1. Introduction

Road freight transportation continues to dominate global logistics, accounting for a significantly higher share than maritime, rail, or air transport. Its flexibility and cost-effectiveness make it the preferred choice for domestic and regional goods distribution. Articulated vehicles—comprising a tractor unit coupled with one or more trailers—are the backbone of this system. However, their complex dynamics introduce critical safety challenges.

The stability of articulated vehicles has been a subject of extensive research for decades, driven by the critical safety challenges posed by their complex dynamics. Articulated configurations—such as tractor–semitrailers and multi-trailer combinations—are particularly vulnerable to instability phenomena including jackknifing, trailer sway (snaking), and rollover, which can occur under high-speed conditions, abrupt steering maneuvers, or uneven load distributions. These instability modes not only compromise vehicle control but also increase accident severity compared to single-unit vehicles [

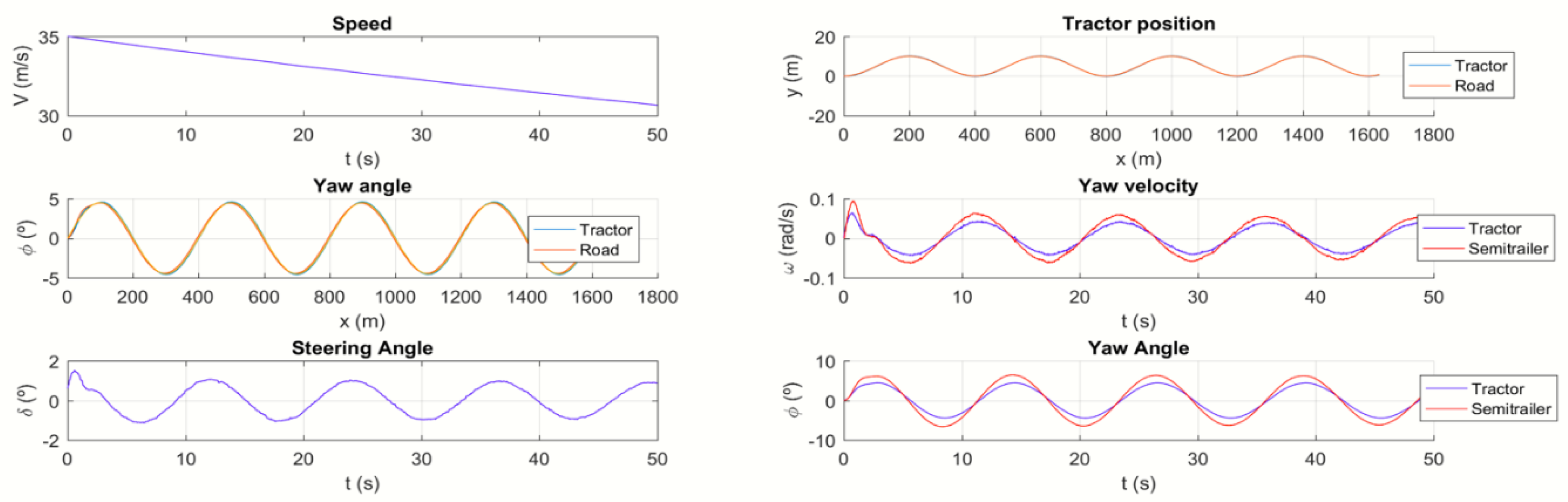

1,

2].

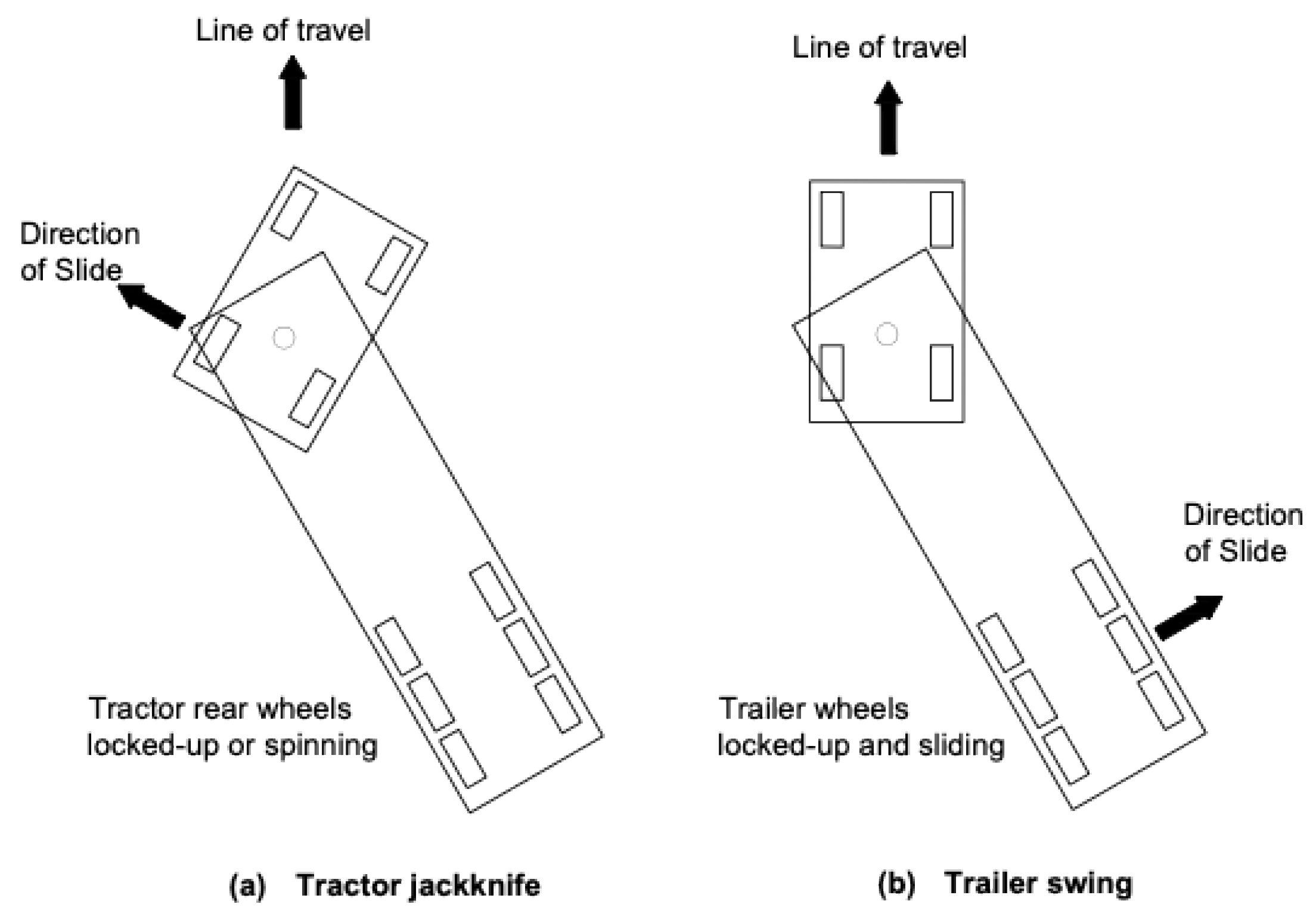

Figure 1 shows an example of these instabilities.

