Submitted:

05 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. HD-TVP-VAR-DY Model

2.2. Construction of Risk Spillover Indices

3. Results

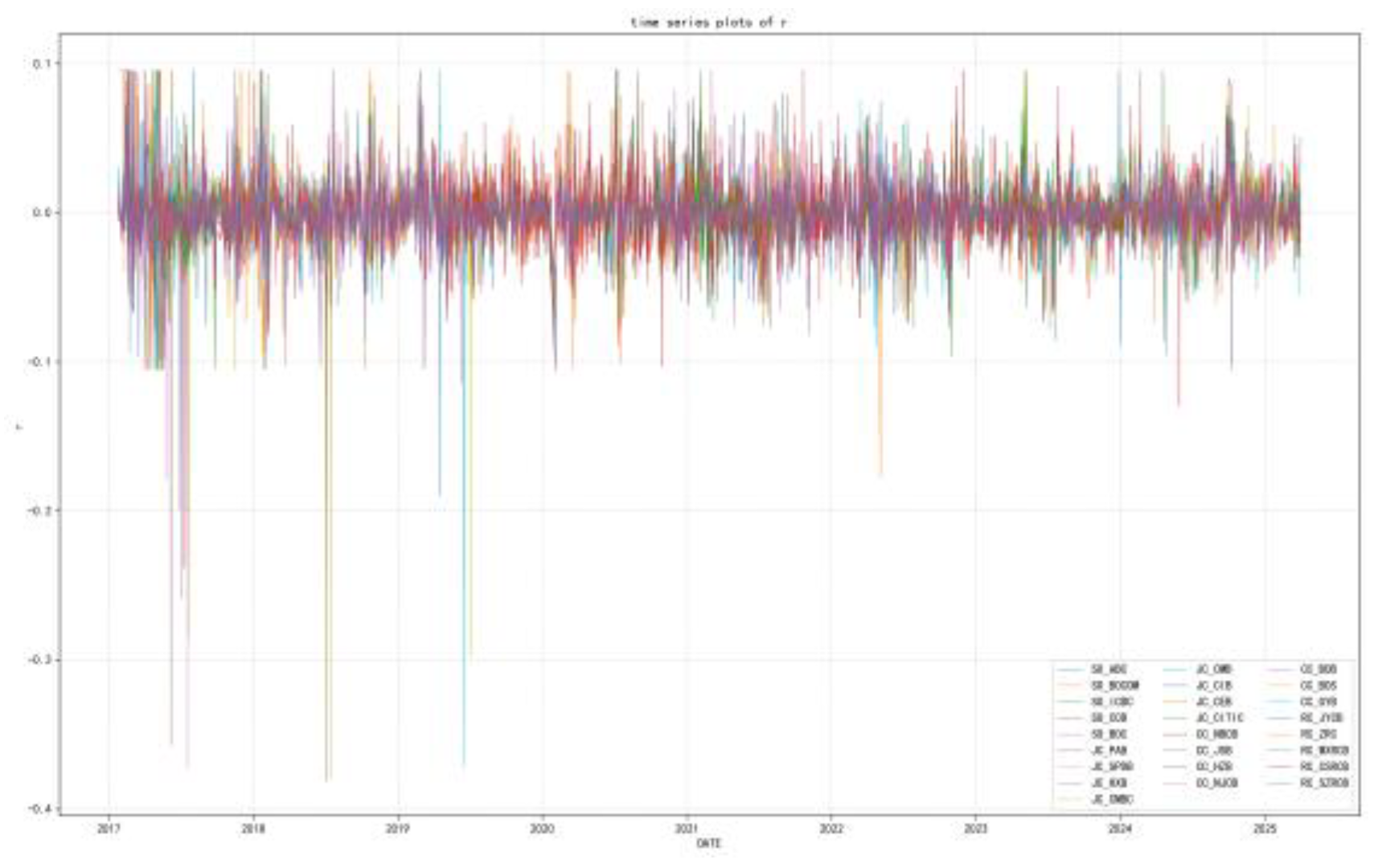

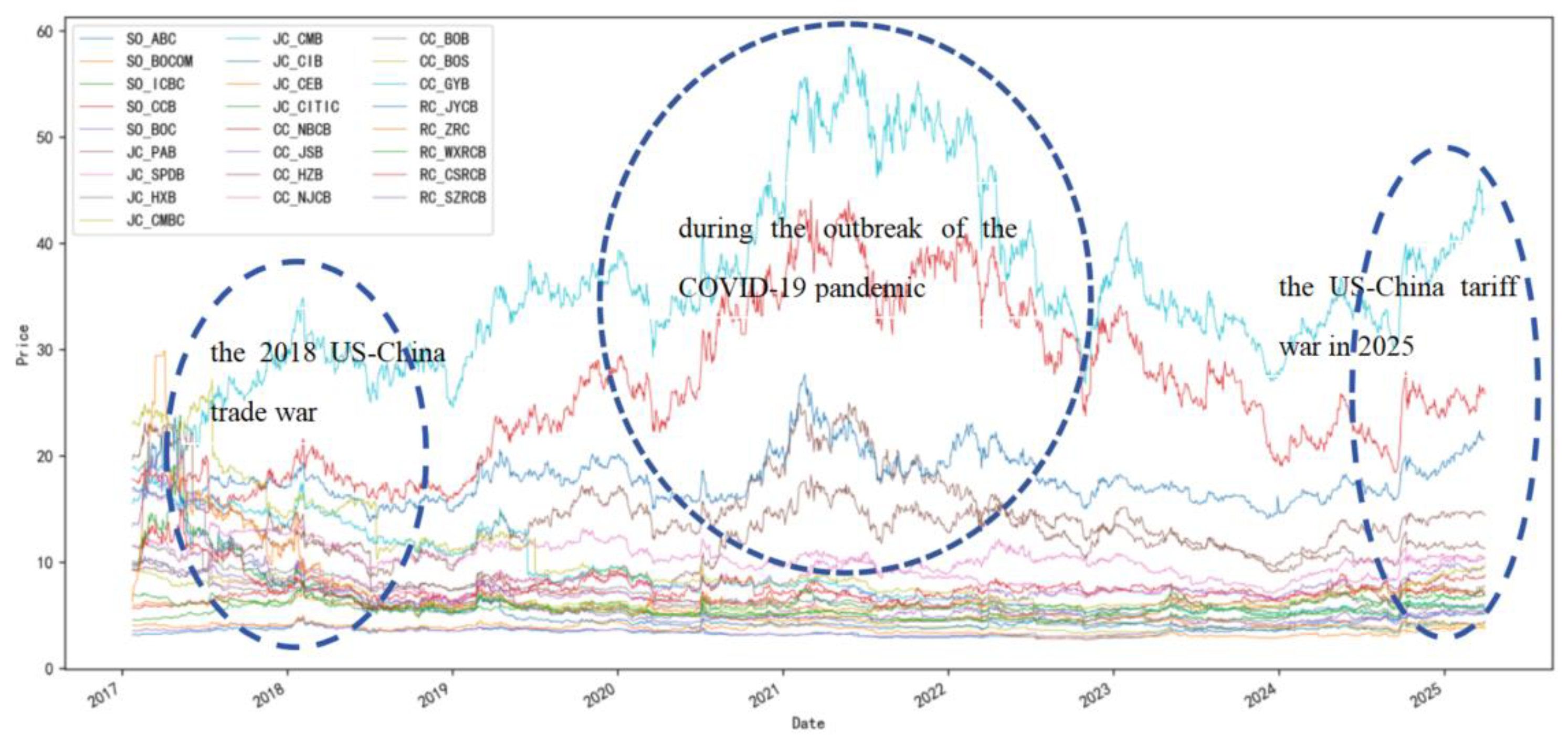

3.1. Data and Sample Selection

3.1.1. Sample Selection

3.1.2. Sample Selection

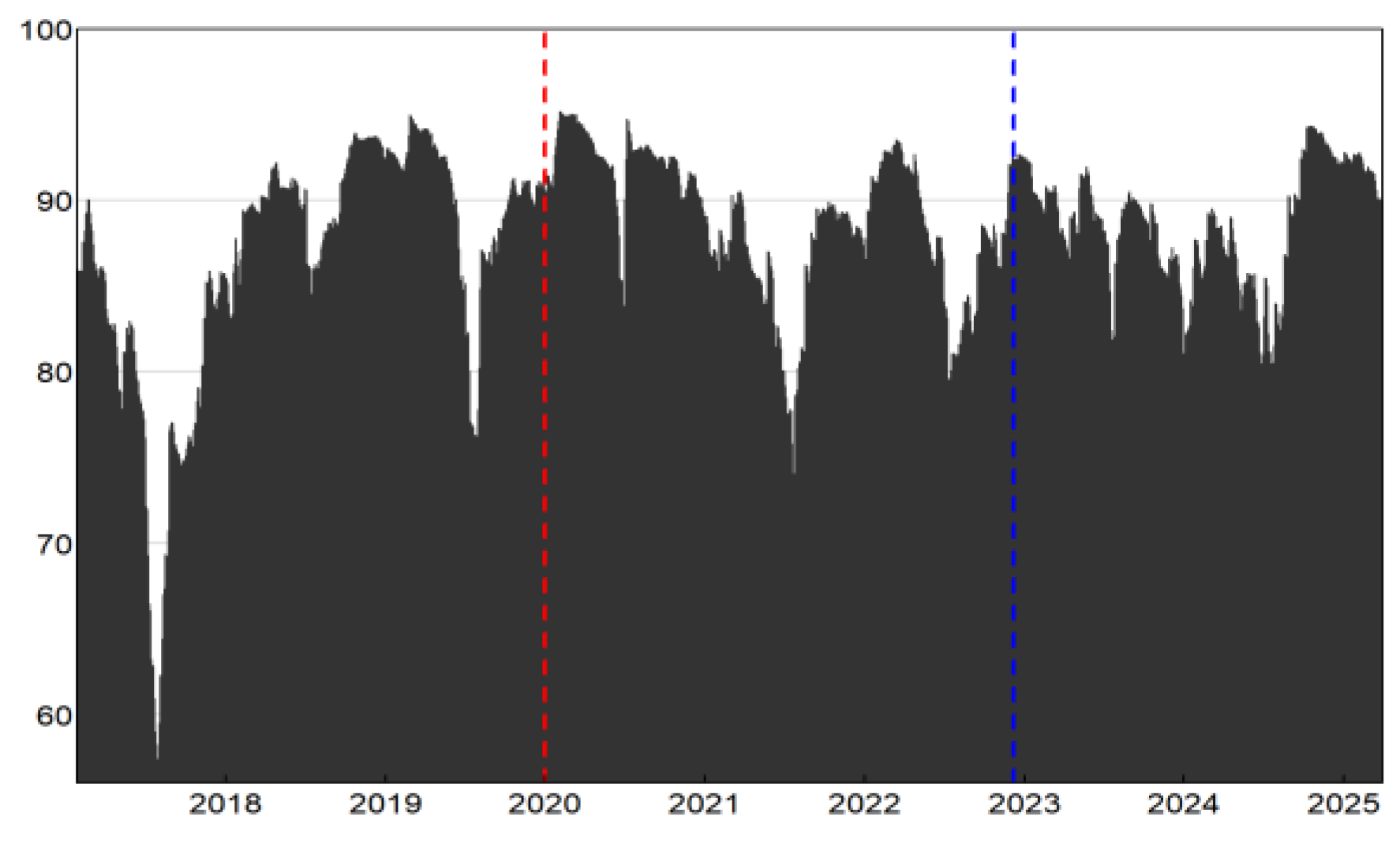

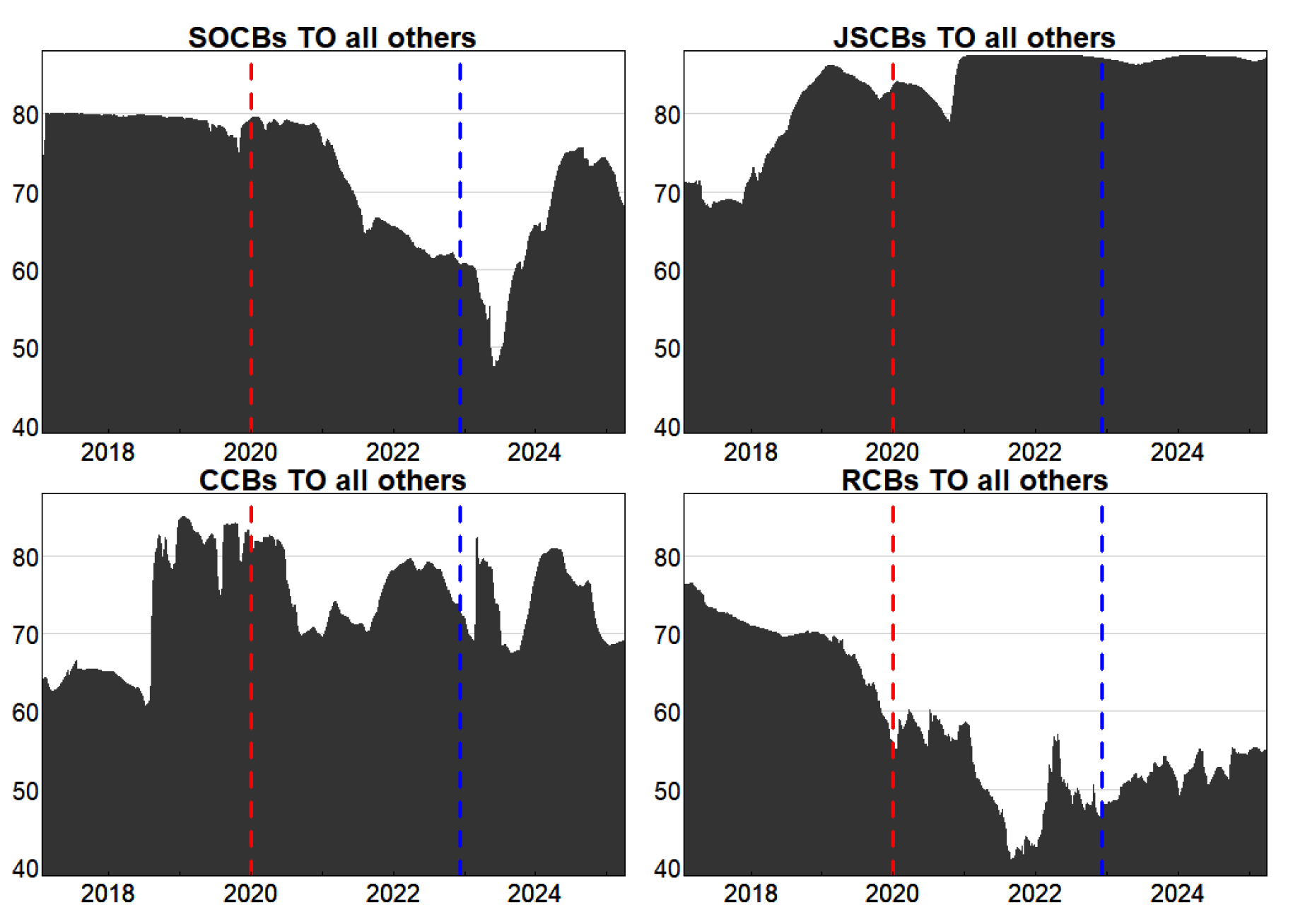

3.2. Dynamic Evolution of Interbank Risk Transmission and Systemic Importance Analysis

3.2.1. Analysis of Aggregate and Localized Spillovers

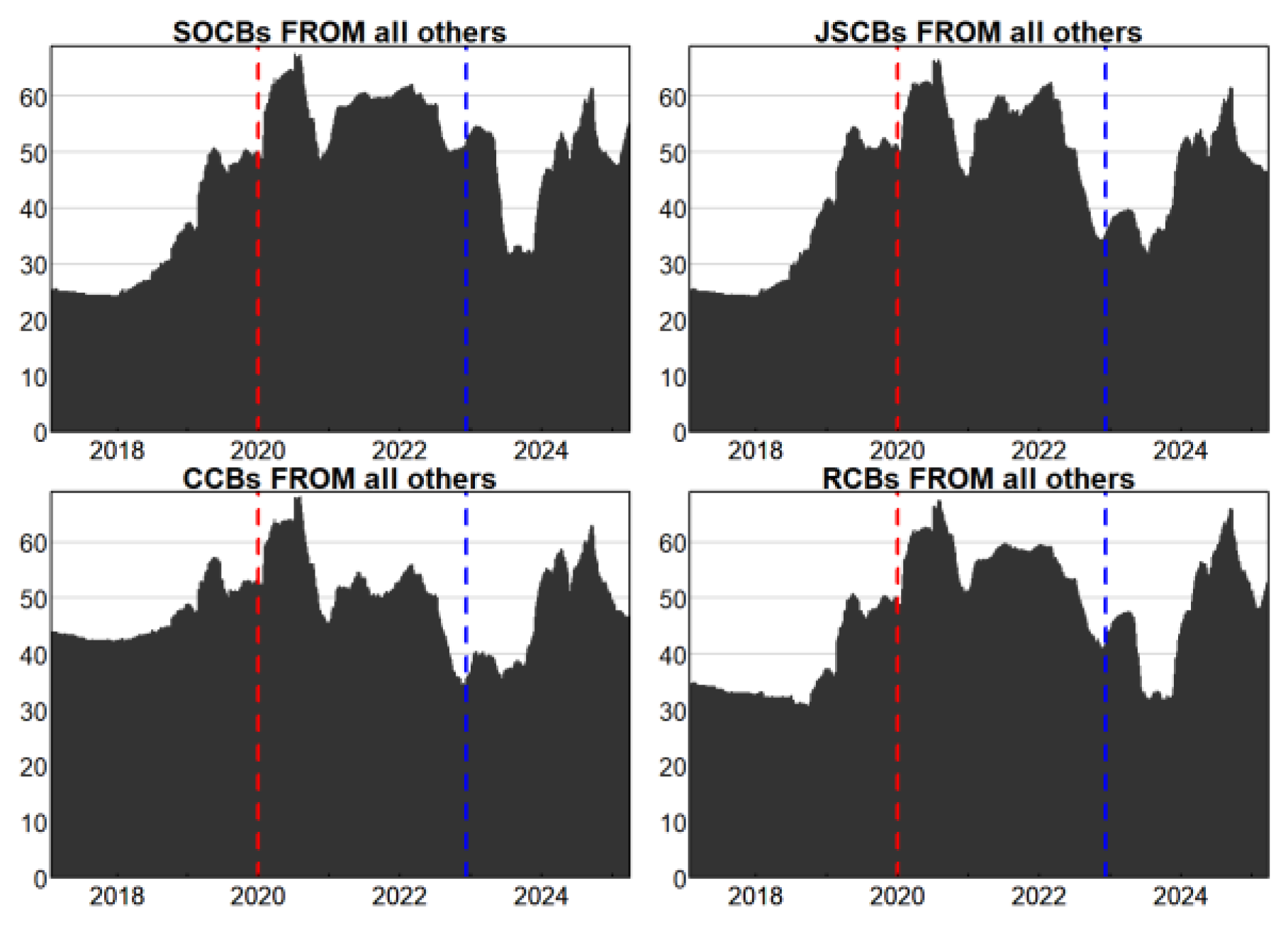

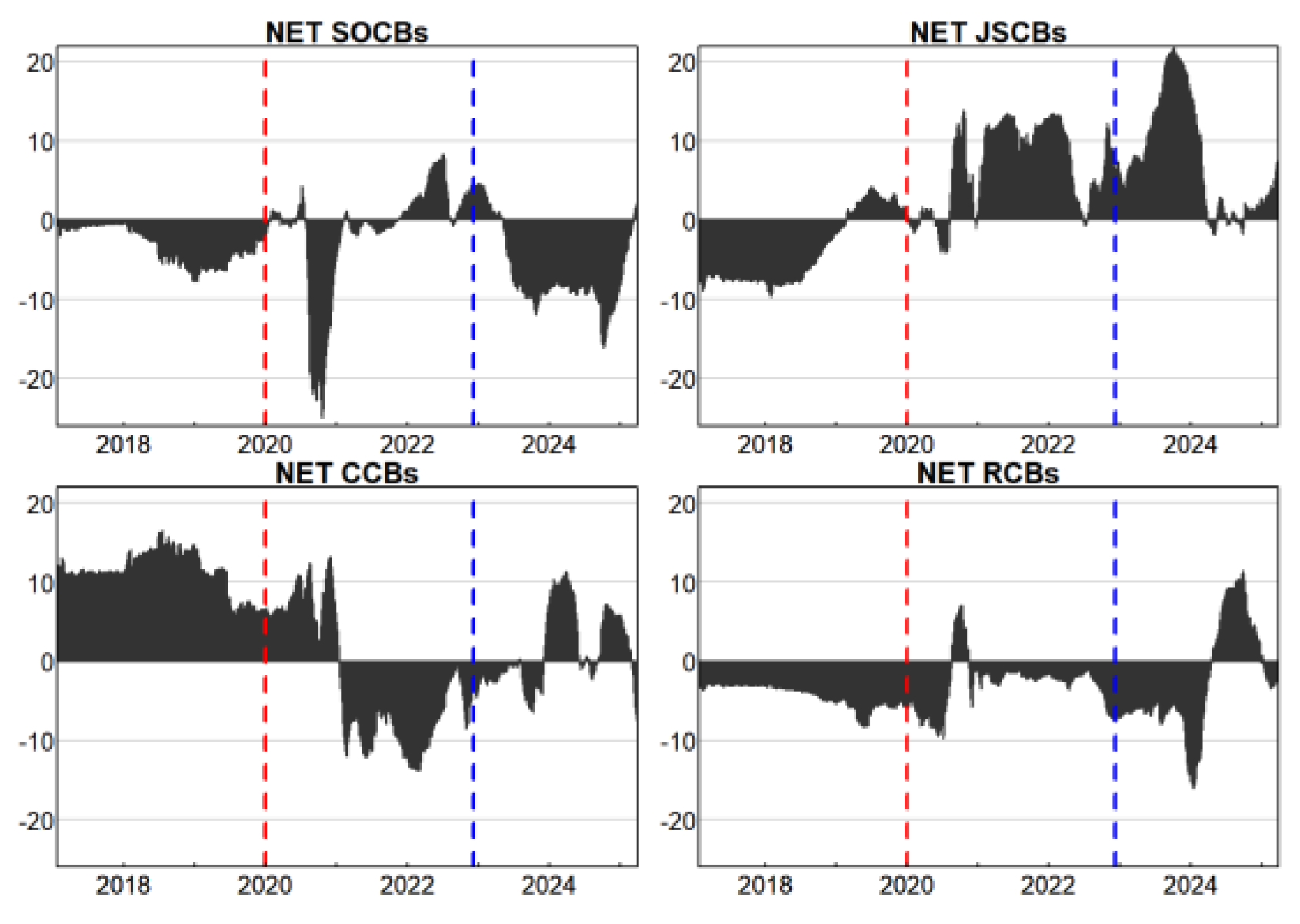

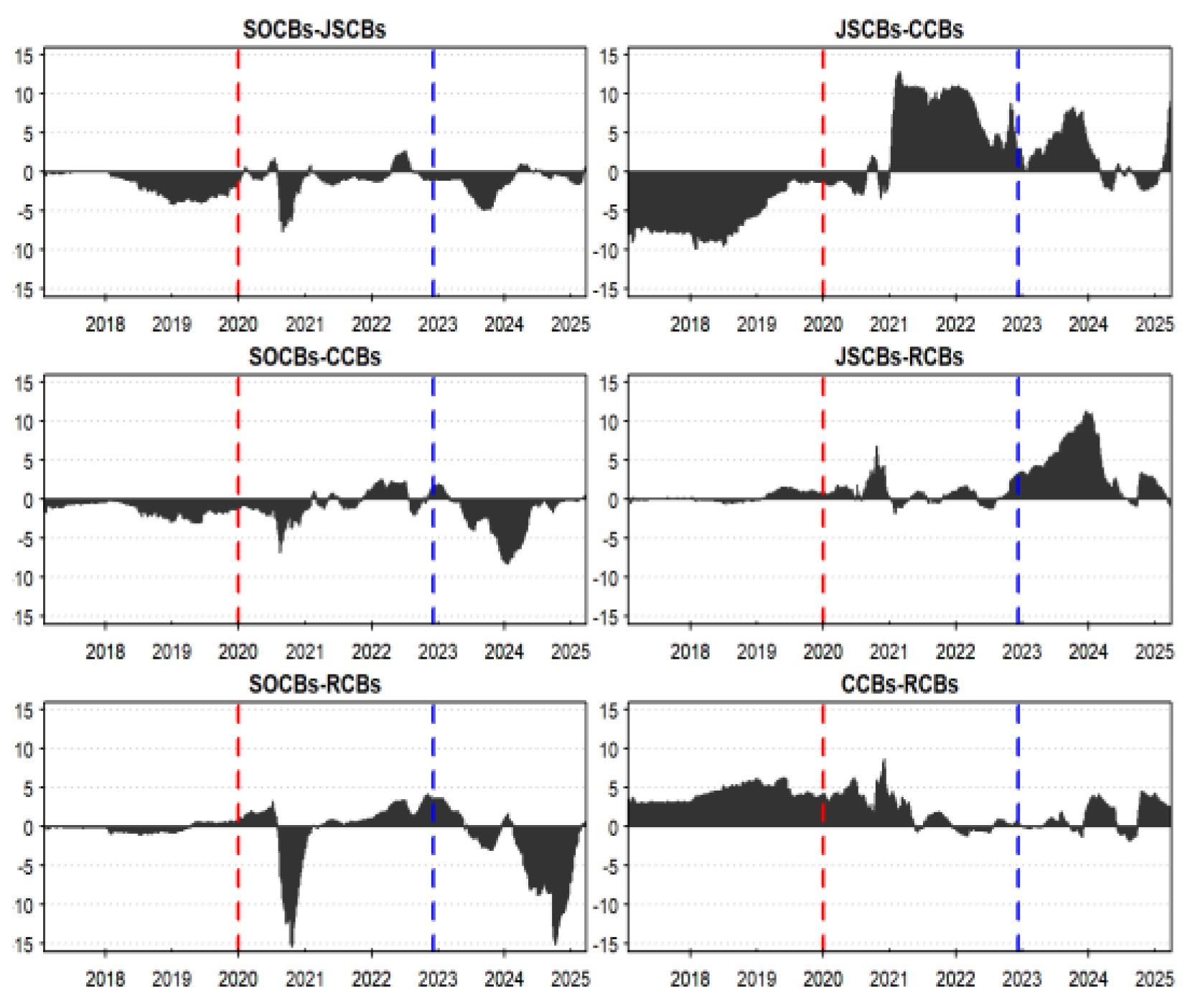

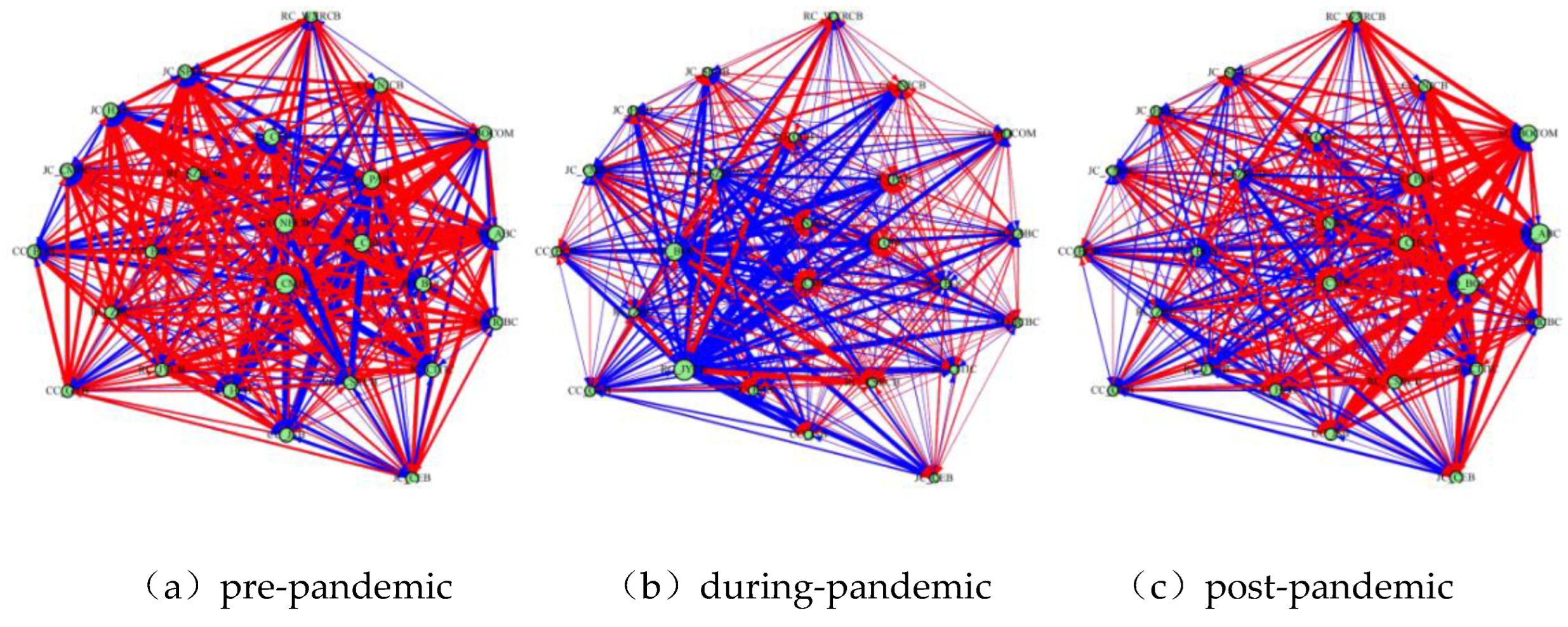

3.2.2. Analysis of Interbank Spillover Intensity and Directionality

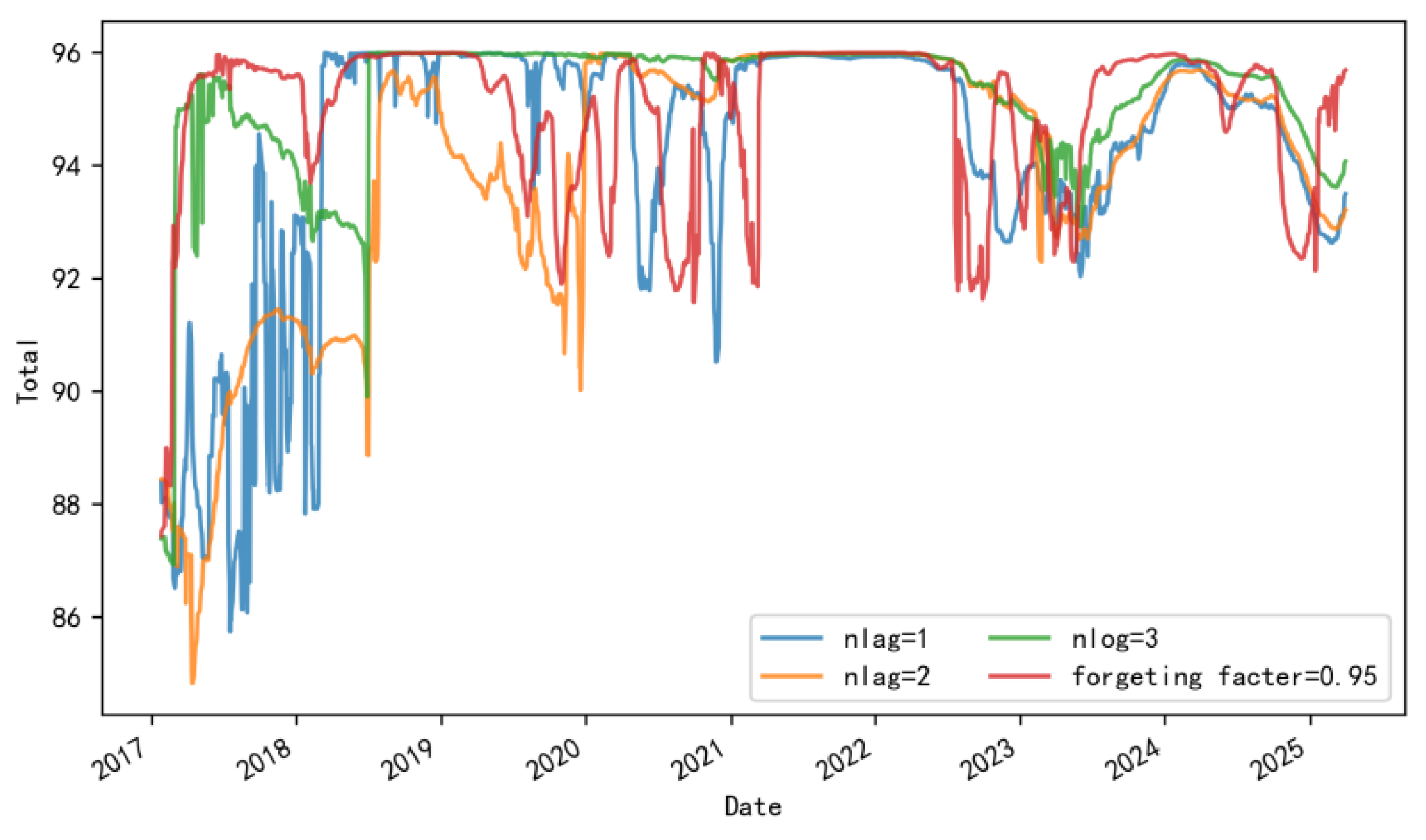

3.2.3. Robustness Checks

3.3. Analysis of Systemic Importance

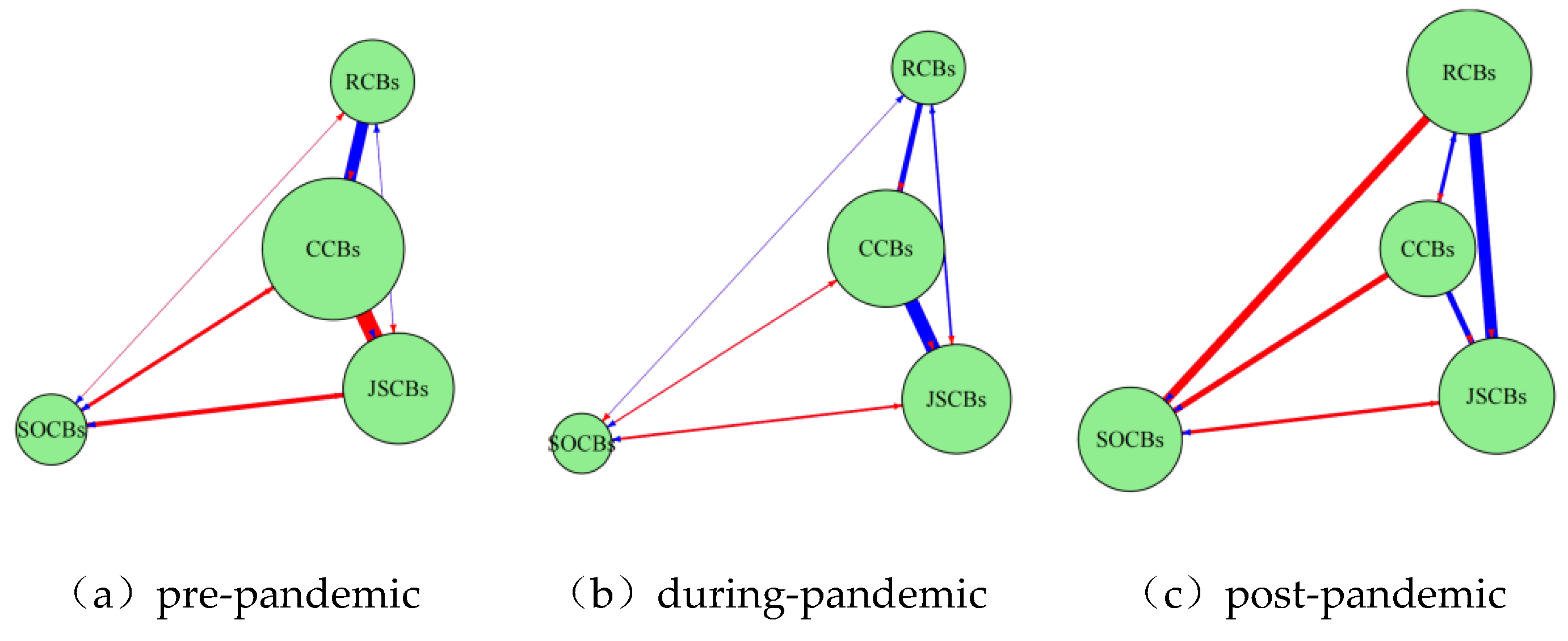

3.3.1. Analysis of Systemic Importance across Banking Categories

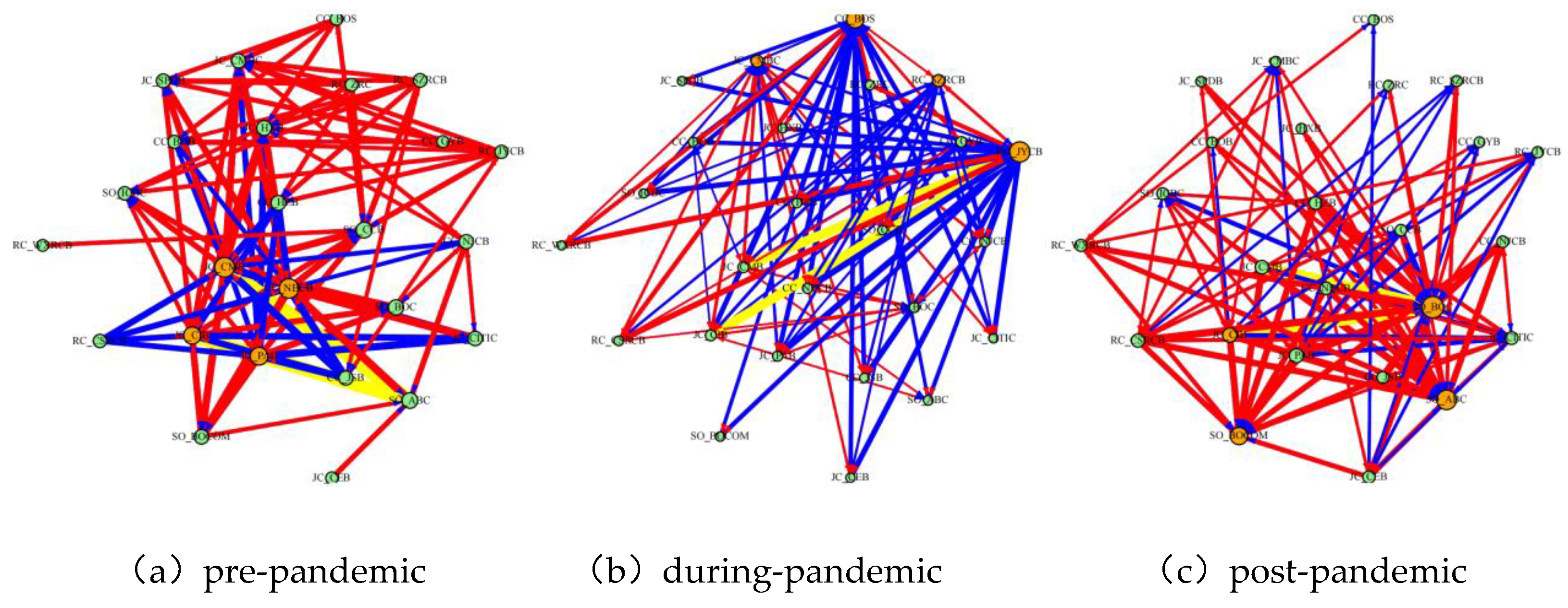

