1. Introduction

Cadherin-19 (CDH19) is a neural crest–specific adhesion molecule that plays a central role in maintaining brain homeostasis [

1,

2]. CDH19 belongs to the classical type II cadherin family and comprises five extracellular cadherin repeats (EC1–EC5), a single-pass transmembrane region, and a cytoplasmic tail [

3]. The extracellular domain of CDH19 mediates calcium-dependent homophilic interactions at adherens junctions [

4]. Its cytoplasmic domain associates with α-catenin, β-catenin, and p120-catenin, which link CDH19 to the actin cytoskeleton [

5,

6].

The human CDH19 gene was cloned in 2000 based on its sequence similarity to CDH7 [

7]. Expressed sequence tags for CDH19 were isolated from melanocyte cDNA libraries, suggesting that CDH19 expression may be restricted to neural crest-derived cells [

7]. Supporting this observation, rat CDH19 was primarily expressed in nerve ganglia and Schwann cells during embryonic development. Moreover, CDH19 expression overlapped with neural crest markers such as AP-2 and Sox10 [

2]. In Sox10-knockout mouse embryos, neural crest cells exhibited delayed migration to the distal hindgut along with a simultaneous downregulation of CDH19 [

1]. Furthermore, Sox10 was found to bind to the CDH19 promoter, indicating that CDH19 is a direct target of Sox10 during early neural crest cell migration by forming CDH19-catenins-cytoskeleton complexes [

1]. Through these functions, CDH19 is crucial for the development of neural crest cells, providing insights into the pathogenesis of nervous system developmental defects [

8,

9].

Melanoma is a type of skin cancer caused by the oncogenic transformation of melanocytes, which are pigment-producing skin cells derived from the neural crest [

10,

11]. Estimated new cases of melanoma in 2025 are more than 100,000 in the US [

12], and approximately 20% of patients have advanced disease [American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stages: IIIA~IIID] at the time of diagnosis [

13]. Although primary melanoma can be cured by surgery, and immune checkpoint inhibitors are the standard care in patients with advanced-stage melanoma [

14,

15], melanoma is the leading cause of death from skin disease in the US, responsible for 8,430 estimated deaths in 2025 [

12]. A single-cell multi-omics analysis of human melanoma revealed that melanoma cells were grouped into seven subtypes, which include a CDH19-high subtype, which was suggested to be more resistant to NK and T cell-mediated immunity [

16].

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that detect CDH19 by Western blotting or immunohistochemistry (IHC) have been developed for various applications. However, no mAb is available for flow cytometry. Using the Cell-Based Immunization and Screening (CBIS) method, anti-E-Cadherin/CDH1 [

17] and anti-M-Cadherin/CDH15 [

18] mAbs for flow cytometry, Western blotting, and IHC were developed by our laboratory. The CBIS method includes high-throughput flow cytometry–based screening. Therefore, mAbs obtained by the CBIS method generally recognize conformational epitopes, enabling their use in flow cytometry. Some of the mAbs are suitable for Western blotting and IHC. In this study, we employed the CBIS method to develop highly versatile anti-CDH19 mAbs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1, mouse myeloma P3X63Ag8U.1 (P3U1), and human glioblastoma (GBM) LN229 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA).

2.2. Plasmid Construction and Establishment of Stable Transfectants

Genes encoding human

CDH19 (NM_021153) were purchased from OriGene Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, MD, USA). The

CDH19 cDNA without the pro-peptide was subcloned into the pCAG-Ble vector with an N-terminal PA16 tag [

19]. Additionally, the

CDH19 cDNA with an N-terminal MAP16 tag [

20] was constructed. These plasmids were transfected into CHO-K1 or LN229 cells, and stable transfectants were sorted using anti-PA16 tag mAb (clone NZ-1) [

19] or anti-MAP16 tag mAb (clone PMab-1) [

20] using the Neon transfection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Finally, PA16-CDH19-overexpressed CHO-K1 (CHO/CDH19) and MAP16-CDH19-overexpressed LN229 (LN229/CDH19) were established.

We previously established other CDH-overexpressed stable transfectants [

21]. To confirm the expression of CDHs in these transfectants, 1 μg/mL of an anti-CDH1 mAb (clone 67A4), 1 μg/mL of an anti-CDH3 mAb (clone MM0508-9V11), or 0.1 μg/mL of an anti-PA16 tag mAb, NZ-33 [

22] were used.

2.3. Production of Hybridomas

Female BALB/cAJcl mice (CLEA Japan, Tokyo, Japan) were intraperitoneally immunized with LN229/CDH19 cells (1 × 10

8 cells/injection) mixed with 2% Alhydrogel adjuvant (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA). Following three additional weekly immunizations (1.0 × 10

8 cells/injection), a booster dose (1 × 10

8 cells/injection) was administered two days before spleen excision. Hybridomas were produced as previously described [

18].

2.4. Flow Cytometry

A total of 1 × 10

5 cells harvested with 1 mM EDTA were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; blocking buffer) and incubated with mAbs for 30 minutes at 4°C. Flow cytometric data were acquired as described previously [

17].

2.5. Determination of Dissociation Constant Values Using Flow Cytometry

LN229/CDH19 cells were treated with serially diluted Ca

19Mab-8. The dissociation constant (

KD) values were calculated s described previously [

17].

2.6. Western Blotting

Western blotting was conducted using 1 μg/mL Ca

19Mab-8 or 1 μg/mL of an anti-isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mAb (clone RcMab-1) as described previously [

18].