In general, the following types of instability may occur [

3].

The first type is divergent instability, which occurs when the mass of the trailer is partially supported by the towing vehicle at the coupling point. If the vertical force exerted by the trailer on the towing vehicle becomes excessively large, the vehicle combination exhibits a monotonically unstable motion, ultimately compromising overall stability.

The second type is unstable oscillatory yaw motion. In this case, the oscillation amplitude is unbounded, even under non-linear conditions. As the amplitude increases, the slip angle also grows, which reduces the average cornering stiffness due to the digressive, non-linear tire cornering force characteristic. This progressive reduction in cornering stiffness exacerbates the instability, making the situation increasingly critical.

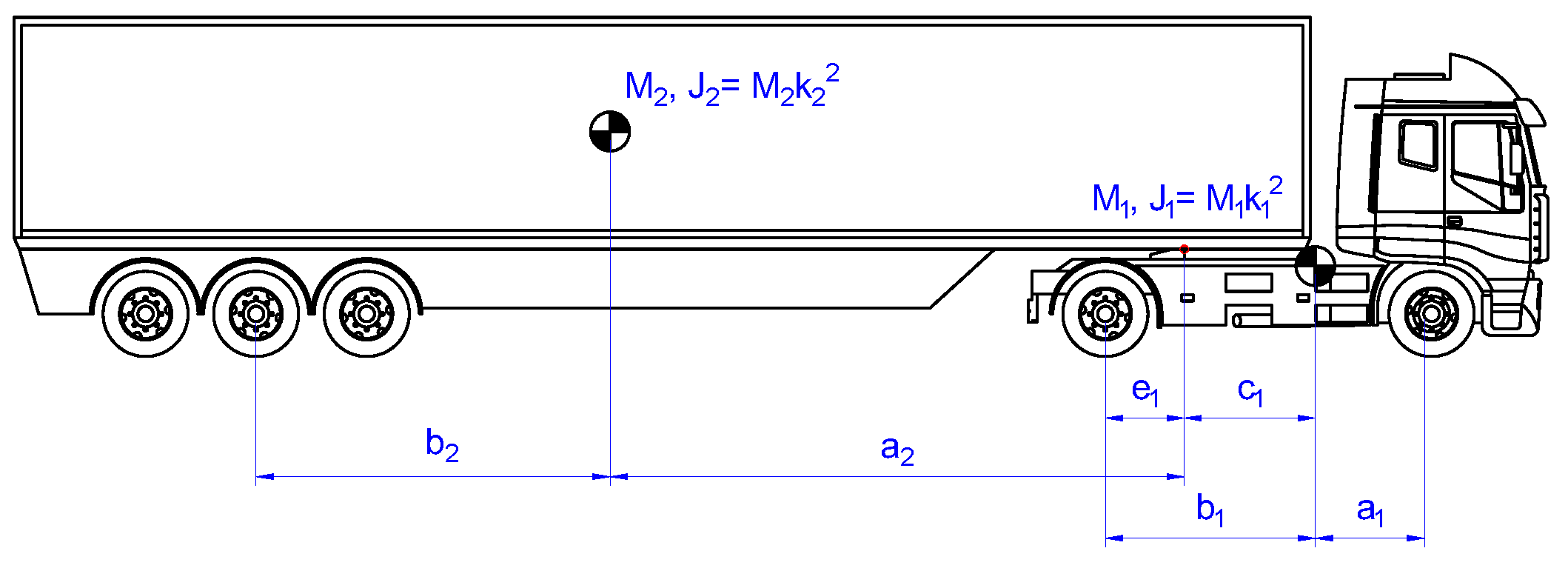

Two distinct types of trailer oscillations can be identified [

4], as illustrated in

Figure 2.

The tractor may jackknife (

Figure 2a) either under power or during braking, particularly when the rear wheels of the tractor lose grip or traction. This condition results in an acute angle between the tractor and trailer, severely compromising maneuverability and safety.

Trailer swing (

Figure 2b) may occur when the trailer axle wheels lock during braking, causing the rear of the trailer to swing outward and increasing the risk of collision. Trailer swing is often considered a form of yaw instability, even though the vehicle combination may remain mathematically stable.

A complete analysis of articulated vehicles can be found in [

5].

The progression from passive mechanical systems to active and intelligent controllers reflects the growing complexity of articulated vehicle dynamics and the demand for autonomous driving capabilities. Traditional systems such as Electronic Stability Control (ESC) and Roll Stability Control (RSC) provide reactive interventions but lack predictive capabilities, limiting their effectiveness under extreme conditions [

1].

Another significant research challenge in the automotive industry is the development of autonomous vehicles, which are defined as vehicles capable of perceiving their surroundings and replicating human driving and control abilities [

6] The degree of autonomy in a vehicle is categorized into six levels. Currently, several companies are focusing on the development of Level 4 and Level 5 vehicles [

7], although the highest level available on the market today is Tesla’s Autopilot, classified as Level 3.

The growing demand for autonomous driving technologies in heavy-duty vehicles further emphasizes the need for robust stability control systems. Autonomous articulated trucks must execute complex maneuvers without human intervention, requiring advanced control strategies that can manage nonlinear dynamics, multi-body interactions, and stringent safety constraints. Traditional stability systems, such as ESC or RSC, offer partial solutions but lack the predictive capabilities and adaptability necessary for fully autonomous operation.

With respect to the control system, the MPC is an advanced control method [

8]. This technique has been successfully used in many industrial applications, like thermal energy control [

9], collision avoidance [

10], vehicle stability [

11], and energy management [

12]. The MPC capacity of working with non-linear systems makes it appropriate for several applications in engineering, being of particular interest its use in autonomous vehicles [

13].

Several automotive companies, such as Ford, BMW, Honda, PSA, and Toyota, are actively investigating the implementation of advanced control systems. These systems have a wide range of applications, including traction control, semi-active suspension control, vehicle stability management, and energy optimization in electric vehicles. Although such control strategies typically involve high computational demands, the integration of multi-parametric programming with an appropriately designed prediction horizon can significantly reduce the computational burden on vehicle microcontrollers, enabling real-time execution in on-board systems.

The stability of articulated vehicles under high-speed conditions and emergency maneuvers has been extensively studied, leading to the development of several advanced control strategies. These approaches differ in their mathematical foundations, robustness to uncertainties, and computational requirements. Among them, MPC has emerged as the dominant methodology. MPC predicts future system states over a receding horizon and computes optimal control actions by solving a constrained optimization problem at each time step. Its ability to handle multi-variable systems and incorporate operational constraints makes it particularly suitable for articulated vehicles with complex dynamics. Studies such as [

14,

15,

16] demonstrate the effectiveness of MPC in trajectory tracking and yaw stability control. However, its main limitation lies in the high computational demand, which requires efficient algorithms for real-time implementation.

Another widely explored approach is Fuzzy Logic Control, including fuzzy PID variants. These controllers rely on linguistic rules and membership functions rather than precise mathematical models, making them robust to parameter variations and load changes. [

17,

18] highlight the intuitive design and adaptability of fuzzy controllers in managing nonlinearities. Nevertheless, their performance strongly depends on the quality of the rule base, and they may be less effective in highly dynamic scenarios compared to predictive methods.

Sliding Mode Control (SMC) represents a robust nonlinear technique that forces system trajectories to follow a predefined sliding surface, ensuring invariance to matched uncertainties. Reference [

19,

20] report that SMC provides excellent robustness against disturbances and parameter variations. Despite these advantages, the chattering phenomenon associated with SMC can lead to actuator wear and degraded performance, requiring careful design to mitigate this issue.

Optimal control strategies such as the Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) have also been applied to articulated vehicle stability. LQR minimizes a quadratic cost function to achieve optimal performance for linearized systems. Reference [

21] demonstrate its effectiveness when accurate models are available. However, its applicability is limited in nonlinear and time-varying conditions, which are common in articulated vehicle dynamics.

Adaptive Control techniques offer real-time parameter adjustment to compensate for variations in system dynamics, such as changes in payload or road conditions. References [

22,

23] show that adaptive controllers can maintain stability under varying operating conditions. The main drawback of these methods is the increased complexity associated with tuning multiple adaptive parameters.

Finally, Integrated Multi-System Control strategies combine multiple actuators—such as active front steering and differential braking—to achieve coordinated control. References [

16,

24,

25] emphasize that this approach provides superior performance in maintaining yaw and lateral stability, particularly in autonomous driving applications. However, it requires sophisticated coordination algorithms and sensor fusion to ensure seamless operation.

Table 1 summarizes the dominant control approaches identified in recent literature:

Several techniques are employed to prevent trailer jackknifing and trailer swing in articulated vehicle combinations.

A highly effective measure is ESC [

26]. ESC systems continuously monitor vehicle dynamics and intervene by applying selective braking or reducing engine torque to maintain directional stability. These interventions are particularly valuable during sudden steering inputs or slippery road conditions, significantly reducing the likelihood of both jackknifing and trailer swing.

Anti-Lock Braking Systems (ABS) also play a critical role in stability management. ABS prevents wheel lock-up during braking (Kienhöfer and Cebon 2019)[

27] , especially on trailer axles, ensuring tire-road contact and steering capability. This minimizes the risk of jackknifing and swing caused by locked wheels during abrupt deceleration.

Design improvements such as advanced fifth-wheel coupling systems [

28] with controlled articulation or damping help reduce abrupt angular changes between tractor and trailer. These systems minimize jackknife risk during sharp turns or sudden deceleration.

In addition, active trailer sway control [

29] detects oscillatory yaw motion and applies corrective braking or torque adjustments to stabilize the trailer. This technology is particularly useful for mitigating swing during high-speed lane changes or in crosswind conditions.

The choice of control parameters varies based on the instability mode being addressed. Studies targeting jackknifing prevention prioritize articulation angle control, while those addressing trailer sway focus on yaw rate deviation. Multi-objective controllers typically monitor both tractor and trailer yaw rates along with the articulation angle. These finding are summarized in

Table 2.

Across all these techniques, differential braking emerges as a critical actuator for yaw stability. This technique involves the selective application of braking forces to individual wheels or axles, generating an asymmetric braking distribution that produces a corrective yaw moment. By counteracting undesired rotational dynamics, differential braking effectively mitigates instability phenomena such as jackknifing and trailer sway. Its implementation is cost-effective because it leverages existing braking systems, making it suitable for integration with electronic stability programs. Studies such as [

1,

20] confirm that tractor-only differential braking provides significant yaw control authority, although its influence on trailer dynamics is limited. Conversely, coordinated braking on both tractor and trailer units, as demonstrated by [

14,

15], achieves superior performance, particularly at high speeds where trailer sway becomes critical.

Several advanced control strategies have been developed to optimize the use of differential braking in articulated vehicles. Among these, MPC stands out as the dominant approach due to its predictive capabilities and systematic handling of multi-variable constraints. MPC-based controllers, such as those proposed by [

14,

15], integrate trajectory tracking and yaw stability objectives within a unified optimization framework. Reference [

16] further extended this concept by coordinating active front steering with differential braking through a bi-level MPC structure, achieving enhanced path tracking and yaw control.

SMC has also been applied to differential braking systems, exploiting its robustness against disturbances and parameter uncertainties. Reference [

19] introduced a phase-portrait-based SMC method that uses differential braking to maintain dynamic stability in car-trailer combinations. Similarly, Reference [

20] implemented a multi-objective SMC algorithm for heavy tractor-semitrailers, focusing on jackknife prevention and yaw stability. Despite its robustness, SMC requires careful design to mitigate the chattering phenomenon, which can lead to actuator wear.

In addition, Fuzzy Logic Control has been employed to manage nonlinearities and uncertainties without relying on precise mathematical models. Reference [

17] demonstrated that fuzzy logic can effectively generate additional yaw moments through differential braking, improving lateral stability under varying load conditions. Adaptive Control strategies have also been explored, adjusting braking torque in real time to compensate for changes in vehicle parameters such as payload or road friction. Reference [

22] analyzed active trailer differential braking using adaptive control to prevent instability during dynamic maneuvers.

Recent research emphasizes Integrated Multi-System Control, which combines differential braking with other actuators such as active front steering and torque vectoring. Reference [

24] proposed a coordinated control strategy for distributed-drive articulated trucks, combining differential braking with steering interventions to enhance anti-jackknifing stability. Reference [

25] also investigated integrated control schemes that leverage both braking and steering for comprehensive yaw motion management.

Across all these approaches, a key finding emerges: tractor-only braking provides effective yaw control but limited trailer stabilization [

1,

20], while trailer-only braking directly mitigates trailer sway but lacks influence on tractor dynamics (Tian et al. 2025; Sun et al. 2016; 2014; Gao et al. 2020. Coordinated braking on both units delivers optimal stability, reducing articulation angle and yaw rate deviations under critical speed conditions [

14,

15,

17,

19]. These results confirm that differential braking, when combined with advanced control strategies, is a cornerstone for achieving safe and reliable autonomous operation of articulated vehicles. These results are summarized in

Table 3.

Finally, driver assistance systems and training complement these technologies. But, in the context of autonomous driving, the role of driver assistance systems evolves into fully integrated automated control architectures that replace human intervention entirely. Traditional features such as adaptive cruise control and lane-keeping assist become foundational components of advanced autonomous systems, which incorporate real-time sensor fusion, predictive algorithms, and coordinated braking strategies to maintain stability under dynamic conditions. These systems can continuously monitor articulation angles, yaw rates, and lateral accelerations, applying corrective actions such as differential braking and active trailer sway control without relying on driver input. Furthermore, machine learning-based predictive stability controllers can anticipate critical scenarios—such as sudden lane changes or low-friction surfaces—and adjust braking forces across tractor and trailer axles to prevent jackknifing or swing.

The transition from driver assistance to full autonomy eliminates the variability associated with human decision-making and reaction times, enabling precise, coordinated interventions that optimize safety margins. However, this shift requires robust redundancy in sensing and actuation systems, as well as fail-safe algorithms to handle sensor degradation or unexpected environmental conditions. Ultimately, the integration of advanced stability control strategies—such as electronic stability control, differential braking, and active sway mitigation—into autonomous platforms is a cornerstone for achieving reliable and safe operation of articulated vehicles in mixed traffic environments.

This paper contributes to the evolving field of autonomous articulated vehicle control by introducing an MPC-based steering stability system that integrates differential braking as a primary actuator. The proposed system is designed to enable autonomous trajectory tracking while preserving yaw stability under a wide range of operating conditions, including scenarios that exceed the critical speed threshold. By leveraging predictive control, the vehicle can adapt to a predefined path and execute standard driving maneuvers without human intervention.

The core innovation lies in combining yaw stability control with coordinated regulation of vehicle speed and steering angle—parameters inherently managed by autonomous driving systems. This holistic approach ensures that articulation stability is maintained during critical situations such as sudden lane changes, emergency braking, and low-friction surfaces. Differential braking, which applies unequal braking forces to individual wheels to generate corrective yaw moments, serves as the primary mechanism for stabilizing the articulated configuration under dynamic conditions.

Ultimately, the main contribution of this work is to provide “intelligence” to articulated vehicles, transforming them into fully autonomous systems capable of safe and reliable operation. Through detailed modelling and simulation, we demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed MPC-based control strategy and outline directions for future experimental validation.

The transition toward fully autonomous articulated vehicles requires control systems that go beyond conventional stability interventions. Existing studies employing MPC for yaw stability primarily focus on mitigating articulation angle deviations or preventing jackknifing through differential braking or steering coordination [

14,

15,

16]. While these approaches demonstrate the predictive capability of MPC and its effectiveness in handling multi-variable constraints, they generally address stability as an isolated objective and do not explicitly regulate longitudinal speed to maintain safe operating conditions.

The system proposed in this paper introduces a holistic control strategy that integrates trajectory tracking, yaw stability, and longitudinal speed regulation within a unified MPC framework. This design enables autonomous driving functionality by allowing the articulated vehicle to follow predefined paths while dynamically adjusting its speed to prevent instability. Unlike previous works, which intervene only when instability is imminent, the proposed controller proactively manages vehicle dynamics by predicting future states and applying corrective actions in real time. Differential braking serves as the primary actuator for yaw control, while speed regulation ensures that the vehicle remains within stability limits even under high-speed or aggressive maneuvers.

This dual capability—stability preservation and speed management—represents a significant advancement over existing MPC-based solutions. By embedding longitudinal velocity control into the optimization problem, the system not only prevents instability but also optimizes overall dynamic performance, positioning it as a key enabler for safe and reliable autonomous operation of articulated vehicles. The remainder of this paper details the modeling approach, controller design, and simulation results that validate the effectiveness of this integrated strategy.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 Material and Methods introduces the dynamic model of the articulated vehicle, including the assumptions and governing equations as well as the details of the design of the MPC-based control system.

