Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Due to intensified use of fertilizers and inconsiderable organic matter return, the intensive cropping system is evidently changing soil properties. Even though the changes are hardly predictable spontaneously, it could appear with imbalanced soil mineral nitrogen transformation and decreased biological nitrogen immobilization. To address this uncertainty, we investigated the linkage of soil nitrogen transformation and soil microbial community distribution with the mineral nitrogen fertilization in long-term intensive cropping system during 2019-2022. In this study a three-factor (Factor A: rate of nitrogen (100, 150, 180 and 230 kg N ha−1); Factor B: organic fertilizers (0 and 300 kg ha−1); Factor C: liquid biological activator (0 and 0.1 L ha−1)) experiment carried out on a loam soil (Calcaric Luvisol) in intensive cropping system (in rotation: winter wheat, winter wheat, winter rape and winter wheat). At the study site, soil organic carbon was significantly higher at higher rates of nitrogen application combined jointly with application of organic matter and biological activator. Although the rate of nitrogen fertilization was increasing, either in combination with organic matter or biological activator, induced no significant changes in the accumulation of total nitrogen. Thus, with higher rates of nitrogen fertilization, the content of biologically transformed nitrogen significantly increased. As nitrogen is released from organic matter, it was evident that organic matter inputs affected the biological nitrogen transformation. Organic matter inputs also affected the increase soil fungal community, however, with higher nitrogen inputs soil fungal and bacteria ratio was decreasing. This study highlights the significance of sustainably maintaining of nitrogen and organic matter inputs in intensive cropping systems.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Sampling and Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Soil Chemical Properties