2.7. IHC Using Cell Blocks

The formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) cell sections were prepared as described previously [

18].They are stained with 0.2 μg/mL of Ca

19Mab-8 or 0.01 μg/mL of NZ-33 using the

BenchMark ULTRA

PLUS with the ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit

(Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA

).

3. Results

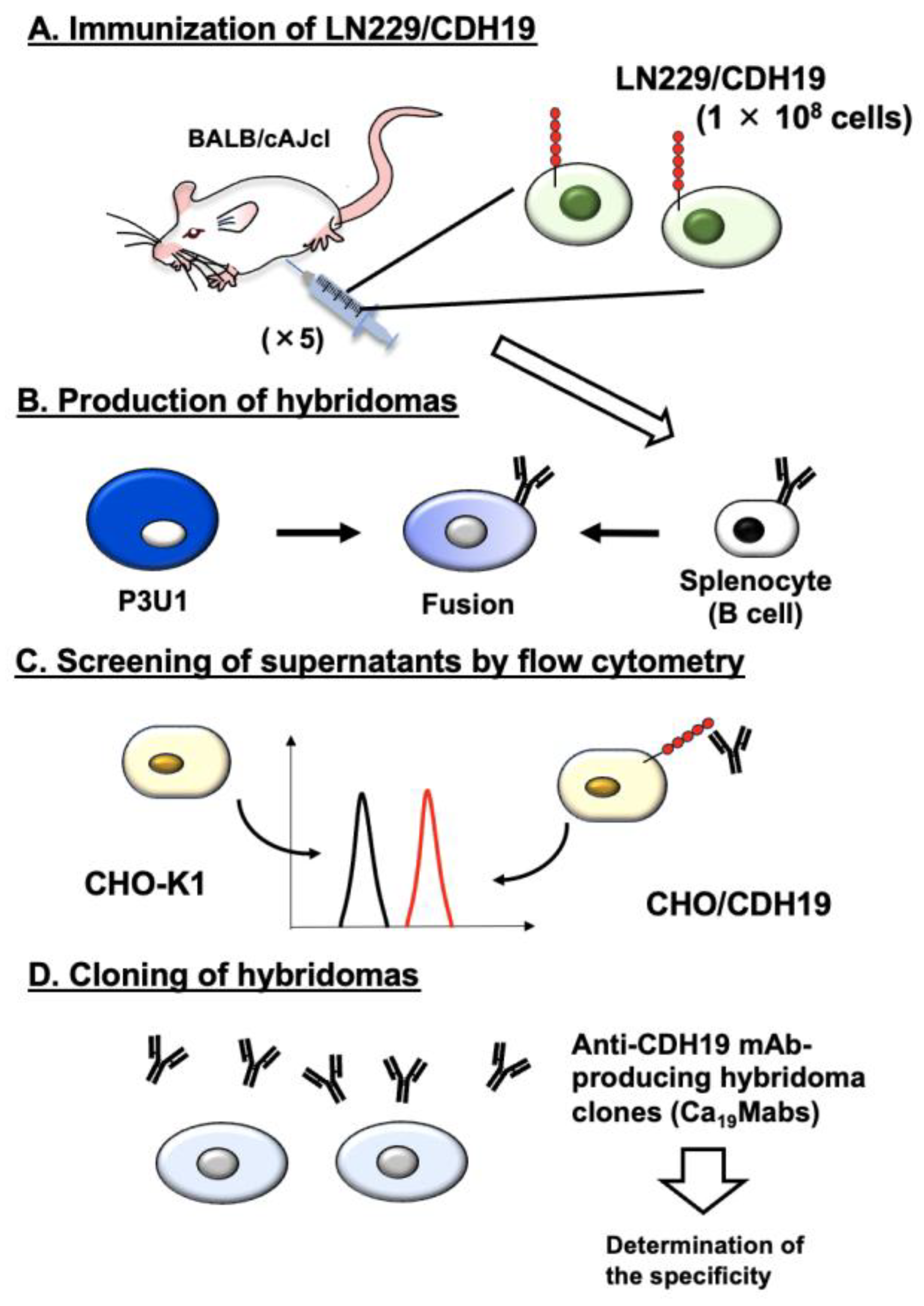

3.1. Anti-CDH19 mAb Development by the CBIS Method

As described in the Materials and Methods, an immunogen, LN229/CDH19, was prepared. LN229/CDH19 (1 × 10

8 cells/mouse) was immunized five times into two BALB/cAJcl mice (

Figure 1A). Subsequently, hybridomas were generated by fusing splenocytes with myeloma P3U1 (

Figure 1B). The hybridoma supernatants were screened to identify those positive for CHO/CDH19 and negative for CHO-K1 (

Figure 1C). As a result, 43 positive wells out of 958 (4.5%) were found. Limiting dilution was then performed to clone hybridomas producing anti-CDH19 mAb (

Figure 1D). Ultimately, 12 clones were established (

http://www.med-tohoku-antibody.com/topics/001_paper_antibody_PDIS.htm#CDH19+), and the purified mAbs (IgG

1 isotype) were prepared.

