1. Introduction

Sarcoma cancers including chondrosarcomas (CS), the most common form of bone cancer, can be extremely aggressive with high mortality rates. Therapeutic options for CS have not advanced in the last few decades, where resistance to chemo- and radiation therapy remains, with surgery being the treatment regimen of choice for primary tumors. CS have been shown to harbor genetic mutations in either isocitrate-dehydrogenase 1 (

IDH1) or 2 (

IDH2) [

1]. When present, mutant IDH1 and IDH2 confer a cellular gain-of-function by converting alpha-ketoglutarate (αKG) produced by wild type IDHs, to D-2-hydroxyglutarate (D2HG), a potent oncometabolite. Conversion of αKG to D2HG by mutant IDH1 occurs in the cytosol whereas conversion by mutant IDH2 occurs in the mitochondria as part of the Krebs Cycle [

2]. Mitochondria are key players in cancer progression, specifically, through involvement in oncogenicity, immune evasion, and resistance to therapies (e.g., chemo-and-radiation therapy) [

3,

4]. Mitochondrial transfer, once considered a rare or compensatory mechanism, has emerged as a prominent phenomenon in both physiological and pathological contexts. Mechanistic studies have identified tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) as one vehicle through which mitochondria can move between cells and alter recipient cell behavior [

5,

6]. TNTs are F-actin-rich cytoplasmic connections that enable the direct trafficking of organelles over considerable distances, with their formation encouraged by stressors such as hypoxia or chemotherapy. In cancer cells, increased levels of Miro1, a mitochondrial Rho-GTPase, along with actin remodeling proteins, aid in TNT formation and the movement of mitochondria [

5,

7,

8]. Mouse bone marrow stromal cells can convey mitochondria to T cells, boosting their metabolic functions and anti-tumor activities [

9], suggesting that mitochondrial transfer influences not only cancer progression but also immune responses. In both solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, mitochondria passed from endothelial or stromal cells may shield cancer cells against oxidative stress and enhance therapy resistance [

10].

The impact of this phenomenon in cancer, where transferred mitochondria can modulate energy metabolism, redox status, and immune responses in the tumor microenvironment [

11,

12] is particularly salient in cancers with IDH2 mutations where D2HG producing mitochondria transferred to normal recipient cells will expose recipient cells to epigenetic and metabolic dysregulation [

13,

14]. Although most studies on IDH mutations have focused on cell-autonomous effects, emerging work suggests that IDH2 mutant mitochondria may be capable of transmitting these epigenetic and metabolic aberrations to neighboring cells via mitochondrial transfer. This hypothesis is supported by the convergence of data on D2HG’s ability to inhibit α-KG–dependent dioxygenases and the demonstrated capacity of mitochondria to retain and shuttle such metabolites into recipient cells [

15,

16]. Tumor cells with IDH mutations export intracellularly accumulated D2HG into the microenvironment and confer growth advantages to tumor cells through suppressing anti-tumor activity of immune cells. Recently, the solute carrier family (SLC22) has been shown to be present in the mitochondrial membrane and transport D2HG across the cell membrane. SLCs are present in both the cell and plasma membranes of organelles (Genecards.org) and may play a role in the mitochondrial transport of D2HG out of mitochondria [

17,

18].

Despite these advancements, gaps remain in our understanding of how transferred mitochondria can reprogram recipient cells. This is especially true in the context of immune cell interactions, where relatively few studies have dissected how mitochondrial uptake alters cellular immunity or tolerance [

19]. Standardized models, including those utilizing cancer cell lines such as IDH2 mutant chondrosarcoma cells (SW1353) and primary stromal cells, are necessary to elucidate these mechanisms under conditions that mimic the tumor microenvironment. Moreover, the lack of robust quantification methods and the challenge of distinguishing true transfer events from dye artifacts continue to complicate interpretation across studies.

This research framework provides a compelling rationale for the investigation of mutant mitochondrial transfer and its downstream consequences. The integration of metabolic, epigenetic, and immunological perspectives offers a more holistic understanding of tumor progression and intercellular crosstalk. Continued exploration of these processes, especially through co-culture models and high-resolution flow cytometry, holds promise for uncovering novel mechanisms of tumor-host interaction and potentially new therapeutic targets.

2. Methods

2.1. Approvals and Biosafety Compliance

All experimental work was conducted in ODU BSL-2 facilities in accordance with institutional policies and applicable regulations. The ODU Biosafety Committee approved all work on this project (IBC protocol #24-015). No human subjects or primary patient materials were involved beyond established cell lines; standard chemical and biological waste procedures were followed.

2.2. Cell Culture

Five human-derived cell types were used: SW1353 (IDH2 mutant) (ATCC) and JJ012 (Wild type IDH2/mutant IDH1 kindly provided by Dr. Block, Rush Medical Center, Chicago, IL) chondrosarcoma cells, primary fibroblasts (ATCC) and primary chondrocytes (Promocell), and a normal lymphoblastoid B cell line (N-LCLs) (Corielle Institute for Medical Research). Chondrosarcoma, chondrocyte, and fibroblast cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen), 50 IU/mL penicillin (Invitrogen), and 50 µg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen). N-LCL cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with the same supplement concentrations and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO₂ in air.

Cocultures were established in 8-chambered incubation chambers with glass bottoms (0.15 mm thickness), which were selected to enhance optical clarity and resolution during microscopy. For SW1353:N-LCL cocultures, SW1353 cells (30,000–35,000 cells) were seeded into the chambers and allowed to attach overnight before the addition of an equal number of N-LCLs directly on top of the adherent SW1353 monolayer. Cocultures were incubated for 12–24 hours before imaging, ensuring sufficient time for TNT formation and potential mitochondrial transfer, while avoiding overgrowth or degradation of the dye signal.

2.3. Mitochondrial Staining

Experiments used MitoBright Green (Dojindo Molecular Technologies) to label SW1353 mitochondria and BioTracker Red (Sigma) to label N-LCL mitochondria. Both dyes were mitochondrial-specific and demonstrated stable fluorescence retention for up to 6–7 days post-staining under standard culture conditions. Working dilutions were empirically optimized to balance signal intensity and background fluorescence and ranged from 1:200 to 1:500 for MitoBright Green and from 1:200 to 1:2500 for BioTracker Red, depending on whether the experiment was designed for microscopy or flow cytometry. Staining was carried out by incubating cells in complete medium containing the appropriate dye for 30 minutes at 37 °C, followed by two washes with pre-warmed medium. All mitochondrial staining procedures were performed on sub-confluent cultures to preserve healthy mitochondrial morphology, and paired coculture conditions were always stained in parallel to minimize variability between samples. SW1353 cells were consistently labeled with the green mitochondrial dye, and N-LCL cells were labeled with the red mitochondrial dye.

2.4. Nuclear Staining

Following mitochondrial staining, cells were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 1 µg/mL in complete medium for 10 min at 37 °C. Cells were then washed twice in pre-warmed medium before imaging. Nuclear staining was used to confirm cell counts, visualize nuclei for coculture identification, and assess cell health.

2.5. Microscopy and Image Acquisition

Imaging was performed on the Leica TCS SP8 using filter sets for Hoechst (nuclei), green mitochondrial dyes (MitoBright Green), and red mitochondrial dyes (BioTracker Red). Phase contrast or DIC images were acquired alongside fluorescence channels to visualize TNT morphology. Images were collected from multiple random fields per chamber well and adjusted for brightness/contrast in Leica LasX software without altering relative fluorescence intensities between samples.

2.6. Mitochondrial Metabolism

Mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were assessed using the Seahorse XFp Analyzer (Agilent) using XFp 8-well miniplates following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Briefly, the XFp sensor cartridge was hydrated overnight (≥12 h) at 37 °C in a non-CO₂ incubator using Seahorse Calibrant. On the day of the assay, cells were seeded into XFp miniplates at densities pre-optimized for monolayer uniformity and signal linearity (SW1353 ~15,000 cells/well). Due to the difference in size of N-LCLs compared to SW1353, the ideal seeding concentration for N-LCLs was determined to be ~100,000 cells/well.

2.7. Data Processing and Normalization

Data was processed in Agilent Wave Pro software v10.1.0, applying background correction and default instrument algorithms. To account for well-to-well variation, values were normalized to cell number (post-run nuclei stain, e.g., Hoechst/DAPI + imaging count), keeping the normalization method constant within an experiment. In SW1353 wells, ~600 cells were counted and normalized to pmol/103 cells. In N-LCL wells, ~5000 cells were counted and normalized to pmol/103 cells. From OCR traces we derived: basal respiration, ATP-linked respiration (pre-vs post-oligomycin), proton leak, maximal respiration (FCCP), and spare respiratory capacity; from ECAR we tracked basal acidification and stress-induced changes as a proxy for glycolytic flux.

2.8. Flow Cytometry

All cocultures and separate controls were incubated for approximately 12–16 hours before analysis. Cells were harvested the following morning, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and analyzed using the MACSQuant® Analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec). Green fluorescence was detected on the FITC channel (525/50 nm), and red fluorescence was detected on the B4 channel (576/26 nm), corresponding to the emission spectra of MitoTracker Green and Mitotracker Red FM, respectively. Data was exported and analyzed using FlowJo software (BD Biosciences).

2.9. Optimization and Final Protocol (BD FACSAria)

Subsequent flow cytometry experiments were conducted using the BD FACSAria™ III cell sorter (BD Biosciences) to analyze mitochondrial transfer with improved dye stability and multi-day coculture compatibility. These experiments employed MitoBright Green (Dojindo) to label SW1353 chondrosarcoma cell mitochondria and BioTracker Red (Sigma) to label N-LCL B lymphocyte mitochondria, as described in

Section 2.X (Fluorescent labeling of mitochondria and live-cell imaging). The choice of these dyes was based on their demonstrated ability to retain fluorescence for 6–7 days, in contrast to the 24-hour signal stability of the MitoTracker dyes used in the initial MACSQuant runs. Cocultures and controls were prepared in suspension at a total of 1 × 10⁶ cells per tube in PBS. Coculture samples contained equal proportions of each cell type (5 × 10⁵ SW1353 cells and 5 × 10⁵ N-LCLs). Concentrations for each cell type were as follows: N-LCL at 1:200 Biotracker Red and SW1353 at 1:2500 MitoBright Green. Flow cytometry was performed in analysis mode, with green fluorescence detected in the FITC channel (excitation: 488 nm, emission: 530/30 nm) and red fluorescence detected in the PE-Cy5 channel. Data acquisition was carried out using BD FACSDiva™ software, and results were analyzed in FlowJo™ (BD Biosciences).