3.3.2. Bank-Level Assessment of Systemic Importance in Different Periods

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Bank name | mean | sd | skew | kurtosis | se | P value | Bank name | mean | sd | skew | kurtosis | se | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO_ABC | 3.572 | 0.561 | 1.099 | 0.924 | 0.013 | 0.9092 | CC_NBCB | 26.135 | 7.454 | 0.453 | -0.857 | 0.167 | 0.5518 |

| SO_BOCOM | 5.665 | 0.861 | 0.437 | -0.573 | 0.019 | 0.7163 | CC_JSB | 7.247 | 1.054 | 0.881 | 0.314 | 0.024 | 0.5271 |

| SO_ICBC | 5.284 | 0.648 | 0.641 | 0.223 | 0.015 | 0.7968 | CC_HZB | 12.374 | 3.237 | 0.753 | 1.172 | 0.073 | 0.2818 |

| SO_CCB | 6.707 | 0.785 | 0.742 | 0.589 | 0.018 | 0.7615 | CC_NJCB | 9.022 | 1.27 | 0.315 | -0.792 | 0.028 | 0.4269 |

| SO_BOC | 3.724 | 0.581 | 1.154 | 0.997 | 0.013 | 0.9169 | CC_BOB | 5.569 | 1.312 | 1.52 | 2.114 | 0.029 | 0.03128 |

| JC_PAB | 13.396 | 3.585 | 1.137 | 0.809 | 0.08 | 0.5024 | CC_BOS | 9.997 | 4.754 | 1.694 | 2.222 | 0.107 | 0.02236 |

| JC_SPDB | 9.963 | 2.241 | 0.583 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.0957 | CC_GYB | 8.793 | 3.64 | 0.885 | -0.576 | 0.082 | 0.05852 |

| JC_HXB | 7.01 | 1.562 | 0.991 | 0.457 | 0.035 | 0.139 | RC_JRCB | 5.491 | 3.298 | 3.182 | 10.931 | 0.074 | 0.1651 |

| JC_CMBC | 5.318 | 1.69 | 0.735 | -0.63 | 0.038 | 0.02068 | RC_ZRC | 6.696 | 3.925 | 2.988 | 10.408 | 0.088 | 0.2204 |

| JC_CMB | 35.592 | 8.486 | 0.584 | 0.031 | 0.19 | 0.7082 | RC_WXRCB | 6.457 | 2.359 | 3.408 | 14.112 | 0.053 | 0.2257 |

| JC_CIB | 17.79 | 2.146 | 1.061 | 1.37 | 0.048 | 0.6238 | RC_CSRCB | 7.652 | 1.405 | 2.206 | 5.884 | 0.032 | 0.3622 |

| JC_CEB | 3.638 | 0.461 | -0.1 | -1.046 | 0.01 | 0.4767 | RC_SZRCB | 6.238 | 3.04 | 2.707 | 7.184 | 0.068 | 0.0507 |

| JC_CITIC | 5.742 | 0.763 | 0.083 | -0.884 | 0.017 | 0.5202 |

References

- Allen, F.; Gale, D. Financial contagion. J. Polit. Econ. 2000, 108(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; He, P.; Liu, Z. Financial Contagion, Market Freezes, and Prudential Policies in the Interbank Market-A Network Perspective. Journal of Financial Research 2024, 02, 38–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Wang, J.; Tian, F. Bank network structure and systemic financial risk contagion. Systems Engineering-Theory & Practice. 2024, 44(07), 2120–2136. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.2267.N.20240402.1356.006.

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, R.; Li, Y. Research on the Network Connectivity and Risk Contributions of China’s Systemically Important Banks: A Perspective of Extreme Event Shocks. Journal of Central University of Finance & Economics. 2025, 04, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Pang, X.; Zhu, S. Measurement and evaluation of systemic risk for China’s banking system. Journal of Management Sciences in China. 2023, 26(12), 85–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Li, Z.; Hao, X. Identification and Regulation of Systemically Important Financial Institutions in China-An Analysis Based on the Systemic Risk Index SRISK Methodology. Journal of Financial Research 2013, 9, 56–70. [Google Scholar]

- Diehold, F.X.; Yilmaz, K. On the Network Topology of Variance Decompositions: Measuring the Connectedness of Finance Firms. J. Econom 2014, 182(1), 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakakis, N.; Chatziantoniou, I.; Gabauer, D. Refined measures of dynamic connectedness based on time-varying parameter vector autoregressions. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Zhang, J. A Study on Volatility Spillovers between China’s Energy Market and Stock Market-An Empirical Study Based on TVP-VAR-DY Model. Journal of Southwest Minzu University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition) 2022, 43(05), 122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Lan, F. Research on China’s High Level Financial Openness from the Perspective of Financial Security. Studies of International Finance 11, 16–27. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Tang, H.; Xu, D. Study on the Path of RMB Internationalization Based on Carbon Trading--Insights from Empirical Evidence in European Carbon Trading Markets. Studies of International Finance 2024, 08, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhu, L. On the Dynamic Relationship between the Monetary Policy and the Macro Leverage and Financial Stability--Based on the Construction of China’s Financial Stability Index. Jinan Journal(Philosophy & Social Sciences) 2023, 45(12), 110–128. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yin, Z. Extreme time-varying spillovers between high carbon emission stocks, green bond and crude oil: Evidence from a quantile-based analysis. Energy Econ. 2023, 118, 106511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirer, M.; Diebold, F. X.; Liu, L.; et al. Estimating global bank network connectedness. J. Appl. Econom. 33(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, J.; Tan, L.; Yang, H. The High-Dimensional Time-Varying Measurem -ent and Transmission Mechanism of Systemic Financial Risk in China. The Journal of World Economy 2021, 12, 28–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Wei, Y. Information spillovers between investor’s public health emergency attention and industrial stocks: Empirical evidence from TVP-VAR model. Journal of Management Science 2024, 32(01), 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, B.; Wei, G.; Bai, L.; Wei, Y.; Liang, C. Return connectedness among commodity and financial assets during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from China and the US. Resour. Policy 2021, 73, 102166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wang, Z.; Hu, S.; Shi, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. A Study on the Transnational Spillover Effects of Bank Risk and Sovereign Risk–From the Perspective of COVID-19 Epidemic Situation. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 940126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koop, G.; Korobilis, D. Large Time-Varying Parameter VARs. J. Econom 2013, 177, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Tan, L.; Yang, H.; Cui, J. A study on the systemic importance of financial industries:A complex network analysis based on HD-TVP-VAR model. Systems Engineering -Theory & Practice 2021, 41(8), 1911–1925. [Google Scholar]