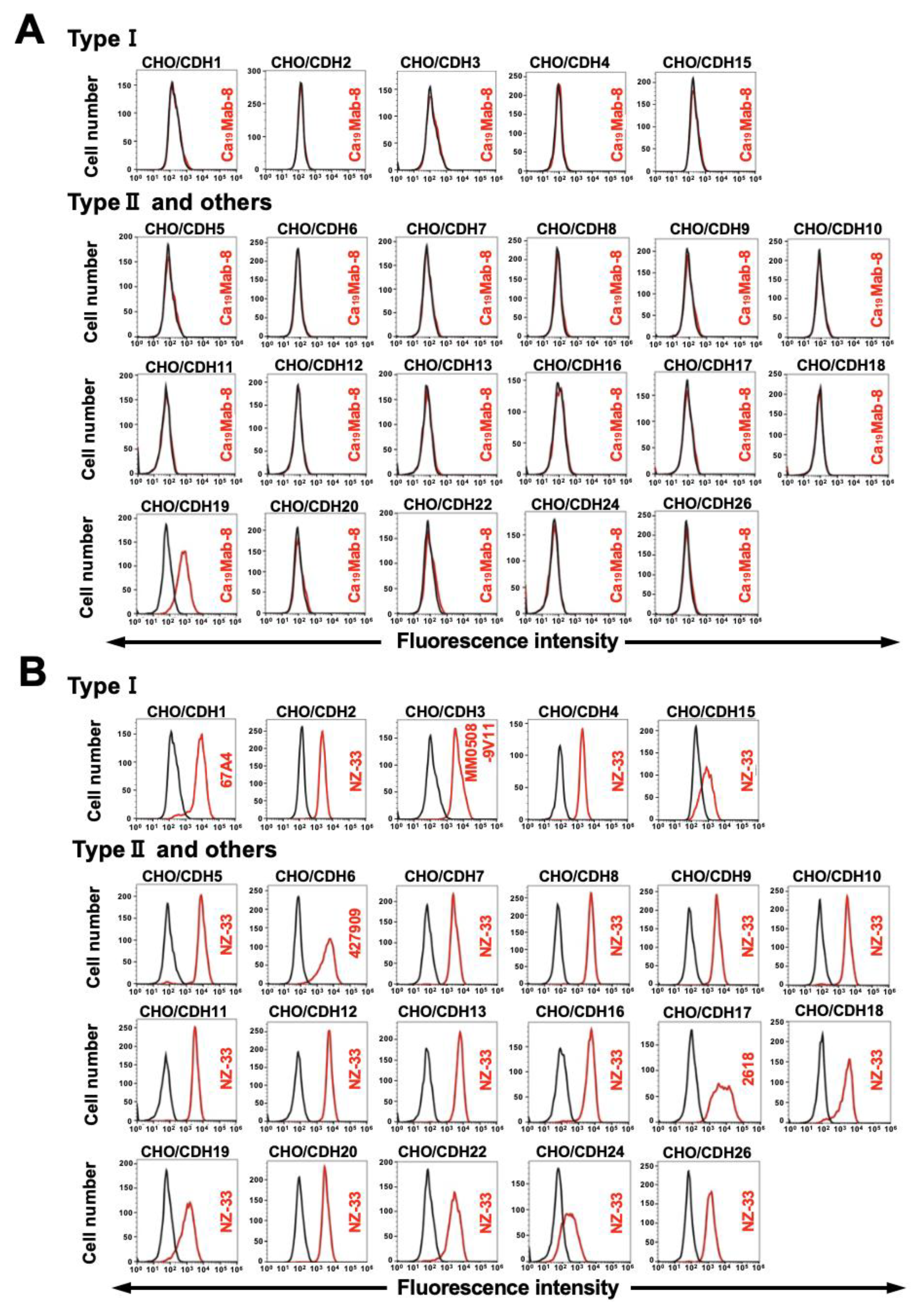

3.2. Determination of the Specificity of Ca19Mab-8 Using CDHs-Overexpressed CHO-K1

We previously established CHO-K1 cells, which overexpressed type I CDHs (CDH1, CDH2, CDH3, CDH4, and CDH15) [

17,

18], type II CDHs (CDH5, CDH6, CDH7, CDH8, CDH9, CDH10, CDH11, CDH12, CDH18, CDH19, CDH20, CDH22, and CDH24), 7D CDHs (CDH16 and CDH17), a truncated CDH (CDH13), and an atypical CDH (CDH26) [

21]. Therefore, the specificity of Ca

19Mabs to those CDHs was determined. As shown in

Figure 2A, Ca

19Mab-8 reacted with CHO/CDH19 but did not react with other CDHs-overexpressed in CHO-K1. The cell surface expression of CDHs was confirmed in

Figure 2B. In contrast, other Ca

19Mabs showed cross-reactivity against other type II CDHs (

Supplementary Table S1). These results indicate that Ca

19Mab-8 is a specific mAb to CDH19 among those CDHs.

