Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

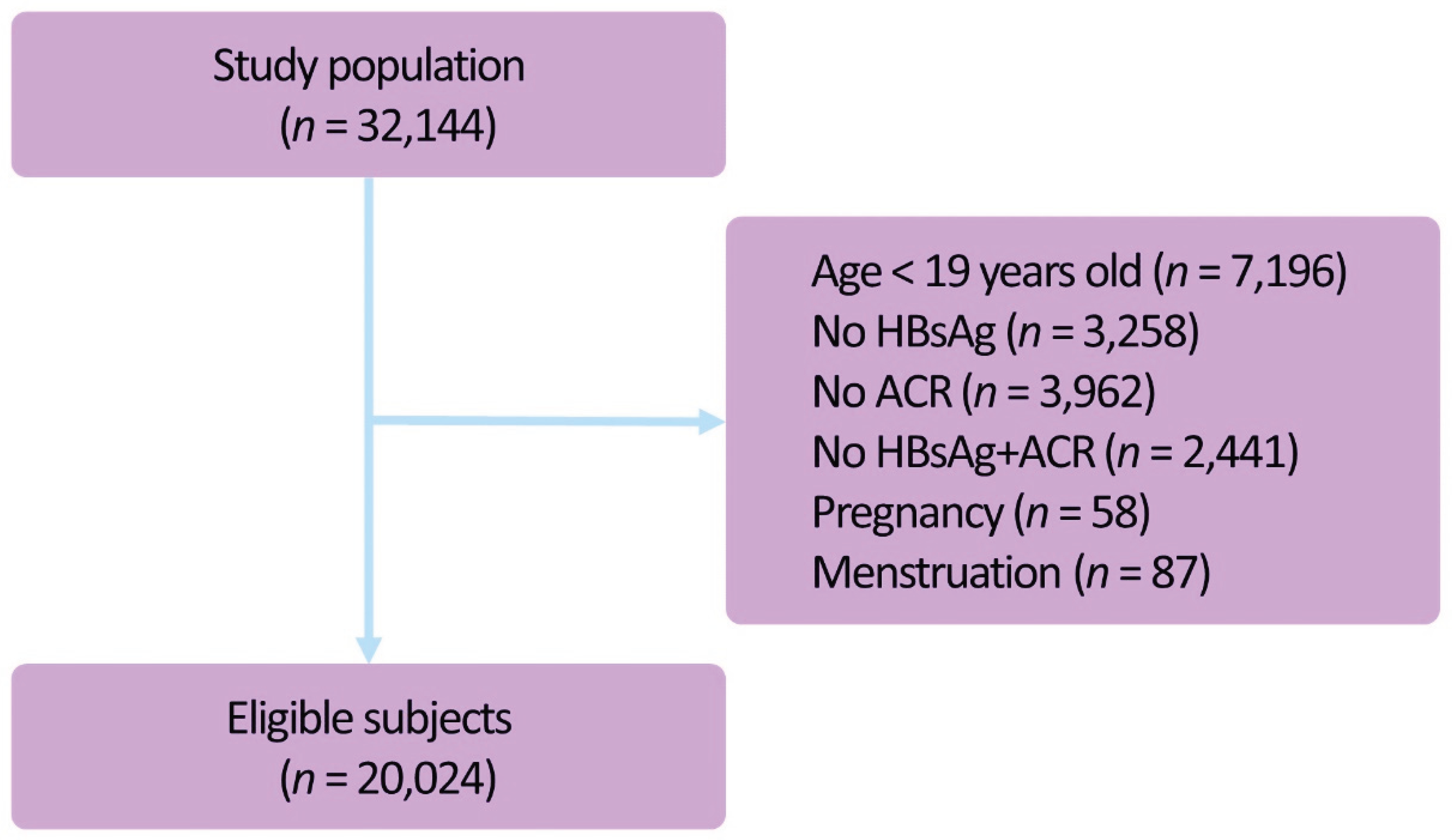

Background: The prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is estimated at approximately 3% in Korea, and it is also accompanied by extra-hepatic manifestations as well as chronic hepatitis. Of these, HBV glomerulonephritis occurs due to the immune complex deposit; it is a serious condition that may cause renal failure. Methods: We analyzed the data obtained from adults aged 19 years or older who participated in the KNHANES V-2 and 3 (2011 and 2012) and VI-1 and 2 (2013 and 2014), for which we estimated the prevalence of HBV infection and compared albuminuria and spot urine ACR between the HBV infection group and the control group. Results: A total of 20,024 subjects were enrolled in the current study. The prevalence of HBV infection was 3.8%. There were no significant differences in the prevalence of albuminuria (5.6±1.0 % vs. 6.9±0.2 %, respectively) (P=0.233) and spot urine ACR (22.23±8.95 vs. 17.87±1.05 mcg/mg, respectively) (P=0.629) between the HBV infection group and the control group. In addition, according to a subgroup analysis, there was also no significant difference in the prevalence of albuminuria between the HBV infection group, accompanied by chronic diseases such as HTN, DM, metabolic syndrome and dyslipidemia, and the control group. Conclusions: Based on our results, it can be concluded that only a regular follow-up rather than a meticulous monitoring of microalbuminuria would be sufficient in the subjects with HBV infection.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cohort

2.2. Definitions

2.3. Laboratory Measurement

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Relationship Between the Prevalence of Albuminuria and HBV Infection

3.3. Relationship Between the Prevalence of Albuminuria and HBV Infection in Each Subgroup

4. Discussion

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis B. Fact Sheet No. 204; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. Available online: http://who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/ (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Park, N.H.; Chung, Y.H.; Lee, H.S. Impacts of vaccination on hepatitis B viral infections in Korea over a 25-year period. Intervirology 2010, 53, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, H.B.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, J.K.; Yim, H.J. Current status of liver diseases in Korea: Hepatitis B. Korean J. Hepatol. 2009, 15, S13–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gocke, D.J. Extrahepatic manifestations of viral hepatitis. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1975, 270, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, M.; Kleinknecht, C. Membranous glomerulonephritis and hepatitis B virus infection. Nephron 1980, 26, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggelinkhuizen, J.; Sinclair-Smith, C.; Stannard, L.M.; Smuts, H. Hepatitis B virus-associated membranous glomerulonephritis. Arch. Dis. Child. 1983, 58, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwest Pediatric Nephrology Study Group. Hepatitis B surface antigenemia in North American children with membranous glomerulonephropathy. J. Pediatr. 