Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.2.1. SAR Backscatter (SnowSAR and SWESARR)

2.2.2. Snow Pit Data

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Co-Locating Pits and SAR Measurements

2.3.2. Models

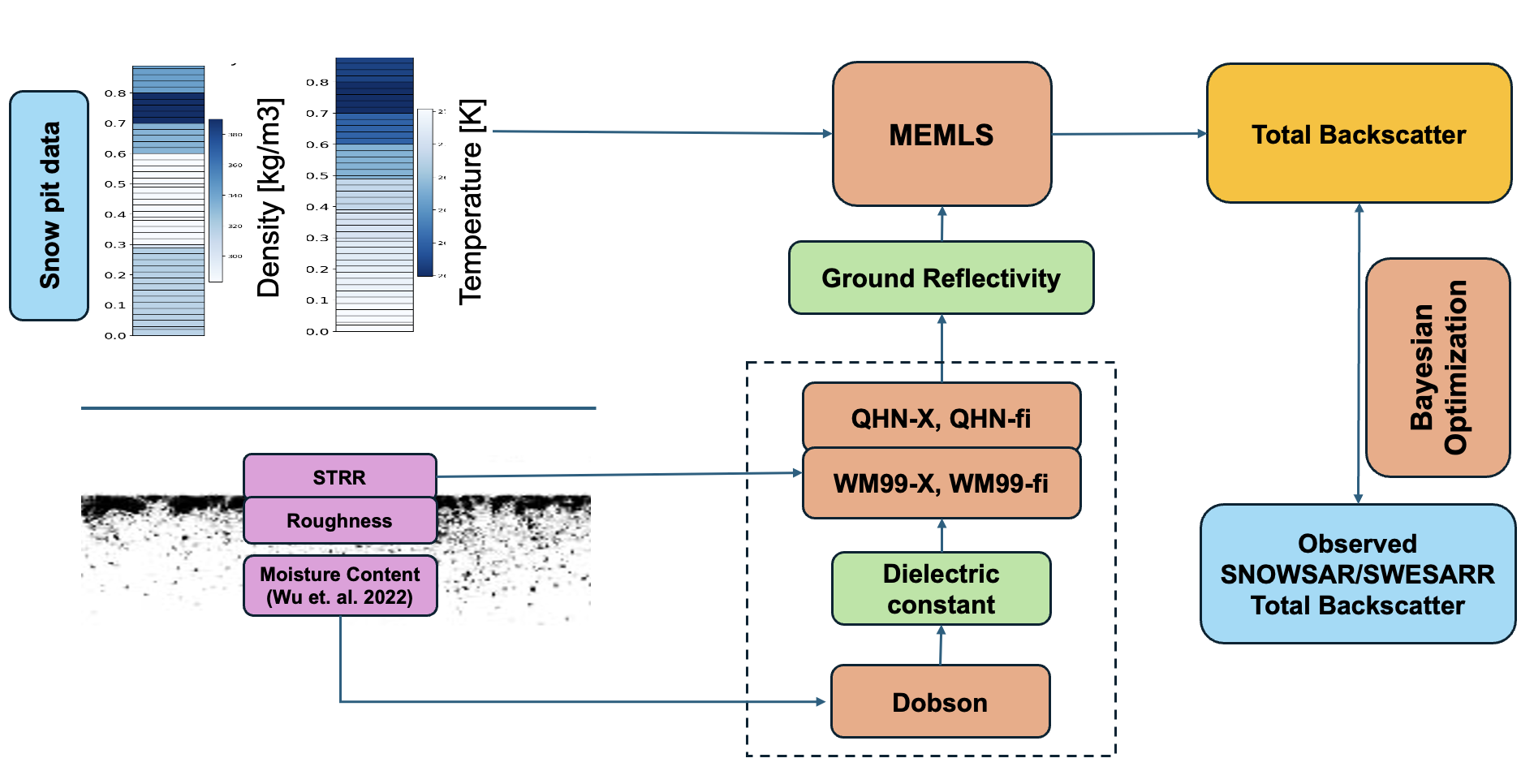

- MEMLS3&a snow backscattering model

- b.

- Soil reflectivity models

- c.

- Bayesian estimation of soil parameters

2.4. Quantification of Error

3. Results

3.1. Soil Reflectivity Model

3.2. SnowSAR Bias Sources - Surficial Melt

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Ground Parameters

3.4. Bayesian Parameter Estimation

3.4.1. Dual Polarization

3.4.2. Single Polarization

3.5. Error Quantification

| Pit | Angle (θ0) | STRR mean (%) | Median (%) | HDI_L (%) | HDI_U (%) | SD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 42.45 | 68.81 | 68.84 | 59.85 | 77.77 | 4.53 |