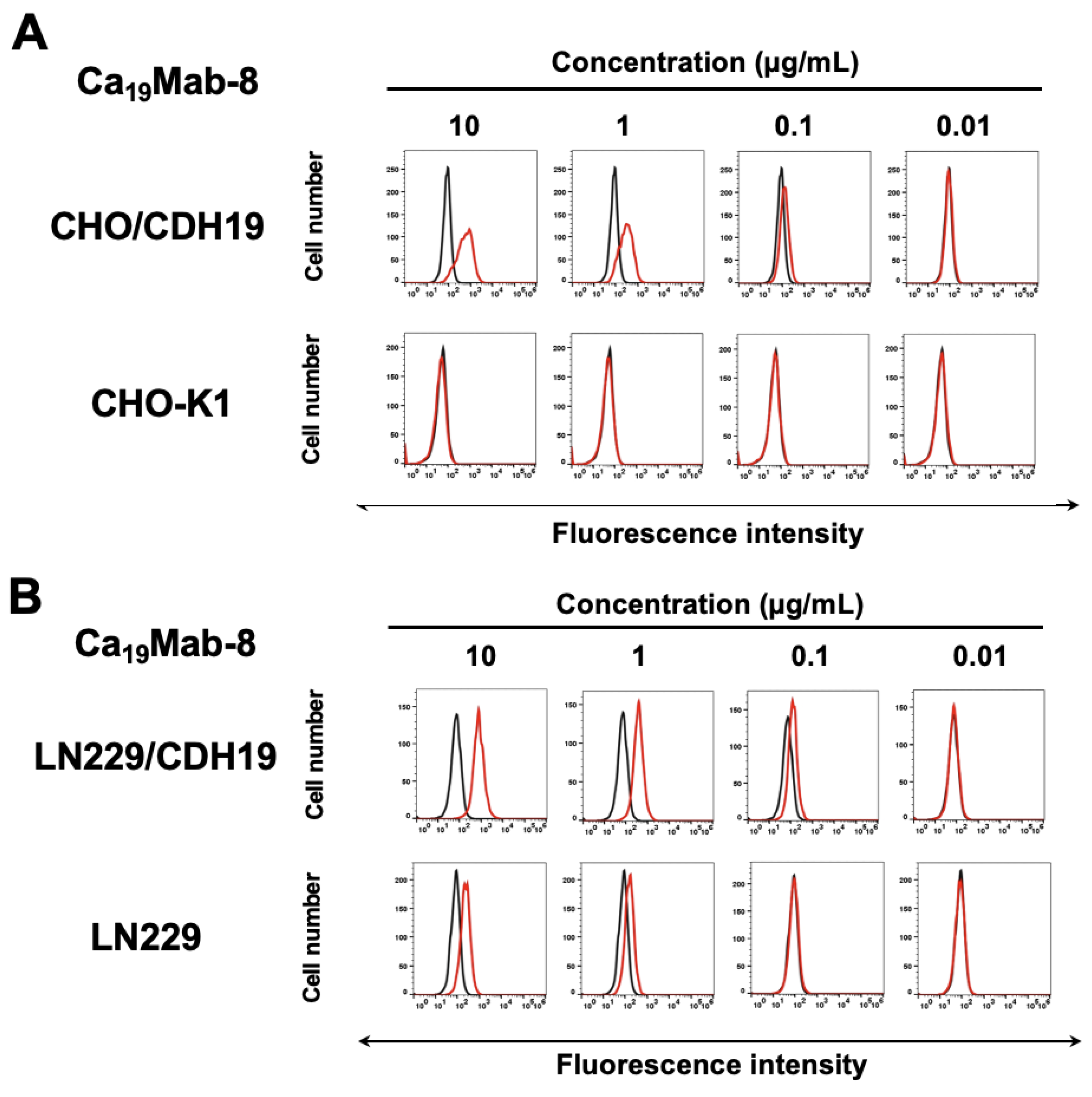

3.3. Flow Cytometry of Ca19Mab-8 Against CDH19-Overexpressed CHO-K1 and LN229

We next conducted flow cytometry using Ca

19Mab-8 (IgG

1, κ) against CHO/CDH19, CHO-K1, LN229/CDH19, and LN229. Ca

19Mab-8 reacted with CHO/CDH19 in a dose-dependent manner, from 10 to 0.01 μg/mL (

Figure 3A). In contrast, Ca

19Mab-8 did not recognize CHO-K1 at 10 μg/mL (

Figure 3A). Furthermore, Ca

19Mab-8 reacted with LN229/CDH19 in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 3A). Ca

19Mab-8 also showed reactivity to parental LN229, suggesting that LN229 expressed endogenous CDH19. The binding affinity of Ca

19Mab-8 was measured using flow cytometry. The fitting binding isotherms of Ca

19Mab-8 to LN229/CDH19 are shown in Supplementary

Figure 1. The

KD value of Ca

19Mab-8 for LN229/CDH19 was 9.0 × 10⁻⁹ M. These results indicate that Ca

19Mab-8 possesses a moderate binding affinity to LN229/CDH19.