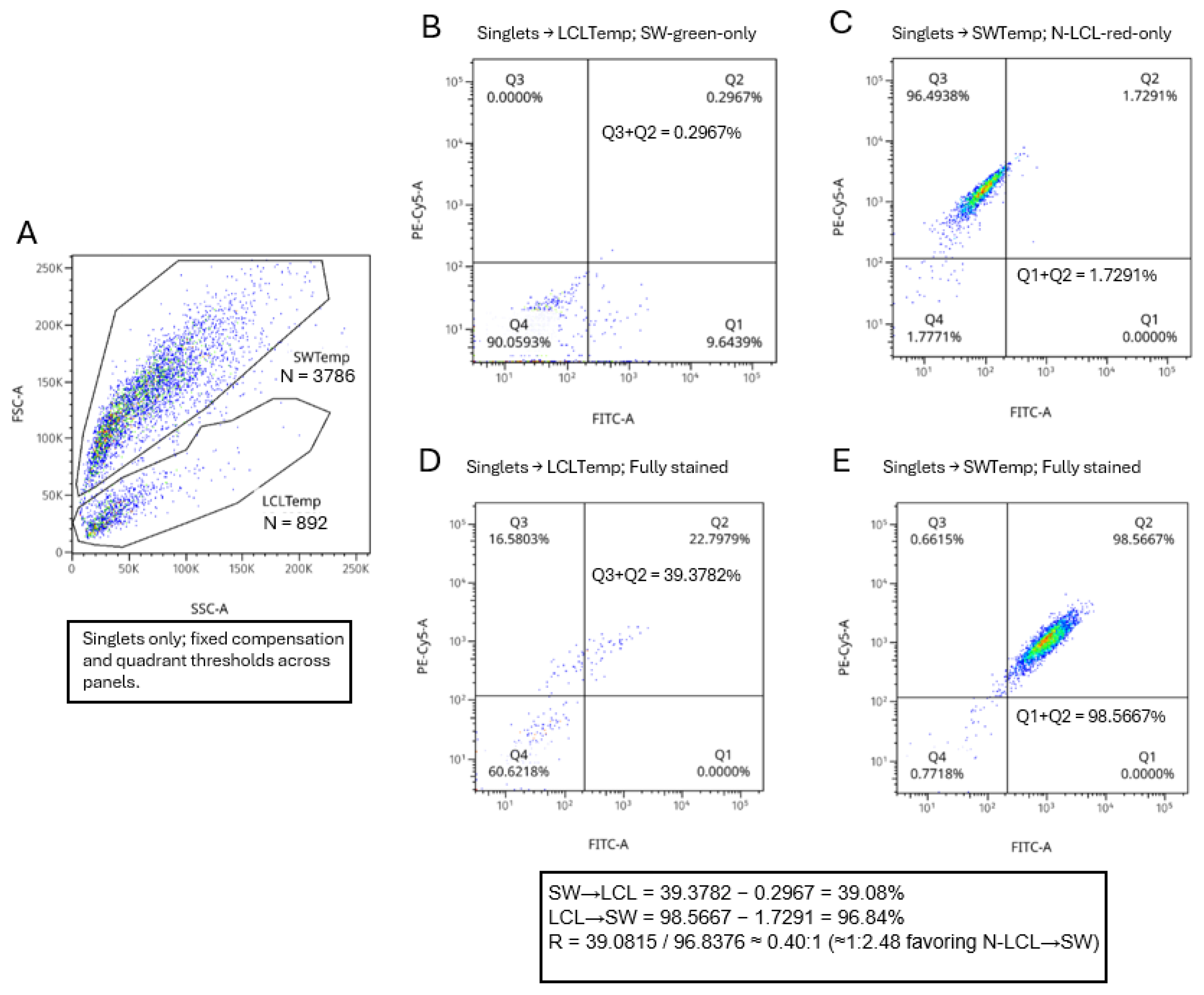

2.10. Directionality Estimation by FSC/SSC Template Gating with Quadrant Readout

To infer the direction of mitochondrial transfer without antibody-based cell identification, we used a two-stage gating workflow in FlowJo with fixed PMT voltages, and a single compensation matrix applied to all tubes. Debris was excluded on FSC-A vs SSC-A, followed by singlet discrimination on FSC-A vs FSC-H (and SSC-A vs SSC-H as needed). All downstream analyses were performed within the singlet gate.

On FSC-A (Y) vs SSC-A (X) plots of the unstained coculture, two conservative polygon templates were defined to capture the two size/granularity ridges while leaving a low-density gap between them: LCL template (low-FSC, low–mid-SSC) and SW1353 template (high-FSC, high-SSC). Template boundaries were finalized on the unstained coculture and then applied unchanged to all tubes in the experiment.

2.11. Cytochalasin B Treatment and Flow Cytometric Analysis of Cocultures

Cytochalasin B dissolved in DMSO was used at a final working concentration of ~10 µg/mL (20.8 µM) at ~0.10% v/v DMSO. Vehicle controls received 0.10% DMSO without drug.

Following staining, SW1353 and N-LCL cells were combined at a 1:1 ratio to establish cocultures. At coculture initiation, either cytochalasin B (as above) or an equivalent volume of its vehicle control (e.g., DMSO) was added, and cultures were incubated for six hours in standard conditions. Because cytochalasin B’s effects are transient in these cultures, incubation was limited to 6 h; overnight exposures were avoided. Cells were then gently collected (adherent cells with minimal enzymatic dissociation; suspension cells by centrifugation), washed, and resuspended in PBS for analysis. In parallel with flow analysis, replicate cocultures were imaged by confocal microscopy on a Leica system controlled with LAS X software to assess TNT formation and the presence of cross-cell mitochondrial signal under vehicle versus cytochalasin B conditions. SW1353 mitochondria (green) and N-LCL mitochondria (red) were acquired as single optical sections per field at the focal plane of the maximal cell-cell contact, with laser power, detector gain, pinhole, and exposure held constant across all groups. Single-stain controls were used to set channel exposure and to evaluate spectral bleed-through; where applicable, channels were captured sequentially. TNTs were operationally defined as thin, continuous protrusions connecting two distinct cells.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was determined by Welch’s unpaired t-test using GraphPad software. p < 0.05 reflect significance.

3. Results

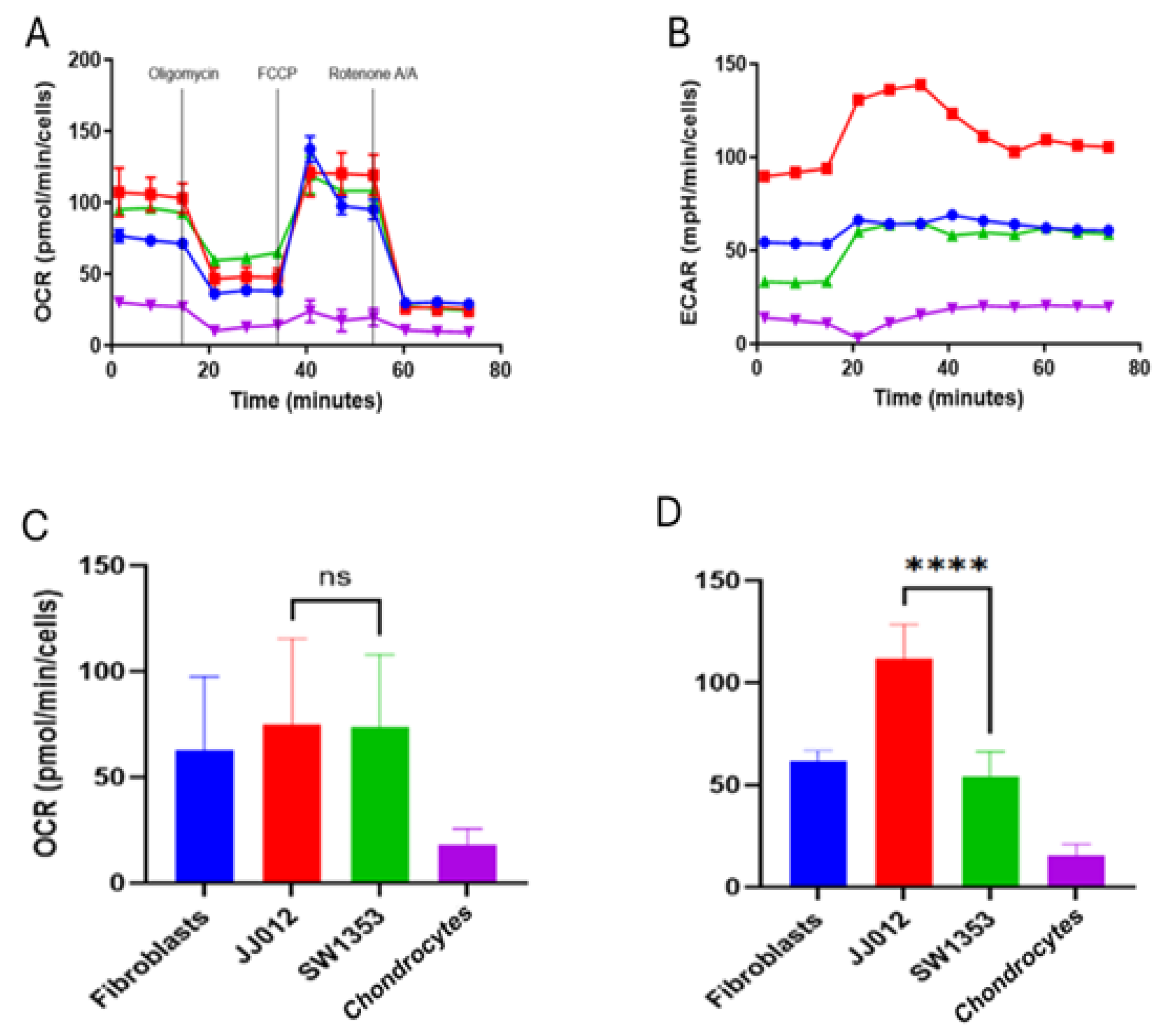

3.1. Metabolic Analysis Distinguishes Respiratory and Glycolytic Phenotypes

Initially, we set out to determine the metabolic profile of the IDH2 mutant chondrosarcoma line SW1353 compared to an IDH2 wild-type chondrosarcoma line (JJ012, IDH1 mutant) and two normal human primary cell types, fibroblasts and chondrocytes. Primary cells were chosen as potential cell types a chondrosarcoma could interact with in its tumor microenvironment. Across lines, the XFp Cell Mito Stress Test produced the expected response profile: OCR fell after oligomycin, rose with FCCP to reveal maximal respiration, and dropped to near baseline after rotenone/antimycin A. At the optimized seeding density (~15,000 cells/well) and with values normalized to per-well cell counts, basal and FCCP-stimulated OCR were broadly comparable among fibroblasts, JJ012, and SW1353, with chondrocyte wells remaining low (

Figure 1). The chondrocyte profile is consistent with their quiescent, low-demand phenotype in 2D culture: primary chondrocytes have fewer mitochondria, lower ATP turnover, and adapted to the low-oxygen, avascular cartilage niche, so per-cell oxidative and glycolytic fluxes are modest compared with proliferative fibroblasts and glycolysis-biased tumor lines. With matched seeding and cell-count normalization, the low rates are likely to reflect true per-cell metabolism rather than differences in cell numbers. Summary bars recapitulated this pattern, showing overlapping means and variability for OCR across cell types within this preliminary dataset (

Figure 1).

