1. Introduction

Indoor insecticide use remains widespread across residential, commercial, and occupational environments. Synthetic pyrethroids are frequently chosen because of their high insecticidal efficacy, broad availability, and favorable safety profile compared with older pesticide classes [

1,

2,

3]. Consequently, indoor pyrethroid spraying has become a routine component of pest management programs in many buildings where large numbers of individuals may experience repeated exposure over extended periods. While acute toxicity and neurotoxic manifestations at high doses are well described [

8,

9], the potential health implications of

chronic low-dose exposure in indoor settings remain less clearly defined and are not adequately addressed in current safety frameworks.

A central limitation of most indoor pesticide safety protocols is their focus on

spray-time exposure and short-term re-entry precautions designed mainly to prevent acute intoxication [

4,

5]. These procedures typically emphasize evacuation during spraying, temporary ventilation, and avoidance of treated areas for a limited time. However, indoor environments differ fundamentally from outdoor application contexts because they contain multiple

exposure reservoirs that can retain residues for long periods. Carpets, textiles, porous materials, and settled dust can accumulate pyrethroid residues and sustain low-level exposure long after application—especially when spraying is repeated and cleaning or ventilation is inconsistent [

3,

6,

7].

This review is particularly relevant for occupational medicine practice, because repeated indoor spraying often occurs without standardized clinical surveillance or spraying-frequency guidelines.

In enclosed buildings with central

heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems, exposure dynamics are further influenced by airflow, recirculation, filtration efficiency, and redistribution of airborne particles [

26]. Even if air-conditioning is switched off during spraying, residues deposited on surfaces and dust reservoirs can later re-enter the breathing zone through resuspension, occupant movement, or ventilation restart. Wall-to-wall carpeting functions as an efficient sink for semi-volatile residues, enabling persistence within dust matrices and repeated re-aerosolization during routine activities such as walking or cleaning. Collectively, these processes support a

chronic exposure paradigm that extends well beyond the initial spray event [

3,

6].

To conceptualize these complex, time-extended exposure processes, the

exposome framework provides a useful lens. The exposome refers to the totality of environmental exposures and associated biological responses over time, emphasizing that chronic disease risk is influenced by repeated low-dose exposures, chemical mixtures, and multiple exposure routes [

22,

23,

24]. Applying this concept, we propose an

indoor pyrethroid exposome framework—defined as the cumulative indoor exposure environment generated by repeated spraying, residue persistence in dust and surfaces, and resuspension or redistribution within the built environment.

Mechanistically, Type II pyrethroids such as lambda-cyhalothrin act primarily by modulating voltage-gated sodium channels, leading to neuronal hyperexcitability [

8,

9]. However, growing evidence indicates that chronic low-dose exposure may also trigger broader biological pathways, including

mitochondrial dysfunction,

oxidative stress, and

inflammatory signaling, which are relevant across neurological, endocrine, and cardiovascular systems [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

27,

31]. Oxidative stress, in particular, represents a cross-system mechanism linking prolonged exposure to neurotoxicity, endothelial dysfunction, and thyroid disruption. Because thyroid hormone synthesis is intrinsically oxidative, additional oxidative burden may plausibly influence thyroid homeostasis in susceptible individuals [

13,

14,

15,

31].

Despite increasing recognition of pyrethroid residues in indoor dust [

2,

3,

6,

7] and expanding interest in endocrine and cardiometabolic effects of environmental chemicals [

13,

14,

15,

16,

27], a unified framework that integrates

dust-reservoir persistence,

resuspension-driven chronic exposure, and

multi-system mechanistic pathways remains underdeveloped—especially in occupational settings characterized by enclosed, centrally air-conditioned, and carpeted environments. This gap limits the effectiveness of current monitoring strategies and risk assessment models, which often overlook residue-driven re-exposure loops, vulnerable populations, and built-environment factors influencing exposure intensity.

Accordingly, this review introduces an integrative indoor pyrethroid exposome model that synthesizes evidence on residue persistence, dust and surface accumulation, resuspension pathways, and mechanistic links to thyroid, neurological, and cardiovascular dysregulation. The review also identifies key research and policy priorities for improved occupational surveillance, including residue monitoring, ventilation verification, and biomonitoring approaches to support early detection and prevention of chronic health effects among potentially exposed workers.

1.2. Rational and Knowledge Gap

Despite widespread use of pyrethroid insecticides indoors, existing safety frameworks address only acute exposure. Real-world conditions—such as repeated high-dose spraying in enclosed buildings with recirculated air and textile surfaces—illustrate the absence of evidence-based guidance on safe application frequency, residue persistence, and chronic health effects. This regulatory and knowledge gap places workers and occupants at risk of long-term toxicity, underscoring the need to incorporate chronic exposure considerations into pesticide safety guidelines [

33,

34].

1.3. Research Question

What mechanistic pathways link repeated indoor pyrethroid spraying in enclosed, carpeted environments to chronic toxicity in hepatic, thyroid, neurological, and immune systems, and why do current safety frameworks lack clear guidance for exposure frequency and long-term health protection?

2. Methods

This article represents a mechanistic narrative review developed through a structured and focused examination of the scientific literature. Relevant studies were identified through comprehensive searches of the PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science databases, using combinations of keywords encompassing pyrethroids (including lambda-cyhalothrin), indoor spraying, residue persistence, wall-to-wall carpeting, house dust, surface contamination, resuspension or re-aerosolization, heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems, biomonitoring, and mechanistic endpoints related to thyroid, neurological, hepatic, cardiovascular, and immune outcomes.