1985, 106, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzosko, W.J.; Krawczynski, K.; Nazarewicz, T.; Morzycka, M.; Nowoslawski, A. Glomerulonephritis associated with hepatitis B surface antigen immune complexes in children. Lancet 1974, 2, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.; Hutchison, A. Cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2009, 5, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.F.; Chuang, W.L. Viral hepatitis and proteinuria in an area endemic for hepatitis B and C infections: Another chain of link? J. Intern. Med. 2006, 260, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chobanian, A.V.; Bakris, G.L.; Black, H.R.; Cushman, W.C.; Green, L.A.; Izzo, J.L.; Jones, D.W.; Materson, B.J.; Oparil, S.; Wright, J.T.; et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7). JAMA 2003, 289, 2560–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, S8–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IDF Epidemiology Task Force Consensus Group. The metabolic syndrome—A new worldwide definition. Lancet 2005, 366, 1059–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, D.B.; Bruns, D.E.; Goldstein, D.E.; Maclaren, N.K.; McDonald, J.M.; Parrott, M. Guidelines and recommendations for laboratory analysis in the diagnosis and management of diabetes mellitus. Clin. Chem. 2002, 48, 436–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, B.; Shorey, J.; Barrera, A.; Stastny, P.; Eigenbrodt, E.; Hull, A.R.; Carter, N.W. Glomerulonephritis with deposition of Australia antigen–antibody complexes in the glomerular basement membrane. Lancet 1971, 2, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takekoshi, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Miyakawa, Y.; Yoshizawa, H.; Takahashi, K.; Mayumi, M. Free “small” and IgG-associated “large” hepatitis B e antigen in the serum and glomerular capillary walls of two patients with membranous glomerulonephritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1979, 300, 814–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.J.; Couser, W.G. Hepatitis B infection and renal disease: Clinical, immunopathogenetic and therapeutic considerations. Kidney Int. 1990, 37, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panomsak, S.; Lewsuwan, S.; Kanjanabuch, T. Hepatitis B virus-associated nephropathies in adults: A clinical study in Thailand. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2006, 89, S151–S156. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; Fan, X.; Mou, L.; Yang, Y.; Ren, J.; Lin, S. Association of reduced renal function with hepatitis B virus infection and elevated alanine aminotransferase. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 7, 1561–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.X.; Kiberd, B.A.; Clark, W.F.; Haynes, R.B.; Clase, C.M. Albuminuria and renal insufficiency prevalence guides population screening: Results from the NHANES III. Kidney Int. 2002, 61, 2165–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.H.; Yu, J.H.; Ko, S.H.; Kwon, H.S.; Kim, D.J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, C.S.; Song, K.H.; Won, J.C.; Lim, S.; et al. Prevalence and determinants of diabetic nephropathy in Korea: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes Metab. J. 2014, 38, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liangpunsakul, S.; Chalasani, N. Relationship between hepatitis C and microalbuminuria: Results from the NHANES III. Kidney Int. 2005, 67, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | Hepatitis B | Control | ||

| N=20,024 | N=717 (3.8%) | N=19,307 (96.2%) | P-value | |

| Age [years] | 45.86±0.20 | 46.33±0.59 | 45.84±0.20 | 0.404 |

| Gender (men) [%] | 52.9±0.4 (n=9, 024) | 58.9±2.2 (n=367) | 52.6± 0.4 (n=8, 657) | 0.006 |

| Smoker [%] | 24.6±0.4 (n=3, 915) | 28.3±2.1 (n=169) | 24.5±0.4 (n=3, 746) | 0.063 |

| Alcohol [%] | 13.0±0.3 (n=2, 028) | 13.4±1.7 (n=76) | 13.0±0.3 (n=1, 952) | 0.822 |

| BMI kg/m2 | 23.80±0.04 | 23.98±0.15 | 23.80±0.04 | 0.225 |

| AST IU/L | 22.41±0.12 | 30.00±1.70 | 22.12±0.11 | <0.001 |

| ALT IU/L | 22.60±0.21 | 34.06±3.12 | 22.15±0.19 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin g/dL | 14.32±0.02 | 14.53±0.07 | 14.31±0.02 | 0.002 |

| BUN mg/dL | 14.15±0.04 | 14.23±0.19 | 14.14±0.04 | 0.657 |

| Creatinine mg/dL | 0.85±0.00 | 0.87±0.01 | 0.85±0.00 | 0.080 |

| eGFR | 96.44±0.18 | 95.41±0.67 | 96.48±0.18 | 0.112 |

| Fasting glucose mg/dL | 98.07±0.20 | 98.14±0.92 | 98.07±0.20 | 0.936 |

| Cholesterol mg/dL | 188.41±0.36 | 184.15±1.40 | 188.58±0.36 | 0.002 |

| TG mg/dL | 137.72±1.12 | 119.78±4.58 | 138.42±1.14 | 0.000 |

| HDL mg/dL | 52.17±0.12 | 51.60±0.58 | 52.19±0.12 | 0.303 |

| albuminuria [%] | 6.9±0.2 (n=1, 639) | 5.6±1.0 | 6.9±0.2 | 0.233 |

| microalbuminuria [%] | 6.0±0.2 (n=1, 422) | 4.7±0.9 (n=36) | 6.1±0.2 (n=1, 386) | 0.200 |

| macroalbuminuria [%] | 0.9±0.1 (n=217) | 0.9±0.3 (n=9) | 0.9±0.1 (n=208) | 0.951 |

| ACR mcg/mg | 18.03±1.06 | 22.23±8.95 | 17.87±1.05 | 0.629 |

| ACR mcg/mg * | 192.69±14.43 | 316.89±149.21 | 188.74±14.08 | 0.393 |

| Total | Hepatitis B | Control | ||

| N=20,024 | N=717 (3.8%) | N=19,307 (96.2%) | P-value | |

| Hypertension [%] | 25.2±0.4 (n=6, 166) | 24.4±1.8 (n=202) | 25.2±0.5 (n=5, 964) | 0.660 |

| Diabetes mellitus [%] | 9.1±0.2 (n=2, 246) | 7.7±1.2 (n=62) | 9.2±0.3 (n=2, 184) | 0.255 |

