Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

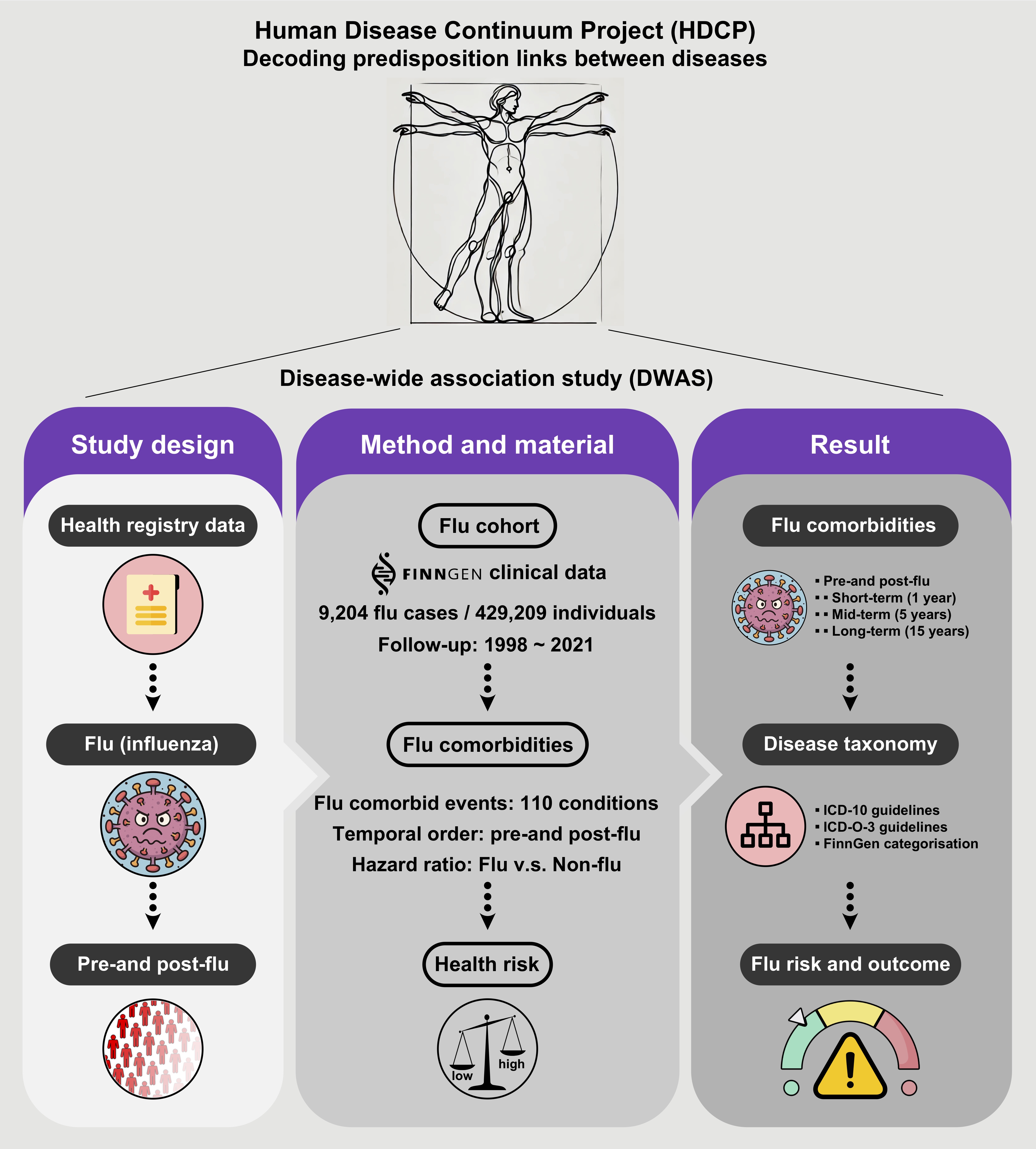

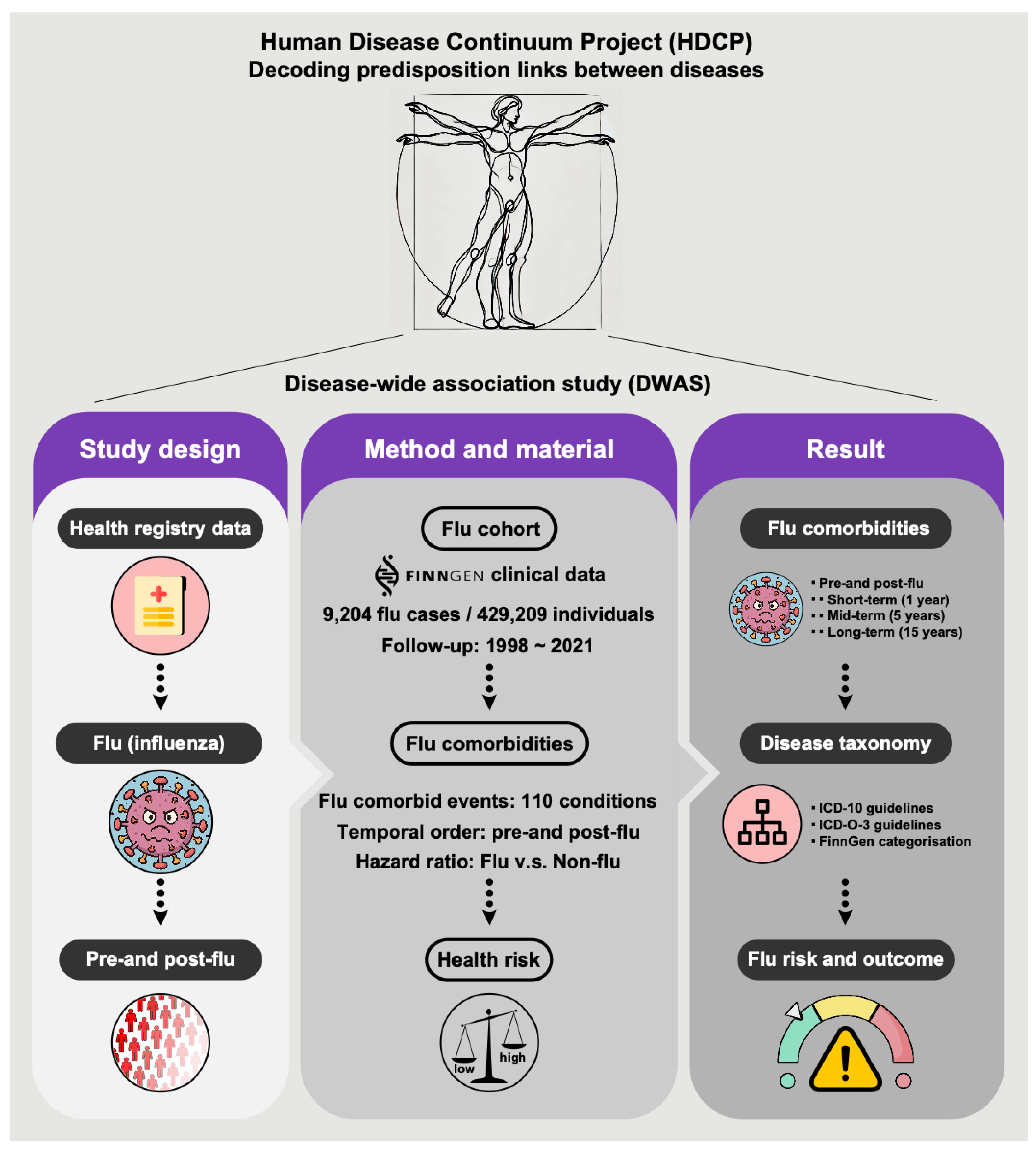

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

2.2. Cohort Assembly and Definition

2.3. Disease Endpoint Ascertainment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