Only peer-reviewed articles published in English were included. Priority was given to studies that investigated the persistence and accumulation of pyrethroid residues in indoor dust, carpets, and surfaces; explored resuspension and redistribution processes within enclosed or air-conditioned environments; reported human biomonitoring or epidemiological associations with endocrine, neurotoxic, cardiovascular, or inflammatory effects; or provided mechanistic evidence elucidating processes such as voltage-gated sodium channel modulation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, endocrine disruption, inflammatory signaling, and vascular impairment.

Reference lists of key publications were further examined to capture additional relevant studies not retrieved through database searches. The collected evidence was analyzed qualitatively, with an emphasis on identifying mechanistic convergence across environmental exposure science, human biomonitoring, and experimental toxicology. This narrative approach was chosen to integrate multidisciplinary findings and to construct a coherent mechanistic framework where quantitative synthesis was not feasible due to the diversity of study designs and endpoints.

3. Scientific Background: Pyrethroids, Indoor Use, and the Rationale for an “Indoor Pyrethroid Exposome”

Synthetic pyrethroids are the predominant class of insecticides used for indoor pest control due to their high insecticidal potency and comparatively low acute mammalian toxicity relative to older pesticide groups [

1,

2,

3,

8]. Developed as photostable analogs of natural pyrethrins, these agents are widely applied in residential, commercial, and occupational environments. Commercial formulations vary in active ingredients and solvents, influencing volatility, residue behavior, and human exposure potential [

3,

6].

Toxicologically, pyrethroids are categorized as

Type I or

Type II compounds depending on their chemical structure and neurotoxic profile. Type II agents—such as lambda-cyhalothrin, cypermethrin, and deltamethrin—contain an α-cyano group that prolongs the opening of voltage-gated sodium channels, leading to neuronal hyperexcitability and characteristic neurotoxic symptoms [

8,

9]. Although this mechanism explains acute toxicity, chronic low-dose exposure introduces additional biological stressors, including

mitochondrial dysfunction,

oxidative imbalance, and

inflammatory signaling, that extend beyond classical neurotoxicity [

10,

11,

12,

27,

31].

Indoor environments alter pesticide behavior compared with outdoor settings. Limited photodegradation and air exchange, combined with the hydrophobicity of pyrethroids, favor

adsorption onto dust and textiles and

long-term residue persistence [

3,

6,

7]. Carpets, curtains, and porous materials serve as efficient sinks, and in buildings with central HVAC systems, recirculated air can redistribute residue-laden dust throughout occupied zones [

19,

26]. These features enable

chronic, low-level re-exposure even when acute exposure controls—such as short-term evacuation and ventilation—are followed correctly.

The

resuspension of dust particles during normal activities (e.g., walking, cleaning, or ventilation restart) is a key driver of ongoing exposure. This process allows residues to re-enter the breathing zone repeatedly, maintaining background exposure that may persist for weeks or months after spraying [

6,

7]. Such exposure loops are not addressed in standard risk-management frameworks that focus primarily on the spray event and immediate re-entry period [

33,

34].

The

exposome concept provides a unifying framework to interpret these chronic processes. The exposome encompasses the totality of environmental exposures and biological responses across the life course [

22,

23,

24]. Applying this lens, the

indoor pyrethroid exposome describes the cumulative exposure environment created by recurrent spraying, residue persistence in dust and surfaces, resuspension-driven re-exposure, and building-specific modifiers such as HVAC operation and carpeting. This framework emphasizes that repeated, low-dose exposure can plausibly activate overlapping mechanistic pathways—oxidative stress, endocrine disruption, neuroimmune signaling, and vascular dysregulation—relevant to chronic multisystem toxicity [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

27,

31].

Furthermore, chronic chemical exposures contribute to

building-related symptom complexes such as

Sick Building Syndrome (SBS), characterized by headaches, mucosal irritation, fatigue, and cognitive difficulty that improve upon leaving the environment [

19,

20]. Recurrent pesticide use within enclosed, carpeted workplaces may represent an unrecognized component of SBS, sustained by residue reservoirs and inadequate ventilation. Recognizing this link reinforces the need for comprehensive indoor-air management and chronic-exposure assessment rather than reliance on acute toxicity models.

In summary, pyrethroids’ physicochemical persistence, interaction with dust and carpets, and recirculation through HVAC systems create a chronic exposure environment in which residues persist long after spraying. This justifies adopting an indoor pyrethroid exposome framework to connect exposure dynamics with biological mechanisms of long-term toxicity and to guide the development of evidence-based occupational safety standards.

4. The Indoor Pyrethroid Exposome: Carpets, Dust Reservoirs, Resuspension, and HVAC Redistribution

Indoor environments profoundly influence the persistence and movement of pyrethroid residues. Unlike outdoor applications, where sunlight, rainfall, and air exchange promote degradation, enclosed workplaces provide minimal dilution and photodegradation potential [

3,

6]. The hydrophobic nature of pyrethroids favors their adsorption to dust particles, fibers, and porous surfaces such as carpets and upholstered furniture [

6,

7]. Over time, these materials act as

reservoirs, storing residues that can later re-enter the breathing zone or contact surfaces through resuspension.