3.2. Soil Biological Properties

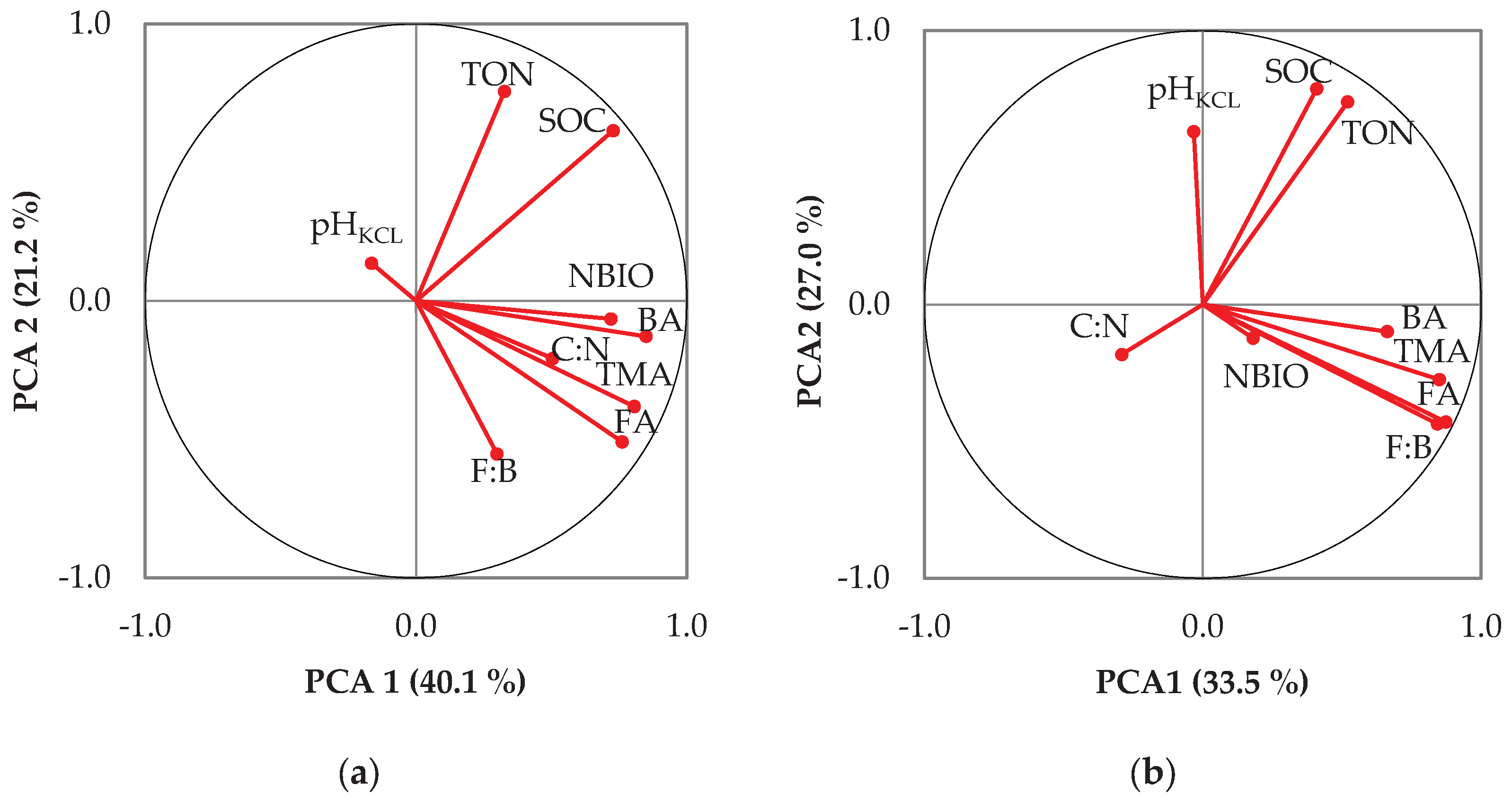

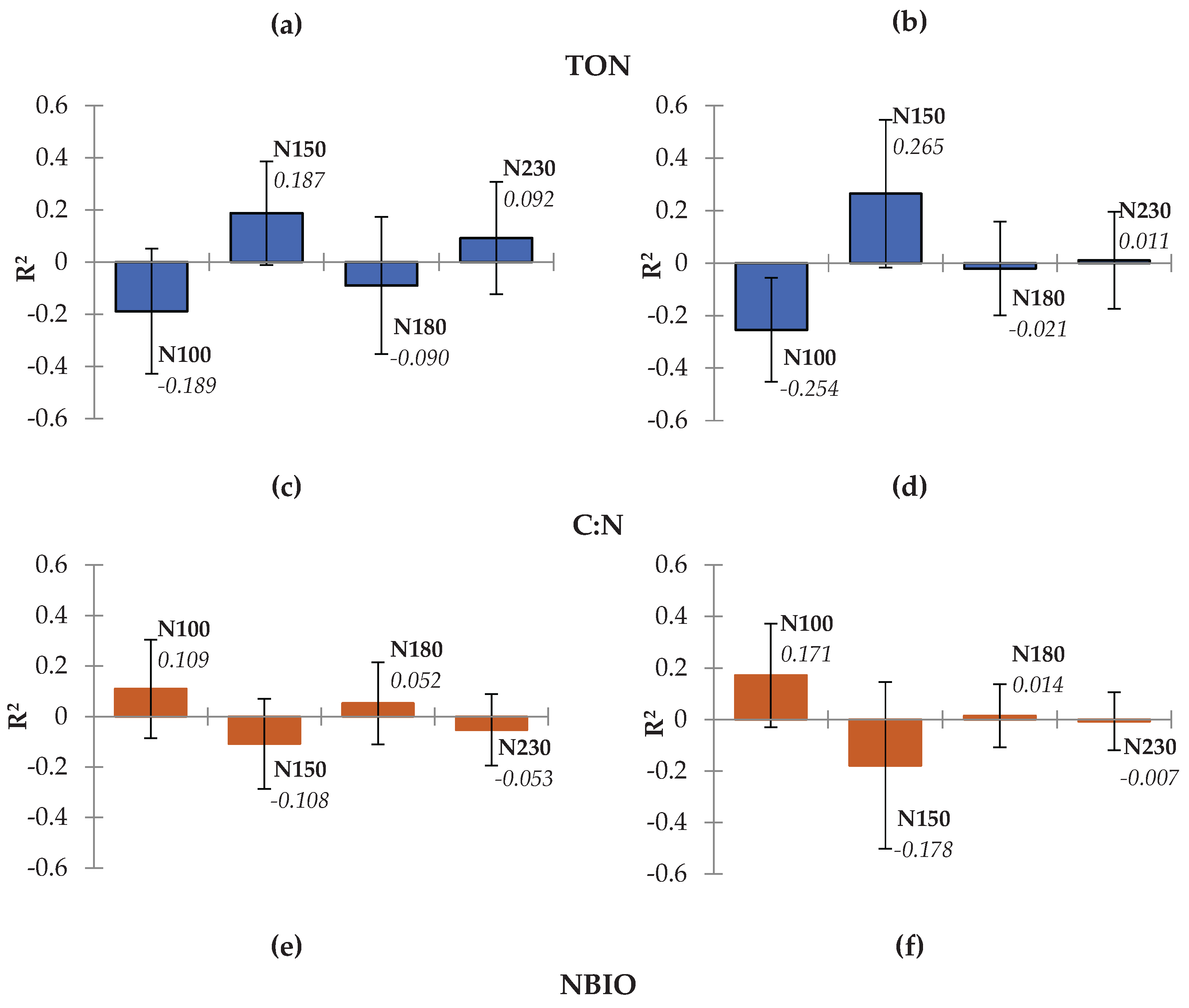

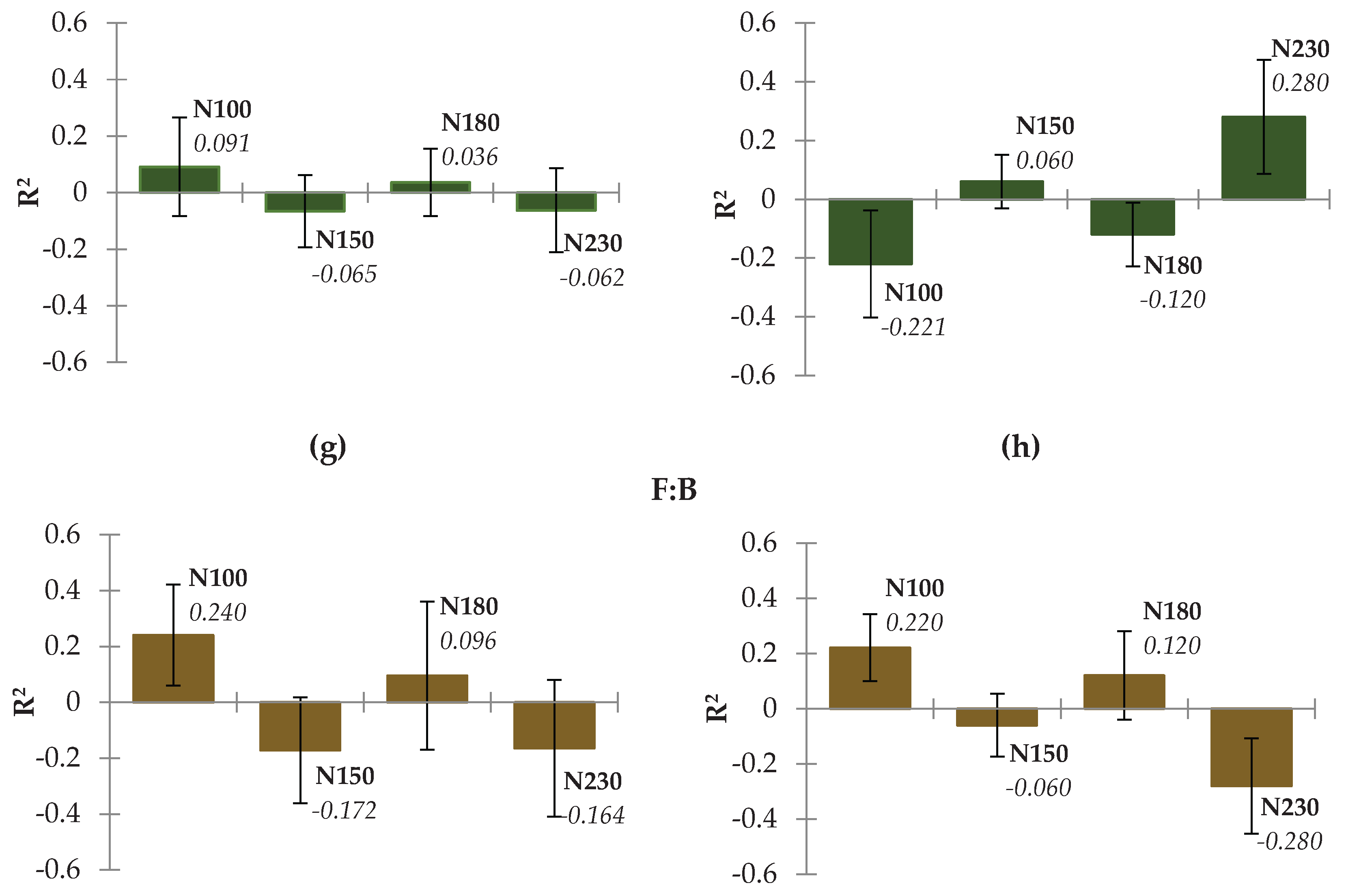

3.3. Relationship Between Applied Fertilization and Soil Properties

3.4. The PLS Regression for Soil Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foskolos, A.; Plomaritou, A., 2023. Holistic nutritional management as a tool to mitigate nitrogen pollution from dairy cattle farming. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 161(3), pp.313-317. [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, K.; Kumar, N.; Shandilya, C.; Mohapatra, S.; Bhayana, S.; Varma, A., 2020. Revisiting plant–microbe interactions and microbial consortia application for enhancing sustainable agriculture: a review. Frontiers in Microbiology, 11, p.560406. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F., Bennett, J.A., Crawford, K.M., Heinze, J., Pu, X., Luo, A. and Wang, Z., 2024. Global patterns and drivers of plant–soil microbe interactions. Ecology Letters, 27(1), p.e14364. [CrossRef]

- Tharanath, A.C., Upendra, R.S. and Rajendra, K., 2024. Soil symphony: A comprehensive overview of plant–microbe interactions in agricultural systems. Applied Microbiology, 4(4), pp.1549-1567. [CrossRef]

- Storer, K.E., Berry, P.M., Kindred, D.R. and Sylvester-Bradley, R., 2018. Identifying oilseed rape varieties with high yield and low nitrogen fertiliser requirement. Field Crops Research, 225, pp.104-116. [CrossRef]