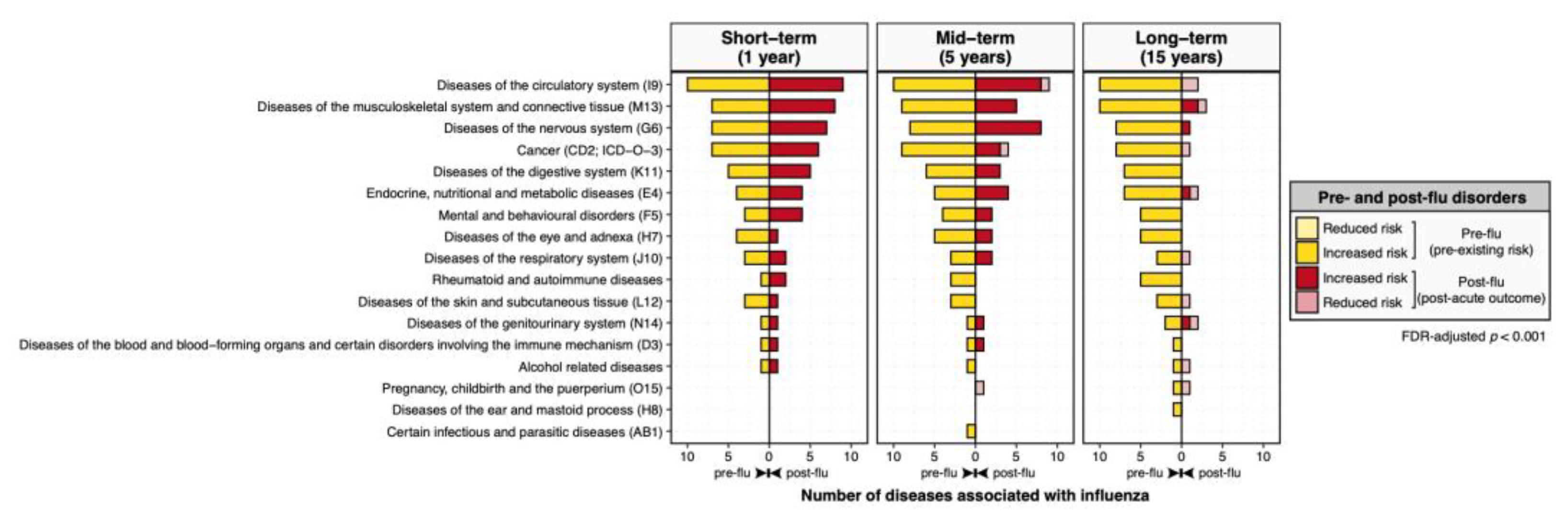

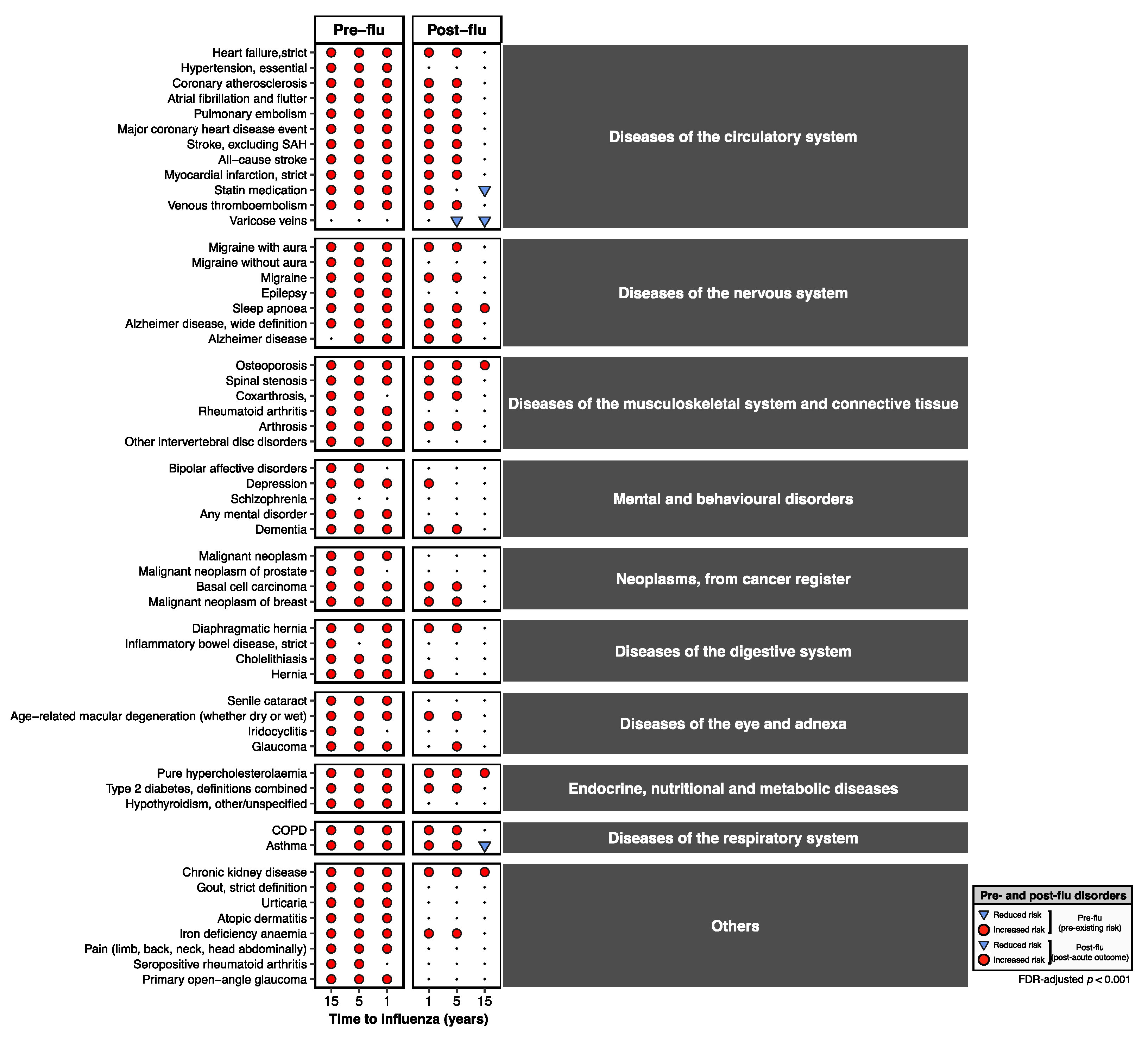

3.1. Overview of Disease-Wide Association of Influenza

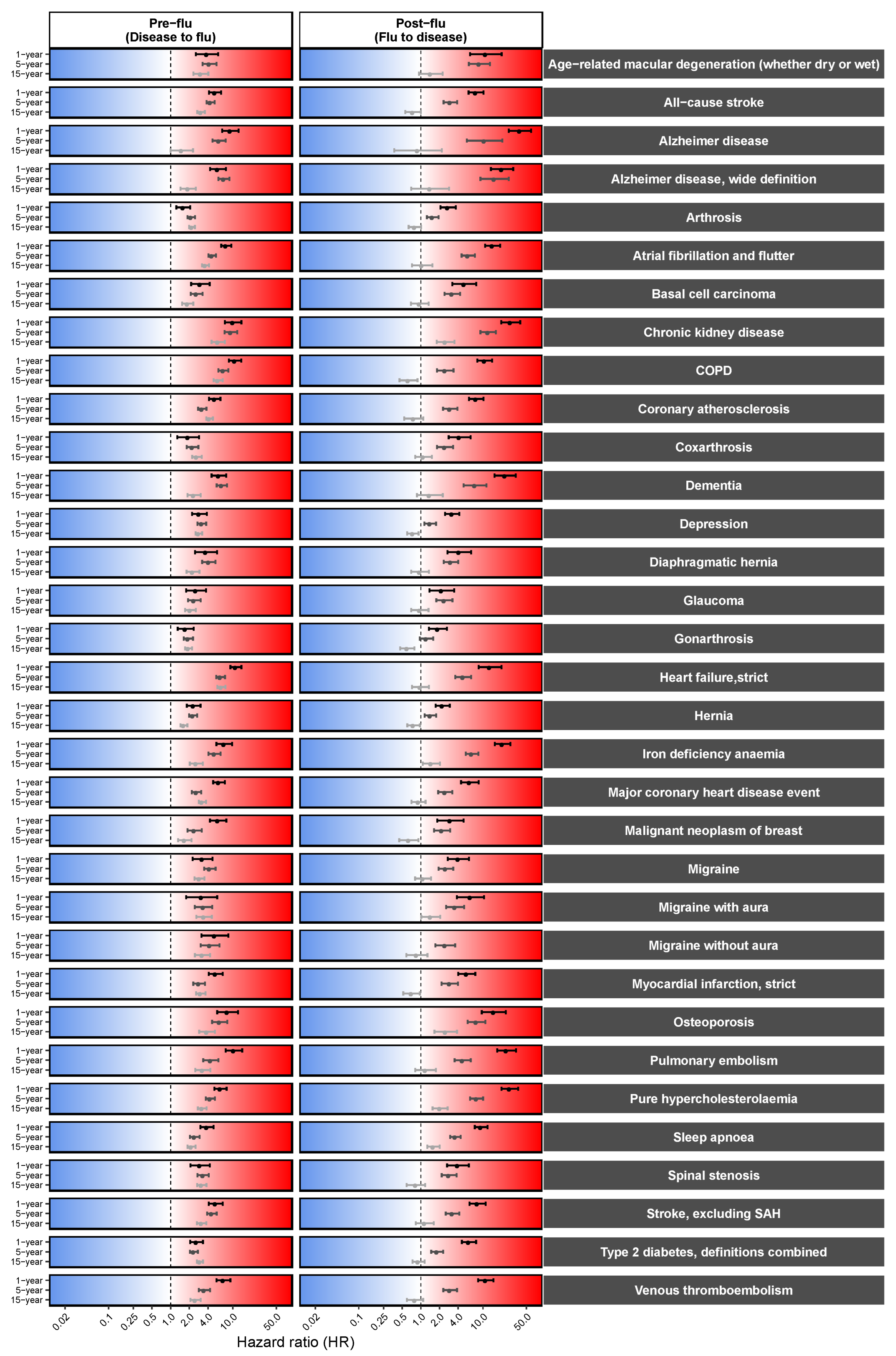

3.2. Pre-Existing Risks of Increased Influenza Predisposition

3.3. Long-Term, Multi-System Sequelae Following Influenza

3.4. Persistent Cardiovascular and Neurological Risk Signatures

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical and Public Health Implications

4.2. Policy Attention and Prioritization of Long Flu

4.3. Limitations of This Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DWAS | Disease-wide association study |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| PIP | Pandemic Influenza Preparedness |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| HDCP | Human Disease Continuum Project |

References

- Palese, P. Influenza: old and new threats. Nat Med 2004, 10, S82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Framework for the Sharing of Influenza Viruses and Access to Vaccines and Other Benefits. 2011. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/groups/pandemic-influenza-preparedness-(pip)-framework.

- WHO. Pandemic influenza preparedness framework: partnership contribution high-level implementation plan III 2024-2030. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240070141.

