The whole-system leak measurements conducted during a grid upgrade campaign in Saarlouis, Germany, are described including the measurement protocol, data analysis approach, and probabilistic methods for scaling results to the national level.

2.1. Study Area

The gas grid in Saarlouis is operated by Stadtwerke Saarlouis GmbH, a grid operator that is also responsible for water, electricity, telecommunications, and district heating in the city of Saarlouis [

24]. The grid evolved from a coal gas grid, which was converted to a natural gas grid in the 1970s. Initially supplying only the historic center and its former industries, it eventually grew to supply modern suburban districts as well. The analysis covers installations constructed in the 1950s through to modern installations built in the 2020s. The interior piping systems include appliances between 25 kW and 400 kW with single or multi-metering installations. They cover systems with single or mixed materials, such as unalloyed steel, copper pipes, malleable cast iron, multilayer composite pipes, or stainless steel corrugated pipes. An unknown number of residential installations have been in operation for over 50 years, while others have been updated several times since they first went into operation. These residential installations are used in single- and multi-family homes, commercial establishments, kindergartens, schools, retirement homes, and social buildings.

The measurements presented in this study were conducted during a grid pressure upgrade campaign initiated by the utility operator. The grid operating pressure was to be increased from 23 mbar to 55 mbar above atmospheric pressure, which necessitated the installation of gas pressure regulators at individual residential connections to maintain the downstream operating pressure at 23 mbar above ambient. To ensure the safety of grid operation after this pressure increase, whole-system leak rate measurements were performed for each installation before regulator installation and before overall grid pressure increase. This operational context provided a unique opportunity to conduct systematic leak quantification across a large sample of installations without requiring modifications to existing systems. Homeowners were informed about the measurement campaign and the results, and were asked to take action to reduce leak rates if necessary. No installation was modified before conducting the leak measurements. Appliances were turned off during testing, isolating interior piping leaks from operational appliance emissions. The protocol targeted pipes and connections between the meter and appliances.

The 473 leakage tests were carried out in 2024 in a residential area representative of average middle-class living areas in Germany. This represents 8.3% of all 5,712 installations in Saarlouis [

25].

The sample size of 473 installations (8.3% of Saarlouis total, 0.0025% of German total) was determined by the grid operator’s infrastructure requirements rather than a priori sample size calculations. Post-hoc analysis indicates this sample size provides >90% probability of detecting the observed high-emitter prevalence (1.5% exceeding 1 ) with 95% confidence, assuming binomial sampling. For estimating the mean emission rate, the observed 95% confidence interval spans ±46% of the mean (0.067 [0.041, 0.098] ). Standard sample size formulas for estimating a mean with coefficient of variation CV≈0.5 (based on the observed skewed distribution) indicate that N≈400 installations are required to achieve ±20% precision at 95% confidence, confirming the adequacy of the sample for central tendency estimation. However, for the rarest events (installations exceeding 5 , with only 1 case observed), the sample provides limited precision, reflected in wide confidence intervals for the highest-emission bins in the national upscaling.

The area and the installations were chosen based on the requirements of the grid operator for increasing the grid pressure. These include human capacity constraints, overall budget, and the possibility of hydraulically separating part of the grid from the mesh grid using an existing gas governor station for the gas supply. Another variable was the high demand in winter combined with height differences in the grid regularly resulting in increased emergency services due to pressure deviations. By increasing the grid pressure to a higher level and installing gas regulators for each installation, it is possible to minimize these emergency service calls. A first part of the grid pressure was increased in 2010, a second part in 2023, and a third part in 2024, with more to follow.

Especially during the recent energy crisis in Europe, it became apparent that low-pressure producer gas systems are not suitable for emergency situations. They lack technology that protects houses from unexpectedly high or low pressures, such as gas failsafe devices. High pressures can lead to dangerous incidents, such as one in Massachusetts [

26], where several houses were damaged by explosions and fires due to missing over-pressure protection. A similar incident happened in Germany in 1988, when the over-pressure protection in a main line was blocked due to technical failures resulting in explosions and fires in residential buildings as well as fatalities [

27]. The installation of gas regulators helps the grid operator mitigate risks resulting from too high or too low grid pressures.

2.2. Measurement Method

The tests were carried out during installation of gas pressure regulators, which had not been part of any existing installation. This offered a controlled and consistent testing opportunity where the gas meter was temporarily removed and the measurement device was connected at the same location. No modifications to the installation systems were necessary, which ensured a realistic leakage behavior of the entire interior gas installation, including all piping and gas appliance inlets.