- Shahini, S., Kachanova, T., Manushkina, T., Petrova, O. and Shevchuk, N., 2023. Using organic nitrogen fertilisers to improve soil health and increase yields. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 80(2), pp.433-441. [CrossRef]

- Martre, P., Dueri, S., Guarin, J.R., Ewert, F., Webber, H., Calderini, D., Molero, G., Reynolds, M., Miralles, D., Garcia, G. and Brown, H., 2024. Global needs for nitrogen fertilizer to improve wheat yield under climate change. Nature Plants, 10(7), pp.1081-1090. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Pubu, C., Zhu, Y., Hao, W., Zhang, G. and Han, J., 2023. Optimizing nitrogen application depth can improve crop yield and nitrogen uptake–A global meta-analysis. Field Crops Research, 295, p.108895. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N., Richards, K.G., Harty, M.A., Watson, C.J., Carolan, R., Krol, D., Lanigan, G.J. and Forrestal, P.J., 2021. Differing effects of increasing calcium ammonium nitrate, urea and urea+ NBPT fertiliser rates on nitrous oxide emission factors at six temperate grassland sites in Ireland. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 313, p.107382. [CrossRef]

- Akkamis, M. and Caliskan, S., 2023. Responses of yield, quality and water use efficiency of potato grown under different drip irrigation and nitrogen levels. Scientific Reports, 13(1), p.9911. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Q. and Huang, S.M., 2023. Effects of the combined application of organic and chemical nitrogen fertilizer on soil aggregate carbon and nitrogen: a 30-year study. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 22(11), pp.3517-3534. [CrossRef]

- Porwollik, V., Rolinski, S., Heinke, J., von Bloh, W., Schaphoff, S. and Müller, C., 2022. The role of cover crops for cropland soil carbon, nitrogen leaching, and agricultural yields–a global simulation study with LPJmL (V. 5.0-tillage-cc). Biogeosciences, 19(3), pp.957-977.

- Vogeler, I., Hansen, E.M. and Thomsen, I.K., 2023. The effect of catch crops in spring barley on nitrate leaching and their fertilizer replacement value. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 343, p.108282. [CrossRef]

- Böldt, M., Taube, F., Vogeler, I., Reinsch, T., Kluß, C. and Loges, R., 2021. Evaluating different catch crop strategies for closing the nitrogen cycle in cropping systems—Field experiments and modelling. Sustainability, 13(1), p.394. [CrossRef]

- Yokamo, S., Milinga, A.S. and Suefo, B., 2023. Alternative fertilization approaches in enhancing crop productivity and nutrient use efficiency: A review. Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science, 8(2), pp.244-249. [CrossRef]

- Norberg, L. and Aronsson, H., 2024. Effects of spring and autumn tillage, catch crops, and pig manure application on long-term nutrient leaching from a loamy sand. European Journal of Agronomy, 156, p.127156. [CrossRef]

- Daba, N.A., Li, D., Huang, J., Han, T., Zhang, L., Ali, S., Khan, M.N., Du, J., Liu, S., Legesse, T.G. and Liu, L., 2021. Long-term fertilization and lime-induced soil pH changes affect nitrogen use efficiency and grain yields in acidic soil under wheat-maize rotation. Agronomy, 11(10), p.2069. [CrossRef]

- Michael, P.S., 2021. Role of organic fertilizers in the management of nutrient deficiency, acidity, and toxicity in acid soils–A review. Journal of Global Agriculture and Ecology, 12(3), pp.19-30.

- Barłóg, P., Grzebisz, W. and Łukowiak, R., 2022. Fertilizers and fertilization strategies mitigating soil factors constraining efficiency of nitrogen in plant production. Plants, 11(14), p.1855. [CrossRef]

- Krasilnikov, P., Taboada, M.A. and Amanullah, 2022. Fertilizer use, soil health and agricultural sustainability. Agriculture, 12(4), p.462. [CrossRef]

- Jote, C.A., 2023. The impacts of using inorganic chemical fertilizers on the environment and human health. Organic and Medicinal Chemistry International Journal, 13(3), p.555864.

