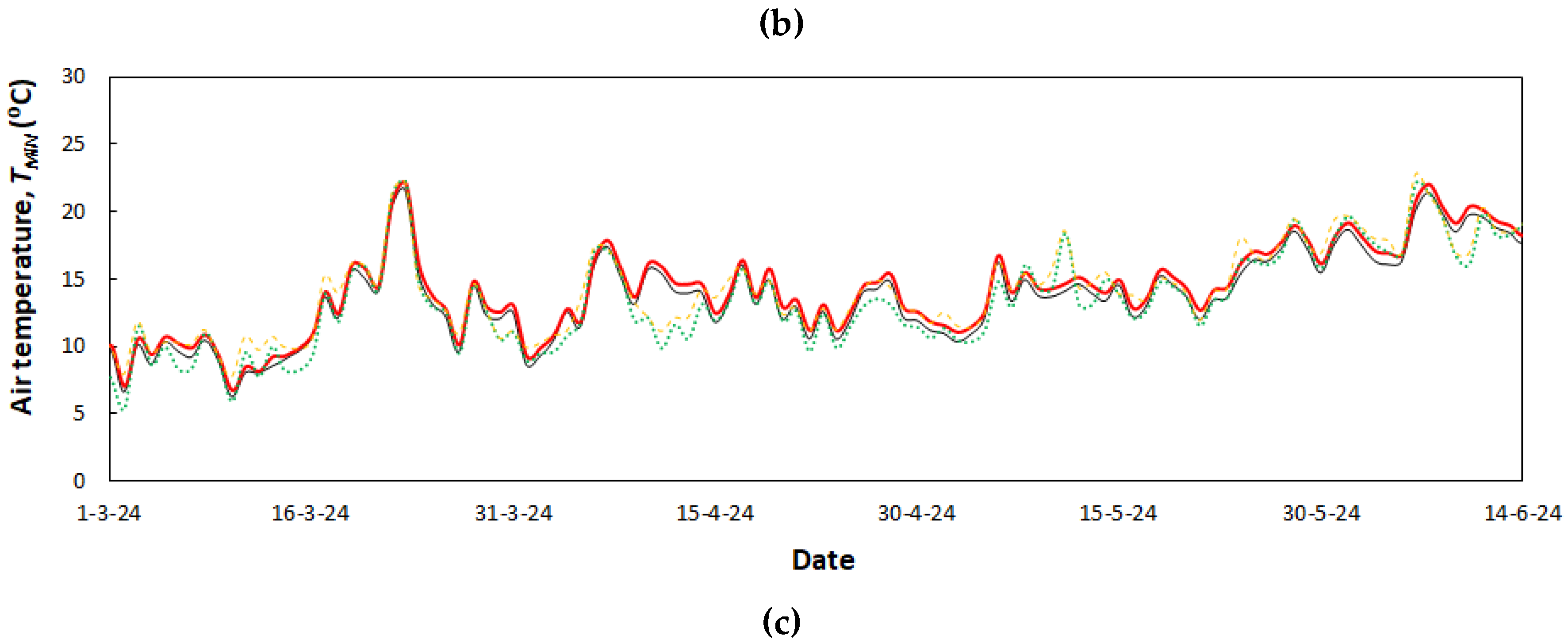

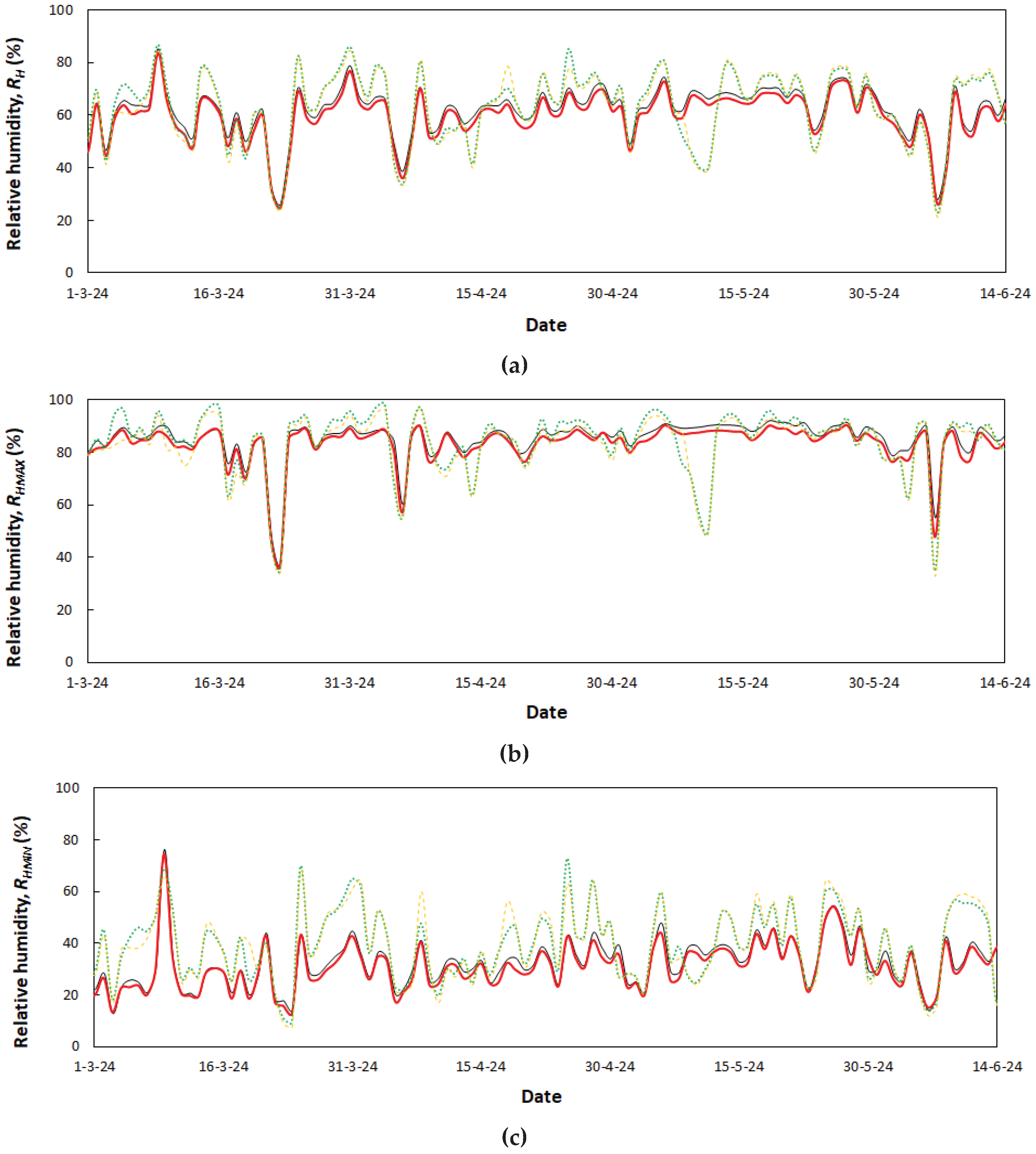

In the case of relative humidity, the mean, maximum and minimum values recorded inside the greenhouse (

Table 4) were very similar.

The daily mean relative humidity values (

Figure 5a) inside the greenhouse remained relatively stable, consistently around 60% throughout the crop cycle, indicating a high degree of environmental regulation. However, the relative humidity trends also showed a strong dependence on external meteorological conditions.

No substantial differences in mean relative humidity were observed between the western sector (white polyethylene mulch) and the eastern sector (black polypropylene mulch). Nonetheless, more distinct differences appeared in the minimum relative humidity values (

Figure 5c), recorded during midday when internal temperatures peaked. The eastern sector consistently exhibited lower minimum relative humidity values, likely due to greater absorption of solar radiation by the black mulch, which tended to increase air temperature and reduce relative humidity (

Figure 4). Conversely, the reflective white mulch helped moderate these extremes by improving light distribution and reducing soil heating, thus maintaining slightly higher RH levels during the warmest periods [

40,

46].

Maximum relative humidity values (

Figure 5b), usually observed during early morning hours, often exceeded 90% in both treatments. Although differences between treatments were small, the western sector occasionally showed slightly higher maximum relative humidity values, possibly due to reduced night-time heat losses associated with the more reflective mulch surface [

39]. Overall, these results highlight that although mulch type has a moderate influence on relative humidity dynamics, the greenhouse internal humidity is largely driven by external climatic variability.

