1. Introduction

The Boltzmann equation is a cornerstone of nonequilibrium statistical mechanics, allowing for the dynamical evolution of a distribution function

, which describes how a system of particles evolves through collisions by quantifying the particles’ positions and velocities [

1,

2,

3]. This equation has found applicability in many systems, including those at relativistic energies, an extension that was made possible by incorporating relativity. Thus, the Boltzmann equation is now applied in astrophysics, in studies of the early universe, and in investigations of the Quark-Gluon Plasma (QGP) [

4,

5,

6]. Another very common application of the relativistic Boltzmann equation is in the area of electromagnetic plasmas [

7].

The Fokker-Planck Equation (FPE) can be derived from the Boltzmann equation through a second-order expansion of the probability density, resulting in a second-order differential equation that describes the statistical behaviour of the system through transport coefficients: the drag (or drift) coefficient, associated with external forces, and the diffusion coefficient, associated with stochastic collisions among the many particles in the system [

8,

9]. This equation must be covariant under Lorentz transformations to be applied to relativistic systems [

10,

11]. Among its applications is plasma physics, allowing the analysis of the dynamics of charged particles, as well as astrophysics and cosmology, where the evolution of nebulae is studied. All these systems are subject to the combined effects of drag and relativistic diffusion [

12,

13]. With such an extension, the transport coefficients must be reinterpreted in terms of the exchange of four-momentum during particle interactions.

The FPE, however, is restricted to a particular class of systems, namely those for which the collision term of the Boltzmann equation has a correlation functional that is bilinear in the interacting particle distributions. This assumption is useful and valid for interactions that are local, uncorrelated, and follow a Markovian sequence. However, there is increasing interest in systems that fall outside this class and are instead described by nonlinear Fokker-Planck equations. Within this family of nonlinear equations, a particular class is of broad applicability, namely the Plastino-Plastino Equation (PPE) [

14], which was proposed in connection with systems following Tsallis statistics [

14,

15,

16,

17].

Tsallis statistics has been applied in different fields of physics and beyond, yielding numerous studies, especially in high-energy physics. The emergence of Tsallis statistics in quantum field theory can be traced to the renormalisation properties of these theories and to self-energy interactions. Together, these properties provide the necessary conditions for the formation of thermofractals [

18], and their mathematical tools have uncovered a deep relationship between the Tsallis index

q and field-theoretical parameters, which in the case of QCD are the number of colours and flavours. This connection has shown that

q is a structural parameter within quantum field theory, rather than merely a fitting parameter.

The description of the dynamics of heavy quarks in the QGP within this statistical framework, particularly through the PPE [

14], is of great importance. This nonlinear dynamics, within nonextensive statistics, provides a means to describe the evolution of complex and random systems and has proven relevant in research across different areas of physics [

17]. Recently, the PPE was used to investigate the dynamical origin of the nuclear modification factor in high-energy nuclear collisions [

19] by employing a nonrelativistic version of the equation. Although relativistic effects may be limited in some cases, it is important to extend the PPE so that it behaves covariantly under Lorentz transformations.

In this work, a derivation of the PPE is carried out by incorporating special relativity, leading to the Relativistic Plastino-Plastino Equation (RPPE) within the framework of Tsallis

q-statistics. The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 derives the relativistic Boltzmann equation for a particle collision system. In addition, the relativistic Fokker-Planck equation is deduced from the relativistic Boltzmann equation, and in

Section 4, the RPPE is derived from the RFPE using fractal derivatives, ultimately yielding a relativistic equation expressed in terms of the velocity variable. Final remarks are presented in

Section 5.

2. Relativistic Boltzmann and Fokker-Planck Equations

A particle of rest mass

m is described by the space-time coordinates

and by the four-momentum

, where

is given by

. The one-particle distribution function, defined in terms of space-time and momentum coordinates as

, is such that

where

t is the instant at which the number of particles in a volume element

around

and with momentum within

around

is measured [

1]. The number of particles in the volume is a scalar invariant, since all observers count the same number of particles. Therefore, the distribution function

is itself a scalar invariant [

1].

Defining the phase-space volume at time

t as

, the number of particles in this volume is

At time

, the number of particles becomes

Due to particle collisions,

, and the variation is

where the increments in the position and in the momentum are given as,

The relationship between

and

is given by,

with

J denoting the Jacobian of the transformation,

The increments in position and momentum are

and

, where

is the external force and

is the particle velocity [

1]. The Jacobian relating

and

is

with

.

Expanding

to first order in

yields

Combining Eqs. (

7) and (

8), and retaining linear terms, one finds

Since

and the proper time

are scalar invariants,

is a scalar invariant as well as the proper time

, hence

is a scalar invariant [

1]. Where

is a scalar invariant, and as a consequence the expression multiplying, must have the same property. We first consider the term

in which

and multiplying and dividing the first term by

, we have that

Since

f is a scalar invariant,

is a 4-vector, and the scalar product

is a scalar invariant. We consider the Minkowski force

defined by

that satisfies,

and the relationship,

If we consider

as an independent variable and make use of the chain rule:

We can write

by introducing Eqs. (

16) and (

15) as follows,

which is a scalar invariant [

1].

Substituting Eqs. (

13) and (

17) into Eq. (11) yields

To determine

, we decompose it in two terms

where

corresponds to the particles that leave the volume

, whereas

corresponds to those particles that enter in the same volume. Further, we assume the following:

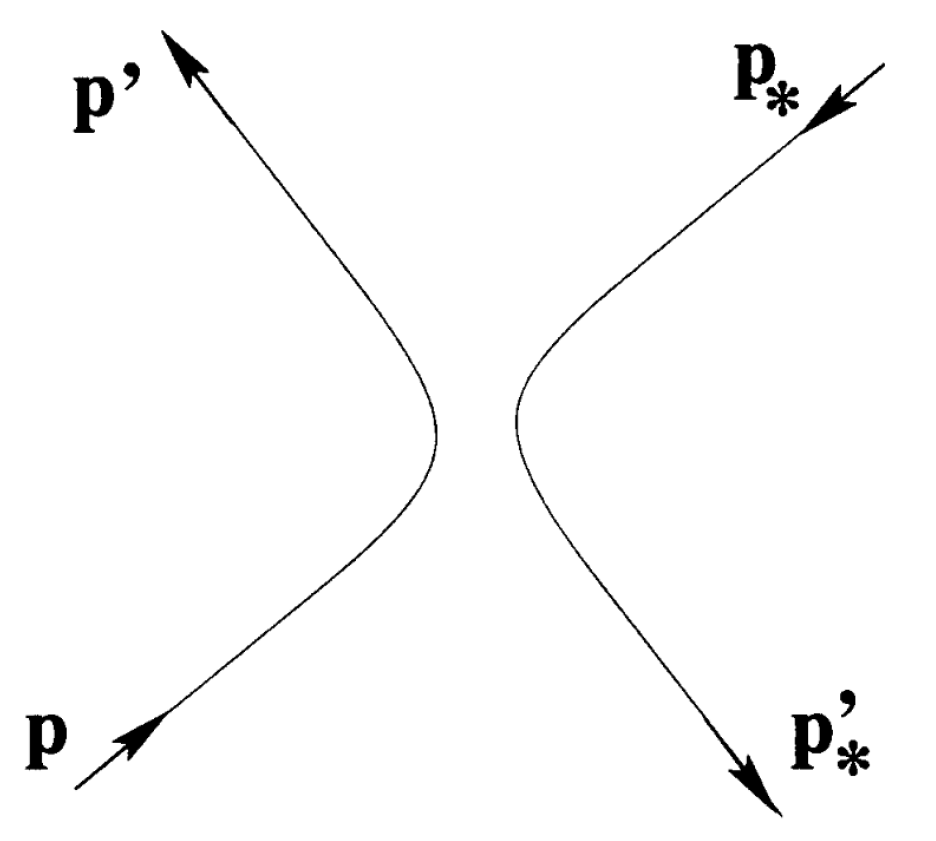

- a)

Only collisions between pairs of particles are taken into account, i. e. only binary collisions are considered (See

Figure 1) [

1].

- b)

If

and

denote the momenta of two particles before collision they are not correlated. This will be applied to the momenta

of the particle that we are following, and

of its collision partner, as well as to two momenta

and

, possessed by two particles before a collision that will transform them into particles with momenta

and

after collision [

1].

- c)

The one-particle distribution function

does not vary very much over a time interval which is larger than the duration of a collision but smaller the time between collisions. The same applies to the change of

over a distance of the order of the interaction range [

1].

We consider a collision between two beams of particles with velocities

and

. The particle number densities of these two beams in their own frames are denoted by

and

. The

d in front of

n and

indicates that these number densities are infinitesimal because they refer to volume elements

and

of momentum space (

and

) [

1].

The total number of particles around

is

. The total number of particles that collide in the volume

will be

, where

is the relative velocity and

is a proper volume [

1].

The particles with density

in the volume

are differently scattered by their partners in the collision through different angles. Each collision will occur in a plane with some scattering angle

; another angle is needed to single out the plane and two infinitesimal neighborhoods of the two angles together single out a solid angle element

[

1]. The volume element

can be written in terms of the so-called collision cylinder of base

and height

.

is identified with the differential of the proper time, because of the choice of the reference frame. The factor

has clearly the dimensions of an area and is called the differential cross-section of the scattering process corresponding to the relative speed

and the scattering angle

. In another reference system where

,

,

,

and

are scalar invariants [

1].

The total number of collisions will be given then by the product of the particle numbers corresponding to the velocities

and

(See

Figure 2):

where we have rewritten the volume element

in terms of the collision cylinder. Let us consider the product of the particle number densities in a system where

:

We have that the total number of collisions given by Eq. (

20) is

In which another form of relative speed is used, known as M

ller relative velocity,

then,

where we have introduced M

ller´s relative velocity

[

1]. Now the total number of particles that leave the volume

is obtained by integrating it over all momenta

and over all solid angle

, yielding

This is frequently called the loss term because it describes the loss of particles in the volume

in phase space, due to collisions. We consider a collision between two beams of particles with velocities

and

and we write the total number of particles that leave the volume element

as,

which is called the gain term since it describes the gain of particles in the volume element

. For relativistic particles we have that

[

1]. Therefore, through Liouville’s theorem, it is obtained that the volume in phase space does not change over time. Here, we have that

since

is an invariant, we have that

From Eq. (

19), and introducing in Eq. (

18), we have that

where

so,

we have denoted by only one symbol the integrals over

and

. If we denote by

F the invariant flux

then,

which is the final form of the relativistic Boltzmann equation for a single non-degenerate relativistic gas [

1].

3. Relativistic Fokker-Planck Equation

Under the assumption of grazing collisions that could take place in long-range interactions, only small changes in the momentum of the particles occur due to small deflections in the scattering angle. Then the collision term of the Boltzmann equation, denoted by

[

7]. The total

and the relative

four-momentum, defined by

For these quantities the following relationships hold are,

The differences between the post- and pre-collision four-momentum,

Hence for small changes of the momentum of the particles at collision one can expand the one-particle distribution function in Taylor series, which up to the second-order terms,

with a similar expression for

. Now it is possible to approximate the collision term of the Boltzmann equation as [

7],

then, introducing Eq. (

37), with the help of the relationship,

then,

In order to transform the integral, the center-of-mass system is chosen where the spatial components of the total four-momentum vanish, i.e.,

and

. Now the element of solid angle can be written as

, where

and

are polar angles of

with respect to

and such that

represents the scattering angle [

7]. Further, without loss of generality,

is chosen in the direction of the three axis, so that one can write

and

as

by using the above representations, the integrals in the variable

, yielding

where

and

. Note that the differential cross-section is a function of

. Then,

where

then,

and

are the spatial components of the metric tensor

[

7]. By differentiating with respect to

, we have

here we have used Eq. (

45), therefore,

therefore,

where

and using Eq. (

47), we have that

The first term on the right-hand side of the above equation vanishes, since the hypothesis of grazing collisions is used and it is possible to convert; thanks to the divergence theorem; the volume integral in the momentum space into an integral at an infinitely far surface where the distribution functions tend to zero [

7]. By invoking the divergence theorem again,

where the spatial components of the coefficient of dynamic friction

and the diffusion coefficient

are given by

In this system

, and one can include the zero components

Hence the Relativistic Boltzmann Equation reduces to the Relativistic Fokker-Planck Equation, namely [

7]

5. Conclusions

This work provides the first demonstration of the Relativistic Plastino-Plastino Equation derived from the Relativistic Boltzmann Equation. Initially, the relativistic version of the Fokker-Planck equation is obtained, and it is then shown that this equation is limited to a specific form of correlators in the collision term. As a consequence, it cannot be applied to systems that do not follow a Markovian sequence of collisions, such as systems exhibiting memory effects or nonlocal correlations.

Motivated by recent results, this work identifies the Plastino-Plastino Equation as the appropriate framework for describing systems with such characteristics, including quark-gluon plasma, hadronic systems, and electromagnetic plasmas. Following the methodology of previous studies, the Relativistic Plastino-Plastino Equation is derived from the relativistic Fokker-Planck equation by exploiting the known connections between the fractal Fokker-Planck equation and the Plastino-Plastino Equation. These connections rely on the recently established relationship between fractal derivatives and q-deformed derivatives.

The relativistic version of the Plastino-Plastino Equation opens new possibilities for investigating the dynamical evolution of systems such as solar plasmas, Tokamak plasmas, quark-gluon plasma, and neutron star cores. The use of the relativistic formulation enables more precise analyses and a more accurate determination of the key physical parameters governing these systems.