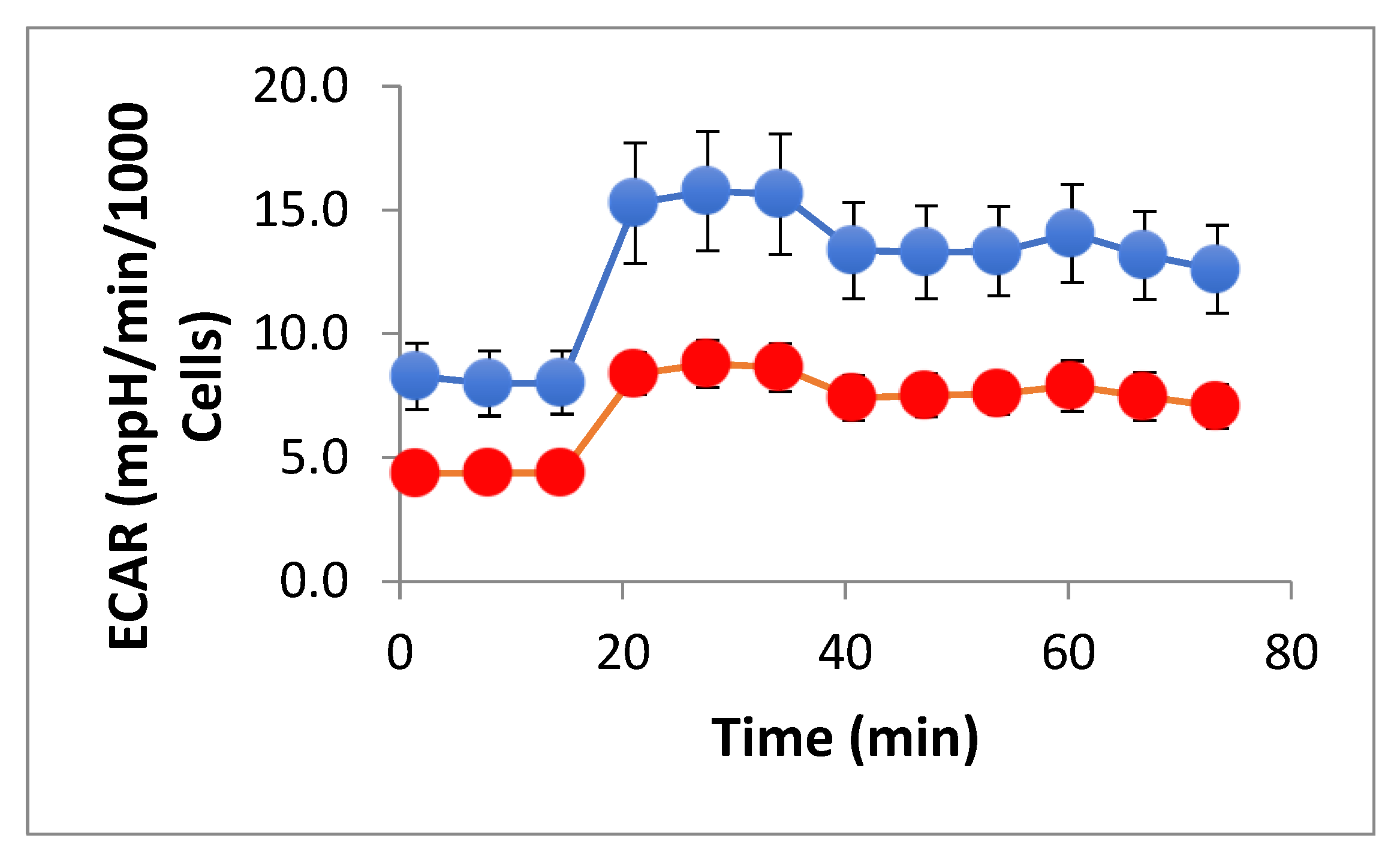

In contrast, ECAR differed markedly by line. JJ012 exhibited a higher basal ECAR and sustained acidification throughout the assay window relative to SW1353 and fibroblasts, consistent with a more glycolytic phenotype under these conditions. Chondrocyte values were low under all conditions, reflecting the low metabolic rate of these cartilage producing cells. This pattern was evident in the time-course traces and reflected in the ECAR summary bars. All assays were processed with identical instrument settings and normalized to cell number; no additional transformations were applied. (Data is expressed as mean ± standard deviation; ns denotes none-significance).

Although primary chondrocytes and fibroblasts are cells a chondrosarcoma may encounter, the presence of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment and the loss of immunosuppressive function is crucial, particularly in respect of resistance to chemo-and-radiotherapy exhibited by chondrosarcoma. Our interest became focused on the potential immunomodulatory response IDH2 mutant mitochondrial transfer may have and utilized normal B-cell lymphoblastoid cell lines (N-LCL) as they offer a good model for studying immune cell interactions. LCLs are human B-lineage cells with robust mitochondrial content and well-characterized immune signaling, giving a controlled, reproducible “immune-adjacent” partner to model tumor–immune crosstalk without the variability of primary cells. Since bidirectional mitochondrial exchange between cancer and immune cells has been implicated in blunting anti-tumor immunity, an LCL provides a tractable system to define directionality, triggers, and consequences of transfer (e.g., antigen presentation or cytokine responses).