3.2. Agronomic Parameter

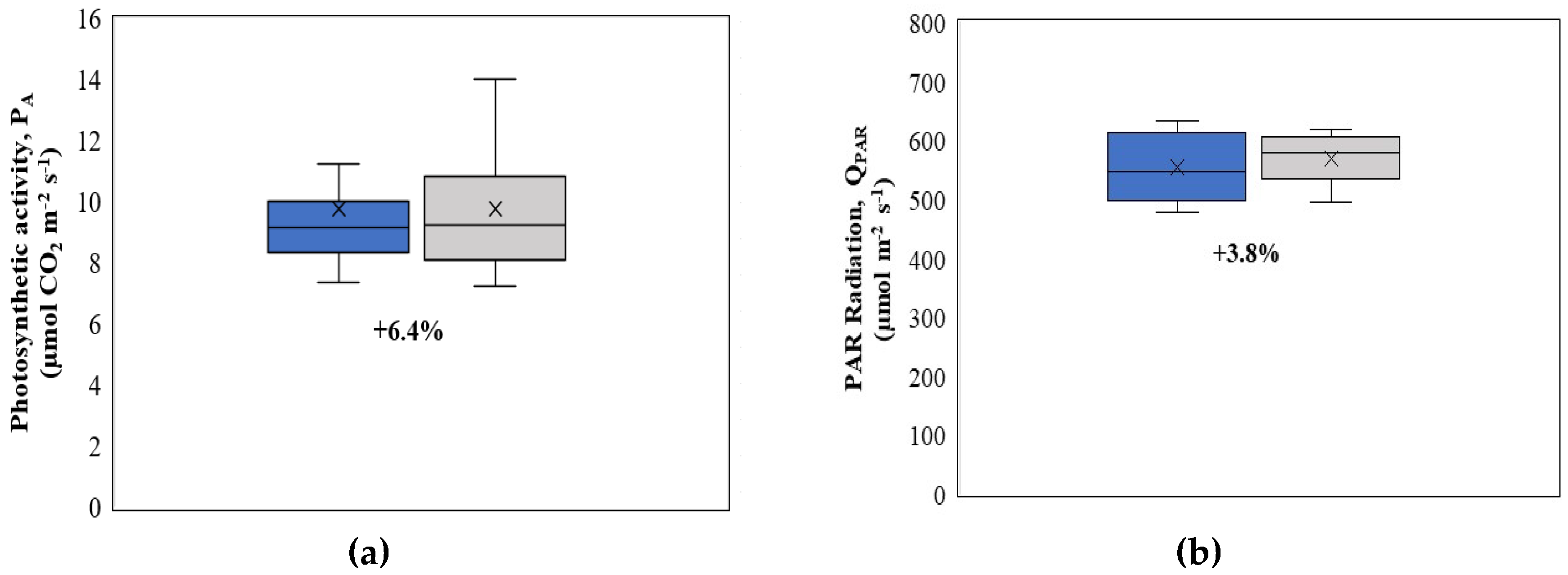

3.2.1. Photosynthetic Activity

The use of white polyethylene mulch in the western sector resulted in a 3.8% increase in photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) at the leaf level compared with the black polypropylene mulch used in the eastern sector (

Figure 6b), with average values of 554.9 μmol m

−2 s

−1 and 534.8 μmol m

−2 s

−1, respectively (

Table 5). This response is consistent with previous reports indicating that light-colored plastic mulches enhance the reflection and diffusion of incoming radiation toward the crop canopy [

23,

39].

Similarly, photosynthetic activity was 3.8% higher in plants grown over white polyethylene mulch (

Figure 6a), reaching a mean value of 9.8 μmol CO

2 m

−2 s

−1, compared with 9.2 μmol CO

2 m

−2 s

−1 in plants grown over black polypropylene (

Table 5). However, the high variability observed in the measurements, reflected in the interquartile ranges and extreme values shown in

Figure 6, prevented the detection of statistically significant differences between treatments (

Table 5), a common outcome in gas-exchange studies conducted under greenhouse conditions [

47].

Leaf temperature was slightly higher in plants grown on black polypropylene mulch (28.9 °C) than in those grown on white polyethylene mulch (28.4 °C), which may be attributed to greater energy absorption by the darker material [

23]. In contrast, leaf-level CO

2 concentration (421.9 and 420.3 ppm), evapotranspiration (3.2 and 3.4 mmol m

−2 s

−1), and stomatal conductance did not differ significantly between treatments (

Table 5), indicating that under the conditions of this study, mulch type primarily influenced radiation availability rather than inducing substantial changes in plant physiological responses.

3.2.2. Plant Morphology

In general, no statistically significant differences were observed among the evaluated morphological parameters. Although slight numerical differences were detected between treatments, none of them reached statistical significance (

Table 6), indicating that the type of mulch did not have a relevant effect on vegetative growth under the conditions evaluated.