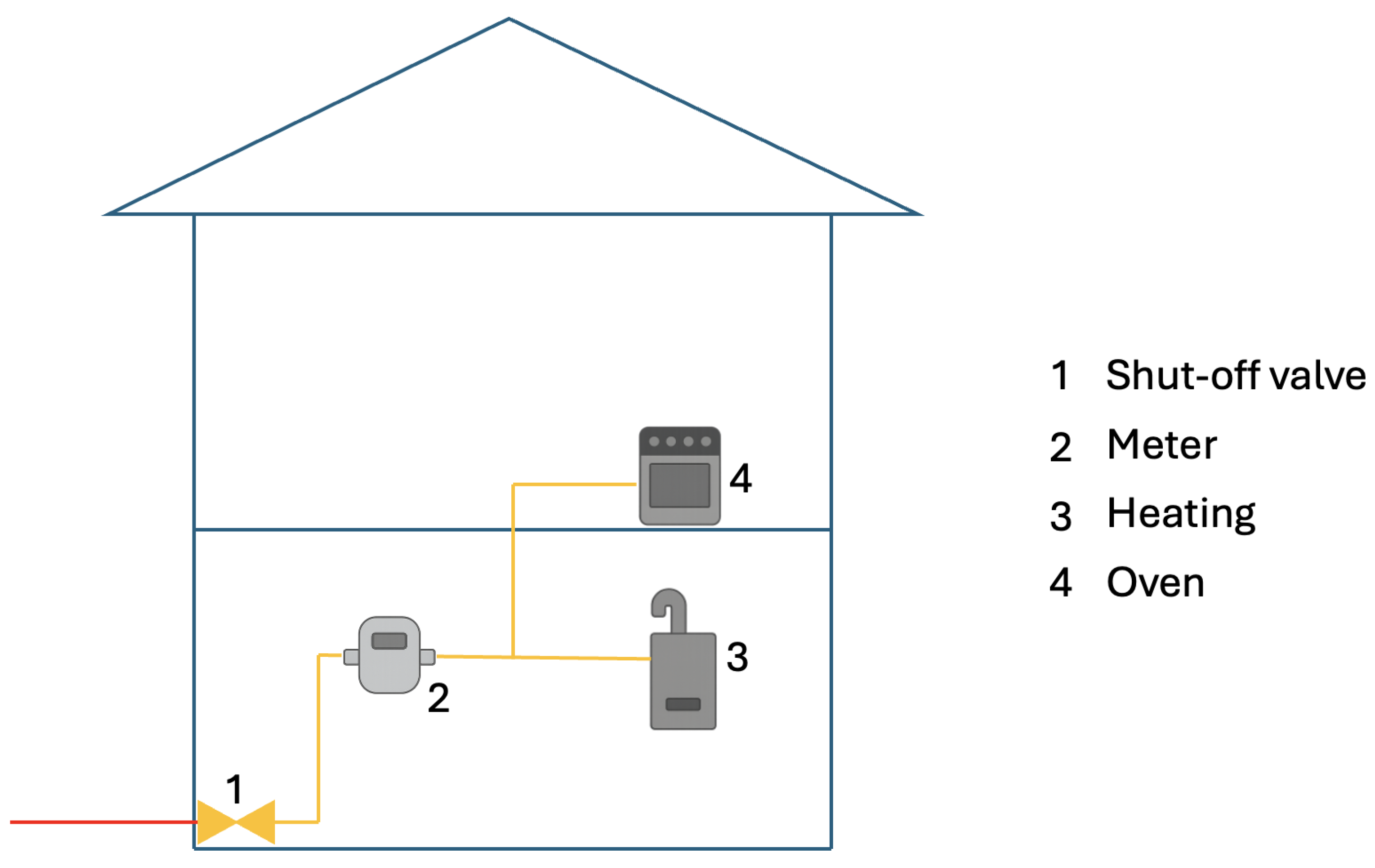

The procedure always covered the entire interior gas installation, including all accessible pipes, joints, and appliance connection points. As shown in

Figure 1, the data collection includes all piping of the residential system as marked in yellow. The procedure allowed a consistent testing of the entire system, preserving realistic leaking conditions. The measurement device was attached at the location of the meter (2) and allowed measuring the installation between the main shut-off valve (1) and the gas appliances (3) and (4). For the measurement, the meter had to be temporarily removed; the appliances were deactivated but still connected to the installation.

