Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Serological Tests

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

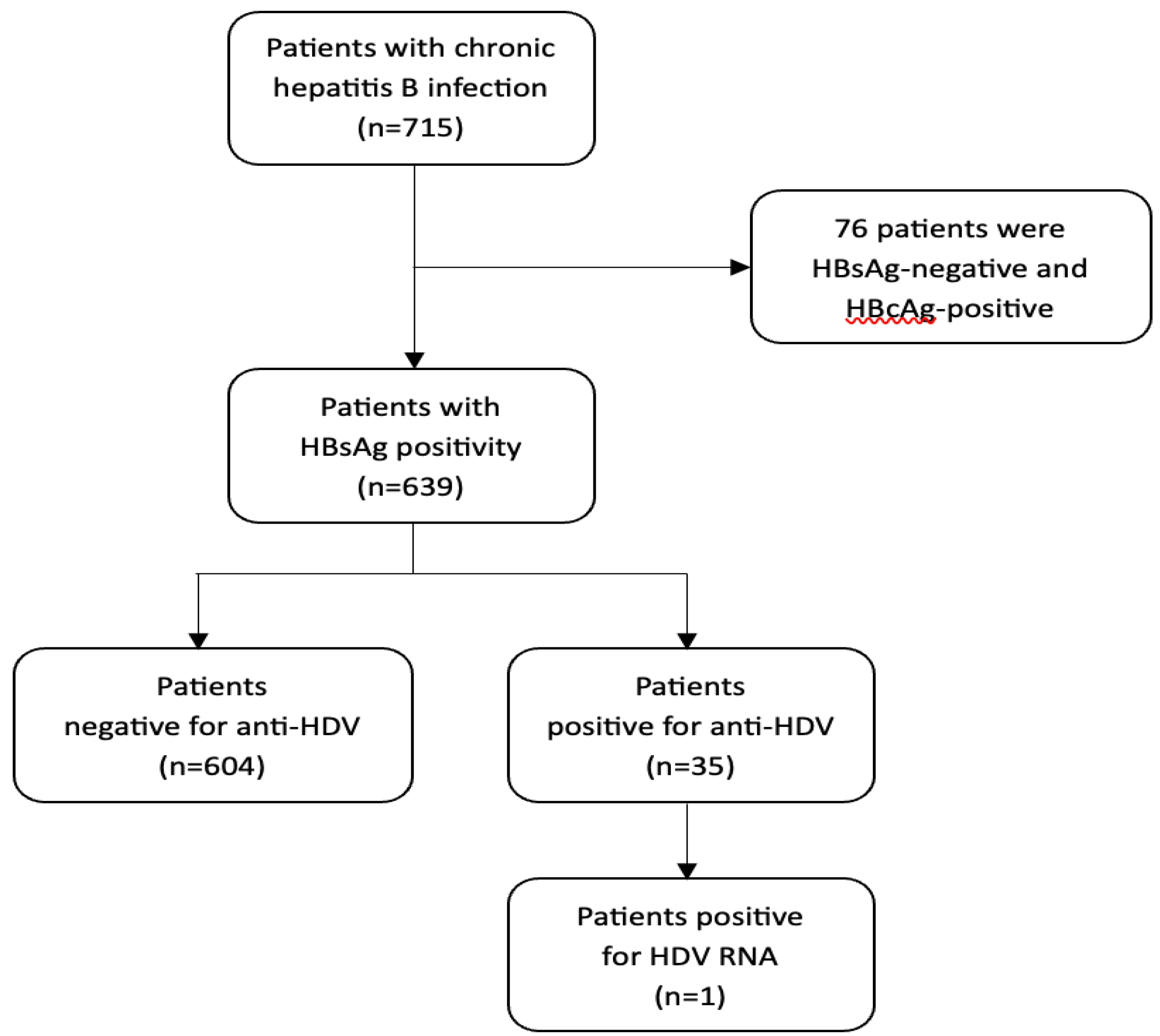

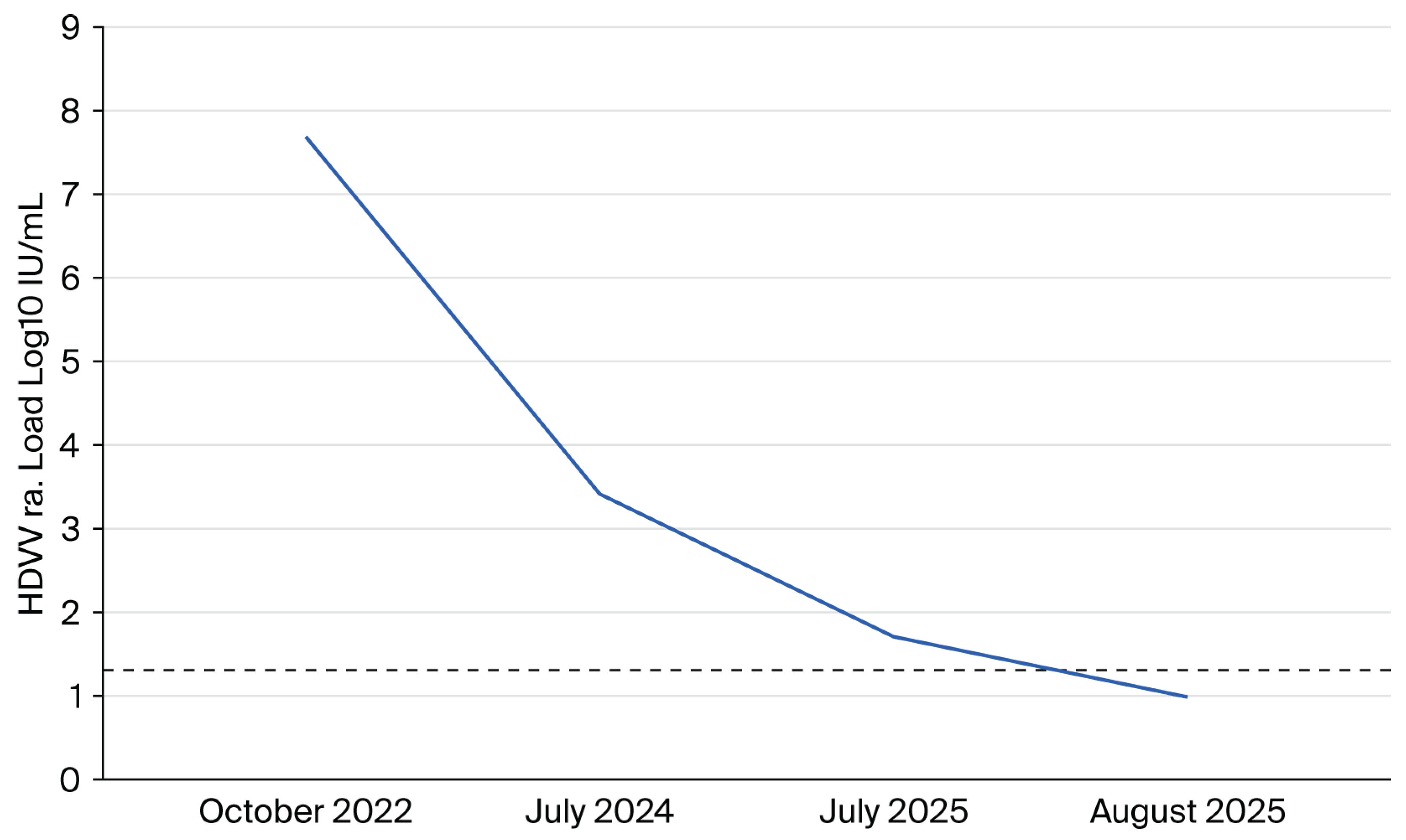

3.2. HDV Seroprevalence and Virological Findings

3.3. Fibrosis Assessment

3.4. Factors Associated with Anti-HDV Positivity

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mentha, N.; Clément, S.; Negro, F.; Alfaiate, D. A review on hepatitis D: From virology to new therapies. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 17, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, S.; Neumann-Haefelin, C.; Lampertico, P. Hepatitis D virus in 2021: Virology, immunology and new treatment approaches for a difficult-to-treat disease. Gut 2021, 70, 1782–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negro, F.; Lok, A.S. Hepatitis D: A Review. JAMA 2023, 330, 2376–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheller, L.; Hilgard, G.; Anastasiou, O.; Dittmer, U.; Kahraman, A.; Wedemeyer, H.; Deterding, K. Poor clinical and virological outcome of nucleos (t) ide analogue monotherapy in HBV/HDV co-infected patients. Medicine 2021, 100, e26571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, A.J.; Kreuels, B.; Henrion, M.Y.; Giorgi, E.; Kyomuhangi, I.; de Martel, C.; Hutin, Y.; Geretti, A.M. The global prevalence of hepatitis D virus infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Gish, R.; Jacobson, I.M.; Hu, K.-Q.; Wedemeyer, H.; Martin, P. Diagnosis and management of hepatitis delta virus infection. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 3237–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi-Shearer, D.; Child, H.; Razavi-Shearer, K.; Voeller, A.; Razavi, H.; Buti, M.; Tacke, F.; Terrault, N.; Zeuzem, S.; Abbas, Z. Adjusted estimate of the prevalence of hepatitis delta virus in 25 countries and territories. J. Hepatol. 2024, 80, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naamani, K.; Al-Maqbali, A.; Al-Sinani, S. Characteristics of hepatitis B infection in a sample of Omani patients. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2013, 13, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Awaidy, S.T.; Bawikar, S.P.; Al Busaidy, S.S.; Al Mahrouqi, S.; Al Baqlani, S.; Al Obaidani, I.; Alexander, J.; Patel, M.K. Progress toward elimination of hepatitis B virus transmission in Oman: Impact of hepatitis B vaccination. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013, 89, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naamani, K.; Al-Harthi, R.; Al-Busafi, S.A.; Al Zuhaibi, H.; Al-Sinani, S.; Omer, H.; Rasool, W. Hepatitis B related liver cirrhosis in Oman. Oman Med. J. 2022, 37, e384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornberg, M.; Sandmann, L.; Jaroszewicz, J.; Kennedy, P.; Lampertico, P.; Lemoine, M.; Lens, S.; Testoni, B.; Lai-Hung Wong, G.; Russo, F.P. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J. Hepatol. 2025, 83, 502–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, M.; Amin, I.; Idrees, M.; Ali, A.; Rafique, S.; Naz, S. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis delta and hepatitis B viruses circulating in two major provinces (East and North-West) of Pakistan. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 64, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safarpour, A.R.; Shahedi, A.; Fattahi, M.R.; Sadeghi, E.; Akbarzadeh, M.; Ahmadi, L.; Nikmanesh, N.; Fallahzadeh Abarghooee, E.; Shamsdin, S.A.; Akrami, H.; et al. Epidemiology of Hepatitis D Virus and Associated Factors in Patients Referred to Level Three Hepatitis Clinic, Fars Province, Southern Iran. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 50, 220–228. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Asmi, A.; Al-Jabri, F.S.; Al-Amrani, S.A.; Al Farsi, Y.; Al Sabahi, F.; Al-Futaisi, A.; Al-Adawi, S. Medical Tourism and Neurological Diseases: Omani Patients’ Experience Seeking Treatment Abroad. Oman Med. J. 2024, 39, e628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhahry, S.H.; Aghanashinikar, P.N.; Al-Marhuby, H.A.; Buhl, M.R.; Daar, A.S.; Al-Hasani, M.K. Hepatitis B, delta and human immunodeficiency virus infections among Omani patients with renal diseases: A seroprevalence study. Ann. Saudi Med. 1994, 14, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coller, K.E.; Butler, E.K.; Luk, K.-C.; Rodgers, M.A.; Cassidy, M.; Gersch, J.; McNamara, A.L.; Kuhns, M.C.; Dawson, G.J.; Kaptue, L. Development and performance of prototype serologic and molecular tests for hepatitis delta infection. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbandi, A.; Mashati, P.; Yami, A.; Gharehbaghian, A.; Namini, M.T.; Gharehbaghian, A. Status of blood transfusion in World Health Organization-Eastern Mediterranean Region (WHO-EMR): Successes and challenges. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2017, 56, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Al-Rifai, A.; Sanai, F.M.; Alghamdi, A.S.; Sharara, A.I.; Saad, M.F.; van Selm, L.; Alqahtani, S.A. Hepatitis delta virus infection prevalence, diagnosis and treatment in the Middle East: A scoping review. Liver Int. 2023, 43, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Ou, X.; Li, S.; Ma, Z.; Wang, W.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; Liu, J.; Pan, Q. Estimating the global prevalence, disease progression, and clinical outcome of hepatitis delta virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 221, 1677–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.