Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Crystals Under External Anisotropic Mechanical Conditions

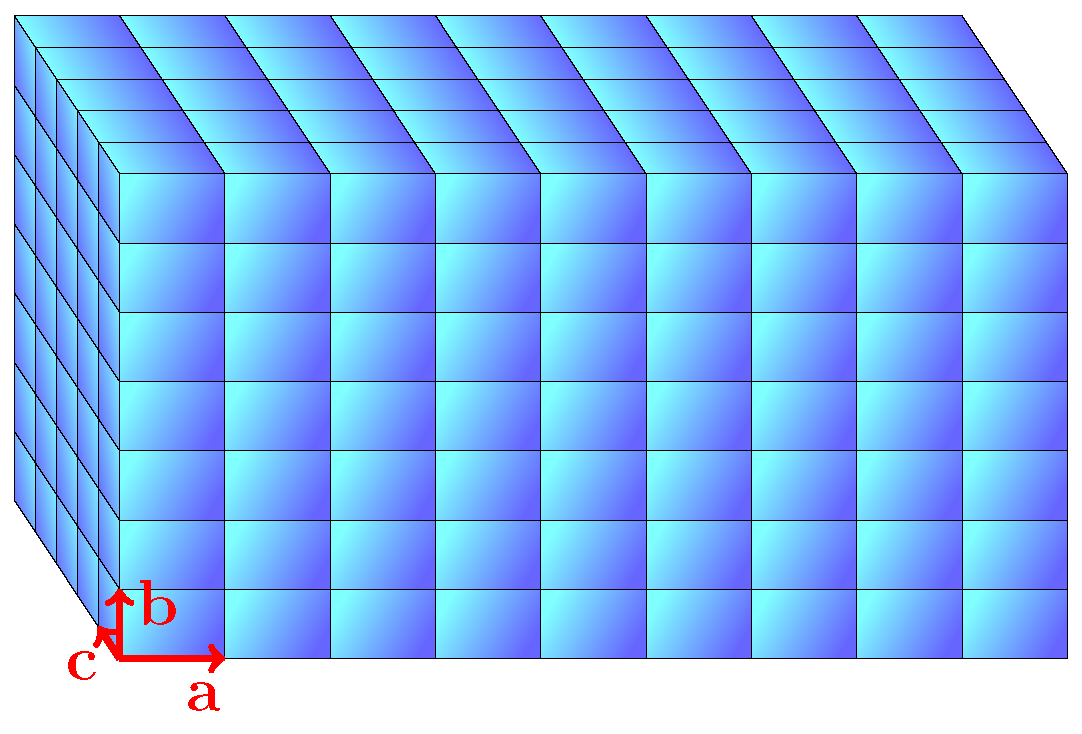

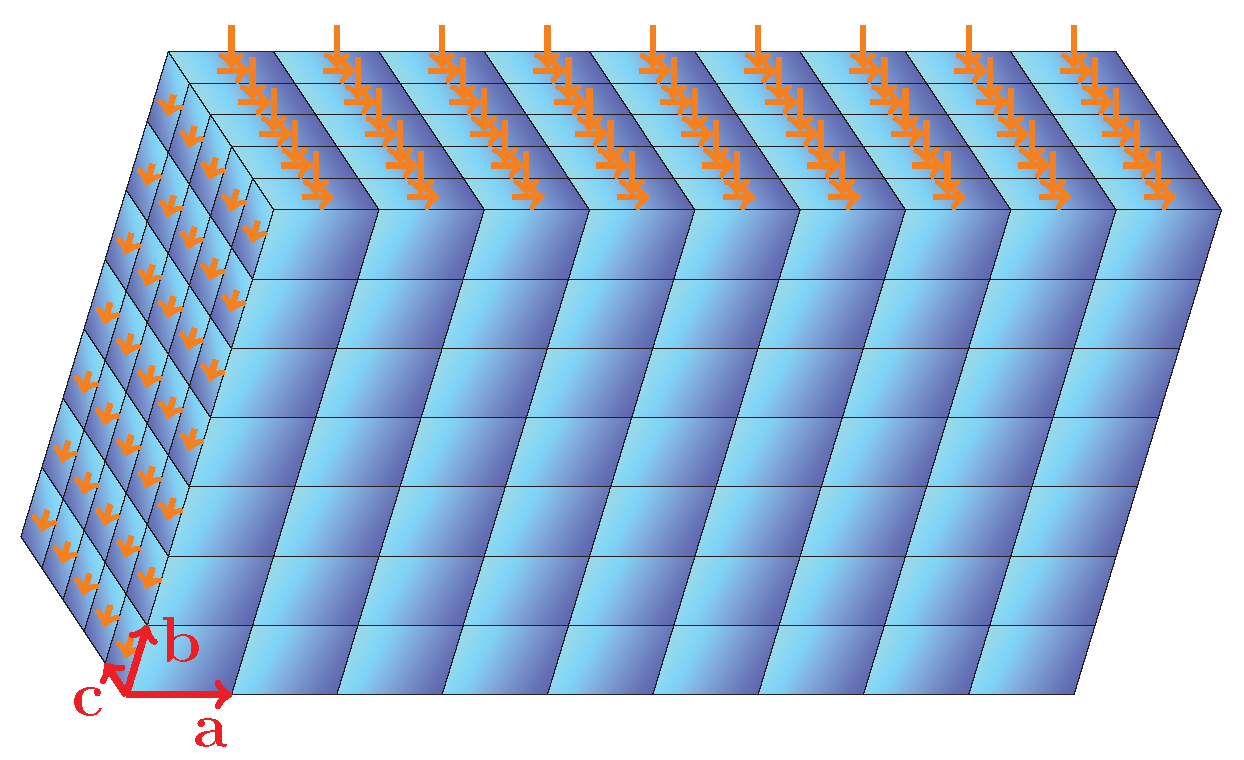

2.1. Crystal Period Vectors and External Stress

2.2. The Derivation of the EOS

2.3. Tuckerman’s Internal Stress

2.4. Isotropic External Pressure

3. Non-Crystal System Under General External Stress

3.1. The EOS

3.2. The Detailed MMEC in Classical Physics

3.2.1. The Thermal Pressure

3.2.2. The Derivative of Potential Contribution with Respect to the Period Vectors

3.2.3. The Pair-Interaction Contributions

3.2.4. The Many-Body Interaction Contributions

3.2.5. Conclusions

4. Summary

Acknowledgments

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boyle%27s_law.

- M.L. Bellac, F. Mortessagne, G.G. Batrouni, Equilibrium and Non-equilibrium Statistical Thermodynamics (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004).

- O.L. Anderson, Equations of State of Solids for Geophysics and Ceramic Science (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1995).

- Liu, G. A new equation for period vectors of crystals under external stress and temperature in statistical physics: mechanical equilibrium condition and equation of state. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 136, 48 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. Crystal Period Vectors under External Stress in Statistical Physics. Preprints 2019, 2019040076. [CrossRef]

- M.E. Tuckerman, Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Molecular Simulation (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2010).

- G. Liu, Can. J. Phys., 93, 974-978 (2015),arXiv:cond-mat/0209372 (version 16).

- G. Liu, Preprints.org 2017, 2017090030. [CrossRef]

- G. Liu, E.G. Wang, D.S. Wang, Chin. Phys. Lett. (1997). [CrossRef]

- G. Liu, E.G. Wang, Solid State Commun. (1998). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).