The measurement protocol followed several steps from informing the customer all the way to notifying homeowners when possible leakages were discovered. The initial homes chosen were those where installations were expected to be easiest and where gas service lines had been renewed recently. Afterwards, houses were chosen by street, starting from those closest to the gas governor station and moving to the furthest, allowing the pressure drop in the grid to have the lowest impact on the regulator installation. Also, critical houses, such as retirement homes or bakeries, were left to the end, allowing the current system to function without changes for as long as possible. All homeowners were personally informed about the necessary appointments between one and three weeks in advance with a time slot of 3 hours during which the measurement and installation of the gas regulator were planned. Installations were measured in an order determined by grid infrastructure logistics, starting with homes closest to the gas governor station and proceeding outward, while prioritizing critical facilities (retirement homes, bakeries) last to minimize service disruptions. The final dataset of 473 installations represents 8.3% of the city total and spans construction periods from the 1950s through 2020s with diverse materials and configurations. They were asked to provide access to all meters and installation components during the appointment. The measurements were conducted with the GasTest delta 3 from German manufacturer Esders GmbH, a certified handheld device for pressure-based leakage testing according to DVGW G 600 and G 459-2 [

10,

28]. The device includes an integrated pump which can measure flow rates up to 45

, a high-precision digital pressure sensor and can be used for installations with an operating pressure of up to 1 bar with a resolution of 1 mbar and a maximum error of 0.5% [

29].

Measurement uncertainty from the GasTest delta 3 device (±2.0% accuracy for leak rates 0-10 , ±0.01 resolution) was propagated through emission calculations using standard Gaussian error propagation methods. These uncertainties were incorporated into the Monte Carlo simulations as additional variance terms.

All tests were conducted by trained technicians, and the fittings used were checked for leakages using handheld gas detection devices PM 580 by Sewerin GmbH, which measure leakages in the parts-per-million (ppm) range [

30]. Upon arriving at the different installations, the technical team first explained the procedure to the homeowners and then turned off all appliances. This step was followed by safely removing the meter and installing the GasTest delta 3.

The device follows pre-programmed steps automatically and advises the technicians on which steps to perform. After installing and starting the device, it automatically fills an internal gas bladder with natural gas from the installation. Once the gas bladder was filled, it was essential to shut off the gas supply to the installation by closing the shut-off valve that separates the installation from the gas grid. The GasTest delta 3 then filled the installation with natural gas to the preset test pressure of typically 27 mbar above ambient. In 98.3% of all tests, the set testing pressure was 27 mbar above ambient, the minimum test pressure required by DVGW regulation G 600. This test pressure of 27 mbar above ambient is slightly higher than the normal downstream operating pressure of 23 mbar above ambient to account for variability and to ensure a conservative testing condition [

10]. Note that this 27 mbar above ambient test pressure is unrelated to the 55 mbar above ambient grid pressure increase; most testing was conducted at the standardized test pressure of 27 mbar above ambient regardless prior to the systematic grid pressure increase/upgrade. In eight cases, the technicians used slightly higher testing pressures as a precaution for installations where local installation conditions, operating pressures and shut-off pressures were unclear. Based upon manufacturer specifications, these variations do not affect the accuracy of the results, since leakage is determined by the pressure drop over time, not the testing pressure itself. The device then waits maximum five minutes for the system pressure to stabilize at the preset pressure during the adjustment phase. During that time, the device automatically measures the installation volume based on the flow and time for pressure increase and saves it to the data file. If the pressure does not stabilize, the device automatically stops and highlights possible causes, such as malfunctioning shut-off valves. Otherwise the device automatically continues in the measuring phase. All tests were conducted following DVGW G 600, which specifies an observation time of seven minutes to assess pressure decay and determine the leakage rate [

10]. Results and original data are logged at 1 Hz for later analysis. The device shows the main results on the display, such as pressure drops or leak rates. Based on the results, the technicians decided whether a test run should be repeated or finalized. If a test run was finalized, the device was safely detached from the installation and the gas regulators were installed, as well as the previously detached meter. No test had to be repeated, showing that all results were within the expected range and no main shut-off valve was malfunctioning. The main shut-off valve was then opened and the appliances were returned to operation. One final round of leak detection was performed at the gas regulator and the meter using the handheld gas detection devices PM 580. After each test was finalized, the technicians completed the corresponding documentation in accordance with grid operator requirements and informed the homeowners about the results. The documentation is then automatically uploaded to a cloud which only the operator has access to. All results can be downloaded from the cloud as .json files or pdf documents.