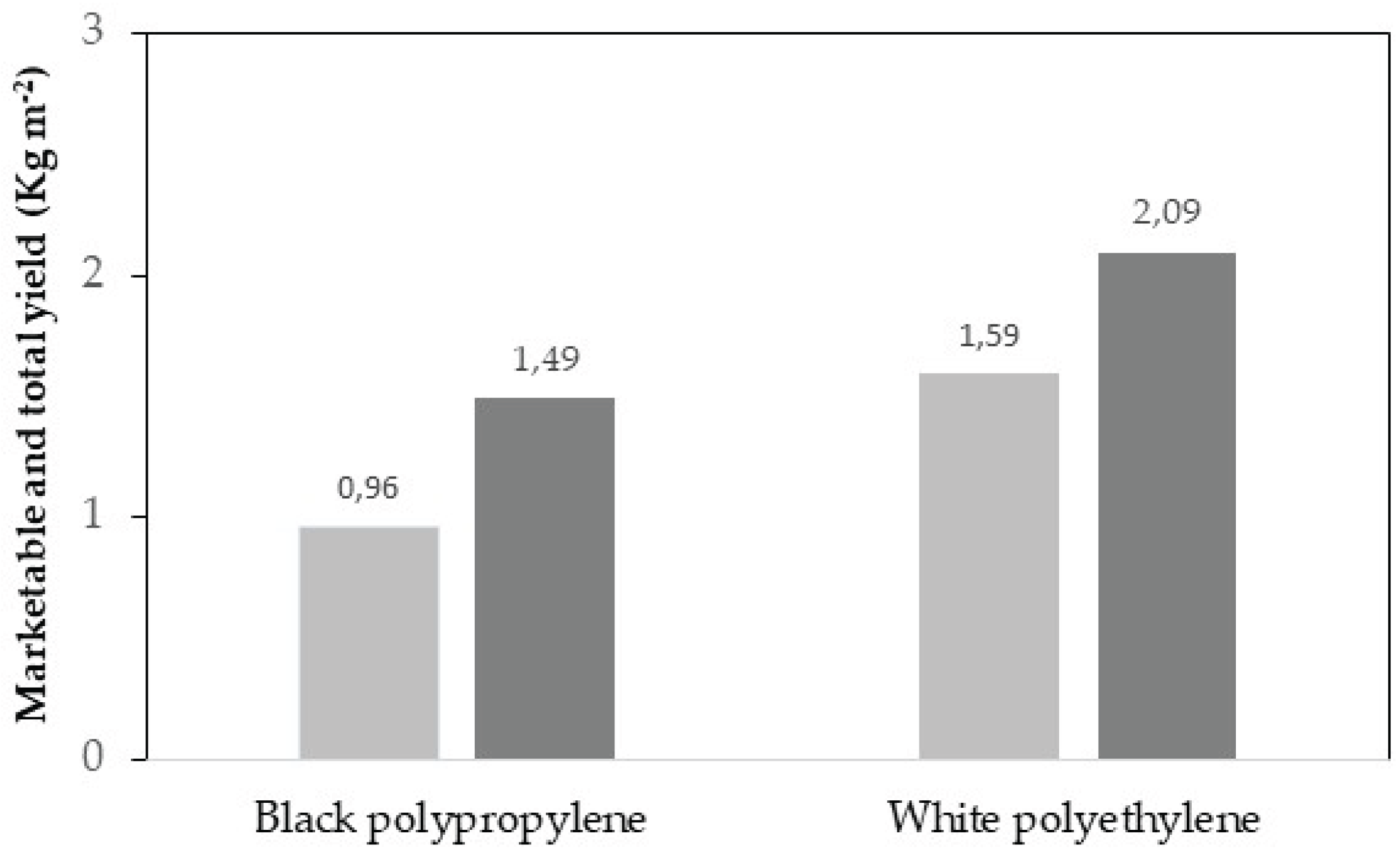

3.2.3. Pepper Yield and Fruit Quality

The analysis of the marketable production of the pepper crop showed an increase of 0.63 kg m

−2 under the white polyethylene mulch compared with the black polypropylene mulch (

Figure 7), which corresponds to an increase of approximately 66% in marketable yield. A similar trend was observed for total yield, with an increase of 0.60 kg m

−2 (around 40%) under white polyethylene mulch. This production improvement may be attributed to the effects of mulch optical properties on the crop microenvironment. Plastic mulches with higher reflectance can modify the light available within the plant canopy and alter root zone temperatures, which in turn can influence plant growth and yield responses [

39]. In bell pepper, both white and reflective mulches have been shown to increase fruit yields compared to black plastic, likely due to increased light reflected into the canopy and enhanced plant physiological activity [

48]. Similarly, reports that white inter-row mulch and reflective mulch treatments produced greater marketable yields than standard black plastic mulch in bell pepper, which supports the yield increases observed here [

49]. Additionally, studies on hot pepper have documented the effects of mulch reflectivity on yield potential, although the magnitude and statistical significance vary with environmental conditions [

50].

In the statistical analysis of fruit quality parameters, statistically significant differences were observed only for fruit weight. The average fruit weight increased from 173.4 g in the East sector, where black polypropylene mulch was used, to 201.3 g in the West sector with white polyethylene mulch, representing an approximate increase of 16% (

Table 7). Similar results were reported by Díaz-Pérez [

39], who indicated that the use of plastic mulches can increase fruit weight in pepper due to improvements in the soil microclimate, although such differences do not always reach statistical significance.

Likewise, fruit length showed a slight increase in the sector with white mulch (8.0 cm compared with 7.8 cm) (

Table 7), which is consistent with studies reporting that plastic films may promote vegetative growth and fruit size without necessarily producing statistically significant differences among treatments [

39,

51].

Regarding fruit width and firmness, values were nearly identical between treatments (

Table 7), which agrees with reports indicating that these parameters are generally less sensitive to the type of mulch used [

52]. Similarly, soluble solids content and dry matter percentage showed only minor variations between sectors, with slightly higher values in the East sector; however, these differences were not statistically significant (

Table 7). Previous studies have shown that although plastic mulching can modify the root-zone microclimate and water availability, such changes do not always result in consistent increases in sugar content or dry matter accumulation in the fruit [

39,

52].

Overall, these results suggest that the use of different plastic mulches under greenhouse conditions may lead to slight variations in fruit quality parameters, but without statistically significant effects. This agrees with previous findings indicating that the main benefits of plastic mulching are more closely related to improvements in yield and microclimate management than to substantial changes in internal fruit quality [

39,

51].

The colorimetric analysis of pepper fruits showed no statistically significant differences between treatments for any of the evaluated parameters (

Table 8). The luminosity coordinate (L*) presented very similar values in fruits harvested under black polypropylene (33.2) and white polyethylene mulch (33.0), indicating comparable surface brightness. Similar results have been reported by Díaz-Pérez [

39], who observed that variations in plastic mulch type did not significantly affect lightness values in pepper fruits grown under protected conditions, despite differences in the radiation environment.

The red–green chromatic coordinate (a*) also showed no significant differences between treatments, with mean values of 25.7 and 24.5 for black and white plastic mulches, respectively. Comparable findings were reported by López-Marín et al. [

52], who observed that mulch-induced changes in microclimate did not significantly modify pigment accumulation related to red coloration in pepper fruits. Likewise, the yellow–blue coordinate (b*) showed only minor variations between sectors, with slightly higher values in fruits grown under white polyethylene, although these differences were not statistically significant. Similar trends were reported by El-Tantawy et al. [

51], who indicated that while mulching can influence fruit development, its effect on colorimetric parameters is often limited.

The chromaticity index (a*/b*), commonly used as an indicator of fruit maturity and carotenoid accumulation, also showed comparable values between treatments. This suggests that, despite the differences in plastic mulch type, fruit ripening and pigment synthesis followed similar patterns in both sectors. These results are consistent with those reported by Díaz-Pérez [

39], who concluded that changes in soil covering materials may influence microclimatic conditions but do not necessarily translate into significant differences in color development of pepper fruits.

4. Conclusions

In the present study, a black polypropylene agrotextile mulch (0.225 μm thick) was compared with a white polyethylene plastic mulch (30 μm thick) in a solar greenhouse in Almería (Spain). The effects of both materials on microclimate, plant development, photosynthetic activity, and productivity of pepper crops were evaluated during a spring–summer growing cycle.