Carpeted flooring plays a particularly significant role in this process. Wall-to-wall carpets possess large surface areas and complex fiber structures that trap fine particulate matter and semi-volatile compounds [

3,

6,

7]. Residues accumulate within the dust matrix and persist for weeks or months, depending on compound type, cleaning frequency, and ambient temperature. Mechanical disturbance from walking, vacuuming, or air flow readily

resuspends contaminated dust, maintaining background concentrations that are decoupled from recent spraying events.

Repeated applications, especially in poorly ventilated or heavily carpeted areas, therefore sustain a

chronic exposure cycle even when spraying frequency appears moderate [

6,

7,

33].

Central heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems add a further dimension to exposure dynamics. During operation, HVAC units can draw dust from contaminated zones, redistribute particles through ducts, and deposit residues on filters and interior surfaces [

19,

26]. Partial recirculation of air increases the potential for

redistribution rather than elimination of contaminants. If maintenance is infrequent or filters are inefficient, accumulated residues may be released during subsequent air-handling cycles. This mechanism extends exposure both spatially (to untreated rooms) and temporally (long after initial spraying). Few studies have quantitatively assessed HVAC-mediated redistribution, representing a

major evidence gap in chronic indoor exposure assessment [

26,

33].

Resuspension and redistribution together produce a

“dust-reservoir-driven” exposure loop that challenges the conventional view of pesticide safety based solely on immediate post-spray measurements. Occupants in such settings experience repeated low-level exposure through inhalation of particle-bound residues, dermal contact with contaminated surfaces, and inadvertent ingestion via hand-to-mouth activity. Existing occupational guidelines largely ignore these pathways, focusing instead on direct spray contact and acute toxicity [

33,

34]. Integrating dust-reservoir dynamics and HVAC behavior into risk-assessment models is therefore essential for accurate estimation of chronic indoor exposure and for the design of effective mitigation strategies.

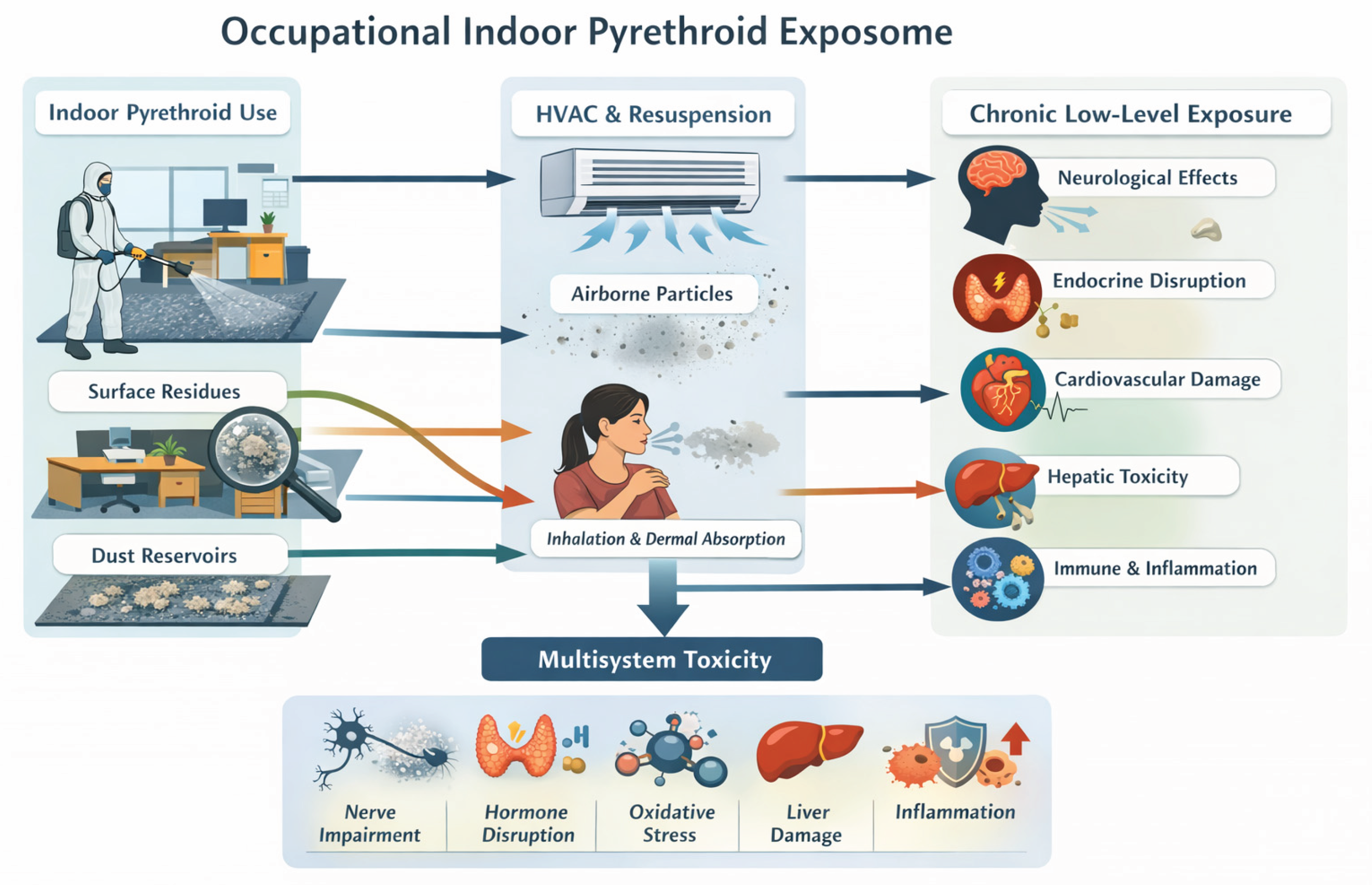

Figure 1.