-Y.; Shen, D.-T.; Ji, D.-Z.; Han, P.-C.; Zhang, W.-M.; Ma, J.-F.; Chen, W.-S.; Goyal, H.; Pan, S.; Xu, H.-G. Prevalence and burden of hepatitis D virus infection in the global population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2019, 68, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salpini, R.; Piermatteo, L.; Caviglia, G.P.; Bertoli, A.; Brunetto, M.R.; Bruzzone, B.; Callegaro, A.; Caudai, C.; Cavallone, D.; Chessa, L.; et al. Comparison of diagnostic performances of HDV-RNA quantification assays used in clinical practice: Results from a national quality control multicenter study. J. Clin. Virol. 2025, 180, 105850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wranke, A.; Pinheiro Borzacov, L.M.; Parana, R.; Lobato, C.; Hamid, S.; Ceausu, E.; Dalekos, G.N.; Rizzetto, M.; Turcanu, A.; Niro, G.A. Clinical and virological heterogeneity of hepatitis delta in different regions world-wide: The Hepatitis Delta International Network (HDIN). Liver Int. 2018, 38, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Gal, F.; Brichler, S.; Drugan, T.; Alloui, C.; Roulot, D.; Pawlotsky, J.M.; Dény, P.; Gordien, E. Genetic diversity and worldwide distribution of the deltavirus genus: A study of 2152 clinical strains. Hepatology 2017, 66, 1826–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.W.; Huang, Y.H.; Huo, T.I.; Shih, H.H.; Sheen, I.J.; Chen, S.W.; Lee, P.C.; Lee, S.D.; Wu, J.C. Genotypes and viremia of hepatitis B and D viruses are associated with outcomes of chronic hepatitis D patients. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 1625–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liver, E.A.f.t.S.o.t. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on hepatitis delta virus. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 433–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarin, S.; Kumar, M.; Lau, G.; Abbas, Z.; Chan, H.; Chen, C.; Chen, D.; Chen, H.; Chen, P.; Chien, R. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: A 2015 update. Hepatol. Int. 2016, 10, 1–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrault, N.A.; Lok, A.S.; McMahon, B.J.; Chang, K.M.; Hwang, J.P.; Jonas, M.M.; Brown, R.S., Jr.; Bzowej, N.H.; Wong, J.B. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology 2018, 67, 1560–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Riyami, A.Z.; Daar, S. Transfusion in Haemoglobinopathies: Review and recommendations for local blood banks and transfusion services in Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2018, 18, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Busafi, S.A.; Al-Harthi, R.; Al-Naamani, K.; Al-Zuhaibi, H.; Priest, P. Risk factors for hepatitis B virus transmission in Oman. Oman Med. J. 