The use of white polyethylene mulch in a multispan greenhouse under Mediterranean conditions improved the internal light environment. It was associated with higher photosynthetically active radiation at both canopy and leaf levels compared with black polypropylene mulch. This enhanced radiation availability resulted in a moderate increase in leaf-level photosynthetic activity (6.4%), although the differences were not statistically significant.

Despite the absence of significant effects on plant morphology and most fruit quality parameters, the white polyethylene mulch led to a substantial increase in pepper yield, with marketable and total production rising by 66% and 40%, respectively. This response may be associated with the greater fruit weight observed in the white mulch treatment, which was 16% higher than in the black mulch treatment and statistically significant. These findings suggest that improvements in radiation distribution and in the root-zone microclimate can translate into meaningful gains in crop productivity.

The reflective mulch slightly increased internal air temperature without exceeding optimal thresholds for pepper cultivation, while relative humidity remained largely unaffected. This indicates that the observed yield enhancement was primarily driven by improved light conditions rather than by thermal stress or changes in atmospheric moisture.

Overall, the use of reflective white polyethylene mulch represents an effective and low-cost agronomic strategy to enhance radiation-use efficiency and yield in greenhouse pepper production systems under passive climate control. Its adoption may contribute to more sustainable horticultural practices by increasing productivity without additional energy inputs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.D.M.-A., A.L.-M. and D.L.V.-M.; methodology, F.D.M.-A., M.H., A.L.-M., D.L.V.-M. and M.Á.M.-T.; formal analysis, M.Á.M.-T., F.D.M.-A. and M.H.; writing original draft preparation, M.Á.M.-T.; review and editing, A.L.-M., F.D.M.-A. and D.L.V- M.; project administration, D.L.V.-M.; funding acquisition, F.D.M.-A. and D.L.V.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is part of the project PID2019-111293RB-I00 “Improving profitability in greenhouses by increasing photosynthetic activity with passive climate control techniques (GREENPHOC)” funded by the National R+D+i Plan Project of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and ERDF funds.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank POLITIV EUROPE, the University of Almería-ANECOOP Foundation for their collaboration and assistance during the development of this study, and the CIAIMBITAL Research Centre.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Qin, W.; Hu, C.; Oenema, O. Soil mulching significantly enhances yields and water and nitrogen use efficiencies of maize and wheat: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, G.; Xu, X.; Huang, Q. Effects of water stress on processing tomatoes yield, quality and water use efficiency with plastic mulched drip irrigation in sandy soil of the Hetao Irrigation District. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 179, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzi, R.; Gholami, M.; Baninasab, B.; Gheysari, M. Evaluation of different mulch materials for reducing soil surface evaporation in semi-arid region. Soil Use Manag. 2017, 33, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, G.; Xu, X.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, Q. Estimating evapotranspiration of processing tomato under plastic mulch using the SIMDualKc model. Water 2018, 10, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Kundu, M.; Sarkar, S. Role of irrigation and mulch on yield, evapotranspiration rate and water use efficiency of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.). Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 98, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalan, A.A.; Nwokeocha, C.U. Effects of furrow irrigation methods, mulching and soil water suction on the growth, yield and water use efficiency of tomato in the Nigerian Savanna. Agric. Water Manag. 2000, 45, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Beltagi, H.S.; Basit, A.; Mohamed, H.I.; Ali, I.; Ullah, S.; Kamel, E.A.R.; Shalaby, T.A.; Ramadan, K.M.A.; Alkhateeb, A.A.; Ghazzawy, H.S. Mulching as a sustainable water and soil saving practice in agriculture: A review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, P.D. An alternative plastic mulching system for improved water management in dryland maize production. Agric. Water Manag. 1995, 27, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.M.; Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.Z. Effects of irrigation before sowing and plastic film mulching on yield and water uptake of spring wheat in semiarid Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2004, 67, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.M.; Liu, X.J.; Li, W.Q.; Li, C.Z. Effect of different mulch materials on winter wheat production in desalinized soil in the Heilonggang region of North China. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2006, 7, 858–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, D.; Nagarajan, S.; Aggarwal, P.; Gupta, V.K.; Tomar, R.K.; Garg, R.N.; Sahoo, R.N.; Sarkar, A.; Chopra, U.K.; Sarma, K.S.S.; Kalra, N. Effect of mulching on soil and plant water status, and the growth and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in a semi-arid environment. Agric. Water Manag. 2008, 95, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubinet, M.; Deltour, J.; de Halleux, D.; Nijskens, J. Stomatal regulation in greenhouse crops: Analysis and simulation. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1989, 48, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, R.; Raza, M.A.S.; Valipour, M.; et al. Potential agricultural and environmental benefits of mulches—A review. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2020, 44, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonachela, S.; Granados, M.; López, J.; Hernández, J.; Magán, J.; Baeza, E.; Baille, A. How plastic mulches affect the thermal and radiative microclimate in an unheated low-cost greenhouse. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2012, 152, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zribi, W.; Faci, J.M.; Aragüés, R. Effects of mulching on soil moisture, temperature, structure and salinity. Inf. Tec. Econ. Agrar. 2011, 107, 148–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Rodríguez, J.; López Hernández, J.C.; Bonachela Castaño, S.; Medrano Cortés, E.; Sánchez-Guerrero Cantó, M.C.; Granados García, M.R.; Fernández del Olmo, P.; Lorenzo Mínguez, P.; Reyes Requena, R.; López Marín, J.; Magán Cañadas, J.; Tapia Pérez, G.; Gil Soria, A.; Salvador Sola, F.J.; Baeza Romero, E.J.; Rubio Fernández, M.; Vargas Valverde, Y. Passive heating systems in Mediterranean greenhouses. CEIA3. 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10835/16610.