| Metabolic syndrome [%] | 20.2±0.4 (n=4, 715) | 19.0±1.8 (n=156) | 20.2±0.4 (n=4, 559) | 0.497 |

| CKD [%] | 8.3±0.3 (n=2, 114) | 6.6±1.0 (n=55) | 8.4±0.3 (n=2, 059) | 0.120 |

| CKD [%] * | 2.4±0.1 (n=736) | 1.9±0.5 (n=16) | 2.4±0.1 (n=720) | 0.376 |

| Dyslipidemia [%] | 21.9±0.4 (n=4, 889) | 13.2±1.4 (n=99) | 22.3±0.4 (n=4, 790) | <0.001 |

| Total | Hepatitis B | Control | P-value | OR | |

| N=20,024 | N=717 (3.8%) | N=19,307 (96.2%) | |||

| Normotension | N=13, 858 | N=515 | N=13, 343 | ||

| ACR mcg/mg ACR mcg/mg * |

9.25±0.58 130.32±13.48 |

5.44±0.62 90.63±31.02 |

9.41±0.60 130.93±13.66 |

<0.001 0.231 |

|

| Albuminuria | 3.8±0.2 (n=611) | 1.5±0.6 (n=10) | 3.9±0.2 (n=601) | 0.010 | 0.382 (0.184-0.795) |

| microalbuminuria [%] | 3.5±0.2 (n=556) | 1.4±0.6 (n=8) | 3.6±0.2 (n=548) | 0.015 | 0.376 (0.171-0.829) |

| macroalbuminuria [%] | 0.3±0.0 (n=55) | 0.1±0.1 (n=2) | 0.3±0.1 (n=53) | 0.284 | 0.457 (0.109-1.921) |

| Hypertension | N=6, 166 | N=202 | N=5, 964 | ||

| ACR mcg/mg ACR mcg/mg * |

44.08±3.79 237.13±22.26 |

74.21±36.29 375.75±187.01 |

42.94±3.70 231.06±21.76 |

0.392 0.443 |

|

| Albuminuria | 16.0±0.6 (n=1, 028) | 18.3±3.4 (n=35) | 15.9±0.6 (n=993) | 0.458 | 1.186 (0.755-1.863) |

| microalbuminuria [%] | 13.4±0.6 (n=866) | 15.1±3.2 (n=28) | 13.4±0.6 (n=838) | 0.559 | 1.162 (0.702-1.921) |

| macroalbuminuria [%] | 2.5±0.2 (n=162) | 3.2±1.3 (n=7) | 2.5±0.2 (n=155) | 0.537 | 1.317 (0.549-3.159) |

| Total | Hepatitis B | Control | |||

| N=20,024 | N=717 (3.8%) | N=19,307 (96.2%) | P-value | OR | |

| Non-DM | N=17, 778 | N=655 | N=17, 123 | ||

| ACR mcg/mg ACR mcg/mg * |

12.49±0.80 152.24±14.26 |

9.05±1.56 122.66±32.54 |

12.62±0.83 153.12±14.64 |

0.042 0.392 |

|

| Albuminuria | 5.2±0.2 (n=1, 076) | 3.9±0.8 (n=32) | 5.3±0.2 (n=1, 044) | 0.143 | 0.739 (0.493-1.108) |

| microalbuminuria [%] | 4.7±0.2 (n=968) | 3.5±0.7 (n=27) | 4.8±0.2 ( n=941) | 0.149 | 0.727 (0.472-1.121) |

| macroalbuminuria [%] | 0.5±0.1 (n=108) | 0.4±0.2(n=5) | 0.5±0.1 (n=103) | 0.724 | 0.848 (0.339-2.123) |

| DM | N=2, 246 | N=62 | N=2, 184 | ||

| ACR mcg/mg ACR mcg/mg * |

73.32±8.00 281.79±32.51 |

179.71±111.35 672.55±404.69 |

69.81±7.40 267.66±30.13 |

0.325 0.319 |

|

| Albuminuria | 23.6±1.0 (n=563) | 25.7±7.3 (n=13) | 23.5±1.0 (n=550) | 0.757 | 1.127 (0.529-2.401) |

