1. Introduction

Severe symptomatic aortic stenosis is common in ageing populations and, if left untreated, carries a poor prognosis, yet many patients have been denied surgical aortic valve replacement because of prohibitive operative risk [

1,

2,

3]. The advent of transcatheter aortic valve implantation has provided a less invasive alternative for these individuals, initially restricted to inoperable or high-risk candidates with advanced age and severe functional limitation at presentation [

4,

5]. Over the last decade, expanding evidence and guideline updates have broadened TAVI indications, leading to earlier referral and a more heterogeneous case mix with regard to clinical risk, comorbidities, and anatomical complexity [

6].

In contemporary practice, patients undergoing TAVI show evolving risk profiles, with stable age yet a shift from high-risk and inoperable subjects toward more intermediate-risk candidates such as those in New York Heart Association class II or even I [

7]. Concurrently, comorbidity profiles have shifted, with rising prevalences of traditional cardiovascular risk factors and coronary artery disease, together with lower rates of peripheral disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and improved renal function [

8]. Parallel changes are evident on imaging, with reductions in aortic valve area and mean gradient, altered patterns of aortic and mitral regurgitation, increased prevalence of severe calcification, and fluctuations in left ventricular systolic function [

9,

10].

Procedurally, the program has consolidated a streamlined transfemoral access strategy under local anesthesia, with reductions in fluoroscopy exposure, contrast volume, and procedural duration, while maintaining high device and procedural success across all eras [

11]. At the same time, early clinical outcomes have evolved, with shorter hospital stays, reduced major adverse events and major bleeding, despite temporal fluctuations in stroke rates and a stable need for permanent pacemaker implantation [

12]. Echocardiographic follow-up at one month demonstrates low post-procedural gradients and reduced more-than-mild residual aortic regurgitation, aligning our long-term institutional experience with contemporary reports of optimized hemodynamic performance after transcatheter valve implantation [

13]. Against this background, the present study examines the evolution of TAVI over twelve years in a single high-volume center, relating changes in baseline and imaging characteristics to procedural features and early post-procedural outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a single-center, retrospective, observational cohort study conducted at the Cardiovascular Interventional Unit of Pineta Grande Hospital, a high-volume TAVI center in Southern Italy, stemming from an established ongoing multicenter prospective cohort study [

14,

15]. All consecutive adult patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation for severe symptomatic aortic stenosis over a 12-year period (2012–2024) were included. For the purposes of the present analysis, the overall cohort was stratified a priori into three temporal eras (2012–2015, 2016–2020, and 2021–2024) to reflect major changes in indications, patient selection, and procedural practice. Patients were identified from a prospectively maintained institutional database and complemented, when necessary, by review of electronic medical records. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and local regulations on observational research. The protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee, which waived the requirement for individual informed consent in view of the retrospective nature and use of anonymized data.

Baseline clinical evaluation included demographic characteristics, anthropometric data, cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities, prior cardiac and vascular procedures, current medications, and functional status. Dyspnea and heart failure symptoms were graded according to New York Heart Association (NYHA) class at the time of the preprocedural Heart Team discussion. Surgical risk was estimated using EuroSCORE II in all patients; Logistic EuroSCORE was also recorded in earlier years, in line with contemporary practice, and was later used for exploratory prognostic analyses. Chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral artery disease and other comorbidities were assessed according to prevailing international guideline definitions. Estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated using standard formulae. All clinical, laboratory, and risk-score data were collected before the index procedure and recorded in the institutional database.

All patients underwent comprehensive transthoracic echocardiography before TAVI to quantify aortic stenosis severity, aortic and mitral regurgitation, left ventricular systolic function, and other structural abnormalities. Aortic valve area was calculated using the continuity equation, and mean transvalvular gradient was derived from Doppler recordings. Preprocedural coronary angiography was systematically performed to assess the presence and extent of coronary artery disease, and percutaneous coronary intervention was undertaken at the discretion of the Heart Team according to the severity and distribution of lesions. Multidetector computed tomography was increasingly used over time to evaluate aortic root anatomy, valve morphology (including bicuspid valves), vascular access, and calcification burden. The indication for TAVI, access route, and device type were decided by a multidisciplinary Heart Team comprising interventional cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, imaging cardiologists, and anesthesiologists.

Procedures were performed in a dedicated hybrid operating room by experienced interventional cardiologists, with cardiac surgeons and anesthesiologists readily available. Transfemoral access under local anesthesia and mild sedation was the default strategy across all eras, with alternative axillary access reserved for patients with unsuitable iliofemoral anatomy. Vascular access was obtained percutaneously, typically under fluoroscopic and/or ultrasound guidance, with closure achieved using contemporary suture-based or plug-based devices according to operator preference and device evolution. Self-expanding transcatheter valves were predominantly used throughout the study, with balloon-expandable valves adopted in selected cases in later years. Procedural details, including access site, valve type and size, need for post-dilation, fluoroscopy time, contrast volume, and total procedural duration, were recorded prospectively.

Clinical and echocardiographic follow-up was planned at 30 days (or the closest available time point within 1 month) in all patients. The primary outcome measure for the present analysis was the occurrence of major adverse events within 1 month, defined as a composite of all-cause death, stroke, myocardial infarction, major vascular complications, or major bleeding. Individual components of the composite, as well as other periprocedural complications (including renal replacement therapy, cardiac tamponade, annular rupture, valve migration, surgical conversion, and new permanent pacemaker implantation), were assessed according to contemporary Valve Academic Research Consortium criteria where applicable [

16]. Early post-procedural echocardiography was used to measure peak and mean aortic valve gradients and to grade residual aortic regurgitation.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as counts and percentages. Baseline, imaging, procedural, and outcome characteristics were compared across the three temporal eras using one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate, for categorical variables. A multivariable logistic regression model was constructed to identify independent predictors of 1-month major adverse events, initially including clinically relevant covariates and variables associated with outcomes at univariable analysis; a stepwise approach was then used to derive a parsimonious model [

17]. The discriminative ability of selected variables for predicting major adverse events was assessed using receiver-operating characteristic curves and calculation of the corresponding area under the curve with 95% confidence intervals. All tests were two-sided, and a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Over the 12-year study period, the demographic profile of TAVI recipients remained broadly similar in terms of age (mean ~81 years across periods) and sex distribution (female ~60–65%), whereas cardiovascular risk factors became progressively more prevalent. From 2012–2015 to 2021–2024, there was a marked increase in dyslipidemia (46.4% vs 89.9%), hypertension (90.9% vs 97.7%), smoking history (1.1% vs 11.2%), family history of coronary artery disease, and known coronary artery disease (p for all <0.001) (

Table 1). Diabetes patterns shifted with a rise in non–insulin-dependent diabetes (p=0.005), while baseline peripheral artery disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease became less frequent in later years (both p<0.01). Functional status improved substantially, with NYHA class III–IV decreasing from 78.2% to 18.0% and class II increasing from 21.7% to 78.9% (p<0.001). Consistent with evolving indications, surgical risk scores declined over time (EuroSCORE II from 5.7±5.1 to 3.2±3.6, p<0.001), with a relative increase in intermediate-risk patients and a reduction in inoperable cases, although high-risk patients remained the majority.

Echocardiographic and angiographic characteristics also evolved across eras (

Table 2). Aortic valve area became slightly smaller and mean transvalvular gradient lower in the most recent period (0.63±0.13 cm

2 and 47.0±15.8 mmHg in 2021–2024 vs 0.69±0.18 cm

2 and 58.2±15.3 mmHg in 2012–2015; both p<0.001), consistent with a broader spectrum of hemodynamic presentations. The prevalence of significant coronary artery disease on coronary angiography increased significantly over time (p<0.001), and bicuspid valve anatomy, while still infrequent, was more commonly treated in the most recent era (p=0.020). Mitral and aortic regurgitation profiles shifted, with a higher proportion of moderate mitral regurgitation and moderate aortic regurgitation in later years (both p<0.001). Procedurally, transfemoral access under local anesthesia remained the dominant strategy throughout, while alternative axillary access was introduced in the last period (

Table 3). Over time, procedural efficiency improved, with significant reductions in fluoroscopy time (from 23.8±6.9 to 16.1±9.6 minutes), contrast volume (from 125.5±39.1 to 74.0±28.9 mL), and overall procedural time (p≤0.003 for all). Residual aortic regurgitation after TAVI decreased substantially, with none/trace regurgitation increasing from 57.8% to 91.3% and ≥moderate regurgitation becoming rare (p<0.001), while device and procedural success remained consistently high (>99% in all periods).

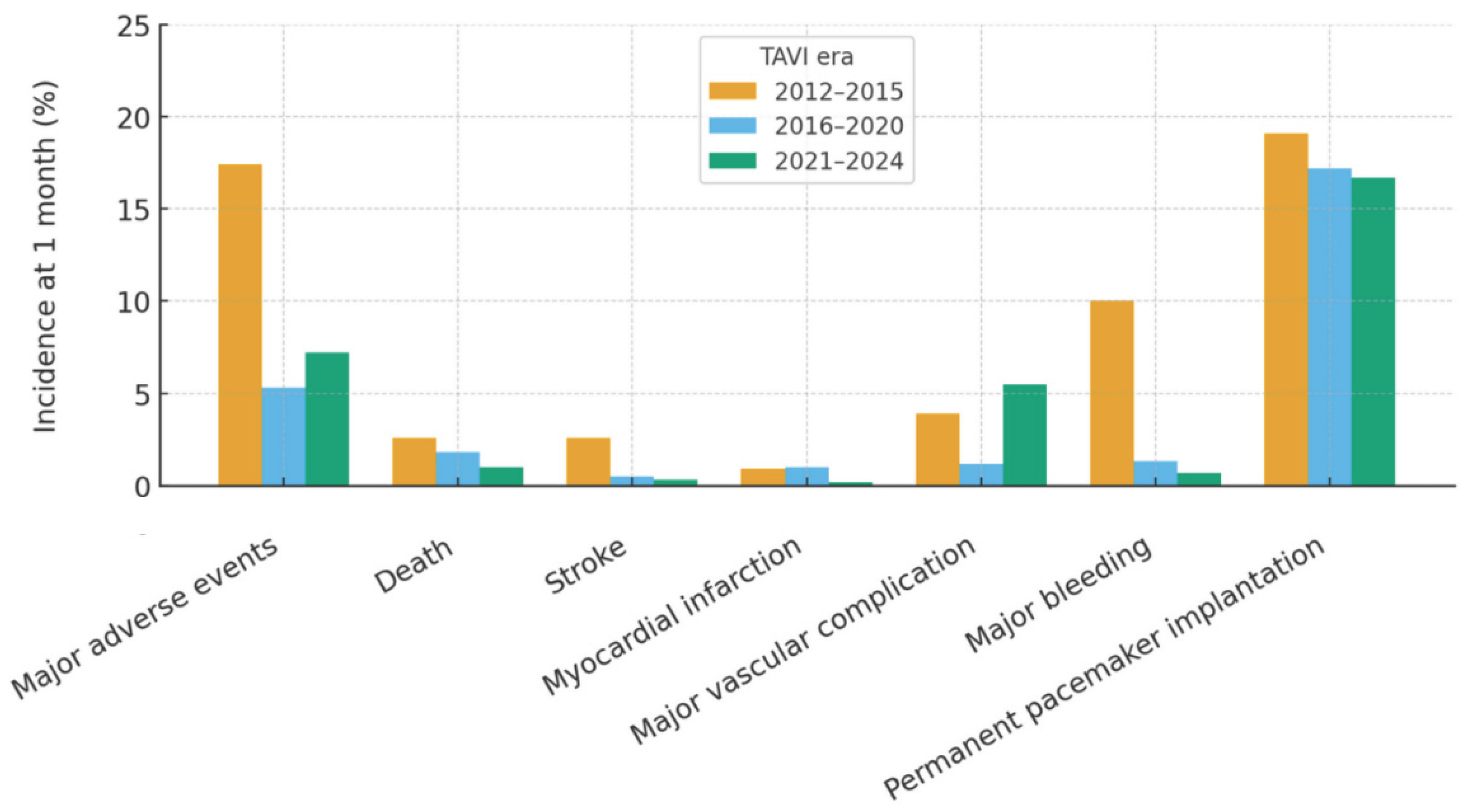

Early clinical outcomes up to 1 month reflected these improvements in case selection and procedural performance (

Table 4;

Figure 1). Total length of hospital stay shortened significantly from 7.3±2.8 to 6.1±3.1 days (p<0.001). The composite rate of major adverse events (death, stroke, myocardial infarction, major vascular complication, or major bleeding) declined markedly from 17.4% in 2012–2015 to 5.3% in 2016–2020 and 7.2% in 2021–2024 (p<0.001), driven in particular by a steep reduction in major bleeding (10.0% to 0.7%, p<0.001) and stroke (2.6% to 0.3%, p=0.002). Major vascular complications varied over time, with a nadir in the intermediate period and a higher rate in the most recent era (p=0.003). Early mortality remained low and numerically decreased (2.6% to 1.0%, p=0.087). Need for new permanent pacemaker implantation was frequent but stable across periods (approximately 17–19%, p=0.645). Hemodynamic results at 1 month were consistently favorable, with low post-procedural gradients and only minor temporal variation in peak and mean gradients and in the distribution of residual aortic regurgitation.

At multivariable logistic regression, Logistic EuroSCORE emerged as the only independent predictor of 1-month major adverse events. Higher Logistic EuroSCORE values were associated with a progressive increase in the odds of experiencing (1.023 [1.006-1.041] per unit change, p=0.008), while age, sex, renal function, diabetes, COPD, and other clinical variables did not retain independent significance after adjustment. Discrimination analysis showed however that, although statistically associated with outcomes, Logistic EuroSCORE had only modest ability to distinguish patients with and without events in this cohort, with an area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve of 0.59 (0.54-0.64), only slightly better than chance and clearly below usual thresholds for good discrimination.

4. Discussion

The present study provides a comprehensive overview of how a mature TAVI program has evolved over more than a decade in a single high-volume center. The main findings can be summarized as follows: (a) despite stable age and sex distribution, the clinical profile of TAVI recipients has shifted towards patients with more conventional cardiovascular risk factors but lower global surgical risk; (b) imaging and anatomical characteristics have broadened, with increasing treatment of patients with significant coronary artery disease, bicuspid valves, and more complex valvular regurgitation patterns; (c) procedural performance has been streamlined, with shorter procedures, less fluoroscopy and contrast use, and a marked reduction in residual aortic regurgitation; and (d) early outcomes have improved over time, with shorter hospital stay and a substantial decline in major bleeding and stroke, while overall mortality has remained low and the need for permanent pacemaker implantation has been stable.

The temporal changes in baseline characteristics observed in our cohort reflect the transition of TAVI from a “last resort” therapy for inoperable or extreme-risk patients to a standard option for a broader spectrum of high- and intermediate-risk individuals [

2,

3,

18]. Whereas mean age and female prevalence remained remarkably constant, we observed a progressive increase in dyslipidemia, hypertension, smoking, and documented coronary artery disease, together with improved renal function and a decline in peripheral artery disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [

19]. Functional status at presentation also improved dramatically, with most contemporary patients in NYHA class II rather than class III–IV, and EuroSCORE II values decreased accordingly [

20]. These findings support the notion that earlier referral, more proactive screening, and guideline-driven expansion of indications have shifted TAVI towards patients with a more “typical” cardiovascular risk profile but less advanced symptomatic and systemic disease.

Our echocardiographic and angiographic data corroborate this evolution towards a more heterogeneous and anatomically complex TAVI population. Over time, the aortic valve area became slightly smaller while mean transvalvular gradients decreased, suggesting a broader inclusion of patients with low-flow or low-gradient severe aortic stenosis as well as mixed valvular disease. The prevalence of angiographically significant coronary artery disease increased markedly, and bicuspid valves, virtually absent in the early years, were increasingly treated in the most recent era. Concomitant valve disease also changed, with higher rates of moderate mitral and aortic regurgitation. Together, these findings indicate that the Heart Team progressively embraced patients with more complex anatomical substrates and competing hemodynamic burdens, in line with contemporary emphasis on individualized, anatomy-driven decision-making rather than a narrow focus on isolated, high-gradient aortic stenosis [

21,

22].

From a procedural standpoint, our data highlight the consolidation of a streamlined, predominantly transfemoral TAVI strategy under local anesthesia, with selective adoption of alternative axillary access in patients with unsuitable iliofemoral anatomy. Across eras, device and procedural success remained consistently >99%, yet fluoroscopy time, contrast volume, and overall procedural duration decreased significantly, reflecting both operator experience and technological refinement. Perhaps most striking is the marked reduction in residual aortic regurgitation, with the proportion of patients leaving the catheterization laboratory with none or trace aortic regurgitation increasing and ≥moderate regurgitation becoming exceedingly rare. Although our analysis was not designed to dissect the relative contributions of device design, implantation technique, and imaging guidance, the observed improvements mirror those reported in contemporary series of newer-generation valves and attest to the incremental impact of a mature program on procedural quality [

23].

These procedural gains translated into tangible clinical benefits, with total length of stay decreasing by more than one day on average over the study period, compatible with progressive adoption of minimalist pathways and earlier mobilization. The composite rate of major adverse events fell from almost one in five patients in the earliest era to less than one in ten in recent years, driven mainly by a dramatic reduction in major bleeding and a parallel decline in stroke. The temporal pattern of major vascular complications was less linear, with a nadir in the intermediate period and higher rates thereafter, possibly reflecting the increased use of alternative access routes and treatment of more complex anatomies. Importantly, early mortality remained low throughout and numerically improved, while the need for new permanent pacemaker implantation remained frequent but stable, underscoring the persistent challenge of conduction disturbances despite overall procedural optimization.

Our multivariable analysis underscores the enduring prognostic relevance of global surgical risk as captured by Logistic EuroSCORE, which emerged as the only independent predictor of 1-month major adverse events. However, the modest discrimination of this score in our cohort, with an area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve barely exceeding 0.5, highlights the limitations of legacy surgical scores when applied to contemporary TAVI populations. These models were derived in surgically treated cohorts and do not incorporate several variables now recognized as crucial in TAVI, including frailty, cognitive status, detailed anatomical features, and procedural complexity [

24]. Our findings therefore support ongoing efforts to refine and recalibrate TAVI-specific risk scores and to complement numerical risk estimation with structured geriatric and anatomical assessment [

25].

Several clinical implications arise from this experience. First, the observed stability of age together with improved functional class and lower surgical risk suggests that TAVI has not simply “aged down” to younger patients, but rather expanded towards individuals with less advanced symptomatic heart failure and better global reserve, without abandoning complex or high-risk cases [

26]. Second, the combination of increasing coronary and valvular complexity with improved hemodynamic and clinical outcomes reinforces the value of a dedicated Heart Team and of consistent institutional expertise in case selection, procedural planning, and post-procedural care [

27]. Third, the persistent incidence of conduction disturbances and major vascular complications, even in the context of otherwise favorable results, reminds clinicians that there remains room for further improvement, particularly in access planning, closure strategies, and conduction-sparing implantation techniques [

28,

29].

This study has important strengths, including the large sample size, the long observation period spanning three distinct eras of TAVI practice, the inclusion of all consecutive patients treated in a high-volume center, and the systematic collection of detailed clinical, imaging, and outcome data. Nonetheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. The retrospective, single-center design limits generalizability and leaves room for unmeasured confounding and secular trends in referral patterns, device availability, and post-procedural care that cannot be fully adjusted for [

30]. Follow-up was restricted to 1 month and did not capture mid- or long-term outcomes, including valve durability, rehospitalization, or structural valve deterioration. We did not perform granular analyses according to valve type, access strategy, or specific anatomical subsets, nor did we systematically assess frailty, quality of life, or patient-reported outcomes. Finally, the study was not powered to detect differences in individual rare events across eras.

5. Conclusions

Over 12 years of continuous activity, our high-volume TAVI program has witnessed a profound evolution in case mix, procedural practice, and early outcomes. Patients currently referred for TAVI present with more conventional cardiovascular risk factors, more extensive coronary and valvular disease, and lower surgical risk, yet they benefit from shorter procedures, less radiation and contrast exposure, improved hemodynamic results, and fewer major early complications. These data support the safety and effectiveness of an integrated Heart Team approach to TAVI across the risk spectrum and emphasize the need for ongoing refinement of risk stratification tools and procedural strategies to further optimize outcomes in an increasingly complex and heterogeneous patient population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.C., A. G.; methodology, N.C., G.B.Z., A.G.; validation, S.G., P.F., A.M., M.C., M.A., R.A., M.P.; formal analysis, G.B.Z.; investigation, N.C., G.B.Z., A.G.; resources, N.C., G.B.Z., A.G.; data curation, S.G., P.F., A.M., M.C., M.A., R.A., M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, N.C., G.B.Z., A.G.; writing—review and editing, S.G., P.F., A.M., M.C., M.A., R.A., M.P.; visualization, G.B.Z.; supervision, N.C., A. G.; project administration, A.G.; funding acquisition, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of I.R.C.C.S Ospedale Galeazzi-Sant’Ambrogio (protocol code NCT02713932 and date 1 July 2010).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to patient confidentiality issues.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was drafted and illustrated with the assistance of artificial intelligence tools, such as ChatGPT 5 (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA), Mage (Mage, New York, NY, USA), in keeping with established best practices (Biondi-Zoccai G. ChatGPT for Medical Research. Torino: Edizioni Minerva Medica; 2024). The final content, including all conclusions and opinions, has been thoroughly revised, edited, and approved by the authors. The authors take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the work and retain full credit for all intellectual contributions. Compliance with ethical standards and guidelines for the use of artificial intelligence in research has been ensured.

Conflicts of Interest

Giuseppe Biondi-Zoccai has consulted, lectured and/or served as advisory board member and/or expert witness for Abiomed, Advanced Nanotherapies, Amarin, AstraZeneca, Balmed, Cardionovum, Cepton, Crannmedical, Endocore Lab, Eukon, Guidotti, Innova HTS, Innovheart, Menarini, Microport, Opsens Medical, Otsuka Medical Devices Europe, Recor, Servier, Synthesa, Terumo, and Translumina, outside the present work. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MAE |

Major adverse event |

| NYHA |

New York Heart Association |

| TAVI |

Transcatheter aortic valve intervention |

References

- Osnabrugge, R.L.; Mylotte, D.; Head, S.J.; Van Mieghem, N.M.; Nkomo, V.T.; LeReun, C.M.; Bogers, A.J.; Piazza, N.; Kappetein, A.P. Aortic stenosis in the elderly: disease prevalence and number of candidates for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a meta-analysis and modeling study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013, 62, 1002–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Clinical, Interventional and Surgical Perspectives; Giordano, A., Biondi-Zoccai, G., Frati, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

-

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation; Testa, L., Bedogni, F., Eds.; Edizioni Minerva Medica: Torino, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kapadia, S.R.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Makkar, R.R.; Svensson, L.G.; Agarwal, S.; Kodali, S.; Fontana, G.P.; Webb, J.G.; Mack, M.; Thourani, V.H.; Babaliaros, V.C.; Herrmann, H.C.; Szeto, W.; Pichard, A.D.; Williams, M.R.; Anderson, W.N.; Akin, J.J.; Miller, D.C.; Smith, C.R.; Leon, M.B. Long-term outcomes of inoperable patients with aortic stenosis randomly assigned to transcatheter aortic valve replacement or standard therapy. Circulation 2014, 130, 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.R.; Leon, M.B.; Mack, M.J.; Miller, D.C.; Moses, J.W.; Svensson, L.G.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Webb, J.G.; Fontana, G.P.; Makkar, R.R.; Williams, M.; Dewey, T.; Kapadia, S.; Babaliaros, V.; Thourani, V.H.; Corso, P.; Pichard, A.D.; Bavaria, J.E.; Herrmann, H.C.; Akin, J.J.; Anderson, W.N.; Wang, D.; Pocock, S.J. PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2011, 364, 2187–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praz, F.; Borger, M.A.; Lanz, J.; Marin-Cuartas, M.; Abreu, A.; Adamo, M.; Ajmone Marsan, N.; Barili, F.; Bonaros, N.; Cosyns, B.; De Paulis, R.; Gamra, H.; Jahangiri, M.; Jeppsson, A.; Klautz, R.J.M.; Mores, B.; Pérez-David, E.; Pöss, J.; Prendergast, B.D.; Rocca, B.; Rossello, X.; Suzuki, M.; Thiele, H.; Tribouilloy, C.M.; Wojakowski, W. ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group. 2025 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2025, 46, 4635–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demal, T.J.; Weimann, J.; Ojeda, F.M.; Bhadra, O.D.; Linder, M.; Ludwig, S.; Grundmann, D.; Voigtländer, L.; Waldschmidt, L.; Schirmer, J.; Schofer, N.; Blankenberg, S.; Reichenspurner, H.; Conradi, L.; Seiffert, M.; Schaefer, A. Temporal changes of patient characteristics over 12 years in a single-center transcatheter aortic valve implantation cohort. Clin Res Cardiol 2023, 112, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, M.M.; Joseph, M.; Ezenna, C.; Pereira, V.; Rossi, R.; Akman, Z.; Rubens, M.; Mahadevan, V.S.; Nanna, M.G.; Goldsweig, A.M. TAVR vs. SAVR for severe aortic stenosis in the low and intermediate surgical risk population: An updated meta-analysis, meta-regression, and trial sequential analysis. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2025, 79, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karra, N.; Sharon, A.; Massalha, E.; Fefer, P.; Maor, E.; Guetta, V.; Ben-Zekry, S.; Kuperstein, R.; Matetzky, S.; Beigel, R.; Segev, A.; Barbash, I.M. Temporal trends in patient characteristics and clinical outcomes of TAVR: over a decade of practice. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 5027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landes, U.; Barsheshet, A.; Finkelstein, A.; Guetta, V.; Assali, A.; Halkin, A.; Vaknin-Assa, H.; Segev, A.; Bental, T.; Ben-Shoshan, J.; Barbash, I.M.; Kornowski, R. Temporal trends in transcatheter aortic valve implantation, 2008-2014: patient characteristics, procedural issues, and clinical outcome. Clin Cardiol 2017, 40, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, H.; Kurz, T.; Feistritzer, H.J.; Stachel, G.; Hartung, P.; Lurz, P.; Eitel, I.; Marquetand, C.; Nef, H.; Doerr, O.; Vigelius-Rauch, U.; Lauten, A.; Landmesser, U.; Treskatsch, S.; Abdel-Wahab, M.; Sandri, M.; Holzhey, D.; Borger, M.; Ender, J.; Ince, H.; Öner, A.; Meyer-Saraei, R.; Hambrecht, R.; Fach, A.; Augenstein, T.; Frey, N.; König, I.R.; Vonthein, R.; Rückert, Y.; Funkat, A.K.; Desch, S.; Berggreen, A.E.; Heringlake, M.; de Waha-Thiele, S. SOLVE-TAVI Investigators. General versus local anesthesia with conscious sedation in transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the randomized SOLVE-TAVI trial. Circulation 2020, 142, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, S.V.; Manandhar, P.; Vemulapalli, S.; Vekstein, A.M.; Kosinski, A.S.; Carroll, J.D.; Thourani, V.H.; Mack, M.J.; Cohen, D.J. Mediators of improvement in TAVR outcomes over time: insights from the STS-ACC TVT Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2023, 16, e013080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodali, S.; Thourani, V.H.; White, J.; Malaisrie, S.C.; Lim, S.; Greason, K.L.; Williams, M.; Guerrero, M.; Eisenhauer, A.C.; Kapadia, S.; Kereiakes, D.J.; Herrmann, H.C.; Babaliaros, V.; Szeto, W.Y.; Hahn, R.T.; Pibarot, P.; Weissman, N.J.; Leipsic, J.; Blanke, P.; Whisenant, B.K.; Suri, R.M.; Makkar, R.R.; Ayele, G.M.; Svensson, L.G.; Webb, J.G.; Mack, M.J.; Smith, C.R.; Leon, M.B. Early clinical and echocardiographic outcomes after SAPIEN 3 transcatheter aortic valve replacement in inoperable, high-risk and intermediate-risk patients with aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J 2016, 37, 2252–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, A.; Corcione, N.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Berti, S.; Petronio, A.S.; Pierli, C.; Presbitero, P.; Giudice, P.; Sardella, G.; Bartorelli, A.L.; Bonmassari, R.; Indolfi, C.; Marchese, A.; Brscic, E.; Cremonesi, A.; Testa, L.; Brambilla, N.; Bedogni, F. Patterns and trends of transcatheter aortic valve implantation in Italy: insights from RISPEVA. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2017, 18, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.; Corcione, N.; Ferraro, P.; Bedogni, F.; Testa, L.; Sardella, G.; Mancone, M.; Tomai, F.; De Persio, G.; Iadanza, A.; Frati, G.; Biondi-Zoccai, G. RISPEVA Study Investigators. Outcome of patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation after prior balloon aortic valvuloplasty. J Invasive Cardiol 2018, 30, 380–385. [Google Scholar]

- Généreux, P.; Piazza, N.; Alu, M.C.; Nazif, T.; Hahn, R.T.; Pibarot, P.; Bax, J.J.; Leipsic, J.A.; Blanke, P.; Blackstone, E.H.; Finn, M.T.; Kapadia, S.; Linke, A.; Mack, M.J.; Makkar, R.; Mehran, R.; Popma, J.J.; Reardon, M.; Rodes-Cabau, J.; Van Mieghem, N.M.; Webb, J.G.; Cohen, D.J.; Leon, M.B.; VARC-3 Writing Committee. Valve Academic Research Consortium 3: updated endpoint definitions for aortic valve clinical research. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021, 77, 2717–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi-Zoccai, G. Medical Statistics: A User-Friendly Handbook; Edizioni Minerva Medica: Torino, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Curio, J.; Guthoff, H.; Nienaber, S.; Wienemann, H.; Baldus, S.; Adam, M.; Mauri, V. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation indications and patient selection. Interv Cardiol 2025, 20, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, J.E.; Sindet-Pedersen, C.; Gislason, G.H.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Kragholm, K.H.; Lundahl, C.; Fosbøl, E.L.; Butt, J.H.; Køber, L.; Søndergaard, L.; Olesen, J.B. Temporal trends in utilization of transcatheter aortic valve replacement and patient characteristics: a nationwide study. Am Heart J 2022, 243, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, V.; Abdel-Wahab, M.; Bleiziffer, S.; Veulemans, V.; Sedaghat, A.; Adam, M.; Nickenig, G.; Kelm, M.; Thiele, H.; Baldus, S.; Rudolph, T.K. Temporal trends of TAVI treatment characteristics in high volume centers in Germany 2013-2020. Clin Res Cardiol 2022, 111, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praz, F.; Borger, M.A.; Lanz, J.; Marin-Cuartas, M.; Abreu, A.; Adamo, M.; Ajmone Marsan, N.; Barili, F.; Bonaros, N.; Cosyns, B.; De Paulis, R.; Gamra, H.; Jahangiri, M.; Jeppsson, A.; Klautz, R.J.M.; Mores, B.; Pérez-David, E.; Pöss, J.; Prendergast, B.D.; Rocca, B.; Rossello, X.; Suzuki, M.; Thiele, H.; Tribouilloy, C.M.; Wojakowski, W. ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group. 2025 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2025, 46, 4635–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, C.M.; Nishimura, R.A.; Bonow, R.O.; Carabello, B.A.; Erwin, J.P., 3rd; Gentile, F.; Jneid, H.; Krieger, E.V.; Mack, M.; McLeod, C.; O’Gara, P.T.; Rigolin, V.H.; Sundt, T.M., 3rd; Thompson, A.; Toly, C. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021, 77, 450–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wassef, A.W.A.; Rodes-Cabau, J.; Liu, Y.; Webb, J.G.; Barbanti, M.; Muñoz-García, A.J.; Tamburino, C.; Dager, A.E.; Serra, V.; Amat-Santos, I.J.; Alonso Briales, J.H.; San Roman, A.; Urena, M.; Himbert, D.; Nombela-Franco, L.; Abizaid, A.; de Brito, F.S., Jr.; Ribeiro, H.B.; Ruel, M.; Lima, V.C.; Nietlispach, F.; Cheema, A.N. The learning curve and annual procedure volume standards for optimum outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement: findings from an international registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2018, 11, 1669–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ascenzo, F.; Ballocca, F.; Moretti, C.; Barbanti, M.; Gasparetto, V.; Mennuni, M.; D’Amico, M.; Conrotto, F.; Salizzoni, S.; Omedè, P.; Colaci, C.; Zoccai, G.B.; Lupo, M.; Tarantini, G.; Napodanno, M.; Presbitero, P.; Sheiban, I.; Tamburino, C.; Marra, S.; Gaita, F. Inaccuracy of available surgical risk scores to predict outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2013, 14, 894–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, F.H.; Cohen, D.J.; O’Brien, S.M.; Peterson, E.D.; Mack, M.J.; Shahian, D.M.; Grover, F.L.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Thourani, V.H.; Carroll, J.; Brennan, J.M.; Brindis, R.G.; Rumsfeld, J.; Holmes, D.R., Jr. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for in-hospital mortality after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JAMA Cardiol 2016, 1, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludman, P.F. UK TAVI registry. Heart 2019, 105 Suppl 2, s2–s5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.R.; Chew, D.P.; Horsfall, M.J.; Chuang, A.M.; Sinhal, A.R.; Joseph, M.X.; Baker, R.A.; Bennetts, J.S.; Selvanayagam, J.B.; Lehman, S.J. Multidisciplinary transcatheter aortic valve replacement heart team programme improves mortality in aortic stenosis. Open Heart 2019, 6, e000983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auffret, V.; Puri, R.; Urena, M.; Chamandi, C.; Rodriguez-Gabella, T.; Philippon, F.; Rodés-Cabau, J. Conduction disturbances after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: current status and future perspectives. Circulation 2017, 136, 1049–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagides, V.; Alperi, A.; Mesnier, J.; Philippon, F.; Bernier, M.; Rodes-Cabau, J. Heart failure following transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2021, 19, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biondi-Zoccai, G. Medical Writing: A User-Friendly Handbook; Edizioni Minerva Medica: Torino, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).