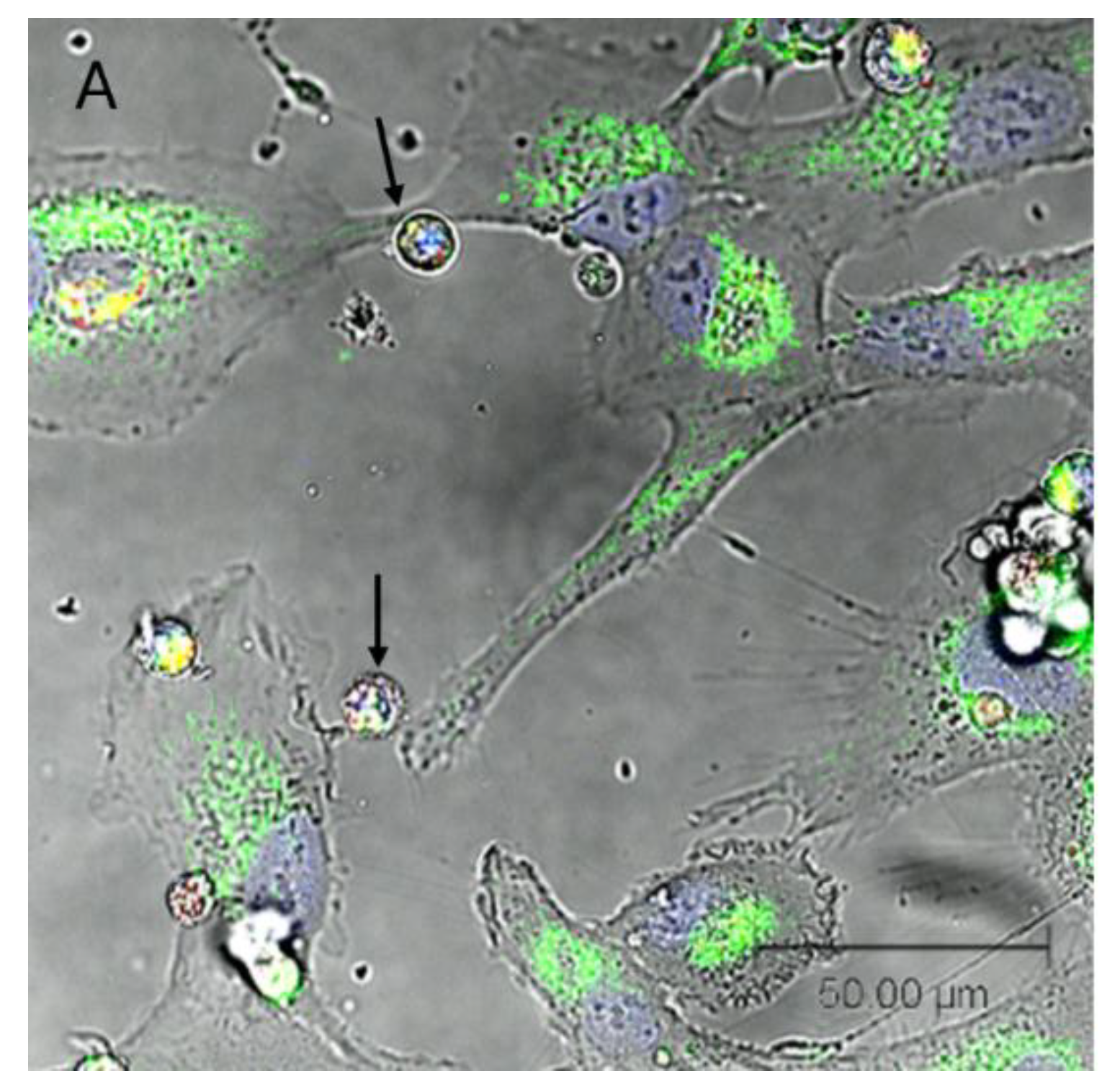

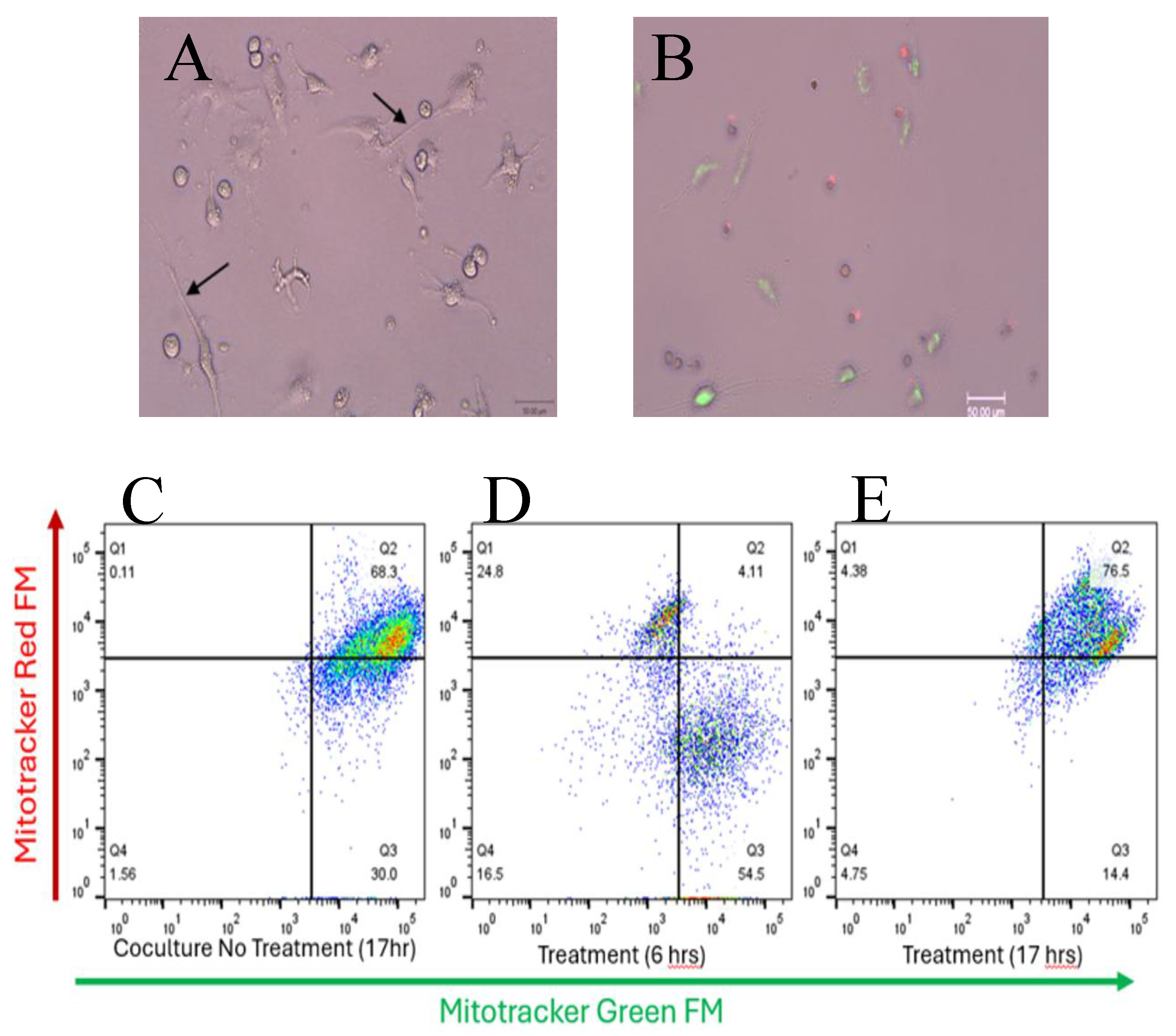

3.2. Confocal Microscopy Reveals Bidirectional Mitochondrial Transfer Between SW1353 and N-LCL Cells

Single-plane confocal imaging of SW1353:N-LCL cocultures showed thin, continuous protrusions spanning intercellular gaps morphologically consistent with tunneling nanotubes (TNT-like structures). With SW1353 mitochondria labeled green and N-LCL mitochondria labeled red, both colors were frequently present within these protrusions and in opposing cell bodies, suggesting exchange of mitochondrial material within the imaging window. TNT-like structures were distinguished from broad lamellipodia and closely apposed membranes by their narrow caliber, continuity, and elevation above the substrate. Representative fields are shown in

Figure 2.

Qualitatively, TNT-like projections were common at 12–24 h of coculture. A media-transfer (dye-leakage) control remained negative (no labeling of previously unstained cells), supporting the interpretation that detected fluorescence reflected on-mitochondrion signal rather than free dye. Because images were collected as single optical sections (no z-stacks), counts are conservative and focus on clearly resolved TNT-like structures and observational confirmation of bidirectional transfer.

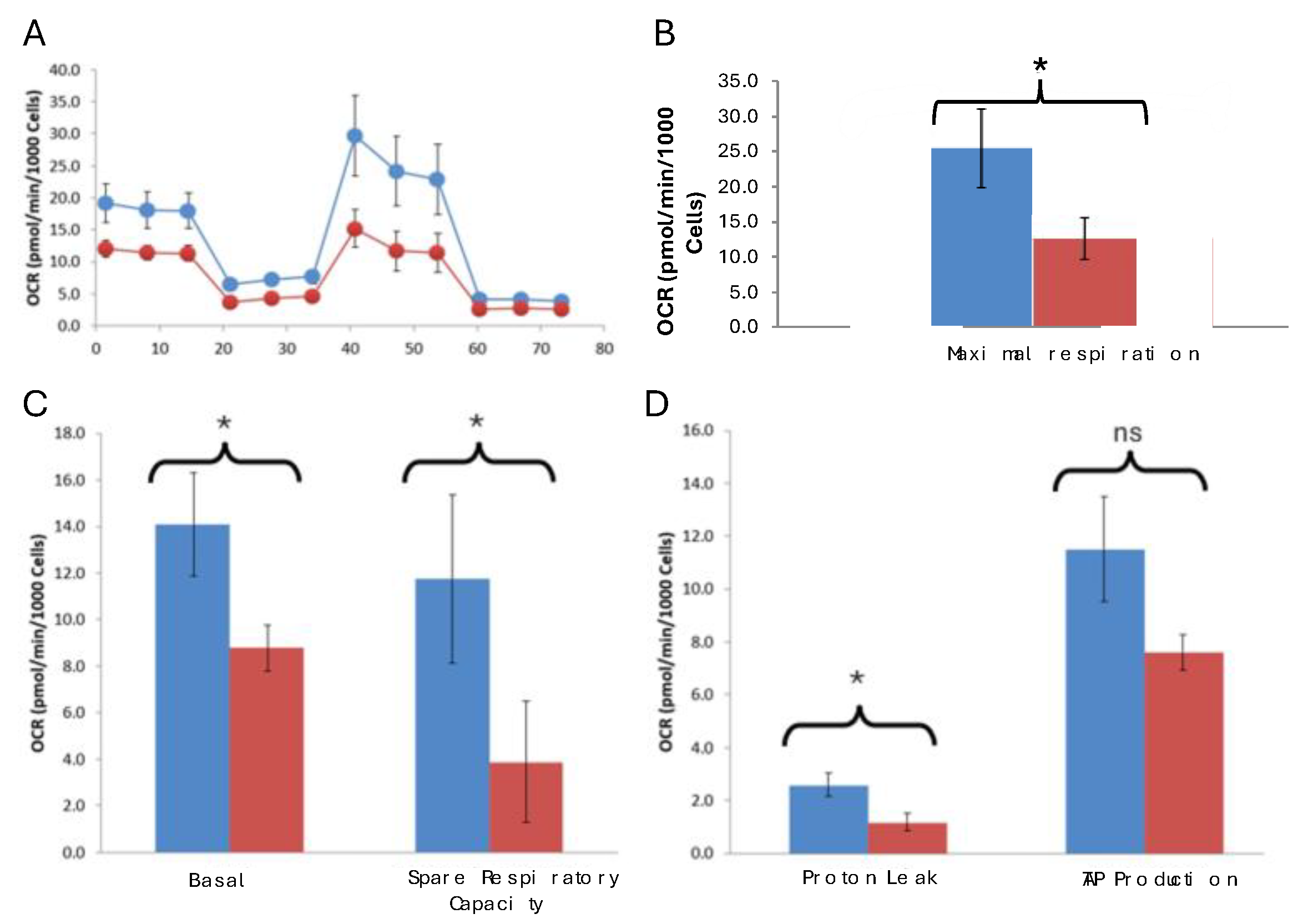

3.3. Respective Oxygen Consumption Rates of Co-Cultured N-LCL and SW1353 Cells

N-LCLs co-cultured with SW1353 cells exhibited significantly reduced basal and maximal respiration, spare respiratory capacity, and proton leak compared with controls, while ATP-linked respiration trended lower but did not reach statistical significance. Mitochondrial transport is a two-way process (

Figure 2), and we next determined metabolic profiling of monocultured SW1353 and N-LCL cells compared to co-cultured cells. Our expectations were that N-LCLs as recipient of SW1353 mitochondria will exhibit reduced metabolic activity and conversely SW1353 cells as recipients of mitochondria from N-LCLs will exhibit enhanced metabolic activity.

Normalized OCR traces showed consistent and significant differences between control N-LCLs and those co-cultured with SW1353. Control monoculture N-LCL cells exhibited higher basal respiration (14.3±2.29 vs. 9.0±0.98 pmol/min/10³ cells, p = 0.040) and maximal respiration (21.52±5.21 vs. 10.15±3.06, p = 0.039), as well as greater spare respiratory capacity (7.19±3.34 vs. 1.17±2.75, p = 0.043). Proton leak was also significantly higher in control cells (3.04±0.49 vs. 1.6±0.29, p = 0.018) (Table 3). ATP-linked respiration trended lower in experimental cocultured cells but did not reach significance (p = 0.06). Interestingly, coupling efficiency was slightly but significantly increased in experimental cells (64% vs. 61%, p = 0.048), largely due to the reduced leak component. Together, these findings demonstrate that co-cultured N-LCL cells exhibit impaired oxidative phosphorylation, characterized by reduced respiratory flexibility (

Figure 3).

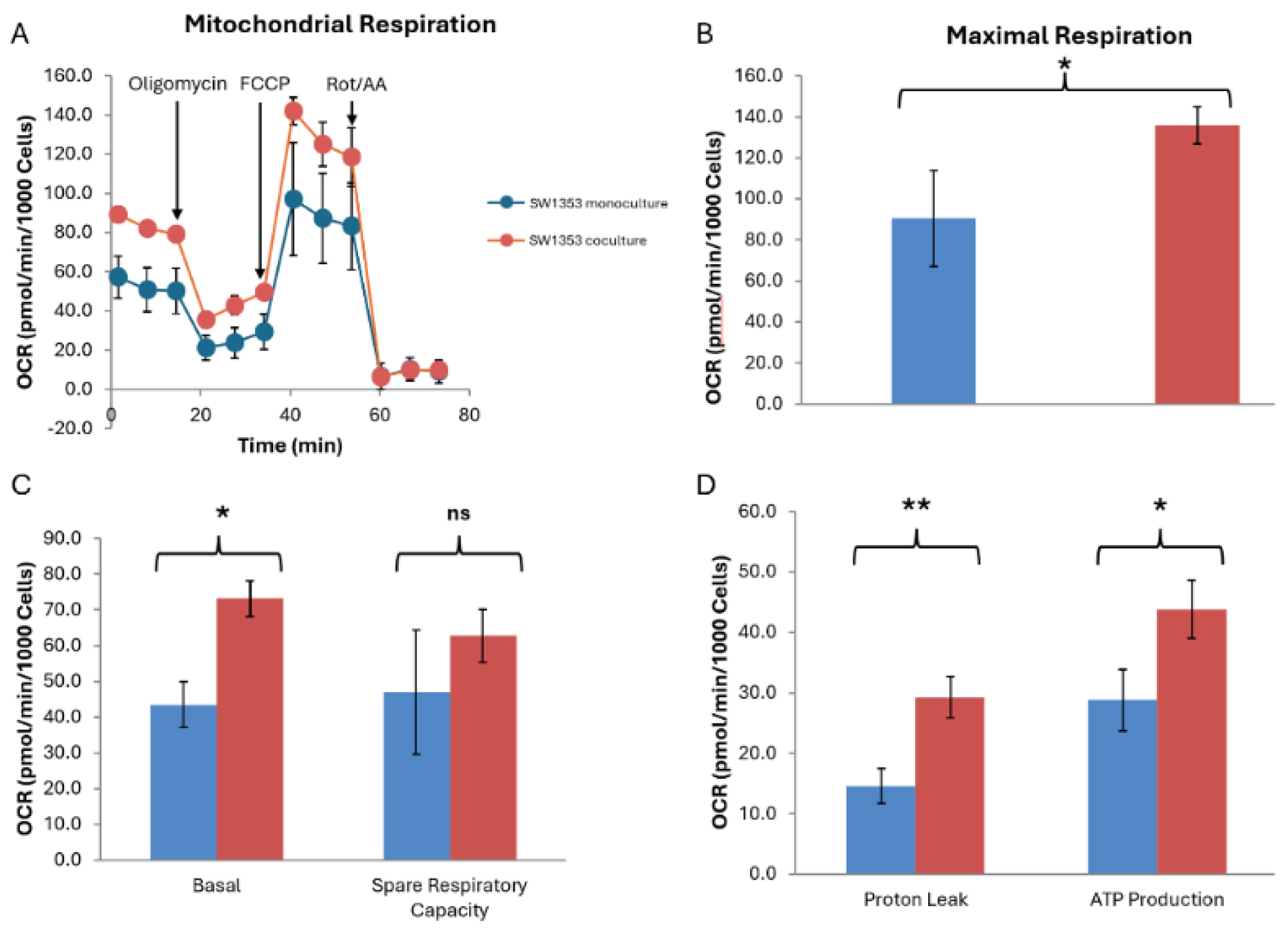

SW1353 cells co-cultured with N-LCLs exhibited significantly higher basal respiration compared with monoculture controls (83.67±2.83 vs. 52.78±11.15 pmol/min/10³ cells, p = 0.034) and markedly elevated ATP production (40.98±4.97 vs. 27.98±3.70 pmol/min/10³ cells, p = 0.025), representing an approximate 46% increase in ATP-linked respiration. Maximal OCR was likewise increased in co-cultured SW1353 cells (119.93±11.57 vs. 80.51±18.55 pmol/min/10³ cells, p = 0.045), indicating enhanced respiratory capacity under conditions of mitochondrial uncoupling. Collectively, these findings suggest that short-term co-culture with N-LCLs augments oxidative phosphorylation in SW1353 cells, consistent with a metabolic shift toward heightened mitochondrial activity (

Figure 4).