- Kuśmierz, S., Skowrońska, M., Tkaczyk, P., Lipiński, W. and Mielniczuk, J., 2023. Soil organic carbon and mineral nitrogen contents in soils as affected by their pH, texture and fertilization. Agronomy, 13(1), p.267. [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A., Guzman, J., Kovacs, P. and Kumar, S., 2022. Manure and inorganic fertilization impacts on soil nutrients, aggregate stability, and organic carbon and nitrogen in different aggregate fractions. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science, 68(9), pp.1261-1273. [CrossRef]

- Petraityte, D., Ceseviciene, J., Arlauskiene, A., Slepetiene, A., Skersiene, A. and Gecaite, V., 2022. Variation of soil nitrogen, organic carbon, and waxy wheat yield using liquid organic and mineral fertilizers. Agriculture, 12(12), p.2016. [CrossRef]

- Anušauskas, J., Steponavičius, D., Romaneckas, K., Lekavičienė, K., Zaleckas, E. and Sendžikienė, E., 2023. The influence of bacteria-inoculated mineral fertilizer on the productivity and profitability of spring barley cultivation. Plants, 12(6), p.1227. [CrossRef]

- Van Groenigen, J. W., Velthof, G. L., Oenema, O., Van Groenigen, K. J., & Van Kessel, C. (2010). Towards an agronomic assessment of N2O emissions: a case study for arable crops. European journal of soil science, 61(6), 903-913. [CrossRef]

- Martre, P., Jamieson, P. D., Semenov, M. A., Zyskowski, R. F., Porter, J. R., & Triboi, E. (2006). Modelling protein content and composition in relation to crop nitrogen dynamics for wheat. European Journal of Agronomy, 25(2), 138-154. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K. M., Reeves, P. G., & Jones, S. S. (2008). Relationship between yield and mineral nutrient concentrations in historical and modern spring wheat cultivars. Euphytica, 163(3), 381-390. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Wang, M., Mur, L. A. J., Shen, Q., & Guo, S. (2020). Unravelling the roles of nitrogen nutrition in plant disease defences. International journal of molecular sciences, 21(2), 572. [CrossRef]

- Tu, C., Booker, F. L., Watson, D. M., Chen, X. I. N., Rufty, T. W., Shi, W. E. I., & Hu, S. (2006). Mycorrhizal mediation of plant N acquisition and residue decomposition: impact of mineral N inputs. Global Change Biology, 12(5), 793-803. [CrossRef]

- Pan, S., Wang, Y., Qiu, Y., Chen, D., Zhang, L., Ye, C., ... & Hu, S. (2020). Nitrogen-induced acidification, not N-nutrient, dominates suppressive N effects on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Global Change Biology, 26(11), 6568-6580. [CrossRef]

- Jilling, A., Keiluweit, M., Contosta, A. R., Frey, S., Schimel, J., Schnecker, J., ... & Grandy, A. S. (2018). Minerals in the rhizosphere: overlooked mediators of soil nitrogen availability to plants and microbes. Biogeochemistry, 139(2), 103-122. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M. H., & Graham, J. H. (2018). Little evidence that farmers should consider abundance or diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi when managing crops. New Phytologist, 220(4), 1092-1107. [CrossRef]

- Ingraffia, R., Amato, G., Sosa-Hernández, M. A., Frenda, A. S., Rillig, M. C., & Giambalvo, D. (2020). Nitrogen type and availability drive mycorrhizal effects on wheat performance, nitrogen uptake and recovery, and production sustainability. Frontiers in plant science, 11, 760. [CrossRef]

- Stark, C., Condron, L. M., Stewart, A., Di, H. J., & O’Callaghan, M. (2007). Influence of organic and mineral amendments on microbial soil properties and processes. Applied Soil Ecology, 35(1), 79-93. [CrossRef]

- Ren, N., Wang, Y., Ye, Y., Zhao, Y., Huang, Y., Fu, W., & Chu, X. (2020). Effects of continuous nitrogen fertilizer application on the diversity and composition of rhizosphere soil bacteria. Frontiers in microbiology, 11, 1948. [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. In International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS): Vienna, Austria, 2022.

- ISO 10390:2005; Soil Quality—Determination of pH. International Standards Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- ISO 10694: 1995; Soil Quality—Determination of Organic and Total Carbon after Dry Combustion (Elementary Analysis). International Standards Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995.

- ISO 14256-2:2005; Soil quality — Determination of Nitrate, Nitrite and Ammonium in Field-Moist Soils by Extraction with Potassium Chloride Solution — Part 2. International Standards Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- Küster, E. Outline of a comparative study of criteria used in characterization of the actinomycetes. Int. Bull. Bacteriol. Nomencl. Taxon. 1959, 9, 98–104. [CrossRef]

- Domsch, K.H.; Gams, W.; Anderson, T.H. Compendium of Soil Fungi; IHW-Verlag: Eching, Germany, 2007; p. 672.

- Noulas, C., Torabian, S. and Qin, R., 2023. Crop nutrient requirements and advanced fertilizer management strategies. Agronomy, 13(8), p.2017. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q., Song, Y., An, Y., Lu, Y. and Zhong, G., 2024. Soil microorganisms: Their role in enhancing crop nutrition and health. Diversity, 16(12), p.734. [CrossRef]

- Cvetkov, M. and Tajnšek, A., 2009. Soil organic matter changes according to the application of organic and mineral fertilizers within long-term experiments. Acta Agriculturae Slovenica, 93(3), pp.311-320. [CrossRef]

- Sosulski, T. and Korc, M., 2011. Effects of different mineral and organic fertilization on the content of nitrogen and carbon in soil organic matter fractions. Ecological Chemistry and Engineering. A, 18(4), pp.601-609.

- Kuśmierz, S., Skowrońska, M., Tkaczyk, P., Lipiński, W. and Mielniczuk, J., 2023. Soil organic carbon and mineral nitrogen contents in soils as affected by their pH, texture and fertilization. Agronomy, 13(1), p.267. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Xu, Z., Zhao, J., Wang, Y. and Yu, Z., 2011. Excessive nitrogen application decreases grain yield and increases nitrogen loss in a wheat–soil system. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B-Soil & Plant Science, 61(8), pp.681-692. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.C., Di, H.J. and Moir, J.L., 2013. Nitrogen losses from the soil/plant system: a review. Annals of applied biology, 162(2), pp.145-173. [CrossRef]

- Bender, S.F. and van der Heijden, M.G., 2015. Soil biota enhance agricultural sustainability by improving crop yield, nutrient uptake and reducing nitrogen leaching losses. Journal of Applied Ecology, 52(1), pp.228-239.

- Yang, X., Lu, Y., Ding, Y., Yin, X., Raza, S. and Tong, Y.A., 2017. Optimising nitrogen fertilisation: A key to improving nitrogen-use efficiency and minimising nitrate leaching losses in an intensive wheat/maize rotation (2008–2014). Field Crops Research, 206, pp.1-10. [CrossRef]

- Elbl, J., Šimečková, J., Škarpa, P., Kintl, A., Brtnický, M. and Vaverková, M.D., 2020. Comparison of the agricultural use of products from organic waste processing with conventional mineral fertilizer: potential effects on mineral nitrogen leaching and soil quality. Agronomy, 10(2), p.226. [CrossRef]

- Allende-Montalbán, R., Martin-Lammerding, D., del Mar Delgado, M., Porcel, M.A. and Gabriel, J.L., 2022. Nitrate leaching in maize (Zea mays L.) and wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) irrigated cropping systems under nitrification inhibitor and/or intercropping effects. Agriculture, 12(4), p.478. [CrossRef]

- Wachendorf, M., Volkers, K.C., Loges, R., Rave, G. and Taube, F., 2006. Perfor-mance and environmental effects of forage production on sandy soils. IV. Impact of slurry application, mineral N fertilizer and grass understorey on yield and nitrogen surplus of maize for silage. Grass and Forage Science, 61(3), pp.232-242. [CrossRef]

- Kayser, M., Benke, M. and Isselstein, J., 2011. Little fertilizer response but high N loss risk of maize on a productive organic-sandy soil. Agronomy for sustainable development, 31(4), pp.709-718. [CrossRef]

- Mooshammer, M., Wanek, W., Hämmerle, I., Fuchslueger, L., Hofhansl, F., Knoltsch, A., Schnecker, J., Takriti, M., Watzka, M., Wild, B. and Keiblinger, K.M., 2014. Adjustment of microbial nitrogen use efficiency to carbon: nitrogen imbalances regulates soil nitrogen cycling. Nature communications, 5(1), p.3694. [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, E., Hatch, D., Murphy, D., Ledgard, S. and Watson, C., 2002. Verifying the nitrification to immobilisation ratio (N/I) as a key determinant of potential nitrate loss in grassland and arable soils. Agronomie, 22(7-8), pp.831-838. [CrossRef]

- Angus, J.F., Gupta, V.V.S.R., Pitson, G.D. and Good, A.J., 2014. Effects of banded ammonia and urea fertiliser on soil properties and the growth and yield of wheat. Crop and Pasture Science, 65(4), pp.337-352. [CrossRef]

- Grzyb, A., Wolna-Maruwka, A. and Niewiadomska, A., 2021. The significance of microbial transformation of nitrogen compounds in the light of integrated crop management. Agronomy, 11(7), p.1415. [CrossRef]

- Chapagain, T. and Riseman, A., 2015. Nitrogen and carbon transformations, water use efficiency and ecosystem productivity in monocultures and wheat-bean intercropping systems. Nutrient cycling in agroecosystems, 101(1), pp.107-121. [CrossRef]

- Bissett, A., Richardson, A.E., Baker, G. and Thrall, P.H., 2011. Long-term land use effects on soil microbial community structure and function. Applied Soil Ecology, 51, pp.66-78. [CrossRef]

- Don, A., Böhme, I.H., Dohrmann, A.B., Poeplau, C. and Tebbe, C.C., 2017. Microbial community composition affects soil organic carbon turnover in mineral soils. Biology and fertility of soils, 53(4), pp.445-456. [CrossRef]

- Khmelevtsova, L.E., Sazykin, I.S., Azhogina, T.N. and Sazykina, M.A., 2022. Influence of agricultural practices on bacterial community of cultivated soils. Agriculture, 12(3), p.371. [CrossRef]