| B1 | 42.75 | 65.8 | 65.86 | 56.93 | 74.49 | 4.45 |

| B1 | 44.5 | 72.97 | 72.98 | 63.54 | 82.8 | 4.89 |

| B2 | 43.75 | 62.59 | 62.6 | 55.03 | 70.59 | 3.96 |

| B2 | 45.05 | 66.29 | 66.34 | 57.46 | 75.14 | 4.47 |

| B3 | 42.05 | 73.32 | 73.34 | 63.36 | 83.12 | 5.06 |

| B3 | 42.65 | 59.81 | 59.81 | 52.11 | 67.46 | 3.93 |

| B3 | 44.45 | 70.87 | 70.91 | 61.63 | 80.04 | 4.64 |

| B4 | 43.75 | 62.59 | 62.6 | 55.03 | 70.59 | 3.96 |

| B4 | 46.8 | 55.7 | 55.65 | 48.53 | 63.57 | 3.82 |

| B4 | 47.95 | 70.9 | 70.93 | 61.67 | 80.09 | 4.65 |

| B5 | 41.9 | 65.93 | 65.97 | 57.27 | 75.11 | 4.47 |

| A13 | 44 | 73.29 | 73.29 | 63.38 | 83.2 | 5.04 |

| A13 | 51 | 71.09 | 71.14 | 61.53 | 80.49 | 4.75 |

| A5 | 42 | 67.41 | 67.43 | 58.86 | 76.09 | 4.41 |

| A5 | 49 | 66.29 | 66.3 | 57.61 | 75.56 | 4.55 |

| A16 | 42 | 65.96 | 65.97 | 56.86 | 74.61 | 4.49 |

| A16 | 49 | 61.17 | 61.16 | 53.38 | 68.72 | 3.92 |

| A12 | 43 | 70.09 | 70.1 | 60.74 | 79.32 | 4.61 |

| A12 | 49 | 64.48 | 64.55 | 56.18 | 72.54 | 4.16 |

| A11 | 41 | 67.71 | 67.67 | 58.87 | 76.52 | 4.51 |

| A11 | 49 | 61.17 | 61.16 | 53.38 | 68.72 | 3.92 |

| A14 | 42 | 67.41 | 67.43 | 58.86 | 76.09 | 4.41 |

| A14 | 49 | 64.48 | 64.55 | 56.18 | 72.54 | 4.16 |

| A6 | 37 | 64.08 | 64.17 | 55.74 | 72.31 | 4.18 |

| A6 | 48 | 72.19 | 72.23 | 62.82 | 81.42 | 4.7 |

| A7 | 37 | 76.66 | 76.67 | 68.09 | 85.42 | 4.4 |

| A8 | 37 | 64.08 | 64.17 | 55.74 | 72.31 | 4.18 |

| A8 | 48 | 71.14 | 71.28 | 61.7 | 79.89 | 4.64 |

| A9 | 37 | 64.08 | 64.17 | 55.74 | 72.31 | 4.18 |

| A9 | 48 | 65.07 | 65.13 | 56.65 | 73.84 | 4.37 |

| A10 | 37 | 64.08 | 64.17 | 55.74 | 72.31 | 4.18 |

| A10 | 48 | 65.07 | 65.13 | 56.65 | 73.84 | 4.37 |

| A15 | 37 | 64.08 | 64.17 | 55.74 | 72.31 | 4.18 |

| A15 | 48 | 58.37 | 58.34 | 50.99 | 66.13 | 3.86 |

| Pit | Angle (θ0) | SR_Mean (cm) | Median (cm) | HDI_L (cm) | HDI_U (cm) | SD (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 42.45 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0 | 1.54 | 0.52 |

| B1 | 42.75 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0 | 1.13 | 0.41 |

| B1 | 44.5 | 1.38 | 1.42 | 0 | 2.18 | 0.53 |

| B2 | 43.75 | 0.23 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| B2 | 45.05 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0 | 1.23 | 0.44 |

| B3 | 42.05 | 1.36 | 1.4 | 0 | 2.19 | 0.55 |

| B3 | 42.65 | 0.17 | 0 | 0 | 0.68 | 0.25 |

| B3 | 44.45 | 1.06 | 1.13 | 0 | 1.88 | 0.54 |

| B4 | 43.75 | 0.23 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| B4 | 46.8 | 0.12 | 0 | 0 | 0.56 | 0.2 |

| B4 | 47.95 | 1.07 | 1.12 | 0 | 1.9 | 0.56 |

| B5 | 41.9 | 0.4 | 0.34 | 0 | 1.13 | 0.41 |

| A13 | 44 | 1.38 | 1.43 | 0 | 2.19 | 0.53 |

| A13 | 51 | 1.06 | 1.13 | 0 | 1.87 | 0.55 |

| A5 | 42 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0 | 1.3 | 0.47 |

| A5 | 49 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0 | 1.23 | 0.44 |

| A16 | 42 | 0.4 | 0.33 | 0 | 1.13 | 0.41 |

| A16 | 49 | 0.21 | 0 | 0 | 0.77 | 0.28 |

| A12 | 43 | 0.9 | 0.96 | 0 | 1.73 | 0.55 |

| A12 | 49 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0 | 1 | 0.37 |

| A11 | 41 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0 | 1.35 | 0.48 |

| A11 | 49 | 0.21 | 0 | 0 | 0.77 | 0.28 |

| A14 | 42 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0 | 1.3 | 0.47 |

| A14 | 49 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0 | 1 | 0.37 |

| A6 | 37 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 0.86 | 0.32 |

| A6 | 48 | 1.23 | 1.26 | 0 | 2.02 | 0.52 |

| A7 | 37 | 1.83 | 1.82 | 1.1 | 2.56 | 0.38 |

| A8 | 37 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 0.86 | 0.32 |

| A8 | 48 | 1.04 | 1.1 | 0 | 1.85 | 0.54 |

| A9 | 37 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 0.86 | 0.32 |

| A9 | 48 | 0.37 | 0.27 | 0 | 1.09 | 0.4 |

| A10 | 37 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 0.86 | 0.32 |

| A10 | 48 | 0.37 | 0.27 | 0 | 1.09 | 0.4 |

| A15 | 37 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 0.86 | 0.32 |

| A15 | 48 | 0.15 | 0 | 0 | 0.65 | 0.24 |

| Pit | Angle (θ0) | Mv_Mean | Median | HDI_L | HDI_U | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 42.45 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.046 | 0.082 | 0.009 |

