1. Introduction

In recent decades, the professional landscape has placed increasing emphasis on the ability of organizations to deliver projects with greater efficiency, predictability, and value creation [

1]. Project Management (PM) has consequently evolved from a specialized function into a strategic organizational capability, supported by established standards and best practices that provide structured guidance to practitioners [

2]. These frameworks, such as the PMBOK Guide, have historically been tailored for large-scale enterprises, reflecting the complex processes, formal governance structures, and resource availability characteristic of such organizations.

Earlier PM research predominantly concentrated on the practices and systems deployed in large corporations, inherently assuming a level of organizational maturity and resource availability not always present in smaller enterprises [

3]. However, the business environment has changed significantly with the recognition of the critical role played by Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) in global economies. According to the European Commission [

4], SMEs represent over 99% of all businesses in the European Union, contribute to two-thirds of private sector employment, and act as engines for innovation and entrepreneurship. This macroeconomic relevance has intensified the need for SMEs to adopt effective PM practices to remain competitive and resilient in volatile markets.

Despite their importance, SMEs often face challenges when adopting conventional PM approaches. Traditional methodologies tend to emphasize comprehensive documentation, extensive upfront planning, and formalized governance—practices that may be overly resource-intensive for SMEs with lean teams and fluid operational structures [

5,

6]. Consequently, direct implementation of these methods may result in inefficiencies or outright resistance from staff, especially where flexibility and speed of execution are critical. To address these limitations, agile methodologies have emerged as an alternative, offering an iterative, adaptive, and team-centric framework capable of responding to dynamic project requirements [

7]. Agile principles prioritize working deliverables, continuous stakeholder collaboration, and rapid adaptation over rigid processes and heavy documentation [

8,

9].

Nevertheless, while agile methods excel in flexibility, they often underemphasize high-level planning, long-term resource forecasting, and formal reporting, which remain essential in certain business contexts. This gap has led to the emergence of

hybrid PM approaches, which blend the rigor of traditional planning with the adaptability of agile execution. Such models have been found to improve both responsiveness and governance, making them particularly well-suited to SMEs managing a diverse portfolio of projects [

8,

10].

The implementation of a Project Management System (PMS) within SMEs offers the potential to institutionalize such hybrid practices. A PMS integrates defined PM processes, supporting tools, and governance mechanisms into a cohesive framework. When complemented by a Project Management Information System (PMIS), the PMS benefits from digital capabilities such as centralized data storage, real-time performance monitoring, and enhanced collaboration [

11,

12]. However, successful PMS adoption requires alignment with the organization’s maturity level, operational culture, and change management capacity.

This study examines the implementation of a PMS—underpinned by a PMIS—in a Portuguese SME operating across multiple business sectors. The PMS was designed to accommodate diverse project types by incorporating both traditional and agile elements into a unified hybrid approach. By documenting the implementation process, analyzing encountered challenges, and highlighting both successes and limitations, this work aims to provide actionable insights for SMEs seeking to adopt or refine PM systems. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section II reviews relevant literature and theoretical foundations; Section III details the research methodology; Section IV presents the implementation process; Section V discusses the results; Section VI offers conclusions; and Section VII outlines directions for future work.

2. Related Work

2.1. Project Management in SMEs

Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) are recognized as critical contributors to both economic and social development worldwide [

6]. In the European Union alone, SMEs constitute over 99% of all registered businesses and provide approximately two-thirds of total employment [

4]. These organizations foster entrepreneurship, stimulate innovation, and serve as essential drivers of economic growth. Despite their importance, SMEs differ markedly from large enterprises in their operational constraints, organizational culture, and resource structures, all of which influence the adoption and effectiveness of Project Management (PM) practices [

3,

6,

13,

14].

Studies have shown that SMEs tend to require PM approaches that are leaner, less bureaucratic, and more adaptable than those used in large corporations [

5,

6]. The direct transplantation of enterprise-scale PM frameworks into SMEs often results in inefficiencies, excessive administrative burden, or poor adoption rates [

13]. Nonetheless, effective PM practices are strongly linked to SME competitiveness, profitability, and long-term survival [

3,

15,

16]. In practice, many SMEs already employ elements of structured PM, such as requirements management, resource allocation, and risk management [

6,

16], although these practices are frequently applied in an ad hoc manner through templates, informal processes, and lightweight tools [

17].

Prior empirical work reveals that common PM tools in SMEs include kick-off meetings, Gantt charts, progress meetings, and baseline plans [

17]. However, the diversity of project types in SMEs—ranging from IT development to product launches—necessitates a flexible PM model that can adapt to varying levels of complexity, uncertainty, and stakeholder involvement.

2.2. Hybrid Project Management Approaches

Traditional PM methodologies, often exemplified by the Waterfall model, are characterized by sequential execution, comprehensive documentation, and rigorous upfront planning [

8,

18]. These methods excel in projects with well-defined requirements and low volatility but may lack responsiveness when rapid adaptation is required. Conversely, agile methodologies were developed to prioritize adaptability, incremental delivery, and close stakeholder collaboration [

8,

9]. Originating in software development, agile approaches reduce reliance on heavy documentation and instead focus on delivering value through iterative cycles [

7]. While this adaptability suits fast-changing environments, it can be insufficient for projects requiring strict compliance, formal reporting, or long-term forecasting.