2021, 36, e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheorghe, L.; Csiki, I.E.; Iacob, S.; Gheorghe, C.; Trifan, A.; Grigorescu, M.; Motoc, A.; Suceveanu, A.; Curescu, M.; Caruntu, F.; et al. Hepatitis Delta Virus Infection in Romania: Prevalence and Risk Factors. J. Gastrointestin. Liver. Dis. 2015, 24, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordieres, C.; Navascués, C.A.; González-Diéguez, M.L.; Rodríguez, M.; Cadahía, V.; Varela, M.; Rodrigo, L.; Rodríguez, M. Prevalence and epidemiology of hepatitis D among patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: A report from Northern Spain. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 29, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béguelin, C.; Atkinson, A.; Boyd, A.; Falconer, K.; Kirkby, N.; Suter-Riniker, F.; Günthard, H.F.; Rockstroh, J.K.; Mocroft, A.; Rauch, A. Hepatitis delta infection among persons living with HIV in Europe. Liver Int. 2023, 43, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, D.W.; Soriano, V.; Barreiro, P.; Sherman, K.E. Triple Threat: HDV, HBV, HIV Coinfection. Clin. Liver Dis. 2023, 27, 955–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palom, A.; Rando-Segura, A.; Vico, J.; Pacín, B.; Vargas, E.; Barreira-Díaz, A.; Rodríguez-Frías, F.; Riveiro-Barciela, M.; Esteban, R.; Buti, M. Implementation of anti-HDV reflex testing among HBsAg-positive individuals increases testing for hepatitis D. JHEP Rep. 2022, 4, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzouki, A.N.; Bashir, S.M.; Elahmer, O.; Elzouki, I.; Alkhattali, F. Prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis D virus infection in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection attending the three main tertiary hospitals in Libya. Arab. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 18, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzl, E.; Ciesek, S.; Cornberg, M.; Maasoumy, B.; Heim, A.; Chudy, M.; Olivero, A.; Miklau, F.N.; Nickel, A.; Reinhardt, A. Reliable quantification of plasma HDV RNA is of paramount importance for treatment monitoring: A European multicenter study. J. Clin. Virol. 2021, 142, 104932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wranke, A.; Hardtke, S.; Heidrich, B.; Dalekos, G.; Yalçin, K.; Tabak, F.; Gürel, S.; Çakaloğlu, Y.; Akarca, U.S.; Lammert, F. Ten-year follow-up of a randomized controlled clinical trial in chronic hepatitis delta. J. Viral Hepat. 2020, 27, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroffolini, T.; Morisco, F.; Ferrigno, L.; Pontillo, G.; Iantosca, G.; Cossiga, V.; Crateri, S.; Tosti, M.E.; SEIEVA collaborating group. Acute Delta Hepatitis in Italy spanning three decades (1991–2019): Evidence for the effectiveness of the hepatitis B vaccination campaign. J. Viral Hepat. 2022, 29, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.H.; Lee, S.S.J.; Yu, M.L.; Chang, T.T.; Su, C.W.; Hu, B.S.; Chen, Y.S.; Huang, C.K.; Lai, C.H.; Lin, J.N. Changing hepatitis D virus epidemiology in a hepatitis B virus endemic area with a national vaccination program. Hepatology 2015, 61, 1870–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, V.A.; Udah, D.C.; Adnani, Q.E.S. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Clinical Profiles of Hepatitis D Virus in Nigeria: A Systematic Review, 2009–2024. Viruses 2024, 16, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-C.; Chen, T.-K.; Han, H.-F.; Lin, Y.-C.; Hwang, Y.-M.; Kao, J.-H.; Chen, P.-J.; Liu, C.-J. Investigating the prevalence and clinical effects of hepatitis delta viral infection in Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2021, 54, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombotz, H.; Schreier, G.; Neubauer, S.; Kastner, P.; Hofmann, A. Gender disparities in red blood cell transfusion in elective surgery: A post hoc multicentre cohort study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertakis, K.D.; Azari, R.; Helms, L.J.; Callahan, E.J.; Robbins, J.A. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J. Fam. Pract. 2000, 49, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roulot, D.; Brichler, S.; Layese, R.; BenAbdesselam, Z.; Zoulim, F.; Thibault, V.; Scholtes, C.; Roche, B.; Castelnau, C.; Poynard, T. Origin, HDV genotype and persistent viremia determine outcome and treatment response in patients with chronic hepatitis delta. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1046–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palom, A.; Rodríguez-Tajes, S.; Navascués, C.A.; García-Samaniego, J.; Riveiro-Barciela, M.; Lens, S.; Rodríguez, M.; Esteban, R.; Buti, M. Long-term clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis delta: The role of persistent viraemia. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 51, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, H.; Westman, G.; Falconer, K.; Duberg, A.S.; Weiland, O.; Haverinen, S.; Wejstål, R.; Carlsson, T.; Kampmann, C.; Larsson, S.B. Long-term study of hepatitis delta virus infection at secondary care centers: The impact of viremia on liver-related outcomes. Hepatology 2020, 72, 1177–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bockmann, J.-H.; Grube, M.; Hamed, V.; von Felden, J.; Landahl, J.; Wehmeyer, M.; Giersch, K.; Hall, M.T.; Murray, J.M.; Dandri, M. High rates of cirrhosis and severe clinical events in patients with HBV/HDV co-infection: Longitudinal analysis of a German cohort. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Total Cohort n = 639 (%) |