2.3. Data Analysis

All data were consolidated into a single database and subjected to quality control. The raw .json files were checked for completeness, consistency of metadata (for example testing pressure, leak rates, results), and anomalies in the recorded time series. To avoid duplicated data, all files were imported into a database and analyzed for duplicates, and technician notes were cross-checked against measurement files. No duplicated test results were found, and all notes were consistent with the recorded notes and results.

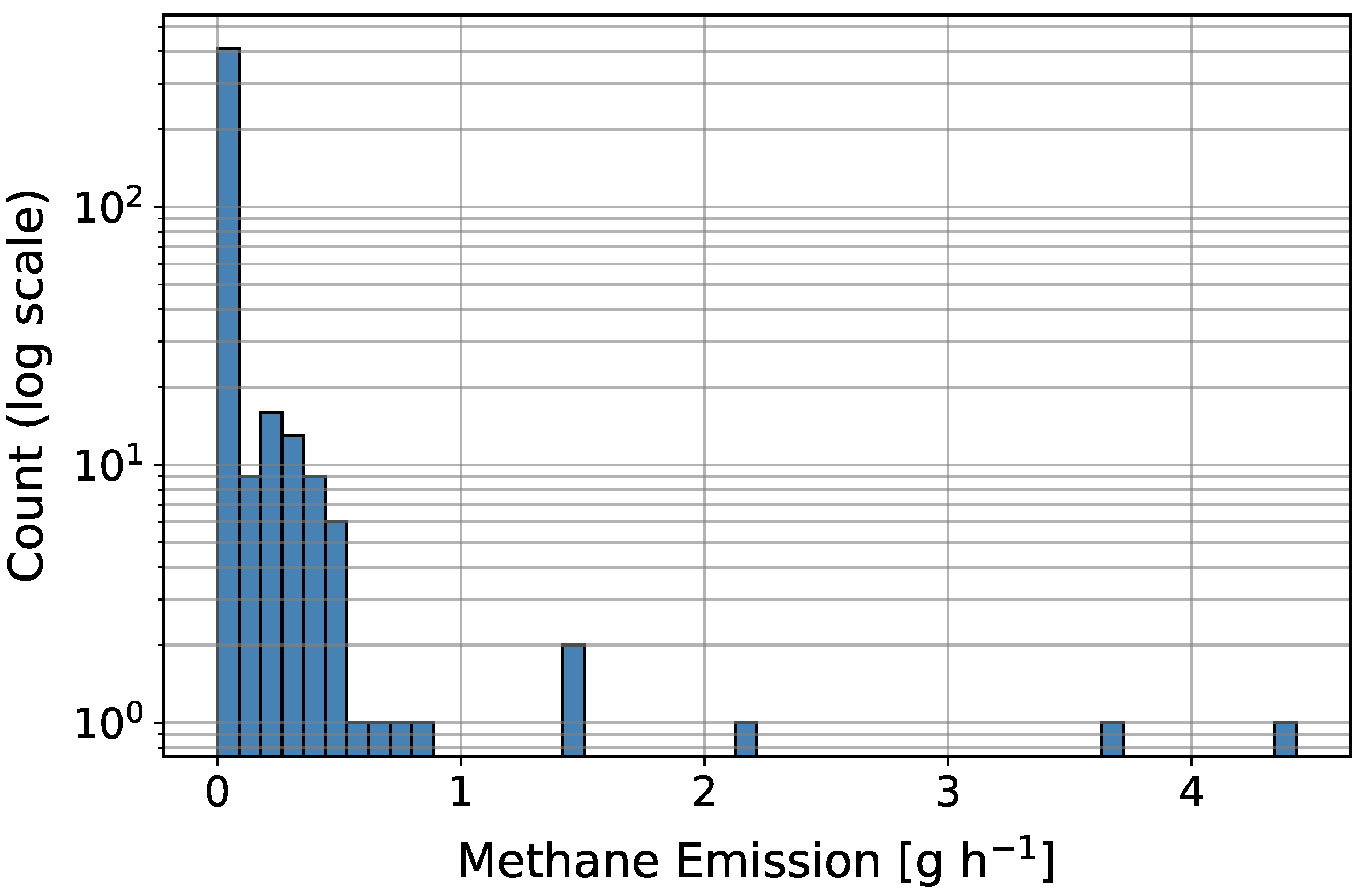

During data processing, 165 measurements showed a negative measured leak rate. These are erroneous measurements according to the manufacturer and investigation showed that this occurs when the internal gas bladder of the device, which is used for setting the higher pressure, was not fully emptied before testing. Given the specifications of the GasTest delta 3, these values fall within the uncertainty band around zero. The device has a resolution of 0.01 and an accuracy of % within a range of 0 to 10 to the full scale. This leads to a Lower Detection Limit (LDL) of −1. The measured apparent negative leak rates ranged between -0.09 and -0.0001 , and all positive numbers that ranged between 0 and 0.2 were identified as systematic errors due to statistical noise rather than physical leakage, but were included in further analysis as non-detected leak rates of 0 . This aligns with the practical LDL of the GasTest delta 3. No other systematic errors were found in the measurements.

Leakage rates in residential systems in Germany are grouped into three sections based on DVGW G 600. Group 1 represents leakages with no risks, Group 2 with acceptable risks, where mitigating action is required within four weeks, and Group 3 with unacceptable and dangerous risks which require immediate mitigating actions. The technical rule points out leak rates which help grouping leakages. Group 1 is defined by leak rates lower than 1 −1, Group 2 with leak rates between 1 and 5 −1, and Group 3 with leak rates greater than 5 −1. Leakages in Group 3 are considered dangerous due to the high leak rate and the effect these methane emissions can have resulting in explosions.

2.4. Creation of Emission Factors and National Emissions Estimate

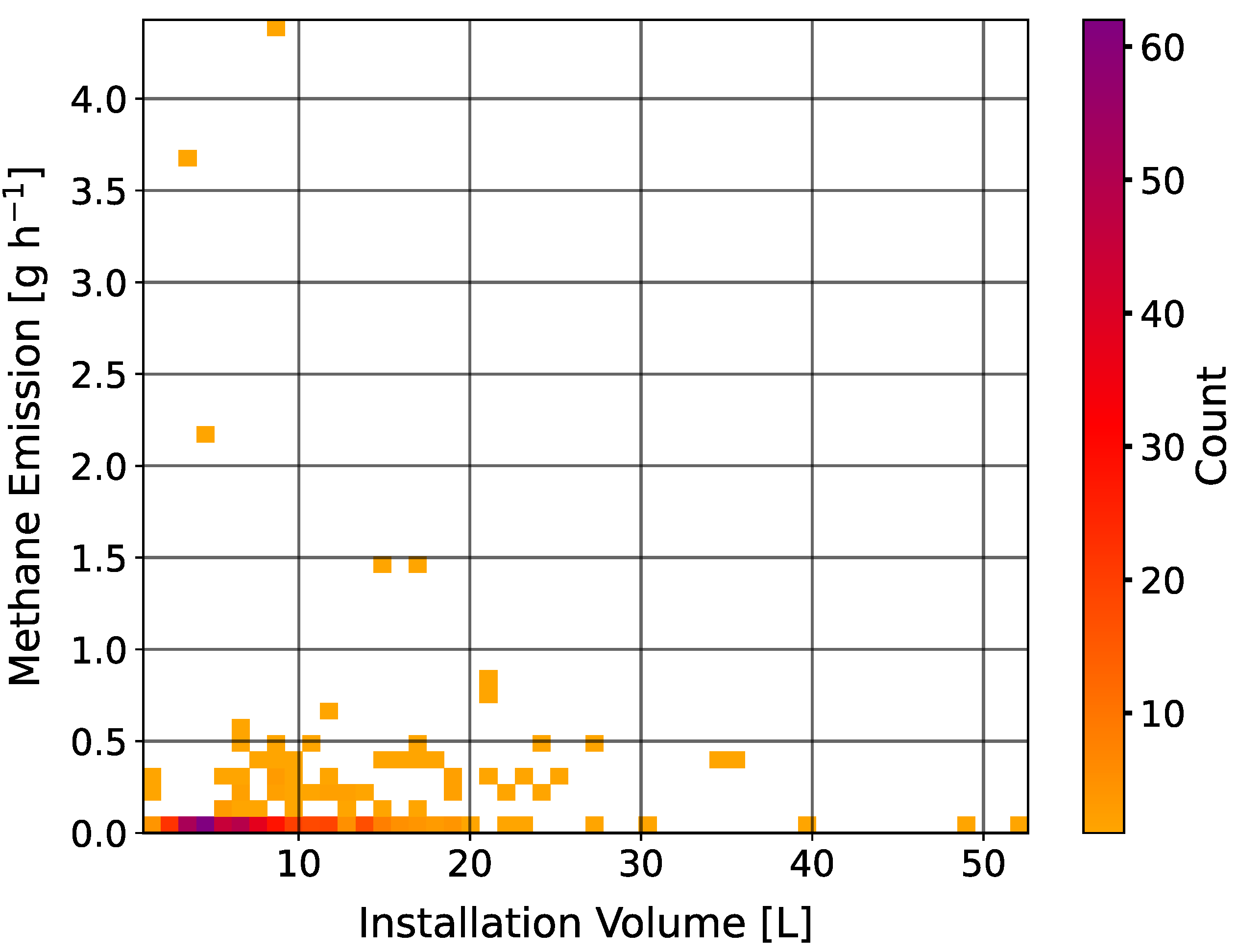

After reviewing and cleaning the data, the analysis of the final dataset provided insight into leakage behavior and support more accurate methane emission factors for the residential sector. Due to missing information about age and detailed material used in the installation, the calculated emission factors do not include such details.

Emission factors were calculated in two ways. First normalized only by the number of installations, second normalized by the estimated interior piping volume, assuming that larger systems have a greater probability of leakage. Methane Emissions depend on the density and the methane content of the applied natural gas. The density based on the meter temperature was measured as 0.7499 at 288.15 K temperature and 1,013.25 mbar absolute pressure and methane content in the natural gas was determined to 95.802 mol-% using Process Gas Chromatographs.

The GasTest delta 3 reports leak rates as volumetric flows in

at test pressure and ambient conditions. For emission calculations, these values were converted to standard liters per hour (

) using the ideal gas law at reference conditions and then to mass units (