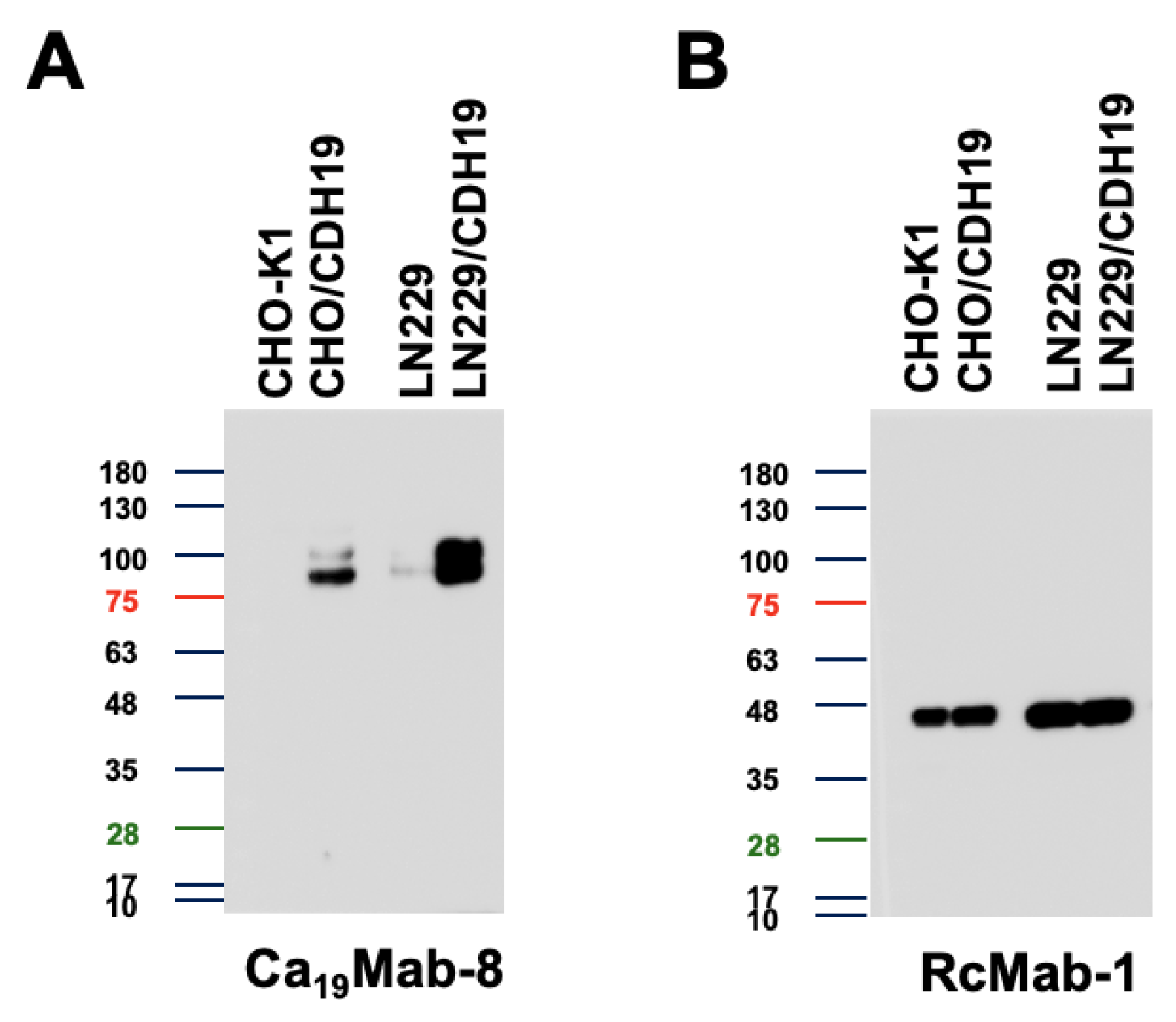

3.4. Western Blotting Using Ca19Mab-8

We then examined whether Ca

19Mab-8 is suitable for Western blotting. Whole-cell lysates from CHO-K1, CHO/CDH19, LN229, and LN229/CDH19 were analyzed. Ca

19Mab-8 detected clear bands around 90–100 kDa in CHO/CDH19 and LN229/CDH19, but not in CHO-K1 (

Figure 4A). It also detected weak bands in parental LN229 (

Figure 4A).

Figure 4B shows an internal control, IDH1, detected by RcMab-1. These results demonstrate that Ca

19Mab-8 can detect both exogenous and endogenous CDH19 in Western blotting.