3.4. Extracellular Acidification Rate Analysis of N-LCLs

Normalized ECAR analysis further supported a hypo-energetic phenotype. Pre-oligomycin ECAR was significantly lower in experimental cells (4.4±0.51 vs. 8.1±1.29 mpH/min/10³ cells, p = 0.027), as was non-glycolytic acidification (7.70±0.85 vs. 13.3±1.85, p = 0.017). Both glycolysis (4.23±0.62 vs. 7.46±1.68, p = 0.07) and glycolytic capacity (0.91±0.46 vs. 2.28±0.83, p = 0.07) trended lower but did not reach significance at n = 3. Glycolytic reserve was minimal in both groups and unchanged (

Figure 5 and

Table S2).

Biological interpretation: Together,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 indicate that experimental N-LCLs have lower oxidative phosphorylation capacity and reduced glycolytic activity compared to controls. Rather than compensating for impaired respiration by upregulating glycolysis, the experimental cells remain globally suppressed in both pathways, resulting in a hypometabolic state. This pattern is consistent with metabolic dysfunction following mitochondrial transfer from SW1353 cells, which may be further exacerbated by exposure to the D2HG oncometabolite.

3.5. Cytochalasin B Transiently Reduces Dual-Positive Events and TNT-like Features

Live single-plane confocal images of cocultured SW1353:N-LCL cells (

Figure 6A) and from matched 6-h treated chambers showed sparse TNT-like projections and few opposite-color puncta (

Figure 6B), qualitatively aligning with the cytometry profile. In SW1353:N-LCL cocultures labeled with MitoTracker Green (SW1353) and MitoTracker Red (N-LCL), the untreated 17-h condition showed a predominant dual-positive population (Q2 = 68%) when gates set from single-stained controls were applied across panels (

Figure 6C). Cytochalasin B (10 µg/mL; 0.10% DMSO) for 6 h redistributed events away from Q2 toward single-positive quadrants (

Figure 6D), with Q2 falling to ~4% and green-only Q3 rising to ~55% in this representative run.

When incubation continued to 17 h in the presence of cytochalasin B, the dual-positive population rebounded (Q2 = 77%;

Figure 6E), indicating recovery between 6 and 17 h consistent with the short-lived/reversible nature of actin disruption under these culture conditions.

Gates and positivity thresholds were defined from unstained and single-stained mixes and held constant within the run; acquisition settings were matched across panels. Data are shown descriptively (no inferential testing for these preliminary assays). Together, the plots and images support a rapid, actin-dependent step in intercellular mitochondrial labeling that is strongly reduced at 6 h and largely restored by 17 h.

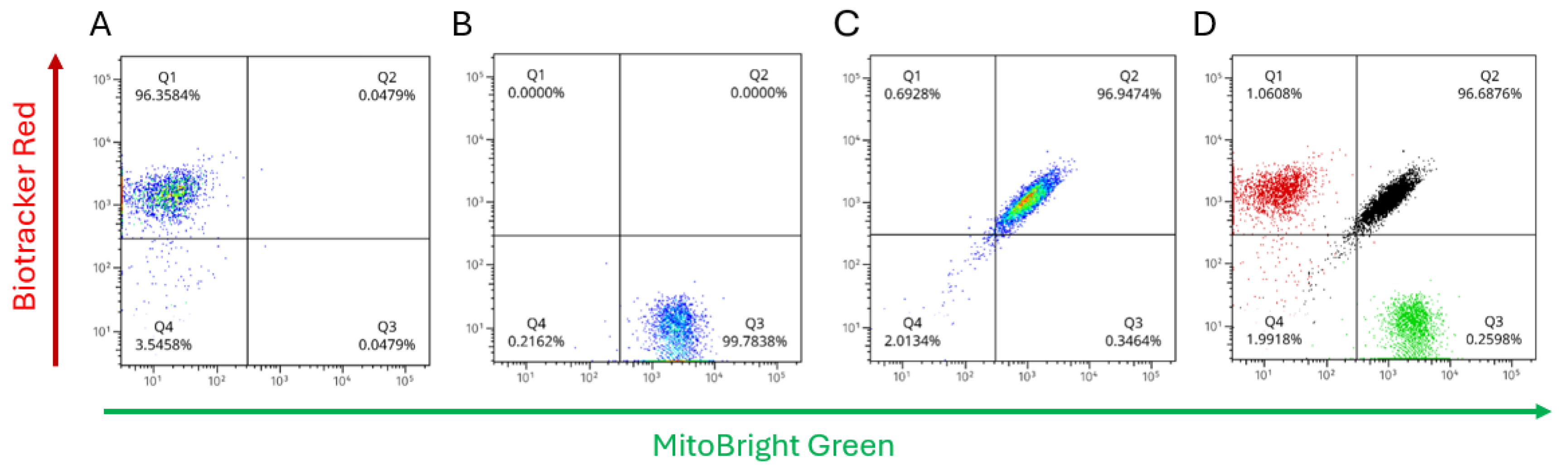

3.6. Detection of Dual Positive Mitochondrial in Labeled Cells and Direction of Transfer

Single-stain controls with mitochondrial dyes established the gating and compensation used to quantify labeling in SW1353:N-LCL cocultures (

Figure 7A–B). N-LCL mitochondria were stained with Biotracker Red (detected in PE-Cy5), and SW1353 mitochondria were stained with Mitobright Green (detected in FITC). These controls defined quadrant thresholds and verified spectral separation; the same gates were then applied unchanged to all coculture samples. After 17 h of coculture, the full-stained sample showed a predominant dual-positive cluster (

Figure 7C; Q2 = 96.9% of singlets under matched gates). Single-positive quadrants were correspondingly sparse. Because doublets were excluded by pulse-geometry gating, the large Q2 fraction reflects single cells bearing both mitochondrial labels rather than coincident events. An overlay of the single-stain controls with the coculture (

Figure 7D) illustrates gate placement and channel specificity.

Together with the confocal images, these data are consistent with extensive intercellular exchange of mitochondrial signal over 17 hours of coculture. Two points bolster this interpretation. First, the media-transfer (dye-leakage) control remained negative, arguing against free dye as a source of dual-color events. Second, immediate-mix suspension assays yielded a low dual-positive fraction under the same gates, indicating that the high Q2 signal emerges over time and with cell–cell contact, rather than from acquisition artifacts. While bulk flow does not assign directionality at the single-cell level, the near-universal Q2 population after 17 hours implies labeling in both partners; mechanistically, this aligns with the actin-dependent behavior observed in the cytochalasin-B experiments.

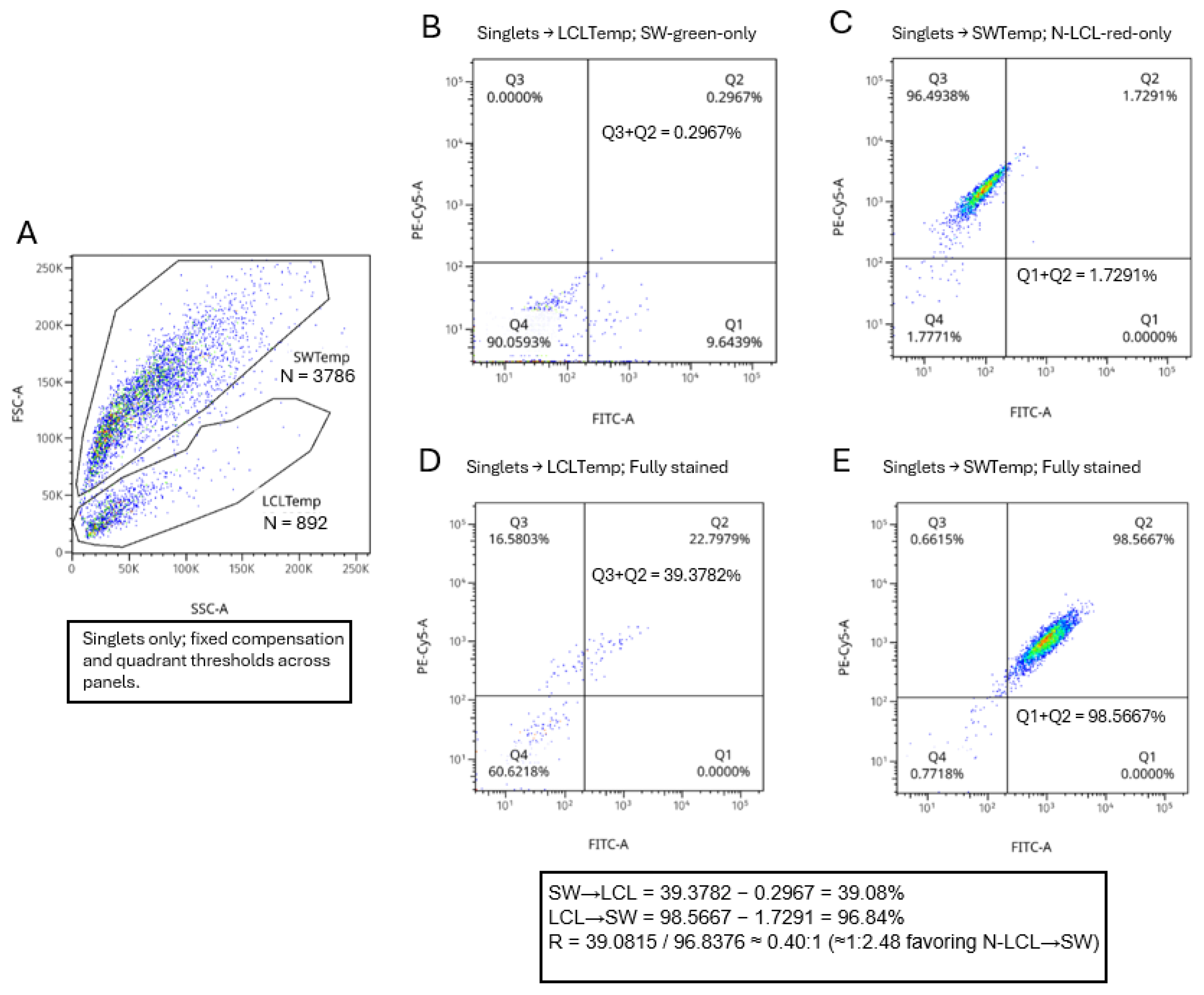

3.7. Directionality of Transfer Resolved Within Size/Granularity Templates

Restricting analysis to singlets and applying the fixed FSC/SSC templates, monostained cocultures yielded low template-classification error (misassignment) (

Figure 8A). These proportions are reported relative to the parent template gates (temp) shown in

Figure 8A and were obtained under identical compensation and quadrant thresholds across all panels. Q3+Q2 in LCLtemp on the SW-green-only tube = 0.2967% (

Figure 8B) and Q1+Q2 in SWtemp on the N-LCL-red-only tube = 1.7291% (

Figure 8C). In the fully stained coculture, the directionality inputs read from the same quadrants were Q3+Q2 in LCLtemp = 39.3782% (

Figure 8D) and Q1+Q2 in SWtemp = 98.5667% (

Figure 8E). After subtracting the corresponding misassignment values, the leak-corrected fractions were 39.0815% (SW→N-LCL) and 96.8376% (N-LCL→SW), giving a directionality ratio of R = 0.40:1 (1:2.48, favoring N-LCL→SW). These proportions are reported relative to the parent template gates and were obtained under identical compensation and quadrant thresholds across all panels. Together with singlet gating (removing doublets) and negative results in the media-transfer control, these data indicate that, over 17 h, SW1353 cells acquire mitochondrial label from N-LCLs more frequently than the reverse under the conditions tested.

While flow cytometric analyses validated the bidirectional transfer. Leak-corrected quadrant gating revealed a consistent bias toward N-LCL-to-SW1353 transfer, suggesting that tumor cells prefer acquisition of mitochondria from immune cells. This directional predominance persisted across replicates, even after normalization for unequal events counts, indicating a biological outcome rather than a technical artifact. Cytochalasin B treatment significantly reduced both TNT formation and, consequently, mitochondrial exchange, thereby establishing the process as actin dependent. Altogether, these results identify TNT-mediated exchange as a route through which chondrosarcoma cells may obtain functional organelles from surrounding immune cells.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Mitochondrial transfer has been investigated mainly in the context of rescuing damaged or stressed cells, particularly in stem cells and regenerative biology [

11,

20,

21].

Less attention has been paid to pathological scenarios where this transfer may be deleterious or hijacked by tumor cells. For example, malignant cells may use mitochondrial transfer to promote metabolic reprogramming of immune cells, impairing their anti-tumor activity, but definitive studies demonstrating such mechanisms are urgently required. Intercellular mitochondrial trafficking and its therapeutic implications [

22,

23] has been documented in several malignancies and recent findings [

19] demonstrate mitochondrial trafficking between cancer and immune cells, further underscoring the need to examine the immunomodulatory consequences of this cross talk.

Chondrosarcoma, a common form of bone cancer with very limited treatment options, provides an interesting phenomenon in this context because a mutant IDH2 enzyme converts α-ketoglutarate to the oncometabolite D2HG in the mitochondria that can then be transferred to recipient cells [

2] Understanding how transfer of IDH2 derived D2HG- containing mitochondria impacts recipient cell function, particularly in the immune compartment, remains an under-explored area [

24,

25] with therapeutic implications, representing a novel and pressing frontier in cancer metabolism and immuno-oncology.

Tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) are open-ended conduits that directly connect the cytoplasm of two cells. TNTs can transfer cargo of various sizes, encompassing not only small ions and molecules, but also larger organelles, such as lysosomes and mitochondria [

26]. Mitochondrial transport between cells is now recognized as a mechanism whereby metabolic reprogramming of donor and recipient cells can be achieved because of the transfer. TNTs are actin-filled structures [

27] that are continually forming and breaking. Previous observations in our laboratory have shown TNT connections between a monoculture of SW1353 cells with mitochondria present in TNTs. Because this cell type is IDH2 mutant, we were interested in the transfer of these mitochondria to other cell types and their receipt of normal mitochondria. To characterize the TNT structures, we hypothesized that actin disruption by cytochalasin B would prevent TNT formation between normal and SW1353 cells and mitochondrial exchange reduced. Untreated cocultures displayed a predominant dual-positive population indicative of active mitochondrial exchange, however after cytochalasin B treatment markedly reduced dual-positive events were observed consistent with inhibition of actin-based tunneling nanotubes. After 17 h of treatment, the dual-positive population partially recovered, suggesting restoration of intercellular connectivity indicative of reduced cytochalasin potency. As expected, this observation is similar to others [

28,

29,

30] where cytochalasin B abolished the formation of TNTs, inhibiting intercellular transport.

Without time-lapse imagery, microscope analysis is limited, and we could not quantify mitochondrial movement or direction. By using a combination of confocal microscopy, flow cytometry, and Seahorse metabolic analysis we show for the first time that mitochondrial exchange occurs bidirectionally between chondrosarcoma and B-lymphoblastoid cells, an observation in broad agreement with other studies using different cancer models [

20,

28,

31,

32]. Additionally, we provide new evidence that intercellular mitochondrial exchange comes with measurable metabolic consequences to both cell types. Interestingly, our data shows an unequal transfer of mitochondria, with more mitochondria transferred from N-LCL cells to the chondrosarcoma cell line SW1353 with a 46% increase in ATP production. Although higher than other studies [

28,

33] that observed an ~1.5-fold increase in ATP production by cancer cells, in common between studies is that referenced cancer cells are empowered while immune cells become metabolically depleted. Interestingly, using RNA seq, a near-unidirectional mitochondrial transfer from primary murine T cells to a murine lung cancer cell line was observed [

32], Given that our study uses cell lines different to other studies does not negate the possibility that different cancer types may initiate a mitochondrial ‘grab’ to promote their metabolism that may be dependent on the original metabolic requirements of the cancers’ originating cells. Cartilage forming tumors with IDH2 mutations more closely reflect the lower metabolic activity of primary chondrocytes and do not require a large influx of mitochondria to achieve the higher relative increase in metabolic activity. This poses a dilemma in that the IDH1 mutant chondrosarcoma cell line JJ012 has a high metabolic rate and thus a higher mitochondrial uptake from immune cells may be required. IDH1 and IDH2 mutant chondrosarcoma could be susceptible to different therapeutic approaches if this hypothesis could be confirmed in primary resected tumors. Likewise, differential depletion of mitochondria from immune cells will leave these cells metabolically exhausted and loss of immune response would be different in the IDH1 mutant tumor microenvironment compared to that of IDH2 mutant. The reduced metabolic rates in IDH2 mutants could be a result of the presence of D2HG within the mitochondria. Although direct evidence is lacking that mitochondrial RNA expression may be compromised in IDH2 mutant mitochondria, it is known that D2HG inhibits RNA demethylases in IDH1 mutant glioma [

34], suppressing their function, and could therefore be confirmed by RNA sequencing in IDH2 mutant cells.

We examined how mitochondrial transfer affected metabolic function in both cell types. Seahorse extracellular flux analysis using the MitoStress Test revealed that N-LCLs cocultured with SW1353 exhibited a marked reduction in both OCR and ECAR, implying a hypometabolic phenotype. Despite lower metabolic activity, however, ATP production remained stable, suggesting that transferred mitochondria or altered redox conditions may transiently sustain cellular energy homeostasis. These data suggest that donating mitochondria imposes a bioenergetic cost on immune cells, consistent with the observed directionality of transfer. Although metabolic enhancement of SW1353 following mitochondrial acquisition was not directly measured, the preferred uptake of mitochondria by tumor cells suggests a conferred adaptive advantage under oxidative or nutrient stress.

The higher basal ECAR and sustained acidification in JJ012 indicate greater glycolytic flux and proton export at baseline (i.e., more lactate production), consistent with a glycolysis-biased/Warburg-like phenotype under these conditions. This profile could reflect mitochondrial coupling limits or lower spare reserve, and/or oncogenic programs (e.g., HIF-1α/PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling, altered redox from IDH-pathway contexts) that upregulate glycolytic enzymes and acid extrusion. Media were bicarbonate-free and pH-controlled, so ECAR here primarily tracks glycolysis rather than CO₂ hydration.

5. Conclusions

This study supports the emerging concept that metabolic reprogramming is not confined to single cells but can be transmitted intercellularly through organelle exchange. Evidence is accumulating that supports a role for mitochondrial transfer from normal cells to cancer cells as a mechanism that protects cancer cells when exposed to chemo and radiotherapy e.g., [

4,

7,

31,

35,

36,

37]. In this study we show, for the first time in an IDH2 mutant chondrosarcoma, that two-way mitochondrial transfer occurs between normal and cancer cells and that the transfer is unequal. More mitochondria are transferred from normal to cancer cells and importantly, this is reflected as metabolic changes in the two cell types. There is an increase in metabolic activity in cancer cells, and a reduction in normal cells. Chondrosarcoma, particularly on recurrence, appear immune to the effects of chemo-and radiation therapy. Mitochondrial transfer clearly is important in protecting cancer cells and may offer a new therapeutic avenue in the treatment of this disease. Despite this study’s strengths, several limitations should be acknowledged. The experimental design was performed entirely in vitro using a single IDH2 immortalized cell line, which simply do not replicate the complexity of in vivo-tumor-immune interactions. D2HG is likely co-transferred with mitochondria, and/or released in the recipient LCL cells from the transferred mitos. The role of D2HG transfer from cancer to normal cells was not investigated but is clearly an important factor in the recipient cells physiology.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Normalized mitochondrial respiration parameters across fibroblasts, JJ012, SW1353, and primary chondrocytes. Table S2: Glycolytic parameters derived from ECAR measurements across fibroblasts, JJ012, SW1353, and primary chondrocytes. Table S3: Pairwise comparison of basal mitochondrial and glycolytic activity between JJ012 and SW1353 cells.

Author Contributions

CW; conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing. CO; writing, reviewing, and editing, conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation. EJ; methodology, formal analysis, investigation. MS; supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, conceptualization, and writing original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research described was supported by the 2024 John O’Brien Memorial Research Award grant number SFA 1292783 from the Sarcoma Foundation of America.