| B1 | 42.75 | 0.084 | 0.084 | 0.069 | 0.095 | 0.009 |

| B1 | 44.5 | 0.038 | 0.038 | 0.02 | 0.053 | 0.01 |

| B2 | 43.75 | 0.093 | 0.095 | 0.081 | 0.095 | 0.005 |

| B2 | 45.05 | 0.08 | 0.079 | 0.065 | 0.095 | 0.01 |

| B3 | 42.05 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.02 | 0.048 | 0.01 |

| B3 | 42.65 | 0.094 | 0.095 | 0.087 | 0.095 | 0.003 |

| B3 | 44.45 | 0.054 | 0.053 | 0.037 | 0.072 | 0.009 |

| B4 | 43.75 | 0.093 | 0.095 | 0.081 | 0.095 | 0.005 |

| B4 | 46.8 | 0.095 | 0.095 | 0.093 | 0.095 | 0.001 |

| B4 | 47.95 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 0.036 | 0.071 | 0.009 |

| B5 | 41.9 | 0.082 | 0.081 | 0.066 | 0.095 | 0.01 |

| A13 | 44 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.02 | 0.052 | 0.01 |

| A13 | 51 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.036 | 0.069 | 0.008 |

| A5 | 42 | 0.071 | 0.071 | 0.057 | 0.095 | 0.009 |

| A5 | 49 | 0.081 | 0.08 | 0.066 | 0.095 | 0.01 |

| A16 | 42 | 0.082 | 0.081 | 0.066 | 0.095 | 0.01 |

| A16 | 49 | 0.094 | 0.095 | 0.086 | 0.095 | 0.003 |

| A12 | 43 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 0.041 | 0.075 | 0.009 |

| A12 | 49 | 0.09 | 0.095 | 0.075 | 0.095 | 0.007 |

| A11 | 41 | 0.069 | 0.069 | 0.051 | 0.088 | 0.009 |

| A11 | 49 | 0.094 | 0.095 | 0.086 | 0.095 | 0.003 |

| A14 | 42 | 0.071 | 0.071 | 0.057 | 0.095 | 0.009 |

| A14 | 49 | 0.09 | 0.095 | 0.075 | 0.095 | 0.007 |

| A6 | 37 | 0.09 | 0.095 | 0.075 | 0.095 | 0.007 |

| A6 | 48 | 0.045 | 0.045 | 0.03 | 0.064 | 0.009 |

| A7 | 37 | 0.021 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.029 | 0.003 |

| A8 | 37 | 0.09 | 0.095 | 0.075 | 0.095 | 0.007 |

| A8 | 48 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 0.035 | 0.068 | 0.009 |

| A9 | 37 | 0.09 | 0.095 | 0.075 | 0.095 | 0.007 |

| A9 | 48 | 0.088 | 0.091 | 0.072 | 0.095 | 0.008 |

| A10 | 37 | 0.09 | 0.095 | 0.075 | 0.095 | 0.007 |

| A10 | 48 | 0.088 | 0.091 | 0.072 | 0.095 | 0.008 |

| A15 | 37 | 0.09 | 0.095 | 0.075 | 0.095 | 0.007 |

| A15 | 48 | 0.094 | 0.095 | 0.09 | 0.095 | 0.002 |

| Pit | Angle (θ0) | VV_Mean | Median | HDI_L | HDI_U | SD | Bias | Obs_VV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 42.45 | -16.11 | -16.11 | -16.97 | -15.21 | 0.45 | 0.32 | -16.42 |

| B1 | 42.75 | -14.49 | -14.49 | -15.35 | -13.65 | 0.44 | -0.35 | -14.15 |

| B1 | 44.5 | -19.64 | -19.64 | -20.6 | -18.71 | 0.49 | 1.17 | -20.8 |

| B2 | 43.75 | -13.93 | -13.9 | -14.61 | -13.27 | 0.35 | -0.72 | -13.21 |

| B2 | 45.05 | -15.41 | -15.4 | -16.28 | -14.54 | 0.45 | 0.55 | -15.95 |

| B3 | 42.05 | -19.63 | -19.63 | -20.58 | -18.67 | 0.49 | 0.96 | -20.59 |

| B3 | 42.65 | -13.35 | -13.34 | -13.93 | -12.75 | 0.3 | -0.84 | -12.51 |

| B3 | 44.45 | -17.86 | -17.86 | -18.79 | -16.98 | 0.46 | 0.71 | -18.57 |

| B4 | 43.75 | -13.93 | -13.9 | -14.61 | -13.27 | 0.35 | -0.25 | -13.68 |

| B4 | 46.8 | -14.05 | -14.04 | -14.59 | -13.54 | 0.27 | -1.98 | -12.06 |

| B4 | 47.95 | -18.84 | -18.84 | -19.75 | -17.93 | 0.46 | 0.27 | -19.11 |

| B5 | 41.9 | -14.45 | -14.44 | -15.33 | -13.61 | 0.44 | -0.31 | -14.14 |

| A13 | 44 | -19.62 | -19.62 | -20.6 | -18.71 | 0.49 | 1.22 | -20.84 |

| A13 | 51 | -19.83 | -19.83 | -20.74 | -18.95 | 0.46 | 0.62 | -20.45 |

| A5 | 42 | -15.28 | -15.28 | -16.14 | -14.43 | 0.44 | 0.37 | -15.65 |

| A5 | 49 | -16.42 | -16.42 | -17.29 | -15.5 | 0.45 | -0.09 | -16.33 |

| A16 | 42 | -14.46 | -14.45 | -15.33 | -13.59 | 0.44 | 0.31 | -14.77 |

| A16 | 49 | -15.14 | -15.13 | -15.78 | -14.55 | 0.32 | -0.3 | -14.85 |

| A12 | 43 | -16.95 | -16.94 | -17.86 | -16.06 | 0.46 | 0.87 | -17.82 |

| A12 | 49 | -15.66 | -15.64 | -16.47 | -14.92 | 0.4 | 0.15 | -15.81 |

| A11 | 41 | -15.22 | -15.22 | -16.08 | -14.34 | 0.44 | 0.66 | -15.88 |

| A11 | 49 | -15.14 | -15.13 | -15.78 | -14.55 | 0.32 | -0.7 | -14.44 |

| A14 | 42 | -15.28 | -15.28 | -16.14 | -14.43 | 0.44 | -0.05 | -15.23 |

| A14 | 49 | -15.66 | -15.64 | -16.47 | -14.92 | 0.4 | -0.63 | -15.04 |

| A6 | 37 | -12.73 | -12.71 | -13.51 | -12.01 | 0.39 | 0.22 | -12.95 |

| A6 | 48 | -19.73 | -19.72 | -20.68 | -18.82 | 0.47 | 0.65 | -20.38 |

| A7 | 37 | -20.29 | -20.3 | -21.12 | -19.42 | 0.43 | 0.84 | -21.13 |

| A8 | 37 | -12.73 | -12.71 | -13.51 | -12.01 | 0.39 | -0.09 | -12.64 |

| A8 | 48 | -18.84 | -18.84 | -19.74 | -17.91 | 0.47 | 0.33 | -19.18 |

| A9 | 37 | -12.73 | -12.71 | -13.51 | -12.01 | 0.39 | 0.06 | -12.79 |

| A9 | 48 | -15.58 | -15.56 | -16.39 | -14.74 | 0.42 | 0.3 | -15.87 |

| A10 | 37 | -12.73 | -12.71 | -13.51 | -12.01 | 0.39 | 0.16 | -12.89 |

| A10 | 48 | -15.58 | -15.56 | -16.39 | -14.74 | 0.42 | 0.27 | -15.84 |

| A15 | 37 | -12.73 | -12.71 | -13.51 | -12.01 | 0.39 | -0.08 | -12.65 |

| A15 | 48 | -14.59 | -14.58 | -15.16 | -14.04 | 0.29 | -1.31 | -13.28 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RTM | Radiative Transfer Model |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| STRR | Specular to Total Reflectivity Ratio |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| LULC | Land Use Land Cover |

| MCMC | Monte Carlo Markov Chain |

Appendix A

| Pit | Angle | Soil Moisture (MCSE) |

Soil Moisture (Rhat) | STRR (MCSE) | STRR (Rhat) | Surface Roughness (MCSE) | Surface Roughness (Rhat) | VV Backscatter (MCSE) | VV Backscatter (Rhat) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 40.25 | 6.00E-05 | 1.00026 | 0.00235 | 1.01104 | 0.00012 | 1.00173 | 0.01006 | 1.00305 |