Negative for HDV n = 603 (%) |

Positive for HDV n = 36 (%) |

p-Value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Age (mean ± SD) | 46.61 ± 8.76 Range of 28–85 |

46.77 ± 8.80 | 44.00 ± 7.73 | 0.07 |

| Male gender | 379 (59.31) | 372 (61.69) | 7(19.44) | <0.001 | |

| Married | 623 (97.50) | 587 (97.35) | 36 (100.00) | 0.32 | |

| Clinical | DM | 47 (7.36) | 45 (7.46) | 2 (5.56) | 0.67 |

| Hypertension | 35 (5.48) | 33 (5.47) | 2 (5.56) | 0.98 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 18 (2.82) | 18 (2.99) | 0 (0.00) | 0.29 | |

| CKD | 3 (0.47) | 3 (0.50) | 0 (0.00) | 0.67 | |

| Liver transplantation | 7 (1.10) | 6 (1.00) | 1 (2.78) | 0.32 | |

| MASLD | 266 (41.69) | 253 (41.96) | 13 (37.14) | 0.57 | |

| HCC | 3 (0.47) | 3 (0.50) | 0 (0.00) | 0.67 | |

| HBV treatment | 109 (17.06) | 106 (17.58) | 3 (8.33) | 0.15 | |

| Risk factors | Travel to endemic area | 373 (58.37) | 355 (58.87) | 18 (50.00) | 0.29 |

| Family history of HBV | 93 (14.55) | 86 (14.26) | 7 (19.44) | 0.39 | |

| Blood transfusion | 6 (0.94) | 3 (0.50) | 3 (8.33) | <0.001 | |

| History of surgery | 64 (10.02) | 57 (9.45) | 7 (19.44) | 0.05 | |

| Alcohol intake | 7 (1.10) | 7 (1.16) | 0 (0.00) | 0.52 | |

| Smoking | 4 (0.63) | 4 (0.66) | 0 (0.00) | 0.62 | |

| Co-infection | HCV | 5 (0.78) | 5 (0.83) | 0 (0.00) | 0.58 |

| HIV | 1 (0.16) | 1 (0.17) | 0 (0.00) | 0.81 | |

| Labs (mean ± SD) |

Total bilirubin | 9.12 ± 8.77 | 9.19 ± 8.93 | 7.91 ± 5.41 | 0.39 |

| Serum albumin | 43 ± 5 | 43 ± 5 | 42 ± 4 | 0.16 | |

| ALT | 30 ±28 | 30 ± 29 | 24 ± 16 | 0.15 | |

| AST | 26 ± 17 | 26 ± 17 | 24± 19 | 0.69 | |

| ALP | 73 ± 28 | 74 ± 28 | 68 ± 25 | 0.28 | |

| HBe Ag | 32 (5.01) | 31 (5.14) | 1 (2.78) | 0.53 | |

| HBVDNA (log) | 3.18 ± 1.42 | 3.19 ± 1.43 | 3.03 ± 1.42 | 0.55 | |

| Fibrosis * | F0–F1 | 596 (93.27) | 560 (92.87) | 36 (100) | 0.43 |

| F2 | 27 (4.23) | 27 (4.48) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| F3 | 3 (0.47) | 3 (0.50) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| F4 | 13 (2.03) | 13 (2.16) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Variables | Univariate Logistic Regression | Multivariate Logistic Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Age | 0.96 (0.92–1.00) | 0.07 | 0.94 (0.90–0.99) | 0.05 |

| Male gender | 0.15 (0.06–0.35) | <0.001 | 0.10 (0.04–0.28) | <0.001 |

| History of surgery | 2.31 (0.97–5.52) | 0.05 | 1.47 (0.53–4.08) | 0.46 |

| Blood transfusion | 18.18 (3.53–93.56) | <0.001 | 36.72 (4.03–334.24) | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).