Data Availability Statement

The data used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank all laboratory partners, faculty members, and technicians who provided technical support, informational advice, or friendly assistance with this study. Particularly, thanks go to Dr. Piotr Kraj, Dept of Biology, ODU for invaluable thoughts and discussions and Dr. Elena Galkina, Dr. Alina Moriaty, and Alex Coleman of Eastern Virginia Medical School for help with Flow cytometry.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Venneker, S.; Kruisselbrink, A.B.; Baranski, Z.; Palubeckaite, I.; Bruijn, I.H.B.-D.; Oosting, J.; French, P.J.; Danen, E.H.J.; Bovée, J.V.M.G. Beyond the Influence of IDH Mutations: Exploring Epigenetic Vulnerabilities in Chondrosarcoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.; Hu, H. The Roles of 2-Hydroxyglutarate. Front Cell. Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 651317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zeinalzadeh, Z.; Huang, T.; Han, Y.; Peng, L.; Wang, D.; Zhou, Z.; Ousmane, D.; Wang, J. Mitochondria-related chemoradiotherapy resistance genes-based machine learning model associated with immune cell infiltration on the prognosis of esophageal cancer and its value in pan-cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 42, 101896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, D.; Li, Y. Mitochondria: A crucial factor in the progression and drug resistance of colorectal cancer. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1512469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Mukherjee, S.; Pattnaik, B.; Kumar, M.; Singh, S.; Rehman, R.; Tiwari, B.K.; A Jha, K.; Barhanpurkar, A.P.; Wani, M.R.; et al. Miro1 regulates intercellular mitochondrial transport & enhances mesenchymal stem cell rescue efficacy. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 994–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, E.; Fujisawa, S.; Barlas, A.; Romin, Y.; Manova-Todorova, K.; Moore, M.A.; Subramanian, S. Tunneling Nanotubes: A new paradigm for studying intercellular communication and therapeutics in cancer. Commun Integr Biol 2012, 5, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, M.V.; McConnell, M.J.; Grasso, C.; Bajzikova, M.; Kovarova, J.; Neuzil, J. Horizontal transfer of mitochondria between mammalian cells: Beyond co-culture approaches. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2016, 38, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustom, A.; Saffrich, R.; Markovic, I.; Walther, P.; Gerdes, H.-H. Nanotubular Highways for Intercellular Organelle Transport. Science 2004, 303, 1007–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, J.G.; Heuser-Loy, C.; Saha, T.; Schelker, R.C.; Slavkovic-Lukic, D.; Strieder, N. Intercellular nanotube-mediated mitochondrial transfer enhances T cell metabolic fitness and antitumor efficacy. Cell 2024, 187, 6614–6630 e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquier, J.; Guerrouahen, B.S.; Al Thawadi, H.; Ghiabi, P.; Maleki, M.; Abu-Kaoud, N.; Jacob, A.; Mirshahi, M.; Galas, L.; Rafii, S.; et al. Preferential transfer of mitochondria from endothelial to cancer cells through tunneling nanotubes modulates chemoresistance. J. Transl. Med. 2013, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, D.G.; Di Giuseppe, M.; Njah, J.; Sala, E.; Shiva, S.; St Croix, C.M.; Stolz, D.B.; Watkins, S.C.; Di, Y.P.; Leikauf, G.D.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells use extracellular vesicles to outsource mitophagy and shuttle microRNAs. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.S.; Baty, J.W.; Dong, L.-F.; Bezawork-Geleta, A.; Endaya, B.; Goodwin, J.; Bajzikova, M.; Kovarova, J.; Peterka, M.; Yan, B.; et al. Mitochondrial Genome Acquisition Restores Respiratory Function and Tumorigenic Potential of Cancer Cells without Mitochondrial DNA. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turcan, S.; Rohle, D.; Goenka, A.; Walsh, L.A.; Fang, F.; Yilmaz, E.; Campos, C.; Fabius, A.W.M.; Lu, C.; Ward, P.S.; et al. IDH1 mutation is sufficient to establish the glioma hypermethylator phenotype. Nature 2012, 483, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, P.S.; Patel, J.; Wise, D.R.; Abdel-Wahab, O.; Bennett, B.D.; Coller, H.A.; Cross, J.R.; Fantin, V.R.; Hedvat, C.V.; Perl, A.E.; et al. The Common Feature of Leukemia-Associated IDH1 and IDH2 Mutations Is a Neomorphic Enzyme Activity Converting α-Ketoglutarate to 2-Hydroxyglutarate. Cancer Cell 2010, 17, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, M.E.; Abdel-Wahab, O.; Lu, C.; Ward, P.S.; Patel, J.; Shih, A.; Li, Y.; Bhagwat, N.; VasanthaKumar, A.; Fernandez, H.F.; et al. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 Mutations Result in a Hypermethylation Phenotype, Disrupt TET2 Function, and Impair Hematopoietic Differentiation. Cancer Cell 2010, 18, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitman, Z.J.; Yan, H. Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 and 2 Mutations in Cancer: Alterations at a Crossroads of Cellular Metabolism. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010, 102, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juraszek, B.; Nałęcz, K.A. SLC22A5 (OCTN2) Carnitine Transporter—Indispensable for Cell Metabolism, a Jekyll and Hyde of Human Cancer. Molecules 2019, 25, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kang, Z.; Xu, R.; Hou, S.; Gong, L.; Guo, L.; Gao, K.; Xu, X.; Tan, X.; Xiao, D.; et al. A genetically encoded biosensor for point-of-care and live-cell detection of d-2-hydroxyglutarate. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, T.; Dash, C.; Jayabalan, R.; Khiste, S.; Kulkarni, A.; Kurmi, K.; Mondal, J.; Majumder, P.K.; Bardia, A.; Jang, H.L.; et al. Intercellular nanotubes mediate mitochondrial trafficking between cancer and immune cells. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 17, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.N.; Das, S.R.; Emin, M.T.; Wei, M.; Sun, L.; Westphalen, K.; Rowlands, D.J.; Quadri, S.K.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhattacharya, J. Mitochondrial transfer from bone-marrow–derived stromal cells to pulmonary alveoli protects against acute lung injury. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukar, J.; Singh, K.A.; Aviles, A.; Hargett, S.; Kaur, H.; Foster, S.; Roy, S.; Zhao, F.; Gohil, V.M.; Singh, I.; et al. Nanomaterial-induced mitochondrial biogenesis enhances intercellular mitochondrial transfer efficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2025, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Zhao, D. Invisible Bridges: Unveiling the Role and Prospects of Tunneling Nanotubes in Cancer Therapy. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 5413–5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, F.; Wu, X.; Zhou, J.; Lin, Y.; He, Y.; Fan, C.; Zeng, Z.; Xiong, W. Mitochondrial transfer in tunneling nanotubes—a new target for cancer therapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Can, C.; Liu, W.; Wei, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Jia, H.; Jia, W.; Wu, H.; Ma, D. Mitochondrial transfer in hematological malignancies. Biomark. Res. 2023, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micaily, I.; Roche, M.; Ibrahim, M.Y.; Martinez-Outschoorn, U.; Mallick, A.B. Metabolic Pathways and Targets in Chondrosarcoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Y.M.; Inaba, M.; Buszczak, M. Specialized Intercellular Communications via Cytonemes and Nanotubes. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 34, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubojevic, N.; Henderson, J.M.; Zurzolo, C. The Ways of Actin: Why Tunneling Nanotubes Are Unique Cell Protrusions. Trends Cell Biol. 2021, 31, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlein, C.R.; Zaitseva, L.; Piddock, R.E.; Robinson, S.D.; Edwards, D.R.; Shafat, M.S.; Zhou, Z.; Lawes, M.; Bowles, K.M.; Rushworth, S.A. NADPH oxidase-2 derived superoxide drives mitochondrial transfer from bone marrow stromal cells to leukemic blasts. Blood 2017, 130, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gerdes, H.-H. Transfer of mitochondria via tunneling nanotubes rescues apoptotic PC12 cells. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 1181–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamberlan, M.; Semenzato, M. Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Transfer Through TNTs: From Organelle Dynamics to Cellular Crosstalk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkari, A.; Lou, E. Do tunneling nanotubes drive chemoresistance in solid tumors and other malignancies? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2024, 52, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, X.; Ye, J.; Li, H.; Hu, J.; Tan, Y.; Fang, Y.; Akbay, E.; Yu, F.; Weng, C.; et al. Systematic investigation of mitochondrial transfer between cancer cells and T cells at single-cell resolution. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 1788–1802.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goliwas, K.F.; Libring, S.; Berestesky, E.; Gholizadeh, S.; Schwager, S.C.; Frost, A.R.; Gaborski, T.R.; Zhang, J.; Reinhart-King, C.A. Mitochondrial transfer from cancer-associated fibroblasts increases migration in aggressive breast cancer. J. Cell Sci. 2023, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianka, S.T.; Li, T.; Prins, T.J.; Eldred, B.S.; Kevan, B.M.; Liang, H.; Rinonos, S.Z.; Kornblum, H.I.; Nathanson, D.A.; Pellegrini, M.; et al. D-2-HG Inhibits IDH1mut Glioma Growth via FTO Inhibition and Resultant m6A Hypermethylation. Cancer Res. Commun. 2024, 4, 876–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschoi, R.; Imbert, V.; Nebout, M.; Chiche, J.; Mary, D.; Prebet, T.; Saland, E.; Castellano, R.; Pouyet, L.; Collette, Y.; et al. Protective mitochondrial transfer from bone marrow stromal cells to acute myeloid leukemic cells during chemotherapy. Blood 2016, 128, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.-F.; Rohlena, J.; Zobalova, R.; Nahacka, Z.; Rodriguez, A.-M.; Berridge, M.V.; Neuzil, J. Mitochondria on the move: Horizontal mitochondrial transfer in disease and health. J. Cell Biol. 2023, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Merwe, M.; van Niekerk, G.; Fourie, C.; du Plessis, M.; Engelbrecht, A.M. The impact of mitochondria on cancer treatment resistance. Cell Oncol 2021, 44, 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Agilent Seahorse XFp Mito Stress Test profiles for SW1353 (IDH2 mutant), JJ012 (IDH1 mutant), primary fibroblasts, and primary chondrocytes. (

A) A schematic of the Agilent Mito Stress Test profile is included as a schematic of inhibitor sequence (oligomycin to FCCP to rotenone/antimycin A). (

B) OCR time course shows canonical responses with similar basal and FCCP-stimulated respiration between SW1353, JJ012, and fibroblasts compared to low levels in chondrocytes. (

C) Basal OCR was comparable among fibroblasts, JJ012, and SW1353 cells, whereas primary chondrocytes exhibited markedly reduced OCR, consistent with lower mitochondrial respiratory capacity. (

D) ECAR time-course analysis revealed a graded glycolytic response, with JJ012 cells exhibiting the highest extracellular acidification rates, fibroblasts and SW1353 showing intermediate levels, and primary chondrocytes displaying the lowest ECAR. Details can be found in supplemental

Tables S1-S3.

Figure 1.

Agilent Seahorse XFp Mito Stress Test profiles for SW1353 (IDH2 mutant), JJ012 (IDH1 mutant), primary fibroblasts, and primary chondrocytes. (

A) A schematic of the Agilent Mito Stress Test profile is included as a schematic of inhibitor sequence (oligomycin to FCCP to rotenone/antimycin A). (

B) OCR time course shows canonical responses with similar basal and FCCP-stimulated respiration between SW1353, JJ012, and fibroblasts compared to low levels in chondrocytes. (

C) Basal OCR was comparable among fibroblasts, JJ012, and SW1353 cells, whereas primary chondrocytes exhibited markedly reduced OCR, consistent with lower mitochondrial respiratory capacity. (

D) ECAR time-course analysis revealed a graded glycolytic response, with JJ012 cells exhibiting the highest extracellular acidification rates, fibroblasts and SW1353 showing intermediate levels, and primary chondrocytes displaying the lowest ECAR. Details can be found in supplemental

Tables S1-S3.

Figure 2.

Confocal imaging shows TNT-like connections and opposite-color mitochondrial signal in SW1353:N-LCL cocultures. (A). Brightfield + fluorescence overlay (green = SW1353 mitochondria; red = N-LCL mitochondria; blue = Hoechst stained nucleus). Black arrows indicate N-LCLs at sites of TNT contact. Scale bars, 50 µm.

Figure 2.

Confocal imaging shows TNT-like connections and opposite-color mitochondrial signal in SW1353:N-LCL cocultures. (A). Brightfield + fluorescence overlay (green = SW1353 mitochondria; red = N-LCL mitochondria; blue = Hoechst stained nucleus). Black arrows indicate N-LCLs at sites of TNT contact. Scale bars, 50 µm.

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial transfer from SW1353 impairs oxidative phosphorylation in N-LCLs. (A) Normalized oxygen consumption rate (OCR) traces of control N-LCLs (blue) and N-LCLs co-cultured with SW1353 chondrosarcoma cells (red) over the course of a mitochondrial stress test. (B) Maximal respiration is significantly decreased in cocultured N-LCLs. (C) Bar graphs showing significant reduction in basal respiration and spare respiratory capacity in cocultured N-LCLs. (D) Bar graphs of proton leak and ATP-linked respiration. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by Welch’s unpaired t-test; p < 0.05 (*), not significant (ns).

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial transfer from SW1353 impairs oxidative phosphorylation in N-LCLs. (A) Normalized oxygen consumption rate (OCR) traces of control N-LCLs (blue) and N-LCLs co-cultured with SW1353 chondrosarcoma cells (red) over the course of a mitochondrial stress test. (B) Maximal respiration is significantly decreased in cocultured N-LCLs. (C) Bar graphs showing significant reduction in basal respiration and spare respiratory capacity in cocultured N-LCLs. (D) Bar graphs of proton leak and ATP-linked respiration. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by Welch’s unpaired t-test; p < 0.05 (*), not significant (ns).

Figure 4.

Coculture with N-LCLs enhances oxidative metabolism in SW1353 chondrosarcoma cells. (A) Representative OCR time course from the Seahorse XF Mito Stress Test showing SW1353 cells cultured alone (monoculture, blue) or cocultured with N-LCLs (red). Sequential injections of oligomycin, FCCP, and rotenone/antimycin A are indicated. (B) Quantification of maximal respiration revealed a significant increase in cocultured SW1353 cells compared with monoculture controls. (C) Basal OCR was significantly elevated in cocultured SW1353 cells, whereas spare respiratory capacity did not differ significantly between conditions. (D) Coculture significantly increased both proton leak and ATP-linked respiration in SW1353 cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD of normalized OCR values (pmol/min/10³ cells). Statistical significance was determined using Welch’s unpaired t-test; *p < 0.05, *p < 0.01; ns, not significant.

Figure 4.

Coculture with N-LCLs enhances oxidative metabolism in SW1353 chondrosarcoma cells. (A) Representative OCR time course from the Seahorse XF Mito Stress Test showing SW1353 cells cultured alone (monoculture, blue) or cocultured with N-LCLs (red). Sequential injections of oligomycin, FCCP, and rotenone/antimycin A are indicated. (B) Quantification of maximal respiration revealed a significant increase in cocultured SW1353 cells compared with monoculture controls. (C) Basal OCR was significantly elevated in cocultured SW1353 cells, whereas spare respiratory capacity did not differ significantly between conditions. (D) Coculture significantly increased both proton leak and ATP-linked respiration in SW1353 cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD of normalized OCR values (pmol/min/10³ cells). Statistical significance was determined using Welch’s unpaired t-test; *p < 0.05, *p < 0.01; ns, not significant.

Figure 5.

Normalized ECAR in control and experimental N-LCLs. ECAR was measured in control N-LCLs (blue) and N-LCLs cocultured with SW1353 chondrosarcoma cells (red) during a Seahorse XF Mito Stress Test. Data were normalized to cell counts (Hoechst staining, per 1000 cells). Control cells exhibited higher baseline ECAR values compared with experimental cells (p = 0.027), as well as significantly greater non-glycolytic acidification following rotenone/antimycin A (p = 0.017). Both glycolysis and glycolytic capacity trended lower in experimental cells but did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.07, N = 3). Together, these results indicate that experimental N-LCLs display reduced glycolytic activity in parallel with impaired oxidative phosphorylation. Data shown are mean ± SD of three wells per group.

Figure 5.

Normalized ECAR in control and experimental N-LCLs. ECAR was measured in control N-LCLs (blue) and N-LCLs cocultured with SW1353 chondrosarcoma cells (red) during a Seahorse XF Mito Stress Test. Data were normalized to cell counts (Hoechst staining, per 1000 cells). Control cells exhibited higher baseline ECAR values compared with experimental cells (p = 0.027), as well as significantly greater non-glycolytic acidification following rotenone/antimycin A (p = 0.017). Both glycolysis and glycolytic capacity trended lower in experimental cells but did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.07, N = 3). Together, these results indicate that experimental N-LCLs display reduced glycolytic activity in parallel with impaired oxidative phosphorylation. Data shown are mean ± SD of three wells per group.

Figure 6.

Brightfield and fluorescence micrographs show intact TNT-like projections connecting SW1353 and N-LCL cells in untreated cocultures (A, black arrows) and loss of these structures after 6 h of Cytochalasin B exposure (B). Scale bars = 50 µm. Cytochalasin B briefly suppresses dual-positive events in SW1353:N-LCL cocultures. (C–E) Flow-cytometry analysis of cocultures stained with MitoTracker Green FM (x-axis, SW1353 mitochondria) and MitoTracker Red FM (y-axis, N-LCL mitochondria). Untreated cocultures (C) display a predominant dual-positive population (Q2 = 68.3%) indicative of active mitochondrial exchange. Cytochalasin B treatment for 6 h (D) markedly reduced dual-positive events (Q2 = 4.1%), consistent with inhibition of actin-based tunneling nanotubes. After 17 h of treatment (E), the dual-positive population partially recovered (Q2 = 76.5%), suggesting restoration of intercellular connectivity. (A and B).

Figure 6.

Brightfield and fluorescence micrographs show intact TNT-like projections connecting SW1353 and N-LCL cells in untreated cocultures (A, black arrows) and loss of these structures after 6 h of Cytochalasin B exposure (B). Scale bars = 50 µm. Cytochalasin B briefly suppresses dual-positive events in SW1353:N-LCL cocultures. (C–E) Flow-cytometry analysis of cocultures stained with MitoTracker Green FM (x-axis, SW1353 mitochondria) and MitoTracker Red FM (y-axis, N-LCL mitochondria). Untreated cocultures (C) display a predominant dual-positive population (Q2 = 68.3%) indicative of active mitochondrial exchange. Cytochalasin B treatment for 6 h (D) markedly reduced dual-positive events (Q2 = 4.1%), consistent with inhibition of actin-based tunneling nanotubes. After 17 h of treatment (E), the dual-positive population partially recovered (Q2 = 76.5%), suggesting restoration of intercellular connectivity. (A and B).

Figure 7.

Overnight coculture produces a dominant dual-positive population of cells bearing both mitochondrial labels. (A) N-LCL mitochondria stained red (BioTracker Red; y-axis) with minimal MitoBright Green. (B) SW1353 mitochondria stained green (MitoBright Green; x-axis) with minimal BioTracker Red. (C) 17-h coculture plotted with the same compensation, axes, and fixed quadrant gates shows a predominant dual-positive cluster (Q2 = 96.9% of singlets), indicating cells that contain both red- and green-labeled mitochondria. (D) Overlay of single-stain controls with the coculture confirms gate placement and channel specificity. Singlet gating (FSC/SSC pulse geometry) and sequential channel acquisition were used; no-cell background was included for drift correction (not shown).

Figure 7.

Overnight coculture produces a dominant dual-positive population of cells bearing both mitochondrial labels. (A) N-LCL mitochondria stained red (BioTracker Red; y-axis) with minimal MitoBright Green. (B) SW1353 mitochondria stained green (MitoBright Green; x-axis) with minimal BioTracker Red. (C) 17-h coculture plotted with the same compensation, axes, and fixed quadrant gates shows a predominant dual-positive cluster (Q2 = 96.9% of singlets), indicating cells that contain both red- and green-labeled mitochondria. (D) Overlay of single-stain controls with the coculture confirms gate placement and channel specificity. Singlet gating (FSC/SSC pulse geometry) and sequential channel acquisition were used; no-cell background was included for drift correction (not shown).

Figure 8.

Directionality of mitochondrial transfer resolved with FSC/SSC templates (temp) and fixed quadrants. (A) On FSC-A vs SSC-A of the unstained coculture (singlets), size/granularity template gates LCLtemp and SWtemp were defined and applied unchanged to all tubes (Number of recorded events, N shown per template 8A). LCLtemp is the gated N-LCL cell population and SWtemp is the gated SW1353 population. (B–C) Using monostained cocultures with the same quadrant thresholds (PE-Cy5-A vs FITC-A), template misassignment was quantified within each template: SW→LCL misassignment as Q3+Q2 within LCLtemp on the SW-green-only tube (B), and LCL→SW misassignment as Q1+Q2 within SWtemp on the N-LCL-red-only tube (C). (D–E) In the fully stained coculture, directionality inputs were read within each template using the same quadrants: SW→N-LCL as Q3+Q2 within LCLtemp (D) and N-LCL→SW as Q1+Q2 within SWtemp (E). Leak-corrected fractions (shown in the inset) yielded R = 0.40:1 (≈1:2.48 favoring N-LCL→SW). All percentages are relative to the parent template gate and within singlets.

Figure 8.

Directionality of mitochondrial transfer resolved with FSC/SSC templates (temp) and fixed quadrants. (A) On FSC-A vs SSC-A of the unstained coculture (singlets), size/granularity template gates LCLtemp and SWtemp were defined and applied unchanged to all tubes (Number of recorded events, N shown per template 8A). LCLtemp is the gated N-LCL cell population and SWtemp is the gated SW1353 population. (B–C) Using monostained cocultures with the same quadrant thresholds (PE-Cy5-A vs FITC-A), template misassignment was quantified within each template: SW→LCL misassignment as Q3+Q2 within LCLtemp on the SW-green-only tube (B), and LCL→SW misassignment as Q1+Q2 within SWtemp on the N-LCL-red-only tube (C). (D–E) In the fully stained coculture, directionality inputs were read within each template using the same quadrants: SW→N-LCL as Q3+Q2 within LCLtemp (D) and N-LCL→SW as Q1+Q2 within SWtemp (E). Leak-corrected fractions (shown in the inset) yielded R = 0.40:1 (≈1:2.48 favoring N-LCL→SW). All percentages are relative to the parent template gate and within singlets.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |