1. Introduction

The incidence of vaginal vault prolapse (VVP) has been reported to occur in 11.6% of women with a hysterectomy performed for prolapse versus 1.8% of women with a hysterectomy for other benign diseases [

1]. The frequency of VVP requiring surgical repair has been estimated to be between 6% and 8% [

2].

The surgical management of VVP has been investigated through many decades. Many surgical options have been described, including vaginal, abdominal, and laparoscopic procedures. Still today, pelvic surgeons vary in their approaches. The choice of operation usually depends on experience of the surgeon and tradition in the institution.

Patients with VVP usually have coexistent pelvic floor defects e.g. a cystocele, rectocele or enterocele. [

3]

Following the publication from Haylen BT et al [

4] describing the MUSPACC (midline uterosacral plication anterior colporrhaphy combo) procedure, we changed our clinical practice and started performing an extraperitoneal midline uterosacral plication above the vaginal vault and anterior colporrhaphy through a single midline anterior wall incision in patients with cystocele and vaginal vault prolapse.

The preliminary surgical report from Haylen et al showed that the MUSPACC procedure is safe with minimal blood loss and minimal risk to the ureters [

4]. Short-term anatomical results were promising.

The aims of this study were to evaluate peri- and postoperative complications and vaginal and urinary symptoms including patient satisfaction 3 months postoperatively.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective cohort study included all women who underwent the MUSPACC procedure in our department during a 5-year period between January 2019 and January 2024. A total of 58 patients were identified.

All patients completed three modified prolapse questions from the International Consultation on Incontinence-Vaginal Symptoms (ICIQ-VS) [

5] and the International Consultation on Incontinence – Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF) [

6,

7] before surgery and 3 months postoperatively. The three modified questions from ICIQ-VS used in our evaluation of symptomatic bulge sensation were: 1: “Do you feel a lump or bulge come out of your vagina or can you feel a lump in or outside of your vagina?” (ever (0), occasionally (1), sometimes (2), most of the time (3) or all of the time (4)) and 2: “How much does this bother you?” not at all (0), a little (1), some (2), very much (3) and 3: “How much does this affect your daily life?” (0–10). A score was constructed with 0 in an asymptomatic patient and a score of 17 in a patient with maximum bother. ICIQ-UI-SF was used to evaluate the severity of urinary incontinence and its impact on health-related quality of life. The short form contains three scored items and an un-scored self-diagnostic item. A total score for the three scored items is calculated by adding them up. A score of 0 indicates a totally continent patient. The maximum score for worst incontinence is 21. The un-scored self-diagnostic item is used to classify the type of incontinence: stress, urge, mixed or undefined incontinence. Undefined UI is described as “leaks when you have finished urinating and are dressed” and “leaks for no obvious reasons”. De novo incontinence was defined as an ICIQ-UI-SF > 0 three months postoperatively. The Danish version of the ICIQ-UI SF has been translated from English but has not been validated. Moreover, patients were questioned about whether they felt “cured”, “greatly improved”, “somewhat improved”, “not improved”, or “worsened” regarding their surgical operation [

8,

9].

Demographic data included age, body mass index (BMI), number of births, previous caesarean sections and previous prolapse and incontinence operations. Preoperative evaluation included physical examination.

The MUSPACC procedure was performed according to Haylen et al [

4] combining local anesthesia with general anesthesia. A midline anterior vaginal wall incision was made from the region of the bladder neck to the vaginal vault. The bladder and pubocervical fascia were then mobilized by blunt and sharp dissection (1) laterally off the vaginal skin and (2) dorsosuperiorly off the extraperitoneal aspects of the vaginal vault. The intermediate section of the uterosacral ligament (USL) is a consistent finding accessed dorsolaterally to the midline and on the internal aspects of the exposed vaginal vault (superior to the cuff line). A midline plication of the contralateral USLs was performed, using a 2-0 delayed absorbable monofilament suture. A standard anterior colporrhaphy with 2-0 delayed continuous absorbable polyfilament suture, in one row was performed. The last stich involving the conjoined sacrouterine ligaments. The vaginal epithelium was then trimmed, and the anterior vaginal wall was closed with a continuous 2-0 absorbable suture. The urethral Foley catheter was removed at the end of the surgery.

All procedures were performed by the same four surgeons using a standardized technique.

Postoperative follow-up (clinical or telephone) at three months was performed in 56 patients with missing data for 2 patients.

All data extracted were entered into The Research Electronic Data Capture (RedCap), which is browser-based, metadata-driven electronic data capture software and workflow methodology for designing clinical and translational research databases.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study population.

The study was approved and registered at The Health department, Region Nord Jylland, Denmark, ID number K2024-175. The study was an quality assurance project therefore there was no need to obtain informed consent for each patient.

3. Results

A total of 58 patients underwent MUSPACC procedure during the study period. No other concomitant procedures were performed.

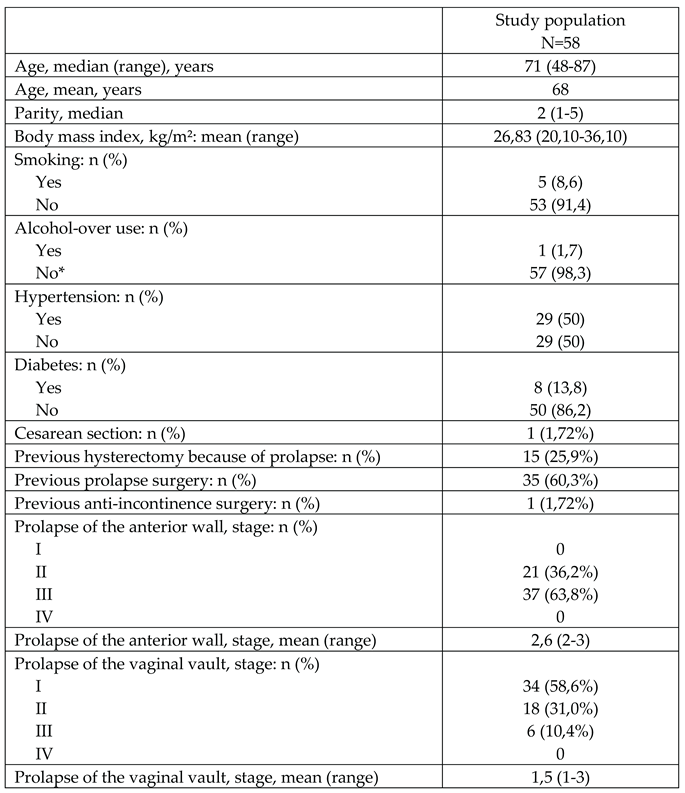

Demographic data of the study population and the preoperative stages of prolapse are shown in

Table 1.

56 patients attended a 3-month follow-up. At the 3 months` follow-up, patients had a significant improvement in vaginal symptoms with a preoperative mean ICIQ-VS score of 15.2 declining to 1.16.