Occupational Indoor Pyrethroid Exposome. Schematic representation of the occupational indoor pyrethroid exposome. Indoor spraying leads to residue accumulation on surfaces and within dust reservoirs such as carpets and textiles. Subsequent resuspension and HVAC-mediated redistribution create chronic low-level exposure pathways through inhalation, dermal contact, and incidental ingestion. These recurrent exposures can induce multisystem biological effects, including neurotoxicity, endocrine disruption, cardiovascular dysfunction, hepatic stress, and immune activation. Original figure created by the author.

Figure 1.

Occupational Indoor Pyrethroid Exposome. Schematic representation of the occupational indoor pyrethroid exposome. Indoor spraying leads to residue accumulation on surfaces and within dust reservoirs such as carpets and textiles. Subsequent resuspension and HVAC-mediated redistribution create chronic low-level exposure pathways through inhalation, dermal contact, and incidental ingestion. These recurrent exposures can induce multisystem biological effects, including neurotoxicity, endocrine disruption, cardiovascular dysfunction, hepatic stress, and immune activation. Original figure created by the author.

5. Mechanistic Pathways of Chronic Toxicity

Pyrethroids exert toxicity primarily through interference with neuronal ion channels, but chronic low-dose exposure engages a broader range of biological mechanisms that extend beyond acute neuroexcitation. These mechanisms collectively explain the multisystem effects reported in experimental and human studies.

5.1. Neurotoxicity and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Both Type I and Type II pyrethroids act on voltage-gated sodium channels, delaying their inactivation and causing repetitive neuronal firing [

8,

9]. Type II compounds such as lambda-cyhalothrin also affect calcium and chloride channels, further disturbing membrane potential. With repeated low-level exposure, secondary effects emerge: oxidative stress, mitochondrial membrane depolarization, and impaired ATP production [

10,

11,

12]. These changes contribute to neuronal fatigue, altered neurotransmitter metabolism, and cognitive or mood disturbances consistent with chronic exposure symptoms observed in workers [

16,

17]. In experimental models, persistent mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation link pyrethroid exposure to neurodegeneration-like outcomes [

10,

11,

12,

27].

5.2. Hepatotoxicity

The liver is a major site of pyrethroid biotransformation through cytochrome P450-mediated oxidation and ester hydrolysis. Prolonged exposure can induce hepatic enzyme activity, increasing serum ALT, AST, and γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels [

11,

25]. Studies in animals show hepatocellular hypertrophy and oxidative injury following chronic low-dose intake of lambda-cyhalothrin or cypermethrin [

11,

12]. Mechanistically, hepatotoxicity arises from mitochondrial ROS generation, lipid peroxidation, and depletion of antioxidant defenses, leading to metabolic stress and potential progression toward steatohepatitis-like pathology [

11,

12,

25]. These findings are consistent with occupational reports of elevated liver enzymes among chronically exposed workers.

5.3. Endocrine and Thyroid Disruption

Pyrethroids can alter endocrine homeostasis by interfering with thyroid hormone synthesis, transport, and metabolism. Several studies demonstrate inverse or nonlinear associations between urinary pyrethroid metabolites and circulating T3/T4 levels in adults [

13,

14,

15]. Proposed mechanisms include oxidative inhibition of thyroid peroxidase, disruption of deiodinase enzymes, and competitive binding of pyrethroid metabolites to transthyretin, the thyroid hormone transport protein [

31]. Chronic oxidative burden may further exacerbate thyroid vulnerability, particularly in individuals with pre-existing endocrine or autoimmune disorders [

13,

14,

15,

31].

5.4. Cardiovascular and Vascular Effects

Epidemiological findings suggest associations between chronic pyrethroid exposure and increased cardiovascular risk, including hypertension and endothelial dysfunction [

16,

33]. Mechanistically, vascular effects may stem from oxidative stress–induced nitric oxide depletion, mitochondrial impairment in vascular smooth muscle, and autonomic imbalance secondary to neuronal hyperexcitability [

16,

17,

33]. These processes may collectively contribute to altered heart-rate variability and inflammatory vascular responses observed in chronically exposed populations.

5.5. Immune and Inflammatory Pathways

Chronic low-dose exposure can shift immune balance toward a pro-inflammatory state, characterized by elevated cytokine production and activation of microglia or peripheral macrophages [

10,

11,

27]. Experimental evidence indicates that pyrethroids enhance oxidative and inflammatory signaling through NF-κB and MAP-kinase pathways. Such persistent low-grade inflammation may underlie fatigue, allergic-like symptoms, and susceptibility to autoimmune dysregulation in exposed workers [

19,

20,

27].

Summary

The combined activation of oxidative, inflammatory, endocrine, and mitochondrial pathways provides a coherent explanation for the multisystem toxicity observed with chronic indoor pyrethroid exposure. These overlapping mechanisms demonstrate how repeated low-dose exposures—typical in enclosed, carpeted, and HVAC-controlled workplaces—can lead to cumulative hepatic, thyroid, neurological, cardiovascular, and immune dysfunctions despite the absence of overt acute poisoning. The main mechanistic pathways and their biological targets are summarized in

Table 1.