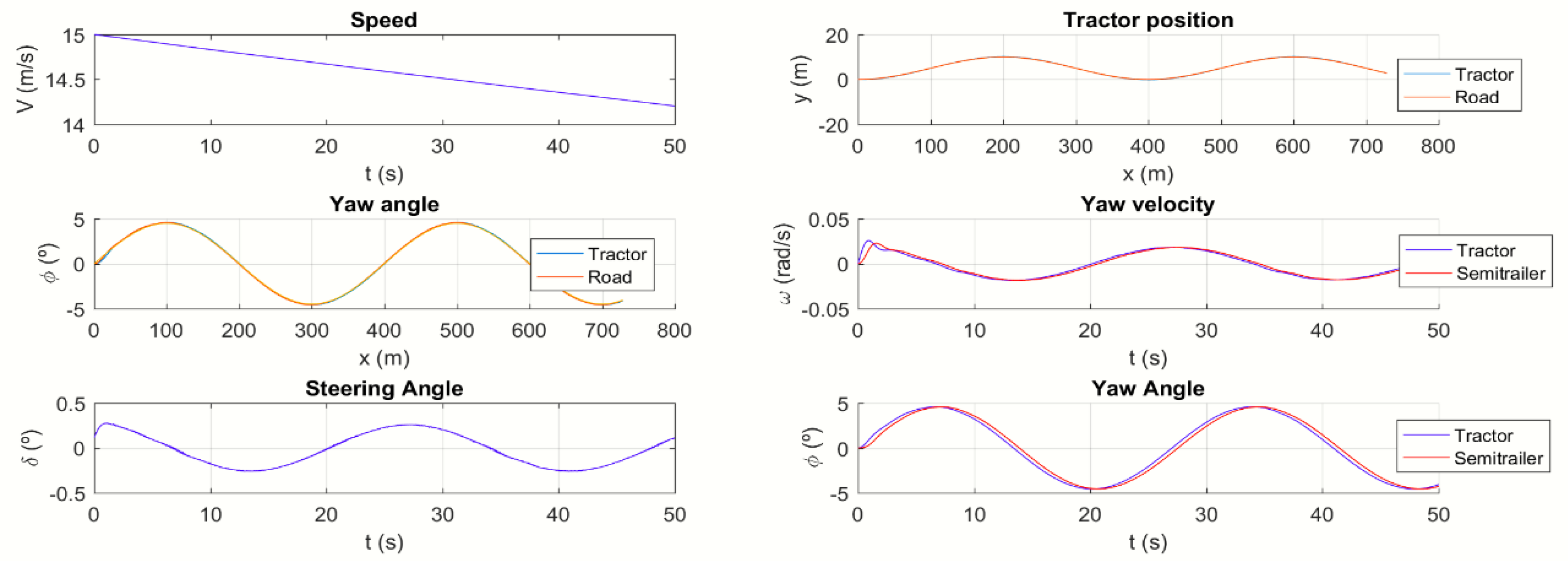

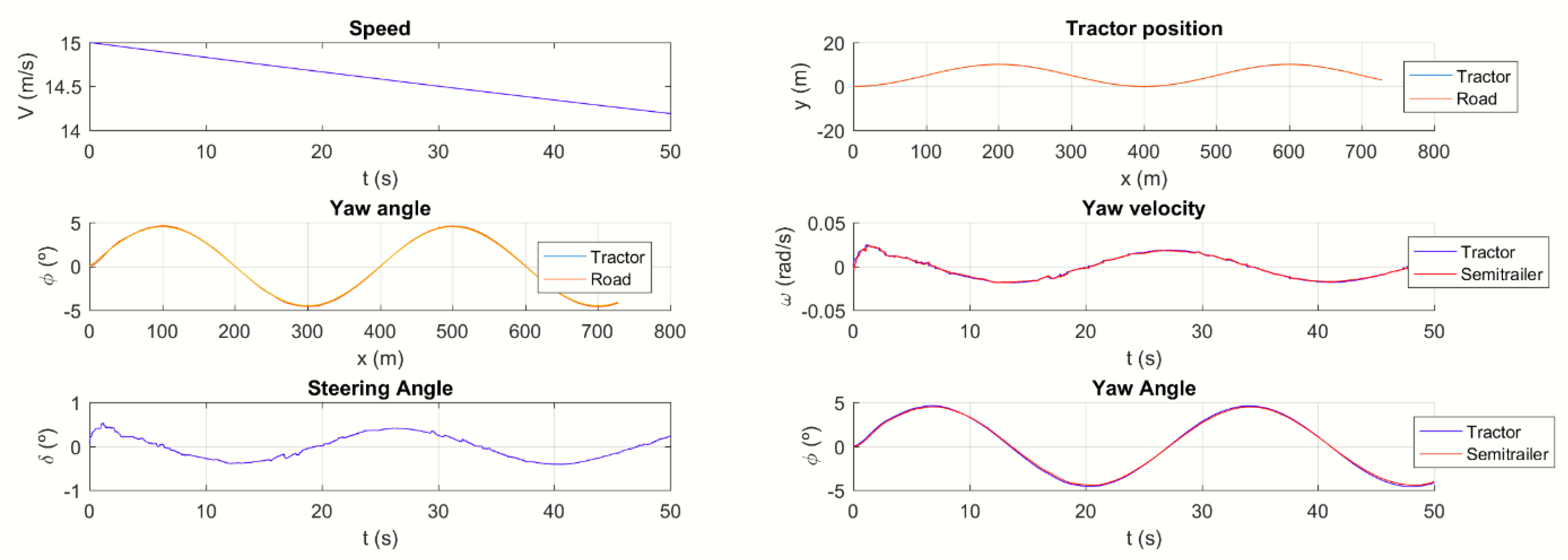

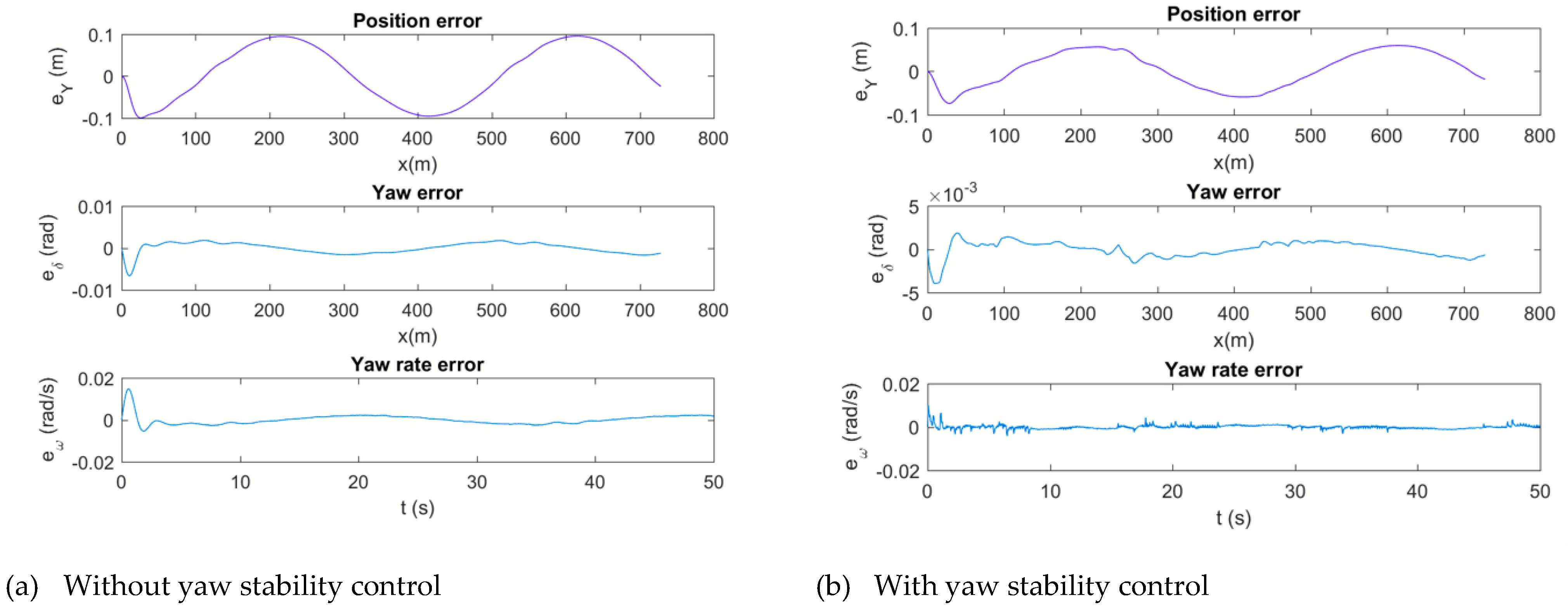

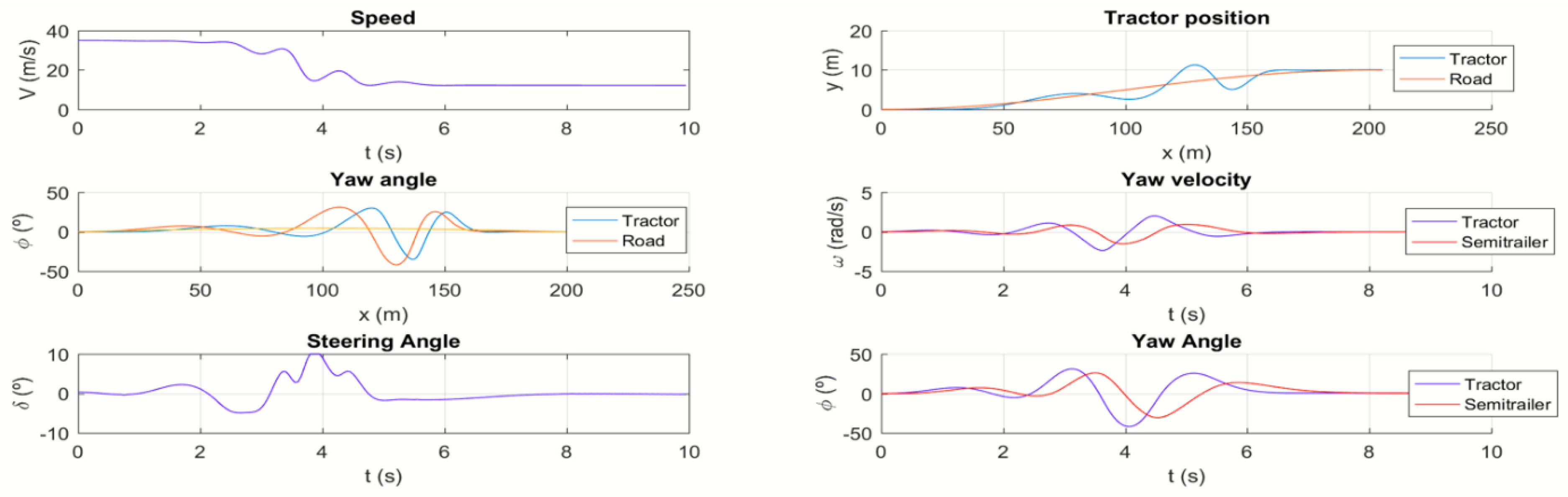

Section 3 presents the simulation results for different operating conditions, illustrating the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

Section 4 provides a discussion of the findings in the context of previous research and highlights their implications for autonomous driving. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the main conclusions and outlines directions for future work.

2. Materials and Methods

This section describes the modeling and control framework developed for this study. It begins with the formulation of a dynamic model representing the tractor–semitrailer combination, including the assumptions, degrees of freedom, and governing equations that capture the vehicle’s kinematic and dynamic behavior. Subsequently, the design of the MPC system is presented, detailing the optimization problem, constraints, and cost function that integrate trajectory tracking, yaw stability, and longitudinal speed regulation. This section establishes the foundation for the simulation-based validation of the proposed control strategy.

2.1. Dynamic Model

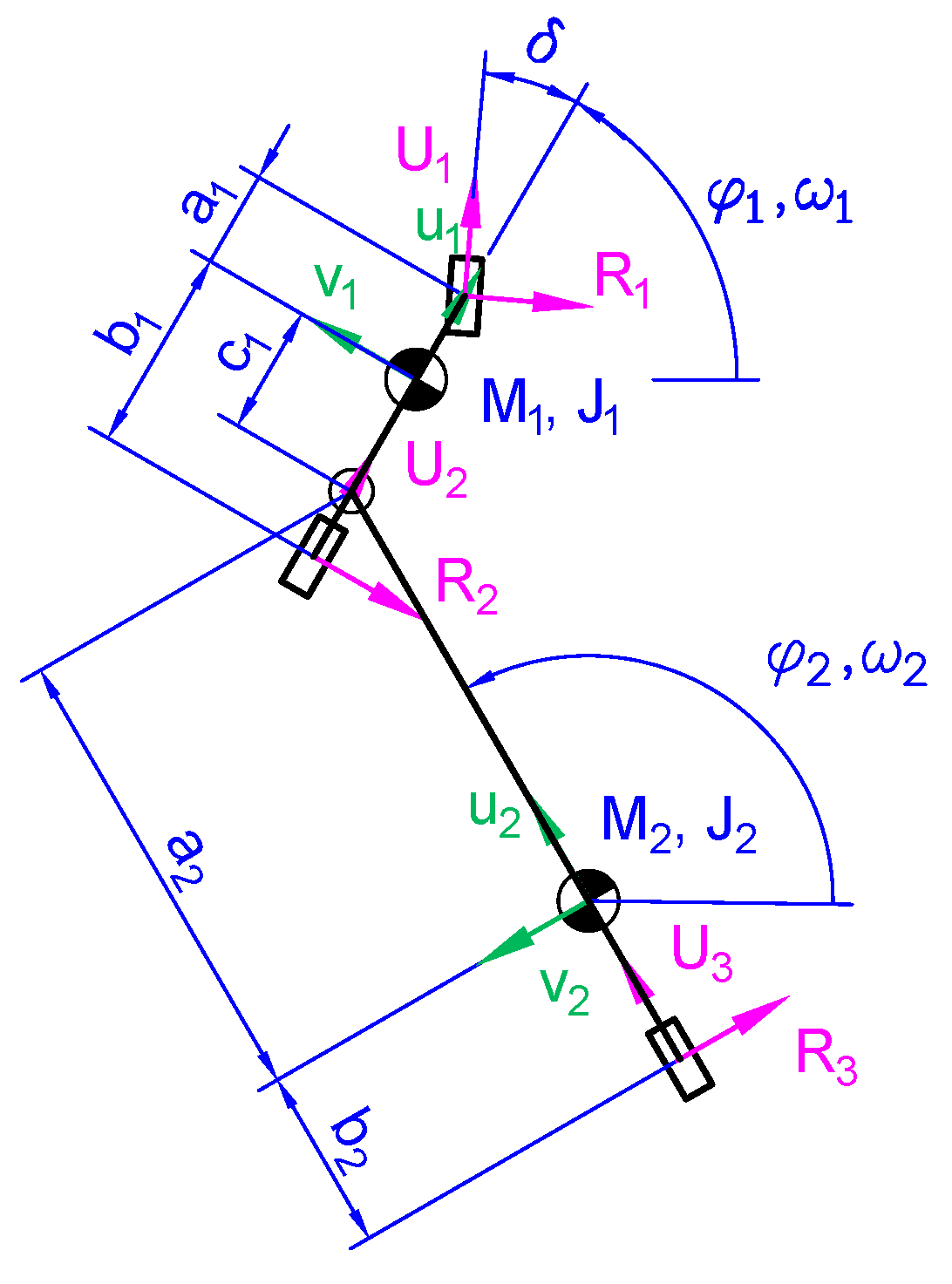

The vehicle model is composed by two bodies, tractor and semitrailer, connected with an ideal revolute joint in the kingpin. The vehicle has two axles in the tractor and three axles in the semi-trailer and has been simplified by grouping the three semi-trailer axles in only one equivalent. Each axle has its equivalent left and right wheels. The truck has the driving system in the tractor rear axle, meanwhile the steering is applied in the front wheels.

With these assumptions, the vehicle model consists of a 2D model with 4 degrees of freedom, corresponding to the longitudinal and lateral displacements of the atractor, the tractor yaw angle and the semi-trailer yaw angle.

Figure 3 shows the vehicle schematics and the parameters considered in the model. The values of the parameters used in the model are relegated to

Appendix A.

A global inertial reference frame

and two local reference frames

and

are defined. The tractor is represented as the body 1 and uses subscript 1 and the semitrailer is represented with subscript 2.

Figure 4 shows the model variables.

Capital letters represent variables referred to the global reference frame, small letters represent variables referred to the local reference frame, and Greek letters represent rotational variables. Bold letters are used to represent matrixes or vectors.

The notation is defined as follows:

with are the c.o.g. (center of gravity) positions referred to the inertial reference frame for each body.

with are the c.o.g. velocities referred to the local reference frame.

with are the orientation of the local reference frame with respect to the inertial reference frame.

means

means

means

means

means

with are the tractor and semitrailer yaw velocities.

means

is the vector of coordinates that represent the system movement in the inertial frame.

is the vector of the c.o.g. velocities referred to the local frames.

represents the constraint forces at the revolute joint, written in the global reference frame.

with (tractor, semitrailer) are resultant forces and momentum at the center of gravity (c.o.g.).

are the driving/braking forces in the front trailer axle, rear trailer axle and semitrailer axle.

are the stability controllers, introduced as differential braking, explained in

Section 2.1 Dynamic Model.

represent the lateral tire forces in the front trailer axle, rear trailer axle and semitrailer axle.

represents the tractor steering angle

The system equations can be obtained by applying the Newton-Euler’ Laws for a multibody system with kinematic constraints. These equations are obtained in the local reference frame for both bodies and can be arranged in a matrix formulation (1):

being

and, because

is in local frames (3),

Equations (1) include also the vector with two additional variables that represent the two constraint forces at the revolute joint.

The expression of the constraint equations, written in terms of velocities in the inertial frame, is as follows (4):

The matrix

in (1) has the following expression (6):

Moreover, to know the position in global coordinates, it is necessary to add the following equations (7):

And the constraint equations written in terms of velocities in the local frame, become as (8):

Then, the equations that define the vehicle dynamics (9) are a set of six differential equations in term of accelerations (1), six differential equations in term of velocities (7), and two algebraic equations (8).

These differential-algebraic equations can be optimized and reduced to a minimum set of differential equations as a function of just the degrees of freedom of the system by eliminating the algebraic constraints, as shown in [

33]

Then, two dependent velocities can be eliminated, and the equations (1) and (5) will be expressed only in terms of four independent velocities. In this case the dependent velocities chosen are the semi-trailer velocities ().

In order to do so, it is necessary to define a matrix

S, that projects all the velocities to the independent ones. This matrix can be written as:

Finally, substituting (12) into (1) and (7), and multiplying beforehand

, results in (13) and (14):

There are two types of forces and torques acting on the tractor-trailer combination.

On the one hand, are the driving/braking forces in the front trailer axle, rear trailer axle, and semitrailer axle. All of them are brake forces when the vehicle is braking, but when the truck is accelerating, only is active.

Conversely, denotes the cornering tire forces exerted by the front trailer axle, rear trailer axle, and semitrailer axle.

Finally, are the stability controllers are introduced as inputs coming from the controller in the form of torques applied the tractor and in the semi-trailer. Differential braking means that an equal and opposite increase in braking force is applied to the wheels on each side of each axle, which means that there is no additional braking increase, but there is a torque that affects the yaw movement.

The driving/braking forces are applied in the longitudinal direction of the tires, whilst the cornering tire forces are applied in the lateral direction of the tires, so the contribution to the general forces vector is shown in (15)

Lateral tire forces,

, are required to negotiate a curve. They result in tire slip angles. This tire characteristic is linear for small slip angles. The gradient of the curve in the linear regime is the tire cornering stiffness,

A normalized cornering stiffness is used to study the effect of scaling the tire cornering stiffness linearly with vertical load on dynamic stability. It was found in [

34] that, in contrast to passenger car tires, the relation between the tire cornering stiffness and vertical load is nearly linear for truck tires and that the characteristic shows an even more linear relationship if dual tires are applied, which is often the case in truck configurations, except for the steered axle.

This means that the assumption that the cornering stiffness versus load characteristic is in its linear region is often true for truck tires.

The cornering stiffnesses are calculated as function of vertical load, with

using expressions in (16) and (17)

with:

The lateral tire forces

are obtained from the slip angle

, that depends on the relation between the lateral and longitudinal wheel speed on the ground contact point, according to the following expressions (18) by multiplying the slip angle by the cornering stiffness

:

The model assumes small steering angles, so and .

Then, the final equations result as in (19)

2.2. Design of the MPC Controller

This section presents the formulation of an optimization problem aimed at designing controllers that guide the vehicle and maintain yaw stability. The optimal control design is derived from the dynamic model of the trailer. The control inputs considered include the driving and braking forces at each axle, the steering angle, and the torque associated with differential braking for yaw stability control. Operational constraints are imposed by defining permissible limits for both inputs and outputs. Additionally, an objective function is introduced to capture the goals of the control problem: tracking a desired trajectory while ensuring yaw stability.

2.2.1. Optimal Control Design

Regrouping the previous expression (19) the system equations for the vehicle dynamics are written in a compacted way as (20):

where:

is a vector including the states.

is vector with the independent velocities.

includes the global positions and orientations for tractor and semitrailer.

is a vector including the inputs.

An MPC approach is proposed for the vehicle. MPC is selected due to its capability of systematically handling multiple input and state constraints, which in this problem are critical. According to the receding horizon principle, at each time step the MPC algorithm computes the optimal control and state trajectories solving a finite horizon optimization problem.

For the formulation of the MPC a prediction horizon is considered at time t. The notation represents the state vector at time , predicted at time , obtained by starting from the current state , and where denotes the unknown input variables to be optimized. As previously stated, the subscript 1 denotes the tractor and subscript 2 denotes the semitrailer.

2.2.2. System Dynamics

Equations (21) represents the system dynamics updates for the discrete-time model obtained from (20). The initial state is set in (22)

2.2.3. Constraints

The controlled inputs include the driving and braking forces at each axle, the steering angle, and the torque representing differential braking for yaw stability control.

The driving and braking forces must be bounded by:

The driving / braking forces constraints include the limitation of the maximum driving and braking force and the power limitation in driving and braking. (23) to (26) represent the maximum driving/braking forces and the maximum power for driving/braking. Equation (23) and (25) are bounded between because axles 1 and 3 only break, instead of axel 2 (24), bounded between because in this axle, we have de traction.

Constraints (27) and (28) bounds the steering angle and the steering rate.

And constraints (29) constraints the differential braking stability controllers

In the MPC formulation, we will refer to all these constraints as .

In order to guarantee that the vehicle respects the speed limit, the speed is bounded by the following constraint (30):

In the MPC, we will refer to this constraint as .

2.2.4. Cost Function

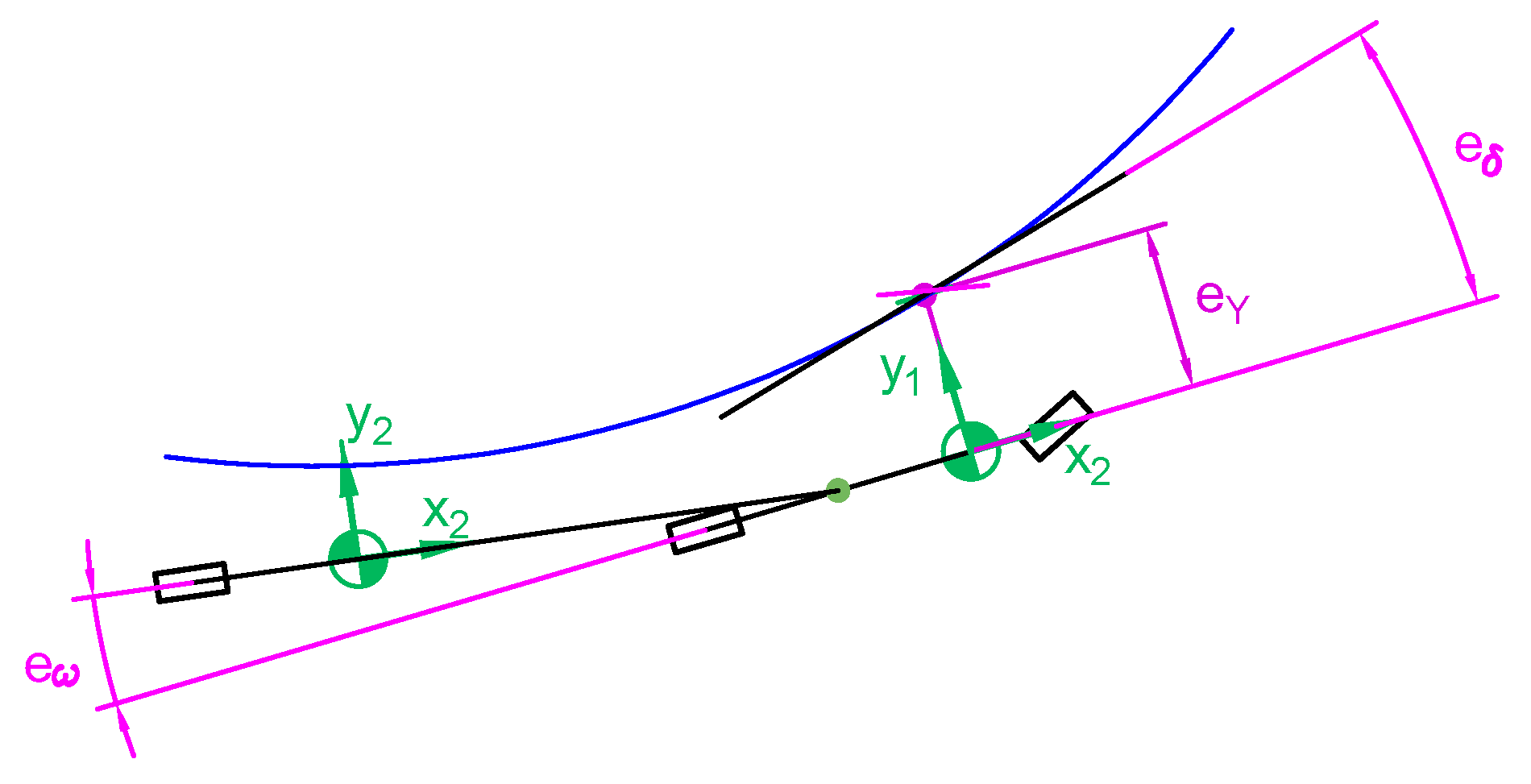

The objective of the truck is to circulate at the speed fixed by a reference, following a trajectory previously define, and preserving yaw stability. The objective control may be stablished with an objective function composed by different terms. This objective function is used to minimize the different errors produced in the trajectory tracking and in the relative yaw rate, as shown in

Figure 5.

Therefore, the objective function

(31) is defined as follows:

with

The different terms in the cost function (31) to (34) have the following meaning: represents the weight penalizing the output deviation from the truck maximum desired speed, being the maximum desired speed. represents the weight penalizing the lateral displacement in the trajectory tracking, being the Y coordinate of the desired trajectory. represents the weight penalizing the orientation in the trajectory tracking being the orientation of the desired trajectory.

The term (34) is the key point in the yaw stability control. This term minimizes the yaw rate between tractor and semitrailer, so it preserves the yaw instability.

2.2.5. Model Predictive Control Formulation

As previously said, the objective of the truck is to circulate at the speed fixed by a reference, following a trajectory previously define, and preserving yaw stability.

Therefore, the optimization problem is formulated as (35) – (39):

subject to:

The resulting optimal states and inputs of (35) – (39) are denoted as following:

For closing the loop, the first input is applied to the system (20) during the time interval

At the next time step t+1, a new optimal problem in the form of (35) – (39) is solved over a shifted horizon, based on a new states’ measurement.