- Maiero, M.; Schales, F.D.; Ng, T.J. Genotypes and plastic mulch effects on earliness, fruit characteristics, and yield in muskmelon. HortScience 1987, 22, 945–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wien, H.C.; Minotti, P.L. Growth, yield and nutrient uptake of transplanted fresh-market tomatoes as affected by plastic mulch and initial nitrogen rate. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1987, 112, 759–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenk, M.D. Cultural practices for weed management. In Weed Management for Developing Countries; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1996; Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/t1147s/t1147s00.htm.

- Briassoulis, D. Mechanical behaviour of biodegradable agricultural films under real field conditions. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2006, 91, 1256–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Pérez, J.C.; Batal, K.D. Colored plastic film mulches affect tomato growth and yield via changes in root-zone temperature. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2002, 127, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Jiménez, L.; Zermeno-González, A.; Lozano-Del Río, J.; Cedeño-Rubalcava, B.; Ortega-Ortiz, H. Changes in soil temperature, yield and photosynthetic response of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) under colored plastic mulch. Agrochimica 2008, 52, 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, W.J. Plastics: Modifying the microclimate for the production of vegetable crops. HortTechnology 2005, 15, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.X.; Ma, Y.Q.; Liu, R.Y.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Cheng, W.C.; Dai, X.Z.; Li, X.F.; Zhou, Q.C. Combining ability analyses of net photosynthesis rate in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Agric. Sci. China 2007, 6, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M. Relationships between growth and gas exchange characteristics in some salt-tolerant amphidiploid Brassica species in relation to their diploid parents. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2001, 45, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Bashir, A. Relationship of photosynthetic capacity at the vegetative stage and during grain development with grain yield of two hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars. Eur. J. Agron. 2003, 19, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P. Importance of leaf photosynthetic activity during the reproductive period. Physiol. Plant. 1969, 22, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.T.; Cai, Z.Q.; Yao, T.Q. Vegetative growth and photosynthesis in coffee plants under different watering and fertilization managements in Yunnan, China. Photosynthetica 2007, 45, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.Z.; Li, W.J.; Tang, W.; Zhang, D.M. Early plastic mulching increases stand establishment and lint yield of cotton in saline fields. Field Crops Res. 2009, 111, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonachela, S.; López, J.C.; Hernández, J.; Granados, M.A.; Magán, J.J.; Cabrera-Corral, F.J.; Bonachela-Guhmann, P.; Baille, A. How mulching and canopy architecture interact in trapping solar radiation inside a Mediterranean greenhouse. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 294, 108132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, L.; Dole, J.M. Aluminum foil, aluminum-painted, plastic and degradable mulches increase yields and decrease insect-vectored viral diseases of vegetables. HortTechnology 2003, 13, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kring, J.B.; Schuster, D.J. Management of insects on pepper and tomato with UV-reflective mulches. Fla. Entomol. 1992, 75, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, P.; Sánchez-Guerrero, M.C.; Medrano, E.; Soriano, T.; Castilla, N. Responses of cucumber to mulching in an unheated plastic greenhouse. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2005, 80, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachem, A.; Convertino, F.; Batista, T.; Baptista, F.; Briassoulis, D.; Valera Martínez, D.L.; Moreno Teruel, M.Á.; Papardaki, N.-G.; Ruggiero, G.; Vox, G.; Schettini, E. GIS mapping of agricultural plastic waste in southern Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogewoning, S.W.; Douwstra, P.; Trouwborst, G.; van Ieperen, W.; Harbinson, J. An artificial solar spectrum substantially alters plant development compared with usual climate room irradiance spectra. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, R.; Ozawa, N.; Fujiwara, K. Leaf photosynthesis, plant growth, and carbohydrate accumulation of tomato under different photoperiods and diurnal temperature differences. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 170, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPGRI. Descriptors for Capsicum (Capsicum spp.); International Plant Genetic Resources Institute: Rome, Italy, 1995; Available online: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnacl679.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Statgraphics Technologies. Statgraphics® Centurion 19 User Manual; Statgraphics Technologies: Warrenton, VA, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.statgraphics.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Centurion-XVI-Manual.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Díaz-Pérez, J.C. Bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) grown on plastic film mulches: Effects on crop microenvironment, physiological attributes, and fruit yield. HortScience 2010, 45, 1196–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, Z.S.; Fallik, E.; Milenković, L. Reflective mulches affect quality of watermelon fruits. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 193, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baille, A.; Kittas, C.; Katsoulas, N. Influence of greenhouse ventilation on microclimate and crop transpiration. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2001, 111, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, N.; Hernández, J. Greenhouse technological packages for high-quality crop production. Acta Hortic. 2007, 761, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarara, J.M. Microclimate modification with plastic mulch. HortScience 2000, 35, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, R. Influence of mulch colour and material on soil temperature and plant growth in plasticulture systems: A review. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 291, 108066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rylski, I.; Spigelman, M. Effect of different greenhouse coverings on yield and quality of sweet pepper. Sci. Hortic. 1986, 29, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittas, C.; Katsoulas, N.; Bartzanas, T.; Mermier, M. Greenhouse microclimate and dehumidification effectiveness under different ventilation regimes. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2001, 111, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J.; Gago, J.; Gago, J.; et al. Photosynthesis and photosynthetic efficiencies in crop plants under changing environments. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyochembeng, L.M.; Mankolo, R.N. Colored plastic mulch effects on plant performance and fruit yield in bell pepper. J. Agric. Sci. 2009, 1, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton, M.G.; Handley, D.T. Effects of silver reflective mulch, white inter-row mulch, and plant density on yields of pepper. HortTechnology 2007, 17, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, C.S.; Queeley, G.L. Effect of organic and synthetic mulches on yield of Scotch bonnet pepper. Caribbean Food Crops Soc. Proc. 2001, 37, 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- El-Tantawy, A.S.; et al. Effect of different mulching materials on growth, yield and quality of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Marín, J.; Gálvez, A.; del Amor, F.M.; González, A. Influence of plastic mulching on yield and quality of greenhouse-grown sweet pepper. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 214, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Scheme 3D of the experimental greenhouse (a) and locations of the plant rows (R1-R3) used to measure growth, production and photosynthesis parameters (b).

Figure 1.

Scheme 3D of the experimental greenhouse (a) and locations of the plant rows (R1-R3) used to measure growth, production and photosynthesis parameters (b).

Figure 2.

Pepper crop in the sector East with black polypropylene plastic mulch (a) and in the West sector with white polyethylene plastic mulch.

Figure 2.

Pepper crop in the sector East with black polypropylene plastic mulch (a) and in the West sector with white polyethylene plastic mulch.

Figure 3.

Evolution of mean (a) and maximum (b) PAR radiation values recorded outdoors at 5 m height (····) and inside the greenhouse: eastern sector with black polypropylene mulch (––) and western sector with white polyethylene mulch (––). External solar radiation measured at 9 m height (- - -).

Figure 3.

Evolution of mean (a) and maximum (b) PAR radiation values recorded outdoors at 5 m height (····) and inside the greenhouse: eastern sector with black polypropylene mulch (––) and western sector with white polyethylene mulch (––). External solar radiation measured at 9 m height (- - -).

Figure 4.

Evolution of daily mean (a), maximum (b) and minimum (c) air temperatures recorded outdoors at 9 m height (- - -) and 5 m height (····), inside of greenhouse, eastern sector with black polypropylene mulch (––) and western sector with white polyethylene mulch (––).

Figure 4.

Evolution of daily mean (a), maximum (b) and minimum (c) air temperatures recorded outdoors at 9 m height (- - -) and 5 m height (····), inside of greenhouse, eastern sector with black polypropylene mulch (––) and western sector with white polyethylene mulch (––).

Figure 5.

Evolution of daily mean (a), maximum (b) and minimum (c) relative humidity values recorded at 9 m height (- - -) and 5 m height (····), and inside the greenhouse: eastern sector with black polypropylene mulch (––) and western sector with white polyethylene mulch (––).

Figure 5.

Evolution of daily mean (a), maximum (b) and minimum (c) relative humidity values recorded at 9 m height (- - -) and 5 m height (····), and inside the greenhouse: eastern sector with black polypropylene mulch (––) and western sector with white polyethylene mulch (––).

Figure 6.

PAR radiation (a) and photosynthetic activity (b) of pepper crops with white polyethylene (■) and black polypropylene mulch (■). Mean value (×) and median (—) with the lines indicating the maximum and minimum values measured (I) and values between the 25th and 75th percentile (▯).

Figure 6.

PAR radiation (a) and photosynthetic activity (b) of pepper crops with white polyethylene (■) and black polypropylene mulch (■). Mean value (×) and median (—) with the lines indicating the maximum and minimum values measured (I) and values between the 25th and 75th percentile (▯).

Figure 7.

Marketable (■) and total (■) yield of pepper crops in the East sector with black polypropylene mulch and in the West sector with white polypropylene mulch.

Figure 7.

Marketable (■) and total (■) yield of pepper crops in the East sector with black polypropylene mulch and in the West sector with white polypropylene mulch.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the two sectors of the experimental greenhouse. Greenhouse soil surface SC (m2), roof vents surface SRV (m2), side vents surface SSV and ventilation surface/ greenhouse surface ratio SV/SC (%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the two sectors of the experimental greenhouse. Greenhouse soil surface SC (m2), roof vents surface SRV (m2), side vents surface SSV and ventilation surface/ greenhouse surface ratio SV/SC (%).

| Sector |

Plastic mulch |

Dimensions |

SC

|

SRV

|

SSV

|

SRV+SSV/SC

|

| East |

Black polypropylene |

18 m × 25 m |

450 |

40.50 |

127.26 |

28.3 |

| West |

White polyethylene |

18 m × 20 m |

360 |

31.50 |

70.40 |

28.3 |

Table 2.

Means RPARm and daily maximum RPARMAX, values of photosynthetically active radiation measured at the centre of the western and eastern greenhouse sectors.

Table 2.

Means RPARm and daily maximum RPARMAX, values of photosynthetically active radiation measured at the centre of the western and eastern greenhouse sectors.

| Sector |

Black polypropylene |

White polyethylene |

| RPARm [μmol·m-2·s-1] |

183.3 |

190.1 |

| RPARMAX [μmol·m-2·s-1] |

740.7 |

756.0 |

Table 4.