| microalbuminuria [%] | 19.2±1.0 (n=454) | 19.4±6.9 (n=9) | 19.2±1.0 (n=445) | 0.928 | 1.041 (0.432-2.509) |

| macroalbuminuria [%] | 4.4±0.5 (n=109) | 6.3±3.6(n=4) | 4.3±0.5 (n=105) | 0.518 | 1.508 (0.434-5.241) |

| Total | Hepatitis B | Control | |||

| N=20,024 | N=717 (3.8%) | N=19,307 (96.2%) | P-value | OR | |

| Normal | N=15, 135 | N=561 | N=14, 748 | ||

| ACR mcg/mg ACR mcg/mg* |

13.37±0.92 161.24±15.57 |

19.04±9.12 308.96±178.98 |

13.11±0.87 155.67±14.62 |

0.518 0.394 |

|

| Albuminuria | 5.5±0.2 (n=1, 017) | 4.7±1.0 (n=32) | 5.5±0.2 (n=985) | 0.475 | 0.853 (0.550-1.321) |

| microalbuminuria [%] | 4.9±0.2 (n=903) | 4.0±0.9 (n=25) | 5.0±0.2 (n=878) | 0.334 | 0.791 (0.490-1.274) |

| macroalbuminuria [%] | 0.5±0.1 (n=114) | 0.8±0.3(n=7) | 0.5±0.1 (n=107) | 0.446 | 1.425 (0.572-3.548) |

| Dyslipidemia | N=4, 889 | N=99 | N=4, 790 | ||

| ACR mcg/mg ACR mcg/mg* |

34.65±3.47 244.08±27.29 |

43.25±31.67 337.35±263.73 |

34.45±3.47 241.97±27.30 |

0.782 0.717 |

|

| Albuminuria | 11.9±0.6 (n=622) | 11.5±3.7 (n=13) | 11.9±0.6 (n=609) | 0.913 | 0.960 (0.459-2.006) |

| microalbuminuria [%] | 10.0±0.5 (n=519) | 9.9±3.6 (n=11) | 10.0±0.6 (n=508) | 0.968 | 0.984 (0.437-2.214) |

| macroalbuminuria [%] | 2.0±0.2 (n=103) | 1.7±1.2 (n=2) | 2.0±0.2 (n=101) | 0.813 | 0.838 (0.193-3.632) |

| Total | Hepatitis B | Control | |||

| N=20, 024 | N=717 (3.8%) | N=19, 307 (96.2%) | P-value | OR | |

| Normal | N=15,309 | N=561 | N=14,748 | ||

| ACR mcg/mg ACR mcg/mg* |

13.82±1.07 191.56±20.81 |

22.47±10.98 445.00±246.32 |

13.48±1.03 183.02±19.78 |

0.415 0.289 |

|

| Albuminuria | 4.9±0.2 (n=896) | 4.1±1.0 (n=21) | 4.9±0.2 (n=875) | 0498 | 0.838 (0.503-1.397) |

| microalbuminuria [%] | 4.3±0.2 (n=778) | 3.4±1.0 (n=17) | 4.3±0.2 (n=761) | 0.407 | 0.787 (0.446-1.388) |

| macroalbuminuria [%] | 0.6±0.1 (n=118) | 0.7±0.4 (n=4) | 0.6±0.1(n=114) | 0.705 | 1.234 (0.415-3.673) |

| Metabolic syn. | N=4, 715 | N=156 | N=4, 559 | ||

| ACR mcg/mg ACR mcg/mg* |

34.70±2.90 194.17±18.46 |

21.19±4.05 126.57±27.76 |

35.20±3.01 196.16±19.00 |

0.007 0.041 |

|

| Albuminuria | 14.8±0.7 (n=743) | 11.9±2.6 (n=24) | 14.9±0.7 (n=719) | 0.309 | 0.772 (0.469-1.272) |

| microalbuminuria [%] | 12.8±0.6 (n=644) | 10.2±2.5 (n=19) | 12.9±0.7 (n=625) | 0.338 | 0.766 (0.443-1.324) |

| macroalbuminuria [%] | 2.0±0.2 (n=99) | 1.7±0.8 (n=5) | 2.0±0.2 (n=94) | 0.672 | 0.814 (0.313-2.114) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.