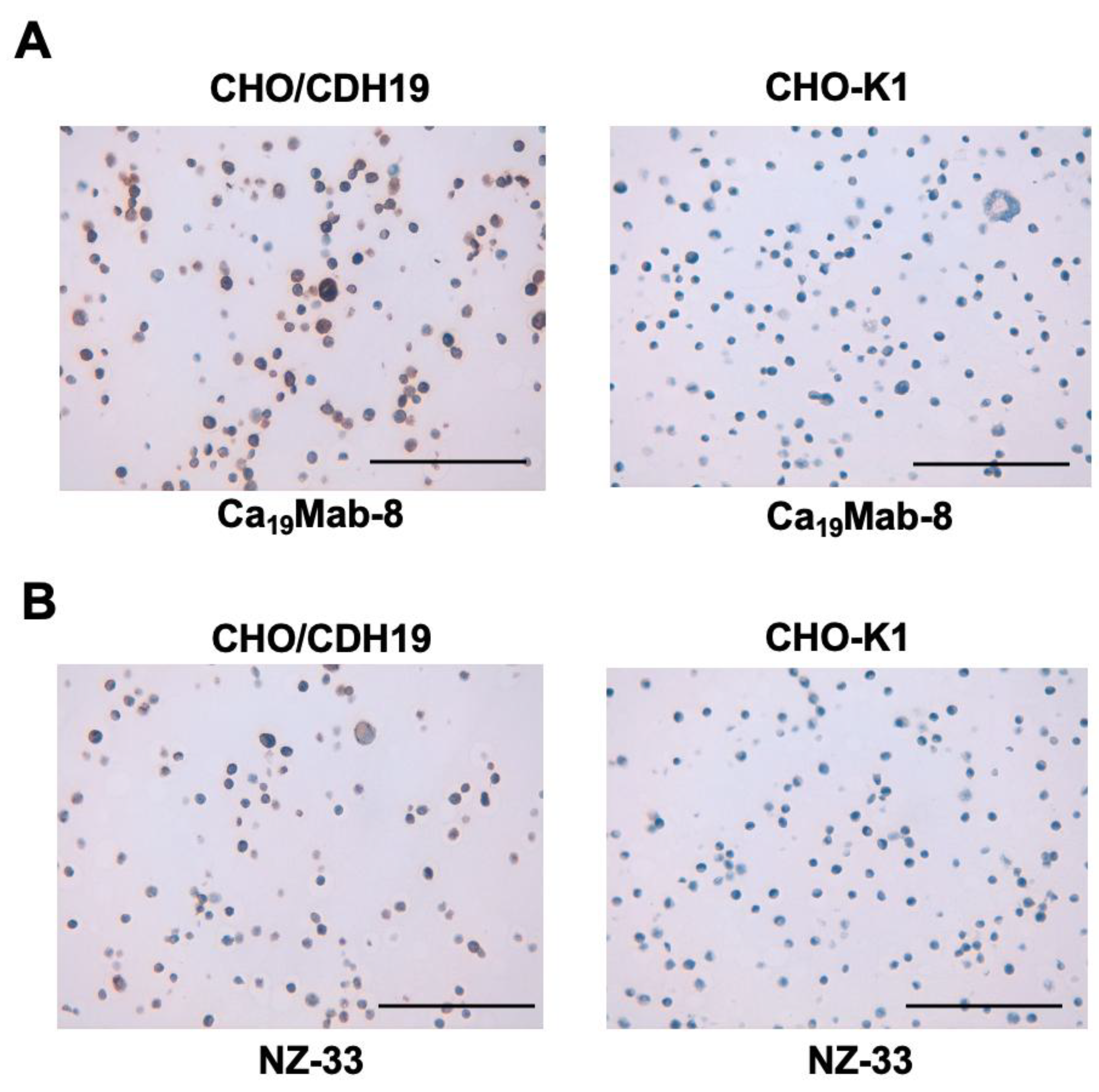

3.5. IHC using Ca19Mab-8 in Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Cell Blocks

We assessed whether Ca

19Mab-8 is suitable for immunohistochemistry (IHC) of FFPE sections from CHO-K1 and CHO/CDH19. Ca

19Mab-8 showed strong cytoplasmic and membranous staining in CHO/CDH19 but not in CHO-K1 (

Figure 5A). Additionally, an anti-PA16 tag mAb, NZ-33, exhibited cytoplasmic and membranous staining in CHO/CDH19, but not in CHO-K1 (

Figure 5B). These results suggest that Ca

19Mab-8 can detect CDH19 in IHC of FFPE sections of cultured cells.

4. Discussion

This study identified novel anti-CDH19 mAbs using the CBIS method (

Figure 1). Among them, Ca

19Mab-8 recognized both exogenous and endogenous CDH19 in flow cytometry and Western blotting (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Ca

19Mab-8 specifically binds to CDH19 but not to other type II, type I, 7D, truncated, or atypical CDHs (

Figure 2). In contrast, the other nine Ca

19Mabs showed cross-reactivity with CDH7 and other type II CDHs in flow cytometry (

Supplementary Table S1). Since most commercially available mAbs lack information on cross-reactivity, careful handling and interpretation are essential when using them. Identifying the Ca

19Mab-8 epitope is crucial for developing more specific anti-CDH19 mAbs. Additionally, Ca

19Mab-8 is suitable for IHC on cell blocks (

Figure 5). IHC was performed using an automated slide-staining system, allowing for standardized staining conditions. Ca

19Mab-8 is highly versatile for both basic research and clinical applications.

We demonstrated that Ca

19Mab-8 recognized human GBM LN229 cells in flow cytometry and Western blotting (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Although we examined the reactivity of Ca

19Mab-8 in other glioblastoma cell lines, LN229 is the only cell line identified by Ca

19Mab-8. In contrast, CDH19 was detected by Western blotting in GBM stem-like cells isolated from fresh GBM samples [

23]. We should investigate the reactivity of Ca

19Mab-8 with those samples and assess its antitumor efficacy. We previously cloned cDNA of mAb and produced recombinant mouse IgG

2a-type mAbs to confer antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC). These mAbs have been evaluated for the antitumor efficacy in human tumor xenograft models [

24,

25]. We have cloned the cDNA of Ca

19Mab-8, and recombinant Ca

19Mab-8 will be produced and evaluated for in vitro ADCC activity and antitumor activity in mouse glioblastoma xenograft models.

Metastatic melanoma remains a major clinical challenge [

26,

27]. Although therapeutic outcomes have significantly improved since the introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors, about half of patients with metastatic melanoma do not achieve long-term survival benefits [

28,

29]. A recent single-cell and spatial multi-omics analysis showed that drug-naive human melanoma biopsies contain cancer cells in a mesenchymal-like (MES) state [

30]. Melanoma cells in the MES state exhibit resistance to targeted therapy and immunotherapy and are more frequently found in lesions that do not respond to treatment [

30].

CDH19 was identified as a MES signature regulated by the master transcription factor TCF4. Targeting TCF4 genetically enhances immunogenicity and increases the sensitivity of MES cells to immunotherapy and targeted treatments [

30]. Therefore, CDH19 is a promising antigen for targeting drug-resistant melanoma cells in the MES state. Moreover, a patent (US 2025/0084160 A1, Mar.13, 2025) reports that CDH19 is expressed in melanoma cell lines, such as CHL-1, which can serve as a preclinical model for melanoma therapy. Since Ca

19Mab-8 can detect CDH19-positive cells by flow cytometry without cross-reactivity (

Figure 2), Ca

19Mab-8 will be a key foundation for developing various modalities, including antibody-drug conjugates, bispecific antibodies, and chimeric antigen receptor T cells.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Guanjie Li: Investigation Mika K. Kaneko: Conceptualization; Hiroyuki Suzuki: Writing – review and editing; Yukinari Kato: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review and editing; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Numbers: JP25am0521010 (to Y.K.), JP25ama121008 (to Y.K.), JP25ama221153 (to Y.K.), JP25ama221339 (to Y.K.), and JP25bm1123027 (to Y.K.), and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) grant nos. 25K18843 (to G.L.) and 25K10553 (to Y.K.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Tohoku University (Permit number: 2022MdA-001) for studies involving animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All related data and methods are presented in this paper. Additional inquiries should be addressed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest involving this article.