- PersaranH, H.; Shin, Y. Generalized impluse response analysis in linear multivariate moedls. Econ. Lett. 1998, 58(1), 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ma, H.; Wang, X.; Cui, J.; Shen, X. A comparative study of dynamic risk spillovers among financial sectors in China before and after the epidemic. PLoS One 2024, 19(12), e0314071. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0314071. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Banking Classification | Listed Branches Institutions |

Abbreviation | Banking Classification | Listed Branches Institutions |

Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State-owned Banks (Abbreviated as: SOCs) |

Industrial and Commercial Bank of China | ICBC | City Commercial Banks (Abbreviated as: CCBs) | Bank of Beijing | BOB |

| China Construction Bank | CCB | Shanghai Bank | BOS | ||

| Agricultural Bank of China | ABC | Nanjing Bank | NJCB | ||

| Bank of China | BOC | Ningbo Bank | NBCB | ||

| Bank of Communications | BOCOM | Hangzhou Bank | HZBANK | ||

| Joint- stock Commercial Banks (Abbreviated as: JSCBs) |

China Merchants Bank | CMB | Jiangsu Bank | JSB | |

| Industrial Bank | CIB | Guiyang Bank | GYB | ||

| Shanghai Pudong Development Bank | SPDB | Rural Commercial Banks (Abbreviated as: RCBs) | Wuxi Bank | WXRCB | |

| China CITIC Bank | CITIC | Zhangjiagang Bank | ZRC | ||

| Minsheng Bank | CMBC | Changshu Bank | CSRCB | ||

| Everbright Bank | CEB | Suzhou Bank | SZRCB | ||

| Ping An Bank | PAB | Jiangyin Bank | JRCB | ||

| Huaxia Bank | HXB |

| Period | Time Period | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| pre-pandemic | 2017.1.24- 2019.12.31 |

This period involves significant financial incidents such as the US-Chinese trade dispute of 2018, simultaneous large-scale withdrawals from the P2P lending market, as well as the start of financial deleveraging policies. This stage ends prior to the appearance of the first notifications for COVID-19 cases. |

| during- pandemic | 2020.1.2- 2022.12.8 |

This period consists of two sub-stages: the initial rapid transmission stage (from January 2, 2020, to April 8, 2020), and the normalized prevention and control stage (prior to full reopening) after the Wuhan lockdown lifted (from April 9, 2020, to December 8, 2022). |

| post- pandemic |

2022.12.9- 2025.3.31 |

After December 8, 2022, mandatory nationwide mass PCR screening ceased (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan) to be replaced by voluntary PCR tests (“Yuan Jian Jin Jian”). Thus, the nation shifted to a fully opened normalized stage, which marked the end of the extensive anti-pandemic campaign. |

| Bank name | mean | sd | skew | kurtosis | P- value | Bank name | mean | sd | skew | kurtosis | P- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO_ABC | 0.025 | 1.105 | -0.262 | 7.608 | 0.01 | CC_NBCB | 0.019 | 2.115 | -0.280 | 9.559 | 0.01 |

| SO_BOCOM | 0.011 | 1.124 | -0.631 | 8.915 | 0.01 | CC_JSB | 0.000 | 1.454 | 0.019 | 4.895 | 0.01 |

| SO_ICBC | 0.021 | 1.159 | 0.037 | 5.859 | 0.01 | CC_HZB | -0.016 | 2.114 | -5.038 | 94.335 | 0.01 |

| SO_CCB | 0.023 | 1.333 | -0.075 | 6.086 | 0.01 | CC_NJCB | -0.006 | 1.777 | -4.694 | 99.250 | 0.01 |

| SO_BOC | 0.023 | 1.074 | 0.001 | 10.264 | 0.01 | CC_BOB | -0.026 | 1.175 | -2.971 | 49.633 | 0.01 |

| JC_PAB | 0.010 | 1.954 | 0.312 | 3.063 | 0.01 | CC_BOS | -0.043 | 1.743 | -10.047 | 191.369 | 0.01 |

| JC_SPDB | -0.024 | 1.285 | -1.274 | 22.874 | 0.01 | CC_GYB | -0.049 | 1.621 | -5.789 | 141.958 | 0.01 |

| JC_HXB | -0.019 | 1.255 | -1.924 | 36.772 | 0.01 | RC_JRCB | -0.040 | 2.042 | -0.290 | 11.057 | 0.01 |

| JC_CMBC | -0.044 | 1.192 | -1.996 | 42.483 | 0.01 | RC_ZRC | -0.020 | 2.383 | 0.099 | 7.489 | 0.01 |

| JC_CMB | 0.042 | 1.820 | 0.209 | 2.380 | 0.01 | RC_WXRCB | -0.027 | 2.013 | 0.262 | 6.940 | 0.01 |

| JC_CIB | 0.012 | 1.584 | 0.108 | 4.596 | 0.01 | RC_CSRCB | -0.014 | 2.012 | 0.150 | 5.068 | 0.01 |

| JC_CEB | -0.004 | 1.324 | 0.347 | 6.705 | 0.01 | RC_SZRCB | -0.047 | 2.046 | -1.026 | 17.903 | 0.01 |

| JC_CITIC | 0.001 | 1.517 | 0.279 | 8.057 | 0.01 |

| Period | Rank | Core risk source | Risk output intensity | Rank (Path) | Key Transmission Pathway | Transmission Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-pandemic | 1 | CMB | 40.70124 | 1 | CIB→ABC | 3.294849 |

| 2 | NBCB | 39.93517 | 2 | CMB→ABC | 3.292593 | |

| 3 | PAB | 34.85628 | ||||

| 4 | CIB | 33.24386 | ||||

| during- pandemic | 1 | JRCB | 42.31553 | 1 | JRCB→CMB | 2.335893 |

| 2 | BOS | 33.98259 | 2 | JRCB→CIB | 2.326020 | |

| 3 | CMBC | 18.58274 | ||||

| 4 | SZRCB | 18.57193 | ||||

| post- pandemic |

1 | BOC | 46.10428 | 1 | BOC→CMB | 3.016431 |

| 2 | ABC | 40.39261 | 2 | BOC→CIB | 3.006325 | |

| 3 | BOCOM | 33.76634 | ||||

| 4 | CIB | 24.97696 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).