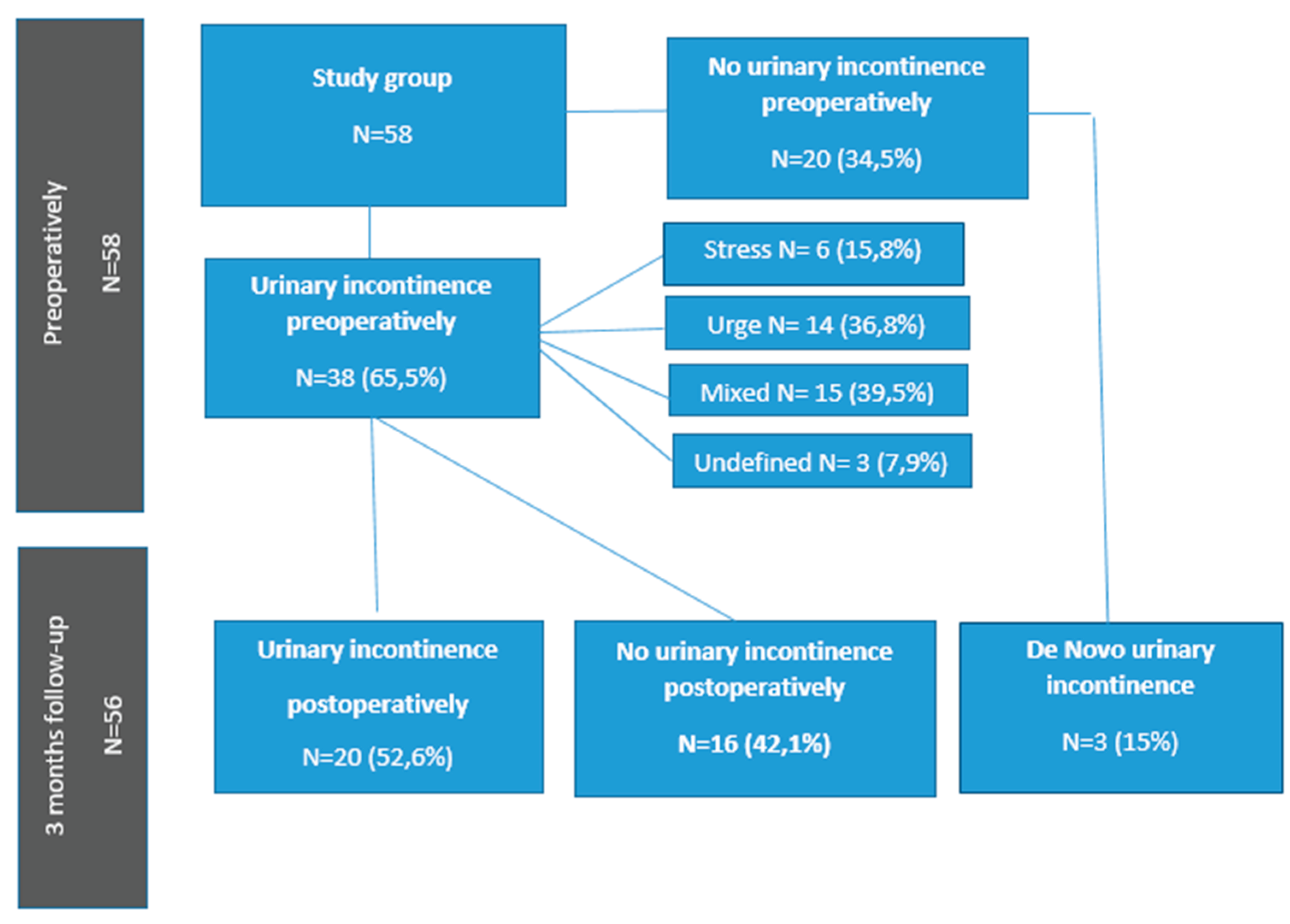

Postoperative changes in urinary incontinence are shown in

Figure 1.

A total of 16 patients (42,1%) with preoperative UI became completely dry after the MUSPACC procedure. Three patients (15%) experienced de novo UI 3 months after surgery. A total of 11 patients (55%), who remained incontinent after prolapse surgery according to the ICIQ-UI SF showed improvement in UI and in two patients (10%) urinary incontinence symptoms deteriorated. Mean ISIQ-UI-SF score before surgery was 6.72, which declined to 3.75 postoperatively.

Regarding patient satisfaction, 54 patients (96,4%) felt “cured”, “greatly improved” and “somewhat improved”, 2 women felt “not improved” at 3 months follow-up.

Perioperative complications occurred in one patient, who had a small bladder perforation, which occurred during dissection and was recognized and repaired at the time of the operation. Twelve patients (20,7%) experienced different postoperative complications: postoperative urinary tract infection (N=5), postoperative voiding dysfunction (N=4), postoperative bleeding/hematoma (N=3), which were managed conservatively, postoperative pain (N=2), and postoperative infection (N=1) which were all managed without reoperation.

One patient experienced a postoperative fistula between right ureter and vagina (N=1). The patient was a 74-year-old woman, with a history of vaginal hysterectomy, presented with a grade 3 cystocele and grade 2 apical prolapse. A MUSPACC operation was performed without perioperative complications. The following day the patient was discharged from the hospital. One month postoperatively the patient presented with oozing incontinence, but no signs of infection or pain. A leakage of clear fluid from the vaginal cicatrice was found. Ultrasound showed a normal bladder capacity and right sided hydronephrosis. The vaginal fluid was tested for creatinine and showed elevated values of > 3500 umol/l, diagnostic of urine leakage. To ease detection of the vesicovaginal fistula, a sterile solution made of methylene blue (MB) and a saline solution was prepared and instilled into the bladder, but no leakage of MB was detected. Computed tomography (CT)-urography confirmed right-sided hydroureter and hydronephrosis and showed contrast in vagina as a sign of lesion of the urinary tract. A nephrostomy catheter was administered, and symptoms of urinary incontinence diminished. In addition, an antegrade pyelography was performed and showed slow passage of contrast through the distal ureter on the right side and leakage of contrast through the vaginal wall as a sign of a fistula. The patient was referred to a specialized department awaiting robot assisted laparoscopy with neo-implantation of the right ureter. Meanwhile, a right double-J (JJ) stent was placed. The JJ stent was removed 6 weeks postoperatively following a normal CT urography. A renography confirmed regained normal renal function. There was no longer an indication for neo-implantation of the right ureter.

4. Discussion

In this study, we found an improvement in vaginal and urinary symptoms and a high patient satisfaction. The rate of perioperative and serious postoperative complications was low.

Our study results showed a significant improvement in vaginal symptoms 3 months after the MUSPACC procedures. We found no other studies to compare our 3 months results against. Haylen et al [

4] described subjective and objective results after MUSPACC procedure (N=41) at early follow-up (mean, 6,5 weeks; 4-9). All patients were asymptomatic for prolapse with no recurrences regarding apical support.

This study found, that 38 (65,5%) of 58 patients had concomitant UI. A total of 42,1% of patients with preoperative UI became completely dry after MUSPACC procedures alone, and up to 36% of women experienced improvement in UI 3 months after surgery. In our opinion, there is no need to perform a concomitant anti-incontinence procedure, and it is better to await effects of prolapse surgery alone [

10].

Three patients (15%) developed de novo UI 3 months after MUSPACC procedure. No data on MUSPACC procedure and risk of de novo UI has been found. Other studies however showed quite similar incidences of de novo UI after vaginal prolapse surgery [

9,

11,

12,

13]. Khayyami et al [

11] included 1198 urinary continent women who underwent POP surgery. The risk of de novo UI was 15%. Their study also showed that twice as many women with BMI ≥ 30 had de novo UI compared with women with BMI < 25. [

11] We couldn’t confirm their findings as all women with de novo UI, in our study, had BMI < 25.

Preoperatively 63,8% of our patients had stage 3 cystocele and 58,6% stage 1 vaginal vault prolapse (

Table 1). In Haylen´s et al [

4] paper, patients who underwent MUSPACC procedure preoperatively had anterior vaginal prolapse mean stage 2.0 and apical vaginal prolapse mean stage 1,4. Almost 42% of our patients had stage 2 and stage 3 vaginal vault prolapse before surgery which could suggest that the MUSPACC procedure is also a good surgical option for more advanced vaginal vault prolapse.

The most common postoperative complication was urinary tract infection (UTI), which occurred in 9% of patients. Patients with symptoms of urinary tract infection, in our country, usually contact their general practitioner and receive treatment. No patients needed hospitalization due to UTI.

Haylen BT et al [

4] had no ureteric incident either during 41 series described in the article or in over 300 cases of MUSPACC before or after this review series. In contrast to this paper, the most serious complication after MUSPACC procedure, in our study, was a postoperative fistula between right ureter and vagina.

We report a rare complication after MUSPACC surgery and want to make pelvic organ surgeons more aware of this type of complication.

Prior to this case cystoscopy was not a standard during MUSPACC procedures. Cystoscopy performed perioperatively may have led to immediate detection and management of this complication. Gilmour et al. and Sahai et al. [

14,

15] confirms that the use of cystoscopy can improve the detection of urinary tract injuries.

Routine cystoscopy has now been introduced, and no peri- or postoperative urinary tract injuries have been experienced since this alteration in procedure.

Our study revealed that 96,4% of patients were satisfied with the treatment, and none had worsening of prolapse symptoms after surgery. Two patients stated no improvement at 3 months follow-up, both patients had experienced postoperative complications (postoperative voiding dysfunction, UTI, hematoma and pain). One patient had ICIQ-VS score of 0, but did not experience improvement in her mixed urinary incontinence with ICIQ-UI SF score of 18. It could be considered that other bothersome pelvic floor symptoms such as postoperative bladder and bowel symptoms might be the main reason of a lower satisfaction rate after prolapse surgery.

The strength of our study is that the same questionnaire was used both pre- and postoperatively, giving more exact information about changes in vaginal and UI symptoms. All the data were entered into the database when events took place.

The limitations of our study are a small cohort and short-term (3 months) follow-up. No patients were tested postoperatively for UI, but patients who scored 0 on ISIQ-UI SF were considered continent.

Additional studies are required to validate our results.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the MUSPACC procedure is a good surgical option for treatment of vaginal vault prolapse and cystocele with a positive impact on vaginal and urinary symptoms, high patient satisfaction and a low rate of serious postoperative complications. Cystoscopy should be performed perioperatively for immediate detection and management of possible lesions of urinary tract.

Author Contributions

A Ugianskiene: Project development, Data Collection and analysis, Manuscript writing CS Juhl: Project development, Data collection, Manuscript editingK Glavind: Project development, manuscript writing/editing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved and registered at The Health department, Region Nord Jyl-land, Denmark, ID number K2024-175.

Informed Consent Statement

The study was an quality assurance project there-fore there was no need to obtain informed consent for each patient.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Acknowledgments

We have presented our poster “A uterovaginal fistula following MUSPACC surgery” MN, Ugianskis A, Ugianskiene A during 16th EUGA Annual Congress. The abstract was published in the abstract book.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VVP |

vaginal vault prolapse |

| MUSPACC |

midline uterosacral plication anterior colporrhaphy combo |

| ICIQ-VS |

International Consultation on Incontinence-Vaginal Symptoms |

| ICIQ-UI SF |

International Consultation on Incontinence – Urinary Incontinence Short Form |

| UI |

urinary incontinence |

| UTI |

urinary tract infection |

References

- Marchionni M, Bracco GL, Checcucci V, Carabaneanu A, Coccia EM, Mecacci F et al. True incidence of vaginal vault prolapse. Thirteen years of experience. J Reprod Med. 1999.

- Aigmueller T, Dungl A, Hinterholzer S, Geiss I, Riss P. An estimation of the frequency of surgery for posthysterectomy vault prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(3):299-302. [CrossRef]

- Sederl J. Zur operation des prolapses der blind endigenden sheiden. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1958;18:824–828.

- Haylen TB, Yang V, Vu D, Tse K. Midline uterosacral plication anterior colporrhaphy combo (MUSPACC): preliminary surgical report. Int Urogynecol J 2011 ;22(1):69-75. [CrossRef]

- Price N, Jackson SR, Avery K, Brookes ST, Abrams P. Development and psychometric evaluation of the ICIQ vaginal symptoms questionnaire: the ICIQ-VS. BJOG 2006;113(6):700–12.

- Abrams P, Avery K, Gardener N, Donovan J. ICIQ advisory board. The international consultation on incontinence modular questionnaire: www. iciq.net. J Urol 2006;175:1063–6. [CrossRef]

- Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, Shaw C, Gotoh M, Abrams P. ICIQ: a brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2004;23(4):322–30.

- Ugianskiene A., Glavind K. (2021). Follow-up of patients after colpectomy or Le Fort colpocleisis: Single center experience. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 262, 142-146. [CrossRef]

- Ugianskiene A, Kjærgaard N, Inger Lindquist AS, Larsen T, Glavind K. Retrospective study on de novo postoperative urinary incontinence after pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017 ;219:10-14. [CrossRef]

- Ugianskiene A, Kjærgaard N, Larsen T, Glavind K. What happens to urinary incontinence after pelvic organ prolapse surgery? Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30(7):1147-1152. [CrossRef]

- Khayyami Y, Elmelund M, Lose G, Klarskov N. De novo urinary incontinence after pelvic organ prolapse surgery-a national database study. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31(2):305-308. [CrossRef]

- Borstad E, Rud T. The risk of developing urinary stress-incontinence after vaginal repair in continent women. A clinical and urodynamic follow-up study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1989;68(6):545-9. [CrossRef]

- Hafidh BA, Chou Q, Khalil MM, Al-Mandeel H. De novo stress urinary incontinence after vaginal repair for pelvic organ prolapse: one-year follow-up. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;168(2):227-30. [CrossRef]

- Gilmour DT, Das S, Flowerdew G (2006) Rates of urinary tract injury from gynecologic surgery and the role of intraoperative cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol 107:1366–1372. [CrossRef]

- Sahai A, Ali A, Barratt R, Belal M, Biers S, Hamid R et al (2021) British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) consensus document: management of bladder and ureteric injury. BJU Int 128:539–547. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).