- Maggi, S.; Andrew, M.K.; de Boer, A. Podcast: Influenza-Associated Complications and the Impact of Vaccination on Public Health. Infect Dis Ther 2024, 13, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Sivan, M.; Perlowski, A.; Nikolich, J.Z. Long COVID: a clinical update. Lancet 2024, 404, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Xie, Y.; Topol, E.J.; Al-Aly, Z. Three-year outcomes of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nat Med 2024, 30, 1564–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Bowe, B.; Maddukuri, G.; Al-Aly, Z. Comparative evaluation of clinical manifestations and risk of death in patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 and seasonal influenza: cohort study. BMJ 2020, 371, m4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Choi, T.; Al-Aly, Z. Long-term outcomes following hospital admission for COVID-19 versus seasonal influenza: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2024, 24, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LUCKE, B.; WIGHT, T.; KIME, E. Pathologic anatomy and bacteriology of influenza: Epidemic of autumn, 1918. Archives of Internal Medicine 1919, 24, 154–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oseasohn, R.; Adelson, L.; Kaji, M. Clinicopathologic Study of Thirty-Three Fatal Cases of Asian Influenza. New England Journal of Medicine 1959, 260, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paddock, C.D.; Liu, L.; Denison, A.M.; Bartlett, J.H.; Holman, R.C.; Deleon-Carnes, M.; Emery, S.L.; Drew, C.P.; Shieh, W.J.; Uyeki, T.M.; et al. Myocardial injury and bacterial pneumonia contribute to the pathogenesis of fatal influenza B virus infection. J Infect Dis 2012, 205, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, M. Influenza myocarditis. Circ J 2010, 74, 2060–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, S.S.; Nealon, J.; Burkart, K.G.; Modin, D.; Biering-Sorensen, T.; Ortiz, J.R.; Vilchis-Tella, V.M.; Wallace, L.E.; Roth, G.; Mahe, C.; et al. Global, regional and national estimates of influenza-attributable ischemic heart disease mortality. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 55, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehme, A.K.; Luna, J.; Kulick, E.R.; Kamel, H.; Elkind, M.S.V. Influenza-like illness as a trigger for ischemic stroke. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2018, 5, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaarup, K.G.; Modin, D.; Nielsen, L.; Jensen, J.U.S.; Biering-Sorensen, T. Influenza and cardiovascular disease pathophysiology: strings attached. Eur Heart J Suppl 2023, 25, A5–A11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, E.J.; Rolfes, M.A.; O’Halloran, A.; Anderson, E.J.; Bennett, N.M.; Billing, L.; Chai, S.; Dufort, E.; Herlihy, R.; Kim, S.; et al. Acute Cardiovascular Events Associated With Influenza in Hospitalized Adults: A Cross-sectional Study. Ann Intern Med 2020, 173, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, A.; Thyagaturu, H.; Ashraf, M.; Carnahan, R.; Hodgson-Zingman, D. Effects of atrial fibrillation on outcomes of influenza hospitalization. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2022, 42, 101106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, T.C.; Thompson, M.; Meade, T.W. Recent respiratory infection and risk of cardiovascular disease: case-control study through a general practice database. Eur Heart J 2008, 29, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren-Gash, C.; Smeeth, L.; Hayward, A.C. Influenza as a trigger for acute myocardial infarction or death from cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 2009, 9, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Yang, W.; Sun, X.; Wang, L.; Ma, B.; Li, H.; Zhou, J. Association of influenza virus infection and inflammatory cytokines with acute myocardial infarction. Inflamm Res 2012, 61, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, J.C.; Schwartz, K.L.; Campitelli, M.A.; Chung, H.; Crowcroft, N.S.; Karnauchow, T.; Katz, K.; Ko, D.T.; McGeer, A.J.; McNally, D.; et al. Acute Myocardial Infarction after Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza Infection. N Engl J Med 2018, 378, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, A.R.; Riezebos-Brilman, A.; van Hout, D.; van Mourik, M.S.M.; Rumke, L.W.; de Hoog, M.L.A.; Vaartjes, I.; Bruijning-Verhagen, P. Influenza Infection and Acute Myocardial Infarction. NEJM Evid 2024, 3, EVIDoa2300361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, A.D.; Aron, S.L.; Gilbert, C.; Kumar, N.; Chen, P.; Eddy, A.; Zhang, L.; Zani, A.; Vargas-Maldonado, N.; Speaks, S.; et al. Influenza virus replication in cardiomyocytes drives heart dysfunction and fibrosis. Sci Adv 2022, 8, eabm5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N.; Demurtas, J.; Smith, L.; Michel, J.P.; Barbagallo, M.; Bolzetta, F.; Noale, M.; Maggi, S. Influenza vaccination reduces dementia risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2022, 73, 101534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, X.; Fu, K.; Duan, Y.; Wen, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhan, S. Prospective cohort study evaluating the association between influenza vaccination and neurodegenerative diseases. NPJ Vaccines 2024, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhbinder, A.S.; Ling, Y.; Hasan, O.; Jiang, X.; Kim, Y.; Phelps, K.N.; Schmandt, R.E.; Amran, A.; Coburn, R.; Ramesh, S.; et al. Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease Following Influenza Vaccination: A Claims-Based Cohort Study Using Propensity Score Matching. J Alzheimers Dis 2022, 88, 1061–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Lavie, C.J. Landscape of stroke comorbidities: A disease-wide association study. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2024, 86, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M. Disease-wide association study uncovers disease continuum network of unipolar depression. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2025, 92, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M. Disease continuum centered on Parkinson’s disease. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2025, 93, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M. Snapshot of disease continuum centered on Alzheimer’s disease: Exploring modifiable risk factors. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2025, 138, 111316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M. Thinking bipolar disorder as a symptom rather than a disease. Asian journal of psychiatry 2025, 109, 104540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurki, M.I.; Karjalainen, J.; Palta, P.; Sipila, T.P.; Kristiansson, K.; Donner, K.M.; Reeve, M.P.; Laivuori, H.; Aavikko, M.; Kaunisto, M.A.; et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature 2023, 613, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plana-Ripoll, O.; Pedersen, C.B.; Holtz, Y.; Benros, M.E.; Dalsgaard, S.; de Jonge, P.; Fan, C.C.; Degenhardt, L.; Ganna, A.; Greve, A.N.; et al. Exploring Comorbidity Within Mental Disorders Among a Danish National Population. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frobert, O.; Pedersen, I.B.; Hjelholt, A.J.; Erikstrup, C.; Cajander, S. The flu shot and cardiovascular Protection: Rethinking inflammation in ischemic heart disease. Atherosclerosis 2025, 120405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Lavie, C.J. COVID-19 susceptibility causally related to stroke risk: Using SARS-CoV-2 infection as a natural test of disease predisposition? Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2024, 86, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M. COVID-19 Predisposition Inherently Increases Cardiovascular Risk Before SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2025, 25, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.G.; Terebuh, P.; Kaelber, D.C.; Xu, R.; Davis, P.B. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and New-Onset Type 2 Diabetes Among Pediatric Patients, 2020 to 2022. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e2439444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiazGranados, C.A.; Robertson, C.A.; Talbot, H.K.; Landolfi, V.; Dunning, A.J.; Greenberg, D.P. Prevention of serious events in adults 65 years of age or older: A comparison between high-dose and standard-dose inactivated influenza vaccines. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4988–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frobert, O.; Gotberg, M.; Angeras, O.; Jonasson, L.; Erlinge, D.; Engstrom, T.; Persson, J.; Jensen, S.E.; Omerovic, E.; James, S.K.; et al. Design and rationale for the Influenza vaccination After Myocardial Infarction (IAMI) trial. A registry-based randomized clinical trial. Am Heart J 2017, 189, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.H.; Lam, G.K.L.; Shin, T.; Kim, J.; Krishnan, A.; Greenberg, D.P.; Chit, A. Efficacy and effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccination for older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Vaccines 2018, 17, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeb, M.; Dokainish, H.; Dans, A.; Palileo-Villanueva, L.M.; Roy, A.; Karaye, K.; Zhu, J.; Liang, Y.; Goma, F.; Damasceno, A.; et al. Randomized controlled trial of influenza vaccine in patients with heart failure to reduce adverse vascular events (IVVE): Rationale and design. Am Heart J 2019, 212, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonuguntla, K.; Patil, S.P.; Rojulpote, C. Impact of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines upon in-hospital mortality in patients with heart failure: a retrospective cohort study in the United States. European Heart Journal 2020, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeb, M.; Roy, A.; Dokainish, H.; Dans, A.; Palileo-Villanueva, L.M.; Karaye, K.; Zhu, J.; Liang, Y.; Goma, F.; Damasceno, A.; et al. Influenza vaccine to reduce adverse vascular events in patients with heart failure: a multinational randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health 2022, 10, e1835–e1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dermenchyan, A.; Choi, K.R.; Bokhoor, P.R.; Cho, D.J.; Delavin, N.L.A.; Chima-Melton, C.; Han, M.A.; Fonarow, G.C. Receipt of respiratory vaccines among patients with heart failure in a multicenter health system registry. Vaccine 2025, 46, 126682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Choi, T.; Al-Aly, Z. Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Pre-Delta, Delta, and Omicron Eras. N Engl J Med 2024, 391, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrouzi, B.; Bhatt, D.L.; Cannon, C.P.; Vardeny, O.; Lee, D.S.; Solomon, S.D.; Udell, J.A. Association of Influenza Vaccination With Cardiovascular Risk: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e228873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belongia, E.A.; Simpson, M.D.; King, J.P.; Sundaram, M.E.; Kelley, N.S.; Osterholm, M.T.; McLean, H.Q. Variable influenza vaccine effectiveness by subtype: a systematic review and meta-analysis of test-negative design studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2016, 16, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infections, G.B.D.L.R.; Antimicrobial Resistance, C. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality burden of non-COVID-19 lower respiratory infections and aetiologies, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Infect Dis 2024, 24, 974–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).