The limitations of both approaches have prompted the adoption of

hybrid PM models, which integrate the planning rigor of traditional methodologies with the flexibility of agile techniques [

8,

10]. In such models, initial project phases often follow traditional methods to establish high-level objectives, scope, and contractual agreements, while design and implementation stages leverage agile iterations to reduce rework and accelerate delivery [

8]. Hybrid approaches are increasingly recognized by the Project Management Institute (PMI) as a growing trend in PM practice [

2], with scholars emphasizing their potential to yield more robust and adaptable processes [

10].

2.3. Project Management Information Systems

The evolution of Project Management Information Systems (PMIS) has been pivotal in enabling organizations to implement PM practices more efficiently [

11,

12]. A PMIS consolidates planning, scheduling, budgeting, resource allocation, documentation, and performance monitoring into an integrated platform [

19]. These systems are designed to support the entire project lifecycle, from initiation to closure, and can manage multiple projects concurrently [

11].

Effective PMIS solutions are characterized by usability, flexibility, interoperability with other enterprise systems, and real-time information accessibility [

12]. They improve decision-making, facilitate collaboration, and enhance both individual and overall project performance. However, as [

20] and [

21] point out, the success of a PMIS is not solely determined by its technical capabilities; embedding such systems into the organizational culture is equally critical. In SMEs, where PM maturity is often low [

22], the challenge lies in aligning the system’s complexity with user capabilities and existing workflows.

Case studies have demonstrated that PMIS adoption in SMEs can lead to significant improvements in transparency, accountability, and operational efficiency [

5]. Nonetheless, barriers such as resistance to change, insufficient training, and lack of top management commitment remain recurring obstacles [

20,

21]. To overcome these barriers, gradual implementation strategies, ongoing stakeholder engagement, and the creation of an internal body of knowledge are recommended [

20,

23].

In summary, existing literature highlights that SMEs require PM frameworks and tools that balance structure with flexibility. Hybrid methodologies, supported by appropriately tailored PMIS solutions, offer a promising pathway. However, their successful adoption depends on careful alignment with organizational maturity, robust change management, and sustained leadership support.

3. Methodology

This study adopts a pragmatic, problem-centred research stance aimed at producing actionable insights for practitioners while delivering rigorous qualitative evidence for academic appraisal. The methodological intent was to document, examine and interpret the implementation process of a Project Management System (PMS) supported by a Project Management Information System (PMIS) in a small Portuguese enterprise. The research design emphasises a deep, context-sensitive inquiry that combines participative observation with stakeholder interviews and focused group feedback to capture both technical and social dimensions of implementation [

24,

25].

3.1. Research Paradigm and Strategy

The investigation follows a functionalist, case-based strategy. The functionalist orientation privileges explanation and solution-seeking: it treats the PMS implementation as a socio-technical problem where improved practices and artifacts (the PMS and PMIS) must align with organisational routines and capabilities. A single in-depth case study was chosen as the principal research strategy because it enables exploration of complex interactions between technology, organizational routines and human actors within their natural setting [

24]. Case study research is particularly suitable here because the aim is not broad statistical generalisation but detailed understanding and transfer of lessons to similar SMEs [

25].

3.2. Case Selection and Context

The focal organisation is a privately-owned Portuguese SME (approx. 35 employees) operating across several business lines but with a predominance of information technology activities. In the year prior to implementation the company reported a turnover in the region of EUR 5.5M, which classifies it as a small enterprise under EU definitions. The organisation was purposively selected because it represented a typical SME profile: multiple concurrent projects, staff with multiple roles, low formal PM maturity, and a pressing managerial need to coordinate and control cross-functional project work [

26,

27].

3.3. Research Objectives

The empirical objectives of the study were:

- 1)

To describe the design and configuration choices of the PMS and the selected PMIS, showing how the information system models organisational objects (projects, tasks, resources, artefacts).

- 2)

To observe and document embedding processes and adoption dynamics over the first six months after the PMIS pilot rollout.

- 3)

To identify barriers and enablers to adoption, and to propose a set of concrete corrective or improvement actions to enhance routinization and value-capture.

3.4. Data Collection

A multi-method data collection protocol was implemented to gather rich, triangulated evidence from different organisational perspectives. The following techniques were used:

Table 1.

Data collection methods and purpose.

Table 1.

Data collection methods and purpose.

| Method |

Purpose |

When/Frequency |

| Unstructured interviews (executives, PMs) |

Capture strategic intentions, leadership commitment, and perceptions of PM maturity |

Pre-implementation and monthly follow-ups |

| Participant observation (PMO-led workshops, training) |

Monitor behaviours, tool usage and practical difficulties |

During rollout and first 3 months post-rollout |

| Focus groups (project teams / key users) |

Collect user-level feedback, pain-points, improvement ideas |

Immediately post-training and at 3- and 6-month marks |

| System logs and artifact inspection |

Objective evidence of usage patterns (projects created, timesheets submitted, cards moved) |

Continuous collection during pilot |

Key implementation actors included the newly established Project Management Office (PMO), a top-management sponsor, team leaders acting as project managers, and the regular project teams (many staff holding concurrent responsibilities). The PMO was managed by one of the researchers and had a formal mandate to define procedures, run training and steward adoption. This dual researcher–practitioner role enabled close access but required reflexive attention to potential observer effects [

25].

3.5. Implementation of the PMIS Pilot (Procedural Steps)

The implementation followed a staged pilot approach:

- 1)

Requirements elicitation: Elicit high-level PMS needs (portfolio visibility, lifecycle definition, resource management, timesheets, budgeting, agile support, document repository).

- 2)

Market review and tool selection: Evaluate candidate PMIS platforms for fit, configurability and interoperability; Triskell was selected because it best matched the articulated requirements and integration needs [

28].

- 3)

PMIS configuration: Configure core objects (Company → Commercial Procedures → Projects; Tasks and Cards as the planning/execution artefacts) and define the hybrid lifecycle that supports both Gantt-based planning and Kanban-style execution.

- 4)

Training and user onboarding: Conducted role-based hands-on sessions for PMO, project managers and selected key users; produced initial documentation and BoK (Body of Knowledge) drafts.

- 5)

Pilot operation and iterative refinement: Run pilot on a selected portfolio subset, collect feedback through observation and focus groups, and iteratively tune workflows and permissioning.

3.6. Data Analysis and Validation

Qualitative data from interviews, observations and focus groups were analysed using thematic coding. Coding combined inductive identification of emergent issues (e.g., resistance to change, overcommitment) with deductive mapping to established constructs such as PM maturity, sponsorship and tool usability [

29]. Triangulation was performed by cross-checking subjective reports against system metadata (e.g., timesheet submission rates, number of active Kanban cards) to validate or call into question stakeholder narratives.

3.7. Operationalising PMS “Embedment”

To provide a semi-quantitative measure that supports comparison across time and teams, we propose measuring a PMS

Embedment Index E that aggregates three core dimensions: organisational PM maturity (

M), training coverage and effectiveness (

T), and leadership sponsorship (

S). Each dimension is normalised to the interval

and combined with weights chosen by researchers or stakeholders:

Suggested operational definitions:

M (Maturity) — derived from checklist indicators (presence of standard artefacts, existence of portfolio planning, resource allocations) aggregated and normalised.

T (Training) — proportion of active users who completed role-based training and pass a short competency test.

S (Sponsorship) — measured from management behaviour indicators (e.g., portfolio reviews attended, use of PMIS dashboards, prioritisation stability).

Equation (

1) provides a pragmatic, traceable metric that complements qualitative interpretation and helps prioritise corrective actions.

3.8. Ethical Considerations and Reflexivity

Given the embedded nature of the research (the PMO was researcher-managed), care was taken to anonymise personal data and to report findings in ways that do not jeopardise participants. Interview and focus-group participants gave informed consent for observation notes and anonymised quotes to be used for research reporting. Reflexive logs were maintained by the PMO researchers to identify and mitigate influence on routine behaviours.

3.9. Limitations of the Methodological Approach

Single-case designs trade breadth for depth; results are context-rich but may not generalise statically across diverse SME populations. The researcher’s dual practitioner role improves access but introduces possible bias; triangulation with system metadata and multiple stakeholder views was used to reduce subjective distortion. Finally, the six-month observation window captures early embedding dynamics but may miss longer-horizon stabilisation and benefits realisation.

3.10. Summary

The methodology combined an action-oriented implementation (PMO-driven pilot) with a multi-modal evaluation protocol (interviews, observation, focus groups, system traces) and a mixed qualitative–semi-quantitative analysis approach (thematic coding complemented by the Embedment Index). This structure enabled the study to surface both technical configuration lessons and social adoption barriers, providing a robust basis for the subsequent implementation results and intervention proposals.

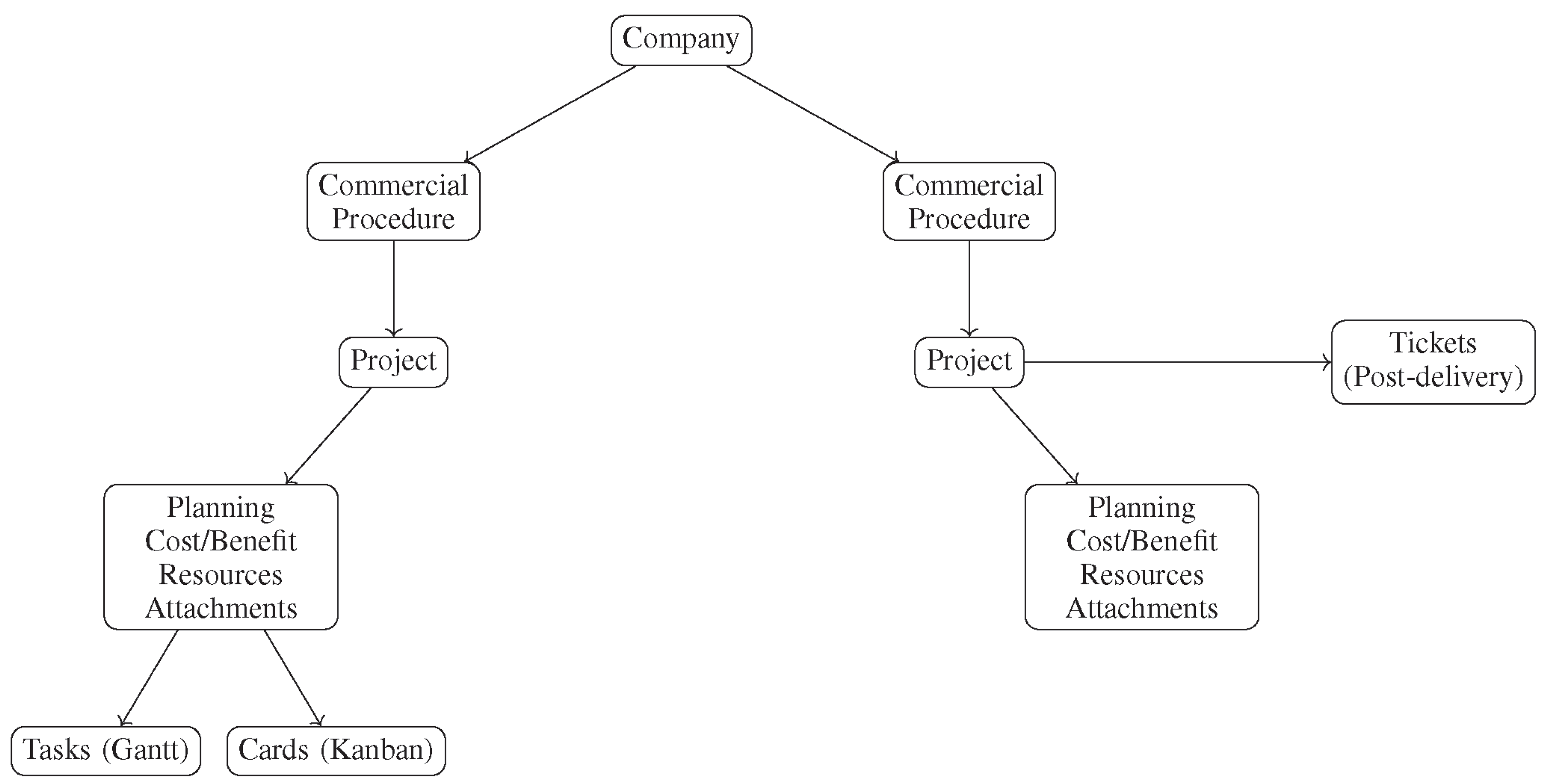

Figure 1.

PMIS architecture showing hierarchical relationships and planning artefacts.

Figure 1.

PMIS architecture showing hierarchical relationships and planning artefacts.

Recreated schematic of the PMIS data model: Company → Commercial Procedures → Projects, where each project exposes planning, financial and execution artefacts (Tasks and Cards) and may be linked to a Tickets object for after-delivery support.

4. Implementation

This section outlines the practical steps taken to deploy the Project Management System (PMS) within the selected Portuguese SME, as well as the configuration and integration of the chosen Project Management Information System (PMIS). The implementation was designed to address the organisation’s specific operational challenges, its low project management (PM) maturity, and the diversity of project types across business areas.

4.1. Establishment of the Project Management Office

A dedicated Project Management Office (PMO) was created as the central unit responsible for PMS definition, configuration, and continuous improvement. The PMO operated with a dual role: (i) as an internal consultancy and support hub for project managers, and (ii) as an active participant in project execution. Members of the PMO also held responsibilities in other project teams, reflecting the multi-role nature typical of SMEs [

26,

27].

4.2. Initial Situation and Rationale for Implementation

Prior to implementation, PM practices within the organisation were ad hoc and inconsistent. The following issues were identified:

Absence of formal project prioritisation and portfolio visibility.

Inefficient time management leading to schedule slippage.

Lack of cost tracking and resource allocation monitoring.

Disparate use of tools with no interoperability.

Minimal documentation of project processes.

Given the variety of project types—ranging from small IT deliverables to large, cross-functional initiatives—the PMS needed to be flexible enough to accommodate both structured (traditional) and adaptive (agile) approaches.

4.3. Requirements Definition

The PMO, in consultation with top management and team leaders, defined the following high-level functional requirements for the PMS:

- 1)

Portfolio-level visibility across all projects.

- 2)

Ability to group related projects into programs.

- 3)

Standardised project lifecycle stages.

- 4)

Integrated resource allocation and capacity planning.

- 5)

Task planning with both Gantt (traditional) and Kanban (agile) options.

- 6)

Budgeting and financial monitoring of costs and revenues.

- 7)

Work progress tracking and performance dashboards.

- 8)

Central repository for project documents and metadata.

- 9)

Timesheet entry and reporting.

- 10)

Configurable reporting for management oversight.

4.4. PMIS Selection and Configuration

Following a market review of candidate systems,

Triskell Software [

28] was selected for the pilot implementation. The choice was driven by:

High configuration flexibility to model the organisation’s hierarchy and workflows.

Native support for both traditional and agile planning modes.

Integration capabilities with existing organisational tools.

Scalability for potential future expansion.

The PMIS was configured with a root object Company, subdivided into Commercial Procedures, each of which contained one or more Projects. Each project object included:

Planning tools (dates, milestones, dependencies).

Cost and benefit tracking.

Resource assignment modules.

Document and attachment storage.

Task-level Gantt charts for high-level planning.

Card-based Kanban boards for agile execution.

The Tickets module, intended for post-delivery support, was configured but excluded from the pilot scope.

4.5. Hybrid Project Management Model

The PMS was deliberately configured to support a hybrid approach:

Tasks (Gantt): Used for creating high-level schedules and dependencies, providing estimates for duration and resource demand.

Cards (Kanban): Used for detailed execution management, enabling flexibility in responding to change.

This configuration allowed project managers to adopt purely traditional, purely agile, or mixed approaches based on project size, uncertainty, and stakeholder needs.

4.6. Pilot Rollout

The pilot implementation followed these stages:

- 1)

Selection of representative projects from different business areas.

- 2)

PMIS configuration and object modelling according to requirements.

- 3)

Training sessions for project managers, team leads, and selected key users.

- 4)

Initial use of the system for planning and execution in pilot projects.

- 5)

Collection of usage feedback and iterative refinement.

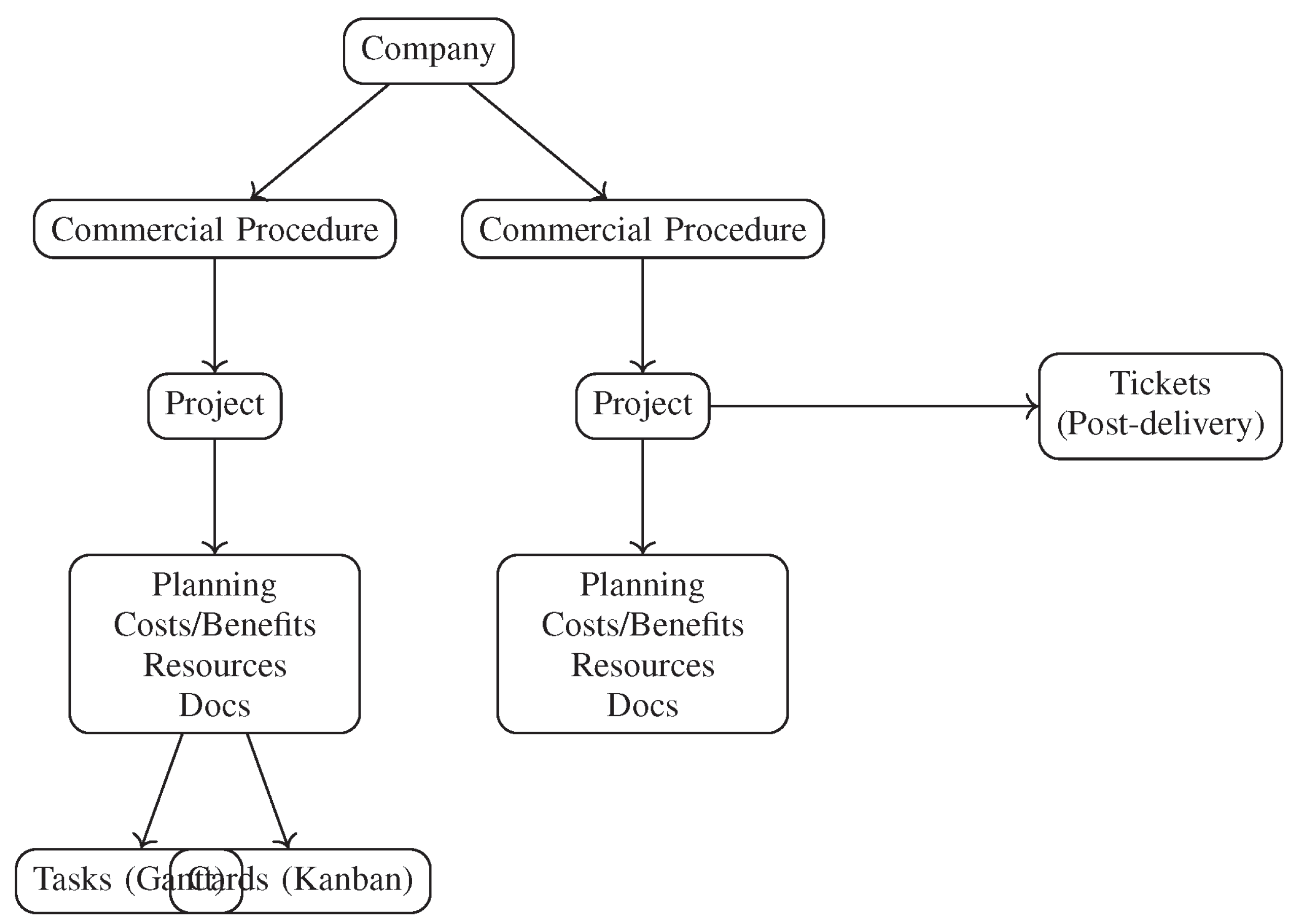

4.7. PMIS Architecture Representation

To visually represent the PMIS model, a compact schematic is provided in

Figure 2. This diagram fits IEEE column width while retaining the structural relationships defined during configuration.

4.8. Integration and Interoperability

Integration with other enterprise systems was considered a critical success factor. The PMIS was connected to the organisation’s document repository, allowing direct linking of artefacts to project records. API endpoints were evaluated for potential linkage with financial accounting tools, although this integration was deferred to a later phase.

4.9. Summary

The implementation approach balanced the need for structured planning and flexible execution. The hybrid model, enabled by the configured PMIS, provided adaptability across diverse project types. The pilot rollout offered a controlled environment for testing, feedback collection, and refinement before organisation-wide deployment.

5. Results

This section presents the outcomes of the PMS and PMIS pilot implementation, based on data collected through observations, interviews, focus groups, and system usage analytics. The findings are categorised into experienced difficulties, documented successes, and identified shortcomings. Additionally, proposed improvement measures are outlined to guide subsequent iterations.

5.1. Observed Difficulties

The rollout required significant changes to established work routines. As anticipated, several challenges emerged:

Resistance to change: Some team members displayed reluctance to adopt new processes and tools, particularly those unfamiliar with PM concepts.

Learning curve: Project managers and teams required substantial time to understand Gantt-based scheduling and cost tracking within the PMIS.

Tool limitations: The agile (Kanban) component of the PMIS was perceived as less responsive than expected, reducing enthusiasm for its adoption.

Leadership inconsistency: Senior managers frequently reprioritised projects without consulting the PMIS portfolio, undermining planning stability.

Resource overcommitment: Staff often participated in multiple projects simultaneously, limiting availability for proper PMS adoption.

5.2. Documented Successes

Despite the difficulties, the pilot generated several positive outcomes:

Portfolio visibility: Management gained the ability to view and monitor all projects in a single dashboard.

Cost and revenue forecasts: Projects could now be assessed for expected financial outcomes before completion.

Hybrid PM support: The system successfully enabled both traditional and agile planning modes.

Centralised information: All project documents and metadata were stored in a shared repository linked to each project.

Resource tracking: Allocation across multiple projects could be reviewed in real-time.

5.3. Failures and Shortcomings

Several implementation goals were not fully met:

PM practices were not embedded organisation-wide.

The Gantt chart was perceived as overly formal and complex.

Project cost definitions remained inconsistent across managers.

Timesheet completion rates were low.

Agile module lacked the expected adaptability.

PMO support to key users was insufficient due to workload constraints.

5.4. Summary of Outcomes

Table 2 consolidates the main successes and failures identified during the pilot phase.

5.5. Performance Evaluation Metric

To complement the

Embedment Index introduced in

Section 3, a simple

Implementation Effectiveness Score (IES) is proposed to aggregate success indicators into a normalised measure:

where:

indicates whether a specific success criterion was achieved (1) or not (0),

n is the total number of success criteria evaluated.

For example, using the five successes listed above (

), if four were fully achieved and one partially achieved (

for four criteria and

for one), the IES would be:

This score provides a quick, interpretable indicator of overall implementation effectiveness.

5.6. Interpretation

The results reveal that while technical configuration and initial rollout were successfully completed, the social and organisational embedding of PM practices lagged behind. Adoption was hindered by a mismatch between the system’s complexity and the organisation’s PM maturity, as well as insufficient leadership reinforcement. Nevertheless, the positive developments—particularly portfolio visibility and hybrid planning capability—provide a strong foundation for further improvement.

6. Discussion

The pilot implementation of the PMS and PMIS offers valuable insights into the interplay between technical configuration, organisational culture, and project management maturity within small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This section examines the results from

Section 5 in the context of existing literature and derives lessons for both practitioners and researchers.

6.1. Complexity Versus Maturity

One of the clearest findings is the mismatch between the complexity of the configured PMS and the organisation’s prevailing PM maturity level. While the selected PMIS offered extensive capabilities—including cost tracking, hybrid scheduling, and portfolio management—its effective use was hindered by limited prior exposure to formal PM tools among staff. This aligns with prior studies [

26,

27] that caution against transplanting enterprise-scale PM processes directly into SMEs without adaptation.

The experience supports the argument of [

30] and [

31] that PM systems for SMEs should be simpler and less bureaucratic in their initial form, gradually evolving as organisational maturity increases. In the studied case, an incremental deployment strategy—introducing core functions first and deferring advanced cost management—may have led to higher early adoption.

6.2. Role of Sponsorship and Leadership Behaviour

Consistent with findings in [

29,

32], the results highlight that visible and consistent leadership support is a critical enabler of PMS embedding. In this case, while top management initially sponsored the initiative, inconsistent behaviours—such as reprioritising projects outside the PMIS—signalled to teams that the system was not the authoritative source of truth. Such actions undermine adoption, as team members perceive reduced value in maintaining accurate records if decision-making bypasses the tool.

This reinforces the recommendation that top managers must not only authorise but actively participate in the use of the PMS, modelling the behaviours expected of the wider organisation.

6.3. Balancing Traditional and Agile Approaches

The hybrid PM model was well-received in principle, confirming earlier work by [

33,

34] that combining traditional planning discipline with agile execution flexibility can address the diverse needs of multi-project environments. However, the specific agile component within the PMIS was found to be insufficiently responsive, dampening enthusiasm for its use.

This finding suggests that, even within hybrid configurations, the usability and responsiveness of each component must be carefully validated against end-user expectations. A technically “complete” feature set is not enough if the user experience fails to support daily operational needs.

6.4. Embedding as an Organisational Routine

The concept of “embedding” PM practices—making them routine and integrated into organisational operations—was only partially achieved. As [

29] note, embedding requires alignment between PM initiatives and existing management practices, as well as active reinforcement through training, monitoring, and incentives. In this case, the lack of systematic follow-up from the PMO, due in part to resource constraints, slowed progress toward routinisation.

One practical lesson is the need for dedicated capacity within the PMO to provide hands-on support during the critical post-rollout period. Embedding is not a one-off event but an ongoing process that may take months or even years.

6.5. Quantitative and Qualitative Insights

The use of semi-quantitative measures such as the

Embedment Index (Eq.

1) and

Implementation Effectiveness Score (Eq.

2) proved valuable for complementing qualitative observations. While these scores do not replace in-depth analysis, they provide a concise summary of progress and can be tracked over time to evaluate improvement efforts.

Combining quantitative indicators with rich qualitative data supports a more nuanced understanding of adoption dynamics, particularly in SMEs where small changes in leadership behaviour or team composition can have outsized effects.

6.6. Implications for SME PMIS Implementations

From the analysis, several implications emerge:

Start small, grow incrementally: Implement core, high-value features first and expand functionality as user competence increases.

Prioritise leadership engagement: Secure visible, consistent involvement from senior managers in the daily use of the PMS.

Invest in training and follow-up: Treat user education and ongoing support as continuous, not one-off, activities.

Validate usability early: Conduct usability testing on both traditional and agile components before full rollout.

Align with organisational rhythm: Integrate PMS processes into existing management cycles and decision forums.

6.7. Summary

The discussion underscores that successful PMS implementation in SMEs is not solely a technical challenge but a socio-technical one, requiring alignment between tool capabilities, organisational maturity, and leadership practices. The studied case reinforces the literature in advocating incremental, user-centred deployment strategies, strong leadership modelling, and sustained PMO engagement to ensure lasting adoption.

7. Conclusion

This study has examined the design, implementation, and initial evaluation of a Project Management System (PMS) supported by a Project Management Information System (PMIS) within a Portuguese small-to-medium-sized enterprise (SME). The work contributes both a practical case narrative and an analytical framework for understanding adoption challenges in low-maturity PM environments.

The findings emphasise that successful PMS deployment in SMEs requires more than technical configuration; it demands a close alignment between system complexity, organisational project management maturity, and leadership engagement. In this case, while the PMIS delivered immediate benefits such as portfolio visibility, hybrid planning capabilities, and centralised project data, adoption was constrained by:

Limited prior exposure to formal PM practices.

Insufficient and inconsistent leadership modelling of PMS use.

Perceived complexity of certain tools (e.g., Gantt chart cost tracking).

Usability limitations in agile (Kanban) components.

The hybrid PM approach proved conceptually sound, enabling adaptation to a variety of project types and uncertainty levels, consistent with earlier research [

33,

34]. However, the embedding of PM practices as an organisational routine was incomplete, reflecting the need for incremental rollout strategies and sustained PMO support, as highlighted in [

29].

In summary, this case reinforces existing literature on the socio-technical nature of PMS adoption, demonstrating that tool deployment must be matched by cultural readiness, leadership behaviours, and operational capacity for ongoing support.

8. Future Work

Building on the lessons learned from this pilot implementation, several avenues for further work are proposed:

8.1. Refinement of the PMS Design

Future iterations should adopt a phased approach, introducing a minimal set of high-impact features initially (e.g., portfolio tracking, basic scheduling) and deferring more complex modules (e.g., cost management, advanced reporting) until users are proficient with foundational functions.

8.2. Enhanced Agile Module

The limitations observed in the current agile (Kanban) component suggest the need to either reconfigure it for improved responsiveness or integrate a specialised agile tool that can interoperate with the PMIS. Usability testing with end users should be performed prior to adoption.

8.3. Strengthened Leadership Engagement

To achieve higher adoption, leadership must actively participate in PMS-driven processes, regularly review portfolio data, and avoid bypassing the system when making priority changes. Developing leadership KPIs linked to PMS usage could incentivise consistent engagement.

8.4. Longitudinal Adoption Study

A follow-up longitudinal study, spanning 12–18 months, would provide a richer understanding of how PMS adoption evolves over time and how organisational learning impacts PM maturity. Tracking quantitative measures such as the Embedment Index (Eq.

1) and Implementation Effectiveness Score (Eq.

2) would allow for measurable progress evaluation.

8.5. Cross-Case Comparative Analysis

Conducting similar PMS–PMIS implementation studies across different SMEs and industry contexts could help identify patterns of success and failure, enabling the development of tailored best-practice frameworks for SME environments.

8.6. Integration with Enterprise Systems

Exploring deeper integration between the PMIS and other enterprise systems (e.g., ERP, CRM, accounting) could further streamline processes and reduce data duplication, provided such integration aligns with organisational capacity and needs.

8.7. Body of Knowledge (BoK) Development

Codifying the organisation’s PM processes, templates, and guidelines into a lightweight Body of Knowledge could serve as a training and reference resource, aiding consistency and reducing dependency on informal knowledge transfer.

8.8. Final Remarks

By addressing these future work areas, SMEs can increase the likelihood of achieving sustainable PMS adoption, moving from isolated tool usage to an embedded, organisation-wide project management culture. The present case offers a foundation for such progression, demonstrating both the opportunities and the challenges of PMS implementation in resource-constrained, multi-project environments.

References

- Dinsmore, P.C.; Cabanis-Brewin, J. The AMA Handbook of Project Management, 4th ed.; Amacom: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide), 6th ed.; Project Management Institute: Pennsylvania, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, A.; Ledwith, A. Project management tools and techniques in high-technology SMEs. Proceedings of the Management Research News 2007, Vol. 30, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. User Guide to the SME Definition. 2015. Available online: https://publications.europa.eu/s/lkkY.

- Borštnar, M.K.; Pucihar, A. Impacts of the Implementation of a Project Management Information System – a Case Study of a Small R&D Company. Organizacija 2014, 47, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.; Ledwith, A.; Kelly, J. Project management in small to medium-sized enterprises: Matching processes to the nature of the firm. International Journal of Project Management 2010, 28, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spundak, M. Mixed Agile/Traditional Project Management Methodology – Reality or Illusion? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2014, 119, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayata, T.; Han, J. A hybrid model for IT project with Scrum; 2011; pp. 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, P.; Mäntylä, M.; Oivo, M.; Lwakatare, L.E.; Seppänen, P.; Kuvaja, P. Advances in Using Agile and Lean Processes for Software Development. Advances in Computers 2018. [Google Scholar]

- West, D.; Gilpin, M.; Grant, T.; Anderson, A. Water-scrum-fall is the reality of agile for most organizations today. Forrester Research 2011, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Kostalova, J.; Tetrevova, L.; Svedik, J. Support of Project Management Methods by Project Management Information System. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2015, 210, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, L.; Bergeron, F. Project management information systems: An empirical study of their impact on project managers and project success. International Journal of Project Management 2008, 26, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobadian, A.; Gallear, D. TQM and organization size. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 1997, 17, 121–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.S.; Forrest, D.; Dinetta, T.; Wolfe, B.; Lambert, D.C. Enhance PMBOK by Comparing it with P2M, ICB, PRINCE2, APM and Scrum Project Management Standards. PM World Journal 2012, XIV, 78. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, J.; Adler, D. Skills that improve profitability: The relationship between project management, IT skills, and small to medium enterprise profitability. International Journal of Project Management 2016, 34, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.; Ledwith, A. Project Management in Small to Medium-Sized Enterprises: Fitting the Practices to the Needs of the Firm to Deliver Benefit. Journal of Small Business Management 2018, 56, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tereso, A.; Ribeiro, P.; Fernandes, G.; Loureiro, I.; Ferreira, M. Project Management Practices in Private Organizations. Project Management Journal 2019, 50, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.; Moreira, S.; Araújo, M.; Pinto, E.B.; Machado, R.J. Project management practices for collaborative university-industry R&D: A hybrid approach. Procedia Computer Science 2018, 138, 805–814. [Google Scholar]

- Braglia, M.; Frosolini, M. An integrated approach to implement Project Management Information Systems within the Extended Enterprise. International Journal of Project Management 2014, 32, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.; Ward, S.; Araújo, M. Improving and embedding project management practice in organisations - A qualitative study. International Journal of Project Management 2015, 33, 1052–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.; Ward, S.; Araújo, M. Developing a Framework for Embedding Useful Project Management Improvement Initiatives in Organizations. Project Management Journal 2014, 45, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Tereso, A.; Fernandes, G.; Pinto, J.Â. OPM3® Portugal Project: Analysis of Preliminary Results. Procedia Technology 2014, 16, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke-Davies, T.J.; Crawford, L.H.; Lechler, T.G. Project Management Systems: Moving Project Management from an Operational to a Strategic Discipline. Project Management Journal 2009, 40, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A.; Bristow, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Edinburgh, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R.; Ledwith, A.; Kelly, J. Project management in small to medium-sized enterprises: Matching processes to the nature of the firm. International Journal of Project Management 2010, 28, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borštnar, M.K.; Pucihar, A. Impacts of the Implementation of a Project Management Information System – A Case Study of a Small R&D Company. Organizacija 2014, 47, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triskell Software. 2019. Available online: https://www.triskellsoftware.com/.

- Fernandes, G.; Ward, S.; Araújo, M. Improving and embedding project management practice in organisations: A qualitative study. International Journal of Project Management 2015, 33, 1052–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.; Ledwith, A. Project management tools and techniques in high-technology SMEs. Management Research News 2007, 30, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, J.; Adler, D. Skills that improve profitability: The relationship between project management, IT skills, and small to medium enterprise profitability. International Journal of Project Management 2016, 34, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke-Davies, T.J.; Crawford, L.H.; Lechler, T.G. Project Management Systems: Moving Project Management from an Operational to a Strategic Discipline. Project Management Journal 2009, 40, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayata, T.; Han, J. A hybrid model for IT project with Scrum. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of 2011 IEEE International Conference on Service Operations, Logistics and Informatics. IEEE, 2011; pp. 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- West, D.; Gilpin, M.; Grant, T.; Anderson, A. Water-Scrum-Fall is the reality of agile for most organizations today. Technical Report 26, Forrester Research, 2011. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).