6. Human Evidence: Biomonitoring and Epidemiological Findings

6.1. Biomonitoring of Indoor Exposure

Studies from many countries have found pyrethroid residues or metabolites in people who live or work indoors, even when they are not directly involved in spraying [

1,

2,

3,

5]. The main urinary markers—3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA) and cis/trans-DCCA—show that exposure occurs through breathing contaminated air, contact with dust, and skin absorption. National surveys in the United States and Europe report that most adults and children have detectable levels of these metabolites [

1,

2]. Concentrations are higher in people working or living in recently sprayed buildings, especially where ventilation is poor or carpets trap dust [

3,

6,

7].

Workers in pest control, cleaning, and building maintenance jobs often have the highest levels. Their urine samples show repeated low-dose exposure far above background levels [

2,

3,

33].

However, very few studies have tracked workers over time, and there are no clear reference values defining what levels are safe or harmful. This lack of long-term monitoring or exposure limits highlights a major gap in protecting indoor workers [

33,

34].

6.2. Nervous System Effects

People with long-term exposure to pyrethroids often report headaches, dizziness, fatigue, or slower thinking [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

16]. Several studies link higher 3-PBA levels with poorer results on attention and coordination tests [

16,

17,

19].

These effects are believed to result from oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage in nerve cells, which cause gradual loss of energy and nerve signaling problems [

10,

11,

12,

27]. Such changes fit the pattern seen in animal studies and explain the chronic fatigue and concentration problems reported by many exposed workers.

6.3. Thyroid and Hormonal Effects

Research from Asia and Europe shows that pyrethroid exposure can disturb thyroid hormone balance [

13,

14,

15]. Workers and residents exposed to these chemicals often have changes in blood levels of T3, T4, and TSH, suggesting that the thyroid is under stress [

13,

14,

15,

31]. Laboratory studies show that the metabolite 3-PBA can attach to transthyretin, a protein that normally carries thyroid hormones in the blood, possibly reducing hormone availability [

31]. Despite this evidence, there are still no official limits for long-term exposure or guidance on safe spraying intervals [

33,

34].

6.4. Liver and Metabolic Effects

In people who work with pyrethroids over many years, liver enzymes such as ALT, AST, and GGT are often higher than normal [

11,

25]. This pattern indicates mild but ongoing liver stress, even without acute poisoning.

Laboratory studies support this, showing that repeated low-dose exposure can trigger oxidative stress and enzyme induction in liver tissue [

11,

12]. These findings are consistent with chronic exposure in indoor workplaces.

6.5. Heart and Circulation

A long-term U.S. population study found that adults with higher urinary pyrethroid levels had a greater risk of heart disease and early death [

33].

Other studies suggest that chronic exposure may damage the inner lining of blood vessels, affect heart-rate control, and increase inflammation [

16,

33]. Such effects point to broader systemic toxicity that current short-term safety guidelines fail to consider [

33,

34].

6.6. Immune and Irritation Symptoms

People working in heavily sprayed or poorly ventilated buildings often report tiredness, throat and eye irritation, cough, or allergy-like reactions [

19,

20].

These complaints are consistent with studies showing that pyrethroids can activate inflammatory and immune pathways, raising levels of cytokines and oxidative markers [

10,

11,

27].This ongoing low-grade inflammation may explain

Sick Building Syndrome–type symptoms reported in chronically exposed workers. Despite these clues, immune and inflammatory effects are rarely included in workplace health monitoring.

Summary

Human studies clearly show that many people are exposed to pyrethroids indoors, including workers who spray or clean regularly. Repeated low-dose exposure has been linked to changes in the nervous system, thyroid, liver, heart, and immune function. Yet, there are no long-term studies or safety standards that define how often indoor spraying can be done safely or what levels of pyrethroid residues are acceptable. Closing this gap will require combined environmental and health monitoring, better ventilation management, and stronger occupational-health guidelines for enclosed workplaces.

7. Occupational Risk Management and Medical Surveillance Agenda

7.1. Concept and Purpose

Occupational exposure to pyrethroids in enclosed, air-conditioned workplaces represents an under-recognized chronic health risk. Although most safety frameworks address only acute toxicity and short-term re-entry precautions, repeated indoor spraying creates a

continuous low-dose exposure cycle that is not captured by current regulations [

33,

34]. This section proposes a structured agenda for

risk management and medical surveillance, designed to prevent chronic toxicity and support early detection of exposure-related health effects.

7.2. Exposure Control and Prevention Strategies

Effective control begins with

accurate exposure documentation and

operational discipline. Each spraying event should be recorded, including product identity, active ingredient, concentration, and treated zones. Ventilation and HVAC systems require active management—shutdown during application and controlled restart only after sufficient air exchange [

19,

26]. Whenever possible,

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) should replace routine calendar-based spraying with

pest-threshold–based justification to minimize unnecessary chemical use [

3,

6,

7].

Post-application cleaning using

HEPA-filtered vacuuming is essential in carpeted buildings to reduce dust-reservoir residues. Regular surface or dust sampling can be used to verify the effectiveness of these control measures and provide real exposure data for occupational-health teams [

33,

34].

7.3. Worker Health Protection and Surveillance

Chronic indoor exposure to pyrethroids may affect several biological systems, including the liver, thyroid, nervous system, cardiovascular, and immune functions [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

25,

27,

31,

33]. Therefore, worker health programs should combine routine medical screening, symptom-based evaluation, and targeted follow-up.