) using the measured gas composition. Due to missing ambient temperature data, it is not possible to standardize the gas temperature. Therefore, the ambient temperature and the standard temperature were both set to 288.15 K and the standard leak rate is only based on the measured leak rate and the standardized pressure. Methane emissions are calculated based on the mean leak rate for each installation. The number of total residential natural gas connections in Germany are reported by the DVGW at 19 million households [

31]. This number accounts for all natural gas connections and cannot be divided into specific numbers for amounts using the same natural gas composition. Therefore it is assumed that all Germany follows the same natural gas composition, knowing that some areas have different gas compositions with lower or higher methane contents. Ranges of uncertainty were propagated using Monte Carlo simulations, combining a variation in standard leak rates, total installation counts, and confidence intervals of mean emissions. The chosen confidence intervals were set to 95 %. This allows scaling the results from a measured sample to a city level or national levels with upper and lower bounds. While Saarlouis was selected to represent an average German middle-class residential area, several factors may limit national generalizability. The city’s gas infrastructure evolved from a coal gas grid converted in the 1970s, and the grid pressure increase necessitating regulator installation (which enabled this study) may not be typical of all German cities. Regional variations in building codes, climate, installation practices, and demographic factors could influence leak distributions. Despite these limitations, the 473-installation sample (0.0025% of national total) provides the most comprehensive systematic leak survey of residential interior piping in Germany to date.