Means Hm, minimum HMIN and daily maximum HMAX relative humidity values measured in the western (white polyethylene mulch) and eastern (black polypropylene mulch) sectors of the greenhouse.

Table 4.

Means Hm, minimum HMIN and daily maximum HMAX relative humidity values measured in the western (white polyethylene mulch) and eastern (black polypropylene mulch) sectors of the greenhouse.

| Sector |

Black polypropylene |

White polyethylene |

| Subsector |

North |

South |

North |

South |

| Mean relative humidity, Hm [%] |

61.6 |

62.1 |

61.1 |

62.1 |

| Maximum relative humidity, HMAX [%] |

84.9 |

85.6 |

84.9 |

86.1 |

| Minimum relative humidity, HMIN [%] |

32.3 |

32.6 |

31.4 |

32.3 |

Table 5.

Average values (±standard deviations) of the measurements made on the leaves of plants grown in the two greenhouse sectors with different plastic mulch. Photosynthetic activity PA [µmol CO2 m−2 s−1], PAR radiation QPAR [µmol m−2 s−1], leaf temperature TL [°C], CO2 concentration CL [ppm], evapotranspiration EL [mmol m−2 s−1] and stomatal conductance CE [mol m−2 s−1].

Table 5.

Average values (±standard deviations) of the measurements made on the leaves of plants grown in the two greenhouse sectors with different plastic mulch. Photosynthetic activity PA [µmol CO2 m−2 s−1], PAR radiation QPAR [µmol m−2 s−1], leaf temperature TL [°C], CO2 concentration CL [ppm], evapotranspiration EL [mmol m−2 s−1] and stomatal conductance CE [mol m−2 s−1].

| Sectors |

Plastic mulch |

PA |

QPAR |

TL |

CL |

EL |

CE |

| East |

Black polypropylene |

9.2a± 1.1 |

534.8a± 54.4 |

28.2a± 1.4 |

421.9a± 5.8 |

3.2a± 0.7 |

299.1a±105.6 |

| West |

White polyethylene |

9.8a± 2.0 |

554.9a± 56.8 |

29.8a± 1.5 |

420.3a± 5.4 |

3.4a±0.7 |

261.7a±104.5 |

Table 6.

Statistical analysis of the growth parameters of the pepper crop (mean values ± standard deviation) in the two sectors of the experimental greenhouse. Plant height (HP) [cm], plant width (PW) [cm], stem diameter (DS) [mm]; number of nodes (NN), internodes length (IL) [cm], leaf length (LL) [cm], leaf width (LW) [cm].

Table 6.

Statistical analysis of the growth parameters of the pepper crop (mean values ± standard deviation) in the two sectors of the experimental greenhouse. Plant height (HP) [cm], plant width (PW) [cm], stem diameter (DS) [mm]; number of nodes (NN), internodes length (IL) [cm], leaf length (LL) [cm], leaf width (LW) [cm].

| Sectors |

Plastic mulc |

HP |

WP |

DS |

NN |

IL |

LL |

LW |

| East |

Black polypropylene |

73.2a±23.6 |

46.6a± 12.3 |

12.4a±2.6 |

10.4a±2.9 |

6.4a±1.9 |

16.5a±3.1 |

9.4a±1.9 |

| West |

White polyethylene |

66.9a± 21.5 |

45.1a±12.3 |

12.2a±2.9 |

10.1a±2.7 |

6.7a±2.3 |

15.9a±3.5 |

9.0a±1.7 |

Table 7.

Average values (±standard deviations) of the production quality parameters measured for plants grown in the two greenhouse sectors with different plastic mulch. Weight WF [g], length [cm], width WiF [mm], firmness FF [kg cm], soluble solids content SSC [° Brix] and dry matter DM [%].

Table 7.

Average values (±standard deviations) of the production quality parameters measured for plants grown in the two greenhouse sectors with different plastic mulch. Weight WF [g], length [cm], width WiF [mm], firmness FF [kg cm], soluble solids content SSC [° Brix] and dry matter DM [%].

| Sectors |

Plastic mulch |

WF |

LF |

WiF |

FF |

SSC |

DM

|

| East |

Black polypropylene |

173.4a± 32.8 |

7.8a± 1.1 |

81.9a± 6.3 |

2.7a± 0.6 |

7.8a± 1.8 |

9.3a±1.8 |

| West |

White polyethylene |

201.3b± 28.4 |

8.0a± 0.9 |

81.0a± 9.6 |

2.7a± 0.9 |

6.5a±1.4 |

8.7a±1.7 |

Table 8.

Average values (±standard deviations) of the color characteristics measured in pepper fruits harvested in sectors with different plastic mulch. Colorimetric coordinates corresponding to the luminosity L*, the red/green color component a*, the yellow/blue color component b*, and the chromaticity a*/b*.

Table 8.

Average values (±standard deviations) of the color characteristics measured in pepper fruits harvested in sectors with different plastic mulch. Colorimetric coordinates corresponding to the luminosity L*, the red/green color component a*, the yellow/blue color component b*, and the chromaticity a*/b*.

| Sectors |

Plastic mulch |

L* |

a* |

b* |

a*/b* |

| East |

Black polypropylene |

33.2a± 2.7 |

25.7a± 5.9 |

24.9a± 9.9 |

1.2a± 0.5 |

| West |

White polyethylene |

33.0a± 2.7 |

24.5a± 8.5 |

26.4a± 15.3 |

1.1a± 0.4 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).