| B1 | 42.45 | 0.00033 | 1.00179 | 0.00266 | 1.00625 | 0.00013 | 1.00181 | 0.007 | 1.00438 |

| B1 | 42.75 | 0.00029 | 1.00009 | 0.00229 | 1.00449 | 8.00E-05 | 1.0014 | 0.00736 | 1.00132 |

| B1 | 44.5 | 0.00041 | 1.00547 | 0.00302 | 1.01021 | 0.00017 | 1.00154 | 0.00751 | 1.00003 |

| B2 | 39.95 | 0.00042 | 1.00152 | 0.00301 | 1.00886 | 0.00018 | 0.99995 | 0.00767 | 1.00044 |

| B2 | 43.75 | 9.00E-05 | 0.99998 | 0.0019 | 1.00956 | 5.00E-05 | 0.99995 | 0.0096 | 1.00591 |

| B2 | 45.05 | 0.00035 | 0.99995 | 0.0025 | 1.00624 | 9.00E-05 | 1.00022 | 0.00647 | 1.00217 |

| A1 | 32 | 0 | 1.00004 | 0.00187 | 1.00702 | 1.00E-05 | 1.00007 | 0.01 | 1.00696 |

| A1 | 54 | 3.00E-05 | 1.00012 | 0.00195 | 1.00801 | 4.00E-05 | 0.99995 | 0.01247 | 1.00698 |

| B3 | 42.05 | 0.00046 | 1.00512 | 0.00321 | 1.01218 | 0.00018 | 1.00017 | 0.00824 | 0.99995 |

| B3 | 42.65 | 4.00E-05 | 0.99998 | 0.00192 | 1.00801 | 4.00E-05 | 0.99997 | 0.01174 | 1.00631 |

| B3 | 44.45 | 0.00038 | 1.00121 | 0.00263 | 1.00872 | 0.00016 | 0.99997 | 0.00644 | 1.00059 |

| B4 | 43.75 | 9.00E-05 | 0.99998 | 0.0019 | 1.00956 | 5.00E-05 | 0.99995 | 0.0096 | 1.00591 |

| B4 | 46.8 | 2.00E-05 | 1.00013 | 0.00189 | 1.01086 | 3.00E-05 | 0.99999 | 0.01206 | 1.00957 |

| B4 | 47.95 | 0.00033 | 0.99998 | 0.00268 | 1.0085 | 0.00016 | 1.00153 | 0.00628 | 1.00186 |

| B5 | 41.9 | 0.00031 | 0.99995 | 0.00243 | 1.00282 | 8.00E-05 | 1.00027 | 0.0065 | 1.00094 |

| A13 | 44 | 0.00057 | 1.00167 | 0.00327 | 1.01397 | 0.00016 | 1.00024 | 0.00857 | 1.00036 |

| A13 | 51 | 0.00033 | 1.00039 | 0.00281 | 1.01232 | 0.00015 | 1.00079 | 0.00643 | 1.00073 |

| A5 | 42 | 0.00033 | 1.00029 | 0.00233 | 1.01348 | 0.00011 | 1.0009 | 0.00746 | 1.00178 |

| A5 | 49 | 0.00034 | 1.00003 | 0.00254 | 1.01057 | 9.00E-05 | 1.00092 | 0.00673 | 1.00169 |

| A16 | 42 | 0.00034 | 1.00004 | 0.0025 | 1.00345 | 8.00E-05 | 1.00016 | 0.00642 | 1.00052 |

| A16 | 49 | 6.00E-05 | 0.99995 | 0.00192 | 1.00722 | 5.00E-05 | 0.99995 | 0.01122 | 1.0048 |

| A12 | 43 | 0.00034 | 1.00002 | 0.00266 | 1.00781 | 0.00016 | 1.00179 | 0.0063 | 1.00119 |

| A12 | 49 | 0.00017 | 0.99999 | 0.00214 | 1.00868 | 6.00E-05 | 1.00042 | 0.00819 | 1.00242 |

| A11 | 41 | 0.00033 | 1.00011 | 0.0026 | 1.01033 | 0.00011 | 1.00046 | 0.00698 | 1.00194 |

| A11 | 49 | 6.00E-05 | 0.99995 | 0.00192 | 1.00722 | 5.00E-05 | 0.99995 | 0.01122 | 1.0048 |

| A14 | 42 | 0.00033 | 1.00029 | 0.00233 | 1.01348 | 0.00011 | 1.0009 | 0.00746 | 1.00178 |

| A14 | 49 | 0.00017 | 0.99999 | 0.00214 | 1.00868 | 6.00E-05 | 1.00042 | 0.00819 | 1.00242 |

| A6 | 37 | 0.00016 | 1.00001 | 0.00215 | 1.0094 | 6.00E-05 | 1.00032 | 0.00868 | 1.00343 |

| A6 | 48 | 0.00033 | 1.00085 | 0.00272 | 1.00078 | 0.00015 | 1.00061 | 0.00641 | 1.00117 |

| A7 | 37 | 8.00E-05 | 1.00075 | 0.0024 | 1.00759 | 0.00011 | 1.00056 | 0.00969 | 1.00168 |

| A8 | 37 | 0.00016 | 1.00001 | 0.00215 | 1.0094 | 6.00E-05 | 1.00032 | 0.00868 | 1.00343 |

| A8 | 48 | 0.00035 | 0.99996 | 0.00265 | 1.00425 | 0.00016 | 1.00015 | 0.0065 | 1.00074 |

| A9 | 37 | 0.00016 | 1.00001 | 0.00215 | 1.0094 | 6.00E-05 | 1.00032 | 0.00868 | 1.00343 |

| A9 | 48 | 0.00024 | 1.0001 | 0.00229 | 1.00639 | 7.00E-05 | 1.00013 | 0.00748 | 1.00165 |

| A10 | 37 | 0.00016 | 1.00001 | 0.00215 | 1.0094 | 6.00E-05 | 1.00032 | 0.00868 | 1.00343 |

| A10 | 48 | 0.00024 | 1.0001 | 0.00229 | 1.00639 | 7.00E-05 | 1.00013 | 0.00748 | 1.00165 |

| A15 | 37 | 0.00016 | 1.00001 | 0.00215 | 1.0094 | 6.00E-05 | 1.00032 | 0.00868 | 1.00343 |

| A15 | 48 | 3.00E-05 | 1.00019 | 0.00185 | 1.00859 | 4.00E-05 | 0.99996 | 0.01184 | 1.00769 |

| NSDIC Pit name | Pit Name (used in the study) | Latitude | Longitude | Date | Incidence Angle (θ0) |

Realization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28S | A1 | 39.0122478 | -108.1379938 | 2017-02-25 | 32 | 1 |