- Han, P., Zhang, W., Wang, G., Sun, W. and Huang, Y., 2016. Changes in soil organic carbon in croplands subjected to fertilizer management: a global meta-analysis. Scientific reports, 6(1), p.27199. [CrossRef]

- Olin, S., Lindeskog, M., Pugh, T.A.M., Schurgers, G., Wårlind, D., Mishurov, M., Zaehle, S., Stocker, B.D., Smith, B. and Arneth, A., 2015. Soil carbon management in large-scale Earth system modelling: implications for crop yields and nitrogen leaching. Earth System Dynamics, 6(2), pp.745-768. [CrossRef]

- Elrys, A.S., Wang, J., Meng, L., Zhu, Q., El-Sawy, M.M., Chen, Z., Tu, X., El-Saadony, M.T., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J. and Cai, Z., 2023. Integrative knowledge-based nitrogen management practices can provide positive effects on ecosystem nitrogen retention. Nature Food, 4(12), pp.1075-1089. [CrossRef]

- Lessmann, M., Ros, G.H., Young, M.D. and de Vries, W., 2022. Global variation in soil carbon sequestration potential through improved cropland management. Global Change Biology, 28(3), pp.1162-1177. [CrossRef]

- de Nijs, E.A., Hicks, L.C., Leizeaga, A., Tietema, A. and Rousk, J., 2019. Soil microbial moisture dependences and responses to drying–rewetting: the legacy of 18 years drought. Global Change Biology, 25(3), pp.1005-1015. [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, A.M., Díaz, A., Tejada, M., Bautista, J., Rodríguez, B., Santa María, C., Revilla, E. and Parrado, J., 2010. Enzymatic production of an organic soil biostimulant from wheat-condensed distiller solubles: Effects on soil biochemistry and biodiversity. Process Biochemistry, 45(7), pp.1127-1133. [CrossRef]

- Hellequin, E., Monard, C., Chorin, M., Le Bris, N., Daburon, V., Klarzynski, O. and Binet, F., 2020. Responses of active soil microorganisms facing to a soil biostimulant input compared to plant legacy effects. Scientific Reports, 10(1), p.13727. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Ma, H., Ma, H., Lei, F., He, D., Huang, X., Yang, H. and Fan, G., 2023. Comprehensive effects of N reduction combined with biostimulants on N use efficiency and yield of the winter wheat–summer maize rotation system. Agronomy, 13(9), p.2319. [CrossRef]

| Indices | Experimental site | |

|---|---|---|

| Pedological indices | ||

| Soil type | Calcaric Luvisol [37] | |

| Soil texture | loam | |

| Sand, % | 26.1 | |

| Silt, % | 48.4 | |

| Clay, % | 25.5 | |

| pHKCl | 7.42 | |

| Soil organic matter, g kg-1 | 13.8 | |

| Ntotal, g kg-1 | 1.13 | |

| Mobile P2O5, mg kg−1 | 152 | |

| Mobile K2O, mg kg−1 | 161 | |

| Climatic indices | ||

| Conducting experiment average (SRC 2019–2022) |

Long-term average (SRC 1974–2020) |

|

| Total annual precipitation, mm | 572.3 | 679.7 |

| Annual mean temperature, ◦C | 8.4 | 7.5 |

| Growing season’s total precipitation, mm |

343 | 425 |

| Growing season’s mean air temperature, ◦C |

14.5 | 14.3 |

| Fertilization | Treatments | pHKCl | Mineral nitrogen content (mg kg-1) | C:N ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 2 | Year 4 | Year 2 | Year 4 | Year 2 | Year 4 | ||

| N100 | B-_O- | 6.8±0.00d | 7.1±0.03c | 0.11±0.004d | 0.13±0.018c | 13.7±1.03a | 12.1±0.62a |

| B-_O+ | 7.3±0.00a | 7.4±0.09ab | 0.19±0.009abc | 0.18±0.039bc | 10.1±1.33abc | 11.6±0.76a | |

| B+_O- | 7.0±0.00c | 7.3±0.00bc | 0.18±0.012abcd | 0.14±0.017c | 7.5±0.68c | 12.5±0.49a | |

| B+_O+ | 7.2±0.00b | 7.2±0.09bc | 0.17±0.011abcd | 0.12±0.005c | 9.5±0.48abc | 11.6±0.16a | |

| N150 | B-_O- | 6.8±0.00d | 7.4±0.03ab | 0.21±0.015abc | 0.22±0.030abc | 9.6±0.63abc | 11.4±0.69a |

| B-_O+ | 7.3±0.00a | 7.7±0.10a | 0.20±0.031abc | 0.29±0.022a | 9.8±1.07abc | 5.6±0.20b | |

| B+_O- | 7.0±0.00c | 7.5±0.09ab | 0.20±0.017abc | 0.16±0.012bc | 7.4±1.13c | 12.9±1.19a | |

| B+_O+ | 7.2±0.00b | 7.3±0.03bc | 0.18±0.007abcd | 0.16±0.009bc | 9.9±1.37abc | 12.0±0.93a | |

| N180 | B-_O- | 7.2±0.00b | 7.3±0.00bc | 0.17±0.018abcd | 0.16±0.04bc | 8.8±0.75abc | 10.9±0.18a |

| B-_O+ | 7.0±0.00c | 7.3±0.06bc | 0.14±0.009cd | 0.17±0.021bc | 10.8±0.22abc | 11.8±0.33a | |

| B+_O- | 7.3±0.00a | 7.5±0.03ab | 0.24±0.020a | 0.17±0.018bc | 7.8±0.44bc | 13.0±0.80a | |

| B+_O+ | 6.8±0.00d | 7.3±0.00bc | 0.15±0.014abcd | 0.21±0.011abc | 12.7±1.48ab | 10.8±0.43a | |

| N230 | B-_O- | 7.2±0.00b | 7.2±0.12bc | 0.18±0.010abcd | 0.14±0.020bc | 9.1±0.31abc | 11.3±0.19a |

| B-_O+ | 7.0±0.00c | 7.4±0.06ab | 0.15±0.006bcd | 0.15±0.018bc | 10.2±0.80abc | 11.0±0.49a | |

| B+_O- | 7.3±0.00a | 7.6±0.03a | 0.20±0.024abc | 0.18±0.011bc | 9.9±1.54abc | 11.9±0.38a | |

| B+_O+ | 6.8±0.00d | 7.5±0.03ab | 0.23±0.007abcd | 0.24±0.023ab | 8.7±0.93abc | 11.0±0.11a | |

| Fertilization | Treatments | Soil total microbial abundance, ×106 CFU |

Fungi:bacteria ratio |

Biological nitrogen (NH4+ + NO3-) (mg kg-1) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 2 | Year 4 | Year 2 | Year 4 | Year 2 | Year 4 | ||

| N100 | B-_O- | 2.0±0.04cd | 2.0±0.13bcd | 0.018±0.0018abcd | 0.030±0.0015b | 114±4.3efg | 117±3.6ef |

| B-_O+ | 2.0±0.01cd | 2.4±0.08abc | 0.020±0.0007abc | 0.032±0.0009b | 174±10.4ab | 121±2.7def | |

| B+_O- | 2.0±0.03cd | 1.3±0.12e | 0.015±0.0009def | 0.020±0.0018cde | 161±4.6abcd | 127±5.3cdef | |

| B+_O+ | 1.8±0.03de | 2.6±0.08ab | 0.015±0.0006de | 0.029±0.0015bc | 122±16.5cdefg | 120±4.3def | |

| N150 | B-_O- | 1.7±0.05ef | 1.6±0.09de | 0.010±0.0009fg | 0.014±0.0009e | 118±10.7defg | 120±1.5def |

| B-_O+ | 1.9±0.02d | 2.4±0.03abc | 0.016±0.0006bcd | 0.025±0.0023bcd | 117±6.7defg | 133±5.1abcde | |

| B+_O- | 1.6±0.06f | 1.6±0.14de | 0.011±0.0007ef | 0.015±0.0019e | 137±4.1bcdefg | 121±4.1def | |

| B+_O+ | 2.4±0.06a | 2.8±0.21a | 0.014±0.0003def | 0.032±0.0010b | 166±6.7abc | 145±0.6abc | |

| N180 | B-_O- | 1.7±0.02ef | 1.3±0.08e | 0.010±0.0003g | 0.019±0.0012cde | 110±3.6fg | 109±4.6f |

| B-_O+ | 1.9±0.05d | 2.7±0.24ab | 0.016±0.0009bcd | 0.032±0.0019b | 154±3.3abcdef | 137±7.1abcd | |

| B+_O- | 1.6±0.05ef | 1.4±0.11de | 0.016±0.0007cd | 0.018±0.0018de | 108±7.2g | 121±0.0def | |

| B+_O+ | 2.3±0.04ab | 2.8±0.12a | 0.021±0.0009a | 0.047±0.0026a | 183±10.0a | 151±4.9a | |

| N230 | B-_O- | 1.6±0.02ef | 1.3±0.15e | 0.010±0.0012fg | 0.014±0.0017e | 157±15.1abcde | 147±5.2ab |

| B-_O+ | 2.1±0.06bc | 1.8±0.04cde | 0.014±0.0007def | 0.017±0.0006de | 134±9.4bcdefg | 150±3.2a | |

| B+_O- | 1.7±0.03ef | 1.5±0.05de | 0.008±0.0003g | 0.014±0.0015e | 108±1.5g | 132±1.0abcde | |

| B+_O+ | 1.7±0.03ef | 2.7±0.12a | 0.020±0.0009ab | 0.028±0.0035bc | 124±4.6cdefg | 128±1.5bcdef | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).