Annual medical assessments should include a structured symptom questionnaire covering fatigue, dizziness, headaches, eye or throat irritation, skin changes, and other exposure-related complaints. The physical examination should record vital signs, blood pressure, and body mass index. Laboratory testing should focus on affordable and reliable markers of early biological stress. These include liver function tests (ALT, AST, and GGT) to detect hepatic enzyme induction [

11,

25], thyroid function tests (TSH and free T4) to identify endocrine disruption [

13,

14,

15,

31], and a metabolic profile (fasting glucose, HbA1c, and lipid panel) to assess oxidative or metabolic stress [

27]. Renal and hematologic parameters such as serum creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and complete blood count should also be evaluated to monitor general health status [

34].

These core investigations can be conducted annually as part of standard occupational health screening and provide early indicators of organ stress even when direct exposure data are unavailable. When workers present with respiratory, cardiovascular, or neurological complaints, additional investigations should be arranged, such as spirometry for persistent cough or dyspnea, electrocardiography for palpitations or hypertension, and neurological evaluation if peripheral neuropathy or cognitive changes are suspected.

Urinary metabolite analysis, such as testing for 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA) or DCCA, may be considered in special situations, including unexplained clinical findings or research audits. However, these analyses are expensive and not routinely feasible in most occupational health programs; they should therefore complement rather than replace regular clinical assessments [

1,

2,

3,

34].

Vulnerable employees, including those with asthma, dermatologic disorders, thyroid disease, pregnancy, or autoimmune conditions, require individualized exposure-reduction plans. Adjustments may include relocation to low-exposure areas, enhanced personal protective equipment, or modified work duties. Follow-up medical evaluations should be documented and integrated with environmental and maintenance records to enable coordinated risk management.

This comprehensive surveillance approach links occupational hygiene, ventilation control, environmental monitoring, and medical evaluation within a single preventive system, promoting early detection of exposure-related effects and reducing the likelihood of chronic health impairment among indoor workers.

7.4. Implementation Framework

To support consistent application,

Table 2 presents a

structured occupational checklist integrating exposure documentation, operational controls, environmental monitoring, and medical surveillance. It is intended as a practical template for workplaces where pyrethroids are used regularly and formal safety standards are lacking. This checklist translates the exposome concept into routine occupational practice, linking record-keeping, ventilation management, and worker health monitoring in one framework.

Summary

This agenda provides an actionable framework to reduce risk and improve oversight in indoor spraying environments. It establishes a clear connection between environmental management, occupational hygiene, and medical surveillance—areas currently treated separately. By implementing the procedures outlined in

Table 1, organizations can begin to

bridge the regulatory gap in chronic indoor pyrethroid safety and protect workers from long-term health consequences.

8. Discussion and Recommendations

8.1. Interpretation of Findings

The evidence summarized in this review demonstrates that chronic, low-level exposure to pyrethroids is a realistic risk in enclosed occupational environments. These exposures occur not from single spray events, but through residue persistence, dust binding, and repeated resuspension within heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems [

3,

6,

7,

26]. The hydrophobic and lipophilic properties of modern pyrethroids—such as lambda-cyhalothrin—allow residues to accumulate in carpets, fabrics, and settled dust, creating continuous background exposure for workers [

3,

6,

7,

26].

Experimental and epidemiological data consistently indicate that long-term exposure may cause subtle but cumulative toxicity across multiple systems, including the nervous, hepatic, endocrine, cardiovascular, and immune systems [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

25,

27,

31,

33,

34]. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and endocrine disruption emerge as shared biological pathways that link environmental exposure to measurable health changes. These mechanisms provide coherence between the mechanistic evidence from experimental studies and the clinical findings in human biomonitoring data.

Despite the mounting evidence, current risk assessment frameworks remain limited to

acute toxicity and

short-term re-entry precautions. They fail to account for cumulative exposure dynamics in buildings with central HVAC systems and wall-to-wall carpeting—conditions that sustain persistent residue reservoirs. This oversight leaves workers without clear guidance on safe spraying frequency, ventilation duration, or health-monitoring intervals [

33,

34].

Although most available evidence supports the link between persistent indoor pyrethroid residues and multisystem biological stress, several field investigations have reported minimal health effects at typical indoor concentrations when adequate ventilation and application protocols are maintained. These variations suggest that real-world risk depends strongly on compound formulation, ventilation efficiency, and spraying frequency, underscoring the need for longitudinal, exposure-controlled studies.

8.2. Strengths and Practical Implications

This review integrates mechanistic toxicology, exposure science, and occupational medicine into a unified conceptual framework. It highlights the need to reframe indoor pesticide safety as a chronic exposure issue rather than a short-term hazard. By combining environmental controls, medical surveillance, and policy recommendations, the proposed agenda offers an evidence-based foundation for workplace safety programs.

The inclusion of the

occupational checklist (

Table 1) provides a structured model for documentation, exposure prevention, and health monitoring. This tool can guide facilities that perform routine indoor spraying by defining realistic measures such as record-keeping, ventilation management, symptom tracking, and laboratory screening. Importantly, the suggested clinical tests—liver enzymes, thyroid function, and metabolic panels—are feasible in most occupational health settings and can detect early biological changes before clinical illness occurs [

11,

13,

14,

15,

25,

31].

8.3. Research and Policy Priorities

Future research should focus on quantifying

residue decay and resuspension rates under different building conditions to define evidence-based intervals for safe re-entry and re-spraying. Studies linking

dust concentration measurements with

biological biomarkers over time are urgently needed to clarify cumulative dose–response relationships [

1,

2,

3,

33]. There is also a need for

prospective cohort studies among indoor workers to track chronic health outcomes and identify early indicators of thyroid, liver, or cardiovascular dysfunction.

From a regulatory perspective, occupational health agencies should incorporate chronic exposure parameters into pesticide safety standards. This includes establishing threshold guidance for dust or surface residue levels, mandating HVAC maintenance schedules in treated buildings, and developing medical surveillance protocols consistent with those outlined in this review. Routine reporting of spraying frequency, formulation, and exposure conditions should become a standard component of workplace safety documentation.

8.4. Limitations

The available evidence is limited by the heterogeneity of study designs, the scarcity of longitudinal occupational cohorts, and the inconsistent reporting of environmental concentrations. Most biomonitoring data represent single time points and cannot capture cumulative exposure accurately. In addition, much of the mechanistic evidence derives from animal or in vitro models, which, while informative, require confirmation in human studies under real-world exposure conditions. Nevertheless, the convergence of biological and epidemiological evidence supports the plausibility of multisystem effects from chronic low-dose exposure.

8.5. Summary of Key Findings

Chronic exposure to pyrethroids in enclosed workplaces is a neglected occupational health issue. The persistence of residues in dust and carpets, combined with recirculated air and repeated spraying, creates an environment of continuous low-dose exposure. The absence of long-term exposure standards or surveillance protocols leaves workers vulnerable to preventable health risks.

By adopting integrated control measures—ventilation management, exposure documentation, annual medical screening, and worker education—organizations can begin to address this gap. Regulatory bodies should prioritize the development of evidence-based indoor pesticide safety standards that reflect real-world occupational conditions. Recognizing and managing the occupational indoor pyrethroid exposome is essential for preventing chronic health effects and ensuring safe indoor environments for all workers.

9. Conclusions

Indoor occupational use of pyrethroid insecticides demands recognition as a chronic exposure hazard rather than a transient spraying event. Evidence across experimental, environmental, and human studies shows consistent links between low-dose, long-term exposure and multisystem biological stress.

Applying the occupational indoor pyrethroid exposome framework can help bridge the current regulatory gap by integrating environmental management with medical surveillance.

Future policies should establish residue-based safety limits, enforce proper ventilation and maintenance practices, and promote longitudinal monitoring of worker health. Protecting employees in enclosed, treated workplaces will require coordinated action between occupational-health professionals, industrial hygienists, and regulators.

Future research integrating environmental residue monitoring with human biomonitoring and mechanistic biomarkers will be essential to refine exposure thresholds and guide sustainable regulatory reforms.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3-PBA |

3-Phenoxybenzoic Acid |

| ALT |

Alanine Aminotransferase |

| AST |

Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| CBC |

Complete Blood Count |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular Disease |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| EDCs |

Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals |

| EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency |

| eGFR |

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| GC/MS |

Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| GGT |

Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase |

| HbA1c |

Glycated Hemoglobin |

| HELIX |

Human Early-Life Exposome Project |

| HPT Axis |

Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Thyroid Axis |

| HVAC |

Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| IgE |

Immunoglobulin E |

| IPM |

Integrated Pest Management |

| MSDS |

Material Safety Data Sheet |

| NHANES |

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| PBK |

Physiologically Based Kinetic |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SBS |

Sick Building Syndrome |

| SDS |

Safety Data Sheet |

| T3 |

Triiodothyronine |

| T4 |

Thyroxine |

| TSH |

Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone |

| VOC |

Volatile Organic Compound |

References

- Barr DB, Allen R, Olsson AO, Bravo R, Caltabiano LM, Montesano A, et al. Concentrations of selective metabolites of organophosphorus pesticides in the United States population. Environ Res. 2005;99(3):314–326. [CrossRef]

- Bradman A, Whitaker D, Quirós L, Castorina R, Henn BC, Nishioka M, et al. Pesticides and their metabolites in the homes and urine of farmworker children living in the Salinas Valley, CA. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2007;17(4):331–349. [CrossRef]

- Colt JS, Lubin J, Camann D, Davis S, Cerhan J, Severson RK, et al. Comparison of pesticide levels in carpet dust and self-reported pest treatment practices in four US sites. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2004;14(1):74–83. [CrossRef]

- Heudorf U, Butte W, Schulz C, Angerer J. Reference values for metabolites of pyrethroid and organophosphorus insecticides in urine for human biomonitoring in environmental medicine. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2004;207(3):293–299. [CrossRef]

- Tulve NS, Jones PA, Nishioka MG, Fortmann RC, Croghan CW, Zhou JY, et al. Pesticide measurements from the first national environmental health survey of child care centers using a multi-residue GC/MS analysis method. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40(20):6269–6274. [CrossRef]

- Lewis RG, Fortune CR, Willis RD, Camann DE, Antley JT. Distribution of pesticides and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in house dust. Environ Sci Technol. 1999;33(12):2106–2112. [CrossRef]

- Rudel RA, Camann DE, Spengler JD, Korn LR, Brody JG. Phthalates, alkylphenols, pesticides, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and other endocrine-disrupting compounds in indoor air and dust. Environ Sci Technol. 2003;37(20):4543–4553. [CrossRef]

- Ray DE, Fry JR. A reassessment of the neurotoxicity of pyrethroid insecticides. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111(1):174–193. [CrossRef]

- Soderlund DM. Molecular mechanisms of pyrethroid insecticide neurotoxicity: recent advances. Arch Toxicol. 2012;86(2):165–181. [CrossRef]

- Nasuti C, Gabbianelli R, Falcioni G, Di Stefano A, Sozio P, Cantalamessa F. Dopaminergic system modulation, behavioral changes, and oxidative stress after neonatal administration of pyrethroids. Toxicol Sci. 2007;99(1):328–337. [CrossRef]

- El-Demerdash FM. Oxidative stress and hepatotoxicity induced by synthetic pyrethroids in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49(5):1146–1153. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Dai Y, He Y, Li J, Li Y, He Q. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage induced by cyhalothrin in rat brain. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;245(1):1–8. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Zhang Y, Tang Z, Li Y, Zhang H. Endocrine disruption effects of pyrethroid insecticides on thyroid hormone homeostasis: a review. Environ Int. 2018;121(Pt 1):73–82. [CrossRef]

- Kim S, Park J, Kim HJ, Lee JJ, Choi G, Choi S, et al. Association between urinary pyrethroid metabolites and thyroid hormone levels in general adult population. Environ Res. 2019;172:354–361. [CrossRef]

- Meeker JD, Ferguson KK. Relationship between urinary phthalate and bisphenol A concentrations and serum thyroid measures in U.S. adults and adolescents. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(10):1396–1402. [CrossRef]

- Park J, Kim S, Lee JJ, Kim HJ, Choi G, Kim S, et al. Exposure to pyrethroid insecticides and cardiovascular disease risk: a population-based study. Sci Total Environ. 2020;703:135537. [CrossRef]

- Grandjean P, Landrigan PJ. Neurobehavioural effects of developmental toxicity. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(3):330–338. [CrossRef]

- Slotkin TA. Does early-life exposure to organophosphate insecticides lead to prediabetes and obesity? Reprod Toxicol. 2011;31(3):297–301. [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola MS, Yang L, Ieromnimon A, Jaakkola JJK. Office work exposures and respiratory and sick building syndrome symptoms. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64(3):178–184. [CrossRef]

- Mendell MJ, Mirer AG, Cheung K, Tong M, Douwes J. Respiratory and allergic health effects of dampness, mold, and dampness-related agents: a review. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(6):748–756. [CrossRef]

- Jones RR, Barone-Adesi F, Koutros S, Lerro CC, Blair A, Lubin J, et al. Incidence of solid tumors among pesticide applicators exposed to permethrin. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(4):451–460. [CrossRef]

- Mustieles V, Fernández MF. Environmental exposures and the human exposome. Environ Int. 2020;134:105244. [CrossRef]

- Wild CP. Complementing the genome with an “exposome”: the outstanding challenge of environmental exposure measurement in molecular epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(8):1847–1850. [CrossRef]

- Vrijheid M, Slama R, Robinson O, Chatzi L, Coen M, van den Hazel P, et al. The human early-life exposome (HELIX): project rationale and design. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(6):535–544. [CrossRef]

- Li AJ, Pal VK, Kannan K. A review of environmental occurrence, toxicity, and human exposure to organophosphate esters. Sci Total Environ. 2018;616–617:103–114. [CrossRef]

- Weschler CJ. Changes in indoor pollutants since the 1950s. Atmos Environ. 2009;43(1):153–169. [CrossRef]

- Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Rignell-Hydbom A, Coumoul X, Courtin F, Johansson H, Rüegg J, et al. Endocrine disruptors and human health: review of evidence and perspectives. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(9):686–696. [CrossRef]

- Guxens M, Ballester F, Espada M, Fernández MF, Grimalt JO, Ibarluzea J, et al. Prenatal exposure to organochlorine compounds and neuropsychological development up to 4 years of age. Environ Int. 2012;45:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Peters A, Frohlich M, Döring A, Immervoll T, Wichmann HE, Hutchinson WL, et al. Particulate air pollution is associated with an acute phase response in men. Circulation. 2001;103(23):2810–2815. [CrossRef]

- Bellinger DC. Environmental chemical exposures and neurodevelopmental impairments in children. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2247–2258. [CrossRef]

- Normann SS, Ma Y, Andersen HR, Valente MJ, Renko K, Arnold S, Skovsager Andersen M, Vinggaard AM. Pyrethroid Exposure Biomarker 3-Phenoxybenzoic Acid (3-PBA) Binds to Transthyretin and Is Positively Associated with Free T3 in Pregnant Women. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2024;14:114495. [CrossRef]

- Purece A, Thomsen ST, Plass D, Spyropoulou A, Machera K, Palmont P, Crépet A, Benchrih R, Devleesschauwer B, Wieland N, Scheepers P, Deepika D, Kumar V, Sanchez G, Bessems J, Piselli D, Buekers J. A preliminary estimate of the environmental burden of disease associated with exposure to pyrethroid insecticides and ADHD in Europe based on human biomonitoring. Environ Health. 2024;23(1):91. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh NH, Kwok ESC. Biomonitoring-based risk assessment of pyrethroid exposure in the U.S. population: application of high-throughput and physiologically based kinetic models. Toxics. 2025;13(3):216. [CrossRef]

- Bao W, Liu B, Simonsen DW, Lehmler H-J. Association Between Exposure to Pyrethroid Insecticides and Risk of All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality in the U.S. Adult Population. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(3):367–374. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).