References

- Huang, T.; Hou, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Yi, C.; Wang, C.; Sun, X.; Tam, P.K.H.; Ngai, S.M.; Sham, M.H.; et al. Direct Interaction of Sox10 With Cadherin-19 Mediates Early Sacral Neural Crest Cell Migration: Implications for Enteric Nervous System Development Defects. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 179–192.e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Osumi, N. Identification of a novel type II classical cadherin: rat cadherin19 is expressed in the cranial ganglia and Schwann cell precursors during development. Dev Dyn 2005, 232, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Roy, F. Beyond E-cadherin: roles of other cadherin superfamily members in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2014, 14, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratheesh, A.; Yap, A.S. A bigger picture: classical cadherins and the dynamic actin cytoskeleton. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012, 13, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.H.; Cooper, L.M.; Anastasiadis, P.Z. Cadherins and catenins in cancer: connecting cancer pathways and tumor microenvironment. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1137013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Yang, L.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y. Cadherin Signaling in Cancer: Its Functions and Role as a Therapeutic Target. Front Oncol 2019, 9, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kools, P.; Van Imschoot, G.; van Roy, F. Characterization of three novel human cadherin genes (CDH7, CDH19, and CDH20) clustered on chromosome 18q22-q23 and with high homology to chicken cadherin-7. Genomics 2000, 68, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, D.; Xu, J.; Zhang, H.; Yu, W. New Insights on the Role of Satellite Glial Cells. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2023, 19, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, J.A.; Southard-Smith, E.M. Going the Extra Mile": A Sox10 Target, Cdh19, is Required for Sacral NC Migration in ENS Development. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.Y.; Flanagan, T.W.; Hassan, S.L.; Facca, S.; Haikel, Y.; Hassan, M. Mucosal Melanoma: Mechanisms of Its Etiology, Progression, Resistance and Therapy. Cells 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasescu, V.P.; Breazu, A.; Oprea, S.; Porosnicu, A.L.; Oproiu, A.; Rădoi, M.P.; Munteanu, O.; Pantu, C. The Neuro-Melanoma Singularity: Convergent Evolution of Neural and Melanocytic Networks in Brain Metastatic Adaptation. Biomolecules 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershenwald, J.E.; Scolyer, R.A. Melanoma Staging: American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th Edition and Beyond. Ann Surg Oncol 2018, 25, 2105–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.W.; Versluis, J.M.; Rozeman, E.A.; Blank, C.U. Personalizing neoadjuvant immune-checkpoint inhibition in patients with melanoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2023, 20, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardoll, D.M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2012, 12, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Ding, Y.; Tran, L.J.; Chai, G.; Lin, L. Innovative breakthroughs facilitated by single-cell multi-omics: manipulating natural killer cell functionality correlates with a novel subcategory of melanoma cells. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1196892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubukata, R.; Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of novel anti-CDH1/E-cadherin monoclonal antibodies for versatile applications. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2026, 45, 102401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubukata, R.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of an anti-CDH15/M-cadherin monoclonal antibody Ca(15)Mab-1 for flow cytometry, immunoblotting, and immunohistochemistry. Biochem Biophys Rep 2025, 43, 102138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Neyazaki, M.; Nogi, T.; Kato, Y.; Takagi, J. PA tag: a versatile protein tagging system using a super high affinity antibody against a dodecapeptide derived from human podoplanin. Protein Expr Purif 2014, 95, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. MAP Tag: A Novel Tagging System for Protein Purification and Detection. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2016, 35, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satofuka, H.; Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of Anti-Human Cadherin-26 Monoclonal Antibody, Ca26Mab-6, for Flow Cytometry. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. Development and characterization of Ea7Mab-10: A novel monoclonal antibody targeting ephrin type-A receptor 7. MI 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorniak, M.; Clark, P.A.; Kuo, J.S. Myelin-forming cell-specific cadherin-19 is a marker for minimally infiltrative glioblastoma stem-like cells. J Neurosurg 2015, 122, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubukata, R.; Ohishi, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. EphB2-Targeting Monoclonal Antibodies Exerted Antitumor Activities in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Lung Mesothelioma Xenograft Models. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; Nakamura, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kato, Y. A Cancer-Specific Monoclonal Antibody against HER2 Exerts Antitumor Activities in Human Breast Cancer Xenograft Models. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Grob, J.J.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Karaszewska, B.; Hauschild, A.; Levchenko, E.; Chiarion Sileni, V.; Schachter, J.; Garbe, C.; Bondarenko, I.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes with Dabrafenib plus Trametinib in Metastatic Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2019, 381, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.J.; Rutkowski, P.; Lao, C.D.; Cowey, C.L.; Schadendorf, D.; Wagstaff, J.; Dummer, R.; et al. Five-Year Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2019, 381, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Ribas, A.; Schachter, J.; Arance, A.; Grob, J.J.; Mortier, L.; Daud, A.; Carlino, M.S.; McNeil, C.M.; Lotem, M.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma (KEYNOTE-006): post-hoc 5-year results from an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2019, 20, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Rutkowski, P.; Grob, J.J.; Cowey, C.L.; Lao, C.D.; Wagstaff, J.; Schadendorf, D.; Ferrucci, P.F.; et al. Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozniak, J.; Pedri, D.; Landeloos, E.; Van Herck, Y.; Antoranz, A.; Vanwynsberghe, L.; Nowosad, A.; Roda, N.; Makhzami, S.; Bervoets, G.; et al. A TCF4-dependent gene regulatory network confers resistance to immunotherapy in melanoma. Cell 2024, 187, 166–183.e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of anti-CDH19 mAbs production. A) LN229/CDH19 was injected into BALB/cAJcl mice intraperitoneally. (B) After five immunizations, spleen cells were fused with P3U1. (C) The supernatants from hybridomas were screened by flow cytometry using CHO/CDH19 and CHO-K1 cells. (D) Anti-CDH19 mAb-producing hybridoma clones (Ca19Mabs) were established through limiting dilution.

Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of anti-CDH19 mAbs production. A) LN229/CDH19 was injected into BALB/cAJcl mice intraperitoneally. (B) After five immunizations, spleen cells were fused with P3U1. (C) The supernatants from hybridomas were screened by flow cytometry using CHO/CDH19 and CHO-K1 cells. (D) Anti-CDH19 mAb-producing hybridoma clones (Ca19Mabs) were established through limiting dilution.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry analysis of Ca19Mab-8 in CDHs-overexpressed CHO-K1. (A) The type I CDHs (CDH1, CDH2, CDH3, CDH4, and CDH15), type II CDHs (CDH5, CDH6, CDH7, CDH8, CDH9, CDH10, CDH11, CDH12, CDH18, CDH19, CDH20, CDH22, and CDH24), 7D CDHs (CDH16 and CDH17), a truncated CDH (CDH13), and an atypical CDH (CDH26)-overexpressed CHO-K1 were treated with 10 µg/mL of Ca19Mab-8 (red) or with control blocking buffer (black, negative control), followed by treatment with anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488. (B) Each CDH expression was confirmed by 1 µg/mL of an anti-CDH1 mAb (clone 67A4, BD Biosciences), 1 µg/mL of an anti-CDH3 mAb (clone MM0508-9V11, Abcam), and 1 µg/mL of an anti-PA16-tag mAb (clone NZ-33) to detect other CDHs, followed by the treatment with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary mAbs. The fluorescence data were collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry analysis of Ca19Mab-8 in CDHs-overexpressed CHO-K1. (A) The type I CDHs (CDH1, CDH2, CDH3, CDH4, and CDH15), type II CDHs (CDH5, CDH6, CDH7, CDH8, CDH9, CDH10, CDH11, CDH12, CDH18, CDH19, CDH20, CDH22, and CDH24), 7D CDHs (CDH16 and CDH17), a truncated CDH (CDH13), and an atypical CDH (CDH26)-overexpressed CHO-K1 were treated with 10 µg/mL of Ca19Mab-8 (red) or with control blocking buffer (black, negative control), followed by treatment with anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488. (B) Each CDH expression was confirmed by 1 µg/mL of an anti-CDH1 mAb (clone 67A4, BD Biosciences), 1 µg/mL of an anti-CDH3 mAb (clone MM0508-9V11, Abcam), and 1 µg/mL of an anti-PA16-tag mAb (clone NZ-33) to detect other CDHs, followed by the treatment with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary mAbs. The fluorescence data were collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer.

Figure 3.

Flow cytometric analysis of Ca19Mab-8. (A) CHO/CDH19 and CHO-K1 were treated with Ca19Mab-8 at the indicated concentrations (red) or with blocking buffer (black, negative control). (B) LN229/CDH19 and LN229 were treated with Ca19Mab-8 at the indicated concentrations (red) or with blocking buffer (black, negative control). The mAbs-treated cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Fluorescence data were collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer.

Figure 3.

Flow cytometric analysis of Ca19Mab-8. (A) CHO/CDH19 and CHO-K1 were treated with Ca19Mab-8 at the indicated concentrations (red) or with blocking buffer (black, negative control). (B) LN229/CDH19 and LN229 were treated with Ca19Mab-8 at the indicated concentrations (red) or with blocking buffer (black, negative control). The mAbs-treated cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Fluorescence data were collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer.

Figure 4.

Western blotting using Ca19Mab-8. Cell lysates (10 μg/lane) from CHO-K1, CHO/CDH19, LN229, and LN229/CDH19 were electrophoresed and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were incubated with 1 μg/mL of Ca19Mab-8 (A) or 1 μg/mL of RcMab-1 (an anti-IDH1 mAb) (B), followed by the treatment with anti-mouse (Ca19Mab-8) or anti-rat IgG (RcMab-1)-conjugated with horseradish peroxidase.

Figure 4.

Western blotting using Ca19Mab-8. Cell lysates (10 μg/lane) from CHO-K1, CHO/CDH19, LN229, and LN229/CDH19 were electrophoresed and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were incubated with 1 μg/mL of Ca19Mab-8 (A) or 1 μg/mL of RcMab-1 (an anti-IDH1 mAb) (B), followed by the treatment with anti-mouse (Ca19Mab-8) or anti-rat IgG (RcMab-1)-conjugated with horseradish peroxidase.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry using Ca19Mab-8 in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded cell blocks. CHO/CDH19 and CHO-K1 sections were treated with 0.2 μg/mL of Ca19Mab-8 (A) or 0.01 µg/mL of NZ-33 (B). The staining was performed using BenchMark ULTRA PLUS with the ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit, Scale bar = 100 μm.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry using Ca19Mab-8 in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded cell blocks. CHO/CDH19 and CHO-K1 sections were treated with 0.2 μg/mL of Ca19Mab-8 (A) or 0.01 µg/mL of NZ-33 (B). The staining was performed using BenchMark ULTRA PLUS with the ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit, Scale bar = 100 μm.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |