1. Introduction

Projections show that by 2050, two-thirds of the world’s population will live in urban areas, creating a huge demand for reliable and sustainable urban water systems (UWS) [

1]. Coastal cities are growing rapidly and about 15% of global population living within a few miles of a coast due to economic hubs, job opportunities; trade, recreation, and access to nature [

1]. Such urbanization and demographic shifts, leading to increasing pressure on coastal environments, pollution, resources demand and a need for better planning, regarding vulnerability to climate change and especially regarding sea level rise, as well as lack of water, food and energy resources. To sustain livelihood there is a constant need for evolution of

relevant urban less-dissipative structures and capital structures to enhance adaptation, by integrated resource management (IRM), financing and long-term planning considering future conditions, and the impacts of climate change and resources depletion over decades or even centuries.

Croatia coastal area is not an exception in this regard, but rather an extreme example. Seasonal demand is increasing (energy and matter input), as is seasonal waste and related pollution (energy and matter output), so the imbalance between seasonal and off-season demand and waste loads is increasing, which creates additional dynamics of the system and stresses to the natural and urban environment and infrastructure that degrading over time. Summer tourism in Croatia is a major industry and economic sector largely concentrated on the coastal areas, and coastal inhabited islands along the Adriatic Sea. It has historically represented a large component the country’s economic output (GDP), routinely reaching 10% to 15% of total GDP [

2]. That why socio-physical and economic problems are becoming increasingly complex and difficult to solve, because external climatic pressures and internal socio-economic pressures are accelerating and adaptation is delayed, so the entire socio-economic system is increasingly vulnerable. The sea level rise, the rise of climate extreme and variability, and limited capacity of supply chains of water, food and energy are adaptation priorities. The suitable response to the current situation and trends of change is based on IRM framework with circular economy (CE) strategies fitting within IRM system and systemic urban climate adaptation.

Systemic urban climate adaptation is a holistic approach to making cities resilient to climate change by transforming interconnected urban systems (infrastructure, social, ecological, economic) simultaneously, rather than tackling isolated issues. It is cross-sectoral IRM approach to tackling climate change and resources depletion by integrating solutions across technology, governance, environment, and society, moving beyond siloed, reactive measures to build broad, anticipatory resilience. It recognizes climate impacts and resources depletion as interconnected challenges requiring unified, multi-level responses, focusing on long-term, integrated strategies like nature-based solutions, green spaces, resilient infrastructure, equitable development, CE and community involvement to create robust, system-wide preparedness and avoid maladaptation. Such approach ensures actions create positive feedback loops, maximize benefits, and avoid unintended negative consequences, which implies the application of circular urban systems (CUS).

CUSs are city models designed to eliminate waste, pollution, and resource depletion by keeping products, materials, energy, water and nutrients in use at their highest value for as long as possible, essentially closing material loops through reuse, repair, and recycling, all while regenerating natural systems and promoting sustainable living, powered by renewables and collaboration between citizens, businesses, and government. This strategy contrasts with the traditional linear “take-make-waste” model, creating resilient, regenerative urban environments. Goals and benefits include: reduction of all resource extraction, enhanced resilience, improved health and economic opportunities. Such concept implementing circular principles across all city functions, from energy and water to transport, and buildings by studying resource flows (matter and energy) in urban metabolism to identify opportunities for closing loops and improving efficiency. It includes development of sustainable infrastructure using renewable energy, and creating efficient integrated water management, i.e. circular urban water systems (CUWS).

CUWS is regenerative approaches that shift from the linear model to closed-loop systems, focusing on reusing and recovering resources (water, nutrients, energy) within cities to minimize waste, reduce reliance on fresh water, energy, nutrients and enhance urban resilience through technologies like rainwater harvesting, greywater recycling, and nature-based solutions (bioswales, green roofs), as well as treated wastewater reuse (water recycling) by advanced treatment, (sludge) nutrients recovery and green energy (biogas) recovery via anaerobic digestion. Such systems integrate CE of water system, wastewater and stormwater systems to create healthier environments, boost local economies, and build sustainable, climate-ready cities by integrating water management with urban design and river basin sustainable development.

The sustainable development measurement model is established based on dissipative structure theory. Cities (CUS) as dissipative structure are an self-organizing system that maintain internal ordered through constant exchange of energy and matter with surroundings existing in a state of thermodynamic non-equilibrium. The same goes for CUWS. To function as dissipative structures, they must be open systems that exchange energy, matter, and information with their environment, urban and natural. This involves both physical constraints and the social ability to modify the environment, leading to more complex, self-sustaining structures like those seen in biological and social systems. Examples include the development of ecosystems, urban environments, less-dissipative supply chains of water, food and energy and ability to adapt to both internal and external change.

An urban water system can be understood as a dissipative structure because it maintains order and complexity through a continuous flow of energy and water, exporting entropy to its environment. This system is open and far from thermodynamic equilibrium, with human activities like cooking, bathing, and irrigation (social dissipation) and natural processes like evapotranspiration from surfaces and buildings (physical dissipation) driving the conversion of liquid water to water vapor, which is then exported to the atmosphere together with heat. Such urban system maintains its internal order and complexity by importing energy, food and materials from environment and exporting waste and heat. In such environment the socio-physical dissipative adaptation of the urban and tourism economical systems to both, internal extreme seasonality demand and external constant climate change pressures becomes a more complex and demanding task. For example, building a complex structure (accommodation, catering, and attractions, as well as organizational structures require a large energy, water and food input, which is eventually dissipated as heat and waste. That why concept of a city as a dissipative structure raises crucial questions about sustainability. It reduces the vulnerability of CUS and CUWS it is necessary to implement/realize socio-physical dissipative adaptation.

The solution offered is based on planning and adapting of UWS as less-dissipative structure through CE strategy that offers an opportunity to tackle the water, food and energy challenges by providing a systemic and transformative approach to delivering water supply, sanitation services and urban flood protection in a more sustainable, efficient, and resilient manner, supporting urban water, food and energy system sustainability. A CE approach is a response to the current unsustainable linear model of “take, make, consume, and waste,” that is natural resources manning, thereby reducing pressure on natural resources and minimizing waste. A new World Bank report titled

Water in Circular Economy and Resilience (WICER), aims to establish a common understanding of circular economy and resilience in the urban water sector [

3].

To verify this, it is necessary to apply integrated climate vulnerability assessments (IVAs) [

4]. It is systematic processes that evaluate how climate change impacts a system by analyzing its exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity across multiple sectors and scales. They are used to inform climate adaptation strategies by identifying what human security issues (like food, water, health) are most affected and by whom, then developing and improving responses. IVAs often combine “top down” quantitative data (like climate models) with “bottom-up” qualitative data from local knowledge and participatory tools. The assessment approach in this paper is mainly based on local knowledge and participatory tools, while the sustainability of CUWS is assessed based on circular thermodynamics. A bottom-up approach allows for easier analysis of smaller systems with the aim of their integration into more complex IRM systems CUWS, and then into CUS, thus making the water, wastewater and stormwater of the emergent circular system. The circular thermodynamics was developed to assess the sustainability of organisms and systems. It refers to applying thermodynamic principles to cyclical processes, especially in living organisms or sustainable systems aiming for closed loops, focusing on energy/matter flow, minimum entropy production (like in living things), and efficient resource use, contrasting with linear models.

CUWS as integrated component of CUS in tourist coastal areas are topic of this paper. Systemic urban climate adaptation and circular urban systems are intertwined strategies for resilient cities, focusing on closing resource loops (circularity) while building resilience to climate impacts (adaptation) through integrated, whole-system approaches, like reusing water, biogas and nutrient recovery, designing regenerative buildings, and creating green infrastructure, to reduce emissions, boost sustainability, and ensure equity. These systemic methods move beyond single solutions, connecting urban planning, energy, water, waste, and social factors to transform cities into adaptable, low-carbon, and resource-efficient environment.

2. Material and Method

2.1. Methodology

The concept that is explored in this paper use dissipative structures theory to analyze the complexity and sustainability of UWS and urban systems (US). Dissipative structures (DS) are organized systems that maintain themselves by dissipating energy, water and matter, and are maintained by non-equilibrium processes, with examples including human society, cities, and UWS. In the paper this framework is used to critique and enhance the circular economy’s feasibility, arguing that it may face limitations due to the fundamental entropic nature of urban and UWS processes and the need for continuous energy and material input to be sustainable.

The paper analyzes sustainable circulation processes and their components necessary for IRM in coastal tourist areas that strengthening the sustainability of the water, food and energy circulation processes in the urban system and environment, as well as their interactions that strengthen the sustainability of the urban environment. For example, water storage as dynamic open system that maintains its organized form by constantly exchanging energy and water with its surroundings and dissipating the excess energy and water to remain stable far from equilibrium is typical dissipative structures in city water systems. Such system relies on a continuous flow of energy and water rather than a stored reserve (static stock for future use). Therefore, the urban water system in a circular economy is a socio-physical dissipative structure that strengthens the resilience of the urban system, and must be treated as such in the concept of a CE. That apply principles found in less-dissipative structures (LDS), aiming to build human system that behave more like resistant, self-sustainable natural ecosystem.

The sustainability of CUWS is assessed by circular thermodynamics [

5]. The CUWS and CUS as open dissipative systems use and store energy and water in a design / planned efficient way, while maintaining its organization and functions, a stable internal environment despite changing in external conditions, urban and natural (climate). However, the internal state is not static but is kept in a stable range through constant adjustments to external and internal changes. Mechanisms like circulation (negative feedback loops) help the system detect and correct deviations from its stable state. Cycles provides dynamic stability and autonomy to the system, which is autonomous adaptation capacity to reduce system sensitivity and vulnerability. With such capability the yielding processes can transfer energy and water directly to those requiring it. This is proposed to be achieved by integrating related circular water dissipative structures (infrastructure) in an IRM system to coordinate various resources for sustainable outcomes.

The significant space-time differentiation of the coastal urban systems is directly proportional to its resources (water, food, energy) storage capacity or resources residence time. Therefore, any change in demand or supply creates an imbalance and threatens the stability and sustainability of the urban system and economy. In this state of balance, the system organization is maintained and dissipation minimized; i.e. the entropy exported to the surroundings and what could be another circulatory system. This implies that waste from one cycle is a possible resource for another cycle.

Input-output thermodynamics provides a framework to track energy and matter transformations, ensuring that what goes in must come out in some form, even if it’s less useful than intended. It provides the accounting framework (mass/energy balances) to analyze how physical systems like (DS) that transform inputs into desired outputs, respecting fundamental conservation laws; Input energy isn’t lost but changes form; energy in = energy out + energy stored. This also applies to matter/water. The total matter in a system stay constant; what comes in must either leave or accumulate.

Second Law state that efficiency of the system (entropy) is: Useful Output Energy (matter) / Total Input Energy (matter). Second Law implies; no process is 100% efficient; some energy always disperses as unusable heat, increasing entropy (disorder). The Second Law of Thermodynamics helps explain the direction and rate of energy and matter flow and thus determine the state of the system sustainability. Entropy of an open system (dS) will change with interchanges of energy and matter with the environment (deS - external entropy) and with entropy increasing in the system itself (diS - internal entropy), as result of inner irresistible processes (diS >0): dS = deS + diS.

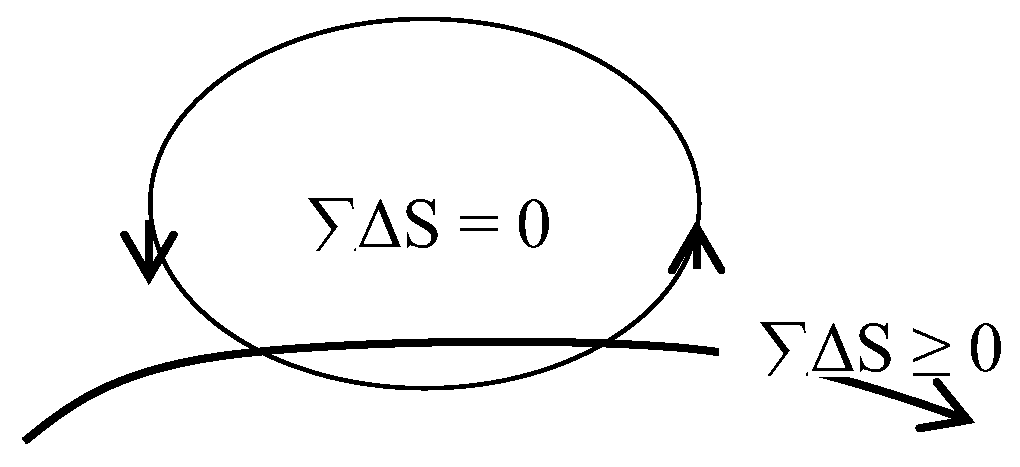

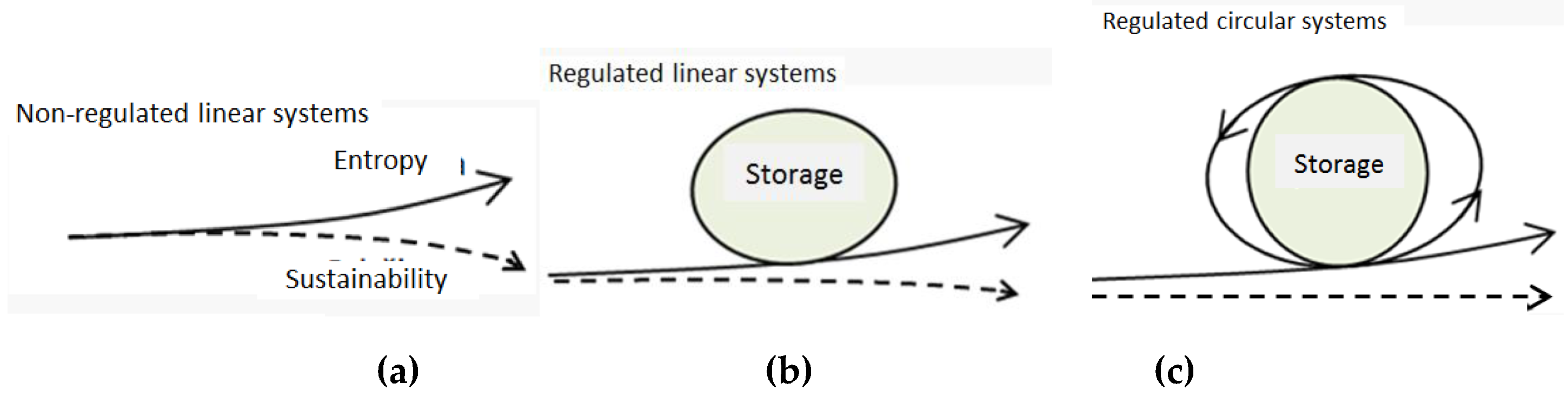

Process of energy and matter exchange with the environment can be either positive or negative. Thus, the entropy of an open system decreases at expense of the fact that associated processes produce positive entropy in the other parts of the environment (other systems) since internal entropy change is positive d

iS > 0. So, sustainable system approaches an ideal dynamic balance of zero-entropy production (

Figure 1).

The simple equation ∑ΔS = 0 inside the cycle, says there is an overall conservation of energy and matter, and compensation of entropy so that the system organization is maintained and dissipation reduce to zero-while the necessary dissipation exported to outside, is also minimized, ∑ΔS ≥ 0. Internal entropy compensation and energy and matter conservation implies that positive entropy generated somewhere is compensated by negative entropy (or decrease in entropy) elsewhere within the system over finite time.

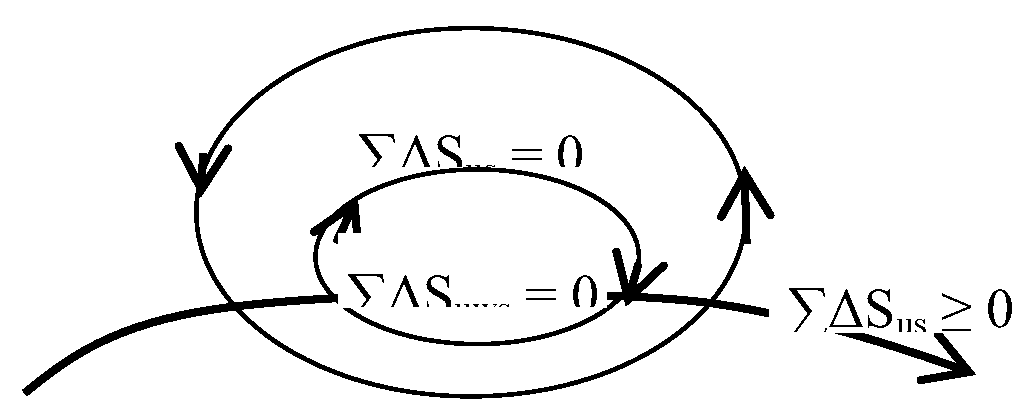

Cycles allow UWS activities to be connected and interconnected so that the resources generated can be transferred between urban water system, as well as other urban systems (solid waste, energy) which strengthen their and urban society and economy sustainability and stability. Symmetrical coupling of processes, more or less strong, can be adapted in a system under energy and matter flow, often results in stable, predictable, or uniform behavior of the system that is less-dissipative system that minimizes loss of matter, water and energy. Adapted cycles span in relevant space-time scales, the totality of which make up the CUWS within CUS. Each smaller cycle have to be look-like as a whole. This model of integration within CUWS is generated by the repetition of unique rules that reveal intricate structures hidden within a seemingly disconnected UWS system. Coupled forms of systems and cycles are created by IRM framework to support sustainable growth and development (

Figure 2). These are CE strategies built into the IRM system for better efficiency.

Sustainable UWS maximizes non-dissipative cyclic flows of energy and matter and minimizing dissipative flows. Maximizing non-dissipative cyclic flow will increase the following energy and matter storage capacity, which translates into carrying capacity; the number of cycles in the system; the efficiency of resources and energy use; space-time differentiation, which translates into sustainability; balanced flow of resources and energy; reciprocal coupling processes. The minimization of dissipation will result in reducing entropy production. The energy and matter output/input ratio gives a good indication of sustainability and system efficiency.

Matter in UWS includes essential components like clean water and nutrients (N, P), but also diverse pollutants (heavy metals, organics, pathogens, pharmaceuticals) from residential, industrial, and stormwater sources, all cycling through complex water infrastructure, circular systems and interconnected natural systems (coastal river basin). Cycles give dynamic stability and autonomy to the urban systems. This applies in social system, which is also an open system that exchanges energy, water and matter with the environment. So, when societies lack water, food, energy, or effective governance, they tend toward disorder/chaos, i.e., societal entropy increase. That why the entropy method serves as an indicator for objectively assessing sustainability of coastal nature, society and economy. The adaptive technologies neutralize (entropic) perturbations; strengthen output from original change process reducing or eliminated change that brings the system back to equilibrium. Therefore, in human society, socio-physical dissipative systems (CUWS, CUS) have the function of ensuring the livelihood sustainability.

In coastal areas of Croatia the dominant linear input-output system grows relentlessly, swallowing up the earth’s resources, laying waste to everything in its path. There are no closed cycles to hold resources within, to build up stable organized social or ecological structures. That’s the essence of our seasonal tourist boom and bust economy. The zero entropy CE, on the other hand, is embedded within and integrated with the circular economy of the biogeophysical environment. It builds up space-time structures within to store and mobilize renewable energy and matter through values added in various ways to the primary productivity from sunlight and photosynthesis, secondary productivity (primary consumers) and tertiary productivity (higher consumer productivity). To achieve sustainable outcome, the most efficient integration of natural biogeophysical and urban environment, and urban socio-physical dissipative structures by IRM is necessary; which defines circular dissipative systems adaptation. In coastal cities, the sea and the coast are key socio-economic resources whose preservation of health largely determines the sustainability of the local community. In essence, circular dissipative systems adaptation describes how life and complex structures arise and persist by continuously processing energy, water and matter and finding optimal ways to minimize entropy production. The US to sustain their functions has to create stable circular patterns and optimize function by balancing energy, water and matter input with dissipative losses.

2.2. Urban Water System Resource Recovery Potential

2.2.1. Urban Water System

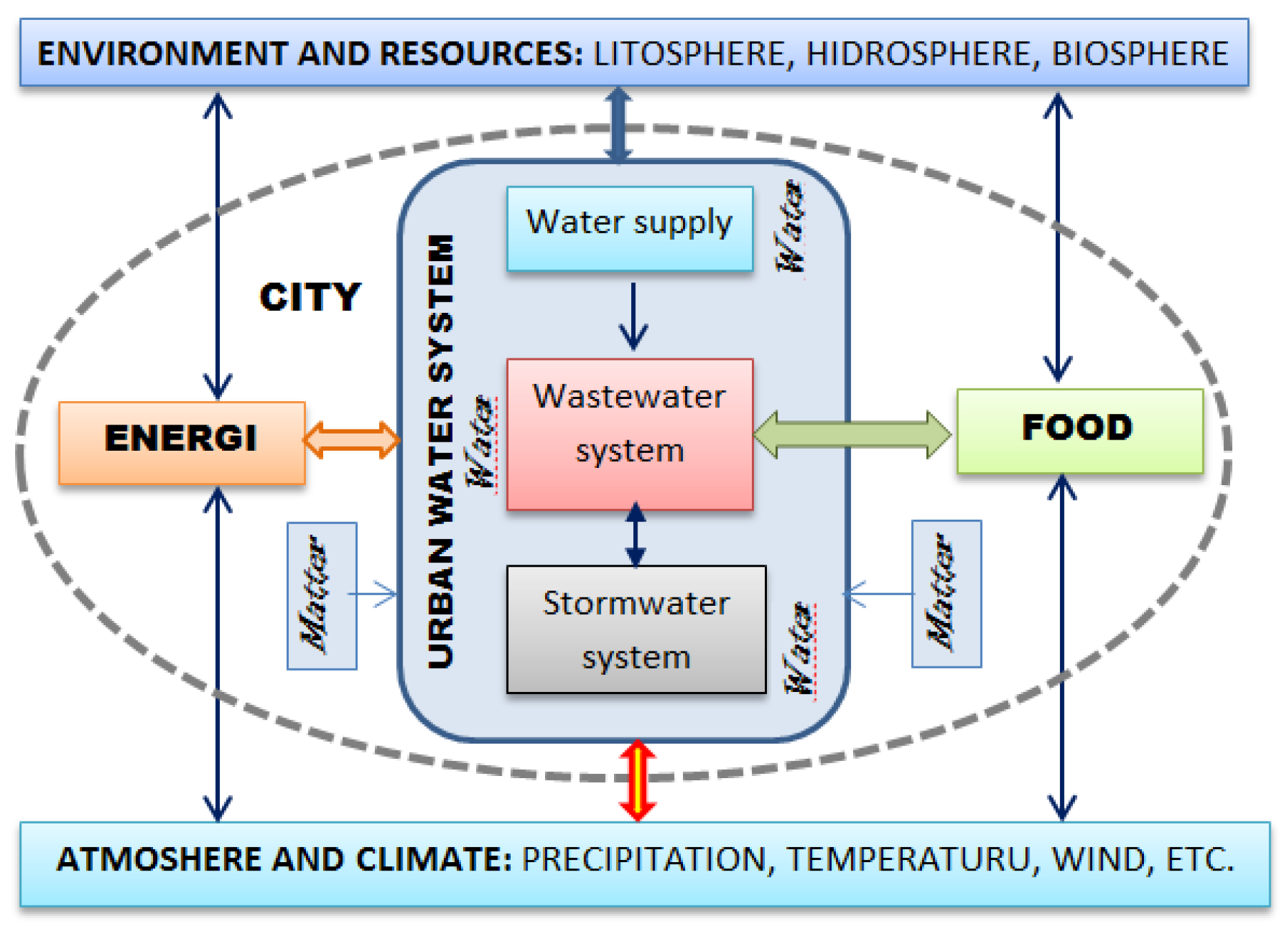

UWS main parts are: water supply, wastewater management, and stormwater control (

Figure 3). These units are hierarchically organized by the movement of energy, water and other matter through the UWS and are interconnected into a unique urban water cycle that is cross-border connected to the city’s water resources system through its input and output structures and processes [

6].

The function of a water supply system is to supply people and the city with safe, potable water at adequate pressure. The water supply system can be analyzed as a dissipative structure because they are open complex ones far-from equilibrium systems that self-organize by network layout, treatment processes and distribution patterns, maintaining order through continuous energy and water exchange (input) to prevent stagnation and maintain flow. System produces entropy resulting from energy transformation (friction, pumping) and water losses, moving towards self-organized sustainability or potential collapse if fail to adapt to internal (demand shift) and external (climate) pressures.

Urban wastewater systems collect and transport wastewater (domestic, industrial) via sewer networks (sanitary) to treatment plants, which remove pollutants before safe discharge or reuse, protecting health and environment [

7]. This system functioning as complex, open system (like “urban metabolism”) constantly exchange energy and matter, exhibiting characteristics of dissipative structures. Such system constantly processing and transforming waste by anaerobic and aerobic processes within network and at treatment plant into different forms (treated water, sludge, energy, and nutrients) while moving away from chaotic states towards new, ordered if possible sustainable forms. To be far from equilibrium they require continuous energy and material input (electricity, chemicals) and constant management to maintain function and prevent system collapse resulting with pollution of urban area, water resources and sea, overflowing sewers and other negative consequences to humans and environment. As and open system they constantly take wastewater (matter/energy), produce outputs that need management, and release treated effluent, sludge, heat and methane, recycling nutrients and energy recovery. Without appropriate input (management fails) the system rapidly shifts to chaotic states (pollution, flooding).

The water supply system and the sewage system are hierarchically organized. Raw water is treated to meet drinking water standards. After use, drinking water becomes wastewater that flows into the wastewater sewers and with it to the wastewater treatment plant where it is purified and then released into water resources. In classical linear systems, this is a constant, but time-varying, one-way water flow from water resources to the city and back from the city to the water resources. The flow of water within the system is in function of the regime/dynamics of water consumption in the city. The balance, water flow and quality of water, as well as the pressure of water in the system, are controlled and managed. In water supply systems service reservoirs are crucial water storage facilities, usually storing treated drinking water near consumers to balance supply-demand flows, to maintain system pressure, and to provide emergency reserves for firefighting or failures, acting as balancing tanks.

Energy is necessary to transport water from the water intake to the users and back to the water resources, as well as to treat water and wastewater. It is mostly done via pumping stations and by gravity. The differences in system elevation and the distances between the water intake and the water users, wastewater treatment plant and recipient are large, and today electrical energy is necessary for the system to operate. Due to the large surface and the topographic diversity of modern urban areas and buildings, modern urban water systems are predominately water pressure systems. This is why water supply and wastewater treatment are highly energy-intensive. Energy costs are a huge part of operational budgets depending of topography of the system (33-80% of non-labor costs). Without electric energy, modern systems cannot function and are not operationally sustainable.

Classic stormwater sewerage also has a one-way water flow. The input to the system is rain over city surface and the associated marginal catchment area from which the water flows downhill into and though the city area. Stormwater drainage system act as dissipative structure by converting excess water energy (kinetic and potential) into turbulence, heat, and sound, what preventing erosion and reduce risk of downstream flooding and support order. System components (manholes, cascades) brake down high-energy flow into turbulent, lower-energy flows, reducing water velocity and power. By converting order energy (flowing water) into disordered forms (heat, turbulence), they increase local entropy, allowing the system to stay organized and manage water without failing. In essence, system scatters destructive energy, allowing the urban environment to function better under stress from rainfall. The runoff process is intermittent (stochastic) and largely uncontrolled, and is determined by the intensity of precipitation, the catchment area characteristics, and the gravitational potential energy of the drainage system. Therefore, it is very susceptible to the impact of climate change that alters precipitation regime. To manage flow it is often necessary to build retention basins and pumping stations. Stormwater system also has a treatment plant for purifying the collected water [

7]. Since water flow only during rainfall system is not significant consumer of electric energy.

The urban water drainage system can be combined, separated or semi-separated type. In a combined system one pipe carries both sewage (foul water) and stormwater runoff, simpler but prone to overflows during heavy rain since wastewater and stormwater are drained through the same channels. These are old systems that are simple and cheap to build if wastewater discharge is not treated. Otherwise, due to the variable water flow and water composition, construction and treatment costs are high and complex to operate. Such systems are often found in the historical urban centers. The system is not very suitable for resource recovery primarily due to the changing water and quality of water regime (dry, rainy) and the treatment cost. The system is sensitive and vulnerable to climate change, and adaptation measures are more complex and are therefore no longer being built [

8].

Separate systems consist of two distinct pipe networks; one for wastewater (foul) and another for stormwater, preventing combined sewage overflows and pollution of the water resources. They are suitable for resource recovery. This system has sub-variants through the implementation of semi-separate (partially separate) systems of varying complexity which affects the possible recovery of resources and climate adaptation. Such systems blend separate and combined sewers collecting most indoor wastewater and some stormwater (roofs gutter) in one pipe to treatment plant. Large stormwater flow separate drains. This is a suitable and practical system for sparsely populated areas. In another type of semi-separated system, the first most polluted stormwater is drained together with wastewater system to a wastewater treatment plant to prevent pollution discharge in environment. This system is suitable for densely populated areas but less for resource recovery due to stormwater diverse quality and toxic substances (heavy metals). The presence of a particular type of sewage system in an urban environment significantly determines the urban water regime and thus the quality and availability of resources, which affects the implementation of the circular systems. In order to better protect the environment and create the conditions for the implementation of circular concepts of resource recovery, and to strengthen adaptation to climate change, the EU Waste Water Directive has stipulated that all sewage systems must be separate. For this reason, all combined systems are gradually being transformed into separate systems.

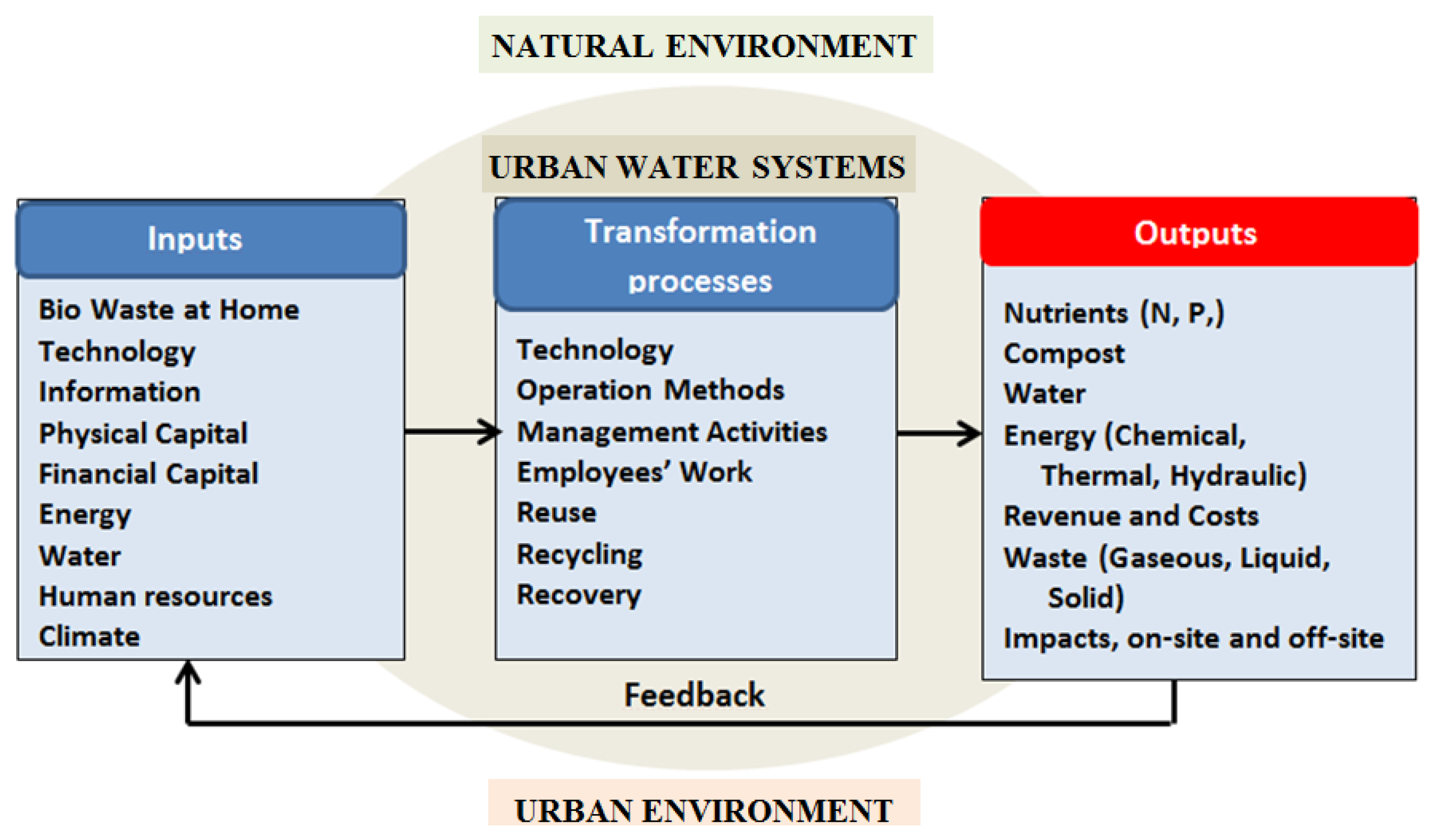

UWS is a typical example of an input-output system (

Figure 4) [

9]. It is an open system in which low-entropy resources are transformed through movement and use in urban metabolism into polluted high-entropy resources that negatively impact the environment and people. Entropy growth increases with the movement of water from the inlet to the outlet. By recovering resources and reusing water, the growth of the system’s entropy is reduced, which strengthens the sustainability of the urban water system, the city, and the natural environment. Otherwise, the UWS has the function of strengthening security and reducing the disorder that humans create in the environment through their living.

2.2.2. Urban Water System Resources

The main resources of UWS are water, nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus), chemical energy, thermal energy, hydraulic energy, and various substances depending on the composition of wastewater and stormwater. Mater in UWSs includes essential goods like clean water and energy, but also diverse pollutants (pathogens, organics, heavy metals, pharmaceuticals, suspended solids, trash and others) from residential/commercial, industrial, stormwater runoff and mobile sources, alongside nutrients (N, P) and emerging contaminants (gasoline additives, microplastics, PFAS), all flowing and cycling through urban water infrastructures (pipes, channels, treatment plants, pump station, retention basins) and associated natural system, and affect resource recovery potential. The quantity and composition vary over time and space, and depend on the characteristics of the climate, the city, and the activities that take place in the city, around the city, and within the UWS. Activities and life processes in cities, that is, the use of resources, have changed throughout history, from basic vital (water, food, energy) to increasingly complex ones created by industrial development and the application of new materials, technologies and energy. This changed the composition and quantities of wastewater and stormwater, as well as their recovery [

10].

The problem being addressed is not new; it has arisen and been solved throughout human history, in all civilizations and settlements. The recovery and reuse of resources in rural, predominantly agricultural environments, that mainly use natural energy and matter (solar society), generating organic waste resulting from life and working processes, has always been practiced, and is an integral part of the rural culture of living and working [

11]. Organic waste from the household is integrated with organic waste from domestic animal breeding and farming for joint processing and use. Everything that has been produced and used once again returns to the cycle of use in the household, animal husbandry, vegetable growing, fruit growing or farming. Different forms, dissipative processes and technologies of wastewater and organic matter recycling were applied depending on the characteristics of the climate and needs. Very little organic and other waste was thrown away. This strengthened the sustainability of the household and the farm [

11]. The external supply of energy, water and food has been minimized, and what is the vision of sustainable urban systems.

With the increase of people concentration with different professions, the traditional practice of local individual resource recovery is becoming increasingly difficult to implement, and is gradually becoming an urban service activity organized at the city level. Services of water supply, collection and removal of wastewater and products of life are charged, as well as the sale of processed and usable resources. In modern times, since 1900, increasingly large cities have been created that consume greater amounts of energy, water, food, and other resources, which creates ever-increasing amounts of wastewater and pollution of soil, air, and water that reduce resource availability [

12]. Because of this, there are fewer and fewer locally available good quality resources, which leads to the development of municipal infrastructure and services that take care of water supply, health standard, city cleanliness, and the treatment and disposal of all waste generated in the city (solid, liquid, and gaseous). Resource recovery was gradually introduced. Before the 20th century, the number of inhabitants in cities was not large, and the means of subsistence were generally sufficient, so there was no great interest or need for the recovery of resources from the urban water system. In recent times, the situation has been changing rapidly because needs are increasing and available resources are decreasing and are located further away, while environmental pollution is increasing [

12]. The constant daily needs for livelihoods in large cities are high (water 150 l/inhabitant/day, energy 12 kW/inhabitant/day, food 1.85 kg/inhabitant/day), supply chains are increasingly complex, and the availability of natural resources is decreasing and becoming more remote, so that the risk of survival in urban areas is increasingly threatened.

At the same time, climate change, as an external pressure, increasingly affects the availability of vital resources, urban infrastructure and safety of living and operation of UWS. Extreme weather events (temperatures, floods, storms) create an imbalance and disorder in the environment and urban areas, which creates increasing problems in controlling input-output processes in the environment, urban area and infrastructure. This is especially evident in areas with a seasonal tourist economy, which internally reinforces the imbalance through increased seasonal demand. That is why these urban environments and dissipative structures are particularly exposed to climatic and economic pressures that significantly reduce their resilience and sustainability. The application IRM framework and of the circular economy strategy is therefore becoming more and more important. It is necessary to organize the recovery of available resources in a controlled and proper manner in order to prevent health and safety problems that would threaten livelihood in cities and society in general. A prerequisite is a good knowledge of the availability and characteristics of the resources generated by UWS. These are resources that are constantly at hand in the urban environment itself, ready for recovery with appropriate processing and treatment [

13,

14,

15]. They are not directly dependent on supply chains and other supply issues, and are therefore reliable in all situations. In order to strengthen sustainability, it is very important to solve the problem systematically and comprehensively, involving all stakeholders by implementing IRM a broader philosophy. It is important to be aware that every application of technology results in an increase in entropy. Technologies based on natural processes and energy is more open and comprehensive, exchanging energy and matter with the environment, thus slowing down the increase in entropy [

11]. The problem is complex and demanding and needs to be maximally adapted to local conditions that ensure effective circulation of vital resources.

3. Urban Water System Resources Recovery Concepts

3.1. Storm Drainage System

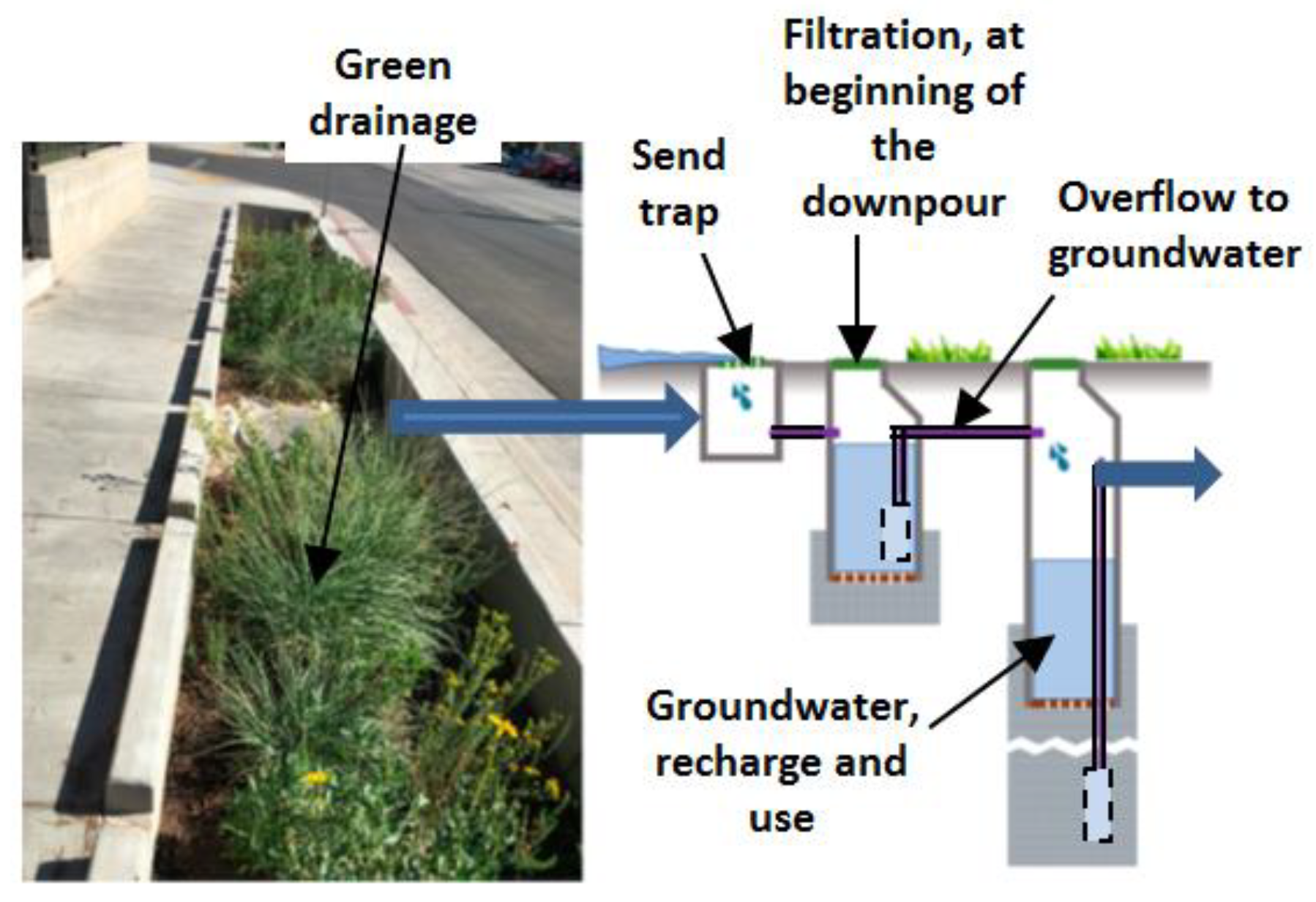

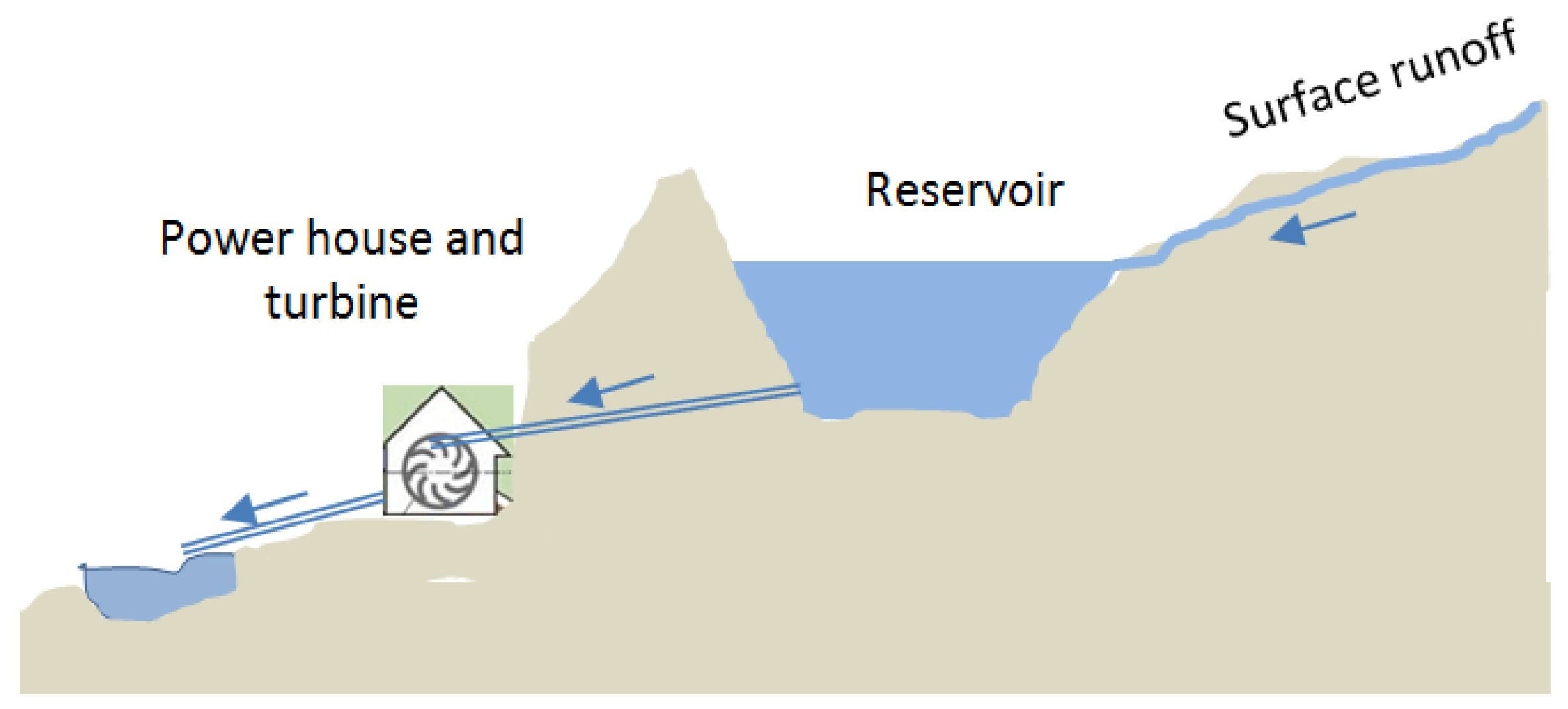

Urban surface runoff washes away impurities from the city’s surface, leaving the waters contaminated with various substances (trash, oils, and heavy metals, sediments from landscape, roads, and roofs). Pollution load is highest at the very beginning of runoff and decreases significantly over time, which affects the application of water reuse schemes. Runoff is a flood threat to people, property, and the functioning of the city. The unpredictable input of rain and pollution produces an unpredictable output, so runoff and pollution are attempted to be regulated by implementing retention and reservoirs, as well as sediment and oil traps. Retained water is a potential water resource for various purposes (process water, fire protection, cooling, irrigation, etc.), and even for water supply (Singapore) (

Figure 5) [

14]. Simplified, the value of this water is a function of the magnitude of droughts in the considered area. In addition, retained/stored water is a possible source of hydropower which can be integrated with water use schemes (

Figure 6). The potential depends on the gravitational potential energy of the reservoir.

Stormwater has been used for a long time in many countries, developed (USA, Australia, etc.) and especially less developed (India, etc.). The biggest obstacle to wider use is the lack of a regulatory framework, variability of inflow quantity and quality, and uncertainty in water treatment efficiency which will increase due to climate change.

To address problem urban planners and engineers adapted Water Sensitive Urban Design (WSUD). WSUD integrates stormwater infrastructure into the urban environment using green solutions (detention basins, constructed wetlands, rain gardens, and permeable pavements, green roofs),

Figure 5. These natural-based solutions slow water flow, reduce runoff peak, capture water matter, reduce energy/velocity of water, by infiltration, evaporation, transpiration, storage and filtered water by ground flow and vegetation. Therefore, controlled infiltration of rainwater into groundwater, evapotranspiration of water in atmosphere, capturing and storing rainwater in the settlement, as well as environmental water from areas above the settlement, which otherwise threaten the settlement, is an acceptable solution [

7,

14]. These also contribute to biodiversity enhancement and urban cooling, CO

2 capture, oxygen concentration increase and air quality enhancement, and overall landscape amenity of urban space. Integral solutions for stormwater protection and use are a promising concept that is increasingly being applied in many settlements. This especially applies to settlements that have combined drainage systems (stormwater and wastewater), because keeping stormwater outside the combined drainage system prevents and reduce uncontrolled overflow of polluted water into sea and water resources.

The biggest management problem is the stochastic characteristics of the generation of quantities, water quality and duration of runoff, and the large seasonal differences between rainy winter and dry summer runoff. Seasonal water storages are a suitable solution if they can be realized. They reduce peak runoff, erosion processes and provide water for various purposes during dry season. Water is trapped under water flow as occurs in natural hydrological systems to maintain water flow and reduce entropy. Water storage is a key element in the sustainability and cost-effectiveness of stormwater use. The increase in climatic variability of precipitation will make stormwater management more difficult and will require an increasing retention capacity of both artificial and natural retention basins. The application of green/blue solutions reduces the growth of the system’s entropy because it integrates it with environmental processes. Grey/building structures are not self-adaptive to environmental pressures and, unlike green ones, cannot adapt to climate changes without human intervention, and have a limited lifespan and capacity. Green solutions significantly contribute to increasing the quality of a tourist destination and its competitiveness.

3.2. Wastewater System

Wastewater consists of 99% water, and the remaining 1% contaminates complex mix; organic matter, (fats, food scraps, human waste), nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus), pathogens (bacteria, viruses), inorganic solids (send, metals), and chemicals (soaps, detergents, pharmaceuticals, pesticides) from homes, industries. Wastewater should be purified before discharge or use. For this, several treatment stages are applied that rely on a combination of physical, chemical and biological processes that provide an effluent quality that meets the standards, that is, “fit for purpose” treatment is applied [

10]. A large number of technologies can be applied, so selecting the best appropriate combination is a difficult task [

15,

16]. Wastewater treatment produces three main outputs: treated water (effluent) safe for discharge or reuse, sewage sludge (biosolids) used for fertilizer or energy, and biogas (methane) from anaerobic digestion, which can generate energy, alongside other byproducts like heat, nutrients, and greenhouse gases, all crucial for resource recovery and environmental protection.

Municipal wastewater as a resource has been used for a long time, so the advantages and disadvantages are well known [

16]. The largest and most traditional application is the use of treated water for irrigation. Biogas is the most important renewable energy source that has long been obtained from municipal wastewater treatment plants. The organic matter from the sludge is converted into a gas containing more than 60% methane by an anaerobic process. It follows that about 1.5 kWh/m

3 can be obtained from raw wastewater if COD is between 250 and 1000 mg COD/l [

16]. The produced gas can be easily stored, transported and used as needed to produce heat and power. Thermal energy from wastewater is used significantly less. The temperature of wastewater in the drainage system is between 10 and 25

0C. Thermal energy in the form of heat can be recovered from wastewater using various technologies (heat exchanger, heat pump) that are simple, proven and environmentally friendly. Thermal energy can be used for direct heating/cooling of homes, agricultural greenhouses, etc. Thermal energy could provide about 5.8 kWh/m

3 of wastewater for a 5

0C drop in wastewater temperature. In the context of the growing energy crisis, this form of wastewater recovery is becoming increasingly cost-effective at the local level. In addition, methane combustion significantly reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

Wastewater can also contain hydraulic potential energy in the form of the height difference in the system, that is, the pressure between the inlet and outlet, and the velocity head (kinetic energy). Due to the characteristics of wastewater and the fact that the system is gravity rather than pressure-driven, its use is limited to very special situations, such as (membrane energy recovery, or in cases where the drainage system is lowered deep beneath the city for easier transport, what generates geopotential energy (Chicago, Singapore and other big cities) [

17].

Citizens and other stakeholders do not have the same view on wastewater recovery. When choosing a concept, the following topics are considered: (i) Economics and value chain: Processing costs, resource quantity, resource quality, market value and competitiveness, use and application, distribution and transport; (ii) Environment and health: Emissions, health risks; (iii) Society and politics: Acceptance and support, policy and regulations. In environments where there is a periodic or permanent shortage of water, food and energy, recycling has no alternative. The recovery and reuse of purified wastewater has a significant impact on reducing the entropy of the city and the environment, and therefore it is used more and more in tourist areas.

Water consumption (water supply system) directly affects wastewater recovery capacity. Tourist uses more water and produces more waste than typical resident which significantly increases peak demand and pressure on the sewerage system and environment. This applies to energy and sludge (nutrient) production and recovery capacity determined by number of population equivalent (PE), in tourist areas also called Floating Population, who use the sewage system. Pollution (BOD) load of tourist is 20-40% higher than standard resident value for PE in EU (60 g BOD/day) (5-day BOD) [

8]. A similar situation occurs with water consumption, which increases significantly with the standard of the hotel/accommodation category. That is why resource recovery is higher than in other cities, and thus profitability.

The reuse of treated wastewater reduces strain on freshwater resources and enhances sustainability, create a stable, alternative water supply, therefore reduce seasonal water and energy peak demand in tourist areas and thus alleviate the stress (mess) in supply chain created by seasonal tourism in the coastal environment, as well as seasonal cost of water. Such a system can significantly strengthen the sustainability and increase reliability of tourism activities, especially in regions with insufficient freshwater capacity, caused by climate change (droughts, altered rainfall), overuse (irrigation, industry), pollution (agricultural runoff, wastewater), and poor management.

3.3. Water Supply System

A water supply system ensures access to clean water for health, food security, and economic growth. Water supply systems are energy-intensive systems in which significant amounts of energy are burns and lost as a result of the high variability of water flow during the day and throughout the year within a fixed system configuration. Water is needed most when local coastal water resources are at their lowest capacity. This creates pressures, causes losses of water and energy, which increases entropy and reduces the sustainability of the system.

The water supply system recovery refers mostly to energy recovery. Recovery can be practiced in advance where water transport conditions allow it, and as a measure to manage water losses in the system that occurs due to water consumption variability in the supply area which results with pressure variability in the water supply network. Therefore, in the water supply system, due to excess water pressure, in periods of low water consumption, and height differences within the water pipe system, there could be significant hydropower potential for electricity production. Excess water pressure energy is traditionally eliminated by pressure control valves and shut-off chambers that increase energy losses and thus system entropy. Instead of eliminating it, excess pressure can be utilized by installing micro hydropower systems that do not interfere with the functioning of the water supply system. Various solutions are being applied that reduce water pressure, produce green energy and at the same time contribute to reducing energy loss, greenhouse gas emissions and water losses in the system, which are a function of the pressure level [

18]. As an internal source of energy, it contributes to the security of water supply. Namely, high pressure regularly occurs every day during times of low water consumption, mainly at night. This is also brought to tourist areas where high pressure in water supply pipelines occurs throughout the entire off-season period of the year, 6 - 8 months. It is obvious that these are large potential capacities. That is why the profitability of energy utilization is viewed more broadly, taking into account all effects, not just economic and technological ones.

Water supply reservoirs can be adapted to serve as storage for hydro energy production by an urban pump-storage-hydroelectric plant that is integrated with green energy sources; solar, wind, chemical to reduce their intermittent production and adapt to the needs of the UWS and urban system [

19,

20]. It is a concept that strengthens the energy supply sustainability of the city by managing energy supply from intermittent sources of energy. In all cases where there is an excess of available reservoir volume, it can be used as energy storage, as is realized with PSH plants, for example in tourist areas [

19]. Thus, the shortcomings of the seasonal water system in tourist areas can become an opportunity to strengthen sustainability if they are adequately adapted.

If the water supply system is based on suitable (low cost) water resources and has suitable gravitational potential energy in the system, then in the winter rainy period when water consumption in tourist areas is very low, it can be used for green energy production as well as water supply to other economic sectors (agriculture, water bottling industry). Highly variable water supply systems can be adapted to supply water for irrigation. In the rainy winter period, off-season surplus capacity of the water supply system can be used for irrigation and supply seasonal water reservoirs for summer water uses for various purposes, because in season the system does not have (surplus) capacity for these purposes. Maintaining appropriate constant flow (use) of the water supply system in off-season period reduces deterioration of water quality due to long water retention, and provides additional revenue to cover the ongoing costs of off-season maintenance and operation. This integrates the system with local agriculture and industry that supplies tourist areas, which strengthens competitiveness.

There are numerous alternatives for using the system with a highly seasonal fluctuating demand, which always need to be systematically and comprehensively considered in order to strengthen its sustainability. The aforementioned integration of water supply systems with energy and food supply systems strengthens the resilience of the urban system and the security of society in adverse climatic periods and incident situations because the supply is multiplied and diversified.

Everything can be significantly improved if all the mentioned options are planned in advance as a planned adaptation measures for climate change, proactive strategy across infrastructures. These measures integrate climate resilience into development using systemic approaches.

3.4. Planning Integrated Recovery

The long-term vision for achieving sustainable urban environments is to create a “total urban system” [

21]. In essence, “total urban systems” is about understanding the whole picture—how everything in a city and its network of other cities works together—to solve complex problems and plan for a better future. Simply put, this means treating all relevant urban systems and resources integrally, and more fully networking them into a new, more comprehensive circular system to support the sustainability of citizens and the economy, and natural environment in a climate and resource-uncertain future. Integration and circulation of water, nutrient and energy reduces the sensitivity and vulnerability of individual water infrastructure, urban water systems and the urban environment as a whole, strengthens resilience and reduces risk by creating appropriate feedback loops to support supply. It is planning integrated recovery approach to managing waste, water, and energy by recovering valuable materials, nutrients, water and energy, technology (like composting/recycling), and policy for sustainable, cost-effective outcomes. Integration enables easier and more effective adaptation to all expected and incident stresses that the future brings. A true circular economy requires full integration across systems, businesses, and policies to function, moving beyond just recycling to a holistic design where waste is eliminated, and resources are continuously looped—it’s about connecting resources, consumption, and recovery into one closed-loop system for maximum sustainability and value. Integration isn’t a part of the circular economy; it’s the mechanism that makes it work, connecting everything from energy systems to material flows (water, food) into a cohesive, sustainable loop. Key steps include waste segregation, stakeholder engagement, feasibility analysis, and designing integrated systems to recover resources (water, nutrients, energy) while balancing economic, social, and environmental goals.

The bottom-up approach is considered an appropriate approach. This means that the internal integration and circulation of resources (water, nutrients, energy) within water supply, wastewater, and stormwater system separately should be first assessed. It is zero level of resource recovery, which in certain environments is the beginning of the application of CE strategy. At this step assessment and data collection occurred; water usage, energy demand, nutrients (N, P, K) stream, etc.

Then, possible paths and procedures for more complete resources recovery of water, nutrients and energy in UWS as whole are considered. This is the first level of integrated resource recovery process considering UWS resources together, not in silos. The key role/word is given to specialists; engineers specialized in planning, designing and building UWS in accordance with professional rules and practices. Relevant city departments, spatial planners and other professionals should always be consulted, as should the public and other stakeholders. Successful implementation of the CE at the first level is a prerequisite for higher and broader integration within the urban environment and the natural environment.

The second level of integration refers to the networking of the waste, water and energy circulation (feedbacks) process between urban waste (segregate organic waste), water and energy systems, and others. At this level, specialists in the management and development of urban infrastructure (capital) that function as interdependent recovery systems, and urban area play a major role (physical infrastructure, social structures and natural elements). They consult specialists and relevant stakeholders (community, utilities, government) in their area of expertise as needed, all interacting to create a city’s dynamic environment and performance, from resource flow and circulation to social cohesion.

The third level encompasses urban and regional forms and systems, where urban form is what a city looks like, regional form is how cities and land fit together, and planning is the action to shape both for the future. Forms describe the physical patterns, structures, and land uses of cities (urban) versus broader areas (regional), focusing on density, infrastructure, circular economy schemes, and settlement types, managed through planning to balance growth, sustainability, economic needs, and quality of life across scales from neighborhoods to entire regions. Understanding these forms and systems helps planners manage challenges like climate change, traffic congestion, pollution, housing and resources shortages, and economic disparities, fostering more sustainable, equitable, and efficient urban environments considering circular economy implementation as a strategy within integrate resource management framework.

Proposed systemic planning of urban adaptation achieves complete integration resources, rationality and reliability of circular economy implementation. The effectiveness and sustainability of circular economy implementation increases moving with bottom-up implementation, as well as system complexity. This is expected because the unknowns surrounding the application, processes and consequences are most recognizable locally. With networking, complexity, unknowns, suspicion and decision-making risk increase, which is expected because size, multidisciplinary subjects and actors, and the number and diversity of stakeholders increases. Assessment methodology and decision making process complexity and uncertainty grow due to large number of data and actors. AI can help in making decision by collecting and analyzes data from multiple sources, using machine learning algorithms to identify patterns, creates productive models to forecast outcomes, and provides recommendations. This is the expected future, but the first steps still need to be taken at the local level in accordance with local needs, locally available data, knowledge and acceptable technologies.

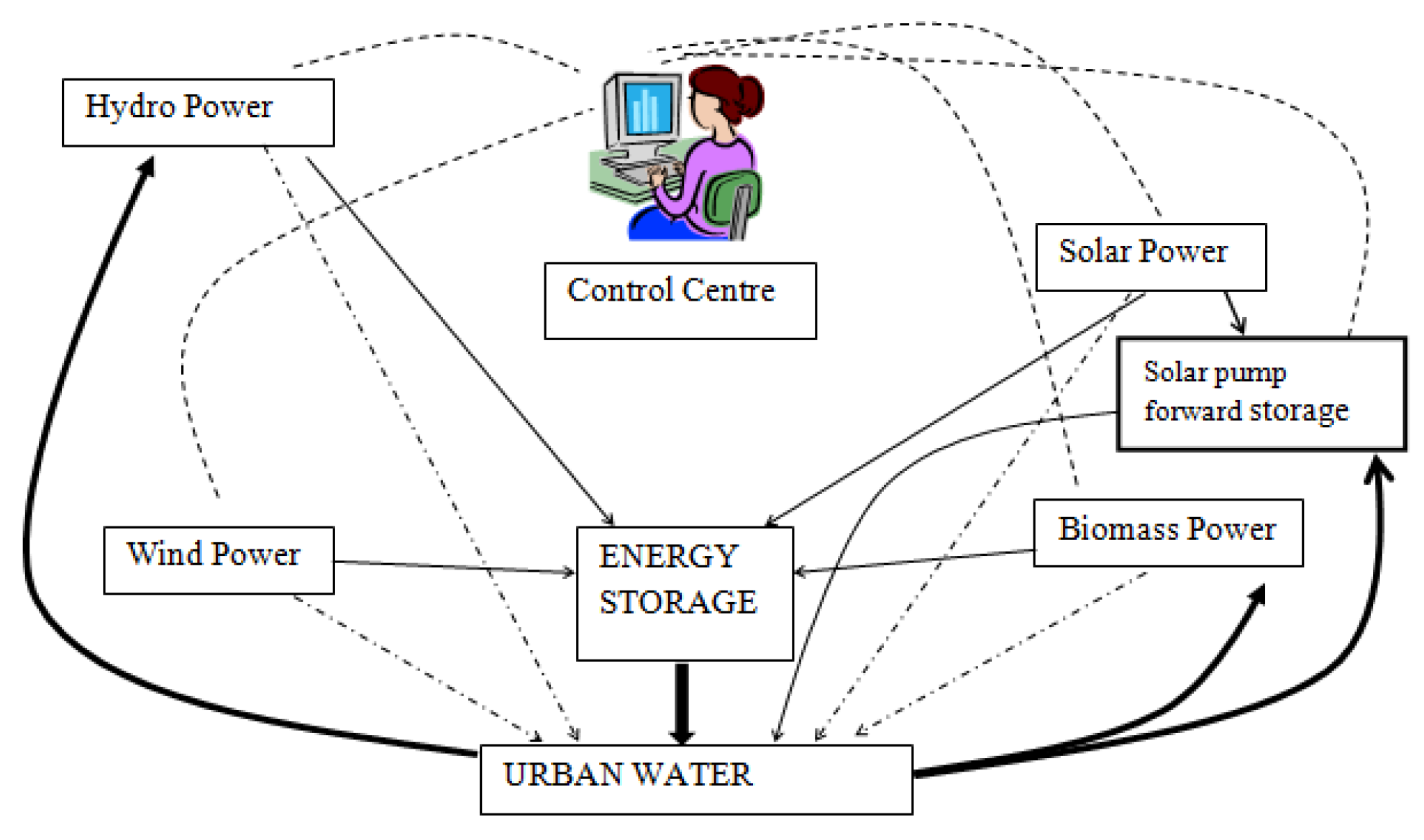

Complete and reliable supply of UWS with renewable resources requires the implementation of a local smart grid for a specific resource or group of resources (

Figure 7). The network should integrate all local urban resources or just some; say solar-based green energy, to achieve a secure and preferably full supply of UWS electricity. One of the characteristics of such a system is redundancy, since the UWS has more than one way to obtain energy. This would be a significant step towards a sustainable supply of UVS energy. And since UWS is essentially the bloodstream of every settlement, this would be a significant step towards sustainable living in urban communities. However, a smart grid must integrate advanced technologies: integration of renewable and distribution systems, real-time visualization and control, and energy storage and power electronics [

20]. It is expected that the sustainability of cities in the future will be based on similar solutions [

22].

4. Discussion

Climate change directly threatens the sustainability of summer seasonal tourism because the disruption caused by tourism is greatest during the warm and dry summer periods, when the demand for resources and pressure on the environment is greatest and the supply and recovery capacity of water and other resources is lowest. The greater the seasonality and summer demand greater sensitivity of the system and the lower adaptive capacity which leads to greater vulnerability. As a response to the threats of current development, a sustainable circular economy (SCE) is recommended. It effective management is crucial for ensuring future prosperity, as climate change, resources depletion and cost of resources supply, threatens economies and societies. The benefit of SCE driven for tourist areas, include provisioning (energy, food, water), regulating local climate, supporting nutrient cycles, cultural services and recreation. SCE build a stock and flow of tangible resources (energy, water, and nutrients), landscape, and living components (ecosystems). Although SCE is difficult to quantify monetarily, valuing recovery capital helps raise awareness and inform policy, revealing the costs of line-based UWS systems. This is can be recognized if the benefits and shortcomings of SCE are compared it with linear UWS.

The linear UWS is an open-loop system with high resource input and waste output (

Figure 8 (a), (b)). The water supply and sewerage system as an interconnected linear systems that follows a “take-purify-supply-collect-treated-dispose” model, extracting natural resources, creating water supply and wastewater services, and discarding collected wastewater as effluent into water resources. It is short-term design period objective of urban water supply and consumption, collection of used water, treatment and disposal. Outcome is waste, pollution, reliance on new water resources, and high sensitivity and vulnerability, low adaptation capacity to external and internal stressors. Stormwater system is also linear open-loop system that follows a „collect-drainage-treated-dispose” model, protecting urban area from flood, and discharge collected runoff water into local resources leading to depletion of local water resources capacity and increase pollution. As a linear open-loop stochastic flow system it is reducing sustainability of local natural and human environment since urbanization and stormwater system disconnect urban runoff from local hydrological cycle.

Circular UWS aims for closed-loop cycles, conserving resources and cutting pollution (

Figure 8 (c)). The circular UWS shifts to a “reduce-reuse-recycle” model, designing for longevity of services to keep water, nutrients and energy in use, minimizing waste and fostering sustainability. It is close-loop system that keeps resources in use, but open for additional resources supply minimizing resources depilation. The goal of such system is long-term services, resource efficiency, and waste minimization/elimination. Outcomes are reduction of virgin resources input and emission output, lower cost, and new service models that enhance resource and services security by reduction system sensitivity and vulnerability, and increasing adaptive capacity to external and internal stresses, and fostering sustainability.

So the linear systems focus on throughput that creates waste, while circular focus on prevention and maximization of resource values by design; linear for obsolescence while circular for durability of services and disassembly. As results linear system is damaging for environment, while circular enhances environment. It is obvious that circular systems reduce sensitivity and vulnerability and strengthen the resilience of tourist areas and their activities both in relation to climate change and to internal threats arising from extremely high variability in resource use. SCE can mitigate the unsteady flow of resources in the system and environment, the seasonal nature of economic activities, and the resulting consequences on urban metabolism and consumption of resources that have a great impact on the operation and sustainability of UWS and other urban infrastructure capitals; financial resources (public/private) and essential physical/social systems (food, energy).

Input-output thermodynamics provides a framework to track energy/matter transformations, ensuring that what goes in must come out in some form, even if it’s less useful than intended. In essence, input-output thermodynamics provides the accounting framework (mass/energy balances) to analyze how physical systems like dissipative structures as it is UWS (defined by boundaries) transform inputs into desired outputs, respecting fundamental conservation laws. Input energy and matter isn’t lost but changes form; energy/matter in = energy/matter out + energy/matter stored.

The second law of thermodynamics state that every process increases disorder (entropy). When applies to open systems by considering the total entropy change of the system plus its surroundings, requiring that total entropy must increase (or stay constant for ideal reversible processes) as the system exchanges mass and energy, meaning entropy can enter/leave via heat/mass flow, but overall disorder grows. It means that reuse and recovery isn’t 100% efficient since material/water quality degrades, requiring energy and water input and generating waste/entropy, making perfect resource and material loops impossible. The efficiency of the system (Useful Output / Total Input) defines entropy of the system. In a one-way input-output UWS, entropy is therefore significant and can be slowed down by reducing the total input (abstraction of water) and increasing the useful output (recovered resources). In order to reduce the peak abstraction of water, reservoirs are used that regulate the input-output process (

Figure 8 (b)). The goal is to reduce maximal abstraction (Qmax,supply, m

3/s) and bring it closer to the average demand value (Qave,demand, m

3/s).

The management model for achieving sustainability of water supply is one-way street and implies; minimization of losses (Vloss, m3), reduction of total amount of water abstraction (Vin, m3) and peak supply capacity (Qin, m3/s), and this in relation to all resources necessary for the operation of the system (energy, matter, capitals). Sewerage system management model is also simple and minimizes losses/uncontrolled leaks (Vloss) (pollution of environment) and installed capacity of structures/system elements (Qmax), in order to reduce energy and material consumption. The same applies to a stormwater system that minimizes flooding damage and the installed capacity of the drainage structure (Qmax). Appropriate mass balance estimation considers „primarily virgin inputs” ; water in water supply system; use water in wastewater system; rainfall in stormwater system, and waste and discharge is an exit point. In a one-way input-output UWS, entropy is therefore significant and can be slowed down by reducing the total input and increasing the useful output. It is a strategy that has long been practiced to strengthen the sustainability of the UWS. Peak runoff in urban stormwater system is regulated in a similar way by implementation of retention basins/reservoirs. These are all actions that strengthen the sustainability of the UWS, mitigate shocks/variabilities, and strengthen resource allocation.

The process that generates, consumes and accumulates resources takes place in the circulatory system, so the mass balance is more complex. Namely, mass balance of circular system tracking input of virgin resources (Vin) mixed with recovery (Vrec) and/or reuse (Vreuse) resources, that is (Vgen = Vrec + Vreuse) in supply, and waste resources (Vout), resources accumulated (Vacum) and loss resources (Vcon) as output, so it applies:

So, the key difference in mass balance is the mixing feedback flow of resources (Vrec + Vren) and resources of production processes (Vcon + Vacum). In addition, resource recovery requires the application of reservoirs/storage to ensure circulation sustainability (

Figure 8 (c)). It follows that the increase in (Vout + Vcon) causes the increase in entropy, and the Vacum increases resistance and sustainability.

In a circular model, mass (energy) balance helps manage the transition by tracking recovery or/and reuse water, energy and matter mixed with virgin ones. It allows companies to claim a certain percentage of recycled content in a final production of resources (water, energy and matter), showing progress towards circularity and reduced virgin resources use, effectively closing the loop on water, energy and matter flows. It goes without saying that greater resource recovery strengthens the sustainability of the UWS. Such systems are less sensitive and vulnerable to external and internal pressures because it allows for planning and management with adaptation. Success is defined by the quantity of the accumulation of resources (water, energy, nutrients). CUWS designs out waste, keeps materials in use via reuse, and recovery, and regenerates nature, creating a closed system with minimal new resource input and waste output, using methods like mass balance to track recovery content.

The key difference in mass balance between linear UWS and CUWS is the

flow: traditional linear is a one-way street to environment and landfill, while circular aims to perpetually cycle resources, using techniques like mass balance to allocate recycled input to specific services. The core difference is ”where” matter and energy is used: linear systems burn and utilize significant amounts in primary resource processing and supply, while circular systems shift matter and energy to maintaining loops (reuse, recovery), leading to a much lower net demand by avoiding the most matter/energy-intensive initial steps, and high seasonal demand. That’s why CUWS energetically and materially efficient and environmentally sound, especially for tourist areas that relying on sustainable environment that support framework for

sustainable destination program [

10,

23,

24].

The solution lies in the application of sustainability design that aims to move away from linear “unsustainable” flows towards circular systems that reduce inherent entropy. Actions like wastewater treatment and distribution inherently produce entropy. Reusing treated water and biogas from treatment plant, for instance, can significantly decrease the overall entropy budget of the system, improving sustainability. Information entropy concept is also used to assess the complexity and order of urban ecosystems, including water systems, helping to gauge developmental levels and harmony. High entropy means high randomness in data (high unpredictability) while low entropy means low randomness. For example, water demand in tourist areas has significantly greater unpredictability because the tourism economy is very sensitive to external and internal stresses, which increases randomness and risk.

UWS are open, dissipative systems that naturally increase entropy (losses, disorder) as water moves through them. Designing for non/less-dissipative flow means making the system more organized, creating more uniform flow and minimizing energy dissipation, water losses and pollution (minimizing entropy) by CE implementation that is by creating CUWS. In order to achieve this, it is necessary to apply system analysis using entropy budgets (entropy production + entropy exchange) to quantify losses and assess the impact of feedback loops for water, energy and nutrient recovery and use. In addition, it is necessary to apply sustainability modeling that employing entropy concept to guide urban planning towards circularity and reduced environmental impact.

The urban wastewater recovery system contributes the most to the sustainability of the urban system in tourist areas because it complements and strengthens local water-food-energy nexus [

10,

13,

25]. Such system transform sewage into valuable resources like clean water, energy (heat/biogas), and nutrients (phosphorus/nitrogen) by using advanced treatment (membranes, heat pumps, anaerobic digestion) to turn treatment plants into “resource factories” for reuse in irrigation, industry, or even drinking, reducing reliance on fresh water and creating a circular economy. These systems tackle resource scarcity and climate change by recovering heat from drains for district heating or extracting biogas for power, making cities more sustainable is reliable because it has constant input and thus output, so the storage is small. Its application in tourist areas has a significant impact on the sustainability of the economy and society.

Stormwater system contributes to the recovery of water and energy [

14,

26]. It is a complex and demanding system to manage because it has periodic operation, that is stochastic input. Urban stormwater recovery systems capture, treat, and reuse rainwater and surface runoff from cities to reduce demand for drinking water, prevent flooding, and lower pollution in waterways, using techniques like rain harvesting, green roofs, rain gardens, permeable pavements, biofilters, and larger-scale storage/treatment facilities to manage water as a resource rather than a waste product, following principles of Sustainable Drainage Systems [

27]. Due to the great variability of the input, each use requires some form of reservoir that supports reliable resource recovery and use.

The water supply system allows for energy recovery. It is a continuous water flow system, which is quite variable during the day and throughout the year, especially in tourist areas that have specific water consumption dynamics. Urban water supply recovery systems are innovative approaches to creating resilient, sustainable urban water management by integrating decentralized sources like greywater/rainwater harvesting, advanced wastewater treatment (water reclamation), and smart infrastructure to reduce water and energy losses (pipe hydro-electric turbines) , diversify supply, and reuse treated water for non-potable (or even potable) needs, moving beyond traditional “take-make-waste” models to ensure water security amidst climate change and urban growth.

These systems offer a paradigm shift, making UWSs more adaptive, efficient, and sustainable for future challenges [

24]. Networking feedback loops (water, energy, nutrients) and their storages within CUWS, and within CUS, strengthen the effectiveness, resilience and security of resource recovery. Integrate resource management is framework to managing waste, water, and energy in tourist areas by recovering valuable materials, nutrients, and energy, providing environmental recovery, economic value and sustainable development.

5. Conclusion

The motivation for implementation is a clearly defined policy and legal framework (UN [

1] and EU [

28,

29]), growing demand for natural resources and increasing climate risks, environmental pollution and biodiversity loss, uncertain climate future and resource supply, rising prices of resources and utilities, etc.. The main candidates for the implementation of the CE in Croatia are tourist areas, especially islands. These are karst areas lacking reliable water, food and energy resources. Seasonal tourism generates extremely high variability in water, food and energy demand and consequently high variability in environmental impacts through controlled and uncontrolled outputs. The demand is greatest in period when natural water and food resources are limited and most vulnerable due to long summer droughts, , and therefore cannot function without importing resources, which increases sensitivity and vulnerability.

Furthermore, the fixed dimensions of the UWS infrastructure adapted to peak demand flow that occurs in a short period of time, 2 weeks in August, make the system is unused for the largest period of the year in its entire life cycle. The fix/gray infrastructure, unlike the green, is not flexible and thus has a low capacity to adapt to external and internal changes. Such functioning of the system inevitably leads to a decrease in its technological and economic efficiency, generating losses and costs for the local population and the tourist economy. Adaptation to climate variability and demand is costly and complex, which threatens the sustainability of urban life processes. This is why the application of resource cycling is very useful in tourist areas. Through dynamic closure and circulation, sustainability as well as the safety of system operation and durability is strengthened. Besides that, networking with resource-related systems that have the same variability of use, the sustainability and cost-effectiveness of implementing CE are additionally increased. This is the path towards reducing the entropy of the system and business that is, strengthening competitiveness of tourist destinations through lower costs and strengthening environmental safety. In addition, circular solutions are suitable backup system for tourist areas, especially on the islands which are far from land-based supply chains.

However, sustainability of a circular system is not guaranteed by itself, so it must be carefully and comprehensively planned and implemented [

30]. Therefore, it is necessary to study the technological viability of possible concepts and assess their socio-economic sustainability considering: technology framework, economics and value chain, environment and health issues, and society and politics framework.

The technological viability of CUWS can be objectively assessed by the first and second laws of thermodynamics. The laws of thermodynamics, especially the first (energy conservation) and second (increasing entropy/disorder), set fundamental limits and guide principles for technology’s sustainability, showing that all transformations create waste heat and increase universal disorder, necessitating closed-loop systems, reliance on external solar energy (like nature), efficient resource use (exergy), and a shift from linear consumption to circular economies to operate within Earth’s physical boundaries.

The ranking of possible options is process that boils down to the appreciation of the entropy of the system constructing composite indicator or using modern tech like AI and cloud computing for better data, energy and water management, and sustainable operations, ultimately driving environmental, social and governance goals and a CE [

31]. However, technology assessment, in the context of sustainability, represents a systematic, evidence-based process of evaluating the potential environmental, social, and economic consequences of a technology throughout its lifecycle by multi-objective decision making.

Socio-economic sustainability evaluation assesses how development of CUWS impacts people’s lives, communities, and economies, balancing social well-being (health, culture, equity) with economic vitality (jobs, income) while considering environmental limits, using indicators like income, education, health, and community engagement to identify positive/negative effects and guide mitigation for balanced, long-term prosperity [32]. It often uses frameworks like ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) or integrated models (SEETA) to analyze baseline conditions and predict impacts, ensuring benefits are maximized and negative consequences minimized for all stakeholders.

It is very useful to integrate all relevant CUS within integrated resource management framework because this achieves greater safety, resilience, and cost-effectiveness. The wider and deeper the integration networking, the greater the safety and benefit for the environment and society. Feedbacks loops and stocks creation under the flow of water, matter and energy are the core of the urban circulation system. That’s why at the heart of effective water, energy and nutrient management in urban areas lays the principle of integrated water resources management, which treats entire urban resource cycles as an interconnected system.

Funding

This research was not supported.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the.article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

UWS Urban water system

CE Circular economy

IRM Integrated resources management

US Urban system

CUWS Circular urban water system

CUS Circular urban system

DS Dissipative structures

SCE Sustainable circular economy

IVAs Integrate climate vulnerability assessment

References

- UN: United Nation’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2020.

- Wikipedia. Tourism in Croatia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tourism_in_Croatia (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Delgado, A.; Diego, J.R.; Carlo, A. A.; Midori, M. Water in Circular Economy and Resilience (WICER); World Bank: Washington, DC, 2021. [Google Scholar]