| 54 | 2 | |||||

| 78N | A2 | 39.04342878 | -107.9202531 | 2017-02-25 | 31 | 1 |

| 40 | 2 | |||||

| 92E | A3 | 39.0510518 | -107.885109 | 2017-02-22 | 41 | 1 |

| 48 | 2 | |||||

| 92W | A4 | 39.0510159 | -107.8876494 | 2017-02-22 | 42 | 1 |

| 49 | 2 | |||||

| KC1C | A5 | 39.01363394 | -108.1838735 | 2017-02-20 | 42 | 1 |

| 49 | 2 | |||||

| MTR4_0000 | A6 | 39.0300503 | -108.0331353 | 2017-02-24 | 37 | 1 |

| 48 | 2 | |||||

| MTR4_0800 | A7 | 39.03005659 | -108.0332395 | 2017-02-24 | 37 | 1 |

| 48 | 2 | |||||

| MTR4_1390 | A8 | 39.03005509 | -108.0332972 | 2017-02-24 | 37 | 1 |

| 48 | 2 | |||||

| MTR4_2000 | A9 | 39.03005329 | -108.0333664 | 2017-02-24 | 37 | 1 |

| 48 | 2 | |||||

| MTR4_2500 | A10 | 39.03005179 | -108.0334241 | 2017-02-24 | 48 | 1 |

| 37 | 2 | |||||

| KC1S* | A11 | 39.01344468 | -108.1838766 | 2017-02-20 | 41 | 1 |

| 49 | 2 | |||||

| KC1N* | A12 | 39.01381389 | -108.1838816 | 2017-02-20 | 43 | 1 |

| 49 | 2 | |||||

| 67N* | A13 | 39.03245119 | -108.0291492 | 2017-02-22 | 44 | 1 |

| 51 | 2 | |||||

| KC1W* | A14 | 39.01362669 | -108.1841388 | 2017-02-20 | 42 | 1 |

| 49 | 2 | |||||

| MTR4_4500* | A15 | 39.03005478 | -108.0336552 | 2017-02-24 | 37 | 1 |

| 48 | 2 | |||||

| KC1E* | A16 | 39.01363219 | -108.1836079 | 2017-02-20 | 42 | 1 |

| 49 | 2 | |||||

| 1S1 | B1 | 39.02119889 | -108.20559 | 2020-01-29 | 42.45 | 1 |

| 40.25 | 2 | |||||

| 44.5 | 3 | |||||

| 42.75 | 4 | |||||

| 41.5 | 5 | |||||

| 1S2 | B2 | 39.019948 | -108.203396 | 2020-02-08 | 39.95 | 1 |

| 44.55 | 2 | |||||

| 42.95 | 3 | |||||

| 46.9 | 4 | |||||

| 45.05 | 5 | |||||

| 43.75 | 6 | |||||

| 2S3 | B3 | 39.021089 | -108.202889 | 2020-01-29 | 42.05 | 1 |

| 44.45 | 2 | |||||

| 42.65 | 3 | |||||

| 41.35 | 4 | |||||

| 2S4 | B4 | 39.017951 | -108.201292 | 2020-02-05 | 43.75 | 1 |

| 47.95 | 2 | |||||

| 46.8 | 3 | |||||

| 2S7 | B5 | 39.01866002 | -108.197788 | 2020-02-08 | 41.9 | 1 |

| 3S5 | B6 | 39.01911256 | -108.1986242 | 2020-01-29 | 41.15 | 2 |

References

- Barnett, T.P.; Adam, J.C.; Lettenmaier, D.P. Potential impacts of a warming climate on water availability in snow-dominated regions. Nature 2005, 438, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturm, M.; Goldstein, M.A.; Parr, C. Water and life from snow: A trillion dollar science question. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 3534–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulliainen, J. Retrieval of Regional Snow Water Equivalent from Space-Borne Passive Microwave Observations. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2001, 75, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derksen, C.; Walker, A.; Goodison, B. A comparison of 18 winter seasons of in situ and passive microwave-derived snow water equivalent estimates in Western Canada. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2003, 88, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, C.L.; Aziz, O.; Tootle, G.A.; Lakshmi, V.; Kerr, G. A comparison of SNOTEL and AMSR-E snow water equivalent datasets in western U.S. watersheds. In Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on Knowledge Discovery from Sensor Data; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, R.E. Land Surface Processes and Climate—Surface Albedos and Energy Balance. In Advances in Geophysics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1983; Volume 25, pp. 305–353. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Mocko, D.; Vuyovich, C.; Peters-Lidard, C. Impact of Surface Albedo Assimilation on Snow Estimation. Remote. Sens. 2020, 12, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, K.J.; Brown, R.D.; Derksen, C.; Painter, T.H. Estimating snow-cover trends from space. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 924–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, T.; Li, X.; Jin, R.; Huang, C. Assimilating passive microwave remote sensing data into a land surface model to improve the estimation of snow depth. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2014, 143, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J. Application of Passive and Active Microwave Remote Sensing for Snow Water Equivalent Estimation. The Ohio State University, 2017. Available online: https://etd.ohiolink.edu/acprod/odb_etd/etd/r/1501/10?clear=10&p10_accession_num=osu149737615724025.