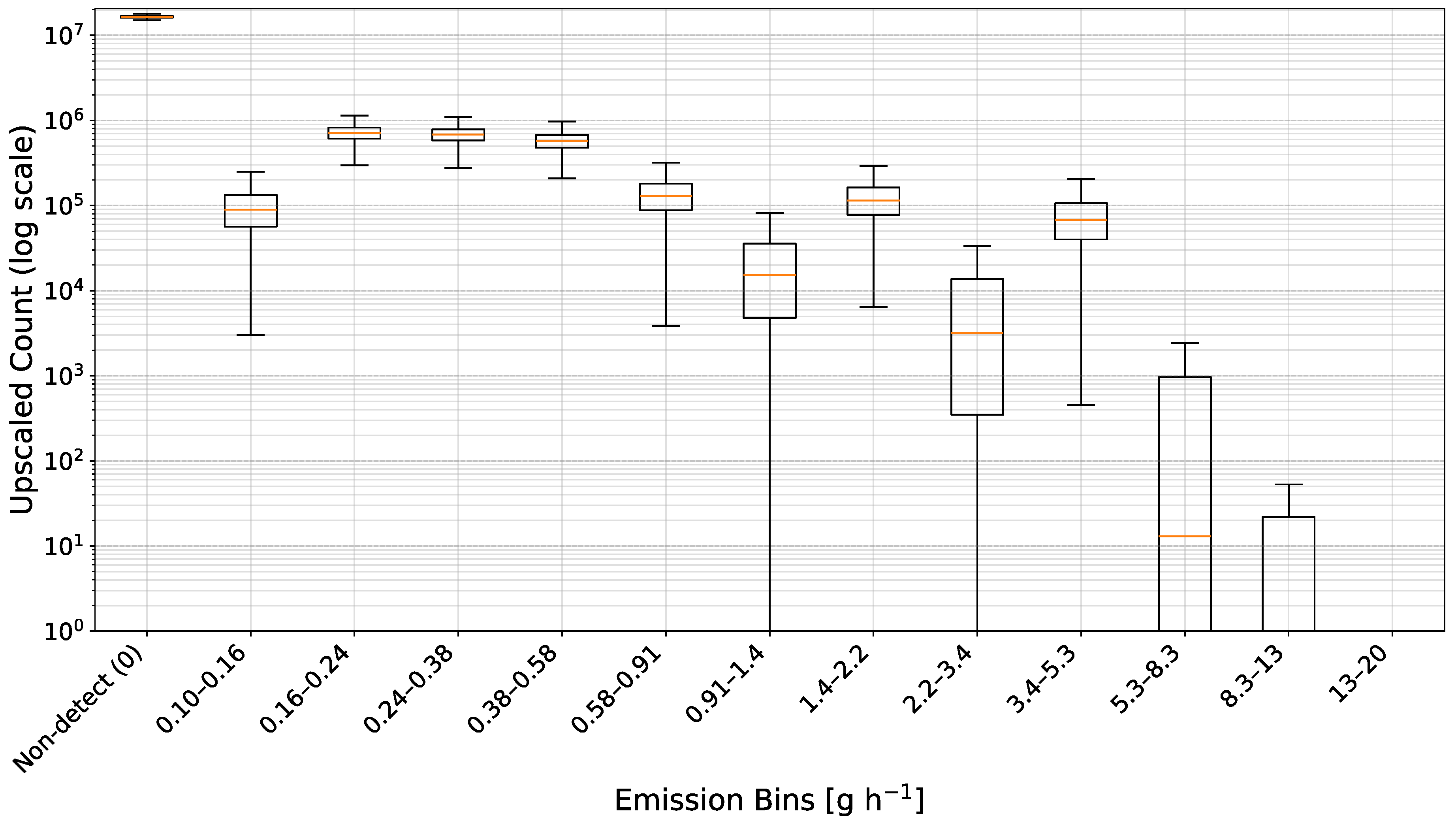

For the national upscaling, the methane emission rates measured in the installations were first grouped into

bins. The first bin (

) contains all non-detects (measurements at or below the LDL of 0.2

, assigned emission rate of 0

). The remaining bins (

to

) are logarithmically spaced between

−1 and 20

−1. The upper bound of 20

−1 was chosen to be consistent with already published ranges of leaks in residential appliances and installations. Upper leak rates between 10

−1 and 20

−1 are reported in malfunctioning units [

6,

22]; higher emissions were not reported. For each positive-emission bin, an emission rate was defined as the geometric mean (midpoint on log scale) of the upper and lower bin boundaries. This was used as the characteristic emission level for each bin in the national upscaling.

Uncertainty in the total number of German residential natural gas installations was accounted for by modelling the total number of connections

N as a lognormal random variable. The parameters of this distribution were chosen such that the 95 % interval spans from 18 to 20 million connections, centred around the reported value of 19 million [

31]. In each Monte Carlo iteration

b, a value

was drawn from this distribution and used as the total number of residential installations to be allocated across emission bins.

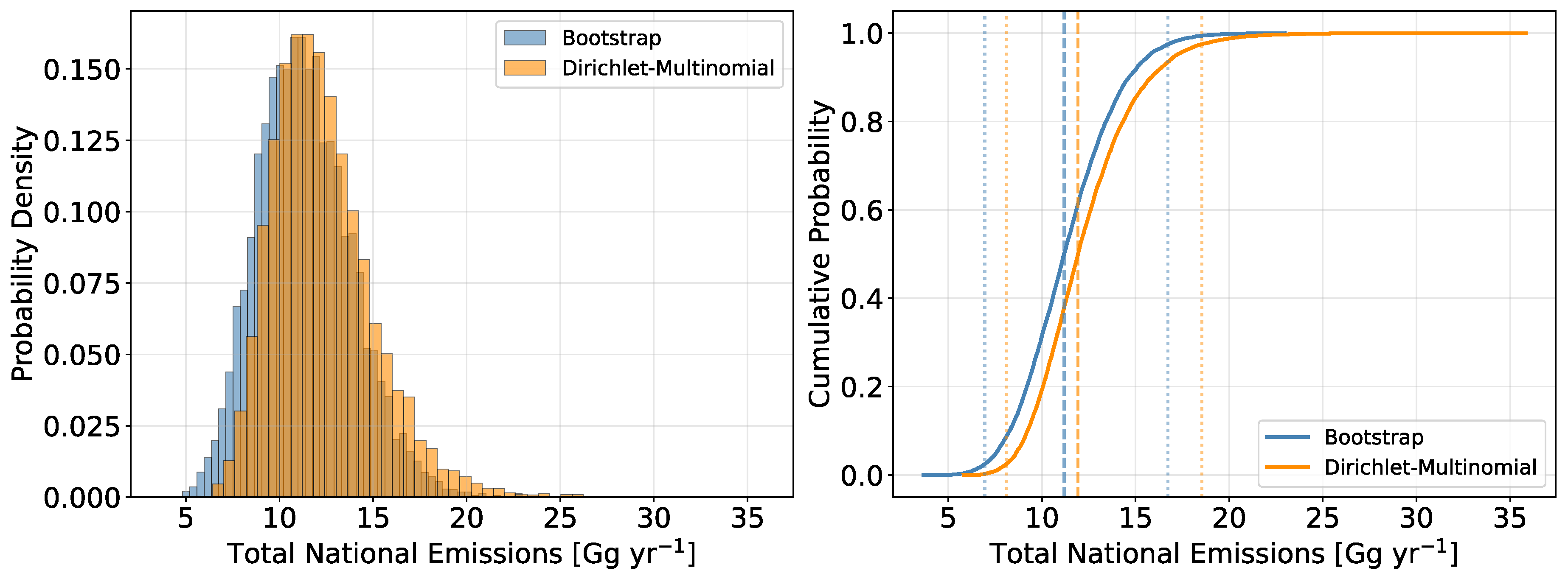

Two statistical approaches were used to upscale the observed distribution of emission bins from the 473 tested installations to the national level of Germany. In the first approach, the empirical bin assignment based on the 473 installations was resampled with replacement in each Monte Carlo iteration to obtain a bootstrap sample. Each sample was converted into bin probabilities , and a multinomial draw with parameters and provided national counts per bin. In the second approach, the empirical bin counts were combined with a weakly informative prior derived from a lognormal fit to the positive emission rates. This prior reflects the expectation of a right-skewed distribution. It shows a small fraction of higher-emitting installations, and produces posterior bin probabilities applying a Dirichlet distribution. These probabilities were then used in the same multinomial allocation step as for the bootstrapped approach. The empirical shape of the existing analyzed distribution was preserved by the bootstrap approach. The Dirichlet-multinomial formulation adds a modest amount of smoothing to better represent sparsely populated or empty bins in a way that the observed heavy-tailed behavior is followed. Additional linear-scale plots were added for the higher-emission bins to highlight the contribution of rare but potentially high-impact installations.

The reported confidence intervals (95% confidence interval (CI): 11.36 [6.95, 16.73] for bootstrap) reflect only: (1) sampling uncertainty from the 473-installation dataset, (2) uncertainty in total German connection count, and (3) measurement uncertainty from device specifications (±2.0%). These intervals do NOT capture additional uncertainty from: (4) geographic variability (Saarlouis vs. other German cities), (5) temporal variability (single snapshot vs. long-term average), or (6) potential systematic differences between the measured cohort (undergoing regulator installation) and the broader national building stock. Incorporating these additional sources would substantially widen the confidence intervals, though quantifying the magnitude requires multi-city, multi-season sampling campaigns. Future work should include multi-city sampling to better quantify geographic variability and enable more robust national extrapolation.

For each Monte Carlo iteration, national methane emissions were obtained by multiplying the national count in each bin with the corresponding representative emission rate. The results were summarized across all bins to obtain a total emission in . These were converted to annual emissions in . The procedure was repeated for 10,000 iterations to obtain stable distributions of national emissions for both applied statistical approaches. The final national estimates are reported as the Monte Carlo mean and median, together with the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles as a 95 % confidence interval. This framework propagates measurement uncertainty, sampling variability in the dataset of the 473 installations It also includes uncertainty in the total number of German residential gas connections for a consistent national emissions estimate.

To visually assess how emissions are distributed across bins and how the upscaling treats sparsely populated or empty bins, the distributions of national bin counts from the Monte Carlo simulations were summarised using boxplots on a logarithmic scale.