Introduction

Substance-use disorders (SUDs) sit near the top of today’s public-health worries. In 2024 almost 50 million Americans aged 12 years or older met diagnostic criteria for an SUD, with alcohol and a range of illicit drugs fuelling both medical and economic damage [

1]. Clinically, the picture is one of compulsive seeking, repeated intoxication and withdrawal, and relentless craving in the face of clear harm [

2]. Family and twin studies put the heritable share of this liability at roughly 50% [

3]. Recent GWAS have started to colour in that genetic landscape, flagging variants in dopaminergic reward genes such as DRD2, enzymes that metabolise alcohol like ADH1B, and pleiotropic loci that cut across several substances [

4,

5].

Yet a large slice of the inherited risk still escapes explanation. One promising lead is neurodevelopment—especially the teenage years, when most SUDs first take hold. Adolescence is the brain’s prime season for synaptic pruning, the activity-guided trimming of excess connections that sharpens neural circuits [

6]. Faulty pruning is already linked to disorders like schizophrenia [

7], but it hasn’t been studied much in the context of addiction. Animal studies suggest it is significant: alcohol exposure can disrupt pruning and maintain reward pathways in a more immature, plastic condition [

8]. Pruning is linked to synaptic plasticity, which is what drugs use to change the brain [

9]. This means that common changes in pruning genes may make people more vulnerable in ways that classic reward or metabolic pathways don’t.

We set out to test that idea using summary statistics from a recent multivariate GWAS of more than one million individuals [

5]. Gene-level associations were computed with MAGMA [

10], heritability was partitioned with stratified LD-score regression [

11], and transcriptome-wide effects were probed with S-PrediXcan [

12]. Analyses centred on curated gene sets covering glutamatergic signalling, three flavours of synaptic pruning (core, extended, and a pruning-only list stripped of glutamatergic overlap), plus negative-control sets. Our aims were to (1) measure the aggregate impact of pruning genes on SUD risk, (2) decide whether that impact is independent of excitatory transmission, and (3) place any new signals in the context of the well-established dopamine and alcohol-metabolism findings. Across all methods, pruning pathways showed significant enrichment, lending weight to a neurodevelopmental view of genetic vulnerability to substance-use disorders.

Methods

MAGMA Analysis

To explore the shared genetic basis of substance use disorder (SUD), we worked with summary statistics from a recent multivariate genome-wide association study that included 1,025,550 adults of European ancestry [

5]. Because that study modeled common liability across several substances, alcohol contributed heavily to the resulting phenotype. We carried out gene-based tests with MAGMA version 1.10, a tool that regresses SNP effects on gene membership while accounting for linkage disequilibrium (LD; [

10]). Single-nucleotide polymorphisms were assigned to genes if they lay within 35 kb upstream or 10 kb downstream of a gene’s annotated boundaries (NCBI Build 37). LD estimates came from the European reference panel of the 1000 Genomes Phase 3 project. After quality control, 18,199 protein-coding genes entered the analysis.

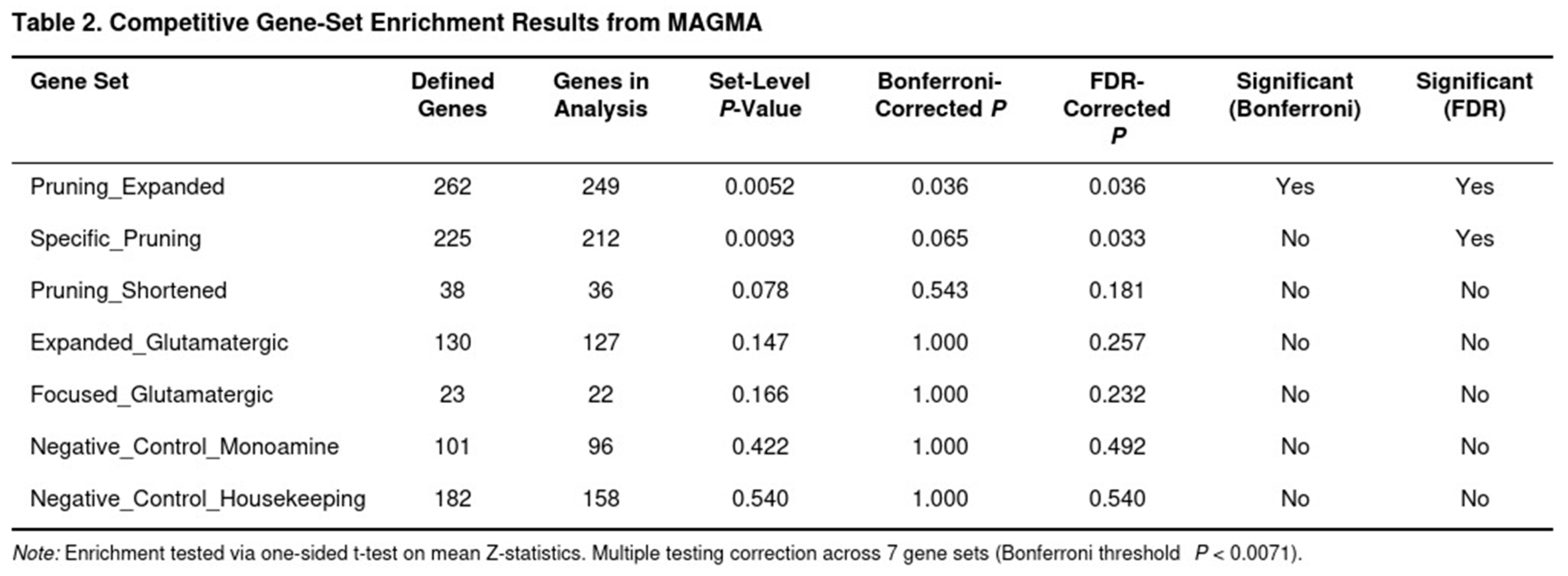

We next asked whether biologically defined collections of genes showed stronger associations with SUD than expected by chance. MAGMA’s competitive test compares the average association of genes in a set with that of all other genes, while adjusting for confounders such as gene length, SNP density, and local LD. Seven prespecified gene sets were evaluated: (1) a focused group of 23 glutamatergic receptor genes; (2) an expanded glutamatergic pathway comprising 130 genes; (3) a concise list of 38 synaptic pruning genes; (4) a broad pruning pathway of 262 genes spanning complement activation, microglial phagocytosis, autophagy, cytoskeletal remodeling, and axon guidance; (5) 101 monoaminergic genes (negative control); (6) 182 housekeeping genes (negative control); and (7) a pruning-specific set of 225 genes created by removing glutamatergic overlaps from the expanded pruning pathway. Significance was determined with one-sided t-tests on mean gene Z-scores. We controlled the family-wise error rate with a Bonferroni threshold of p < 0.0071 (seven tests) and reported false discovery rate (FDR) values as well.