- Kang, D.H.; Barros, A.P.; Dery, S.J. Evaluating Passive Microwave Radiometry for the Dynamical Transition From Dry to Wet Snowpacks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2013, 52, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proksch, M.; Mätzler, C.; Wiesmann, A.; Lemmetyinen, J.; Schwank, M.; Löwe, H.; Schneebeli, M. MEMLS3&a: Microwave Emission Model of Layered Snowpacks adapted to include backscattering. Geosci. Model Dev. 2015, 8, 2611–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesmann, A.; Mätzler, C. Microwave Emission Model of Layered Snowpacks. Remote. Sens. Environ. 1999, 70, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, L.; Pan, J.; Liang, D.; Li, Z.; Cline, D.W.; Tan, Y. Modeling Active Microwave Remote Sensing of Snow Using Dense Media Radiative Transfer (DMRT) Theory With Multiple-Scattering Effects. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2007, 45, 990–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, G.; Sandells, M.; Löwe, H. SMRT: an active–passive microwave radiative transfer model for snow with multiple microstructure and scattering formulations (v1.0). Geosci. Model Dev. 2018, 11, 2763–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.H.; Barros, A.P. Observing System Simulation of Snow Microwave Emissions Over Data Sparse Regions— Part I: Single Layer Physics. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2011, 50, 1785–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.H.; Barros, A.P. Observing System Simulation of Snow Microwave Emissions Over Data Sparse Regions—Part II: Multilayer Physics. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2011, 50, 1806–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartelt, P.; Lehning, M. A physical SNOWPACK model for the Swiss avalanche warning. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2002, 35, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, E.; Martin, Ε.; Simon, V.; Gendre, C.; Coleou, C. An Energy and Mass Model of Snow Cover Suitable for Operational Avalanche Forecasting. J. Glaciol. 1989, 35, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U. F., T. Microwave Remote Sensing. Active and Passive 1986, vol. 0, p. Chap. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V. P.; Singh, P.; Haritashya, U. K. Encyclopedia of Snow, Ice and Glaciers; Springer Science & Business Media, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.R.; Choudhury, B.J. Remote sensing of soil moisture content, over bare field at 1.4 GHz frequency. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 1981, 86, 5277–5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegmuller, U.; Matzler, C. Rough bare soil reflectivity model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 1999, 37, 1391–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, T.; Schmugge, T.J. A Parameterization of the Effect of Surface Roughness on Microwave Emission. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 1987, GE-25, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Li, Z.; Tse, K.K.; Tsang, L. Microwave model of remote sensing of snow based on dense media radiative transfer theory with numerical Maxwell model of 3D simulations (NMM3D). Proceedings. 2005 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 2005. IGARSS ’05, July 2005; pp. 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, M.C.; Ulaby, F.T.; Hallikainen, M.T.; El-Rayes, M.A. Microwave Dielectric Behavior of Wet Soil-Part II: Dielectric Mixing Models. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1985, 23, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallikainen, M.T.; Ulaby, F.T.; Dobson, M.C.; El-Rayes, M.A.; Wu, L.-K. Microwave Dielectric Behavior of Wet Soil-Part 1: Empirical Models and Experimental Observations. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 1985, GE-23, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhao, T.; Pan, J.; Xue, H.; Zhao, L.; Shi, J. Improvement in Modeling Soil Dielectric Properties During Freeze-Thaw Transitions. IEEE Geosci. Remote. Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.; Derksen, C.; Toose, P.; Langlois, A.; Larsen, C.; Lemmetyinen, J.; Marsh, P.; Montpetit, B.; Roy, A.; Rutter, N.; et al. The influence of snow microstructure on dual-frequency radar measurements in a tundra environment. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2018, 215, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmetyinen, J.; Derksen, C.; Rott, H.; Macelloni, G.; King, J.; Schneebeli, M.; Wiesmann, A.; Leppänen, L.; Kontu, A.; Pulliainen, J. Retrieval of Effective Correlation Length and Snow Water Equivalent from Radar and Passive Microwave Measurements. Remote. Sens. 2018, 10, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Tan, S.; Tsang, L.; Kang, D.; Kim, E. Snow Water Equivalent Retrieval Using Active and Passive Microwave Observations. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Durand, M.; Kim, E.; Barros, A.P. Bayesian physical–statistical retrieval of snow water equivalent and snow depth from X- and Ku-band synthetic aperture radar – demonstration using airborne SnowSAr in SnowEx'17. Cryosphere 2024, 18, 747–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, K.; Brucker, L.; Hiemstra, C.; Marshall, H.-P. “SnowEx17 Community Snow Pit Measurements, Version 1,” NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center (DAAC) data set, p. Q0310G1XULZS. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.; Marshall, H.-P.; McCormick, M.; Craaybeek, D.; Elder, K.; Vuyovich, C. “SnowEx20 Time Series Snow Pit Measurements, Version 1,” NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center (DAAC) data set, p. POT9E0FFUUD1; Jan 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Durand, M.T.; Jagt, B.J.V.; Liu, D. Application of a Markov Chain Monte Carlo algorithm for snow water equivalent retrieval from passive microwave measurements. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2017, 192, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montpetit, B.; Royer, A.; Wigneron, J.-P.; Chanzy, A.; Mialon, A. Evaluation of multi-frequency bare soil microwave reflectivity models. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2015, 162, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Durand, M.; Lemmetyinen, J.; Liu, D.; Shi, J. Snow water equivalent retrieved from X- and dual Ku-band scatterometer measurements at Sodankylä using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo method. Cryosphere 2024, 18, 1561–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metropolis, N.; Rosenbluth, A.W.; Rosenbluth, M.N.; Teller, A.H.; Teller, E. Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 1953, 21, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulaby, F.T.; Stiles, W.H. Microwave response of snow. Adv. Space Res. 1981, 1, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Barros, A.P. Weather-Dependent Nonlinear Microwave Behavior of Seasonal High-Elevation Snowpacks. Remote. Sens. 2020, 12, 3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, B.J.; Schmugge, T.J.; Chang, A.; Newton, R.W. Effect of surface roughness on the microwave emission from soils. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 1979, 84, 5699–5706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, P.; Barros, A.P. Multi-Physics Data Assimilation Framework for Remotely Sensed Snowpacks to Improve Water Prediction. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, P.; Barros, A.P. Assimilation of L-band interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) snow depth retrievals for improved snowpack quantification. Cryosphere 2025, 19, 2895–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NSIDC SAR data file naming convention | Flight name (used in the study) | Date | Time (GMT) | Band | Pol | ΔS (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20170221181138<F>G_<b>.nc | 181138 | 2017-02-21 | 18:11:38 | X, Ku | VV, HH | 1 |

| 20170221184320<F>G_<b>.nc | 184320 | 2017-02-21 | 18:43:20 | X, Ku | VV, HH | 1 |

| 20170221185902<F>G_<b>.nc | 185902 | 2017-02-21 | 18:59:02 | X, Ku | VV, HH | 1 |

| 20170221202338<F>G_<b>.nc | 202338 | 2017-02-21 | 20:23:38 | X, Ku | VV, HH | 1 |

| 20170221172126<F>G_<b>.nc | 172126 | 2017-02-21 | 17:21:26 | X, Ku | VV, HH | 1 |

| 20170221173206<F>G_<b>.nc | 173206 | 2017-02-21 | 17:32:06 | X, Ku | VV, HH | 1 |

| GRMST1_27401_20007_005_200211_09225VV_XX_01.tif | 005 | 2020-02-11 | 17:01:07 | X | VV | 1 |

| GRMST1_27702_20007_009_200211_09225VV_XX_01.tif | 009 | 2020-02-11 | 17:25:17 | X | VV | 1 |

| GRMST1_27503_20007_012_200211_09225VV_XX_01.tif | 012 | 2020-02-11 | 17:50:03 | X | VV | 1 |

| GRMST1_27502_20008_025_200212_09225VV_XX_01.tif | 025 | 2020-02-12 | 19:02:37 | X | VV | 1 |

| GRMST1_27021_20008_021_200212_09225VV_XX_01.tif | 021 | 2020-02-12 | 18:38:38 | X | VV | 1 |

| GRMST1_27403_20008_029_200212_09225VV_XX_01.tif | 029 | 2020-02-12 | 19:26:28 | X | VV | 1 |

| NSDIC Pit name | Pit Name (used in the study) | Latitude | Longitude | Date | Local Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28S | A1 | 39.0122478 | -108.1379938 | 2017-02-25 | 11:00 |

| 78N | A2 | 39.04342878 | -107.9202531 | 2017-02-25 | 15:10 |

| 92E | A3 | 39.0510518 | -107.885109 | 2017-02-22 | 10:00 |

| 92W | A4 | 39.0510159 | -107.8876494 | 2017-02-22 | 13:25 |

| KC1C | A5 | 39.01363394 | -108.1838735 | 2017-02-20 | 10:30 |

| MTR4_0000 | A6 | 39.0300503 | -108.0331353 | 2017-02-24 | 10:15 |

| MTR4_0800 | A7 | 39.03005659 | -108.0332395 | 2017-02-24 | 10:09 |

| MTR4_1390 | A8 | 39.03005509 | -108.0332972 | 2017-02-24 | 10:00 |

| MTR4_2000 | A9 | 39.03005329 | -108.0333664 | 2017-02-24 | 10:08 |

| MTR4_2500 | A10 | 39.03005179 | -108.0334241 | 2017-02-24 | 10:00 |

| KC1S* | A11 | 39.01344468 | -108.1838766 | 2017-02-20 | 12:45 |

| KC1N* | A12 | 39.01381389 | -108.1838816 | 2017-02-20 | 13:00 |

| 67N* | A13 | 39.03245119 | -108.0291492 | 2017-02-22 | 12:20 |

| KC1W* | A14 | 39.01362669 | -108.1841388 | 2017-02-20 | 13:46 |

| MTR4_4500* | A15 | 39.03005478 | -108.0336552 | 2017-02-24 | 10:00 |

| KC1E* | A16 | 39.01363219 | -108.1836079 | 2017-02-20 | 12:30 |

| 1S1 | B1 | 39.02119889 | -108.20559 | 2020-01-29 | 09:05 |

| 1S2 | B2 | 39.019948 | -108.203396 | 2020-02-08 | 09:37 |

| 2S3 | B3 | 39.021089 | -108.202889 | 2020-01-29 | 10:35 |

| 2S4 | B4 | 39.017951 | -108.201292 | 2020-02-05 | 09:30 |

| 2S7 | B5 | 39.01866002 | -108.197788 | 2020-02-08 | 11:35 |

| 3S5 | B6 | 39.01911256 | -108.1986242 | 2020-01-29 | 12:10 |

| Wëgmuller and Mätzler (1999) – WM99 | |||||||||

| f (GHz) | A0 | A2 | A3 | β | Bias | Std | |||

| WM99fi (All) | 0.039 | 0.872 | −0.016 | 2.140 | −0.002 | 0.058 | |||

| 10.65 | 0.080 | 0.935 | 0.302 | 1.890 | −0.012 | 0.052 | |||

| Wang and Chaudhary (1981) – QHN | |||||||||

| f (GHz) | a1 | a2 | a3 | Q | NV | NH | Bias | Std | |

| QHNfi (All) | 0.887 | 0.796 | 3.517 | 0.075 | 1.503 | 0.131 | −0.003 | 0.042 | |

| 10.65 | 0.880 | 0.838 | 3.280 | 0.657 | 3.209 | 0.178 | 0.012 | 0.047 | |

| Type | Structure | Total Backscatter | Ground Backscatter Component | BASE-AM observation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh snow | Low density (<200 kg/m3), small grains, fluffy, homogeneous. | Low | Weak volume scattering because grains are much smaller than the wavelength (Rayleigh regime) | High | Low density, tiny grains → weak volume; waves reach ground easily | Low observed SAR, overestimating volume, underestimating ground backscatter |

| Depth Hoar (Large Grains, Faceted Snow) | Coarse grains (1–3 mm), low density but with strong internal contrasts | High | X-band is very sensitive here because grain size approaches or exceeds the Rayleigh-to-Mie transition relative to wavelength. Stronger volume scattering than other dry types → higher backscatter. |

Low | Penetration OK, but strong volume scattering from large grains masks ground | High observed SAR, underestimating volume, overestimating ground backscatter |

| Wet Snow (Moisture in Pores, LWC > ~0.5%) | Presence of liquid water between grains, even in small fractions | Very low | Strong absorption and attenuation → backscatter drop sharply. Surface scattering dominates, but the wet snowpack looks darker overall (–15 to –25 dB). Even a thin wet layer on top masks deeper scattering. |

Very low | Liquid water strongly attenuates → ground largely invisible | Low observed SAR, overestimating volume, highly underestimating ground backscatter |

| Snow with Light Absorbing Particles (Dust, Soot, Organic Matter) | Like dry snow but with LAP inclusions | Low | LAPs change dielectric properties slightly and can increase absorption. | Low | LAPs raise absorption slightly → less penetration, hence less ground share | Low observed SAR, overestimating volume backscatter, underestimating ground backscatter |

| Icy or Crusted Snow | Ice lenses, melt-freeze crusts, hard refrozen surfaces. | Very high | Very strong surface scattering at X-band (specular if smooth, diffuse if rough). Appears bright regardless of underlying snow. |

Very low | Crust/ice lenses reflect at shallower depths → cut off penetration | Very high observed SAR, highly underestimating volume backscatter, highly overestimating ground backscatter |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).