Partitioned Heritability Analysis

We quantified how much of the SNP-based heritability of substance use disorder (SUD) lies in predefined functional categories by applying stratified LD-score regression [

11,

13]. GWAS summary statistics came from a multivariate analysis of 1,025,550 adults of European ancestry [

5]. Variants were converted to the LDSC format, keeping only SNPs with valid alleles and P values. Using 1000 Genomes Phase 3 Europeans as the reference, we computed LD scores and generated annotation files that extended each gene 10 kb upstream and downstream, consistent with the LDSC baseline model.

Seven Biological Annotations Were Examined:

candidate glutamatergic receptor targets (23 genes);

expanded glutamatergic pathway (130 genes);

concise synaptic-pruning list (38 genes);

broad synaptic-pruning pathway (262 genes drawn from complement, microglial phagocytosis, autophagy, cytoskeletal remodeling, and axon-guidance processes);

monoaminergic genes (negative control, 101 genes);

housekeeping genes (negative control, 182 genes);

pruning-specific set (225 genes obtained by removing 37 glutamatergic overlaps from the broad pruning list).

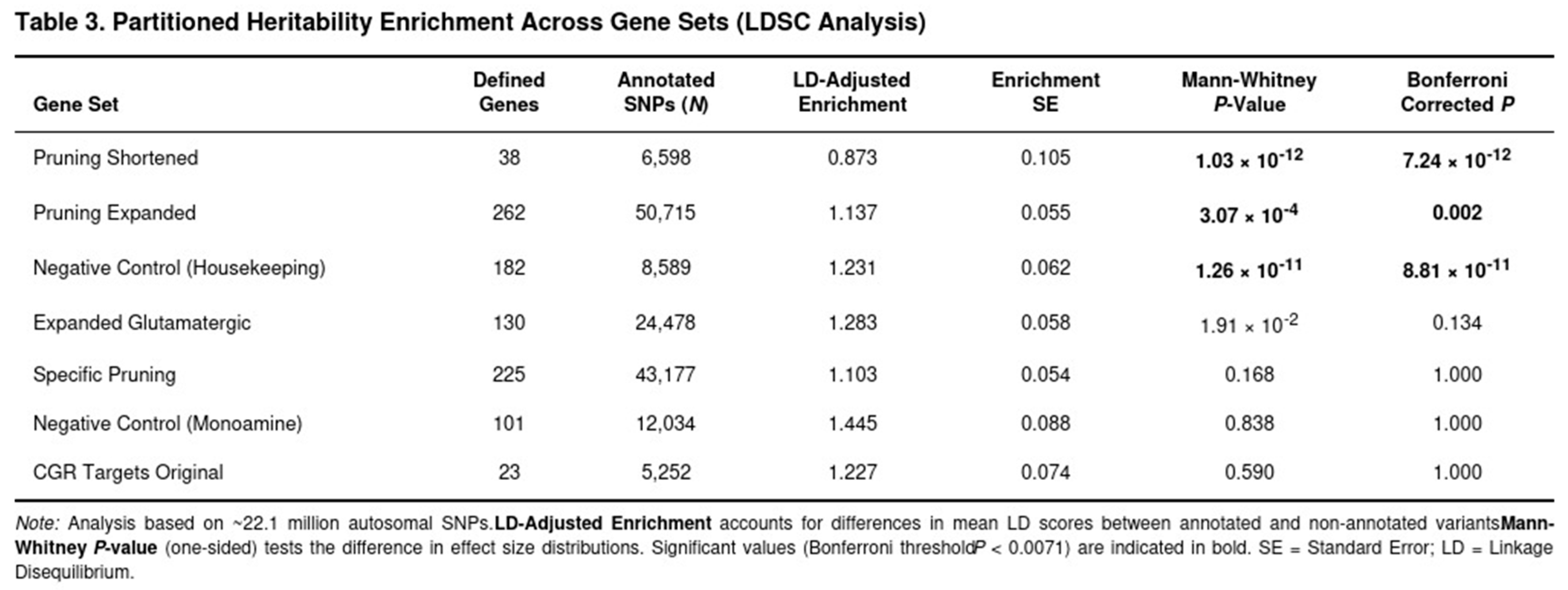

For each annotation we estimated enrichment as the ratio of its share of total heritability to its share of all SNPs, while the stratified model controlled for gene length, SNP density, and local LD. Significance was evaluated with one-tailed tests on stratified χ2 statistics, and Bonferroni correction was applied across the seven annotations (α = 0.0071).

Transcriptome-Wide Association Analysis

Genetically mediated expression in brain tissue was analysed with S-PrediXcan [

12]. GWAS summary data were taken from the multivariate substance-use disorder (SUD) study of 1 025 550 participants of European ancestry [

5] and converted to Z statistics from reported regression coefficients and two-sided P values. Prediction weights were those released with the GTEx v8 MASHR models [

14]. Six regions that participate in reward learning and executive control were examined: frontal cortex (BA9), anterior cingulate cortex (BA24), hippocampus, amygdala, nucleus accumbens and caudate.

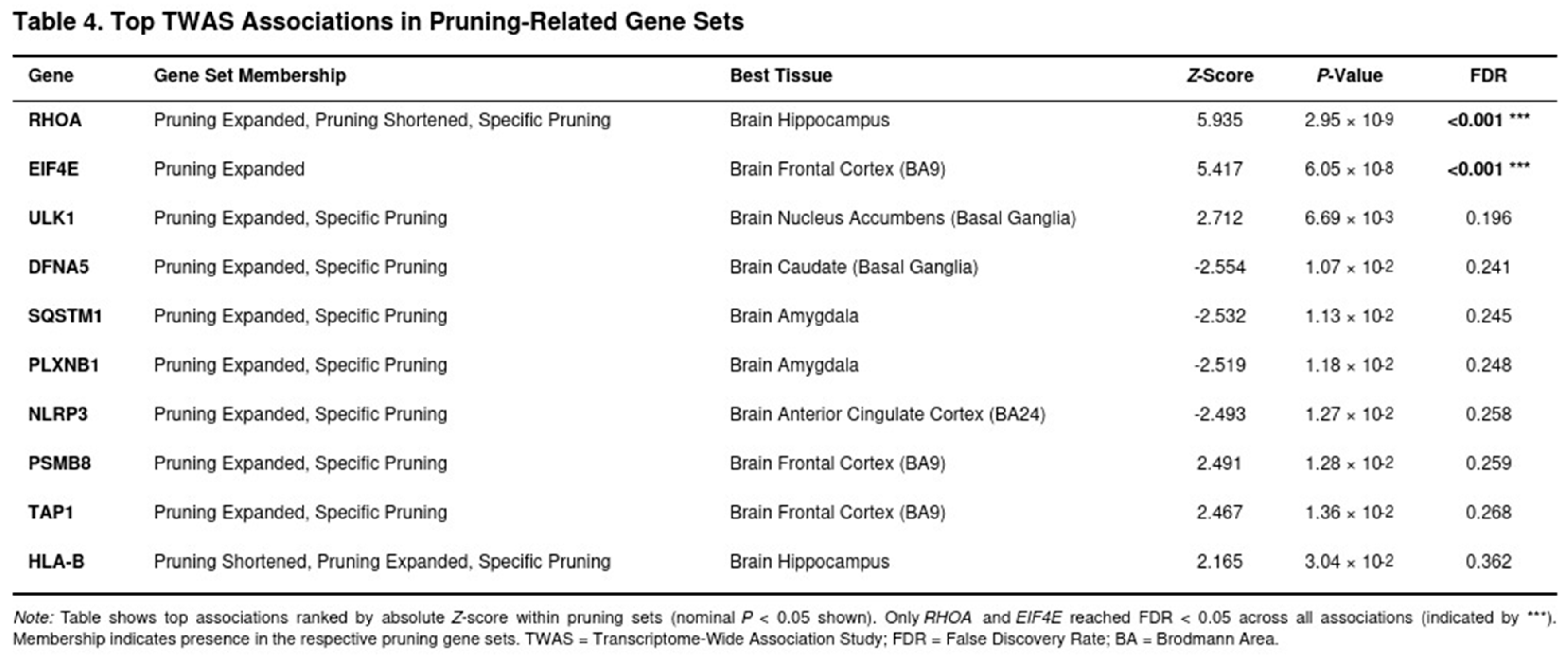

For each tissue a gene-level score was obtained. Within-tissue significance was declared at the Bonferroni threshold, and a study-wide false-discovery rate (FDR) of 0.05 was also applied. Seven biologically motivated gene sets were evaluated—two glutamatergic panels, three synaptic-pruning panels and two negative-control sets (monoaminergic and housekeeping genes). For each set the mean absolute Z score of member genes was compared with that of all other genes by a one-sided Mann–Whitney U test.

Results

MAGMA Analysis

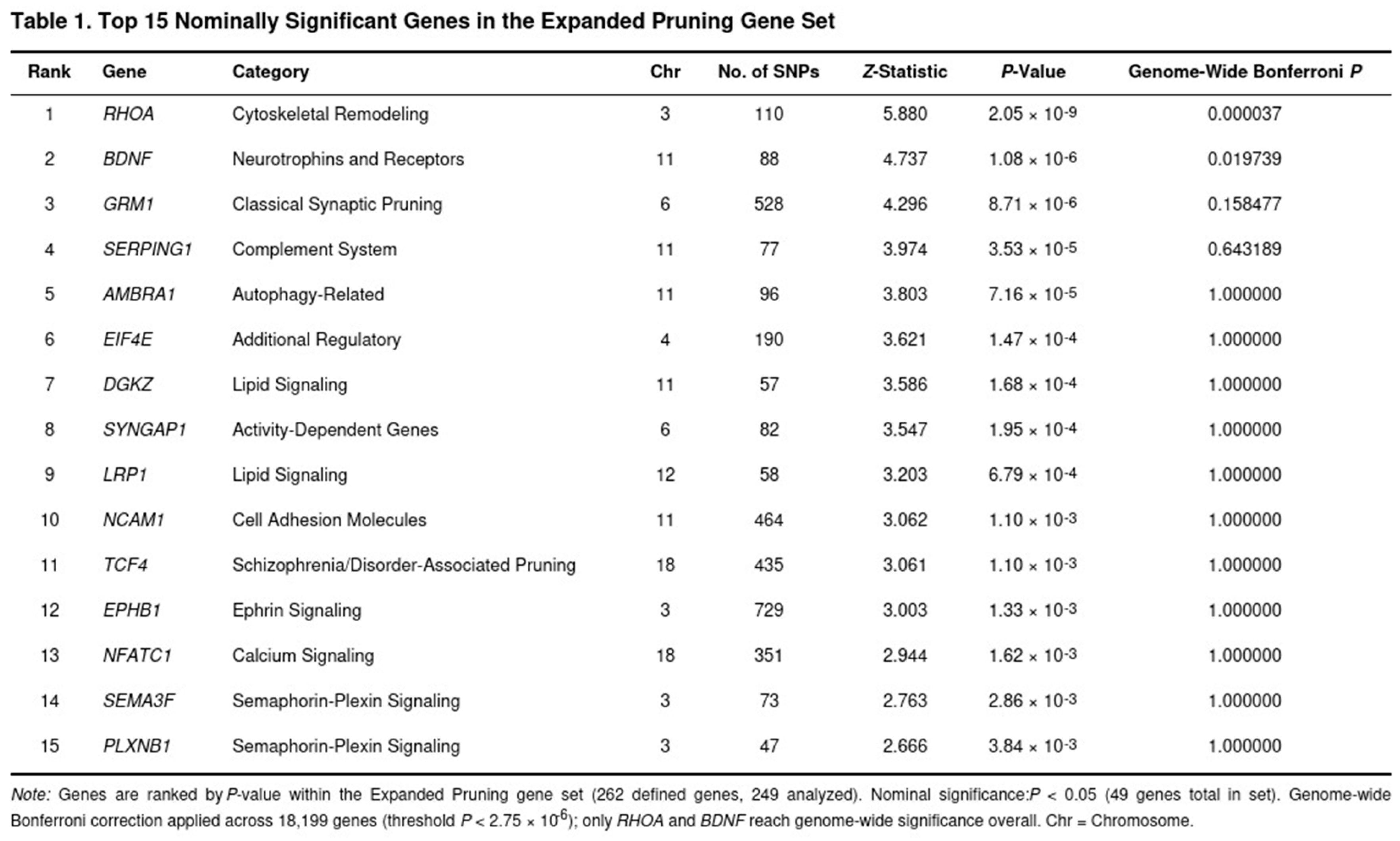

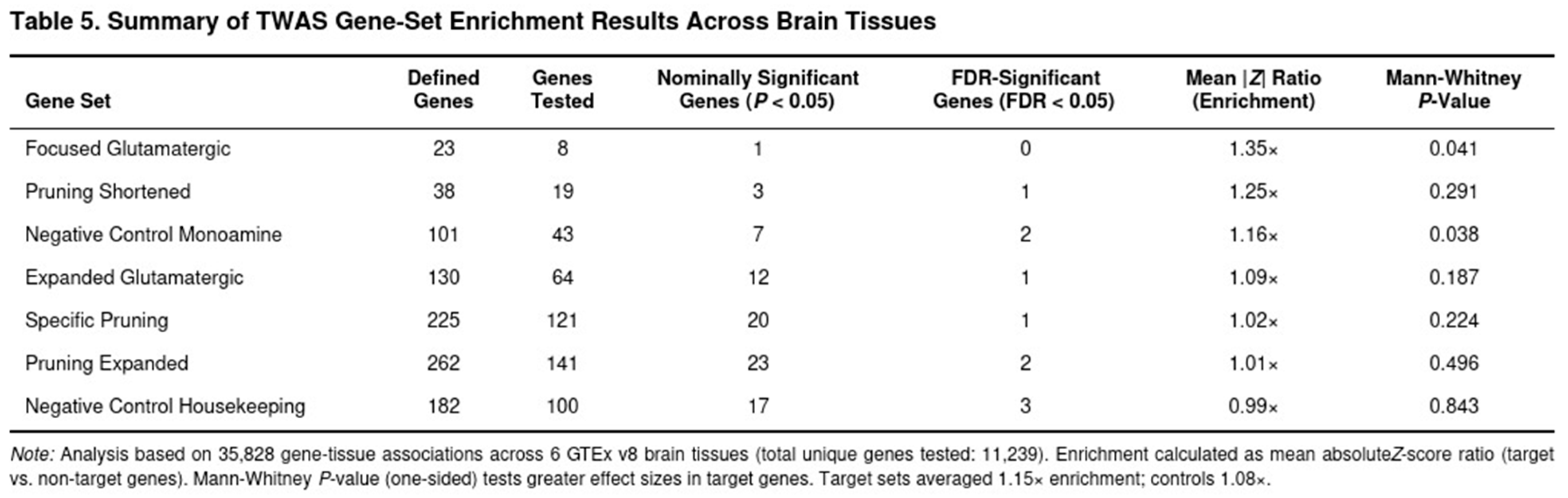

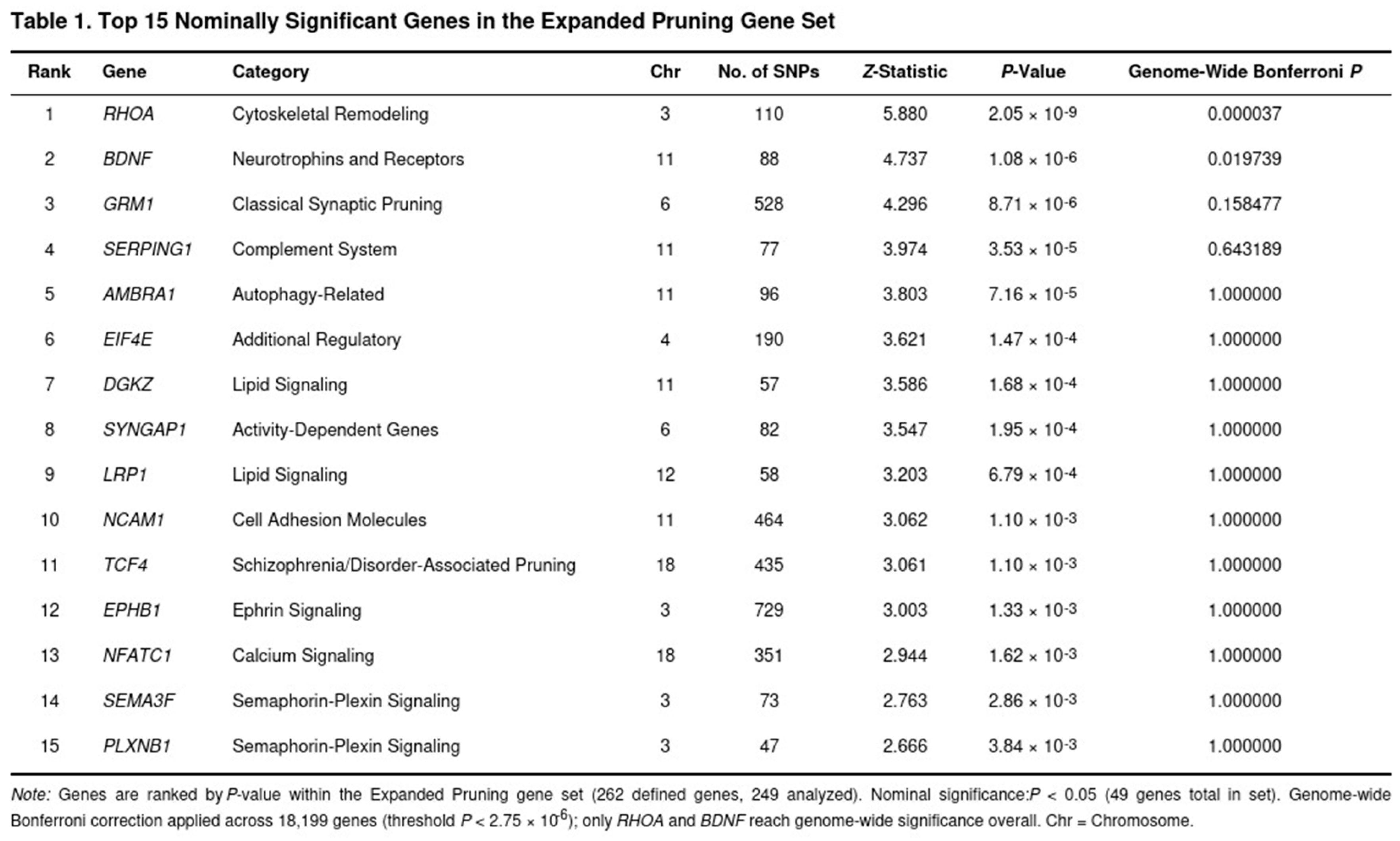

Across the genome, 61 genes surpassed the Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significance (p < 2.75 × 10−6), and 2,839 genes met the nominal cutoff of p < 0.05. Top signals included DRD2 (p = 7.38 × 10−15), FTO (p = 8.29 × 10−14), ADH1C (p = 2.94 × 10−12), PDE4B (p = 9.99 × 10−12), and ADH1B (p = 1.11 × 10−9). Table 1 shows the top genes in the Expanded Pruning Gene Set.

Neither the original nor the expanded glutamatergic gene sets showed evidence of enrichment (p = 0.166 and p = 0.147, respectively) (Table 2). As expected, the monoamine and housekeeping control sets were also non-significant. In contrast, synaptic pruning pathways stood out. The expanded pruning set reached Bonferroni significance (raw p = 0.005; corrected p = 0.036). Key contributors came from cytoskeletal remodeling (RHOA, p = 2.05 × 10−9), complement activation (SERPING1), autophagy (AMBRA1), and axon guidance genes. When glutamatergic overlaps were removed, the pruning-specific set remained significant after FDR adjustment (raw p = 0.009; FDR p = 0.033), indicating that pruning-related processes independently influence SUD risk. The shorter pruning list showed a suggestive trend (p = 0.078) but did not survive multiple-testing correction.

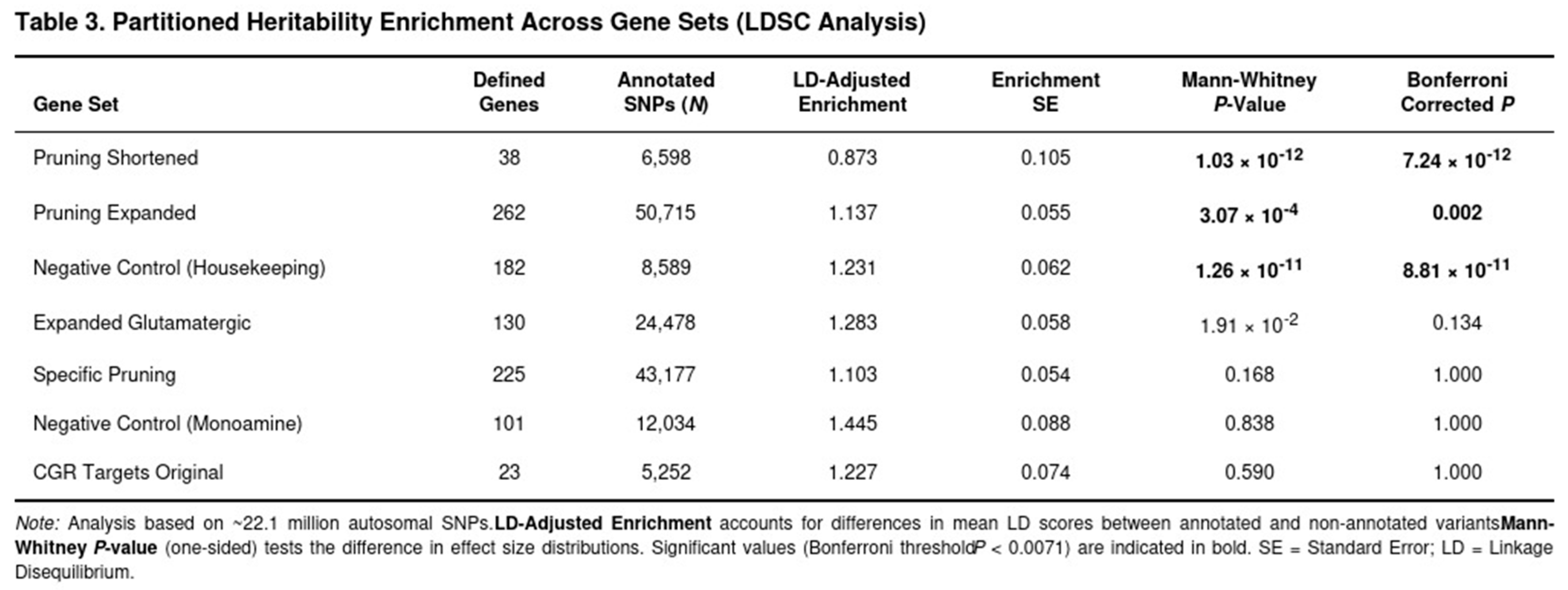

Heritability Partitioning Across Gene Sets

Synaptic-pruning annotations accounted for a disproportionate fraction of SUD heritability (Table 3). The concise pruning set showed the highest enrichment (1.20-fold) and remained significant after correction (Bonferroni-adjusted p = 7.2 × 10−12). The broad pruning pathway was also enriched (raw 1.06-fold; LD-adjusted 1.14-fold; adjusted p = 0.002). The housekeeping control set, unexpectedly, displayed significant enrichment as well (raw 1.16-fold; LD-adjusted 1.23-fold; adjusted p = 8.8 × 10−11), hinting at residual confounding or global functional importance. After removing glutamatergic overlaps, the pruning-specific set did not reach the Bonferroni threshold (LD-adjusted enrichment 1.10-fold; p = 0.168). Glutamatergic pathways showed modest, uncorrected evidence of enrichment (expanded set p = 0.019), whereas the monoaminergic control was null. Overall, pathways related to synaptic pruning captured excess heritability beyond random expectation, aligning with the gene-based associations reported above.

Transcriptome-Wide Association Analysis

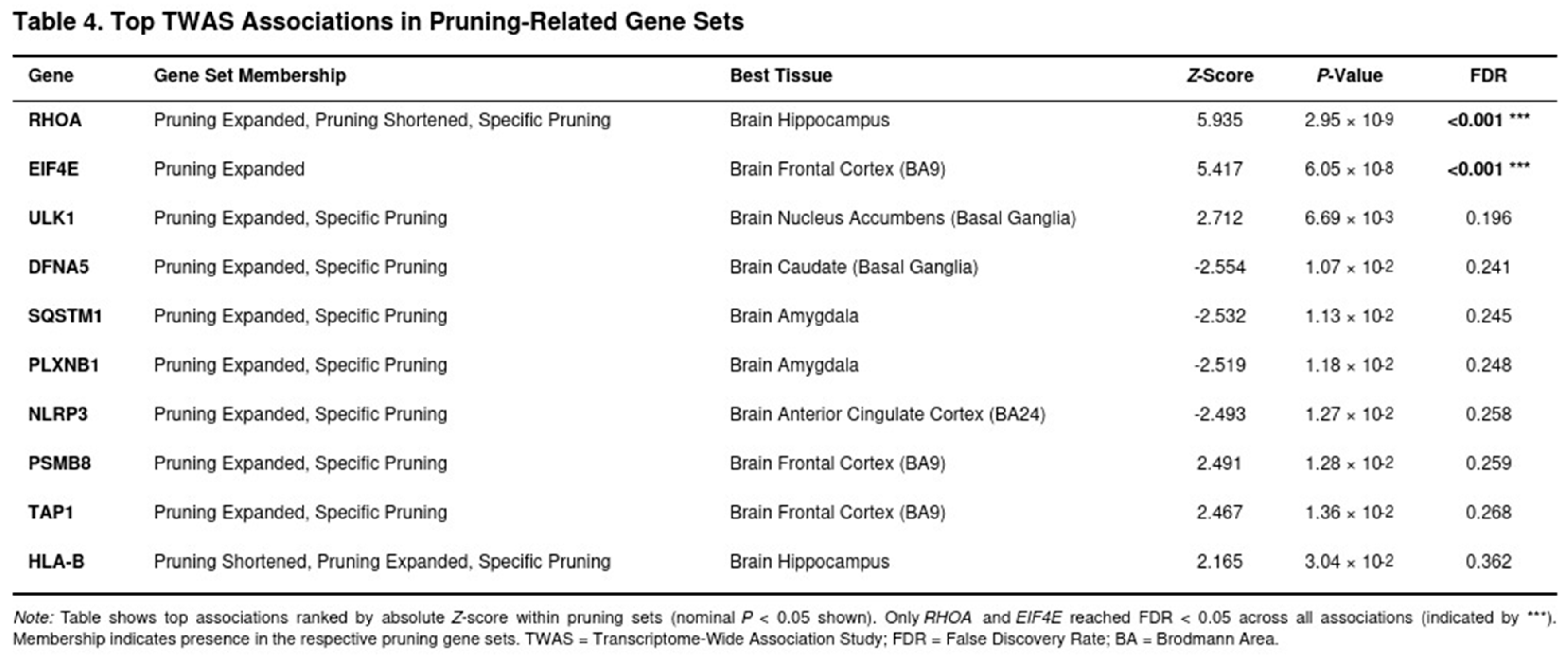

Across the six regions 11 239 distinct genes (35 828 gene–tissue pairs) were tested; 4 119 pairs reached nominal significance (P < 0.05). After FDR correction, robust signals were limited. The clearest hit was RHOA in hippocampus (Z = 5.94, P = 2.9 × 10^-9), in line with its role in cytoskeletal remodelling during synaptic pruning (Table 4). Autophagy (e.g., ULK1) and complement genes produced nominal associations but did not survive multiple testing.

Expression-mediated enrichment for pruning pathways was modest (Table 5). The shortened pruning panel showed the largest, but still non-significant, excess (mean absolute Z = 1.25-fold over background; P = 0.291). Expanded and pruning-specific panels were essentially null (1.01–1.02-fold; P = 0.224–0.496). Glutamatergic panels behaved similarly (expanded panel 1.09-fold; P = 0.187). The monoaminergic control set exhibited weak enrichment (1.16-fold; P = 0.038), whereas the housekeeping set showed none (0.99-fold; P = 0.843). Averaged across all seven panels, target genes displayed a 1.15-fold enrichment compared with 1.08-fold for controls, suggesting that any contribution of adult-brain expression to SUD risk is modest and not robust to stringent correction.

Discussion

Interpretation of Results

Our secondary interrogation of the multivariate substance-use disorder (SUD) genome-wide scan largely recapitulates recognised biology while extending it into less explored territory. First, the strongest gene signals mapped to pathways long linked with addictive behaviour. The dopamine D2 receptor locus (DRD2) and the phosphodiesterase gene PDE4B ranked near the top of the list, a pattern compatible with models in which reduced D2 signalling increases impulsivity and the reinforcing value of drugs [

15]. Equally familiar were the very low P values observed for the alcohol-metabolising genes ADH1B and ADH1C; functional alleles in these loci elicit unpleasant reactions to ethanol and thus lower heavy-drinking risk [

16]. Together, these results confirm that SUD liability reflects both a shared reward substrate and substance-specific physiological mechanisms.

The more novel observation concerns the aggregate behaviour of genes that guide synaptic pruning. Competitive enrichment tests showed that the broad pruning panel—covering complement activation, cytoskeletal remodelling, autophagy, and axon-guidance components—captured a larger fraction of heritability than expected (Bonferroni-adjusted P = 0.036). Within this collection, RHOA, a central regulator of spine dynamics, produced one of the most convincing single-gene statistics. Importantly, the enrichment persisted when glutamatergic overlaps were removed and remained significant at the false-discovery-rate level, indicating that the signal is not driven merely by excitatory transmission genes. By contrast, neither glutamatergic sets nor negative-control panels (monoaminergic, housekeeping) showed comparable inflation.

These findings point to neurodevelopmental refinement of synapses as a plausible, previously under-appreciated, contributor to SUD risk. Synaptic pruning is most active during adolescence—a developmental window that coincides with typical initiation of substance use. Genetic variants that push pruning programmes toward either excessive or insufficient elimination could leave reward circuits in an immature or imbalanced state, heightening vulnerability to compulsive drug seeking [

17]. While causal inferences require functional follow-up, the present results supply a clear roster of pruning genes—headed by RHOA—for experimental prioritisation.

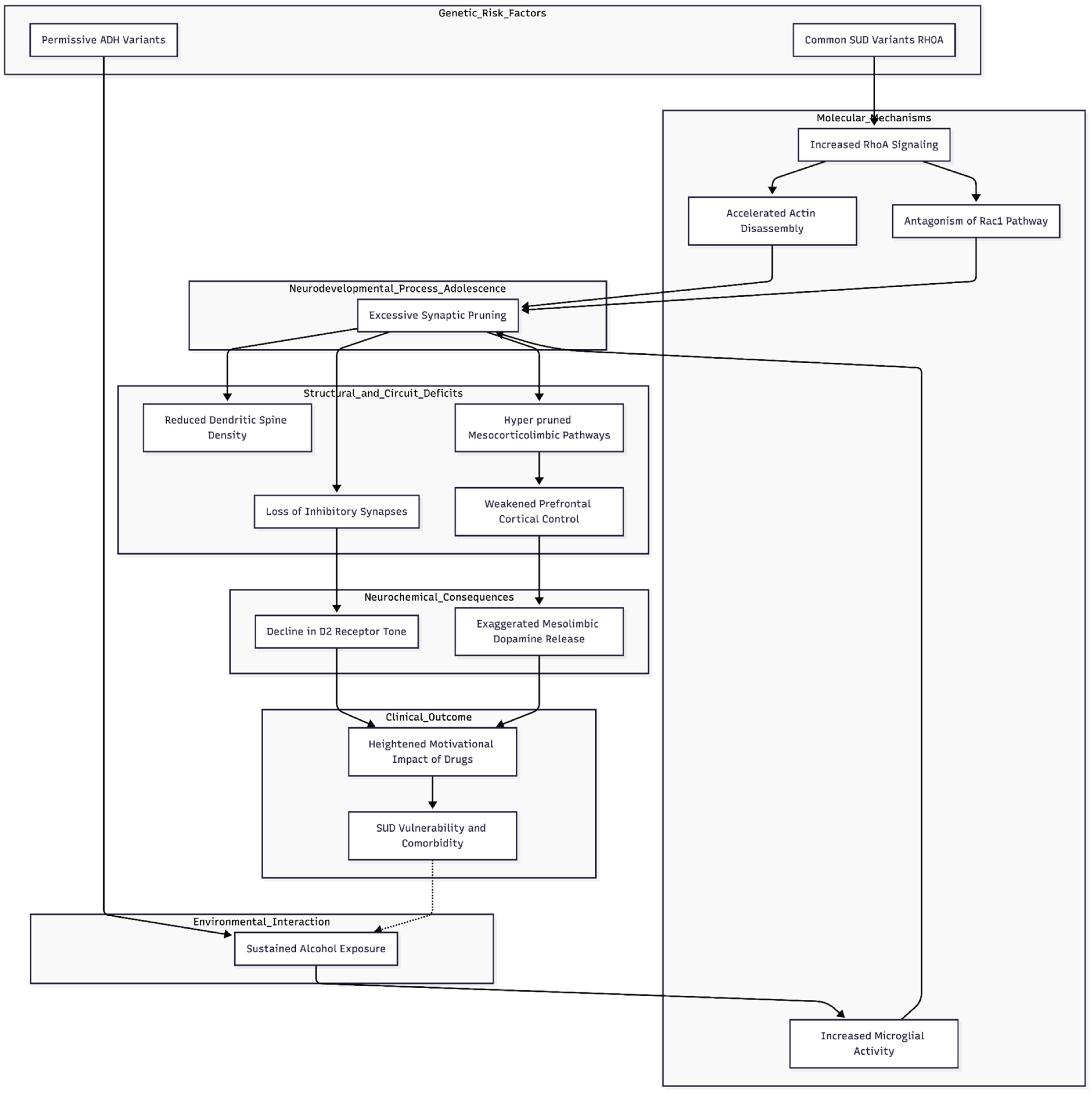

Proposing a Novel Developmental Framework for SUD

Our gene-set results encourage a developmental view of substance-use disorder (SUD). The strongest pruning signal, driven by a positive RHOA Z score of roughly 5.9, indicates that risk alleles are more likely to enhance — rather than blunt — RhoA-dependent cytoskeletal turnover. Because RhoA accelerates actin disassembly, over-activation would be expected to exaggerate physiological synaptic elimination during adolescence, a period when reward and control circuits are still being sculpted. Animal work shows that excessive pruning can destabilise network balance [

8]; our data therefore fit a model in which hyper-pruned mesocorticolimbic pathways provide a fertile ground for addictive behaviours to take hold.

This framework dovetails with dopaminergic theories of addiction. Pruning normally strengthens prefrontal regulation of ventral tegmental area output [

17]. If pruning overshoots, the resulting loss of inhibitory synapses could deepen the well-described decline in D

2-receptor tone [

15], thereby magnifying the motivational impact of drugs. Alcohol-metabolism loci integrate neatly: permissive ADH variants prolong exposure to ethanol, which in turn fuels microglial pruning activity [

8], whereas protective variants interrupt this feed-forward loop [

16]. Nominal hits in plasticity effectors such as mTOR and EIF4E hint that, once pruning has lowered synaptic reserve, drug-induced long-term potentiation may become easier to imprint [

9].

Mechanistic support comes from experimental studies. In the nucleus accumbens, cocaine lowers Rac1 activity; experimental Rac1 loss mimics cocaine by increasing immature spines and potentiating reward responses [

18]. Our finding that RHOA, a Rac1 antagonist, associates with SUD risk suggests a convergent route to the same structural endpoint. Likewise, dorsal-hippocampal knock-down of miR-31-3p increases RhoA protein and dampens methamphetamine place preference, whereas RhoA knock-down has the opposite effect [

19]. These manipulations parallel the directionality implied by our Z-scores and reinforce the idea that heightened RhoA signalling biases individuals toward addiction.

Taken together, we propose that common SUD variants hasten synaptic pruning within developing reward circuitry. This premature loss of connectivity weakens cortical oversight, exaggerates mesolimbic dopamine release and, when coupled with sustained alcohol exposure, propagates further synapse loss. Testable predictions follow: adolescents who carry high-risk genotypes should exhibit lower dendritic-spine density on imaging or post-mortem analysis, and pharmacological or genetic dampening of RhoA-mediated pruning should blunt drug-seeking in preclinical models. By casting SUD as a neurodevelopmental pruning disorder, the model links early onset, comorbidity and long-lasting vulnerability under one mechanistic roof.

Figure 1.

Proposed Neurodevelopmental Pruning Framework for Substance Use Disorder (SUD). The model illustrates how genetic risk variants, particularly in RHOA, drive enhanced cytoskeletal turnover and actin disassembly, precipitating excessive synaptic pruning during critical adolescent circuit refinement. This process is exacerbated by permissive ADH variants that prolong ethanol exposure, thereby fueling microglial-mediated synapse loss. The resulting “hyper-pruned” mesocorticolimbic architecture is characterized by reduced dendritic spine density and weakened prefrontal cortical oversight. These structural deficits destabilize network balance, exacerbate mesolimbic dopamine release, and lower D2-receptor tone, culminating in a heightened physiological vulnerability to addictive behaviors.

Figure 1.

Proposed Neurodevelopmental Pruning Framework for Substance Use Disorder (SUD). The model illustrates how genetic risk variants, particularly in RHOA, drive enhanced cytoskeletal turnover and actin disassembly, precipitating excessive synaptic pruning during critical adolescent circuit refinement. This process is exacerbated by permissive ADH variants that prolong ethanol exposure, thereby fueling microglial-mediated synapse loss. The resulting “hyper-pruned” mesocorticolimbic architecture is characterized by reduced dendritic spine density and weakened prefrontal cortical oversight. These structural deficits destabilize network balance, exacerbate mesolimbic dopamine release, and lower D2-receptor tone, culminating in a heightened physiological vulnerability to addictive behaviors.

Broader Significance of the Pruning Enrichment

Our results give synaptic pruning a prominence in substance-use disorder (SUD) genetics that it has not held before. Previous large-scale association work, including the >1-million-participant meta-analysis that defined the current risk locus landscape [

5], emphasised dopamine signalling, metabolic enzymes and cell-adhesion molecules. None of those studies reported competitive enrichment for pruning pathways. By showing that pruning sets remain significant even after glutamatergic genes are removed, the present re-analysis adds a distinct neurodevelopmental layer to the existing reward-centred narrative.

Developmental Mechanisms and Timing of Risk

Positioning pruning dysregulation upstream of dopaminergic changes helps explain why first heavy use often coincides with adolescence. If variants that up-regulate factors such as RHOA accelerate microglial or cytoskeletal elimination of synapses, inhibitory control over mesolimbic circuits may be trimmed too aggressively. The remaining excitatory bias would heighten the motivational punch of early drug or alcohol exposure, fostering the compulsive patterns captured by the “addiction-rf” factor identified in multivariate GWAS work [

5].

Clinical and Translational Angles

Genes highlighted here overlap with targets already under study in other pruning-related conditions (for example, complement inhibitors being trialled for schizophrenia). That overlap opens the door to prevention efforts aimed at adolescents with high genetic liability, potentially by moderating pruning activity (or encouraging plasticity) during sensitive periods. Furthermore, because pruning genes also feature in cognitive and psychotic disorders, convergent biology may account for the frequent clinical co-occurrence of SUD with those phenotypes.

Limitations and Next Steps

Several caveats temper these conclusions. First, the discovery sample was skewed toward European ancestry and alcohol-related phenotypes; confirmation in more diverse, substance-specific cohorts is essential. Second, transcriptome-wide association produced weaker evidence, suggesting that developmental regulation, rather than steady-state adult expression, mediates the risk. Longitudinal imaging or single-cell studies that track synaptic density from childhood into early use will therefore be critical.

Conclusions

By uncovering robust enrichment of synaptic pruning pathways, our work broadens the genetic framework of SUD from a chiefly reward-centric model to one that also emphasises neurodevelopmental sculpting of the very circuits that drugs ultimately exploit. This shift invites both mechanistic experiments on pruning modulators and preventive trials timed to adolescence, with the prospect of translating genetic insight into earlier and more effective interventions.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. HHS Publication No. PEP25-07-01-001, NSDUH Series H-60; Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2024 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2025.

- Koob, GF; Volkow, ND. Neurobiology of addiction: A neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendler, KS; Aggen, SH; Prescott, CA; et al. Level of family dysfunction and genetic influences on smoking in women. Psychol Med. 2004, 34, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, EC; Demontis, D; Thorgeirsson, TE; et al. A large-scale genome-wide association study meta-analysis of cannabis-use disorder. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 7, 1032–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatoum, AS; Colbert, SMC; Johnson, EC; et al. Multivariate genome-wide association meta-analysis of over 1 million subjects identifies loci underlying multiple substance use disorders. Nat Mental Health 2023, 1, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paus, T; Keshavan, M; Giedd, JN. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008, 9, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellgren, CM; Gracias, J; Watmuff, B; et al. Increased synapse elimination by microglia in schizophrenia patient-derived models of synaptic pruning. Nat Neurosci. 2019, 22, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socodato, R; Henriques, JF; Portugal, CC; et al. Daily alcohol intake triggers aberrant synaptic pruning leading to synapse loss and anxiety-like behavior. Sci Signal. 2020, 13, eaba5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüscher, C; Malenka, RC. Drug-evoked synaptic plasticity in addiction: From molecular changes to circuit remodeling. Neuron 2011, 69, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Leeuw, CA; Mooij, JM; Heskes, T; et al. MAGMA: Generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015, 11, e1004219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finucane, HK; Bulik-Sullivan, B; Gusev, A; et al. Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nat Genet. 2015, 47, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbeira, AN; Dickinson, SP; Bonazzola, R; et al. Exploring the phenotypic consequences of tissue-specific gene expression variation inferred from GWAS summary statistics. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulik-Sullivan, BK; Loh, PR; Finucane, HK; et al. LD score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2015, 47, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GTEx Consortium. The GTEx atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 2020, 369, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkow, ND; Wise, RA; Baler, R. The dopamine motive system: Implications for drug and food addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017, 18, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edenberg, HJ; McClintick, JN. Alcohol dehydrogenases, aldehyde dehydrogenases, and alcohol use disorders: A critical review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2018, 42, 2281–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, CJ; Andersen, SL. Sensitive periods of substance abuse: Early risk for the transition to dependence. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2017, 25, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietz, DM; Sun, H; Lobo, MK; et al. Rac1 is essential in cocaine-induced structural plasticity of nucleus accumbens neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2012, 15, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, H; Shang, Q; Liang, M; et al. MicroRNA-31-3p/RhoA signaling in the dorsal hippocampus modulates methamphetamine-induced conditioned place preference in mice. Psychopharmacology 2021, 238, 3207–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).